- Open access

- Published: 06 April 2023

Mental health challenges, treatment experiences, and care needs of post-secondary students: a cross-sectional mixed-methods study

- Elnaz Moghimi 1 , 2 ,

- Callum Stephenson 1 ,

- Gilmar Gutierrez 1 ,

- Jasleen Jagayat 3 ,

- Gina Layzell 3 ,

- Charmy Patel 1 ,

- Amber McCart 4 ,

- Cynthia Gibney 4 ,

- Caryn Langstaff 5 ,

- Oyedeji Ayonrinde 1 ,

- Sarosh Khalid-Khan 1 ,

- Roumen Milev 1 , 3 ,

- Erna Snelgrove-Clarke 6 ,

- Claudio Soares 1 ,

- Mohsen Omrani 1 , 7 &

- Nazanin Alavi 1 , 3 , 7

BMC Public Health volume 23 , Article number: 655 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

7 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

Post-secondary students frequently experience high rates of mental health challenges. However, they present meagre rates of treatment-seeking behaviours. This elevated prevalence of mental health problems, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic, can lead to distress, poor academic performance, and lower job prospects following the completion of education. To address the needs of this population, it is important to understand students' perceptions of mental health and the barriers preventing or limiting their access to care.

A broad-scoping online survey was publicly distributed to post-secondary students, collecting demographic, sociocultural, economic, and educational information while assessing various components of mental health.

In total, 448 students across post-secondary institutions in Ontario, Canada, responded to the survey. Over a third ( n = 170; 38.6%) of respondents reported a formal mental health diagnosis. Depression and generalized anxiety disorder were the most commonly reported diagnoses. Most respondents felt that post-secondary students did not have good mental health ( n = 253; 60.5%) and had inadequate coping strategies ( n = 261; 62.4%). The most frequently reported barriers to care were financial ( n = 214; 50.5%), long wait times ( n = 202; 47.6%), insufficient resources ( n = 165; 38.9%), time constraints ( n = 148; 34.9%), stigma ( n = 133; 31.4%), cultural barriers ( n = 108; 25.5%), and past negative experiences with mental health care ( n = 86; 20.3%). The majority of students felt their post-secondary institution needed to increase awareness ( n = 231; 56.5%) and mental health resources ( n = 306; 73.2%). Most viewed in-person therapy and online care with a therapist as more helpful than self-guided online care. However, there was uncertainty about the helpfulness and accessibility of different forms of treatment, including online interventions. The qualitative findings highlighted the need for personal strategies, mental health education and awareness, and institutional support and services.

Conclusions

Various barriers to care, perceived lack of resources, and low knowledge of available interventions may contribute to compromised mental health in post-secondary students. The survey findings indicate that upstream approaches such as integrating mental health education for students may address the varying needs of this critical population. Therapist-involved online mental health interventions may be a promising solution to address accessibility issues.

Peer Review reports

Post-secondary students frequently report high levels of stress, anxiety, depression, and other mental health concerns [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. In a national survey of Canadian post-secondary students using campus mental health services, 95% reported being overwhelmed and exhausted, 83.7% reported anxiety, 86% were depressed, and 81% experienced loneliness [ 4 ]. Further, 45.1% of post-secondary students experience higher than average stress levels, and up to 35% meet diagnostic criteria for at least one mental health disorder [ 5 , 6 ]. Compromised mental health may increase student distress, academic probations, dropouts, and challenges in finding future employment [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ].

The importance of effective mental health services for all citizens, including youth and young adults is broadly recognized in Canadian society [ 10 ]. As a result, most postsecondary institutions offer several different mental health services to vulnerable groups. These may include social or peer support, promotion and outreach programs, health education, counselling services, accommodations, triage system for urgent care, and short-term therapy [ 11 , 12 ]. Campuses typically do not offer long-term therapy or off-site services [ 11 ]. Despite the services available, treatment-seeking is reported to be as low as 10% [ 5 , 13 , 14 ]. Factors such as cost, stigma, privacy concerns, heavy academic course loads, inability to distinguish between mental illness and stress or other common emotions, work priorities, and long wait times can deter students from seeking help [ 14 , 15 ]. Moreover, adequate and timely access to mental health services by students is adversely affected by a network of personal, social, cultural, and institutional barriers that vary between regions and individuals [ 15 ]. These barriers include limited resources, increased complexity in student psychopathology, fragmented services, and low funding, to name a few [ 11 , 16 ]. Indeed, many student counselling centres report increased service wait times and reduced therapy sessions [ 11 ]. These strains are worsened in smaller institutions with fewer staff and resources [ 17 ]. Treatment barriers and service use amid the COVID-19 pandemic have yet to be fully delineated.

Mental health concerns were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, affecting all profiles of post-secondary students [ 18 ]. In a recent qualitative study, students without pre-existing mental health conditions reported greater social and academic isolation than those with pre-existing mental health concerns [ 19 ]. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis noted an increase in the prevalence of anxiety (36%) and depression (39%) during the pandemic [ 20 ]. In response, many institutions have shifted to telemental health services that encourage continued care [ 21 ]. Other universities have started to implement virtual interventions to help first-year, graduate, and professional students navigate through the changed academic and social environments [ 22 , 23 ]. When assessing support offered by institutions during prolonged campus lockdowns, 91% of Canadian post-secondary institutions offered virtual counselling services, and 84% provided general psychoeducational resources [ 24 ]. Similar services are also available in US-based institutions [ 25 ]. Nevertheless, poor wellness behaviours, mood, and attention in post-secondary students have been observed during the pandemic [ 26 ]. To better understand the efficacy and effectiveness of the available resources during this period, it is critical to investigate how students perceive their mental health challenges and use the services at hand.

The current study aimed to capture post-secondary student mental health and care needs during the post-lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, the study surveyed post-secondary students on their mental health knowledge, treatment-seeking behaviours, perception of mental health services, and perceived barriers that may have limited their access to care. Since the persistence of lockdowns and social distancing laws resulted in online therapy use becoming commonplace, this delivery format was also focused on. The findings of this needs assessment study can inform the development of targeted, effective, and equitable care initiatives for this population.

Study design

The following cross-sectional mixed-methods study collected data through a self-administered online survey. A broad-scoping mental health experience survey was publicly advertised to post-secondary students across Ontario, Canada, through social media. Paid advertisement was not utilized for this study and organic reach was obtained by posting to groups and pages that pertained to the target population. Specifically, the survey advertisement was posted on Ontario-based university and college groups and pages on Reddit and Facebook. The research team as well as Queen’s University health and wellness centres also posted the study advertisement on their Instagram, Reddit, and Facebook social media pages. Data collection occurred from May 5 to June 5, 2022. Participation was voluntary, and the survey was administered via Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Post-secondary students enrolled in any public or private post-secondary institution in Ontario, Canada, were eligible to complete the survey, which entered them in a draw to receive 1 of 20 Amazon gift cards valued at $25. Students of any status, including international, domestic, part-time, full-time, certificate, or degree, were included. To verify student status, participants were asked to provide an institutional email after consenting to participate in the study. The survey link was sent to this email. The consent process informed the students that their responses were in no way linked to their institutional emails. Participants were also asked to include the name of their post-secondary institution in their survey responses. Any student involved in developing or testing the survey was not eligible to complete the survey. Ethics approval was obtained from the Queen’s University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (HSREB) in Kingston, Canada.

Survey development

The research team developed and disseminated the Post-Secondary Student Mental Health Experience Survey to all post-secondary students attending colleges or universities in Ontario, Canada. The decision to limit the survey to Ontario was to pilot the survey and make any necessary modifications before administering the survey to a broader population [ 27 ]. Before dissemination, the survey was reviewed with a sample of post-secondary students enrolled in different programs ( n = 10) and modifications were made based on their feedback. These students were highly involved in student affairs and leadership positions within their post-secondary institutions. The diverse sample also represented an array of equity-deserving communities, including BIPOC, 2SLGBTQ + , international students, and students with different physical and mental health conditions. The survey was then uploaded onto Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and was tested by another sample of students ( n = 20) before finalization. All student reviewers were within the research team’s broad network and agreed to review the survey voluntarily. Once the necessary changes were made, the survey was made available to all post-secondary students attending colleges or universities in Ontario, except for those involved in the survey's development and testing. All participants provided informed consent online before accessing the survey. The final survey focused on specific demographic variables, knowledge of and experience with different mental health treatments and resources (including online delivery formats), perceptions of the accessibility of the current mental health treatments, motivation and likelihood of seeking various types of mental healthcare, and changes students would like to see in the current system of care (Additional file 1 ). The survey intended to capture post-secondary students' mental health needs and identify barriers and limitations to care.

