Caught between academic calling and academic pressure? Working time characteristics, time pressure and time sovereignty predict PhD students’ research engagement

- Open access

- Published: 08 September 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Theun Pieter van Tienoven ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1532-254X 1 ,

- Anaïs Glorieux ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8127-792X 1 ,

- Joeri Minnen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7494-2004 1 &

- Bram Spruyt ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0573-724X 1

1852 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

PhD students come to work in academic environments that are characterized by long working hours and work done on non-standard hours due to increasing job demands and metric evaluation systems. Yet their long working hours and work at non-standard hours are often seen as a logical consequence of their intellectual quest and academic calling and may even serve as a proxy for their research engagement. Against that background, quantitative data from 514 PhD students were used to unravel the complex relationships between different aspects of time use and PhD students’ work engagement. While the results support the academia as a calling thesis to some extent, they also show that the relationships between long and non-standard working hours and research engagement are partly negated by the fact that the same working time characteristics lead to perceived time pressure and lack of time sovereignty, which in turn negatively affects their engagement. Moreover, the mechanism behind this negation varies across scientific disciplines. These subjective working time characteristics are the same alarm signals that are flagged as risk factors in academic staff for occupational stress, burnout, and work-life imbalance and thus cannot be ignored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Work-Life Balance: Exploring the Myths and Realities of Family, Home, Work, and Life Pressures for Early Career Academics

Academic Work, Working Conditions and Job Satisfaction

Maritime education factors and presenteeism: a comparative quantitative study

Virginia R. Ferritto

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Occupational stress in (early career) academics as a result of long working hours, non-standard work, the managerialism of work, and stressors outside the workplace is well documented in the academic literature (Lee et al., 2022 ; Sabagh et al., 2018 ; Watts and Robertson, 2011 ). PhD students, however, are hardly included in the occupational group of academics, presumably due to the lack of clarity about their employment situation (Flora, 2007 ). PhD scholarships are often fiscally exempted. Consequently, PhD students with university, external, or personal funds, or when hired as graduate teaching assistants, sign scholarship agreements which are not fully comparable to an employment contract. As a result, PhD students are much more often evaluated in terms of their motivation to pursue a PhD (Naylor et al., 2016 ; Skakni, 2018 ) and the obstacles, challenges, and hurdles they encounter on their ‘perilous journey’ (Woolston, 2019 , 2022 ). Similar, the assessment of their workload is often made in terms of combining a teaching assignment with doctoral research (Borrego et al., 2021 ; Muzaka, 2009 ) or being used as cheap labour for several research tasks (Zhao et al., 2007 ). The most specific hard numbers regarding PhD students’ time use and occupational stress come from the 2022 Nature Graduate Survey in which 43.1% of PhD students worldwide report working on average 50 h per week or more. Around 40% is not or not at all satisfied with their working hours, and almost half mentions their work/life balance in the top three of the most challenging issues when conducting PhD research (Nature Research, 2022 ). To the best of our knowledge, working hours of PhD students are seldom evaluated beyond these proxies. This is a knowledge gap: time use is a multidimensional phenomenon including more than how long PhD students work (i.e. duration), but also when they work (i.e. timing of work) or how work is embedded in their daily lives (i.e. sequence of work and other activities) (Zerubavel, 1985 ). Moreover, these temporal aspects of working time can give rise to experiences such as time pressure or time sovereignty. Such experiences result from the combination of objective characteristics of time use and the expectations regarding these characteristics. Only by documenting these different aspects of time use and subsequently unravelling their mutual relationships with regard to outcomes can scientists get a deep understanding of the relevance of working time characteristics for PhD students. This contribution aims to address this lacune in scientific knowledge by assessing objective and subjective working time characteristics and associating them with PhD students’ engagement in their PhD research.

This paper focusses on PhD students. However, due to the lack of thorough studies on working hours specific to PhD students, we first describe the characteristics of the working environment (i.e. academia) in which they conduct their research. This gives us a better grasp of the relevant aspects of working time characteristics and their association with work engagement.

Long working hours and weekend work in academia result from high academic job demands (Anderson, 2006 ; Kinman and Jones, 2008 ). Several challenges have been reported to contribute to increasing job demands. The need to balance teaching demands and research workload is a considerable challenge that can lead to role conflict (Sabagh et al., 2018 ) and time conflict (Tham and Holland, 2018 ). This is further aggravated by ‘corporatisation’ (Holmwood, 2014 ) or the ‘managerialism phenomenon’ (Erickson et al., 2021 ; Lee et al., 2022 ) which signifies universities’ high performance-based management focussed on high academic productivity and metric-driven performance markers. Consequently, academics report an increasing workload as well as an increase in the need to work outside contractual hours to meet work requirements (Fetherston et al., 2021 ; Houston et al., 2006 ; Kinman and Jones, 2008 ).

The excess working hours result in a ‘work-life merge’ which, according to a study by Fetherston et al. ( 2021 ), is largely considered necessary by academics to meet increasing job demands in the first place and a major cause of time pressure (Watts and Robertson, 2011 ). This undermines the idea of flexible working hours which has been suggested to be helpful to academic parents (Jakubiec, 2015 ). It also conflicts with the idea of the ‘academic calling’, i.e. academia being a vital part of who one is, where long working days are not experienced as such (Fetherston et al., 2021 ). In fact, high job demands, increasing workload, and work-life merge contribute to occupational stress (Lee et al., 2022 ), burnout (Sabagh et al., 2018 ), and severe disruption of work-life balance (Ashencaen Crabtree et al., 2021 ; Kinman and Jones, 2008 ). On the contrary, a well-balanced teaching load and research time are associated with significantly lower levels of emotional exhaustion (Gonzalez and Bernard, 2006 ). Similarly, a review by Sabagh et al. ( 2018 ) finds that engagement—the energetic and effective connection with one’s work (Schaufeli et al., 2006a )—can serve as buffer for the negative consequences of the increasing academic job demands. The above arguments further underscore that if we study the relevance of time allocation in academia, we should not only focus on its objective characteristics (e.g. number of hours) but also how these are experienced.

- PhD students

PhD students represent a particular and vulnerable academic group, not only because they are the lowest in the academic hierarchy, but also because their status as employee is not always clear (Flora, 2007 ). Their scholarships are often fiscally exempted, and scholarship agreements do not always fully correspond to the rights and benefits of employment contracts. More importantly, their progress and successful completion are highly dependent on the support they receive from their supervisor (Heath, 2002 ; Lee, 2008 ). Research shows that ultimately supervisors’ support is more important than their academic qualities in achieving a PhD (Dericks et al., 2019 ). However, it is precisely these academic qualities that supervisors are (increasingly) judged on in metric output-oriented academia (e.g. citation score, number of publications, amount and type of project funding, number of MA and PhD students under their supervision). There is ample reason to belief that the above-mentioned increasing job demands are reflected upon PhD students as well.

The existing research supports the latter assumption. PhD students across all scientific disciplines sometimes come into contact with exploitative supervisor behaviour (Zhao et al., 2007 ). This seems particularly true for graduate teaching assistants. Their increasing teaching load shifts the balance between teaching duties and research time even further resulting in substantial time pressure and a low expectation of obtaining their PhD at all (Glorieux et al., forthcoming ). In contexts where the teaching load is much more distributed amongst all PhD students, such as in the Netherlands and the UK (Park and Ramos, 2002 ; Sonneveld and Tigchelaar, 2009 ), the pressure is partly relieved for the specific group of teaching assistants. PhD students’ scholarship status, as opposed to employment status, means that completing their PhD trajectory is often studied in terms of motivational characteristics such as an intellectual quest or self-actualization (Naylor et al., 2016 ; Skakni, 2018 ). Such individualistic lens, however, neglects the relevance of the more structural characteristics of their work environment and how PhD students cope with them. As a result, not much knowledge exists on PhD students’ working hour characteristics. This contribution aims to provide an impetus to close this knowledge gap.

