"How Do I?" @JWULibrary

Sample Question

- JWU-Providence Library

Q. What's the difference between a research article and a review article?

- 35 about the library

- 28 articles & journals

- 1 Borrowing

- 9 citing sources

- 17 company & industry

- 11 computers

- 1 copyright compliance

- 5 countries & travel

- 2 course registration

- 10 culinary

- 51 databases

- 3 education

- 2 Interlibrary loan

- 5 job search

- 6 libguides

- 9 market research

- 25 my library account

- 12 requests

- 24 research basics

- 18 research topics

- 2 study rooms

- 16 technology

- 7 textbooks

- 42 university

- 3 video tutorial

- 1 writing_help

Answered By: Sarah Naomi Campbell Last Updated: Sep 07, 2018 Views: 212532

Watch this short video to learn about types of scholarly articles, including research articles and literature reviews!

Not in the mood for a video? Read on!

What's the difference between a research article and a review article?

Research articles , sometimes referred to as empirical or primary sources , report on original research. They will typically include sections such as an introduction, methods, results, and discussion.

Here is a more detailed explanation of research articles .

Review articles , sometimes called literature reviews or secondary sources , synthesize or analyze research already conducted in primary sources. They generally summarize the current state of research on a given topic.

Here is a more detailed explanation of review articles .

The video above was created by the Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries .

The defintions, and the linked detailed explanations, are paraphrased from the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 6th ed .

The linked explanations are provided by the Mohawk Valley Community College Libraries .

Links & Files

- How do I find empirical articles in the library databases?

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 63 No 19

Comments (0)

Related topics.

- about the library

- articles & journals

- citing sources

- company & industry

- copyright compliance

- countries & travel

- course registration

- Interlibrary loan

- market research

- my library account

- research basics

- research topics

- study rooms

- video tutorial

- writing_help

Downcity Library:

111 Dorrance Street Providence, Rhode Island 02903

401-598-1121

Harborside Library:

321 Harborside Boulevard Providence, RI 02905

401-598-1466

- Location and Directions

- Off-Campus Access

- Staff Directory

- Student Employment

- Pay Bills and Fines

- Chat with a Librarian

- Course Reserves

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Study Rooms

- Research Appointment

- Culinary Museum

- Study resources

- Calendar - Graduate

- Calendar - Undergraduate

- Class schedules

- Class cancellations

- Course registration

- Important academic dates

- More academic resources

- Campus services

- IT services

- Job opportunities

- Safety & prevention

- Mental health support

- Student Service Centre (Birks)

- All campus services

- Calendar of events

- Latest news

- Media Relations

- Faculties, Schools & Colleges

- Arts and Science

- Gina Cody School of Engineering and Computer Science

- John Molson School of Business

- School of Graduate Studies

- All Schools, Colleges & Departments.

- Directories

- My Library account Renew books and more

- Book a study room or scanner Reserve a space for your group online

- Interlibrary loans (Colombo) Request books from external libraries

- Zotero (formerly RefWorks) Manage your citations and create bibliographies

- Article/Chapter Scan & Deliver Request a PDF of an article/chapter we have in our physical collection

- Contactless Book Pickup Request books, DVDs and more from our physical collection while the Library is closed

- WebPrint Upload documents to print on campus

- Course reserves Online course readings

- Spectrum Deposit a thesis or article

- Sofia Discovery tool

- Databases by subject

- Course Reserves

- E-journals via Browzine

- E-journals via Sofia

- Article/chapter scan

- Intercampus delivery of bound periodicals/microforms

- Interlibrary loans

- Spectrum Research Repository

- Special Collections

- Additional resources & services

- Subject & course guides

- Open Educational Resources Guide

- Borrowing & renewing

- General guides for users

- Evaluating...

- Ask a librarian

- Research Skills Tutorial

- Bibliometrics & research impact guide

- Concordia University Press

- Copyright guide

- Copyright guide for thesis preparation

- Digital scholarship

- Digital preservation

- Open Access

- ORCiD at Concordia

- Research data management guide

- Scholarship of Teaching & Learning

- Systematic Reviews

- Borrow (laptops, tablets, equipment)

- Connect (netname, Wi-Fi, guest accounts)

- Desktop computers, software & availability maps

- Group study, presentation practice & classrooms

- Printers, copiers & scanners

- Technology Sandbox

- Visualization Studio

- Webster Library

- Vanier Library

- Grey Nuns Reading Room

- Study spaces

- Floor plans

- Book a group study room/scanner

- Room booking for academic events

- Exhibitions

- Librarians & staff

- Work with us

- Memberships & collaborations

- Indigenous Student Librarian program

- Wikipedian in residence

- Researcher in residence

- Feedback & improvement

- Annual reports & fast facts

- Strategic Plan 2016/21

- Library Services Fund

- Giving to the Library

- Policies & Code of Conduct

- My Library account

- Book a study room or scanner

- Interlibrary loans (Colombo)

- Zotero (formerly RefWorks)

- Article/Chapter Scan & Deliver

- Contactless Book Pickup

- Course reserves

Review vs. Research Articles

How can you tell if you are looking at a research paper, review paper or a systematic review examples and article characteristics are provided below to help you figure it out., research papers.

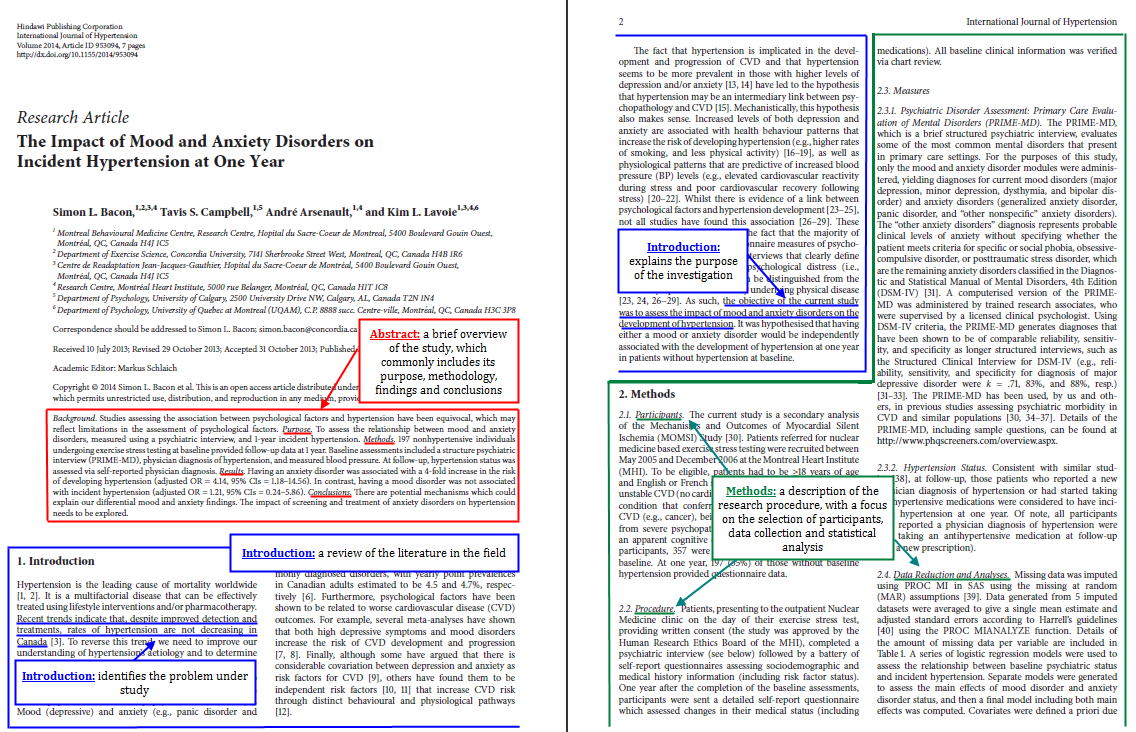

A research article describes a study that was performed by the article’s author(s). It explains the methodology of the study, such as how data was collected and analyzed, and clarifies what the results mean. Each step of the study is reported in detail so that other researchers can repeat the experiment.

To determine if a paper is a research article, examine its wording. Research articles describe actions taken by the researcher(s) during the experimental process. Look for statements like “we tested,” “I measured,” or “we investigated.” Research articles also describe the outcomes of studies. Check for phrases like “the study found” or “the results indicate.” Next, look closely at the formatting of the article. Research papers are divided into sections that occur in a particular order: abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and references.