Data analysis

Since participants could skip questions they preferred not to answer, data from participants who did not complete the survey in its entirety were also included in the analysis. Missing data were not imputed because the sample size was sufficient to conduct the descriptive analysis. Each item was assessed individually and reported count percentages were relevant to the total responses of each item. All descriptive analyses were conducted through the online Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) statistical analysis software. Data from the open-ended question at the end of the survey ( Do you have any additional feedback to share ?) were analyzed qualitatively using content analysis methods [ 28 , 29 ]. All relevant feedback was categorized under codes representing prevalent ideas and common categories across the responses. The codes were meant to provide more context on the research findings—in particular, assessing the mental health challenges and care needs of post-secondary students. In the first step, a conventional coding approach was used where coding categories were developed from direct analysis of the entire textual data [ 30 ]. To do this, participant feedbacks were read several times to capture a general sense of the data. Subsequently, primary codes explicitly representing the participant responses were developed and modified. Data coding was done semantically, staying close to the text and using the participants’ words and verbiage. After discussion and refinement by the research team, the final coding strategy was applied to the dataset by two independent coders (EM and CaS), and inter-coder reliability was assessed via Cohen’s Kappa. Before finalization, all discrepancies were resolved through a third coder (GG). A subcategory analysis was then conducted by one of the coders (EM), and any emergent secondary codes were finalized through discussion with the research team. The demographic characteristics of participants who provided qualitative data were compared to that of all survey respondents via chi-squared tests for categorical variables and independent sample t-tests for continuous variables at α = 0.05. All statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA).

Participants

In total, 448 responses were recorded from students across post-secondary institutions in Ontario, Canada. Participants who did not list their post-secondary institution or if the institution was not located in Ontario, Canada, were excluded ( n = 78). On average, participants were 21.9 years of age (SD = 4.1). Most respondents did not have children ( n = 437; 97.5%). Participants reporting their race or ethnicity were given the option to select all applicable identities. For demographic information, please see Table 1 .

Post-secondary student profile

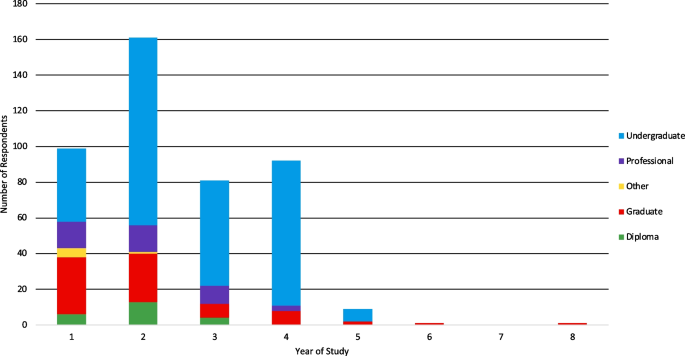

The study respondents were enrolled in 34 different institutions across Ontario. Only one participant attended a private institution (Additional file 1 ). Respondents were mainly enrolled in universities ( n = 406; 90.6%) compared to colleges ( n = 42; 9.4%). The majority of university students attended Queen’s University ( n = 80; 17.9%), followed by the University of Toronto ( n = 43; 9.6%), Ontario Tech University ( n = 38; 8.5%), Carleton University ( n = 37; 8.4%), McMaster University ( n = 37; 8.3%), University of Waterloo ( n = 35; 7.8%), and York University ( n = 21; 4.7%). Most of the respondents attending college were enrolled at St. Lawrence College ( n = 12; 2.7%), Durham College ( n = 6; 1.3%), and Centennial College ( n = 4; 0.9%). Regarding degree type, 65% of respondents ( n = 290) were undergraduate students, and 17.9% ( n = 80) were graduate students. Further, 9.8% ( n = 44) of respondents were pursuing a professional degree, diploma ( n = 24, 5.4%), or other ( n = 9; 2%; Fig. 1 ). Most students were Ontario residents ( n = 351; 90.5%) and did not relocate from another province. Employment status was nearly equal among students, with 48.8% of respondents being employed ( n = 217) and 51.2% ( n = 228) not employed. Students who indicated their weekly employment hours ( n = 73) worked an average of 25.87 h per week (SD = 11.76). Students ( n = 77) also committed an average of 5.4 h (SD = 5.24) to weekly volunteering. See Table 2 for a summary of student profiles.

Year of study and degree type of students

Mental health disorders and symptoms

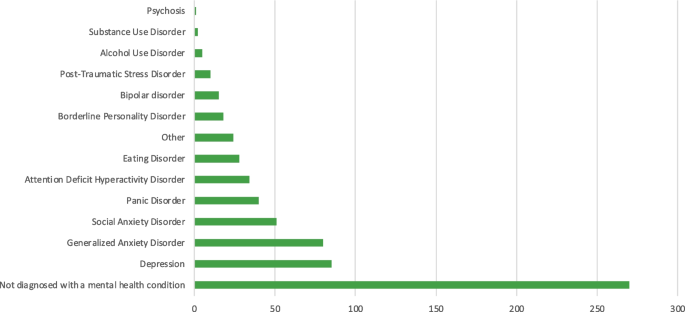

Most participants reported not being diagnosed with a mental health disorder ( n = 270; 61.4%; Fig. 2 ). Amongst those diagnosed, depression ( n = 85; 19.3%) and generalized anxiety disorder ( n = 80; 18.2%) were the most prevalent, followed by social anxiety disorder ( n = 51; 11.6%), panic disorder ( n = 40; 9.1%), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ( n = 34; 7.7%). Participants who were diagnosed with other mental health disorders ( n = 24; 5.5%), most frequently reported obsessive–compulsive disorder ( n = 9; 37.5%). Most participants ( n = 351; 80.7%) reported not having a disability. The most frequently reported disability was neurodevelopmental ( n = 36; 8.6%). When asked if students experienced a decline in their mental health since starting their post-secondary education, 66.5% of respondents ( n = 290) reported a decline in their mental health, 23.4% ( n = 102) did not see a difference in their mental health, and 10.1% ( n = 44) were unsure. Specifically, 66.1% of students ( n = 288) reported problems concentrating, 59.6% ( n = 260) experienced symptoms of depression (i.e., low moods, low energy, and low motivation), 58% ( n = 253) experienced daily general anxiety, 51.4% ( n = 244) experienced anxiety in social situations, 42.2% ( n = 184) had mood swings, 33.7% ( n = 147) experienced panic attacks, and 13.5% ( n = 59) engaged in problematic use of alcohol or other substances including cannabis. Other symptoms expressed by students ( n = 13; 3.0%) predominately comprised insomnia and other sleep disturbances ( n = 5; 3.8%).

Prevalence of mental health disorders among participants

- Mental health needs

Although most students indicated that their mental health knowledge was good ( n = 283; 67.7%), the majority ( n = 261; 62.4%) agreed with the statement that they did not have enough coping strategies and tools related to mental health when starting their post-secondary studies. Many did not believe that post-secondary students have good mental health ( n = 253; 60.5%). Furthermore, not having enough time to focus on mental health during post-secondary studies was also expressed as a concern by participants ( n = 198; 47.3%). Most respondents ( n = 278; 66.5%) believed that the majority of students keep their mental health problems a secret. With respect to high school education, most ( n = 209; 50%) did not believe that the awareness and education on mental health were adequate, and others were neutral about this sentiment ( n = 71; 17%). On the other hand, many participants ( n = 307; 73.5%) believed that improving high school students’ mental health could enhance their overall functioning and well-being during their post-secondary studies.

