OPINION article

Factors affecting impulse buying behavior of consumers.

- Instituto Superior de Gestão, Lisbon, Portugal

In recent years, the study of consumer behavior has been marked by significant changes, mainly in decision-making process and consequently in the influences of purchase intention ( Stankevich, 2017 ).

The markets are different and characterized by an increased competition, as well a constant innovation in products and services available and a greater number of companies in the same market. In this scenario it is essential to know the consumer well ( Varadarajan, 2020 ). It is through the analysis of the factors that have a direct impact on consumer behavior that it is possible to innovate and meet their expectations. This research is essential for marketers to be able to improve their campaigns and reach the target audience more effectively ( Ding et al., 2020 ).

Consumer behavior refers to the activities directly involved in obtaining products /services, so it includes the decision-making processes that precede and succeed these actions. Thus, it appears that the advertising message can cause a certain psychological influence that motivates individuals to desire and, consequently, buy a certain product/service ( Wertenbroch et al., 2020 ).

Studies developed by Meena (2018) show that from a young age one begins to have a preference for one product/service over another, as we are confronted with various commercial stimuli that shape our choices. The sales promotion has become one of the most powerful tools to change the perception of buyers and has a significant impact on their purchase decision ( Khan et al., 2019 ). Advertising has a great capacity to influence and persuade, and even the most innocuous, can cause changes in behavior that affect the consumer's purchase intention. Falebita et al. (2020) consider this influence predominantly positive, as shown by about 84.0% of the total number of articles reviewed in the study developed by these authors.

Kumar et al. (2020) add that psychological factors have a strong implication in the purchase decision, as we easily find people who, after having purchased a product/ service, wonder about the reason why they did it. It is essential to understand the mental triggers behind the purchase decision process, which is why consumer psychology is related to marketing strategies ( Ding et al., 2020 ). It is not uncommon for the two areas to use the same models to explain consumer behavior and the reasons that trigger impulse purchases. Consumers are attracted by advertising and the messages it conveys, which is reflected in their behavior and purchase intentions ( Varadarajan, 2020 ).

Impulse buying has been studied from several perspectives, namely: (i) rational processes; (ii) emotional resources; (iii) the cognitive currents arising from the theory of social judgment; (iv) persuasive communication; (v) and the effects of advertising on consumer behavior ( Malter et al., 2020 ).

The causes of impulsive behavior are triggered by an irresistible force to buy and an inability to evaluate its consequences. Despite being aware of the negative effects of buying, there is an enormous desire to immediately satisfy your most pressing needs ( Meena, 2018 ).

The importance of impulse buying in consumer behavior has been studied since the 1940's, since it represents between 40.0 and 80.0% of all purchases. This type of purchase obeys non-rational reasons that are characterized by the sudden appearance and the (in) satisfaction between the act of buying and the results obtained ( Reisch and Zhao, 2017 ). Aragoncillo and Orús (2018) also refer that a considerable percentage of sales comes from purchases that are not planned and do not correspond to the intended products before entering the store.

According to Burton et al. (2018) , impulse purchases occur when there is a sudden and strong emotional desire, which arises from a reactive behavior that is characterized by low cognitive control. This tendency to buy spontaneously and without reflection can be explained by the immediate gratification it provides to the buyer ( Pradhan et al., 2018 ).

Impulsive shopping in addition to having an emotional content can be triggered by several factors, including: the store environment, life satisfaction, self-esteem, and the emotional state of the consumer at that time ( Gogoi and Shillong, 2020 ). We believe that impulse purchases can be stimulated by an unexpected need, by a visual stimulus, a promotional campaign and/or by the decrease of the cognitive capacity to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of that purchase.

The buying experience increasingly depends on the interaction between the person and the point of sale environment, but it is not just the atmosphere that stimulates the impulsive behavior of the consumer. The sensory and psychological factors associated with the type of products, the knowledge about them and brand loyalty, often end up overlapping the importance attributed to the physical environment ( Platania et al., 2016 ).

The impulse buying causes an emotional lack of control generated by the conflict between the immediate reward and the negative consequences that the purchase can originate, which can trigger compulsive behaviors that can become chronic and pathological ( Pandya and Pandya, 2020 ).

Sohn and Ko (2021) , argue that although all impulse purchases can be considered as unplanned, not all unplanned purchases can be considered impulsive. Unplanned purchases can occur, simply because the consumer needs to purchase a product, but for whatever reason has not been placed on the shopping list in advance. This suggests that unplanned purchases are not necessarily accompanied by the urgent desire that generally characterizes impulse purchases.

The impulse purchases arise from sensory experiences (e.g., store atmosphere, product layout), so purchases made in physical stores tend to be more impulsive than purchases made online. This type of shopping results from the stimulation of the five senses and the internet does not have this capacity, so that online shopping can be less encouraging of impulse purchases than shopping in physical stores ( Moreira et al., 2017 ).

Researches developed by Aragoncillo and Orús (2018) reveal that 40.0% of consumers spend more money than planned, in physical stores compared to 25.0% in online purchases. This situation can be explained by the fact that consumers must wait for the product to be delivered when they buy online and this time interval may make impulse purchases unfeasible.

Following the logic of Platania et al. (2017) we consider that impulse buying takes socially accepted behavior to the extreme, which makes it difficult to distinguish between normal consumption and pathological consumption. As such, we believe that compulsive buying behavior does not depend only on a single variable, but rather on a combination of sociodemographic, emotional, sensory, genetic, psychological, social, and cultural factors. Personality traits also have an important role in impulse buying. Impulsive buyers have low levels of self-esteem, high levels of anxiety, depression and negative mood and a strong tendency to develop obsessive-compulsive disorders. However, it appears that the degree of uncertainty derived from the pandemic that hit the world and the consequent economic crisis, seems to have changed people's behavior toward a more planned and informed consumption ( Sheth, 2020 ).

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Aragoncillo, L., and Orús, C. (2018). Impulse buying behaviour: na online-offline comparative and the impact of social media. Spanish J. Market. 22, 42–62. doi: 10.1108/SJME-03-2018-007

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Burton, J., Gollins, J., McNeely, L., and Walls, D. (2018). Revisting the relationship between Ad frequency and purchase intentions. J. Advertising Res. 59, 27–39. doi: 10.2501/JAR-2018-031

Ding, Y., DeSarbo, W., Hanssens, D., Jedidi, K., Lynch, J., and Lehmann, D. (2020). The past, present, and future of measurements and methods in marketing analysis. Market. Lett. 31, 175–186. doi: 10.1007/s11002-020-09527-7

Falebita, O., Ogunlusi, C., and Adetunji, A. (2020). A review of advertising management and its impact on consumer behaviour. Int. J. Agri. Innov. Technol. Global. 1, 354–374. doi: 10.1504/IJAITG.2020.111885

Gogoi, B., and Shillong, I. (2020). Do impulsive buying influence compulsive buying? Acad. Market. Stud. J. 24, 1–15.

Google Scholar

Khan, M., Tanveer, A., and Zubair, S. (2019). Impact of sales promotion on consumer buying behavior: a case of modern trade, Pakistan. Govern. Manag. Rev. 4, 38–53. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3441058

Kumar, A., Chaudhuri, S., Bhardwaj, A., and Mishra, P. (2020). Impulse buying and post-purchase regret: a study of shopping behavior for the purchase of grocery products. Int. J. Manag. 11, 614–624. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3786039

Malter, M., Holbrook, M., Kahn, B., Parker, J., and Lehmann, D. (2020). The past, present, and future of consumer research. Market. Lett. 31, 137–149. doi: 10.1007/s11002-020-09526-8

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Meena, S. (2018). Consumer psychology and marketing. Int. J. Res. Analyt. Rev. 5, 218–222.

Moreira, A., Fortes, N., and Santiago, R. (2017). Influence of sensory stimuli on brand experience, brand equity and purchase intention. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 18, 68–83. doi: 10.3846/16111699.2016.1252793

Pandya, P., and Pandya, K. (2020). An empirical study of compulsive buying behaviour of consumers. Alochana Chakra J. 9, 4102–4114.