Additionally, it seems that working conditions of academics in (bio)medical sciences and sciences disciplines are traditionally more vocalized in scientific journals. This was once more demonstrated when discussing the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic (see discussion in Van Tienoven et al., 2022 ). Although all disciplines face increasing job demands due to metric-driven productivity evaluations, each discipline comes with its particular characteristics of doing PhD research that impact working time.

Human sciences, for example, are characterized by more individual work. PhD students in these disciplines usually have to come up with their own research project. To secure their own funding, they have to write grant proposals (Torka, 2018 ) or—more than PhD students in other disciplines—take on teaching tasks (Groenvynck et al., 2011 ). Doctoral research in the human sciences is often quite isolated, in the sense that the PhD student is the only person that is appointed to the project (Torka, 2018 ), which could increase the pressure to get everything done. In addition, participating in public debates and writing commissioned reports—more common in the human sciences—can reduce the time they can spend on their PhD research. All this makes the development of a research plan with clear milestones and deadlines all the more important, as organic teamwork usually does not occur.

This is different in the natural sciences, where PhD students are usually part of a larger research team (Larivière, 2012 ; Torka, 2018 ) and usually receive more financial support through departmental programmes (Sverdlik et al., 2018 ). These PhD students often do not have their own individual projects but are responsible for part of a collective project. For example, PhD students in the natural sciences are more dependent on external factors (e.g. the progress of other people’s work, the availability of labs and equipment). As a result, the planning of their project depends on mutual agreements, and they often have much less control over the exact timing (Torka, 2018 ).

The above-mentioned differences in experience and needs with regard to the organization of working time lead to assess the potential moderating role of the scientific discipline for the relationships that we study.

Working time indicators

From the above, it becomes clear that working time can be conceptualised based on objective and subjective indicators. Objective then relates to calculable indicators such as the number of working hours, the times worked on non-standard hours, and the composition of the workload. In this study, objective time indicators are the number of working hours, the frequency of evening and weekend work, and the balance between teaching duties and research time. Yet following the ‘academic calling’ hypothesis, long working hours or working on non-standard work as such are not necessarily an issue for academics with high engagement in their work (Sabagh et al., 2018 ). For the latter, working long hours may be a means towards self-actualization. This, again, underscores the importance of including indicators of working time which tap into how working time is experienced such as the extent to which the workload and work-life merge lead to the feeling of constantly being pressed for time (Watts and Robertson, 2011 ) or the feeling of having no control or authority over one’s own time (Ashencaen Crabtree et al., 2021 ; Kinman and Jones, 2008 ).

Time pressure does not arise solely from having too little time but is also related to the aspirations that individuals have and the normative expectations that they experience to use their time (Kleiner, 2014 ). The latter are external to the individual and arise from the normative structures of their work environment. To measure the subjective experience of being pressed for time, we use an item scale that simultaneously gauges the feeling of not having enough time, the feeling of aspiring more than can be done in the current timeframe, and the feeling that normative expectations weigh too heavy on the allocation of time.

Additionally, the use of time is not limited to the work environment. We constantly face demands from different life spheres including our work life but, for example, also our family life and social life. The extent to which we can align these demands in function of our priorities and values depends on the extent to which we experience autonomy over our own time (Southerton, 2020 ). A lack of time sovereignty hampers setting boundaries and prioritizing activities that are meaningful and, thus, might result in an unhealthy integration of different life spheres.

In this study, we not only assess the relevance of these subjective indicators of working time, but also to what extent these indicators mediate the relationship between objective characteristics of time use and the outcome.

In summary, in this contribution, we analyse the objective and subjective working time indicators of PhD students and relate these characteristics to PhD students’ engagement in their doctoral research. The latter is a well-known predictor of the journey or intellectual quest in doctoral research. We assume that the ‘academic calling’ hypothesis holds for PhD students. However, we also acknowledge that once the number of working hours, the work done on non-standard hours, and the composition of the workload take the upper hand, issues such as time pressure and lack of time sovereignty come into play. We will test the hypothesis that the positive direct effect (i.e. the academic calling) is partially offset by a negative indirect effect that runs along indicators of subjective working time. Acknowledging potential differences in scientific disciplines, we also investigate to what extent we conclude differently on the hypothesis for different scientific disciplines.

Data and method

Data come from the 2022 PhD Survey held at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) in Belgium ( n = 836; response rate = 45.4%). This annual survey is commissioned by the Researcher Training & Development Office (RTDO) at the VUB and conducted by the Research Group TOR (Tempus Omnia Revelat) at the same university. The PhD Survey serves as a monitor instrument to evaluate the support provided to PhD students by RTDO and at the same time monitors aspects of well-being and job satisfaction of PhD students. As a result, the strength of the data lies in the heterogeneity of PhD students surveyed. PhD students across all disciplines, regardless of their teaching duties and funding nature (i.e. external scientific, internal scientific, industry, teaching assistant, personal funds, unfunded) are included.

The 2022 survey is the fifth wave of the annual PhD Survey since it piloted in 2017. All PhD students registered at VUB on the 1st of January preceding the launch of the next wave are invited. Typically, PhD students start in October or November, but it is possible to start at any time of the academic year. Doctoral research typically lasts for 4 years and ends with a successful oral defence of the thesis.

The PhD Survey exists of a single online questionnaire that is hosted on the data collection platform MOTUS and accessible through the MOTUS web application. Footnote 1 The PhD Survey takes place in the last 2 weeks of April and the whole month of May. PhD students across all faculties receive an email with login credentials to participate in the survey. Up to two reminders are sent. PhD students are explicitly asked to give their consent before starting the questionnaire. The design of the study was approved by the ethics committee of the VUB (file number ECHW_318).

Institutional context

The VUB is located in the Brussels Capital Region in Belgium. In the academic year 2020–2021, just over 20,000 students were enrolled in 172 study programmes of which almost one third is taught in English. About 10% of all students are enrolled in PhD programmes. To be admitted to these programmes, PhD students can rely on different funding opportunities, such as general or themed scholarships from (inter)national funding institutions (e.g. the National Research Council), research funding from a research project or multiple research projects in the name of the supervisor, or by combining PhD research with a position as graduate teaching assistant (GTA).

At the start, PhD students enroll in the compulsory Doctoral Training Programme which facilitates PhD students with the possibility to develop their (research) skills through, for example, courses, seminars, workshops, and career coaching. There are three different doctoral schools under which all faculties are divided. The Doctoral School of Natural Sciences and (Bioscience) Engineering (NSE) includes the Faculty of Engineering Sciences and the Faculty of Sciences and Biosciences Engineering. The Doctoral School of Human Sciences (DSh) includes the Faculty of Social Sciences and Solvay Business School, the Faculty of Arts and Philosophy, the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Science, and the Faculty of Law and Criminology. The Doctoral School of Life Science and Medicine (LSM) includes the Faculty of Medical Sciences and Pharmacy and the Faculty of Physical Education and Physiotherapy.

