Founders Online --> [ Back to normal view ]

The federalist number 10, [22 november] 1787, the federalist number 10.

[22 November 1787]

Among the numerous advantages promised by a well constructed union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction. 1 The friend of popular governments, never finds himself so much alarmed for their character and fate, as when he contemplates their propensity to this dangerous vice. He will not fail therefore to set a due value on any plan which, without violating the principles to which he is attached, provides a proper cure for it. The instability, injustice and confusion introduced into the public councils, have in truth been the mortal diseases under which popular governments have every where perished; as they continue to be the favorite and fruitful topics from which the adversaries to liberty derive their most specious declamations. The valuable improvements made by the American constitutions on the popular models, both antient and modern, cannot certainly be too much admired; but it would be an unwarrantable partiality, to contend that they have as effectually obviated the danger on this side as was wished and expected. Complaints are every where heard from our most considerate and virtuous citizens, equally the friends of public and private faith, and of public and personal liberty; that our governments are too unstable; that the public good is disregarded in the conflicts of rival parties; and that measures are too often decided, not according to the rules of justice, and the rights of the minor party; but by the superior force of an interested and over-bearing majority. However anxiously we may wish that these complaints had no foundation, the evidence of known facts will not permit us to deny that they are in some degree true. It will be found indeed, on a candid review of our situation, that some of the distresses under which we labour, have been erroneously charged on the operation of our governments; but it will be found at the same time, that other causes will not alone account for many of our heaviest misfortunes; and particularly, for that prevailing and increasing distrust of public engagements, and alarm for private rights, which are echoed from one end of the continent to the other. These must be chiefly, if not wholly, effects of the unsteadiness and injustice, with which a factious spirit has tainted our public administration.

By a faction I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.

There are two methods of curing the mischiefs of faction: The one, by removing its causes; the other, by controlling its effects.

There are again two methods of removing the causes of faction: The one by destroying the liberty which is essential to its existence; the other, by giving to every citizen the same opinions, the same passions, and the same interests.

It could never be more truly said than of the first remedy, that it is worse than the disease. Liberty is to faction, what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires. But it could not be a less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life, because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life because it imparts to fire its destructive agency.

The second expedient is as impracticable, as the first would be unwise. As long as the reason of man continues fallible, and he is at liberty to exercise it, different opinions will be formed. As long as the connection subsists between his reason and his self-love, his opinions and his passions will have a reciprocal influence on each other; and the former will be objects to which the latter will attach themselves. The diversity in the faculties of men from which the rights of property originate, is not less an insuperable obstacle to an uniformity of interests. The protection of these faculties is the first object of government. From the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, the possession of different degrees and kinds of property immediately results: And from the influence of these on the sentiments and views of the respective proprietors, ensues a division of the society into different interests and parties.

The latent causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of man; and we see them every where brought into different degrees of activity, according to the different circumstances of civil society. A zeal for different opinions concerning religion, concerning government, and many other points, as well of speculation as of practice; an attachment to different leaders ambitiously contending for pre-eminence and power; or to persons of other descriptions whose fortunes have been interesting to the human passions, have in turn divided mankind into parties, inflamed them with mutual animosity, and rendered them much more disposed to vex and oppress each other, than to co-operate for their common good. So strong is this propensity of mankind to fall into mutual animosities, that where no substantial occasion presents itself, the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions have been sufficient to kindle their unfriendly passions, and excite their most violent conflicts. But the most common and durable source of factions, has been the various and unequal distribution of property. Those who hold, and those who are without property, have ever formed distinct interests in society. Those who are creditors, and those who are debtors, fall under a like discrimination. A landed interest, a manufacturing interest, a mercantile interest, a monied interest, with many lesser interests, grow up of necessity in civilized nations, and divide them into different classes, actuated by different sentiments and views. The regulation of these various and interfering interests forms the principal task of modern legislation, and involves the spirit of party and faction in the necessary and ordinary operations of government.

No man is allowed to be a judge in his own cause; because his interest would certainly bias his judgment, and, not improbably, corrupt his integrity. With equal, nay with greater reason, a body of men, are unfit to be both judges and parties, at the same time; yet, what are many of the most important acts of legislation, but so many judicial determinations, not indeed concerning the rights of single persons, but concerning the rights of large bodies of citizens; and what are the different classes of legislators, but advocates and parties to the causes which they determine? Is a law proposed concerning private debts? It is a question to which the creditors are parties on one side, and the debtors on the other. Justice ought to hold the balance between them. Yet the parties are and must be themselves the judges; and the most numerous party, or, in other words, the most powerful faction must be expected to prevail. Shall domestic manufactures be encouraged, and in what degree, by restrictions on foreign manufactures? are questions which would be differently decided by the landed and the manufacturing classes; and probably by neither, with a sole regard to justice and the public good. The apportionment of taxes on the various descriptions of property, is an act which seems to require the most exact impartiality, yet there is perhaps no legislative act in which greater opportunity and temptation are given to a predominant party, to trample on the rules of justice. Every shilling with which they over-burden the inferior number, is a shilling saved to their own pockets.

It is in vain to say, that enlightened statesmen will be able to adjust these clashing interests, and render them all subservient to the public good. Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm: Nor, in many cases, can such an adjustment be made at all, without taking into view indirect and remote considerations, which will rarely prevail over the immediate interest which one party may find in disregarding the rights of another, or the good of the whole.

The inference to which we are brought, is, that the causes of faction cannot be removed; and that relief is only to be sought in the means of controlling its effects .

If a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views by regular vote: It may clog the administration, it may convulse the society; but it will be unable to execute and mask its violence under the forms of the constitution. When a majority is included in a faction, the form of popular government on the other hand enables it to sacrifice to its ruling passion or interest, both the public good and the rights of other citizens. To secure the public good, and private rights against the danger of such a faction, and at the same time to preserve the spirit and the form of popular government, is then the great object to which our enquiries are directed. Let me add that it is the great desideratum, by which alone this form of government can be rescued from the opprobrium under which it has so long labored, and be recommended to the esteem and adoption of mankind.

By what means is this object attainable? Evidently by one of two only. Either the existence of the same passion or interest in a majority at the same time, must be prevented; or the majority, having such co-existent passion or interest, must be rendered, by their number and local situation, unable to concert and carry into effect schemes of oppression. If the impulse and the opportunity be suffered to coincide, we well know that neither moral nor religious motives can be relied on as an adequate control. They are not found to be such on the injustice and violence of individuals, and lose their efficacy in proportion to the number combined together; that is, in proportion as their efficacy becomes needful. 2

From this view of the subject, it may be concluded that a pure democracy, by which I mean a society, consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole; a communication and concert results from the form of government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party, or an obnoxious individual. Hence it is, that such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security, or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives, as they have been violent in their deaths. Theoretic politicians, who have patronized this species of government, have erroneously supposed, that by reducing mankind to a perfect equality in their political rights, they would, at the same time, be perfectly equalized, and assimilated in their possessions, their opinions, and their passions.

