- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Who Are The 'Gifted And Talented' And What Do They Need?

Anya Kamenetz

Ron Turiello's daughter, Grace, seemed unusually alert even as a newborn.

At 7 months or so, she showed an interest in categorizing objects: She'd take a drawing of an elephant in a picture book, say, and match it to a stuffed elephant and a realistic plastic elephant.

At 5 or 6 years old, when snorkeling with her family in Hawaii, she identified a passing fish correctly as a Heller's barracuda, then added, "Where are the rest? They usually travel in schools."

With a child so bright, some parents might assume that she'd do great in any school setting, and pretty much leave it at that. But Turiello was convinced she needed a special environment, in part because of his own experience. He scored very high on IQ tests as a child, but almost dropped out of high school. He says he was bored, unmotivated, socially isolated.

How The U.S. Is Neglecting Its Smartest Kids

"I took a swing at the teacher in second grade because she was making fun of my vocabulary," he recalls. "I would get bad grades because I never did my homework. I could have ended up a really well-read homeless person."

Turiello, now an attorney, and his wife, Margaret Caruso, have two children who attend a private school in Sunnyvale, Calif., exclusively for the gifted. It's called Helios, and it uses project-based learning, groups children by ability not age, and creates an individualized learning plan for each student. For Turiello, the biggest benefits to Grace, now 11, and son Marcello, 7, are social and emotional. "They don't have to pretend to be something they're not," says Turiello. "If they can be among peers and be themselves, that can really change their lives."

Estimates vary, but many say there are around 3 million students in K-12 classrooms nationwide who could be considered academically gifted and talented. The education they get is the subject of a national debate about what our public schools owe to each child in the post-No Child Left Behind era.

When it comes to gifted children, there are three big questions: How to define them, how to identify them and how best to serve them.

Skip A Grade? Start Kindergarten Early? It's Not So Easy

1. How do you define giftedness?

One of the most popular definitions, dating to the early 1990s, is "asynchronous development." That means, roughly, a student whose mental capacities develop ahead of chronological age. This concept matches the most popular tests of giftedness: IQ tests. Scores are indexed to age, with 100 as the average; a 6 year old who gives answers characteristic of a 12 year old would have an IQ of 200.

But there are problems with this framework. No 6-year-old is truly mentally identical to a 12-year-old. He or she may be brilliant at mathematics but lack background knowledge or impulse control.

In addition, IQ tests become less useful as children get older because there is less "headroom" on the test, especially for those who are already high scorers. "It's like measuring a 6-foot person with a 5-foot ruler," says Linda Silverman, an educational psychologist and founder of the Institute for the Study of Advanced Development.

Recent intelligence research de-emphasizes IQ alone and focuses on social and emotional factors.

"There's research that these other things like motivation and grit can take you to the same exact academic outcomes as someone with a higher IQ but without those things," says Scott Barry Kaufman, a psychologist who studies intelligence and creativity at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of the book Ungifted . "That's a really important finding that is just totally ignored. Our country has a narrow view of what counts as merit."

Of course, as the definitions get broader, the measurements get more subjective and thus, perhaps, less useful. Some centers for gifted children put out checklists of "giftedness" so broad that any proud parent would be hard-pressed not to recognize her child. Things like: "Has a vivid imagination." "Good sense of humor." "Highly sensitive."

1(a). How many students should be designated gifted?

It can be useful for education policy purposes to think about giftedness as it relates to the rest of the special education spectrum. Silverman argues that just as children with IQ scores two full standard deviations below the norm need special classrooms and extra resources, those who score two standard deviations above the norm need the same. By her lights, the population we should be focusing on is the top 2.5 percent to 3 percent of achievers, not the top 5 to 10 percent.

Scott Peters disagrees. He's a professor of education at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater who prepares teachers for gifted certifications. He says the question that every teacher and every school should be asking is, "How will we serve the students who already know what I'm covering today?"

In a school where most children are in remediation, he argues, a child who is simply performing on grade level may need special attention.

2. How do you identify gifted students?

The most common answer nationwide is: First, by teacher and/or parent nomination. After that come tests.

Minority and free-reduced lunch students are extremely underrepresented in gifted programs nationwide. The problem starts with that first step. Less-educated or non-English-speaking parents may not be aware of gifted program opportunities. Pre-service teachers, says Peters, typically get one day of training on gifted students, which may not prepare them to recognize giftedness in its many forms.

Research shows that screening every child , rather than relying on nominations, produces far more equitable outcomes.

Tests have their problems, too, says Kaufman. IQ and other standardized tests produce results that can be skewed by background cultural knowledge, language learner status and racial and social privilege. Even nonverbal tasks like puzzles are influenced by class and cultural background.

Using a single test-score cutoff as the criteria is common but not considered best practice.

In addition, the majority of districts in the U.S. test children for these programs before the third grade. Experts worry that identifying children only at the outset of school can be a problem, because abilities change over time, and the practice favors students who have an enriched environment at home.

Experts prefer the use of multiple criteria and multiple opportunities. Portfolios or auditions, interviews or narrative profiles may be part of the process.

3. How do you best serve gifted students?

This is the biggest controversy in gifted education. Peters says many districts focus their resources on identifying gifted or advanced learners, while offering little or nothing to serve them.

"There are cases where parents spend years advocating for students, kids get multiple rounds of testing, and at the end of the day they're provided with a little bit of differentiation or an hour of resource-room time in the course of a week," he says. "That's not sufficient for a fourth-grader, say, who needs to take geometry."

While this emphasis on diagnosis over treatment might seem paradoxical, it's compliant with the law:

In most states the law governs the identification of gifted students. But only 27 percent of districts surveyed in 2013 report a state law about how to group these students, whether in a self-contained program, or pulled out into a resource room for a single subject or offered differentiation within a classroom. And almost no states have laws mandating anything about the curriculum for gifted students.

In addition to a need to move faster and delve deeper, students whose intellectual abilities or interests don't match those of their peers often have special social and emotional needs.

"I believe that every single day in school a gifted child has the right to learn something new — not to help the teacher," Silverman says. "And to be protected from bullying, teasing and abuse."

Helping gifted students may or may not take many more resources. But it does require a shift in mindset to the idea that "every child deserves to be challenged," as Ron Turiello says.

That's why, paradoxically, many of the gifted education experts I interviewed didn't like the label "gifted." "In a perfect world, every student would have an IEP," says Kaufman.

As it happens, federal education policy is currently being reconfigured around some version of that idea.

"The whole NCLB era, and really back to the first Elementary and Secondary Education Act in the 1960s, was about getting kids to grade level, to minimal proficiency," says Peters. "There seems to be a change in belief now — that you need to show growth in every student."

That means, instead of just focusing on the 50 percent of kids who are below average, teachers should be responsible for the half who are above average, too. "That's huge. It's hard to articulate how big of a sea change that is."

Correction Oct. 2, 2015

A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Ron Turiello helped found Helios School. Turiello is a former board member at the school.

How to identify, understand and teach gifted children

Professor, Faculty of Education and Arts, Australian Catholic University

Disclosure statement

John Munro has been a chief researcher on ARC funded projects and has completed contracted projects for Australian educational authorities.

Australian Catholic University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

This is a longer read at just under 2,000 words. Enjoy!

The beginning of the 2019 school year will be a time of planning and crystal-gazing. Teachers will plan their instructional agenda in a general way. Students will think about another year at school. Parents will reflect on how their children might progress this year.

One group of students who will probably attract less attention are the gifted learners . These students have a capacity for talent, creativity and innovative ideas. They could be our future Einsteins.

They will do this only if we support them to learn in an appropriate way. And yet, there is less likely to be explicit planning and provision throughout 2019 to support these students. They’re more likely to be overlooked or even ignored.

