How the “Barbie” Movie Explains the Psychology of Patriarchy

Is patriarchy a toxic response to the discomfort of being human.

Posted August 21, 2023 | Reviewed by Davia Sills

- "Barbie" is an allegory of the rise of patriarchy.

- The film criticizes Mattel's patriarchal vision of female empowerment.

- "Barbie" is optimistic about our ability to refashion our world.

The Barbie movie begins with a parodic nod to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey , where in the opening scene, the appearance of a black obelisk signals a milestone in the evolution of humankind—violence enters the community of peaceful apes who will now evolve into homo sapiens . In Barbie , the obelisk is replaced by Barbie (whose legs are equally monumental) and the apes by little girls who destroy their baby dolls; a new era in play has begun. This comic moment points to the different levels at which Greta Gerwig’s brilliant movie signifies: It’s a movie about dolls, to be sure, but also a movie about evolution, not simply that of dolls and play but also about the rise and endurance of patriarchy, seen through the lens of psychology.

The term “patriarchy” has been criticized for failing to acknowledge the oppression and injustice that exist within male identities. The film acknowledges this criticism when Aaron, the low-ranked administrator at Mattel, says, “I’m a man without power. Does that make me a woman?” But patriarchy is nevertheless grounded in gender , as bell hooks, who is well aware of identity -based power differentials, maintains: “Patriarchy is a political-social system that insists that males are inherently dominating, superior to everything and everyone deemed weak, especially females. ”

Barbie was created by Ruth Handler, a woman who defied the gender roles and restrictions of her time but who nevertheless designed a doll in which a limiting, oppressive ideal of female beauty prevails and whose character is all about her clothes and her body (see my essay “Barbie’s Body Project”).

Barbie’s impossible proportions advocate beauty standards (thinness above all) notorious for being internalized to the detriment of self-esteem and self-acceptance on the part of girls and women. Barbie’s feet make it impossible to move freely, from an attacker, or just to function. The first sign that there is a breach of boundaries between Barbieland and the Real World is that Barbie’s feet get flat; when she wears heels in this condition, she comments, “I would never wear heels if my feet were shaped like this.”

Let’s not be too hard on Handler; it was 1959, and in any case, as Gloria points out—she’s the Real World woman who caused the breach by imagining a line of Barbies in crisis—women internalize patriarchal ideals. The primarily male executives who ran Mattel after Handler elaborated on this inherent bias . Although women rule in Barbieland, it nevertheless embodies a patriarchal vision of a feminist universe since feminist theories do not advocate a simplistic reversal of privilege in which someone is still oppressed and disempowered. And with a few exceptions that aim at inclusiveness, the Barbies still look like Barbie.

The Kens of Barbieland are “women.” Ken #1 lives in a world where “Barbie has a great day every day, but Ken only has a great day if Barbie looks at him” (a description eerily reminiscent of abusive relationships). Ken lives in a psychological state of lack, a “life of blond fragility” where it “doesn’t seem to matter what I do/I’m always number two,” and where being second is tantamount to being nothing.

Barbie cruelly dismisses him; “every night is girl’s night,” to which he is pointedly not invited. He exists to partner with Barbie, and one of the happy outcomes of the film is that he learns to search for his identity apart from his persona as “and Ken,” as in “Barbie and Ken .” This secondary status, epitomized by Ken #1, accounts for the competition between the Kens, which exists from the start of the film. Humans compete when resources are scarce, the resources, in this case, being love, status, and recognition.

Sent off to entertain himself while Barbie tries to locate the source of the breach, Ken goes to Century City, where he discovers a world in which men rule. Barbie observes, “It’s almost like reverse here.” He acquires some simplistic ideas about patriarchy; in the Real World, it isn’t all that involved with horses and mini-fridges. But he understands its fundamental principles, and Gerwig makes it clear that they rule our world as well.

On her return to Barbieland, Barbie finds that Ken is in the process of turning it into a Kendom, thereby acquiring the respect and importance that he has lacked. And there’s an element of revenge as well, captured by one of his favorite songs, "Push" by Matchbox Twenty, with the signature line “I want to push you around.” Barbie finds that the Barbies have been brainwashed into supporting the patriarchal order of things, a comment on what happens to women in the real world (Handler and Barbie’s body come to mind). With the help of Gloria, Barbie figures out that the way to deprogram the Barbies is by stating the contradictions within patriarchal expectations for women. Barbie, who is becoming increasingly astute as well as human, observes, “By giving voice to the cognitive dissonance of living under patriarchy, you robbed it of its power.”

The Barbies trick the Kens into missing the vote to change the constitution that would make Barbieland into a Kendom by using competition between the Kens to provoke a battle. The battle is a comic fest (catch the guy giving mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to his hobbyhorse) that suddenly transforms into a brilliantly choreographed dance number; Gerwig was inspired by musicals of the 1940s. The transformation has meaning as well as spectacle, allegorizing the posturing—literal posturing through dance moves—and display so germane to patriarchy.

In case you miss the point about the psychology of patriarchy, it’s stated overtly but subtly in an almost throwaway line by Handler, who guides Barbie through her decision to become human. (This movie offers a wonderful rendition of the trope of “becoming human,” seen in characters like Pinocchio, the Tin Woodman ( Wizard of Oz ), and Data ( Star Trek: The Next Generation .) Handler tells her that being human has its drawbacks. For one, you die: “Ideas live forever. Humans, not so much.” And “being a human can be pretty uncomfortable. Humans make up things like patriarchy and Barbie to deal with how uncomfortable it is.”

There’s the moral of the movie: We find both terrible and creative ways to deal with the inevitable lack and the awareness of that lack that come with being human. Handler also suggests that patriarchy is not biological or inevitable for humans, a counter-argument to a widely accepted belief (see works by Grenta Lerner and Angela Saini). Humans make up things, like patriarchy and Barbie. And what is made can be unmade. Maybe we’ll see “Ordinary Barbie” after all!

hooks, b (2004). The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love . Washington Square Press.

Jones, W. Barbie's Body Project (1999). In Y. Z McDonough (Ed.). The Barbie Chronicles: A Living Doll Turns Forty (91-107). Touchstone Press.

Gerder, Lerner (1987). The Creation of Patriarchy . Oxford University Press.

Saini, Angela (2023). The Patriarchs: The Origins of Inequality . Beacon Press.

Wendy Jones, Ph.D. , a practicing psychotherapist and former English professor, is the author of J ane on the Brain: Exploring the Science of Social Intelligence with Jane Austen .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Support Group

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Overcome burnout, your burdens, and that endless to-do list.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Teaching Barbie: Scholarly Readings to Inspire Classroom Discussion

Barbie is having a(nother) moment. Researchers have been studying the famous doll for years.

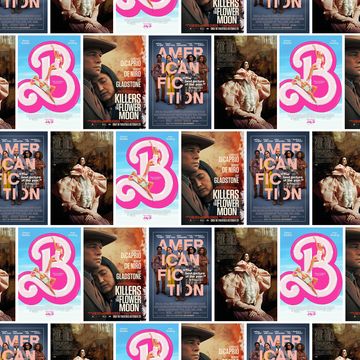

Since she was created in 1959, Mattel’s Barbie doll and her descendants have been fodder for feminist researchers, sociologists, gender theorists, and other academics. As we all probably know by now, the doll was invented by Ruth Handler, who noticed her daughter Barbara playing with paper dolls and giving them adult narratives and roles. At the time, most dolls looked like infants, but Handler saw a gap in the market for adult dolls for girls, and the rest is Barbie history. Initially a teen fashion doll, Barbie has gone through six decades of transformations and rebranding , becoming a cultural icon over the years and appearing as an astronaut, doctor, physicist, and just about any other professional you can think of.

Girlhood, Gender, and Sexuality

Linda Wason-Ellam. “ ‘If Only I Was Like Barbie.’ ” Language Arts , vol. 74, no. 6, 1997, pp. 430–37.

It’s impossible to understand Barbie without acknowledging the toy plays a big part in young girls’ construction of their sense of self. This ethnographic study investigates how young girls construct gendered identities and meanings through exchanges between visual and written texts, including Mattel’s book version of Cinderella, where Barbie takes on the titular role.