All PhD students are expected to engage in teaching for at most 20% of their time, except GTAs, who are expected to engage in teaching for at most 40% of their time. PhD students, including GTAs, are expected to use the remaining time for their research aimed at obtaining their PhD. Their doctoral research typically lasts for 4 years, or 6 years in case of GTAs, and ends with a successful oral defence of the thesis. Within Flanders, the Dutch-speaking community in Belgium and responsible for Dutch-language education, education is fairly equal. This also applies to the doctoral training. Universities apply equal admission conditions, and prestige differences between universities are much smaller than those known from Anglo-Saxon countries. Most doctoral students receive a similar salary. The universities in Flanders work in roughly the same way, which means that our findings can be extended to the Flemish context.

Explanatory variables

For the explanatory variables, we distinguish between objective and subjective indicators of working time. Objective means here that characteristics of the working time are questioned based on commonly shared and recognizable time indicators (e.g. the number of working hours, worked/not worked between 8 pm and 12 am). The answers to these questions remain the respondents’ estimates. Subjective means here that it concerns experienced characteristics of working time (e.g. experienced time pressure). They include a clear level of appreciation and result from the confrontation of the expected aspects of working time and its actual characteristics. The objective time indicators are the following.

Total working time. Estimated total working time in hours per week (scaled).

Share of non-research time . Expressed as a percentage and calculated as one minus the estimated time spent on research over the estimated total working time in hours per week. Outliers for time estimates are set at mean ± 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Non-standard working hours. A summation scale (ranging from 0 to 10) of the items ‘Work in evening (after 6 pm)’, ‘Work at night (after midnight)’, ‘Work on Saturday)’, and ‘Work on Sunday’ that were answered using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always. A principal component analysis revealed one component with Eigenvalue = 2.494 and 62.3% of variance explained. Cronbach’s alpha equals 0.796, and the correlation between the factor score and summation score equals r > 0.99.

The subjective time indicators are the following.

Experienced time pressure . Experienced time pressure is measured by a summation scale (ranging from 0 to 10) of the items ‘Too much is expected of me’, ‘I never catch up with my work’, ‘I never have time for myself’, ‘There are not enough hours in the day for me’, ‘I frequently have to cancel arrangements I have made’, ‘I have to do more than I want to do’, ‘I have no time to do the things I have to do’, and ‘More is expected from me than I can handle’ using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = totally agree (Van Tienoven et al., 2017 ). A principal component analysis revealed one component with Eigenvalue = 4.661 and 58.3% of variance explained. Cronbach’s alpha equals 0.895, and the correlation between the factor score and summation score equals r > 0.99.

Experienced lack of time sovereignty. Experienced lack of time sovereignty is measured by an inverted summation scale (ranging from 0 to 10) of the items ‘I have enough influence on my working hours’, ‘I can adjust my working time to my family life’, ‘I have ample opportunities to take time off whenever that suits me’, and ‘The VUB/my supervisor offers sufficient opportunities for employees to adjust their tasks depending on their private situation’ that were answered using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = totally agree. A principal component analysis revealed one component with Eigenvalue = 2.577 and 64.4% of variance explained. Cronbach’s alpha equals 0.814, and the correlation between the factor score and summation score equals r > 0.99.

Dependent variable

Most PhD students receive a grant, which means that their employment status is not always clear (Flora, 2007 ). Nevertheless, they end up in a professional work environment with job demands and responsibilities expected of an employee; the most important of which is conducting research. To measure the extent of engagement in PhD research , we therefore use the validated 9-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9) in combination with three items that measure intrinsic motivation, which is also specific to the scholarship status of PhD students (Skakni, 2018 ). The UWES-9 measures vigour, dedication, and absorption based on three items per aspect of work engagement (Schaufeli et al., 2006b ). The items are the following: ‘At my job, I feel like bursting with energy’, ‘At my job, I feel strong and vigorous’, and ‘When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work’ for vigour; ‘I am immersed in my work’, ‘I get carried away when I’m working’, ‘I am happy when I’m working intensely’ for absorption; and ‘I am enthusiastic about my job’, ‘I am proud of the work that I do’, ‘My job inspires me’ for dedication. The UWES-9 scale has demonstrated high internal consistency and validity (Schaufeli et al., 2006a ). Previous work with this scale revealed that people who score high on the work engagement scale, score lower on aspects of burnout, report lower levels of depression and distress, and score higher on job satisfaction and organizational commitment. High scores on the work engagement scale also correlate positively with job characteristics such as autonomy, performance feedback, and task variety (for a discussion, see Saks and Gruman, 2014 ).

Unlike most paid work, the PhD track has a clear finality that is motivated professionally, intellectually, or by a desire for self-actualization (Skakni, 2018 ). In social cognitive theory, this intrinsic motivation reflects the willingness and interest to pursue efforts and thus engage oneself in PhD research (Gu et al., 2017 ). To measure the specificity of engagement in PhD research in a more meaningful and relevant way, we therefore add three additional items that explicitly measure the intrinsic motivation to pursue a PhD. At the same time, this brings the construct of engagement more in line with the idea of an academic calling. The added items are the following: ‘I can make the world a better place with the work that I do’, ‘I’m helping science move forward with the work that I do’, and ‘I improve things with the work that I do’. All items were answered using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = I never have this feeling to 4 = I always have this feeling. Engagement is then measured based on a summation scale (ranging from 0 to10). A principal component analysis revealed one component with Eigenvalue = 6.076 and 50.6% of variance explained. Cronbach’s alpha equals 0.908, and the correlation between the factor score and summation score equals r > 0.99.

Control variables

Given that the work-life merge is of much more concern for female academics (Toffoletti and Starr, 2016 ) and female academics are reported to be more vulnerable to the negative consequences of increasing job demands than male academics (Watts and Robertson, 2011 ), we control for sex using a dummy for female. Due to small numbers, PhD students that identify themselves as non-binary are omitted from the data ( n = 3).

Where in Anglo-Saxon countries, the form of funding (e.g. fellowship, research assistant, teaching assistant) influences the amount of time available for research (Grote et al., 2021 ), the allocation of PhD students’ time over teaching and research is much more formally arranged in northwestern continental Europe. Acknowledging that research skills might be enhanced by teaching experience (Jucks and Hillbrink, 2017 ) and protecting PhD students from becoming means to mitigate increasing teaching demands, contracts in Belgium stipulate that PhD students are not expected to spend more than 20% of their time on teaching (e.g. guest lectures, grading, BA or MA thesis supervision). For GTAs, this is 40%. However, both regular PhD students and GTAs often indicate that when they also include preparation for teaching, they often spend much more time on it than expected (Machette, 2021 ). This applies in particular to younger PhD students. Since PhD students, regardless of their funding type, are expected to teach, we use a dummy variable to control for whether teaching exceeds contractual hours . PhD students estimated their weekly time spent on teaching activities in the PhD Survey. Outliers were set at over 38 h per week (i.e. the equivalent of a fulltime workweek). If the ratio time spent teaching over total working time exceeded 20% (or 40% in case of GTAs), PhD students are considered to teach more than contractually stipulated.

Analysis plan

We apply structural equation modelling in R with the lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012 ) to investigate whether and how objective and subjective indicators of working time associate with engagement in PhD research. First, an overall path model is fitted for the entire sample. Next, we aim to explore whether these associations vary by scientific discipline. Therefore, we stratify the models by doctoral schools at the VUB.