Treatment-seeking behaviours

Concerning treatment, 70.5% ( n = 182) of respondents indicated that they were not taking medication, and 71.5% ( n = 318) were not receiving counselling or psychotherapy for their mental health. Amongst those receiving counselling or psychotherapy, the majority (52.0%; n = 66) received their sessions over online video platforms and 33.9% ( n = 43) engaged in in-person sessions. Many participants believed that digital mental health care delivery was good but not as good as in-person delivery ( n = 132; 31.1%), 18.6% ( n = 79) were unsure, 12.3% ( n = 52) believed it was no different, and 9.0% ( n = 38) believed it was better.

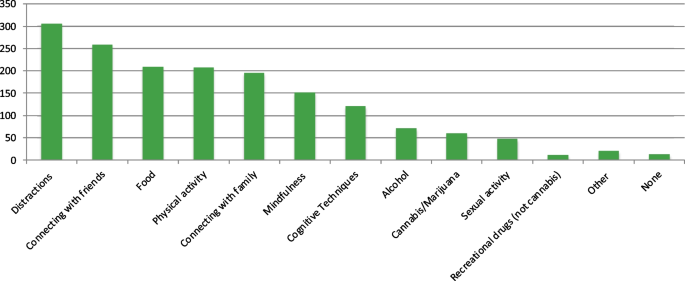

When asked about the campus environment and resources, most participants ( n = 321; 73.6%) indicated that they had not experienced any form of harassment on campus. However, 17.9% ( n = 78) of participants experienced verbal harassment, followed by cyber harassment ( n = 27; 6.2%), sexual harassment ( n = 25; 5.7%), and physical harassment ( n = 22; 5.0%). Most students ( n = 267; 61.7%) did not have accommodations such as extra test time or separate exam rooms. Some students ( n = 151; 34.9%) reported not using mental health services during their post-secondary studies. However, 34.6% ( n = 150) of students used the student wellness services offered by their institutions, and 25.4% ( n = 110) used mental health services provided outside their post-secondary institution. Participants also used several different strategies to cope with stress (Fig. 3 ). The most frequently used approach was distractive behaviours such as hobbies ( n = 305; 70.4%), followed by connecting with friends ( n = 258; 59.6%), food ( n = 209; 48.3%), and physical activity ( n = 208; 48.0%).

Strategies used to cope with stress

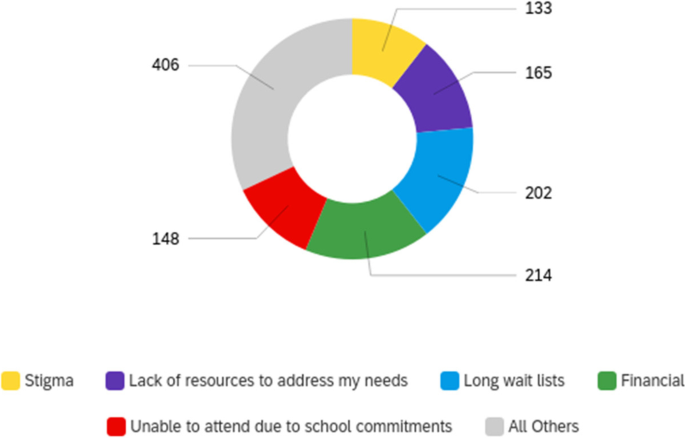

The most frequently reported barriers to mental health care were financial ( n = 214; 50.5%), long wait lists ( n = 202; 47.6%), lack of resources to address needs ( n = 165; 38.9%), inability to receive care due to school commitments ( n = 148; 34.9%), stigma ( n = 133; 31.4%), cultural barriers ( n = 108; 25.4%), and past negative experiences with mental health care ( n = 86; 20.3%). Only 8.3% ( n = 35) of respondents indicated no barriers to receiving care. Respondents who indicated “other” (5.0%, n = 21) listed accessibility issues ( n = 4; 19.0%), anxiety or social anxiety preventing treatment-seeking ( n = 2; 9.5%), work commitments ( n = 2), and apathy ( n = 2; Fig. 4 ).

Perceived barriers to care (response count)

