Biography of Charles Dickens, English Novelist

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/McNamara-headshot-history1800s-5b7422c046e0fb00504dcf97.jpg)

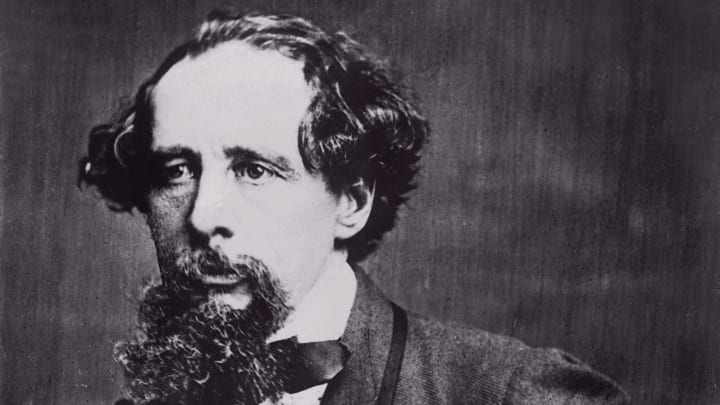

Charles Dickens (February 7, 1812–June 9, 1870) was a popular English novelist of the Victorian era, and to this day he remains a giant in British literature. Dickens wrote numerous books that are now considered classics, including "David Copperfield," "Oliver Twist," "A Tale of Two Cities," and "Great Expectations." Much of his work was inspired by the difficulties he faced in childhood as well as social and economic problems in Victorian Britain.

Fast Facts: Charles Dickens

- Known For : Dickens was the popular author of "Oliver Twist," "A Christmas Carol," and other classics.

- Born : February 7, 1812 in Portsea, England

- Parents : Elizabeth and John Dickens

- Died : June 9, 1870 in Higham, England

- Published Works : Oliver Twist (1839), A Christmas Carol (1843), David Copperfield (1850), Hard Times (1854), Great Expectations (1861)

- Spouse : Catherine Hogarth (m. 1836–1870)

- Children : 10

Charles Dickens was born on February 7, 1812, in Portsea, England. His father had a job working as a pay clerk for the British Navy, and the Dickens family, by the standards of the day, should have enjoyed a comfortable life. But his father's spending habits got them into constant financial difficulties. When Charles was 12, his father was sent to debtors' prison, and Charles was forced to take a job in a factory that made shoe polish known as blacking.

Life in the blacking factory for the bright 12-year-old was an ordeal. He felt humiliated and ashamed, and the year or so he spent sticking labels on jars would be a profound influence on his life. When his father managed to get out of debtors' prison, Charles was able to resume his sporadic schooling. However, he was forced to take a job as an office boy at the age of 15.

By his late teens, he had learned stenography and landed a job as a reporter in the London courts. By the early 1830s , he was reporting for two London newspapers.

Early Career

Dickens aspired to break away from newspapers and become an independent writer, and he began writing sketches of life in London. In 1833 he began submitting them to a magazine, The Monthly . He would later recall how he submitted his first manuscript, which he said was "dropped stealthily one evening at twilight, with fear and trembling, into a dark letter box, in a dark office, up a dark court in Fleet Street."

When the sketch he'd written, titled "A Dinner at Poplar Walk," appeared in print, Dickens was overjoyed. The sketch appeared with no byline, but soon he began publishing items under the pen name "Boz."

The witty and insightful articles Dickens wrote became popular, and he was eventually given the chance to collect them in a book. "Sketches by Boz" first appeared in early 1836, when Dickens had just turned 24. Buoyed by the success of his first book, he married Catherine Hogarth, the daughter of a newspaper editor. He settled into a new life as a family man and an author.

Rise to Fame

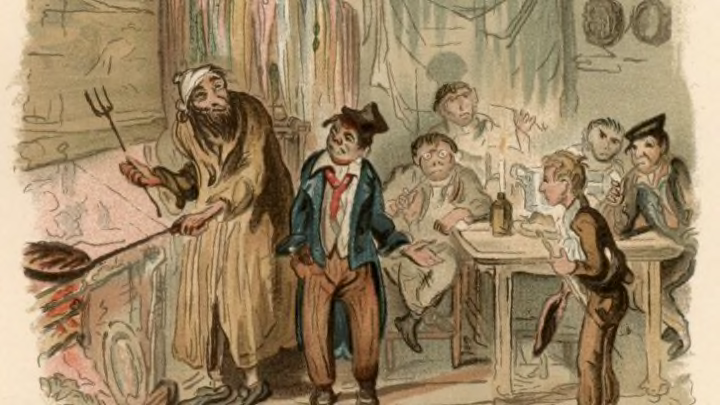

"Sketches by Boz" was so popular that the publisher commissioned a sequel, which appeared in 1837. Dickens was also approached to write the text to accompany a set of illustrations, and that project turned into his first novel, "The Pickwick Papers," which was published in installments from 1836 to 1837. This book was followed by "Oliver Twist," which appeared in 1839.

Dickens became amazingly productive. "Nicholas Nickleby" was written in 1839, and "The Old Curiosity Shop" in 1841. In addition to these novels, Dickens was turning out a steady stream of articles for magazines. His work was incredibly popular. Dickens was able to create remarkable characters, and his writing often combined comic touches with tragic elements. His empathy for working people and for those caught in unfortunate circumstances made readers feel a bond with him.

As his novels appeared in serial form, the reading public was often gripped with anticipation. The popularity of Dickens spread to America, and there were stories told about how Americans would greet British ships at the docks in New York to find out what had happened next in Dickens' latest novel.

Visit to America

Capitalizing on his international fame, Dickens visited the United States in 1842 when he was 30 years old. The American public was eager to greet him, and he was treated to banquets and celebrations during his travels.

In New England, Dickens visited the factories of Lowell, Massachusetts, and in New York City he was taken to the see the Five Points , the notorious and dangerous slum on the Lower East Side. There was talk of him visiting the South, but as he was horrified by the idea of enslavement he never went south of Virginia.

Upon returning to England, Dickens wrote an account of his American travels which offended many Americans.

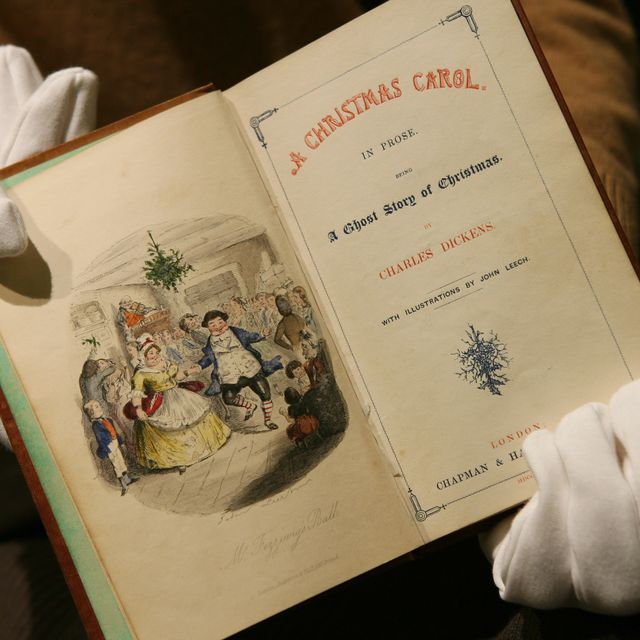

'A Christmas Carol'

