Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that he or she will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove her point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, he or she still has to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and she already knows everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality she or he expects.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

The Center for Teaching Writing

At the university of oregon.

Designing Effective Writing Assignments

Before designing any assignment, it is necessary to first assess the course objectives and what is the best way to meet those objectives. There are several important aspects to consider when creating assignments:

- Teacher’s assignment goals

- The writer’s purpose

- The context of the assignment

- The audience of the assignment

- Format and method

- Teacher’s response and evaluation

- Opportunities for revision

- Communicating expectations

Teacher’s assignment goals: To make a successful assignment, you must first be clear about what the assignment should accomplish. You may want to use some assignments to generate discussion in class or to give students the opportunity to present their ideas in class. Other goals are to give students the opportunity to express questions and confusion; to demonstrate understanding of course concepts and information; to respond to class readings and discussion; to prepare for other assignments or exams; or to clarify ideas for themselves.

There are two main kinds of writing assignments for content courses :

Writing to Learn assignments are usually short, informal assignments. The audience for such assignments can be the student herself, peers, or the teacher. These assignments can be in-class writing, or out of class writing. The primary purpose of writing to learn assignments is for students to grasp the ideas and concepts presented in the course for themselves.

Other writing assignments are used primarily to demonstrate knowledge . The audience for these assignments is most often the teacher. These are formal assignments written for a grade.

These two types of assignments are not mutually exclusive. An assignment can both aid students in the learning process and demonstrate a student’s knowledge and understanding. However, it is important to determine the primary purpose the assignment must serve in order to decide what kind of writing to assign.

Other things to think about in terms of your goals for the assignment: What part does this assignment play in the rest of the course? Is this assignment part of a sequence of assignments that includes both formal and informal writing? Sequenced assignments are helpful in incorporating informal writing to learn assignments with formal demonstrative assignments. For example, thesis writing, reading responses, and short microthemes or abstracts can lead to a formal essay or term paper.

The writer’s purpose: The writer’s purpose dictates what kind of product the students will end up with. There are a number of different purposes for assignments to fulfill; the purpose dictates the form and content of an assignment. For example, students might be asked to articulate questions they have about course content; compose an article explaining course concepts to peers; respond to course reading or discussion; or argue a position on an issue related to the field of study. Whatever the writer’s purpose, it will determine the context, audience, and format of the assignment as well.

The context of the assignment: Will this be an in-class or out-of-class assignment? Some assignments take place in the field of research. Will the students be working alone, or in groups or pairs? To what is the student responding – one or more readings, discussion, research? Will you assign a particular issue or allow students to identify the issues themselves? Part of determining context is deciding the audience the students are to address.

The audience of the assignment: The implied audience may be the same as or different from the real audience. Both the implied and real audiences influence the shape of the assignment. To whom are the students directing their writing? The implied audience can be the teacher, peers, scholars in the field, or the general public who is unfamiliar with the concepts of the discipline. Specifying the implied audience will help students determine what common ground is available in the form of shared assumptions or theoretical perspectives. Also important is the real audience. Who is actually going to read this assignment? The student only? The teacher only? Peers only? A small group of peers? The teacher and peers? Will there be multiple drafts? Will the student get comments from you or from peers before the final product is graded?

Format and method: What should the completed assignment look like? Is there a particular way students should go about fulfilling the assignment? Is there a particular field protocol? Are students expected to use research?

Teacher’s response and evaluation: Some writing to learn assignments are not graded or receive nontraditional grades. How will this assignment help fulfill course objectives, and how much of the course grade should be determined by this assignment? Will students get your comments before the final grade or after? What should students learn from your comments?

Opportunities for revision: Another important aspect to designing an assignment is deciding whether and how to incorporate revision. There are several ways to allow students to revise their work:

- Allowing students to revise after an assignment is graded for the possibility of raising their grade.

- Assigning multiple drafts as part of the final grade. Such an assignment would be graded as a process-based on how the student challenged her own ideas-rather than as a product. The student would receive either teacher comments, peer comments, or both on early drafts that will guide them in revision.

- Using peer evaluations on early drafts. Reading and commenting on fellow students’ work helps students learn to read critically and be responsible members of the discourse community of the classroom and of the field. If you are using peer response, what is the format? Students can respond to the writing of their peers in writing or orally, in groups or one-on-one. Will you provide detailed instructions and specific protocols for responding to student writing or allow them to develop their own format?

Communicating your expectations: Once you have determined the assignment objectives and how best to meet those objectives, you should give your assignment in writing to the students. Have you designed the assignment so that the students understand your goals and their purpose? Are the terms clear? Have you specified the audience, context, format, and means of evaluation? It is often helpful to get feedback on your assignments from colleagues who can tell you whether or not your expectations are totally clear.

One thought on “ Designing Effective Writing Assignments ”

This is an amazing type of post. Safe

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Northern Illinois University Effective Writing Practices Tutorial

- Make a Gift

- MyScholarships

- Huskie Link

- Anywhere Apps

- Huskies Get Hired

- Student Email

- Password Self-Service

- Quick Links

- Effective Writing Practices Tutorial

- Organization

- Reading the Assignment

Assignment Considerations

Always read your written assignment carefully and consider what it asks you to do. Here are some questions that you may ask yourself before you begin to write your assignment:

- What kind of a written assignment is it ( an essay , a research paper , or a report )?

- Who is your primary audience for this assignment?

- What is the purpose of the assignment (to inform, to influence, or to record)?

- What mode of communication would best fit the assignment (a narrative, a description, a comparison, or an argument)?

- How long should the paper be?

- Does the assignment have any specific format requirements?

- What style of documentation is required?

- Are you required to do any research for this assignment?

- If research is required, how many sources should be used?

Rule to Remember

Always read your written assignment carefully and consider what it asks you to do.

If you cannot answer all of these questions by reading the assignment description, go back to your professor to clarify the requirements.

What kind of an assignment are you asked to write?

The most common written assignments given to students are essays, research papers, and reports.

An essay is defined as "an analytic or interpretative literary composition usually dealing with its subject from a limited or personal point of view" ( Merriam Webster OnLine ). Essays usually express the author's outlook on the subject.

