- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What Motivates Lifelong Learners

- John Hagel III

Many leaders think it’s the fear of losing your job. They’re wrong.

Looking to stay ahead of the competition, companies today are creating lifelong learning programs for their employees, but they are often less effective than they could be. That’s because they don’t inspire the right kind of learning: The creation of new knowledge (and not just the transfer of existing knowledge about existing skills). The author’s research shows that those who are motivated to this kind of learning are spurred not by fear of losing their jobs, which is often the motivation given, but by what he calls the “passion of the explorer.” The article describes this mindset and how companies can create it among their employees.

It seems that everyone in business today is talking about the need for all workers to engage in lifelong learning as a response to the rapid pace of technological and strategic change all around us. But I’ve found that most executives and talent management professionals who are charged with getting their people to learn aren’t thinking about what drives real learning — the creation of new knowledge, not just the handoff of existing knowledge. As a result, many companies are missing opportunities to motivate their employees to engage in the kind of learning that will actually help them innovate and keep pace with their customers’ changing needs.

- John Hagel III recently retired from Deloitte, where he founded and led the Center for the Edge , a research center based in Silicon Valley. A long-time resident of Silicon Valley, he is also a compulsive writer, having published eight books, including his most recent one, The Journey Beyond Fear . He will be establishing a new Center to offer programs based on the book.

Partner Center

Lifelong Learning

Ivan Andreev

Demand Generation & Capture Strategist

ivan.andreev@valamis.com

February 17, 2022 · updated March 7, 2024

8 minute read

What is lifelong learning?

Importance of lifelong learning, examples of lifelong learning, benefits of lifelong learning, organizational lifelong learning, how to adopt lifelong learning in your life.

Lifelong learning does not necessarily have to restrict itself to informal learning, however. It is best described as being voluntary with the purpose of achieving personal fulfillment. The means to achieve this could result in informal or formal education.

Whether pursuing personal interests and passions or chasing professional ambitions, lifelong learning can help us to achieve personal fulfillment and satisfaction.

It recognizes that humans have a natural drive to explore, learn and grow and encourages us to improve our own quality of life and sense of self-worth by paying attention to the ideas and goals that inspire us.

We’re all lifelong learners

But what does personal fulfillment mean?

The reality is that most of us have goals or interests outside of our formal schooling and jobs. This is part of what it means to be human: we have a natural curiosity and we are natural learners. We develop and grow thanks to our ability to learn.

Lifelong learning recognizes that not all of our learning comes from a classroom.

- For example, in childhood, we learn to talk or ride a bike.

- As an adult, we learn how to use a smartphone or learn how to cook a new dish.

These are examples of the everyday lifelong learning we engage in on a daily basis, either through socialization, trial and error, or self-initiated study.

Personal fulfillment and development refer to natural interests, curiosity, and motivations that lead us to learn new things. We learn for ourselves, not for someone else.

Key checklist for lifelong learning:

- Self-motivated or self-initiated

- Doesn’t always require a cost

- Often informal

- Self-taught or instruction that is sought

- Motivation is out of personal interest or personal development

The definitive guide to microlearning

The what, why, and how-to guide to inject microlearning into your company.

Here are some of the types of lifelong learning initiatives that you can engage in:

- Developing a new skill (eg. sewing, cooking, programming, public speaking, etc)

- Self-taught study (eg. learning a new language, researching a topic of interest, subscribing to a podcast, etc)

- Learning a new sport or activity (eg. Joining martial arts, learning to ski, learning to exercise, etc)

- Learning to use a new technology (smart devices, new software applications, etc)

- Acquiring new knowledge (taking a self-interest course via online education or classroom-based course)

Incorporating lifelong learning in your life can offer many long-term benefits, including:

1. Renewed self-motivation

Sometimes we get stuck in a rut doing things simply because we have to do them, like going to work or cleaning the house.

Figuring out what inspires you puts you back in the driver’s seat and is a reminder that you can really do things in life that you want to do.

2. Recognition of personal interests and goals

Re-igniting what makes you tick as a person reduces boredom, makes life more interesting, and can even open future opportunities.

You never know where your interests will lead you if you focus on them.

3. Improvement in other personal and professional skills

While we’re busy learning a new skill or acquiring new knowledge, we’re also building other valuable skills that can help us in our personal and professional lives.

This is because we utilize other skills in order to learn something new. For example, learning to sew requires problem-solving. Learning to draw involves developing creativity.

Skill development can include interpersonal skills, creativity, problem-solving, critical thinking, leadership, reflection, adaptability and much more.

4. Improved self-confidence

Becoming more knowledgeable or skilled in something can increase our self-confidence in both our personal and professional lives.

- In our personal lives, this confidence can stem from the satisfaction of devoting time and effort to learning and improving, giving us a sense of accomplishment.

- In our professional lives, this self-confidence can be the feeling of trust we have in our knowledge and the ability to apply what we’ve learned.

Sometimes lifelong learning is used to describe a type of behavior that employers are seeking within the organization. Employers are recognizing that formal education credentials are not the only way to recognize and develop talent and that lifelong learning may be the desired trait.