Mental health care

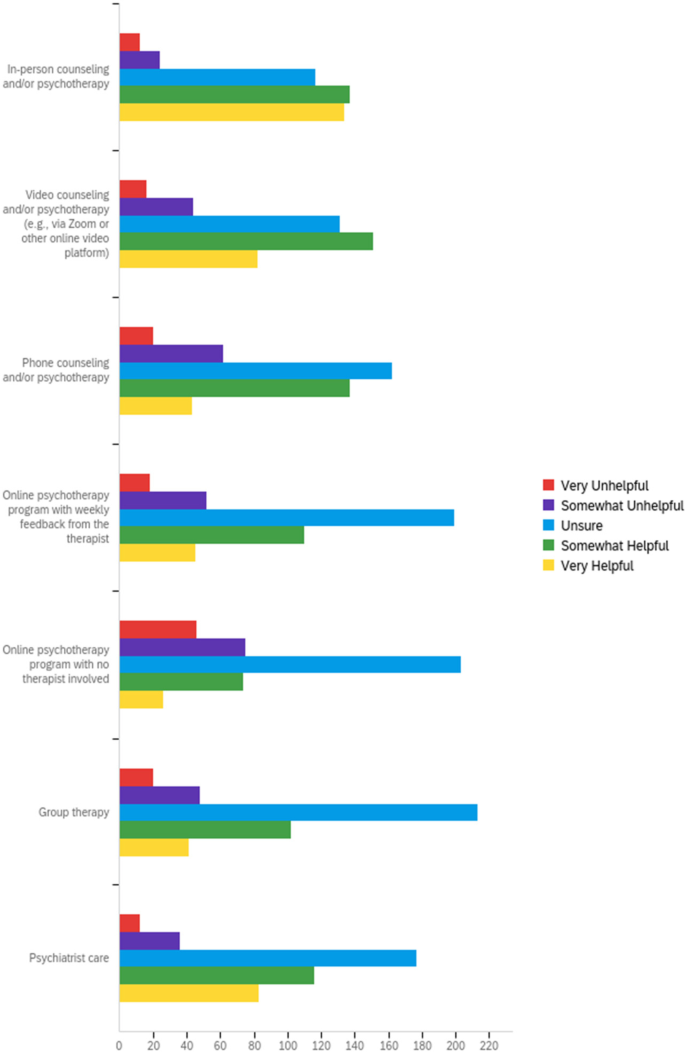

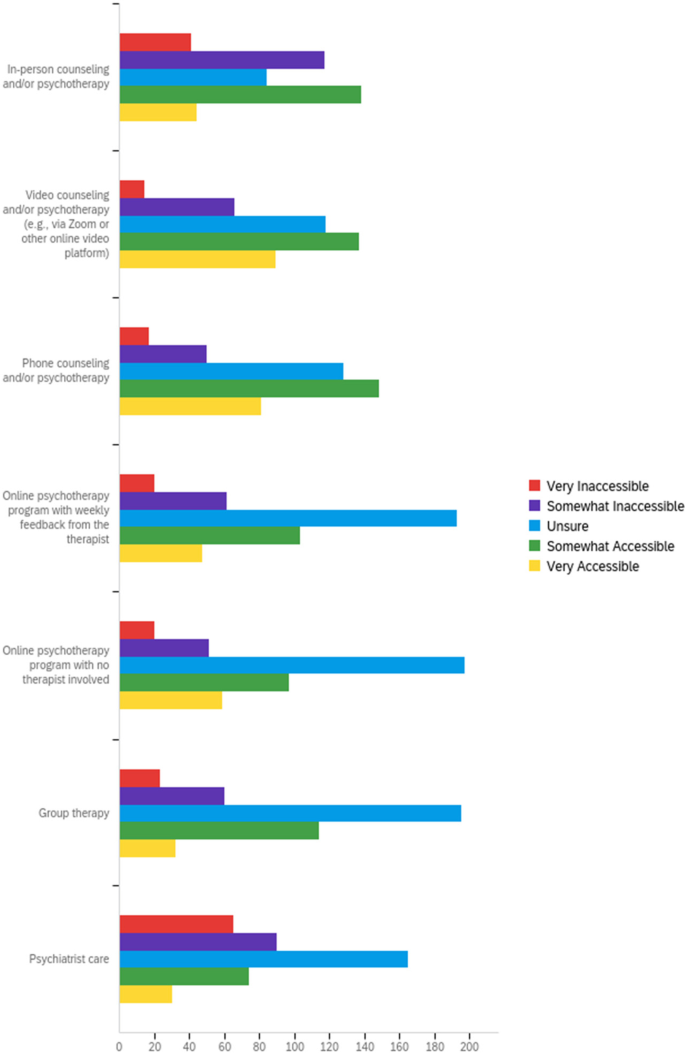

A sizeable proportion of participants were unsure about the helpfulness of different forms of mental health care (Fig. 5 ). Although in-person services were frequently rated as helpful ( n = 271; 63.9%), the perceptions of accessibility were nearly equally divided, with 42.9% finding this delivery type accessible and 37.3% finding it inaccessible (Fig. 6 ). By contrast, the fewest participants rated online psychotherapy with no therapist involved as helpful ( n = 100; 23.6%). However, 36.8% ( n = 156) found this delivery type to be accessible. Similar to perceptions of helpfulness, most respondents were unsure about the accessibility of the different care deliveries, particularly those in online or group therapy formats. Most of the individuals who were unsure about the helpfulness or accessibility of mental health care services were not receiving medication or psychotherapy (Additional file 2 ).

Perception of care helpfulness

Perception of care accessibility

When focusing on post-secondary mental health services, 46.9% ( n = 196) of respondents believed they had a good understanding of the mental health resources offered by their institution. The exact number of participants ( n = 167; 40%) were either neutral or agreed that their institution's mental health programs and services were adequate. At the same time, 73.2% ( n = 306) of students believed that post-secondary mental health resources need to be increased. Most students ( n = 186; 44.5%) did not feel comfortable reaching out to faculty members or staff to access support for their mental health, although most were either neutral ( n = 137; 30.4%) or agreed ( n = 181; 43.3%) that institutional staff promoted mental health resources. Most individuals were also neutral ( n = 160; 38.3%) when asked if they prefer using services outside their institutions. At the same time, most participants ( n = 187; 45.6%) did not believe they could afford private mental health care, despite 61.2% ( n = 251) being aware of resources outside their institutions. Most participants were neutral ( n = 172; 42%) or agreed ( n = 157; 38.3%) that mental health services outside their campuses were more accessible. Most individuals ( n = 186; 45.4%) also preferred using services outside of their institution, even though most were neutral ( n = 210; 51.2%) about whether the quality of the service was superior to those on campus.

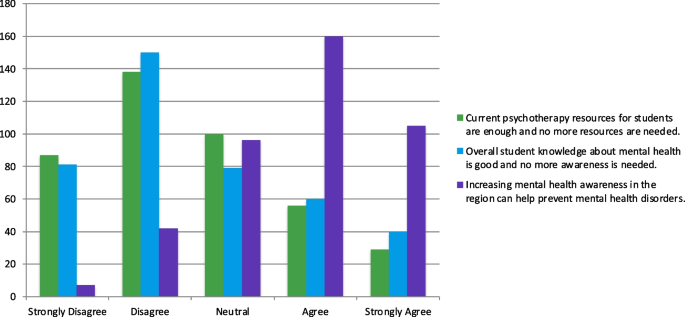

Many students ( n = 231; 56.5%) believed that greater awareness about mental health is necessary and that increasing awareness in the region could prevent mental health disorders ( n = 265; 64.6%; Fig. 7 ). Students also believed that current psychotherapy resources were insufficient and that more resources were needed ( n = 225; 54.9%).

Opinions on mental health awareness and psychotherapy resources

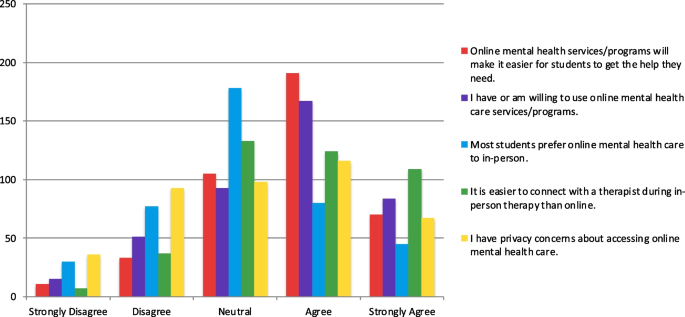

Finally, when exploring the perception of online mental health care, students were relatively divided about their preference for online and in-person care, with most being neutral ( n = 178; 43.4%; Fig. 8 ). At the same time, most had or were willing to use online mental health care services ( n = 251; 61.2%). Although online mental health care was believed to make it easier for students to get the help they need ( n = 261; 63.7%), many thought it was easier to connect with therapists in-person than online ( n = 233; 56.8%). A large number of participants also expressed that they had privacy concerns accessing online mental health care ( n = 183; 44.6%).

Opinions on online mental health care

Qualitative data

Initially, 155 participants (34.6%) responded when asked in the survey whether they had any additional feedback to share. After removing irrelevant content (i.e., responses with “no” or “not applicable” without follow-up statements), a final set of n = 110 (24.6%) feedback responses were coded. Agreement between the coders was moderate, κ = 0.53, (95% CI, 0.64 to 0.42), p < 0.001. After resolving discrepancies, seven categories and 24 subcategories emerged from the data (Table 3 ). Personal strategies ( n = 35; 31.82%) and the need for mental health education ( n = 29; 26.36%) were the most frequently expressed categories. Personal strategies were suggested by respondents and mostly stressed interpersonal skills ( n = 9) to improve social connections, methods to enhance self-awareness ( n = 7) and self-regulation ( n = 5), and lifestyle changes ( n = 5). Concerning mental health education, most feedback centred on the need to develop a formal course ( n = 16) with content focused on personal strategies ( n = 7). The most frequently discussed service and support focused on the need for guidance and counselling ( n = 6). Three respondents also highlighted the institution’s role, particularly the need for support from faculty and staff. The feedback about awareness mostly centred around highlighting its importance ( n = 10). The few environmental risk factors described digital online technology ( n = 1), systemic factors ( n = 2), and COVID-19 ( n = 2). Further, changes to the post-secondary learning environment were related to improving time management by extending the years needed to complete a degree and spreading out the course workload ( n = 2). One person also suggested improving institutional hardware and software. Lastly, participants who provided survey feedback ( n = 11; 10%) thanked the researchers for the survey ( n = 6) and offered suggestions to improve the survey ( n = 4). Changes pertained to a question using the term “prevention” rather than “treatment,” including an “I don’t know” option in some parts of the survey, a technical error where a blank question was visible, and the consideration of student diversity in mental health status. A comparison of demographic data between all survey respondents and those who provided qualitative feedback demonstrated significant differences (Additional file 3 ). Participants who provided feedback were mostly men, male, and single (Additional file 3 ). Furthermore, the ratio of white to black respondents was reduced from 3.75 times amongst all survey respondents to 1.74 times in participants who provided qualitative feedback.

The current study explored the mental health challenges and care needs of post-secondary students in the post-lockdown COVID-19 pandemic period (May to June 5, 2022). To capture this data, the Post-Secondary Student Mental Health Experience Survey was developed and made available to students within Ontario, Canada. Approximately 0.05% of the postsecondary population in the province (448 out of 903, 780 individuals [ 31 ]) responded to the survey. A decline in mental health was reported by post-secondary students since starting their studies. Although there was a greater preference for in-person treatments, many students used online mental health interventions. However, there was uncertainty about the helpfulness and accessibility of different in-person and online interventions. Several limitations to care were also expressed, including the need to improve mental health awareness, education, and care resources.