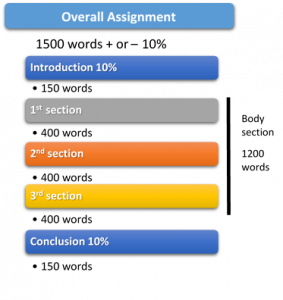

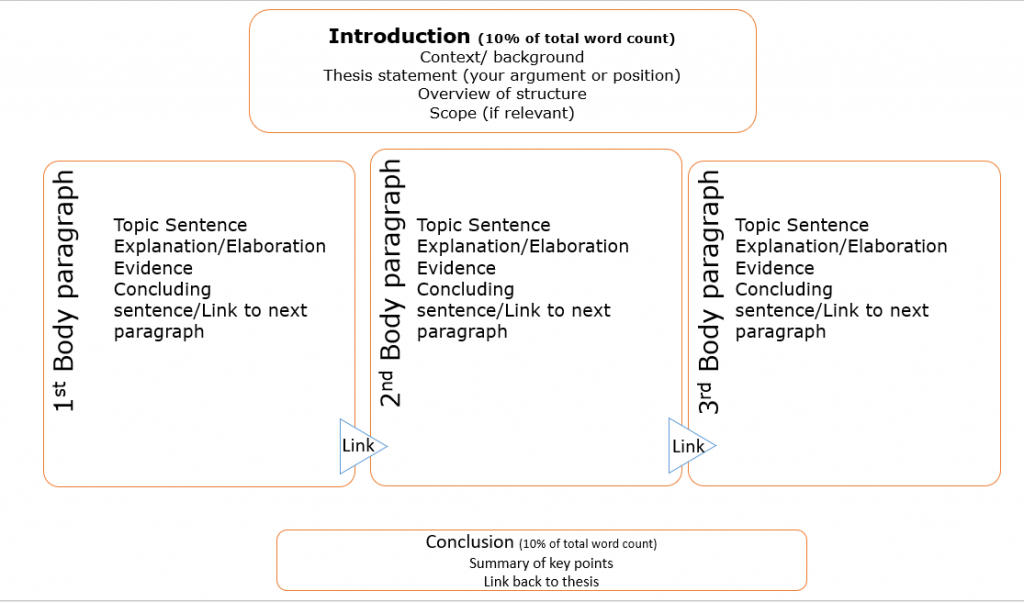

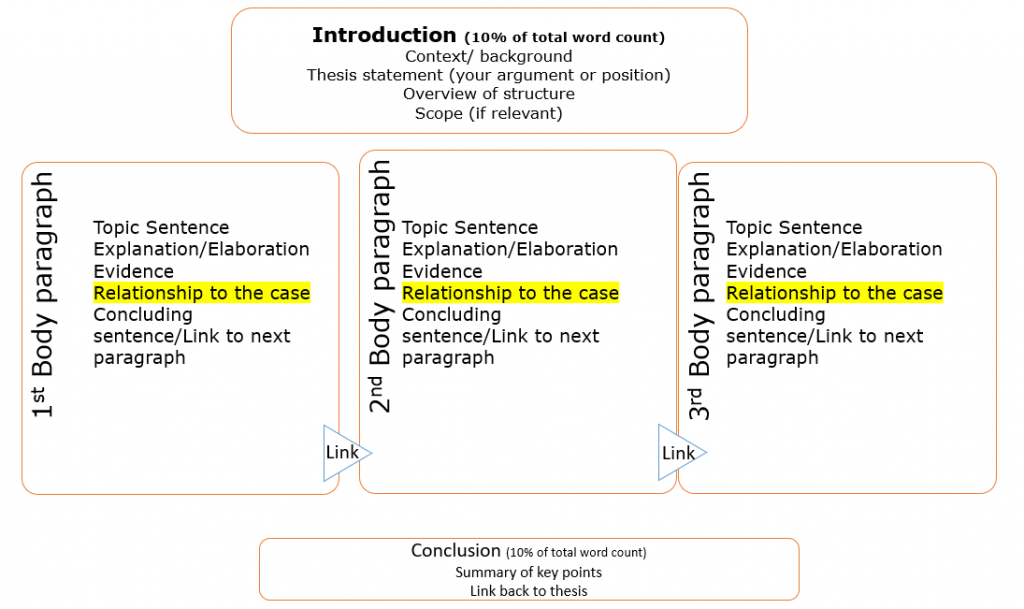

A useful model that is often used in composition classes is a five-paragraph essay .

The Structure of a Classic Five-Paragraph Essay:

- Introduction (presents a topic and provides a thesis statement)

- Body paragraph 1 (presents evidence and supporting information)

- Body paragraph 2 (presents evidence and supporting information)

- Body paragraph 3 (presents evidence and supporting information)

- Conclusion (restatement of the thesis, call to action)

An essay is "an analytic or interpretive literary composition usually dealing with its subject from a limited or personal point of view."

NIU Writing Center Handout on a Classic Five-Paragraph Essay (PDF)

A Research Paper

A research paper is a term harder to define because expectations and guidelines may vary depending on your area of study. A research paper usually requires gathering research materials, interpreting, and documenting them in the paper. It is based the author's interpretation of the facts gathered from research and it, therefore, requires good critical thinking skills on the part of the author.

A research paper needs to be logically organized with a clearly stated purpose and thesis which have to be supported throughout the main body of the paper. Research information can be presented in the form of quotations, paraphrases, or summaries.

A research paper needs to be logically organized with a clearly stated purpose and thesis which are supported throughout the main body of the paper.

A research paper usually has the following structure

- Abstract (a brief summary of the paper)

- Introduction (introduces the importance of the subject)

- Materials and Methods (discusses how research was conducted)

- Results (describes outcomes of the research process)

- Discussion (discusses the relationship of the results)

- References (provides a list of resources used)

- Appendix (provides material used in research but not presented in the body of the paper)

( Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 10-29)

While essays and research papers are more typical in the humanities, much writing in the sciences and social sciences is in the form of a report. A report presents factual information, and its main purpose is to inform. It contains examples and provides an analysis of the subject.

The structure and organization of a report should reflect its main purpose and audience. There are several possible organization patterns. Below are two of the most common ones:

Report Structure One

- Abstract (summary of the report in one concise paragraph)

- Introduction (a brief outline of the problem)

- Literature review (summary of research in the field)

- Research methods

- Research results

- Discussion and conclusion (here the author may include an evaluation and form an argument)

- Endmatter (notes, references, appendices)

(Hult & Huckin, The New Century Handbook , 378)

A report presents factual information, and its main purpose is to inform. It contains examples and provides an analysis of the subject.