Let's take a closer look at this research paper by Bacon et al. published in the International Journal of Hypertension :

Review Papers

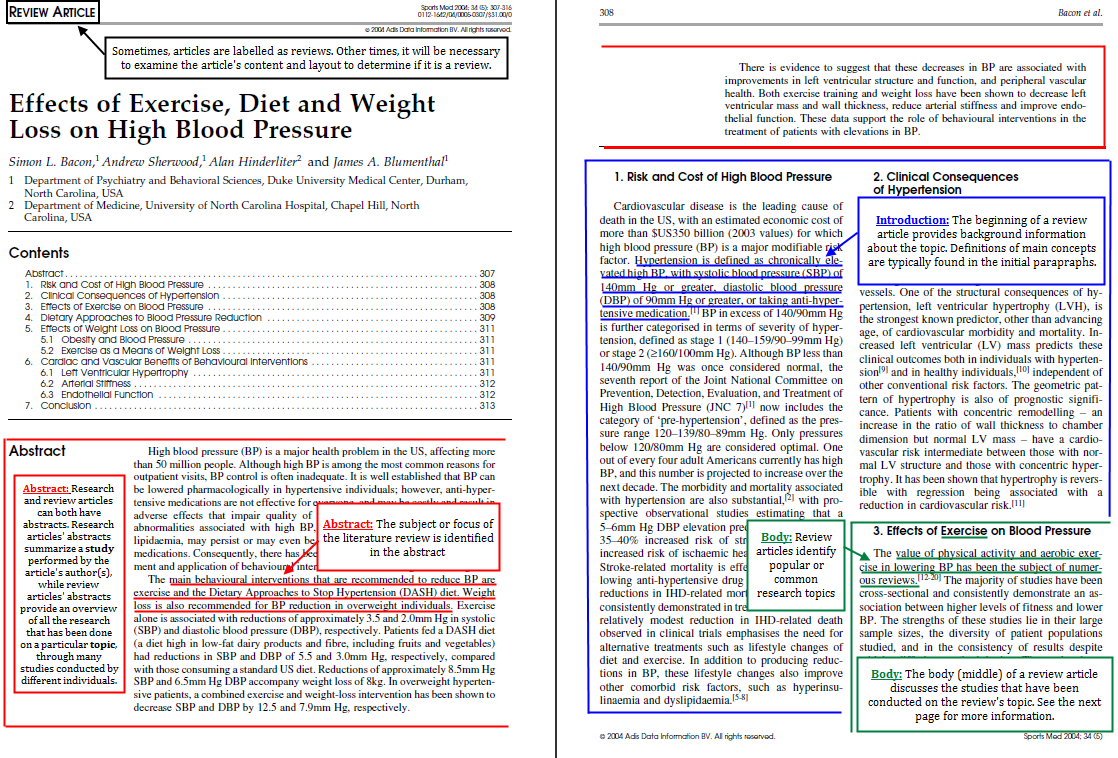

Review articles do not describe original research conducted by the author(s). Instead, they give an overview of a specific subject by examining previously published studies on the topic. The author searches for and selects studies on the subject and then tries to make sense of their findings. In particular, review articles look at whether the outcomes of the chosen studies are similar, and if they are not, attempt to explain the conflicting results. By interpreting the findings of previous studies, review articles are able to present the current knowledge and understanding of a specific topic.

Since review articles summarize the research on a particular topic, students should read them for background information before consulting detailed, technical research articles. Furthermore, review articles are a useful starting point for a research project because their reference lists can be used to find additional articles on the subject.

Let's take a closer look at this review paper by Bacon et al. published in Sports Medicine :

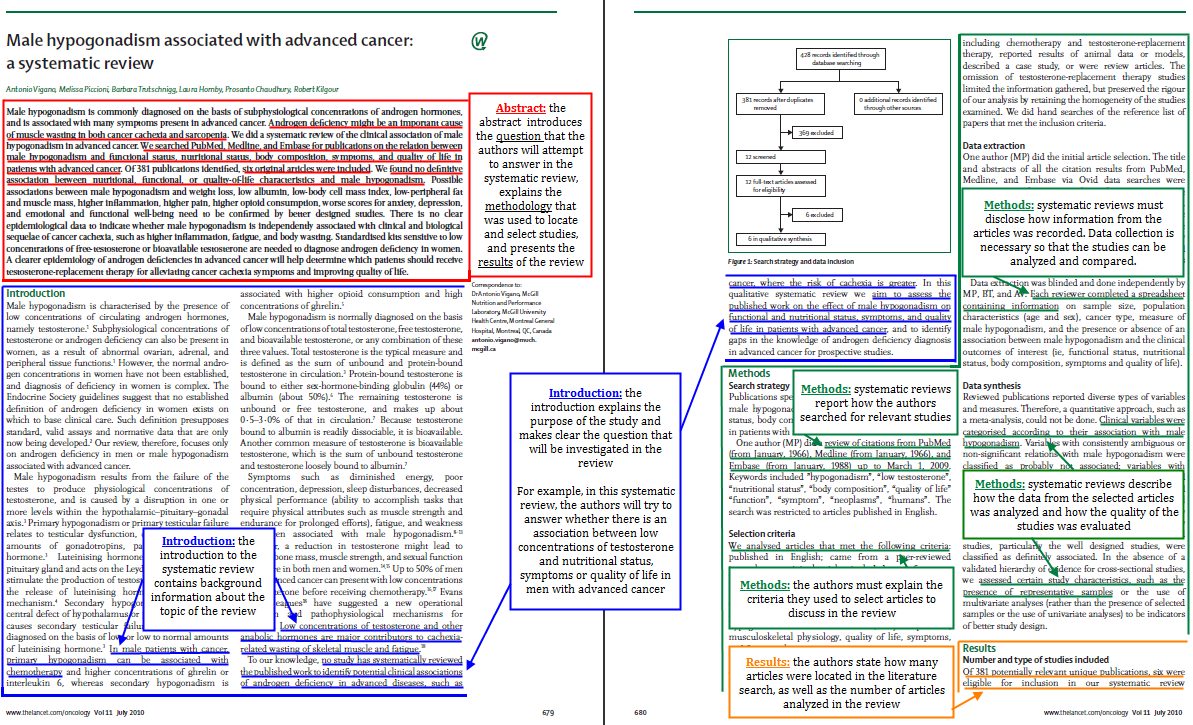

Systematic Review Papers

A systematic review is a type of review article that tries to limit the occurrence of bias. Traditional, non-systematic reviews can be biased because they do not include all of the available papers on the review’s topic; only certain studies are discussed by the author. No formal process is used to decide which articles to include in the review. Consequently, unpublished articles, older papers, works in foreign languages, manuscripts published in small journals, and studies that conflict with the author’s beliefs can be overlooked or excluded. Since traditional reviews do not have to explain the techniques used to select the studies, it can be difficult to determine if the author’s bias affected the review’s findings.

Systematic reviews were developed to address the problem of bias. Unlike traditional reviews, which cover a broad topic, systematic reviews focus on a single question, such as if a particular intervention successfully treats a medical condition. Systematic reviews then track down all of the available studies that address the question, choose some to include in the review, and critique them using predetermined criteria. The studies are found, selected, and evaluated using a formal, scientific methodology in order to minimize the effect of the author’s bias. The methodology is clearly explained in the systematic review so that readers can form opinions about the quality of the review.

Let's take a closer look this systematic review paper by Vigano et al. published in Lancet Oncology :

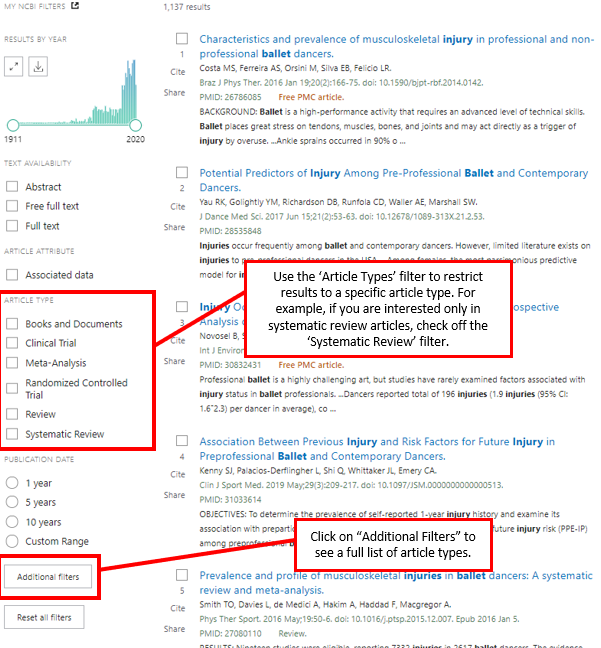

Finding Review and Research Papers in PubMed

Many databases have special features that allow the searcher to restrict results to articles that match specific criteria. In other words, only articles of a certain type will be displayed in the search results. These “limiters” can be useful when searching for research or review articles. PubMed has a limiter for article type, which is located on the left sidebar of the search results page. This limiter can filter the search results to show only review articles.

