Cancel Culture and Other Myths

Anti-fandom as heartbreak.

A friend is about to give a guest lecture. She is paralyzingly nervous: “I don’t want to get canceled.” A colleague who is about to have an editorial published asks me to make sure there is nothing cancelable in it. When their work occurs without incident, I return to the terror that preceded their success. “You see, you weren’t canceled!” “Thank god,” they both reply, an oddly unifying utterance for two professed nontheists. The stakes of canceling are such that disbelievers reach for higher powers when spared.

I begin to ask everyone I meet what they think of when they think of cancel culture. A student tells me her grandparents complain, “It’s Salem all over again.” A friend tells me of a colleague who got fired for something they said on Slack. “Can you believe it?” she snaps. “Cancel culture ruins lives.”

I gather these instances and wonder whether cancel culture is an encroaching menace against which everyone must defend or a moral panic that inflates the problem. In a 2023 paper published in Political Studies , Pippa Norris poses the question this way: “Do claims about a growing ‘cancel culture’ curtailing free speech on college campuses reflect a pervasive myth, fueled by angry partisan rhetoric, or do these arguments reflect social reality?” 1 Norris finds that contemporary academics may be less willing to speak up due to a fear of cancel culture. Cancel culture is not a myth, Norris decides, because, in silencing people, it does something real.

There is no question that cancel culture is real. It is also a myth.

Taking myths as real requires resistance to conventional usage. Seven myths about COVID-19 vaccines , yells one headline. Ten mega myths about sex , beckons another. Myth used this way refers to an idea people believe that is not true. This is a relatively recent connotation of myth. In the history of religion, myths are stories people tell about forces more powerful than them described as superhuman. A superhuman force could be a god; it could be meteorology; it could be a corporation or a foreign state. Myths occur when human beings want to explain how mysterious things come to pass. Their explanation is: “Something more powerful than us did something to make this happen.”

Cancel culture produces a collection of myths within a particular tradition or a mythology. Depending on your political inclinations, the cast of gods and heroes alters considerably. The question is what mystery cancel culture’s mythology explains. Thinking about this requires thinking a little about religion, and a lot about what hurts people most.

Why does cancel culture feel so weighty when its material impacts are so comparatively slight?

The history of religions is a history of organizing power relations. If this premise isn’t especially sexy to you, I commend the many Netflix films about religion where you can watch charismatic figures lull followers with promises of new dawns and off-the-grid togetherness. A lot of people who Netflix and chill do not identify religiously, but everybody knows a heartbreak authored by a devastating player. “Something in the way you move / Makes me feel like I can’t live without you,” sings Rihanna in “Stay,” her 2012 blockbuster duet with Mikky Ekko. This is just one of hundreds of lovelorn tracks from the Top 40 that would serve well as a soundtrack for religion’s depiction in Keep Sweet: Pray and Obey (2022), Unorthodox (2020), and Wild Wild Country (2018).

Religion has a fair number of sexual mountebanks, but for a new religious movement to become an established religion, it needs to evolve from one-hit wonder to Beyoncé. New religious movements, sometimes derogatively called cults, offer ritual resolve for persons seeking solutions to their most profound questions and pain. Religions evolve from small cultic movements when, after the initial romance fades, individuals keep repeating things that other individuals repeat, and those communal repetitions come to constitute a form of belonging. If I say the Lord’s Prayer, the Jewish blessing over bread, or the Muslim salat, I am speaking individually, but I am speaking in a way many other people speak, and when we hear each other speak it, we know who we are. The person who shows up at a Beyoncé concert and does not know a single lyric seems, to the Beyhive, like an outsider.

In her work on cancel culture, Pippa Norris does what many people do who imagine themselves outside myth’s power, namely take a myth as opposed to reality. But when you define a myth as a falsehood, you are not working to hear the myth’s believers on their terms. You are trying to correct them. You are trying to divest their false belief of its power. Religionists have a word for that, too: secularization .

The historic use of secularize was to convert from religious to secular possession or use, as when someone says, “the convent, secularized in 1973, is now a conference center.” Secularizing a building can happen with a single ritual. But calling someone else’s belief a lie—saying that there was no virgin birth, for example—doesn’t work so easily. Your cousin who won’t get vaccinated, the co-worker who repeats old lines about Pizzagate. No amount of fact-checking their utterances alters their view, because their view is not about the vaccine’s reality. It’s about how they feel when higher powers like The Government and Big Pharma required it. The more you deny what the believer believes, the bigger, not smaller, their belief becomes. Your debunking energizes their storifying. Have you ever tried to convince a Beyoncé fan that her voice isn’t that great, or that Rihanna is the better live performer? For sure you lost that one.

the mystery that I want to solve is why the idea of cancel culture is so powerful. In a 2020 essay addressing cancel culture, Ligaya Mishan writes, “It’s instructive that, for all the fear that cancel culture elicits, it hasn’t succeeded in toppling any major figures—high-level politicians, corporate titans—let alone institutions.” 2 This lack of large-scale monetary or institutional consequence has not dimmed the anxious hold that cancel culture has on the political conversation. Why does cancel culture feel so weighty when its material impacts are so comparatively slight?

Alan Dershowitz’s Cancel Culture: The Latest Attack on Free Speech and Due Process (2020) identifies cancel culture as the “illegitimate descendent” of both McCarthyism and Stalinism and blames it for stifling political free speech and artistic creativity as well as derailing the careers of prominent politicians, business executives, and academics. 3 For Dershowitz, the weight of cancel culture is how it silences debate and destroys individual careers. And yet this is wrong: never in human history have human beings been less silent or debated basic ideas of interrelation and power more.

The friend and colleague who worried to me about their possible cancelations fretted because they thought they could lose job opportunities if they became stars of a story where they are called out for using their power at the lectern or on the page toward negative effects. There are prominent instances in the cancel culture mythology of this occurring. Amy Cooper, a white woman who threatened a Black male birdwatcher, Christian Cooper, lost her job after the video of their Central Park encounter went viral. For Dershowitz and others who weaponize cancel culture, Amy Cooper’s firing is a prime exhibit that cancel culture has real effects.

There is no disputing that the behavior that led to Cooper’s firing occurred. The tape exists. She flipped out, and when she did, she pulled on racist language to do so. This is neither the first nor the last time someone was fired for behaving badly. Is using a wrong word in a lecture or a sentence in an editorial akin to behaving badly? No. Is it grounds for criticism? Yes. A part of the sign that cancel culture controls the mythological portion of the contemporary shared social imagination is that it has convinced many people that criticism is itself a condemning act. To watch the video of Amy Cooper is to watch a person who could not take criticism in the moment of her meltdown. She doubled down in her ardency that she was in danger despite the reassurances that she was not. After she was fired, she did not author a public apology; she sued her employer for wrongful termination. She lost. Dershowitz would wager the woke mob had taken over her company’s Board of Trustees. A scholar of religion might observe she did not engage well the superhuman powers her virality offered her.

Language is the gladius in the battle royale cancel culture stages. Kevin Donnelly, editor of Cancel Culture and the Left’s Long March (2021), describes the endangering effect of cancel culture as a “radical reshaping” of “language.” He complains that “under the heading of ‘equality, diversity, and inclusion’ academics and students are told they cannot use pronouns like he or she.” He continues: “Other examples of cancel culture radically reshaping language to enforce its neo-Marxist inspired ideology include replacing breastfeeding with chest feeding so as not to offend trans–people” and deciding words like elderly and pensioners are “ageist.” He concludes: “While the above examples might appear of little consequence, the reality is the way language is being manipulated is cause for concern.” 4

Celebrities know that to sustain their power they must cede some of what people say they are, including what people accuse them of being, even if mistaken.

Donnelly’s argument involves questionable assertions. Academics and students are not instructed in one hegemonic or unifying way; nobody is told what pronouns to use for themselves. But he is correct that a phobia that you will get the words wrong is one of the most basic terrors a person can have. Conservative critics have had such fearmongering traction with cancel culture because it taps into the primal embarrassment about saying the wrong thing. Cancel culture is therefore unsurprisingly marked as connected to contemporary campus life and, specifically, the humanities, where the fluency and acuity with language are curricular foci.