Report Structure Two

- Contents list

- Executive summary (brief outline of the subject matter)

- Introduction (presents background, scope, and authors)

- Body of the report (detailed account of the subject)

- Conclusions

- Recommendations (not all reports may have them)

- Appendices (may include research methods, names of members of the report team, case studies)

- Bibliography

(Sealy, Oxford Guide to Effective Writing and Speaking , 70)

- Punctuation

- Addressing the Audience

- Introduction

- Thesis Statement

- Supporting Paragraphs

- Transitions

- Revision Process

Teaching, Learning, & Professional Development Center

- Teaching Resources

- TLPDC Teaching Resources

How Do I Create Meaningful and Effective Assignments?

Prepared by allison boye, ph.d. teaching, learning, and professional development center.

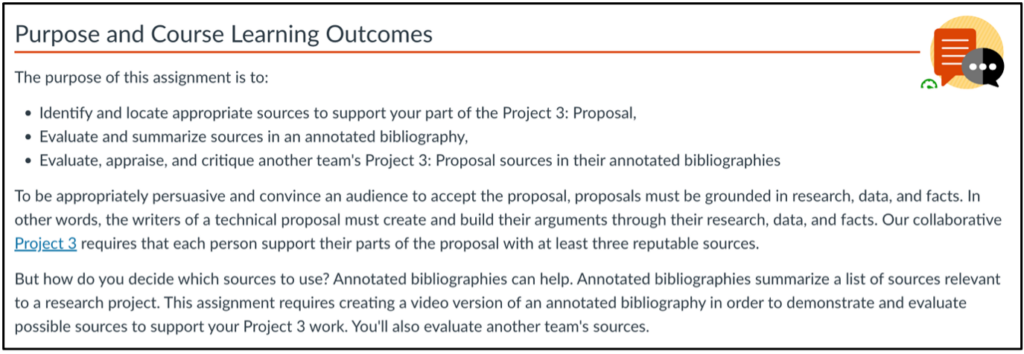

Assessment is a necessary part of the teaching and learning process, helping us measure whether our students have really learned what we want them to learn. While exams and quizzes are certainly favorite and useful methods of assessment, out of class assignments (written or otherwise) can offer similar insights into our students' learning. And just as creating a reliable test takes thoughtfulness and skill, so does creating meaningful and effective assignments. Undoubtedly, many instructors have been on the receiving end of disappointing student work, left wondering what went wrong… and often, those problems can be remedied in the future by some simple fine-tuning of the original assignment. This paper will take a look at some important elements to consider when developing assignments, and offer some easy approaches to creating a valuable assessment experience for all involved.

First Things First…

Before assigning any major tasks to students, it is imperative that you first define a few things for yourself as the instructor:

- Your goals for the assignment . Why are you assigning this project, and what do you hope your students will gain from completing it? What knowledge, skills, and abilities do you aim to measure with this assignment? Creating assignments is a major part of overall course design, and every project you assign should clearly align with your goals for the course in general. For instance, if you want your students to demonstrate critical thinking, perhaps asking them to simply summarize an article is not the best match for that goal; a more appropriate option might be to ask for an analysis of a controversial issue in the discipline. Ultimately, the connection between the assignment and its purpose should be clear to both you and your students to ensure that it is fulfilling the desired goals and doesn't seem like “busy work.” For some ideas about what kinds of assignments match certain learning goals, take a look at this page from DePaul University's Teaching Commons.

- Have they experienced “socialization” in the culture of your discipline (Flaxman, 2005)? Are they familiar with any conventions you might want them to know? In other words, do they know the “language” of your discipline, generally accepted style guidelines, or research protocols?

- Do they know how to conduct research? Do they know the proper style format, documentation style, acceptable resources, etc.? Do they know how to use the library (Fitzpatrick, 1989) or evaluate resources?

- What kinds of writing or work have they previously engaged in? For instance, have they completed long, formal writing assignments or research projects before? Have they ever engaged in analysis, reflection, or argumentation? Have they completed group assignments before? Do they know how to write a literature review or scientific report?

In his book Engaging Ideas (1996), John Bean provides a great list of questions to help instructors focus on their main teaching goals when creating an assignment (p.78):

1. What are the main units/modules in my course?

2. What are my main learning objectives for each module and for the course?

3. What thinking skills am I trying to develop within each unit and throughout the course?

4. What are the most difficult aspects of my course for students?

5. If I could change my students' study habits, what would I most like to change?

6. What difference do I want my course to make in my students' lives?

What your students need to know

Once you have determined your own goals for the assignment and the levels of your students, you can begin creating your assignment. However, when introducing your assignment to your students, there are several things you will need to clearly outline for them in order to ensure the most successful assignments possible.

- First, you will need to articulate the purpose of the assignment . Even though you know why the assignment is important and what it is meant to accomplish, you cannot assume that your students will intuit that purpose. Your students will appreciate an understanding of how the assignment fits into the larger goals of the course and what they will learn from the process (Hass & Osborn, 2007). Being transparent with your students and explaining why you are asking them to complete a given assignment can ultimately help motivate them to complete the assignment more thoughtfully.

- If you are asking your students to complete a writing assignment, you should define for them the “rhetorical or cognitive mode/s” you want them to employ in their writing (Flaxman, 2005). In other words, use precise verbs that communicate whether you are asking them to analyze, argue, describe, inform, etc. (Verbs like “explore” or “comment on” can be too vague and cause confusion.) Provide them with a specific task to complete, such as a problem to solve, a question to answer, or an argument to support. For those who want assignments to lead to top-down, thesis-driven writing, John Bean (1996) suggests presenting a proposition that students must defend or refute, or a problem that demands a thesis answer.

- It is also a good idea to define the audience you want your students to address with their assignment, if possible – especially with writing assignments. Otherwise, students will address only the instructor, often assuming little requires explanation or development (Hedengren, 2004; MIT, 1999). Further, asking students to address the instructor, who typically knows more about the topic than the student, places the student in an unnatural rhetorical position. Instead, you might consider asking your students to prepare their assignments for alternative audiences such as other students who missed last week's classes, a group that opposes their position, or people reading a popular magazine or newspaper. In fact, a study by Bean (1996) indicated the students often appreciate and enjoy assignments that vary elements such as audience or rhetorical context, so don't be afraid to get creative!