© Concordia University

NFS 4021 Contemporary Topics in Nutrition: Research Articles vs Review Articles

- Research Articles vs Review Articles

- Citation Help

Agriculture Support Librarian

Research Articles and Review Articles Defined Review

"A research article is a primary source ...that is, it reports the methods and results of an original study performed by the authors . The kind of study may vary (it could have been an experiment, survey, interview, etc.), but in all cases, raw data have been collected and analyzed by the authors, and conclusions drawn from the results of that analysis.

A review article is a secondary source ...it is written about other articles, and does not report original research of its own. Review articles are very important, as they draw upon the articles that they review to suggest new research directions, to strengthen support for existing theories and/or identify patterns among existing research studies. For student researchers, review articles provide a great overview of the existing literature on a topic. If you find a literature review that fits your topic, take a look at its references/works cited list for leads on other relevant articles and books!"

From https://apus.libanswers.com/faq/2324 , "What's the difference between a research and a review article?"

- Example of a RESEARCH Article Lin CL, Huang LC, Chang YT, Chen RY, Yang SH. Effectiveness of Health Coaching in Diabetes Control and Lifestyle Improvement: A Randomized-Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2021 Oct 29;13(11):3878.

- Example of a REVIEW Article Ojo O, Ojo OO, Adebowale F, Wang XH. The Effect of Dietary Glycaemic Index on Glycaemia in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients. 2018 Mar 19;10(3):373.

Difference between Reviews and Research Articles

Research Article Break Down Review

Research articles follow a particular format. Look for:

- A brief introduction will often include a review of the existing literature on the topic studied, and explain the rationale of the author's study.

- A methods section, where authors describe how they collected and analyzed data. Statistical analysis are included.

- A results section describes the outcomes of the data analysis. Charts and graphs illustrating the results are typically included.

- In the discussion , authors will explain their interpretation of their results and theorize on their importance to existing and future research.

- References or works cited are always included. These are the articles and books that the authors drew upon to plan their study and to support their discussion.

- << Previous: Welcome

- Next: Databases >>

- Last Updated: Mar 1, 2024 11:14 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.lsu.edu/NFS4021

Provide Website Feedback Accessibility Statement

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Review Article vs Research Article

Review Article vs Research Article

Table of Contents

Review articles and Research Articles are two different types of scholarly publications that serve distinct purposes in the academic literature.

Research Articles

A Research Article is a primary source that presents original research findings based on a specific research question or hypothesis. These articles typically follow a standard format that includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion sections. Research articles often include detailed descriptions of the research design, data collection and analysis procedures, and the results of statistical tests. These articles are typically peer-reviewed to ensure that they meet rigorous scientific standards before publication.

Review Articles

A Review Article is a secondary source that summarizes and analyzes existing research on a particular topic or research question. These articles provide an overview of the current state of knowledge on a particular topic, including a critical analysis of the strengths and limitations of previous research. Review articles often include a meta-analysis of the existing literature, which involves combining and analyzing data from multiple studies to draw more general conclusions about the research question or topic. Review articles are also typically peer-reviewed to ensure that they are comprehensive, accurate, and up-to-date.

Difference Between Review Article and Research Article

Here are some key differences between review articles and research articles:

In summary, research articles and review articles serve different purposes in the academic literature. Research articles present original research findings based on a specific research question or hypothesis, while review articles summarize and analyze existing research on a particular topic or research question. Both types of articles are typically peer-reviewed to ensure that they meet high standards of scientific rigor and accuracy.

Also see Research Methods

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Qualitative Vs Quantitative Research

Generative Vs Evaluative Research

Market Research Vs Marketing Research

Longitudinal Vs Cross-Sectional Research

Descriptive vs Experimental Research

Primary Vs Secondary Research

What Is The Difference Between A Scholarly Research Article And A Review Article?

If you are new in the academic world, you may find the types of academic articles dizziying. The more common ones include research articles, and also review articles. How are they similar and different from each other? Distinguishing between research and review articles is crucial.

In this post, let’s explore what research and review articles are, and how are they different.

Research Article vs. Review Article

What is a research article .

A research article serves as the cornerstone of the academic and scientific community, standing as a detailed report on original findings.

Unlike review articles which synthesise existing literature to provide an overview, research articles present primary research with fresh data, exploring uncharted territories within a specific field.

The devil is in the details when it comes to these scholarly works. Original studies not only pose a research question but delve into methodologies that range from complex experimental designs to detailed observations.

Scholarly articles are often peer-reviewed, meaning that other experts in the field scrutinise the work before publication to ensure its validity and contribution to the field.

The empirical nature of research articles means that the raw data and analysis methods are laid bare for replication—a fundamental tenet of scientific inquiry. These papers typically include:

- Introduction: Introduces the problem

- Methodology: T he means by which the study was conducted

- Results: F indings from the study

- Discussion: Connects the findings to the bigger picture, highlighting implications and potential for future research.

While some journals accept such articles readily, the journey of a paper from research question to published research is fraught with meticulous data collection and rigorous peer evaluation.

For the keen observer, it’s the systematic reviews and meta-analyses that truly offer a glimpse into the current state of understanding, weaving through the tapestry of existing knowledge to pinpoint gaps and suggest paths forward.

It’s this level of detail—often hidden in plain sight in methods and results—that serves as a rich vein of information for those looking to conduct systematic reviews or embark on a similar empirical journey.

Whether it’s a clinical case study or a large-scale trial, the research article is an essential treasure in the scholarly literature, serving as a building block for academic writing and future exploration.

What Is A Review Article?

A review article stands out in the scholarly world as a synthesis of existing research, providing a critical and comprehensive analysis of a particular topic.

Unlike original research articles that report new empirical findings, review articles serve as a bridge connecting a myriad of studies, offering an overview that discerns patterns, strengths, and gaps within published work.

Peer-reviewed and systematically organised, these articles are essential for scholars who wish to familiarise themselves with the current state of knowledge on a given subject without having to delve into each individual research paper.

Insiders know that the crafting of a review article is an art in itself. Authors meticulously collect and analyse data from various sources, often employing methods like meta-analysis or systematic review searches to compare and combine findings.

They don’t just summarise existing literature; they synthesise it, providing new insights or revealing unexplored areas that could benefit from future research. It’s a rigorous process, often involving the intricate task of:

- Comparing clinical trials,

- Conducting extensive literature reviews, or even

- Generating new frameworks for understanding complex academic concepts.

The value of a well-conducted review is immense. Journals publishing these articles often see them as keystones, providing a foundation upon which other researchers can build.

Such reviews can point to the need for new primary research, challenge existing paradigms, or even sometimes shift the direction of scholarly inquiry.

For the discerning academic, a review article is not just a summary—it’s a roadmap for what comes next in the quest for knowledge.

How Are Review And Research Articles Different?

In the scholarly cosmos, the distinction between a research article and a review article is fundamental, yet it’s a source of perplexity for budding academics. Diving into the anatomy of these articles reveals their distinct roles in academia.

Original Research vs Synthesised Knowledge

A research article is an original study, presenting novel findings. It follows a stringent structure: an abstract to summarize the study, an introduction to set the stage, followed by methods, results, and a discussion that connects the findings to broader implications.

A review article instead synthesises the information from one or many of these original studies, into an article to allow easier reading. Some also offer additional insights for the readers.

Anatomy & Structure

An original research article is usually brimming with original data, charts, and perhaps phrases like “we investigated” or “the study found,” signifying fresh empirical insights. At the most basic, a research article usually contains sections such as:

- Introduction

- Methodology

- Future research ideas

A review article usually begins with an abstract summarising the scope and findings of the review. The main body is divided into sections that often include:

- An introduction to the topic

- A discussion segment that synthesises and analyses the compiled research

- Subtopics that further categorise the research by themes or methodologies.

Finally, it concludes with a summary or conclusion that reflects on the current state of research, identifies gaps, and may suggest directions for future studies, accompanied by a thorough list of references.

A research article is written to share new findings and original data on a particular research. This means the information are fresh, and new to the scientific community.

An example title of a research article may be “Investigating Necrotic Enteritis in 15 Californian Broiler Chicken Farms.”