Model fit will be determined based on Chi-square, CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR. Cut-off points for fit measures are set following Hu and Bentler ( 1999 ): CFI > 0.90, RMSEA < 0.07, and SRMS < 0.05. The model fit statistics assess to what extent the patterns identified in this sample can be generalized to the underlying population. As the PhD survey is an annual survey, an alternative and arguably stricter test regarding the stability and generality of our models entails that we re-estimate our model on different samples. Therefore, in the Supplementary Material Appendix, Table A1, we provide the results for the data from the 2021 and 2020 edition of the PhD survey. These analyses confirmed the substantive conclusions derived from the analysis of the 2022 data. We test the equality of regression coefficients using Wald’s z -test (Paternoster et al., 1998 ). Table 1 shows the characteristics for the total sample and stratified by doctoral schools.

PhD students score 6.3 on 10 for their engagement in their PhD research, and this does not vary across doctoral schools nor does their score for working on non-standard hours (3.6 on 10). PhD students spend on average a third of their time on other tasks than their PhD research. In the doctoral school of NSE, this share is substantially lower. PhD students across all doctoral schools say to work just over 40 h per week. Experienced time pressure tends to be higher, and experienced time sovereignty tends to be lower in the doctoral school of LSM. Albeit the sample exists of equal shares of female and male PhD students, female PhD students are significantly underrepresented in the doctoral school of NSE. Finally, just under one in five PhD students report that their teaching exceeds contractual hours.

Working time experience and engagement in PhD research

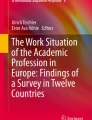

Figure 1 shows the overall path model with standardized regression coefficients. The model fit indices show a good fit (chi-square = 11.323, CFI = 0.997, RMSEA = 0.016, SRMR = 0.024). Additionally, the overall path models for earlier waves of the PhD Survey (2021 and 2020) show that results are replicable (see Supplementary Material Appendix A, Table A1).

Path model (wave = 2022, n = 514), *** p ≤ 0.001, ** p ≤ 0.01, * p ≤ 0.05, (*) p ≤ 0.10

The variables that control the objective time indicators show that the hypothesized associations between sex and working on non-standard hours or total working time are not significant (see Table 2 ). Working on non-standard hours (β = 0.088), the share of total working time not spent on research (β = 0.334), and total working time (β = 0.168) significantly increase when teaching exceeds the number of hours stipulated in the contract. Total working hours (β = 0.162) and the extent of non-standard working hours (β = 0.211) are significantly and positively associated with the engagement in PhD research. All three objective indicators of working time associate significantly positively with subjective indicators of working time and, in turn, these subjective indicators associate significantly negatively with engagement in PhD research. The feeling of being pressed for time significantly increases with a larger share of total working time not spent on research (β = 0.222), with more work being done on non-standard hours (β = 0.190) and with total working time (β = 0.135). Similarly, the feeling of lacking control over one’s working time in function of other responsibilities also increases with more working time not spent on research (β = 0.135) or done on non-standard hours (β = 0.157) and with longer working weeks (β = 0.231). In turn, the more time pressure one experiences (β = − 0.243) and the more lack of time sovereignty one experiences (β = − 0.135), the lower one’s engagement in PhD research.

Table 3 shows that the total effect of working on non-standard hours on engagement in PhD research is β = 0.144, because the direct positive effect of working on non-standard hours (β = 0.211) is offset by the indirect negative effect of working on non-standard hours that runs along experienced time pressure (β = − 0.046) and along experienced lack of time sovereignty (β = − 0.021). Similarly, the total effect of total working time on engagement in PhD research is β = 0.098 because the direct effect (β = 0.162) is offset by negative indirect effects that run along experienced time pressure (β = − 0.033) and experienced lack of time sovereignty (β = − 0.031). The university-wide results confirm our hypothesis. Indeed, the positive direct effect parameter of working long and non-standard hours on engagement in PhD research is partially offset by a negative indirect relationship that runs along indicators of experienced time pressure and lack of time sovereignty.

Differences by doctoral schools

Table 4 shows the standardized regression coefficients of the path model stratified by doctoral schools. When we first look at the control variables, we see that there are no differences between female and male PhD students when it comes to working on non-standard working hours. Only in the DSh do female PhD students report lower total working time than their male peers (β = − 0.157). In all doctoral schools, PhD students report higher total working hours and a higher share of working time not spent on research when their teaching exceeds the contractual hours. The pairwise comparison of regression coefficients shows that the size of the effects is not significantly different between doctoral schools. Only PhD students in the doctoral school of NSE score significantly higher on the scale of non-standard working hours when their teaching exceeds the contractual hours (β = 0.127).

Direct effects are found in all doctoral schools, except for the association between total working time and engagement in PhD research in the doctoral school of LSM. The pairwise comparison of regression coefficients shows no differences in effect sizes across all doctoral schools.

Before concluding on the indirect effects, we look at the separate effects between objective and subjective indicators on the one hand and subjective indicators and engagement on the other. We start with experienced time pressure. In the doctoral school of DSh, all three objective indicators of working time associate significantly positively with experienced time pressure. In the doctoral school of LSM, feelings of time pressure only significantly increase when the share of non-research time increases. The same holds for the doctoral school of NSE. However, here, the degree of working non-standard hours also leads to more perceived time pressure. Although feelings of time pressure are affected by objective working time indicators differently across the doctoral schools, it remains that time pressure reduces PhD students’ engagement in their research across all doctoral schools. The pairwise comparison of regression coefficients also shows that effect sizes are equal in all doctoral schools.

Next, we look at the lack of time sovereignty. The extent of work done on non-standard hours significantly increases the lack of time sovereignty for PhD students in the doctoral schools of DSh and NSE. The effect parameter for the doctoral school of DSh (β = 0.287) is the largest and significantly larger than for the doctoral school of LSM (Δβ = 0.311). In both the doctoral school of DSh and LSM does an increased share of non-research time significantly increase the lack of time sovereignty. Again, the effect parameter is the largest for the doctoral school of DSh (β = 0.248). Finally, the total working time only associates positively with lack of time sovereignty in the doctoral schools of LSM and NSE. For both doctoral schools, the effect parameters (β = 0.296 and β = 0.322, respectively) are significantly larger than in the doctoral school of DSh (Δβ = 0.260 and Δβ = 0.286, respectively). Albeit the difference between regression coefficients across doctoral schools is not different from zero, we only find that an increase in the experience of lack of time sovereignty reduces PhD students’ engagement in their research in the doctoral school of NSE.

To test our hypothesis, Table 5 decomposes the total effect of working on non-standard hours and total working time into its direct and its indirect effects. The positive, direct effects are as reported in Table 4 . The negative, indirect effect of non-standard work that runs along experienced time pressure is only significant in the doctoral school of DSh and the doctoral school of NSE (β = − 0.070 and β = − 0.032). The indirect effect of non-standard work that runs along experienced lack of time sovereignty is only significant in the doctoral school of NSE (β = − 0.029). No indirect effects of working on non-standard hours are found for the doctoral school of LSM. The result is that the total effect of non-standard hours on engagement in PhD research is significant for the doctoral school of DSh and NSE (β = 0.134 and β = 0.142, respectively) but not for LSM.

The indirect effect of total working time that runs along experienced time pressure is only significant for the doctoral school of DSh (β = − 0.054) whereas the negative indirect effect that runs along experienced lack of time sovereignty is only significant for the doctoral school of NSE (β = − 0.064). Again, the doctoral school of LSM reports no significant indirect effects. As a result, the total effect of total working time on engagement in PhD research is not significant for the doctoral school of LSM. The significant direct effect of total working time in the doctoral school of DSh is offset by the indirect negative effect of total working time such that the overall effect is insignificant. Only for the doctoral of NSE we found an overall positive effect on engagement in PhD research (β = 0.131).