Catherine Driscoll. “ CHAPTER FOURTEEN: Girl-Doll: Barbie as Puberty Manual. ” Counterpoints , vol. 245, 2005, pp. 224–41.

Bringing together two relevant cultural texts for pre-adolescent girls, Catherine Driscoll considers dominant gender discourses through analyses of Barbie dolls and puberty manuals in the early 2000s as influential manifestations of the “tween” space in public and popular representations of girlhood.

Claudia Mitchell. “ Charting Girlhood Studies .” Girlhood and the Politics of Place , edited by Claudia Mitchell and Carrie Rentschler, Berghahn Books, 2016, pp. 87–103.

A good summary of what has been accomplished or found so far in girlhood studies, which has often drawn on how girls understand gender and power dynamics through playing with Barbie.

Louise Collins, et al. “ We’re Not Barbie Girls: Tweens Transform a Feminine Icon. ” Feminist Formations , vol. 24, no. 1, 2012, pp. 102–26.

Based on the insights collected from a research workshop for middle-school girls, this article asks what girls feel, think, and hope when playing with Barbie. Drawing on the insights middle-school girls delivered when discussing and reflecting on the constructions of female bodies and feminine identities in popular culture, Collins et al suggest that consumers are not simply vessels for consumption—they can be critical engagers of the products they consume.

Michael A. Messner “ Barbie Girls versus Sea Monsters: Children Constructing Gender .” Gender and Society, vol. 14, no. 6, 2000, pp. 765–84.

How do toys help children make meaning of gender? In this article, Michael A. Messner examines this question through an analysis of children’s interactions with pop culture.

Anna Wagner-Ott. “ Analysis of Gender Identity Through Doll and Action Figure Politics in Art Education .” Studies in Art Education, vol. 43, no. 3, 2002, pp. 246–63.

Using action figures and dolls as pedagogical tools, this article explores how art educators can engage young people in a critical dialogue to uncover preconceived ideas, attitudes, and values inherent in gendered objects.

Becky Francis. “ Gender, Toys and Learning .” Oxford Review of Education, vol. 36, no. 3, 2010, pp. 325–44.

Drawing on the claim that children learn gender through playing, Becky Francis conducts evaluated selected toys—including some Barbie accessories—to identify the gender discourses reflected in the children’s choice of toys.

Whiteness and Race

Maureen Trudelle Schwarz. “ Native American Barbie: The Marketing of Euro-American Desires. ” American Studies , vol. 46, no. 3/4, 2005, pp. 295–326.

A particular concern of Barbie critics is the brand’s focus on and centering of whiteness, which the brand has addressed through the creation of ethnically diverse versions of the doll. In this in-depth analysis of Native American Barbie dolls and what they teach girls—and society more broadly—about Native American cultures in the United States, author Maureen Trudelle Schwarz argues that Barbie sanitizes the horrors of colonialism and Indigenous oppression.

Elizabeth Chin. “ Ethnically Correct Dolls: Toying with the Race Industry .” American Anthropologist, vol. 101, no. 2, 1999, pp. 305–21.

Examining the claim that providing more diverse toys is a progressive solution to white hegemony, this anthropological study with a group of working class, Black ten-year-old children complicates the politics of representation and inclusion.

Nina Cartier. “ Black Women On-Screen as Future Texts: A New Look at Black Pop Culture Representations. ” Cinema Journal, vol. 53, no. 4, 2014, pp. 150–57.

In this article, Nina Cartier offers a short but important critique of Nicki Minaj’s Black Barbie, along with other representations of Black womanhood onscreen.

Margaret Hunter and Alhelí Cuenca. “ Nicki Minaj and the Changing Politics of Hip-Hop: Real Blackness, Real Bodies, Real Feminism? ” Feminist Formations, vol. 29, no. 2, 2017, pp. 26–46.

Examining Nicki Minaj’s body of work, particularly her embodiment of her Black Barbie persona, the authors argue that Minaj’s offers a brand of feminism that is highly marketable because it merges a language of critique and oppression.

Okafor, Chinyere G. “ Global Encounters: ‘Barbie’ in Nigerian Agbogho-Mmuo Mask Context. ” Journal of African Cultural Studies , vol. 19, no. 1, 2007, pp. 37–54.

Beyond being an American doll, the product of Barbie was exported across the world, thus spreading its message across borders. In this article, Chinyere G. Okafor writes about the doll’s impact on Nigerian beauty standards through the image of the Agbogho-mmuo mask of the Igbo ethnic group. The encounter between these two beauty standards is the site of a global image-making network, the author suggests, and its discussion allows for an analysis of the globally empowered Barbie doll and her impact on Nigerian culture.

Marketing Barbie

Marlys Pearson and Paul R. Mullins. “ Domesticating Barbie: An Archaeology of Barbie Material Culture and Domestic Ideology. ” International Journal of Historical Archaeology , vol. 3, no. 4, 1999, pp. 225–59.

Drawing on the history of Barbie since the 1950s and the distinct “single career girl” marketing strategy employed by Mattel, the authors of this article offer a systematic examination of Barbie fashions, accessories, and playsets, which they argue reveals several distinct phases in the domestic symbolism associated with the doll. By tracing the history of Barbie accessories, the authors are able to pinpoint changes in Barbie’s domestic image over the last 40 years.

Erica Rand. “ Making Barbie. ” Barbie’s Queer Accessories , Duke University Press, 1995, pp. 23–92.

Delving deep into the history of Barbie and Mattel’s uneven and deflecting history around the character, Erica Rand writes about the erasure of Ruth Handler from the history of the doll’s creation by Mattel (something that has been curiously rectified in Gerwig’s film) and the gender meanings made by the company that invented Barbie.

Postfeminism, Pop-feminism, and Other Critical Lenses for Classroom Discussions of Barbie

Rosalind Gill. 2007. “ Postfeminist Media Culture: Elements of a Sensibility .” European Journal of Cultural Studies 10 (2): 147–166.

To understand the complexity of Barbie, it’s important to understand the existence of postfeminism and how it manifests through media culture. In this article, Rosalind Gill suggests a few approaches to engaging with postfeminist pop culture in critical and feminist ways.

Jess Butler. “ For White Girls Only? Postfeminism and the Politics of Inclusion. ” Feminist Formations , vol. 25, no. 1, 2013, pp. 35–58.

In this article, Jess Butler delves into the lack of intersectional perspectives in the literature on postfeminism, which she argues privileges a white, middle-class heterosexual subject. By drawing on the image of pop star Nicki Minaj, Butler suggests an intersectional approach to producing knowledge about postfeminism.

Angela McRobbie. “ Postfeminism and Popular Culture: BRIDGET JONES AND THE NEW GENDER REGIME. ” Interrogating Postfeminism: Gender and the Politics of Popular Culture , edited by Yvonne Tasker and Diane Negra, Duke University Press, 2007, pp. 27–39.

In this article, Angela McRobbie analyzes the postfeminist messages of the Bridget Jones franchise to emphasize the “double entanglement” of being a woman, where a productive home and work life are desirable to complete a modern woman’s life.

Alice Leppert. “‘ Can I Please Give You Some Advice?’ ‘Clueless’ and the Teen Makeover .” Cinema Journal , vol. 53, no. 3, 2014, pp. 131–37.

While we probably won’t have to wait that long for academic critical engagements with Gerwig’s Barbie, reading critiques of similar films might help us think about it critically. In this article, Alice Leppert analyzes a common trope in teen films through the film Clueless: the teen makeover that makes the unpopular nerd into a popular girl.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

Shauna Pomerantz et al. “ GIRLS RUN THE WORLD? Caught between Sexism and Postfeminism in School. ” Gender and Society , vol. 27, no. 2, 2013, pp. 185–207.

A study on how teenage girls understand sexism in a society that teaches them that gender is no longer a question of concern. By exploring Canadian girls’ experience with the postfeminist belief that sexism doesn’t exist, the authors suggest that postfeminist narratives make it difficult for teenage girls to identify and name gender discrimination.

Carrie Smith Smith and Maria Stehle. “ Popfeminism. ” The German Quarterly , vol. 91, no. 2, 2018, pp. 216–27.

