Creating and Scoring Essay Tests

FatCamera / Getty Images

- Tips & Strategies

- An Introduction to Teaching

- Policies & Discipline

- Community Involvement

- School Administration

- Technology in the Classroom

- Teaching Adult Learners

- Issues In Education

- Teaching Resources

- Becoming A Teacher

- Assessments & Tests

- Elementary Education

- Secondary Education

- Special Education

- Homeschooling

- M.Ed., Curriculum and Instruction, University of Florida

- B.A., History, University of Florida

Essay tests are useful for teachers when they want students to select, organize, analyze, synthesize, and/or evaluate information. In other words, they rely on the upper levels of Bloom's Taxonomy . There are two types of essay questions: restricted and extended response.

- Restricted Response - These essay questions limit what the student will discuss in the essay based on the wording of the question. For example, "State the main differences between John Adams' and Thomas Jefferson's beliefs about federalism," is a restricted response. What the student is to write about has been expressed to them within the question.

- Extended Response - These allow students to select what they wish to include in order to answer the question. For example, "In Of Mice and Men , was George's killing of Lennie justified? Explain your answer." The student is given the overall topic, but they are free to use their own judgment and integrate outside information to help support their opinion.

Student Skills Required for Essay Tests

Before expecting students to perform well on either type of essay question, we must make sure that they have the required skills to excel. Following are four skills that students should have learned and practiced before taking essay exams:

- The ability to select appropriate material from the information learned in order to best answer the question.

- The ability to organize that material in an effective manner.

- The ability to show how ideas relate and interact in a specific context.

- The ability to write effectively in both sentences and paragraphs.

Constructing an Effective Essay Question

Following are a few tips to help in the construction of effective essay questions:

- Begin with the lesson objectives in mind. Make sure to know what you wish the student to show by answering the essay question.

- Decide if your goal requires a restricted or extended response. In general, if you wish to see if the student can synthesize and organize the information that they learned, then restricted response is the way to go. However, if you wish them to judge or evaluate something using the information taught during class, then you will want to use the extended response.

- If you are including more than one essay, be cognizant of time constraints. You do not want to punish students because they ran out of time on the test.

- Write the question in a novel or interesting manner to help motivate the student.

- State the number of points that the essay is worth. You can also provide them with a time guideline to help them as they work through the exam.

- If your essay item is part of a larger objective test, make sure that it is the last item on the exam.

Scoring the Essay Item

One of the downfalls of essay tests is that they lack in reliability. Even when teachers grade essays with a well-constructed rubric, subjective decisions are made. Therefore, it is important to try and be as reliable as possible when scoring your essay items. Here are a few tips to help improve reliability in grading:

- Determine whether you will use a holistic or analytic scoring system before you write your rubric . With the holistic grading system, you evaluate the answer as a whole, rating papers against each other. With the analytic system, you list specific pieces of information and award points for their inclusion.

- Prepare the essay rubric in advance. Determine what you are looking for and how many points you will be assigning for each aspect of the question.

- Avoid looking at names. Some teachers have students put numbers on their essays to try and help with this.

- Score one item at a time. This helps ensure that you use the same thinking and standards for all students.

- Avoid interruptions when scoring a specific question. Again, consistency will be increased if you grade the same item on all the papers in one sitting.

- If an important decision like an award or scholarship is based on the score for the essay, obtain two or more independent readers.

- Beware of negative influences that can affect essay scoring. These include handwriting and writing style bias, the length of the response, and the inclusion of irrelevant material.

- Review papers that are on the borderline a second time before assigning a final grade.

- Utilizing Extended Response Items to Enhance Student Learning

- How to Create a Rubric in 6 Steps

- Study for an Essay Test

- Top 10 Tips for Passing the AP US History Exam

- ACT Format: What to Expect on the Exam

- 10 Common Test Mistakes

- Tips to Create Effective Matching Questions for Assessments

- GMAT Exam Structure, Timing, and Scoring

- Self Assessment and Writing a Graduate Admissions Essay

- Holistic Grading (Composition)

- The Computer-Based GED Test

- UC Personal Statement Prompt #1

- SAT Sections, Sample Questions and Strategies

- Tips to Cut Writing Assignment Grading Time

- Ideal College Application Essay Length

- How To Study for Biology Exams

- Faculty & Staff

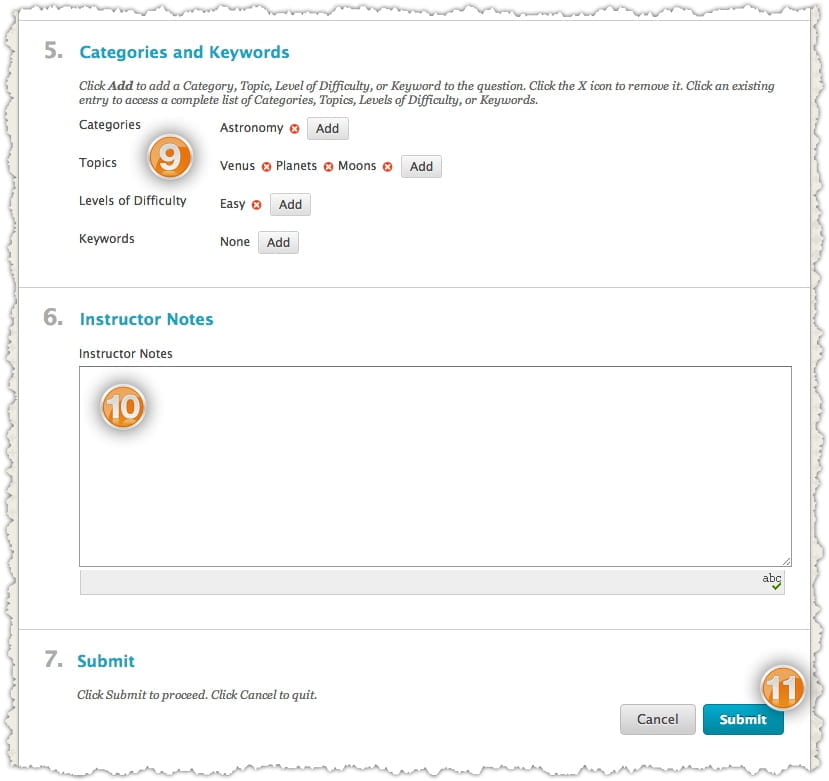

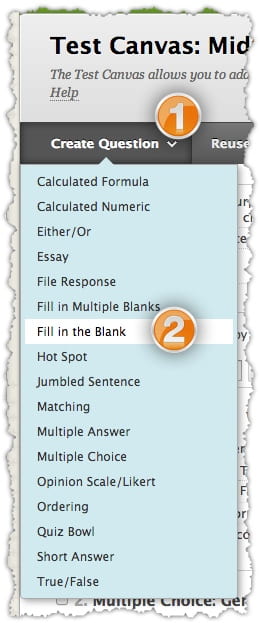

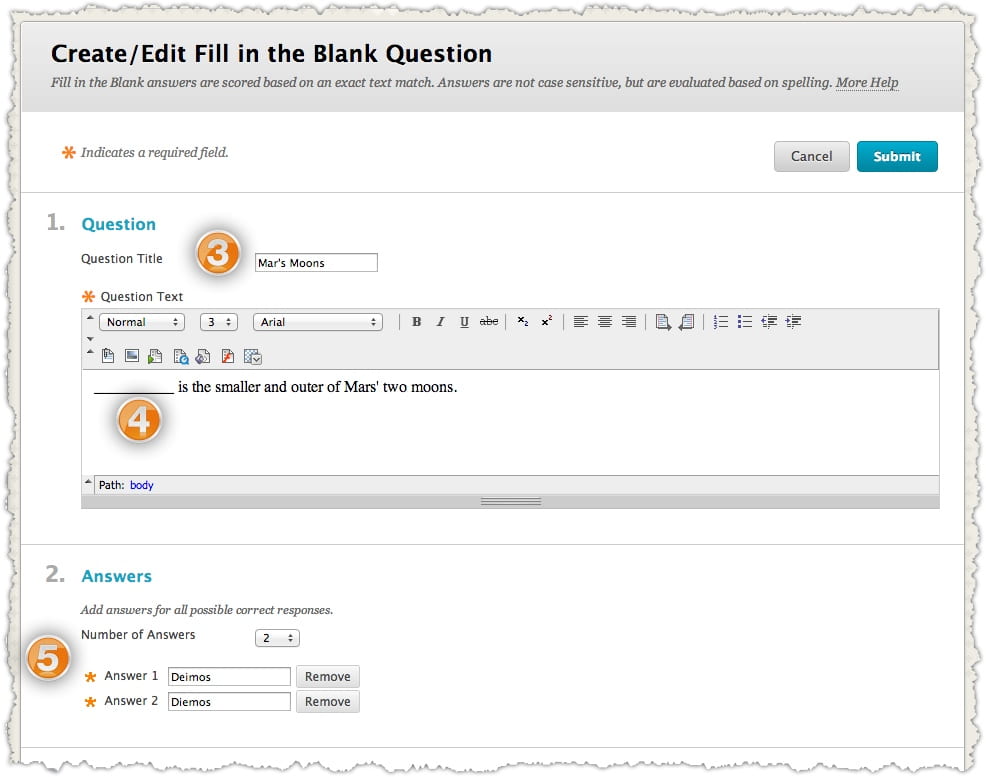

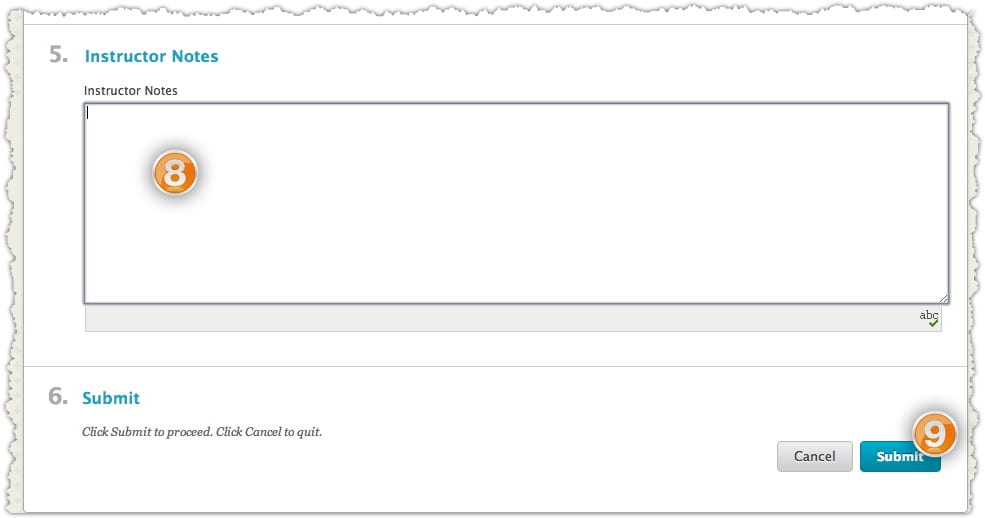

Constructing tests

Whether you use low-stakes assessments, such as practice quizzes, or high-stakes assessments, such as midterms and finals, the careful design of your tests and quizzes can provide you with better information on what and how much students have learned, as well as whether they are able to apply what they have learned.

On this page, you can explore strategies for:

Designing your test or quiz Creating multiple choice questions Creating essay and short answer questions Helping students succeed on your test/quiz Promoting academic integrity Assessing your assessment

Designing your test or quiz

Tests and quizzes can help instructors work toward a number of different goals. For example, a frequent cadence of quizzes can help motivate students, give you insight into students’ progress, and identify aspects of the course you might need to adjust.

Understanding what you want to accomplish with the test or quiz will help guide your decisionmaking about things like length, format, level of detail expected from students, and the time frame for providing feedback to the students. Regardless of what type of test or quiz you develop, it is good to:

- Align your test/quiz with your course learning outcomes and objectives. For example, if your course goals focus primarily on building students’ synthesis skills, make sure your test or quiz asks students to demonstrate their ability to connect concepts.