The stratification of the analysis by disciplines leads us to partially confirm our hypothesis. The next section will discuss the meaning hereof in more detail.

Large-scale comparative research indicates that a substantial share of PhD students is unsatisfied with their long working hours and has experienced trouble with their work-life balance (Nature Research, 2022 ). Yet, PhD students are seldom evaluated in terms of their working hours. The focus lies much more on the perilous journey they embark on, and the extent to which their intrinsic motivation can overcome barriers during their intellectual quest (Naylor et al., 2016 ; Skakni, 2018 ; Woolston, 2022 ). At the same time, though, PhD students are employed in an environment that is highly susceptible to occupational stress and reduced well-being because of the working hours’ characteristics (Lee et al., 2022 ; Sabagh et al., 2018 ; Watts & Robertson, 2011 ). It is therefore remarkable that PhD students are rarely studied in terms of their working time distribution and, if they are, rarely looked at beyond the number of hours worked. It is reasonable to assume that, as with academic staff, other characteristics of working time, such as non-standard work or subjective experiences such as the work-life merge, also play a role for PhD students.

This contribution aims to shed light on the working time characteristics of PhD students and the extent to which they impact their engagement with their PhD research. It contributes to the existing knowledge on working conditions and the well-being of PhD students in three ways. Firstly, it looks beyond the idea that PhD students embark on a journey with all its (intellectual) challenges (Naylor et al., 2016 ; Skakni, 2018 ) and views PhD students as employees entering an academic work environment that, due to its high job demands and metric-based assessment criteria, may well cause occupational stress and a work-life merge (Fetherston et al., 2021 ). We, thus, assume that working time characteristics of PhD students, both in objective terms such as non-standard hours and long working days as well as in subjective terms such as time pressure and lack of time sovereignty, affect their engagement in their PhD research. Secondly, rather than using a single measure of (the amount of) working time, our study acknowledges the multidimensionality of the allocation of working time. By distinguishing different dimensions and using structural equation modelling to unravel their mutual relationships and predictive power regarding our outcome, we offer a much more nuanced view on PhD students’ time use. Thirdly, we use a university-wide sample of PhD students. This allows us to investigate potential differences in the association between working time characteristics and engagement in PhD research across scientific disciplines under similar institutional conditions.

In this contribution, we showed that, in general, working non-standard hours and working long hours impact engagement in PhD research both directly and indirectly. The direct effects are positive, meaning that working long and non-standard hours are associated with higher engagement in PhD research. This concurs with the idea of PhD research being an academic calling (Sabagh et al., 2018 ). It signifies a certain degree of motivation and commitment which in turn may of course also feed the number of working hours. However, this academic calling (and the possible mutually reinforcing dynamic between academic calling and the number of working hours) has a downside. There are also indirect effects of working non-standard hours and working long hours which run along experienced time pressure and experienced lack of time sovereignty that negatively associate with engagement in PhD research. In other words, and this is a crucial insight, the expected positive direct relationship for engaged PhD students might be offset by the negative indirect effects of long working days and non-standard work. Albeit the total effect remains positive, we, thus, must be aware that when it comes to working time characteristics two opposite mechanisms are at play. Long working hours and atypical work characterize committed PhD students, but at the same time, they can cause negative work experiences such as time pressure and lack of time sovereignty, which actually reduce their commitment. This finding raises some important questions for future exploration. Is there a threshold at which the negative experiences of long and non-standard hours overtake the positive impact of seeing one’s research as an academic calling (Conway et al., 2017 )? Or is the downside of an academic calling that PhD students work long hours and are very engaged in their research, but as a result of which setbacks in their research or personal life have a much greater impact (Sonnentag et al., 2008 )?

There are some outstanding differences, however, when looking at different scientific disciplines. We used the university’s doctoral schools as proxies for scientific disciplines: human sciences, sciences and engineering, and life sciences and medicine. Remarkably, we did not find any significant direct or indirect effect parameter of long working hours on engagement in PhD research for PhD students in life sciences and medicine. We did find a direct effect parameter of non-standard working hours on their engagement in PhD research but that was offset by the indirect effects completely rendering the total effect statistically insignificant. Working hour characteristics, therefore, seem to affect engagement in PhD research the least in the life sciences and medicine. Possible explanations are that PhD students combine their PhD research with already less regular schedules of specialist training in the hospital. Especially in medicine, irregular and long working hours are part of the job and possibly already expected and anticipated by PhD students based on their BA and MA experiences.

The opposite is found for PhD students in sciences and engineering. Although working non-standard hours and long working days positively affect their engagement in PhD research, the effect parameters of both indictors are offset by negative indirect effects that run along experienced lack of time sovereignty. Additionally, the effect parameter of working non-standard hours is offset by the negative indirect effect that runs along experienced time pressure. Compared to the other disciplines, the indirect effect that runs along the experienced lack of time sovereignty is the largest for this discipline. Possible explanations are that PhD students in sciences and technology are often part of larger projects in which they carry out partial research. Moreover, they are much more dependent than other disciplines on fixed time slots for technical machines, devices, and laboratory settings for conducting experiments. The resulting time constraints and the fact that their research results serve a greater research project may diminish their control over their own time to a greater extent and impose a degree of time pressure.

When it comes to time pressure, the largest indirect effects are reported for PhD students in human sciences. The positive direct effect of long working hours on their engagement in their PhD research is offset by the negative indirect effect that runs along experienced time pressure, rendering the total effect of long working hours insignificant. Although the total effect of working non-standard hours remains positively significant, the direct effect is offset by a third by the indirect effect that runs along time pressure. Possible explanations are that the human sciences, more than other scientific disciplines, are in much more direct and much more contact with their stakeholders in society. PhD students in the human sciences are usually more involved in pure activism and social impact initiatives. Moreover, it is a branch of science that receives a lot of resources from research projects commissioned by governments or interest groups (e.g. on education, culture, media, politics). PhD students who are funded through such projects spend a lot of time on stakeholder and science communication. All these extra tasks may lead to more perceived time pressure to get everything done.

This contribution is not without its limitations. This survey uses self-reported estimates of working hour characteristics. It is known that time diary methodology is more reliable. However, it is also known to require longer fieldwork periods and more effort from respondents. As such, it is not in line with the current study design but worth considering in future iterations to get a more reliable grasp of the temporal characteristics of doing PhD research. In its current form, not much is known about attrition of the sample. PhD students that faced a severe impact from working hours characteristics on their work-life or well-being might have dropped out. In that case, we may be underestimating the problem. Linking future research with the university’s administrative data would provide more information about attrition due to drop-out.

PhD students come to work in academic environments that are characterized by long working hours and work done on non-standard hours due to increasing job demands and metric evaluation systems. They are motivated by an intellectual quest and an academic calling that makes them put up with long working days and non-standard work which signifies their engagement in their PhD research. However, there is a downside that needs attention. The same working hour characteristics could indirectly affect their engagement negatively because they result in experiencing time pressure and lack of time sovereignty. These are the same alarm signals that are flagged as risk factors in academic staff for occupational stress, burnout, and work-life imbalance.

Data Availability

Raw data cannot be shared publicly because of the institution’s privacy regulations. Data code necessary to replicate results are available from the Vrije Universiteit Brussel’s Institutional Data Access (contact via [email protected]) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

MOTUS research platform 2016–2022. Available from: https://www.motusresearch.io/en .