In this short article, the authors define the concept of “pop feminism” in a capitalist society, a critical perspective to understand Barbie as part of a postfeminist, neoliberal system of power and hierarchies.

Michelle S. Bae. “ Interrogating Girl Power: Girlhood, Popular Media, and Postfeminism. ” Visual Arts Research , vol. 37, no. 2, 2011, pp. 28–40.

Challenging the usual critiques of girl power, Michelle S. Bae offers an alternative approach for interpreting the concept — which directly implicates Barbie and the toy’s history with women’s empowerment. Understanding that the dominant discourse on girl power is still located in an essentialist frame of white Western hegemony, Bae uses the original criticisms of girl power as a starting point for arguing that girl power might be interpreted as subversive to patriarchy and are marked by contradictions.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our new membership program on Patreon today.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

A Body in the Bog

A Mughal Mosque in Kenya

Do You Own Your Body?

Jain Ascetics in a Material World

Recent posts.

- Marbled Money

- Earth Isn’t the Only Planet With Seasons

- Up the Junction: A Place, A Fiction, A Film, A Condition

- Dragon Swallows the Sun: Predicting Eclipses in China

- Mobile People, Asteroid Fighters, and Frank Oppenheimer

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

The Brains behind Barbie

What the papers of Ruth Handler can tell us about her creation.

I didn’t grow up playing with Barbies. The one childhood Barbie memory I do have involved her decapitation.

Suffice to say I wasn’t anticipating the release of the new Barbie movie with the fervor it seemed everyone else was (Google launching pink fireworks every time someone searches for “Barbie,” “Margot Robbie,” or “Ryan Gosling” gives the impression that this movie is a major historic event). However, after doing further research, I’ve revised my evaluation of the movie—and of the plastic bombshell.

Depending on who you talk to, Barbie evokes strong reactions ranging from admiration to disgust (or in my case, violence). But whether provoking angst or love, Barbie is a superstar almost everyone knows. How did this toy achieve mythic proportions? What does it take to create such a cultural phenomenon?

The 35th Anniversary Barbie doll is the first ever special edition vinyl reproduction of the original 1959 Barbie doll (1961–1996). ©Mattel, Inc. Courtesy of Schlesinger Library

A good place to start answering these questions is the Ruth Handler Papers at Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library. Handler cofounded Mattel, Inc ., in 1945 with her husband, Elliot, and their friend Harold Mattson. She was later the brains behind the concept for Barbie.

We asked Jane Kamensky, the Pforzheimer Foundation Director of the Schlesinger Library, and Jenny Gotwals, curator for gender and society at the Schlesinger, if they could shed some light on Handler’s life and her inspiration for Barbie.

Personal papers are a unique form of documentation because most of us don’t keep items based on the assumption that they will one day be donated to a library. Consequently, what people choose to save says a lot about them.

Gotwals noted Handler’s papers consist mainly of business records for her various ventures, including Mattel and Nearly Me , a company started by Handler after her own breast cancer diagnosis to sell breast prosthetics and other products for women who have had mastectomies.

Ruth Handler promoting her "Nearly Me" product line (1977–1996). Photo by Allan Grant. Courtesy of Schlesinger Library

Archivists at the Schlesinger Library first contacted Handler around 1999 about the possibility of donating her papers because the Library was focused on building its collections related to women in business. After the launch of the Barbie doll in 1959, Handler became a prominent business leader and national celebrity—one of few successful female entrepreneurs in the 1960s and early ’70s. She was even invited to a White House conference on youth and to a state dinner with the president of Israel, says Gotwals. And she travelled around giving speeches about consumerism and other topics.

Copies of Handler’s correspondence with national business leaders and politicians, as well as her speeches, may be found in the collection at the Schlesinger. The collection also includes photographs of Handler and her family, marketing materials, and page-after-notebook-page of Barbie fan mail. Lamentably for collectors, there are no dolls. One interesting piece of the collection is a receipt for a Bild Lilli doll , the German fashion doll that was one source of inspiration for Handler in creating Barbie.

The daughter of Polish immigrants, Handler did not grow up wealthy . Yet one of the reasons Mattel was so successful is that Handler was a “genius marketer,” says Gotwals. “She created the doll at a time when there was a huge market for it.” Handler was also one of the first to sponsor children’s TV shows, including the Mickey Mouse Club, as a means of marketing toys directly to children, Gotwals noted.

“It’s no accident that so much of Barbie’s dreamscape involves cars and campers. Her rise was part of a vision of a boundless postwar prosperity,” says Kamensky, who is also the Jonathan Trumbull Professor of American History in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Barbie was conceived during a time when plastics were gaining importance as a new material, consumerism was embraced as a source of pleasure and social cohesion, and there was a large generation of children who had parents with disposable income, she added.

Kamensky also noted that the 1960s was the era of the Sexual Revolution , when conversations about intimate life began to change with the introduction of the first birth control pill, in 1960, and the publication of Helen Gurley Brown’s Sex and the Single Girl , in 1962 . “With her body-conscious fashions, Barbie incarnated a kind of liberation: the freedom to say yes . As feminists pointed out beginning in the late ’60s,” said Kamensky, “that freedom sometimes threatened to erase the right to say no. ”

Handler certainly knew how to time a product launch.

Above all, what Handler’s papers reveal about her is that she was a savvy businesswoman with ambitions. “She did not enjoy being what we would now call a stay-at-home mother . . . she was pretty upfront about that,” says Gotwals. “She was really invested in being creative and in being involved in business, even from a young age.”

So whether you love or hate Barbie, her real story is as much about brains as it is about beauty.

Sam Zuniga-Levy is a writer at Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

Read the complete interview with Jane Kamensky.

News & Ideas

Episode 203: Is Losing an Hour of Sleep Really That Big a Deal?

Episode 202: A Conversation with Sherrilyn Ifill

Episode 201: Riding the Radcliffe Wave

Student Spotlight: Justis Gordon ’24

Erika Lee Appointed Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation Faculty Director of Schlesinger Library

Episode 111: Free Speech, Political Speech, and Hate Speech on Campus

Episode 110: The Thrill of Archival Discovery

The Women of NOW

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Barbie: the patriarchy, the existentialism, the capitalism – discuss with spoilers

Greta Gerwig’s smash hit ode to women delves deeper than many would have expected from a film based on a problematic doll

- This article contains spoilers for Barbie

W hen the news first broke that Greta Gerwig would tackle a Barbie movie, excitement started to build long before anyone actually knew what that meant. Unlike superheroes or princesses or so much other exhumed IP, the glamorous doll doesn’t come prepackaged with narrative, leaving open the question of what she would do in a big-screen vehicle primarily greenlit off her brand recognition.

Gerwig’s thoughtful track record as a film-maker suggested that she wouldn’t take the gig unless she had something up her ruffled taffeta sleeve, leading many to theorize a meta element possibly sending Barbie into the real world, but nobody could have guessed the extent to which the director-co-writer has taken the concept and run with it. Even the trailers affirming that Barbie makes the interdimensional montage from her reality to ours with Ken in tow still conceal so much of the substance and atmosphere of a film with much more on its mind than the typical Hollywood product.

