An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.369; 2020

Food for Thought 2020

Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing, joseph firth.

1 Division of Psychology and Mental Health, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, Oxford Road, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK

2 NICM Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Westmead, Australia

James E Gangwisch

3 Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, USA

4 New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA

Alessandra Borsini

5 Section of Stress, Psychiatry and Immunology Laboratory, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, Department of Psychological Medicine, King’s College London, London, UK

Robyn E Wootton

6 School of Psychological Science, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

7 MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit, Oakfield House, Bristol, UK

8 NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

Emeran A Mayer

9 G Oppenheimer Center for Neurobiology of Stress and Resilience, UCLA Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

10 UCLA Microbiome Center, David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Poor nutrition may be a causal factor in the experience of low mood, and improving diet may help to protect not only the physical health but also the mental health of the population, say Joseph Firth and colleagues

Key messages

- Healthy eating patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet, are associated with better mental health than “unhealthy” eating patterns, such as the Western diet

- The effects of certain foods or dietary patterns on glycaemia, immune activation, and the gut microbiome may play a role in the relationships between food and mood

- More research is needed to understand the mechanisms that link food and mental wellbeing and determine how and when nutrition can be used to improve mental health

Depression and anxiety are the most common mental health conditions worldwide, making them a leading cause of disability. 1 Even beyond diagnosed conditions, subclinical symptoms of depression and anxiety affect the wellbeing and functioning of a large proportion of the population. 2 Therefore, new approaches to managing both clinically diagnosed and subclinical depression and anxiety are needed.

In recent years, the relationships between nutrition and mental health have gained considerable interest. Indeed, epidemiological research has observed that adherence to healthy or Mediterranean dietary patterns—high consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes; moderate consumption of poultry, eggs, and dairy products; and only occasional consumption of red meat—is associated with a reduced risk of depression. 3 However, the nature of these relations is complicated by the clear potential for reverse causality between diet and mental health ( fig 1 ). For example, alterations in food choices or preferences in response to our temporary psychological state—such as “comfort foods” in times of low mood, or changes in appetite from stress—are common human experiences. In addition, relationships between nutrition and longstanding mental illness are compounded by barriers to maintaining a healthy diet. These barriers disproportionality affect people with mental illness and include the financial and environmental determinants of health, and even the appetite inducing effects of psychiatric medications. 4

Hypothesised relationship between diet, physical health, and mental health. The dashed line is the focus of this article.

While acknowledging the complex, multidirectional nature of the relationships between diet and mental health ( fig 1 ), in this article we focus on the ways in which certain foods and dietary patterns could affect mental health.

Mood and carbohydrates

Consumption of highly refined carbohydrates can increase the risk of obesity and diabetes. 5 Glycaemic index is a relative ranking of carbohydrate in foods according to the speed at which they are digested, absorbed, metabolised, and ultimately affect blood glucose and insulin levels. As well as the physical health risks, diets with a high glycaemic index and load (eg, diets containing high amounts of refined carbohydrates and sugars) may also have a detrimental effect on psychological wellbeing; data from longitudinal research show an association between progressively higher dietary glycaemic index and the incidence of depressive symptoms. 6 Clinical studies have also shown potential causal effects of refined carbohydrates on mood; experimental exposure to diets with a high glycaemic load in controlled settings increases depressive symptoms in healthy volunteers, with a moderately large effect. 7

Although mood itself can affect our food choices, plausible mechanisms exist by which high consumption of processed carbohydrates could increase the risk of depression and anxiety—for example, through repeated and rapid increases and decreases in blood glucose. Measures of glycaemic index and glycaemic load can be used to estimate glycaemia and insulin demand in healthy individuals after eating. 8 Thus, high dietary glycaemic load, and the resultant compensatory responses, could lower plasma glucose to concentrations that trigger the secretion of autonomic counter-regulatory hormones such as cortisol, adrenaline, growth hormone, and glucagon. 5 9 The potential effects of this response on mood have been examined in experimental human research of stepped reductions in plasma glucose concentrations conducted under laboratory conditions through glucose perfusion. These findings showed that such counter-regulatory hormones may cause changes in anxiety, irritability, and hunger. 10 In addition, observational research has found that recurrent hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar) is associated with mood disorders. 9

The hypothesis that repeated and rapid increases and decreases in blood glucose explain how consumption of refined carbohydrate could affect psychological state appears to be a good fit given the relatively fast effect of diets with a high glycaemic index or load on depressive symptoms observed in human studies. 7 However, other processes may explain the observed relationships. For instance, diets with a high glycaemic index are a risk factor for diabetes, 5 which is often a comorbid condition with depression. 4 11 While the main models of disease pathophysiology in diabetes and mental illness are separate, common abnormalities in insulin resistance, brain volume, and neurocognitive performance in both conditions support the hypothesis that these conditions have overlapping pathophysiology. 12 Furthermore, the inflammatory response to foods with a high glycaemic index 13 raises the possibility that diets with a high glycaemic index are associated with symptoms of depression through the broader connections between mental health and immune activation.

Diet, immune activation, and depression

Studies have found that sustained adherence to Mediterranean dietary patterns can reduce markers of inflammation in humans. 14 On the other hand, high calorie meals rich in saturated fat appear to stimulate immune activation. 13 15 Indeed, the inflammatory effects of a diet high in calories and saturated fat have been proposed as one mechanism through which the Western diet may have detrimental effects on brain health, including cognitive decline, hippocampal dysfunction, and damage to the blood-brain barrier. 15 Since various mental health conditions, including mood disorders, have been linked to heightened inflammation, 16 this mechanism also presents a pathway through which poor diet could increase the risk of depression. This hypothesis is supported by observational studies which have shown that people with depression score significantly higher on measures of “dietary inflammation,” 3 17 characterised by a greater consumption of foods that are associated with inflammation (eg, trans fats and refined carbohydrates) and lower intakes of nutritional foods, which are thought to have anti-inflammatory properties (eg, omega-3 fats). However, the causal roles of dietary inflammation in mental health have not yet been established.

Nonetheless, randomised controlled trials of anti-inflammatory agents (eg, cytokine inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) have found that these agents can significantly reduce depressive symptoms. 18 Specific nutritional components (eg, polyphenols and polyunsaturated fats) and general dietary patterns (eg, consumption of a Mediterranean diet) may also have anti-inflammatory effects, 14 19 20 which raises the possibility that certain foods could relieve or prevent depressive symptoms associated with heightened inflammatory status. 21 A recent study provides preliminary support for this possibility. 20 The study shows that medications that stimulate inflammation typically induce depressive states in people treated, and that giving omega-3 fatty acids, which have anti-inflammatory properties, before the medication seems to prevent the onset of cytokine induced depression. 20

However, the complexity of the hypothesised three way relation between diet, inflammation, and depression is compounded by several important modifiers. For example, recent clinical research has observed that stressors experienced the previous day, or a personal history of major depressive disorders, may cancel out the beneficial effects of healthy food choices on inflammation and mood. 22 Furthermore, as heightened inflammation occurs in only some clinically depressed individuals, anti-inflammatory interventions may only benefit certain people characterised by an “inflammatory phenotype,” or those with comorbid inflammatory conditions. 18 Further interventional research is needed to establish if improvements in immune regulation, induced by diet, can reduce depressive symptoms in those affected by inflammatory conditions.