- Design questions that allow students to demonstrate their level of learning. To determine which concepts you might need to reinforce, create questions that give you insight into a student’s level of competency. For example, if you want students to understand a 4-step process, develop questions that show you which of the steps they grasp and which they need more help understanding.

- Develop questions that map to what you have explored and discussed in class. If you are using publisher-provided question banks or assessment tools, be sure to review and select questions carefully to ensure alignment with what students have encountered in class or in your assignments.

- Incorporate Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles into your test or quiz design. UDL embraces a commitment to offering students multiple means of demonstrating their understanding. Consider offering practice tests/quizzes and creating tests/quizzes with different types of questions (e.g., multiple choice, written, diagram-based). Also, offer options in the test/quiz itself. For example, give students a choice of questions to answer or let them choose between writing or speaking their essay response. Valuing different communication modes helps create an inclusive environment that supports all students.

Creating multiple choice questions

While it is not advisable to rely solely on multiple choice questions to gauge student learning, they are often necessary in large-enrollment courses. And multiple choice questions can add value to any course by providing instructors with quick insight into whether students have a basic understanding of key information. They are also a great way to incorporate more formative assessment into your teaching .

Creating effective multiple choice questions can be difficult, especially if you want students to go beyond simply recalling information. But it is possible to develop multiple choice questions that require higher-order thinking. Here are some strategies for writing effective multiple choice questions:

- Design questions that ask students to evaluate information (e.g., use an example, case study, or real-world dataset).

- Make sure the answer options are consistent in length and detail. If the correct answer is noticeably different, students may end up choosing the right answer for the wrong reasons.

- Design questions focused on your learning goals. Avoid writing “gotcha” questions – the goal is not to trip students up, but to assess their learning and progress toward your learning outcomes.

- Test drive your questions with a colleague or teaching assistant to determine if your intention is clear.

Creating essay and short answer questions

Essay and short answer questions that require students to compose written responses of several sentences or paragraphs offer instructors insights into students’ ability to reason, synthesize, and evaluate information. Here are some strategies for writing effective essay questions:

- Signal the type of thinking you expect students to demonstrate. Use specific words and phrases (e.g., identify, compare, critique) that guide students to how to go about responding to the question.

- Write questions that can be reasonably answered in the time allotted. Consider offering students some guideposts on how much effort they should give to a question (e.g., “Write no more than 2 short paragraphs” or “Each short answer question is worth 20 points/10% of the test”).

- Share your grading criteria before the test or quiz. Rubrics are a great way to help students prepare for an essay- or short answer-based test.

Strategies for grading essay and short answer questions

Although essay and short paragraph questions are more labor-intensive to grade than multiple-choice questions, the pay-off is often greater – they provide more insight into students’ critical thinking skills. Here are some strategies to help streamline the essay/short answer grading process:

- Develop a rubric to keep you focused on your core criteria for success. Identify the point value/percentage associated with each criterion to streamline scoring.

- Grade all student responses to the same question before moving to the next question. For example, if your test has two essay questions, grade all essay #1 responses first. Then grade all essay #2 responses. This promotes grading equity and may provide a more holistic view of how the class as a whole answered each question.

- Focus on assessing students’ ideas and arguments. Few people write beautifully in a timed test. Unless it is key to your learning outcomes, don’t grade on grammar or polish.

Helping students succeed

While important in university settings, tests aren’t commonly found outside classroom settings. Think about your own work – how often are you expected to sit down, turn over a sheet of paper, and demonstrate the isolated skill or understanding listed on the paper in less than an hour? Sound stressful? It is! And sometimes that stress can be compounded by students’ lives beyond the classroom.

“Giving a traditional test feels fair from the vantage point of an instructor….The students take it at the same time and work in the same room. But their lives outside the test spill into it. Some students might have to find child care to take an evening exam. Others…have ADHD and are under additional stress in a traditional testing environment. So test conditions can be inequitable. They are also artificial: People are rarely required to solve problems under similar pressure, without outside resources, after they graduate. They rarely have to wait for a professor to grade them to understand their own performance.” “ What fixing a snowblower taught one professor about teaching ” Chronicle of Higher Education

Many students understandably experience stress, anxiety, and apprehension about taking tests and that can affect their performance. Here are some strategies for reducing stress in testing environments:

- Set expectations. In your syllabus and on the first day of class, share your course learning outcomes and clearly define what constitutes cheating. As the quarter progresses, talk with students about the focus, time, location, and format of each test or quiz.

- Provide study questions or low-/no-stakes practice tests that scaffold to the actual test. Practice questions should ask students to engage in the same kind of thinking you will be assessing on the actual test or quiz.

- Co-create questions with your students . Ask students (individually or in small groups) to develop and answer potential test questions. Collect these and use them to create the questions for the actual test.

- Develop relevant tests/quiz questions that assess skills and knowledge you explored during lecture or discussion.

- Share examples of successful answers and provide explanations of why those answers were successful.

Promoting academic integrity

The primary goal of a test or quiz is to provide insight into a student’s understanding or ability. If a student cheats, the instructor has no opportunity to assess learning and help the student grow. There are a variety of strategies instructors can employ to create a culture of academic integrity . Here are a few specifically related to developing tests and quizzes:

- Avoid high-stakes tests. High-stakes tests (e.g., a test worth more than 25% of the course grade) make it hard for a student to rebound from a mistake. If students worry that a disastrous exam will make it impossible to pass the course, they are more likely to cheat. Opt for assessments that provides students opportunities to grow and rebound from missteps (e.g., more low- or no-stakes assignments ).

- Require students to reference specific materials or assignments in their answers. Asking students to draw on specific materials in their answers makes it harder for students to copy/paste answers from other sources.

- Require students to explain or justify their answers . If it isn’t feasible to do this during the test, consider developing a post-test assignment that asks learners to justify their test answers. Instructors need not spend a lot of time grading these; just spot check them to get a sense of whether learners are thinking for themselves.

- Prompt students to apply their learning through questions built around discrete scenarios, real-world problems, or unique datasets.

- Use question banks and randomize questions when building your quiz or test.

- Include a certification question. Ask students to acknowledge their academic integrity responsibilities at the beginning of a quiz/exam with a question like this one: “The work I submit is my own work. I will not consult with, discuss the contents of this quiz/test with, or show the quiz/test to anyone else, including other students. I understand that doing so is a violation of UW’s academic integrity policy and may subject me to disciplinary action, including suspension and dismissal.”

- Allow learners to work together. Ask learners to collaborate to answer quiz/exam questions. By helping each other, learners engage with the course’s content and develop valuable collaboration skills.

Assessing your assessment

Observation and iteration are key parts of a reflective teaching practice . Take time after you’ve graded a test or quiz to examine its effectiveness and identify ways to improve it. Start by asking yourself some basic questions:

- Did the test/quiz assess what I wanted it to assess? Based on students’ performance on your questions, are you confident that students grasp the concepts and skills you designed the test/quiz to measure?

- Did the test align with my course goals and learning objectives? Does student performance indicate that they have made progress toward your learning goals? If not, you may need to revise your questions.

- Were there particular questions that many students missed? If so, reconsider how you’ve worded the question or examine whether the question asked students about something you didn’t discuss (or didn’t discuss enough) in class.

- Were students able to finish the test or quiz in the time allotted? If not, reconsider the number and difficulty of your questions.

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- Focus and Precision: How to Write Essays that Answer the Question

About the Author Stephanie Allen read Classics and English at St Hugh’s College, Oxford, and is currently researching a PhD in Early Modern Academic Drama at the University of Fribourg.

We’ve all been there. You’ve handed in an essay and you think it’s pretty great: it shows off all your best ideas, and contains points you’re sure no one else will have thought of.

You’re not totally convinced that what you’ve written is relevant to the title you were given – but it’s inventive, original and good. In fact, it might be better than anything that would have responded to the question. But your essay isn’t met with the lavish praise you expected. When it’s tossed back onto your desk, there are huge chunks scored through with red pen, crawling with annotations like little red fire ants: ‘IRRELEVANT’; ‘A bit of a tangent!’; ‘???’; and, right next to your best, most impressive killer point: ‘Right… so?’. The grade your teacher has scrawled at the end is nowhere near what your essay deserves. In fact, it’s pretty average. And the comment at the bottom reads something like, ‘Some good ideas, but you didn’t answer the question!’.

If this has ever happened to you (and it has happened to me, a lot), you’ll know how deeply frustrating it is – and how unfair it can seem. This might just be me, but the exhausting process of researching, having ideas, planning, writing and re-reading makes me steadily more attached to the ideas I have, and the things I’ve managed to put on the page. Each time I scroll back through what I’ve written, or planned, so far, I become steadily more convinced of its brilliance. What started off as a scribbled note in the margin, something extra to think about or to pop in if it could be made to fit the argument, sometimes comes to be backbone of a whole essay – so, when a tutor tells me my inspired paragraph about Ted Hughes’s interpretation of mythology isn’t relevant to my essay on Keats, I fail to see why. Or even if I can see why, the thought of taking it out is wrenching. Who cares if it’s a bit off-topic? It should make my essay stand out, if anything! And an examiner would probably be happy not to read yet another answer that makes exactly the same points. If you recognise yourself in the above, there are two crucial things to realise. The first is that something has to change: because doing well in high school exam or coursework essays is almost totally dependent on being able to pin down and organise lots of ideas so that an examiner can see that they convincingly answer a question. And it’s a real shame to work hard on something, have good ideas, and not get the marks you deserve. Writing a top essay is a very particular and actually quite simple challenge. It’s not actually that important how original you are, how compelling your writing is, how many ideas you get down, or how beautifully you can express yourself (though of course, all these things do have their rightful place). What you’re doing, essentially, is using a limited amount of time and knowledge to really answer a question. It sounds obvious, but a good essay should have the title or question as its focus the whole way through . It should answer it ten times over – in every single paragraph, with every fact or figure. Treat your reader (whether it’s your class teacher or an external examiner) like a child who can’t do any interpretive work of their own; imagine yourself leading them through your essay by the hand, pointing out that you’ve answered the question here , and here , and here. Now, this is all very well, I imagine you objecting, and much easier said than done. But never fear! Structuring an essay that knocks a question on the head is something you can learn to do in a couple of easy steps. In the next few hundred words, I’m going to share with you what I’ve learned through endless, mindless crossings-out, rewordings, rewritings and rethinkings.

Top tips and golden rules

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been told to ‘write the question at the top of every new page’- but for some reason, that trick simply doesn’t work for me. If it doesn’t work for you either, use this three-part process to allow the question to structure your essay:

1) Work out exactly what you’re being asked

It sounds really obvious, but lots of students have trouble answering questions because they don’t take time to figure out exactly what they’re expected to do – instead, they skim-read and then write the essay they want to write. Sussing out a question is a two-part process, and the first part is easy. It means looking at the directions the question provides as to what sort of essay you’re going to write. I call these ‘command phrases’ and will go into more detail about what they mean below. The second part involves identifying key words and phrases.

2) Be as explicit as possible

Use forceful, persuasive language to show how the points you’ve made do answer the question. My main focus so far has been on tangential or irrelevant material – but many students lose marks even though they make great points, because they don’t quite impress how relevant those points are. Again, I’ll talk about how you can do this below.

3) Be brutally honest with yourself about whether a point is relevant before you write it.

It doesn’t matter how impressive, original or interesting it is. It doesn’t matter if you’re panicking, and you can’t think of any points that do answer the question. If a point isn’t relevant, don’t bother with it. It’s a waste of time, and might actually work against you- if you put tangential material in an essay, your reader will struggle to follow the thread of your argument, and lose focus on your really good points.