Thanks to the fast pace of today’s knowledge economy, organizations are seeing lifelong learning as a core component in employee development . The idea is that employees should engage in constant personal learning in order to be adaptable and flexible for the organization to stay competitive and relevant.

This type of personal learning is often referred to as continuous learning. You can read more about continuous learning and what it means for both the employee and employer here.

According to some researchers, however, there is criticism that organizations are leveraging the concept of lifelong learning in order to place the responsibility of learning on employees instead of offering the resources, support and training needed to foster this kind of workforce.

Do I need to be proactive about lifelong learning?

Most people will learn something new at some point in their daily routine just by talking with other people, browsing the internet based on personal interest, reading the newspaper, or engaging in personal interest.

However, if making more effort to learn something new is important for either personal, family, or career reasons, or there is a need for a more organized structure, then here are some steps to get started.

1. Recognize your own personal interests and goals

Lifelong learning is about you, not other people and what they want.

Reflect on what you’re passionate about and what you envision for your own future.

If progressing your career is your personal interest, then there are ways to participate in self-directed learning to accomplish this goal.

If learning history is your passion, there are likewise ways to explore this interest further.

2. Make a list of what you would like to learn or be able to do

Once you’ve identified what motivates you, explore what it is about that particular interest or goal that you want to achieve.

Returning to our example of someone having a passion for history, perhaps it is desired to simply expand knowledge on the history of Europe. Or perhaps the interest is so strong that going for a Ph.D. is a dream goal.

Both of these are different levels of interest that entail different ways of learning.

3. Identify how you would like to get involved and the resources available

Achieving our personal goals begins with figuring out how to get started.

Researching and reading about the interest and goal can help to formulate how to go about learning it.

With our history example: the person who wants to simply learn more about a particular historical time period could discover books in the library catalog, blogs, magazines and podcasts dedicated to the subject, or even museums and talks.

The individual who wanted to achieve A Ph.D. in history as a personal goal could research university programs that could be done part-time or online, as well as the steps one would need to take to reach the doctorate level.

4. Structure the learning goal into your life

Fitting a new learning goal into your busy life takes consideration and effort.

If you don’t make time and space for it, it won’t happen.

It can easily lead to discouragement or quitting the learning initiative altogether.

Plan out how the requirements of the new learning initiative can fit into your life or what you need to do to make it fit.

For example, if learning a new language is the learning goal, can you make time for one hour a day? Or does 15 minutes a day sound more realistic?

Understanding the time and space you can devote to the learning goal can help you to stick with the goal in the long-run.

5. Make a commitment

Committing to your decision to engage in a new learning initiative is the final and most important step.

If you’ve set realistic expectations and have the self-motivation to see it through, commit to it and avoid making excuses.

You might be interested in

Enterprise Learning Platform

Discover what an enterprise learning platform is and why you need a new learning solution. Discover the main features every enterprise LMS should have.

Learning Record Store (LRS)

Learn what Learning Record (LRS) is and what it enables. Discover 4 key steps on how to implement it and how to choose the right vendor.

Skills-based talent management

Discover what a skills-based approach in talent hiring and management is. Learn the key 5 steps on how to implement it in your organization.

- Crimson Careers

- For Employers

- Harvard College

- Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts & Sciences

- Harvard Extension School

- Premed / Pre-Health

- Families & Supporters

- Faculty & Staff

- Prospective Students

- First Generation / Low Income

- International Students

- Students of Color

- Students with Disabilities

- Undocumented Students

- Explore Interests & Make Career Decisions

- Create a Resume/CV or Cover Letter

- Expand Your Network

- Engage with Employers

- Search for a Job

- Find an Internship

- January Experiences (College)

- Find & Apply for Summer Opportunities Funding

- Prepare for an Interview

- Negotiate an Offer

- Apply to Graduate or Professional School

- Access Resources

- AI for Professional Development and Exploration

- Arts & Entertainment

- Business & Entrepreneurship

- Climate, Sustainability, Environment, Energy

- Government, Int’l Relations, Education, Law, Nonprofits

- Life Sciences & Health

- Technology & Engineering

- Still Exploring

- Talk to an Advisor

What Is Lifelong Learning? (And How to Do it Yourself)

- Share This: Share What Is Lifelong Learning? (And How to Do it Yourself) on Facebook Share What Is Lifelong Learning? (And How to Do it Yourself) on LinkedIn Share What Is Lifelong Learning? (And How to Do it Yourself) on X

What Is Lifelong Learning? (And How to Do it Yourself) was originally published on Forage .

We often equate school with learning — so once we’ve graduated, we’re done, right? While we may not return to lectures and discussion groups, learning is far from over the second we leave high school or college. Embracing lifelong learning, or the concept of ongoing learning, can help you grab the attention of employers, get hired, and succeed in your entire career.

So, what exactly is lifelong learning, and why do employers care so much about it? Here’s what you need to know, how to get started, and how to show it off in an application.

Lifelong Learning Definition

Lifelong learning is the constant, ongoing pursuit of knowledge. This practice “ensures that individuals continually enhance their skills and knowledge, regardless of occupation, age, or educational level, enabling them to stay ahead of the game,” says Emily Maguire, managing director and career consultant at Reflections Career Coaching.

Typically, lifelong learning is self-motivated, meaning the desire to learn comes from a desire for personal and professional growth.