In line with the current body of studies, the most prevalent mental health disorders among students were depression and anxiety [ 32 ]. In students not formally diagnosed, the majority experienced mental health concerns and indicated a decline in their mental health since starting their post-secondary education. Indeed, post-secondary students are considered an at-risk population for chronic stress and poor mental health [ 33 ]. The current study provided additional details on how these symptoms present themselves—namely in the form of compromised concentration, symptoms of anxiety and depression, mood swings, panic attacks, problematic use of alcohol and other recreational drugs, and problems with sleep. Given the number of hours students work and engage in extracurricular activities, it is unsurprising that the majority surveyed lacked time to focus on their mental health. The pressures to meet the increased cost of living, combined with the competitiveness of the current job market, can put students at higher odds of experiencing anxiety and depression [ 34 ].

Much of the mental health needs of the sample focused on education, strategies, and tools. Although most students believed they had good mental health knowledge and offered personal strategies in the survey feedback, they could not effectively manage their concerns. These findings provide some insight into the importance of distinguishing between knowledge acquisition and knowledge use. Health knowledge can influence health behaviours and attitudes, even during the pandemic [ 35 ]. However, the current body of studies has presented caveats to the positive association between health knowledge and health behaviours. For example, one pilot study demonstrated that consumers of self-help books might present more significant symptoms of stress compared to nonconsumers [ 36 ]. In social media-based research, a gap was identified between health knowledge acquisition, intention, and health behaviours. This gap was influenced by several factors, including fear, trust, credibility, and perceived efficacy [ 37 ]. Moreover, nearly one in four students in the current study reported being subjected to some form of harassment on campus despite relevant policies, educational resources, and initiatives available to the community [ 38 ]. While it is beyond the scope of this study, future studies should examine the disconnect between knowledge and action—frequently termed the G.I Joe Phenomena [ 39 ]—in the context of post-secondary mental health education development. This is especially important considering that one of the most predominant feedback from participants was the need for mental health-based courses that focused on teaching personal coping strategies. In line with the theme of knowledge acquisition, most students also believed in the importance of high school mental health education. High school psychoeducation can help students transition to post-secondary school [ 40 ] by providing resources and support, enhancing student mental health literacy and hygiene, improving psychological resilience, and mitigating distorted thought processing [ 41 , 42 ]. At the same time, a more robust evidence base is needed to support effective mental health promotion strategies from a young age [ 43 ]. Taken together, how and when information should be disseminated to students to evoke actionable change requires further investigation.

Regarding treatment-seeking and care needs, many students were unsure about the accessibility and helpfulness of the treatments offered. Privacy and confidentiality, communication concerns, and the quality of resources may impact acceptability and engagement with different delivery methods [ 44 ]. In addition, most of the students surveyed were not diagnosed with a mental health disorder, which may partially explain these trends. The high level of stigma that exists in this population may also limit knowledge about the resources offered. These factors further support programs that inform students of available resources. Considering the risk of developing or worsening mental health symptoms in this population, institutions may benefit from proactive measures that increase mental health awareness and knowledge of resources. Programs with these aims have successfully reduced stigma and increased resiliency and help-seeking [ 45 ]. How these approaches impact campus accommodation use and treatment-seeking are important considerations for future research [ 46 ]. Similar to other populations [ 47 ], delivery methods with therapists were more frequently perceived as accessible and helpful. The emergent categories of interpersonal skills, peer support, and counselling and guidance within the qualitative findings also support the association between human connection and mental health. Future studies should investigate whether the same benefits exist with paraprofessionals (e.g., peer supporters, lay counsellors, and other non-clinicians) since improved outcomes have been observed in digital mental health interventions that employ such personnel [ 48 ]. Despite the greater preference for in-person mental health care and increased therapist involvement, students expressed challenges in seeking help due to financial constraints, long wait times, and lack of time to focus on mental health. Online resources benefit from integrating cost-effectiveness, time flexibility, and rapid availability to alleviate some barriers to care [ 49 , 50 ].

The study is one of few that investigates the mental health challenges and care needs of post-secondary students in the post-lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the novelty of this study serves as its strength, some of its limitations must also be mentioned. A smaller region was used to pilot the survey before administering it to a larger population. Since all survey advertisements occurred through social media, there is the possibility of volunteer bias. A lack of paid advertisement may have also limited reach to include only students who access the groups and platforms the survey was advertised on. The substantial increase in technology use to connect with others can make social media a feasible tool for survey recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 51 ]. However, as students return to campus, future recruitment strategies should consider partnerships with teaching faculty and institutional and student organizations that can build trust and enhance reach amongst postsecondary students. Further, although the sample size and handling of missing data were adequate for the study’s descriptive analysis, some factors were not weighted similarly due to different response rates. While this may be a limitation, the pilot survey provided opportune conditions to re-assess the survey items and add “I don’t know,” “unsure,” or “prefer not to answer” options to discourage skipping items. A suggestion to include “does not apply” was also expressed by a participant in the qualitative feedback. The response rates were sufficient for all items, except when students were asked if they were taking medication for their mental health. When given only “yes” or “no” options, the response rate for this item was approximately 58%. Although the aforementioned options will be added to the next iteration of the survey, future studies should investigate the potential role of self-stigma on response rates within anonymous mental health surveys [ 52 ].

Nevertheless, the current findings indicated that mental health worsens throughout post-secondary education in the study population. Therefore, the survey will also be revised to include whether current mental health diagnoses were received before or after participants commenced their post-secondary studies. This information is critical in evaluating how symptoms and experiences manifest and differ in newly diagnosed patients versus those with longer experiences with mental health challenges. Another limitation of the study was that most respondents were not diagnosed with mental health disorders, and there were few members of equity-seeking and equity-deserving groups. Students who identify with these communities typically face additional stressors that increase their risk of mental health concerns [ 53 , 54 ]. In addition, significant differences were observed in some of the demographic characteristics of feedback providers. Namely, men and males comprised most of the qualitative responders, whereas survey responders as a whole were mostly women and female. Furthermore, the ratio of white to black respondents was substantially reduced in the group that provided additional feedback. While not the main objective of this study, these patterns highlight the importance of designing inclusive surveys that provide a platform for traditionally less vocal groups to express their mental health needs [ 55 , 56 ]. Future studies may need to implement procedures to build community trust and encourage survey completion by students in these groups. These data are critical in informing equitable mental health care and resources.

The current study highlighted the need for more accessible mental health resources for students across the mental health spectrum. Institutions may benefit from developing formal courses with coping mechanisms and other tools, skills, and strategies to inspire action-based changes in students suffering from poor mental health. Financial constraints, lack of time, stigma, and long wait times are all factors that can reduce treatment-seeking and worsen mental health. Strategic methods to enhance mental health awareness and knowledge also have the potential to clarify the uncertainty that students have about the helpfulness and accessibility of different care delivery types. Although therapist guidance was viewed positively, future studies should explore how online therapist guidance can improve sentiment towards online care—a delivery type frequently used during the pandemic.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Wiens K, Bhattarai A, Dores A, Pedram P, Williams J, Bulloch A, et al. Mental Health among Canadian Postsecondary Students: A Mental Health Crisis? Can J Psychiatry Rev Can Psychiatr. 2020;65(1):30–5.

Article Google Scholar

Evans TM, Bira L, Gastelum JB, Weiss LT, Vanderford NL. Evidence for a mental health crisis in graduate education. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36(3):282–4.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Esmaeelzadeh S, Moraros J, Thorpe L, Bird Y. The association between depression, anxiety and substance use among Canadian post-secondary students. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:3241–51.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ogrodniczuk JS, Kealy D, Laverdière O. Who is coming through the door? A national survey of self-reported problems among post-secondary school students who have attended campus mental health services in Canada. Couns Psychother Res. 2021;21(4):837–45.

American College Health Association. National College Health Assessment [Internet]. 2017. Available from: http://www.acha-ncha.org/reports_ACHANCHAIIc.%0Dhtml .

American College Health Association. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Ontario Canada Reference Group Executive Summary Spring 2019. Silver Spring, MD: American College Health Association; 2019.

Chacón-Cuberos R, Zurita-Ortega F, Olmedo-Moreno EM, Castro-Sánchez M. Relationship between Academic Stress, Physical Activity and Diet in University Students of Education. Behav Sci. 2019;9(6):59–59.