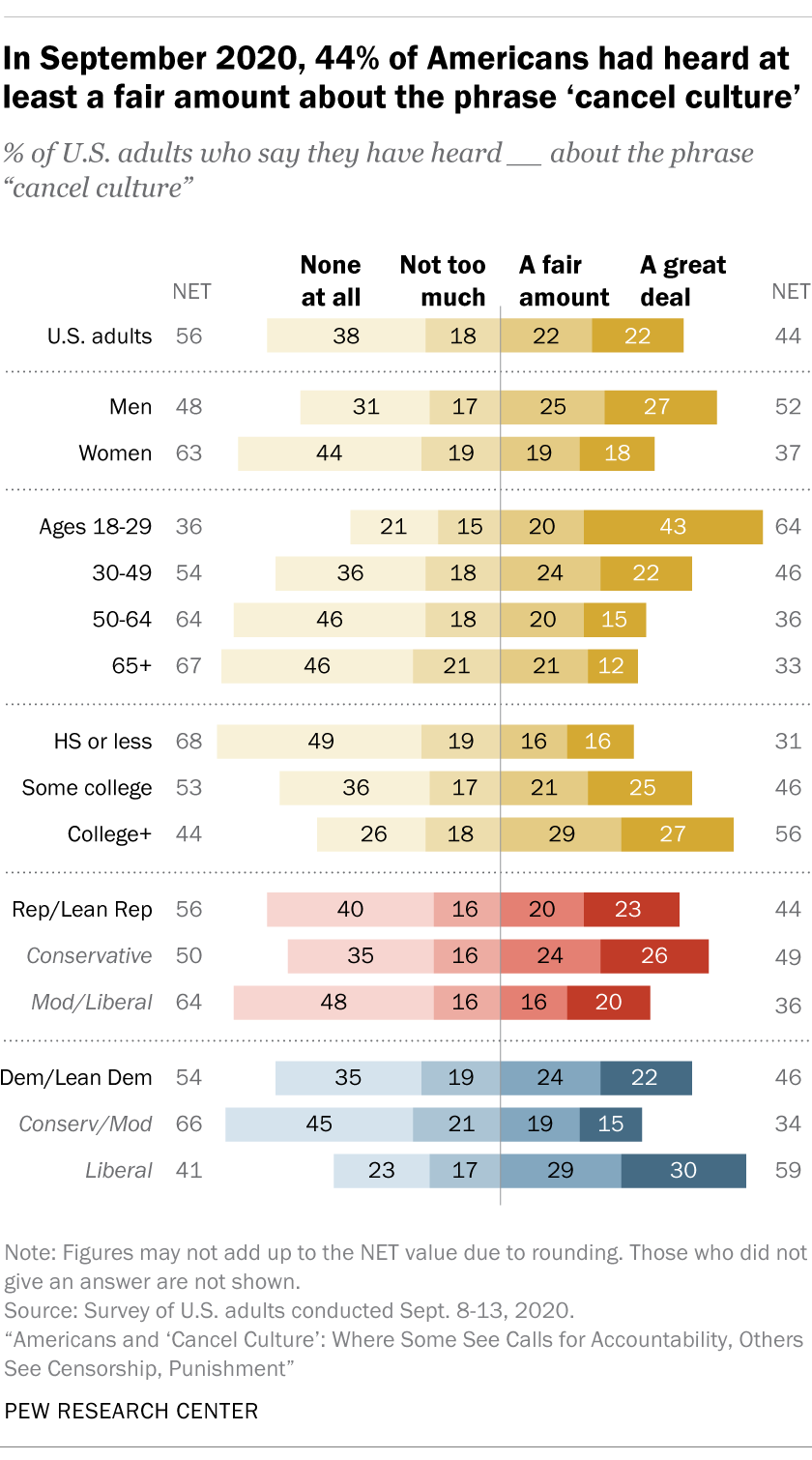

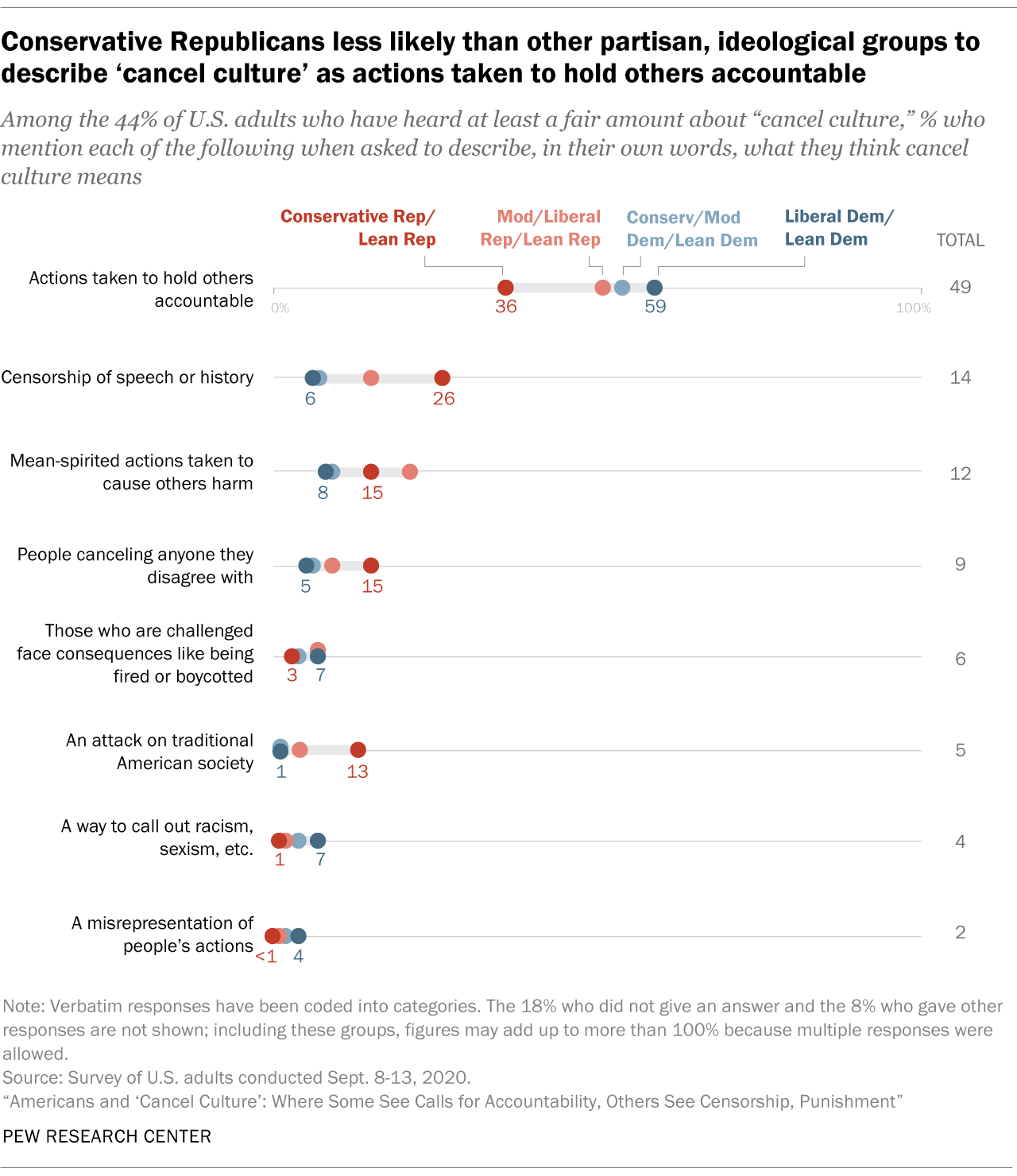

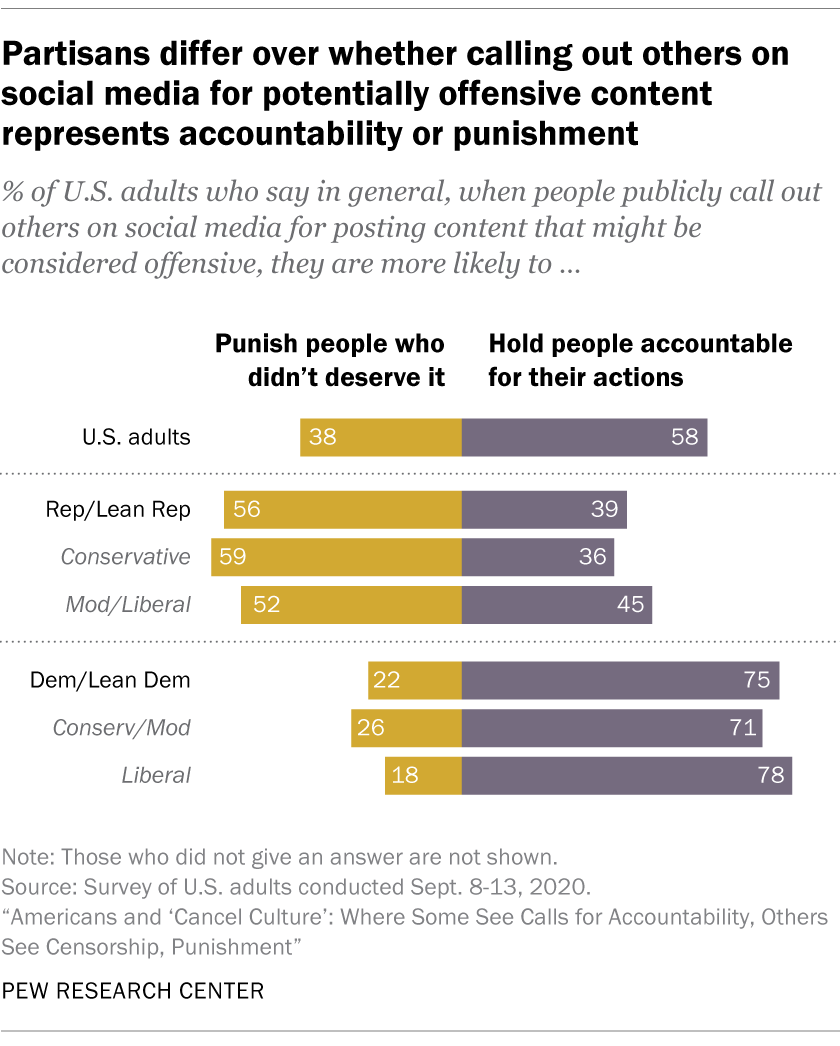

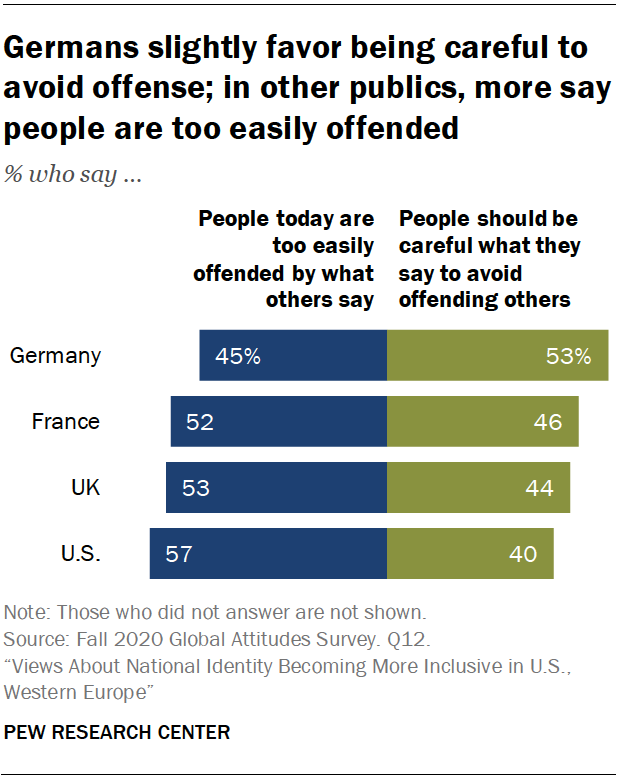

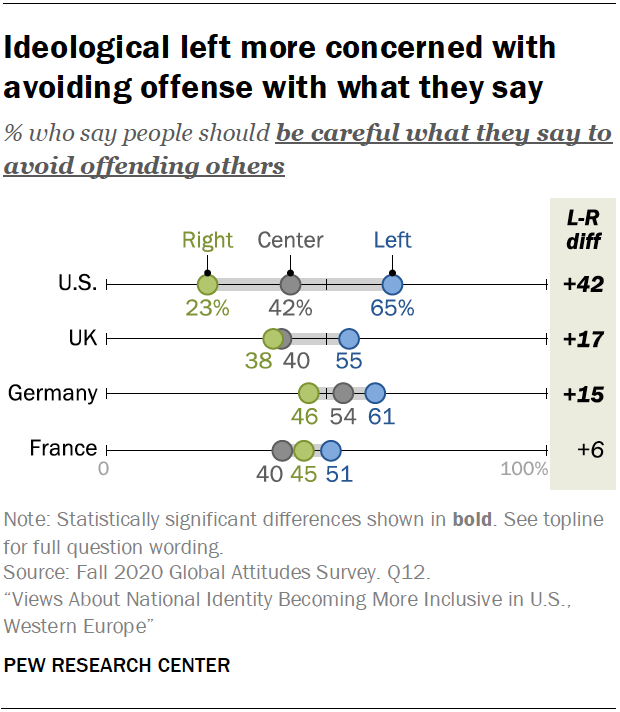

Critics on both sides of the political aisle wail about the heartlessness of cancel culture’s quick-condemning appraisals. A conservative Republican male-identified person replying to a recent Pew survey about the relationship between political vantage point and perception of cancel culture’s threat defines cancel culture as “destroying a person’s career or reputation based on past events in which that person participated, or past statements that person has made, even if their beliefs or opinions have changed.” A Democratic male-identified person defines it as “a synonym for ‘political correctness,’ where words and phrases are taken out of context to bury the careers of people. A mob mentality.” This Republican and this Democrat agree that cancel culture gives no leeway for learning (“even if their beliefs or opinions have changed,” says the Republican) and no understanding of the specific situation (“taken out of context,” says the Democrat). 5 People are angry about cancel culture because it imprisons with no time off for good behavior. But discomfort around cancel culture may have less to do with absent compassion and more to do with who is now doing the talking and the canceling. As Danielle Butler wrote for The Root in 2018: “What people do when they invoke dog whistles like ‘cancel culture’ and ‘culture wars’ is illustrate their discomfort with the kinds of people who now have a voice and their audacity to direct it towards figures with more visibility and power.” 6 As it happens, the Pew survey respondents are not racially identified. Butler invites us to wonder whether they were white people uncomfortable with being subject to nonwhite critique.

We might be able to frame cancel culture, then, in a different way: as a kind of fan rebuttal to the running story. The scholar Eve Ng writes, “Fandoms have a long history of organizing mass efforts around media texts, especially television shows, whose narratives and other elements of production might be influenced by viewer preferences.” 7 The viewer—of a TV show or a viral clip, say—directs what happens next through their reaction. Ng points out that cancel culture reflects larger patterns of social hierarchy, including gender, class, race, nation, and other axes of inequality. She suggests that fans in contemporary mediatized environments fight to articulate and undermine those hierarchies through their acts of intervention and protest.

In this sense, cancel culture also becomes a critical practice of what scholars like Jonathan Gray, Melissa Click, and others have described as anti-fandom . 8 Anti-fandom helps reshape received stories and actively responds to the narratives it witnesses. It is how fans express what they think they should no longer have to watch. Anti-fandom led readers to write to Dickens griping about what he did to Little Dorrit or viewers to write to the makers of Dallas for that one infamous cliffhanging whodunit. It includes readers tweeting about transphobic comments in the paper of record. The point isn’t to end the criticized piece of culture. It is to reclaim what the fan wants most from it. “J. K. Rowling gave us Harry Potter; she gave us this world,” said a young adult author who volunteers for the fan site MuggleNet. “But we created the fandom, and we created the magic and community in that fandom. That is ours to keep.” 9 Harry Potter fans seize back from the stories what they want; they don’t need a celebrated charismatic figure to do so. Myths survive longest when their authors become invisible, with the story becoming every speaker’s first-person speech.

The celebrities who survive the rites of criticism that comprise the common understanding of cancelation are those who make it their brand (see, for example, Jeffree Star or Kanye West) or those who accept that celebrity is always a delicate interrelation between fan and star, whom the fan figures as superhuman. Myth doesn’t sustain its storifying power if people stop believing that its powers have serious sway. Celebrities know that to sustain their power they must cede some of what people say they are, including what people accuse them of being, even if mistaken. Accept the terms of your deification. If you can’t stand the heat, you have no right to the power.