Anderson, G. (2006). Carving out time and space in the managerial university. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 19 (5), 578–592.

Article Google Scholar

Ashencaen Crabtree, S., Esteves, L., & Hemingway, A. (2021). A ‘new (ab) normal’?: Scrutinising the work-life balance of academics under lockdown. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45 (9), 1177–1191.

Borrego, M., Choe, N. H., Nguyen, K., & Knight, D. B. (2021). STEM doctoral student agency regarding funding. Studies in Higher Education, 46 (4), 737–749.

Conway, S. H., Pompeii, L. A., Ruiz, G., de Porras, D., Follis, J. L., & Roberts, R. E. (2017). The identification of a threshold of long work hours for predicting elevated risks of adverse health outcomes. American Journal of Epidemiology, 186 (2), 173–183.

Dericks, G., Thompson, E., Roberts, M., & Phua, F. (2019). Determinants of PhD student satisfaction: the roles of supervisor, department, and peer qualities. Assessment & evaluation in higher education, 44 (7), 1053–1068.

Erickson, M., Hanna, P., & Walker, C. (2021). The UK higher education senior management survey: A statactivist response to managerialist governance. Studies in Higher Education, 46 (11), 2134–2151.

Fetherston, C., Fetherston, A., Batt, S., Sully, M., & Wei, R. (2021). Wellbeing and work-life merge in Australian and UK academics. Studies in Higher Education, 46 (12), 2774–2788.

Flora, B. H. (2007). Graduate assistants: Students or staff, policy or practice? The current legal employment status of graduate assistants. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 29 (3), 315–322.

Glorieux, A., Spruyt, B., Te Braak, P., Minnen, J., & van Tienoven, T. P. (forthcoming). When the student becomes the teacher: Determinants of self-estimated successful PhD completion among graduate teaching assistants.

Gonzalez, S., & Bernard, H. (2006). Academic workload typologies and burnout among faculty in seventh-day adventist colleges and universities in North America. Journal of Research on Christian Education, 15 (1), 13–37.

Groenvynck, H., Vandeveld, K., Van Rossem, R., Leyman, A., De Grande, H., Derycke, H., & De Boyser, K. (2011). Doctoraatstrajecten in Vlaanderen. 20 jaar investeren in kennispotentieel. Een analyse op basis van de HRRF-databank (1990–2009). Leuven: Academia Press.

Grote, D., Patrick, A., Lyles, C., Knight, D., Borrego, M., & Alsharif, A. (2021). STEM doctoral students’ skill development: Does funding mechanism matter? International Journal of STEM Education, 8 , 1–19.

Gu, J., He, C., & Liu, H. (2017). Supervisory styles and graduate student creativity: the mediating roles of creative self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation. Studies in Higher Education, 42 (4), 721–742.

Google Scholar

Heath, T. (2002). A quantitative analysis of PhD students’ views of supervision. Higher Education Research & Development, 21 (1), 41–53.

Holmwood, J. (2014). From social rights to the market: Neoliberalism and the knowledge economy. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 33 (1), 62–76.

Houston, D., Meyer, L. H., & Paewai, S. (2006). Academic staff workloads and job satisfaction: Expectations and values in academe. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 28 (1), 17–30.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6 (1), 1–55.

Jakubiec, B. A. E. (2015). Academic Motherhood:" Silver Linings and Clouds". Antistasis, 5 (2), 42–49.

Jucks, R., & Hillbrink, A. (2017). Perspective on research and teaching in psychology: Enrichment or burden? Psychology Learning & Teaching, 16 (3), 306–322.

Kinman, G., & Jones, F. (2008). A life beyond work? Job demands, work-life balance, and wellbeing in UK academics. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 17 (1–2), 41–60.

Kleiner, S. (2014). Subjective time pressure: General or domain specific? Social Science Research, 47 , 108–120.

Larivière, V. (2012). On the shoulders of students? The contribution of PhD students to the advancement of knowledge. Scientometrics, 90 , 463–481.

Lee, A. (2008). How are doctoral students supervised? Concepts of doctoral research supervision. Studies in Higher Education, 33 (3), 267–281.

Lee, M., Coutts, R., Fielden, J., Hutchinson, M., Lakeman, R., Mathisen, B., Nasrawi, D., & Phillips, N. (2022). Occupational stress in university academics in Australia and New Zealand. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 44 (1), 57–71.

Machette, A. T. (2021). Dialectical tensions of graduate teaching assistants. Texas Speech Communication Journal, 45 , 13–28.

Muzaka, V. (2009). The niche of graduate teaching assistants (GTAs): Perceptions and reflections. Teaching in Higher Education, 14 (1), 1–12.

Naylor, R., Chakravarti, S., & Baik, C. (2016). Differing motivations and requirements in PhD student cohorts: A case study. Issues Educ Res, 26 (2), 351–367.

Nature Research. (2022). Nature Careers Graduate Survey 2022. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21277575.v3

Park, C., & Ramos, M. (2002). The donkey in the department? Insights into the graduate teaching assistant (GTA) experience in the UK. Journal of Graduate Education, 3 (2), 47–53.

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P., & Piquero, A. (1998). Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology, 36 (4), 859–866.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48 , 1–36.

Sabagh, Z., Hall, N. C., & Saroyan, A. (2018). Antecedents, correlates and consequences of faculty burnout. Educational Research, 60 (2), 131–156.

Saks, A. M., & Gruman, J. A. (2014). What do we really know about employee engagement? Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25 (2), 155–182.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006a). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66 (4), 701–716.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006b). Utrecht work engagement scale-9 (UWES-9). APA PsycTests . https://doi.org/10.1037/t05561-000

Skakni, I. (2018). Reasons, motives and motivations for completing a PhD: A typology of doctoral studies as a quest. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 9 (2), 197–212.

Sonnentag, S., Mojza, E. J., Binnewies, C., & Scholl, A. (2008). Being engaged at work and detached at home: A week-level study on work engagement, psychological detachment, and affect. Work & Stress, 22 (3), 257–276.

Sonneveld, H., & Tigchelaar, A. (2009). Promovendi en het Onderwijs [PhD Students and Education] . http://www.phdcentre.eu/inhoud/uploads/2018/02/Promovendienhetonderwijs.pdf

Southerton, D. (2020). Time scarcity: Work, home and personal lives. In D. Southerton (Ed.), Time, consumption and the coordination of everyday life (pp. 43–67). Palgrave Macmillan.

Chapter Google Scholar

Sverdlik, A., Hall, N. C., McAlpine, L., & Hubbard, K. (2018). The PhD experience: A review of the factors influencing doctoral students’ completion, achievement, and well-being. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 13 , 361–388.

Tham, T. L., & Holland, P. (2018). What do business school academics want? Reflections from the national survey on workplace climate and well-being: Australia and New Zealand. Journal of Management & Organization, 24 (4), 492–499.

Toffoletti, K., & Starr, K. (2016). Women academics and work–life balance: Gendered discourses of work and care. Gender, Work & Organization, 23 (5), 489–504.

Torka, M. (2018). Projectification of doctoral training? How research fields respond to a new funding regime. Minerva, 56 (1), 59–83.

van Tienoven, T. P., Minnen, J., & Glorieux, I. (2017). The statistics of the time pressure scale . Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Research Group TOR.

van Tienoven, T. P., Glorieux, A., Minnen, J., Te Braak, P., & Spruyt, B. (2022). Graduate students locked down? PhD students’ satisfaction with supervision during the first and second COVID-19 lockdown in Belgium. PLoS ONE, 17 (5), e0268923.