Giftedness in the media

You may have noticed the recent interest in gifted learning and education in the media. Child Genius on SBS provided a glimpse of what the brains of some young students can do.

We can only marvel at their ability to store large amounts of information in memory, spell words correctly they’d probably not heard before and unscramble complex anagrams.

The Insight program on SBS, provided another perspective.

Students identified as gifted explained how they learned and their experiences with formal education. Most accounts pointed to a clear mismatch between how they preferred to learn and how they were taught.

Twice exceptional

The students on the Insight program showed the flipsides of the gifted education story. While some gifted students show high academic success – the academically gifted students, others show lower academic success – the “ twice exceptional ” students.

Many of the most creative people this world has known are twice exceptional . This includes scientists such as Einstein, artists such as Van Gogh, authors such as Agatha Christie and politicians such as Winston Churchill.

Read more: Intellectually gifted students often have learning disabilities

Their achievements are one reason we’re interested in gifted learning. They have the potential to contribute significantly to our world and change how we live. They’re innovators. They give us the big ideas, possibilities and options. We describe their achievements, discoveries and creations as “talent”.

These talented outcomes are not random, lucky or accidental. Instead, they come from particular ways of knowing their world and thinking about it. A talented footballer sees moves and possibilities their opponents don’t see. They think, plan, and act differently. What they do is more than what the coach has trained them to do.

Understanding gifted learning

One way of understanding gifted learning is to unpack how people respond to new information. Let me first share two anecdotes.

A year three class was learning about beetles. We turned over a rock and saw slater beetles scurrying away. I asked:

Has anyone thought of something I haven’t mentioned?

Marcus, a student in the class, asked:

How many toes does a slater have?

Why do you ask that?

Marcus replied:

They are only this long and they’re going very fast. My mini aths coach said that if I wanted to go faster I had to press back with my big toes. They must have pretty big toes to go so quick.

He continued with possibilities about how they might breathe and use energy. Marcus’ teacher reported that he often asked “quirky”, unexpected questions and had a much broader general knowledge than his peers. She had not considered the possibility he might be gifted.

Mike was solving year 12 calculus problems when he was six. He has never attended regular school but was home-schooled by his parents, who were not interested in maths. He learned about quadratic and cubic polynomials from the Khan Academy . I asked him if it was possible to draw polynomials of x to the power of 7 or 8. He did this without hesitation, noting he had never been taught to do this.

Gifted students learn in a more advanced way

People learn by converting information to knowledge. They may then elaborate, restructure or reorganise it in various ways. Giftedness is the capacity to learn in more advanced ways.

First, these students learn faster . In a given period they learn more than their regular learning peers. They form a more elaborate and differentiated knowledge of a topic. This helps them interpret more information at a time.

Second, these students are more likely to draw conclusions from evidence and reasoning rather than from explicit statements. They stimulate parts of their knowledge that were not mentioned in the information presented to them and add these inferences to their understanding.

Read more: Should gifted students go to a separate school?

This is called “ fluid analogising ” or “far transfer”. It involves combining knowledge from the two sources into an interpretation that has the characteristics of an intuitive theory about the information. This is supported by a range of affective and social factors , including high self-efficacy and intrinsic goal setting, motivation and will-power.

Their theories extend the teaching. They’re intuitive in that they’re personal and include possibilities or options the student has not yet tested. Parts of the theory may be incorrect. When given the opportunity to reflect on or field-test them, the student can validate their new knowledge, modify it or reject it.

Marcus and Mike from the earlier anecdotes engaged in these processes. So did Einstein, Churchill, Van Gogh and Christie.

Verbally gifted

A gifted learning profile manifests in multiple ways. Much of the information we’re exposed to is made up of concepts that are linked and sequenced around a topic or theme. It’s formed using agreed conventions. It may be a written narrative, a painting, a conversation or football match. Some students exposed to part of a text infer its topic and subsequent ideas – their intuitive theory about it.

These are the verbally gifted students. In the classroom they infer the direction of the teaching and give the impression of being ahead of it. This is what Mike did when he extended his knowledge beyond what the information taught him. Most of the tasks used in the Child Genius program assessed this. The children used what they knew about spelling patterns to spell unfamiliar words and to unscramble complex anagrams.

Visual-spatially gifted

Other students think about the teaching information in time and space. They use imagery and infer intuitive theories that are more lateral or creative. In the classroom their interpretations are often unexpected and may question the teaching. These are the non-verbally gifted or visual-spatially gifted students.

They frequently do not learn academic or social conventions well and are often twice exceptional. They’re more likely to challenge conventional thinking. Marcus did this when he visualised the slaters with large “beetle toes”.

What we can learn from gifted students

Educators and policy makers can learn from the student voice in the recent media programs. Some of the students on Insight told us their classrooms don’t provide the most appropriate opportunities for them to show what they know or to learn.

The twice exceptional students in the Insight program noted teachers had a limited capacity to recognise and identify the multiple ways students can be gifted. They reminded us some gifted profiles, but not the twice-exceptional profile, are prioritised in regular education.

These students thrive and excel when they have the opportunity to show their advanced interpretations initially in formats they can manage, for example, in visual and physical ways. They can then learn to use more conventional ways such as writing.

Multi-modal forms of communication are important for them. Examples include drawing pictures of their interpretations, acting out their understanding and building models to represent their understanding. The use of diagrams by the the famous physicist Richard Feynman is an example of this.

For students like Mike, adequate formal educational provision simply does not exist. With the development of information communication technology, it would be hoped that in the future adaptive and creative curricula and teaching practices could be developed for those students whose learning trajectories are far from the regular.

As a consequence, we have high levels of disengagement from regular education by some gifted students in the middle to senior secondary years. High ability Australian students under-achieve in both NAPLAN and international testing.

The problem with IQ

Identification using IQ is problematic for some gifted profiles. Some IQ tests assess a narrow band of culturally valued knowledge. They frequently do not assess general learning capacity.

As well, teachers are usually not qualified to interpret IQ assessments. The parents in the Insight program mentioned both the difficulty in having their children identified as gifted and the high costs IQ tests incurred. In Australia, these assessments can cost up to A$475 .

An obvious alternative is to equip teachers and schools to identify and assess students’ learning in the classroom for indications of gifted learning and thinking in its multiple forms. To do this, assessment tasks need to assess the quality, maturity and sophistication of the students’ thinking and learning strategies, their capacity to enhance knowledge, and also what students actually know or believe is possible about a topic or an issue.

Read more: Show us your smarts: a very brief history of intelligence testing

Classroom assessments usually don’t assess this. They are designed to test how well students have learned the teaching, not what additional knowledge the students have added to it.

Gifted students benefit from open-ended tasks that permit them to show what they know about a topic or issue. Such tasks include complex problem solving activities or challenges and open-ended assignments. We are now developing tools to assess the quality and sophistication of gifted students’ knowledge and understanding.

Tips for teachers and parents

Over the course of 2019, teachers can look for evidence of gifted learning by encouraging their students to share their intuitive theories about a topic and by completing open-ended tasks in which they extend or apply what they have learned. This can include more complex problem solving.

During reading comprehension, for example, teachers can plan tasks that require higher-level thinking, including analysis, evaluation and synthesis. Teachers need to assess and evaluate students’ learning in terms of the extent to which they elaborate on the teaching information.

Parents are often the first to notice their child learns more rapidly, remembers more, does things in more advanced ways or learns differently from their peers. Most educators have heard a parent say: “I think my child is gifted.” And sometimes the parent is correct.