A republic, by which I mean a government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for which we are seeking. Let us examine the points in which it varies from pure democracy, and we shall comprehend both the nature of the cure, and the efficacy which it must derive from the union.

The two great points of difference between a democracy and a republic, are first, the delegation of the government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended.

The effect of the first difference is, on the one hand, to refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice, will be least likely to sacrifice it to temporary or partial considerations. Under such a regulation, it may well happen that the public voice pronounced by the representatives of the people, will be more consonant to the public good, than if pronounced by the people themselves convened for the purpose. On the other hand, the effect may be inverted. Men of factious tempers, of local prejudices, or of sinister designs, may by intrigue, by corruption, or by other means, first obtain the suffrages, and then betray the interests of the people. The question resulting is, whether small or extensive republics are most favourable to the election of proper guardians of the public weal; and it is clearly decided in favour of the latter by two obvious considerations.

In the first place it is to be remarked, that however small the republic may be, the representatives must be raised to a certain number, in order to guard against the cabals of a few; and that however large it may be, they must be limited to a certain number, in order to guard against the confusion of a multitude. Hence the number of representatives in the two cases not being in proportion to that of the constituents, and being proportionally greatest in the small republic, it follows, that if the proportion of fit characters be not less in the large than in the small republic, the former will present a greater option, and consequently a greater probability of a fit choice.

In the next place, as each representative will be chosen by a greater number of citizens in the large than in the small republic, it will be more difficult for unworthy candidates to practise with success the vicious arts, by which elections are too often carried; and the suffrages of the people being more free, will be more likely to centre on men who possess the most attractive merit, and the most diffusive and established characters.

It must be confessed, that in this, as in most other cases, there is a mean, on both sides of which inconveniencies will be found to lie. By enlarging too much the number of electors, you render the representative too little acquainted with all their local circumstances and lesser interests; as by reducing it too much, you render him unduly attached to these, and too little fit to comprehend and pursue great and national objects. The federal constitution forms a happy combination in this respect; the great and aggregate interests being referred to the national, the local and particular to the state legislatures.

The other point of difference is, the greater number of citizens and extent of territory which may be brought within the compass of republican, than of democratic government; and it is this circumstance principally which renders factious combinations less to be dreaded in the former, than in the latter. The smaller the society, the fewer probably will be the distinct parties and interests composing it; the fewer the distinct parties and interests, the more frequently will a majority be found of the same party; and the smaller the number of individuals composing a majority, and the smaller the compass within which they are placed, the more easily will they concert and execute their plans of oppression. Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other. Besides other impediments, it may be remarked, that where there is a consciousness of unjust or dishonourable purposes, communication is always checked by distrust, in proportion to the number whose concurrence is necessary.

Hence it clearly appears, that the same advantage, which a republic has over a democracy, in controlling the effects of faction, is enjoyed by a large over a small republic—is enjoyed by the union over the states composing it. Does this advantage consist in the substitution of representatives, whose enlightened views and virtuous sentiments render them superior to local prejudices, and to schemes of injustice? It will not be denied, that the representation of the union will be most likely to possess these requisite endowments. Does it consist in the greater security afforded by a greater variety of parties, against the event of any one party being able to outnumber and oppress the rest? In an equal degree does the encreased variety of parties, comprised within the union, encrease this security. Does it, in fine, consist in the greater obstacles opposed to the concert and accomplishment of the secret wishes of an unjust and interested majority? Here, again, the extent of the union gives it the most palpable advantage.

The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular states, but will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other states: A religious sect, may degenerate into a political faction in a part of the confederacy; but the variety of sects dispersed over the entire face of it, must secure the national councils against any danger from that source: A rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project, will be less apt to pervade the whole body of the union, than a particular member of it; in the same proportion as such a malady is more likely to taint a particular county or district, than an entire state. 3

In the extent and proper structure of the union, therefore, we behold a republican remedy for the diseases most incident to republican government. And according to the degree of pleasure and pride, we feel in being republicans, ought to be our zeal in cherishing the spirit, and supporting the character of federalists.

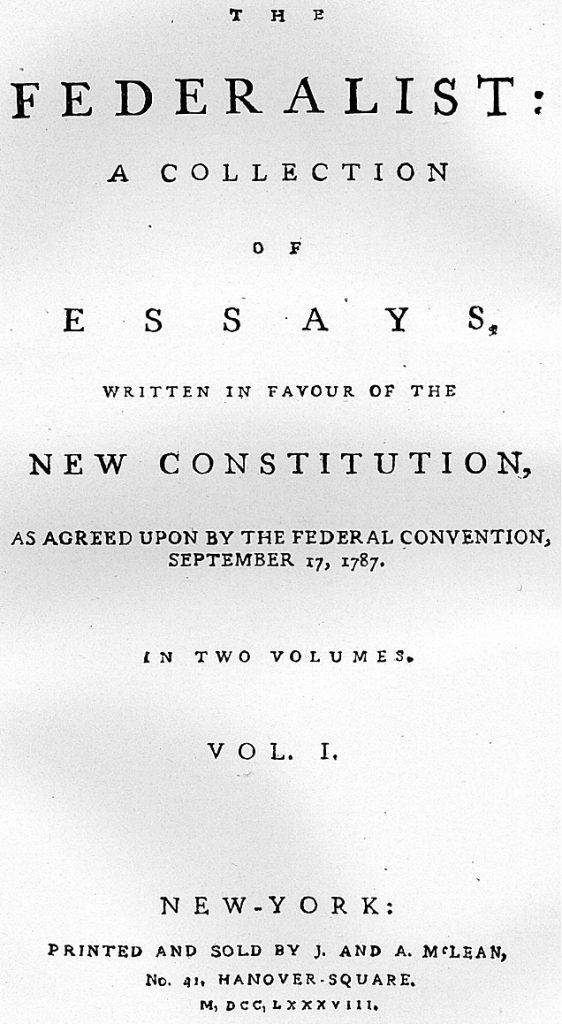

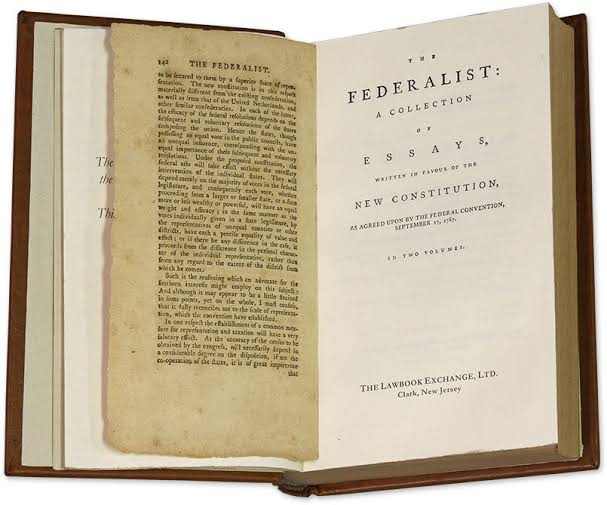

McLean description begins The Federalist, A Collection of Essays, written in favour of the New Constitution, By a Citizen of New-York. Printed by J. and A. McLean (New York, 1788). description ends , I, 52–61.