Brain, gut microbiome, and mood

A more recent explanation for the way in which our food may affect our mental wellbeing is the effect of dietary patterns on the gut microbiome—a broad term that refers to the trillions of microbial organisms, including bacteria, viruses, and archaea, living in the human gut. The gut microbiome interacts with the brain in bidirectional ways using neural, inflammatory, and hormonal signalling pathways. 23 The role of altered interactions between the brain and gut microbiome on mental health has been proposed on the basis of the following evidence: emotion-like behaviour in rodents changes with changes in the gut microbiome, 24 major depressive disorder in humans is associated with alterations of the gut microbiome, 25 and transfer of faecal gut microbiota from humans with depression into rodents appears to induce animal behaviours that are hypothesised to indicate depression-like states. 25 26 Such findings suggest a role of altered neuroactive microbial metabolites in depressive symptoms.

In addition to genetic factors and exposure to antibiotics, diet is a potentially modifiable determinant of the diversity, relative abundance, and functionality of the gut microbiome throughout life. For instance, the neurocognitive effects of the Western diet, and the possible mediating role of low grade systemic immune activation (as discussed above) may result from a compromised mucus layer with or without increased epithelial permeability. Such a decrease in the function of the gut barrier is sometimes referred to as a “leaky gut” and has been linked to an “unhealthy” gut microbiome resulting from a diet low in fibre and high in saturated fats, refined sugars, and artificial sweeteners. 15 23 27 Conversely, the consumption of a diet high in fibres, polyphenols, and unsaturated fatty acids (as found in a Mediterranean diet) can promote gut microbial taxa which can metabolise these food sources into anti-inflammatory metabolites, 15 28 such as short chain fatty acids, while lowering the production of secondary bile acids and p-cresol. Moreover, a recent study found that the ingestion of probiotics by healthy individuals, which theoretically target the gut microbiome, can alter the brain’s response to a task that requires emotional attention 29 and may even reduce symptoms of depression. 30 When viewed together, these studies provide promising evidence supporting a role of the gut microbiome in modulating processes that regulate emotion in the human brain. However, no causal relationship between specific microbes, or their metabolites, and complex human emotions has been established so far. Furthermore, whether changes to the gut microbiome induced by diet can affect depressive symptoms or clinical depressive disorders, and the time in which this could feasibly occur, remains to be shown.

Priorities and next steps

In moving forward within this active field of research, it is firstly important not to lose sight of the wood for the trees—that is, become too focused on the details and not pay attention to the bigger questions. Whereas discovering the anti-inflammatory properties of a single nutrient or uncovering the subtleties of interactions between the gut and the brain may shed new light on how food may influence mood, it is important not to neglect the existing knowledge on other ways diet may affect mental health. For example, the later consequences of a poor diet include obesity and diabetes, which have already been shown to be associated with poorer mental health. 11 31 32 33 A full discussion of the effect of these comorbidities is beyond the scope of our article (see fig 1 ), but it is important to acknowledge that developing public health initiatives that effectively tackle the established risk factors of physical and mental comorbidities is a priority for improving population health.

Further work is needed to improve our understanding of the complex pathways through which diet and nutrition can influence the brain. Such knowledge could lead to investigations of targeted, even personalised, interventions to improve mood, anxiety, or other symptoms through nutritional approaches. However, these possibilities are speculative at the moment, and more interventional research is needed to establish if, how, and when dietary interventions can be used to prevent mental illness or reduce symptoms in those living with such conditions. Of note, a recent large clinical trial found no significant benefits of a behavioural intervention promoting a Mediterranean diet for adults with subclinical depressive symptoms. 34 On the other hand, several recent smaller trials in individuals with current depression observed moderately large improvements from interventions based on the Mediterranean diet. 35 36 37 Such results, however, must be considered within the context of the effect of people’s expectations, particularly given that individuals’ beliefs about the quality of their food or diet may also have a marked effect on their sense of overall health and wellbeing. 38 Nonetheless, even aside from psychological effects, consideration of dietary factors within mental healthcare may help improve physical health outcomes, given the higher rates of cardiometabolic diseases observed in people with mental illness. 33

At the same time, it is important to be remember that the causes of mental illness are many and varied, and they will often present and persist independently of nutrition and diet. Thus, the increased understanding of potential connections between food and mental wellbeing should never be used to support automatic assumptions, or stigmatisation, about an individual’s dietary choices and their mental health. Indeed, such stigmatisation could be itself be a casual pathway to increasing the risk of poorer mental health. Nonetheless, a promising message for public health and clinical settings is emerging from the ongoing research. This message supports the idea that creating environments and developing measures that promote healthy, nutritious diets, while decreasing the consumption of highly processed and refined “junk” foods may provide benefits even beyond the well known effects on physical health, including improved psychological wellbeing.

Contributors and sources: JF has expertise in the interaction between physical and mental health, particularly the role of lifestyle and behavioural health factors in mental health promotion. JEG’s area of expertise is the study of the relationship between sleep duration, nutrition, psychiatric disorders, and cardiometabolic diseases. AB leads research investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of stress and inflammation on human hippocampal neurogenesis, and how nutritional components and their metabolites can prevent changes induced by those conditions. REW has expertise in genetic epidemiology approaches to examining casual relations between health behaviours and mental illness. EAM has expertise in brain and gut interactions and microbiome interactions. All authors contributed to, read, and approved the paper, and all the information was sourced from articles published in peer reviewed research journals. JF is the guarantor.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following: JF is supported by a University of Manchester Presidential Fellowship and a UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship and has received support from a NICM-Blackmores Institute Fellowship. JEG served on the medical advisory board on insomnia in the cardiovascular patient population for the drug company Eisai. AB has received research funding from Johnson & Johnson for research on depression and inflammation, the UK Medical Research Council, the European Commission Horizon 2020, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, and King’s College London. REW receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. EAM has served on the external advisory boards of Danone, Viome, Amare, Axial Biotherapeutics, Pendulum, Ubiome, Bloom Science, Mahana Therapeutics, and APC Microbiome Ireland, and he receives royalties from Harper & Collins for his book The Mind Gut Connection. He is supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the US Department of Defense. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the organisations above.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of series commissioned by The BMJ. Open access fees are paid by Swiss Re, which had no input into the commissioning or peer review of the articles. T he BMJ thanks the series advisers, Nita Forouhi, Dariush Mozaffarian, and Anna Lartey for valuable advice and guiding selection of topics in the series.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Food and mood: how do...

Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing?

Read our food for thought 2020 collection.

- Related content

- Peer review

This article has a correction. Please see:

- Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing? - November 09, 2020

- Joseph Firth , research fellow 1 2 ,

- James E Gangwisch , assistant professor 3 4 ,

- Alessandra Borsini , researcher 5 ,

- Robyn E Wootton , researcher 6 7 8 ,

- Emeran A Mayer , professor 9 10

- 1 Division of Psychology and Mental Health, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, Oxford Road, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK

- 2 NICM Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Westmead, Australia

- 3 Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, USA

- 4 New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA

- 5 Section of Stress, Psychiatry and Immunology Laboratory, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, Department of Psychological Medicine, King’s College London, London, UK

- 6 School of Psychological Science, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

- 7 MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit, Oakfield House, Bristol, UK

- 8 NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

- 9 G Oppenheimer Center for Neurobiology of Stress and Resilience, UCLA Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

- 10 UCLA Microbiome Center, David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

- Correspondence to: J Firth joseph.firth{at}manchester.ac.uk

Poor nutrition may be a causal factor in the experience of low mood, and improving diet may help to protect not only the physical health but also the mental health of the population, say Joseph Firth and colleagues

Key messages

Healthy eating patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet, are associated with better mental health than “unhealthy” eating patterns, such as the Western diet

The effects of certain foods or dietary patterns on glycaemia, immune activation, and the gut microbiome may play a role in the relationships between food and mood

More research is needed to understand the mechanisms that link food and mental wellbeing and determine how and when nutrition can be used to improve mental health

Depression and anxiety are the most common mental health conditions worldwide, making them a leading cause of disability. 1 Even beyond diagnosed conditions, subclinical symptoms of depression and anxiety affect the wellbeing and functioning of a large proportion of the population. 2 Therefore, new approaches to managing both clinically diagnosed and subclinical depression and anxiety are needed.