Parents can use modern technology to record specific instances of high performance by their children, and share these with their child’s teachers. The mobile phone and iPad provide a good opportunity for video-recording a child’s questions during story time, their interpretations of unfamiliar contexts such as a visit to a museum, drawings or inventions the child produces and how they do this, and ways in which they solve problems in their everyday lives. These records can provide useful evidence later for educators and other professionals.

Read more: Explainer: what is differentiation and why is it poorly understood?

Parents also have a key role to play in helping their child understand what it means to learn differently from one’s peers, to value their interpretations and achievements and how they can interact socially with peers who may operate differently.

It is students’ intuitive theories about information that lead to creative, talented outcomes and innovative products. If an education system is to foster creativity and innovation, teachers need to recognise and value these theories and help these students convert them into a talent. Teachers can respond to gifted knowing and learning in its multiple forms if they know what it looks like in the classroom and have appropriate tools to identify it.

- Gifted children

- Gifted students

- gifted learning

Sydney Horizon Educators – Faculty of Engineering (Targeted)

Dean, Faculty of Education

Lecturer in Indigenous Health (Identified)

Social Media Producer

PhD Scholarship

TWO WRITING TEACHERS

A meeting place for a world of reflective writers.

“I Feel Like a Real Writer:” Supporting Gifted Students in Writing

“Lucky you! You’ve got gifted kids.They GET IT.”

You’d think working with gifted students would be a smooth, easy road, like those highways in Nevada whose view is unbroken by anything but horizon.

Let’s get real. Our road has speed bumps – plenty of them. If I had my way, gifted education would be a part of the special education spectrum. That, however, is a different soapbox for a different day.

We can, however, dispel a key myth. Not all gifted readers are strong writers. Even kids who are great with words are plagued by any number of factors. Some wrestle the many-headed hydra of perfectionism. Others have an abundance of ideas but no clear strategies for wrangling those thoughts into writing. Still others are victims of impostor syndrome, wrongly comparing themselves to others and continually falling short. Writing instruction for gifted students is as affective as it is skill-based.

We had another obstacle, a familiar one: COVID. No longer was I able to work right alongside my “loveies.” Despite our district being in-person since August, I was required to hold classes via Zoom to keep classroom “bubbles” intact.

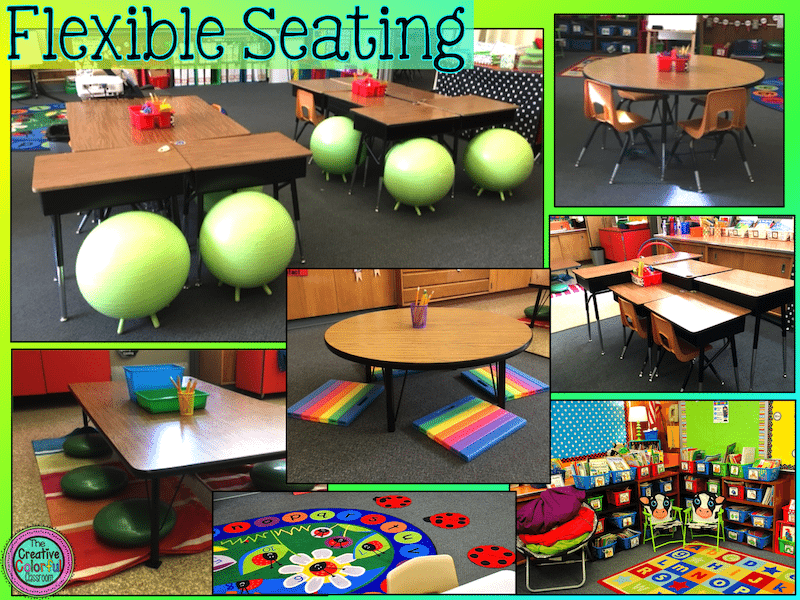

If we wanted a writing community, we’d have to move beyond flair pens, clipboards, fancy paper, and flexible seating. We’d need a safe place to share writing, where students could gather articulate feedback, and learn the joy of cultivating a responsive, positive readership. Where kids see themselves as writers and enjoy the craft of it.

In short, I wanted what I had through the Slice of Life community: Joy. Love of craft. Validation.

Opening the Gates: Establishing Safety and Community

As a class, our first order of business was to create the time and space to craft in the modes and genres we loved most. At the end of each day, students posted screenshots or photos of a passage they felt proud to have written that day, and complemented at least three other writers.

Like cats coaxed from under the bed, most grew more comfortable composing. Once I had them writing, I wanted kids to feel the pride of having others read and appreciate their work.

I started with home-grown mentor text: the comment section on my own blog. We identified types of feedback to share: compliments, encouragement, connections, quotes from text, and literary analysis. They did not disappoint.

We had one hard and fast rule: no critique (yet).

Of course kids wanted to make suggestions. (Did I mention that many gifted students feel strongly about “right” ways to do things?) I steered them in a different direction, once again using Slice of Life as the example.

Consider: In our blogging community, how often do readers leave unsolicited advice or suggestions? Just about…never. We trust one another as writers, which allows us to trust OURSELVES as writers.

Slowly but surely my kids realized they were writing for a genuine audience of peers. I couldn’t ask for more.

Well…perhaps I could.

Revision: The Elephant in the Room

“If no one offers corrections, how can students improve their work?”

I can’t get around it: students need to develop writing skills. Even some of the most talented writers still have hair-graying spelling and conventions.

I started with a self-paced “Fiction Dojo” on the Schoology app. Kids “leveled up” by revising or editing a single area such as capitalization, dialogue, or balance of narration. Students needing support worked with me in breakout rooms.

I learned quickly the “Dojo” system didn’t translate exactly as hoped. Not every student needed to review every single level, and some needed to complete “belts” out of order in the interest of sense-making.

It was the universe’s sneaky way of reminding me to TRUST my WRITERS. After each revision, students often asked what they “should do next.” Sometimes I gave that guidance, but mostly I said, “I trust your judgment. What do you think your readers need from you?”

What happened, in turn, was the crafting of stories that were more strongly edited and revised than I ever could have accomplished through individual conferencing and assignments.

As for building critique back in, I’ll confess I’ve never had much luck with peer conferences. My kids have a tough time directing that conversation regardless of structure. No chart or questionnaire has ever fit.

And then it hit me. CROWDSOURCING.

What wisdom from the “hive mind” did they need? A title? Character names? Help making a scene better or more readable? Putting these questions in the hands of WRITERS, seeking feedback from READERS, made the most sense.

Friends, it was magic. Writers trusted themselves to know what they needed help with, and they trusted their peers enough to support without judgment.

Looking Ahead

I think I’m onto something here. Even my most reluctant writers have more confidence and joy in writing than I’ve ever seen. Throughout the coming weeks and into next year, I’m looking for ways to strengthen self-efficacy and community through shared reading and feedback.

Our next area of exploration follows a “what-if.” What if we use STUDENT writing as mentor text? What if we use students’ writing as a basis for book clubs, for literary analysis? Would that encourage students to further develop their craft? Would it engage them more deeply in reading and conversations about text? My intuition says yes, and I’m anxious to learn more. In a perfect world, I would farm this strategy out to my mainstream classroom colleagues.

Now, there are still places where my lovies fall short on their writing rubrics. I’ve learned I can’t control all of their conversation or revisions. I’ve discovered there are still places I’d love kids to “get to,” but that’s not my journey.

Sometimes their cars are on that Nevada highway, driving somewhere I never would have imagined, and that destination is quite fabulous.

I’m just glad to be along for the ride.