- Obviously, you will also need to articulate clearly the logistics or “business aspects” of the assignment . In other words, be explicit with your students about required elements such as the format, length, documentation style, writing style (formal or informal?), and deadlines. One caveat, however: do not allow the logistics of the paper take precedence over the content in your assignment description; if you spend all of your time describing these things, students might suspect that is all you care about in their execution of the assignment.

- Finally, you should clarify your evaluation criteria for the assignment. What elements of content are most important? Will you grade holistically or weight features separately? How much weight will be given to individual elements, etc? Another precaution to take when defining requirements for your students is to take care that your instructions and rubric also do not overshadow the content; prescribing too rigidly each element of an assignment can limit students' freedom to explore and discover. According to Beth Finch Hedengren, “A good assignment provides the purpose and guidelines… without dictating exactly what to say” (2004, p. 27). If you decide to utilize a grading rubric, be sure to provide that to the students along with the assignment description, prior to their completion of the assignment.

A great way to get students engaged with an assignment and build buy-in is to encourage their collaboration on its design and/or on the grading criteria (Hudd, 2003). In his article “Conducting Writing Assignments,” Richard Leahy (2002) offers a few ideas for building in said collaboration:

• Ask the students to develop the grading scale themselves from scratch, starting with choosing the categories.

• Set the grading categories yourself, but ask the students to help write the descriptions.

• Draft the complete grading scale yourself, then give it to your students for review and suggestions.

A Few Do's and Don'ts…

Determining your goals for the assignment and its essential logistics is a good start to creating an effective assignment. However, there are a few more simple factors to consider in your final design. First, here are a few things you should do :

- Do provide detail in your assignment description . Research has shown that students frequently prefer some guiding constraints when completing assignments (Bean, 1996), and that more detail (within reason) can lead to more successful student responses. One idea is to provide students with physical assignment handouts , in addition to or instead of a simple description in a syllabus. This can meet the needs of concrete learners and give them something tangible to refer to. Likewise, it is often beneficial to make explicit for students the process or steps necessary to complete an assignment, given that students – especially younger ones – might need guidance in planning and time management (MIT, 1999).

- Do use open-ended questions. The most effective and challenging assignments focus on questions that lead students to thinking and explaining, rather than simple yes or no answers, whether explicitly part of the assignment description or in the brainstorming heuristics (Gardner, 2005).

- Do direct students to appropriate available resources . Giving students pointers about other venues for assistance can help them get started on the right track independently. These kinds of suggestions might include information about campus resources such as the University Writing Center or discipline-specific librarians, suggesting specific journals or books, or even sections of their textbook, or providing them with lists of research ideas or links to acceptable websites.

- Do consider providing models – both successful and unsuccessful models (Miller, 2007). These models could be provided by past students, or models you have created yourself. You could even ask students to evaluate the models themselves using the determined evaluation criteria, helping them to visualize the final product, think critically about how to complete the assignment, and ideally, recognize success in their own work.

- Do consider including a way for students to make the assignment their own. In their study, Hass and Osborn (2007) confirmed the importance of personal engagement for students when completing an assignment. Indeed, students will be more engaged in an assignment if it is personally meaningful, practical, or purposeful beyond the classroom. You might think of ways to encourage students to tap into their own experiences or curiosities, to solve or explore a real problem, or connect to the larger community. Offering variety in assignment selection can also help students feel more individualized, creative, and in control.

- If your assignment is substantial or long, do consider sequencing it. Far too often, assignments are given as one-shot final products that receive grades at the end of the semester, eternally abandoned by the student. By sequencing a large assignment, or essentially breaking it down into a systematic approach consisting of interconnected smaller elements (such as a project proposal, an annotated bibliography, or a rough draft, or a series of mini-assignments related to the longer assignment), you can encourage thoughtfulness, complexity, and thoroughness in your students, as well as emphasize process over final product.

Next are a few elements to avoid in your assignments:

- Do not ask too many questions in your assignment. In an effort to challenge students, instructors often err in the other direction, asking more questions than students can reasonably address in a single assignment without losing focus. Offering an overly specific “checklist” prompt often leads to externally organized papers, in which inexperienced students “slavishly follow the checklist instead of integrating their ideas into more organically-discovered structure” (Flaxman, 2005).

- Do not expect or suggest that there is an “ideal” response to the assignment. A common error for instructors is to dictate content of an assignment too rigidly, or to imply that there is a single correct response or a specific conclusion to reach, either explicitly or implicitly (Flaxman, 2005). Undoubtedly, students do not appreciate feeling as if they must read an instructor's mind to complete an assignment successfully, or that their own ideas have nowhere to go, and can lose motivation as a result. Similarly, avoid assignments that simply ask for regurgitation (Miller, 2007). Again, the best assignments invite students to engage in critical thinking, not just reproduce lectures or readings.

- Do not provide vague or confusing commands . Do students know what you mean when they are asked to “examine” or “discuss” a topic? Return to what you determined about your students' experiences and levels to help you decide what directions will make the most sense to them and what will require more explanation or guidance, and avoid verbiage that might confound them.

- Do not impose impossible time restraints or require the use of insufficient resources for completion of the assignment. For instance, if you are asking all of your students to use the same resource, ensure that there are enough copies available for all students to access – or at least put one copy on reserve in the library. Likewise, make sure that you are providing your students with ample time to locate resources and effectively complete the assignment (Fitzpatrick, 1989).

The assignments we give to students don't simply have to be research papers or reports. There are many options for effective yet creative ways to assess your students' learning! Here are just a few:

Journals, Posters, Portfolios, Letters, Brochures, Management plans, Editorials, Instruction Manuals, Imitations of a text, Case studies, Debates, News release, Dialogues, Videos, Collages, Plays, Power Point presentations

Ultimately, the success of student responses to an assignment often rests on the instructor's deliberate design of the assignment. By being purposeful and thoughtful from the beginning, you can ensure that your assignments will not only serve as effective assessment methods, but also engage and delight your students. If you would like further help in constructing or revising an assignment, the Teaching, Learning, and Professional Development Center is glad to offer individual consultations. In addition, look into some of the resources provided below.

Online Resources

“Creating Effective Assignments” http://www.unh.edu/teaching-excellence/resources/Assignments.htm This site, from the University of New Hampshire's Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning, provides a brief overview of effective assignment design, with a focus on determining and communicating goals and expectations.