Platania, M., Platania, S., and Santisi, G. (2016). Entertainment marketing, experiential consumption and consumer behavior: the determinant of choice of wine in the store. Wine Econ. Policy 5, 87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.wep.2016.10.001

Platania, S., Castellano, S., Santisi, G., and Di Nuovo, S. (2017). Correlati di personalità della tendenza allo shopping compulsivo. Giornale Italiano di Psicologia 64, 137–158.

Pradhan, D., Israel, D., and Jena, A. (2018). Materialism and compulsive buying behaviour: the role of consumer credit card use and impulse buying. Asia Pacific J. Market. Logist. 30,1355–5855. doi: 10.1108/APJML-08-2017-0164

Reisch, L., and Zhao, M. (2017). Behavioural economics, consumer behaviour and consumer policy: state of the art. Behav. Public Policy 1, 190–206. doi: 10.1017/bpp.2017.1

Sheth, J. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 on consumer behavior: will the old habits return or die? J. Bus. Res. 117, 280–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.059

Sohn, Y., and Ko, M. (2021). The impact of planned vs. unplanned purchases on subsequent purchase decision making in sequential buying situations. J. Retail. Consumer Servic. 59, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102419

Stankevich, A. (2017). Explaining the consumer decision-making process: critical literature review. J. Int. Bus. Res. Market. 2, 7–14. doi: 10.18775/jibrm.1849-8558.2015.26.3001

Varadarajan, R. (2020). Customer information resources advantage, marketing strategy and business performance: a market resources based view. Indus. Market. Manag. 89, 89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.03.003

Wertenbroch, K., Schrift, R., Alba, J., Barasch, A., Bhattacharjee, A., Giesler, M., et al. (2020). Autonomy in consumer choice. Market. Lett. 31, 429–439. doi: 10.1007/s11002-020-09521-z

Keywords: consumer behavior, purchase intention, impulse purchase, emotional influences, marketing strategies

Citation: Rodrigues RI, Lopes P and Varela M (2021) Factors Affecting Impulse Buying Behavior of Consumers. Front. Psychol. 12:697080. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.697080

Received: 19 April 2021; Accepted: 10 May 2021; Published: 02 June 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Rodrigues, Lopes and Varela. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rosa Isabel Rodrigues, rosa.rodrigues@isg.pt

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Impulse buying: a meta-analytic review

- Review Paper

- Open access

- Published: 09 July 2019

- Volume 48 , pages 384–404, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Gopalkrishnan R. Iyer 1 ,

- Markus Blut 2 ,

- Sarah Hong Xiao 3 &

- Dhruv Grewal 4

87k Accesses

181 Citations

92 Altmetric

10 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Impulse buying by consumers has received considerable attention in consumer research. The phenomenon is interesting because it is not only prompted by a variety of internal psychological factors but also influenced by external, market-related stimuli. The meta-analysis reported in this article integrates findings from 231 samples and more than 75,000 consumers to extend understanding of the relationship between impulse buying and its determinants, associated with several internal and external factors. Traits (e.g., sensation-seeking, impulse buying tendency), motives (e.g., utilitarian, hedonic), consumer resources (e.g., time, money), and marketing stimuli emerge as key triggers of impulse buying. Consumers’ self-control and mood states mediate and explain the affective and cognitive psychological processes associated with impulse buying. By establishing these pathways and processes, this study helps clarify factors contributing to impulse buying and the role of factors in resisting such impulses. It also explains the inconsistent findings in prior research by highlighting the context-dependency of various determinants. Specifically, the results of a moderator analysis indicate that the impacts of many determinants depend on the consumption context (e.g., product’s identity expression, price level in the industry).

Similar content being viewed by others

Compulsive Buying Behavior: Relationship with Impulse Buying and a Proposed Model of Antecedents

Online Impulse Buying – Integrative Review of Social Factors and Marketing Stimuli

Investigating Impulse Buying and Variety Seeking: Towards a General Theory of Hedonic Purchase Behaviors

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Consumers spend $5,400 per year on average on impulse purchases of food, clothing, household items, and shoes (O’Brien 2018 ). Thus, there is considerable need to investigate consumer impulse buying, defined as episodes in which “a consumer experiences a sudden, often powerful and persistent urge to buy something immediately” (Rook 1987 , p. 191). Products purchased impulsively often get assigned to a distinct category in marketing texts, yet decades of research reveal that impulsive purchases actually are not restricted to any specific product category. As Rook and Hoch ( 1985 , p. 23) assert, “it is the individuals, not the products, who experience the impulse to consume.”

Academic research that explores the various triggers of impulse buying consists of three main schools of thought. First, some scholars argue that individual traits lead consumers to engage in impulse buying (e.g., Verplanken and Herabadi 2001 ). For example, people who are impulsive are more likely to engage in impulse buying (Rook and Hoch 1985 ), whereas those who do not display this trait may be less likely to engage in spontaneous behaviors while shopping. Among the psychological factors that might evoke impulse buying, researchers have explored the traits of sensation seeking, impulsivity, and representations of self-identity. Second, both motives and resources might drive impulse buying. Researchers have identified the effects of two types of motives (hedonic and utilitarian), as well as subjective norms, and argued that mere impulsiveness is often not strong enough to trigger impulse buying. Instead, the availability of resources coupled with a failure of self-control also is required to enact impulse buying (Baumeister 2002 ; Hoch and Loewenstein 1991 ). Considerable research has investigated the specific influences of different types of resources, including psychic, time, and money resources (Vohs and Faber 2007 ), with the assumption that resource-based motives, availability, and constraints impact consumer impulse buying. Third, some studies focus on the role of marketing drivers, highlighting how impulse buying can result from store or shelf placements, attractive displays, and in-store promotions. This view holds that impulse buying can be influenced, so retailers invest in marketing instruments designed to trigger it (Mattila and Wirtz 2001 ).

Although these diverse research streams approach impulse buying from different angles and have established considerable insights into its triggers, a unified and comprehensive view of the drivers of impulse buying would further enhance our understanding. We perform a meta-analysis on an accumulation of prior empirical research, focusing on disparate drivers and the most impactful antecedents, and the substantive insights obtained from the estimation of effect sizes. Our study can guide further research and the results also could aid managers in crafting strategies to stimulate impulse purchases by targeting the most receptive customers and investing in effective marketing campaigns. In addition to the direct effects of various antecedents on impulse buying, our proposed framework identifies several mediating mechanisms, including self-control (Vohs and Faber 2007 ) and positive and negative emotions (Rook and Gardner 1993 ). We test the joint effects of emotions and self-control, which enables us to specify their concurrent mediating roles, as well as the potential for serial moderation (i.e., self-control influences emotions). Apart from the typical study moderators, we examine industry moderators—namely, the average price level, advertising, and distribution intensity in the industry, as well as the identity expression capacity of the product category—in line with Rook and Fisher’s ( 1995 , p. 312) call for “a better understanding of various contextual factors that are also likely to contribute to this relationship [between determinants and impulse buying].” The precise roles of these moderating variables have not been explored in prior impulse buying studies, and a better understanding of their influence can provide new insights and spur further in-depth research.

Our use of a meta-analysis is in line with calls in recent research (Grewal et al. 2018b ; Palmatier et al. 2018 ) highlighting the importance of such integrative reviews. An earlier meta-analysis by Amos et al. ( 2014 ) summarized the impacts of various factors on consumer impulse buying; our review extends on their work in several ways. First, we recognize the diverse perspectives on impulse buying and the need to obtain a more comprehensive understanding by combining insights from different research streams. To this end, we have sourced extensively and include 186 papers in our meta-analysis, compared with 63 in Amos et al. ( 2014 ). Second, Amos et al. focus primarily on main effects, whereas we examine moderators and mediators, in addition to the main effects. This scrutiny of the moderating effects also allows us to consider individual relationships rather than pool the effect sizes of all antecedents (Amos et al. 2014 ) and thus identify stronger and weaker effects. Third, by examining mediating effects, we can test alternate theory-based relationships of the various antecedents on impulse buying. The resulting insights help provide a more inclusive understanding of impulse buying as compared with the use of only one theoretical perspective.