Share this:

Published by Lainie Levin

Mom of two, full-time teacher, wife, daughter, sister, friend, and holder of a very full plate View all posts by Lainie Levin

7 thoughts on “ “I Feel Like a Real Writer:” Supporting Gifted Students in Writing ”

I cannot wait for next year to start to try all this out! I can only imagine, though, how much planning and ‘inner thinking’ must’ve gone into this! STUPENDOUS! 👏🏼

Thank you! It’s the result of a lot of evolution as a teacher of writing. What’s exciting to me is knowing how much FURTHER we can go!

I remember your posts on “crowdsourcing” and its effects, all stemming from putting writers in the driver’s seat and fostering trust. Invaluable! This collective magic – transformational. That community-building, that sense of belonging – priceless. I also recognize so many truths here regarding the “myths” and what I love best is seeing a teacher stopping to consider what her students really need and thinking out of the box about how to make this happen. No “oh wells” or “I don’t know hows” or “things are MOSTLY ok, so…” but how can I get them where they need to be (any student, all students, for all have gifts) and to love the learning journey. It is an evolutional journey for the teacher as well – try and try again, asking “more” of students AND self. So well-done. I sense your own joy as well as theirs, Lainie. It’s something we all need more of in education – for if teaching is a chore, so will the learning be. Just – bravo!

Like Liked by 1 person

Thank you, Fran! It’s weird, because even though I can acknowledge how far we come, it only makes me realize how much further we CAN go together. As for the stopping to consider my kids, I’m glad we worked so hard to develop community. In years like these, where there is so much NOISE coming at educators, from every direction, the children are always the one to make things worthwhile. They saved me this year, as they’ve done so often in the past. You also make an important point about how teaching and learning should be a joy rather than a chore. A colleague and I were just having that conversation yesterday – that we should ALL be in touch with the things we’re passionate about learning. If we don’t have those things, well…maybe we’re not in the right place. Thanks for your thoughtful feedback, Fran.

Lainie, thank you for a thought-provoking post. As I was reading this, I found myself nodding along and saying, “yes” more than once. I really appreciate how you used the SOL community as a model for what you wanted in your classroom. As I move into a classroom next year after four years out, I’ve been thinking about how I wanted to do the same thing. Your ideas on bringing others into the conversation regarding editing and revising are a definite help as I put together my own plans. Thank you!

Tim, that’s exactly what I hope to do in posts like these – to get readers to nod along and say “Yes!” “Exactly!” It’s my goal to get folks riled up so they’ll want to take an action (little or big) in whatever direction they feel so moved. And Tim, I can’t help but think how lucky your kids are going to be to have you FULL TIME. You get to take those children under your wing, and THAT will be a wonderful thing for this world.

Well, consider me riled! When I think back to the early years of my teaching career, it was books (good books!) that I looked to for inspiration and direction when it came to developing writers. It’s great — beyond great — to have this community and the experience it shares. Thanks for being a part of it!

Comments are closed.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Join Donate

- OUR PROGRAMS

- IN THE NEWS

What Does It Mean to Be “Gifted?”

By Ellen Braaten, PhD

Posted in: Grade School , Parenting Concerns , Pre-School

Topics: Child + Adolescent Development , Learning + Attention Issues

Giftedness. It’s such a loaded word.

Almost all parents think their children are gifted. And in a sense, they’re right. Watching a child grow from an infant into a human who can read, complete math problems, and have friendships seems miraculous. No wonder many parents think this way. Most people use terms like “bright,” “gifted,” “exceptional,” “remarkable,” and “talented” interchangeably, but when a psychologist uses the term “gifted,” we’re usually talking about something that is statistically quite rare.

About 3 to 5 out of every 100 children could be considered gifted. Giftedness in a statistical sense is something that’s very unique. Gifted children can be considered so in a number of areas, including intelligence, creative or artistic abilities, specific academic abilities (e.g., gifted at math), or leadership skills. Although intellectual abilities represent only one type of exceptionality, it would be rare to classify a child as gifted without administering an IQ test.

Gifted children have often been stereotyped as unsociable “nerds,” but research suggests that most gifted children do not fit that stereotype. In addition, being a gifted student is not a guarantee of success in school. For example, the verbal maturity of a gifted child (which might lead a child to dominate class discussions) can be interpreted by some teachers as disruptive or inappropriate. Peers can sometimes be less than supportive of a child who knows the answer to every math problem before anyone else does. I often see children who were never identified as intellectually gifted at an early age, but who by adolescence feel depressed and bored with school. They’ve been labeled as “oppositional” or “lazy” because they’ve failed to complete assignments that they see as “mindless busywork.” Then there is also the possibility that a child can have both above-average intelligence paired with an issue or disorder, such as ADHD . This presents an interesting challenge to the classroom teacher, who must keep a hyperactive, information-hungry child motivated while meeting the needs of the other students.

The special needs of the gifted child have received much less attention than students whose difficulties fall at the other end of the bell-shaped curve. In part, this is because giftedness is not a “disorder” in need of treatment but something to be fostered. However, gifted students are often referred for assessment because something is out of place. In some cases, it’s because a teacher notices that a child isn’t fitting in socially because her intellectual skills set her apart. In other cases, a gifted child may be so far ahead of his age-mates that he already knows much of the curriculum before it is even taught. Their boredom sometimes results in low achievement and grades. In contrast, gifted students can also be quite perfectionistic and may define success as not just getting 100 on a test but getting a 100 plus all the extra credit. Their high standards can lead to a fear of failure and, at worst, feelings of low self-esteem and depression .

By definition, people who are gifted have above-average intelligence and/or superior talent for something, such as music, art, or math. Most public-school programs for the gifted select children who have superior intellectual skills and academic aptitude. Children with a superior talent for something, like arts, drama, or dance, aren’t typically provided with services within the school setting, though there are exceptions as some districts offer special schools for children who are exceptional in the sciences or performing arts.

There are no tests to identify children with a superior talent in music or the arts, because talent is somewhat subjective. However, a number of tests can identify children with superior intelligence. Not surprisingly, these tests are called intelligence (IQ) tests . The most commonly used test for children aged 6 to 16 years is the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC). People argue about what the cutoff should be for giftedness, with some arguing that 5 percent of the population could qualify while others argue that it should be 1 or 2 percent. Some people would define it even more broadly, as being in the top 20% of the population.

Regardless of the cutoff, children who are gifted tend to have similar characteristics which include traits such as:

- Fascination with ideas and a sophisticated vocabulary

- Need to make sure things are done “just right”

- Ability to perceive many sides of an issue

- Ability to think abstractly and metaphorically

- Ability to visualize models and systems

- Ability to learn things almost without a need for being taught, such as learning to read before formal reading instruction

- Concern for early moral and existential issues

Being identified as gifted does not guarantee your child will receive special services in school, as it is not mentioned in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) – the federal law that defines a child’s right to special education and related services. Although schools are not required to provide special services for gifted children, some do, and most programs fall into two categories:

- Enrichment experiences (giving students additional learning experiences without them moving up a grade); and

- Acceleration (placing gifted students in grade levels ahead of their peers).

Enrichment services can occur within the classroom or outside the classroom, such as in a resource-room setting. Sometimes, schools will provide gifted students with mentors outside the school environment. For example, a student who has an aptitude for science might be mentored by a chemist, engineer, or physicist. Some school districts offer special schools for gifted and talented students. These school districts are typically located in large metropolitan areas.

Because there is no standard definition of gifted and talented, each state has its own criteria for identifying students and providing services. Some states provide no special services at all.

If you think your child might be gifted, you could start by talking to your child’s teacher or principal to discuss options for testing your child and possibilities for specialized programming. Even if your school doesn’t provide services, testing can be helpful. If testing indicates your child is gifted, you can enroll him or her in after-school programs. Most metropolitan areas have programs that are offered through museums, community education centers, or universities. Overall, gifted students benefit from learning by self-discovery and exploration, and acquiring skills through intuitive reasoning instead of rote memory and drill. They also need opportunities to socialize with peers and need to be encouraged to pursue activities in which they feel challenged.