Put it into action: Step One

Let’s imagine you’re writing an English essay about the role and importance of the three witches in Macbeth . You’re thinking about the different ways in which Shakespeare imagines and presents the witches, how they influence the action of the tragedy, and perhaps the extent to which we’re supposed to believe in them (stay with me – you don’t have to know a single thing about Shakespeare or Macbeth to understand this bit!). Now, you’ll probably have a few good ideas on this topic – and whatever essay you write, you’ll most likely use much of the same material. However, the detail of the phrasing of the question will significantly affect the way you write your essay. You would draw on similar material to address the following questions: Discuss Shakespeare’s representation of the three witches in Macbeth . How does Shakespeare figure the supernatural in Macbeth ? To what extent are the three witches responsible for Macbeth’s tragic downfall? Evaluate the importance of the three witches in bringing about Macbeth’s ruin. Are we supposed to believe in the three witches in Macbeth ? “Within Macbeth ’s representation of the witches, there is profound ambiguity about the actual significance and power of their malevolent intervention” (Stephen Greenblatt). Discuss. I’ve organised the examples into three groups, exemplifying the different types of questions you might have to answer in an exam. The first group are pretty open-ended: ‘discuss’- and ‘how’-questions leave you room to set the scope of the essay. You can decide what the focus should be. Beware, though – this doesn’t mean you don’t need a sturdy structure, or a clear argument, both of which should always be present in an essay. The second group are asking you to evaluate, constructing an argument that decides whether, and how far something is true. Good examples of hypotheses (which your essay would set out to prove) for these questions are:

- The witches are the most important cause of tragic action in Macbeth.

- The witches are partially, but not entirely responsible for Macbeth’s downfall, alongside Macbeth’s unbridled ambition, and that of his wife.

- We are not supposed to believe the witches: they are a product of Macbeth’s psyche, and his downfall is his own doing.

- The witches’ role in Macbeth’s downfall is deliberately unclear. Their claim to reality is shaky – finally, their ambiguity is part of an uncertain tragic universe and the great illusion of the theatre. (N.B. It’s fine to conclude that a question can’t be answered in black and white, certain terms – as long as you have a firm structure, and keep referring back to it throughout the essay).

The final question asks you to respond to a quotation. Students tend to find these sorts of questions the most difficult to answer, but once you’ve got the hang of them I think the title does most of the work for you – often implicitly providing you with a structure for your essay. The first step is breaking down the quotation into its constituent parts- the different things it says. I use brackets: ( Within Macbeth ’s representation of the witches, ) ( there is profound ambiguity ) about the ( actual significance ) ( and power ) of ( their malevolent intervention ) Examiners have a nasty habit of picking the most bewildering and terrifying-sounding quotations: but once you break them down, they’re often asking for something very simple. This quotation, for example, is asking exactly the same thing as the other questions. The trick here is making sure you respond to all the different parts. You want to make sure you discuss the following:

- Do you agree that the status of the witches’ ‘malevolent intervention’ is ambiguous?

- What is its significance?

- How powerful is it?

Step Two: Plan

Having worked out exactly what the question is asking, write out a plan (which should be very detailed in a coursework essay, but doesn’t have to be more than a few lines long in an exam context) of the material you’ll use in each paragraph. Make sure your plan contains a sentence at the end of each point about how that point will answer the question. A point from my plan for one of the topics above might look something like this:

To what extent are we supposed to believe in the three witches in Macbeth ? Hypothesis: The witches’ role in Macbeth’s downfall is deliberately unclear. Their claim to reality is uncertain – finally, they’re part of an uncertain tragic universe and the great illusion of the theatre. Para.1: Context At the time Shakespeare wrote Macbeth , there were many examples of people being burned or drowned as witches There were also people who claimed to be able to exorcise evil demons from people who were ‘possessed’. Catholic Christianity leaves much room for the supernatural to exist This suggests that Shakespeare’s contemporary audience might, more readily than a modern one, have believed that witches were a real phenomenon and did exist.

My final sentence (highlighted in red) shows how the material discussed in the paragraph answers the question. Writing this out at the planning stage, in addition to clarifying your ideas, is a great test of whether a point is relevant: if you struggle to write the sentence, and make the connection to the question and larger argument, you might have gone off-topic.

Step Three: Paragraph beginnings and endings

The final step to making sure you pick up all the possible marks for ‘answering the question’ in an essay is ensuring that you make it explicit how your material does so. This bit relies upon getting the beginnings and endings of paragraphs just right. To reiterate what I said above, treat your reader like a child: tell them what you’re going to say; tell them how it answers the question; say it, and then tell them how you’ve answered the question. This need not feel clumsy, awkward or repetitive. The first sentence of each new paragraph or point should, without giving too much of your conclusion away, establish what you’re going to discuss, and how it answers the question. The opening sentence from the paragraph I planned above might go something like this:

Early modern political and religious contexts suggest that Shakespeare’s contemporary audience might more readily have believed in witches than his modern readers.

The sentence establishes that I’m going to discuss Jacobean religion and witch-burnings, and also what I’m going to use those contexts to show. I’d then slot in all my facts and examples in the middle of the paragraph. The final sentence (or few sentences) should be strong and decisive, making a clear connection to the question you’ve been asked:

Contemporary suspicion that witches did exist, testified to by witch-hunts and exorcisms, is crucial to our understanding of the witches in Macbeth. To the early modern consciousness, witches were a distinctly real and dangerous possibility – and the witches in the play would have seemed all-the-more potent and terrifying as a result.

Step Four: Practice makes perfect

The best way to get really good at making sure you always ‘answer the question’ is to write essay plans rather than whole pieces. Set aside a few hours, choose a couple of essay questions from past papers, and for each:

- Write a hypothesis

- Write a rough plan of what each paragraph will contain

- Write out the first and last sentence of each paragraph

You can get your teacher, or a friend, to look through your plans and give you feedback . If you follow this advice, fingers crossed, next time you hand in an essay, it’ll be free from red-inked comments about irrelevance, and instead showered with praise for the precision with which you handled the topic, and how intently you focused on answering the question. It can seem depressing when your perfect question is just a minor tangent from the question you were actually asked, but trust me – high praise and good marks are all found in answering the question in front of you, not the one you would have liked to see. Teachers do choose the questions they set you with some care, after all; chances are the question you were set is the more illuminating and rewarding one as well.

Image credits: banner ; Keats ; Macbeth ; James I ; witches .

Comments are closed.

Essay Exams

What this handout is about.

At some time in your undergraduate career, you’re going to have to write an essay exam. This thought can inspire a fair amount of fear: we struggle enough with essays when they aren’t timed events based on unknown questions. The goal of this handout is to give you some easy and effective strategies that will help you take control of the situation and do your best.

Why do instructors give essay exams?

Essay exams are a useful tool for finding out if you can sort through a large body of information, figure out what is important, and explain why it is important. Essay exams challenge you to come up with key course ideas and put them in your own words and to use the interpretive or analytical skills you’ve practiced in the course. Instructors want to see whether:

- You understand concepts that provide the basis for the course

- You can use those concepts to interpret specific materials

- You can make connections, see relationships, draw comparisons and contrasts

- You can synthesize diverse information in support of an original assertion

- You can justify your own evaluations based on appropriate criteria

- You can argue your own opinions with convincing evidence

- You can think critically and analytically about a subject

What essay questions require

Exam questions can reach pretty far into the course materials, so you cannot hope to do well on them if you do not keep up with the readings and assignments from the beginning of the course. The most successful essay exam takers are prepared for anything reasonable, and they probably have some intelligent guesses about the content of the exam before they take it. How can you be a prepared exam taker? Try some of the following suggestions during the semester:

- Do the reading as the syllabus dictates; keeping up with the reading while the related concepts are being discussed in class saves you double the effort later.

- Go to lectures (and put away your phone, the newspaper, and that crossword puzzle!).

- Take careful notes that you’ll understand months later. If this is not your strong suit or the conventions for a particular discipline are different from what you are used to, ask your TA or the Learning Center for advice.

- Participate in your discussion sections; this will help you absorb the material better so you don’t have to study as hard.

- Organize small study groups with classmates to explore and review course materials throughout the semester. Others will catch things you might miss even when paying attention. This is not cheating. As long as what you write on the essay is your own work, formulating ideas and sharing notes is okay. In fact, it is a big part of the learning process.

- As an exam approaches, find out what you can about the form it will take. This will help you forecast the questions that will be on the exam, and prepare for them.

These suggestions will save you lots of time and misery later. Remember that you can’t cram weeks of information into a single day or night of study. So why put yourself in that position?

Now let’s focus on studying for the exam. You’ll notice the following suggestions are all based on organizing your study materials into manageable chunks of related material. If you have a plan of attack, you’ll feel more confident and your answers will be more clear. Here are some tips:

- Don’t just memorize aimlessly; clarify the important issues of the course and use these issues to focus your understanding of specific facts and particular readings.

- Try to organize and prioritize the information into a thematic pattern. Look at what you’ve studied and find a way to put things into related groups. Find the fundamental ideas that have been emphasized throughout the course and organize your notes into broad categories. Think about how different categories relate to each other.

- Find out what you don’t know, but need to know, by making up test questions and trying to answer them. Studying in groups helps as well.

Taking the exam

Read the exam carefully.

- If you are given the entire exam at once and can determine your approach on your own, read the entire exam before you get started.

- Look at how many points each part earns you, and find hints for how long your answers should be.

- Figure out how much time you have and how best to use it. Write down the actual clock time that you expect to take in each section, and stick to it. This will help you avoid spending all your time on only one section. One strategy is to divide the available time according to percentage worth of the question. You don’t want to spend half of your time on something that is only worth one tenth of the total points.

- As you read, make tentative choices of the questions you will answer (if you have a choice). Don’t just answer the first essay question you encounter. Instead, read through all of the options. Jot down really brief ideas for each question before deciding.

- Remember that the easiest-looking question is not always as easy as it looks. Focus your attention on questions for which you can explain your answer most thoroughly, rather than settle on questions where you know the answer but can’t say why.

Analyze the questions

- Decide what you are being asked to do. If you skim the question to find the main “topic” and then rush to grasp any related ideas you can recall, you may become flustered, lose concentration, and even go blank. Try looking closely at what the question is directing you to do, and try to understand the sort of writing that will be required.

- Focus on what you do know about the question, not on what you don’t.

- Look at the active verbs in the assignment—they tell you what you should be doing. We’ve included some of these below, with some suggestions on what they might mean. (For help with this sort of detective work, see the Writing Center handout titled Reading Assignments.)

Information words, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject. Information words may include:

- define—give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning.

- explain why/how—give reasons why or examples of how something happened.

- illustrate—give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject.

- summarize—briefly cover the important ideas you learned about the subject.

- trace—outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form.

- research—gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you’ve found.

Relation words ask you to demonstrate how things are connected. Relation words may include:

- compare—show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different).

- contrast—show how two or more things are dissimilar.

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation.

- cause—show how one event or series of events made something else happen.

- relate—show or describe the connections between things.

Interpretation words ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Don’t see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation. Interpretation words may include:

- prove, justify—give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth.

- evaluate, respond, assess—state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons (you may want to compare your subject to something else).

- support—give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe).

- synthesize—put two or more things together that haven’t been put together before; don’t just summarize one and then the other, and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together (as opposed to compare and contrast—see above).

- analyze—look closely at the components of something to figure out how it works, what it might mean, or why it is important.

- argue—take a side and defend it (with proof) against the other side.

Plan your answers

Think about your time again. How much planning time you should take depends on how much time you have for each question and how many points each question is worth. Here are some general guidelines:

- For short-answer definitions and identifications, just take a few seconds. Skip over any you don’t recognize fairly quickly, and come back to them when another question jogs your memory.

- For answers that require a paragraph or two, jot down several important ideas or specific examples that help to focus your thoughts.

- For longer answers, you will need to develop a much more definite strategy of organization. You only have time for one draft, so allow a reasonable amount of time—as much as a quarter of the time you’ve allotted for the question—for making notes, determining a thesis, and developing an outline.

- For questions with several parts (different requests or directions, a sequence of questions), make a list of the parts so that you do not miss or minimize one part. One way to be sure you answer them all is to number them in the question and in your outline.

- You may have to try two or three outlines or clusters before you hit on a workable plan. But be realistic—you want a plan you can develop within the limited time allotted for your answer. Your outline will have to be selective—not everything you know, but what you know that you can state clearly and keep to the point in the time available.

Again, focus on what you do know about the question, not on what you don’t.

Writing your answers

As with planning, your strategy for writing depends on the length of your answer:

- For short identifications and definitions, it is usually best to start with a general identifying statement and then move on to describe specific applications or explanations. Two sentences will almost always suffice, but make sure they are complete sentences. Find out whether the instructor wants definition alone, or definition and significance. Why is the identification term or object important?