Gardner, T. (2005, June 12). Ten Tips for Designing Writing Assignments. Traci's Lists of Ten. http://www.tengrrl.com/tens/034.shtml This is a brief yet useful list of tips for assignment design, prepared by a writing teacher and curriculum developer for the National Council of Teachers of English . The website will also link you to several other lists of “ten tips” related to literacy pedagogy.

“How to Create Effective Assignments for College Students.” http:// tilt.colostate.edu/retreat/2011/zimmerman.pdf This PDF is a simplified bulleted list, prepared by Dr. Toni Zimmerman from Colorado State University, offering some helpful ideas for coming up with creative assignments.

“Learner-Centered Assessment” http://cte.uwaterloo.ca/teaching_resources/tips/learner_centered_assessment.html From the Centre for Teaching Excellence at the University of Waterloo, this is a short list of suggestions for the process of designing an assessment with your students' interests in mind. “Matching Learning Goals to Assignment Types.” http://teachingcommons.depaul.edu/How_to/design_assignments/assignments_learning_goals.html This is a great page from DePaul University's Teaching Commons, providing a chart that helps instructors match assignments with learning goals.

Additional References Bean, J.C. (1996). Engaging ideas: The professor's guide to integrating writing, critical thinking, and active learning in the classroom . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fitzpatrick, R. (1989). Research and writing assignments that reduce fear lead to better papers and more confident students. Writing Across the Curriculum , 3.2, pp. 15 – 24.

Flaxman, R. (2005). Creating meaningful writing assignments. The Teaching Exchange . Retrieved Jan. 9, 2008 from http://www.brown.edu/Administration/Sheridan_Center/pubs/teachingExchange/jan2005/01_flaxman.pdf

Hass, M. & Osborn, J. (2007, August 13). An emic view of student writing and the writing process. Across the Disciplines, 4.

Hedengren, B.F. (2004). A TA's guide to teaching writing in all disciplines . Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's.

Hudd, S. S. (2003, April). Syllabus under construction: Involving students in the creation of class assignments. Teaching Sociology , 31, pp. 195 – 202.

Leahy, R. (2002). Conducting writing assignments. College Teaching , 50.2, pp. 50 – 54.

Miller, H. (2007). Designing effective writing assignments. Teaching with writing . University of Minnesota Center for Writing. Retrieved Jan. 9, 2008, from http://writing.umn.edu/tww/assignments/designing.html

MIT Online Writing and Communication Center (1999). Creating Writing Assignments. Retrieved January 9, 2008 from http://web.mit.edu/writing/Faculty/createeffective.html .

Contact TTU

NCI LIBRARY

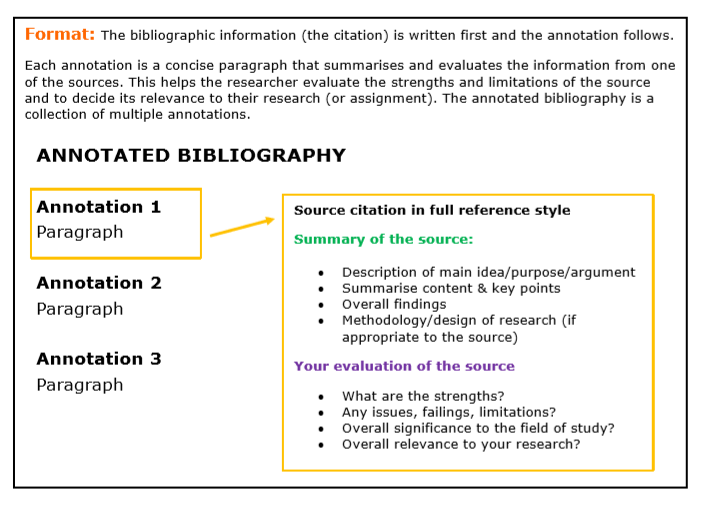

Academic writing skills guide: understanding assignments.

- Key Features of Academic Writing

- The Writing Process

- Understanding Assignments

- Brainstorming Techniques

- Planning Your Assignments

- Thesis Statements

- Writing Drafts

- Structuring Your Assignment

- How to Deal With Writer's Block

- Using Paragraphs

- Conclusions

- Introductions

- Revising & Editing

- Proofreading

- Grammar & Punctuation

- Reporting Verbs

- Signposting, Transitions & Linking Words/Phrases

- Using Lecturers' Feedback

Below is a list of interpretations for some of the more common directive/instructional words. These interpretations are intended as a guide only but should help you gain a better understanding of what is required when they are used.

Communications from the Library: Please note all communications from the library, concerning renewal of books, overdue books and reservations will be sent to your NCI student email account.

- << Previous: The Writing Process

- Next: Brainstorming Techniques >>

- Last Updated: Dec 15, 2023 10:00 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ncirl.ie/academic_writing_skills

Understanding the Assignment

There are four kinds of analysis you need to do in order to fully understand an assignment: determining the purpose of the assignment , understanding how to answer an assignment’s questions , recognizing implied questions in the assignment , and recognizing the disciplinary expectations of the assignment .

Always make sure you fully understand an assignment before you start writing!

Determining the Purpose

The wording of an assignment should suggest its purpose. Any of the following might be expected of you in a college writing assignment:

- Summarizing information

- Analyzing ideas and concepts

- Taking a position and defending it

- Combining ideas from several sources and creating your own original argument.

Understanding How to Answer the Assignment

College writing assignments will ask you to answer a how or why question – questions that can’t be answered with just facts. For example, the question “ What are the names of the presidents of the US in the last twenty years?” needs only a list of facts to be answered. The question “ Who was the best president of the last twenty years and why?” requires you to take a position and support that position with evidence.

Sometimes, a list of prompts may appear with an assignment. Remember, your instructor will not expect you to answer all of the questions listed. They are simply offering you some ideas so that you can think of your own questions to ask.

Recognizing Implied Questions

A prompt may not include a clear ‘how’ or ‘why’ question, though one is always implied by the language of the prompt. For example:

“Discuss the effects of the No Child Left Behind Act on special education programs” is asking you to write how the act has affected special education programs. “Consider the recent rise of autism diagnoses” is asking you to write why the diagnoses of autism are on the rise.

Recognizing Disciplinary Expectations

Depending on the discipline in which you are writing, different features and formats of your writing may be expected. Always look closely at key terms and vocabulary in the writing assignment, and be sure to note what type of evidence and citations style your instructor expects.