The following resources are recommended if you would like more information about giftedness:

- National Association for Gifted Children

- Council for Exceptional Children

- The Association for the Gifted

Share on Social Media

Was this post helpful?

Ellen Braaten, PhD

Ellen Braaten, PhD, is executive director of the Learning and Emotional Assessment Program (LEAP) at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), an associate professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School, and former co-director for the MGH Clay Cente...

To read full bio click here .

Related Posts

Bright Kids Who Can’t Keep Up

How Do I Know If My Child Needs Testing?

Teaching for the Test or Teaching for Real Life?

Subscribe today, your monthly dose of the latest mental health tips and advice from the expert team at the clay center..

Quick Jumps

7 Ways to Differentiate Lessons for Gifted Students

Written by Victoria Hegwood

Set engaging, differentiated and standards-aligned assignments with Prodigy Math for free!

- Teaching Strategies

What does “Gifted” mean?

- Why differentiate instruction for talented students?

- 8 Differentiation strategies for gifted students

1. Create tiered assignments

2. shorten the explanations.

- 3. Flexible apps

- 4. Offer open-ended and self directed assignments

- 5. Introduce project based learning

- 6. Compact curriculum

7. Pair gifted students up

8. always keep learning, gifted education pitfalls to avoid.

- Creating a learning environment for every student

All students are unique and special in their own way. Each learns in a different way and needs their education to be individualized.

But differentiating lessons for gifted students can require even more thought and extra planning.

Gifted learners tend to go through their learning activities rapidly and require modifications to their education for them to be fully engaged in the classroom.

If you’re struggling to know exactly how to differentiate lessons for gifted students, this is just the article for you. We’ll highlight instructional strategies to use that will meet your student’s need for enrichment in the classroom, as well as pitfalls to avoid.

The National Association for Gifted Children defines gifted as “ students with gifts and talents performed or capable being performed at higher levels compared to others the same age, experience, and environment. ”

If your school has a gifted program, they likely also have their own definition and benchmarks that qualify a student as gifted. It is important to note that there is not a unified definition from all the states concerning what gifted means.

Gifted students are seen across all racial, socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds.

And there is no one behavior or skill set that defines a gifted learner. Some are gifted in athletics or leadership while others are gifted in the sciences or social skills.

Why is differentiated instruction needed for talented students?

Gifted students are often bored in a typical classroom. This can result in them just zoning out of the lesson or misbehaving. In situations where gifted students are left unchallenged for long periods of time, the students may never learn how to learn in a classroom.

These students need unique opportunities to analyze, evaluate, create and reflect in challenging ways. Differentiating the lesson according to their strengths can help make this happen.

Building differentiated lessons is about the philosophy and practice rather than a strict step-by-step process. You can tweak this practice to match your students’ readiness, interest, learning styles and academic needs.

In general, differentiating lessons is a helpful strategy for all student learning. Education scholar Carol Tomlinson emphasizes, “ Differentiation really means trying to make sure that teaching and learning work for the full range of students .”

However, this article will specifically focus on why it’s necessary for gifted students. When a student is contemplating skipping a grade but isn’t quite ready to make the leap or is only gifted in a particular subject, differentiated lessons are a great solution.

8 Differentiation strategies for gifted learners

There are a lot of ways to use differentiation with a lesson. Different approaches will likely work better for a particular topic or student. Here are some ideas to get you started.

Tiered assignments allow learners to complete the same assignment at different levels of difficulty.

How you implement this strategy will vary based on your classroom. For example, you may design an assignment for the middle tier of students and then add additional challenges for gifted students.

Another option is designing a more difficult assignment and then adding scaffolding, such as a graphic organizer or supplied reading material, to those at or below grade level.

With this strategy, it is important to routinely assess your students to understand where they are at. This way you will always know who needs advanced content and who needs more help.

Did you know?

If you're teaching math to students in 1st-8th grade, you can use Prodigy's Assignment tool to easily set tiered exercises. With your free teacher account , simply select the skill you want to set as an Assignment and have your students play Prodigy Math .

And the best bit? You won't have to do any grading, it's all done automatically!

Gifted students typically understand a concept the first time it is explained, whereas their peers may need the content to be taught a few different ways.

Try giving a short pre-assessment or a pop quiz once you have taught the concept one time to see if the gifted students can move on to the next topic.

Doing this will hopefully prevent boredom and, in turn, misbehavior from gifted students.

3. Use flexible apps

When bringing technology into your classroom and blending the learning experience , choose apps and games with flexibility. Look for options where gifted students can work on more complex concepts while other students work closer to grade level.

There are plenty of apps, like Prodigy Math , that engage students and evaluate their skills to determine if they are learning math problems at the right level. Prodigy Math then uses adaptive algorithms to continue to challenge the student.

Apps like this can also help strain teachers less when planning differentiating lessons since they don’t have to design the tiers themselves.

4. Offer open-ended and self-directed assignments

Open-ended tasks are great for differentiated lessons because they leave plenty of room for students’ skills and ideas to shine. They are especially good at stimulating higher-order thinking skills such as problem-solving.

Self-directed assignments give gifted learners responsibility for their own development and let them decide how far they want to take their own learning. Assignments with open-ended questions encourage students to offer creative responses, work in small groups and build other ways to further explore. But make sure you deliver open-ended sessions with an end goal rather than leaving the students alone.

5. Introduce project-based learning

Project-based learning is effective since it mimics the real world. In a project-based assignment, learners conduct research, ask complex questions and improve management skills. Oftentimes, projects end with a presentation, which is great for practicing public speaking.

Projects can be completed in small groups or by each student individually. This learning method is especially beneficial for gifted learners due to its depth, student choice, real-world learning and collaboration opportunities.

Project-based learning tends to go over the best when the assignments relate to a student’s interests. For example, a high school student interested in social studies could be tasked with designing advocacy around an issue of their choice.

6. Try a compact curriculum

A compact curriculum is similar to shortening explanations, but it will actually throw out whole lessons that the gifted student already understands. Instead, the gifted student will be given lessons on content they’ve never been exposed to.

Most often in this method, students will be given a pre-test that allows them to show mastery over various problems. Then, the curriculum is adjusted.

It’s important to remember that curriculum development for gifted students is a dynamic process.

Another strategy is being more intentional in how you pair students up in collaborative projects. Putting gifted students together in cluster groups boosts their achievement since they are able to work at a faster pace.

You may even find that in specific subjects, students that are gifted in that area can be paired up for their own differentiated lesson while you teach the rest of the class. These pairs can work on advanced content and learn from each other.

Teaching requires constant innovation and growth with a new classroom of kiddos each year. You will always be tweaking what you are doing based on new things that you learn.

In the last two years, the pandemic has required flexibility and accelerated digital learning in ways we had never seen before.

The challenges that came with this got teachers talking and opened up a dialogue about what learning strategies work. It created a community where more experienced teachers could impart their knowledge to others.

Here's more strategies and ideas to help you differentiate learning

Looking to learn more about differentiation? Check out our list of 20 differentiated instruction strategies for more inspiration on how to level educational content in your classroom, with examples included!

As with any strategy, there are ways to do it well and ways to do it that are not so great. Try to avoid these three common mistakes when differentiating lessons for gifted students.

1. Using gifted students as teaching assistants

While gifted students may seem like a great help in the classroom, they should not be tasked with mentoring or tutoring other students. They need to be challenged in their own education and reteaching a concept that they already know doesn’t do that.

A different way to go about this is having flexible grouping projects that let students work together for a short period of time. These projects allow gifted students to practice interacting with their peers and allow other students to learn from gifted students, but it’s temporary.