Professional Skills Development

Develop critical professional skills like project planning, setting goals, and relationship management in a real-world work environment.

Avg. Time: 3-4 hours

Skills you’ll build: Time management, scheduling, explaining analysis, presentations

Lifelong Learning Examples

So, what does lifelong learning look like? While you can take courses or pursue formalized education as part of lifelong learning, this kind of learning doesn’t have a specific structure. Examples of lifelong learning include:

- Taking online courses

- Learning a new language

- Joining a book club

- Listening to podcasts

- Watching TED Talks or educational YouTube videos

- Attending a workshop or seminar

- Earning a professional certification

- Completing a coding bootcamp

- Learning a musical instrument

- Taking an art or cooking class

- Doing a DIY home improvement project

- Picking up a new hobby, like knitting or photography

- Conducting independent research

- Trying a new fitness class or physical activity

Lifelong learning doesn’t always have to be an intense academic research project or something applicable to the professional skills you want to develop. The main point of lifelong learning is that you’re building a new skill or knowledge even if that doesn’t obviously translate to your dream job — flexing that learning muscle is a valuable skill you can transfer to any career path.

Why Do Employers Care About Lifelong Learning?

Employers care about lifelong learning because they seek employees who are willing to upskill, adapt, and navigate change.

It Shows the Ability to Upskill

“Doors will open for you if you keep a learner’s mindset as you leave school and are constantly willing to get out of your comfort zone,” says Arissan Nicole, career and resume coach and workplace expert. “Employers want people that are open and committed to growth. Innovation and creativity take trying new things, taking risks, and being open to failing. Those committed to lifelong learning know that failing is a step in the learning process and have the resilience to keep moving forward. Employers want people who are unwilling to give up and motivated to do whatever it takes to solve a problem or find a solution.”

As an early career professional, lifelong learning is essential because you don’t have many job skills yet — you’ll learn them on the job! Employers know and expect this, so they’re primarily looking to hire entry-level candidates who’ve shown they’re committed to learning new skills quickly.

“From our recruitment data, most fresh employees have a greater success rate when they stress on lifelong learning in their CVs and interviews,” says Philip McParlane, founder of 4dayweek.io, the world’s largest four day workweek recruitment platform. “This is because lifelong learners embody a growth mindset that proves instrumental in navigating the swift transformations within industries. Companies recognize this quality as a strategic asset, understanding that employees committed to continuous learning contribute to innovation and demonstrate resilience in the face of change.”

Helps Employees Adapt to a Changing Work Landscape

Lifelong learning is also vital to employers throughout your career as the working world changes. For example, an employer might expect you to use a new technology or software to do your job. Or, there may be a shift in your organization’s structure, and your boss may expect you to take on different projects or leadership responsibilities. Employees who can embrace change by learning new skills are highly valuable to employers.

“Regardless of one’s chosen profession, the inclination and ability to learn and adapt are central to success on the job, any job,” says Bill Catlette, partner at Contented Cow, a leadership development company. “There are very few roles in the modern workspace where the knowledge required to excel is static.”

How to Practice Lifelong Learning

If lifelong learning is the key to getting hired and success at work, how can you start?

Take a Forage Job Simulation

Forage job simulations are free, self-paced programs that show you what it’s like to work in a specific role at a top employer. In these simulations, you’ll build real-world work skills by replicating tasks that someone on a team at the company would actually do — whether that’s coding a new feature for an app, planning a marketing campaign , or writing a hypothetical email to a client explaining legal considerations in their current case.

Once you complete a Forage job simulation, you’ll get a certificate you can put on your LinkedIn profile and examples of how to share what skills you learned on your resume and in an interview. Employers are also more likely to hire students who’ve completed Forage job simulations — a sign of lifelong learning!

Unsure where to get started? Take our quiz to find the best job simulation for you .

Pursue Independent Projects

Pursuing a project on a topic you’re interested in can show employers that you’re self-motivated and willing to learn. There are tons of options depending on your career interest:

- An aspiring writer working on articles and publishing them on a personal blog

- An aspiring software engineer contributing to an open-source project

- An aspiring data analyst analyzing a public dataset

- An aspiring UX designer redesigning the experience of a famous brand’s website

- An aspiring social media manager developing a strategy for a personal brand or business’s social media

Digital Design & UX

Conduct user research and create wireframes for an app for the electric industry.

Avg. Time: 5-6 hours

Skills you’ll build: Mobile design, app design, persona creation, UX, UI

Work With Others

While lifelong learning often comes from personal motivation, collaborating with others can help you build soft skills and help keep you disciplined.

For example, you could join a book club with fellow aspiring marketing professionals and all read books about marketing strategy. Or, if you’re an aspiring web developer, you and some friends could decide to participate in a daily coding challenge. Finding people who also want to learn can help inspire you and even help you discover new ways to achieve your goals.

Set SMART Goals

Figuring out when and how to fit lifelong learning into your life can be complicated and overwhelming, especially when first trying to enter the workforce! Setting SMART goals can help you break down the process into smaller, achievable, and actionable steps.

SMART goals are:

- Specific: What exactly do you want to learn?

- Measurable: How are you measuring success? What defines a “finished” result?