1 . Douglass Adair showed chat in preparing this essay, especially that part containing the analysis of factions and the theory of the extended republic, JM creatively adapted the ideas of David Hume (“‘That Politics May Be Reduced to a Science’: David Hume, James Madison, and the Tenth Federalist,” Huntington Library Quarterly , XX [1956–57], 343–60). The forerunner of The Federalist No. 10 may be found in JM’s Vices of the Political System ( PJM description begins William T. Hutchinson et al., eds., The Papers of James Madison (10 vols. to date; Chicago, 1962——). description ends , IX, 348–57 ). See also JM’s first speech of 6 June and his first speech of 26 June 1787 at the Federal Convention, and his letter to Jefferson of 24 Oct. 1787 .

2 . In Vices of the Political System JM listed three motives, each of which he believed was insufficient to prevent individuals or factions from oppressing each other: (1) “a prudent regard to their own good as involved in the general and permanent good of the Community”; (2) “respect for character”; and (3) religion. As to “respect for character,” JM remarked that “in a multitude its efficacy is diminished in proportion to the number which is to share the praise or the blame” ( PJM description begins William T. Hutchinson et al., eds., The Papers of James Madison (10 vols. to date; Chicago, 1962——). description ends , IX, 355–56 ). For this observation JM again drew upon David Hume. Adair suggests that JM deliberately omitted his list of motives from The Federalist . “There was a certain disadvantage in making derogatory remarks to a majority that must be persuaded to adopt your arguments” (“‘That Politics May Be Reduced to a Science,’” Huntington Library Quarterly , XX [1956–57], 354). JM repeated these motives in his first speech of 6 June 1787, in his letter to Jefferson of 24 Oct. 1787 , and alluded to them in The Federalist No. 51 .

3 . The negative on state laws, which JM had unsuccessfully advocated at the Federal Convention, was designed to prevent the enactment of “improper or wicked” measures by the states. The Constitution did include specific prohibitions on the state legislatures, but JM dismissed these as “short of the mark.” He also doubted that the judicial system would effectively “keep the States within their proper limits” ( JM to Jefferson, 24 Oct. 1787 ).

Index Entries

You are looking at.

Federalist 10

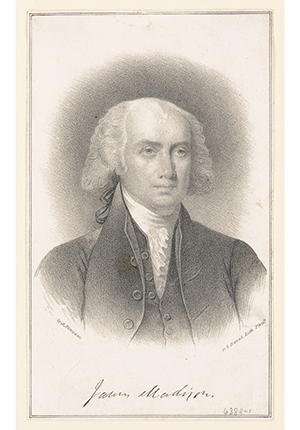

Written by James Madison, this Federalist 10 defended the form of republican government proposed by the Constitution . Critics of the Constitution argued that the proposed federal government was too large and would be unresponsive to the people.

PDF: Federalist Papers No 10

Writing Federalist Paper No 10

In response, Madison explored majority rule v. minority rights in this essay. He countered that it was exactly the great number of factions and diversity that would avoid tyranny. Groups would be forced to negotiate and compromise among themselves, arriving at solutions that would respect the rights of minorities. Further, he argued that the large size of the country would actually make it more difficult for factions to gain control over others. “The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular States, but will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other States.”

Federalist 10 | BRI’s Primary Source Essentials

Related Resources

James Madison

No other Founder had as much influence in crafting, ratifying, and interpreting the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights as he did. A skilled political tactician, Madison proved instrumental in determining the form of the early American republic.

Would you have been a Federalist or an Anti-Federalist?

Federalist or Anti-Federalist? Over the next few months we will explore through a series of eLessons the debate over ratification of the United States Constitution as discussed in the Federalist and Anti-Federalist papers. We look forward to exploring this important debate with you! One of the great debates in American history was over the ratification […]

Explore the Constitution

The constitution.

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, historic document, federalist 10 (1787).

James Madison | 1787

After the Constitutional Convention adjourned in September 1787, heated local debate followed on the merits of the Constitution. Each state was required to vote on ratification of the document. A series of articles signed “Publius” soon began in New York newspapers. These Federalist Papers strongly supported the Constitution and continued to appear through the summer of 1788. Hamilton organized them, and he and Madison wrote most of the series of eighty-five articles, with John Jay contributing five. These essays were read carefully and debated in newspapers, primarily in New York. The Federalist Papers have since taken on immense significance, as they have come to be seen as the definitive early exposition on the Constitution’s meaning and giving us the main arguments for our form of government. In Federalist 10, Madison fulfills the promise made in Federalist No. 9 to demonstrate the utility of the proposed union in overcoming the problem of faction. Madison’s argument is the most systematic argument presented in the Federalist Papers , with syllogistically developed reasoning sustained virtually throughout.

Selected by

William B. Allen

Emeritus Dean of James Madison College and Emeritus Professor of Political Science at Michigan State University

Jonathan Gienapp

Associate Professor of History at Stanford University

Among the numerous advantages promised by a well-constructed Union, none deserves to be more accurately developed than its tendency to break and control the violence of faction. The friend of popular governments never finds himself so much alarmed for their character and fate, as when he contemplates their propensity to this dangerous vice. …

The valuable improvements made by the American constitutions on the popular models, both ancient and modern, cannot certainly be too much admired; but it would be an unwarranted partiality, to contend that they have as effectually obviated the danger on this side, as was wished and expected. Complaints are everywhere heard from our most considerate and virtuous citizens, equally the friends of public and private faith, and of public and personal liberty, that our governments are too unstable; that the public good is disregarded in the conflicts of rival parties; and that measures are too often decided, not according to the rules of justice, and the rights of the minor party, but by the superior force of an interested and overbearing majority. These must be chiefly, if not wholly, effects of the unsteadiness and injustice, with which a factious spirit has tainted our public administrations.