In recent years, the relationships between nutrition and mental health have gained considerable interest. Indeed, epidemiological research has observed that adherence to healthy or Mediterranean dietary patterns—high consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes; moderate consumption of poultry, eggs, and dairy products; and only occasional consumption of red meat—is associated with a reduced risk of depression. 3 However, the nature of these relations is complicated by the clear potential for reverse causality between diet and mental health ( fig 1 ). For example, alterations in food choices or preferences in response to our temporary psychological state—such as “comfort foods” in times of low mood, or changes in appetite from stress—are common human experiences. In addition, relationships between nutrition and longstanding mental illness are compounded by barriers to maintaining a healthy diet. These barriers disproportionality affect people with mental illness and include the financial and environmental determinants of health, and even the appetite inducing effects of psychiatric medications. 4

Hypothesised relationship between diet, physical health, and mental health. The dashed line is the focus of this article.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

While acknowledging the complex, multidirectional nature of the relationships between diet and mental health ( fig 1 ), in this article we focus on the ways in which certain foods and dietary patterns could affect mental health.

Mood and carbohydrates

Consumption of highly refined carbohydrates can increase the risk of obesity and diabetes. 5 Glycaemic index is a relative ranking of carbohydrate in foods according to the speed at which they are digested, absorbed, metabolised, and ultimately affect blood glucose and insulin levels. As well as the physical health risks, diets with a high glycaemic index and load (eg, diets containing high amounts of refined carbohydrates and sugars) may also have a detrimental effect on psychological wellbeing; data from longitudinal research show an association between progressively higher dietary glycaemic index and the incidence of depressive symptoms. 6 Clinical studies have also shown potential causal effects of refined carbohydrates on mood; experimental exposure to diets with a high glycaemic load in controlled settings increases depressive symptoms in healthy volunteers, with a moderately large effect. 7

Although mood itself can affect our food choices, plausible mechanisms exist by which high consumption of processed carbohydrates could increase the risk of depression and anxiety—for example, through repeated and rapid increases and decreases in blood glucose. Measures of glycaemic index and glycaemic load can be used to estimate glycaemia and insulin demand in healthy individuals after eating. 8 Thus, high dietary glycaemic load, and the resultant compensatory responses, could lower plasma glucose to concentrations that trigger the secretion of autonomic counter-regulatory hormones such as cortisol, adrenaline, growth hormone, and glucagon. 5 9 The potential effects of this response on mood have been examined in experimental human research of stepped reductions in plasma glucose concentrations conducted under laboratory conditions through glucose perfusion. These findings showed that such counter-regulatory hormones may cause changes in anxiety, irritability, and hunger. 10 In addition, observational research has found that recurrent hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar) is associated with mood disorders. 9

The hypothesis that repeated and rapid increases and decreases in blood glucose explain how consumption of refined carbohydrate could affect psychological state appears to be a good fit given the relatively fast effect of diets with a high glycaemic index or load on depressive symptoms observed in human studies. 7 However, other processes may explain the observed relationships. For instance, diets with a high glycaemic index are a risk factor for diabetes, 5 which is often a comorbid condition with depression. 4 11 While the main models of disease pathophysiology in diabetes and mental illness are separate, common abnormalities in insulin resistance, brain volume, and neurocognitive performance in both conditions support the hypothesis that these conditions have overlapping pathophysiology. 12 Furthermore, the inflammatory response to foods with a high glycaemic index 13 raises the possibility that diets with a high glycaemic index are associated with symptoms of depression through the broader connections between mental health and immune activation.

Diet, immune activation, and depression

Studies have found that sustained adherence to Mediterranean dietary patterns can reduce markers of inflammation in humans. 14 On the other hand, high calorie meals rich in saturated fat appear to stimulate immune activation. 13 15 Indeed, the inflammatory effects of a diet high in calories and saturated fat have been proposed as one mechanism through which the Western diet may have detrimental effects on brain health, including cognitive decline, hippocampal dysfunction, and damage to the blood-brain barrier. 15 Since various mental health conditions, including mood disorders, have been linked to heightened inflammation, 16 this mechanism also presents a pathway through which poor diet could increase the risk of depression. This hypothesis is supported by observational studies which have shown that people with depression score significantly higher on measures of “dietary inflammation,” 3 17 characterised by a greater consumption of foods that are associated with inflammation (eg, trans fats and refined carbohydrates) and lower intakes of nutritional foods, which are thought to have anti-inflammatory properties (eg, omega-3 fats). However, the causal roles of dietary inflammation in mental health have not yet been established.

Nonetheless, randomised controlled trials of anti-inflammatory agents (eg, cytokine inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) have found that these agents can significantly reduce depressive symptoms. 18 Specific nutritional components (eg, polyphenols and polyunsaturated fats) and general dietary patterns (eg, consumption of a Mediterranean diet) may also have anti-inflammatory effects, 14 19 20 which raises the possibility that certain foods could relieve or prevent depressive symptoms associated with heightened inflammatory status. 21 A recent study provides preliminary support for this possibility. 20 The study shows that medications that stimulate inflammation typically induce depressive states in people treated, and that giving omega-3 fatty acids, which have anti-inflammatory properties, before the medication seems to prevent the onset of cytokine induced depression. 20

However, the complexity of the hypothesised three way relation between diet, inflammation, and depression is compounded by several important modifiers. For example, recent clinical research has observed that stressors experienced the previous day, or a personal history of major depressive disorders, may cancel out the beneficial effects of healthy food choices on inflammation and mood. 22 Furthermore, as heightened inflammation occurs in only some clinically depressed individuals, anti-inflammatory interventions may only benefit certain people characterised by an “inflammatory phenotype,” or those with comorbid inflammatory conditions. 18 Further interventional research is needed to establish if improvements in immune regulation, induced by diet, can reduce depressive symptoms in those affected by inflammatory conditions.

Brain, gut microbiome, and mood

A more recent explanation for the way in which our food may affect our mental wellbeing is the effect of dietary patterns on the gut microbiome—a broad term that refers to the trillions of microbial organisms, including bacteria, viruses, and archaea, living in the human gut. The gut microbiome interacts with the brain in bidirectional ways using neural, inflammatory, and hormonal signalling pathways. 23 The role of altered interactions between the brain and gut microbiome on mental health has been proposed on the basis of the following evidence: emotion-like behaviour in rodents changes with changes in the gut microbiome, 24 major depressive disorder in humans is associated with alterations of the gut microbiome, 25 and transfer of faecal gut microbiota from humans with depression into rodents appears to induce animal behaviours that are hypothesised to indicate depression-like states. 25 26 Such findings suggest a role of altered neuroactive microbial metabolites in depressive symptoms.