- Actionable: When do you have time to accomplish this? What extra resources do you need?

- Relevant: How will this help you in your prospective career?

- Time-bound: What is your deadline?

How to Show Lifelong Learning in a Job Application

You’re doing the work of developing your knowledge and skills — now, how do you show employers that?

List It On Your Resume

It’s almost as simple as it sounds: put your lifelong learning activities on your resume !

“You can list relevant courses you have taken, certifications you have earned, workshops and trainings you may have attended, and more,” says Mary Krull, SHRM-SCP, PRC, and lead talent attraction partner at Southern New Hampshire University. “The key here will be ensuring that what you list is relevant to the role. No need to list everything you have done — keep it relevant!”

Resume Masterclass

Build a resume hiring managers look for from start to finish.

Skills you’ll build: Professional summary, illustrating your impact in teams, showcasing outcomes of your contributions

“Get strategic about relevant coursework in your education section,” says Tramelle D. Jones, strategic success and workplace wellness coach with TDJ Consulting. “For example, when applying to a position that lists tasks where you’ll utilize data analytics , list classes such as ‘Advanced Data Analytics Techniques.’ Remember to include any cross-disciplinary coursework and offer an explanation that solidifies the connection. For example, ‘Innovations in Sustainable Business Practice’ – Discussed how data analytics can be applied to consumer behavior to understand preferences.”

You can also list any trainings, workshops, certifications, or conferences in a dedicated “professional development” or “education and certification” section.

Create an Online Portfolio

If you’ve worked on independent projects, compiling your work into an online portfolio is a great way to tangibly show your skills to hiring managers . Projects make the skills and experience you articulate in your resume, cover letter, and interview visible. Online portfolios don’t need to be extravagant; a free, simple website that shows your projects is all you need.

Share Specific Examples

When preparing your application, whether writing a cover letter or practicing common job interview questions and answers , have a few lifelong learning examples you’re comfortable elaborating on. The key is to ensure they’re relevant to the role you’re applying for and demonstrate your willingness and ability to learn.

“In your cover letter, you can bring up your commitment to continuous learning and how it ties to the specific qualifications for the job,” Krull says. “Explain how your commitment to professional development will benefit the organization and align with its values. If they invite you to interview for a role, you may have an opportunity to discuss your professional development experience. Have a couple of learning experiences in mind that had a positive impact on your development. As long as those examples help you answer an interview question, this can be a great way to weave in your experience as a lifelong learner.”

Unspoken Interview Fundamentals

Learn how to develop your professional story and practice sharing it in an interview context.

Avg. Time: 2-3 hours

Skills you’ll build: Verbal communication, video interviewing, identifying strengths

Don’t be afraid to get specific, either. Naming particular processes, tools, and technologies you used to learn something new can help illustrate your lifelong learning to the hiring manager.

Lifelong Learning: The Bottom Line

Practicing lifelong learning is about continuously gaining new skills and knowledge. While this is often a personal journey, it can help you get hired and succeed throughout your career.

To start the lifelong learning process, try independent learning, working with others, and setting SMART goals to get the job done. Once you’ve gained new skills, call them out on your resume, cover letter, and in interviews.

“In a nutshell, the educational paradigm is transitioning towards a lifelong journey,” McParlane says. “Employers grasp the value of hiring individuals who perceive learning as an ongoing, dynamic process. As a prospective employee, your ability to articulate not just what you’ve learned, but how that knowledge contributes to adaptability and problem-solving , becomes a pivotal differentiator in a fiercely competitive job market.”

Start your lifelong learning journey with a free Forage job simulation .

Image credit: Canva

The post What Is Lifelong Learning? (And How to Do it Yourself) appeared first on Forage .

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Workplace Articles & More

How to be a lifelong learner, the instructor of the world’s most popular mooc explores how to change your life through the power of learning—and why you have more potential than you think..

People around the world are hungry to learn. Instructor Barbara Oakley discovered this when her online course “ Learning How to Learn ”—filmed in her basement in front of a green screen—attracted more than 1.5 million students.

Part of the goal of her course—and her new book, Mindshift: Break Through Obstacles to Learning and Discover Your Hidden Potential —is to debunk some of the myths that get in the way of learning, like the belief that we’re bad at math or too old to change careers. These are just artificial obstacles, she argues.

“People can often do more, change more, and learn more—often far more—than they’ve ever dreamed possible. Our potential is hidden in plain sight all around us,” Oakley writes.

She should know: Throughout her early schooling, she flunked math and science classes and resisted family pressure to pursue a science degree. Today? She’s a professor of engineering at Oakland University, after many different jobs in between.

Her book aims to help readers discover their hidden potential, by offering them both the tools and the inspiration to transform themselves through learning.

The benefits of lifelong learning

Besides being fun, Oakley explains, continued learning can serve us well in the workforce. Many professionals today are engaging in a practice called “second-skilling”: gaining a second area of expertise, whether it’s related to their work (like a marketer learning programming) or completely different (a fundraiser training to be a yoga instructor).

When we lose our job, or work just starts to feel unsatisfying, having other skills can give us more choice and flexibility. We can quit our job and find a new one, of course, but we can also choose to move horizontally within the same organization, taking on different responsibilities.