By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.

There are two methods of curing the mischiefs of faction. The one, by removing its causes; the other, by controlling its effects. There are again two methods of removing the causes of faction. The one, by destroying the liberty which is essential to its existence; the other, by giving to every citizen the same opinions, the same passions, and the same interests.

It could never be more truly said, than of the first remedy, that it is worse than the disease. Liberty is to faction what air is to fire, an aliment without which it instantly expires. But it would not be a less folly to abolish liberty, which is essential to political life because it nourishes faction, than it would be to wish the annihilation of air, which is essential to animal life, because it imparts to fire its destructive agency.

The second expedient is as impracticable, as the first would be unwise. As long as the reason of man continues fallible, and he is at liberty to exercise it, different opinions will be formed. As long as the connection subsists between his reason and his selflove, his opinions and his passions will have a reciprocal influence on each other; and the former will be objects to which the latter will attach themselves. The diversity in the faculties of men, from which the rights of property originate, is not less an insuperable obstacle to an uniformity of interests. The protection of those faculties is the first object of government. From the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, the possession of different degrees and kinds of property immediately results; and from the influence of these on the sentiments and views of the respective proprietors, ensues a division of the society into different interests and parties.

The latent causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of man; … and rendered them much more disposed to vex and oppress each other, than to co-operate for their common good. So strong is this propensity of mankind, to fall into mutual animosities, that where no substantial occasion presents itself, the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions have been sufficient to kindle their unfriendly passions and excite their most violent conflicts. But the most common and durable source of factions has been the various and unequal distribution of property. Those, who hold, and those who are without property, have ever formed distinct interests in society. Those who are creditors, and those who are debtors, fall into a like discrimination. A landed interest, a manufacturing interest, a mercantile interest, a moneyed interest, with many lesser interests, grow up of necessity in civilized nations, and divide them into different classes, actuated by different sentiments and views. The regulation of these various and interfering interests forms the principal task of modern legislation and involves the spirit of the party and faction in the necessary and ordinary operations of government. …

It is vain to say, that enlightened statesmen will be able to adjust these clashing interests and render them all subservient to the public good. Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm. …

The inference to which we are brought is, that the causes of faction cannot be removed; and that relief is only to be sought in the means of controlling its effects.

If a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat its sinister views, by regular vote. It may clog the administration; it may convulse the society; but it will be unable to execute and mask its violence under the forms of the constitution. When a majority is included in a faction, the form of popular government, on the other hand, enables it to sacrifice to its ruling passion or interest, both the public good and the rights of other citizens. To secure the public good, and private rights, against the danger of such a faction, and at the same time to preserve the spirit and the form of popular government, is the greatest object to which our inquiries are directed. ...

By what means is the object attainable? Evidently by one of two only. Either the existence of the same passion or interest in a majority, at the same time must be prevented; or the majority, having such coexistent passion or interest, must be rendered, by their number and local situation, unable to concert and carry into effect schemes of oppression. …

From this view of the subject, it may be concluded, that a pure democracy, by which I mean a society consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the government in person, can admit of no cure from the mischiefs of faction. …

A republic, by which I mean a government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for which we are seeking. Let us examine the points in which it varies from pure democracy, and we shall comprehend both the nature of the cure and the efficacy which it must derive from the union. The two great points of difference, between a democracy and a republic, are, first, the delegation of the government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the greater number of citizens, and the greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended.

The effect of the first difference is, on the one hand, to refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice, will be least likely to sacrifice it to temporary or partial considerations. Under such a regulation, it may well happen, that the public voice, pronounced by the representatives of the people, will be more consonant to the public good, than if pronounced by the people themselves, convened for the purpose.... The question resulting is, whether small or extensive republics are most favorable to the election of proper guardians of the public weal; and it is clearly decided in favor of the latter by two obvious considerations.

In the first place, it is to be remarked, that however small the republic may be, the representatives must be raised to a certain number, in order to guard against the cabals of a few; and that however large it may be, they must be limited to a certain number, in order to guard against the confusion of a multitude. Hence, the number of representatives in the two cases not being in proportion to that of the constituents, and being proportionately greatest in the small republic, it follows that if the proportion of fit characters be not less in the large than in the small republic, the former will present a greater probability of a fit choice.

In the next place, as each representative will be chosen by a greater number of citizens in the large than in the small republic, it will be more difficult for unworthy candidates to practice with success the vicious arts, by which elections are too often carried; and the suffrages of the people being more free, will be more likely to center in men who possess the most attractive merit, and the most diffusive and established characters. …

The other point of difference is, the greater number of citizens, and extent of territory, which may be brought within the compass of republican, than of democratic government; and it is this circumstance principally which renders factious combinations less to be dreaded in the former, than in the latter. .. Extend the sphere, and you will take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other. …

Hence, it clearly appears, that the same advantage, which a republic has over a democracy, in controlling the effects of faction, is enjoyed by a large over a small republic - enjoyed by the union over the states composing it. …

In the extent and proper structure of the union, therefore, we behold a republican remedy for the diseases most incident to republican government.

Explore the full document

Modal title.

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

US government and civics

Course: us government and civics > unit 10.

- The Declaration of Independence

- The Articles of Confederation

- The Constitution of the United States

Federalist No. 10

- Brutus No. 1

- Federalist No. 51

- Federalist No. 70

- Federalist No. 78

- Letter from a Birmingham Jail

The Same Subject Continued

The union as a safeguard against domestic faction and insurrection, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Federalist Papers

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 22, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Federalist Papers are a collection of essays written in the 1780s in support of the proposed U.S. Constitution and the strong federal government it advocated. In October 1787, the first in a series of 85 essays arguing for ratification of the Constitution appeared in the Independent Journal , under the pseudonym “Publius.” Addressed to “The People of the State of New York,” the essays were actually written by the statesmen Alexander Hamilton , James Madison and John Jay . They would be published serially from 1787-88 in several New York newspapers. The first 77 essays, including Madison’s famous Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 , appeared in book form in 1788. Titled The Federalist , it has been hailed as one of the most important political documents in U.S. history.

Articles of Confederation

As the first written constitution of the newly independent United States, the Articles of Confederation nominally granted Congress the power to conduct foreign policy, maintain armed forces and coin money.

But in practice, this centralized government body had little authority over the individual states, including no power to levy taxes or regulate commerce, which hampered the new nation’s ability to pay its outstanding debts from the Revolutionary War .

In May 1787, 55 delegates gathered in Philadelphia to address the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation and the problems that had arisen from this weakened central government.

A New Constitution

The document that emerged from the Constitutional Convention went far beyond amending the Articles, however. Instead, it established an entirely new system, including a robust central government divided into legislative , executive and judicial branches.