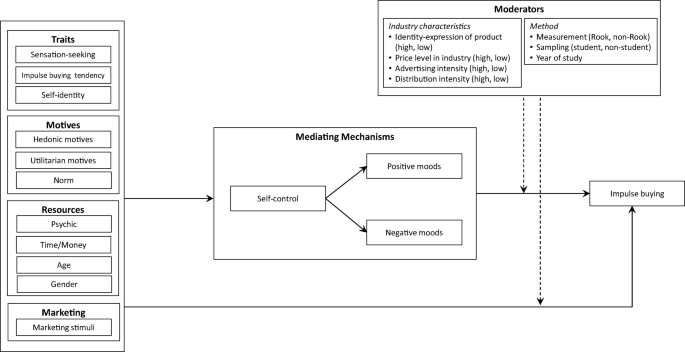

Conceptual framework

Several determinants of impulse buying appear in prior research. In line with Dholakia ( 2000 ), we explore the effects of trait determinants, motives, resources, and marketing stimuli on impulse buying. Beyond these categories of main effects, our integrated model explores their impacts through the mediation of self-control and individual emotional states as well (Mehrabian and Russell 1974 ). We also account for contextual differences in effects by examining the moderating influences of industry-related characteristics. Furthermore, we consider the possible influence of study characteristics (i.e., impulse buying measure, sample composition, and publication year) on the effects obtained. Our conceptual model is in Fig. 1 , and we offer a summary of the predicted relationships in Table 1 .

Meta-analytic framework

Determinants of impulse buying

Trait and related determinants.

Several individual traits and self-identity may serve as internal sources of impulse buying. Psychological impulses strongly influence impulse buying (Rook 1987 ; Rook and Hoch 1985 ), and prior research shows that people who score high on impulsivity trait measures are more likely to engage in impulse buying (Beatty and Ferrell 1998 ; Rook and Fisher 1995 ; Rook and Gardner 1993 ). Moreover, other traits are also associated with impulse buying and studies in the past have attempted to study their impacts as well (e.g., Mowen and Spears 1999 ; Sharma et al. 2010 ).

First, we examine the role of sensation-seeking as having a direct impact on impulse buying. Sensation-seeking, variety-seeking, novelty-seeking, and similar dispositions are arguably distinct from other traits such as impulsivity and reported as contributing to impulse buying (Punj 2011 ; Sharma et al. 2014 ; Van Trijp and Steenkamp 1992 ). Second, an impulse buying tendency , which includes the trait of impulsivity, reflects an enduring disposition to act spontaneously in a specific consumption context. This well-recognized concept captures a relatively enduring consumer trait that produces an urge or motivation for actual impulse buying (Rook and Fisher 1995 ). Impulse buying tendencies, are easier to observe than other traits and are also highly predictive of impulse buying (Beatty and Ferrell 1998 ; Rook and Gardner 1993 ). Third, buyer-specific beliefs about self-identity and its deficits influence impulse buying decisions (Dittmar et al. 1995 ). Impulse purchases are more likely to involve items that are symbolic of a preferred or ideal self as well as products that offer high identity-expressive potential, to compensate for the buyer’s own identity deficits (Dittmar et al. 1995 ; Dittmar and Bond 2010 ). However, contextual factors may play a role on the impacts of such perceptions of identity deficits (e.g., Dittmar et al. 2009 ).

Motives and norms

Consumers’ motives, such as hedonic or utilitarian motives , are important internal sources of impulse buying that reflect goal-directed arousal, leading to specific beliefs about consumption. For example, consumers may believe that buying objects will provide emotional gratification, compensation, rewards, or else minimize their negative feelings. Such beliefs may be especially relevant if the objects are unique and feature a marked opportunity cost, such that they need to be purchased immediately (Rook and Fisher 1995 ; Vohs and Faber 2007 ).

Norms invoked by consumers about their own impulsiveness also might affect impulse buying decisions. As Rook and Fisher ( 1995 , p. 307) explain, “consumers’ own prior impulse buying experiences may serve as a basis for independent, internalized evaluations of impulse buying as either bad or good.” From a self-regulation perspective, when prior impulse buying evokes positive experiences, consumers likely engage in it again, as a promotion-focused strategy (Verplanken and Sato 2011 ).

Customers with greater psychic resources or interest in a product category are more likely to engage in impulse buying, whereas those who lack the necessary resources (time, money) engage less in impulse buying (Hoch and Loewenstein 1991 ; Jones et al. 2003 ; Kacen and Lee 2002 ). Age and gender might capture shopping-related resources, such that impulse buying tendencies often are more prevalent among specific social or demographic cohorts (Kacen and Lee 2002 ; Tifferet and Herstein 2012 ; Wood 1998 ). Drawing from prior research, Kacen and Lee ( 2002 ) offer that younger shoppers may be more likely to buying impulsively while older adults may be better able to regulate their emotions and engage in self-control.

Several research and practical observations have highlighted gender differences in shopping (e.g., Underhill 2000 ). Dittmar et al. ( 1995 ) find that men and women are likely to buy different products to buy impulsively and also use different buying considerations when buying on impulse. Also, it has been found that women are more likely as compared to men to experience regret or a mixture of pleasure and guilt (Coley and Burgess 2003 ).

- Marketing stimuli

Marketers deliberately design external stimuli to appeal to shoppers’ senses (Eroglu et al. 2003 ). Managers expend substantial time and effort in designing retail environments and the resulting retail interactions to increase shoppers’ psychological motivation to purchase (Berry et al. 2002 ; Foxall and Greenley 1999 ). It has been estimated that about 62% of in-store purchases are made impulsively and online buyers are more likely to be impulsive (Chamorro-Premuzic 2015 ). Thus, impulse buying can be triggered by various marketing stimuli such as merchandise, communications, store atmospherics, and price discounts (Mohan et al. 2013 ).

Mediators of impulse buying

Baumeister ( 2002 ) has established the importance of motives and resource depletion for driving impulse buying; therefore, we also consider whether self-control and emotions might be triggered. By including these mediating mechanisms in our meta-analysis, we avoid over- or underestimating the importance of various impulse buying triggers. In particular, we assess the joint effects of emotions and self-control, which enables us to specify their concurrent mediating roles, as well as the potential for serial mediation (i.e., self-control influences emotions).

Self-control as a mediator

Countering prior arguments that impulse purchases stem from irresistible urges, Baumeister ( 2002 ) has argued that individuals’ self-control can and do resist such urges. Muraven and Baumeister ( 2000 ; p. 247) submit that self-control, or the “control over the self by the self,” involves attempts by individuals to curb their desires, conform to rules and change how think, feel or act. Also, individuals differ in self-control leading to the view that self-control is an inherent strength or trait (Baumeister 2002 ). It has also been argued that a failure of self-control could occur due to conflicting goals, reduction in self-monitoring or depletion of mental resources (Baumeister 2002 ; Verplanken and Sato 2011 ). The depletion of mental resources, or “ego depletion,” may also be temporal, i.e., more likely to occur at the end of the day (Baumeister 2002 ; p. 673). The “ever-shifting conflict between desire and willpower” (Vohs and Faber 2007 , p. 538) demonstrates the importance of self-control as a key mediator in the impacts of various antecedents noted in our model and impulse buying.

Emotions as mediators

Environmental psychology research, and particularly the stimulus–organism–response model proposed by Mehrabian and Russell ( 1974 ), highlights experienced emotions as potential mediating constructs. Input variables such as environmental stimuli or individual traits jointly influence individual affective responses, which then induce response behaviors (Baker et al. 1992 ). Verplanken and Herabadi ( 2001 ) explain that customers engaging in impulse buying tend to display emotions at any point of time during the purchase (i.e., before, during, or after). Extant findings are somewhat inconsistent though. It has been argued that impulse buying behavior relates strongly to positive emotions and feelings such that impulse buyers experience more positive emotions such as delight and consequently spend more (Beatty and Ferrell 1998 ). Impulse buyers have a strong need for arousal and experience an emotional lift from persistent repetitive purchasing behaviors (O'Guinn and Faber 1989 ; Verplanken and Sato 2011 ). Such arousal even might be a stronger motive for impulse buying than product ownership (Dawson et al. 1990 ).