Mindshift tells the story of one Dutch university employee who enriched her career thanks to her passion for online video gaming. Though she didn’t necessarily think of that as a “second skill,” it ended up benefitting her (and her employer) greatly: She became community manager of the university’s online courses, devising strategies to keep digital interactions civil just as she had done in the gaming world. This goes to show, Oakley writes, that we can never tell where our expertise will lead us or where it will come in handy.

Keeping our brains active and engaged in new areas also has cognitive benefits down the line. According to one study , people who knit, sew, quilt, do plumbing or carpentry, play games, use computers, or read have greater cognitive abilities as they age. Other research found that the more education you have , or the more cognitively stimulating activity you engage in , the lower your risk of Alzheimer’s.

Learning could even extend your life. People who read books for more than 3.5 hours a week are 23 percent less likely to die over a 12-year period—a good reason to keep cracking books after college!

Learn how to learn

Whether you’re inspired to learn woodworking or web development, Mindshift offers many tips that can make your learning more efficient and enjoyable.

Focus (and don’t focus). In order to absorb information, our brains need periods of intense focus followed by periods of mind-wandering , or “diffuse attention,” Oakley explains. So, learners will actually retain more if they incorporate time for rest and relaxation to allow this processing to happen. Perhaps that’s why aficionados love the Pomodoro technique , which recommends 25-minute bursts of work followed by five-minute breaks.

We should also experiment with different levels of background noise to achieve optimal focus, Oakley advises. Quiet promotes deeper focus, while minor distractions or background noise—like what you’d find at a cafe—may encourage more diffuse attention and creative insight . (While your favorite music could help you get in the zone, music that’s loud, lyrical , or displeasing might be a distraction.)

Practice efficiently. Neuroscience research is now exploring what learning looks like in the brain—and it’s bad news for those of us who loved to cram in college. Apparently the brain can only build so many neurons each night , so regular, repeated practice is crucial.

Oakley recommends learning in “chunks”—bite-sized bits of information or skills, such as a passage in a song, one karate move, or the code for a particular technical command. Practicing these regularly allows them to become second nature, freeing up space in our conscious mind and working memory so we can continue building new knowledge. (If this doesn’t happen, you may have to select a smaller chunk.)

It also helps to practice in a variety of ways, at a variety of times. To understand information more deeply, Oakley recommends actively engaging with it by teaching ourselves aloud or creating mindmaps —web-like drawings connecting different concepts and ideas. We can also try practicing in our downtime (in line at Starbucks or in the car commuting, for example), and quickly reviewing the day’s lessons before going to sleep.

Exercise. One of the most surprising—and easiest—ways to supercharge our learning is to exercise. Physical activity can actually help us grow new brain cells and neurotransmitters ; it’s also been shown to improve our long-term memory and reverse age-related declines in brain function. In fact, walking for just 11 minutes a day is enough to reap some benefits.

While clearly informed by neuroscience, Mindshift focuses more on telling stories than explaining research—which makes it a fast read. After hearing so many tales of curiosity and transformation, you yourself may be inspired to pick up that random hobby you’ve fantasized about, or take one of many college-level courses now available online for free (like our very own Science of Happiness course ). Me? The one I signed up for starts next week.

About the Author

Kira M. Newman

Kira M. Newman is the managing editor of Greater Good . Her work has been published in outlets including the Washington Post , Mindful magazine, Social Media Monthly , and Tech.co, and she is the co-editor of The Gratitude Project . Follow her on Twitter!

You May Also Enjoy

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

1 Lifelong Learning: Introduction

Manuel London, College of Business, State University of New York at Stony Brook

- Published: 21 November 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

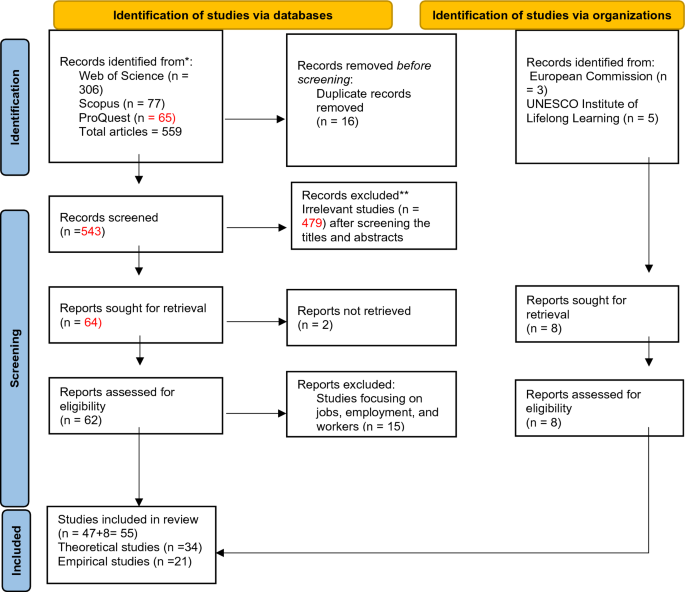

This chapter examines the scope of the field of lifelong learning, covering definitions, environmental pressures, principal theories of development and learning, and environmental resources and structures that support lifelong learning. Lifelong learning is a dynamic process that varies depending on individual skills and motivation for self-regulated, generative learning and on life events that impose challenges that sometimes demand incremental/adaptive change and other times require frame-breaking change and transformational learning. The chapter previews the major sections of this handbook, which cover theoretical perspectives, research on learning throughout life, methods to promote learning, goals for learning (i.e., what is learned), the importance of cultural and international perspectives, and emerging issues and learning challenges.