This method allows gifted students to learn and avoids attaching a ‘teacher’ role to their interactions.

2. Working independently without oversight

A differentiated lesson for gifted learners should lead to more collaboration and content enrichment without the learner working constantly on their own. Assigning open-ended tasks without oversight or accountability can actually have the opposite effect of what you’re going for with gifted learners.

Ensure that lessons allow for student choice while still conforming to school district standards. And check in often with your gifted students.

3. Assuming mastery in all subject areas

Don’t assume that just because a learner is gifted in one area means that this means they are gifted in every area. For example, a student may be reading at a high school level but is not a strong writer. Or they may excel at math problems but struggle to understand graphs in science.

Evaluate each subject area individually before assigning advanced lessons to gifted students.

Creating a learning environment for everyone

Differentiated lessons can be a great tool for gifted students in your classroom. But there are best practices to keep in mind when you’re constructing lessons. Differentiating lessons helps challenge gifted students and keep them engaged in your classroom.

If starting the process of planning differentiated lessons feels overwhelming to you, using Prodigy can be a great first step.

Whether you’re teaching in a math or English classroom, Prodigy is a fantastic free teaching resource that customizes each student’s experience with adaptive content.

Prodigy helps make it easier for you to differentiate instruction across your classroom, with no grading required! Teachers simply select what curriculum-aligned skills they'd like to test on their students or let Prodigy's adaptive algorithm assign content to help a student grow, including those in gifted or talented strands.

It's also free for teachers and schools! See how it works below:

- About InterGifted

- Meet Our Leadership

- Vision, Mission & Values

- Privacy Policy

What is Giftedness?

- Audio & Visual Library

- Conversations on Gifted Trauma Podcast

- Qualitative Giftedness Assessments

- What Our Clients Say

- Integration, Coaching & Mentoring

- Gifted Therapy

- Coaching FAQ’s

- Courses, Workshops & Groups

- Gifted Psychology Training

- Gifted Mindfulness Courses

- What Our Participants Say

- Online Peer Community

- What Our Members Say

- Community FAQ’s

- Gifted Mindfulness Collective

Gifted people's minds range from being somewhat to extremely complex: intellectually, creatively, emotionally, sensually, physically, existentially or some combination of these factors. Their level of complexity can be both exhilarating and at times challenging, for themselves and for their social entourage. Learn more about what giftedness looks like in real life in the article below, written by InterGifted's founding director Jennifer Harvey Sallin .

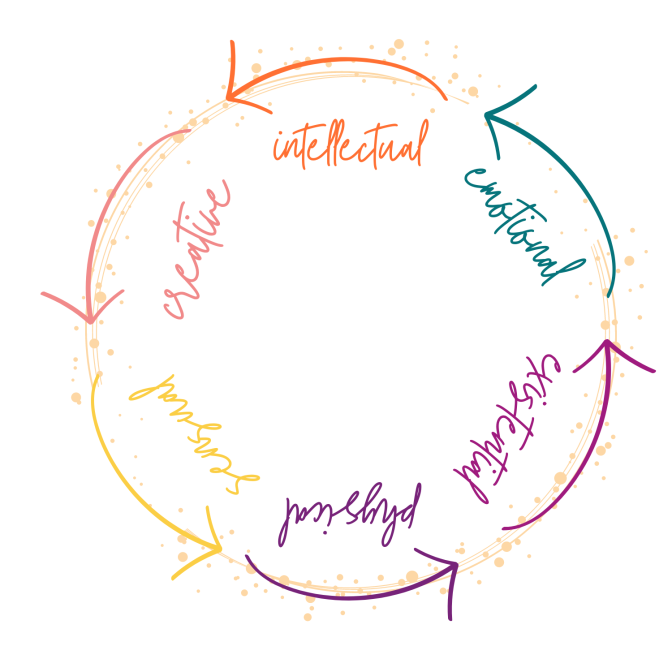

AREAS OF INTELLIGENCE

Typically, the word "gifted" is shorthand for " intellectual giftedness " , but there are various ways any person - gifted or not - expresses their mental faculties. In truth, “giftedness” is a kind of mind construction pattern (neurologically, cognitively and phenomenologically speaking) which results in a complexity of thought (and often emotion) that is uncommon. In our work at InterGifted, we use my holistic model of intelligence, which I have developed in particular with advanced gifted adult development in mind. My model works with six areas of intelligence: intellectual, emotional, creative, sensual, physical, and existential.

INTELLECTUAL

Highly complex and abstract analysis, high focus on knowledge and learning (not always expressed in conventional ways, i.e. through conventional education), unusual skill in complex problem solving, asking probing and deep questions, searching for truth, understanding, knowledge, and discovery, keen intellectual observation and sustained intellectual effort.

Highly complex and deep emotional feelings and relational attachments, understanding a wide range of emotions, strong memory for feelings, often expressing a high concern for others, heightened sense of right, wrong, injustice and hypocrisy, empathy, responsibility, and self-examination.

Highly complex capacity for seeing and expressing the unusual, new, unseen, innovative, divergent and possible. This often manifests in uncommonly strong skills of imagination and visualization, music or arts, and even humor or playfulness (though not always about themes considered "light" - i.e. quirky or dark humor).

Highly complex awareness and experience of the senses (visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, tactile or energetic), often resulting in a deep and nuanced sensual relationship to the world. This can manifest in an uncommon appreciation of beauty, harmony, and the interrelationship between the sensorial elements of life.

Highly complex physical skill or dexterity (i.e. excellence in sports or the technical aspects of music-making). This can also manifest in an unusually complex understanding of the physical elements of reality and their interrelations, such as physics and biology knowledge .

EXISTENTIAL

Highly complex awareness and experience of being, meaning, values, ethics, morality, ecological interconnectedness, and the nature of reality (often including a transpersonal awareness of reality as well).

An intellectually gifted person has a baseline of intellectual intelligence that is higher than average; how any of the other areas of intelligence combine and interact with with their intellectual intelligence shows in their own unique giftedness "flavor" or "personality". There's also the question of levels of giftedness , which range from mild to profound, and very much influence the expression of giftedness in an individual.

Additionally, there can sometimes be twice- and multi-exceptionalities , such as autism, learning disabilities, or other neurodivergences (in many cases extended to include mental health issues and physical disability), which add certain challenges or additional "flavors" to the expression of one's high intellectual ability. Overexcitabilities , which are areas of uncommonly high intensity (but which are not synonymous with giftedness , as is often believed) add additional flavors of expression.

Other factors, including trauma history and our social context, also affect our gifted development and expression. In other words, giftedness is not a one-size-fits-all concept, and though all gifted people share a baseline of higher than average complex cognition, gifted people make up a very heterogeneous group. This is why it's important for a person to discover their own giftedness profile, as your gifted mind and life is a whole ecosystem with its own particular makeup, context, needs and expression.

RECOGNIZING GIFTEDNESS

Intellectually gifted people represent a small minority of the overall population (opinions differ, but research suggests somewhere below 5%), and this means that gifted people have to face the common challenges of minority development throughout their lives.

Academically, professionally and socially speaking, gifted people often don't follow the conventional paths laid out by the majority. By the time they are adults, they have often studied (formally and/or self-directed) many divergent subjects, and may have frequently changed jobs (once the challenge of learning a role turns to routine, they feel bored and under-engaged). They may have already had three careers at the age of 30, or may have never really settled down to do any career. Or they did settle down, and feel like they have sold out and are struggling. Socially, they may look for and try to create complexity in their relationships, and continue to be disappointed, or see themselves or others as "faulty" because they cannot seem to get the full spectrum of their intellectual and emotional needs met no matter how hard they try. And this is only mentioning the challenges as we see them from the adult's point of view; these all extend, in their own way, to what our challenges were as gifted children.