Now that Gerwig’s latest is out there painting multiplexes an eye-searing shade of pink, we can issue the strongest spoiler alert warning possible and pop Barbie’s head off to see what’s going on inside her cavernous neck hole. Read on for a discussion of the internal logic, the peppy pop politics, the cameos and everything else bundled with this shiny new cinematic playset:

It’s a Barbie world, with physics to match

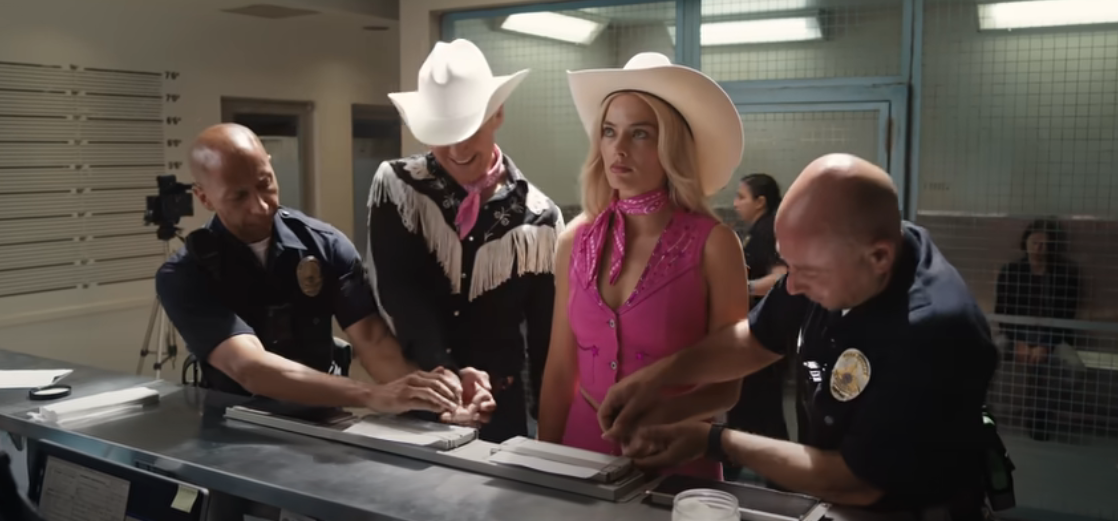

Following a Kubrick-aping prologue that introduces Barbie in the place of 2001: A Space Odyssey’s monumental black obelisk, the film descends on Barbie Land, a soundstage fantasy of Dream Houses painted in hyper-saturated color. This realm is governed not by the laws of nature, but by the childlike illogic of playtime: Margot Robbie’s Stereotypical Barbie drinks from an empty cup, bounces off of plastic water and floats from her top-floor bedroom down to her car on the street as if carried by an invisible hand. The chipper, blunt dialogue sounds like the internal monologue of an eight-year-old’s imagination, declaring every day forever and ever to be the best day ever. When Ken (Ryan Gosling) hurts himself, Doctor Barbie heals him in the space of a single sentence. If Barbie and Ken were to kiss, one assumes they would do so by mashing their faces together at a diagonal.

Every aspect of the first act’s setting has been informed by the rituals and aesthetics of toys and their attendant media, harkening back to the brand-savvy of The Lego Movie. During an argument, Ken hurls Barbie’s wardrobe out through the missing fourth wall of her home, and each outfit momentarily flattens into a display-fold with logo and caption while suspended in the air. An upbeat song by Lizzo delivers exposition like a commercial jingle, narrating each of Barbie’s actions as she performs them. In this land of rictus smiles and relentless sunshine, imperfection is a cardinal sin; Barbie’s existential crisis kicks into gear as she notices a small patch of cellulite on her thigh, and that her naturally high-heeled feet now stand flat on the ground. Horror of horrors – she’s becoming a real woman.

The big, bad patriarchy

Her search for a cure directs her to the real world, where she’s shocked to find that our Earth bears little resemblance to the estrogen-fueled paradise she left behind. As in their feminist Eden, Barbie and Ken came expecting a female president, female garbage-haulers, female Nobel laureates and a coterie of adoring, pliable men just grateful to share their presence. She’s shattered to find that she isn’t the inspirational role model she imagined herself to be, but he’s delighted to discover a power structure that places him and his brethren on top, and carries this thrilling new ideology back to Barbie Land. Before you can say “Simone de Beauvoir”, he’s instituted a full-blown patriarchy with all the once-empowered Barbies brainwashed into submissive, beer-serving pleasure slaves. With a little help from walking #NotAllMen counterpoint Allan (Michael Cera), Barbie must open her sisters’ eyes to the reality that there’s more middle ground to womanhood than being an accessory to a man or a flawless exemplar of femininity.

The reactionary weirdoes decrying Barbie as peddling the “woke” agenda haven’t pulled much of a gotcha, accurately summarizing the textual substance of a film about one woman’s sudden burst of institutional consciousness. Like a college freshman taking an intro class on gender – or perhaps like a high-schooler seeing a mass-market blockbuster with a developed political streak for the first time – Barbie becomes abruptly aware of the untenable societal pressures heaped upon womankind, released in a cathartic monologue by normal-person surrogate America Ferrera. She resolves the many contradictions of the male gaze by slicing through the Gordian knot, simply concluding that whatever women want is fine, so long as everyone lets them live their lives in peace. It’s a pretty anodyne statement, though it accompanies an ending that effectively reduces men to pets. The steadfast refusal to coddle male ego may be the most unabashedly subversive notion in a project often conflicted about its opposing mandates as a critical work of art and a commercial good for sale.

Stickin’ it (kind of) to the suits

Gerwig gets out in front of her decision to take a check from Mattel by centering her new corporate overlords in the film. Barbie and Ken’s shenanigans in the real world draw the attention of the Mattel C-suite, portrayed as a conference table’s worth of largely interchangeable men led by a CEO who requests to be called “Mother” (Will Ferrell) and his CFO flunky (Jamie Demetriou). Being authority figures, they naturally assume the antagonist role as they race to get their star product back in her box, a literal display case binding her wrists and ankles positioned as metaphor for an attitude of silent compliance. Gerwig’s revisionist outlook seeks to liberate the plastic and fantastic icon, allowing her a less orderly humanity in more than just a biological sense. Warhol’s axiom about art being whatever you can get away with comes to mind in surprisingly off-brand moments such as the instant-classic punch line that ties a ribbon on the film.

And yet for all the valid critique lodged by Gerwig – that this company marketing itself to little girls has entirely male management, that they profited for many years off of unattainable body standards, that they have hastily discontinued dolls like the pregnant Midge and the ambiguous Earring Magic Ken and anything else complicating their clean, hegemonic worldview – the film can’t help its promotional origins in brand synergy. Ferrera’s character pitches the CEO on a normal-person Barbie, a character unencumbered by the expectations to be an immaculately manicured beauty nor a successful career woman. Ferrell laughs this off as a non-starter until his CFO looks up from a calculator and suggests it would actually make them money, at which point the doll is put into immediate production. Gerwig’s having a laugh at her own expense, conceding that all her subversions will be happily permitted so long as they agree with the profit margins.

Everyone’s invited to the party

The first trailer revealed that Robbie-Barbie lives as one of many such Barbies populating Barbie Land, their rank a rainbow of demographic representation including Issa Rae, Hari Nef, Sharon Rooney and Ana Cruz Kayne. (Featured soundtrack artist Dua Lipa even pops by as a trio of mermaid sisters to wobble her way through a few lines of dialogue, most of which are “Hi, Barbie!” John Cena dons a wig of flowing blonde tresses as her Kenmaid counterpart.) Likewise, Gosling’s Ken rolls with an entourage of backup Kens, though in keeping with the film’s ladies-first doctrine, the second-stringer likes of Kingsley Ben-Adir and Ncuti Gatwa get slightly less to do than the ensemble Barbies. Odd man-boy out among the fellas is Cera’s Allan, the less-macho Ken alternative initially marketed as a “friend” and shown here to enjoy giving the guys foot massages. Perhaps he’d get along with the briefly glimpsed Sugar Daddy Ken, played by a sporting Rob Brydon.

Other casting choices hint at Gerwig’s personal tastes seeping into the fabric of her film-making; the narration courtesy of Helen Mirren suggests a connected cinematic universe linking Barbie and the cult comedy series Documentary Now!. Barbie creator and Mattel co-founder Ruth Handler appears with a deified glow about her in the form of Rhea Perlman, the actor’s presence a possible nod to her past gig on Cheers as sharp-tongued barmaid Carla Tortelli, the kind of flinty, funny, unapologetic woman that speaks to Gerwig. In one of the film’s most unexpectedly poignant moments, Barbie shares a brief chat with an anonymous woman on a sidewalk bench, informing her that she’s beautiful only for her to respond: “I know.” That woman is Ann Roth, legendary costume designer and frequent collaborator of Gerwig’s husband and co-writer Noah Baumbach, her celebrated body of work across more than 50 years in the industry undoubtedly a point of admiration for the director. She’s living proof that no dividing line separates fashion from high art, one of the guiding principles for the film’s sartorial euphoria.