A review article is more akin to an academic digest, offering a synthesis of existing research on a topic. It typically lacks the methodology and results sections found in research papers.

The main goal is to give a panoramic view of the existing literature, gaps, and sometimes, a meta-analysis combining findings from various studies to distill a more substantial conclusion.

An example of a review article about Necrotic Enteritis may be something like this: “Necrotic Enteritis in Broiler Chickens – What We Know So Far.”

Impact and Use in Academia

Research articles are the primary sources, documenting original work from scientists, as they conduct researches in their fields.

Original research articles are crucial in academia as they contribute new knowledge, support evidence-based advancements, and form the foundation for subsequent scholarly inquiry.

Research articles:

- Provide detailed methodology and results for peer scrutiny

- Foster academic dialogue,

- Often the preferred source for cutting-edge information in a given field, and

- Directly impacting teaching, policy-making, and further research.

Review articles are summaries that distill wisdom from multiple sources to shed light on the current state of knowledge, often guiding future research.

They are usually seen as secondary sources, containing insights that research articles might not individually convey.

Journals prize them for their ability to provide a systematic overview, and while they may not require the substantial funding necessary for conducting original research, their scholarly impact is substantial.

Wrapping Up

In the academic landscape, research articles and review articles form the backbone of knowledge dissemination and scholarly progress.

Research articles introduce novel insights, pushing the boundaries of understanding, while review articles offer a synthesis of existing findings, guiding future studies.

Both are essential: one for its fresh empirical contributions, the other for its comprehensive overviews and analytical prowess.

Together, they underpin the scientific method, spur academic debate, and serve as the keystones of educational advancement and informed decision-making in the quest for enlightenment and innovation.

Dr Andrew Stapleton has a Masters and PhD in Chemistry from the UK and Australia. He has many years of research experience and has worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow and Associate at a number of Universities. Although having secured funding for his own research, he left academia to help others with his YouTube channel all about the inner workings of academia and how to make it work for you.

Thank you for visiting Academia Insider.

We are here to help you navigate Academia as painlessly as possible. We are supported by our readers and by visiting you are helping us earn a small amount through ads and affiliate revenue - Thank you!

2024 © Academia Insider

Biological Sciences

- Research vs. Review Articles

- Find Books & eBooks

- Reference/Web Resources

- RefWorks This link opens in a new window

Defining Article Types

Research articles.

"A research article reports the results of original research, assesses its contribution to the body of knowledge in a given area, and is published in a peer-reviewed scholarly journal." - Pen & the Pad

The study design of research articles may vary, but in all cases some form of raw data have been collected and analyzed by the author(s).

- Example of a research article Development of a nanoparticle-assisted PCR assay for detection of bovine respiratory syncytial virus

Review Articles

"A review article, also called a literature review, is a survey of previously published research on a topic. It should give an overview of current thinking on the theme and, unlike an original research article, won’t present new experimental results." - Taylor & Francis Author Services

Review articles provide a comprehensive foundation on a topic, and, as such, they are particularly useful for helping student researchers get an overview of the existing literature on a topic.

- Example of a review article Mannheimia haemolytica growth and leukotoxin production for vaccine manufacturing — A bioprocess review

Differences between Research and Review Articles

Anatomy of a research article, title & abstract.

The title of an article is a brief descriptive overview of what was the focus of the study. The abstract is a mini-summary of the study.

Introduction

This section often included an overview of the existing literature on the topic and an explanation of why the author(s) conducted the study. It frequently contains references to previous work on the topic.

In this section, the authors explain what they did. For example, they may include how they collected or analyzed data. Descriptions of statistical analysis are also included in this section.

This is where the authors describe the outcomes of their analysis. They don't include interpretation in their area, but instead just use a straightforward explanation of the data. This is the section that usually makes use of charts and graphs.

Authors use the discussion section to explain how they interpret their results and situate them in relationship to existing and future research.

References/Works Cited

This is a list of sources the authors drew upon to plan their study, understand their topic, and/or support their discussion.

- << Previous: Find Articles

- Next: Find Books & eBooks >>

- Last Updated: Jan 31, 2024 11:56 AM

- URL: https://clemson.libguides.com/biology

How to Write a Review Article

- Types of Review Articles

- Before Writing a Review Article

- Determining Where to Publish

- Searching the Literature

- Citation Management

- Reading a Review Article

What is a Review Article?

The purpose of writing a review article is for knowledge updating concerning a topic.

A review article aims to highlight:

- What has been done?

- What has been found?

- What issues have not been addressed?

- What issues remain to be debated?

- What new issues have been raised?

- What will be the future direction of research?

Similarities and Differences to Original Research Articles

Differences Between Original Research Articles and Review Articles

- An original research article aims to: Provides background information (Intro.) on prior research, Reasons for present study, Issues to be investigated by the present study, Written for experts. Authors describe: Research methods & materials, Data acquisition/analysis tools, Results, Discussion of results.

- Both are Peer-reviewed for: Accuracy, Quality, Biases, Conflict of interest.

- A review article aims to: Extensive survey of published research articles about a specific topic, Critical appraising of research findings, summarize up-to-date research findings, Identify critical issues to be addressed, Written for experts and general audiences, Be a source of original research.

Figure by Zhiyong Han, PhD

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Types of Review Articles >>

- The Interprofessional Health Sciences Library

- 123 Metro Boulevard

- Nutley, NJ 07110

- [email protected]

- Visiting Campus

- News and Events

- Parents and Families

- Web Accessibility

- Career Center

- Public Safety

- Accountability

- Privacy Statements

- Report a Problem

- Login to LibApps

Maxwell Library | Bridgewater State University

Today's Hours:

- Maxwell Library

- Scholarly Journals and Popular Magazines

- Differences in Research, Review, and Opinion Articles

Scholarly Journals and Popular Magazines: Differences in Research, Review, and Opinion Articles

- Where Do I Start?

- How Do I Find Peer-Reviewed Articles?

- How Do I Compare Periodical Types?

- Where Can I find More Information?

Research Articles, Reviews, and Opinion Pieces

Scholarly or research articles are written for experts in their fields. They are often peer-reviewed or reviewed by other experts in the field prior to publication. They often have terminology or jargon that is field specific. They are generally lengthy articles. Social science and science scholarly articles have similar structures as do arts and humanities scholarly articles. Not all items in a scholarly journal are peer reviewed. For example, an editorial opinion items can be published in a scholarly journal but the article itself is not scholarly. Scholarly journals may include book reviews or other content that have not been peer reviewed.

Empirical Study: (Original or Primary) based on observation, experimentation, or study. Clinical trials, clinical case studies, and most meta-analyses are empirical studies.

Review Article: (Secondary Sources) Article that summarizes the research in a particular subject, area, or topic. They often include a summary, an literature reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.

Clinical case study (Primary or Original sources): These articles provide real cases from medical or clinical practice. They often include symptoms and diagnosis.

Clinical trials ( Health Research): Th ese articles are often based on large groups of people. They often include methods and control studies. They tend to be lengthy articles.

Opinion Piece: An opinion piece often includes personal thoughts, beliefs, or feelings or a judgement or conclusion based on facts. The goal may be to persuade or influence the reader that their position on this topic is the best.

Book review: Recent review of books in the field. They may be several pages but tend to be fairly short.

Social Science and Science Research Articles

The majority of social science and physical science articles include

- Journal Title and Author

- Abstract

- Introduction with a hypothesis or thesis

- Literature Review

- Methods/Methodology

- Results/Findings

Arts and Humanities Research Articles

In the Arts and Humanities, scholarly articles tend to be less formatted than in the social sciences and sciences. In the humanities, scholars are not conducting the same kinds of research experiments, but they are still using evidence to draw logical conclusions. Common sections of these articles include:

- an Introduction

- Discussion/Conclusion

- works cited/References/Bibliography

Research versus Review Articles

- 6 Article types that journals publish: A guide for early career researchers

- INFOGRAPHIC: 5 Differences between a research paper and a review paper

- Michigan State University. Empirical vs Review Articles

- UC Merced Library. Empirical & Review Articles

- << Previous: Where Do I Start?

- Next: How Do I Find Peer-Reviewed Articles? >>

- Last Updated: Jan 24, 2024 10:48 AM

- URL: https://library.bridgew.edu/scholarly

Phone: 508.531.1392 Text: 508.425.4096 Email: [email protected]

Feedback/Comments

Privacy Policy

Website Accessibility

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

PSYC 200 Lab in Experimental Methods (Atlanta)

- Find Research Articles

Empirical vs. Review Articles

How to recognize empirical journal articles, scholarly vs. non-scholarly sources.

- Cite Sources

- Find Tests & Measures

- Find Research Methods Materials

- Post-Library Lab Activity on Finding Tests and Measures

- Find Books, E-books, and Films

Psychology Librarian

Know the difference between empirical and review articles.

Empirical article An empirical (research) article reports methods and findings of an original research study conducted by the authors of the article.

Literature Review article A review article or "literature review" discusses past research studies on a given topic.

Definition of an empirical study: An empirical research article reports the results of a study that uses data derived from actual observation or experimentation. Empirical research articles are examples of primary research.

Parts of a standard empirical research article: (articles will not necessary use the exact terms listed below.)

- Abstract ... A paragraph length description of what the study includes.

- Introduction ...Includes a statement of the hypotheses for the research and a review of other research on the topic.

- Who are participants

- Design of the study

- What the participants did

- What measures were used

- Results ...Describes the outcomes of the measures of the study.

- Discussion ...Contains the interpretations and implications of the study.

- References ...Contains citation information on the material cited in the report. (also called bibliography or works cited)

Characteristics of an Empirical Article:

- Empirical articles will include charts, graphs, or statistical analysis.

- Empirical research articles are usually substantial, maybe from 8-30 pages long.

- There is always a bibliography found at the end of the article.

Type of publications that publish empirical studies:

- Empirical research articles are published in scholarly or academic journals

- These journals are also called “peer-reviewed,” or “refereed” publications.

Examples of such publications include:

- Computers in Human Behavior

- Journal of Educational Psychology

Examples of databases that contain empirical research: (selected list only)

- Web of Science

This page is adapted from the Sociology Research Guide: Identify Empirical Articles page at Cal State Fullerton Pollak Library.

Know the difference between scholarly and non-scholarly articles.

"Scholarly" journal = "Peer-Reviewed" journal = "Refereed" journal

When researching your topic, you may come across many different types of sources and articles. When evaluating these sources, it is important to think about:

- Who is the author?

- Who is the audience or why was this written?

- Where was this published?

- Is this relevant to your research?

- When was this written? Has it been updated?

- Are there any citations? Who do they cite?

Helpful Links and Guides

Here are helpful links and guides to check out for more information on scholarly sources:

- This database contains data on different types of serials and can be used to determine whether a periodical is peer-reviewed or not: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory

- The UC Berkeley Library published this useful guide on evaluating resources, including the differences between scholarly and popular sources, as well as how to find primary sources: UC Berkeley's Evaluating Resources LibGuide

- << Previous: Quick Poll

- Next: Cite Sources >>

- Last Updated: Feb 14, 2024 3:32 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.emory.edu/main/psyc200

Science Research: Primary Sources and Original Research vs. Review Articles

- Additional Web Resources

- Health & Science Databases

- Primary Sources and Original Research vs. Review Articles

- Citation Guides, Generators, and Tools

Original Research vs. Review Articles. How can I tell the Difference?

Research vs review articles.

It's often difficult to tell the difference between original research articles and review articles. Here are some explanations and tips that may help: "Review articles are often as lengthy or even longer that original research articles. What the authors of review articles are doing in analysing and evaluating current research and investigations related to a specific topic, field, or problem. They are not primary sources since they review previously published material. They can be of great value for identifying potentially good primary sources, but they aren't primary themselves. Primary research articles can be identified by a commonly used format. If an article contains the following elements, you can count on it being a primary research article. Look for sections titled:

Methods (sometimes with variations, such as Materials and Methods) Results (usually followed with charts and statistical tables) Discussion

You can also read the abstract to get a good sense of the kind of article that is being presented.

If it is a review article instead of a research article, the abstract should make that pretty clear. If there is no abstract at all, that in itself may be a sign that it is not a primary resource. Short research articles, such as those found in Science and similar scientific publications that mix news, editorials, and forums with research reports, however, may not include any of those elements. In those cases look at the words the authors use, phrases such as "we tested" and "in our study, we measured" will tell you that the article is reporting on original research."*

*Taken from Ithca College Libraries

Primary and Secondary Sources for Science

In the Sciences, primary sources are documents that provide full description of the original research. For example, a primary source would be a journal article where scientists describe their research on the human immune system. A secondary source would be an article commenting or analyzing the scientists' research on the human immune system.

EXAMPLES OF PRIMARY AND SECONDARY SOURCES

Source: The Evolution of Scientific Information (from Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science , vol. 26).

Primary Vs. Secondary Vs. Tertiary Sources

- << Previous: Books

- Next: Citation Guides, Generators, and Tools >>

- Last Updated: Nov 16, 2023 1:58 PM

- URL: https://andersonuniversity.libguides.com/ScienceResearch

Thrift Library | (864) 231-2050 | [email protected] | Anderson University 316 Boulevard Anderson, SC 29621

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Turk J Urol

- v.39(Suppl 1); 2013 Sep

How to write a review article?

In the medical sciences, the importance of review articles is rising. When clinicians want to update their knowledge and generate guidelines about a topic, they frequently use reviews as a starting point. The value of a review is associated with what has been done, what has been found and how these findings are presented. Before asking ‘how,’ the question of ‘why’ is more important when starting to write a review. The main and fundamental purpose of writing a review is to create a readable synthesis of the best resources available in the literature for an important research question or a current area of research. Although the idea of writing a review is attractive, it is important to spend time identifying the important questions. Good review methods are critical because they provide an unbiased point of view for the reader regarding the current literature. There is a consensus that a review should be written in a systematic fashion, a notion that is usually followed. In a systematic review with a focused question, the research methods must be clearly described. A ‘methodological filter’ is the best method for identifying the best working style for a research question, and this method reduces the workload when surveying the literature. An essential part of the review process is differentiating good research from bad and leaning on the results of the better studies. The ideal way to synthesize studies is to perform a meta-analysis. In conclusion, when writing a review, it is best to clearly focus on fixed ideas, to use a procedural and critical approach to the literature and to express your findings in an attractive way.

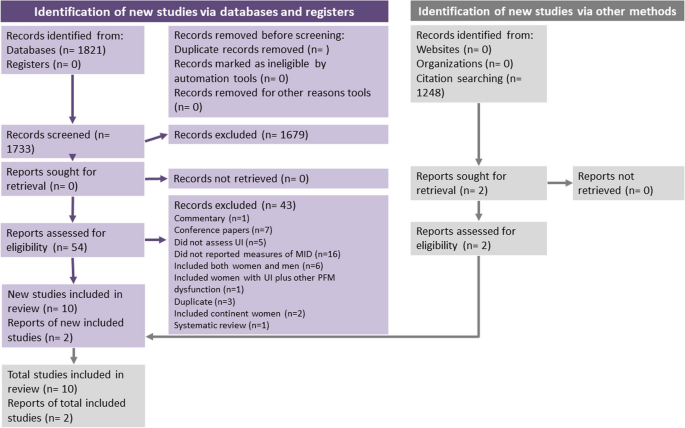

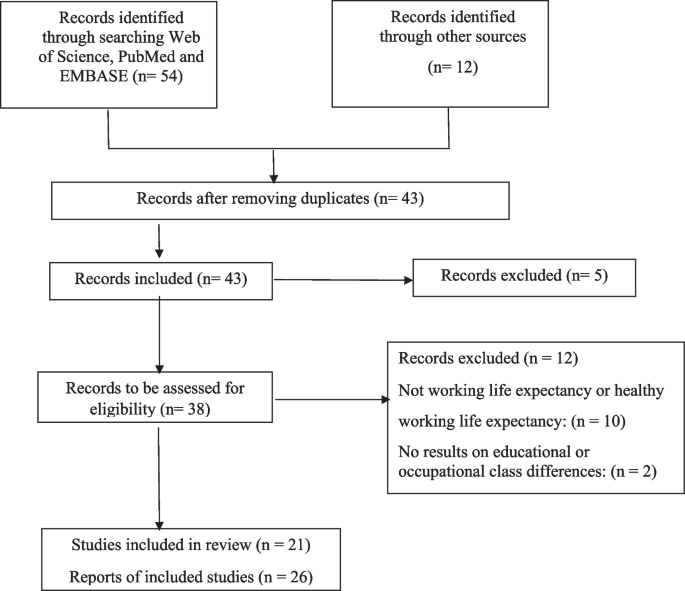

The importance of review articles in health sciences is increasing day by day. Clinicians frequently benefit from review articles to update their knowledge in their field of specialization, and use these articles as a starting point for formulating guidelines. [ 1 , 2 ] The institutions which provide financial support for further investigations resort to these reviews to reveal the need for these researches. [ 3 ] As is the case with all other researches, the value of a review article is related to what is achieved, what is found, and the way of communicating this information. A few studies have evaluated the quality of review articles. Murlow evaluated 50 review articles published in 1985, and 1986, and revealed that none of them had complied with clear-cut scientific criteria. [ 4 ] In 1996 an international group that analyzed articles, demonstrated the aspects of review articles, and meta-analyses that had not complied with scientific criteria, and elaborated QUOROM (QUality Of Reporting Of Meta-analyses) statement which focused on meta-analyses of randomized controlled studies. [ 5 ] Later on this guideline was updated, and named as PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). [ 6 ]

Review articles are divided into 2 categories as narrative, and systematic reviews. Narrative reviews are written in an easily readable format, and allow consideration of the subject matter within a large spectrum. However in a systematic review, a very detailed, and comprehensive literature surveying is performed on the selected topic. [ 7 , 8 ] Since it is a result of a more detailed literature surveying with relatively lesser involvement of author’s bias, systematic reviews are considered as gold standard articles. Systematic reviews can be diivded into qualitative, and quantitative reviews. In both of them detailed literature surveying is performed. However in quantitative reviews, study data are collected, and statistically evaluated (ie. meta-analysis). [ 8 ]

Before inquring for the method of preparation of a review article, it is more logical to investigate the motivation behind writing the review article in question. The fundamental rationale of writing a review article is to make a readable synthesis of the best literature sources on an important research inquiry or a topic. This simple definition of a review article contains the following key elements:

- The question(s) to be dealt with

- Methods used to find out, and select the best quality researches so as to respond to these questions.

- To synthetize available, but quite different researches

For the specification of important questions to be answered, number of literature references to be consulted should be more or less determined. Discussions should be conducted with colleagues in the same area of interest, and time should be reserved for the solution of the problem(s). Though starting to write the review article promptly seems to be very alluring, the time you spend for the determination of important issues won’t be a waste of time. [ 9 ]

The PRISMA statement [ 6 ] elaborated to write a well-designed review articles contains a 27-item checklist ( Table 1 ). It will be reasonable to fulfill the requirements of these items during preparation of a review article or a meta-analysis. Thus preparation of a comprehensible article with a high-quality scientific content can be feasible.

PRISMA statement: A 27-item checklist

Contents and format

Important differences exist between systematic, and non-systematic reviews which especially arise from methodologies used in the description of the literature sources. A non-systematic review means use of articles collected for years with the recommendations of your colleagues, while systematic review is based on struggles to search for, and find the best possible researches which will respond to the questions predetermined at the start of the review.

Though a consensus has been reached about the systematic design of the review articles, studies revealed that most of them had not been written in a systematic format. McAlister et al. analyzed review articles in 6 medical journals, and disclosed that in less than one fourth of the review articles, methods of description, evaluation or synthesis of evidence had been provided, one third of them had focused on a clinical topic, and only half of them had provided quantitative data about the extend of the potential benefits. [ 10 ]

Use of proper methodologies in review articles is important in that readers assume an objective attitude towards updated information. We can confront two problems while we are using data from researches in order to answer certain questions. Firstly, we can be prejudiced during selection of research articles or these articles might be biased. To minimize this risk, methodologies used in our reviews should allow us to define, and use researches with minimal degree of bias. The second problem is that, most of the researches have been performed with small sample sizes. In statistical methods in meta-analyses, available researches are combined to increase the statistical power of the study. The problematic aspect of a non-systematic review is that our tendency to give biased responses to the questions, in other words we apt to select the studies with known or favourite results, rather than the best quality investigations among them.

As is the case with many research articles, general format of a systematic review on a single subject includes sections of Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion ( Table 2 ).

Structure of a systematic review

Preparation of the review article

Steps, and targets of constructing a good review article are listed in Table 3 . To write a good review article the items in Table 3 should be implemented step by step. [ 11 – 13 ]

Steps of a systematic review

The research question

It might be helpful to divide the research question into components. The most prevalently used format for questions related to the treatment is PICO (P - Patient, Problem or Population; I-Intervention; C-appropriate Comparisons, and O-Outcome measures) procedure. For example In female patients (P) with stress urinary incontinence, comparisons (C) between transobturator, and retropubic midurethral tension-free band surgery (I) as for patients’ satisfaction (O).

Finding Studies

In a systematic review on a focused question, methods of investigation used should be clearly specified.

Ideally, research methods, investigated databases, and key words should be described in the final report. Different databases are used dependent on the topic analyzed. In most of the clinical topics, Medline should be surveyed. However searching through Embase and CINAHL can be also appropriate.

While determining appropriate terms for surveying, PICO elements of the issue to be sought may guide the process. Since in general we are interested in more than one outcome, P, and I can be key elements. In this case we should think about synonyms of P, and I elements, and combine them with a conjunction AND.

One method which might alleviate the workload of surveying process is “methodological filter” which aims to find the best investigation method for each research question. A good example of this method can be found in PubMed interface of Medline. The Clinical Queries tool offers empirically developed filters for five different inquiries as guidelines for etiology, diagnosis, treatment, prognosis or clinical prediction.

Evaluation of the Quality of the Study

As an indispensable component of the review process is to discriminate good, and bad quality researches from each other, and the outcomes should be based on better qualified researches, as far as possible. To achieve this goal you should know the best possible evidence for each type of question The first component of the quality is its general planning/design of the study. General planning/design of a cohort study, a case series or normal study demonstrates variations.

A hierarchy of evidence for different research questions is presented in Table 4 . However this hierarchy is only a first step. After you find good quality research articles, you won’t need to read all the rest of other articles which saves you tons of time. [ 14 ]

Determination of levels of evidence based on the type of the research question

Formulating a Synthesis

Rarely all researches arrive at the same conclusion. In this case a solution should be found. However it is risky to make a decision based on the votes of absolute majority. Indeed, a well-performed large scale study, and a weakly designed one are weighed on the same scale. Therefore, ideally a meta-analysis should be performed to solve apparent differences. Ideally, first of all, one should be focused on the largest, and higher quality study, then other studies should be compared with this basic study.

Conclusions

In conclusion, during writing process of a review article, the procedures to be achieved can be indicated as follows: 1) Get rid of fixed ideas, and obsessions from your head, and view the subject from a large perspective. 2) Research articles in the literature should be approached with a methodological, and critical attitude and 3) finally data should be explained in an attractive way.

Review articles: purpose, process, and structure

- Published: 02 October 2017

- Volume 46 , pages 1–5, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Robert W. Palmatier 1 ,

- Mark B. Houston 2 &

- John Hulland 3

226k Accesses

424 Citations

63 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Many research disciplines feature high-impact journals that are dedicated outlets for review papers (or review–conceptual combinations) (e.g., Academy of Management Review , Psychology Bulletin , Medicinal Research Reviews ). The rationale for such outlets is the premise that research integration and synthesis provides an important, and possibly even a required, step in the scientific process. Review papers tend to include both quantitative (i.e., meta-analytic, systematic reviews) and narrative or more qualitative components; together, they provide platforms for new conceptual frameworks, reveal inconsistencies in the extant body of research, synthesize diverse results, and generally give other scholars a “state-of-the-art” snapshot of a domain, often written by topic experts (Bem 1995 ). Many premier marketing journals publish meta-analytic review papers too, though authors often must overcome reviewers’ concerns that their contributions are limited due to the absence of “new data.” Furthermore, relatively few non-meta-analysis review papers appear in marketing journals, probably due to researchers’ perceptions that such papers have limited publication opportunities or their beliefs that the field lacks a research tradition or “respect” for such papers. In many cases, an editor must provide strong support to help such review papers navigate the review process. Yet, once published, such papers tend to be widely cited, suggesting that members of the field find them useful (see Bettencourt and Houston 2001 ).

In this editorial, we seek to address three topics relevant to review papers. First, we outline a case for their importance to the scientific process, by describing the purpose of review papers . Second, we detail the review paper editorial initiative conducted over the past two years by the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science ( JAMS ), focused on increasing the prevalence of review papers. Third, we describe a process and structure for systematic ( i.e. , non-meta-analytic) review papers , referring to Grewal et al. ( 2018 ) insights into parallel meta-analytic (effects estimation) review papers. (For some strong recent examples of marketing-related meta-analyses, see Knoll and Matthes 2017 ; Verma et al. 2016 ).

Purpose of review papers

In their most general form, review papers “are critical evaluations of material that has already been published,” some that include quantitative effects estimation (i.e., meta-analyses) and some that do not (i.e., systematic reviews) (Bem 1995 , p. 172). They carefully identify and synthesize relevant literature to evaluate a specific research question, substantive domain, theoretical approach, or methodology and thereby provide readers with a state-of-the-art understanding of the research topic. Many of these benefits are highlighted in Hanssens’ ( 2018 ) paper titled “The Value of Empirical Generalizations in Marketing,” published in this same issue of JAMS.

The purpose of and contributions associated with review papers can vary depending on their specific type and research question, but in general, they aim to

Resolve definitional ambiguities and outline the scope of the topic.

Provide an integrated, synthesized overview of the current state of knowledge.

Identify inconsistencies in prior results and potential explanations (e.g., moderators, mediators, measures, approaches).

Evaluate existing methodological approaches and unique insights.

Develop conceptual frameworks to reconcile and extend past research.

Describe research insights, existing gaps, and future research directions.

Not every review paper can offer all of these benefits, but this list represents their key contributions. To provide a sufficient contribution, a review paper needs to achieve three key standards. First, the research domain needs to be well suited for a review paper, such that a sufficient body of past research exists to make the integration and synthesis valuable—especially if extant research reveals theoretical inconsistences or heterogeneity in its effects. Second, the review paper must be well executed, with an appropriate literature collection and analysis techniques, sufficient breadth and depth of literature coverage, and a compelling writing style. Third, the manuscript must offer significant new insights based on its systematic comparison of multiple studies, rather than simply a “book report” that describes past research. This third, most critical standard is often the most difficult, especially for authors who have not “lived” with the research domain for many years, because achieving it requires drawing some non-obvious connections and insights from multiple studies and their many different aspects (e.g., context, method, measures). Typically, after the “review” portion of the paper has been completed, the authors must spend many more months identifying the connections to uncover incremental insights, each of which takes time to detail and explicate.

The increasing methodological rigor and technical sophistication of many marketing studies also means that they often focus on smaller problems with fewer constructs. By synthesizing these piecemeal findings, reconciling conflicting evidence, and drawing a “big picture,” meta-analyses and systematic review papers become indispensable to our comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon, among both academic and practitioner communities. Thus, good review papers provide a solid platform for future research, in the reviewed domain but also in other areas, in that researchers can use a good review paper to learn about and extend key insights to new areas.

This domain extension, outside of the core area being reviewed, is one of the key benefits of review papers that often gets overlooked. Yet it also is becoming ever more important with the expanding breadth of marketing (e.g., econometric modeling, finance, strategic management, applied psychology, sociology) and the increasing velocity in the accumulation of marketing knowledge (e.g., digital marketing, social media, big data). Against this backdrop, systematic review papers and meta-analyses help academics and interested managers keep track of research findings that fall outside their main area of specialization.

JAMS’ review paper editorial initiative

With a strong belief in the importance of review papers, the editorial team of JAMS has purposely sought out leading scholars to provide substantive review papers, both meta-analysis and systematic, for publication in JAMS . Many of the scholars approached have voiced concerns about the risk of such endeavors, due to the lack of alternative outlets for these types of papers. Therefore, we have instituted a unique process, in which the authors develop a detailed outline of their paper, key tables and figures, and a description of their literature review process. On the basis of this outline, we grant assurances that the contribution hurdle will not be an issue for publication in JAMS , as long as the authors execute the proposed outline as written. Each paper still goes through the normal review process and must meet all publication quality standards, of course. In many cases, an Area Editor takes an active role to help ensure that each paper provides sufficient insights, as required for a high-quality review paper. This process gives the author team confidence to invest effort in the process. An analysis of the marketing journals in the Financial Times (FT 50) journal list for the past five years (2012–2016) shows that JAMS has become the most common outlet for these papers, publishing 31% of all review papers that appeared in the top six marketing journals.

As a next step in positioning JAMS as a receptive marketing outlet for review papers, we are conducting a Thought Leaders Conference on Generalizations in Marketing: Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses , with a corresponding special issue (see www.springer.com/jams ). We will continue our process of seeking out review papers as an editorial strategy in areas that could be advanced by the integration and synthesis of extant research. We expect that, ultimately, such efforts will become unnecessary, as authors initiate review papers on topics of their own choosing to submit them to JAMS . In the past two years, JAMS already has increased the number of papers it publishes annually, from just over 40 to around 60 papers per year; this growth has provided “space” for 8–10 review papers per year, reflecting our editorial target.

Consistent with JAMS ’ overall focus on managerially relevant and strategy-focused topics, all review papers should reflect this emphasis. For example, the domains, theories, and methods reviewed need to have some application to past or emerging managerial research. A good rule of thumb is that the substantive domain, theory, or method should attract the attention of readers of JAMS .

The efforts of multiple editors and Area Editors in turn have generated a body of review papers that can serve as useful examples of the different types and approaches that JAMS has published.

Domain-based review papers

Domain-based review papers review, synthetize, and extend a body of literature in the same substantive domain. For example, in “The Role of Privacy in Marketing” (Martin and Murphy 2017 ), the authors identify and define various privacy-related constructs that have appeared in recent literature. Then they examine the different theoretical perspectives brought to bear on privacy topics related to consumers and organizations, including ethical and legal perspectives. These foundations lead in to their systematic review of privacy-related articles over a clearly defined date range, from which they extract key insights from each study. This exercise of synthesizing diverse perspectives allows these authors to describe state-of-the-art knowledge regarding privacy in marketing and identify useful paths for research. Similarly, a new paper by Cleeren et al. ( 2017 ), “Marketing Research on Product-Harm Crises: A Review, Managerial Implications, and an Agenda for Future Research,” provides a rich systematic review, synthesizes extant research, and points the way forward for scholars who are interested in issues related to defective or dangerous market offerings.

Theory-based review papers

Theory-based review papers review, synthetize, and extend a body of literature that uses the same underlying theory. For example, Rindfleisch and Heide’s ( 1997 ) classic review of research in marketing using transaction cost economics has been cited more than 2200 times, with a significant impact on applications of the theory to the discipline in the past 20 years. A recent paper in JAMS with similar intent, which could serve as a helpful model, focuses on “Resource-Based Theory in Marketing” (Kozlenkova et al. 2014 ). The article dives deeply into a description of the theory and its underlying assumptions, then organizes a systematic review of relevant literature according to various perspectives through which the theory has been applied in marketing. The authors conclude by identifying topical domains in marketing that might benefit from additional applications of the theory (e.g., marketing exchange), as well as related theories that could be integrated meaningfully with insights from the resource-based theory.

Method-based review papers

Method-based review papers review, synthetize, and extend a body of literature that uses the same underlying method. For example, in “Event Study Methodology in the Marketing Literature: An Overview” (Sorescu et al. 2017 ), the authors identify published studies in marketing that use an event study methodology. After a brief review of the theoretical foundations of event studies, they describe in detail the key design considerations associated with this method. The article then provides a roadmap for conducting event studies and compares this approach with a stock market returns analysis. The authors finish with a summary of the strengths and weaknesses of the event study method, which in turn suggests three main areas for further research. Similarly, “Discriminant Validity Testing in Marketing: An Analysis, Causes for Concern, and Proposed Remedies” (Voorhies et al. 2016 ) systematically reviews existing approaches for assessing discriminant validity in marketing contexts, then uses Monte Carlo simulation to determine which tests are most effective.

Our long-term editorial strategy is to make sure JAMS becomes and remains a well-recognized outlet for both meta-analysis and systematic managerial review papers in marketing. Ideally, review papers would come to represent 10%–20% of the papers published by the journal.

Process and structure for review papers

In this section, we review the process and typical structure of a systematic review paper, which lacks any long or established tradition in marketing research. The article by Grewal et al. ( 2018 ) provides a summary of effects-focused review papers (i.e., meta-analyses), so we do not discuss them in detail here.

Systematic literature review process

Some review papers submitted to journals take a “narrative” approach. They discuss current knowledge about a research domain, yet they often are flawed, in that they lack criteria for article inclusion (or, more accurately, article exclusion), fail to discuss the methodology used to evaluate included articles, and avoid critical assessment of the field (Barczak 2017 ). Such reviews tend to be purely descriptive, with little lasting impact.

In contrast, a systematic literature review aims to “comprehensively locate and synthesize research that bears on a particular question, using organized, transparent, and replicable procedures at each step in the process” (Littell et al. 2008 , p. 1). Littell et al. describe six key steps in the systematic review process. The extent to which each step is emphasized varies by paper, but all are important components of the review.

Topic formulation . The author sets out clear objectives for the review and articulates the specific research questions or hypotheses that will be investigated.

Study design . The author specifies relevant problems, populations, constructs, and settings of interest. The aim is to define explicit criteria that can be used to assess whether any particular study should be included in or excluded from the review. Furthermore, it is important to develop a protocol in advance that describes the procedures and methods to be used to evaluate published work.

Sampling . The aim in this third step is to identify all potentially relevant studies, including both published and unpublished research. To this end, the author must first define the sampling unit to be used in the review (e.g., individual, strategic business unit) and then develop an appropriate sampling plan.

Data collection . By retrieving the potentially relevant studies identified in the third step, the author can determine whether each study meets the eligibility requirements set out in the second step. For studies deemed acceptable, the data are extracted from each study and entered into standardized templates. These templates should be based on the protocols established in step 2.

Data analysis . The degree and nature of the analyses used to describe and examine the collected data vary widely by review. Purely descriptive analysis is useful as a starting point but rarely is sufficient on its own. The examination of trends, clusters of ideas, and multivariate relationships among constructs helps flesh out a deeper understanding of the domain. For example, both Hult ( 2015 ) and Huber et al. ( 2014 ) use bibliometric approaches (e.g., examine citation data using multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis techniques) to identify emerging versus declining themes in the broad field of marketing.

Reporting . Three key aspects of this final step are common across systematic reviews. First, the results from the fifth step need to be presented, clearly and compellingly, using narratives, tables, and figures. Second, core results that emerge from the review must be interpreted and discussed by the author. These revelatory insights should reflect a deeper understanding of the topic being investigated, not simply a regurgitation of well-established knowledge. Third, the author needs to describe the implications of these unique insights for both future research and managerial practice.

A new paper by Watson et al. ( 2017 ), “Harnessing Difference: A Capability-Based Framework for Stakeholder Engagement in Environmental Innovation,” provides a good example of a systematic review, starting with a cohesive conceptual framework that helps establish the boundaries of the review while also identifying core constructs and their relationships. The article then explicitly describes the procedures used to search for potentially relevant papers and clearly sets out criteria for study inclusion or exclusion. Next, a detailed discussion of core elements in the framework weaves published research findings into the exposition. The paper ends with a presentation of key implications and suggestions for the next steps. Similarly, “Marketing Survey Research Best Practices: Evidence and Recommendations from a Review of JAMS Articles” (Hulland et al. 2017 ) systematically reviews published marketing studies that use survey techniques, describes recent trends, and suggests best practices. In their review, Hulland et al. examine the entire population of survey papers published in JAMS over a ten-year span, relying on an extensive standardized data template to facilitate their subsequent data analysis.

Structure of systematic review papers

There is no cookie-cutter recipe for the exact structure of a useful systematic review paper; the final structure depends on the authors’ insights and intended points of emphasis. However, several key components are likely integral to a paper’s ability to contribute.

Depth and rigor

Systematic review papers must avoid falling in to two potential “ditches.” The first ditch threatens when the paper fails to demonstrate that a systematic approach was used for selecting articles for inclusion and capturing their insights. If a reader gets the impression that the author has cherry-picked only articles that fit some preset notion or failed to be thorough enough, without including articles that make significant contributions to the field, the paper will be consigned to the proverbial side of the road when it comes to the discipline’s attention.

Authors that fall into the other ditch present a thorough, complete overview that offers only a mind-numbing recitation, without evident organization, synthesis, or critical evaluation. Although comprehensive, such a paper is more of an index than a useful review. The reviewed articles must be grouped in a meaningful way to guide the reader toward a better understanding of the focal phenomenon and provide a foundation for insights about future research directions. Some scholars organize research by scholarly perspectives (e.g., the psychology of privacy, the economics of privacy; Martin and Murphy 2017 ); others classify the chosen articles by objective research aspects (e.g., empirical setting, research design, conceptual frameworks; Cleeren et al. 2017 ). The method of organization chosen must allow the author to capture the complexity of the underlying phenomenon (e.g., including temporal or evolutionary aspects, if relevant).

Replicability

Processes for the identification and inclusion of research articles should be described in sufficient detail, such that an interested reader could replicate the procedure. The procedures used to analyze chosen articles and extract their empirical findings and/or key takeaways should be described with similar specificity and detail.

We already have noted the potential usefulness of well-done review papers. Some scholars always are new to the field or domain in question, so review papers also need to help them gain foundational knowledge. Key constructs, definitions, assumptions, and theories should be laid out clearly (for which purpose summary tables are extremely helpful). An integrated conceptual model can be useful to organize cited works. Most scholars integrate the knowledge they gain from reading the review paper into their plans for future research, so it is also critical that review papers clearly lay out implications (and specific directions) for research. Ideally, readers will come away from a review article filled with enthusiasm about ways they might contribute to the ongoing development of the field.

Helpful format

Because such a large body of research is being synthesized in most review papers, simply reading through the list of included studies can be exhausting for readers. We cannot overstate the importance of tables and figures in review papers, used in conjunction with meaningful headings and subheadings. Vast literature review tables often are essential, but they must be organized in a way that makes their insights digestible to the reader; in some cases, a sequence of more focused tables may be better than a single, comprehensive table.

In summary, articles that review extant research in a domain (topic, theory, or method) can be incredibly useful to the scientific progress of our field. Whether integrating the insights from extant research through a meta-analysis or synthesizing them through a systematic assessment, the promised benefits are similar. Both formats provide readers with a useful overview of knowledge about the focal phenomenon, as well as insights on key dilemmas and conflicting findings that suggest future research directions. Thus, the editorial team at JAMS encourages scholars to continue to invest the time and effort to construct thoughtful review papers.

Barczak, G. (2017). From the editor: writing a review article. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 34 (2), 120–121.

Article Google Scholar

Bem, D. J. (1995). Writing a review article for psychological bulletin. Psychological Bulletin, 118 (2), 172–177.

Bettencourt, L. A., & Houston, M. B. (2001). Assessing the impact of article method type and subject area on citation frequency and reference diversity. Marketing Letters, 12 (4), 327–340.

Cleeren, K., Dekimpe, M. G., & van Heerde, H. J. (2017). Marketing research on product-harm crises: a review, managerial implications. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (5), 593–615.

Grewal, D., Puccinelli, N. M., & Monroe, K. B. (2018). Meta-analysis: error cancels and truth accrues. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1).

Hanssens, D. M. (2018). The value of empirical generalizations in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1).

Huber, J., Kamakura, W., & Mela, C. F. (2014). A topical history of JMR . Journal of Marketing Research, 51 (1), 84–91.

Hulland, J., Baumgartner, H., & Smith, K. M. (2017). Marketing survey research best practices: evidence and recommendations from a review of JAMS articles. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0532-y .

Hult, G. T. M. (2015). JAMS 2010—2015: literature themes and intellectual structure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43 (6), 663–669.

Knoll, J., & Matthes, J. (2017). The effectiveness of celebrity endorsements: a meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (1), 55–75.

Kozlenkova, I. V., Samaha, S. A., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). Resource-based theory in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42 (1), 1–21.

Littell, J. H., Corcoran, J., & Pillai, V. (2008). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis . New York: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Martin, K. D., & Murphy, P. E. (2017). The role of data privacy in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (2), 135–155.

Rindfleisch, A., & Heide, J. B. (1997). Transaction cost analysis: past, present, and future applications. Journal of Marketing, 61 (4), 30–54.

Sorescu, A., Warren, N. L., & Ertekin, L. (2017). Event study methodology in the marketing literature: an overview. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (2), 186–207.

Verma, V., Sharma, D., & Sheth, J. (2016). Does relationship marketing matter in online retailing? A meta-analytic approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44 (2), 206–217.

Voorhies, C. M., Brady, M. K., Calantone, R., & Ramirez, E. (2016). Discriminant validity testing in marketing: an analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44 (1), 119–134.

Watson, R., Wilson, H. N., Smart, P., & Macdonald, E. K. (2017). Harnessing difference: a capability-based framework for stakeholder engagement in environmental innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12394 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Foster School of Business, University of Washington, Box: 353226, Seattle, WA, 98195-3226, USA

Robert W. Palmatier

Neeley School of Business, Texas Christian University, Fort Worth, TX, USA

Mark B. Houston

Terry College of Business, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA

John Hulland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Robert W. Palmatier .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Palmatier, R.W., Houston, M.B. & Hulland, J. Review articles: purpose, process, and structure. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 46 , 1–5 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0563-4

Download citation

Published : 02 October 2017

Issue Date : January 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0563-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us