The issue is that gifted people like exploration, not routine; and they need a lot more intellectual stimulation than is common. For a lot of people, traditional roles, rules and expectations feel good, and create a sense of safety, but many (if not all) gifted people feel imprisoned by routine, tradition, and rules-based contexts. Without the room to try out different roles, stretch and question the rules, be creative and go beyond traditional expectations and limits, gifted people often feel uncomfortable, misunderstood, imprisoned, suffocated, and at the extreme, even existentially panicked. And without adequate intellectual stimulation and depth in their relationships, they may feel themselves going into a kind of hibernation/shut-down; or conversely go into a kind of overdrive trying to get their needs met in contexts and with people who are unable to meet them adequately. Some of what I've described here can actually lead to something we call "gifted trauma". This is such an important topic in a gifted person's development and thriving, that we've dedicated an entire podcast to it, which you can listen to here: Conversations on Gifted Trauma .

GIFTEDNESS ≠ SUPERIORITY

What's difficult about all of this is that many people don't want to see themselves as gifted because it sounds like a question of superiority, and they don't want to believe or feel they are better than others. But while it’s healthy not to see oneself as “special” and therefore “superior”, it is also necessary to recognize and honor the way one’s mind works and when one’s level of complexity is different as compared to the norm. As mentioned above, those who are more complex than the norm but refuse to believe it, risk looking for high complexity in friendships, relationships, discussions, collaborations, roles and systems when it is simply not there; and they risk being disillusioned and blaming themselves or others for the “failure”. They also risk overwhelming non-gifted people with their complexity, and once again blaming themselves or others for the mismatch.

Additionally, if a gifted person is unaware of their authentic academic and professional needs and tries to follow traditional academic or professional goals and routines, they may exhaust teachers, classmates, co-workers, bosses, and even family and friends with their chronic dissatisfaction and need for challenge and stimulation. If they are unusually sensitive, they may be bullied regarding their extreme empathy, extreme sense of justice/injustice, and inability to “go with the flow” or just accept things the way they are, problems and all. Or may even be aware of all of the potential ways they could help others and become a sort of “savior”, losing themselves in cleaning up other people’s messes (sometimes which the other people didn’t even want cleaned, and sometimes to their own detriment).

Another common fear of gifted people is that if they admit their difference from others, it will ruin their relationships with their non-gifted family and friends or somehow jeopardize their place in the non-gifted dominant world. It won't. It will simply help you to communicate more effectively, understand others in your life with more ease, and realize where and with whom you can get your various gifted-specific and non gifted-specific needs met. The essential point is: the better you understand your own mind and functioning, the better you can negotiate the necessary conditions for your thriving. That process takes radical self-honesty. Denial about one's giftedness can be a challenging aspect to overcome, but it is worth the work, as it allows you to come into a real relationship with yourself and with the world and others around you; allowing you to heal old wounds of unmet needs and thus redirect the use of your intelligence toward authentic, holistic and interdependent relating which allows you to meet your needs while honoring the limits of others. If you are somewhere on this fear/denial/acceptance journey, you may find my article on the topic helpful: The Stages of Adult Giftedness Discovery .

Of course, many of us have also known people who are uncommonly intelligent and love to flaunt that fact and use it to embarrass, manipuate or otherwise humiliate others who are less cognitively endowed. These people often have issues to work through as well, as somewhere along the way they learned to use their giftedness as a weapon against others and in turn against themselves. Their relationships suffer and their disconnection, though different in cause from someone who is in "giftedness denial", is very real.

GETTING THE RIGHT SUPPORT

Even gifted people often confuse “giftedness” with “genius”, imagining that "gifted geniuses” have it easy. Gifted people might be “genius” in some ways at certain times (certain aspects of learning are easier for them than for the average), but everyone – including gifted people – must systematically experiment and apply their knowledge over time to succeed, and must have the social and financial support to progress toward their authentic potential.

Giftedness does not result in automatic success: as with everyone and everything, the conditions (inner and outer) must be right for flourishing. When a gifted person's complexity is supported and managed well, they have the proper social mirroring, and the social and cultural context is ripe, they can do amazing things. When it is not managed well and not supported (which given the numbers, is understandable), that same complexity can result in underperformance and failure throughout life. Finding the right support can be a challenge, due to the “complexity mismatch” gifted people sometimes experience when reaching out socially, professionally, and for help and support. This was the main reason I created InterGifted.

WHAT WE DO & HOW YOU CAN GET INVOLVED

Online peer community.

Since 2015, we have cultivated a dynamic online community of 850+ gifted adults around the world, where we explore questions and themes of giftedness integration, self-development and self-leadership together. Our members are conscientious, dedicated gifted adults who are actively learning about and applying their giftedness to their lives in creative and purposeful ways. In our community, you can meet other gifted adults who are invested in their personal and professional growth, and who are ready to connect with other equally dedicated and engaged gifted adults.

JOIN US HERE !

Qualitative giftedness assessments .

Our assessments help you look at whether you are gifted, and if so, what your unique gifted profile is. Knowing how your complex mind works increases your self-understanding and self-compassion and unlocks doors for legitimizing, accepting, and empowering yourself on your self-awareness journey. We see giftedness from a holistic perspective, and assessments explore intellectual intelligence together with body intelligence, emotions, intuitive awareness, creativity, and other forms of intelligence expression.

LEARN MORE & SCHEDULE HERE !

Giftedness integration, coaching & mentoring.

We offer accompaniment and guidance throughout your giftedness discovery, integration and thriving journey. Giftedness integration sessions support you in deepening your understanding of your giftedness and how it guides your development, values, growth, and practical next steps. Coaching and mentoring guide and empower you as you apply and potentiate your giftedness in specific areas of your life, such as career, relationships, community, mindful living and embodying existential meaning.

LEARN MORE & SCHEDULE A SESSION HERE !

Courses, workshops & groups .

Our online courses, workshops and groups have been developed especially for gifted adults, and cover personal and professional self-development themes such as gifted mindfulness, multipotentialite thriving, and neurodivergent living. Our participants are gifted adults who are dedicated to and invested in their own personal growth and to growing together with their gifted peers.

LEARN MORE & SIGN UP HERE !

Gifted-psychology professional trainings.

We're committed to building a dynamic field of gifted-specific psychology. Through her professional trainings, Jennifer Harvey Sallin leads groups of psychologists, therapists, coaches, psychiatrists and other helping professionals to learn more about what giftedness is, how to recognize it in their clients, and how to support gifted clients to heal and thrive across the lifespan. Her trainings are holistic, in that they empower participants to also recognize and nurture their own giftedness, discovering how to integrate it authentically and deeply into their work supporting others.

LEARN MORE & APPLY TO JOIN HERE !

Learn more about giftedness , the intergifted blog .

Here you'll find a large collection of long-form articles by our InterGifted coaches and other professionals in our network exploring the many facets and needs of the gifted adult. Here are some of our most-read articles:

High, Exceptional & Profound Giftedness

Gifted adults, second childhoods: revisiting essential stages of development, living with intensity: giftedness & self-actualization, letting go of gifted shame, the stages of adult giftedness discovery, read more articles here , audio visual resource library.

Here you'll find a large collection of talks, videos, interviews and podcast episodes exploring giftedness, gifted mindfulness, and empowering themes on gifted development and thriving.

WATCH & LISTEN HERE !

Our bookshop.

In our community ebooks, you'll read real stories about the complexities, pains, joys, mysteries and surprises of the gifted adult experience, as told through the essays and artwork of our InterGifted community members.