Learning is all about change, and change drives learning. The two are inevitable and go hand in glove. Change imposes gaps between what is and what is going to be, or between what was and what is now. Change creates opportunities and imposes demands. In the workforce and other areas of life, change raises questions about readiness to take advantage of opportunities or to face demands for different ways of behaving and interacting and more demanding goals to achieve. Learning can bring about change by creating new capabilities and opening the door to new and unexpected opportunities. As such, learning is risky. It upsets the status quo, raising ambiguities and uncertainties. It also has the potential to empower a person to influence the future, providing choices that would not be available otherwise.

Throughout life, changes occur that are large and small. Small changes provoke incremental changes in behavior. They force us to adapt. Indeed, we learn to adapt to these small changes almost unconsciously. We develop routines that work and apply them as coping mechanisms for managing change. Usually, behaviors that work in one setting apply equally well in another setting or a different situation, perhaps with minor adaptations. However, when we are thrust into totally new situations—transitions that are unfamiliar and uncomfortable, we learn new behaviors and skills that lead to transformational changes. If we fail to learn and fail to make the transformational change, we are likely to be mired in the past, perhaps stuck alone on a plateau while others move away and ahead of us, or worse yet, we face loss and a life of self-doubt or unhappiness.

Change and learning occur throughout our lives. They occur in work and career. Indeed, we spend our early lives in educational settings that give us life skills, but ultimately prepare us for a career. The question is whether we also learn how to learn so that we are prepared to face change, and create positive change for ourselves and others. Adaptive learners are prepared to make incremental changes. Generative learners are ready for transformational change. They seek new ideas and skills, experiment with new behaviors, and set challenging goals for themselves that bring them to new ideal states. Transformative learners have the skills to confront and create frame-breaking change. For them, change is the process of recognizing gaps, setting goals, establishing a learning plan, and maintaining motivation for carrying out the plan to achieve the goals.

This handbook is about lifelong learning. It clarifies the context and need for learning and sets an agenda for theory, research, and practice to promote successful learning and change throughout life. It examines the press for change and the concomitant need for learning at all career and life stages, through minor shifts and major transitions. It considers the extant research on learning and paves the way for exciting research that is needed to understand and promote learning to face the complexities, stresses, opportunities, and challenges of life. It examines methods to encourage and facilitate productive learning (learning that leads to goal accomplishment and meets life’s demands). It considers technological and cultural issues that shape learning in our fast-paced world. It recognizes generational differences and the value that people from different generations can contribute to each other. It also focuses our attention on emerging issues that direct future research and practice.

Lifelong or continuous learning is often viewed as the domain of adult or continuing education. This field examines how adults learn, usually within work contexts. The field encompasses continuing education and professional development programs offered by universities and corporate training centers. Today, such education is influenced by new technologies for instructional design and delivering educational programs. This handbook takes an expansive view of lifelong learning drawing from a host of fields, including psychology, sociology, gerontology, and biology. It looks at learning in young and old, in work and in life beyond the job, in Western and Eastern cultures across the globe. It offers understanding and direction to shape thinking about aging, personal growth, overcoming barriers, and innovation.

Transitions are a time for change. A key question is whether people are ready to change and learn. Opportunities for change may go unrecognized because people are stuck in their routines (Hertzog et al., 2008 ). People who are used to adapting will rely on transactions that worked in the past making incremental adjustments if necessary. People who seek new knowledge, like to try new things, and are sensitive to demands and challenges in their environment have learned how to be generative. Some have had the opportunity to be transformative in bringing about frame-breaking change.

Defining Lifelong Learning

Consider ways that lifelong learning has been conceptualized. A simple definition of lifelong learning is that it is “development after formal education: the continuing development of knowledge and skills that people experience after formal education and throughout their lives” (Encarta, 2008 ). Lifelong learning builds on prior learning as it expands knowledge and skills in depth and breadth (London, in press). Learning is “the way in which individuals or groups acquire, interpret, reorganize, change or assimilate a related cluster of information, skills, and feelings. It is also primary to the way in which people construct meaning in their personal and shared organizational lives” (Marsick, 1987 , p. 4, as quoted in Matthews, 1999 , p. 19).

The basic premise of lifelong learning is that it is not feasible to equip learners at school, college, or university with all the knowledge and skills they need to prosper throughout their lifetimes. Therefore, people will need continually to enhance their knowledge and skills, in order to address immediate problems and to participate in a process of continuous vocational and professional development. The new educational imperative is to empower people to manage their own learning in a variety of contexts throughout their lifetimes (Sharples, 2000 , p. 178; see also Bentley, 1998 ).