The library of influences

It’s not hard to imagine the dead-souled version of Barbie that alienates its built-in fanbase with lowest-common-denominator laziness and creative indifference, more advertisement than entertainment. Gerwig has endeared herself to moviegoers in part for the care she’s put into the making of her grand entrée to the budgetary big leagues, much of it informed by her encyclopedia passion for cinema at large. She’s spoken in interviews about the many Technicolor marvels of the past that contributed to the vivid palette of Barbie’s blissfully non-real homeworld, everything from Golden Age musicals like The Wizard of Oz and Singin’ in the Rain to transatlantic imports like The Red Shoes and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. Her penchant for macro-scaled sight gags can be traced back to the oeuvres of Jacques Tati and Charlie Chaplin before him, masters of physical comedy relevant to actors mimicking the body language of posable playthings.

Other reference points work on the conceptual level; Barbie’s revelatory sight through her artificial status quo nods to The Matrix, The Truman Show, and the rest of the entries from the Onscreen Existentialism for Dummies canon. Every piece of the film speaks to some facet of Gerwig’s cinephilia, a magpie collage of favorites befitting the doodling and locker-adorning of adolescent girls. A disco number nicks fashions from Saturday Night Fever, while the kooky absurdist humor has roots in Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure. Eclectic as these picks may be, they’re all organized under a single, fully formed sensibility. Mattel may have stamped their logo all over the film, but audiences have taken note and flocked in droves because in the auteurist sense, Gerwig has made it her own as well.

- Now you've seen it

- Margot Robbie

- Greta Gerwig

- Ryan Gosling

- Comedy films

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

‘Barbie’ is, at its core, a movie about the messy contradictions of motherhood

Assistant Professor of Film and Media Studies, Arizona State University

Disclosure statement

Aviva Dove-Viebahn does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Arizona State University provides funding as a member of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Editor’s note: This article contains plot spoilers for “Barbie.”

The wildly popular “ Barbie ” movie has been touted for its celebration – and critique – of femininity.

As a mother and a media scholar , I couldn’t help but see “Barbie” through an even narrower lens: as a film that, at its core, is about mothers and daughters.

The film’s plot centers on a life-size doll, known as “Stereotypical Barbie,” played by Margot Robbie , who begins to malfunction: Her feet go flat, and she can’t stop thinking about death. So she leaves her perfect plastic life to embark on a quest to restore the boundary between the real world and Barbieland. Along the way, she learns that the real world is nothing like her girl-power wonderland, where Barbies hold all the positions of power and influence and Kens are just accessories.

But its thematic heart rests in the film’s examination of the tensions around being a mother – a role often taken for granted, even as the cultural fantasies of motherhood clash with the actual sacrifices that moms make.

Motherhood as mere drudgery?

I was immediately struck by the movie’s funny but chilling observations about motherhood.

“Since the beginning of time,” unseen narrator Helen Mirren intones sardonically in the film’s first line, “since the first little girl ever existed, there have been dolls.” (Cinephiles will immediately recognize this scene and its setting as an homage to Stanley Kubrick’s famous “ dawn of man ” opening from “ 2001: A Space Odyssey .”)

Girls appear on screen, wearing drab, antiquated dresses and playing “house” with their dolls in a primitive setting, expressionless and practically drooping with boredom. The problem with these dolls is that girls “could only ever play at being mothers, which can be fun” – Mirren pauses meaningfully – “for a while.”

Then, she adds, her tone turning cynical, “Ask your mother.”

The appeal of motherhood, Mirren seems to suggest, eventually morphs into unwanted drudgery – a reality underscored moments later when the girls meet their first Barbie, who towers above them, larger than life, inspiring them to smash their mundane baby dolls.

Barbie – a doll of a young, beautiful woman – compels kids to leave the ennui of motherhood behind for the pink plastic sparkle of Barbieland, where all the Barbies live their best lives forever, embodying feminine perfection and possibility.

The framing of motherhood as thankless and undesirable echoes mid-20th-century feminist critiques of child rearing and housework. These roles not only bound women to the home but also forced them to perform repetitive tasks that didn’t reflect their abilities and derailed their ambitions.

In her 1949 book “ The Second Sex ,” French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir argued that women, to empower themselves, needed to reject the myth that motherhood represented the pinnacle of feminine achievement. American writer Betty Friedan would echo this sentiment in her 1963 book “ The Feminine Mystique ,” railing against the image of the “happy housewife heroine” who finds fulfillment in being a wife and mother.

It’s no coincidence that these ideas overlapped with the invention of Barbie in 1959. While predating the women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s, Barbie’s creator, Ruth Handler, did design the toy to allow girls to imagine their future adult selves , rather than simply play-acting as mothers using baby dolls.

The value in ‘motherwork’

And yet, not only do many women enjoy being mothers, but motherhood also plays an essential role in society and life.

In her 1976 book “ Of Woman Born ,” feminist poet Adrienne Rich draws a distinction between the fulfilling relationship mothers can have with their children and the patriarchal institution of motherhood, which keeps women under men’s control.

Sociologist Patricia Hill Collins coined the term “motherwork ” in the mid-1990s to highlight the experiences of women of color and working-class mothers, many of whom don’t have the resources to pursue their own ambitions over caring for their families and communities. When you’re just trying to navigate the day-to-day without wealth or other forms of privilege, options like hiring a nanny or paying for graduate school aren’t feasible or a priority.

For these mothers, the survival of their children is not a given. Instead of tedium and oppression, motherwork acknowledges that mothering can be a radically important labor of love and a source of empowerment in its own right.

In “Barbie,” the mother-daughter relationship between Gloria, played by America Ferrera , and her daughter Sasha, played by Ariana Greenblatt , contains these contradictions.

After experiencing a vision of the person whose sadness seems to be the source of her malfunctions, Stereotypical Barbie initially assumes it’s Sasha’s tween angst that’s disturbed the perfection of Barbieland and drawn her into the real world. Instead, Barbie discovers it’s Gloria’s loneliness – and her nostalgia for a simpler time when she played Barbies with her daughter – that has caused the rift between reality and fantasy.

Sasha and Gloria’s adventure with Barbie – first escaping the Mattel executives who want to lock Barbie in a box and then journeying back to Barbieland to rescue the other Barbies from the Kens, who are trying to take over – repairs the relationship between mother and daughter.

Gloria remembers what it’s like to find joy in motherhood, and Sasha realizes that her mother isn’t just a bland set of values against which to rebel. Gloria is a fully fledged person with a rich inner life who, by her own estimation, is sometimes “weird and dark and crazy,” which Sasha admires.

Sasha – and all the Barbies – have something else to learn from Gloria, too.

Stunned that even someone as perfect as Barbie feels like she’s not good enough, Gloria delivers a poignant monologue encapsulating, in Barbie’s words, “the cognitive dissonance required to be a woman under patriarchy.”

Gloria, as a mom struggling to reconcile her deep love for her child with the fear that she’s constantly failing at motherhood, knows all too well how this cognitive dissonance wears women down.

In her 2018 book “ Mothers: An Essay on Love and Cruelty ,” scholar Jacqueline Rose argues that motherhood is tied to notions of citizenship and nation and, for this reason, can become “the ultimate scapegoat for our personal and political failings.”

The ending to “Barbie” rejects the notion that mothers are to blame for their children’s mistakes. Instead, the film offers another perspective through the character of Ruth Handler, Mattel’s founder, who’s played by Rhea Perlman. Handler helps Barbie see what awaits her if she chooses to become human.

Symbolically letting go of her creation and encouraging her to forge her own path, Ruth tells Barbie that she cannot control her any more than she could control her own daughter, and that mothers should pave the way for their children, not hinder them.

“We mothers,” she explains, “stand still so our daughters can look back to see how far they’ve come.”

This sentimental and self-effacing message seems at odds with the film’s nuanced portrayal of motherhood through humor and critique.

But, throughout, “Barbie” invites viewers to question even its own structure, tenets and messaging – and presents multiple perspectives on motherhood.

Mothering is hard work and sometimes may even be thankless labor. It may bore or disappoint. It can be affirming or heartbreaking or both. It involves leading and following, holding on and letting go.

Being a mother shouldn’t have to be about sacrifice or about fitting some impossible ideal. Instead, motherhood can highlight the possibilities of living in – and with – the contradictions.