Trying to shift the words we use and the resultant stories a society tells will never be nonviolent. Canceling can sometimes reflect the ritual of sacrifice described by René Girard in Violence and the Sacred (1977). 10 A sacrifice is the act of slaughtering an animal or person or surrendering a possession as an offering to a superhuman power. According to Girard, the sacrificed thing—the person, animal, or inanimate possession—is a surrogate victim. The point of the sacrificial killing is to organize a wee bit of violence in a highly localized way to avoid a grander violence. The surrogate victim, the sacrificed thing, becomes known as a scapegoat , a reference to the goat sent into the wilderness in Leviticus after the Jewish chief priest had symbolically laid the sins of the people upon it. Enlightenment philosophers hoped some of this violence could be ended through the formation of a social contract, but Girard believed the problem of violence, which is the primary problem that cancel culture seeks to redress, could only be solved with a lesser dose of violence. We might say that sacrifice becomes a requisite procedure for societies transitioning from one level of inclusion to another.

They are not pushing back because they hate the power that person has but because they are angry about how that teacher, that New Yorker, that famous comedian used their power.

In Girard’s scheme, comedian Dave Chappelle, “canceled” over transphobic comments in his stand-up (and, again, for the way he responded to his cancelation), is the surrogate victim ; transphobia is the sacrificial victim , the latent object of sacrifice. This is the double substitution which Girard wrote about: a singular person is sacrificed on behalf of a larger subject that the society seeks to cancel to slow its furtherance. Dave Chappelle gets yelled at because his mistakes represent a bigger social problem that the community wants to contain, so that the problem does not get bigger.

I observe how intensely intimate this is. The people who sacrifice Chappelle are not newcomers to him—they are people who knew him, even believed in him and liked his edgy voice. He had to be sacrificed, but that was upsetting, disappointing, disheartening.

Canceling isn’t a situation where a random person, animal, or possession is brought into a community and sacrificed. It only carries meaning if it is something held close, something you nicknamed and loved and wanted never not to be there.

so, what is the measure of what we’re describing? Myths make many things happen that money does not measure. The colleague worrying about their editorial; the online commentator pounding out a defense of free speech; the right-wing radio host furious about critical race theory, and the Bernie-bro podcast host smarting about college feminists: none of them are feeling great. What is the measure of this lousy feeling?

Stress, I want to say, the stress it causes. On a beach walk I seek to compel an older colleague to retire after years of critical student feedback about his chauvinist speech and several failed efforts to reeducate the educator. Pressing, I ask: “Wouldn’t it just be more peaceful if you didn’t have to face those criticisms one semester more?” His wife, walking with us, interrupts: Yes, this is going to kill him. He’s going to die from a heart attack .

I am thinking about heart pain when I first read about the history of canceling as a locution in English. It was Black digital practices, specifically the operation of Black Twitter, that converted “cancel you” into a social intervention. 11 Journalist Clyde McGrady traced the origins of cancel used in this way back to Black singer-songwriter Nile Rodgers, who co-wrote the 1981 song “Your Love Is Cancelled” for his funk and disco band Chic. 12 In the song, a guy speaks to his ex-girl. “Just look at what you’ve done,” the speaker sings. “Got me on the run / Took me for a ride, really hurt my pride.” The singer is wounded by how vulnerable they were, angry that their once-upon beloved seduced them, then dropped them.