As soon as 39 delegates signed the proposed Constitution in September 1787, the document went to the states for ratification, igniting a furious debate between “Federalists,” who favored ratification of the Constitution as written, and “Antifederalists,” who opposed the Constitution and resisted giving stronger powers to the national government.

The Rise of Publius

In New York, opposition to the Constitution was particularly strong, and ratification was seen as particularly important. Immediately after the document was adopted, Antifederalists began publishing articles in the press criticizing it.

They argued that the document gave Congress excessive powers and that it could lead to the American people losing the hard-won liberties they had fought for and won in the Revolution.

In response to such critiques, the New York lawyer and statesman Alexander Hamilton, who had served as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention, decided to write a comprehensive series of essays defending the Constitution, and promoting its ratification.

Who Wrote the Federalist Papers?

As a collaborator, Hamilton recruited his fellow New Yorker John Jay, who had helped negotiate the treaty ending the war with Britain and served as secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation. The two later enlisted the help of James Madison, another delegate to the Constitutional Convention who was in New York at the time serving in the Confederation Congress.

To avoid opening himself and Madison to charges of betraying the Convention’s confidentiality, Hamilton chose the pen name “Publius,” after a general who had helped found the Roman Republic. He wrote the first essay, which appeared in the Independent Journal, on October 27, 1787.

In it, Hamilton argued that the debate facing the nation was not only over ratification of the proposed Constitution, but over the question of “whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

After writing the next four essays on the failures of the Articles of Confederation in the realm of foreign affairs, Jay had to drop out of the project due to an attack of rheumatism; he would write only one more essay in the series. Madison wrote a total of 29 essays, while Hamilton wrote a staggering 51.

Federalist Papers Summary

In the Federalist Papers, Hamilton, Jay and Madison argued that the decentralization of power that existed under the Articles of Confederation prevented the new nation from becoming strong enough to compete on the world stage or to quell internal insurrections such as Shays’s Rebellion .

In addition to laying out the many ways in which they believed the Articles of Confederation didn’t work, Hamilton, Jay and Madison used the Federalist essays to explain key provisions of the proposed Constitution, as well as the nature of the republican form of government.

'Federalist 10'

In Federalist 10 , which became the most influential of all the essays, Madison argued against the French political philosopher Montesquieu ’s assertion that true democracy—including Montesquieu’s concept of the separation of powers—was feasible only for small states.

A larger republic, Madison suggested, could more easily balance the competing interests of the different factions or groups (or political parties ) within it. “Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests,” he wrote. “[Y]ou make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens[.]”

After emphasizing the central government’s weakness in law enforcement under the Articles of Confederation in Federalist 21-22 , Hamilton dove into a comprehensive defense of the proposed Constitution in the next 14 essays, devoting seven of them to the importance of the government’s power of taxation.

Madison followed with 20 essays devoted to the structure of the new government, including the need for checks and balances between the different powers.

'Federalist 51'

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison wrote memorably in Federalist 51 . “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”

After Jay contributed one more essay on the powers of the Senate , Hamilton concluded the Federalist essays with 21 installments exploring the powers held by the three branches of government—legislative, executive and judiciary.

Impact of the Federalist Papers

Despite their outsized influence in the years to come, and their importance today as touchstones for understanding the Constitution and the founding principles of the U.S. government, the essays published as The Federalist in 1788 saw limited circulation outside of New York at the time they were written. They also fell short of convincing many New York voters, who sent far more Antifederalists than Federalists to the state ratification convention.

Still, in July 1788, a slim majority of New York delegates voted in favor of the Constitution, on the condition that amendments would be added securing certain additional rights. Though Hamilton had opposed this (writing in Federalist 84 that such a bill was unnecessary and could even be harmful) Madison himself would draft the Bill of Rights in 1789, while serving as a representative in the nation’s first Congress.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Ron Chernow, Hamilton (Penguin, 2004). Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010). “If Men Were Angels: Teaching the Constitution with the Federalist Papers.” Constitutional Rights Foundation . Dan T. Coenen, “Fifteen Curious Facts About the Federalist Papers.” University of Georgia School of Law , April 1, 2007.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The Federalist Papers

By alexander hamilton , james madison , john jay, the federalist papers summary and analysis of essay 10.

Madison begins perhaps the most famous essay of The Federalist Papers by stating that one of the strongest arguments in favor of the Constitution is the fact that it establishes a government capable of controlling the violence and damage caused by factions. Madison defines factions as groups of people who gather together to protect and promote their special economic interests and political opinions. Although these factions are at odds with each other, they frequently work against the public interest and infringe upon the rights of others.

Both supporters and opponents of the plan are concerned with the political instability produced by rival factions. The state governments have not succeeded in solving this problem; in fact, the situation is so problematic that people are disillusioned with all politicians and blame the government for their problems. Consequently, any form of popular government that can deal successfully with this problem has a great deal to recommend it.

Given the nature of man, factions are inevitable. As long as men hold different opinions, have different amounts of wealth, and own different amounts of property, they will continue to fraternize with those people who are most similar to them. Both serious and trivial reasons account for the formation of factions, but the most important source of faction is the unequal distribution of property. Men of greater ability and talent tend to possess more property than those of lesser ability, and since the first object of government is to protect and encourage ability, it follows that the rights of property owners must be protected. Property is divided unequally, and, in addition, there are many different kinds of property. Men have different interests depending upon the kind of property they own. For example, the interests of landowners differ from those of business owners. Governments must not only protect the conflicting interests of property owners but also must successfully regulate the conflicts between those with and without property.

To Madison, there are only two ways to control a faction: to remove its causes and to control its effects. There are only two ways to remove the causes of a faction: destroy liberty or give every citizen the same opinions, passions, and interests. Destroying liberty is a "cure worse then the disease itself," and the second is impracticable. The causes of factions are thus part of the nature of man, so we must accept their existence and deal with their effects. The government created by the Constitution controls the damage caused by such factions.

The framers established a representative form of government: a government in which the many elect the few who govern. Pure or direct democracies (countries in which all the citizens participate directly in making the laws) cannot possibly control factious conflicts. This is because the strongest and largest faction dominates and there is no way to protect weak factions against the actions of an obnoxious individual or a strong majority. Direct democracies cannot effectively protect personal and property rights and have always been characterized by conflict.