A traditional definition of lifelong learning is “all learning activity undertaken throughout life, with the aim of improving knowledge, skills and competences within a personal, civic, social and/or employment-related perspective” (European Commission [EC], 2001, p. 9). Jarvis ( 2006 , p. 134) offered a more detailed definition: “The combination of processes throughout a life time whereby the whole person—body (genetic, physical and biological) and mind (knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, emotions, beliefs and senses)—experiences social situations, the perceived content of which is then transformed cognitively, emotively or practically (or through any combination) and integrated into the individual person’s biography resulting in a continually changing (or more experienced) person.”

London and Smither ( 1999a ) conceptualized career-related continuous learning as a pattern of formal and informal activities that people sustain over time for the benefit of their career development. Claxton ( 2000 ), examining the challenge of lifelong learning, focuses on resilience, resourcefulness, and reflectiveness and the learner’s toolkit of learning strategies including immersion in experiences. Candy ( 1991 ) examined the concept of self-direction for lifelong learning, exploring four principle domains of self-direction: personal autonomy, willingness and ability to manage one’s overall learning endeavors, independent pursuit of learning without formal institutional support or affiliation, and learner-control of instruction. Ways of increasing learners’ self-directedness is a challenge for adult educators.

Edwards ( 1997 ) examined different notions of a learning society and the changes in adult education theory and practice that will be required to create a learning society. He addressed issues of government policy pertaining to knowledge development, economic growth, technology, and learning. The focus should be less on ways of providing adult education in a formal sense and more on understanding outputs, that is, learning and learners’ capabilities. As such, adult education should support access and participation, open and distance learning, and assessment and accreditation of outcomes in an increasing number of learning settings.

Field ( 2006 ) considered lifelong learning as a new educational order. Noting that governments are actively encouraging citizens to learn and to apply their learning across their lifespan, he explored policy measures that governments are taking to encourage adult participation in learning across the life span to achieve a viable learning society.

Creating Learning Environments

Sternberg ( 1997 ) argued that society needs a broad understanding of intelligence as “the mental abilities necessary for adaptation to, as well as shaping and selection of, any environmental context” (p. 1036). Students perform better when they learn in a way that lets them capitalize on their strengths and compensate for and remediate their weaknesses. As such, instruction and assessment should be diverse to allow for learner-guided methods for encoding and applying subject matter.

Tannenbaum ( 1998 ) described how salient aspects of an organization’s work environment can influence whether continuous learning will occur. He surveyed over 500 people in seven organizations. The results showed that every organization has a unique learning profile and relies on different sources of learning to develop individual competencies.

Zairi and Whymark ( 2000 ) showed how the transfer of learning can become embedded in an organization. They described the case of Xerox’s and Nationwide Building Society’s continuous quality improvement training and processes, started in the 1970s, which became the basis for the company’s later culture of quality improvement through its business excellence certification process.

Other Handbooks of Lifelong Learning

Several handbooks of lifelong learning examine alternative views of lifelong learning. In the introduction to his handbook, Jarvis ( 2008 ) focused on the awareness of the gap between what we know and do not know as the stimulus for learning at any stage of life. In today’s complex world, the challenge of a learning gap is increasingly frequent, making lifelong learning a habit for many people. Learning becomes necessary to ensure employability and career progression (Jarvis, 2007 ). Employers recognize the need to provide learning opportunities to keep their employees, and their companies, competitive (Department for Education and Employment, 1998 ). From a societal perspective, nonindustrialized societies have more to learn, and learning is more nuanced and complex in industrialized societies (think knowledge workers; Jarvis, 2008 ). His handbook (Jarvis, 2008 ) focuses on the learner and the societal and international context. It examines where people learn, the modes of learning, social movements, and national policies that support lifelong learning.

The International Handbook of Lifelong Learning , edited by Aspin, Chapman, Hatton, and Sawano ( 2001 ), proposed policies and an agenda for schools in the 21st century, arising from the concept of the learning community and transformations of information technology, globalization, and the move toward a knowledge economy. “We are now living in a new age in which the demands are so complex, so multifarious and so rapidly changing that the only way in which we shall be able to survive them is by committing to a process of individual, communal, and global learning throughout the lifespan of all of us.”

Focusing on transformative learning, King’s ( 2009 ) Handbook of the Evolving Research of Transformative Learning Based on the Learning Activities Survey recognizes the multiple ways that people make meaning of their lives. “Transformational learning theory serves as a comprehensive way to understand the process whereby adult learners critically examine their beliefs, assumptions, and values in light of acquiring new knowledge and correspondingly shift their worldviews to incorporate new ideas, values and expectations” (King, 2002 , p. 286). Phases of transformative learning include experiencing disorientation (e.g., recognizing a learning gap), self-examination, critical assessment of assumptions, realizing that others have experienced similar processes, exploring options, forming an action plan, and reintegration (cf. Mezirow and Associates, 2000; Cranton, 1997 ).

Wang and King’s edited book ( 2007 ) focused on workplace competencies and instructional technology advances for vocational education to support workforce competitiveness. Longworth ( 2003 ) considered policy implications of lifelong learning.

Evers, Rush, and Berdrow ( 1998 ), addressing instructional development specialists, academic leaders, and faculty members in all types of postsecondary institutions, explained what skills and competencies students need to succeed in today’s workplace. They suggested how colleges and universities can strengthen the curriculum to cultivate those skills in their undergraduate students. The book is based on research that asked executives and university presidents to identify technical skills essential for workplace mastery. These skills include managing self, communicating, managing people and tasks, and mobilizing innovation and change.