I am listening to this Chic song and thinking about heart pain not because I am stressed about cancel culture but because I am in a period of heartache. I am in love and in pain about love. Listening to a lot of soul music, crying late at night on the phone, seeing in every astrological report more reasons to weep. The whole history of R&B is a howl from the gurney about the pain of stressed hearts. About the pain of mistake, of wishing you could take it back, of wishing you were otherwise. Someone makes you a star of their life, then they don’t want you to be their fan, or they to be yours, anymore.

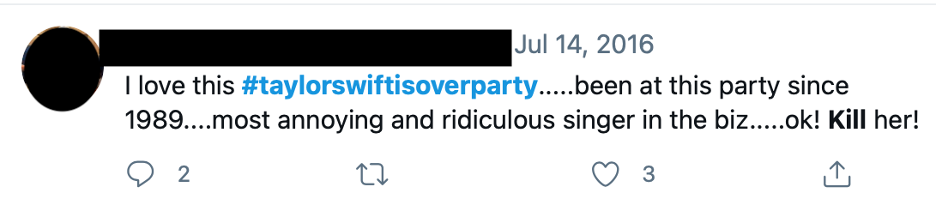

Chic’s “Your Love is Cancelled” preceded a scene in the 1991 film New Jack City in which the girlfriend of a gangster confronts him about his violence. “You’re a murderer, Nino,” she screams. Wesley Snipes, who plays Nino, shoves her onto a desk, douses her with champagne, and snaps to his associate, “Cancel that bitch. I’ll buy another one.” Hip-hop appropriation of that line—like when Lil Wayne rapped, “had to cancel that bitch like Nino,” in “I’m Single” (2010)—solidified the phrase’s public circulation. 13 The perspective reflected in the song and the film is that of a person who is hurt and trying to triumph fiercely over that hurt. The speaker seeks to topple the figure that subjugates them. In both instances, men speak about canceling women who are voiceless. Their act of cancelation is at best unhealthy, a momentary derangement, violent speech meant to hurt by reasserting their power. I loved you, I trusted you, and you betrayed me. Let me slam back in lyric and gesture that I will be just fine. I will be just fine. I will be just fine , without you .

There is a lot to say about what cancel culture is, what unites fans against a comedy set or a novel about a migrant’s experience or a teacher’s in-class utterance. To understand those most upset about cancel culture I must come to understand why people affirm some idea of their freedom over someone else’s idea of safety; why people call out sensitivity in one group while demonstrating through their reaction paper-thin emotional walls. You’re canceled is said between two parties, one of whom says it because they claim devastation at how poorly they’ve been cared for by the other. The other can’t believe it, unable to understand how their lover can speak this way. And suddenly I realize one way to describe cancel culture is as a violent reaction to heartbreak.

When worshipful attentions are withdrawn, the lacerating reverberation of myth’s interruption cannot be underestimated.

The students who cancel the teacher for their anti-Black remark; the New Yorkers who cancel Amy Cooper for soiling their public park; the fans who cancel Chappelle for transphobic remarks: they are not pushing back because they hate the power that person has but because they are angry about how that teacher, that New Yorker, that famous comedian used their power. The people calling for cancelation connect specific word choices to larger systems in which bigotry leads to massive social disparities. Mythologies explain that gods use power clumsily, and religions offer ways to survive while you grapple with the results of their fumble. Worship knits people back into community after drama and dereliction. Cancel culture is another mythic frame for a perennial ritual procedure by which people sift the good and the bad. It is painful because the world in which ritual exists is filled with preventable pain.

The marital liturgy in the 1522 Book of Common Worship includes a phrase, with my body I thee worship . What gets you to the altar where you might say these words? A lot of feeling, a lot of storifying. “Tell me about the day you met,” you might ask at a party. “Tell me how you knew you were in love.” Myths pour out in reply, stories of human action and cosmic fate that account for the mystery of love’s realization. The Book of Common Worship does not make myth visible. It records rituals that a particular religious tradition recommends for people to practice love, not storify it. To worship your body with mine. To attend to each other with care. To see each other as we are and to believe that person is someone worth seeing and seeing and seeing, again.

Myths are real. The anguish at canceling, the worry over being canceled, the sense that cancelation is what kids these days do—none of it makes sense outside the reality of the stories we tell to string ourselves to other people. When worshipful attentions are withdrawn, the lacerating reverberation of myth’s interruption cannot be underestimated. It’s an eruption, a tear at the fabric of what we hold dearest. So, to those who are worried about the stress of cancelation’s effects, I say what my friends say to me on the phone late at night, what they say over and over with the assuredness we have when heartbreak is heard. Try to learn from this. Know you will survive. And believe against all protesting pain, all teeth gnashing, notes left on windshields and marks left on your body, that you will be better for the lesson higher powers decided you needed to receive.

1. Pippa Norris, “Cancel Culture: Myth or Reality?” Political Studies 71, no. 1 (2023): 145–74.

2. Ligaya Mishan, “The Long and Tortured History of Cancel Culture,” New York Times Style Magazine, 3 December 2020.

3. Alan Dershowitz, Cancel Culture: The Latest Attack on Free Speech and Due Process (New York: Hot Books, 2020), 4.

4. Kevin Donnelly, “Cancel Culture and the Left’s Long March,” Spectator (Aus.), 16 March 2021.

5. Emily A. Vogels et al., “Americans and ‘Cancel Culture’: Where Some See Calls for Accountability, Others See Censorship, Punishment,” Pew Research Center, 19 May 2021.

6. Danielle Butler, “The Misplaced Hysteria About a ‘Cancel Culture’ That Doesn’t Actually Exist,” The Root, 23 October 2018.

7. Eve Ng, Cancel Culture: A Critical Analysis (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), 3.

8. Melissa A. Click, ed., Anti-Fandom: Dislike and Hate in the Digital Age (New York: New York University Press, 2019); Jonathan Gray, Dislike-Minded: Media, Audiences, and the Dynamics of Taste (New York: New York University Press, 2021).

9. Julia Jacobs, “Harry Potter Fans Reimagine Their World Without Its Creator,” New York Times, 12 June 2020.

10. René Girard, Violence and the Sacred , translated by Patrick Gregory (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977).

11. On the origin of “cancel” in the Black vernacular tradition, see Meredith D. Clark, “DRAG THEM: A Brief Etymology of So-called ‘Cancel Culture,’” Communication and the Public 5, no. 3–4 (2020): 88–92.

12. Clyde McGrady, “The Strange Journey of ‘Cancel’ from a Black-Culture Punchline to a White-Grievance Watchword,” Washington Post, 2 April 2021.

13. Aja Romano, “The Second Wave of ‘Cancel Culture,’” Vox , 5 May 2021.

Rachel Cusk

Renaissance women, fady joudah, you might also like, a moral education, the journalist and the photographer, nothing is a memory, the yale review festival 2024.

Join us April 16–19 for readings, panels, and workshops with Hernan Diaz, Katie Kitamura, and many others.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69241211/cancel_culture_board_1.0.jpg)

Filed under:

The second wave of “cancel culture”

How the concept has evolved to mean different things to different people.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: The second wave of “cancel culture”

“Cancel culture,” as a concept, feels inescapable. The phrase is all over the news, tossed around in casual social media conversation; it’s been linked to everything from free speech debates to Mr. Potato Head .

It sometimes seems all-encompassing, as if all forms of contemporary discourse must now lead, exhaustingly and endlessly, either to an attempt to “cancel” anyone whose opinions cause controversy or to accusations of cancel culture in action, however unwarranted.

In the rhetorical furor, a new phenomenon has emerged: the weaponization of cancel culture by the right.

Across the US, conservative politicians have launched legislation seeking to do the very thing they seem to be afraid of: Cancel supposedly left-wing businesses, organizations, and institutions; see, for example, national GOP figures threatening to punish Major League Baseball for standing against a Georgia voting restrictions law by removing MLB’s federal antitrust exemption.

Meanwhile, Fox News has stoked outrage and alarmism over cancel culture, including trying to incite Gen X to take action against the nebulous problem. Tucker Carlson, one of the network’s most prominent personalities, has emphatically embraced the anti-cancel culture discourse, claiming liberals are trying to cancel everything from Space Jam to the Fourth of July .

The idea of canceling began as a tool for marginalized communities to assert their values against public figures who retained power and authority even after committing wrongdoing — but in its current form, we see how warped and imbalanced the power dynamics of the conversation really are.

All along, debate about cancel culture has obscured its roots in a quest to attain some form of meaningful accountability for public figures who are typically answerable to no one. But after centuries of ideological debate turning over questions of free speech, censorship, and, in recent decades, “political correctness,” it was perhaps inevitable that the mainstreaming of cancel culture would obscure the original concerns that canceling was meant to address. Now it’s yet another hyperbolic phase of the larger culture war.

The core concern of cancel culture — accountability — remains as crucial a topic as ever. But increasingly, the cancel culture debate has become about how we communicate within a binary, right versus wrong framework. And a central question is not whether we can hold one another accountable, but how we can ever forgive.

Cancel culture has evolved rapidly to mean very different things to different people

It’s only been about six years since the concept of “cancel culture” began trickling into the mainstream. The phrase has long circulated within Black culture, perhaps paying homage to Nile Rodgers’s 1981 single “Your Love Is Cancelled.” As I wrote in my earlier explainer on the origins of cancel culture , the concept of canceling a whole person originated in the 1991 film New Jack City and percolated for years before finally emerging online among Black Twitter in 2014 thanks to an episode of Love and Hip-Hop: New York. Since then, the term has undergone massive shifts in meaning and function.