- Working mothers

- Barbie dolls

- Barbie movie

Visiting Professor - 2024-25 Australia-Korea Chair in Australian Studies at Seoul National University

Senior Research Ethics Officer (Human Ethics Pre-review)

Dean, School of Computer, Data and Mathematical Sciences

School of Social Sciences – Academic appointment opportunities

Union Organiser (part-time 0.8)

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Greta Gerwig’s Barbie is a Fascinating, Spectacular Philosophical Experiment

Barbie literalizes the abstract and abstracts the literal in an engaging, thought-provoking inquiry into the female experience.

Do you remember the scene in Singin’ in the Rain where Gene Kelly and Cyd Charisse dance a romantic, longing modernist-ballet number? That scene is a dream sequence within a dream sequence. Gene Kelly’s character, an actor in late 20s Hollywood, is pitching a movie to a studio head and the film allows the viewer to watch the description he is conjuring. In this imaginary scene, a “young hoofer” comes to Broadway with dreams of being a star, and has them stymied for a while, along the way meeting a beautiful woman—Cyd Charisse—who is dating a gangster. He imagines falling in love with her anyway, and so the film takes us to that fantasy, which takes the form of a windy dance on a blue-and-pink-tinted soundstage.

What we’re watching is so far removed from the plot of the actual Singin’ in the Rain —which is about the Hollywood community adjusting after the advent of sound technology—but it doesn’t matter. It is a beautiful scene, a stunning bodily representation of desire and passion in the brief moment they are allowed to manifest. Movies don’t exist just to relay plots; they have tools and qualities all their own that permit experimentation, and even allow the visual exploration of abstract things like feelings, thoughts, and ideas.

It is known, via a Letterboxed profile curated by the writer-director-Greta Gerwig, that her new film Barbie takes some inspiration from Singin’ in the Rain , as well as other musicals from Hollywood’s Golden Age, including Kelly’s even more abstract An American in Paris . Gerwig’s Barbie, a dramatically hyped mainstream film about the famous Mattel doll that was created in 1959 and went on to become one of the most influential pop cultural forces in history, shares an essence with these movies.

It is an inventive, highly wildly conceptual thought experiment—not merely about the doll Barbie or even her complicated legacy and what she represents, but also about what it means to be a woman. It takes place in a similar kind of space as “the movie musical” writ large, a genre of alternate reality in which emotions and thoughts can be explored through music, song, dance, and other stuff that doesn’t happen in real life.

Barbie combines the rules of the movie musical’s imaginary netherworld with the investments of a Beckett or a Ionesco play. We’ve all seen plays where human actors play unwieldy concepts like “the city of St. Louis” or “polio” or even real material things like “bullets.” That’s the variety of inquiry Barbie is; yes, it explores the complex figure of the Barbie Doll through cinematic conventions of faux-documentary, movie-musical, and traditional Hero’s Journey narrative, but it also is simply an unreal experiment, a highly symbolic exercise where theoretical entities get to speak for themselves, and where real people get to tell anthropomorphized theoretical entities what effects they have on the human experience. The whole movie is a mise-en-abyme-heavy dream sequence, a fantasy of a dialogue between real women and womankind’s evolving, go-getting golem plaything.

I was fascinated by Barbie , which was written by Gerwig and Noah Baumbach, and which earnestly takes on a lot of hard work and mostly pulls it off. Compellingly, Barbie literalizes the abstract and abstracts the literal as it progresses. Gerwig’s own (presumed) thoughts and research into three-score years of Barbie frame the story, especially via the movie’s opener, a 2001: A Space Odyssey pastiche in which little girls discover the Barbie doll for the first time; the narrator (Helen Mirren) reminds us that, before Barbie, little girls could only play with baby dolls, pretend to be mothers; Barbie was the first grown-up doll. She was the first major girl-marketed cultural signifier insisting that a girl could be someone other than a mother. And not only that, but that she could be someone glamorous and exciting.

After this, the film follows a day in the life of a blonde Barbie, the main Barbie, the “Barbie you think of when someone says ‘think of a Barbie,'” the film calls her. She is played by Margot Robbie, who also produced the film. She lives in Barbie Land, a realm where the souls? subconscious minds? astral projections? of literal Barbie Dolls live and interact together. While their doll-bodies are being played with in the Real World, their selves live here, though they take on the characteristics of the things happening to their doll-bodies in play. This means that Barbie Land is kind of magic; outfits change spontaneously depending on the activity, Barbies float from one level of their Dream Houses to another—as if they are being played with by invisible hands.

Barbie Land is a paradise of female empowerment. The narrator reminds us how Barbie has taken on many more meanings and identities since her debut in a bathing suit in 1959, and that the Barbie concept is diverse in terms of representations of female excellence and perfection. Barbie is all women, the narrator reminds us, and she is a reminder that women can do anything. In Barbie Land, the Barbies—beautiful, accomplished, happy in all their different appearances and jobs and roles—run a supportive, productive world. There are also Kens, who do not have jobs or purposes. Barbie’s Ken (Ryan Gosling) lives for her, longs to unite more with her, wants her to love him. In interviews, Gerwig has noted that Barbie, and not Ken, is the main draw of Mattel products, and analyzed its fascinating implications: “Ken was invented after Barbie, to burnish Barbie’s position in our eyes and in the world. That kind of creation myth is the opposite of the creation myth in Genesis.”

Gerwig notes the potential for Barbie’s incredible progressiveness and takes advantage of it—telling a story about a Barbie who discovers that, in actual life, women are seen as the accessories. For the record, I don’t think the film advocates that people of any gender should be accessories to those of another gender, but Barbie still allows us to revel in the delight of an all-female paradise for a while.

Anyway, one day, our Barbie begins to experience an existential crisis—she begins to wonder about dying and freak about about “forever” and stasis. Her feet loosen from their arched position and land flat on the floor. Panicking, she goes to see an oracle-style Barbie known as Weird Barbie, maimed with crayons and perpetually in a split position after her doll self got “played with too hard.” Weird Barbie (Kate McKinnon) explains that Barbies are psychically connected to the children playing them, and so in order to correct these out-of-place crises, Barbie has to travel to the Real World and find that girl and help her assuage her concerns.

Barbie heads on a journey to the Real World, accompanied by Ken, who longs to prove himself to her. But when they arrive in the modern world (Los Angeles), they discover something jarring: the world is not, in fact, a feminist society in which women get to exercise (and be celebrated for) their skills and aptitudes, but… the opposite. Barbie herself grows very depressed, while Ken feels empowered, by this rift. Ken runs back to Barbie Land to tell the other Kens that “men rule the world” in reality while Barbie discovers that she’s unwittingly something of a villain there. She discovers, from a group of tween girls, that not only is Barbie not a feminist hero, but is also a controversial and outdated toy who has contributed to and participated in the creation of impossible, unhealthy, and problematic standards for women, not to mention the glorification of capitalism and the mass production environmentally-poisonous plastic. And she discovers Mattel, an FBI-style entity determined to keep the existence of the Avalon-like Barbie Land a secret.

While evading the Mattel G-Men, Barbie winds up meeting her playmate, who turns out not to be a child, but the mother of a child. She, Gloria (America Ferrera), has always loved Barbie, but her love for Barbie cannot override the frustrations and problems of her regular life, including a lack of professional and creative fulfillment (she’s a secretary at Mattel). But something happens when they’re together, and Barbie decides to bring her new friend and her Barbie-hating preteen daughter Sasha (Ariana Greenblatt) back to Barbie Land to help empower them. But when they get there, they discover that Ken has brought the idea of male supremacy back, taken over the paradise, and brainwashed all of the brilliant, accomplished Barbies into serving them and ornamenting their spaces.

Barbie isn’t a subtle movie, and that’s okay! Subtlety is overrated. It’s clear now, if it hasn’t been before, that Barbie slings many, many metaphors about the state of female existence in its current moment. Barbie is about a jealous, women-hating current that runs deep in male perspective. Ken is ultimately a bit of an incel (even though he’d be called a Chad BY the incels), and in Barbie we watch as all the progress, works, dreams of women are dismantled and erased and destroyed by men who need to feel like they control powerful women in order to feel powerful, themselves. It’s a movie that feels like it’s about Abortion Bans and the January 6th insurrection and our Post-Trump society just as it feels (sadly) timeless.