In addition to genetic factors and exposure to antibiotics, diet is a potentially modifiable determinant of the diversity, relative abundance, and functionality of the gut microbiome throughout life. For instance, the neurocognitive effects of the Western diet, and the possible mediating role of low grade systemic immune activation (as discussed above) may result from a compromised mucus layer with or without increased epithelial permeability. Such a decrease in the function of the gut barrier is sometimes referred to as a “leaky gut” and has been linked to an “unhealthy” gut microbiome resulting from a diet low in fibre and high in saturated fats, refined sugars, and artificial sweeteners. 15 23 27 Conversely, the consumption of a diet high in fibres, polyphenols, and unsaturated fatty acids (as found in a Mediterranean diet) can promote gut microbial taxa which can metabolise these food sources into anti-inflammatory metabolites, 15 28 such as short chain fatty acids, while lowering the production of secondary bile acids and p-cresol. Moreover, a recent study found that the ingestion of probiotics by healthy individuals, which theoretically target the gut microbiome, can alter the brain’s response to a task that requires emotional attention 29 and may even reduce symptoms of depression. 30 When viewed together, these studies provide promising evidence supporting a role of the gut microbiome in modulating processes that regulate emotion in the human brain. However, no causal relationship between specific microbes, or their metabolites, and complex human emotions has been established so far. Furthermore, whether changes to the gut microbiome induced by diet can affect depressive symptoms or clinical depressive disorders, and the time in which this could feasibly occur, remains to be shown.

Priorities and next steps

In moving forward within this active field of research, it is firstly important not to lose sight of the wood for the trees—that is, become too focused on the details and not pay attention to the bigger questions. Whereas discovering the anti-inflammatory properties of a single nutrient or uncovering the subtleties of interactions between the gut and the brain may shed new light on how food may influence mood, it is important not to neglect the existing knowledge on other ways diet may affect mental health. For example, the later consequences of a poor diet include obesity and diabetes, which have already been shown to be associated with poorer mental health. 11 31 32 33 A full discussion of the effect of these comorbidities is beyond the scope of our article (see fig 1 ), but it is important to acknowledge that developing public health initiatives that effectively tackle the established risk factors of physical and mental comorbidities is a priority for improving population health.

Further work is needed to improve our understanding of the complex pathways through which diet and nutrition can influence the brain. Such knowledge could lead to investigations of targeted, even personalised, interventions to improve mood, anxiety, or other symptoms through nutritional approaches. However, these possibilities are speculative at the moment, and more interventional research is needed to establish if, how, and when dietary interventions can be used to prevent mental illness or reduce symptoms in those living with such conditions. Of note, a recent large clinical trial found no significant benefits of a behavioural intervention promoting a Mediterranean diet for adults with subclinical depressive symptoms. 34 On the other hand, several recent smaller trials in individuals with current depression observed moderately large improvements from interventions based on the Mediterranean diet. 35 36 37 Such results, however, must be considered within the context of the effect of people’s expectations, particularly given that individuals’ beliefs about the quality of their food or diet may also have a marked effect on their sense of overall health and wellbeing. 38 Nonetheless, even aside from psychological effects, consideration of dietary factors within mental healthcare may help improve physical health outcomes, given the higher rates of cardiometabolic diseases observed in people with mental illness. 33

At the same time, it is important to be remember that the causes of mental illness are many and varied, and they will often present and persist independently of nutrition and diet. Thus, the increased understanding of potential connections between food and mental wellbeing should never be used to support automatic assumptions, or stigmatisation, about an individual’s dietary choices and their mental health. Indeed, such stigmatisation could be itself be a casual pathway to increasing the risk of poorer mental health. Nonetheless, a promising message for public health and clinical settings is emerging from the ongoing research. This message supports the idea that creating environments and developing measures that promote healthy, nutritious diets, while decreasing the consumption of highly processed and refined “junk” foods may provide benefits even beyond the well known effects on physical health, including improved psychological wellbeing.

Contributors and sources: JF has expertise in the interaction between physical and mental health, particularly the role of lifestyle and behavioural health factors in mental health promotion. JEG’s area of expertise is the study of the relationship between sleep duration, nutrition, psychiatric disorders, and cardiometabolic diseases. AB leads research investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of stress and inflammation on human hippocampal neurogenesis, and how nutritional components and their metabolites can prevent changes induced by those conditions. REW has expertise in genetic epidemiology approaches to examining casual relations between health behaviours and mental illness. EAM has expertise in brain and gut interactions and microbiome interactions. All authors contributed to, read, and approved the paper, and all the information was sourced from articles published in peer reviewed research journals. JF is the guarantor.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following: JF is supported by a University of Manchester Presidential Fellowship and a UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship and has received support from a NICM-Blackmores Institute Fellowship. JEG served on the medical advisory board on insomnia in the cardiovascular patient population for the drug company Eisai. AB has received research funding from Johnson & Johnson for research on depression and inflammation, the UK Medical Research Council, the European Commission Horizon 2020, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, and King’s College London. REW receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. EAM has served on the external advisory boards of Danone, Viome, Amare, Axial Biotherapeutics, Pendulum, Ubiome, Bloom Science, Mahana Therapeutics, and APC Microbiome Ireland, and he receives royalties from Harper & Collins for his book The Mind Gut Connection. He is supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the US Department of Defense. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the organisations above.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of series commissioned by The BMJ. Open access fees are paid by Swiss Re, which had no input into the commissioning or peer review of the articles. T he BMJ thanks the series advisers, Nita Forouhi, Dariush Mozaffarian, and Anna Lartey for valuable advice and guiding selection of topics in the series.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

- Friedrich MJ

- Johnson J ,

- Weissman MM ,

- Lassale C ,

- Baghdadli A ,

- Siddiqi N ,

- Koyanagi A ,

- Gangwisch JE ,

- Salari-Moghaddam A ,

- Larijani B ,

- Esmaillzadeh A

- de Jong V ,

- Atkinson F ,

- Brand-Miller JC

- Seaquist ER ,

- Anderson J ,

- American Diabetes Association ,

- Endocrine Society

- Towler DA ,

- Havlin CE ,

- McIntyre RS ,

- Nguyen HT ,

- O’Keefe JH ,

- Gheewala NM ,

- Kastorini C-M ,

- Milionis HJ ,

- Esposito K ,

- Giugliano D ,

- Goudevenos JA ,

- Panagiotakos DB

- Teasdale SB ,

- Köhler-Forsberg O ,

- N Lydholm C ,

- Hjorthøj C ,

- Nordentoft M ,

- Yahfoufi N ,

- Borsini A ,

- Horowitz MA ,

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK ,

- Fagundes CP ,

- Andridge R ,

- Osadchiy V ,

- Martin CR ,

- O’Brien C ,

- Sonnenburg ED ,

- Sonnenburg JL

- Rampelli S ,

- Jeffery IB ,

- Tillisch K ,

- Kilpatrick L ,

- Walsh RFL ,

- Wootton RE ,

- Millard LAC ,

- Jebeile H ,

- Garnett SP ,

- Paxton SJ ,

- Brouwer IA ,

- MooDFOOD Prevention Trial Investigators

- Francis HM ,

- Stevenson RJ ,

- Chambers JR ,

- Parletta N ,

- Zarnowiecki D ,

- Fischler C ,

- Sarubin A ,

- Wrzesniewski A

- Harrington D ,

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 20 November 2023

The triple burden of malnutrition

Nature Food volume 4 , page 925 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2647 Accesses

1 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Today’s nutrition crisis is a manifestation of the broader malfunctioning of our global food system. The specific factors linking the two warrant further investigation.

The world is facing an unprecedented crisis in which overnutrition (overweight and obesity), undernutrition (stunting, wasting and underweight) and micronutrient deficiencies (often referred to as ‘hidden hunger’) coexist within the same population. This triple burden of malnutrition is a major public health challenge. The numbers speak for themselves: 51% of the world’s population over five years of age is predicted to be obese or overweight by 2035 if the status quo is maintained while, paradoxically, one in five children under the age of five years is stunted.

Connecting overnutrition, undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies is the food system’s inability to provide equitable access to healthy diets for all. A recent analysis of anthropometric and demographic data from 55 low- and middle-income countries has shown that economic globalization is associated with the simultaneous occurrence of overnutrition and undernutrition, particularly among the poorest households of poorer countries (Seferidi, P. et al., Lancet Glob. Health 10 , E482–E490; 2022). Factors such as non-resilient food supply chains, persistent food loss and waste, economic crises, conflicts and extreme weather events pose additional threats. At the same time, the increasing accessibility of ultra-processed foods at lower prices than processed or unprocessed foods widens the gap in access to a healthy diet between high-income and low-income individuals.

Scientific evidence on the above factors and their interplay is key to support food system change towards ending malnutrition in all its forms. This issue of Nature Food features five primary research articles that aim to contribute to this goal.

Fadnes et al. use prospective population-based cohort data to show that sustained dietary changes can increase life expectancy by up to 10 years. The study reveals that the largest gains are associated with increased consumption of whole grains, nuts and fruits and reduced consumption of processed meats and sugar-sweetened beverages.

While these are considerable health gains, implementing dietary changes at the population level remains a challenge, given that the determinants of food choice are multifactorial — including, among others, culture, religion, personal preferences and economics (G. Leng et al., Proc. Nutr. Soc . 76 , 316–327; 2017). Recognizing that, in this issue, Grummon et al. propose an approach based on simple and actionable dietary substitutions that are more likely to be incorporated into people’s daily habits and benefit the health of the global population.

The responsibility for malnutrition lies on individual as much as collective choices. Relying solely on the former, without due consideration of what needs to be transformed in the food environment, might constrain progress towards better diets. Effective policies that make healthy food and water universally accessible while disincentivizing the consumption of unhealthy foods are essential to address these concerns on a global scale. A systematic scoping review by Alvarado et al. in this issue summarizes existing evidence on sugar-sweetened beverage taxation, an important contributor to overweight and obesity.

In addition to the obesity epidemic, micronutrient deficiencies of minerals (iodine, zinc and iron) and/or vitamins (vitamin A, vitamin B 12 and folate) have health consequences throughout the life cycle and not just in children. Based on a production–consumption–nutrition model, Wang et al. show that the food domestically available for consumption is insufficient to meet people’s needs for 9 different micronutrients in more than half of the 156 countries studied.

Finally, although biofortification of staple crops is a necessary strategy to increase accessibility to nutritious food, the latter can’t be achieved without ensuring the retention of micronutrients in food at the point of consumption. Huey et al. present an online interactive micronutrient retention dashboard that provides an overview of the retention of provitamin A, iron and zinc in food across crop processing methods. This new resource will benefit households, regulatory entities and implementers of biofortification programmes.

We hope you enjoy reading!

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

The triple burden of malnutrition. Nat Food 4 , 925 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00886-8

Download citation

Published : 20 November 2023

Issue Date : November 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-023-00886-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Heart-Healthy Living

- High Blood Pressure

- Sickle Cell Disease

- Sleep Apnea

- Information & Resources on COVID-19

- The Heart Truth®

- Learn More Breathe Better®

- Blood Diseases and Disorders Education Program

- Publications and Resources

- Blood Disorders and Blood Safety

- Sleep Science and Sleep Disorders

- Lung Diseases

- Health Disparities and Inequities

- Heart and Vascular Diseases

- Precision Medicine Activities

- Obesity, Nutrition, and Physical Activity

- Population and Epidemiology Studies

- Women’s Health

- Research Topics

- Clinical Trials

- All Science A-Z

- Grants and Training Home

- Policies and Guidelines

- Funding Opportunities and Contacts

- Training and Career Development

- Email Alerts

- NHLBI in the Press

- Research Features

- Past Events

- Upcoming Events

- Mission and Strategic Vision

- Divisions, Offices and Centers

- Advisory Committees

- Budget and Legislative Information

- Jobs and Working at the NHLBI

- Contact and FAQs

- NIH Sleep Research Plan

- < Back To Home

Americans poor diet drives $50 billion a year in health care costs

An #NHLBI-funded study put a price tag on American's bad eating habits: $50 billion a year in health care costs, attributable to cardiometabolic diseases such as heart disease, stroke and type 2 diabetes. The research, reported in the journal PLoS Medicine , sought to zero in on the national health care costs of unhealthy diet habits, which are known to account for up to 45% of all cardiometabolic deaths.

The researchers examined the impact of 10 food groups - fruits, vegetables, nuts/seeds, whole grains, unprocessed red meats, processed meats, sugar-sweetened beverages, polyunsaturated fats, seafood omega-3 fats and sodium - and found that almost 20% of heart disease, stroke and diabetes costs are due to poor diet.

Three dietary factors contributed most to these costs: consumption of processed meats, low consumption of nuts/seeds, and low consumption of seafoods containing omega-3 fats.

Media Coverage

- Health Care Costs Of Unhealthy American Diet? At Least $50B A Year, Study Estimates

- Unhealthy Eating Habits Cost U.S. $50 Billion a Year: Study

- Suboptimal Diet May Drive $50 Billion in Cardiometabolic Costs

- Better diets could save billions in U.S. health care costs

- Unhealthy eating costs $50B a year in health care costs

- Poor Diet Contributes Substantially to Cardiometabolic Disease Costs

- Healthy Diet Could Save $50B in Health Care Costs

- Cardiometabolic disease costs associated with suboptimal diet in the United States: A cost analysis based on a microsimulation model

Poor Nutrition

Measure Breastfeeding Practices and Eating Patterns

Support breastfeeding in the hospital and community, offer healthier food options in early care and education facilities and schools, offer healthier food options in the workplace, improve access to healthy foods in states and communities, support lifestyle change programs to reduce obesity and type 2 diabetes risk.

Good nutrition is essential to keeping current and future generations healthy across the lifespan. A healthy diet helps children grow and develop properly and reduces their risk of chronic diseases. Adults who eat a healthy diet live longer and have a lower risk of obesity, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers. Healthy eating can help people with chronic diseases manage these conditions and avoid complications.

However, when healthy options are not available, people may settle for foods that are higher in calories and lower in nutritional value. People in low-income communities and some racial and ethnic groups often lack access to convenient places that offer affordable, healthier foods.

Most people in the United States don’t eat a healthy diet and consume too much sodium, saturated fat, and sugar, increasing their risk of chronic diseases. For example, fewer than 1 in 10 adolescents and adults eat enough fruits or vegetables. In addition, 6 in 10 young people aged 2 to 19 years and 5 in 10 adults consume at least one sugary drink on any given day.

CDC supports breastfeeding and works to improve access to healthier food and drink choices in settings such as early care and education facilities, schools, worksites, and communities.

In the United States:

3 IN 4 INFANTS

are not exclusively breastfed for 6 months.

9 IN 10 AMERICANS

consume too much sodium.

1 in 6 PREGNANT WOMEN

have iron levels that are too low.

NEARLY $173 BILLION

a year is spent on health care for obesity.

The Harmful Effects of Poor Nutrition

Overweight and obesity.

Eating a healthy diet, along with getting enough physical activity and sleep, can help children grow up healthy and prevent overweight and obesity. In the United States, 20% of young people aged 2 to 19 years and 42% of adults have obesity, which can put them at risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers.

Heart Disease and Stroke

Two of the leading causes of heart disease and stroke are high blood pressure and high blood cholesterol. Consuming too much sodium can increase blood pressure and the risk for heart disease and stroke . Current guidelines recommend getting less than 2,300 mg a day, but Americans consume more than 3,400 mg a day on average.

Over 70% of the sodium that Americans eat comes from packaged, processed, store-bought, and restaurant foods. Eating foods low in saturated fats and high in fiber and increasing access to low-sodium foods, along with regular physical activity, can help prevent high blood cholesterol and high blood pressure.

Type 2 Diabetes

People who are overweight or have obesity are at increased risk of type 2 diabetes compared to those at a healthybecause, over time, their bodies become less able to use the insulin they make. Of US adults, 96 million—more than 1 in 3—have prediabetes , and more than 8 in 10 of them don’t know they have it. Although the rate of new cases has decreased in recent years, the number of adults with diagnosed diabetes has nearly doubled in the last 2 decades as the US population has increased, aged, and become more overweight.

An unhealthy diet can increase the risk of some cancers. Consuming unhealthy food and beverages, such as sugar-sweetened beverages and highly processed food, can lead to weight gain, obesity and other chronic conditions that put people at higher risk of at least 13 types of cancer, including endometrial (uterine) cancer, breast cancer in postmenopausal women, and colorectal cancer. The risk of colorectal cancer is also associated with eating red and processed meat.

CDC’s Work to Promote Good Nutrition

CDC’s Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity uses national and state surveys to track breastfeeding rates and eating patterns across the country, including fruit, vegetable, and added sugar consumption. The division also reports data on nutrition policies and practices for each state. Data from these surveys are used to understand trends in nutrition and differences between population groups.

CDC partners use this information to help support breastfeeding and encourage healthy eating where people live, learn, work, and play, especially for populations at highest risk of chronic disease.

Breastfeeding is the best source of nutrition for most infants. It can reduce the risk of some short-term health conditions for infants and long-term health conditions for infants and mothers. Maternity care practices in the first hours and days after birth can influence whether and how long infants are breastfed.

CDC funds programs that help hospitals use maternity care practices that support breastfeeding . These programs have helped increase the percentage of infants born in hospitals that implement recommended practices 1. CDC also works with partners to support programs designed to improve continuity of care and community support for breastfeeding mothers.

Nearly 56 million US children spend time in early care and education (ECE) facilities or public schools. These settings can directly influence what children eat and drink and how active they are—and build a foundation for healthy habits.

CDC is helping our nation’s children grow up healthy and strong by:

- Creating resources to help partners improve obesity prevention programs and use nutrition standards.

- Investing in training and learning networks that help child care providers and state and local child care leaders meet standards and use and share best practices .

- Providing technical assistance, such as training school staff how to buy, prepare, and serve fruits and vegetables or teach children how to grow and prepare fruits and vegetables.

The CDC Healthy Schools program works with states, school systems, communities, and national partners to promote good nutrition . These efforts include publishing guidelines and tips on how schools and parents can model healthy behaviors and offer healthier school meals, smart snacks , and water access.

CDC also works with national groups to increase the number of salad bars in schools. As of 2021, the Salad Bars to School program has delivered almost 6,000 salad bars to schools across the nation, giving over 2.9 million children and school staff better access to fruits and vegetables.

Millions of US adults buy foods and drinks while at work. CDC develops and promotes food service guidelines that encourage employers and vendors to increase healthy food options for employees. CDC-funded programs are working to make healthy foods and drinks (including water) more available in cafeterias, snack shops, and vending machines. CDC also partners with states to help employers comply with the federal lactation accommodation law and provide breastfeeding mothers with places to pump and store breast milk, flexible work hours, and maternity leave benefits.

People living in low-income urban neighborhoods, rural areas, and tribal communities often have little access to affordable, healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables. CDC’s State Physical Activity and Nutrition Program , High Obesity Program , and Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health program fund states and communities to improve food systems in these areas through food hubs, local stores, farmers’ markets, and bodegas.

These programs, which also involve food vendors and distributors, help increase the variety and number of healthier foods and drinks available and help promote and market these items to customers.

CDC’s National Diabetes Prevention Program (National DPP) is a partnership of public and private organizations working to build a nationwide delivery system for a lifestyle change program proven to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in adults with prediabetes. Participants in the National DPP lifestyle change program learn to make healthy food choices, be more physically active, and find ways to cope with stress. These changes can cut their risk of developing type 2 diabetes by as much as 58% (71% for those over 60).

Social_govd

Get Email Updates

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Open access

- Published: 08 September 2023

Nutrition interventions to address nutritional problems in HIV-positive patients: translating knowledge into practice

- Leila Rezazadeh 1 ,

- Alireza Ostadrahimi 2 ,

- Helda Tutunchi 3 ,

- Mohammad Naemi Kermanshahi 4 &

- Samira Pourmoradian 5

Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition volume 42 , Article number: 94 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2639 Accesses

1 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and malnutrition negatively reinforce each other. Malnutrition leads to further immune deficiency and accelerates disease progression. The present overview aimed to investigate the current knowledge from review articles on the role of nutrition interventions as well as food and nutrition policies on HIV-related outcomes in adults to present future strategies for strengthening food and nutrition response to HIV.

We searched PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Embase, ProQuest, and Ovid databases using the relevant keywords. The search was limited to studies published in English until April 2022. All types of reviews studies (systematic review, narrative review, and other types of review studies) which evaluated the impact of nutritional program/interventions on HIV progression were included.

Although nutrition programs in HIV care have resulted in improvements in nutritional symptoms and increase the quality life of HIV patients, these programs should evaluate the nutritional health of HIV-infected patients in a way that can be sustainable in the long term. In additions, demographic, clinical, and nutritional, social characteristics influence nutritional outcomes, which provide potential opportunities for future research.

Nutrition assessment, education and counseling, and food supplements where necessary should be an integral part of HIV treatment programs.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a serious communicable disease characterized by immunodeficiency and other complications that increase mortality rate in these patients. In 2020, it was estimated that the people living with HIV were 37.7 million worldwide, and 1.5 million people became newly infected with HIV [ 1 ]. According to the World Health Organization, HIV-related deaths were estimated about 630,000 cases by 2022. The prevalence of malnutrition (undernutrition) in HIV patients in some African countries is over 25% [ 2 ].

HIV is known by immune system suppression which increases energy requirement to combat infection in undernourished HIV patients, leading to further nutritional problems [ 3 , 4 ]. Malnutrition is an important health issue in patients living with HIV. Malnutrition leads to physiological, psychological, and functional disorders. In addition, malnutrition contributes to further immune deficiency and accelerates disease progression. The underlying causes of malnutrition in HIV-infected person are related to reduced food intake, poor absorption, changes in metabolism, chronic infections, and illnesses [ 5 ]. Adequate nutrition, which provides sufficient calories by macronutrients (proteins, carbohydrates and fats) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals), is important to increase resistance to infection, maintain nutritional status of patients, help to delay the progression of HIV, and improve quality of life [ 4 , 6 , 7 ].

In developing countries, poor nutrition status and food insecurity increase individuals’ susceptibility to infectious diseases, as well as viral load, sexual, and vertical transmission of HIV [ 8 ]. Nutrition interventions including supplementation with macro- and micronutrients, nutrition education, or counseling and food assistance programs are essential for HIV-positive persons to improve nutrient intake and reduce viral load by enhancing immunity [ 9 , 10 , 11 ].

To date, several review and systematic review studies have evaluated the effectiveness of such interventions on nutritional status of HIV. Considering sociodemographic, clinical and nutritional characteristics of various populations can influence the nutritional outcomes that provide potential opportunities for improvement in future research and programs. As far as we know, there is no overview to summarize the results of these review studies. Therefore, the present overview aimed to investigate the current knowledge from review articles on the role of nutrition interventions as well as food and nutrition policies on HIV-related outcomes in adults to present future strategies for strengthening food and nutrition response to HIV.

Material and methods

For the purposes of this overview, we searched PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Embase, ProQuest, and Ovid from 2000/01/01 until 2022/04/30. We developed and performed the literature search (MN, LR).

Only publications with English language were included.

Search strategy included combinations of the following terms:

“HIV” OR “human immunodeficiency virus*” OR “HIV” OR “People Living with HIV” OR “PLWHIV” OR “PLHIV” OR “HIV-positive” OR” HIV positive” AND “Nutrition program” OR “Nutritional intervention” OR “Nutrition education” OR “Micronutrient supplementation” OR “Macronutrient supplementation” OR “Ready to use Therapeutic food” OR “complementary therapy” OR “food assistance program”.

Gray literature (e.g., conference papers, theses, interviews, protocols, comments, and short communications) was obtained through Google searches and Elsevier (first 20 pages of results). Apart from electronic search, manual search of the reference lists of the eligible papers and relevant review articles were conducted to avoid missing relevant studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two of the authors (HT and SP) screened the title and abstract of all studies found in the systematic search to identify studies that met our criteria for inclusion in the present study. Systematic review which evaluated the impact of nutritional program/interventions on HIV progression was included. However, studies which examined nutrition intervention on children with HIV and also pregnant and lactation women were excluded.

Quality assessment of included reviews

Two authors (OA and LR) assessed the quality of included SRs using A Measurement Tool to Checklist Assess Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR 2). AMSTAR2 is a practical appraisal tool for SRs performed on randomized and/or nonrandomized studies of healthcare interventions. It contains16 domains. Each question was answered with “yes,” “no,” “cannot answer,” or “not applicable.” According to the answers, only the “yes” answer counted as a point in the total score for the assessed study. Thus, the meta-analyses with at least 80% of the items were categorized as high quality and those SRs between 40 and 80% scores were considered as moderate quality, and those with < 40% of the items were satisfied as low quality [ 12 ].

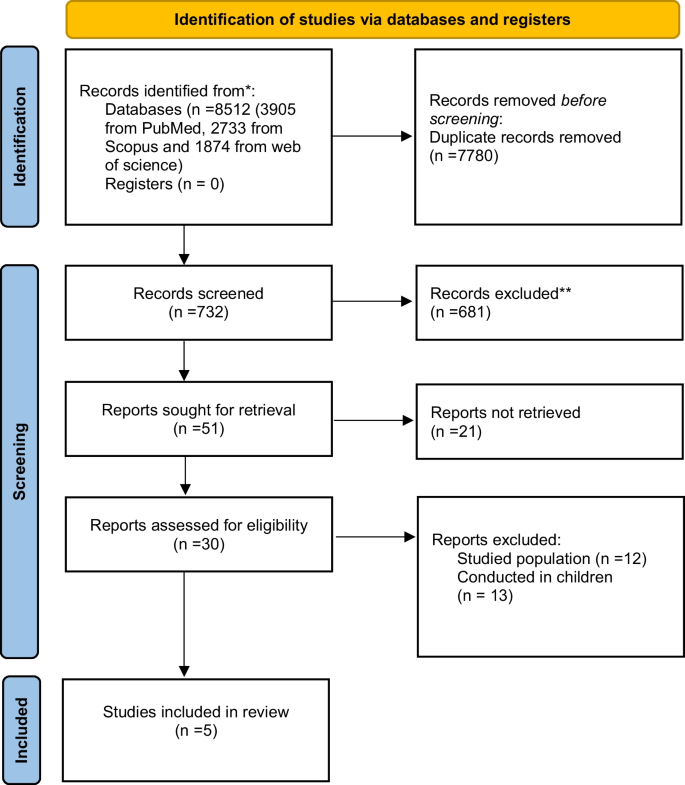

Characteristics of included studies

After excluding duplicates and irrelevant studies based on screening of the title and abstract, 30 full-text articles were reviewed in detail for eligibility and finally 5 studies met our specified inclusion criteria. The PRISMA flowchart of the study is shown in Fig. 1 .

The PRISMA flowchart of the study

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the five included SRs of the effects of nutritional program/interventions in HIV-positive adults [ 10 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. The nutrition interventions for HIV patients are classified into three groups including education/counseling, supplementation with macro- and micronutrients, and food and nutrition supporting programs. Two of five included SRs were Cochrane systematic reviews [ 13 , 15 ]. Most of the included studies were searched at least two databases including Embase and PubMed/Medline.

The three of included SRs were assessed the macronutrient supplementation in HIV-positive adults [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Two studies conducted by Tesfay et al. [ 10 ] and Tong et al. [ 16 ] were evaluated nutrition assessment, counseling, and support (NACS) interventions.

The primary outcomes of included studies were weight, BMI, fat-free mass, fat mass, viral load, CD4 count, and dietary intake.

The intervention location in the most of the included SRs was outpatients clinics or community-based settings [ 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Furthermore, in the two SRs, the multiple setting interventions (conducted in the hospital and outpatient clinic or community-based settings) were included [ 10 , 16 ].

Methodological quality of the included reviews

The methodological quality of included SRs articles is depicted in Table 2 . According to AMSTAR2 quality assessment tool, SRs conducted by Grobler et al. [ 13 ], Mahlungulu et al. [ 15 ] which were Cochrane systematic reviews had high quality. The Hong et al. [ 14 ] and Tang et al. [ 16 ] studies had moderate quality, and only one of them possess low quality [ 10 ] (Table 2 ).

Nutritional intervention plays a crucial role in the management of HIV infection. People living with HIV often experience malnutrition and weight loss due to various factors such as decreased appetite, nutrient malabsorption, increased energy expenditure, and opportunistic infections [ 17 ]. Nutritional intervention is a critical component of the overall management of HIV infection. It helps support immune function, prevent malnutrition, and improve overall health outcomes for individuals living with HIV. Here, we discuss our findings in three sections.

Nutrition education/counseling

Nutrition education or counseling has been shown to assist and improve dietary intake and nutritional status in HIV-positive adults in different settings by increasing individual knowledge about healthy food choices [ 10 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ]. In studies conducted by Grobler et al. [ 13 ], Mahlungulu et al. [ 15 ], nutrition education or counseling was one component of the nutritional programs in HIV-positive patients.

Despite the value of nutrition education/counseling in HIV treatment programs, there is little research in this field. Nutrition counseling as a cost-effective intervention especially in developing countries with limited resources and high prevalence of nutritional deficiencies must be in the first line of nutrition intervention in HIV management [ 8 ]. To improve the health and nutrition status of people living with HIV, the expertise of a registered dietitian/nutritionist as part of the health care team should be considered.

Supplementation with macro- and micronutrients

Based on previous evidences, reduction of serum antioxidant vitamins and minerals was reported during the progression of HIV with high oxidative stress. So, intervention with foods and supplements including macro- and micronutrients is necessary for strengthen the immune system. Furthermore, people with HIV should be aware of health benefits of essential nutrients along with lifestyle changes to improve nutritional status and the immune system [ 18 ]. The effectiveness of supplementation with macro- and micronutrients was reviewed by Hong et al. to improve immune defense system and quality of life of HIV patients. They found that supplementation with selenium, zinc, iron, probiotic, vitamins A, B, C, and E improved quality of life and immunity in HIV-infected patients. Furthermore, Hong et al. [ 14 ] showed that protein-energy-fortified macronutrient supplements led to significant changes in nutritional status and immunological response in HIV disease.

Given the potential effectiveness of the supplementation of macronutrients and micronutrients in HIV, it is necessary to establish national guidelines for health care provider as well as evaluating socio-psychophysiological status to assist in their clinical decision in terms of improving nutritional status and immunologic responses [ 14 ].

Multiple interventions

Adequate nutrition is recognized as a key component in the care and support for people living with HIV due to the high prevalence of clinical undernutrition and food insecurity. There is a strong association between malnutrition and increased mortality rate in HIV-infected patients [ 19 ].

According to the nutrition requirement guideline of the World Health Organization (WHO), providing a balanced healthy diet as well as increasing energy intakes by approximately 20% to 30% to maintain body weight is vital for health and survival in individuals with HIV [ 20 ].

Nutrition assessment, counseling, and support (NACS) interventions were designed for evaluating nutritional status of undernourished people. NACS includes a wide range of interventions to prevent and treat malnutrition among HIV-infected adolescents and adults in clinical care in low-resource settings [ 16 , 21 ].

There were two review studies that examined the effect of NACS interventions on mortality, morbidity, retention in care, quality of life, prevention of HIV transmission, and weight-related nutritional outcomes [ 10 , 16 ]. In the systematic review conducted by Tang et al. [ 16 ], NACS interventions had no significant impact on all five outcomes (mortality, morbidity, retention in care, quality of life, and prevention of ongoing HIV transmission) in HIV-infected patients. Tesfay et al. showed that nutritional programs in HIV care led to some improvements in nutritional outcomes related to body weight in HIV people. However, the long-term nutrition status indicators such as food security were recommended to assess the nutritional status of people living with HIV [ 10 ]. In three narrative review studies, the multicomponent nutrition interventions including nutritional education, food aid, supplementation of macro- and micronutrients, exercise, and livelihood interventions were assessed on nutritional outcomes, quality of life, and mortality in HIV patients [ 9 , 20 , 22 ]. The available evidence suggests that nutrition education is an essential component in all settings accompanied by food assistance program as well as supplementation of macro- and micronutrients in resource-limited settings [ 20 ]. However, they reported an increase in quality of life and a decrease in mortality, as well as improvements in metabolic abnormalities and body composition following multivitamin supplementation, nutritional counseling, and exercise interventions in HIV-infected individuals [ 9 , 22 ].

Strengths and limitations

The key strength of this study is its coverage of all type of interventions in this field as well as summarizing the results of various nutrition programs in HIV patients in SRs studies. It also examines a range of HIV symptoms. However, the review has some limitations. This study only included articles published in English that may have omitted papers on a same topic that have been published in other languages. Furthermore, all reviewed studies in present review evaluated the impact of nutritional programs on undernourished individuals living with HIV in health care settings, while overnutrition as a risk factor of overweight and cardiovascular disease is important in these people and therefore this issue should be considered for future studies.

The findings of this review indicate that nutritional interventions in HIV care lead to improved nutritional symptoms and increased quality of life in these patients. However, nutritional programs on HIV care should evaluate the nutritional health of HIV-infected patients in a way that can be sustainable in the long term. In additions, demographic, clinical, nutritional, and social characteristics influence nutritional outcomes, which provide potential opportunities for future research.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Monteiro R, Azevedo I. Chronic inflammation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Mediato Inflamm. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/289645 .

Article Google Scholar

Gedle D, Mekuria G, Kumera G, Eshete T, Feyera F, Ewunetu T. Food insecurity and its associated factors among people living with HIV/AIDS receiving anti-retroviral therapy at Butajira Hospital, Southern Ethiopia. J Nutr Food Sci. 2015;5(2):2–6.

Google Scholar

Obi SN, Ifebunandu NA, Onyebuchi AK. Nutritional status of HIV-positive individuals on free HAART treatment in a developing nation. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4(11):745–9.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Singhato A, Khongkhon S, Rueangsri N, Booranasuksakul U. Effectiveness of medical nutrition therapy to improve dietary habits for promoting bone health in people living with chronic HIV. Ann Nutr Metab. 2020;76(5):313–21.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Birhane M, Loha E, Alemayehu FR. Nutritional status and associated factors among adult HIV/AIDS patients receiving ART in Dilla University referral hospital, Dilla, Southern Ethiopia. J Med Physiol Biophys. 2021;70:8–15.

Kosmiski L. Energy expenditure in HIV infection. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6):1677S-S1682.

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Musoke PM, Fergusson P. Severe malnutrition and metabolic complications of HIV-infected children in the antiretroviral era: clinical care and management in resource-limited settings. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6):1716S-S1720.

Kaye HL, Moreno-Leguizamon CJ. Nutrition education and counselling as strategic interventions to improvehealth outcomes in adult outpatients with HIV: a literature review. Afr J AIDS Res. 2010;9(3):271–83.

Aberman N-L, Rawat R, Drimie S, Claros JM, Kadiyala S. Food security and nutrition interventions in response to the AIDS epidemic: assessing global action and evidence. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):554–65.

Tesfay FH, Javanparast S, Gesesew H, Mwanri L, Ziersch A. Characteristics and impacts of nutritional programmes to address undernutrition of adults living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of evidence. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e047205.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pourmoradian S, Rezazadeh L, Tutunchi H, Ostadrahimi A. Selenium and Zinc supplementation in HIV-infected patients. Int J Vit Nutr Res. 2023:1–7.

Shea BJRB, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson E, Henry DA. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. bmj. 2017;21:358.

Grobler L, Siegfried N, Visser ME, Mahlungulu SS, Volmink J. Nutritional interventions for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004536.pub3 .

Hong H, Budhathoki C, Farley JE. Effectiveness of macronutrient supplementation on nutritional status and HIV/AIDS progression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018;27:66–74.

Mahlungulu SS, Grobler L, Visser MM, Volmink J. Nutritional interventions for reducing morbidity and mortality in people with HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2007(3):CD004536.