Rook and Gardner ( 1993 ) acknowledge that while pleasure is an important precursor, negative mood states such as sadness, can also be associated with impulse buying. For example, various studies suggest self-gifting to be a form of retail therapy that helps customers in managing their moods (Mick and Demoss 1990 ; Rook and Gardner 1993 ; Vohs and Faber 2007 ). Other researchers concur that impulse buying can serve to manage or elevate negative mood states but also suggest that this influence occurs through a self-regulatory function (Rook and Gardner 1993 ; Verplanken et al. 2005 ). Thus, emotional states—whether positive or negative—likely affect impulse buying, but we find no consensus about whether or how negative moods, positive moods, or both determine impulse buying uniquely.

Finally, research rooted in environmental psychology asserts that exposure to environmental stimuli, consumers’ personalities, and personal motives can cause specific (positive or negative) emotional reactions (e.g., Babin et al. 1994 ; Donovan and Rossiter 1982 ; Mehrabian and Russell 1974 ). These in turn mediate the impacts of personal, situational, and external factors on impulse buying (Parboteeah et al. 2009 ; Verhagen and van Dolen 2011 ). The limited empirical evidence on the mediating role of emotions refers to specific contexts; for example, Adelaar et al. ( 2003 ) show that pleasure, dominance, and arousal triggered at the moment of purchase mediate the effect of a media format on impulse buying intentions online. Verhagen and van Dolen ( 2011 ) found that positive emotions mediate the effects of consumer beliefs about online stores and their likelihood of buying impulsively. Store environments and circumstances such as time and money resources also might prompt negative emotional reactions (Lucas and Koff 2014 ; Vohs and Faber 2007 ), suggesting the need for more empirical evidence to determine which emotions are more prominent.

The serial mediation of self-control and emotions also deserves examination. The motivational role of self-control also suggests that a successful exercise of self-control may also contribute to positive affect; in other words, individuals with higher self-control not only resist temptations successfully but may experience other consequent states such as fewer emotional problems and greater life satisfaction (Baumeister 2002 ; Baumeister et al. 2008 ; Hofmann et al. 2012 ; Tice et al. 2001 ). The conceptualization of self-control as a strength and self-control failure as ego-depletion (c.f., Baumeister 2002 ) also paves the way for understanding how the exercise of self-control and the unpleasant consequence of self-regulation of a pleasant task may contribute to seeking other pleasurable pursuits (Finley and Schemichel 2018 ). Thus, individuals may counter the distasteful after-effects of a self-control act by pursuing opportunities that would contribute to positive emotions (Finley and Schemichel 2018 ). This view of self-control views ego-depletion as a process, whereby the exercise of self-control in one time period leads to the individual seeking subsequent positive experiences (Finley and Schemichel 2018 ). Another view of self-control offers that self-control may not be all about inhibitions and restrictions; the trait of self-control may also engage in a promotion focus and thereby engage in initiatory behaviors towards achieving the same goal (Cheung et al. 2014 ). While the above discussion sheds light on the relationship between self-control and positive emotions, there is a lack of clarity in current literature on the precise direction of the relationship between self-control and emotional states relative to impulse buying as well as the impact of self-control on negative emotions.

Contextual moderators

We seek novel insights by examining industry characteristics as potential contextual moderators. Based on extant studies, we identify the price levels, advertising, and distribution intensity within the industry context as moderators that may influence the effects of other factors on impulse buying. The identity expression capability of the products themselves could moderate the impacts of the various determinants too. Prior impulse buying studies do not test the effects of these moderators; to derive our predictions, we thus turn to relationship marketing research that reveals how industry-level variables determine effectiveness (Fang et al. 2008 ). Product price levels matter, because financial constraints suppress impulse purchases (Rook and Fisher 1995 ), and impulse buying triggers are less effective in more expensive product categories. In their meta-analysis, Samaha et al. ( 2014 ) find that advertising intensity in a specific industry reduces the effectiveness of a firm’s communication activities. We posit that similarly, impulse buying triggers may be less effective in industries in which all firms invest heavily in advertising, because consumers are less likely to recognize and consider these various triggers. In addition, distribution intensity in an industry might influence impulse buying, because the urge to purchase likely increases when products are rare or exclusive (Troisi et al. 2006 ). Finally, some products are more prone to impulse purchases, especially if they symbolize a preferred or ideal self (Dittmar et al. 1995 ; Dittmar and Bond 2010 ). Thus, we anticipate differing effectiveness of impulse buying triggers according to the product.

Method moderators

Meta-analyses frequently consider the influence of the methods adopted by the included studies, such as how they measure key constructs, on the strength of the focal relationships. Impulse buying studies frequently use different measures for similar constructs; we use the scale for buying impulse developed by Rook ( 1987 ) as a baseline to assess whether other measures perform differently. Meta-analyses also can reveal whether the use of specific samples influences the findings (Orsingher et al. 2009 ). In particular, student samples tend to be more homogeneous than non-student samples and thus produce stronger effect sizes. Finally, we assess the influence of the study period. The emergence of the Internet and advanced communication technologies have left customers more knowledgeable, with altered expectations of retailers (Blut et al. 2018 ). Accordingly, we consider whether customers’ impulse buying behaviors might have changed over time.

Data collection and coding

We collected the data for this study by searching electronic databases, including EBSCO, Proquest, Ingenta Journals, Elsevier Science Direct, Google Scholar, the web, and several pertinent leading journals (e.g., Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Journal of Consumer Research, Journal of Marketing, Journal of Marketing Research ). We also identified relevant articles by examining the reference lists of the collected articles. Our search used various terms, including “impulse buying” and “impulsive buying,” “impulsivity,” “compulsive buying,” and “unplanned buying,” and encompassed titles, abstracts, and keywords. The document types included articles and reviews (c.f., book review); the language was English; and the subject areas spanned marketing and advertising, management, business, economics, sociology, and psychology. We also obtained some unpublished studies from their authors. We sent 159 emails to authors of published papers seeking at least minimally relevant statistics for conducting the analysis. After excluding theoretical papers, qualitative studies, book reviews, studies that mention but do not measure impulse buying, and studies that do not report the necessary effect sizes, we pared down the list of 386 articles to a final data set of 186 articles reporting empirical results. Footnote 1

We coded each effect size according to the relationship of the independent variables (traits, motives, resources, and marketing stimuli), the mediators (self-control, positive emotions, and negative emotions) and impulse buying. We also coded the industry and method moderator variables, such that we assessed industry characteristics (i.e., product-identity relation, price level, advertising intensity, and distribution intensity) using the industry description reported by the studies. We similarly coded the method moderators (i.e., study year, measurement of impulse buying, and student sample) using information provided in each study. Two coders achieved agreement greater than 90% and discussed any inconsistencies, using the construct definitions in Table 2 to classify all the variables.

We included studies that reported (1) correlations (r) between the variables of interest, (2) the standardized regression coefficients (beta coefficients), (3) F- or t-values, or (4) frequencies, to calculate as as many effect sizes, so as to enhance the generalizability (Peterson and Brown 2005 ).

Integration of effect sizes

Correlation coefficients were used as effect sizes in our meta-analysis. If such coefficients were not reported in the collected studies, we transformed alternative statistics, such as regression coefficients, into correlations (Peterson and Brown 2005 ). Following Peterson and Brown ( 2005 ), we imputed correlations from the beta coefficients using the formula: r = .98β + .05λ with λ = 1 when β > 0 and λ = 0 when β < 0. Some studies also report more than one correlation for the same relationship between two constructs, in which case, we averaged the two correlations and treated them as if they were from a single study (Hunter and Schmidt 2004 ). We did not have enough effect sizes to include some determinants in all analyses, such as the four marketing stimuli of communication, price stimuli, store ambience, and merchandise. We therefore examined these determinants separately when possible and merged them as necessary to include them in other analyses. If a study had measured more than one of the four instruments, we calculated an average effect size for the aggregate marketing stimuli variable. This approach ensures the use of only one aggregate marketing stimuli effect size for each study. After transforming and averaging the effect sizes, the total data set in the meta-analysis consists of 968 effect sizes, extracted from 231 samples obtained from 186 articles. The total combined sample includes 75,434 respondents.

We used a random-effects approach (Hunter and Schmidt 2004 ) to calculate the average correlations. Effect sizes were corrected for measurement error in the dependent and independent variables using the coded reliability coefficients. We followed the Hunter and Schmidt ( 2004 ) recommendation of dividing the correlations by the product of the square root of the respective reliabilities of the two constructs involved. Further, reliability-adjusted correlations were weighted by sample size to adjust for sampling error. It has been recommended that reliability-adjusted effect sizes should be transformed into Fisher’s z coefficients before weighting them by sample size (Kirca et al. 2005 ). This transformation is not without controversies, and some studies suggest that Fisher’s z overestimates true effect sizes by 15%–45% (Field 2001 ). However, when we compare the results of both approaches, we find no significant differences.

Next, for each sample size–weighted and reliability-adjusted correlation, we calculated standard errors and 95% confidence intervals. We used a chi-square test and applied a 75% rule-of-thumb to assess the homogeneity of the effect size distribution (Hunter and Schmidt 2004 ). To assess the robustness of our results and potential publication bias, we estimated Rosenthal’s ( 1979 ) fail-safe N; in other words, the estimation of the number of studies that had null results and therefore not published before the Type I error probability can be brought to a barely significant level ( p = .05). We also tested the influence of sample size and effect size outliers on integrated effect sizes, but the results remained largely the same (Geyskens et al. 2009 ). To assess the practical relevance of the different determinants, we calculated the shared variance with impulse buying for each predictor, as well as the binomial effect size display (BESD) (Grewal et al. 2018b ), which indicates the likelihood that a customer (e.g., female) would purchase impulsively compared with a reference group (e.g., male customers). A value greater than 1 indicates a greater relative likelihood, whereas a value lower than 1 signals a lower likelihood.

Descriptive statistics

Direct effects.

As Table 3 indicates, the averaged effect sizes for most motives, resources, and trait predictors are significant; however, socio-demographic predictors seem to matter less for impulse buying. We find strong support for the impacts of the three trait-related predictors on impulse buying. As expected, an individual's tendency to act impulsively has a stronger effect than other traits, reflecting its stronger link to the behavior of interest.

Utilitarian and hedonic motives show about equal impacts on impulse buying; further research should pay more attention to these determinants. We find support for gender effects but observe no differences for age. The former results are in line with prior research that suggests women generally are more likely to purchase impulsively than men (Dittmar et al. 1995 ). However, the insignificant results for age suggests there are not many differences between older and younger customers with regard to spending money impulsively. Moreover, we find that marketing stimuli exert a direct influence on customers’ impulse buying behavior. When examining the specific marketing instruments, we find the strongest effects for communication and price stimuli and weaker effects for store ambience and merchandise.

We uncover significant effects for emotions and self-control (Table 4 ). Descriptive statistics were also examined to gauge the impact of the predictors on the mediators (Table 4 ); 30 of the 39 predictor–mediator relationships (77%) are significant. Thus, we obtain a preliminary indication of the mediating roles of emotions and self-control, and we can proceed to test the proposed mediating effects in the SEM.

The shared variances and BESD give some indication of the practical relevance of different determinants. Using these criteria, we observe strong effects of impulse buying tendencies, utilitarian motives, and communication. All the significant relationships are robust to publication bias because the file-drawer N is many times greater than the tolerance levels proposed by Rosenthal ( 1979 ). We also examined funnel plots and do not find any indication of publication bias. In all cases, the significant chi-square tests of homogeneity suggest moderation.

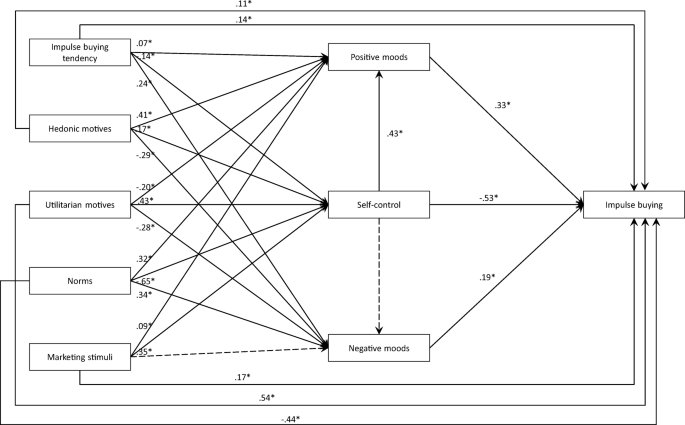

Evaluation of structural equation model

We tested the mediating effects using structural equation modeling (SEM) and included variables for which correlations with all other variables could be identified. The complete correlation matrix includes correlations between the most often studied variables in prior research (Table 5 ). It served as the input to LISREL 8.80 and the harmonic mean of all sample sizes ( N = 1726) was used as input. Since the harmonic mean is lower than the arithmetic mean, SEM estimations are more conservative (Viswesvaran and Ones 1995 ). Note that since each construct had only a single indicator and since measurement errors were taken into account when estimating the mean effect sizes, the error variances in the SEM could be set to 0. The different marketing instruments could not be individually included in the SEM, due to the small number of effect sizes, so we aggregated all marketing instruments into one determinant variable and examined its influence in the SEM; if a study included two or more marketing stimuli effects, we averaged them. The proposed model with both mediators and the effect of self-control on emotions performs well and displays a good fit (Fig. 2 ).

Results of the structural equation model. Notes : A dotted line indicates that the path is not significant. Model fit: χ 2 /1 = 67.74; confirmatory fit index = .99; goodness-of-fit index = .99; root mean residual = .02; standardized root mean residual = .02

Positive moods

The SEM results suggest that positive moods are important mediators (Fig. 2 ). Customers with stronger hedonic motives are more likely to experience positive feelings; customers with utilitarian motives are less likely to experience such feelings. Those with favorable subjective norms and high self-control also experience positive moods. These effects are new to extant impulse buying literature. Similarly, customers who are generally high in impulsivity experience positive feelings. Finally, marketing stimuli relate significantly to positive feelings, though the effect is relatively weak.

Negative moods

Negative mood states relate significantly to impulse buying, and each of the determinants link to this mediator, with the exception of marketing stimuli and self-control. Customers high in hedonic and utilitarian motives are less likely to experience negative moods. Favorable subjective norms increase the likelihood of negative feelings. Impulse buying tendency is positively related to the experience of negative moods. The insignificance of marketing stimuli suggests that the stimuli do not trigger negative moods in customers. Self-control also does not reduce the experience of negative emotions.

- Self-control

Unlike mood states, self-control reduces the likelihood of impulse purchases. This cognition intervenes when customers experience an urge to buy impulsively. According to the SEM results, several predictors either trigger individual awareness of the long-term consequences of spending or reassure consumers that spending is acceptable. For example, customers high in impulsivity are less likely to exhibit self-control. Subjective norms that encourage impulse buying lower self-control perceptions, but marketing stimuli serve to increase self-control. Finally, hedonic and utilitarian motives increase self-control perceptions. The positive effect of marketing stimuli on self-control suggests that customers are aware of how firms try to influence them to make them impulsive purchases.

Similar to Pick and Eisend ( 2014 ), we tested the importance of mediation effects using two approaches. First, we examined the ratio of indirect effects to total effects as displayed in Table 6 . We find significant indirect effects and high ratios for most determinants, including self-control (20%), impulse buying tendency (46%), utilitarian motives (34%), norms (49%), and marketing stimuli (39%). Only the indirect effect of hedonic motives is insignificant, leading to a low ratio of indirect effects to total effects (8%). The direct, indirect, and total effects differ for some determinants; self-control has a negative direct effect on impulse buying, yet the indirect effect through mediators is positive, which mitigates the total negative effect. Impulse buying tendency has positive direct and indirect effects on impulse buying, such that the total effect is nearly twice as strong as the direct effect. Utilitarian motives have a positive direct effect on impulse buying and a negative indirect effect that lowers the total effect. Norms display a negative direct effect and a positive indirect effect; we observe the opposite effects for marketing stimuli. The mediation model thus provides a clearer view of how these determinants influence impulse buying.

Second, we compare the proposed model, which assumes partial mediation effects, with two models with only indirect effects of the determinants through moods and self-control (full mediation). As suggested by Pick and Eisend ( 2014 ), we compare the models using a chi-square difference test (Δχ 2 /df). Both full mediation models exhibit significantly worse model fit than the proposed model (mood: Δχ 2 /df = 630.51/6, p < .01; self-control: Δχ 2 /df = 755.28/8, p < .01). Thus, the mediating effects of moods and self-control are partial rather than full.

Moderator analysis results

The need for a moderator analysis was assessed through the chi-square test of homogeneity and a 75% rule (Hunter and Schmidt 2004 ). The 75% rule indicates that if the proportion of variance in the distribution of effect sizes attributed to sampling error and other artifacts is less than 75%, a moderator analysis is warranted. In our results, the chi-square value is significant in all cases, and the 75% rule suggests values lower than 75%, in support of a moderator analysis. We coded several moderators in our random effects regression model as dummy variables, including the four industry moderators: product identity relation (1 = high expressive, 0 = low expressive), price level (1 = high, 0 = low), advertising intensity (1 = high, 0 = low), and distribution intensity (1 = high, 0 = low). Footnote 2 For the two method moderators, impulse buying measure (1 = Rook, 0 = non-Rook) and sample (1 = student, 0 = non-student), we used dummy codes. The year of the study came directly from the articles.

Using meta-regression procedures suggested by Lipsey and Wilson ( 2001 ) and the provided macros, we assess the influence of the moderators in our model with random-effects regression (Hunter and Schmidt 2004 ). Using reliability-corrected correlations as the dependent variable, we conducted tests of the moderators for 18 predictor variables and regressed correlations on four industry variables and three method variables. To test moderation effects, we ensured that at least 10 effect sizes were available (Samaha et al. 2014 ).

Product identification

We confirm a moderating influence of product identification (Table 7 ). If a product’s expressiveness is high (i.e., product identity is coded as 1 for high expressiveness), some predictors lose their relevance, including self-identity and subjective norms. Products that facilitate consumer self-expression are more likely to be bought impulsively, because they represent a preferred or ideal self (Dittmar et al. 1995 ; Dittmar and Bond 2010 ). Products with high expressiveness also suppress the effects of norms. In these conditions, other determinants become less effective. However, some determinants related to communication and negative feelings gain importance, because consumers are very sensitive with regard to their self-perceptions.

Price level

As expected, the average price level of products in an industry buffers the impacts of several predictors. Most predictors lose some relevance when prices are high (i.e., price level is coded as 1), including sensation-seeking, impulse buying tendency, hedonic motives, utilitarian motives, psychic resources, and positive moods. Only self-control gains importance, in line with our reasoning. Higher prices alert consumers to the financial consequences of their urge to buy impulsively, making these determinants less effective (but self-control more effective).

Advertising intensity

The influence of advertising is quite interesting. On the one hand, it appears to increase desire for certain products, so some predictors gain relevance. On the other hand, the predictors may lose relevance, because products seem less unique when they are advertised everywhere. Negative moods and merchandise gain importance with greater advertising intensity, but norms, psychic resources, and store ambience matter less.

Distribution intensity

Product availability in an industry depends on its distribution intensity. For example, Dholakia ( 2000 ) explains that physical proximity is essential for the experience of an impulsive urge, but a product that is unusually difficult to purchase may be more appealing to customers than products that are available everywhere. We anticipated and find that at least some impulse buying predictors, such as utilitarian motives, psychic resources, merchandise, and negative mood states, become less effective when a product is more widely available. Moreover, communication gains relevance with greater distribution intensity.

When examining the moderating influence of the method adopted in the different studies, we find that several predictors, such as impulse buying tendency and utilitarian motives, gain importance over time. We do not observe a specific pattern for the measures employed. The results with regard to the measures used in the studies suggest that the widely employed Rook scale performs as well as alternative impulse buying measures. We also find generally weaker effects in studies using student samples. In further meta-regression models, we assessed the influence of country culture and emerging markets but do not find notable differences.

Implications and directions for further research

This meta-analysis aims to provide a comprehensive and coherent understanding of impulse buying behavior, by synthesizing previous research. Our meta-analytic review seeks deeper insights into impulse buying, and our comprehensive model of impulse buying integrates constructs and relationships from studies over the past four decades of empirical research on impulse buying. The results from our meta-analysis provide new insights into the impacts of various antecedent factors and call particular attention to the tensions between the inherent urge to buy impulsively and the constraints and control on such buying impulses. Also, the results clarify the impacts of marketing stimuli on consumer impulse buying and highlight the context-dependency of impulse buying research. These meta-analysis results in turn suggest several implications for practice and directions for further research.

Managerial implications

Consumer buying on impulse has long been an area of interest for managers; even a small proportion of impulse purchases on each shopping trip or a small base of impulse shoppers can contribute significant annual incremental sales (Rostoks 2003 ). It is therefore important to identify not just which consumers may be more inclined to purchase on impulse but also specific environmental factors that may prompt and encourage impulse buying. Impulse purchases can increase retail sales (top-line) and profits (bottom-line), especially for high-margin products. As summarized in Table 8 , our results suggest employing a variety of marketing strategies.

In their attempt to devise strategies to encourage impulse shopping and/or promote impulse buying behaviors, retailers have not been averse to making large investments in marketing stimuli, such as merchandising, displays, lighting, music, and other environmental factors that might trigger impulse purchases (Mattila and Wirtz 2001 ). Our review acknowledges that impulse buying can be triggered by external factors, so retailers should devise new, unique marketing stimuli to convey the value of their offerings and encourage impulse buying. Yet not all marketing stimuli are equally effective. Communication and price stimuli are more effective in prompting impulse buying than are store ambience and merchandise. Although retailers often devote considerable expenses to store design, store atmosphere, store layout, and merchandise placement, they may be better off investing more in price promotions and advertising, which likely have stronger impulse buying effects.

An important practical insight from this meta-analysis is that though marketing mix stimuli have positive impacts on impulse buying, they also heighten awareness of such tendencies and thus may curb impulse buying overall. This finding suggests consumers are becoming increasingly familiar with firms’ tactics to persuade them to buy impulsively and skeptical of various marketing practices. For practitioners, these findings may be somewhat discouraging; impulse buying is not simply a response to marketing stimuli, and psychological, social, and situational variables also have impacts. Additional research is warranted to understand how shopper skepticism evoked by marketing tactics might inhibit impulse buying. Retailers may need to try harder to devise unique or new marketing stimuli that can get past consumers’ defenses and convey the value of their offers.

The identification of an impulse buying segment of customers would be of great importance to retailers that currently rely solely on marketing stimuli. But if impulse buying were only trait driven, marketing strategy would have no effect on impulse purchases. The good news from our meta-analysis is that impulse buying is triggered by both factors internal to consumers and external marketing stimuli. Thus, it may be possible to identify consumers prone to impulse buying but also specify situations that enable it. That is, marketers could identify a distinct impulse buying segment and then design the shopping environment to make their impulse buying more likely. In some challenging findings though, we show that demographics such as age and gender matter less for predicting impulse buying, so retailers likely need to undertake deeper research into consumer psychographics to identify an impulse buying segment.

Shopping motives, whether hedonic or utilitarian, also matter when it comes to impulse buying. These motives are inherent to the consumer, so marketers should design stores and offers to evoke and facilitate appropriate motives. Yet consumers’ resource constraints (e.g., time, money) curb their buying impulses, so marketers also could focus on devising tactics to reduce the impacts of resource constraints. For example, access to speedy financing and faster checkouts likely help mitigate credit and time constraints.

Consumers with high self-control and those influenced by social norms also may be less prone to impulse buying, because the uninhibited urge to buy impulsively is curbed by self-control and social norms. Understanding these restrictions can help ethical marketers develop stimuli that both facilitate unplanned purchases but discourage purely uninhibited, impulsive purchases that may lead to later regret and consumer dissatisfaction. Ultimately, marketers must choose between making an immediate sale that might produce consumer dissatisfaction and exhibiting concern for the consumer to encourage future patronage. Similarly, both positive and negative emotions enhance impulse buying, and ethical marketers should leverage affective strategies to encourage impulsive purchases that align with available consumer resources. Public policy makers also might take heed of self-control, norms, and emotions to devise policies to reduce unhealthy impulse buying.

Because industry characteristics also matter in impulse buying, managers need to understand how the industry context moderates the impacts of various consumer traits, motives, and resources on impulse buying. Even if impulse buying is common in industries with low price levels, our findings caution that it is not the only relevant industry context; rather, impulse buying also occurs when product–identity relationships are strong. In such contexts, marketers should place due emphasis on communications that encourage impulse buying.

Directions for research

Our meta-analysis, while revealing, was restricted given the lack of sufficient studies testing and/or reporting all possible effects in all possible contexts using multiple methods. In exploring the main effects of various factors on impulse buying (Fig. 1 ), we had to use aggregations in several cases, due to the insufficient number of effects available in prior research. Future studies should undertake explicit examinations of each effect, especially specific marketing stimuli, self-identity, positive and negative moods, specific types of social norms, and consumer resources. The most glaring deficiencies in prior research provide the bases for our recommendations for further research, which we detail in Table 9 and summarize briefly here.

We indicate the effects of various individual drivers, including marketing stimuli, on impulse buying in Table 3 , which suggests an important facilitating role for impulse buying. We test the individual impacts of traits, motives, resources, and stimuli on impulse buying, but interactions among these antecedents also could be influential. For example, experimental research might determine how the effects of traits, motives, and resources on impulse buying are moderated by marketing stimuli (e.g., communication, price, store ambience, merchandise elements). The size of the motive effects (r = .34 for hedonic, r = .36 for utilitarian) implies their potential significance; they could be activated by communications delivered to customers in stores, using digital displays (Roggeveen et al. 2016 ) or mobile devices (Grewal et al. 2018a ). Furthermore, the synergistic effects of various communication and promotional elements on impulse buying warrant further exploration.

Most studies make assumptions about the context, rather than actively manipulating or exploring its effects. In most cases, the context refers solely to the product category (e.g., food, beauty products), shopping environment (e.g., retail store, online), or industry (grocery, apparel). But various other contextual cues could be relevant, such as consumer decision stage, whether consumption is private or public, demographic variables, and whether the shopper is alone or accompanied by someone (Table 9 ). Such contextual cues should function as moderators in future studies to help reveal how various antecedent factors affect impulse buying.

Studies exploring impulse buying also tend to use surveys and examine correlational data. Such descriptive analyses provide generalizable insights, though manipulations of various marketing stimuli, motives, and resources in experiments also could enable causal inferences. Longitudinal research that relies on panel data could also reveal how consumer motives and resources interact with the context to prompt impulse buying. New technologies, such as eye-tracking methods, could demonstrate the specific impacts of marketing stimuli (e.g., product placements) and how consumers’ attention paid to various details in the shopping environment contributes to their impulse buying. Finally, we find some evidence that is contradictory with theoretical predictions, so qualitative research would be helpful to explain why.

Our meta-analytic review aims to provide empirically generalizable, robust findings pertaining to the impacts of various antecedents of impulse buying, its potential mediators, and the moderators of these relationships. As a unique feature, our meta-analysis includes a test of alternate theoretical perspectives that previously have sought to explain impulse buying. As Palmatier et al. ( 2007 ) attest, on the basis of their comparative consideration of multiple theoretical perspectives on interorganizational relationships, various perspectives could receive empirical support individually, but their relative impacts cannot be determined unless all explanatory perspectives are subjected to a comparative test. With the greater number of effects sizes available for each model, achieved by compiling data for the meta-analysis, our comparative test of various perspectives on impulse buying brings the relative impacts of various dominant explanatory factors in each perspective into sharper relief.

In summary, our meta-analysis explores the direct effects of consumer traits, motives, and resources and marketing stimuli on impulse buying, along with the mediating impacts of self-control and positive and negative emotions. Our joint examination of these mediators reveals the inner affective and cognitive psychological processes of impulse buying and their relations. Industry and method moderators also influence impulse buying. This meta-analysis provides a comprehensive summary of extant research, underlying various implications. We hope it also sheds some new lights on directions for research that can continue to enhance our understanding of impulse buying.

The complete list of studies used in this meta-analysis is available from the authors.

For example, grocery retailing involves low product identity relation, low price level, high advertising intensity, and high distribution intensity; the luxury car industry was coded as high product identity relation, high price level, low advertising intensity, and low distribution intensity.

Abratt, R., & Goodey, S. D. (1990). Unplanned buying and in-store stimuli in supermarkets. Managerial and Decision Economics, 11 (2), 111–121.

Article Google Scholar

Adelaar, T., Chang, S., Lancendorfer, K. M., Lee, B., & Morimoto, M. (2003). Effects of media formats on emotions and impulse buying intent. Journal of Information Technology, 18 (4), 247–266.

Amos, C., Holmes, G. R., & Keneson, W. C. (2014). A meta-analysis of consumer impulse buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 21 (2), 86–97.

Andrews, J. C., Durvasula, S., & Akhter, S. H. (1990). A framework for conceptualizing and measuring the involvement construct in advertising research. Journal of Advertising, 19 (4), 27–40.

Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20 (4), 644–656.

Baker, J., Levy, M. L., & Grewal, D. (1992). An experimental approach to make retail store environmental decisions. Journal of Retailing, 68 (4), 445–460.

Google Scholar

Baumeister, R. F. (2002). Yielding to temptation: Self-control failure, impulsive purchasing, and consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 28 (4), 670–676.

Baumeister, R. F., Sparks, E. A., Stillman, T. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2008). Free will in consumer behavior: Self-control, Ego depletion, and choice. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 18 (1), 4–13.

Beatty, S., & Ferrell, M. E. (1998). Impulse buying: Modeling its precursors. Journal of Retailing, 74 (2), 169–191.

Berry, L. L., Seiders, K., & Grewal, D. (2002). Understanding service convenience. Journal of Marketing, 66 (3), 1–17.

Billieux, J., Gay, P., Rochat, L., & Van der Linden, M. (2010). The role of urgency and its underlying psychological mechanisms in problematic behaviours. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48 (11), 1085–1096.

Blut, M., Teller, C., & Floh, A. (2018). Testing retail marketing-mix effects on patronage: A meta-analysis. Journal of Retailing, 94 (2), 113–135.

Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2015), The Psychology of Impulsive Shopping, The Guardian , November 26, https://www.theguardian.com/media-network/2015/nov/26/psychology-impulsive-shopping-christmas-black-friday-sales [Accessed March 13, 2019].

Cheung, T. L., Gillebaart, M., Kroese, F., & Ridder, D. D. (2014). Why are people with higher self-control happier? The effect of trait self-control on happiness as mediated by regulatory focus. Frontiers in Psychology, 5 (July). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00722 .

Cohen, J. B., & Andrade, E. B. (2004). Affective intuition and task-contingent affect regulation. Journal of Consumer Research, 31 (2), 358–367.

Coley, A., & Burgess, B. (2003). Gender differences in cognitive and affective impulse buying. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 7 (3), 282–295.

Davis, R., & Sajtos, L. (2009). Anytime, anywhere: Measuring the ubiquitous Consumer's impulse purchase behavior. International Journal of Mobile Marketing, 4 (1), 15–22.

Dawson, S., Bloch, P. H., & Ridgway, N. M. (1990). Shopping motives, emotional states, and retail outcomes. Journal of Retailing, 66 (winter), 408–427.

Dholakia, U. M. (2000). Temptation and resistance: An integrated model of consumption impulse formation and enactment. Psychology & Marketing, 17 (11), 955–982.

Dittmar, H., & Bond, R. (2010). I want it and I want it Now': Using a temporal discounting paradigm to examine predictors of consumer impulsivity. British Journal of Psychology, 101 (4), 751–776.

Dittmar, H., Beattie, J., & Friese, S. (1995). Gender identity and material symbols: Objects and decision considerations in impulse purchases. Journal of Economic Psychology, 16 (3), 491–511.

Dittmar, H., Halliwell, E., & Stirling, E. (2009). Understanding the impact of thin media models on Women’s body-focused affect: The roles of thin-ideal internalization and weight-related self-discrepancy activation in experimental exposure effects. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28 (1), 43–75.

Donovan, R. J., & Rossiter, J. R. (1982). Store atmosphere: An environmental psychology approach. Journal of Retailing, 58 (1), 34–57.

Eroglu, S. A., Machleit, K. A., & Davis, L. A. (2003). Empirical testing of a model of online store atmospherics and shopper responses. Psychology & Marketing, 20 (2), 139–150.

Fang, E., Palmatier, R. W., & Steenkamp, J. E. M. (2008). Effect of service transition strategies on firm value. Journal of Marketing, 72 (5), 1–14.

Field, A. P. (2001). Meta-analysis of correlation coefficients: A Monte Carlo comparison of fixed- and random-effects models. Psychological Methods, 6 , 161–180.

Finley, A. J., & Schemichel, B. J. (2018). Aftereffects of self-control on positive emotional reactivity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45 , 1011–1027. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218802836 .

Fishbach, A., & Labroo, A. A. (2007). Be better or be merry: How mood affects self-control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93 (2), 158–173.

Foxall, G. R. (2007). Explaining Consumer Choice . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Book Google Scholar

Foxall, G. R., & Greenley, G. E. (1999). Consumers' emotional responses to service environments. Journal of Business Research, 46 (2), 149–158.

Geyskens, I., Krishnan, R., Steenkamp, J. E. M., & Cunha, P. V. (2009). A review and evaluation of meta-analysis practices in management research. Journal of Management, 35 (2), 393–419.

Grewal, D., & Marmorstein, H. (1994). Market price variation, perceived price variation, and consumers' price search decisions for durable goods. Journal of Consumer Research, 21 (3), 453–460.

Grewal, D., Ahlbom, C., Beitelspacher, L. S., Noble, S. M., & Nordfalt, J. (2018a). In-store Mobile phone use and customer shopping behavior: Evidence from the field. Journal of Marketing., 82 (4), 102–126.

Grewal, D., Puccinelli, N., & Monroe, K. B. (2018b). Meta-analysis: Integrating accumulating knowledge. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1), 9–30.

Herabadi, A. G., Verplanken, B., & Van Knippenberg, A. (2009). Consumption experience of impulse buying in Indonesia: Emotional arousal and hedonistic considerations. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 12 (1), 20–31.

Hirschman, E. C., & Holbrook, M. B. (1982). Hedonic consumption: Emerging concepts, methods and propositions. Journal of Marketing, 46 (Summer), 92–101.

Hoch, S. J., & Loewenstein, G. F. (1991). Time-inconsistent preferences and consumer self-control. Journal of Consumer Research, 17 (4), 429–507.

Hofmann, W., Baumeister, R. F., Förster, G., & Vohs, K. D. (2012). Everyday temptations: An experience sampling study of desire, conflict, and self-control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102 (6), 1318–1325.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (2004). Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and Bias in research findings . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Jones, M. A., Reynolds, K. E., Weun, S., & Beatty, S. E. (2003). The product-specific nature of impulse buying tendency. Journal of Business Research, 56 (7), 505–511.

Kacen, J. J., & Lee, J. A. (2002). The influence of culture on consumer impulsive buying behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 12 (2), 163–176.

Kirca, A. H., Jayachandran, S., & Bearden, W. O. (2005). Market orientation: A meta-analytic review and assessment of its antecedents and impact on performance. Journal of Marketing, 69 (2), 24–41.

Kukar-Kinney, M., Ridgway, N. M., & Monroe, K. B. (2012). The role of Price in the behavior and purchase decisions of compulsive buyers. Journal of Retailing, 88 (1), 63–71.

Kwon, H. H., & Armstrong, K. L. (2002). Factors influencing impulse buying of sport team licensed merchandise. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 11 (3), 151–163.

Lin, Y. H., & Chen, C. F. (2013). Passengers' shopping motivations and commercial activities at airports–the moderating effects of time pressure and impulse buying tendency. Tourism Management, 36 , 426–434.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Liu, Y., Li, H., & Hu, F. (2013). Website attributes in urging online impulse purchase: An empirical investigation on consumer perceptions. Decision Support Systems, 55 (3), 829–837.

Lucas, M., & Koff, E. (2014). The role of impulsivity and of self-perceived attractiveness in impulse buying in women. Personality Individual Differences, 56 (January), 111–115.

Luo, X. (2005). How does shopping with others influence impulsive purchasing? Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15 (4), 288–294.

Mattila, A. S., & Wirtz, J. (2001). Congruency of scent and music as a driver of in-store evaluations and behavior. Journal of Retailing, 77 (2), 272–289.

Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology . Cambridge: MIT Press.

Mick, D. G., & Demoss, M. (1990). Self-gifts: Phenomenological insights from four contexts. Journal of Consumer Research, 17 (3), 322–332.

Mohan, G., Sivakumaran, B., & Sharma, P. (2013). Impact of store environment on impulse buying behavior. European Journal of Marketing, 47 (10), 1711–1732.

Morrin, M., & Chebat, J. C. (2005). Person-place congruency: The interactive effects of shopper style and atmospherics on consumer expenditures. Journal of Service Research, 8 (2), 181–191.

Mowen, J. C., & Spears, N. (1999). Understanding compulsive buying among college students: A hierarchical approach. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 8 (4), 407–430.

Muraven, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle?. Psychological Bulletin, 126 (2), 247–259.

O’Brien, S. (2018). Consumers Cough Up $5,400 a Year on Impulse Purchases. CNBC.com , February 23, Retrieved July 30, 2018 from https://www.cnbc.com/2018/02/23/consumers-cough-up-5400-a-year-on-impulse-purchases.html . Accessed 30 Jul 2018.

O'Guinn, T. C., & Faber, R. J. (1989). Compulsive buying: A phenomenological exploration. Journal of Consumer Research, 16 (2), 147–157.

Olsen, S. O., Tudoran, A. A., Honkanen, P., & Verplanken, B. (2016). Differences and similarities between impulse buying and variety seeking: A personality-based perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 33 (1), 36–47.

Orsingher, C., Valentini, S., & Angelis, M. (2009). A meta-analysis of satisfaction with complaint handling in services. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38 (2), 169–186.

Palmatier, R. W., Dant, R. P., & Grewal, D. (2007). A comparative longitudinal analysis of theoretical perspectives of Interorganizational relationship performance. Journal of Marketing, 71 (4), 172–194.

Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., & Hulland, J. (2018). Review articles: Purpose, process, and structure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1), 1–8.

Parboteeah, D. V., Valacich, J. S., & Wells, J. D. (2009). The influence of website characteristics on a Consumer's urge to buy impulsively. Information Systems Research, 20 (1), 60–78.

Park, E. J., Kim, E. Y., Funches, V. M., & Foxx, W. (2012). Apparel product attributes, web browsing, and E-impulse buying on shopping websites. Journal of Business Research, 65 (11), 1583–1589.

Peck, J., & Childers, T. L. (2006). If I touch it I have to have it: Individual and environmental influences on impulse purchasing. Journal of Business Research, 59 (6), 765–769.

Peterson, R. A., & Brown, S. P. (2005). On the use of Beta coefficients in meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90 (1), 175–181.

Pick, D., & Eisend, M. (2014). Buyers’ perceived switching costs and switching: A meta-analytic assessment of their antecedents. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42 (2), 186–204.

Punj, G. (2011). Impulse buying and variety seeking: Similarities and differences. Journal of Business Research, 64 (7), 745–748.

Ramanathan, S., & Menon, G. (2006). Time-varying effects of chronic hedonic goals on impulsive behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 43 (4), 628–641.

Roggeveen, A. L., Nordfalt, J., & Grewal, D. (2016). Do digital displays enhance sales? Role of retail format and message content. Journal of Retailing, 92 (1), 122–131.

Rook, D. W. (1987). The buying impulse. Journal of Consumer Research, 14 (2), 189–199.

Rook, D. W., & Fisher, R. J. (1995). Normative influences on impulsive buying behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 22 (3), 305–313.

Rook, D. W., & Gardner, M. P. (1993). In the mood: Impulsive Buyings’ antecedents. In J. Arnold-Costa & R. W. Belk (Eds.), Research in consumer behavior (pp. 1–28). Greenwich: JAI Press.

Rook, D. W., & Hoch, S. J. (1985). Consuming Impulses. In E. C. Hirschman & M. B. Holbrook (Eds.), Advances in consumer research (pp. 23–27). Chicago, IL: Association for Consumer Research, 23-27).

Rosenthal, R. (1979). The 'File drawer Problem' and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86 (3), 638–641.

Rostoks, L. (2003). Tapping into the shopper impulse. Canadian Grocer, 117 (October), 34–35.

Samaha, S. A., Beck, J. T., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). The role of culture in international relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 78 (5), 78–98.