Chiauzzi E, Brevard J, Thurn C, Decembrele S, Lord S. MyStudentBody–Stress: An Online Stress Management Intervention for College Students. J Health Commun. 2008;13(6):555–72.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Smith L, Disler R, Watson K. Physical activity and dietary habits of first year nursing students: An Australian dual-method study. Collegian. 2020;27(5):535–41.

Ng P, Padjen M. An overview of post-secondary mental health on campuses in Ontario: challenges and successes. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2019;17(3):531–41.

Jaworska N, De Somma E, Fonseka B, Heck E, MacQueen GM. Mental Health Services for Students at Postsecondary Institutions: A National Survey. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(12):766–75.

Gotlib D, Saragoza P, Segal S, Goodman L, Schwartz V. Evaluation and Management of Mental Health Disability in Post-secondary Students. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(6):43.

Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R, Alonso J, Benjet C, Cuijpers P, et al. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018;127(7):623–38.

Marsh CN, Wilcoxon SA. Underutilization of Mental Health Services Among College Students: An Examination of System-Related Barriers. J Coll Stud Psychother. 2015;29(3):227–43.

Dunley P, Papadopoulos A. Why Is It So Hard to Get Help? Barriers to Help-Seeking in Postsecondary Students Struggling with Mental Health Issues: a Scoping Review. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2019;17(3):699–715.

Ontario College Health Association. Towards a comprehensive mental health strategy: the crucial role of colleges and universities as partners [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2022 May 16]. Available from: http://www.oucha.ca/pdf/mental_health/2009_12_OUCHA_Mental_Health_Report.pdf

Mowbray C, Megivern D, Mandiberg J. Campus MHS: recommendations for change. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(2):226–37.

Zhu J, Racine N, Xie EB, Park J, Watt J, Eirich R, et al. Post-secondary student mental health during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:777251.

Ewing L, Hamza CA, Walsh K, Goldstein AL, Heath NL. A Qualitative Investigation of the Positive and Negative Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Post-Secondary Students’ Mental Health and Well-Being. Emerg Adulthood. 2022;10(5):1312–27.

Li Y, Wang A, Wu Y, Han N, Huang H. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of College Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol. 2021;12:669119.

Huilgol YS, Torous J, Gold JA, Goldman ML. Telemental health policies for college students during COVID-19. J Am Coll Health J ACH. 2021;23:1–5.

Google Scholar

Kwan MYW, Brown D, MacKillop J, Beaudette S, Van Koughnett S, Munn C. Evaluating the impact of Archway: a personalized program for 1st year student success and mental health and wellbeing. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):59.

Wasil AR, Taylor ME, Franzen RE, Steinberg JS, DeRubeis RJ. Promoting Graduate Student Mental Health During COVID-19: Acceptability, Feasibility, and Perceived Utility of an Online Single-Session Intervention. Front Psychol. 2021;12:569785.

Seko Y, Meyer J, Bonghanya R, Honiball L. Mental health support for Canadian postsecondary students during COVID-19 pandemic: An environmental scan. J Am Coll Health. 2022;4(0):0–5.

Liu CH, Pinder-Amaker S, Hahm HC, Chen JA. Priorities for addressing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on college student mental health. J Am Coll Health. 2022;70(5):1356–8.

Copeland WE, McGinnis E, Bai Y, Adams Z, Nardone H, Devadanam V, et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on College Student Mental Health and Wellness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60(1):134-141.e2.

Bergman A, Chinco A, Hartzmark SM, Sussman AB. Survey curious? Start-up guide and best practices for running surveys and experiments online. Econometrics: Econometric & Statistical Methods - Special Topics eJournal. 2020:n. pag.

Krippendorff K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications; 2019.

Book Google Scholar

Neuendorf KA. Content analysis and thematic analysis. In: Advanced research methods for applied psychology. Milton Park: Routledge; 2018. p. 211–23.

Chapter Google Scholar

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Statistics Canada. Table 37-10-0011-01 Postsecondary enrolments, by field of study, registration status, program type, credential type and gender. 2022. https://doi.org/10.25318/3710001101-eng .

Deng J, Zhou F, Hou W, Silver Z, Wong CY, Chang O, et al. The prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance in higher education students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;301:113863.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Linden B, Stuart H. Post-Secondary Stress and Mental Well-Being: A Scoping Review of the Academic Literature. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2020;39(1):1–32.

Posselt J. Discrimination, competitiveness, and support in US graduate student mental health. Stud Grad Postdr Educ. 2021;12(1):89–112.

Rincón Uribe FA, de Souza Godinho RC, Machado MAS, Oliveira KR da SG, Neira Espejo CA, de Sousa NCV, et al. Health knowledge, health behaviors and attitudes during pandemic emergencies: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2021;16(9):e0256731.

Raymond C, Marin MF, Hand A, Sindi S, Juster RP, Lupien SJ. Salivary cortisol levels and depressive symptomatology in consumers and nonconsumers of self-help books: a pilot study. Neural Plast. 2016;2016:3136743.

Chaoguang H, Feicheng M, Yifei Q, Yuchao W. Exploring the determinants of health knowledge adoption in social media: An intention-behavior-gap perspective. Inf Dev. 2018;34(4):346–63.

Cismaru M, Cismaru R. Protecting University Students from Bullying and Harassment: A Review of the Initiatives at Canadian Universities. Contemp Issues Educ Res. 2018;11(4):145–52.

Kristal AS, Santos LR. GI Joe phenomena: understanding the limits of metacognitive awareness on debiasing. No 21–084. Harvard Business School Working Paper; 2021. p. 1–54.

Kutcher S, Wei Y. School mental health: a necessary component of youth mental health policy and plans. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(2):174–5.

Şahin H, Türk F. The Impact of Cognitive-Behavioral Group Psycho-Education Program on Psychological Resilience, Irrational Beliefs, and Well-Being. J Ration-Emotive Cogn-Behav Ther. 2021;39(4):672–94.

Sapru I, Khalid-Khan S, Choi E, Alavi N, Patel A, Sutton C, et al. Effectiveness of online versus live multi-family psychoeducation group therapy for children and adolescents with mood or anxiety disorders: a pilot study. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2018;30(4). https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2016-0069 .

O’Reilly M, Svirydzenka N, Adams S, Dogra N. Review of mental health promotion interventions in schools. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(7):647–62.

Chan JK, Farrer LM, Gulliver A, Bennett K, Griffiths KM. University Students’ Views on the Perceived Benefits and Drawbacks of Seeking Help for Mental Health Problems on the Internet: A Qualitative Study. JMIR Hum Factors. 2016;3(1):e4765.

Szeto AC, Henderson L, Lindsay BL, Knaak S, Dobson KS. Increasing resiliency and reducing mental illness stigma in post-secondary students: A meta-analytic evaluation of the inquiring mind program. J Am Coll Health. 2021;1–11.

Condra M, Dineen M, Gills H, Jack-Davies A, Condra E. Academic Accommodations for Postsecondary Students with Mental Health Disabilities in Ontario, Canada: A Review of the Literature and Reflections on Emerging Issues. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2015;28(3):277–91.

Saddichha S, Al-Desouki M, Lamia A, Linden IA, Krausz M. Online interventions for depression and anxiety – a systematic review. Health Psychol Behav Med. 2014;2(1):841–81.

Leung C, Pei J, Hudec K, Shams F, Munthali R, Vigo D. The Effects of Nonclinician Guidance on Effectiveness and Process Outcomes in Digital Mental Health Interventions: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(6):e36004.

Donker T, Blankers M, Hedman E, Ljotsson B, Petrie K, Christensen H. Economic evaluations of Internet interventions for mental health: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2015;45(16):3357–76.

Montagni I, Tzourio C, Cousin T, Sagara JA, Bada-Alonzi J, Horgan A. Mental health-related digital use by university students: a systematic review. Telemed E-Health. 2020;26(2):131–46.

Purewal S, Ardiles P, Di Ruggiero E, Flores JVL, Mahmood S, Elhagehassan H. Using social media as a survey recruitment strategy for post-secondary students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Inq J Med Care Organ Provis Financ. 2021;58:1–9.