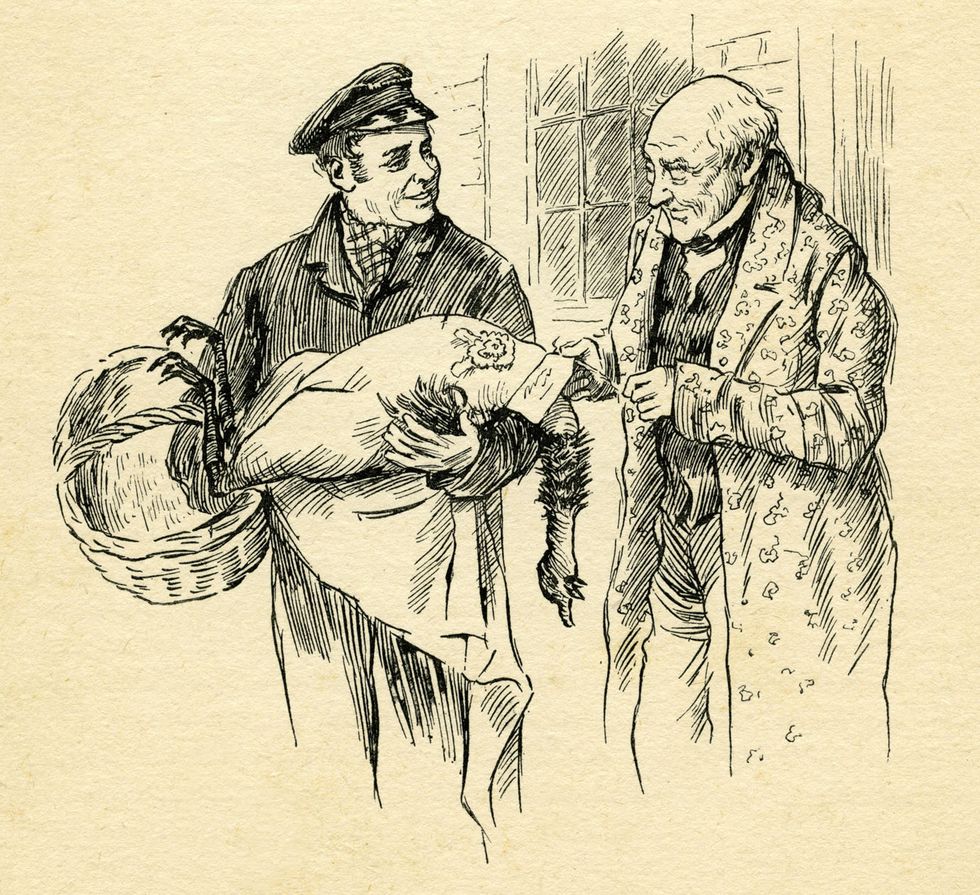

In 1842, Dickens wrote another novel, "Barnaby Rudge." The following year, while writing the novel "Martin Chuzzlewit," Dickens visited the industrial city of Manchester, England. He addressed a gathering of workers, and later he took a long walk and began to think about writing a Christmas book that would be a protest against the profound economic inequality he saw in Victorian England. Dickens published " A Christmas Carol " in December 1843, and it became one of his most enduring works.

Dickens traveled around Europe during the mid-1840s. After returning to England, he published five new novels: "Dombey and Son," "David Copperfield," "Bleak House," "Hard Times," and "Little Dorrit."

By the late 1850s , Dickens was spending more time giving public readings. His income was enormous, but so were his expenses, and he often feared he would be plunged back into the sort of poverty he had known as a child.

Charles Dickens, in middle age, appeared to be on top of the world. He was able to travel as he wished, and he spent summers in Italy. In the late 1850s, he purchased a mansion, Gad's Hill, which he had first seen and admired as a child.

Despite his worldly success, though, Dickens was beset by problems. He and his wife had a large family of 10 children, but the marriage was often troubled. In 1858, a personal crisis turned into a public scandal when Dickens left his wife and apparently began a secretive affair with actress Ellen "Nelly" Ternan, who was only 19 years old. Rumors about his private life spread. Against the advice of friends, Dickens wrote a letter defending himself, which was printed in newspapers in New York and London.

For the last 10 years of his life, Dickens was often estranged from his children, and his relationships with old friends suffered.

Though he hadn't enjoyed his tour of America in 1842, Dickens returned in late 1867. He was again welcomed warmly, and large crowds flocked to his public appearances. He toured the East Coast of the United States for five months.

He returned to England exhausted, yet continued to embark on more reading tours. Though his health was failing, the tours were lucrative, and he pushed himself to keep appearing onstage.

Dickens planned a new novel for publication in serial form. "The Mystery of Edwin Drood" began appearing in April 1870. On June 8, 1870, Dickens spent the afternoon working on the novel before suffering a stroke at dinner. He died the next day.

The funeral for Dickens was modest, and praised, according to a New York Times article, as being in keeping with the "democratic spirit of the age." Dickens was accorded a high honor, however, as he was buried in the Poet's Corner of Westminster Abbey, near other literary figures such as Geoffrey Chaucer , Edmund Spenser , and Dr. Samuel Johnson.

The importance of Charles Dickens in English literature remains enormous. His books have never gone out of print, and they are widely read to this day. As the works lend themselves to dramatic interpretation, numerous plays, television programs, and feature films based on them continue to appear.

- Kaplan, Fred. "Dickens: a Biography." Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

- Tomalin, Claire. "Charles Dickens: a Life." Penguin Press, 2012.

- Why Dickens Wrote 'A Christmas Carol'

- A Review of 'David Copperfield'

- How Can You Stretch a Paper to Make it Longer?

- Discussion Questions for 'A Christmas Carol'

- A Summary of 'A Christmas Carol'

- The History of Christmas Traditions

- Where Did the Term 'Humbug' Originate?

- The Most Important Quotes From Charles Dickens's 'Oliver Twist'

- Life of Wilkie Collins, Grandfather of the English Detective Novel

- Notable Authors of the 19th Century

- 'Great Expectations' Review

- Dickens' 'Oliver Twist': Summary and Analysis

- "A Tale of Two Cities" Discussion Questions

- The Haunted House (1859) by Charles Dickens

- 'A Christmas Carol' Quotations

- Lowell Mill Girls

Charles Dickens

By ellen gutoskey | jan 10, 2020.

AUTHORS (1812–1870); PORTSMOUTH, ENGLAND

Born in Portsmouth, England, on February 7, 1812, author Charles Dickens will forever be linked to the streets of 19th-century London, where so many of his books took place. But there's a lot to learn about the writing process behind those novels and the man himself, so read on for some interesting facts about one of the most celebrated English writers of all time.

1. Many of Charles Dickens’s novels were originally released as serials.

From 1836 to 1837, relative newcomer Charles Dickens , going by the name of Boz, published a chapter a week of his novel The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club , or The Pickwick Papers . It was an overwhelming success for Dickens, who soon shed his pseudonym and went on to release his most famous works in serialized form, including Oliver Twist , Great Expectations , Hard Times , Bleak House , David Copperfield , Our Mutual Friend , and more.

2. Charles Dickens's book Hard Times wasn't set in London.

In most Dickens novels, the city of London is just as complex, unforgettable, and alive as iconic characters like the Artful Dodger and Miss Havisham. For Hard Times , however, he took a break from his go-to setting to explore a fictional town called Coketown, which he based on the grim, soot-covered industrial mill towns from the Victorian era.

3. A Christmas Carol wasn’t Charles Dickens’s only Christmas story.

In the years after publishing A Christmas Carol in 1843, Dickens penned four other Christmas-themed tales, most of which also feature supernatural elements and not-so-subtle messages about family, finances, and class struggle. In 1844’s The Chimes , Dickens tells the story of an old “ticket-porter,” who is shown visions of the future by the spirits of the church bells and their goblin attendants. In 1845’s The Cricket on the Hearth , a Scrooge-like toymaker undergoes a personal transformation after a familial crisis prompts him to seek advice from—you guessed it—a cricket on the hearth. Find out more about those and his other holiday works here .

4. Charles Dickens intended Great Expectations to be funny.

In Charles Dickens’s opinion, Great Expectations —the classic (and pretty dark) story about orphaned Pip’s conflict-fraught journey to find his place in the world—had an undeniable sense of humor to it, too.

“You will not have to complain of the want of humour as in the Tale of Two Cities ,” he wrote to a friend. “I have put a child and a good-natured foolish man, in relations that seem to me very funny.”

He also wrote that he thought it could be published as a serial, “in a most singular and comic manner.”

5. Some of Charles Dickens’s children are named after other writers.

Between 1837 and 1852, Dickens and his wife, Catherine, welcomed 10 children, nine of whom lived into adulthood. A few are named after well-known authors whom Dickens knew or admired, including Henry Fielding, Alfred Tennyson, Walter Savage Landor, and Edward Bulwer-Lytton.

The children didn’t all follow their father’s path—two served in the military, one became a judge, and one pursued painting, for example—but some did: his eldest son, Charles Jr., edited Dickens’s literary magazine, and his daughter, Mary, helped edit and publish volumes of her father’s letters. Dickens, for his part, was not always thrilled about his sizable brood of offspring.

“I begin to count the children incorrectly, there are so many,” he once said . “And to find fresh ones coming down to dinner in a perfect procession, when I thought there were no more.”

Here’s the full list, from oldest to youngest:

- Charles Culliford Boz Dickens, Jr. (1837-1896)

- Mary “Mamie” Angela Dickens (1838-1896)

- Catherine "Kate" Elizabeth Macready Perugini (1839-1929)

- Walter Savage Landor Dickens (1841-1863)

- Francis Jeffrey Dickens (1844-1886)

- Alfred D’Orsay Tennyson Dickens (1845-1912)

- Sydney Smith Haldimand Dickens (1847-1872)

- Sir Henry Fielding Dickens (1849-1933)

- Dora Annie Dickens (1850-1851)

- Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens (1852-1902)

6. Charles Dickens and his wife, Catherine, eventually divorced.

Charles Dickens and his wife, Catherine, ended their 22-year marriage in 1858, with Charles claiming that it was his wife who wanted to leave him. What he didn’t mention, however, was his alleged affair with actress Ellen “Nelly” Ternan, whom he had met in 1857 when she was just 18 years old.

According to a recently released letter that Catherine’s neighbor Edward Dutton Cook wrote after the separation, it seems like Dickens turned rather nasty during the divorce, even trying to commit Catherine to an insane asylum.