Scope of the Field

In my chapter on lifelong learning for the Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (London, in press), I examined lifelong learning from the standpoint of organizational needs and expectations, the importance of learning and development for career growth, individual differences in propensity for continuous learning, and support and reinforcement for development. I pointed out that trends driving continuous learning include pressures to maintain competitiveness and readiness to meet future needs influenced by such factors as globalization, changing technology, emphasis on sustainability, and economic cycles. I noted that support for learning includes the corporate environment and culture, the emergence of learning organizations, empowerment for self-development, and formal and informal methods of development. I discussed technological advances in career development, such as online multisource feedback surveys, just-in-time coaching, and Web-based training.

Understanding lifelong learning requires analyzing the societal, cultural, and organizational trends that drive continuous learning opportunities and behavior. Continuous learning has become a core competence for employees at all career stages (Hall & Mirvis, 1995 ). “Lifelong learning is an essential challenge for inventing the future of our societies; it is a necessity rather than a possibility or a luxury to be considered” (Fischer, 2000 , p. 265). In particular, consider the implications of lifelong learning for the growing body of professionals who are “permalancers” (Kamenetz, 2007). These individuals freelance their work as opportunities are available. They need to be aware of developments in their field of experience and may even have to change career directions in order to remain employed as they move from one temporary position to another. For most everyone, and especially knowledge workers, the complexity of our knowledge society poses information overload, the advent of high-functioning systems, and a climate of rapid technological change that demands continuous learning (Fischer, 2000 ).

Livingstone’s ( 2000 ) study of informal learning in Canada examined self-reported learning activities from a 1998 telephone survey of a national sample of 1,562 Canadian adults. The study found that more than 95% of the respondents reported being involved in some form of explicit informal learning activities that they considered significant, spending approximately 15 hours per week on informal learning on average, compared to an average of 4 hours per week in organized education courses. The most commonly cited areas of informal learning were computer skills for employment, communications skills through community volunteer activities, home renovations and cooking skills, and general interest learning about health issues.

Theories of Learning and Education

In my summary article describing the field of lifelong learning (London, in press), I noted that theories of learning and development focus on the interaction among environmental conditions, individual differences, task demands, educational technology, and career opportunities across the life span. Scholars have developed models of lifelong learning. For instance, Kozlowski and Farr ( 1988 ) developed and tested an interactionist framework to predict employee participation in updating skills. They highlight that innovation, adaptation to innovative change, and effective performance require up-to-date technical skills and knowledge obtained through participation in professional activities, continuing education, and new work assignments. Moreover, individual characteristics (e.g., technical curiosity and interest, readiness to participate in professional and continuing education activities) and contextual features (e.g., support for continued training, work characteristics that allow autonomy, and on-the-job support for learning, including feedback, the need to work with others, having a range of job functions, encountering novel problems, and uncertainty of outcomes) jointly affect individuals’ perceptions of need to learn and eventual participation in learning. People differ in their motivation to learn and in their ability to be self-directed in identifying need for learning and to control their engagement in learning (Candy, 1991 ). People develop a learning orientation as a positive feeling about learning (cf. Maurer, 2002 ) and form mastery learning goals (Bandura, 1986 ; Dweck, 1986 ). A “reflective practice” of viewing experiences as opportunities for learning and reexamining assumptions, values, methods, policies, and practices supports continuous learning habits (Marsick & Watkins, 1992 ). People learn to value and seek feedback to help them improve their performance (London & Smither, 2002 )

Life Span Development

Lifelong learning is knowledge-intensive and fluid. The clear divide between education followed by work is not as clear as it once was (Fischer, 2000 ). As such, considerable theory and research has focused on life span development. Vygotsky ( 1978 ) called the difference between an individual’s current level of ability and accomplishment and the individual’s potential level the zone of proximal development . Learning stimulates awareness of potential and of the gap between current knowledge and skills and one’s potential level. This awareness stimulates more mature, internal development processes. People become aware that they need to learn and they also become more aware of how they learn. As this occurs, they are likely to try more complex ways of learning that require deeper thinking and learning. According to Kegan’s model of life span development (see, for instance, Kegan, 1982 , 1994 ; Kegan & Lahey, 2001 ), a person moves to increasingly complex “orders of mind,” deeper levels of self-understanding and awareness of how others see the world—qualitatively different levels of social construction:

Cognitive processes of a young child.

Older children, teens, and some adults whose feelings are inseparable from those of others.

(“Traditionalism”) Teens and many adults who distinguish between their own and others’ viewpoints but feel responsible for others’ feelings. As such, they are terrific team players. More than fifty percent of all adults do not proceed beyond this third stage.

(“Modernism”) People who have a sense of self that is separate from a connection to others. They are autonomous and self-driven, self-governing and principled, but they do not quite understand the limits of self-governing systems.

(“Postmodern”) People who come to recognize the limits of their own system of principles—a stage of cognitive development that happens before midlife, if it is reached at all.

Learning experiences must be structured to recognize how people interpret events and deal with challenges that require a higher level of cognitive and emotional functioning. Some are more able than others.