But even more insightful is what happens to Barbie when she realizes her world is a disaster. She grows depressed, begins to hate and doubt herself. She feels unattractive, unimportant, like a failure. Gerwig was influenced in writing the screenplay by the 1994 nonfiction book Reviving Ophelia, about the sudden, mass self-confidence and depression crisis that hits girls around puberty. “They’re funny and brash and confident, and then they just—stop,” she explained of the phenomenon to Vogue . “…All of a sudden, [girls think], Oh, I’m not good enough .”

Watching Barbie , this moment (when Robbie’s Barbie collapses into despair, feeling like a failure because she can’t fix the horrible things happening around her), was one of the most intuitive moments I’ve ever seen on film. Even more so is when Gloria comforts her, by acknowledging the horrible double-standards that make women feel this way, universally, delivering a heart-rending, passionate soliloquy that provides the film’s heart as well as its thesis statement. I cried a lot during the Barbie movie, but I really cried here.

Barbie not only understands what it’s like to be a woman, but has a lot of love for women, which is refreshing. It also has a lot of love for childhood, but it doesn’t allow the nostalgia for girlhood to muddle the empowerment of adult women. Barbie is a genuine masterpiece for its studies in making the intangible tangible , and this is epitomized by its magnificent production, set, and costume design.

The Barbie Dream Houses don’t have walls, just like in life. The Barbie World doesn’t come with food, just adhesive decals and plastic pieces. There is an extroardinary tactility, solidity to this world that is so reminiscent of playing with Barbies, like how McKinnon’s defaced Barbie almost always has her legs split apart. Watching the film, I remembered the feel and movement of these toys. There’s a Proust joke in Barbie , but I’m not joking when I’m saying that if Proust saw Barbie, he’d write another 1,000 pages. That’s how evocative Gerwig’s direction is. There are whole scenes in the movie that seem intended just to allow the audience to feel .

Robbie, who demonstrates tremendous physical comedy skills while also relaying depths of humanity, is wonderful as this torn Barbie. Gosling, whose relentless commitment to his character is astonishing, would be the film’s scene-stealer if Robbie wasn’t such a strong anchor. But Ferrera is the best part of the star-studded cast, a phenomenally real woman.

Barbie is so insightful in its symbolic intervention that when it returns to its Hero’s Journey/Barbie-vs. Mattel plot, it becomes a lot less satisfying. Mostly because, after watching ideas come to life, becoming reminded about the tethers to branding and commercial interests feels irrelevant and almost contradictory and even occasionally unpleasant. There’s a little too much humanization in the end, actually, partially of entities who might not deserve it, in a story that is, ultimately, about women . Things get messy and very, well, imperfect.

Still, I spent the nearly two-hours of Barbie noting how thoughtful and ambitious it was. Personally, I felt very seen and understood. I was moved and even felt a little appreciated, in a universal way. And that’s not an easy to do with a main character who is essentially a lump of plastic shaped like a person. But there is nothing fake, nothing false about Barbie . To Barbie , life may be plastic, but it’s also profound.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Olivia Rutigliano

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Lit Hub Daily: July 21, 2023

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Home — Essay Samples — Entertainment — Barbie — Exploring Identity and Cultural Reflections in the Barbie Movie 2023

Exploring Identity and Cultural Reflections in The Barbie Movie 2023

- Categories: Barbie Film Analysis

About this sample

Words: 724 |

Published: Oct 25, 2023

Words: 724 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, gender, identity, and cultural shifts: a screenplay’s influence, challenges and triumphs: bringing barbie to life, beyond the screen: societal impact and cultural significance.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Entertainment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1710 words

4 pages / 1738 words

2 pages / 913 words

3.5 pages / 1665 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Barbie

Within the realm of cinematic artistry, the Barbie Movie stands as a noteworthy exemplar, effectively intertwining visual and auditory aesthetics to craft a narrative that transcends the boundaries of conventional cinema. This [...]

Barbie movies, often associated with entertainment and fantasy, may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about educational tools for children. However, these animated films have a surprising potential to [...]

Following the publication of his most notable work, A Clockwork Orange, Anthony Burgess commented on the function of literature in a mutable society. There is not much point in writing a novel unless you can show the possibility [...]

"Insufficient facts always invite danger" declared Spock to Captain Kirk as the U.S.S. Enterprise was on deep alert after discovering a sleeper cell in space with seventy-two unconscious super-humans inside (Coon, 1967). His [...]

Black and white, morning and night: the world fills itself with conflicting forces that must coexist in order for it to run smoothly. Forces like diversity and the fear of terrorism or competition and the desire to peacefully [...]

Stanley Kubrick wrote the screenplay for and directed the film A Clockwork Orange based on the book by Anthony Burgess with the same title. The distinguishing feature of the book is the language the narrator, Alexander DeLarge, [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

'Barbie' film's view on patriarchy resonated, from cast to teens

Teens get it.

Jumpstart your morning with the latest legal news delivered straight to your inbox from The Daily Docket newsletter. Sign up here.

Reporting by Lisa Richwine and Rollo Ross; Editing by Mary Milliken and Jonathan Oatis

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. , opens new tab

Cillian Murphy wins best actor Oscar for 'Oppenheimer'

LOS ANGELES, March 10 (Reuters) - Cillian Murphy earned his first Academy Award for his portrayal in “Oppenheimer” of the physicist who led the United States’ development of the atomic bomb during World War Two.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Why Barbie Must Be Punished

By Leslie Jamison

My childhood Barbies were always in trouble. I was constantly giving them diagnoses of rare diseases, performing risky surgeries to cure them, or else kidnapping them—jamming them into the deepest reaches of my closet, without plastic food or plastic water, so they could be saved again, returned to their plastic doll-cakes and their slightly-too-small wooden home. (My mother had drawn her lines in the sand; we had no Dreamhouse.) My abusive behavior was nothing special. Most girls I know liked to mess their Barbies up; and when it comes to child’s play, crisis is hardly unusual. It’s a way to make sense of the thrills and terrors of autonomy, the problem of other people’s desires, the brute force of parental disapproval. But there was something about Barbie that especially demanded crisis: her perfection. That’s why Barbie needed to have a special kind of surgery; why she was dying; why she was in danger. She was too flawless, something had to be wrong . I treated Barbie the way a mother with Munchausen syndrome by proxy might treat her child: I wanted to heal her, but I also needed her sick. I wanted to become Barbie, and I wanted to destroy her. I wanted her perfection, but I also wanted to punish her for being more perfect than I’d ever be.

It’s not that I literally wanted to become her, of course—to wake up with a pair of hard plastic tits, coarse blond hair, waxy holes in my feet betraying the robotic fingerprint of my factory birthplace—but some part of me was already chasing the false gods she spoke for: beauty as a kind of spiritual guarantor, writing blank checks for my destiny; the self-effacing ease afforded by wealth and whiteness; selfhood as triumphant brand consistency, the erasure of opacity and self-destructive tendency. I craved all of these—still do, sometimes—even as my own awareness of their impossibility makes me want to destroy their false prophet: Barbie as snake-oil saleswoman hawking the existential and plasticine wares of her impossible femininity, one Pepto-Bismol-pink pet shop at a time.

Even after I grew out of playing with Barbies, I found a surrogate to embody the same fraught double helix of adoration and resentment: the popular girl. As a figure, the popular girl was at once supernatural—larger than life—and many-headed all around me. At my prep school in Los Angeles, popular girls were everywhere , spritzing themselves with the Gap perfume called Heaven and presumably all gathering at the same Beverly Hills mansion to snort coke, get waxed, and act aloof around the same boys who only ever spoke to me if they were asking to borrow my TI-82 graphing calculator. It only got worse when I became friendly with two of these popular girls—we ran cross-country together—and found them wickedly funny, and (worse) genuinely nice . It all seemed like a cosmic clerical error, a lopsided allocation of assets. The story that was helping me survive my own adolescence—that the popular girls were hopelessly vapid and morally bankrupt—had collapsed; now I had a more robust vision of their superiority, validated and verified, to wear like a hair shirt. Turns out that Barbie was just the first name I gave to the lifelong project of punishing myself with the imagined perfection of others.