If the new plan of government is adopted, Madison hopes that the men elected to office will be wise and good men, the best of America. Theoretically, those who govern should be the least likely to sacrifice the public good for temporary conditions, but the opposite could happen. Men who are members of particular factions or who have prejudices or evil motives might manage, by intrigue or corruption, to win elections and then betray the interests of the people. However, the possibility of this happening in a large country, such as the United States, is greatly reduced. The likelihood that public offices will be held by qualified men is greater in large countries because there will be more representatives chosen by a greater number of citizens. This makes it more difficult for the candidates to deceive the people. Representative government is needed in large countries, not to protect the people from the tyranny of the few, but rather to guard against the rule of the mob.

In large republics, factions will be numerous, but they will be weaker than in small, direct democracies where it is easier for factions to consolidate their strength. In this country, leaders of factions may be able to influence state governments to support unsound economic and political policies as the states, far from being abolished, retain much of their sovereignty. If the framers had abolished the state governments, then opponents of the proposed government would have had a legitimate objection.

The immediate object of the constitution is to bring the present thirteen states into a secure union. Almost every state, old and new, will have one boundary next to territory owned by a foreign nation. The states farthest from the center of the country will be most endangered by these foreign countries; they may find it inconvenient to send representatives long distances to the capital, but in terms of safety and protection, they stand to gain the most from a strong national government.

Madison concludes that he presents these previous arguments because he is confident that many will not listen to those "prophets of gloom" who say that the proposed government is unworkable. For this founding father, it seems incredible that these gloomy voices suggest abandoning the idea of coming together in strength—after all, the states still have common interests. Madison concludes that "according to the degree of pleasure and pride we feel in being Republicans, ought to be our zeal in cherishing the spirit and supporting the character of Federalists."

James Madison carried to the Convention a plan that was the exact opposite of Hamilton's. In fact, the theory he advocated at Philadelphia and in his essays was developed as a republican substitute for the New Yorker's "high toned" scheme of state. Madison was convinced that the class struggle would be ameliorated in America by establishing a limited federal government that would make functional use of the vast size of the country and the existence of the states as active political organisms. He argued in his "Notes on Confederacy," in his Convention speeches, and again in Federalist 10 that if an extended republic were set up including a multiplicity of economic, geographic, social, religious, and sectional interests, then these interests, by checking each other, would prevent American society from being divided into the clashing armies of the rich and the poor. Thus, if no interstate proletariat could become organized on purely economic lines, the property of the rich would be safe even though the mass of the people held political power. Madison's solution for the class struggle was not to set up an absolute state to regiment society from above; he was never willing to sacrifice liberty to gain security. Rather, he wished to multiply the deposits of political power in the state itself to break down the dichotomy of rich and poor, thereby guaranteeing both liberty and security. This, as he stated in Federalist 10, would provide a "republican remedy for the diseases most incident to republican government."

It is also interesting to note that James Madison was the most creative and philosophical disciple of the Scottish school of science and politics in attendance at the Philadelphia Convention. His effectiveness as an advocate of a new constitution, and of the particular Constitution that was drawn up in Philadelphia in 1787, was based in a large part on his personal experience in public life and his personal knowledge of the conditions of American in 1787. But Madison's greatness as a statesman also rests in part on his ability to set his limited personal experience within the context of the experience of men in other ages and times, thus giving extra insight to his political formulations.

His most amazing political prophecy, contained within the pages of Federalist 10, was that the size of the United States and its variety of interests constituted a guarantee of stability and justice under the new Constitution. When Madison made this prophecy, the accepted opinion among all sophisticated politicians was exactly the opposite. It was David Hume's speculations on the "Idea of a Perfect Commonwealth," first published in 1752, that most stimulated James Madison's' thought on factions. In this essay, Hume decried any attempt to substitute a political utopia for "the common botched and inaccurate governments" which seemed to serve imperfect men so well. Nevertheless, he argued, the idea of a perfect commonwealth "is surely the most worthy curiosity of any the wit of man can possibly devise. And who knows, if this controversy were fixed by the universal consent of the wise and learned, but, in some future age, an opportunity might be afforded of reducing the theory to practice, either by a dissolution of some old government, or by the combination of men to form a new one, in some distant part of the world. " At the end of Hume's essay was a discussion that was of interest to Madison. The Scot casually demolished the Montesquieu small-republic theory; and it was this part of the essay, contained in a single page, that was to serve Madison in new-modeling a "botched" Confederation "in a distant part of the world." Hume said that "in a large government, which is modeled with masterly skill, there is compass and room enough to refine the democracy, from the lower people, who may be admitted into the first elections or first concoction of the commonwealth, to the higher magistrate, who direct all the movements. At the same time, the parts are so distant and remote, that it is very difficult, either by intrigue, prejudice, or passion, to hurry them into any measure against the public interest." Hume's analysis here had turned the small-territory republic theory upside down: if a free state could once be established in a large area, it would be stable and safe from the effects of faction. Madison had found the answer to Montesquieu. He had also found in embryonic form his own theory of the extended federal republic.

In Hume's essay lay the germ for Madison's theory of the extended republic. It is interesting to see how he took these scattered and incomplete fragments and built them into an intellectual and theoretical structure of his own. Madison's first full statement of this hypothesis appeared in his "Notes on the Confederacy" written in April 1787, eight months before the final version of it was published as the tenth Federalist. Starting with the proposition that "in republican Government, the majority, however, composed, ultimately give the law," Madison then asks what is to restrain an interested majority from unjust violations of the minority's rights? Three motives might be claimed to meliorate the selfishness of the majority: first, "prudent regard for their own good, as involved in the general . . . good" second, "respect for character" and finally, religious scruples. After examining each in its turn Madison concludes that they are but a frail bulwark against a ruthless party.

When one examines these two papers in which Hume and Madison summed up the eighteenth century's most profound thought on political parties, it becomes increasingly clear that the young American used the earlier work in preparing a survey on factions through the ages to introduce his own discussion of faction in America. Hume's work was admirably adapted to this purpose. It was philosophical and scientific in the best tradition of the Enlightenment. The facile domination of faction had been a commonplace in English politics for a hundred years, as Whig and Tory vociferously sought to fasten the label on each other. But the Scot, very little interested as a partisan and very much so as a social scientist, treated the subject therefore in psychological, intellectual, and socioeconomic terms. Throughout all history, he discovered, mankind has been divided into factions based either on personal loyalty to some leader or upon some "sentiment or interest" common to the group as a unit. This latter type he called a "Real" as distinguished from the "personal" faction. Finally, he subdivided the "real factions" into parties based on "interest, upon principle," or upon affection."