- For longer answers, begin by stating your forecasting statement or thesis clearly and explicitly. Strive for focus, simplicity, and clarity. In stating your point and developing your answers, you may want to use important course vocabulary words from the question. For example, if the question is, “How does wisteria function as a representation of memory in Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom?” you may want to use the words wisteria, representation, memory, and Faulkner) in your thesis statement and answer. Use these important words or concepts throughout the answer.

- If you have devised a promising outline for your answer, then you will be able to forecast your overall plan and its subpoints in your opening sentence. Forecasting impresses readers and has the very practical advantage of making your answer easier to read. Also, if you don’t finish writing, it tells your reader what you would have said if you had finished (and may get you partial points).

- You might want to use briefer paragraphs than you ordinarily do and signal clear relations between paragraphs with transition phrases or sentences.

- As you move ahead with the writing, you may think of new subpoints or ideas to include in the essay. Stop briefly to make a note of these on your original outline. If they are most appropriately inserted in a section you’ve already written, write them neatly in the margin, at the top of the page, or on the last page, with arrows or marks to alert the reader to where they fit in your answer. Be as neat and clear as possible.

- Don’t pad your answer with irrelevancies and repetitions just to fill up space. Within the time available, write a comprehensive, specific answer.

- Watch the clock carefully to ensure that you do not spend too much time on one answer. You must be realistic about the time constraints of an essay exam. If you write one dazzling answer on an exam with three equally-weighted required questions, you earn only 33 points—not enough to pass at most colleges. This may seem unfair, but keep in mind that instructors plan exams to be reasonably comprehensive. They want you to write about the course materials in two or three or more ways, not just one way. Hint: if you finish a half-hour essay in 10 minutes, you may need to develop some of your ideas more fully.

- If you run out of time when you are writing an answer, jot down the remaining main ideas from your outline, just to show that you know the material and with more time could have continued your exposition.

- Double-space to leave room for additions, and strike through errors or changes with one straight line (avoid erasing or scribbling over). Keep things as clean as possible. You never know what will earn you partial credit.

- Write legibly and proofread. Remember that your instructor will likely be reading a large pile of exams. The more difficult they are to read, the more exasperated the instructor might become. Your instructor also cannot give you credit for what they cannot understand. A few minutes of careful proofreading can improve your grade.

Perhaps the most important thing to keep in mind in writing essay exams is that you have a limited amount of time and space in which to get across the knowledge you have acquired and your ability to use it. Essay exams are not the place to be subtle or vague. It’s okay to have an obvious structure, even the five-paragraph essay format you may have been taught in high school. Introduce your main idea, have several paragraphs of support—each with a single point defended by specific examples, and conclude with a restatement of your main point and its significance.

Some physiological tips

Just think—we expect athletes to practice constantly and use everything in their abilities and situations in order to achieve success. Yet, somehow many students are convinced that one day’s worth of studying, no sleep, and some well-placed compliments (“Gee, Dr. So-and-so, I really enjoyed your last lecture”) are good preparation for a test. Essay exams are like any other testing situation in life: you’ll do best if you are prepared for what is expected of you, have practiced doing it before, and have arrived in the best shape to do it. You may not want to believe this, but it’s true: a good night’s sleep and a relaxed mind and body can do as much or more for you as any last-minute cram session. Colleges abound with tales of woe about students who slept through exams because they stayed up all night, wrote an essay on the wrong topic, forgot everything they studied, or freaked out in the exam and hyperventilated. If you are rested, breathing normally, and have brought along some healthy, energy-boosting snacks that you can eat or drink quietly, you are in a much better position to do a good job on the test. You aren’t going to write a good essay on something you figured out at 4 a.m. that morning. If you prepare yourself well throughout the semester, you don’t risk your whole grade on an overloaded, undernourished brain.

If for some reason you get yourself into this situation, take a minute every once in a while during the test to breathe deeply, stretch, and clear your brain. You need to be especially aware of the likelihood of errors, so check your essays thoroughly before you hand them in to make sure they answer the right questions and don’t have big oversights or mistakes (like saying “Hitler” when you really mean “Churchill”).

If you tend to go blank during exams, try studying in the same classroom in which the test will be given. Some research suggests that people attach ideas to their surroundings, so it might jog your memory to see the same things you were looking at while you studied.

Try good luck charms. Bring in something you associate with success or the support of your loved ones, and use it as a psychological boost.

Take all of the time you’ve been allotted. Reread, rework, and rethink your answers if you have extra time at the end, rather than giving up and handing the exam in the minute you’ve written your last sentence. Use every advantage you are given.

Remember that instructors do not want to see you trip up—they want to see you do well. With this in mind, try to relax and just do the best you can. The more you panic, the more mistakes you are liable to make. Put the test in perspective: will you die from a poor performance? Will you lose all of your friends? Will your entire future be destroyed? Remember: it’s just a test.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Axelrod, Rise B., and Charles R. Cooper. 2016. The St. Martin’s Guide to Writing , 11th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Fowler, Ramsay H., and Jane E. Aaron. 2016. The Little, Brown Handbook , 13th ed. Boston: Pearson.

Gefvert, Constance J. 1988. The Confident Writer: A Norton Handbook , 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

Kirszner, Laurie G. 1988. Writing: A College Rhetoric , 2nd ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Woodman, Leonara, and Thomas P. Adler. 1988. The Writer’s Choices , 2nd ed. Northbrook, Illinois: Scott Foresman.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Essay Test Preparation Tips and Strategies

Essay test questions can be very intimidating, but they can also be very rewarding. Unlike other types of exams (i.e., multiple choice, true or false, etc.) essay tests allow you develop an answer based on your understanding or knowledge.

If you’ve studied all semester, understand the course concepts, and have reviewed prior to the test, the following strategies can help you improve your performance on essay tests and exams.

Strategies to Help You Improve Your Performance on Essay Tests and Exams

Read the directions.

Reading the directions seems so obvious. Unfortunately, it’s still one of the biggest test taking mistakes students make. Before answering an essay question, thoroughly read the instructions. Do not jump to the answer without being sure of what exactly the question is asking. In many cases, the teacher is looking for specific types of responses. Never assume you know what is being asked, or what is required, until you’ve read the entire question.

Ask for clarification

Read essay questions in their entirety before preparing an answer. If the instructions are unclear, or you simply don’t understand a question, ask the teacher for clarification. Chances are if you’re confused so is someone else. Never be scared to ask for clarification from your teacher or instructor.

Provide detail

Provide as many details and specific examples when answering an essay question as you can. Teachers are usually looking for very specific responses to see whether or not you’ve learned the material. The more relevant detail you provide, the higher grade is likely to be. However, only include correct, accurate and relevant information. Including irrelevant “filler” that doesn’t support your answer will likely lower your grade.

Budget your time

Manage your time wisely when answering essay questions so you are able answer all the questions, not just the easy or hard ones. If you finish your test before time is up, go back and review your answers and provide additional details.

We recommend answering those essay questions you’re most familiar with first and then tackling more challenging questions after. It’s also not uncommon on essay tests for some questions to be worth more than others. When budgeting your time, make sure to allocate more time to those questions that are worth the most.

Follow the instructions

When a question is only requiring facts, be sure to avoid sharing opinions. Only provide the information the instructions request. It’s important to provide an answer that matches the type of essay question being asked. You’ll find a list of common types of essay questions at the bottom of this page.

In your answers, get to the point and be very clear. It is generally best to be as concise as possible. If you provide numerous facts or details, be sure they’re related to the question. A typical essay answer should be between 200 and 800 words (2-8 paragraphs) but more isn’t necessarily better. Focus on substance over quantity.

Write clearly and legibly

Be sure your essays are legible and easy to understand. If a teacher has a difficult time reading or understanding what you’ve written, you could receive a lower score.

Get organized

Organize your thoughts before answering your essay question. We even recommend developing a short outline before preparing your answer. This strategy will help you save time and keep your essay organized. Organizing your thoughts and preparing a short outline will allow you to write more clearly and concisely.

Get to the point – Focus on substance

Only spend time answering the question and keep your essays focused. An overly long introduction and conclusion can be unnecessary. If your essay does not thoroughly answer the question and provide substance, a well developed introduction or conclusion will do you no good.

Use paragraphs to separate ideas

When developing your essay, keep main ideas and other important details separated with paragraphs. An essay response should have three parts: the introduction; the body; and the conclusion. The introduction is typically one paragraph, as is the conclusion. The body of the essay usually consists of 2 to 6 paragraphs depending on the type of essay and the information being presented.

Go back and review

If time permits, review your answers and make changes if necessary. Make sure you employed correct grammar and that your essays are well written. It’s not uncommon to make silly mistakes your first time through your essay. Reviewing your work is always a good idea.

Approximate

When you are unsure of specific dates, just approximate dates. For example, if you know an event occurred sometime during the 1820’s, then just write, “in the early 1800’s.”

Common Question Types on Essay Exams

Being able to identify and becoming familiar with the most common types of essay test questions is key to improving performance on essay exams. The following are 5 of the most common question types you’ll find on essay exams.

1. Identify

Identify essay questions ask for short, concise answers and typically do not require a fully developed essay.

- Ask yourself: “What is the idea or concept in question?”, “What are the main characteristics?”, “What does this mean?”

- Keywords to look for: Summarize, List, Describe, Define, Enumerate, State

- Example question: “Define what is meant by ‘separation of church and state.'”

Explain essay questions require a full-length essay with a fully developed response that provides ample supporting detail.

- Ask yourself: “What are the main points?”, “Why is this the case?”

- Keywords to look for: Discuss, Explain, Analyze, Illustrate

- Example question: “Discuss the differences between the political views of democrats and republicans. Use specific examples from each party’s 2017 presidential campaign to argue which views are more in line with U.S. national interests.”

Compare essay questions require an analysis in essay form which focuses on similarities, differences, and connections between specific ideas or concepts.

- Ask yourself: “What are the main concepts or ideas?”, “What are the similarities?”, “What are the differences?”

- Keywords to look for: Compare, Contrast, Relate

- Example question: “Compare the value of attending a community college to the value of attending a 4-year university. Which would you rather attend?”

Argue essay questions require you to form an opinion or take a position on an issue and defend your position against alternative positions using arguments backed by analysis and information.

- Ask yourself: “Is this position correct?”, “Why is this issue true?”

- Keywords to look for: Prove, Justify

- Example question: “Argue whether robotics will replace blue collar manufacturing jobs in the next ten years.”

Assess essay questions involve assessing an issue, idea or question by describing acceptable criteria and defending a position/judgment on the issue.

- Ask yourself: “What is the main idea/issue and what does it mean?”, “Why is the issue important?”, “What are its strengths?”, “What are the weaknesses?”

- Keywords to look for: Evaluate, Criticize, Evaluate, Interpret

- Example question: “With respect to U.S. national security, evaluate the benefit of constructing a wall along the southern border of the United States of America.”

Similar Posts:

- Guide on College and University Admissions

- Preschool – Everything You Need to Know

- How to Handle the Transition from High School to College

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name and email in this browser for the next time I comment.

Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation, creating exams.

How can you design fair, yet challenging, exams that accurately gauge student learning? Here are some general guidelines. There are also many resources, in print and on the web, that offer strategies for designing particular kinds of exams, such as multiple-choice.

Choose appropriate item types for your objectives.

Should you assign essay questions on your exams? Problem sets? Multiple-choice questions? It depends on your learning objectives. For example, if you want students to articulate or justify an economic argument, then multiple-choice questions are a poor choice because they do not require students to articulate anything. However, multiple-choice questions (if well-constructed) might effectively assess students’ ability to recognize a logical economic argument or to distinguish it from an illogical one. If your goal is for students to match technical terms to their definitions, essay questions may not be as efficient a means of assessment as a simple matching task. There is no single best type of exam question: the important thing is that the questions reflect your learning objectives.

Highlight how the exam aligns with course objectives.