Cinculova A, Prasko J, Kamaradova D, Ociskova M, Latalova K, Vrbova K, Tichackova A. Adherence, self-stigma and discontinuation of pharmacotherapy in patients with anxiety disorders–cross-sectional study. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2017;38(6):429–36.

PubMed Google Scholar

Aguilar O, Lipson SK. A Public Health Approach to Understanding the Mental Health Needs of College Students with Disabilities: Results from a National Survey. J Postsecond Educ Disabil. 2021;34(3):273–85.

Lisnyj KT, Pearl DL, McWhirter JE, Papadopoulos A. Exploration of Factors Affecting Post-Secondary Students’ Stress and Academic Success: Application of the Socio-Ecological Model for Health Promotion. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):3779.

Taylor RE, Kuo BC. Black American psychological help-seeking intention: An integrated literature review with recommendations for clinical practice. J Psychother Integr. 2019;29(4):325.

Brown JS, Sagar-Ouriaghli I, Sullivan L. Help-seeking among men for mental health problems. In: The Palgrave Handbook of male psychology and mental health. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2019. p. 397–415.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Healthy Cities Implementation Science (HCIS) Team Grant (File #: RN458719—473591).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Health Sciences, Queen’s University, 166 Brock Street, Kingston, ON, K7L 5G2, Canada

Elnaz Moghimi, Callum Stephenson, Gilmar Gutierrez, Charmy Patel, Oyedeji Ayonrinde, Sarosh Khalid-Khan, Roumen Milev, Claudio Soares, Mohsen Omrani & Nazanin Alavi

Waypoint Research Institute, Waypoint Centre for Mental Health Care, Penetanguishene, Canada

Elnaz Moghimi

Centre for Neuroscience Studies, Faculty of Health Sciences, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

Jasleen Jagayat, Gina Layzell, Roumen Milev & Nazanin Alavi

Student Wellness Services, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

Amber McCart & Cynthia Gibney

Wellness, Accessibility & Student Success, St. Lawrence College, Kingston, ON, Canada

Caryn Langstaff

School of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

Erna Snelgrove-Clarke

OPTT Inc, Toronto, ON, Canada

Mohsen Omrani & Nazanin Alavi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

EM, CaS, MO, and NA were responsible for the study design. EM, CaS, JJ, GL, CP and NA were responsible for developing and administering the survey. Data analysis and drafting of the manuscript were conducted by EM, CaS, and GG. Subsequent drafts of the manuscript were edited and finalized by all authors. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nazanin Alavi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval was obtained from the Queen’s University Health Sciences and Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Research Ethics Board (HSREB) in Kingston, Canada. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants provided informed consent online before accessing the survey.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

NA and MO cofounded an online care delivery platform (i.e., OPTT) and have ownership stakes in OPTT Inc.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1., additional file 2:.

Appendix 2. Perceived helpfulness and accessibility of treatments in survey respondents currently receiving psychotherapy/counseling and medication for their mental health.

Additional file 3:

Table 4. Demographic data of qualitative respondents. Statistical analysis compared data of qualitative respondents and all survey respondents. All p values are two-tailed and α = 0.05.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Moghimi, E., Stephenson, C., Gutierrez, G. et al. Mental health challenges, treatment experiences, and care needs of post-secondary students: a cross-sectional mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health 23 , 655 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15452-x

Download citation

Received : 29 November 2022

Accepted : 15 March 2023

Published : 06 April 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15452-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mental health

- Student mental health

- Mental health treatment

- Psychotherapy

- Post-secondary students

- University and college mental health

- Young-adult mental health

- Treatment perception

- Online mental health treatment

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 14 December 2021

Bullying at school and mental health problems among adolescents: a repeated cross-sectional study

- Håkan Källmén 1 &

- Mats Hallgren ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0599-2403 2

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health volume 15 , Article number: 74 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

89k Accesses

13 Citations

30 Altmetric

Metrics details

To examine recent trends in bullying and mental health problems among adolescents and the association between them.

A questionnaire measuring mental health problems, bullying at school, socio-economic status, and the school environment was distributed to all secondary school students aged 15 (school-year 9) and 18 (school-year 11) in Stockholm during 2014, 2018, and 2020 (n = 32,722). Associations between bullying and mental health problems were assessed using logistic regression analyses adjusting for relevant demographic, socio-economic, and school-related factors.

The prevalence of bullying remained stable and was highest among girls in year 9; range = 4.9% to 16.9%. Mental health problems increased; range = + 1.2% (year 9 boys) to + 4.6% (year 11 girls) and were consistently higher among girls (17.2% in year 11, 2020). In adjusted models, having been bullied was detrimentally associated with mental health (OR = 2.57 [2.24–2.96]). Reports of mental health problems were four times higher among boys who had been bullied compared to those not bullied. The corresponding figure for girls was 2.4 times higher.

Conclusions

Exposure to bullying at school was associated with higher odds of mental health problems. Boys appear to be more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of bullying than girls.

Introduction

Bullying involves repeated hurtful actions between peers where an imbalance of power exists [ 1 ]. Arseneault et al. [ 2 ] conducted a review of the mental health consequences of bullying for children and adolescents and found that bullying is associated with severe symptoms of mental health problems, including self-harm and suicidality. Bullying was shown to have detrimental effects that persist into late adolescence and contribute independently to mental health problems. Updated reviews have presented evidence indicating that bullying is causative of mental illness in many adolescents [ 3 , 4 ].

There are indications that mental health problems are increasing among adolescents in some Nordic countries. Hagquist et al. [ 5 ] examined trends in mental health among Scandinavian adolescents (n = 116, 531) aged 11–15 years between 1993 and 2014. Mental health problems were operationalized as difficulty concentrating, sleep disorders, headache, stomach pain, feeling tense, sad and/or dizzy. The study revealed increasing rates of adolescent mental health problems in all four counties (Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Denmark), with Sweden experiencing the sharpest increase among older adolescents, particularly girls. Worsening adolescent mental health has also been reported in the United Kingdom. A study of 28,100 school-aged adolescents in England found that two out of five young people scored above thresholds for emotional problems, conduct problems or hyperactivity [ 6 ]. Female gender, deprivation, high needs status (educational/social), ethnic background, and older age were all associated with higher odds of experiencing mental health difficulties.

Bullying is shown to increase the risk of poor mental health and may partly explain these detrimental changes. Le et al. [ 7 ] reported an inverse association between bullying and mental health among 11–16-year-olds in Vietnam. They also found that poor mental health can make some children and adolescents more vulnerable to bullying at school. Bayer et al. [ 8 ] examined links between bullying at school and mental health among 8–9-year-old children in Australia. Those who experienced bullying more than once a week had poorer mental health than children who experienced bullying less frequently. Friendships moderated this association, such that children with more friends experienced fewer mental health problems (protective effect). Hysing et al. [ 9 ] investigated the association between experiences of bullying (as a victim or perpetrator) and mental health, sleep disorders, and school performance among 16–19 year olds from Norway (n = 10,200). Participants were categorized as victims, bullies, or bully-victims (that is, victims who also bullied others). All three categories were associated with worse mental health, school performance, and sleeping difficulties. Those who had been bullied also reported more emotional problems, while those who bullied others reported more conduct disorders [ 9 ].

As most adolescents spend a considerable amount of time at school, the school environment has been a major focus of mental health research [ 10 , 11 ]. In a recent review, Saminathen et al. [ 12 ] concluded that school is a potential protective factor against mental health problems, as it provides a socially supportive context and prepares students for higher education and employment. However, it may also be the primary setting for protracted bullying and stress [ 13 ]. Another factor associated with adolescent mental health is parental socio-economic status (SES) [ 14 ]. A systematic review indicated that lower parental SES is associated with poorer adolescent mental health [ 15 ]. However, no previous studies have examined whether SES modifies or attenuates the association between bullying and mental health. Similarly, it remains unclear whether school related factors, such as school grades and the school environment, influence the relationship between bullying and mental health. This information could help to identify those adolescents most at risk of harm from bullying.