“He [Charles] discovered at last that she had outgrown his liking. She had borne 10 children and had lost many of her good looks, was growing old, in fact,” Cook wrote. “He even tried to shut her up in a lunatic asylum, poor thing! But bad as the law is in regard to proof of insanity he could not quite wrest it to his purpose.”

7. Charles Dickens’s books were used by doctors and scientists.

A 2018 exhibition at London’s Charles Dickens Museum revealed just how much Dickens’s comprehensive descriptions of common (and uncommon) afflictions in his novels helped inform those studying them. Passages describing the symptoms of tuberculosis and dyslexia were used by medical students learning how to diagnose patients, and obesity hypoventilation syndrome is sometimes called Pickwickian Syndrome after Joe the "fat boy," a character from The Pickwick Papers whose size caused him to snore loudly.

Books by Charles Dickens.

- The Pickwick Papers (1836-1837)

- Oliver Twist (1837-1839)

- Nicholas Nickleby (1838-1839)

- The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-1841)

- Barnaby Rudge (1841)

- Martin Chuzzlewit (1842-1844)

- A Christmas Carol (1843)

- Dombey and Son (1846-1848)

- David Copperfield (1849-1850)

- Bleak House (1852-1853)

- Hard Times (1854)

- Little Dorrit (1855-1857)

- A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Great Expectations (1860-1861)

- Our Mutual Friend (1864-1865)

- The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870) (Unfinished)

Memorable Charles Dickens quotes.

- “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” —A Tale of Two Cities

- “The pain of parting is nothing to the joy of meeting again.” —Nicholas Nickleby

- “A word in earnest is as good as a speech.” —Bleak House

- “Ideas, like ghosts (according to the common notion of ghosts), must be spoken to a little before they will explain themselves.” —Dombey and Son

- “No one is useless in this world ... who lightens the burden of it for any one else.” —Our Mutual Friend

- “The civility which money will purchase, is rarely extended to those who have none.” —Sketches by Boz

- “Reflect upon your present blessings—of which every man has many—not on your past misfortunes, of which all men have some.” —Sketches by Boz

- “[If] there were no bad people, there would be no good lawyers.” —The Old Curiosity Shop

- “Take nothing on its looks; take everything on evidence. There’s no better rule.” —Great Expectations

- “God bless us, every one!” —A Christmas Carol

Learn more about Charles Dickens:

- Dickens Fast Facts

- Dickens Biography

- Dickens' Novels

- Dickens' Characters

- Illustrating Dickens

- Dickens' London

- Mapping Dickens

- Dickens & Christmas

- Family and Friends

- Dickens in America

- Dickens' Journalism

- Dickens on Stage

- Dickens on Film

- Reading Dickens

- Dickens Glossary

- Dickens Quotes

- Bibliography

- Dickens Collection

- About this Site

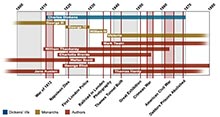

Dickens Timelines

Discover Dickens' life and work depicted graphically .

Catherine Dickens

Catherine (Hogarth) Dickens (1815-1879) - Charles Dickens' wife, with whom he fathered 10 children. She was born in Scotland on May 19, 1815 and came to England with her family in 1834. Catherine was the daughter of George Hogarth , editor of the Evening Chronicle where Dickens was a young journalist. They were married on April 2, 1836 in St. Luke's Church, Chelsea and honeymooned in Chalk, near Chatham.

Charles was undoubtably in love at the outset but his feelings for Catherine wained as the family grew. With the birth of their last child in 1852 Dickens found Catherine an increasingly incompetent mother and housekeeper ( Johnson, 1952, p. 905-909 ) . Their separation, in 1858, was much publicized and rumors of Dickens unfaithfulness abounded, which he vehemently denied in public. Dickens and Catherine had little correspondence after the break, Catherine moving to a house in London with oldest son, Charley , and Dickens retreating to Gads Hill in Kent with Catherine's sister, Georgina , and all of the children except Charlie remaining with him. On her deathbed in 1879 she gave her collection of Dickens' letters to daughter Kate instructing her to " Give these to the British Museum, that the world may know he loved me once " ( Schlicke, 1999, p. 153-157 ) .

Katherine is buried at Highgate Cemetery , London.

Read a letter from Dickens to John Forster concerning separation from Catherine.

What Shall We Have for Dinner?

Around 1850 Catherine released a collection of recipes and bills of fare for dinners for from two to eighteen people. The book, published by Bradbury and Evans, was called What Shall We Have for Dinner? and was written under the pen name Lady Maria Clutterbuck. Charles Dickens wrote the introduction using Maria's voice ( Nayder, 2011, p. 186-189 ) . The book is referred to as the source of Christmas dinner in Thomas Keneally's novel The Dickens Boy .

Amazon.com: The Other Dickens: A Life of Catherine Hogarth by Lillian Nayder

The Life of Charles Dickens

An illustrated hypertext biography of charles dickens, childhood and education.

- The Law and Early Jounalism

- Early Novels

- Middle Years

- Later Years

At this point the family consisted of Charles, older sister Fanny , younger brothers Alfred and Frederick , and younger sister Letitia . Everyone except Charles and Fanny went to live in the Marshalsea with their parents. Fanny was boarding at the Royal Academy of Music, and Charles initially lodged with a landlady in Camden Town in north London. This proved to be too long a walk every day to the blacking factory and his family in the Marshalsea, so a room was found for him on Lant Street in Southwark near the prison.

Young Charles, who dreamed of growing up a gentleman, found these dreams dashed working alongside common boys at the blacking factory and later wrote "It is wonderful to me how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age." Dickens shared this painful part of his childhood through the story of David Copperfield although no one realized it was autobiographical until related by biographer John Forster after Dickens' death ( Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 22-39 ) .

Charles was to further his education at Wellington House Academy , a school run by the harsh schoolmaster William Jones , a man who delighted in corporal punishment and who Dickens later described as " by far the most ignorant man I have ever had the pleasure to know ". Charles would spend nearly three years, aged 12-15, at Wellington House, leaving in the spring of 1827 ( Slater, 2009, p. 25-27 ) . Many of his experiences at school, and the masters who taught there, would later find their way into his fiction.

The Law and Early Journalism

Charles had been fascinated with the theatre since childhood and often attended the theatre to break the monotony of reporting on parliamentary proceedings. He wrote to George Bartley, manager of the Covent Garden Theatre, in 1832 asking for an audition, which was granted. On the day of the audition Charles was ill with a bad cold and inflammation of the face and missed the appointment. He wrote to Bartley explaining the illness and that he would apply for another audition next season. He would later marvel at how near he came to a very different sort of life ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 139-140 ) .

Dickens, writing feverishly, as well as holding down the job of a reporter, now found himself in the throes of romance. He became a regular visitor to the Hogarth household and soon proposed marriage, which Catherine quickly accepted ( Slater, 2009, p. 47 ) . They were married at St. Luke's church, Chelsea on April 2, 1836. Two months previous his collection of short stories was published in book form by John Macrone entitled Sketches by Boz with illustrations by popular artist George Cruikshank ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 174 ) . Dickens' pseudonym Boz came from his younger brother Augustus's through-the-nose pronunciation of his own nickname, Moses.

The Early Novels

Upon returning home he penned the promised travel book, American Notes , a rather unflattering description of America, and followed that with Martin Chuzzlewit , published in monthly parts, in which the protagonist goes to America and is subjected to the same sort of puffed up, mercenary people Dickens found there. The story was not well received and did not sell well ( Patten, 1978, p. 133 ) . Neither had Barnaby Rudge ( Schlicke, 1999, p. 33 ) , and Dickens felt that perhaps his lamp had gone out.

Dickens found himself in dire financial straits. He had borrowed heavily from his publishers for the American trip and his family continued to grow with their fifth child, son Francis , on the way. His feckless father was borrowing money in Charles' name behind his back. He needed an idea for a new book that would satisfy his pecuniary problems ( Slater, 2009, p. 215-220 ) .

The seeds for the story that became A Christmas Carol were planted in Dickens' mind during a trip to Manchester to deliver a speech in support of education. Thoughts of education as a remedy for crime and poverty, along with scenes he had recently witnessed at the Field Lane Ragged School , caused Dickens to resolve to " strike a sledge hammer blow " for the poor ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 408-409 ) . As the idea for the story took shape and the writing began in earnest, Dickens became engrossed in the book. He wrote that as the tale unfolded he " wept and laughed, and wept again' and that he 'walked about the black streets of London fifteen or twenty miles many a night when all sober folks had gone to bed " ( Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 326 ) . Dickens was at odds with Chapman and Hall over the low receipts from Martin Chuzzlewit and decided to self-publish the book, overspending on color illustrations and lavish binding and then setting the cost low so that everyone could afford it ( Slater, 2009, p. 220 ) . The book was an instant success but royalties were low after production costs were paid .