Early on, it most frequently popped up on social media, as people attempted to collectively “cancel,” or boycott, celebrities they found problematic. As a term with roots in Black culture, it has some resonance with Black empowerment movements, as far back as the civil rights boycotts of the 1950s and ’60s . This original usage also promotes the idea that Black people should be empowered to reject cultural figures or works that spread harmful ideas. As Anne Charity Hudley, the chair of linguistics of African America at the University of California Santa Barbara, told me in 2019 , “When you see people canceling Kanye, canceling other people, it’s a collective way of saying, ‘We elevated your social status, your economic prowess, [and] we’re not going to pay attention to you in the way that we once did. ... ‘I may have no power, but the power I have is to [ignore] you.’”

As the logic behind wanting to “cancel” specific messages and behaviors caught on, many members of the public, as well as the media, conflated it with adjacent trends involving public shaming, callouts, and other forms of public backlash . (The media sometimes refers to all of these ideas collectively as “ outrage culture .”) But while cancel culture overlaps and aligns with many related ideas, it’s also always been inextricably linked to calls for accountability.

As a concept, cancel culture entered the mainstream alongside hashtag-oriented social justice movements like #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo — giant social waves that were effective in shifting longstanding narratives about victims and criminals, and in bringing about actual prosecutions in cases like those of Bill Cosby and Harvey Weinstein . It is also frequently used interchangeably with “woke” political rhetoric , an idea that is itself tied to the 2014 rise of the Black Lives Matter protests. In similar ways, both “wokeness” and “canceling” are tied to collectivized demands for more accountability from social systems that have long failed marginalized people and communities.

But over the past few years, many right-wing conservatives, as well as liberals who object to more strident progressive rhetoric, have developed the view that “cancel culture” is a form of harassment intended to silence anyone who sets a foot out of line under the nebulous tenets of “woke” politics . So the idea now represents a vast assortment of objectives and can hold wildly different connotations, depending on whom you’re talking to.

Taken in good faith, the concept of “canceling” a person is really about questions of accountability — about how to navigate a social and public sphere in which celebrities, politicians, and other public figures who say or do bad things continue to have significant platforms and influence. In fact, actor LeVar Burton recently suggested the entire idea should be recast as “consequence culture.”

“I think it’s misnamed,” Burton told the hosts of The View . “I think we have a consequence culture. And that consequences are finally encompassing everybody in the society, whereas they haven’t been ever in this country.”

. @levarburton : “In terms of cancel culture, I think it’s misnamed. I think we have a consequence culture and consequences are finally encompassing everybody.” #TheView pic.twitter.com/jDQ9HEJyV2 — Justice Dominguez (@justicedeveraux) April 26, 2021

Within the realm of good faith, the larger conversation around these questions can then expand to contain nuanced considerations of what the consequences of public misbehavior should be, how and when to rehabilitate the reputation of someone who’s been “canceled,” and who gets to decide those things.

Taken in bad faith, however, “cancel culture” becomes an omniscient and dangerous specter: a woke, online social justice mob that’s ready to rise up and attack anyone, even other progressives, at the merest sign of dissent. And it’s this — the fear of a nebulous mob of cancel-happy rabble-rousers — that conservatives have used to their political advantage.

Conservatives are using fear of cancel culture as a cudgel

Critics of cancel culture typically portray whoever is doing the canceling as wielding power against innocent victims of their wrath. From 2015 on, a variety of news outlets, whether through opinion articles or general reporting , have often framed cancel culture as “ mob rule .”

In 2019, the New Republic’s Osita Nwanevu observed just how frequently some media outlets have compared cancel culture to violent political uprisings, ranging from ethnocide to torture under dictatorial regimes. Such an exaggerated framework has allowed conservative media to depict cancel culture as an urgent societal issue. Fox News pundits, for example, have made cancel culture a focal part of their coverage . In one recent survey , people who voted Republican were more than twice as likely to know what “cancel culture” was, compared with Democrats and other voters, even though in the current dominant understanding of cancel culture, Democrats are usually the ones doing the canceling.

“The conceit that the conservative right has gotten so many people to adopt , beyond divorcing the phrase from its origins in Black queer communities, is an obfuscation of the power relations of the stakeholders involved,” journalist Shamira Ibrahim told Vox in an email. “It got transformed into a moral panic akin to being able to irrevocably ruin the powerful with just the press of a keystroke, when it in actuality doesn’t wield nearly as much power as implied by the most elite.”

You wouldn’t know that to listen to right-wing lawmakers and media figures who have latched onto an apocalyptic scenario in which the person or subject who’s being criticized is in danger of being censored, left jobless, or somehow erased from history — usually because of a perceived left-wing mob.

This is a fear that the right has weaponized. At the 2020 Republican National Convention , at least 11 GOP speakers — about a third of those who took the stage during the high-profile event — addressed cancel culture as a concerning political phenomenon. President Donald Trump himself declared that “The goal of cancel culture is to make decent Americans live in fear of being fired, expelled, shamed, humiliated and driven from society as we know it.” One delegate resolution at the RNC specifically targeted cancel culture , describing a trend toward “erasing history, encouraging lawlessness, muting citizens, and violating free exchange of ideas, thoughts, and speech.”

Ibrahim pointed out that in addition to re-waging the war on political correctness that dominated the 1990s by repackaging it as a war on cancel culture, right-wing conservatives have also “attempted to launch the same rhetorical battles” across numerous fronts, attempting to rebrand the same calls for accountability and consequences as “woke brigade, digital lynch mobs, outrage culture and call-out culture.” Indeed, it’s because of the collective organizational power that online spaces provide to marginalized communities, she argued, that anti-cancel culture rhetoric focuses on demonizing them.

Social media is “one of the few spaces that exists for collective feedback and where organizing movements that threaten [conservatives’] social standing have begun,” Ibrahim said, “thus compelling them to invert it into a philosophical argument that doesn’t affect just them, but potentially has destructive effects on censorship for even the working-class individual.”

This potential has nearly become reality through recent forms of Republican-driven legislation around the country. The first wave involved overt censorship , with lawmakers pushing to ban texts like the New York Times’s 1619 Project from educational usage at publicly funded schools and universities. Such censorship could seriously curtail free speech at these institutions — an ironic example of the broader kind of censorship that is seemingly a core fear about cancel culture.

A recent wave of legislation has been directed at corporations as a form of punishment for crossing Republicans. After both Delta Air Lines and Major League Baseball spoke out against Georgia lawmakers’ passage of a restrictive voting rights bill , Republican lawmakers tried to target the companies, tying their public statements to cancel culture. State lawmakers tried and failed to pass a bill stripping Delta of a tax exemption . And some national GOP figures have threatened to punish MLB by removing its exemption from federal antitrust laws. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said that “corporations will invite serious consequences if they become a vehicle for far-left mobs.”

But for all the hysteria and the actual crackdown attempts lawmakers have enacted, even conservatives know that most of the hand-wringing over cancellation is performative. CNN’s AJ Willingham pointed out how easily anti-cancel culture zeal can break down, noting that although the 2021 Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) was called “America Uncanceled,” the organization wound up removing a scheduled speaker who had expressed anti-Semitic viewpoints. And Fox News fired a writer last year after he was found to have a history of making racist, homophobic, and sexist comments online.

These moves suggest that though they may decry “woke” hysteria, conservatives also sometimes want consequences for extremism and other harmful behavior — at least when the shaming might fall on them as well.

“This dissonance reveals cancel culture for what it is,” Willingham wrote. “Accountability for one’s actions.”

CPAC’s swift levying of consequences in the case of a potentially anti-Semitic speaker is revealing on a number of levels, not only because it gives away the lie beneath concerns that “cancel culture” is something profoundly new and dangerous, but also because the conference actually had the power to take action and hold the speaker accountable. Typically, the apocryphal “social justice mob” has no such ability. Actually canceling a whole person is much harder to do than opponents of cancel culture might make it sound — nearly impossible, in fact.

Very few “canceled” public figures suffer significant career setbacks

It’s true that some celebrities have effectively been canceled, in the sense that their actions have resulted in major consequences, including job losses and major reputational declines, if not a complete end to their careers.

Consider Harvey Weinstein , Bill Cosby , R. Kelly , and Kevin Spacey , who faced allegations of rape and sexual assault that became impossible to ignore, and who were charged with crimes for their offenses. They have all effectively been “canceled” — Weinstein and Cosby because they’re now convicted criminals, Kelly because he’s in prison awaiting trial , and Spacey because while all charges against him to date have been dropped, he’s too tainted to hire.

Along with Roseanne Barr, who lost her hit TV show after a racist tweet , and Louis C.K., who saw major professional setbacks after he admitted to years of sexual misconduct against female colleagues, their offenses were serious enough to irreparably damage their careers, alongside a push to lessen their cultural influence.

But usually, to effectively cancel a public figure is much more difficult. In typical cases where “cancel culture” is applied to a famous person who does something that incurs criticism, that person rarely faces serious long-term consequences. During the past year alone, a number of individuals and institutions have faced public backlash for troubling behavior or statements — and a number of them thus far have either weathered the storm or else departed their jobs or restructured their operations of their own volition.