Identify which course objectives the exam addresses (e.g., “This exam assesses your ability to use sociological terminology appropriately, and to apply the principles we have learned in the course to date”). This helps students see how the components of the course align, reassures them about their ability to perform well (assuming they have done the required work), and activates relevant experiences and knowledge from earlier in the course.

Write instructions that are clear, explicit, and unambiguous.

Make sure that students know exactly what you want them to do. Be more explicit about your expectations than you may think is necessary. Otherwise, students may make assumptions that run them into trouble. For example, they may assume – perhaps based on experiences in another course – that an in-class exam is open book or that they can collaborate with classmates on a take-home exam, which you may not allow. Preferably, you should articulate these expectations to students before they take the exam as well as in the exam instructions. You also might want to explain in your instructions how fully you want students to answer questions (for example, to specify if you want answers to be written in paragraphs or bullet points or if you want students to show all steps in problem-solving.)

Write instructions that preview the exam.

Students’ test-taking skills may not be very effective, leading them to use their time poorly during an exam. Instructions can prepare students for what they are about to be asked by previewing the format of the exam, including question type and point value (e.g., there will be 10 multiple-choice questions, each worth two points, and two essay questions, each worth 15 points). This helps students use their time more effectively during the exam.

Word questions clearly and simply.

Avoid complex and convoluted sentence constructions, double negatives, and idiomatic language that may be difficult for students, especially international students, to understand. Also, in multiple-choice questions, avoid using absolutes such as “never” or “always,” which can lead to confusion.

Enlist a colleague or TA to read through your exam.

Sometimes instructions or questions that seem perfectly clear to you are not as clear as you believe. Thus, it can be a good idea to ask a colleague or TA to read through (or even take) your exam to make sure everything is clear and unambiguous.

Think about how long it will take students to complete the exam.

When students are under time pressure, they may make mistakes that have nothing to do with the extent of their learning. Thus, unless your goal is to assess how students perform under time pressure, it is important to design exams that can be reasonably completed in the time allotted. One way to determine how long an exam will take students to complete is to take it yourself and allow students triple the time it took you – or reduce the length or difficulty of the exam.

Consider the point value of different question types.

The point value you ascribe to different questions should be in line with their difficulty, as well as the length of time they are likely to take and the importance of the skills they assess. It is not always easy when you are an expert in the field to determine how difficult a question will be for students, so ask yourself: How many subskills are involved? Have students answered questions like this before, or will this be new to them? Are there common traps or misconceptions that students may fall into when answering this question? Needless to say, difficult and complex question types should be assigned higher point values than easier, simpler question types. Similarly, questions that assess pivotal knowledge and skills should be given higher point values than questions that assess less critical knowledge.

Think ahead to how you will score students’ work.

When assigning point values, it is useful to think ahead to how you will score students’ answers. Will you give partial credit if a student gets some elements of an answer right? If so, you might want to break the desired answer into components and decide how many points you would give a student for correctly answering each. Thinking this through in advance can make it considerably easier to assign partial credit when you do the actual grading. For example, if a short answer question involves four discrete components, assigning a point value that is divisible by four makes grading easier.

Creating objective test questions

Creating objective test questions – such as multiple-choice questions – can be difficult, but here are some general rules to remember that complement the strategies in the previous section.

- Write objective test questions so that there is one and only one best answer.

- Word questions clearly and simply, avoiding double negatives, idiomatic language, and absolutes such as “never” or “always.”

- Test only a single idea in each item.

- Make sure wrong answers (distractors) are plausible.

- Incorporate common student errors as distractors.

- Make sure the position of the correct answer (e.g., A, B, C, D) varies randomly from item to item.

- Include from three to five options for each item.

- Make sure the length of response items is roughly the same for each question.

- Keep the length of response items short.

- Make sure there are no grammatical clues to the correct answer (e.g., the use of “a” or “an” can tip the test-taker off to an answer beginning with a vowel or consonant).

- Format the exam so that response options are indented and in column form.

- In multiple choice questions, use positive phrasing in the stem, avoiding words like “not” and “except.” If this is unavoidable, highlight the negative words (e.g., “Which of the following is NOT an example of…?”).

- Avoid overlapping alternatives.

- Avoid using “All of the above” and “None of the above” in responses. (In the case of “All of the above,” students only need to know that two of the options are correct to answer the question. Conversely, students only need to eliminate one response to eliminate “All of the above” as an answer. Similarly, when “None of the above” is used as the correct answer choice, it tests students’ ability to detect incorrect answers, but not whether they know the correct answer.)

CONTACT US to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

- Faculty Support

- Graduate Student Support

- Canvas @ Carnegie Mellon

- Quick Links

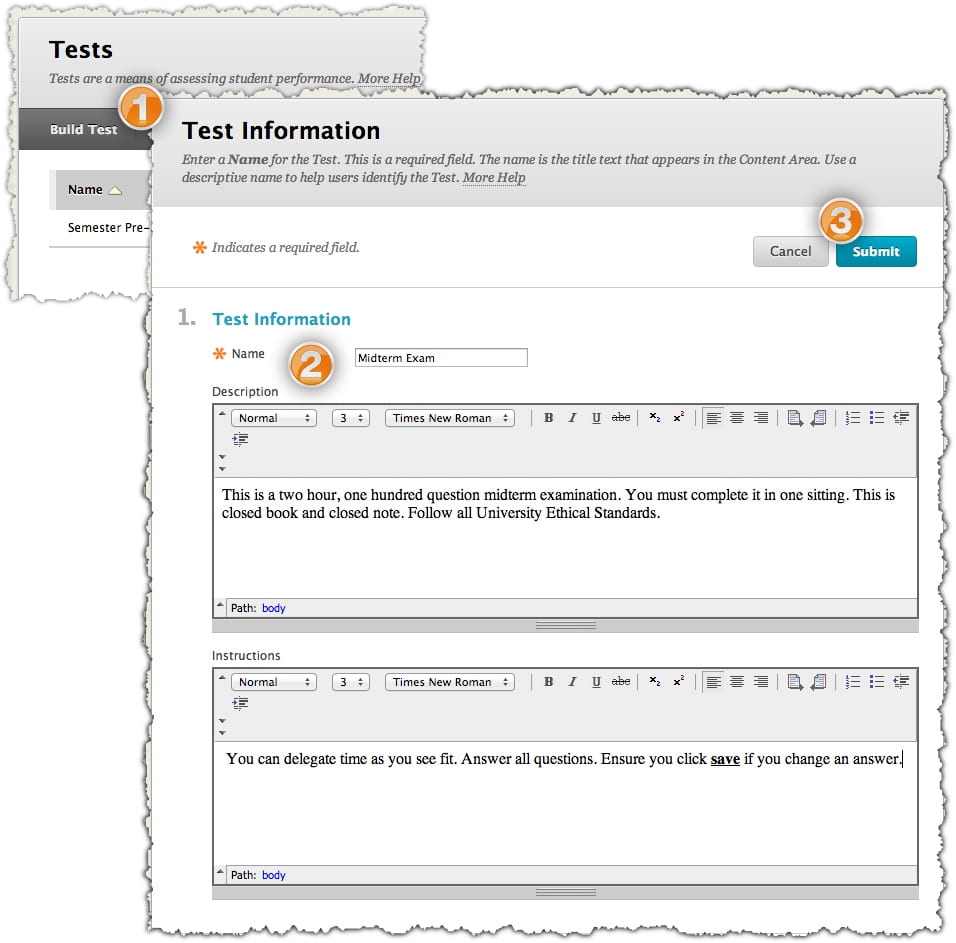

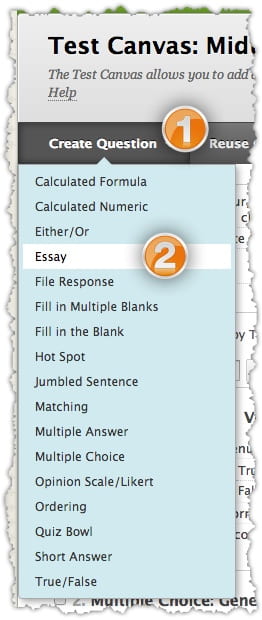

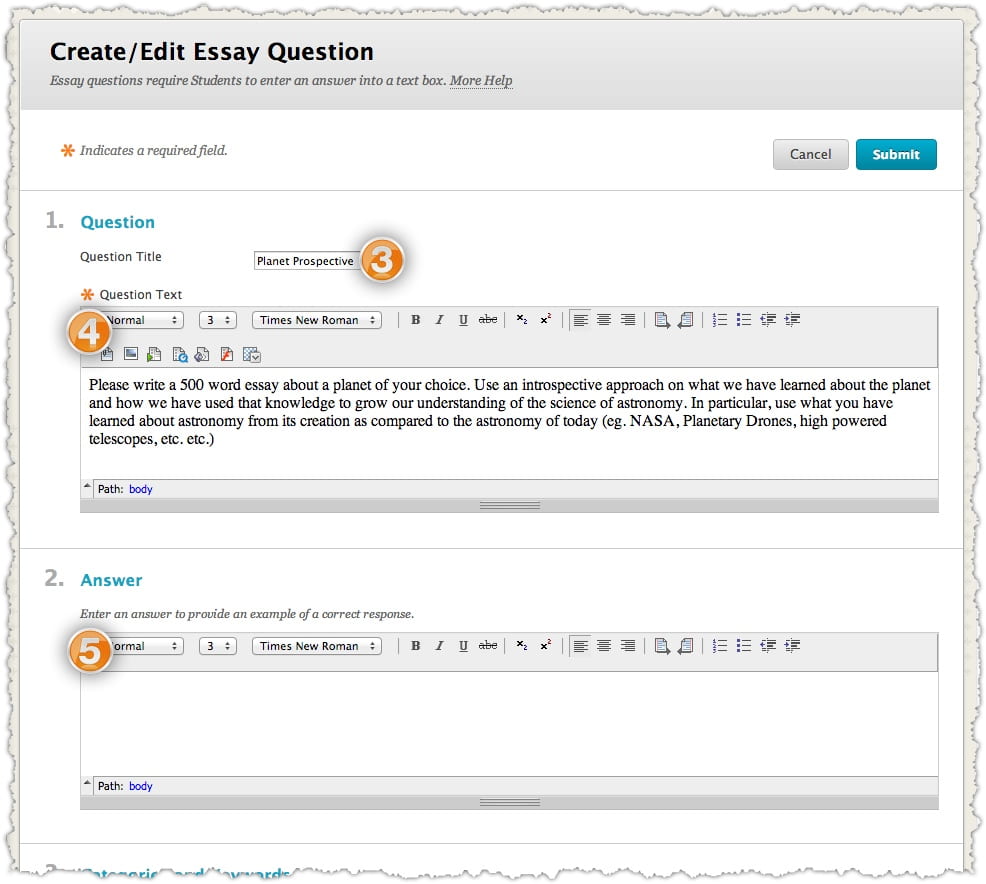

How to Create an Essay Quiz Question

Fri 12th Nov 2021 < Back to Blogs and Tutorials

How to create an essay question:

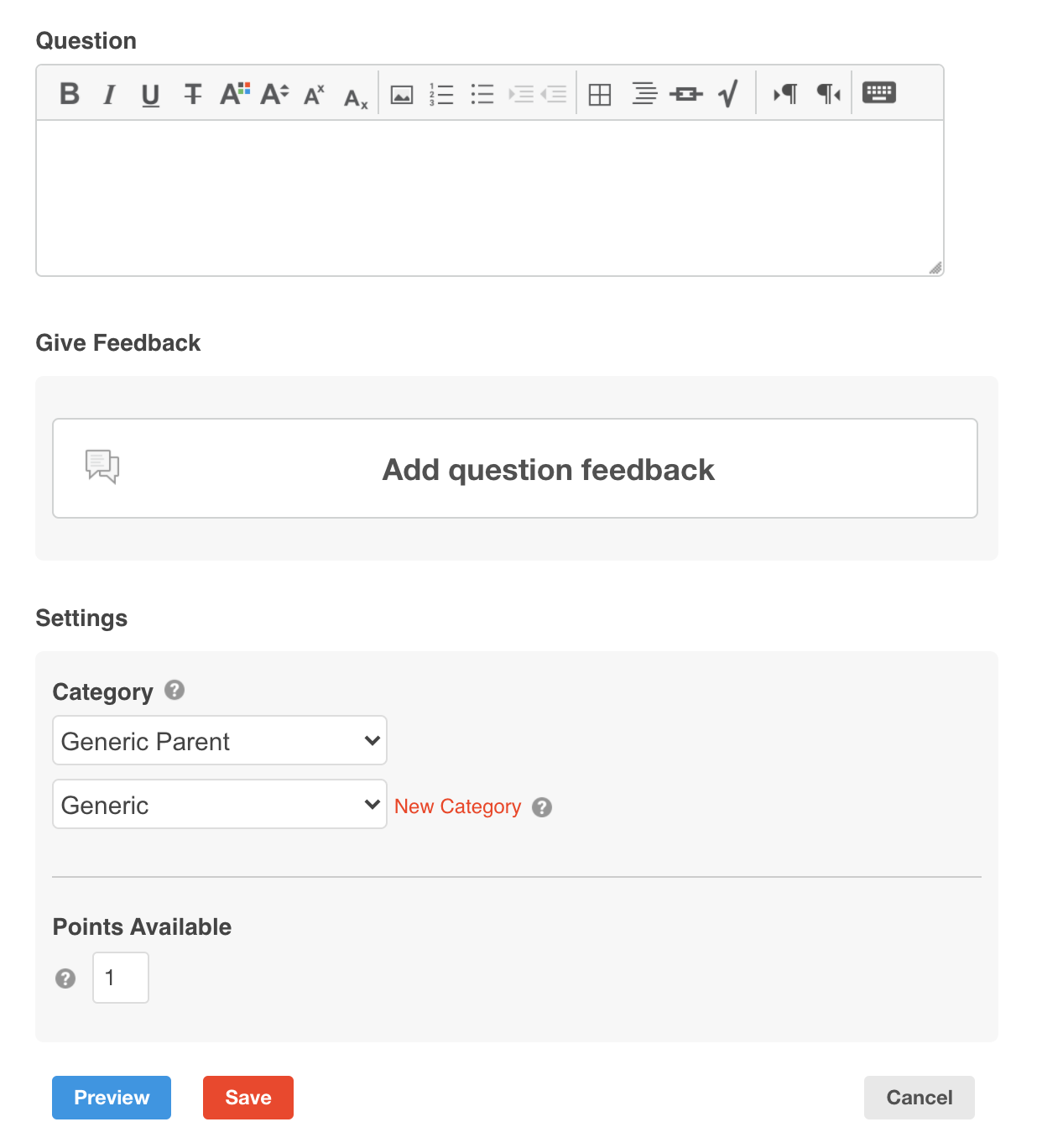

- From the Question Bank page > click on the blue + Add Questions button.

- Click + Add a New Question

- A window will pop up "Where Do You Want to Add your New Questions?" You can choose either a specific Test to add the question into or the Question Bank.

- On the Question 'edit' page > click the Essay tab.

- Enter question text into the question field. You can include text, images, documents, audio, and video.

- Add Question Feedback . Adding feedback is optional. Add customized feedback for both correct and incorrect answers . This feedback will only show on results pages after you have graded the question

- Apply question settings . Choose the question category that the question will go into. Set the point value .

- Click Preview to review your newly created essay question.

- If you need to make any changes, click 'edit'. If everything looks good, click Save .

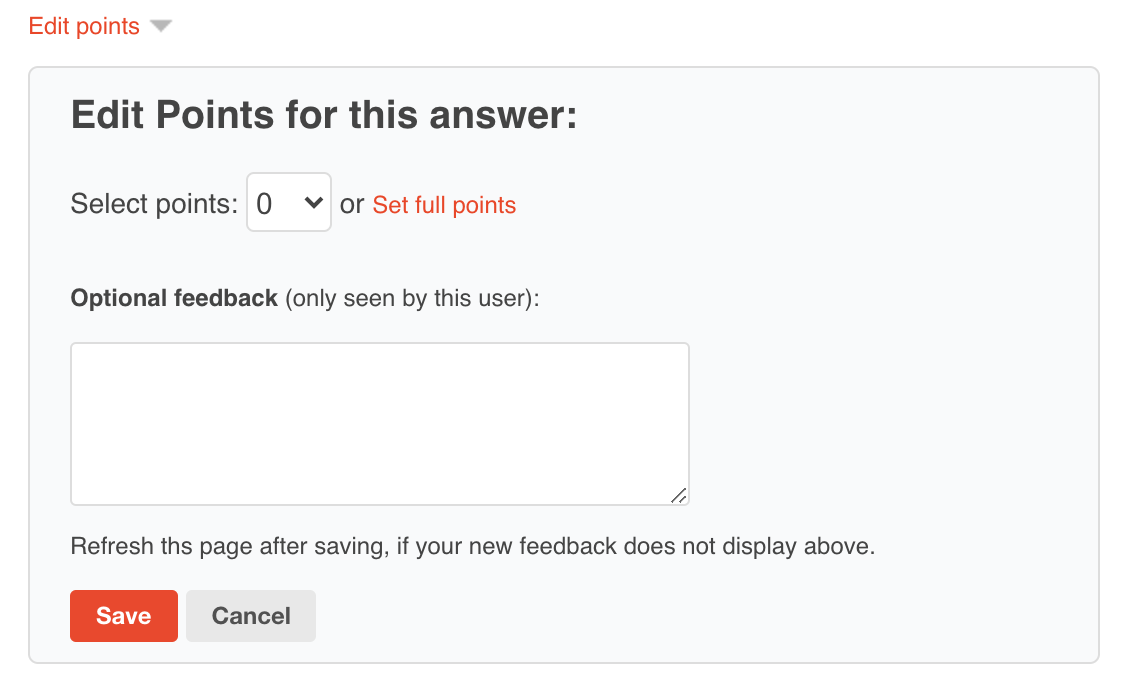

Essay Question Grading:

How do Test-takers receive their graded results?

How do administrators view results for essay answers.

- Administrators and Assistants can view graded quiz results with all answers given on individual user results pages.

- You can export results for groups of users to Excel that can also include all selected answers given per user.

- Have individual results delivered to your email address . Assistants are additional users you can add to your administrator account to assist with tasks within the account, such as assisting with grading of essay questions. You can have up to 4 different administrator/assistant email addresses receive individual Test taker results per each assigned Test.

- Have results sent back to your own system with our quiz webhooks , to include user responses, along with replies to essay questions .

< Back to Blogs and Tutorials

How to Write Better Test Questions (Tips With Examples)

- April 22, 2022

- in Blog , White Paper

With so many types of test questions, which should you use on your online tests?

We’ll show you how to write better test questions and when to use them. Click the bullet below to skip to that section.

- Multiple choice/answer

- Fill-in-the-blank

- Rank-and-order

- Authentic assessment

Multiple-Choice Questions

When to use multiple-choice test questions.

Multiple-choice questions are extremely versatile and can be used for practically any subject and situation, such as:

- Associating & Comparing

- Terms & Definitions

- Problem-solving

- Recalling Concepts & Information

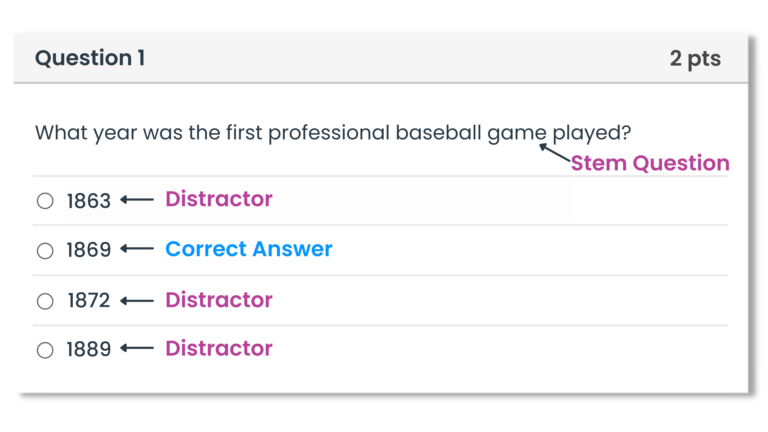

Parts of a multiple-choice question

Tips for writing multiple-choice test questions

- “All of the above” means that a student just needs to identify two of the correct choices to get the answer right.

- “None of the above” doesn’t mean that the student knows the correct answer – just that they can recognize wrong answers.

Answers should be independent of one another, with no overlap.

Less Effective

More Effective

Small mistakes can give away the correct answer, even with no context of the subject.

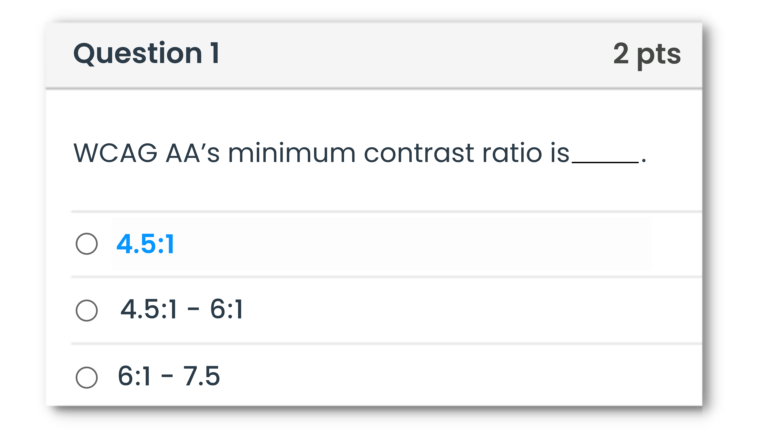

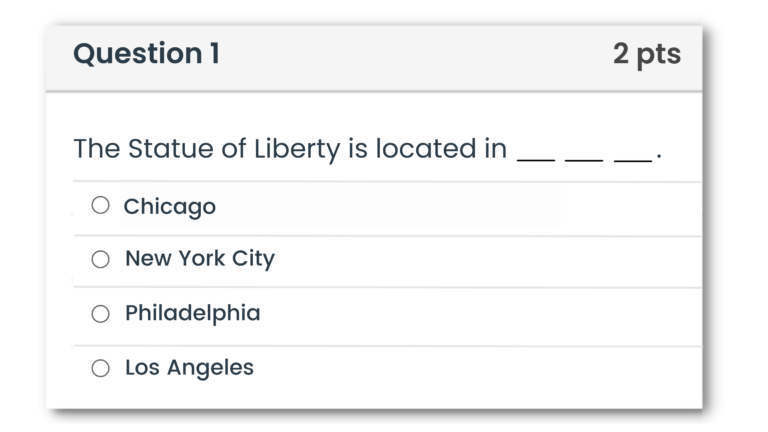

Question Format

The example above includes three lines, which gives away the answer of New York City because the other options are two words or less.