About Writing: A Guide Copyright © 2015 by Robin Jeffrey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 2: Understanding Assignment Outlines and Instructions

Understanding assignment outlines and instructions, writing for whom writing for what.

The first principle of good communication is knowing your audience . Often when you write for an audience of one, you might write a text or email. But college papers aren’t written like emails; they’re written like articles for a hypothetical group of readers that you don’t actually know much about. There’s a fundamental mismatch between the real-life audience and the form your writing takes.

Unless there is a particular audience specified in the assignment, you would do well to imagine yourself writing for a group of peers who have some introductory knowledge of the field but are unfamiliar with the specific topic you’re discussing. Imagine them being interested in your topic but also busy; try to write something that is well worth your readers’ time. Keeping an audience like this in mind will help you distinguish common knowledge in the field from that which must be defined and explained in your paper.

Another basic tenet of good communication is clarifying the purpose of the communication and letting that purpose shape your decisions. Your professor wants to see you work through complex ideas and demonstrate your learning through the process of producing the paper. Each assignment—be it an argumentative paper, reaction paper, reflective paper, lab report, discussion question, blog post, essay exam, project proposal, or what have you—is ultimately about your learning. To succeed with writing assignments (and benefit from them) you first have to understand their learning-related purposes. As you write for your audience, you’re demonstrating to your professor how far you’ve gotten in analyzing your topic.

Professors don’t assign writing lightly. Grading student writing is generally the hardest, most intensive work instructors do. You would do well to approach every assignment by putting yourself in the shoes of your instructor and asking yourself, “Why did she give me this assignment? How does it fit into the learning goals of the course? Why is this question/topic/problem so important to my professor that he is willing to spend time reading and commenting on several dozen papers on it?”

Professors certainly vary in the quantity and specificity of the guidelines and suggestions they distribute with each writing assignment. Some professors make a point to give very few parameters about an assignment—perhaps just a topic and a length requirement—and they likely have some good reasons for doing so. Here are some possible reasons:

- They figured it out themselves when they were students . Many instructors will teach how they were taught in school. The emphasis on student-centered instruction is relatively recent; your instructors more often had professors who adhered to the classic model of college instruction: they went to lectures and/or labs and wrote papers. Students were often ‘on their own’ to learn the lingo and conventions of each field, to identify the key concepts and ideas within readings and lectures, and to sleuth out instructors’ expectations for written work. Learning goals, rubrics, quizzes, and preparatory assignments were generally rare.

- They think figuring it out yourself is good for you . Because your professors often succeeded in a much less supportive environment , they appreciate how learning to thrive in those conditions gave them life-long problem-solving and critical thinking skills. Many think you should be able to figure it out yourself and that it would be good practice for you to do so. Even those who do include a lot of guidance with writing assignments sometimes worry that they’re depriving you of an important personal and intellectual challenge. Figuring out unspoken expectations is a valuable skill in itself. They may also want to give you the freedom to explore and produce new and interesting ideas and feel that instructions that are too specific may limit you. There’s a balancing act to creating a good assignment outline, so sometimes you might need to ask for clarification.

- They think you already know the skills/concepts : Some professors assume that students come with a fully developed set of academic skills and knowledge. You may need to ask your professor for clarification or help and it’s good to learn what additional resources are out there to assist you (the Library, Writing Guides, etc).

It is understandably frustrating when you feel you don’t know how to direct your efforts to succeed with an assignment. The transparency that you get from some professors—along with books like this one—will be a big help to you in situations where you have to be scrappier and more pro-active, piecing together the clues you get from your professors, the readings, and other course documents.

The assignment prompt: what does “analyze” mean anyway?

Often, the handout or other written text explaining the assignment—what professors call the assignment prompt or outline—will explain the purpose of the assignment, the required parameters (length, number and type of sources, referencing style, etc.), and the criteria for evaluation.

Sometimes, though—especially when you are new to a field—you will encounter the baffling situation in which you comprehend every single sentence in the prompt but still have absolutely no idea how to approach the assignment. No one is doing anything wrong in a situation like that. It just means that further discussion of the assignment is in order. Here are some tips:

Video source: https://youtu.be/JZ175MLpOmE

- Try to brainstorm or do a free-write . A free-write is when you just write, without stopping, for a set period of time. That doesn’t sound very “free;” it actually sounds kind of coerced. The “free” part is what you write—it can be whatever comes to mind. Professional writers use free-writing to get started on a challenging (or distasteful) writing task or to overcome writers block or a powerful urge to procrastinate. The idea is that if you just make yourself write, you can’t help but produce some kind of useful nugget. Thus, even if the first eight sentences of your free write are all variations on “I don’t understand this” or “I’d really rather be doing something else,” eventually you’ll write something like “I guess the main point of this is …” and—booyah!—you’re off and running. If your instructor doesn’t make time for that in class, a quick free-write on your own will quickly reveal whether you need clarification about the assignment and, often, what questions to ask.

Rubrics as road maps

Not all professors use rubrics : some mark “holistically” (which means that they evaluate the paper as a whole), versus “analytically” (where they break down the marks by criteria). If the professor took the trouble to prepare and distribute a rubric, you can be sure that they will use it to grade your paper. A rubric is the clearest possible statement of what the professor is looking for in the paper. If it’s wordy, it may seem like those online “terms and conditions” that we routinely accept without reading. But you really should read it over carefully before you begin and again as your work progresses. A lot of rubrics do have some useful specifics. Even less specific criteria (such as “incorporates course concepts” and “considers counter-arguments”) will tell you how you should be spending your writing time.

Even the best rubrics aren’t completely transparent because they simply can’t be. For example, what is the real difference between “demonstrating a thorough understanding of context, audience, and purpose” and “demonstrating adequate consideration” of the same? It depends on the specific context. So how can you know whether you’ve done that? A big part of what you’re learning, through feedback from your professors, is to judge the quality of your writing for yourself. Your future employers are counting on that. At this point, it is better to think of rubrics as roadmaps, displaying your destination, rather than a GPS system directing every move you make.

Video source: https://youtu.be/mXRzyZAE8Y4

What’s critical about critical thinking?

Critical thinking is one of those terms that has been used so often and in so many different ways that if often seems meaningless. It also makes one wonder, is there such a thing as uncritical thinking? If you aren’t thinking critically, then are you even thinking?