For example, beloved talk show host Ellen DeGeneres has come under fire in recent years for a number of reasons, from palling around with George W. Bush to accusing the actress Dakota Johnson of not inviting her to a party to, most seriously, allegedly fostering an abusive and toxic workplace . The toxic workplace allegations had an undeniable impact on DeGeneres’s ratings, with The Ellen DeGeneres Show losing over 40 percent of its viewership in the 2020–’21 TV season. But DeGeneres has not literally been canceled; her daytime talk show has been confirmed for a 19th season, and she continues to host other TV series like HBO Max’s Ellen’s Next Great Designer .

Another TV host recently felt similar heat but has so far retained his job: In February, The Bachelor franchise underwent a reckoning due to a long history of racial insensitivity and lack of diversity, culminating in the announcement that longtime host Chris Harrison would be “ stepping aside for a period of time.” But while Harrison won’t be hosting the upcoming season of The Bachelorette , ABC still lists him as the franchise host, and some franchise alums have come forward to defend him . (It is unclear whether Harrison will return as a host in the future, though he has said he plans to do so and has been working with race educators and engaging in a personal accountability program of “counsel, not cancel.”)

In many cases, instead of costing someone their career, the allegation of having been “canceled” instead bolsters sympathy for the offender, summoning a host of support from both right-wing media and the public. In March 2021, concerns that Dr. Seuss was being “canceled” over a decision by the late author’s publisher to stop printing a small selection of works containing racist imagery led to a run on Seuss’s books that landed him on bestseller lists. And although J.K. Rowling sparked massive outrage and calls to boycott all things Harry Potter after she aired transphobic views in a 2020 manifesto, sales of the Harry Potter books increased tremendously in her home country of Great Britain.

A few months later, 58 British public figures including playwright Tom Stoppard signed an open letter supporting Rowling’s views and calling her the target of “an insidious, authoritarian and misogynistic trend in social media.” And in December, the New York Times not only reviewed the author’s latest title — a new children’s book called The Ickabog — but praised the story’s “moral rectitude,” with critic Sarah Lyall summing up, “It made me weep with joy.” It was an instant bestseller .

In light of these contradictions, it’s tempting to declare that the idea of “canceling” someone has already lost whatever meaning it once had. But for many detractors, the “real” impact of cancel culture isn’t about famous people anyway.

Rather, they worry, “cancel culture” and the polarizing rhetoric it enables really impacts the non-famous members of society who suffer its ostensible effects — and that, even more broadly, it may be threatening our ability to relate to each other at all.

The debate around cancel culture began as a search for accountability. It may ultimately be about encouraging empathy.

It’s not only right-wing conservatives who are wary of cancel culture. In 2019, former President Barack Obama decried cancel culture and “woke” politics, framing the phenomenon as people “be[ing] as judgmental as possible about other people” and adding, “That’s not activism.”

At a recent panel devoted to making a nonpartisan “ Case Against Cancel Culture ,” former ACLU president Nadine Strossen expressed great concern over cancel culture’s chilling effect on the non-famous. “I constantly encounter students who are so fearful of being subjected to the Twitter mob that they are engaging in self-censorship,” she said. Strossen cited as one such chilling effect the isolated instances of students whose college admissions had been rescinded on the basis of racist social media posts.

In his recent book Cancel This Book: The Progressive Case Against Cancel Culture , human rights lawyer and free speech advocate Dan Kovalik argues that cancel culture is basically a giant self-own, a product of progressive semantics that causes the left to cannibalize itself.

“Unfortunately, too many on the left, wielding the cudgel of ‘cancel culture,’ have decided that certain forms of censorship and speech and idea suppression are positive things that will advance social justice,” Kovalik writes . “I fear that those who take this view are in for a rude awakening.”

Kovalik’s worries are partly grounded in a desire to preserve free speech and condemn censorship. But they’re also grounded in empathy. As America’s ideological divide widens, our patience with opposing viewpoints seems to be waning in favor of a type of society-wide “cancel and move on” approach, even though studies suggest that approach does nothing to change hearts and minds. Kovalik points to a survey published in 2020 that found that in 700 interactions, “deep listening” — including “respectful, non-judgmental conversations” — was 102 times more effective than brief interactions in a canvassing campaign for then-presidential candidate Joe Biden.

Across the political spectrum, wariness toward the idea of “cancel culture” has increased — but outside of right-wing political spheres, that wariness isn’t so centered on the hyper-specific threat of losing one’s job or career due to public backlash. Rather, the term “cancel culture” functions as shorthand for an entire mode of polarized, aggressive social engagement.

Journalist (and Vox contributor) Zeeshan Aleem has argued that contemporary social media engenders a mode of communication he calls “disinterpretation,” in which many participants are motivated to join the conversation not because they want to promote communication, or even to engage with the original opinion, but because they seek to intentionally distort the discourse.

In this type of interaction, as Aleem observed in a recent Substack post, “Commentators are constantly being characterized as believing things they don’t believe, and entire intellectual positions are stigmatized based on vague associations with ideas that they don’t have any substantive affiliation with.” The goal of such willful misinterpretation, he argued, is conformity — to be seen as aligned with the “correct” ideological standpoint in a world where stepping out of alignment results in swift backlash, ridicule, and cancellation.

Such an antagonistic approach “effectively treats public debate as a battlefield,” he wrote. He continued:

It’s illustrative of a climate in which nothing is untouched by polarization, in which everything is a proxy for some broader orientation which must be sorted into the bin of good/bad, socially aware/problematic, savvy/out of touch, my team/the enemy. ... We’re tilting toward a universe in which all discourse is subordinate to activism; everything is a narrative, and if you don’t stay on message then you’re contributing to the other team on any given issue. What this does is eliminate the possibility of public ambiguity, ambivalence, idiosyncrasy, self-interrogation.

The problem with this style of communication is that in a world where every argument gets flattened into a binary under which every opinion and every person who publicly shares their thoughts must be either praised or canceled, few people are morally righteous enough to challenge that binary without their own motives and biases then being called into question. The question becomes, as Aleem reframed it for me: “How does someone avoid the reality that their claims of being disinterpreted will be disinterpreted?”

“When people demand good-faith engagement, it can often be dismissed as a distraction tactic or whining about being called out,” he explained, noting that some responses to his original Twitter thread on the subject assumed he must be complaining about just such a callout.

Other complications can arise, such as when the people who are protesting against this type of bad-faith discourse are also criticized for problematic statements or behavior , or perceived as having too much privilege to wholly understand the situation. Remember, the origins of cancel culture are rooted in giving marginalized members of society the ability to seek accountability and change, especially from people who hold a disproportionate amount of wealth, power, and privilege.

“[W]hat people do when they invoke dog whistles like ‘cancel culture’ and ‘culture wars,’” Danielle Butler wrote for the Root in 2018, “is illustrate their discomfort with the kinds of people who now have a voice and their audacity to direct it towards figures with more visibility and power.”

But far too often, people who call for accountability on social media seem to slide quickly into wanting to administer punishment instead. In some cases, this process really does play out with a mob mentality, one that seems bent on inflicting pain and hurt while allowing no room for growth and change, showing no mercy, and offering no real forgiveness — let alone allowing for the possibility that the mob itself might be entirely unjustified.

See, for example, trans writer Isabel Fall, who wrote a short story in 2020 that angered many readers with its depiction of gender dysphoria through the lens of militaristic warfare. (The story has since become a finalist for a Hugo Award.) Because Fall published under a pseudonym, people who disliked the story assumed she must be transphobic rather than a trans woman wrestling with her own dysphoria. Fall was harassed, doxed, forcibly outed, and driven offline . These types of “cancellations” can happen without consideration for the person being canceled, even when that person apologizes — or, as in Fall’s case, even when they had little if anything to be sorry about.

The conflation of antagonized social media debates with the more serious aims to make powerful people face consequences is part of the problem. “I think the messy and turbulent evolution of speech norms online influences people’s perception of what’s called cancel culture,” Aleem said. He added that he’s grown “resistant to using the term [cancel culture] because it’s become so hard to pin down.”

“People connect boycotts with de-platforming speakers on college campuses,” he observed, “with social media harassment, with people being fired abruptly for breaching a taboo in a viral video.” The result is an environment where social media is a double-edged sword: “One could argue,” Aleem said, “that there’s now public input on issues [that wasn’t available] before, and that’s good for civil society, but that the vehicle through which that input comes produces some civically unhealthy ways of expression.”

Prevailing confusion about cancel culture hasn’t stopped it from becoming culturally and politically entrenched

If the conversation around cancel culture is unhealthy, then one can argue that the social systems cancel culture is trying to target are even more unhealthy — and that, for many people, is the bottom line.

The concept of canceling someone was created by communities of people who’ve never had much power to begin with. When people in those communities attempt to demand accountability by canceling someone, the odds are still stacked against them. They’re still the ones without the social, political, or professional power to compel someone into meaningful atonement, but they can at least be vocal by calling for a collective boycott.

The push by right-wing lawmakers and pundits to use the concept as a tool to vilify the left, liberals, and the powerless upends the original logic of cancel culture, Ibrahim told me. “It is being used to obscure marginalized voices by inverting the victim and the offender, and disingenuously affording disproportionate impact to the reach of a single voice — which has historically long been silenced — to now being the silencer of cis, male, and wealthy individuals,” she said.

And that approach is both expanding and growing more visible. What’s more, it is a divide not just between ideologies, but also between tactical approaches in navigating those ideological differences and dealing with wrongdoing.