If Barbie embodied something that always felt beyond my reach, then playing with Barbie—subjecting her to an array of trials and tribulations—was less about becoming her than it was about exerting some sort of power over the archetypes that tyrannized me. I didn’t have to become her; I could be her god—a loving god, or a vengeful one. Walter Benjamin once observed that “ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to objects,” but—as everyone knows—intimacy is never a pure feeling. It’s never as simple as unmitigated affection or adoration; it’s always striated with resistance and resentment. Perhaps this is what Barbie offers, the chance to feel both things at once: wanting something and wanting to destroy it. Wanting to become something and hating yourself for wanting to become it.

Greta Gerwig’s summer blockbuster, “ Barbie ”—fuelled by a marketing campaign so large you can practically see it from outer space—knows that much of Barbie’s appeal stems from the fact that people love to hate her. The film’s slogan promises “If you love Barbie, this film is for you; If you hate Barbie, this film is for you,” a pledge that seems to knowingly get it while actually missing the point entirely. It frames love and hate as mutually exclusive states, when Barbie’s power rises from her ability to make you love her and hate her at once.

In the early stages of developing Barbie, in the late nineteen-fifties, Mattel commissioned a report from a marketing expert named Ernest Dichter, who recommended leaning into rather than away from Barbie’s potential as an antagonist: perhaps instead of “a nice kid, friendly and loved by everyone,” she could be “vain and selfish, maybe even cheap?” Dichter’s report understood that hating Barbie is not so much an act of rebellion as it is part of the plan.

Gerwig’s “Barbie” certainly knows that little girls—or, at least, a certain kind of little girl—likes to ruin her Barbies: deface them, torture them, dismember them. One of the film’s pivotal characters is Weird Barbie, played by Kate McKinnon, a Barbieland misfit who has turned strange because “someone played with her too hard in the real world.” We see a flashback montage of the cruel experiments that have left her with clownish makeup, streaked and singed hair, and legs stuck in “permanent splits.”

But Weird Barbie, like the Weird Sisters in “Macbeth,” becomes a kind of dark guide, serving up unwanted truths. She helps the film’s heroine—Margot Robbie’s Stereotypical Barbie—make sense of what is happening to her, as her “perfect” life and “perfect” body succumb to a series of glitches: her morning waffle is burnt. Her milk has curdled. Her plastic feet—permanently molded to high heels, even when she isn’t wearing them—have flattened, so that her heels (to her horror) now touch the ground. As in Chantal Akerman’s classic film “ Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles ,” trouble first shows up as a series of minor domestic disruptions. (In Akerman’s film, a pot of overcooked potatoes is the first sign that something is afoot.) In a female life circumscribed by domesticity or fantasy, these banal disruptions are the seismograph upon which deeper tremors first make themselves felt.

For Barbie, these tremors eventually force her to reckon with the claustrophobic chokehold of her own seamless existence. Her body begins to age, her thighs rippling with cellulite, and she finds herself ambushed by anxieties about her own mortality. In the middle of her own disco party, Barbie asks her gold-lamé-clad friends, “Do you guys ever think about dying?” and the music suddenly stops. No one responds. Barbie corrects herself, “I mean, I’m just dying to dance,” and the music kicks up again.

When Barbie seeks counsel from Weird Barbie, she is told that she will have to cross from Barbieland to the real world to seek out the little girl playing with her. (“You are becoming inextricably intertwined,” Weird Barbie says. As Benjamin could have told her, they always were.) The film’s promotional materials describe the quest that ensues—Barbie rides her neon Rollerblades right into the real world, where she immediately gets catcalled by a cluster of construction workers—as a “full-on existential crisis.” But, at the end of the day, it’s a Mattel-authorized crisis. Does it ultimately disrupt Barbie’s brand or simply consolidate it? (As Slavoj Žižek argues, fair-trade coffee is also a clever bit of inoculation designed to make us feel better about capitalism.)

Indeed, it turns out that even Barbie’s existential crisis is—quite literally—a call coming from inside the corporate house; specifically, from a high-level executive assistant named Gloria (America Ferrera) who works on the top floor of the Mattel headquarters. Gloria is a lifelong Barbie devotee, but mother to a teen, Sasha (Ariana Greenblatt), who has emphatically outgrown hers. Gloria has been secretly drawing rogue Barbie models at her desk: Crippling Shame Barbie, Cellulite Barbie, and Irrepressible Thoughts of Death Barbie.

These rebel designs are part of a “dark Barbie” lineage: In “Barbie’s Real Life,” a series of photographs from the eighties, Susan Evans Grove gives us Office Politics Barbie, standing by a desk full of papers, getting groped from behind; Battered Barbie, her under eye smeared with black makeup; and Go Ask Barbie, who leans over a toilet bowl of floating pills. In Todd Haynes’s cult classic “ Superstar ,” his 1987 bio-pic about the life and death of the singer Karen Carpenter, a Barbie plays the film’s titular anorexic. Part of the irony of casting Barbie as Karen is that Barbie-Karen already has a body whose proportions would require illness to sustain. In 1994, a group of Finnish researchers infamously published a study arguing that a real-life woman with Barbie’s proportions would not menstruate.

But under Haynes’s direction, Barbie gets even thinner: to dramatize Carpenter’s illness, Haynes physically chipped away at his doll to make her appear more emaciated, until she is all sharply angled plastic cheeks and skeletal arms. We see a closeup of her doll eyes, blackly terrified at the prospect of a large restaurant meal. We see closeups of her Ex-Lax boxes, her tiny salads, the miniature bottles of ipecac syrup that eventually damage the muscles of her heart beyond repair. The recurring shots of her bathroom scale echo Slumber Party Barbie (1965), who came with a scale permanently set at a hundred and ten.

At one point, we watch Karen’s brother Richard berating her with his scolding concern: “All you ever eat is salad and iced tea!” His worries are less altruistic than instrumental: “Your fans are worried. I can hear them gasping when we walk onstage!” When Richard finds Karen passed out at her dressing-room table, next to an empty box of Ex-Lax, he rages: “What did you do to your makeup? You’re a mess!” The one thing Barbie is never allowed to be: a mess. Which is precisely why we always want to mess her up.

The first time my daughter asked for a Barbie, soon after her fifth birthday, I felt the sense of dread that comes from watching the protagonist of a horror film jimmy open a locked door at the end of a dark hallway. Don’t go in there! Among other things, I worried that her desire for a Barbie would signal the end of an era: her two-year fascination with the goddesses of Greek mythology. My pride in her love for these myths was aspirational, no doubt insufferable. I loved her savvy questions: “Why is Zeus everyone’s daddy?” “Was Medusa a regular woman before she was a monster?” I loved the ways these myths helped her metabolize the inevitable cruelties and betrayals of the world; the ways they helped her reckon with her own contradictory desires for dependence and distance; and, perhaps most of all, the ways they gave her so many fierce and complicated female figures to arrange her mind around. Wise and ferocious Athena with her owl and her unnerving, bad-ass birth, straight from the forehead of Everyone’s Daddy! Or operatic Demeter, plunging the whole world into winter with her sorrow. Or even Persephone, who wanted to rejoin her mother while also carving out a separate identity as queen of the dead. I loved that these goddesses all had their own flaws and self-thwarting desires: Athena and her pride; Hera and her jealousy; Aphrodite and her vanity. These goddesses were psychic chiaroscuros: powerful and wounded, their blood running hot with ambition, animated by dark attachments and shameless hungers.

The first time my daughter asked for a Barbie—to be precise, a Butterfly Princess Barbie—it was hard to imagine this princess, frothy with butterfly-studded pink tulle, bursting out of her father’s skull or putting snakes into an infant’s crib (as Hera had done to baby Hercules, one of her husband’s many children by other women). It was as if, from the glorious ranks of the Greek goddesses, with their superhuman flaws and flashing eyes, only one had survived: Aphrodite. As if her beautiful form had endured as the only possible template for what a woman might fantasize about becoming. (Mattel in fact released a trio of Goddess Barbies in the late aughts: Medusa, Athena, and Aphrodite, framed against a pastel seashell. But the dolls were designed for collecting, not play, and they barely move; Aphrodite’s limbs are capable of almost no articulation at all.)