Research Basics

- What Is Research?

- Types of Research

- Secondary Research | Literature Review

- Developing Your Topic

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources

- Evaluating Sources

- Responsible Conduct of Research

- Additional Help

A good working definition of research might be:

Research is the deliberate, purposeful, and systematic gathering of data, information, facts, and/or opinions for the advancement of personal, societal, or overall human knowledge.

Based on this definition, we all do research all the time. Most of this research is casual research. Asking friends what they think of different restaurants, looking up reviews of various products online, learning more about celebrities; these are all research.

Formal research includes the type of research most people think of when they hear the term “research”: scientists in white coats working in a fully equipped laboratory. But formal research is a much broader category that just this. Most people will never do laboratory research after graduating from college, but almost everybody will have to do some sort of formal research at some point in their careers.

So What Do We Mean By “Formal Research?”

Casual research is inward facing: it’s done to satisfy our own curiosity or meet our own needs, whether that’s choosing a reliable car or figuring out what to watch on TV. Formal research is outward facing. While it may satisfy our own curiosity, it’s primarily intended to be shared in order to achieve some purpose. That purpose could be anything: finding a cure for cancer, securing funding for a new business, improving some process at your workplace, proving the latest theory in quantum physics, or even just getting a good grade in your Humanities 200 class.

What sets formal research apart from casual research is the documentation of where you gathered your information from. This is done in the form of “citations” and “bibliographies.” Citing sources is covered in the section "Citing Your Sources."

Formal research also follows certain common patterns depending on what the research is trying to show or prove. These are covered in the section “Types of Research.”

- Next: Types of Research >>

- Last Updated: Dec 21, 2023 3:49 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.iit.edu/research_basics

Read our research on: TikTok | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Part iii: the changing definition of “research”.

Beyond simply shaping research habits and practices, this population of middle and high school teachers suggests that the very definition of what “research” is has changed considerably in the digital world, and that change is reflected in how their students approach the task. The growing use and popularity of search engines among all segments of the population as a critical tool for finding information is reflected in today’s middle and high school students, who have not known a world without these tools. As a result, their very conception of “research” may be fundamentally different from prior generations.

“Research = Googling”

According to the teachers in this study, perhaps the most fundamental impact of the internet and digital tools on how students conduct research is how today’s digital environment is changing the very definition of what “research” is and what it means to “do research.” Ultimately, some teachers say, for students today, “research = Googling.” Specifically asked how their students would define the term “research,” most teachers felt that students would define the process as independently gathering information by “looking it up” or “Googling.” And when asked how middle and high school students today “do research,” the first response in every focus group, teachers and students, was “Google.”

In focus group discussions, teachers framed prior generations’ research practices as a time-consuming process that involved formulating a clear research question and then seeking out relevant and accurate information from trusted sources (mainly libraries), often with the aid of an expert (such as a reference librarian). In contrast, many suggest that today’s students define and approach the process of “doing research” very differently. What was once a slow process that ideally included intellectual curiosity and discovery is becoming a faster-paced, short-term exercise aimed at locating just enough information to complete an assignment. Teachers noted that this trend is driven not only by the immediacy and ease of the online search process, but also the time constraints today’s students face in their lives more generally.

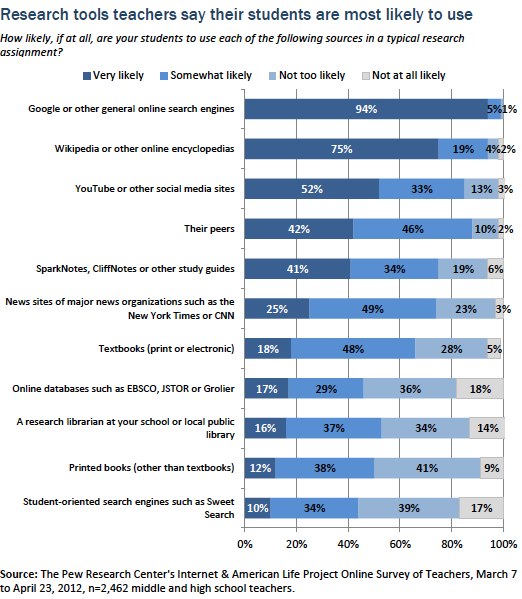

The survey reveals search engines top the list of resources students use

Teachers’ perceptions that their students use only a handful of resources and rely mainly on search engines for their research are echoed in survey results. Asked how likely their students were to use a variety of different information sources for a typical research assignment, 94% of the teachers participating in the survey said their students were “ very likely” to use Google or other online search engines, placing it well ahead of the other sources asked about. Second to search engines was the use of Wikipedia or other online encyclopedias, which 75% of teachers said their students were “very likely” to use in a typical research assignment. And rounding out the top three was YouTube or other social media sites, which about half of teachers (52%) said their students were “very likely” to use.

Virtually all subgroups of this sample of AP and NWP teachers reported similar levels of student use of search engines. The only exception to this pattern was among teachers of the lowest income students (those living below the poverty line); this group was slightly less inclined (at 90%) to say their students are “very likely” to use search engines in a typical research assignment. This group was also among the least likely to report their students are “very likely” to use Wikipedia and other online encyclopedias (68% compared with 75% of the total sample). In contrast, 80% of teachers whose students are described as mostly upper and upper middle income say their students are “very likely” to use sites like Wikipedia.

The use of online encyclopedias as research tools also varied slightly by subject taught, with English teachers at the low end (69%) and science teachers at the high end (82%) of the range of those saying their students are “very likely” to use this source. English teachers are also the least likely to describe their students as “very likely” to use YouTube and other social media sites in a typical research assignment, with 44% reporting this level of use. The figure for the sample of teachers as a whole is slightly higher at 52%.

More “traditional” sources of information, such as textbooks, print books, online databases, and research librarians ranked well below these newly emerging technologies. Fewer than one in five teachers said their students are “very likely” to use any of these sources in typical research assignments. In the case of online databases and printed books, half or more of the teachers who participated in the survey said their students are “not too likely” or “not at all likely” to use these sources. In fact, fewer teachers said their students are likely to use these sources than to use their peers, study guides such as SparkNotes or CliffNotes, or the websites of major news organizations.

When it comes to the use of print books, the findings across all subgroups in this sample of teachers are surprisingly consistent. Teachers of the poorest students—those living below the poverty line—stand out slightly in that they most commonly say their students are “very likely” to use print books in their research assignments (19% say this). Also among the teacher subgroups particularly likely to say their students are “very likely” to use print books in research assignments are middle school teachers (19%) when compared with 9 th -10 th grade teachers (12%) and 11 th -12 th grade teachers (11%). At the other end of the range, science (7%) and math (9%) teachers are particularly un likely to say print books are a common source for their students.

Among the subgroups of this sample who are most inclined to say their students are “very likely” to use research librarians as a source are English teachers (20%) and teachers ages 55 and older (22%). But again, these figures are only slightly higher than the 16% of all teachers who say this is the case.

In focus groups, teachers noted that students prefer the internet because they find it a more interesting and entertaining platform. While the internet is a “cool” place to do research, other more traditional sources are perceived as “boring” by students. The internet offers multi-media content, links to additional information, interactive formats, and textbooks and other print books pale in comparison.

Traditional Textbooks are one-dimensional. They aren’t interactive. They don’t let me go somewhere else if I want more information. There’s no sound, no movies, no hyperlinks. Students are accustomed to interacting with text. I think that’s why textbooks on the iPad have been successful. – National Writing Project teacher

Last week, I gave my students twenty questions posed by the guys at Flocabulary in conjunction with the Wikipedia Blackout in Response to SOPA. The questions ranged from What is the State Bird of Arkansas” to “Who won Super Bowl X?” to “Who won the Republican primary last week?” Since the students could not use Wikipedia, it was interesting to see what they went to next: Ask.com, About.com. Dogpile.com, Google.com, Answers.com, and a host of other sites like these that are a part of my students’ collective toolbox when it comes to securing sources from the web. But when they were answering the one regarding the Super Bowl, none of the students in the six classes I teach ever thought to consult The National Football League. Further, when a question was posed about the first Starbucks, none of my students thought to ask anyone else in the room for their residential expertise. – National Writing Project teacher

Teaching students to do effective searches like SweetSearch.com helps them to understand that a discourse community does exist in regard to their selected subject and these parties often—well always—offer readily citable information wherein their traditional tried and true searches do not. – National Writing Project teacher

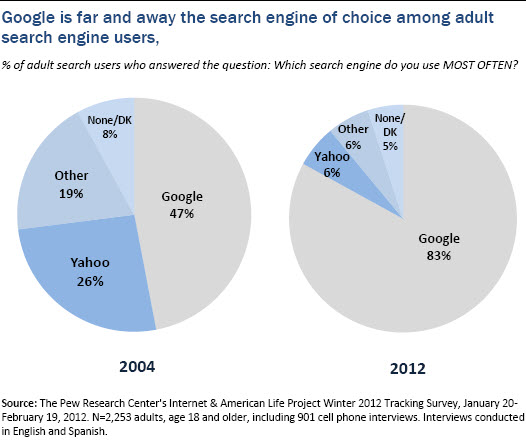

Teens are not alone in their reliance on search engines

The trend among teens to equate finding information with “Googling” mirrors trends seen in adults over the past decade. Over time, Pew Internet’s surveys of adults have consistently shown that search engine use tops the list of most popular online activities, along with email. Currently, 91% of online adults use search engines to find information on the web, up from 84% in June 2004. On any given day online, 59% of those using the internet use search engines. In 2004 that figure stood at just 30% of internet users. 9 Moreover, among adult search users, Google is far and away the most used search engine with Yahoo placing a distant second, and its dominance is growing over time.

Not only are adults increasingly reliant on search engines as an information resource, but they also report generally trusting the results they get and feeling the quality and relevance of the information provided by search engines is improving over time. 10 Specifically:

- 91% of adult search engine users say they always or most of the time find the information they are seeking when they use search engines

- 73% of adult search engine users say that most or all of the information they find using search engines is accurate and trustworthy

- 66% of adult search engine users say search engines are a fair and unbiased source of information

- 55% of adult search engine users say that, in their experience, the quality of search results is getting better over time, while just 4% say it has gotten worse

- 52% of adult search engine users say search engine results have gotten more relevant and useful over time, while just 7% report that results have gotten less relevant

- 56% of adult search engine users say they are very confident in their search abilities, while only 6% say they are not too or not at all confident

- 86% of adult search engine users report that they have learned something new or important using a search engine that really helped them or increased their knowledge

- 50% of adult search engine users say they have found an obscure fact using a search engine that they thought they would not be able to find

In contrast, fewer adult search users report experiencing negative outcomes:

- 41% report getting conflicting information in search results and being unable to determine which information is correct

- 38% say they sometimes feel overwhelmed by the amount of information found using a search engine

- 34% feel that critical information is sometimes missing from search results

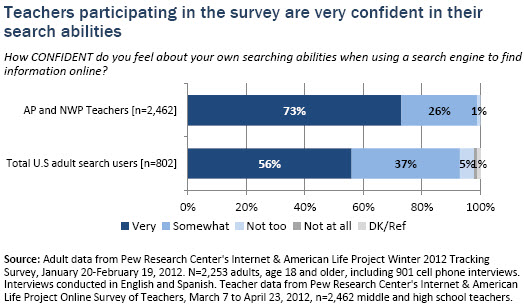

The teachers surveyed are likewise heavy search engine users, and are very confident in their searching abilities

The teachers in our sample are likewise part of the “Googling” trend. Asked about their own use of different online tools, 100% of the teachers participating in the survey said they use online search engines to find information online, with 90% naming Google as the search engine they use most often.

Overall, compared with all U.S. adults, this population of teachers is more confident in their own search abilities. Almost three-quarters (73%) of these middle and high school teachers say they are “very confident” in their own search abilities, with another 26% saying they are “somewhat confident.” Of the more than 2,000 teachers surveyed, only 1% describe themselves as “not too confident” when it comes to using search engines.

While this sample of AP and NWP teachers has greater confidence than adults as a whole in their search abilities, they have considerably less faith in the accuracy of the information they find using these tools. Just 5% of teachers participating in the survey say that “all or almost all” of the information they find using search engines is accurate or trustworthy, compared with 28% of all U.S. adult search users.

The AP and NWP teachers surveyed here are also very different from adults as a whole in that the youngest teachers have less faith in the accuracy of search results. Among the general population, younger adults tend to have more faith in the trustworthiness and accuracy of the search results they get. Yet teachers mirror the general adult population in that younger teachers have more confidence in their search abilities than their older counterparts:

- 50% of teachers ages 22-34 say that all or most of the information they find using search engines is accurate or trustworthy, compared with 61% of teachers ages 35-54 and 68% of teachers age 55 and older.

- Meanwhile, 80% of the youngest teachers say they are “very confident” in their search abilities, compared with 75% of 35-54 year-old teachers and 63% of teachers ages 55 and older.

- See “Search and Email Still Top the List of Most Popular Online Activities,” available at https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/Reports/2011/Search-and-email.aspx . ↩

- “Search Engine Use 2012,” available at https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/Press-Releases/2012/Search-Engine-Use-2012.aspx . ↩

Sign up for our Internet, Science and Tech newsletter

New findings, delivered monthly

Report Materials

Table of contents, most u.s. teens who use cellphones do it to pass time, connect with others, learn new things, how parents feel about – and manage – their teens’ online behavior and screen time, teens who are constantly online are just as likely to socialize with their friends offline, teens’ social media habits and experiences, how teens and parents navigate screen time and device distractions, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Research refers to a systematic investigation carried out to discover new knowledge , expand existing knowledge , solve practical problems , and develop new products, apps, and services. This article explores why different research communities have different ideas about what research is and how to conduct it. Learn about the different epistemological assumptions that undergird informal , qualitative , quantitative , textual , and mixed research methods .

What is Research?

Research may refer to

- For most researchers, the first step in any research project involves strategic searching to learn what the current and best research, theory, and scholarship is on a topic .

- scholars create knowledge by engaging in textual research , interpretation , and hermeneutics .

- Ethnography

- Participant Observation

- Survey Research

- “a systematic application of knowledge toward the production of useful materials, devices, and systems or methods, including design, development, and improvement of prototypes and new processes” (NSF n.d.)

- a process, a research methodology , that follows the principles of lean design .

Key Words: Research Community ; Research Methodology ; Research Methods ; Epistemology

Why Does Research Matter?

Overall, research is essential for advancing knowledge, solving problems, informing decision-making, fostering innovation, and promoting critical thinking. It plays a crucial role in shaping the world we live in and the future we create.

- Research allows us to better understand the world around us, from the fundamental workings of the universe to the intricacies of human behavior. By conducting research, scholars can uncover new information, develop new theories and models, and identify gaps in existing knowledge that need to be filled. This knowledge can help students and teachers to better understand the world around them and develop new solutions to the problems facing society.

- Research helps us identify and solve problems. It can help us find ways to improve our health, protect the environment, reduce poverty, and develop new technologies.

- Research provides important information that can inform policy decisions, business strategies, and individual choices. By studying trends, analyzing data, and conducting experiments, researchers can help us make better-informed decisions.

- Research often leads to new technologies, products, and services. By pushing the boundaries of what is currently possible, researchers can inspire and fuel innovation.

- Research teaches us to question assumptions, evaluate evidence, and think critically. These skills are important for students to develop because they enable them to become more informed and engaged citizens, able to make more informed decisions and contribute to society in meaningful ways.

- Research experience can be an asset in many career fields, including academia, business, government, and nonprofit organizations. By conducting research as an undergraduate student, students can develop valuable skills and experience that can help them to succeed in their future careers.

Types of Research

The choice of research methods depends on the epistemological assumptions of the researchers and the practices of a particular methodological community , the research question , the type of data needed, and the resources available.

Epistemology and Research Communities

Investigators across academic disciplines — the humanities, social sciences, sciences, and the arts — share some common methods and values. For instance, in both workplace writing and academic writing , investigators are careful

- to cite sources , particularly sources that have changed the conversation on a topic

- to provide evidence for claims (as opposed to opinion or other forms of anecdotal knowledge .

Yet it is also important to note that different research communities also develop unique approaches to exploring and solving problems in their knowledge domains. Research communities develop different ways of conducting research because they face different problems and because they may have different epistemological assumptions about what knowledge is and how to measure it. For example, if a researcher believes that knowledge can only be gained through observation and empirical evidence , they may choose to use quantitative research methods such as experiments or surveys . Conversely, if a researcher believes that knowledge can also be gained through subjective experience and interpretation , they may choose to use qualitative research methods such as case study , ethnography or participant observation

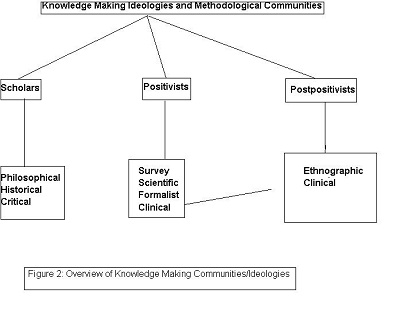

While there are many nuanced definitions of epistemology , scholars have identified three major epistemological perspectives that inform the works of three research communities

- The Scholars – aka Scholarship

- The Positivists – aka Positivism

- The Postpositivists – aka Postpositivism

Research & Mindset

Researchers are curious about the world. They embrace openness , a growth mindset , and collaboration . They undertake research projects in order to review existing knowledge and generate original knowledge claims about the topic , thesis, research question they are investigating. Research finds evidence.

Research Ethics

Researchers and consumers of research are wise to view research claims and research plans from an ethical perspective. Given human nature — such as the tendency to look for confirming evidence and ignore disconfirming evidence and to allow emotions to cloud reasoning — it’s foolhardy to disregard critical literacy practices when consuming the research of others.

Ethics are important to undergraduate students as researchers because ethics provide a framework for conducting research that is responsible, respectful, and accountable :

- Ethics ensure that participants in research are treated with respect and dignity, and that their rights and well-being are protected. As a student researcher, it is important to obtain informed consent from participants, ensure their confidentiality, and minimize any potential harm or discomfort.

- Ethics ensure that research is conducted with integrity and honesty. This means that data is collected and analyzed accurately, and that findings are reported truthfully and transparently.

- Ethics help to build trust between researchers and the public. When research is conducted ethically, participants and the wider community are more likely to trust the findings and the researchers themselves.

- Adhering to ethical standards in research can help students to develop important professional skills, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and communication . These skills can be useful in a wide range of career fields, including academia, healthcare, and government.

- Ethical research is a professional obligation. By conducting research ethically, students are fulfilling their obligations to the wider research community.

Research as an Iterative, Recursive, Chaotic Process

Research is commonly depicted on websites and textbooks on research methods as systematic work (see, e.g., Wikipedia’s Research page).

Depicting research as systematic work is certainly valid, especially in natural and social science research. For instance, scientists in the lab working with a virus like COVID-19 or Ebola aren’t going to play around. Their professionalism and safety is tied to rigorously following research protocols.

That said, it’s an oversimplification to suggest research processes are invariably systematic. Discoveries have emerged from basic research that have been wildly popular and useful real-world applications . (See, for example, 24 Unintended Scientific Discoveries — the video below). Scientists may begin researching hypothesis A but rewrite that hypothesis multiple times until they find hypothesis Z — something that explains the data. Then they go back and repackage their investigation, following ethical standards, for a wider audience.

Ultimately, because research is such an iterative process, the thesis or hypothesis a researcher began with may not be the one the researcher ends up with. The takeaway here is that research is a learning process. Research efforts can lead to unpredictable applications and insights. Research finds evidence. Ultimately, research is about curiosity and openness. The question that initiates a research effort may morph into other questions as researchers

- dig deeper into the literature on the topic and become more conversant

- endeavor to make sense of the data/information they have gathered during the conduct of the study.

Related Concepts

Research methods.

Research results— knowledge claims -—are important. But, how researchers claim to know what they know—their research methods and research methodology —are equally important.

During the early stages of a writing project, you can identify research questions worth asking by engaging in Information Literacy practices.

Using Evidence

Learn to summarize, paraphrase , and cite sources . Weave others’ ideas and words into your texts in ways that support your thesis/research question , information , rhetorical stance .

Hale, J. (2018). Understanding research methodology 5: Applied and basic research, PsychCentral . https://psychcentral.com/blog/understanding-research-methodology-5-applied-and-basic-research/

Related Articles:

Applied Research, Basic Research

Research Methodology

Scholarship

Suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Joseph M. Moxley

Understand the difference between Applied Research and Basic Research.

As an investigator be sure to protect your research subjects and follow ethical standards. As a consumer of research, be mindful of when investigators may be exaggerating results, making claims...

Not all research methods are equal or produce the same kind of knowledge. Learn about the philosophies, the epistemologies, that inform qualitative, quantitative, mixed, and textual research methods.

Understand how to identify appropriate research methods for particular methodological communities, rhetorical situations, and research questions.

Scholarship is not just about memorizing facts or regurgitating information. It’s about developing a deep understanding of a subject, making connections across disciplines, and contributing to the ongoing conversation about...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

What is Research: Definition, Methods, Types & Examples

The search for knowledge is closely linked to the object of study; that is, to the reconstruction of the facts that will provide an explanation to an observed event and that at first sight can be considered as a problem. It is very human to seek answers and satisfy our curiosity. Let’s talk about research.

Content Index

What is Research?

What are the characteristics of research.

- Comparative analysis chart

Qualitative methods

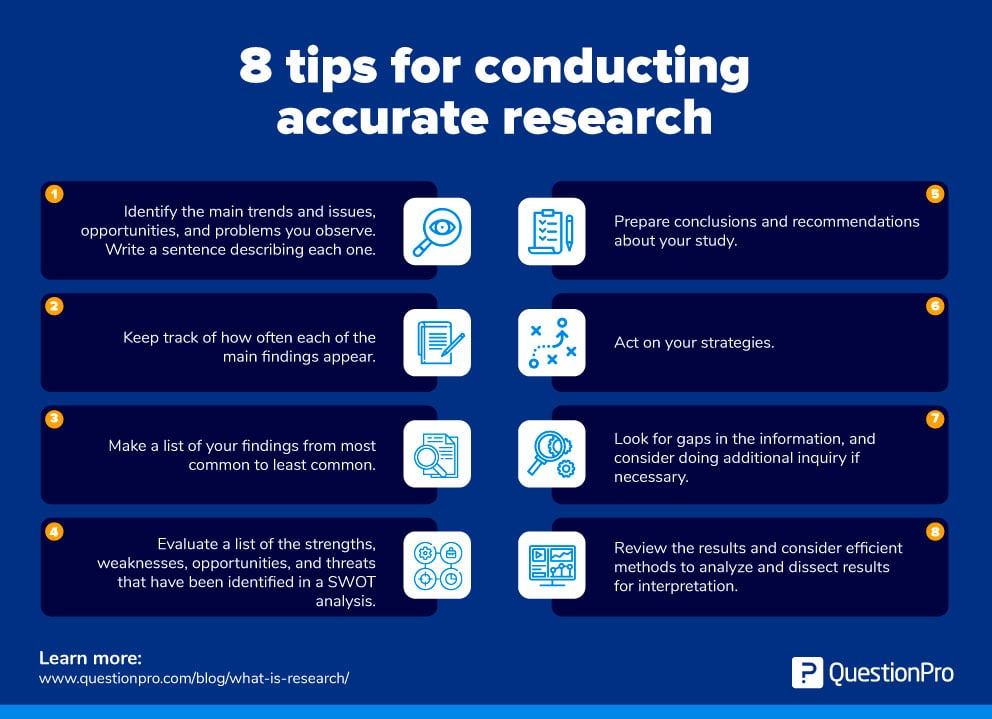

Quantitative methods, 8 tips for conducting accurate research.

Research is the careful consideration of study regarding a particular concern or research problem using scientific methods. According to the American sociologist Earl Robert Babbie, “research is a systematic inquiry to describe, explain, predict, and control the observed phenomenon. It involves inductive and deductive methods.”

Inductive methods analyze an observed event, while deductive methods verify the observed event. Inductive approaches are associated with qualitative research , and deductive methods are more commonly associated with quantitative analysis .

Research is conducted with a purpose to:

- Identify potential and new customers

- Understand existing customers

- Set pragmatic goals

- Develop productive market strategies

- Address business challenges

- Put together a business expansion plan

- Identify new business opportunities

- Good research follows a systematic approach to capture accurate data. Researchers need to practice ethics and a code of conduct while making observations or drawing conclusions.

- The analysis is based on logical reasoning and involves both inductive and deductive methods.

- Real-time data and knowledge is derived from actual observations in natural settings.

- There is an in-depth analysis of all data collected so that there are no anomalies associated with it.

- It creates a path for generating new questions. Existing data helps create more research opportunities.

- It is analytical and uses all the available data so that there is no ambiguity in inference.

- Accuracy is one of the most critical aspects of research. The information must be accurate and correct. For example, laboratories provide a controlled environment to collect data. Accuracy is measured in the instruments used, the calibrations of instruments or tools, and the experiment’s final result.

What is the purpose of research?

There are three main purposes:

- Exploratory: As the name suggests, researchers conduct exploratory studies to explore a group of questions. The answers and analytics may not offer a conclusion to the perceived problem. It is undertaken to handle new problem areas that haven’t been explored before. This exploratory data analysis process lays the foundation for more conclusive data collection and analysis.

LEARN ABOUT: Descriptive Analysis

- Descriptive: It focuses on expanding knowledge on current issues through a process of data collection. Descriptive research describe the behavior of a sample population. Only one variable is required to conduct the study. The three primary purposes of descriptive studies are describing, explaining, and validating the findings. For example, a study conducted to know if top-level management leaders in the 21st century possess the moral right to receive a considerable sum of money from the company profit.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

- Explanatory: Causal research or explanatory research is conducted to understand the impact of specific changes in existing standard procedures. Running experiments is the most popular form. For example, a study that is conducted to understand the effect of rebranding on customer loyalty.

Here is a comparative analysis chart for a better understanding:

It begins by asking the right questions and choosing an appropriate method to investigate the problem. After collecting answers to your questions, you can analyze the findings or observations to draw reasonable conclusions.

When it comes to customers and market studies, the more thorough your questions, the better the analysis. You get essential insights into brand perception and product needs by thoroughly collecting customer data through surveys and questionnaires . You can use this data to make smart decisions about your marketing strategies to position your business effectively.

To make sense of your study and get insights faster, it helps to use a research repository as a single source of truth in your organization and manage your research data in one centralized data repository .

Types of research methods and Examples

Research methods are broadly classified as Qualitative and Quantitative .

Both methods have distinctive properties and data collection methods.

Qualitative research is a method that collects data using conversational methods, usually open-ended questions . The responses collected are essentially non-numerical. This method helps a researcher understand what participants think and why they think in a particular way.

Types of qualitative methods include:

- One-to-one Interview

- Focus Groups

- Ethnographic studies

- Text Analysis

Quantitative methods deal with numbers and measurable forms . It uses a systematic way of investigating events or data. It answers questions to justify relationships with measurable variables to either explain, predict, or control a phenomenon.

Types of quantitative methods include:

- Survey research

- Descriptive research

- Correlational research

LEARN MORE: Descriptive Research vs Correlational Research

Remember, it is only valuable and useful when it is valid, accurate, and reliable. Incorrect results can lead to customer churn and a decrease in sales.

It is essential to ensure that your data is:

- Valid – founded, logical, rigorous, and impartial.

- Accurate – free of errors and including required details.

- Reliable – other people who investigate in the same way can produce similar results.

- Timely – current and collected within an appropriate time frame.

- Complete – includes all the data you need to support your business decisions.

Gather insights

- Identify the main trends and issues, opportunities, and problems you observe. Write a sentence describing each one.

- Keep track of the frequency with which each of the main findings appears.

- Make a list of your findings from the most common to the least common.

- Evaluate a list of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats identified in a SWOT analysis .

- Prepare conclusions and recommendations about your study.

- Act on your strategies

- Look for gaps in the information, and consider doing additional inquiry if necessary

- Plan to review the results and consider efficient methods to analyze and interpret results.

Review your goals before making any conclusions about your study. Remember how the process you have completed and the data you have gathered help answer your questions. Ask yourself if what your analysis revealed facilitates the identification of your conclusions and recommendations.

LEARN MORE ABOUT OUR SOFTWARE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Top 13 Anonymous Employee Feedback Tools for 2024

Mar 25, 2024

Unlocking Creativity With 10 Top Idea Management Software

Mar 23, 2024

20 Best Website Optimization Tools to Improve Your Website

Mar 22, 2024

15 Best Digital Customer Experience Software of 2024

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of research in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- He has dedicated his life to scientific research.

- He emphasized that all the people taking part in the research were volunteers .

- The state of Michigan has endowed three institutes to do research for industry .

- I'd like to see the research that these recommendations are founded on.

- It took months of painstaking research to write the book .

- absorptive capacity

- dream something up

- modularization

- nanotechnology

- non-imitative

- operational research

- think outside the box idiom

- think something up

- uninventive

- study What do you plan on studying at university?

- major US She majored in philosophy at Harvard.

- cram She's cramming for her history exam.

- revise UK I'm revising for tomorrow's test.

- review US We're going to review for the test tomorrow night.

- research Scientists are researching possible new treatments for cancer.

- The amount of time and money being spent on researching this disease is pitiful .

- We are researching the reproduction of elephants .

- She researched a wide variety of jobs before deciding on law .

- He researches heart disease .

- The internet has reduced the amount of time it takes to research these subjects .

- adjudication

- interpretable

- interpretive

- interpretively

- investigate

- reinvestigate

- reinvestigation

- risk assessment

- run over/through something

- run through something

You can also find related words, phrases, and synonyms in the topics:

Related word

Research | american dictionary, research | business english, examples of research, collocations with research.

These are words often used in combination with research .

Click on a collocation to see more examples of it.

Translations of research

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

something dangerous or serious, such as an accident, that happens suddenly or unexpectedly and needs fast action in order to avoid harmful results

Paying attention and listening intently: talking about concentration

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun Verb

- Business Noun Verb

- Collocations

- Translations

- All translations

Add research to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Med Educ

How do students' perceptions of research and approaches to learning change in undergraduate research?

Rintaro imafuku.

1 Medical Education Development Center, Gifu University, Gifu, Japan

Takuya Saiki

Chihiro kawakami, yasuyuki suzuki.

This study aimed to examine how students' perceptions of research and learning change through participation in undergraduate research and to identify the factors that affect the process of their engagement in re-search projects.

This qualitative study has drawn on phenomenography as research methodology to explore third-year medical students' experiences of undergraduate research from participants' perspectives (n=14). Data included semi-structured individual interviews conducted as pre and post reflections. Thematic analysis of pre-course interviews combined with researcher-participant observations in-formed design of end-of-course interview questions.

Phenomenographic data analysis demonstrated qualitative changes in students' perceptions of research. At the beginning of the course, the majority of students ex-pressed a relatively narrow definition of research, focusing on the content and outcomes of scientific research. End-of-course reflections indicated increased attention to research processes including researcher autonomy, collaboration and knowledge construction processes. Furthermore, acknowledgement of the linkage between research and learning processes indicated an epistemological change leading them to take a deep approach to learning in undergraduate research. Themes included: an inquiring mind, synthesis of knowledge, active participation, collaborative and reflective learning. However, they also encountered some difficulties in undertaking group research projects. These were attributed to their prior learning experiences, differences in valuing towards interpersonal communication, understanding of the research process, and social relationships with others.

Conclusions

This study provided insights into the potential for undergraduate research in medical education. Medical students' awareness of the linkage between research and learning may be one of the most important outcomes in the undergraduate research process.

Introduction

Research activity is considered one of the high-impact educational practices in that the vital skills and attitude for lifelong learners can be cultivated through inquiry. 1 - 3 Undergraduate research was defined as any teaching and learning activity in which undergraduate students are actively engaged with the research content, process or problems of their discipline. 4 That is, research is not merely pursuit of academic career and advancement of knowledge (i.e., content). Rather, it also includes an aspect of learning process. 5 - 7 Development of research skills is also important in health professions education. 8 , 9

Research activities by undergraduates are a powerful way of enhancing medical students' basic skills and attitude necessary for future professional practice. Inquiry and an evidence-based medicine (EBM) approach are complimentary processes in that they include recognition of important questions, search for the best research evidence, critical appraisal of the evidence, and application of the evidence to practice. 10 - 12 Modern clinicians, therefore, have to understand both the principles of research and how evidence is derived. 13

Integration of EBM elements into the undergraduate medical curriculum now has increasing significance. For instance, in the first edition of Tomorrow's Doctors issued in 1993, the General Medical Council (GMC) urged innovation in UK undergraduate medical curricula in order to reduce direct instruction of factual content and provide more inquiry-based, student-centred learning environments. 8 One radical change was the introduction of extensive student choice of study modules, which is currently termed 'student selected components' (SSCs). Basically, these curricula provide medical students with opportunities to select study areas of interest and to pursue what they want to know through inquiry. This can potentially be pedagogically effective vehicles for critical appraisal and research skill development. 13 , 14 Likewise, in Japan, 63 out of 80 medical schools have implemented a research-based course in the undergraduate curriculum. 15 Although the duration, study area and assessment method are different among the schools, the common educational purpose is to provide opportunities leading to the development of research skills and basic skills necessary to continuing professional development.

Although research activity as an educational practice has been increasingly employed in a variety of disciplines as well as in diverse cultural contexts, students might take different preferred approaches to learning across cultures. 16 - 19 For instance, Asian students have been portrayed as typically passive, uncritical and rote learners. Asian students' strong perceptions of teachers as knowledge providers are considered one of the influential factors that affect their passive participation in a classroom. 16 On the other hand, there is a paradox between such a description of Asian learners and their academic attainment. 17 - 19 Marton and Dall'Alba indicated the qualitatively different ways of experiencing learning in different cultural contexts. 19 Given the variation in ways individuals experience various phenomena, it is important to understand how Asian learners participate in a student-centred learning environment. As students need to undertake a collective research project in this study, mutual engagement is essential to the process of undergraduate research.

While there is a plethora of discussions on learning outcomes in undergraduate research based on the findings underpinned by a quantitative research paradigm, few studies have examined epistemological changes in research and learning through qualitative analysis of students' research activity. 13 Therefore, this study was undertaken as an initial investigation into this area. A better understanding of students' research experiences from an emic viewpoint allows educators to clearly identify why and how research activity promotes meaningful learning. Furthermore, identifying factors that affect students' research activity can provide important practical implications to effectively encourage and facilitate research opportunities for students. In order to make contribution to this gap in the literature, this study aimed to investigate 1) how students' perceptions of research and learning change through participation in undergraduate research; and 2) what factors affect the process of their engagement in undergraduate research.

Research approach

Qualitative research methods were used for this study, which was particularly underpinned by phenomenography. The rationale of drawing on phenomenography in this study is that the changes in people's ways of interpreting the nature of research generally take place through their own experience of research and interaction with others. 20 Phenomenography allows an examination of "the ways in which people experience, conceptualise, perceive, and understand a phenomenon from their own perspectives." 21 Investigations with a phenomenographic orientation thus focus more on exploration of what is experienced and howit is experienced (i.e., "second-order perspective") than description of the world itself (i.e., "first-order perspective"). 17 , 20 , 21 Within this setting, students' learning processes in undergraduate research are not analysed in terms of what students learned or remembered but rather attends to the relationship between students and the phenomenon. In particular, we briefly describe how phenomenography interprets a relationship between students' approaches to learning.

Phenomenography enables a mapping of the qualitatively different approaches to learning that students adopt. Students' approaches to learning are not regarded as the personality traits or fixed learning styles, but determined through interaction of a student with a specific learning context. 22 Phenomenographers have identified three main types of approaches to learning: deep, surface and strategic approaches. 22 - 24 A deep approach to learning involves relating new ideas to previous knowledge and examining the logic of the argument critically, and leads to understanding and long-term retention of concepts. Thus, learners who take a deep approach to learning primarily focus on seeking meaning. In contrast, a surface approach to learning is associated with information reproducing. For instance, students who take a surface approach to learning try to make use of rote learning, memorize information needed for assessment, take a narrow view and concentrate on detail. A strategic approach to learning is taken to obtain high grades and other rewards. The learning strategies of this approach include identifying the assessment criteria and estimating the learning effort, following up all suggested readings, and using previous exam paper to predict questions. Although deep and surface approaches are mutually exclusive, a strategic approach can be linked to either, that is, surface-strategic or deep-strategic approach. These three pre-identified categories were examined simultaneously with the more inductive labelling process.

Research site

Generally, Japanese medical schools have a 6-year undergraduate curriculum which consists of general education (the first year), pre-clinical studies (the middle 2.5-3 years), and clinical clerkships and preparation for national board examinations (the last 2 years). Sixty out of 80 Japanese medical schools implement a research-based course in the pre-clinical study periods. 15

The context of this study was Gifu University School of Medicine. There was a mandatory course of "Research Experience" in which all third-year students (n=106) selected a 10-week subject or two 5-week subjects from 23 research themes of basic, social or clinical medical sciences, such as anatomy, legal medicine and paediatrics, and then pursued a research topic of interest. It predominantly involved project work, and there were no other classes during the 'research' weeks to detract from their learning experiences through inquiry. As a summative assessment, they were required to give poster and oral group presentations in front of all third-year students and faculty in the final week.

Medical education research was a 5-week course in 2013, and was altered to a 10-week course in 2014. Class meetings (2-3 hours) were basically scheduled three days a week, and the rest of class time in a week (21 hours) was allotted to self-directed research activity. In every class, students were encouraged to discuss research design and to give a progress report. Academic staff in medical education centre participated as mentors who encourage students to undertake a research project as autonomously as possible.

Participants

A purposive sampling was adopted, and 14 third-year medical students (9 male, 5 female: S1-S14) who selected medical education research in 2013 or 2014 agreed to participate in this study. They conducted medical education research projects about medical students' perceptions of career choices, learning experiences in PBL tutorials, or gender differences in perceptions of career and family among students. S1 has had some research experience as a student research assistant and S8 holds a Master's degree in psychology. However, the rest of participants has little experience in conducting research.

In order to achieve the consistency of research context, we carried out data collection only in the medical education centre, because the course structure varied according to the research field, such as the role of tutor and duration/frequency of class meeting. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Gifu University.

Data collection

This qualitative study drew upon methods of direct observation and semi-structured interviews. Observations allow for insight into contexts, relationships and behaviour by better understanding what participants do. The first author as a participant observer in the two academic years of the study made records to capture the details of students' participation in the course. To deal with observer effect, we did not reveal the specific focus of the observation, but obtained students' consent to observe their learning activities. These observational data were rigorously analysed to gain emic understandings of the context of student research activity and to inform the development of the second (post) interview guide as to more closely situate it to each individual's context.

Each participant was invited to be interviewed twice during the course. The first interview (pre) was conducted in the second week of the course, and the second interview (post) was in the final (fifth or tenth) week of the course. Each interview lasted around 25 to 45 minutes, and was audio-recorded. Japanese transcripts were translated into English by the first author.

In the first interviews, we attempted to elicit information on students' prior experiences, perceptions of research, understanding of student roles and on-going experiences in this programme. Prior research findings in phenomenography have informed the first interview schedule. 22 , 25 In the second, follow-up interviews, we focused on eliciting information on challenges which they found in the process of undertaking a group research project; their approaches to researching; perceived benefits of undergraduate research; and; changes in their perceptions of research and learning. Moreover, we also asked some questions which were informed by the observational data (e.g., I felt you participated more actively than before. Why did your participation pattern change over time? ).

Data analysis procedures

Interview data were qualitatively analysed based on the principles of phenomenography as an empirical approach to describing the qualitatively different means of people's experience. 19 , 21 There are seven common steps of data analysis in phenomenography. 26 The first step is familiarization in which the researchers need to read through transcripts to become familiar with empirical data and obtain a sense of the whole. The second step involves compilation ofanswers from all respondents to a certain question. The most significant elements in the answer need to be identified here. The third step is a condensation of the individual answers to find the central part of longer answers. The fourth step contains a preliminary grouping ,and the researchers allocate answers expressing similar ways of understanding the phenomenon to the same category. The fifth step is a preliminary comparison of categories with regard to similarities and differences. The sixth step consists of labelling to express the core meaning of the category. The seventh step is a contrastive comparison of categories. Comparing the categories through a contrastive procedure, the unique character of the categories and its relationship between them are described.

Following these steps above, the data were carefully reviewed multiple times by the research team, and we inductively generated salient categories. In this process, peer debriefing was used as a technique to establish credibility and validity of the data analysis. That is, the authors worked together on the coding of data to prevent some critical problems of analysis, such as misinterpretation of data and vague descriptions of coding. Member checking was also undertaken to confirm whether researchers' interpretation of interview data was congruent with what participants intended to express.

Changes in perceptions of research

We examined Japanese medical students' reflection on and perceptions of their experiences in undergraduate research. In particular, the focus of the data analysis was on understanding how students' perceptions of research changed through their experiences of conducting research a project and how the change in epistemological belief regarding research relates to students' approaches to learning. The labelling procedures (see below) produced two core categories, 'content-oriented' and 'process-oriented' approaches to study. Contrastive comparison indicated that, of the total number of 14 students, 10 students' perceptions of research (S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S7, S8, S10, S11, and S14) qualitatively changed from 'content-oriented' to 'process-oriented' ones during the undergraduate research course. The remaining four students' perceptions of research (S6, S9, S12, and S13) remained 'content-oriented'. In what follows, we detail the establishment of these categories and the result of contrastive comparison.

Students' perceptions of research in Week 2

As to students' perception of research at the early stage of the programme, three main themes emerged from the first (pre) interview data: irrelevant activity to undergraduates' life, research methods and outcomes ( Table 1 ). In the first interview, the majority of students expressed a relatively narrow definition of research, focusing on the content and outcomes of scientific research.

In response to what students mean by research in the first interview, some students were not clear about what research is due to their less experience of conducting research. They said that research was irrelevant activity to undergraduates' life in that research tended to be regarded as an activity only by people who pursue academic career, such as postgraduate-level and faculty-level:

"I don't feel familiar with research activity because I haven't conducted it. Since I think research is an activity for becoming academics, I'm not really interested in conducting research, and it is irrelevant to medical students, who want to actively take part in clinical practice, not research position, in the future, like me." (S2, Group 1, Week 2, 2013)

In addition, medical students in this study conceived research as experiment, hypothesis testing or lonely activity of scientists. The term "research" tended to give the medical students a certain impression in association with science experiment.

"In my understanding, research is to make a microscopic study in a scientific laboratory all the day. There is no chance to communicate with others. So, I have a negative impression that research is a lonely activity." (S6, Group 2, Week 2, 2013)

"I think that research means verifying hypotheses through repeated same experiments. So, it is conducted so as to reveal the truth logically based on objective data. I feel it boring and time consuming." (S13, Group 3, Week 2, 2014)

Lastly, their perception of research was related to its outcome and output. Students emphasized "an epoch-making discovery" and "advancement of knowledge" as keywords regarding research. They tended to regard research as scientists' activity which presents new perspective of a certain study field and solution to complex problems. That is, at the early stage of the research project course, the majority of participants in this study thought that undergraduates' life was unrelated to research involvement:

"Research is conducted in order to advance knowledge in your academic field, such as medical sciences. I think publication of journal article and conference presentation can be central to research activity." (S10, Group 3, Week 2, 2014)

"For me, research means discovery of what nobody knows or invention of new devices. I haven't conducted research before, so it's just my impression, but I research works would be achieved by the limited great figures, experts, in academic fields." (S12, Group 3, Week 2, 2014)

Students' perceptions of research in final week (tenth or fifth week)

Data analysis of the second (post) interview showed their increased attention to research processes, including autonomy, collaborative working and knowledge construction processes. Furthermore, through participation in research project, they realised that research has something to do with learning process in their own context of studying at the medical school. That is, their perceptions of research were related to experiment, solitude and exhaustive work in Week 2, whereas they could view research as social and cognitive processes of daily activity in the final week. Table 2 provides a summary of their perceptions of research in the final week.

As shown in Table 2 , students recognised the linkage of research and learning through participation in research project. In Week 2, they perceived research and learning as separate activities. Specifically, research was viewed as an irrelevant activity to undergraduates' life and also as an activity which was undertaken only by someone who pursues an academic career. However, they began to relate the process of research to their learning experiences during the course. S2 said:

"Recently, I gradually became aware that the processes of learning might be similar to those of research. Like, it includes investigation of what I want to know, information gathering necessary to the goals, and a study meeting with my friends outside classroom. I think what I did in our research project was exactly congruent to the process of learning." (S2, Group 1, Final week, 2013)

In addition to students' awareness of linkage between learning and research processes, research could be viewed as process of inquiry by them in the final week. Students said that researcher autonomy or inquiring mind is a core concept of research. S11 emphasised the importance of inquiring mind in doing research:

"Research is a process of approaching to the truth, which is driven by your inquiring mind. For example, we researched students' perceptions of career choice as medical doctor and family, umm, sharing housework with partner. People's perceptions vary according to their background, and we couldn't draw one definite conclusion from data. However, I really enjoyed working in this process, and my inquiring mind made me participate more actively in the research project." (S11, Group 3, Final week, 2014)

S2 said that researcher’s autonomy during the research process is important for inquiry. Moreover, he noticed that research could be seen as not a special activity of scientist but a daily activity of people.

"Investigating on your own initiative is pivotal to conducting a research project. So, research is to investigate what I want to know on my initiative. In the first interview, I said I had no idea about research, but now I feel research can include not only scientists' work but also our daily activity of learning." (S2, Group 1, Final week, 2013)

As students in this study were engaged in research work as a group, some participants viewed research from a social, interpersonal perspective. In the first interview, research was seen as scientist's lonely activity, whereas students mentioned in the second interview that research was collaborative work. S3 said:

"All group members needed collaboratively work to find out our own way to attain the shared goal of the research project. It is important for each member to actively make contribution to the research project. I needed to understand how I could contribute to group work, like my own role in this group. Before I participated in this course, I thought research should be done alone, but now I realize that research also includes group work, and collaborative work with members is really essential to the research project." (S3, Group1; Final week 2013)

From a cognitive perspective, research was viewed as a knowledge construction process by them in the final week. S14 said:

"I could realise that research includes the processes of integrating a variety of data into the meaning, and presenting the findings to people. It was very difficult to answer our research questions based on such an extensive data obtained from interview and questionnaire survey and we struggled to interpret those data, but I noticed that this process of thinking was research." (S14, Group 3, Final week, 2014)

Therefore, analysis of interview data shows that students' perceptions of research have changed qualitatively through experience in conducting research.

Relationship between perceptions of research and approaches to learning

Deep approach to learning.

Students who could have a process-oriented perception of research took a qualitatively deeper approach to learning during the course. Five themes regarding deep approach to learning emerged from the analysis of interview data: inquiring mind, synthesis of knowledge, active participation, collaborative learning and reflective learning.

Firstly, their inquiring mind intrinsically motivated their engagement with the research. As S4 mentioned, he did not feel that he was forced to do the research project by someone in a mandatory course. Such motivation has led to their deep approaches to learning.

"I have a research stance that seeks what I want to know for its own sake. Now, I'm not reluctantly doing research under someone's instruction. Rather, with tutor's advices, I'm carrying out the research on my own initiative, umm, pursue what I want to know for my own sake." (S4, Group1; Final week 2013)

"I want to do further investigation by interviewing with the students which can be useful for a deeper analysis of PBL. I felt only questionnaire was not enough to better understand their attitudes toward PBL." (S7, Group 2; Final week 2013)

Secondly, students expressed synthesis of knowledge which is a more complex cognitive process in Bloom's taxonomy. 27 For instance, S11 fully enjoyed drawing a conclusion from a large amount of data. S11's comments implied that interpretation of the phenomenon involved comparison, integration and categorisation of data:

"I felt really interesting in interpreting the common or different ideas on family and career planning among male and female medical students from extensive data obtained through interviews and questionnaire survey. Apparently, I supposed that those data were not interrelated, but, in fact, I realized that there was a story on what human being is behind the data." (S11, Group 3, Final week, 2014)

Thirdly, in transition from direct instructional context to student-centred learning context, necessity of active learning was strongly acknowledged by them. In doing research project, students needed to collect and analyse data on their own initiative in order to investigate what they want to know. S4 said:

"I've got used to obtaining knowledge by listening to teachers since I was a child. It was a kind of first time to work out a plan for the research project by ourselves. I realised the importance of actively study something in my career as a medical doctor through research design, data collection and analysis in the course." (S4, Group1, Final week, 2013)

Fourthly, in the context of collaborative work, the importance of teamwork was also emphasised. Although S3 felt it difficult to make contribution to the group work, she realised that sharing her opinions can be essential to elaboration of research planning and data analysis in group.