Serialization of Martin Chuzzlewit came to a conclusion in July, 1844, and Dickens conceived of the idea of another travel book; this time he would go to Italy ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 426 ) . The family spent a year in Italy, first in Genoa, and then traveling through the southern part of the country. He wrote the second of his Christmas Books, The Chimes ( Slater, 2009, p. 230-231 ) , while in Genoa and sent his adventures home in the form of letters which were published in the Daily News . These were collected into a single volume entitled Pictures from Italy in May, 1846 ( Davis, 1999, p. 318 ) .

During the 1840s Dickens, with a troupe of friends and family in tow, began acting in amateur theatricals in London and across Britain. Charles worked tirelessly as actor and stage manager and often adjusted scenes, assisted carpenters, invented costumes, devised playbills, and generally oversaw the entire production of the performances ( Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 436 ) . The Dickens' amateur troupe even performed twice for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert ( Davis, 1999, p. 4 ) .

The Middle Years

In 1839 the Dickens family moved from Doughty Street to a larger home at Devonshire Terrace near Regent's Park . The family continued to grow with the addition of sons Alfred (1845), Sydney (1847), and Henry (1849).

Dickens continued to write a book for the Christmas season every year. After A Christmas Carol (1843), and The Chimes (1844), he followed with The Cricket on the Hearth (1845), The Battle of Life (1846), and The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain (1848). All of these sold well at the time of publication but none endured as A Christmas Carol has ( Schlicke, 1999, p. 97 ) .

Dickens had begun writing an autobiography in the late 1840s that he shared with his friend and future biographer, John Forster ( Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 22 ) . He found the writing too painful and opted instead to work his story into the fictional account of David Copperfield , which he later described as his personal favorite among his novels ( David Copperfield , p. xii ) . The story was serialized from May 1849 until November 1850. During the writing of Copperfield the tireless Dickens began another venture, a weekly magazine called Household Words . Charles worked as editor as well as contributor with additional pieces supplied by other writers. Also during the writing of Copperfield Catherine gave birth to a daughter, named for David Copperfield's wife Dora ( Slater, 2009, p. 312 ) . Dora , sickly from birth, died at 8 months old ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 627-628 ) .

Dickens followed David Copperfield with what many consider one of his finest novels, Bleak House ( Davis, 1999, p. 35 ) . Dickens used his previous experience as a court reporter to tell the story of a prolonged case in the Courts of Chancery. During the writing of Bleak House Catherine gave birth to a son, Edward (1852), nicknamed Plorn. Edward would be last of Charles and Catherine's children and the family moved again, this time to Tavistock House . Following Bleak House Dickens serialized his next book, Hard Times , in his weekly magazine, Household Words . Following Hard Times Dickens returned to the painful childhood memory of his father's imprisonment for debt with the story of Little Dorrit . Amy Dorrit's father, William , was a prisoner in the Marshalsea debtor's prison and Amy was born there.

During the 1850s Charles and Catherine's marriage started to show signs of trouble. Dickens grew increasingly dissatisfied with Catherine whom, after giving birth to ten children, had grown quite stout and lethargic. She was increasingly unable to keep up with her energetic husband ( Schlicke, 1999, p. 155 ) . The problem came to a head when Dickens became enthralled with a young actress he met during one of his amateur theatricals, Ellen Ternan . Charles and Catherine were separated in 1858 and caused a public stir mostly contributed to by Dickens' desire to exonerate himself ( Johnson, 1952, p. 922-925 ) . All of the Dickens children, with exception of Charley , would live with their father, as would Catherine's sister, Georgina . The relationship with Ternan, the depth of which is still being debated ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 914-918 ) , would continue the rest of Dickens' life.

Dickens and his children now moved into the mansion Gads Hill Place in Kent that he had purchased in 1856 near his childhood home of Chatham. As a boy, Dickens would walk by the impressive house, built in 1780, with his father who told him that with hard work he could someday live in such a splendid mansion ( Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 6 ) . In 1864 Dickens received, from actor friend Charles Fechter, a two-story Swiss chalet that Dickens had installed across the road from Gads Hill with a tunnel under the road for access ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 955-956 ) . Dickens wrote his his final works in his study on the top floor of the chalet.

The separation with Catherine also caused a rift between Dickens and his publishers, Bradbury and Evans . Bradbury and Evans also published the popular magazine Punch . When they refused to publish Dickens' personal statement , his explanation for the recent separation, Charles was furious and refused to have further dealings with them. He ceased publication of his weekly magazine, Household Words , continuing it under a new name, All the Year Round , and with his old publishers, Chapman and Hall ( Kaplan, 1988, p. 395-401 ) .

In the 1850s Dickens began reading excerpts of his books in public, first for charity, and, beginning in 1858, for profit. These readings proved extremely popular with the public and Dickens continued them for the rest of his life. The readings included excerpts from his Christmas books , David Copperfield , and Nicholas Nickleby , with A Christmas Carol , for which he wrote a condensed verion , and The Trial from Pickwick being the most popular ( Davis, 1999, p. 328 ) . He later included the dramatic murder of Nancy by Bill Sikes in Oliver Twist , the performance of which took a toll on Dickens' fragile health ( Johnson, 1952, p. 1144 ) .

The Later Years

In May, 1864, Dickens began publication of what would be his last completed novel. Published in monthly installments, Our Mutual Friend touches the familiar theme of the evils and corruption that the love of money brings. Poor health causing perhaps a stutter in his usual creative genius, Dickens found beginning the novel difficult, he wrote to Forster "Although I have not been wanting in industry, I have been wanting in invention" ( Letters, 1998, v. 10, p. 414 ) . After finally finding his footing, the monthly installments did not sell well despite a massive advertising blitz ( Patten, 1978, p. 307-308 ) .

On the 9th of June, 1865, traveling back from France with Ellen Ternan and her mother, and with the latest installment of Our Mutual Friend , the train in which they were traveling was involved in an accident in Staplehurst, Kent. Many were killed but Dickens and his companions escaped serious injury although Dickens was severely shaken. Three years later he wrote that he still experienced " vague rushes of terror even riding in hansom cabs " ( Johnson, 1952, p. 1018-1021 ) .

In the late 1850s Dickens began to contemplate a second visit to America , tempted by the money he could make by extending his public readings there. Despite pleas not to go from friends and family because of increasingly ill health ( Johnson, 1952, p. 1070 ) , he finally decided to go and arrived in Boston on November 19, 1867. The original plan called for a visit to Chicago and as far west as St. Louis. Because of ill health and bad weather this idea was scrapped and Dickens did not venture from the northeastern states ( Slater, 2009, p. 580 ) . He stayed for 5 months and gave 76 extremely popular performances for which he earned, after expenses, an incredible £19,000 ( Schlicke, 1999, p. 17 ) .

Dickens returned home in May, 1868, somewhat revitalized during the sea voyage, to a full load of work. He immediately plunged back into editing All the Year Round and, in October, began a farewell reading tour of Britain that included a new, very passionate, and physically taxing, performance of the murder of Nancy from Oliver Twist ( Davis, 1999, p. 353 ) .

Monthly publication of what was to be his last novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood , began in April, 1870. On the evening of June 8, 1870, Dickens, after working on the latest installment of Drood that morning in the chalet at Gads Hill , suffered a stroke and died the next day ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 1076-1079 ) . The Mystery of Edwin Drood was exactly half finished and the mystery is unsolved to this day .

Dickens had wished to be buried, without fanfare, in a small cemetery in Rochester, but the Nation would not allow it. He was laid to rest in Poet's Corner, Westminster Abbey, the flowers from thousands of mourners overflowing the open grave ( Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 513 ) .

Affiliate Links Disclosure The Charles Dickens Page is a member of affiliate programs at Amazon and Zazzle. This means that there are links that take users to sites where products that we recommend are offered for sale. If purchases are made on these sites The Charles Dickens Page receives a small commission.

- About this site

- What's New?

The Charles Dickens Page

Bringing the genius of charles dickens to a new generation of readers since 1997.

- A Christmas Carol

- Bits of Dickens

- Dickens Maps

- Murder of Nancy

- Please Help

Charles Dickens. The name conjures up visions of plum pudding and Christmas punch, quaint coaching inns and cozy firesides, but also of orphaned and starving children, misers, murderers, and abusive schoolmasters. Dickens was 19th century London personified, he survived its mean streets as a child and, largely self-educated, possessed the genius to become the greatest writer of his age.

Learn about Charles Dickens' influence on the celebration of Christmas!

Meet over 1000 Charles Dickens characters , cross referenced, and many with illustrations.

Stumped by a word or phrase while reading Dickens? Find it in our glossary .

Explore Charles Dickens' London with our Dickens' London Map.

Learn what it was like to live in Charles Dickens' London.

Learn about Charles Dickens' life, family, and work through an illustrated hypertext biography .

Learn about Charles Dickens' home Gads Hill Place.