Hume spent well over five pages dissecting these three types; but Madison, while determined to be inclusive, had not the space to go into such minute analysis. Besides, he was more intent now on developing the cure than on describing the malady. He therefore consolidated Hume's two-page treatment of "personal" factions and his long discussion of parties based on "principle and affection" into a single sentence. The tenth Federalist reads" "A zeal for different opinions concerning religion, concerning government, and many other points, as well of speculation as of practice; an attachment to different leaders ambitiously contending for pre-eminence and power; or to persons of other descriptions whose fortunes have been interesting to the human passions, have, in turn, divided mankind into parties, inflamed them with mutual animosity, and rendered them much more disposed to vex ad oppress each other than to co-operate for their common good." It is hard to conceive of a more perfect example of the concentration of idea and meaning than Madison achieved in this famous sentence.

The Federalist Papers Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for The Federalist Papers is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

how are conflictstoo often decided in unstable government? Whose rights are denied when this happens?

In a typical non-democratic government with political instability, the conflicts are often decided by the person highest in power, who abuse powers or who want to seize power. Rival parties fight each other to the detriment of the country.

How Madison viewed human nature?

Madison saw depravity in human nature, but he saw virtue as well. His view of human nature may have owed more to John Locke than to John Calvin. In any case, as Saul K. Padover asserted more than a half-century ago, Madison often appeared to steer...

How arguable and provable is the author of cato 4 claim

What specific claim are you referring to?

Study Guide for The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers study guide contains a biography of Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison, literature essays, a complete e-text, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About The Federalist Papers

- The Federalist Papers Summary

- The Federalist Papers Video

- Character List

Essays for The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of The Federalist Papers by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison.

- A Close Reading of James Madison's The Federalist No. 51 and its Relevancy Within the Sphere of Modern Political Thought

- Lock, Hobbes, and the Federalist Papers

- Comparison of Federalist Paper 78 and Brutus XI

- The Paradox of the Republic: A Close Reading of Federalist 10

- Manipulation of Individual Citizen Motivations in the Federalist Papers

Lesson Plan for The Federalist Papers

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to The Federalist Papers

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- The Federalist Papers Bibliography

E-Text of The Federalist Papers

The Federalist Papers e-text contains the full text of The Federalist Papers by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison.

- FEDERALIST. Nos. 1-5

- FEDERALIST. Nos. 6-10

- FEDERALIST. Nos. 11-15

- FEDERALIST. Nos. 16-20

- FEDERALIST. Nos. 21-25

Wikipedia Entries for The Federalist Papers

- Introduction

- Structure and content

- Judicial use

- Complete list

AP® US History

Federalist number 10: ap® us history crash course review.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: March 1, 2022

It’s no question that the Founding Fathers played an important role in American history. When it comes to the people who did so much for the founding of our nation, how can you keep track of everything they did? Luckily for you, we have all the tools you need to master the Fathers’ contributions to the American government. In this APUSH crash course review, we will talk about one of the key documents that could appear on the AP® exam: Federalist Number 10.

What is Federalist Number 10?

Federalist No. 10 is an essay written by James Madison, which appeared in The Federalist Papers . The papers were a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay in 1787 and 1788. They argued for the ratification of the Constitution and were published under the pseudonym Publius (the Roman Publius helped overthrow the monarchy and establish the Roman Republic).

The essay’s main argument was that a strong, united republic would be more effective than the individual states at controlling “factions” – groups of citizens united by some cause “adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the… interests of the community.” In other words, they were groups of people with radical ideas that weren’t good for everyone as a whole.

Factions are controlled either by removing the causes or controlling the effects. Essentially, this means that the government can either solve the problem with which the faction is concerned, or wait for the faction to act and repair the damage. Madison believed that removing the causes was impractical. Why? Well, he says, to get to factions’ ideas at the source, you would either have to take away their liberty or make it so everyone has the same opinions.

Taking away liberty was out of the question for Madison – he wrote, “Liberty is to faction what air is to fire.” Fire needs air to exist, but so do humans. Madison means that taking away liberty would destroy the factions, but it would also destroy others’ happiness. The second option – giving everyone the same opinions – is also impossible. As long as humans have the ability to reason, Madison says, they will form different opinions. Therefore, Madison argued instead that factions must be controlled by responding to them. He wanted to do this by giving them representation in a republican government.

The Constitution called for a republic, which elects representatives for the people. This is in contrast to a “pure democracy,” which would use the popular vote. Madison believed a republic would be able to extend the government to more free citizens of greater parts of the country, who wouldn’t necessarily be able to assemble, which would be required under a pure democracy.

According to Federalist No. 10, a large republic will help control factions because when more representatives are elected, there will be a greater number of opinions. Therefore, it is far less likely that there will be one majority oppressing the rest of the people.

Why is Federalist Number 10 Important?

Federalist No. 10 is possibly the most famous of The Federalist Papers , and is even regarded as one of the highest-quality political writings of all time. Some people even called James Madison the “Father of the Constitution” because of his essays’ influence.

Because Federalist No. 10 and the other Federalist Papers were published under a pseudonym, there was controversy surrounding them. You’re right. In fact, an entire group of Americans called the Anti-Federalists spoke out against these writings. In response to The Federalist Papers , Anti-Federalists even published an impressive collection of political writings called The Anti-Federalist Papers .

Anti-Federalists opposed making the government stronger, in the fear that giving more power to a president might lead to a monarchy. Instead, they wanted state governments to have more authority. This policy was outlined in the Articles of Confederation, the predecessor to the Constitution.

Federalist No. 10 may have had an influence on the eventual ratification of the Constitution, especially in New York. However, it is hard to measure its influence for sure. What is for sure is that debaters used many of the Federalist’s writings as a kind of handbook on how to argue in favor of the Constitution.

What You Need to Know for the APUSH Exam – Multiple-Choice

The multiple-choice section of the APUSH exam could ask you either about specific details, like the contents of Federalist No. 10, or about broader implications, like its impact on ratification debates. You should be familiar with no only Federalist No. 10, but The Federalist Papers as a whole and the other authors, John Jay and Alexander Hamilton.

The multiple-choice section of the APUSH exam now asks you to respond to “stimulus material.” This means there will be sets of questions asking you about a primary or secondary source, such as a quote, painting, map, chart, etc.

Federalist No. 10 might be one of those primary documents. Luckily, you won’t have to identify it – the source will be written below the excerpt. However, you should read over Federalist 10 at some point during your studying, so you’re already familiar with the phrasing. That way, you can focus on the questions sooner, instead of having to digest all the material for the first time.

College Board has not released past multiple-choice questions of this type, but here is a question similar to the ones that could appear on the APUSH exam:

According to Federalist No. 10, Madison thought the most effective way to control factions was

(A) eliminating the source of their grievances

(B) forming a representative republic that would prevent oppression of their opponents

(C) adhering to the strong state powers outlined in the Articles of Confederation

(D) prohibiting faction assemblies

(E) installing a pure democracy in which every man had equal political influence

The correct choice is B. Although Madison proposed the strategy in choice A as a potential option, he ultimately discredited it. Choice D is incorrect because Madison opposed taking away the factions’ liberty, as it was like “air is to fire.” Choices C and E directly contradict Madison’s position as a Federalist – instead, they represent the Anti-Federalist side of the debate.