Despite the prevalent ambiguities, critical thinking actually does mean something. The Association of American Colleges and Universities usefully defines it as “a habit of mind characterized by the comprehensive exploration of issues, ideas, artifacts, and events before accepting or formulating an opinion or conclusion.” [1]

The critical thinking rubric produced by the AAC&U describes the relevant activities of critical thinking in more detail. To think critically, one must …

(a) “clearly state and comprehensively describe the issue or problem”,

(b) “independently interpret and evaluate sources”,

(c) “thoroughly analyze assumptions behind and context of your own or others’ ideas”,

(d) “argue a complex position and one that takes counter-arguments into account,” and

(e) “arrive at logical and well informed conclusions”. [2]

While you are probably used to providing some evidence for your claims, you can see that college-level expectations go quite a bit further. When professors assign an analytical paper, they don’t just want you to formulate a plausible-sounding argument. They want you to dig into the evidence, think hard about unspoken assumptions and the influence of context, and then explain what you really think and why.

Thinking critically—thoroughly questioning your immediate intuitive responses—is difficult work, but every organization and business in the world needs people who can do that effectively. The ability to think critically also entails being able to hear and appreciate multiple perspectives on an issue, even if we don’t agree with them. While writing time is often solitary, it’s meant to plug you into a vibrant academic community. What your professors want, overall, is for you to join them in asking and pursuing important questions about the natural, social, and creative worlds.

- Terrel Rhodes, ed., Assessing Outcomes and Improving Achievement: Tips and Tools for Using Rubrics (Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2010). ↵

- Ibid ↵

Writing for Academic and Professional Contexts: An Introduction Copyright © 2023 by Sheridan College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Understanding Your Purpose

The first question for any writer should be, "Why am I writing?" "What is my goal or my purpose for writing?" For many writing contexts, your immediate purpose may be to complete an assignment or get a good grade. But the long-range purpose of writing is to communicate to a particular audience. In order to communicate successfully to your audience, understanding your purpose for writing will make you a better writer.

A Definition of Purpose

Purpose is the reason why you are writing . You may write a grocery list in order to remember what you need to buy. You may write a laboratory report in order to carefully describe a chemistry experiment. You may write an argumentative essay in order to persuade someone to change the parking rules on campus. You may write a letter to a friend to express your excitement about her new job.

Notice that selecting the form for your writing (list, report, essay, letter) is one of your choices that helps you achieve your purpose. You also have choices about style, organization, kinds of evidence that help you achieve your purpose

Focusing on your purpose as you begin writing helps you know what form to choose, how to focus and organize your writing, what kinds of evidence to cite, how formal or informal your style should be, and how much you should write.

Types of Purpose

Don Zimmerman, Journalism and Technical Communication Department I look at most scientific and technical writing as being either informational or instructional in purpose. A third category is documentation for legal purposes. Most writing can be organized in one of these three ways. For example, an informational purpose is frequently used to make decisions. Memos, in most circles, carry key information.

When we communicate with other people, we are usually guided by some purpose, goal, or aim. We may want to express our feelings. We may want simply to explore an idea or perhaps entertain or amuse our listeners or readers. We may wish to inform people or explain an idea. We may wish to argue for or against an idea in order to persuade others to believe or act in a certain way. We make special kinds of arguments when we are evaluating or problem solving . Finally, we may wish to mediate or negotiate a solution in a tense or difficult situation.

Remember, however, that often writers combine purposes in a single piece of writing. Thus, we may, in a business report, begin by informing readers of the economic facts before we try to persuade them to take a certain course of action.

In expressive writing, the writer's purpose or goal is to put thoughts and feelings on the page. Expressive writing is personal writing. We are often just writing for ourselves or for close friends. Usually, expressive writing is informal, not intended for outside readers. Journal writing, for example, is usually expressive writing.

However, we may write expressively for other readers when we write poetry (although not all poetry is expressive writing). We may write expressively in a letter, or we may include some expressive sentences in a formal essay intended for other readers.

Entertaining

As a purpose or goal of writing, entertaining is often used with some other purpose--to explain, argue, or inform in a humorous way. Sometimes, however, entertaining others with humor is our main goal. Entertaining may take the form of a brief joke, a newspaper column, a television script or an Internet home page tidbit, but its goal is to relax our reader and share some story of human foibles or surprising actions.

Writing to inform is one of the most common purposes for writing. Most journalistic writing fits this purpose. A journalist uncovers the facts about some incident and then reports those facts, as objectively as possible, to his or her readers. Of course, some bias or point-of-view is always present, but the purpose of informational or reportorial writing is to convey information as accurately and objectively as possible. Other examples of writing to inform include laboratory reports, economic reports, and business reports.

Writing to explain, or expository writing, is the most common of the writing purposes. The writer's purpose is to gather facts and information, combine them with his or her own knowledge and experience, and clarify for some audience who or what something is , how it happened or should happen, and/or why something happened .

Explaining the whos, whats, hows, whys, and wherefores requires that the writer analyze the subject (divide it into its important parts) and show the relationship of those parts. Thus, writing to explain relies heavily on definition, process analysis, cause/effect analysis, and synthesis.

Explaining versus Informing : So how does explaining differ from informing? Explaining goes one step beyond informing or reporting. A reporter merely reports what his or her sources say or the data indicate. An expository writer adds his or her particular understanding, interpretation, or thesis to that information. An expository writer says this is the best or most accurate definition of literacy, or the right way to make lasagne, or the most relevant causes of an accident.

An arguing essay attempts to convince its audience to believe or act in a certain way. Written arguments have several key features:

- A debatable claim or thesis . The issue must have some reasonable arguments on both (or several) sides.

- A focus on one or more of the four types of claims : Claim of fact , claim of cause and effect , claim of value , and/or claim of policy (problem solving).

- A fair representation of opposing arguments combined with arguments against the opposition and for the overall claim.

- An argument based on evidence presented in a reasonable tone . Although appeals to character and to emotion may be used, the primary appeal should be to the reader's logic and reason.

Although the terms argument and persuasion are often used interchangeably, the terms do have slightly different meanings. Argument is a special kind of persuasion that follows certain ground rules. Those rules are that opposing positions will be presented accurately and fairly, and that appeals to logic and reason will be the primary means of persuasion. Persuasive writing may, if it wishes, ignore those rules and try any strategy that might work. Advertisements are a good example of persuasive writing. They usually don't fairly represent the competing product, and they appeal to image, to emotion, to character, or to anything except logic and the facts--unless those facts are in the product's favor.