“It effectuates a slippery-slope argument by taking a rhetorical scenario and pushing it to really absurdist levels, and furthermore asking people to suspend their implicit understanding of social constructs of power and class,” Ibrahim said. “It mutates into, ‘If I get canceled, then anyone can get canceled.’” She pointed out that usually, the supposedly “canceled” individual suffers no real long-term harm — “particularly when you give additional time for a person to regroup from a scandal. The media cycle iterates quicker than ever in present day.”

She suggested that perhaps the best approach to combating the escalation of cancel culture hysteria into a political weapon is to refuse to let those with power shape the way the conversation plays out.

“I think our remit, if anything, is to challenge that reframing and ask people to define the stakes of what material quality of life and liberty was actually lost,” she said.

In other words, the way cancel culture is discussed in the media might make it seem like something to fear and avoid at all costs, an apocalyptic event that will destroy countless lives and livelihoods, but in most cases, it’s probably not. That’s not to suggest that no one will ever be held accountable, or that powerful people won’t continue to be asked to answer for their transgressions. But the greater worry is still that people with too much power might use it for bad ends.

At its best, cancel culture has been about rectifying power imbalances and redistributing power to those who have little of it. Instead, it now seems that the concept may have become a weapon for people in power to use against those it was intended to help.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Americans are hooked on the fantasy of financial liberation

The western visuals of beyoncé’s cowboy carter, decoded, the talented mr. ripley is a perfect striver gothic. the netflix adaptation is lifeless., sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Justifying Cancel Culture

Jeremy Stangroom casts a critical eye over some of the justifications offered for cancel culture.

Let’s, for the sake of argument, take “cancellation” to involve the attempt to deprive a person of the ability to make a political and cultural difference through their words and actions. This might be achieved variously by pressurising a university to withdraw an invitation to give a talk at a prestigious event (no-platforming); or persuading a publisher to cancel a book contract; or lobbying a social media company to terminate an account; or getting a potential employer to withdraw a job offer; or persuading a current employer to terminate a position of employment. The idea of cancellation is to neuter the target, to strip them of their ability to bring about certain kinds of perlocutionary effect – informing, influencing, persuading, inciting, and so on. If cancellation also functions as punishment, then so much the better. Not all cancellations are successful, of course, and some go spectacularly wrong, but for our purposes, it is the attempt that counts.

In these terms, cancellation sounds like a bad thing. It conjures up images of demented Twitter mobs, getting off on the frisson of collective outrage directed towards a “moral” end, seeking to destroy somebody’s career because of an intemperate remark they made when they were a teenager. But, in fact, the issue is more complex than this admittedly sometimes-accurate caricature.

The complexity lies in the fact that it is easy to identify occasions where it seems, certainly at first sight, that a limited form of cancellation would be a good option. For example, in our present circumstances, it is reasonable to think that universities should not offer a platform to a conspiracy theorist who wants to disseminate a message of COVID denial, and that were such a platform offered, people would be right to protest it.

Here the harm of allowing a COVID-denialist to speak at an institution of learning is clear and obvious. As well as providing a platform for the dissemination of misinformation, which might result directly in harm (if, for example, somebody in the audience cancels a vaccination appointment because of what they’ve heard), there is also a reputational boost for the speaker and the views they espouse. They gain because of the association with an institution of repute.

This point can be dressed up in some fancy philosophical clothes. The philosopher, Neil Levy, for example, talks about no-platforming in the context of “higher-order evidence” – evidence that doesn’t bear directly on the issue under consideration, but rather functions at one step removed. It’s evidence about evidence, how the evidence was generated, for example, whether it enjoys widespread support amongst a community of scholars, whether it has stood the test of time, whether it has been rigorously tested, and so on.

The provision of a platform by a prestigious institution of learning is a kind of higher-order evidence. It tells us, or apparently tells us, that we’re dealing with a respectable, academically legitimate, speaker, whose ideas are worthy of consideration. Obviously, universities, and other prestigious institutions, should not be in the business of generating false evidence, so if a speaker is known to espouse views that are obviously wrong, they should not be granted a platform. Stripped of its fancy philosophical clothes, this is an obvious point, and it’s long been understood.

An example from the world of academic philosophy will make the general point clear. The example takes us back to 1985, and the publication of Roger Scruton’s book, Thinkers of the New Left . Scruton tells the story of an exemplary cancellation.

My… book was published… at a time when I was still teaching in a university, and known among British left-wing intellectuals as a prominent opponent of their cause, which was the cause of decent people everywhere. The book was therefore greeted with derision and outrage, reviewers falling over each other for the chance to spit on the corpse. Its publication was the beginning of the end for my university career, the reviewers raising serious doubts about my intellectual competence as well as my moral character.

The book was published by Longman, a reputable academic publisher, which did not go down well with one unnamed Oxford philosopher.

One academic philosopher wrote to… the original publisher, saying, ‘I may tell you with dismay that many colleagues here [i.e., in Oxford] feel that the Longman imprint – a respected one – has been tarnished by association with Scruton’s work.’

The unnamed philosopher concluded his missive by expressing the hope that “the negative reactions generated by this particular publishing venture may make Longman think more carefully about its policy in the future.”

Scruton goes on to note that one of Longman’s best-selling educational authors threatened to move to a different publisher if Scruton’s book stayed in print, and, lo and behold, the remaining copies of Thinkers of the New Left quickly disappeared from bookshops (notwithstanding the dangers of a post hoc fallacy here).

The point is that it was not the publication of Scruton’s book per se that was unacceptable (though, obviously, its critics would have preferred for it not to have been published at all), it was the fact it was published by a respectable imprint, the sort of imprint favoured by legitimate – i.e., not conservative – academics. The respectability of the imprint provided higher-order evidence that Scruton’s take on the character of left-wing politics and thought was worthy of serious consideration, and this could not be allowed to stand.

The Scruton example points to a large tension in the view that concerns about higher-order evidence can justify certain kinds of cancellation. How is it possible to determine which ideas and viewpoints are acceptable and which are not? Who exactly gets to decide?

The philosophers Robert Mark Simpson and Amia Srinivasan answer these questions in terms of a framework that focuses on the norms and practices of the Academy, and the role that “recognised disciplinary experts” play in ensuring that intellectual rigour and disciplinary standards are upheld. Thus:

It is permissible for disciplinary gatekeepers to exclude cranks and shills from valuable communicative platforms in academic contexts, because effective training and research requires that communicative privileges be given to some and not others, based on people’s disciplinary competence.

Simpson and Srinivasan argue that the processes that amplify the speech of experts and marginalise the speech of non-experts are ubiquitous and routine within the Academy.

The professoriate decides which candidates have earned doctoral credentials. Editors of journals and academic presses exercise discretionary judgment to decide whose work will be published. The curriculum is set by faculty… and students work within it.

Therefore, there is nothing contrary to the ethos of academic freedom, or to a liberal politics that takes free speech seriously while recognising that universities are not just an extension of the public square, in depriving a person of a platform to express their views because of a negative appraisal of their credibility and content of their ideas.

There are things to be said in favour of this view, not least it allows us to dispose of now apparently easy cases such as our COVID-denier from earlier. But let’s examine the argument more closely through the lens of an example from 30 years ago.

In May 1992, several top philosophers, including W.V. Quine and David Armstrong, wrote an open letter to The Times newspaper protesting a proposal from Cambridge University to award doyen of French philosophy, Jacques Derrida, an honorary degree. Here are some choice excerpts from the letter:

In the eyes of philosophers, and certainly among those working in leading departments of philosophy throughout the world, M. Derrida’s work does not meet accepted standards of clarity and rigour.

Many French philosophers see in M. Derrida only cause for silent embarrassment, his antics having contributed significantly to the widespread impression that contemporary French philosophy is little more than an object of ridicule.

Academic status based on what seems to us to be little more than semi-intelligible attacks upon the values of reason, truth, and scholarship is not, we submit, sufficient grounds for the awarding of an honorary degree in a distinguished university.

The signatories of this letter were not exactly seeking to no platform Derrida, but it’s same basic phenomenon. The claim was that Derrida’s work is not of sufficient quality to warrant an honorary degree, and the letter implied that a distinguished university, and by extension the discipline of philosophy, would suffer reputational damage were the degree to be awarded.

So how should we view this attempted “cancelling” of Derrida, analysed in the light of Simpson and Srinivasan’s approach?

It seems, at the very least, that the cancelling is defensible from what is in their terms a “liberal” standpoint. If the letter writers were correct in their suggestion that among philosophers in the Anglophone tradition, overwhelmingly the dominant tradition in British and American universities at this time, Derrida’s work was not considered to meet acceptable standards of clarity and rigour, and that even among French philosophers, he was considered something of an embarrassment, then the disciplinary gatekeepers of philosophy had spoken, and Derrida should not have been awarded his degree (and also presumably should not have been invited to give prestigious lectures, and so on). Simpson and Srinivasan explicitly state that flouting epistemic and methodological norms of enquiry justifies the act of no-platforming, and it was precisely the claim of the letter writers that Derrida’s work flouts the established disciplinary norms of philosophy.

Obviously, there is some wriggle room here, not a lot, but a bit. Maybe Simpson and Srinivasan can just bite the bullet, and say that Derrida should not have been awarded his degree, and that it would have been defensible, perhaps even desirable, not to have invited him to give further talks and speeches. Maybe they can deny the claim of the letter writers that there was a groundswell of opinion among philosophers in leading universities that Derrida’s work was not up to standard. Maybe they can claim that the Derrida case is one of their hard cases because there was deep intradisciplinary and/or interdisciplinary disagreement about the status of Derrida’s work, and about whether he possessed the requisite disciplinary competence to be awarded an honorary degree.