Watts, J., & Robertson, N. (2011). Burnout in university teaching staff: A systematic literature review. Educational Research, 53 (1), 33–50.

Woolston, C. (2019). PhD poll reveals fear and joy, contentment and anguish. Nature, 575 , 403–406.

Woolston, C. (2022). Stress and uncertainty drag down graduate students’ satisfaction. Nature, 610 (7933), 805–808.

Zerubavel, E. (1985). Hidden rhythms: Schedules and calendars in social life . Berkeley: Univ of California Press.

Zhao, C. M., Golde, C. M., & McCormick, A. C. (2007). More than a signature: How advisor choice and advisor behaviour affect doctoral student satisfaction. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 31 (3), 263–281.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the members of the project steering committee for their constructive feedback on the ideas that led to this contribution. The responsibility for the content and any remaining errors remain exclusively with the authors.

This research is part of the project VUB PhD Survey funded by the Research Council of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Sociology Department, Research Group TOR, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Pleinlaan 2, 1050, Brussels, Belgium

Theun Pieter van Tienoven, Anaïs Glorieux, Joeri Minnen & Bram Spruyt

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Theun Pieter van Tienoven .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (PDF 97.3 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

van Tienoven, T.P., Glorieux, A., Minnen, J. et al. Caught between academic calling and academic pressure? Working time characteristics, time pressure and time sovereignty predict PhD students’ research engagement. High Educ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01096-8

Download citation

Accepted : 13 August 2023

Published : 08 September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01096-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Working hours

- Time pressure

- Time sovereignty

- Research engagement

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government.

Here’s how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Misclassification

- Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA)

- Pump at Work

- Maternal Health

- Retaliation

- Government Contracts

- Immigration

- Child Labor

- Agricultural Employment

- Subminimum Wage

- Employment of Workers With Disabilities

- Lie Detector Tests

- Davis Bacon Prevailing Wage Survey

- WORKER RIGHTS

- Resources For Employers

- Regulatory Library

- Interpretive Guidance

- Industry-Specific Resources

- Compliance Assistance

- elaws Advisors

- Fact Sheets

- New and Small Businesses Resources

- Presentations

- External User Portal (EUP)

- Compliance Assistance Toolkits

- New and Small Business Resources

- Publications By Language

- FLSA Compliance Videos

- Know Your Rights Video Series

- Employer.gov

- DOL Enforcement Database

- Workers Owed Wages

- Order Publications

- Laws and Regulations

- Field Handbook

- Administrator Interpretations, Opinion and Ruling Letters

- Field Bulletins

- State Minimum Wage Laws

- State Labor Law Topics

- State Labor Offices

- Resources for State and Local Governments

- NEWS RELEASES

WAGE AND HOUR DIVISION

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

Fact Sheet #17S: Higher Education Institutions and Overtime Pay Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

Revised September 2019

NOTICE: On August 30, 2023, the Department of Labor (Department) announced issuance of a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM), Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative, Professional, Outside Sales, and Computer Employees . The NPRM proposes to update and revise the regulations issued under section 13(a)(1) of the Fair Labor Standards Act implementing the exemption from minimum wage and overtime pay requirements for executive, administrative, and professional employees. Proposed revisions include increasing the standard salary level and the highly compensated employee total annual compensation threshold, as well as providing an automatic updating mechanism that would allow for the timely and efficient updating of all the thresholds to reflect current earnings data.

This fact sheet provides information on the exemption from minimum wage and overtime pay provided by Sections 13(a)(1) of the FLSA as defined by Regulations, 29 C.F.R. Part 541 and discusses the applicability of such exemptions to employees in jobs that are common in higher education institutions.

The FLSA requires that most employees in the United States be paid at least the federal minimum wage for all hours worked and overtime pay at not less than time and one-half the regular rate of pay for all hours worked over 40 hours in a workweek.

However, Section 13(a)(1) of the FLSA provides an exemption from both minimum wage and overtime pay for employees employed as bona fide executive , administrative , professional and outside sales employees. Section 13(a)(1) and Section 13(a)(17) also exempts certain computer employees. These exemptions are often called the “white-collar” exemptions.

General Requirements for Exemptions

To qualify for a white-collar exemption, an employee must generally satisfy three tests:

- The employee must be paid on a salary basis that is not subject to reduction based on the quality or quantity of work (the “ salary basis test ”), rather than, for example, on an hourly basis;

- The employee must receive a salary at a rate not less than $684 * per week (the “ salary level test ”); and

- The employee’s primary duty must involve the kind of work associated with the exempt status sought, such as executive, administrative, or professional work (the “ duties test ”).

Additional information concerning these exemptions is available in Fact Sheets 17A-G. See

- https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/regs/compliance/whdcomp .

Exemptions for Common Higher Education Jobs

A teacher is exempt if his or her primary duty is teaching, tutoring, instructing, or lecturing to impart knowledge, and if he or she is performing that duty as an employee of an educational establishment. See 29 C.F.R. § 541.303 . Educational establishments include elementary school systems, secondary school systems, institutions of higher education, and other educational institutions. See 29 C.F.R. § 541.204(b) . If a bona fide teacher meets this duty requirement, the salary level and salary basis tests do not apply. See 29 C.F.R. §§ 541.303(d) , 541.600(e) . Given these standards, professors, instructors, and adjunct professors typically qualify for this exemption.

A faculty member who teaches online or remotely also may qualify for this exemption. The regulations do not restrict where bona fide teaching may take place, to whom the knowledge can be imparted, or how many hours a teacher must work per week to qualify for the exemption. The exemption would therefore ordinarily apply, for example, to a part-time faculty member of an educational establishment whose primary duty is to provide instruction through online courses to remote non-credit learners. The exemption could likewise apply, for example, to an agricultural extension agent who is employed by an educational establishment to travel and provide instruction to farmers, if the agent’s primary duty is teaching, instructing, or lecturing to impart knowledge. To determine a teacher’s primary duty, the relevant inquiry in all cases is the teacher’s actual job duties. Job titles or full/part-time status alone do not determine exempt status.

A teacher does not become nonexempt merely because he or she spends a considerable amount of time in extracurricular activities (such as coaching athletic teams or supervising student clubs), provided the teacher’s primary duty is teaching.

Athletic coaches employed by higher education institutions may qualify for the teacher exemption. After all, teaching may include instructing student-athletes in how to perform their sport. But a coach will not qualify for the exemption if his or her primary duties are recruiting students to play sports or visiting high schools and athletic camps to conduct student interviews. The amount of time the coach spends instructing student-athletes in a team sport is relevant, but not the exclusive factor, in determining the coach’s exempt status.

Professional Employees

The FLSA provides for several kinds of exempt professional employees—such as learned professionals, creative professionals, teachers, and employees practicing law or medicine. In higher education, employees eligible for the professional exemption are often either teachers (as discussed above) or learned professionals (as described below). To qualify as a learned professional, the employee must satisfy three requirements:

- The employee’s primary duty must be the performance of work requiring advanced knowledge;

- The advanced knowledge must be in a field of science or learning; and

- The advanced knowledge must be customarily acquired by a prolonged course of specialized intellectual instruction.

See 29 C.F.R. § 541.301 . Unless the employee is a teacher or practicing law or medicine, he or she must also satisfy the above-referenced salary basis and salary level tests to be an exempt professional.