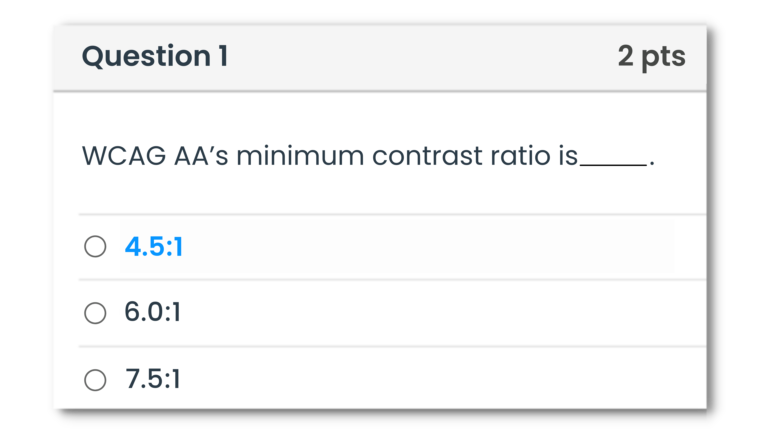

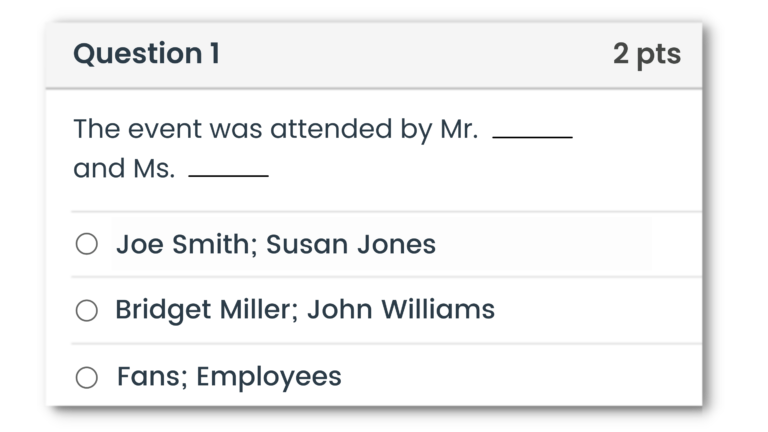

Sentence and Answer Format – Titles

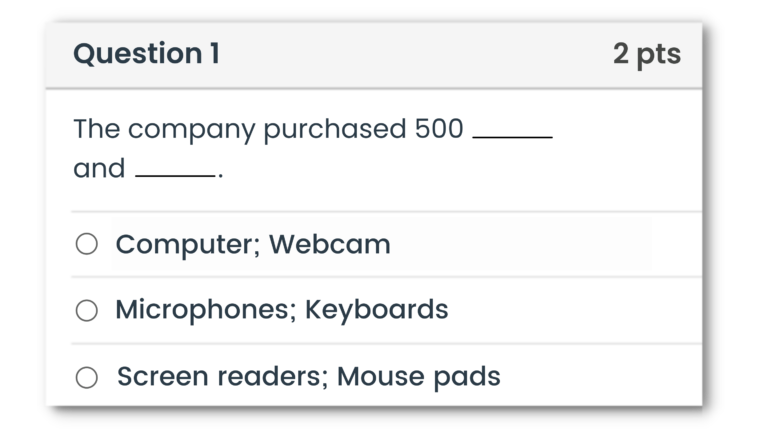

Even with no context of the event or the potential attendees, you can probably guess the correct answer based on the titles before the blanks and the order of the names.

For this question, a simple way to improve it is to remove the title before the blank.

Word Format – Plural and Singular

Since the company purchased 500, that inherently means that the correct answer will be plural, which excludes option A, which is written in a singular format.

Aside from using a consistent plural/singular format for each answer, you could also create answers that account for both singular and plural options: e.g., Computer(s); Webcam(s)

True-or-False Questions

When to use true-or-false test questions.

True-or-false questions may seem simplistic, but when used correctly, they can effectively test in-depth understanding of information through:

- Analyzing items and statements

- Recall of information & concepts

- Surveys & feedback

- Terms & definitions

However, writing true-or-false questions can be tricky because small word choices can change the meaning of a statement.

Tips for writing true-or-false test questions

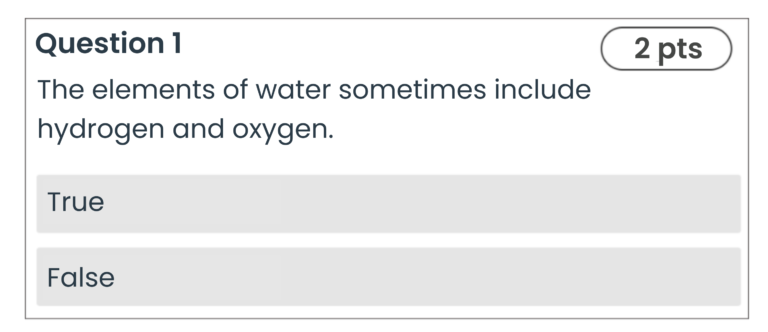

The less effective example implies that water may sometimes include elements other than hydrogen and oxygen.

Modal Verbs

Modal verbs can help describe the possibility, ability, intent, and necessity of a main verb.

Examples of modal verb s: can, may, could, should, would.

Here’s how a modal verb can change a sentence:

- No modal: I run every day.

- With modal: I can run every day.

- The example with no modal states a fact: the person runs every day.

- The example with a modal verb states that the person is capable (can) of running every day, not that they do.

Absolute words

Similar to modal verbs, absolute words can change the meaning of a sentence entirely.

Examples of absolute words: never, always, all, must

Here’s where you have to consider if something is absolutely 100% correct or if it’s just a general statement.

- With absolute: The man never goes running.

- Without absolute: The man rarely goes running.

Which sentence is truly accurate?

Does the man literally never run, or is it just rare that he runs?

Note : Some sentences can include both modal and absolute words, which can cause confusion for the student. e.g .: The man usually never goes running.

Watch for double negatives

Double negatives make a test question confusing for anyone.

Example of a double negative used in a true-or-false statement:

- Less effective statement: The man was not unhappy that the rain stopped.

- More effective statement: The man was happy that the rain stopped.

The less effective example is confusing, right? The first negative word in that sentence is “not” and the second negative is the prefix “un.” When you combine the two negatives, “not unhappy” is canceled out and changes to a positive.

Fill-in-the-blank Questions

Fill-in-the-blank test questions provide an objective way to measure true understanding of the answer rather than recognizing the answer to a multiple-choice question when they see it.

When to use fill-in-the-blank questions

- Recalling concepts & information

Tips for writing fill-in-the-blank questions

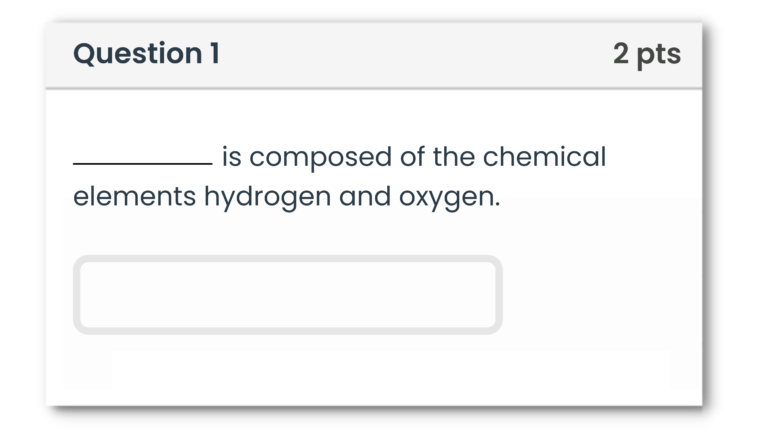

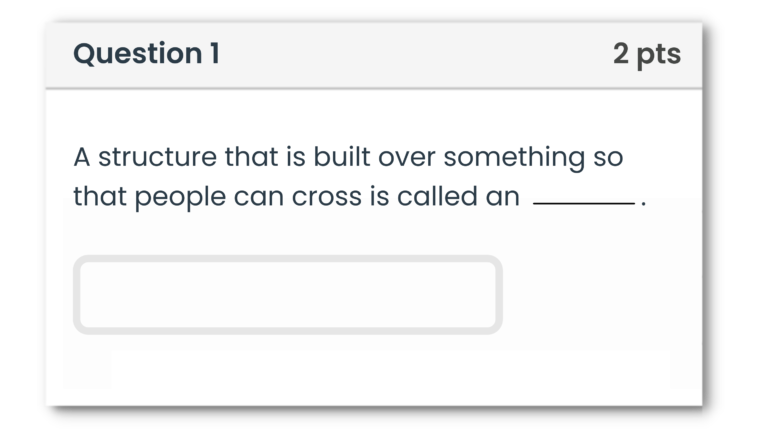

Don’t start a statement with a blank.

Blanks should be included toward the end of the statement instead of the beginning.

Make sure the statement and answer grammatically align

Written Test Questions

Written test questions can be more time-consuming to review, but they’re an effective way to allow students to expand their thoughts and tie-in other concepts.

When to use written test questions

- Associating & comparing

- Student feedback

Tips for better written test questions

Intentionally frame your questions based on the goal

- Less effective: “Discuss the benefits of process-improvement methodologies”

- More effective: “Compare the benefits of Six Sigma and Agile to determine which methodology is the best option for a software company.”

Words to help frame the purpose of your essay question:

- Group/Classify/Categorize

- Compare and contrast

- In your own words, define

- List five ways to

Words and phrases to avoid when creating an essay question:

- Speak to/about

Use blind grading (anonymous grading) Blind grading, sometimes called anonymous grading, can help remove grading bias because students submit their tests without a name or number. You can set this up in most modern LMSes by turning on anonymous grading at the course level. Doing so will hide the students’ names before grading and automatically distribute the test score back to them.

For longer essay questions, focus on broad topics

Instead of focusing on one specific item for a longer written response, focus on larger topics. This approach allows students to demonstrate complex understanding by associating items across a broad range of topics.

Provide the same questions to all students

Instead of listing four essay questions and requiring students to answer two, just provide two questions. This approach helps consistently measure student performance and ensure fairness during grading.

Set expectations and prepare students

Good response vs poor response

Give examples of what makes a good response or poor response. What aspects should be addressed? What can make or break an answer?

Technical information

Give students context about time limits, general response length, how to get support, etc.

Detail the formatting expectations

Typed responses : Tell students what fonts should be used, which processor (Word Doc, Google Docs, etc.), what font types to use, font sizes, and line spacing.

Hand-written response s: Tell students what type of paper to use, pen color, and any other details that will help ensure that they’re on track.

Did you know you can use online proctoring for hand-written test questions?

Instructors can provide instructions to the remote proctor to allow students to use a pen and paper. You can even require that students show their work at certain intervals throughout their response.