What You Need to Know for the APUSH Exam – Essays and Document-Based Questions

The Free-Response Questions and DBQs on the APUSH exam will ask you to connect founding documents such as Federalist No. 10 with other events in the broader scope of American history. Madison’s essay or one of the other Federalist Papers could even be one of the sources for a DBQ.

Here is an example of a Free-Response Question where you could tie in Federalist No. 10 into your answer:

Analyze the ways in which the political, economic, and diplomatic crises of the 1780’s shaped the provisions of the United States Constitution.

If you want to write about Federalist No. 10 and the other essays from The Federalist Papers in your response, you could do so in your discussion of the political crises of the 1780’s. Talk about the debate over the Articles of Confederation between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists , and how Federalist No. 10 was used to convince Americans of the need to ratify the Constitution.

Of course, you will also need to bring in details about economic and diplomatic crises at this time, so Federalist No. 10 is only one piece of the puzzle. For more details on how to bring in those other aspects, check out our other APUSH crash courses and the College Board’s detailed scoring guidelines .

Congratulations – you’ve made it through our APUSH crash course on Federalist No. 10! Now you can feel confident tackling questions about one of the most important founding documents. With these tools in hand, you’re well on your way to a 5 in May.

Let’s put everything into practice. Try this AP® US History practice question:

Looking for more APUSH practice?

Check out our other articles on AP® US History .

You can also find thousands of practice questions on Albert.io. Albert.io lets you customize your learning experience to target practice where you need the most help. We’ll give you challenging practice questions to help you achieve mastery of AP® US History.

Start practicing here .

Are you a teacher or administrator interested in boosting AP® US History student outcomes?

Learn more about our school licenses here .

Interested in a school license?

2 thoughts on “federalist number 10: ap® us history crash course review”.

I think it was James Madison who wrote Federalist No. 10, right? There are some points where this article says Hamilton, instead of Madison.

Good catch on the mix up; corrected!

Comments are closed.

Popular Posts

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

Interested in a school license?

Bring Albert to your school and empower all teachers with the world's best question bank for: ➜ SAT® & ACT® ➜ AP® ➜ ELA, Math, Science, & Social Studies aligned to state standards ➜ State assessments Options for teachers, schools, and districts.

PODCAST: HISTORY UNPLUGGED J. Edgar Hoover’s 50-Year Career of Blackmail, Entrapment, and Taking Down Communist Spies

The Encyclopedia: One Book’s Quest to Hold the Sum of All Knowledge PODCAST: HISTORY UNPLUGGED

Federalist Essay No. 10

The only level of government that was to be directly responsive to the people was the House of Representatives. It was granted the most constitutional power but was to be checked by the executive branch, the upper house of the Senate, and the judicial branch. Madison warned against a “pure democracy” in Federalist Essay No. 10. Pure democracies, he surmised, could not protect the people from the evils of faction, which he defined as a group whose interests were alien and counteractive to the good of society. Madison believed that in a pure democracy, factions could easily take control of the government through alliances (or dishonesty) and subject the minority to perpetual legislative abuse. A representative or federal republic, such as the United States , offered as a check against destructive factionalism. Madison thought the states would help control factionalism by rendering a small group from one geographic or political region ineffective against the aggregate remaining states.

During the New York ratification debates , Alexander Hamilton also disputed the observation that “pure Democracy would be the most perfect government.” He said, “Experience has proved that no position in politics is more false than this. The ancient democracies . . . never possessed one feature of good government. Their very character was tyranny; their figure, deformity.” The Constitution created a system far superior, in his estimation, to a pure democracy. John Adams echoed this sentiment and once wrote that “there was never a Democracy yet that did not commit suicide.”

Cite This Article

- How Much Can One Individual Alter History? More and Less...

- Why Did Hitler Hate Jews? We Have Some Answers

- Reasons Against Dropping the Atomic Bomb

- Is Russia Communist Today? Find Out Here!

- Phonetic Alphabet: How Soldiers Communicated

- How Many Americans Died in WW2? Here Is A Breakdown

Federalist Paper No. 10, November 22, 1787

Description

James Madison, along with John Jay and Alexander Hamilton, anonymously wrote a series of essays in New York to convince that state to ratify the federal U.S. Constitution written in Philadelphia in 1787. In Federalist Paper No. 10, Madison writes about how the proposed constitution will help deflect the negative effects of parties.

Transcript of Federalist Paper No. 10

Source-Dependent Questions

- James Madison wrote this essay to convince the people of New York to ratify the proposed federal U.S. Constitution. According to him, why do factions, or parties, form? Do you agree?

- In his farewell address , George Washington warned Americans against forming parties. In what ways does Washington agree or disagree with Madison in his farewell address? Use evidence from the text to support your answer.

- How will the proposed constitution mitigate or lessen the negative effects of factions, according to Madison?

Citation Information

Madison, James, Federalist No. 10: "The Same Subject Continued: The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection," New York Daily Advertiser , 22 November 1787. Courtesy of National Archives

- State Historical Society

- Iowa Humanities Council

- Mission & Strategic Plan

- Boards & Commissions

- Sponsorship Levels

- Gala Logistics & Accessibility

- Weddings & Receptions

- Facility Rental Details

- Employment & Internships

- Renovations

- Iowa's 175 Anniversary

- Iowa National Statuary Hall

- Other Funding Opportunities

- Field Assistance

- History Education

- Lifelong Learning

- Emergency Resources

- Local History Network

- Travel Iowa

Federalist 10: Democratic Republic vs. Pure Democracy

by natalie bolton and gordon lloyd, introduction:.

To assist teachers in teaching the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, Professor Gordon Lloyd has created a website in collaboration with the Ashbrook Center at Ashland University on the Federalist and Antifederalist Debates . Professor Lloyd organizes the content of the debates in various ways on the website. Two lesson plans have been created to align with two of the most noted essays high school students are encouraged to read, Federalist 10 and Federalist 51 . Within each lesson students will use a Federalist Paper as their primary source for acquiring content.

Guiding Question:

Why can a republic protect liberties better than a democracy?

Learning Objectives:

After completing this lesson, students should be able to: Define faction in Federalist 10 . Analyze present day issues and determine if they qualify as a faction as defined in Federalist 10 . Explain why Madison advocated for a democratic republic form of government over a pure democracy in Federalist 10 .

Background Information for the Teacher: