Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

Published on June 12, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Quantitative research is the process of collecting and analyzing numerical data. It can be used to find patterns and averages, make predictions, test causal relationships, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative research is the opposite of qualitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio).

Quantitative research is widely used in the natural and social sciences: biology, chemistry, psychology, economics, sociology, marketing, etc.

- What is the demographic makeup of Singapore in 2020?

- How has the average temperature changed globally over the last century?

- Does environmental pollution affect the prevalence of honey bees?

- Does working from home increase productivity for people with long commutes?

Table of contents

Quantitative research methods, quantitative data analysis, advantages of quantitative research, disadvantages of quantitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about quantitative research.

You can use quantitative research methods for descriptive, correlational or experimental research.

- In descriptive research , you simply seek an overall summary of your study variables.

- In correlational research , you investigate relationships between your study variables.

- In experimental research , you systematically examine whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship between variables.

Correlational and experimental research can both be used to formally test hypotheses , or predictions, using statistics. The results may be generalized to broader populations based on the sampling method used.

To collect quantitative data, you will often need to use operational definitions that translate abstract concepts (e.g., mood) into observable and quantifiable measures (e.g., self-ratings of feelings and energy levels).

Note that quantitative research is at risk for certain research biases , including information bias , omitted variable bias , sampling bias , or selection bias . Be sure that you’re aware of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data to prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once data is collected, you may need to process it before it can be analyzed. For example, survey and test data may need to be transformed from words to numbers. Then, you can use statistical analysis to answer your research questions .

Descriptive statistics will give you a summary of your data and include measures of averages and variability. You can also use graphs, scatter plots and frequency tables to visualize your data and check for any trends or outliers.

Using inferential statistics , you can make predictions or generalizations based on your data. You can test your hypothesis or use your sample data to estimate the population parameter .

First, you use descriptive statistics to get a summary of the data. You find the mean (average) and the mode (most frequent rating) of procrastination of the two groups, and plot the data to see if there are any outliers.

You can also assess the reliability and validity of your data collection methods to indicate how consistently and accurately your methods actually measured what you wanted them to.

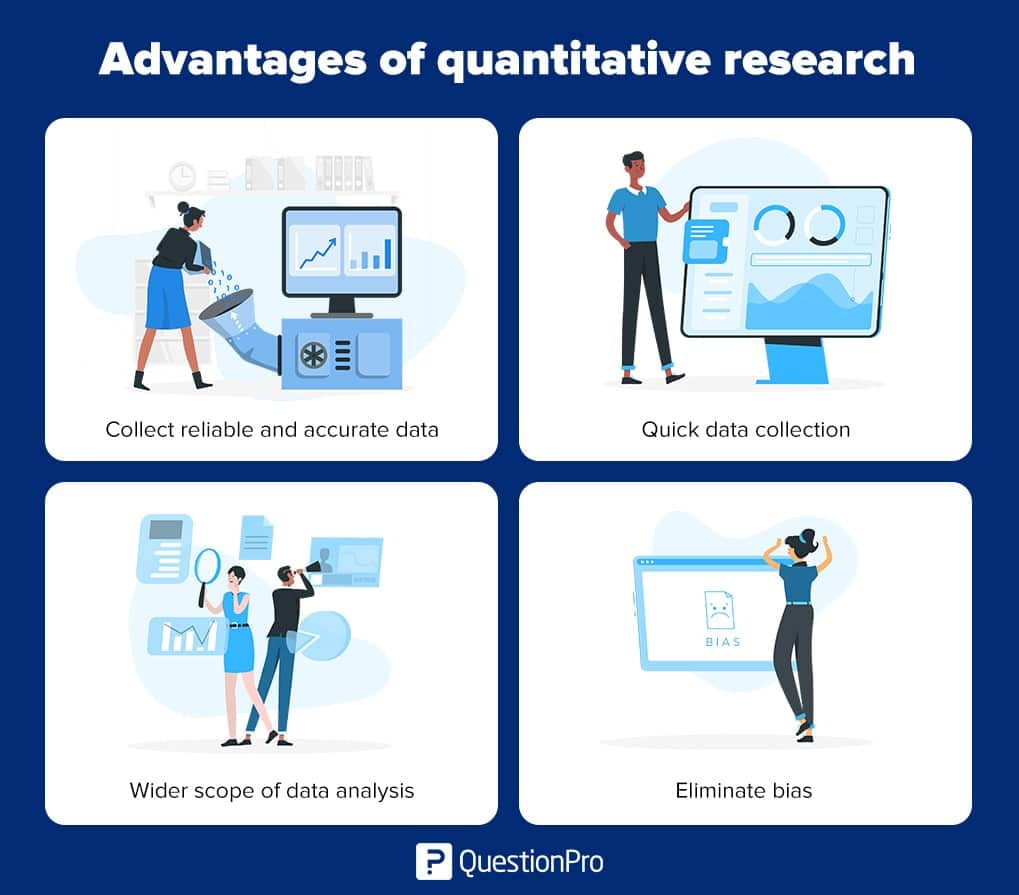

Quantitative research is often used to standardize data collection and generalize findings . Strengths of this approach include:

- Replication

Repeating the study is possible because of standardized data collection protocols and tangible definitions of abstract concepts.

- Direct comparisons of results

The study can be reproduced in other cultural settings, times or with different groups of participants. Results can be compared statistically.

- Large samples

Data from large samples can be processed and analyzed using reliable and consistent procedures through quantitative data analysis.

- Hypothesis testing

Using formalized and established hypothesis testing procedures means that you have to carefully consider and report your research variables, predictions, data collection and testing methods before coming to a conclusion.

Despite the benefits of quantitative research, it is sometimes inadequate in explaining complex research topics. Its limitations include:

- Superficiality

Using precise and restrictive operational definitions may inadequately represent complex concepts. For example, the concept of mood may be represented with just a number in quantitative research, but explained with elaboration in qualitative research.

- Narrow focus

Predetermined variables and measurement procedures can mean that you ignore other relevant observations.

- Structural bias

Despite standardized procedures, structural biases can still affect quantitative research. Missing data , imprecise measurements or inappropriate sampling methods are biases that can lead to the wrong conclusions.

- Lack of context

Quantitative research often uses unnatural settings like laboratories or fails to consider historical and cultural contexts that may affect data collection and results.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

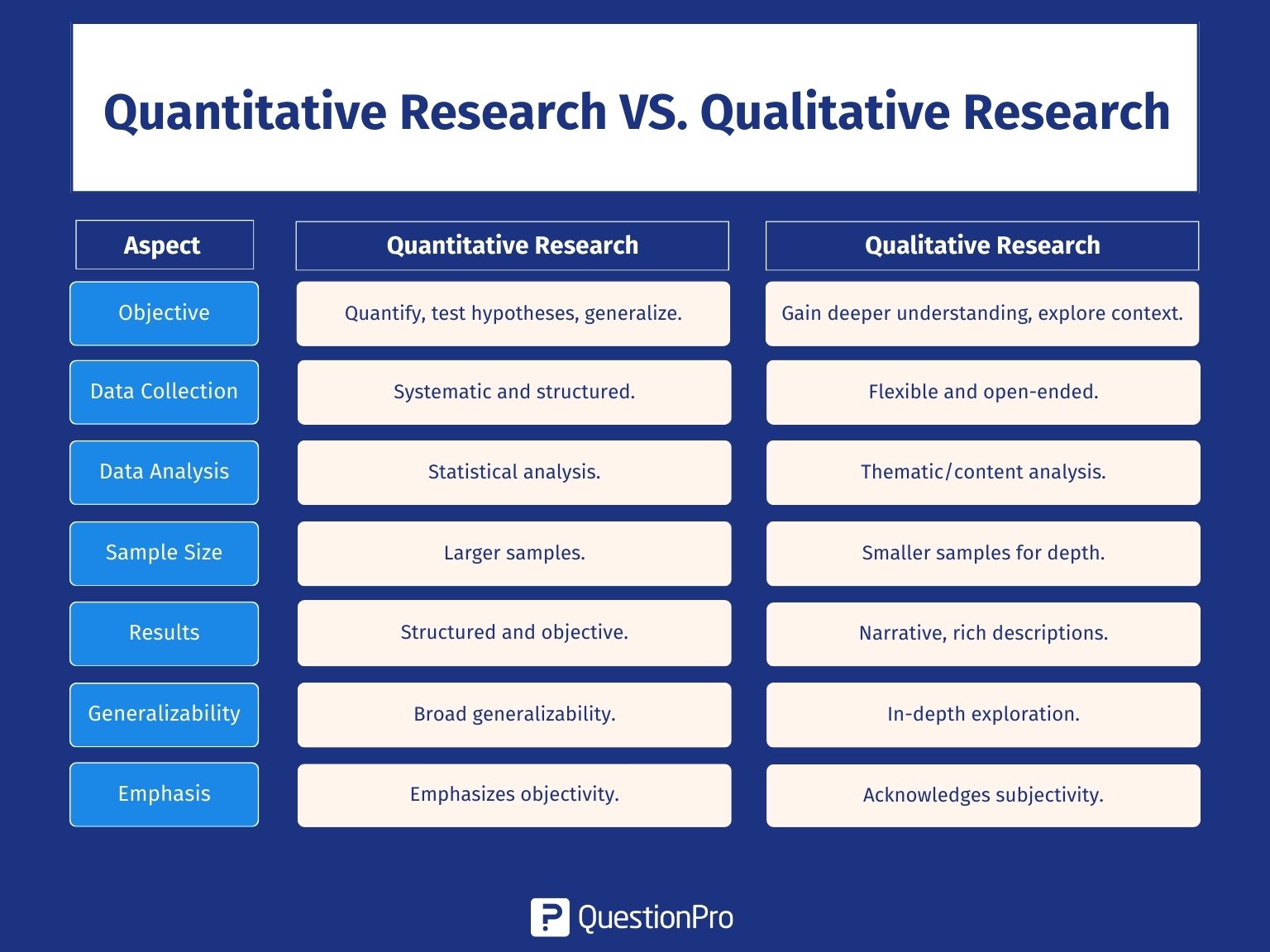

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

Operationalization means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioral avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalize the variables that you want to measure.

Reliability and validity are both about how well a method measures something:

- Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure (whether the results can be reproduced under the same conditions).

- Validity refers to the accuracy of a measure (whether the results really do represent what they are supposed to measure).

If you are doing experimental research, you also have to consider the internal and external validity of your experiment.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved March 11, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/quantitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, descriptive statistics | definitions, types, examples, inferential statistics | an easy introduction & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

What is Quantitative Research Design? Definition, Types, Methods and Best Practices

By Nick Jain

Published on: July 7, 2023

Table of Contents

What is Quantitative Research Design?

Types of quantitative research design, quantitative research design methods, quantitative research design process: 10 key steps, top 11 best practices for quantitative research design.

Quantitative research design is defined as a research method used in various disciplines, including social sciences, psychology, economics, and market research. It aims to collect and analyze numerical data to answer research questions and test hypotheses.

Quantitative research design offers several advantages, including the ability to generalize findings to larger populations, the potential for statistical analysis and hypothesis testing, and the capacity to uncover patterns and relationships among variables. However, it also has limitations, such as the potential for oversimplification of complex phenomena and the reliance on predetermined categories and measurements.

Quantitative research design key elements

Quantitative research design typically follows a systematic and structured approach. It involves the following key elements:

- Research Question: The researcher formulates a clear and specific question that can be answered through quantitative research . The question should be measurable and objective

- Variables: The researcher identifies and defines the variables relevant to the research question. Variables are attributes or characteristics that can be measured or observed. They can be independent variables (factors that are manipulated or controlled) or dependent variables (outcomes or responses that are measured).

- Hypotheses: The researcher develops one or more hypotheses based on the research question. Hypotheses are verifiable statements that make predictions about the association between variables.

- Sampling: The researcher determines the target population and selects a representative sample from that population. The sample should be large enough to provide statistically significant results and should be chosen using appropriate sampling techniques.

- Data Collection: Quantitative research design relies on the collection of numerical data. This can be done through various methods such as surveys, experiments, quantitative observations , or secondary data analysis. Standardized instruments, such as questionnaires or scales, are often used to ensure consistency and reliability.

- Data Analysis: The collected data is analyzed using statistical methods and techniques. Descriptive statistics are used to summarize and describe the data, while inferential statistics are used to draw conclusions and make generalizations about the population based on the sample data.

- Results and Conclusions: The researcher interprets the findings and draws conclusions based on the analysis. The results are typically presented in the form of tables, graphs, and statistical measures, such as means, correlations, or regression coefficients.

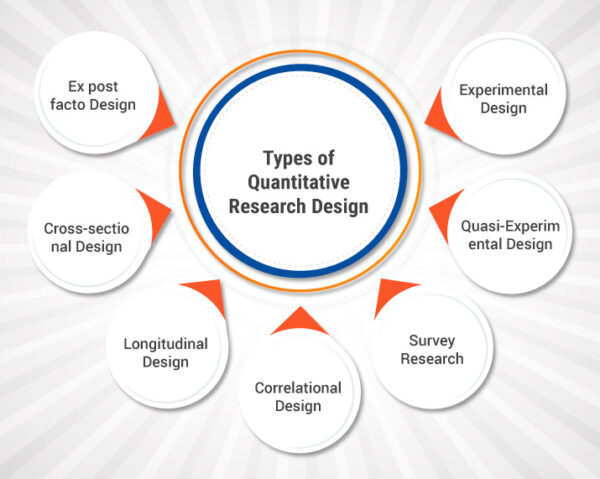

There are several types of quantitative research designs, each suited for different research purposes and questions. Here are some common types of quantitative research designs:

- Experimental Design

Experimental design involves the manipulation of an independent variable to observe its effect on a dependent variable while controlling for other variables. Participants are typically randomly assigned to different groups, such as a control group and one or more experimental groups, to compare the outcomes. This approach enables the establishment of cause-and-effect relationships.

- Quasi-Experimental Design

Quasi-experimental design exhibits similarities to experimental design, yet it lacks the random assignment of participants to groups. The researcher takes advantage of naturally occurring groups or pre-existing conditions to compare the effects of an independent variable on a dependent variable. While it doesn’t establish causality as strongly as experimental design, it can still provide valuable insights.

- Survey Research

Survey research involves collecting data through questionnaires or interviews administered to a sample of participants. Surveys allow researchers to gather data on a wide range of variables and can be conducted in various settings, such as online surveys or face-to-face interviews. This design is particularly useful for studying attitudes, opinions, and behaviors within a population.

- Correlational Design

The correlational design investigates the association between two or more variables without engaging in their manipulation. Researchers measure variables and determine the degree and direction of their association using statistical techniques such as correlation analysis. However, correlational research cannot establish causality, only the strength and direction of the relationship.

- Longitudinal Design

Longitudinal design involves collecting data from the same individuals or groups over an extended period. This design allows researchers to study changes and patterns over time, providing insights into the stability and development of variables. Longitudinal studies can be conducted retrospectively (looking back) or prospectively (following participants into the future).

- Cross-sectional Design

Cross-sectional design collects data from a specific population at a single point in time. Researchers examine different variables simultaneously and analyze the relationships among them. This design is often used to gather data quickly and assess the prevalence of certain characteristics or behaviors within a population.

- Ex post facto Design

Ex post facto design involves studying the effects of an independent variable that is beyond the researcher’s control. The researcher selects participants based on their exposure to the independent variable, collecting data retrospectively. This design is useful when random assignment or manipulation of variables is not feasible or ethical.

Learn more: What is Quantitative Market Research?

Quantitative research design methods refer to the specific techniques and approaches used to collect and analyze numerical data in quantitative research . Below are several commonly utilized quantitative research methods:

- Surveys: Surveys involve administering questionnaires or structured interviews to gather data from a sample of participants. Surveys can be implemented through different channels, such as conducting them in person, over the phone, via mail, or utilizing online platforms. Researchers use various question types, such as multiple-choice, Likert scales, or rating scales, to collect quantitative data on attitudes, opinions, behaviors, and demographics.

- Experiments: Experiments involve manipulating one or more independent variables and measuring their effects on dependent variables. To compare outcomes, participants are assigned randomly to various groups, including control and experimental groups. Experimental designs allow researchers to establish cause-and-effect relationships by controlling for confounding factors.

- Observational Studies: Observational studies involve systematically observing and recording behavior, events, or phenomena in natural settings. Researchers can use structured or unstructured quantitative observation methods , depending on the research objectives. Quantitative data can be collected by counting the frequency of specific behaviors or by using coding systems to categorize and analyze observed data.

- Archival Research: Archival research involves analyzing existing data collected for purposes other than the current study. Researchers may use historical documents, government records, public databases, or organizational records to extract data through quantitative research . Archival research allows for large-scale data analysis and can provide insights into long-term trends and patterns.

- Secondary Data Analysis: Similar to archival research, secondary data analysis involves using existing datasets that were collected by other researchers or organizations. Researchers analyze the data to answer new research questions or test different hypotheses. Secondary data sources can include government surveys, social surveys, or market research data.

- Content Analysis: Content analysis is a method used to analyze textual or visual data to identify patterns, themes, or relationships. Researchers code and categorize the content of documents, interviews, articles, or media sources. The coded data is then quantified and statistically analyzed to draw conclusions. Content analysis can be both qualitative and quantitative , depending on the approach used.

- Psychometric Testing: Psychometric testing involves the development and administration of tests or scales to measure psychological constructs, such as intelligence, personality traits, or attitudes. Researchers use statistical techniques to analyze the test data, such as factor analysis, reliability analysis, or item response theory.

Learn more: What is Quantitative Observation?

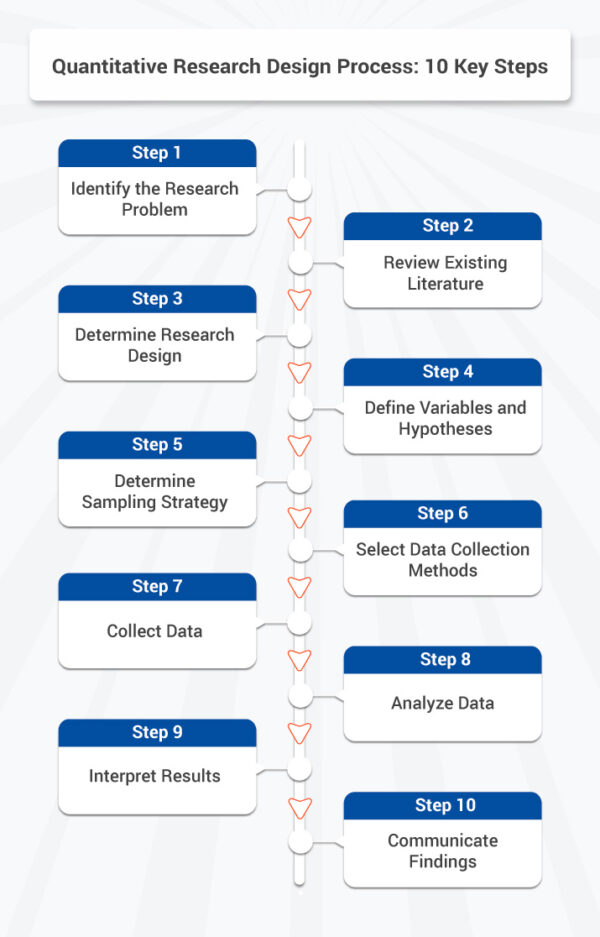

The quantitative research design process typically involves several key steps to ensure a systematic and rigorous approach to data collection and analysis. While the specific steps may vary depending on the research context, here are the key stages commonly involved in quantitative research design:

1. Identify the Research Problem

Clearly define the research problem or objective. Determine the research question(s) and objectives that you want to address through your quantitative research study. Ensure that your research question is specific, measurable, and aligned with your research goals.

2. Review Existing Literature

Conduct a comprehensive review of existing literature and research on the topic. This helps you understand the current state of knowledge, identify gaps in the literature, and inform your research design. It also helps in selecting appropriate variables and developing hypotheses.

3. Determine Research Design

Based on your research question and objectives, determine the appropriate research design. Decide whether an experimental, quasi-experimental, correlational, or another design would best suit your research goals. Consider factors such as feasibility, ethical considerations, and resources available.

4. Define Variables and Hypotheses

Identify the variables that are pertinent to your research question. Clearly define each variable and its operational definitions (how they will be measured or observed). Develop hypotheses that state the expected relationships between variables based on existing theories or prior research.

5. Determine Sampling Strategy

Define the target population for your study and determine the sampling strategy. Decide on the sample size and the sampling method (e.g., random sampling, stratified sampling, convenience sampling). Ensure that your sample is representative of the population you want to generalize your findings to.

6. Select Data Collection Methods

Choose the appropriate data collection methods to gather data through quantitative research . This can include surveys, experiments, observations, or secondary data analysis. Develop or select validated instruments (e.g., questionnaires, scales) for data collection. Perform a pilot test on the instruments to ensure their reliability and validity.

7. Collect Data

Implement your data collection plan. Administer surveys, conduct experiments, observe participants, or extract data from existing sources. Ensure proper data management and organization to maintain accuracy and integrity. Consider ethical considerations and obtain necessary permissions or approvals.

8. Analyze Data

Perform data analysis using appropriate statistical techniques. Depending on your research design and data characteristics, apply descriptive statistics (e.g., means, frequencies) and inferential statistics (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA, regression analysis) to analyze relationships, test hypotheses, and draw conclusions. Use statistical software for efficient and accurate analysis.

9. Interpret Results

Interpret the findings of your data analysis. Examine statistical outputs, identify significant relationships or patterns, and relate them to your research question and hypotheses. Consider the limitations of your study and address any unexpected or contradictory results.

10. Communicate Findings

Prepare a research report or manuscript that summarizes your research process, findings, and conclusions. Present your results in a clear and understandable manner using appropriate visualizations (e.g., tables, graphs). Consider disseminating your findings through academic publications, conferences, or other appropriate channels.

To ensure the quality and validity of your quantitative research design, here are some best practices to consider:

1. Define Research Objectives Clearly: Initiate the process by providing a clear definition of your research objectives and formulating precise research questions. This clarity will guide your study design and data collection process.

2. Conduct a Comprehensive Literature Review: Thoroughly review existing literature and research on your topic to understand the current state of knowledge. This helps you identify research gaps, refine your research question, and avoid duplication of efforts.

3. Use Validated Measures: When selecting or developing measurement instruments, ensure that they have established validity and reliability. Use validated scales, questionnaires, or tests that have been previously tested and proven to measure the constructs of interest accurately.

4. Pilot Testing: Before implementing your data collection, conduct pilot testing to evaluate the effectiveness of your research instruments and procedures. Pilot testing helps identify any issues or shortcomings and allows for adjustments before the main data collection.

5. Ensure Sample Representativeness: Pay attention to sample selection to ensure it is representative of the target population. Use appropriate sampling techniques and consider factors such as sample size, demographics, and relevant characteristics to enhance generalizability.

6. Minimize Nonresponse Bias: Address potential nonresponse bias by employing strategies to maximize response rates, such as providing clear instructions, using follow-up reminders, and ensuring confidentiality. Analyze nonresponse patterns to assess potential bias and consider appropriate weighting techniques if needed.

7. Maintain Data Quality: Implement robust data management practices to ensure data quality and integrity. Conduct data cleaning, perform checks for outliers and missing values, and document any data transformations or manipulations. Document your data collection procedures thoroughly to facilitate replication and transparency.

8. Employ Appropriate Statistical Analysis: Choose statistical techniques that align with your research design and data characteristics. Use appropriate descriptive and inferential statistics to analyze relationships, test hypotheses, and draw valid conclusions. Ensure proper interpretation and reporting of statistical results.

9. Address Potential Confounding Factors: Identify potential confounding variables that may influence the relationship between your independent and dependent variables. Consider controlling for these factors through study design or statistical techniques to isolate the effects of the variables of interest.

10. Consider Ethical Considerations: Adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain necessary approvals or permissions before conducting your research. Protect participants’ rights, ensure informed consent, maintain confidentiality, and handle data responsibly.

11. Document and Report: Document your research design, data collection, and analysis procedures thoroughly. This helps ensure the transparency and reproducibility of your study. Prepare a comprehensive research report or manuscript that clearly presents your methodology, findings, limitations, and implications.

Learn more: What is Quantitative Research?

Enhance Your Research

Collect feedback and conduct research with IdeaScale’s award-winning software

Elevate Research And Feedback With Your IdeaScale Community!

IdeaScale is an innovation management solution that inspires people to take action on their ideas. Your community’s ideas can change lives, your business and the world. Connect to the ideas that matter and start co-creating the future.

Copyright © 2024 IdeaScale

Privacy Overview

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and Analysis

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and Analysis

Table of Contents

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research is a type of research that collects and analyzes numerical data to test hypotheses and answer research questions . This research typically involves a large sample size and uses statistical analysis to make inferences about a population based on the data collected. It often involves the use of surveys, experiments, or other structured data collection methods to gather quantitative data.

Quantitative Research Methods

Quantitative Research Methods are as follows:

Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design is used to describe the characteristics of a population or phenomenon being studied. This research method is used to answer the questions of what, where, when, and how. Descriptive research designs use a variety of methods such as observation, case studies, and surveys to collect data. The data is then analyzed using statistical tools to identify patterns and relationships.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational research design is used to investigate the relationship between two or more variables. Researchers use correlational research to determine whether a relationship exists between variables and to what extent they are related. This research method involves collecting data from a sample and analyzing it using statistical tools such as correlation coefficients.

Quasi-experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is used to investigate cause-and-effect relationships between variables. This research method is similar to experimental research design, but it lacks full control over the independent variable. Researchers use quasi-experimental research designs when it is not feasible or ethical to manipulate the independent variable.

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research design is used to investigate cause-and-effect relationships between variables. This research method involves manipulating the independent variable and observing the effects on the dependent variable. Researchers use experimental research designs to test hypotheses and establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Survey Research

Survey research involves collecting data from a sample of individuals using a standardized questionnaire. This research method is used to gather information on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of individuals. Researchers use survey research to collect data quickly and efficiently from a large sample size. Survey research can be conducted through various methods such as online, phone, mail, or in-person interviews.

Quantitative Research Analysis Methods

Here are some commonly used quantitative research analysis methods:

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis is the most common quantitative research analysis method. It involves using statistical tools and techniques to analyze the numerical data collected during the research process. Statistical analysis can be used to identify patterns, trends, and relationships between variables, and to test hypotheses and theories.

Regression Analysis

Regression analysis is a statistical technique used to analyze the relationship between one dependent variable and one or more independent variables. Researchers use regression analysis to identify and quantify the impact of independent variables on the dependent variable.

Factor Analysis

Factor analysis is a statistical technique used to identify underlying factors that explain the correlations among a set of variables. Researchers use factor analysis to reduce a large number of variables to a smaller set of factors that capture the most important information.

Structural Equation Modeling

Structural equation modeling is a statistical technique used to test complex relationships between variables. It involves specifying a model that includes both observed and unobserved variables, and then using statistical methods to test the fit of the model to the data.

Time Series Analysis

Time series analysis is a statistical technique used to analyze data that is collected over time. It involves identifying patterns and trends in the data, as well as any seasonal or cyclical variations.

Multilevel Modeling

Multilevel modeling is a statistical technique used to analyze data that is nested within multiple levels. For example, researchers might use multilevel modeling to analyze data that is collected from individuals who are nested within groups, such as students nested within schools.

Applications of Quantitative Research

Quantitative research has many applications across a wide range of fields. Here are some common examples:

- Market Research : Quantitative research is used extensively in market research to understand consumer behavior, preferences, and trends. Researchers use surveys, experiments, and other quantitative methods to collect data that can inform marketing strategies, product development, and pricing decisions.

- Health Research: Quantitative research is used in health research to study the effectiveness of medical treatments, identify risk factors for diseases, and track health outcomes over time. Researchers use statistical methods to analyze data from clinical trials, surveys, and other sources to inform medical practice and policy.

- Social Science Research: Quantitative research is used in social science research to study human behavior, attitudes, and social structures. Researchers use surveys, experiments, and other quantitative methods to collect data that can inform social policies, educational programs, and community interventions.

- Education Research: Quantitative research is used in education research to study the effectiveness of teaching methods, assess student learning outcomes, and identify factors that influence student success. Researchers use experimental and quasi-experimental designs, as well as surveys and other quantitative methods, to collect and analyze data.

- Environmental Research: Quantitative research is used in environmental research to study the impact of human activities on the environment, assess the effectiveness of conservation strategies, and identify ways to reduce environmental risks. Researchers use statistical methods to analyze data from field studies, experiments, and other sources.

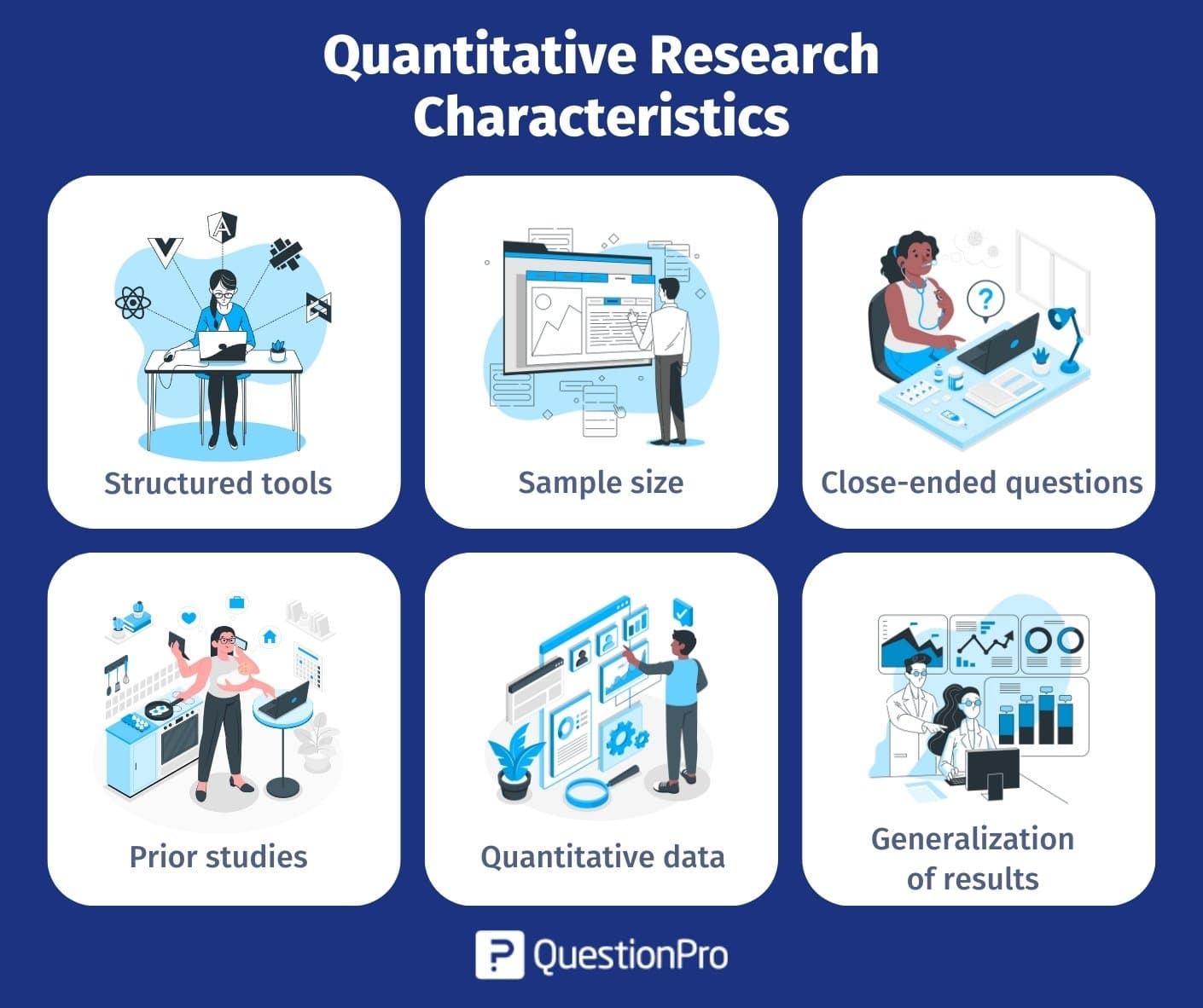

Characteristics of Quantitative Research

Here are some key characteristics of quantitative research:

- Numerical data : Quantitative research involves collecting numerical data through standardized methods such as surveys, experiments, and observational studies. This data is analyzed using statistical methods to identify patterns and relationships.

- Large sample size: Quantitative research often involves collecting data from a large sample of individuals or groups in order to increase the reliability and generalizability of the findings.

- Objective approach: Quantitative research aims to be objective and impartial in its approach, focusing on the collection and analysis of data rather than personal beliefs, opinions, or experiences.

- Control over variables: Quantitative research often involves manipulating variables to test hypotheses and establish cause-and-effect relationships. Researchers aim to control for extraneous variables that may impact the results.

- Replicable : Quantitative research aims to be replicable, meaning that other researchers should be able to conduct similar studies and obtain similar results using the same methods.

- Statistical analysis: Quantitative research involves using statistical tools and techniques to analyze the numerical data collected during the research process. Statistical analysis allows researchers to identify patterns, trends, and relationships between variables, and to test hypotheses and theories.

- Generalizability: Quantitative research aims to produce findings that can be generalized to larger populations beyond the specific sample studied. This is achieved through the use of random sampling methods and statistical inference.

Examples of Quantitative Research

Here are some examples of quantitative research in different fields:

- Market Research: A company conducts a survey of 1000 consumers to determine their brand awareness and preferences. The data is analyzed using statistical methods to identify trends and patterns that can inform marketing strategies.

- Health Research : A researcher conducts a randomized controlled trial to test the effectiveness of a new drug for treating a particular medical condition. The study involves collecting data from a large sample of patients and analyzing the results using statistical methods.

- Social Science Research : A sociologist conducts a survey of 500 people to study attitudes toward immigration in a particular country. The data is analyzed using statistical methods to identify factors that influence these attitudes.

- Education Research: A researcher conducts an experiment to compare the effectiveness of two different teaching methods for improving student learning outcomes. The study involves randomly assigning students to different groups and collecting data on their performance on standardized tests.

- Environmental Research : A team of researchers conduct a study to investigate the impact of climate change on the distribution and abundance of a particular species of plant or animal. The study involves collecting data on environmental factors and population sizes over time and analyzing the results using statistical methods.

- Psychology : A researcher conducts a survey of 500 college students to investigate the relationship between social media use and mental health. The data is analyzed using statistical methods to identify correlations and potential causal relationships.

- Political Science: A team of researchers conducts a study to investigate voter behavior during an election. They use survey methods to collect data on voting patterns, demographics, and political attitudes, and analyze the results using statistical methods.

How to Conduct Quantitative Research

Here is a general overview of how to conduct quantitative research:

- Develop a research question: The first step in conducting quantitative research is to develop a clear and specific research question. This question should be based on a gap in existing knowledge, and should be answerable using quantitative methods.

- Develop a research design: Once you have a research question, you will need to develop a research design. This involves deciding on the appropriate methods to collect data, such as surveys, experiments, or observational studies. You will also need to determine the appropriate sample size, data collection instruments, and data analysis techniques.

- Collect data: The next step is to collect data. This may involve administering surveys or questionnaires, conducting experiments, or gathering data from existing sources. It is important to use standardized methods to ensure that the data is reliable and valid.

- Analyze data : Once the data has been collected, it is time to analyze it. This involves using statistical methods to identify patterns, trends, and relationships between variables. Common statistical techniques include correlation analysis, regression analysis, and hypothesis testing.

- Interpret results: After analyzing the data, you will need to interpret the results. This involves identifying the key findings, determining their significance, and drawing conclusions based on the data.

- Communicate findings: Finally, you will need to communicate your findings. This may involve writing a research report, presenting at a conference, or publishing in a peer-reviewed journal. It is important to clearly communicate the research question, methods, results, and conclusions to ensure that others can understand and replicate your research.

When to use Quantitative Research

Here are some situations when quantitative research can be appropriate:

- To test a hypothesis: Quantitative research is often used to test a hypothesis or a theory. It involves collecting numerical data and using statistical analysis to determine if the data supports or refutes the hypothesis.

- To generalize findings: If you want to generalize the findings of your study to a larger population, quantitative research can be useful. This is because it allows you to collect numerical data from a representative sample of the population and use statistical analysis to make inferences about the population as a whole.

- To measure relationships between variables: If you want to measure the relationship between two or more variables, such as the relationship between age and income, or between education level and job satisfaction, quantitative research can be useful. It allows you to collect numerical data on both variables and use statistical analysis to determine the strength and direction of the relationship.

- To identify patterns or trends: Quantitative research can be useful for identifying patterns or trends in data. For example, you can use quantitative research to identify trends in consumer behavior or to identify patterns in stock market data.

- To quantify attitudes or opinions : If you want to measure attitudes or opinions on a particular topic, quantitative research can be useful. It allows you to collect numerical data using surveys or questionnaires and analyze the data using statistical methods to determine the prevalence of certain attitudes or opinions.

Purpose of Quantitative Research

The purpose of quantitative research is to systematically investigate and measure the relationships between variables or phenomena using numerical data and statistical analysis. The main objectives of quantitative research include:

- Description : To provide a detailed and accurate description of a particular phenomenon or population.

- Explanation : To explain the reasons for the occurrence of a particular phenomenon, such as identifying the factors that influence a behavior or attitude.

- Prediction : To predict future trends or behaviors based on past patterns and relationships between variables.

- Control : To identify the best strategies for controlling or influencing a particular outcome or behavior.

Quantitative research is used in many different fields, including social sciences, business, engineering, and health sciences. It can be used to investigate a wide range of phenomena, from human behavior and attitudes to physical and biological processes. The purpose of quantitative research is to provide reliable and valid data that can be used to inform decision-making and improve understanding of the world around us.

Advantages of Quantitative Research

There are several advantages of quantitative research, including:

- Objectivity : Quantitative research is based on objective data and statistical analysis, which reduces the potential for bias or subjectivity in the research process.

- Reproducibility : Because quantitative research involves standardized methods and measurements, it is more likely to be reproducible and reliable.

- Generalizability : Quantitative research allows for generalizations to be made about a population based on a representative sample, which can inform decision-making and policy development.

- Precision : Quantitative research allows for precise measurement and analysis of data, which can provide a more accurate understanding of phenomena and relationships between variables.

- Efficiency : Quantitative research can be conducted relatively quickly and efficiently, especially when compared to qualitative research, which may involve lengthy data collection and analysis.

- Large sample sizes : Quantitative research can accommodate large sample sizes, which can increase the representativeness and generalizability of the results.

Limitations of Quantitative Research

There are several limitations of quantitative research, including:

- Limited understanding of context: Quantitative research typically focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis, which may not provide a comprehensive understanding of the context or underlying factors that influence a phenomenon.

- Simplification of complex phenomena: Quantitative research often involves simplifying complex phenomena into measurable variables, which may not capture the full complexity of the phenomenon being studied.

- Potential for researcher bias: Although quantitative research aims to be objective, there is still the potential for researcher bias in areas such as sampling, data collection, and data analysis.

- Limited ability to explore new ideas: Quantitative research is often based on pre-determined research questions and hypotheses, which may limit the ability to explore new ideas or unexpected findings.

- Limited ability to capture subjective experiences : Quantitative research is typically focused on objective data and may not capture the subjective experiences of individuals or groups being studied.

- Ethical concerns : Quantitative research may raise ethical concerns, such as invasion of privacy or the potential for harm to participants.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types...

Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Basic Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Exploratory Research – Types, Methods and...

Quantitative and Qualitative Research

- I NEED TO . . .

What is Quantitative Research?

- What is Qualitative Research?

- Quantitative vs Qualitative

- Step 1: Accessing CINAHL

- Step 2: Create a Keyword Search

- Step 3: Create a Subject Heading Search

- Step 4: Repeat Steps 1-3 for Second Concept

- Step 5: Repeat Steps 1-3 for Quantitative Terms

- Step 6: Combining All Searches

- Step 7: Adding Limiters

- Step 8: Save Your Search!

- What Kind of Article is This?

- More Research Help This link opens in a new window

Quantitative methodology is the dominant research framework in the social sciences. It refers to a set of strategies, techniques and assumptions used to study psychological, social and economic processes through the exploration of numeric patterns . Quantitative research gathers a range of numeric data. Some of the numeric data is intrinsically quantitative (e.g. personal income), while in other cases the numeric structure is imposed (e.g. ‘On a scale from 1 to 10, how depressed did you feel last week?’). The collection of quantitative information allows researchers to conduct simple to extremely sophisticated statistical analyses that aggregate the data (e.g. averages, percentages), show relationships among the data (e.g. ‘Students with lower grade point averages tend to score lower on a depression scale’) or compare across aggregated data (e.g. the USA has a higher gross domestic product than Spain). Quantitative research includes methodologies such as questionnaires, structured observations or experiments and stands in contrast to qualitative research. Qualitative research involves the collection and analysis of narratives and/or open-ended observations through methodologies such as interviews, focus groups or ethnographies.

Coghlan, D., Brydon-Miller, M. (2014). The SAGE encyclopedia of action research (Vols. 1-2). London, : SAGE Publications Ltd doi: 10.4135/9781446294406

What is the purpose of quantitative research?

The purpose of quantitative research is to generate knowledge and create understanding about the social world. Quantitative research is used by social scientists, including communication researchers, to observe phenomena or occurrences affecting individuals. Social scientists are concerned with the study of people. Quantitative research is a way to learn about a particular group of people, known as a sample population. Using scientific inquiry, quantitative research relies on data that are observed or measured to examine questions about the sample population.

Allen, M. (2017). The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods (Vols. 1-4). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc doi: 10.4135/9781483381411

How do I know if the study is a quantitative design? What type of quantitative study is it?

Quantitative Research Designs: Descriptive non-experimental, Quasi-experimental or Experimental?

Studies do not always explicitly state what kind of research design is being used. You will need to know how to decipher which design type is used. The following video will help you determine the quantitative design type.

- << Previous: I NEED TO . . .

- Next: What is Qualitative Research? >>

- Last Updated: Dec 8, 2023 10:05 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uta.edu/quantitative_and_qualitative_research

University of Texas Arlington Libraries 702 Planetarium Place · Arlington, TX 76019 · 817-272-3000

- Internet Privacy

- Accessibility

- Problems with a guide? Contact Us.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition & Methods

What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition & Methods

Published on 4 April 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Quantitative research is the process of collecting and analysing numerical data. It can be used to find patterns and averages, make predictions, test causal relationships, and generalise results to wider populations.

Quantitative research is the opposite of qualitative research , which involves collecting and analysing non-numerical data (e.g. text, video, or audio).

Quantitative research is widely used in the natural and social sciences: biology, chemistry, psychology, economics, sociology, marketing, etc.

- What is the demographic makeup of Singapore in 2020?

- How has the average temperature changed globally over the last century?

- Does environmental pollution affect the prevalence of honey bees?

- Does working from home increase productivity for people with long commutes?

Table of contents

Quantitative research methods, quantitative data analysis, advantages of quantitative research, disadvantages of quantitative research, frequently asked questions about quantitative research.

You can use quantitative research methods for descriptive, correlational or experimental research.

- In descriptive research , you simply seek an overall summary of your study variables.

- In correlational research , you investigate relationships between your study variables.

- In experimental research , you systematically examine whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship between variables.

Correlational and experimental research can both be used to formally test hypotheses , or predictions, using statistics. The results may be generalised to broader populations based on the sampling method used.

To collect quantitative data, you will often need to use operational definitions that translate abstract concepts (e.g., mood) into observable and quantifiable measures (e.g., self-ratings of feelings and energy levels).

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once data is collected, you may need to process it before it can be analysed. For example, survey and test data may need to be transformed from words to numbers. Then, you can use statistical analysis to answer your research questions .

Descriptive statistics will give you a summary of your data and include measures of averages and variability. You can also use graphs, scatter plots and frequency tables to visualise your data and check for any trends or outliers.

Using inferential statistics , you can make predictions or generalisations based on your data. You can test your hypothesis or use your sample data to estimate the population parameter .

You can also assess the reliability and validity of your data collection methods to indicate how consistently and accurately your methods actually measured what you wanted them to.

Quantitative research is often used to standardise data collection and generalise findings . Strengths of this approach include:

- Replication

Repeating the study is possible because of standardised data collection protocols and tangible definitions of abstract concepts.

- Direct comparisons of results

The study can be reproduced in other cultural settings, times or with different groups of participants. Results can be compared statistically.

- Large samples

Data from large samples can be processed and analysed using reliable and consistent procedures through quantitative data analysis.

- Hypothesis testing

Using formalised and established hypothesis testing procedures means that you have to carefully consider and report your research variables, predictions, data collection and testing methods before coming to a conclusion.

Despite the benefits of quantitative research, it is sometimes inadequate in explaining complex research topics. Its limitations include:

- Superficiality

Using precise and restrictive operational definitions may inadequately represent complex concepts. For example, the concept of mood may be represented with just a number in quantitative research, but explained with elaboration in qualitative research.

- Narrow focus

Predetermined variables and measurement procedures can mean that you ignore other relevant observations.

- Structural bias

Despite standardised procedures, structural biases can still affect quantitative research. Missing data , imprecise measurements or inappropriate sampling methods are biases that can lead to the wrong conclusions.

- Lack of context

Quantitative research often uses unnatural settings like laboratories or fails to consider historical and cultural contexts that may affect data collection and results.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organisations.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

Reliability and validity are both about how well a method measures something:

- Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure (whether the results can be reproduced under the same conditions).

- Validity refers to the accuracy of a measure (whether the results really do represent what they are supposed to measure).

If you are doing experimental research , you also have to consider the internal and external validity of your experiment.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2022, October 10). What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 11 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/introduction-to-quantitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Research Design and Methods An Applied Guide for the Scholar-Practitioner

- Gary J. Burkholder - Walden University, USA

- Kimberley A. Cox - Walden University, USA

- Linda M. Crawford - Walden University, USA

- John H. Hitchcock - Abt Associates Inc., USA

- Description

Research Design and Methods: An Applied Guide for the Scholar-Practitioner is written for students seeking advanced degrees who want to use evidence-based research to support their practice. This practical and accessible text addresses the foundational concepts of research design and methods; provides a more detailed exploration of designs and approaches popular with graduate students in applied disciplines; covers qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods designs; discusses ethical considerations and quality in research; and provides guidance on writing a research proposal.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Supplements

- Editable, chapter-specific Microsoft® PowerPoint® slides offer you complete flexibility in easily creating a multimedia presentation for your course.

- Lecture Notes , including Outline and Objectives, which may be used for lecture and/or student handouts.

- Case studies from SAGE Research Methods accompanied by critical thinking/discussion questions.

- Tables and figures from the printed book are available in an easily-downloadable format for use in papers, hand-outs, and presentations.

“The chapters in this text are logically and clearly organized around levels of understanding that are intuitive and easy to follow. They offer dynamic examples that will keep students engaged. Readers will learn to connect theory and practice, helping them become better researchers, and better consumers of research.”

“ Research Design and Methods: An Applied Guide for the Scholar-Practitioner is a must-read for both new and seasoned researchers. Every topic in the text is comprehensively explained with excellent examples.”

“This text provides clear and concise discussions of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research for the new scholar-practitioner. The use of questioning and visuals affords students the opportunity to make connections and reflect on their learning.”

“The edited nature of this book provides a multitude of rich perspectives from well-respected authors. This book is a must-have for introductory research methods students.”

“This is an excellent read for anyone interested in understanding research, the book provides good clarity and practical examples…. It is a pragmatic book that translates research concepts into practice.”

Clear chapters. Acessible format

It contains most of what I needed for my Research Methods class. Very good book!

Current book looks better to teach.

A user-friendly, relevant, and applicable resource for all scholar-practitioners.

- The authors are highly experienced experts in the field who are skilled in translating difficult concepts into straightforward examples.

- The text is comprehensive in its coverage of research design and methods across multiple courses , working well as a beginning or intermediate text for a research design course or as a supplementary text in related courses.

- Complementary chapters on qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods data analysis show readers how to holistically apply what they’ve learned about research design to data analysis.

- A chapter on writing a research proposal ensures that readers develop their skills for formulating their research ideas in proposal form.

- Questions for Reflection, and Key Sources for further reading are included at the end of each chapter.

Sample Materials & Chapters

3: Conceptual and Theoretical Frameworks in Research

16: Applied Research: Action Research

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

Research Methods and Design

- Action Research

- Case Study Design

- Literature Review

- Quantitative Research Methods

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Mixed Methods Study

- Indigenous Research and Ethics This link opens in a new window

- Identifying Empirical Research Articles This link opens in a new window

- Research Ethics and Quality

- Data Literacy

- Get Help with Writing Assignments

Quantitative research methods

a method of research that relies on measuring variables using a numerical system, analyzing these measurements using any of a variety of statistical models, and reporting relationships and associations among the studied variables. For example, these variables may be test scores or measurements of reaction time. The goal of gathering this quantitative data is to understand, describe, and predict the nature of a phenomenon, particularly through the development of models and theories. Quantitative research techniques include experiments and surveys.

SAGE Research Methods Videos

What are the strengths of quantitative research.

Professor Norma T. Mertz briefly discusses qualitative research and how it has changed since she entered the field. She emphasizes the importance of defining a research question before choosing a theoretical approach to research.

This is just one segment in a series about quantitative methods. You can find additional videos in our SAGE database, Research Methods:

Videos covering research methods and statistics

Further Reading

- << Previous: Literature Review

- Next: Qualitative Research Methods >>

- Last Updated: Feb 6, 2024 9:20 AM

CityU Home - CityU Catalog

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions and hypotheses are developed according to the type of research, which can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative research. We provide a summary of the types of research questions and hypotheses under quantitative and qualitative research categories in Table 1 .

Research questions in quantitative research

In quantitative research, research questions inquire about the relationships among variables being investigated and are usually framed at the start of the study. These are precise and typically linked to the subject population, dependent and independent variables, and research design. 1 Research questions may also attempt to describe the behavior of a population in relation to one or more variables, or describe the characteristics of variables to be measured ( descriptive research questions ). 1 , 5 , 14 These questions may also aim to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable ( comparative research questions ), 1 , 5 , 14 or elucidate trends and interactions among variables ( relationship research questions ). 1 , 5 We provide examples of descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions in quantitative research in Table 2 .

Hypotheses in quantitative research

In quantitative research, hypotheses predict the expected relationships among variables. 15 Relationships among variables that can be predicted include 1) between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable ( simple hypothesis ) or 2) between two or more independent and dependent variables ( complex hypothesis ). 4 , 11 Hypotheses may also specify the expected direction to be followed and imply an intellectual commitment to a particular outcome ( directional hypothesis ) 4 . On the other hand, hypotheses may not predict the exact direction and are used in the absence of a theory, or when findings contradict previous studies ( non-directional hypothesis ). 4 In addition, hypotheses can 1) define interdependency between variables ( associative hypothesis ), 4 2) propose an effect on the dependent variable from manipulation of the independent variable ( causal hypothesis ), 4 3) state a negative relationship between two variables ( null hypothesis ), 4 , 11 , 15 4) replace the working hypothesis if rejected ( alternative hypothesis ), 15 explain the relationship of phenomena to possibly generate a theory ( working hypothesis ), 11 5) involve quantifiable variables that can be tested statistically ( statistical hypothesis ), 11 6) or express a relationship whose interlinks can be verified logically ( logical hypothesis ). 11 We provide examples of simple, complex, directional, non-directional, associative, causal, null, alternative, working, statistical, and logical hypotheses in quantitative research, as well as the definition of quantitative hypothesis-testing research in Table 3 .

Research questions in qualitative research

Unlike research questions in quantitative research, research questions in qualitative research are usually continuously reviewed and reformulated. The central question and associated subquestions are stated more than the hypotheses. 15 The central question broadly explores a complex set of factors surrounding the central phenomenon, aiming to present the varied perspectives of participants. 15

There are varied goals for which qualitative research questions are developed. These questions can function in several ways, such as to 1) identify and describe existing conditions ( contextual research question s); 2) describe a phenomenon ( descriptive research questions ); 3) assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures ( evaluation research questions ); 4) examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena ( explanatory research questions ); or 5) focus on unknown aspects of a particular topic ( exploratory research questions ). 5 In addition, some qualitative research questions provide new ideas for the development of theories and actions ( generative research questions ) or advance specific ideologies of a position ( ideological research questions ). 1 Other qualitative research questions may build on a body of existing literature and become working guidelines ( ethnographic research questions ). Research questions may also be broadly stated without specific reference to the existing literature or a typology of questions ( phenomenological research questions ), may be directed towards generating a theory of some process ( grounded theory questions ), or may address a description of the case and the emerging themes ( qualitative case study questions ). 15 We provide examples of contextual, descriptive, evaluation, explanatory, exploratory, generative, ideological, ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and qualitative case study research questions in qualitative research in Table 4 , and the definition of qualitative hypothesis-generating research in Table 5 .

Qualitative studies usually pose at least one central research question and several subquestions starting with How or What . These research questions use exploratory verbs such as explore or describe . These also focus on one central phenomenon of interest, and may mention the participants and research site. 15

Hypotheses in qualitative research

Hypotheses in qualitative research are stated in the form of a clear statement concerning the problem to be investigated. Unlike in quantitative research where hypotheses are usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes. 2 When studies require both quantitative and qualitative research questions, this suggests an integrative process between both research methods wherein a single mixed-methods research question can be developed. 1

FRAMEWORKS FOR DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions followed by hypotheses should be developed before the start of the study. 1 , 12 , 14 It is crucial to develop feasible research questions on a topic that is interesting to both the researcher and the scientific community. This can be achieved by a meticulous review of previous and current studies to establish a novel topic. Specific areas are subsequently focused on to generate ethical research questions. The relevance of the research questions is evaluated in terms of clarity of the resulting data, specificity of the methodology, objectivity of the outcome, depth of the research, and impact of the study. 1 , 5 These aspects constitute the FINER criteria (i.e., Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant). 1 Clarity and effectiveness are achieved if research questions meet the FINER criteria. In addition to the FINER criteria, Ratan et al. described focus, complexity, novelty, feasibility, and measurability for evaluating the effectiveness of research questions. 14

The PICOT and PEO frameworks are also used when developing research questions. 1 The following elements are addressed in these frameworks, PICOT: P-population/patients/problem, I-intervention or indicator being studied, C-comparison group, O-outcome of interest, and T-timeframe of the study; PEO: P-population being studied, E-exposure to preexisting conditions, and O-outcome of interest. 1 Research questions are also considered good if these meet the “FINERMAPS” framework: Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant, Manageable, Appropriate, Potential value/publishable, and Systematic. 14

As we indicated earlier, research questions and hypotheses that are not carefully formulated result in unethical studies or poor outcomes. To illustrate this, we provide some examples of ambiguous research question and hypotheses that result in unclear and weak research objectives in quantitative research ( Table 6 ) 16 and qualitative research ( Table 7 ) 17 , and how to transform these ambiguous research question(s) and hypothesis(es) into clear and good statements.

a These statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

b These statements are direct quotes from Higashihara and Horiuchi. 16

a This statement is a direct quote from Shimoda et al. 17

The other statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

CONSTRUCTING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

To construct effective research questions and hypotheses, it is very important to 1) clarify the background and 2) identify the research problem at the outset of the research, within a specific timeframe. 9 Then, 3) review or conduct preliminary research to collect all available knowledge about the possible research questions by studying theories and previous studies. 18 Afterwards, 4) construct research questions to investigate the research problem. Identify variables to be accessed from the research questions 4 and make operational definitions of constructs from the research problem and questions. Thereafter, 5) construct specific deductive or inductive predictions in the form of hypotheses. 4 Finally, 6) state the study aims . This general flow for constructing effective research questions and hypotheses prior to conducting research is shown in Fig. 1 .

Research questions are used more frequently in qualitative research than objectives or hypotheses. 3 These questions seek to discover, understand, explore or describe experiences by asking “What” or “How.” The questions are open-ended to elicit a description rather than to relate variables or compare groups. The questions are continually reviewed, reformulated, and changed during the qualitative study. 3 Research questions are also used more frequently in survey projects than hypotheses in experiments in quantitative research to compare variables and their relationships.

Hypotheses are constructed based on the variables identified and as an if-then statement, following the template, ‘If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.’ At this stage, some ideas regarding expectations from the research to be conducted must be drawn. 18 Then, the variables to be manipulated (independent) and influenced (dependent) are defined. 4 Thereafter, the hypothesis is stated and refined, and reproducible data tailored to the hypothesis are identified, collected, and analyzed. 4 The hypotheses must be testable and specific, 18 and should describe the variables and their relationships, the specific group being studied, and the predicted research outcome. 18 Hypotheses construction involves a testable proposition to be deduced from theory, and independent and dependent variables to be separated and measured separately. 3 Therefore, good hypotheses must be based on good research questions constructed at the start of a study or trial. 12