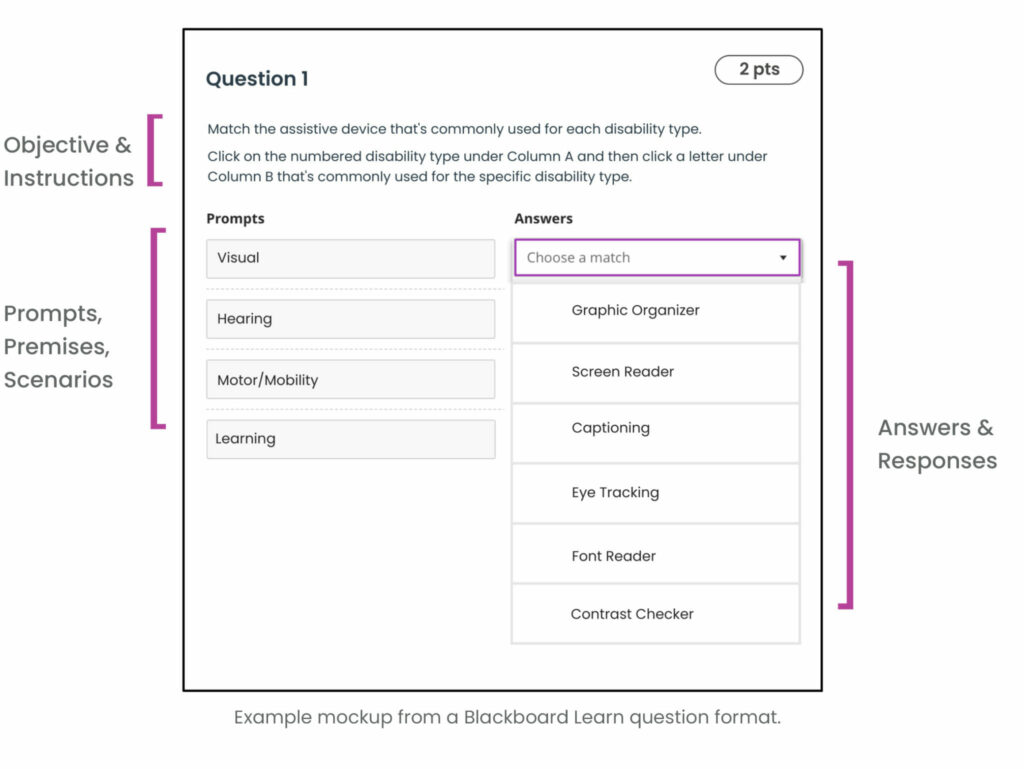

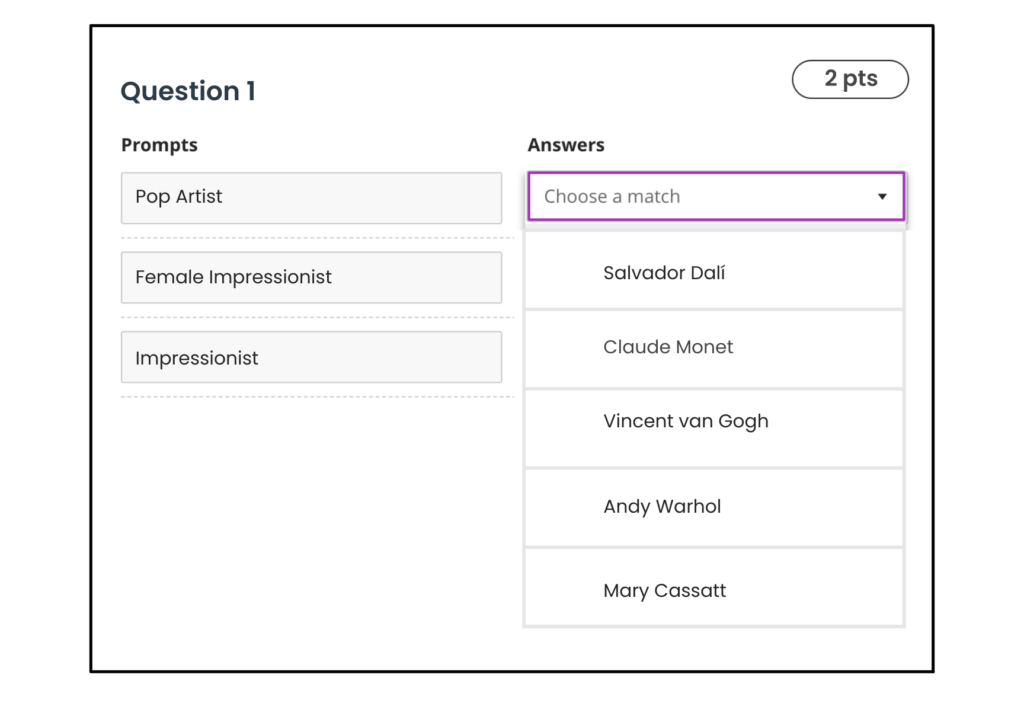

Matching Test Questions

Matching test questions are an effective way to test knowledge in a variety of scenarios that cover a large amount of content.

- Terms and definitions

- Scenarios and responses

- Causes and effects

- Parts and functions

Layout example:

Include more answers than prompts

Using more answers than prompts removes the ability for students to answer by process of elimination.

Structure and format shouldn’t give away the answer

Avoiding this problem can be especially tricky in matching-test questions. In the example below, number two is relatively easy to guess because the answer includes the first name. Resolve by removing “female” from number two and/or removing the first names from the answers.

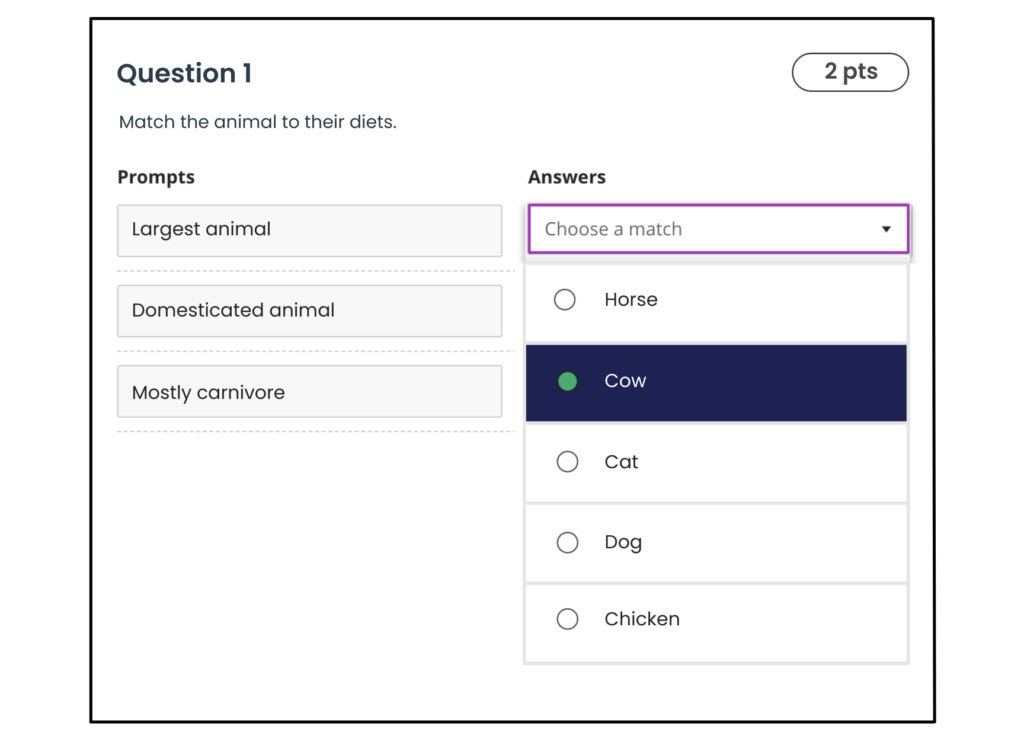

Prompts/answers shouldn’t be vague

In the example below, you can see that in the less effective example, the prompts are vague and most answers could apply to a few different prompts.

- Largest animal on the farm: This question comes down to a cow or a horse. But what type? That impacts the answer.

- Domesticated animal: The go-to responses are both dogs and cats, but some people consider any farm animal “domesticated.”

- Mostly carnivore: Again, the go-to responses are both dogs and cats, but pigs can also consume mostly meat.

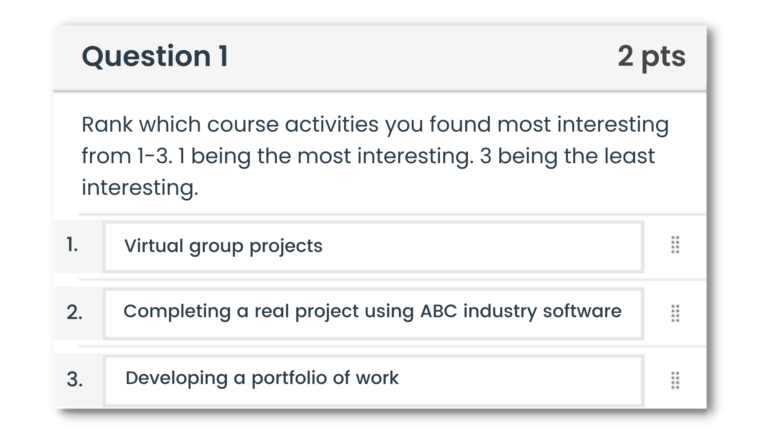

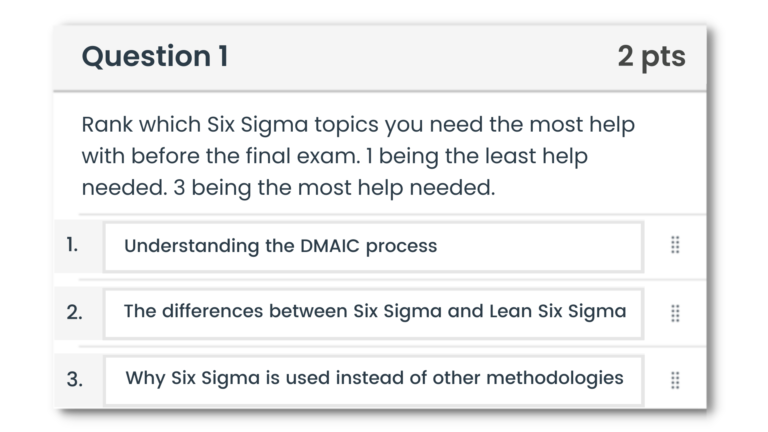

Rank-and-Order Questions

These questions ask students to rank or order a list of items based on chronological order of dates, steps, or level of importance. They’re especially dynamic because students can respond in a few ways that combine with other question types, such as the student dragging and dropping numbers into the correct order or matching a step with the correct order.

- Chronological order of events

- Steps to complete a task

- Understanding the importance of an item

Keep questions and items on the list focused

If a student has to chronologically order 15 historical events, they may get overwhelmed before they even start.

Instead, divide the 15 events into three sets of five events.

Give context about what’s highest or lowest, first or last, best or worst, most important or least important.

- Less effective: Rank the importance of work-life balance from 1-10.

- More effective: Rank the importance of work-life balance according to the survey from the ABC Company case study. 1 is the most important ranking. 10 is the least important.

Tip: Use ranking questions as a tool to gather student feedback

You can use them to gather general course feedback or provide very specific questions based on activities.

General Rank Question

Specific-Activity Question

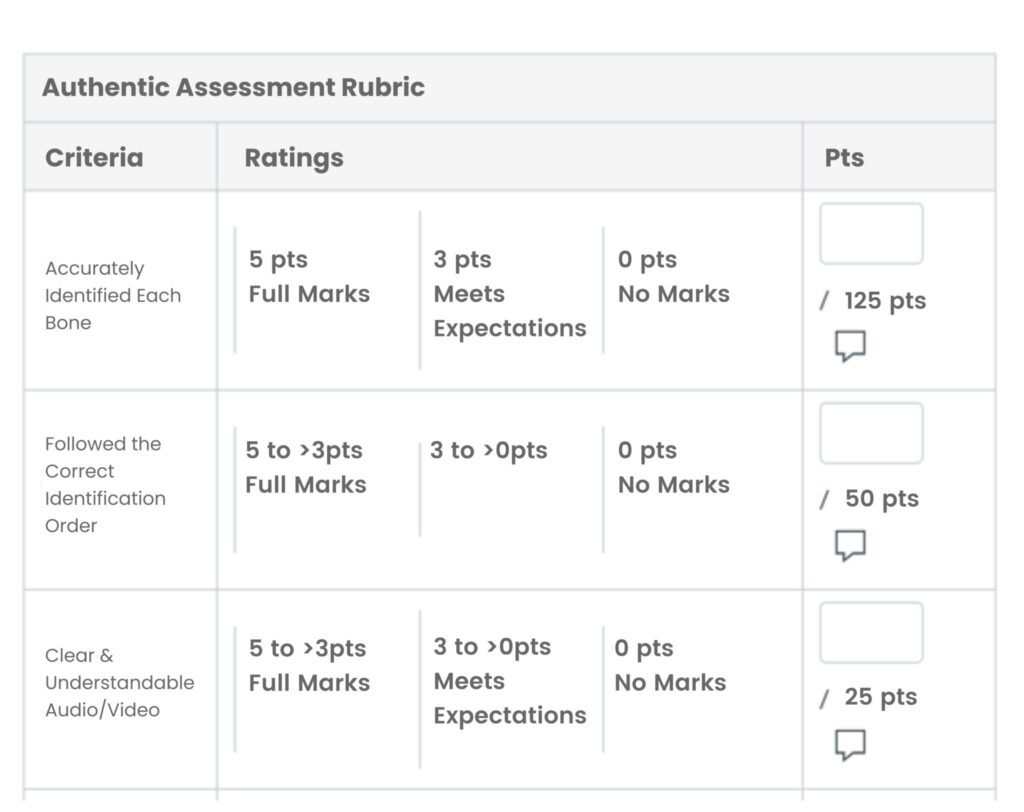

Authentic Assessment

Authentic assessment is becoming increasingly popular because, rather than simply recalling information, students are actually completing real-world tasks and activities that demonstrate their knowledge and expertise.

- Virtual presentations and demonstrations using a webcam

- Completing a project using industry software

- Creating a portfolio of work

- Game-based activities

- Course participation in debates and discussions

- Write a 1-2 sentence summary that identifies the key objectives of the assessment

Divide the summary sentence into separate parts