So then, let’s bring the tensions in Simpson and Srinivasan’s account into sharper focus by considering a hypothetical case. It’s mid-1984, and Gustavo Gutiérrez, one of the founders of Latin American liberation theology, has a longstanding invitation to give a commencement speech at a prestigious Catholic university in North America. However, because of the recent publication of Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger’s document, “Instruction on Certain Aspects of ‘Liberation Theology’”, which levels the accusation that most forms of liberation theology reduce Christianity to Marxism, a groundswell of opinion has developed in opposition to the speech going ahead.

The almost unanimous opinion of faculty experts and the student body is that Gutiérrez’s status as a reputable theologian is now in serious question. The invitation was always controversial, but Ratzinger’s report has confirmed the suspicions of even the more liberal members of faculty that Gutiérrez’s Marxism is incompatible with a proper understanding of the gospel. Therefore, the decision is made to withdraw the invitation, and to find an alternative speaker to give the speech.

What are we to make of this scenario? The first thing to point out is that while the scenario is hypothetical, the background to it is real. Liberation theology was highly controversial in North America in the 1980s, and, unsurprisingly, conservative, and other, theologians were deeply suspicious of its socialist aspects. A Vatican report from this era explicitly stated that Marxism was incompatible with Catholicism, and in the late summer of 1988, full-page adverts appeared in the Wall Street Journal and New York Times , which railed against the impact of liberation theology in fermenting a revolutionary consciousness in Latin America.

On the face of it, then, our scenario is not wildly implausible. So how should we view it if we take Simpson and Srinivasan’s account seriously? The answer is that there are no obvious grounds for objecting to the withdrawal of the invitation. There is a strong consensus among faculty and the student body that Gutiérrez’s embrace of Marxism severely undermines his credibility as a competent theologian. None of the university’s disciplinary experts will be inhibited in their teaching or research because of a decision to deny Gutiérrez a platform. Therefore, such a decision is entirely compatible with a respect for the autonomy of faculty professionals. Moreover, to the extent that cancelling the invitation functions to uphold the disciplinary authority of the university’s relevant experts, then (arguably) the decision should be supported not merely permitted.

This is surely an uncomfortable result for a defence of the practice of no-platforming that rests on liberal principles. Of course, in the present day, the right tends to call for fewer restrictions on speech, so it might seem like there is little potential in the real world for this sort of outcome, especially if one considers that the Academy skews left politically. Put simply, it’s hard to imagine that a decision to no platform motivated by right-wing concerns (e.g., the recent decision by Samford University to cancel Jon Meacham’s invitation to speak at its president inauguration because of his attendance at a Planned Parenthood event) could ever secure the required level of support among disciplinary gatekeepers to make it legitimate in Simpson and Srinivasan’s terms (though the Derrida example might come close - assuming one considers it to have been motivated by right-wing concerns). But nevertheless, dangers lurk for an approach that gives all the power to disciplinary gatekeepers. This can be nicely illustrated by considering one of Simpson and Srinivasan’s own examples.

There have been repeated calls to no platform Germaine Greer, the renowned feminist author, for her views on trans women. A lecture by Greer held in 2015 came under intense pressure, and though it went ahead in the end, it did so under high security. Simpson and Srinivasan recognise that there are deep divisions within feminist theory over questions of sex and gender identity, and that consequently there simply isn’t enough agreement to make it possible to characterise Greer’s no-platforming as a case of somebody being excluded for lacking disciplinary competence. So far, so good. But they go on, rather wistfully it seems, to suggest that this might not always be the case.

At some point it may cease to be a matter of controversy – among experts with broadly comparable credentials in relevant disciplines – whether Greer’s view represents some kind of failure of disciplinary competence. If ascendant trends in feminist theory continue, it is possible that Greer’s trans-exclusionary ( sic ) views might one day be rejected by all credentialed experts in the relevant humanities or social science disciplines.

Yes, that’s certainly possible. It is also possible that the debate might resolve in the opposite direction, that “ascendant trends” might reverse, and the gender critical view might become the orthodox view. What then? If Simpson and Srinivasan are brave enough to follow the logic of their own argument, they must accept it might become permissible to no platform a speaker for espousing the view that trans women are women, which is not a comfortable position for a liberal to occupy.

In fact, there is something deeply suspect about the idea that “disciplinary experts” should hold sway over these sorts of issues. It seems to be rooted in an implicit whig historiography, allied to the notion that scholars in the humanities and social sciences function in something approaching an ideal speech situation, forming a community of impartial experts proceeding by reason alone, making arguments and weighing up evidence in the pursuit of shared epistemic goals.

Well, the Academy is not like that, not in the least bit like that (though it is very tempting for academics to believe that it is). It is necessary to paint in broad brush strokes here, exaggerating a little, to make the point clear. I’ll speak to sociology, and its related disciplines, because that is what I know.

Sociology as a discipline is political all the way down. The explanatory frameworks within which it operates – and there are more than one, because sociology remains in a pre-paradigmatic state (to borrow some language from Thomas Kuhn) – are political even when they are not ostensibly political (because each rests upon a particular conception of how society functions at its base). If you spend your time doing empirical work, you might not notice this politicisation, but the moment you move into the domain of sociological theory, or political sociology, you’re operating on the terrain of the political.

Sociologists as a group are overwhelmingly on the political left (in fact, multiple studies confirm that the social sciences, generally, skew heavily to the left). Partly this is because young radicals and activists are attracted to disciplines such as sociology, but it is also because there is (now) a self-selecting dynamic in play – put simply, conservative students might end up taking one course in sociology, but probably they’re not going to take two. Matthew Woessner, a conservative Professor of Public Policy, relates a story that is instructive in this regard:

I recall that as a naive sophomore I enrolled in an introductory sociology course and was surprised that the professor was an avowed Marxist. Concerned that our ideological perspectives might ultimately affect my course grade, I tried unsuccessfully to lay low. However, noting that I cringed as she denounced Reagan’s economic policies, the professor asked if I had a different take on the issue. Somewhat reluctantly, I offered a defence of Reaganomics. To her credit, she listened attentively and, as far as I could tell, took my novel ideas seriously. In light of the fact that, by her own admission, she had never heard a spirited defence of conservative economic policies, it became clear to me that sociology was an ideological minefield.

The consequence of all this is that sociologists, and academics working in related disciplines, tend to operate in extremely insular and self-reflexive academic environments, characterised by the almost complete absence of conservative voices. In this context, epistemic goals are secondary to political goals. To (incorrectly) paraphrase Marx, the point isn’t to understand the world, the point is to change it.

As I noted above, this is something of an exaggeration, but not as much as you’d probably imagine. Consider, for example, that the Department of Gender Studies at the London School of Economics (I take gender studies to be a discipline related to sociology) tells us studying gender “opens up space for thinking about other forms of oppression, discrimination and inequality”, and notes that the department is “strongly committed to the principle that gender theory is the foundation of policy, practice and activism: Theory saves lives.” Similarly, the Sociology Department at Essex University identifies the “big questions” as “Why are societies unequal?”, “What is equality?”, “What does it mean to hold power over others?”, “Why are some societies violent?”, and declares that studying sociology at Essex will “help you develop a sociological imagination to take out into the world and change it for the better.” Lastly, if you check out the web page for SOAS’s Centre for Gender Studies, you’ll learn that the Centre is “a hub of research and training working to support anti-racist feminisms and social movements challenging normative constructions of gender and sexuality.”

If you’re interested a more rigorous take on similar themes as it applies in an American context, Christian Smith’s The Sacred Project of American Sociology (OUP, 2014) is well worth a look. He argues that sociology today is “animated by sacred impulses, driven by sacred commitments, and serves a sacred project.” Sociology concerns itself with:

…exposing, protesting, and ending through social movements, state regulations, and government programs all human inequality, oppression, exploitation, suffering, injustice, poverty, discrimination, exclusion, hierarchy, constraint and domination by, of, and over other humans (and perhaps animals and the environment).

The point of all this is that “disciplinary experts” in sociology, and related disciplines, are not objective, unbiased producers of knowledge, who view the world from nowhere, and share common epistemic goals, but rather they are (often) highly politicised, activist professors and researchers who create “knowledge” through the filter of their ideological and moral commitments. The consequence is that there are few good epistemic reasons to think their judgements about the contentious issues that often surround cases of no-platforming should hold sway. For example, it might well be the case that among relevant disciplinary experts a consensus has emerged that “racism” must be defined as involving prejudice plus systemic power. But this would not establish the “disciplinary incompetence” of a social psychologist, for example, who dissented from this definition, and therefore it could not provide legitimate grounds for a no-platforming.

To date, it’s proven quite difficult to pin down precisely which ideas and viewpoints are legitimately subject to “cancellation”, and who exactly would be involved in such a determination. Perhaps, then, a more fruitful way forward can be found by exploring whether some general criterion of harm can be identified that would justify shutting down certain kinds of speech and ideas.

The first point to make is that the law, in the UK at least, affords certain protections in this regard. For example, The Racial and Religious Hatred Act (2006) makes it illegal to stir up racial or religious hatred, with a person guilty of an offence if they use threatening, abusive or insulting words with that intent; and The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act (1994) outlaws the public use of threatening, abusive or insulting words or behaviour if the intent is to cause a person harassment, alarm or distress.