- These Gifts are Sacred explores the sacredness of gifted complexity, through contemplative poetry and art

- Emergence: Contemplations & Creative Expressions of the Gifted Feminine expresses the power and art of being a gifted woman

- Gifts for an Emerging World looks at how we can embody our gifts to be a positive force in a world full of complex challenges

- Being Me: Reflections on the Gifted Person's Path to Authenticity awakens our capacity to authentically embrace our gifted experience

- Making the Invisible Visible: Intersections of Chronic Illness, Disability and Giftedness gives voice to the struggles, lessons and gifts of complexity and illness

- Embracing the Gifted Quest empowers us to envision and embrace our gifted life as a rich opportunity to live fully

FIND OUR BOOKS HERE !

This page was most recently updated in September 2023

Chapter 4: Student Diversity

Gifted and talented students.

The idea of multiple intelligences leads to new ways of thinking about students who have special gifts and talents. Traditionally, the term gifted referred only to students with unusually high verbal skills. Their skills were demonstrated especially well, for example, on standardized tests of general ability or of school achievement. More recently, however, the meaning of gifted has broadened to include unusual talents in a range of activities, such as music, creative writing, or the arts (G. Davis & Rimm, 2004). To indicate the change, educators often use the dual term gifted and talented .

Qualities of the gifted and talented

What are students who are gifted and talented like? Generally they show some combination of the following qualities:

- They learn more quickly and independently than most students their own age.

- They often have well-developed vocabulary, as well as advanced reading and writing skills.

- They are very motivated, especially on tasks that are challenging or difficult.

- They hold themselves to higher than usual standards of achievement.

Contrary to a common impression, students who are gifted or talented are not necessarily awkward socially, less healthy, or narrow in their interests—in fact, quite the contrary (Steiner & Carr, 2003). They also come from all economic and cultural groups.

Ironically, in spite of their obvious strengths as learners, such students often languish in school unless teachers can provide them with more than the challenges of the usual curriculum. A kindergarten child who is precociously advanced in reading, for example, may make little further progress at reading if her teachers do not recognize and develop her skill; her talent may effectively disappear from view as her peers gradually catch up to her initial level. Without accommodation to their unusual level of skill or knowledge, students who are gifted or talented can become bored by school, and eventually the boredom can even turn into behavior problems.

Partly for these reasons, students who are gifted or talented have sometimes been regarded as the responsibility of special education, along with students with other sorts of disabilities. Often their needs are discussed, for example, in textbooks about special education, alongside discussions of students with intellectual disabilities, physical impairments, or major behavior disorders (Friend, 2008). There is some logic to this way of thinking about their needs; after all, they are quite exceptional, and they do require modifications of the usual school programs in order to reach their full potential. But it is also misleading to ignore obvious differences between exceptional giftedness and exceptional disabilities of other kinds. The key difference is in students’ potential. By definition, students with gifts or talents are capable of creative, committed work at levels that often approach talented adults. Other students—including students with disabilities—may reach these levels, but not as soon and not as frequently. Many educators therefore think of the gifted and talented not as examples of students with disabilities, but as examples of diversity. As such they are not so much the responsibility of special education specialists, as the responsibility of all teachers to differentiate their instruction.

Supporting students who are gifted and talented

Supporting the gifted and talented usually involves a mixture of acceleration and enrichment of the usual curriculum (Schiever & Maker, 2003). Acceleration involves either a child’s skipping a grade, or else the teacher’s redesigning the curriculum within a particular grade or classroom so that more material is covered faster. Either strategy works, but only up to a point: children who have skipped a grade usually function well in the higher grade, both academically and socially. Unfortunately skipping grades cannot happen repeatedly unless teacher, parents, and the students themselves are prepared to live with large age and maturity differences within single classrooms. In itself, too, there is no guarantee that instruction in the new, higher-grade classroom will be any more stimulating than it was in the former, lower-grade classroom. Redesigning the curriculum is also beneficial to the student, but impractical to do on a widespread basis; even if teachers had the time to redesign their programs, many non-gifted students would be left behind as a result.

Enrichment involves providing additional or different instruction added on to the usual curriculum goals and activities. Instead of books at more advanced reading levels, for example, a student might read a wider variety of types of literature at the student’s current reading level, or try writing additional types of literature himself. Instead of moving ahead to more difficult kinds of math programs, the student might work on unusual logic problems not assigned to the rest of the class. Like acceleration, enrichment works well up to a point. Enrichment curricula exist to help classroom teachers working with gifted students (and save teachers the time and work of creating enrichment materials themselves). Since enrichment is not part of the normal, officially sanctioned curriculum, however, there is a risk that it will be perceived as busywork rather than as intellectual stimulation, particularly if the teacher herself is not familiar with the enrichment material or is otherwise unable to involve herself in the material fully.

Obviously acceleration and enrichment can sometimes be combined. A student can skip a grade and also be introduced to interesting “extra” material at the new grade level. A teacher can move a student to the next unit of study faster than she moves the rest of the class, while at the same time offering additional activities not related to the unit of study directly. For a teacher with a student who is gifted or talented, however, the real challenge is not simply to choose between acceleration and enrichment, but to observe the student, get to know him or her as a unique individual, and offer activities and supports based on that knowledge. This is essentially the challenge of differentiating instruction, something needed not just by the gifted and talented, but by students of all sorts. As you might suspect, differentiating instruction poses challenges about managing instruction.

Davis, G. & Rimm, S. (2004). Education of the gifted and talented, 5th edition . Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Friend, M. (2007). Special education: Contemporary perspectives for school professionals, 2nd edition . Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Schiever, S. & Maker, C. (2003). New directions in enrichment and acceleration. In N. Colangelo & G. Davis (Eds.), Handbook fo gifted education, 3rd edition (pp. 163–173). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Steiner, H. & Carr, M. (2003). Cognitive development in gifted children: Toward a more precise understanding of emerging differences in intelligence. Educational Psychology Review, 15 , 215–246.

- Educational Psychology. Authored by : Kelvin Seifert and Rosemary Sutton. Located at : https://open.umn.edu/opentextbooks/BookDetail.aspx?bookId=153 . License : CC BY: Attribution

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

- Tarzana Campus

- Los Angeles Campus

- Pomona Campus

- Harvard Campus

- Pasadena Campus

- Oak Park Campus

- OCA in the News

- Parent Association

- The Gifted Child

- Is OCA Right For Your Child?

- Testimonials

- COVID-19 Protocal

- Privacy Policy

- Our Approach

- OCAIL Tuition

- Apply Online

- Policies and Refunds

- College Information

- International Program

- Accreditation

- Matriculation

- Take a Tour

- Application Process

- Gifted Testing

Six Types of Giftedness

By Oak Crest Academy

- Gifted Children

What does “ gifted ” mean? The term has likely evolved since you were a child. What does it mean to be gifted? Most people might reply that a “gifted” child is one who earns straight A’s, performs well on the Iowa Basics , or can solve quadratic equations late into the night. While these are forms of giftedness, defining gifted as “good at school” is outdated and far too narrow. Here are six different types of giftedness .

This is the traditional understanding of gifted children: they’re good at school. “Successful” gifted children are obedient in class, do homework without a lot of prompting, test well, and may become perfectionists . Unfortunately, these children might face jealousy from some peers due to being “teacher’s pet.” But in general, most of them are well-adjusted goal-setters.

Successful gifted children do well on tests such as the SAT/ACT. They usually aim for higher education and advanced degrees as they journey through their academic lives. For the most part, they tend to be structured thinkers. Successful gifted children might be able to generate a story or drawing when asked, but creativity is not their strength. Still, they are typically well-rounded and may still perform music or produce art projects, although they may not show much interest in composition or abstract thinking.