Writing to evaluate a person, product, thing, or policy is a frequent purpose for writing. An evaluation is really a specific kind of argument: it argues for the merits of the subject and presents evidence to support the claim. A claim of value --the thesis in an evaluation--must be supported by criteria (the appropriate standards of judgment) and supporting evidence (the facts, statistics, examples, or testimonials).

Writers often use a three-column log to set up criteria for their subject, collect relevant evidence, and reach judgments that support an overall claim of value. Writing a three-column log is an excellent way to organize an evaluative essay. First, think about your possible criteria. Remember: criteria are the standards of judgment (the ideal case) against which you will measure your particular subject. Choose criteria which your readers will find valid, fair, and appropriate . Then, collect evidence for each of your selected criteria. Consider the following example of a restaurant evaluation:

Overall claim of value : This Chinese restaurant provides a high quality dining experience.

Problem Solving

Problem solving is a special kind of arguing essay: the writer's purpose is to persuade his audience to adopt a solution to a particular problem. Often called "policy" essays because they recommend the readers adopt a policy to resolve a problem, problem-solving essays have two main components: a description of a serious problem and an argument for specific recommendations that will solve the problem .

The thesis of a problem-solving essay becomes a claim of policy : If the audience follows the suggested recommendations, the problem will be reduced or eliminated. The essay must support the policy claim by persuading readers that the recommendations are feasible, cost-effective, efficient, relevant to the situation, and better than other possible alternative solutions.

Traditional argument , like a debate, is confrontational. The argument often becomes a kind of "war" in which the writer attempts to "defeat" the arguments of the opposition.

Non-traditional kinds of argument use a variety of strategies to reduce the confrontation and threat in order to open up the debate.

- Mediated argument follows a plan used successfully in labor negotiations to bring opposing parties to agreement. The writer of a mediated argument provides a middle position that helps negotiate the differences of the opposing positions.

- Rogerian argumen t also wishes to reduce confrontation by encouraging mutual understanding and working toward common ground and a compromise solution.

- Feminist argument tries to avoid the patriarchal conventions in traditional argument by emphasizing personal communication, exploration, and true understanding.

Combining Purposes

Often, writers use multiple purposes in a single piece of writing. An essay about illiteracy in America may begin by expressing your feelings on the topic. Then it may report the current facts about illiteracy. Finally, it may argue for a solution that might correct some of the social conditions that cause illiteracy. The ultimate purpose of the paper is to argue for the solution, but the writer uses these other purposes along the way.

Similarly, a scientific paper about gene therapy may begin by reporting the current state of gene therapy research. It may then explain how a gene therapy works in a medical situation. Finally, it may argue that we need to increase funding for primary research into gene therapy.

Purposes and Strategies

A purpose is the aim or goal of the writer or the written product; a strategy is a means of achieving that purpose. For example, our purpose may be to explain something, but we may use definitions, examples, descriptions, and analysis in order to make our explanation clearer. A variety of strategies are available for writers to help them find ways to achieve their purpose(s).

Writers often use definition for key terms of ideas in their essays. A formal definition , the basis of most dictionary definitions, has three parts: the term to be defined, the class to which the term belongs, and the features that distinguish this term from other terms in the class.

Look at your own topic. Would definition help you analyze and explain your subject?

Illustration and Example

Examples and illustrations are a basic kind of evidence and support in expository and argumentative writing.

In her essay about anorexia nervosa, student writer Nancie Brosseau uses several examples to develop a paragraph:

Another problem, lying, occurred most often when my parents tried to force me to eat. Because I was at the gym until around eight o'clock every night, I told my mother not to save me dinner. I would come home and make a sandwich and feed it to my dog. I lied to my parents every day about eating lunch at school. For example, I would bring a sack lunch and sell it to someone and use the money to buy diet pills. I always told my parents that I ate my own lunch.

Look at your own topic. What examples and illustrations would help explain your subject?

Classification

Classification is a form of analyzing a subject into types. We might classify automobiles by types: Trucks, Sport Utilities, Sedans, Sport Cars. We can (and do) classify college classes by type: Science, Social Science, Humanities, Business, Agriculture, etc.

Look at your own topic. Would classification help you analyze and explain your subject?

Comparison and Contrast

Comparison and contrast can be used to organize an essay. Consider whether either of the following two outlines would help you organize your comparison essay.

Block Comparison of A and B

- Intro and Thesis

- Description of A

- Description of B (and how B is similar to/different from A)

Alternating Comparison of A and B

- Aspect One: Comparison/contrast of A and B

- Aspect Two: Comparison/contrast of A and B

- Aspect Three: Comparison/contrast of A and B

Look at your own topic. Would comparison/contrast help you organize and explain your subject?

Analysis is simply dividing some whole into its parts. A library has distinct parts: stacks, electronic catalog, reserve desk, government documents section, interlibrary loan desk, etc. If you are writing about a library, you may need to know all the parts that exist in that library.

Look at your own topic. Would analysis of the parts help you understand and explain your subject?

Description

Although we usually think of description as visual, we may also use other senses--hearing, touch, feeling, smell-- in our attempt to describe something for our readers.

Notice how student writer Stephen White uses multiple senses to describe Anasazi Indian ruins at Mesa Verde:

I awoke this morning with a sense of unexplainable anticipation gnawing away at the back of my mind, that this chilly, leaden day at Mesa Verde would bring something new . . . . They are a haunting sight, these broken houses, clustered together down in the gloom of the canyon. The silence is broken only by the rush of the wind in the trees and the trickling of a tiny stream of melting snow springing from ledge to ledge. This small, abandoned village of tiny houses seems almost as the Indians left it, reduced by the passage of nearly a thousand years to piles of rubble through which protrude broken red adobe walls surrounding ghostly jet black openings, undisturbed by modern man.

Look at your own topic. Would description help you explain your subject?

Process Analysis

Process analysis is analyzing the chronological steps in any operation. A recipe contains process analysis. First, sift the flour. Next, mix the eggs, milk, and oil. Then fold in the flour with the eggs, milk and oil. Then add baking soda, salt and spices. Finally, pour the pancake batter onto the griddle.

Look at your own topic. Would process analysis help you analyze and explain your subject?