In higher education, examples of exempt non-teacher learned professionals generally include certified public accountants, psychologists, certified athletic trainers, and librarians. Postdoctoral fellows, who conduct research at a higher education institution after completing their doctoral studies, likewise generally meet the duties requirements of the learned professional exemption, and they may additionally qualify for the teacher exemption if teaching is their primary duty. Of course, an employee’s qualification for the exemption depends on his or her actual job duties and education. Job titles alone are not sufficient for determining whether an employee satisfies the duties test.

Administrative Employees

Various employees at higher educational institutions may qualify as exempt administrative employees. The administrative exemption applies when the following requirements are met:

- The employee’s compensation must satisfy the above-referenced salary basis and salary level tests;

- The employee’s primary duty must be the performance of office or non-manual work directly related to the management or general business operations of the employer or the employer’s customers; and

- The employee’s primary duty must include the exercise of discretion and independent judgment with respect to matters of significance.

See 29 C.F.R. § 541.200 . Such administrative employees in higher education might include, for example, admissions counselors or student financial aid officers. An employee’s qualification for the exemption depends on his or her actual job duties; job titles alone are not sufficient for determining whether an employee satisfies the duties test.

Notably, there are specific regulatory provisions for certain administrative employees—known as “academic administrative employees”—whose primary duty is performing administrative functions directly related to academic instruction or training in an educational establishment. To be exempt as an academic administrative professional:

- The employee must satisfy the above-referenced salary basis and salary level tests or receive a salary of at least the entrance salary for teachers in the same educational establishment; and

- The employee’s primary duty must be to perform administrative functions directly related to academic instruction or training in an educational establishment.

See 29 C.F.R. § 541.204 . Employees who work in higher education but whose work does not relate to the educational field (such as work in general business operations) do not qualify as exempt academic administrative employees. See id.

In higher education institutions, exempt academic administrative personnel generally include department heads, intervention specialists who are available to respond to student academic issues, and other employees with similar responsibilities. Exempt administrative personnel would likewise generally include academic counselors who administer school testing programs, assist students with academic problems, and advise students concerning degree requirements. Again, whether an employee satisfies the duties test for these exemptions depends on the employee’s actual job duties, not just the employee’s job title.

Executive Employees

To qualify for the executive exemption, an employee must satisfy the following tests:

- The employee must receive compensation that satisfies the above-referenced salary basis and salary level tests;

- The employee’s primary duty must be managing the enterprise or a customarily recognized department or subdivision thereof;

- The employee must customarily and regularly direct the work of at least two or more other full-time employees or their equivalent (for example, one full-time and two half-time employees); and

- The employee must have the authority to hire or fire other employees, or in the alternative, the employee’s suggestions and recommendations as to the hiring, firing, advancement, promotion, or any other change of status of other employees must be given particular weight.

See 29 C.F.R. § 541.100 . Various positions in higher education institutions might qualify for the executive exemption, including deans, department heads, directors, and any other manager or supervisor whose job duties and compensation satisfy the above criteria.

Student-Employees

As a general matter, most students who work for their college or university are hourly non-exempt workers and do not work more than 40 hours per week. The following, however, are examples of students who often receive a salary or other non-hourly compensation:

- Graduate Teaching Assistants. Graduate teaching assistants whose primary duty is teaching are exempt. Because they qualify for the teacher exemption, they are not subject to the salary basis and salary level tests.

- Research Assistants. Generally, an educational relationship exists when a graduate or undergraduate student performs research under a faculty member’s supervision while obtaining a degree. Under these circumstances, the Department would not assert that an employment relationship exists with either the school or any grantor funding the student’s research. This is true even though the student may receive a stipend for performing the research.

- Student Residential Assistants. Students enrolled in bona fide educational programs who are residential assistants and receive reduced room or board charges or tuition credits are not generally considered employees under the FLSA. They therefore are not entitled to minimum wages and overtime under the FLSA.

An employment relationship will generally exist when a student receives compensation and his or her duties are not part of an overall education program. For example, students who work at food service counters, sell programs or usher at events, or wash dishes in dining halls and anticipate some compensation (for example, money or meals) are generally considered employees entitled to minimum wage and overtime compensation.

Compensatory Time at Public Universities

Public universities or colleges that qualify as a “public agency” under the FLSA may compensate nonexempt employees with compensatory time off (or “comp time”) in lieu of overtime pay. A college or university is a public agency under the FLSA if it is a political subdivision of a State. When determining whether a college or university is a “political subdivision,” the Department considers whether (1) the State directly created the entity, or (2) individuals administering the entity are responsible to public officials or the general electorate.

If the public university or college qualifies as a public agency, nonexempt employees generally may not accrue more than 240 hours of comp time. However, employees engaged to work in a public safety activity, an emergency response activity, or a seasonal activity may accrue as much as 480 hours of comp time. See 29 U.S.C. 207(o)(3)(A). Private higher education institutions may not pay employees comp time in lieu of overtime pay.

Where to Obtain Additional Information

For additional information, visit our Wage and Hour Division Website: http://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd and/or call our toll-free information and helpline, available 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. in your time zone, 1-866-4USWAGE (1-866-487-9243).

This publication is for general information and is not to be considered in the same light as official statements of position contained in the regulations.

The contents of this document do not have the force and effect of law and are not meant to bind the public in any way. This document is intended only to provide clarity to the public regarding existing requirements under the law or agency policies.

Want to Get your Dissertation Accepted?

Discover how we've helped doctoral students complete their dissertations and advance their academic careers!

Join 200+ Graduated Students

Get Your Dissertation Accepted On Your Next Submission

Get customized coaching for:.

- Crafting your proposal,

- Collecting and analyzing your data, or

- Preparing your defense.

Trapped in dissertation revisions?

What is the life of a phd student really like, published by steve tippins on june 9, 2020 june 9, 2020.

Last Updated on: 2nd February 2024, 05:11 am

Life of a PhD student? Hell. That about sums it up.

Okay, that’s not a very satisfying answer. Nor is it completely true. Life as a PhD student doesn’t always feel like hell. It does sometimes, but it’s also an exhilarating and rewarding time to explore your area of interest and grow into a true scholar. So what does the life of a PhD student really look like?

The life of a PhD student is somewhat varied depending on the field you’re going into. Generally speaking, no matter what program you’re in, it has two phases: coursework and dissertation.

Coursework Phase

Doctoral-level are courses that are a lot harder than undergraduate or even Master’s courses , but they are similar in structure: there’s a syllabus, due dates, other students in the class, etc. There are definitive semesters, quarters, or terms. In between terms, there’s really not much work to do.

Of course, there are different expectations for PhD students than for undergrads. They are held to a far more rigorous standard in the work that they do. Class sizes are much smaller, and students are expected to participate in nuanced discussions. There is no sliding by unnoticed in a PhD program.

All that said, the coursework phase of the life of a PhD student is not altogether different than their previous educational experience, besides being more rigorous. It’s like school on steroids.

Depending on the school, there may be a transition from classwork: comprehensive exams. This is basically, “study everything you’ve learned so that you can be ready for any question.”

Dissertation Phase

The dissertation phase is a world in which there’s no syllabus, no classmates, and no real structure. You have your Chairperson and Committee to keep happy, but they’re not pushing you forward or expecting you to turn things in by a certain date. They’re just waiting for you to do what you have to do.

Once you get to the dissertation stage, the concept of semesters and quarters goes away, and you’re working on your topic all the time.