"Through research, I realised the importance of expressing my opinion explicitly. At the beginning, I hesitated to do it, because I worried if my opinion would be off the point in the group discussion, but now I can say any opinions can contribute to the research work, which can be also related to teamwork." (S3, Group 1, Final week, 2013)

Lastly, each student continuously reflected on the progress of their research work, their underlying belief on research and areas of improvement in order to attain the shared goals. For instance, S5 attempted to better understand the nature of qualitative research during this course, and he noticed that this reflective process actually led to his meaningful learning.

"During the research project, I was always thinking of what qualitative research is and how I could qualitatively analyse data obtained. This kind of reflection on what I did and repeatedly thinking of qualitative research connected to meaningful learning. Although I couldn't find out the exact answer during this course, this was a good experience for me." (S7, Group 2, Final week, 2013)

S1 tried to improve the consistency of their work through reflection on the research purposes which were discussed at the early stage. S1 acknowledged the importance of reflection in doing research:

"It was very important to take the consistency of the research into account. Don't forget what we originally wanted to know and clarify. When I was stuck with research planning and data analysis, I always reflected on what we discussed with respect to research questions in Week 1." (S1, Group 1; Final week, 2013)

Strategic approach to learning

Students who had only a content-oriented perception of research tended to take a strategic approach to learning, which aims to earn the (highest possible) grades of the course, such as well organised study methods and effective time management. 23 However, there was a slight change from surface-strategic to deep-strategic approaches. For instance, at the early stage of research project, S6 attempted to manage what he needed to do in his group by minimal effort and only followed tutors' suggestions. S6 stated:

"I felt my ideas were not insightful, and I couldn't effectively make contribution to the group work. That's why I focused on just listening to others and following others' suggestions, which was the most efficient way of completing the task." (S6, Group 2; Week 2, 2013)

His main focus was on finding an efficient way of completing the task in this course. He did not build knowledge through active interaction with members but keep quiet to avoid interrupting others’ discussions. However, as he experienced a group situation where others were stuck and there was frequent silence during research planning, his approach to research project appeared to change to a deep-strategic approach. S6 stated:

"I started to think that I had to share my opinions in our group, otherwise we couldn't finish this project on time.

When they were completely stuck in the meeting, I strongly felt that I needed to do something. Once I made contribution in the discussion, I started to enjoy participating in this project." (S6, Group 2; Final week, 2013)

Although his main aim was to complete the task and to obtain safe grade in this research course, he could take a leadership in the group and share his opinions more actively.

Factors affecting students' engagement with undergraduate research

This study identified four main inclusive factors which led to the Japanese medical students in this study expressing practical difficulties in the course:

- Prior learning experience

- Values towards interpersonal communication

- Understanding of research process

- Social relationships with tutors and peers

The first factor is their prior learning experiences. Students identified a gap in the instructional approaches between their prior learning experiences and undergraduate research. In Week 2, most students regarded learning as an activity where students are taught by a teacher's highly structured direction and provision of knowledge. On the other hand, undergraduate research is a more open-ended, inductive and student-centred activity. They appeared to struggle to work out the research project due to this pedagogical gap. S2 said:

"There isn't a clear answer in advance, and no one will give an answer in doing research project. We have to build up hypothesis, and to verify it, we need to collect relevant data, and then analyse them in depth. So, research is totally different from learning. It puzzled me what to do in this research project." (S2, Group 1; Week 2, 2013)

The second factor is their values of interpersonal communication. Although students acknowledged that active participation was essential to their research project work, they tended to hesitate in active self-expression in the group. The major source of their reticence was not their fear of making mistakes itself, but an anxiety of whether they would disturb the collective work. For instance, since S6 highly valued intelligible explanation, he could rarely give uncertain information in the group. S6 said:

"I'm a poor talker by nature, and I don't want to bother others by sharing my uncertain idea. When I was not fully confident, I tended to hesitate to make contribution to the discussions." (S6, Group 2; Week 2, 2013)

The third factor is an understanding of research process. Practical difficulties during the research process include information searching, literature review, data collection and analysis. It was hard for them to obtain a clear image of what research is and what to do next during the course. S7 commented:

This was the first time to conduct qualitative research, so we couldn't even imagine what it is, and I didn't know what to do next in the research process. If we had to carry out research project by ourselves, I had no idea, like what I should do. (S7, Group 2, Final week, 2013)

The fourth factor is social relationships with tutors and peers. They sometimes felt that their participation was restricted by tutors' presence and instruction. S11 said:

"I think tutors had a strong presence. I know a tutor's opinion can be better than ours. I wasn't confident enough to express a thoughtful opinion in group discussions. So, sometimes I waited for tutor's suggestions rather than sharing my idea." (S11, Group 3, Week 2, 2014)

Furthermore, some students found it difficult to identify their own role in the group. For instance, S1 who was a more experienced member struggled to find a way to effectively contribute to the group work. S1 said:

"I have to find a suitable position in the group. It was difficult to identify my own role in this group. I felt other members were getting more independent, not relying on me. So, I need to think about how I can contribute to this group." (S1, Group 1, Week 2, 2013)

This interview excerpt shows that identity formation as a member is a key element of students' research activity, particularly in a collaborative learning context.

This study has drawn on phenomenography as research methodology to explore students' experiences in undergraduate research from the lens of study participants. Specifically, the focus of this study was on examining how research experiences informed students' perceptions of research and approaches to learning. Whilst all students were originally identified as aligning to a 'content-oriented' approach to studying, by the final week of the research project, ten out of 14 students in this study changed perceptions of research to a process-oriented view. By tracing changes in perception over time, data analysis revealed that, through participation in research project, their approaches to learning became qualitatively deeper, (-an inquiring mind, synthesis of knowledge, active participation, collaborative learning and reflective learning). Although four students' perceptions of research remained content-oriented, their strategic approaches to learning were also qualitatively changed. Although students took different approaches to learning in the undergraduate research, this study fully described the processes of changes in their perceptions of research and approaches to learning.

This study found that students' perceptions of research were (re-)formed through their actual research experiences, and these epistemological changes led to the adoption of deep approaches to learning in this course. The findings concurred with the previous studies which specified the key learning outcomes related to research skills. 28 , 29 Specifically, two types of learning outcomes would be expected in research-based education. 28

The first type is professional skills learning outcome which includes management of resources and time, self-directed learning, and communication skills. Students in this study could regard research as an activity with inquiring mind and mutual engagement within the context of "Research Experience" course. Thus, a given context, perception, and approaches to learning are reciprocally related. 23