Charles Dickens was born on February 7, 1812, the son of a clerk at the Navy Pay Office. His father, John Dickens , continually living beyond his means, was imprisoned for debt in the Marshalsea in 1824. 12-year-old Charles was removed from school and sent to work at a boot-blacking factory earning six shillings a week to help support the family. This dark experience cast a shadow over the clever, sensitive boy that became a defining experience in his life, he would later write " It is wonderful to me how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age " ( Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 25 ) .

This childhood poverty and feelings of abandonment, although unknown to his readers until after his death, would be a heavy influence on Dickens' later views on social reform and the world he would create through his fiction.

Dickens would go on to write 15 major novels including, Oliver Twist , Bleak House , Great Expectations , A Tale of Two Cities , and his personal favorite, David Copperfield . He will forever be associated with the celebration of Christmas due to his Christmas Books , the most popular being A Christmas Carol . Dickens also edited, and contributed to, weekly journals Household Words and All the Year Round . Near the end of his life he traveled throughout Britain and America giving public readings of his work.

Charles Dickens died an old man of 57, worn out with work and travel, on June 9, 1870. He wished to be buried, without fanfare, in a small cemetery in Rochester, Kent , but the Nation would not allow it. He was laid to rest in Poet's Corner, Westminster Abbey , the flowers from thousands of mourners overflowing the open grave. Among the more beautiful bouquets were many simple clusters of wildflowers, wrapped in rags.

Annotated A Christmas Carol

Dickens pared down A Christmas Carol for his public readings. Read an annotated version of Dickens' own reading text that can be read in a single sitting!

The Many Faces of Ebenezer Scrooge

The Internet Movie Database lists more than 100 actors who have portrayed the famous Dickensian miser. Some of the best are pictured here.

Bits of Dickens...

Short examples of Charles Dickens' work that can be read in a single sitting:

- Oliver Asks for More (Oliver Twist)

- Cratchit's Christmas (A Christmas Carol)

- Steamboat Trip (American Notes)

- Omnibuses (Sketches by Boz)

- Mrs Gamp (Martin Chuzzlewit)

- The Haves and the Have Nots (American Notes)

- Mr Pickwick Meets the Lady in Yellow Curl Papers (Pickwick Papers)

- More Bits of Dickens

Explore the World of Charles Dickens with Maps

- Charles Dickens' London

- Aerial Charles Dickens' London

- Dickens' Rochester/Chatham

- Dickens' Higham

- Dickens' American Travels 1842

- Dickens' American Reading Tour 1867-68

- Dickens' Pictures from Italy Map 1844-45

- Oliver Twist Map - London Locations

- A Tale of Two Cities - London

- A Tale of Two Cities - Paris

- Great Expectations Connections

- Dickens' Reading Tour of England, Scotland, and Ireland 1858

- Map of Nell's Journey from The Old Curiosity Shop

- The London of Barnaby Rudge

- London Map of Dickens' Night Walks

- London Locations in Bleak House

- Pickwickian Travels

Sir Roger de Coverley

The fiddler struck up Sir Roger de Coverley. Then old Fezziwig stood out to dance with Mrs Fezziwig. Top couple, too; with a good stiff piece of work cut out for them.

The dance performed by Fezziwig and company was popular in the eighteenth century and was considered old-fashioned by Dickens' time. Named for a ficticious character in The Spectator (1711) the dance resembled the Virginia Reel. It was usually the last dance performed during an evening of entertainment ( Hearn, 2004, pp. 70-71, n. 52 ) .

Read the story of how a simple mistake took the lives of ten people, ruined the life of Henry Benge, and shortened the life of Charles Dickens.

Boz Spotlight

The fascinating story of the fast-paced life of the literary superstar of the Victorian era.

Boz Spotlight Archive

Cursing in Dickens

7 - Sketches by Boz 29 - Pickwick Papers 12 - Nicholas Nickleby 8 - Barnaby Rudge 1 - David Copperfield 3 - Bleak House 3 - Hard Times 3 - Little Dorrit 1 - Tale of Two Cities 3 - Great Expectations 1 - Our Mutual Friend 2 - Edwin Drood

Learn more about Charles Dickens

- Charles Dickens Biography

- The Mystery of Ellen Ternan

- Dickens Family Tree

- The Charles Dickens Museum

- Dickens' Birthplace Museum

- Gads Hill Place

- The Cleveland Street Workhouse

- Charles Dickens Cigarette Cards

- Charles Dickens Characters

- Dickens' Character Dolls

Organizations

- The Dickens Fellowship

- The Dickens Society

- The Dickens Project

Special Guests

- Guest contributors to this site

My Favorite Places

- Gina Dalfonzo's DickensBlog

- Where was Dickens?

- Charles Dickens Info

- The Victorian Dictionary

- The Victorian Web

- Charles Dickens' Journals Online

- Charles Dickens' Letters

In the Charles Dickens tradition of helping the needy and the sick this site supports

Finding cures. Saving children.

Affiliate Links Disclosure The Charles Dickens Page is a member of affiliate programs at Amazon and Zazzle. This means that there are links that take users to sites where products that we recommend are offered for sale. If purchases are made on these sites The Charles Dickens Page receives a small commission.

Charles Dickens

- Classic Literature

- Classic Authors

Charles Dickens Biography

Dickens, Charles John Huffam (1812-1870), probably the best-known and, to many people, the greatest English novelist of the 19th century. A moralist, satirist, and social reformer, Dickens crafted complex plots and striking characters that capture the panorama of English society.

Dickens's novels criticize the injustices of his time, especially the brutal treatment of the poor in a society sharply divided by differences of wealth. But he presents this criticism through the lives of characters that seem to live and breathe. Paradoxically, they often do so by being flamboyantly larger than life: The 20th-century poet and critic T. S. Eliot wrote, "Dickens's characters are real because there is no one like them." Yet though these characters range through the sentimental, grotesque, and humorous, few authors match Dickens's psychological realism and depth. Dickens's novels rank among the funniest and most gripping ever written, among the most passionate and persuasive on the topic of social justice, and among the most psychologically telling and insightful works of fiction. They are also some of the most masterful works in terms of artistic form, including narrative structure, repeated motifs, consistent imagery, juxtaposition of symbols, stylization of characters and settings, and command of language.

Dickens established (and made profitable) the method of first publishing novels in serial instalments in monthly magazines. He thereby reached a larger audience including those who could only afford their reading on such an instalment plan. This form of publication soon became popular with other writers in Britain and the United States.

II Early Years

Dickens was born in Portsmouth, on England's southern coast. His father was a clerk in the British Navy pay office a respectable position, but with little social status. His paternal grandparents, a steward (property manager) and a housekeeper, possessed even less status, having been servants, and Dickens later concealed their background. Dickens's mother supposedly came from a more respectable family. Yet two years before Dickens's birth, his mother's father was caught embezzling and fled to Europe, never to return.

The family's increasing poverty forced Dickens out of school at age 12 to work in Warren's Blacking Warehouse, a shoe-polish factory, where the other working boys mocked him as "the young gentleman." His father was then imprisoned for debt. The humiliations of his father's imprisonment and his labor in the blacking factory formed Dickens's greatest wound and became his deepest secret. He could not confide them even to his wife, although they provide the unacknowledged foundation of his fiction.

Soon after his father's release from prison, Dickens got a better job as errand boy in law offices. He taught himself shorthand to get an even better job later as a court stenographer and as a reporter in Parliament. At the same time, Dickens, who had a reporter's eye for transcribing the life around him, especially anything comic or odd, submitted short sketches to obscure magazines. The first published sketch, "A Dinner at Poplar Walk" (later retitled "Mr. Minns and His Cousin") brought tears to Dickens's eyes when he discovered it in the pages of The Monthly Magazine in 1833. From then on his sketches, which appeared under the pen name "Boz" (rhymes with "rose") in The Evening Chronicle, earned him a modest reputation. Boz originated as a childhood nickname for Dickens's younger brother Augustus.

Dickens became a regular visitor at the home of George Hogarth, editor of The Evening Chronicle, and in 1835 became engaged to Hogarth's daughter Catherine. Publication of the collected Sketches by Boz in 1836 gave Dickens sufficient income to marry Catherine Hogarth that year. The marriage proved unhappy.

III Literary Career

Soon after Sketches by Boz appeared, the fledgling publishing firm of Chapman and Hall approached Dickens to write a story in monthly instalments. The publisher intended the story as a backdrop for a series of woodcuts by the then-famous artist Robert Seymour, who had originated the idea for the story. With characteristic confidence, Dickens, although younger and relatively unknown, successfully insisted that Seymour's pictures illustrate his own story instead. After the first instalment, Dickens wrote to the artist he had displaced to correct a drawing he felt was not faithful enough to his prose. Seymour made the change, went into his backyard, and expressed his displeasure by blowing his brains out. Dickens and his publishers simply pressed on with a new artist. The comic novel, The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, appeared serially in 1836 and 1837 and was first published in book form The Pickwick Papers in 1837.

The runaway success of The Pickwick Papers , as it is generally known today, clinched Dickens's fame. There were Pickwick coats and Pickwick cigars, and the plump, spectacled hero, Samuel Pickwick, became a national figure. Four years later, Dickens's readers found Dolly Varden, the heroine of Barnaby Rudge (1841), so irresistible that they named a waltz, a rose, and even a trout for her. The widespread familiarity today with Ebenezer Scrooge and his proverbial hard-heartedness from A Christmas Carol (1843) demonstrate that Dickens's characters live on in the popular imagination.

Dickens published 15 novels, one of which was left unfinished at his death. These novels are, in order of publication with serialization dates given first: The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (1836-1837; 1837); The Adventures of Oliver Twist (1837-1839; 1838); The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby (1838-1839; 1839); The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-1841; 1841); Barnaby Rudge (1841); Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-1844; 1844); Dombey and Son (1846-1848; 1848); The Personal History of David Copperfield (1849-1850; 1850); Bleak House (1852-1853; 1853); Hard Times (1854); Little Dorrit (1855-1857; 1857); A Tale of Two Cities (1859); Great Expectations (1860-1861; 1861); Our Mutual Friend (1864-1865; 1865); and The Mystery of Edwin Drood (unfinished; 1870).

Through his fiction Dickens did much to highlight the worst abuses of 19th-century society and to prick the public conscience. But running through the main plot of the novels are a host of subplots concerning fascinating and sometime ludicrous minor characters. Much of the humor of the novels derives from Dickens's descriptions of these characters and from his ability to capture their speech mannerisms and idiosyncratic traits.

A Early Fiction

Dickens was influenced by the reading of his youth and even by the stories his nursemaid created, such as the continuing saga of Captain Murderer. These childhood stories, as well as the melodramas and pantomimes he saw in the theater as a boy, fired Dickens's imagination throughout his life. His favorite boyhood readings included picaresque novels such as Don Quixote by Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes and Tom Jones by English novelist Henry Fielding, as well as the Arabian Nights. In these long comic works, a roguish hero's exploits and adventures loosely link a series of stories.

The Pickwick Papers , for example, is a wandering comic epic in which Samuel Pickwick acts as a plump and cheerful Don Quixote, and Sam Weller as a cockney version of Quixote's knowing servant, Sancho Panza. The novel's preposterous characters, high spirits, and absurd adventures delighted readers.

After Pickwick, Dickens plunged into a bleaker world. In Oliver Twist , he traces an orphan's progress from the workhouse to the criminal slums of London. Nicholas Nickleby , his next novel, combines the darkness of Oliver Twist with the sunlight of Pickwick. Rascality and crime are part of its jubilant mirth.

The Old Curiosity Shop broke hearts across Britain and North America when it first appeared. Later readers, however, have found it excessively sentimental, especially the pathos surrounding the death of its child-heroine Little Nell. Dickens's next two works proved less popular with the public.

Barnaby Rudge , Dickens's first historical novel, revolves around anti-Catholic riots that broke out in London in 1780. The events in Martin Chuzzlewit become a vehicle for the novel's theme: selfishness and its evils. The characters, especially the Chuzzlewit family, present a multitude of perspectives on greed and unscrupulous self-interest. Dickens wrote it after a trip to the United States in 1842.

B Mature Fiction

Many critics have cited Dombey and Son as the work in which Dickens's style matures and he succeeds in bringing multiple episodes together in a tight narrative. Set in the world of railroad-building during the 1840s, Dombey and Son looks at the social effects of the profit-driven approach to business. The novel was immediately successful.

Dickens always considered David Copperfield to be his best novel and the one he most liked. The beginning seems to be autobiographical, with David's childhood experiences recalling Dickens's own in the blacking factory. The unifying theme of the book is the "undisciplined heart" of the young David, which leads to all his mistakes, including the greatest of them, his mistaken first marriage.

Bleak House ushers in Dickens's final period as a satirist and social critic. A court case involving an inheritance forms the mainspring of the plot, and ultimately connects all of the characters in the novel. The dominant image in the book is fog, which envelops, entangles, veils, and obscures. The fog stands for the law, the courts, vested interests, and corrupt institutions. Dickens had a long-standing dislike of the legal system and protracted lawsuits from his days as a reporter in the courts.

A novel about industry, Hard Times , followed Bleak House in 1854. In Hard Times , Dickens satirizes the theories of political economists through exaggerated characters such as Mr. Bounderby, the self-made man motivated by greed, and Mr. Gradgrind, the schoolmaster who emphasizes facts and figures over all else. In Bounderby's mines, lives are ground down; in Gradgrind's classroom, imagination and feelings are strangled.

The pervading image of Little Dorrit is the jail. Dickens's memory of his own father's time in debtors' prison adds an autobiographical touch to the novel. Little Dorrit also contains Dickens's invention of the Circumlocution Office, the archetype of all bureaucracies, where nothing ever gets done. Through this critique and others, such as the circular legal system in Bleak House , Dickens also investigated the ways in which art makes meaning and the workings of his own narrative style.

A Tale of Two Cities is set in London and Paris during the French Revolution (1789-1799). It stands out among the novels as a work driven by incident and event rather than by character and is critical both of the violence of the mob and of the abuses of the aristocracy, which prompted the revolution. The successful Tale of Two Cities was soon followed by Great Expectations , which marked a return to the more familiar Dickensian style of character-driven narrative. Its main character, Pip, tells his own story. Pip's "great expectations" are to lead an idle life of luxury. Through Pip, Dickens exposes that ideal as false.

Dickens's last complete novel is the dark and powerful Our Mutual Friend . A tale of greed and obsession, it takes place in an ill-lit and dirty London, with images of darkness and decay throughout. Only 6 of the 12 intended parts of Edwin Drood had been completed by the time Dickens died. He intended it as a mystery story concerning the disappearance of the title character.

IV Final Years

The end of Dickens's life was emotionally scarred by his separation from his dutiful wife, Catherine, as the result of his involvement with a young actress, Ellen Ternan. Catherine bore him ten children during their 22-year marriage, but he found her increasingly dull and unsympathetic. Against the advice of editors, Dickens published a letter vehemently justifying his actions to his readers, who would otherwise have known nothing about them.

Following the separation, Dickens continued his hectic schedule of novel, story, essay, and letter writing (his collected letters alone stretch thousands of pages); reform activities; amateur theatricals and readings; in addition to nightly social engagements and long midnight walks through London. His energy had always seemed to his friends inhuman, but he maintained this activity in his later years in disregard of failing health. Dickens died of a stroke shortly after his farewell reading tour, while writing The Mystery of Edwin Drood .

V Achievement

Dickens's social critique in his novels was sharp and pointed. As his biographer Edgar Johnson observed in Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph (1952), Dickens's criticism was aimed not just at "the cruelty of the workhouse and the foundling asylum, the enslavement of human beings in mines and factories, the hideous evil of slums where crime simmered and proliferated, the injustices of the law, and the cynical corruption of the lawmakers" but also at "the great evil permeating every field of human endeavour: the entire structure of exploitation on which the social order was founded."

British writer George Orwell felt that Dickens was not a revolutionary, however, despite his criticism of society's ills. Orwell points out that Dickens "has no constructive suggestions, not even a clear grasp of the nature of the society he is attacking, only an emotional perception that something is wrong." That instinctive feeling becomes so moving in the novels because Dickens made the injustices he hated concrete and specific, not abstract and general. His readers feel the abuses of 19th-century society as real through the life of his characters. Underlying and reinforcing that illusion of reality, however, is a rich and complicated system of symbolic imagery resulting from superb artistry.

Through his characters, Dickens also touched a range of readers, which was perhaps his greatest talent. As his friend John Forster wrote, his stories enthralled "judges on the bench and boys in the street" alike. The illiterate, often too poor to buy instalments themselves, pooled their pennies and got someone to read aloud to them.

Near the end of the serialization of The Old Curiosity Shop , crowds thronged to a New York pier to await the ship from London carrying the latest instalment. As it came to the dock people roared, "Is Little Nell dead?" The pathetic death of the novel's child-heroine, Nell Trent, became one of the most celebrated scenes in 19th-century fiction. Such public concern over Little Nell's end guaranteed that Dickens's social message would be heard, not only by his avid readers, but also by those in power.

Dickens was a careful craftsman, with a strong sense of design; his books were strictly outlined. Any current notions that Dickens's novels are long because he was paid by the word, or sloppy because he wrote them under pressure of monthly deadlines, are simply untrue. What organizes Dickens's stories is sometimes not apparent at first glance, although it makes sense in novels that emphasize character. It is the logic of psychology, the tensions and contradictions of our drives and emotions, which Dickens plumbed, laying side by side the best and the worst of the human heart. This is a very different logic from the order of realism that rests on common sense. Dickens detested common sense, seeing in its seeming obviousness a form of tyranny.

The theater was a crucial influence on Dickens's work. As a young man Dickens tried to go on stage, but he missed his audition because of a cold. Not only did Dickens later write comic plays, melodramas, and libretti (words for musical dramas), he was also often involved in amateur theatricals for good causes, and spent his last two decades reading his own stories to packed audiences. Dickens's readings were as much a sensation in England and America as was his writing, and they proved as profitable. The readings revealed the part of the man that made him a practiced magician and hypnotist as well.

Dickens's love of the theatrical makes his works lend themselves readily to media adaptations. Motion-picture or television versions exist for almost every one of them. A Christmas Carol was one of the earliest to be adapted, first appearing as the silent film Scrooge (1901), directed by Walter R. Booth. The most notable adaptations include A Christmas Carol (1938), directed by Edwin L. Marin and starring Reginald Owen, and, probably the most famous of all, A Christmas Carol (1951), directed by Brian Desmond Hart and starring Alastair Sim. A later production titled Scrooged (1988) was directed by Richard Donner and starred Bill Murray. David Lean directed the most famous of the many versions of Great Expectations (1946). The film Oliver! (1968), a musical based on Oliver Twist and directed by Carol Reed, won six Academy Awards. Nowadays people are probably more familiar with the many BBC television miniseries productions of Dickens's works.

Contributed By: Laurie Langbauer, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. Professor of English, University of North Carolina. Author of Novels of Everyday Life: The Series in English Fiction, 1850-1930.

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens, known as Charles Dicken in the literary world, was born on the 7th of February in 1812 in Landport, England. He was the intelligent son of John Dickens, a clerk in the navy pay office, and Elizabeth Dickens, who married John in 1809. Soon after his birth, the family moved to London , where Charles spent the formative years of his life. During his early years, he read voraciously including, Henry Fielding, Gil Blas, Robinson Crusoe , and Tobias Smollett. The sad memories of childhood, along with his encounter with different people, played a significant role in his early development.

Charles started education at a local school at the age of nine. However, the good fortune was short-lived, as he had to leave his school when his father became a victim of bad debt. To support his family, he was sent to work in Warren’s Blacking Factory, where he endured emotional trauma as well as isolation and mental torture. After some time, when his father was released, he was sent to Wellington House Academy. Still, the horrible work experience kept on haunting him, which he later fictionalized in his pieces, Great Expectations , and David Copperfield. He spent two years at school when in 1827, once again, he was forced to leave school and work as an office boy to support his family.

Marriage and Tragedy

While working as a journalist in 1834, Charles met Catherine Hogarth. They got engaged in 1835 and tied the knot the following year. The early years of their union were full of merriment. They traveled to Scotland and America together. They had ten children. Unfortunately, in 1858, they separated due to misunderstandings and resentment. After two years, he remarried Ellen Ternan, a young actress who remained his companion until his death.

Charles Dickens, a great Victorian figure, had enjoyed unprecedented fame during his lifetime. He was categorized as a literary genius of the 20 th century. Unfortunately, in 1865, while returning from Paris, he was involved in a fatal rail crash, which left him with bad health for several years. Despite this tragedy , he did not give up writing and kept on producing literary pieces until 1870 when he suffered a severe stroke and never regained consciousness. He died on the 9 th of June in 1870, leaving the book The Mystery of Edwin Drood, unfinished.

Some Important Facts of His Life

- He led a tough and painful childhood, which he chronicled in one of his masterpieces, David Copperfield.

- He had a great interest in paranormal and was an active member of the Ghost Club.

- The Oxford English Dictionary credits him for the first use of words, crossfire, dustbin, fairy story , whoosh, and slow-coach.

Charles Dickens tried his luck in various careers. At first, he worked at a boot-blackening factory when his father was imprisoned. Later, he became an office boy. However, in 1828, he became a stenographer and a freelance reporter in London. He began his literary career in 1833 when he started contributing a series of sketches and impressions to other magazines and newspapers using “Boz” as his pen-name. His serial publications, Oliver Twist and The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club brought him into the center of the literary world.

From 1836 to 1870, he made the reader’s jaws drop with his Christmas books, historical fiction novels , a travel guide, essays, and his observations about America . He spent time in Italy and America and reflected these cross -culture ramblings along with their impacts on people in his literary pieces, including Pictures from Italy. After his return from abroad, he published installments of Dombey and Son, which continued until 1948. Later, he produced many masterpieces, which are still read and admired, such as A Tale of Two Cities, Great Expectations, David Copperfield and Hard Times .

Charles Dickens, a great Victorian poet, opted for a very distant writing style and inspired the generation with his intellectual ideas. Since he started his literary career writing papers and essays for the magazines and newspapers, he successfully tried the same style in most of his stories. Using the cliff hanger technique, he was able to create suspense in his pieces. Marked with ideal characterization and satirical tone , Oliver Twist presents the mastery of his creative mind. In Christmas Carol, mysterious ghosts and music play a central role in blowing the triumph of Christmas. He has also involved realism , religion, and class in most of his novels to show the apparent truths about society. To exhibit the character traits, he has used literary devices such as personifications , imagery , similes , and metaphors . The recurring themes in most of his writings are fate and free will, religion, poverty , criminality, and identity.

Major Works

- Best Novels : He was an outstanding writer, some of his best novels include Great Expectations, A Tale of Two Cities, Our Mutual Friend, David Copperfield, Bleak House, and Oliver Twist.

- Other Works: Besides novels, he tried his hands on shorter fiction. Some of them include “A Christmas Tree”, “The Chimes: A Goblin Story”, “Going into Society” and “The Holly-Tree.”

Charles Dickens’s Impact on Future Literature

Two centuries have passed since Charles Dicken’s gave the world evergreen stories. Yet his stories, novels, and other pieces are taken various incarnations and have mesmerized generations after generations. His writings and literary ideas left a significant influence on many poets and writers, including John Irving, Jane Austen , Ann Rice, and Russian novelist, Fyodor Dostoevsky . To Fyodor, the Dickensian style reflects a mature understanding of morality, social resurrection, and spirituality.

Interestingly, the University of California founded the Dickens project as a part of the consortium of universities in the United States. They intended to study the literature and life of Charles Dickens. He successfully documented his ideas and feelings in his writings that even today, writers try to imitate his unique style, considering him a beacon for writing novels and shorter fiction.

Famous Quotes

- It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to, than I have ever known. (A Tale of Two Cities)

- Throughout life, our worst weaknesses and meannesses are usually committed for the sake of the people we most despise. (Great Expectations)

- Dignity, and even holiness too, sometimes, are more questions of coat and waistcoat than some people imagine. (Oliver Twist)

Related posts:

- Literary Writing Style of Charles Dickens

- Great Expectations Characters

- A Tale of Two Cities Characters

- A Tale of Two Cities Quotes

- A Tale of Two Cities Themes

- Great Expectations

Post navigation

(92) 336 3216666

Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens, aka Charles Dickens, was born on 7 th February 1812. He was English novelist, writer, and social critic. He is considered as the most celebrated novelist of the Victorian era. He has created some fictional characters that are regarded as the world’s best characters. His work was celebrated and received unparalleled popularity, both during his lifetime and even after his death. Critics and scholars, by the end of the 20 th century, acknowledged him as a literary genius. Even in the 21 st century, his works are widely read and included as a part of academic studies. He died on 9th June 1870.

Charles Dickens Biography

He was born at Landport, on the southern coast of England to John and Elizabeth Dickens. He was the second child among the eight poor siblings. His father, though supposed to be the original of Mr. Micawber, was a clerk in the office of the navy. Due to the poor financial conditions, his father was always struggling with debts. When Dickens was nine years old, they moved and settled in a poor neighborhood in London. Even in London, his father was still pursued by the debts, and after two years of bombastic misfortune, he was sent to the debtor’s prison. His mother set up the Boarding Establishment of Young Ladies to meet their finances. However, no young lady visited it except for creditors.

When Dickens was eleven years old, he was taken out of the school and put in work with the working-class men and boys in the blacking factory. At the age of twelve, while his father was still in prison, the rest of the family shifted to a place near the prison. Charles Dickens was left alone in London. It was these experiences of lonely hardships that proved to be very important in the literary career of Dickens. These experiences shaped his view of the world and thus described them in his famous and celebrated novels and short stories.

At the age of thirteen, Charles Dickens started his schooling again when his father received the inheritance and paid all his debts. However, at the age of fifteen, in 1827, he was again made to stop schooling and started working as an office boy. He then used his shorthand to write documents and became a stenographer and freelance reporter. In 1832, he became a news reporter for two newspapers in London. He then started publishing his sketches and impression in the other magazines with the sign of “Boz.” He published the images based on the life of London, which went far enough to make his reputation and were collectively published as his first book in 1836 as Sketches by Boz. He married Catherine Hogarth, daughter of George Hogarth, in April 1836. Soon after his marriage, he published his first most successful novel, The Pickwick Papers. Catherine and Charles Dickens had ten children together. In 1858, he became separated from Catherine. However, he continued his relationship with Ellen Tenan, his mistress and actress.

Literary Style of Charles Dickens

Dickens has been greatly inspired by a variety of things when he started writing. The major influences he has was the picaresque tradition in novel writing, novel of sensibility , and melodrama . Other than these, the fables of The Arabian Nights have been the most significant literary inspiration for him. In the picaresque novel tradition, satire and irony are the most important elements.

Similarly, in British picaresque novels, Henry Fielding, Laurence Sterne, and Tobias Smollett used the aspect of comedy as well. Tom Jones, by Henry Fielding, has not only influenced Charles Dickens but also the other novelist of the Victorian Era as well. Melodrama is also a great aspect of Dickens’ novels as it strongly appeals to the emotions of the readers.

The writing style of Charles Dickens is unique. His manner of writing is poetic , with a lot of satire and humor . Most of his novels and stories are episodic as his literary career started with working and writing for a newspaper. He is the master of using the element of suspense or cliffhanger ending to engage the readers, thus establishing their interest. Though Dickens’ literary works contain idealized characters , he does not make them appear perfect. Idealized characters appear to be a bad choice as it does not provide room for personal growth during the course of the story, however, uses his idealized characters to portray the horrible and ugly side of life and society. One of the best examples of idealized characters is Oliver Twist. Oliver is put in many trials, including a preparation center for thieves and malevolent orphanages during the course of the novel; however, he remains to be innocent and never compromising his values at all. Despite showing the ugly side of human society, Dickens creates the character of Oliver, an idealized character that the readers chose to love. Had Dickens not chosen to idealize the character, the book would have been gloomy and dark, with nothing to take pleasure in it.

Dickens’ works also contain unbelievable circumstances, thus adding the element of melodrama. For example, in the novel Oliver Twist , Oliver is rescued by a rich wealthy family from the gang thieves; the family then turns out to be his relatives. Authors or writers of the Victorian era would use such unbelievable circumstances to add a twist to the plot of the story. However, Dickens uses it in an entirely different way. The other writers would use it to extend their plot in their picaresque stories; Dickens used this method to portray the idea that good is always superior to evil, and even in unexpected cases, goodwill wins over evil.

The writing style of Charles Dickens is also marked by prolific linguistic creativity. He uses satire in his work to criticize the follies of society. His satire flourishes with his misrepresentation of situations. He has been compared to Hogarth for his use of satire and a real sense of the foolish and ridiculous side of life. He has the much-admired mastery of various classes of idioms, which reflects the traditions of the theatre of the Victorian era. To name his characters, Dickens worked arduously. He wanted his characters to appeal to the readers, and their names are suggestive of their personalities.

Moreover, he also wants these arresting names to contribute to the development of motifs in the plot, thereby providing an “allegorical impetus” to the overall meaning of the novel. One of the examples is the name of Mr. Murderstone from the novel David Copperfield. The name refers to two things: murder and coldness and harness as stone. Moreover, the literary cycle of Charles Dickens is also a blend of realism and fantasy. He satirizes the British aristocratic class and is very famous for it. To criticize the noble, he calls one of his characters, “the Noble Refrigerator.” In his literary works, he compares the orphans as shares and stocks of a business, people with tug boats, and party guests to furniture; these are some of his best examples of fancy.

Works Of Charles Dickens

- David Copperfield

- A Tale of Two Cities

Advertisement

Supported by

Being Charles Dickens

- Share full article

By David Gates

- Nov. 3, 2011

Robert DOUGLAS-FAIRHURST, the Oxford scholar who is one of Charles Dickens’s two new biographers, rightly calls his subject “at once the most central and most eccentric literary figure” of his age, and the investigations into the dark corners of that eccentric life began with Dickens himself. In 1849 he showed a short account of his early years to his close friend John Forster, revealing a story he never told his own family: the shame-inducing months he spent, while his father was in a debtor’s prison, as a 12-year-old “laboring hind” in a factory that bottled shoe-blacking. The first volume of the biography he’d wanted Forster to write — which made the blacking-factory episode public — appeared in 1872, two years after Dickens died at the age of 58, and its successors keep coming. The Dickens biographies published just in the past 25 years make an impressive stack. Given his uncanny genius and the vivid complexity of his life, that’s not a complaint.

Still, in all these books, the most memorable moments come from the accounts of those who saw him in person. I’d trade a whole pile of biographies for a video clip of the young Dickens, while courting Catherine Hogarth, his wife-to-be, leaping unannounced through the French windows of her family’s house in a sailor suit, dancing a hornpipe, leaping out again, then walking in at the door “as sedately as though quite innocent of the prank.” And I’d trade that clip, plus the biographies, for footage of Dickens’s face-to-face interview with his admirer Fyodor Dostoyevsky in 1862. “He told me,” Dostoyevsky recalled in a letter written years later, “that all the good, simple people in his novels . . . are what he wanted to have been, and his villains were what he was (or rather, what he found in himself), his cruelty, his attacks of causeless enmity towards those who were helpless and looked to him for comfort, his shrinking from those whom he ought to love. . . . There were two people in him, he told me: one who feels as he ought to feel and one who feels the opposite. From the one who feels the opposite I make my evil characters, from the one who feels as a man ought to feel, I try to live my life.”

Claire Tomalin, the other new biographer, who quotes this confession in “Charles Dickens: A Life,” calls it “amazing” — though it’s only amazing because it’s the image-conscious Dickens himself coming out and saying what anybody familiar with his work and his life has always intuited. “It is as though with Dostoyevsky he could drop the appearance of perfect virtue he felt he had to keep up before the English public.”

As Tomalin notes, this “must be Dickens’s most profound statement about his inner life,” and it seems to be one of the few crucial bits of Dickensiana that’s relatively fresh. Both Tomalin and Michael Slater, who cites the same passage in his 2009 biography, “Charles Dickens,” found the newly translated Dostoyevsky letter in a 2002 article in The Dickensian. Neither Fred Kaplan (“Dickens: A Biography,” 1988) nor Peter Ackroyd (“Dickens,” 1991) seems to have known about it. Mostly, the recent biographies are remixes of familiar episodes and anecdotes; their interest lies largely in what’s included and what’s left out, how deeply the biographer goes into unpublished or unfamiliar work, and what’s adduced from further research into the world in which Dickens lived and worked.

Neither Tomalin nor Douglas-Fairhurst, in “Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist,” sees fit to show us Dickens dancing the hornpipe in his sailor suit, though Ackroyd and Slater apparently found it a charming, perhaps significant, glimpse of the young man at play. And how could Tomalin have resisted the story of Dickens’s first love, Maria Beadnell (affectionately evoked as Dora in “David Copperfield,” then cruelly caricatured as Flora Finching in “Little Dorrit”), near the end of her life, drunkenly kissing the place on her couch where he’d once sat? Maria’s former nursemaid published the account in 1912; Douglas-Fairhurst retells it, and while Slater didn’t include it in his biography, he’d already used it in an earlier book, “Dickens and Women.” Yet only an obsessive would worry too much about which anecdote didn’t make whose cut: an ideal life of Dickens would just stick in everything, and probably no publisher would touch it.

After Tomalin’s much-praised biographies of Jane Austen, Thomas Hardy and Samuel Pepys, it’s no surprise to find her portrait of Dickens at least as thorough as Kaplan’s or Slater’s, though she gives us no introduction explaining why previous biographies have made hers necessary, and sometimes teases us with flat summary where we want meat. (If, for instance, “the critics were merciless” about his 1846 Christmas book, “The Battle of Life,” why not quote them?) Her book lacks the rich texture and empathetic intimacy of Ackroyd’s far longer work. On the other hand, Tomalin would never indulge in zaniness like Ackroyd’s interpolated self-interview or his scene in which Dickens meets his own characters or the imagined encounter between Dickens and a biographer, presumably Ackroyd himself. And Tomalin’s treatment of the great secret of Dickens’s life — his relationship with the actress Ellen Ternan, for whom he left his marriage in 1858, when he was 46 and she was 19 — seems more credible, even when it’s necessarily speculative. In 1990 she devoted an entire book, “The Invisible Woman,” to exploring this secret — whose existence Dickensians have known about at least since the 1930s.

Despite Dickens’s discreet, intermittent cohabitation with Ternan, Ackroyd found it “almost inconceivable” that the two actually went to bed together: he argued that their idyll was merely “the realization of one of his most enduring fictional fantasies. That of sexless marriage with a young, idealized virgin.” Few other scholars agree — not even Edgar Johnson, whose two-volume “Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph,” published in 1952, was the first major modern biography. As Tomalin notes, Dickens was a sexual creature: he fathered 10 children with his wife, and after they separated he apparently sought treatment for a venereal infection. Had he been such a prude as his fiction and his public persona sometimes suggested — after news of his separation got around, Forster had to talk him out of calling a new start-up magazine Household Harmony — he would hardly have remained close friends with sophisticated sexual outlaws like the artists Frank Stone and Daniel Maclise, the novelist Wilkie Collins and the Count d’Orsay, the French dandy whom he made godfather to his son Alfred. Hearsay and circumstantial evidence even suggest that Ternan might have borne Dickens a son, who died within a year.