To address these issues, we investigated the prevalence of bullying at school and mental health problems among Swedish adolescents aged 15–18 years between 2014 and 2020 using a population-based school survey. We also examined associations between bullying at school and mental health problems adjusting for relevant demographic, socioeconomic, and school-related factors. We hypothesized that: (1) bullying and adolescent mental health problems have increased over time; (2) There is an association between bullying victimization and mental health, so that mental health problems are more prevalent among those who have been victims of bullying; and (3) that school-related factors would attenuate the association between bullying and mental health.

Participants

The Stockholm school survey is completed every other year by students in lower secondary school (year 9—compulsory) and upper secondary school (year 11). The survey is mandatory for public schools, but voluntary for private schools. The purpose of the survey is to help inform decision making by local authorities that will ultimately improve students’ wellbeing. The questions relate to life circumstances, including SES, schoolwork, bullying, drug use, health, and crime. Non-completers are those who were absent from school when the survey was completed (< 5%). Response rates vary from year to year but are typically around 75%. For the current study data were available for 2014, 2018 and 2020. In 2014; 5235 boys and 5761 girls responded, in 2018; 5017 boys and 5211 girls responded, and in 2020; 5633 boys and 5865 girls responded (total n = 32,722). Data for the exposure variable, bullied at school, were missing for 4159 students, leaving 28,563 participants in the crude model. The fully adjusted model (described below) included 15,985 participants. The mean age in grade 9 was 15.3 years (SD = 0.51) and in grade 11, 17.3 years (SD = 0.61). As the data are completely anonymous, the study was exempt from ethical approval according to an earlier decision from the Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (2010-241 31-5). Details of the survey are available via a website [ 16 ], and are described in a previous paper [ 17 ].

Students completed the questionnaire during a school lesson, placed it in a sealed envelope and handed it to their teacher. Student were permitted the entire lesson (about 40 min) to complete the questionnaire and were informed that participation was voluntary (and that they were free to cancel their participation at any time without consequences). Students were also informed that the Origo Group was responsible for collection of the data on behalf of the City of Stockholm.

Study outcome

Mental health problems were assessed by using a modified version of the Psychosomatic Problem Scale [ 18 ] shown to be appropriate for children and adolescents and invariant across gender and years. The scale was later modified [ 19 ]. In the modified version, items about difficulty concentrating and feeling giddy were deleted and an item about ‘life being great to live’ was added. Seven different symptoms or problems, such as headaches, depression, feeling fear, stomach problems, difficulty sleeping, believing it’s great to live (coded negatively as seldom or rarely) and poor appetite were used. Students who responded (on a 5-point scale) that any of these problems typically occurs ‘at least once a week’ were considered as having indicators of a mental health problem. Cronbach alpha was 0.69 across the whole sample. Adding these problem areas, a total index was created from 0 to 7 mental health symptoms. Those who scored between 0 and 4 points on the total symptoms index were considered to have a low indication of mental health problems (coded as 0); those who scored between 5 and 7 symptoms were considered as likely having mental health problems (coded as 1).

Primary exposure

Experiences of bullying were measured by the following two questions: Have you felt bullied or harassed during the past school year? Have you been involved in bullying or harassing other students during this school year? Alternatives for the first question were: yes or no with several options describing how the bullying had taken place (if yes). Alternatives indicating emotional bullying were feelings of being mocked, ridiculed, socially excluded, or teased. Alternatives indicating physical bullying were being beaten, kicked, forced to do something against their will, robbed, or locked away somewhere. The response alternatives for the second question gave an estimation of how often the respondent had participated in bullying others (from once to several times a week). Combining the answers to these two questions, five different categories of bullying were identified: (1) never been bullied and never bully others; (2) victims of emotional (verbal) bullying who have never bullied others; (3) victims of physical bullying who have never bullied others; (4) victims of bullying who have also bullied others; and (5) perpetrators of bullying, but not victims. As the number of positive cases in the last three categories was low (range = 3–15 cases) bully categories 2–4 were combined into one primary exposure variable: ‘bullied at school’.

Assessment year was operationalized as the year when data was collected: 2014, 2018, and 2020. Age was operationalized as school grade 9 (15–16 years) or 11 (17–18 years). Gender was self-reported (boy or girl). The school situation To assess experiences of the school situation, students responded to 18 statements about well-being in school, participation in important school matters, perceptions of their teachers, and teaching quality. Responses were given on a four-point Likert scale ranging from ‘do not agree at all’ to ‘fully agree’. To reduce the 18-items down to their essential factors, we performed a principal axis factor analysis. Results showed that the 18 statements formed five factors which, according to the Kaiser criterion (eigen values > 1) explained 56% of the covariance in the student’s experience of the school situation. The five factors identified were: (1) Participation in school; (2) Interesting and meaningful work; (3) Feeling well at school; (4) Structured school lessons; and (5) Praise for achievements. For each factor, an index was created that was dichotomised (poor versus good circumstance) using the median-split and dummy coded with ‘good circumstance’ as reference. A description of the items included in each factor is available as Additional file 1 . Socio-economic status (SES) was assessed with three questions about the education level of the student’s mother and father (dichotomized as university degree versus not), and the amount of spending money the student typically received for entertainment each month (> SEK 1000 [approximately $120] versus less). Higher parental education and more spending money were used as reference categories. School grades in Swedish, English, and mathematics were measured separately on a 7-point scale and dichotomized as high (grades A, B, and C) versus low (grades D, E, and F). High school grades were used as the reference category.

Statistical analyses

The prevalence of mental health problems and bullying at school are presented using descriptive statistics, stratified by survey year (2014, 2018, 2020), gender, and school year (9 versus 11). As noted, we reduced the 18-item questionnaire assessing school function down to five essential factors by conducting a principal axis factor analysis (see Additional file 1 ). We then calculated the association between bullying at school (defined above) and mental health problems using multivariable logistic regression. Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (Cis). To assess the contribution of SES and school-related factors to this association, three models are presented: Crude, Model 1 adjusted for demographic factors: age, gender, and assessment year; Model 2 adjusted for Model 1 plus SES (parental education and student spending money), and Model 3 adjusted for Model 2 plus school-related factors (school grades and the five factors identified in the principal factor analysis). These covariates were entered into the regression models in three blocks, where the final model represents the fully adjusted analyses. In all models, the category ‘not bullied at school’ was used as the reference. Pseudo R-square was calculated to estimate what proportion of the variance in mental health problems was explained by each model. Unlike the R-square statistic derived from linear regression, the Pseudo R-square statistic derived from logistic regression gives an indicator of the explained variance, as opposed to an exact estimate, and is considered informative in identifying the relative contribution of each model to the outcome [ 20 ]. All analyses were performed using SPSS v. 26.0.

Prevalence of bullying at school and mental health problems

Estimates of the prevalence of bullying at school and mental health problems across the 12 strata of data (3 years × 2 school grades × 2 genders) are shown in Table 1 . The prevalence of bullying at school increased minimally (< 1%) between 2014 and 2020, except among girls in grade 11 (2.5% increase). Mental health problems increased between 2014 and 2020 (range = 1.2% [boys in year 11] to 4.6% [girls in year 11]); were three to four times more prevalent among girls (range = 11.6% to 17.2%) compared to boys (range = 2.6% to 4.9%); and were more prevalent among older adolescents compared to younger adolescents (range = 1% to 3.1% higher). Pooling all data, reports of mental health problems were four times more prevalent among boys who had been victims of bullying compared to those who reported no experiences with bullying. The corresponding figure for girls was two and a half times as prevalent.

Associations between bullying at school and mental health problems

Table 2 shows the association between bullying at school and mental health problems after adjustment for relevant covariates. Demographic factors, including female gender (OR = 3.87; CI 3.48–4.29), older age (OR = 1.38, CI 1.26–1.50), and more recent assessment year (OR = 1.18, CI 1.13–1.25) were associated with higher odds of mental health problems. In Model 2, none of the included SES variables (parental education and student spending money) were associated with mental health problems. In Model 3 (fully adjusted), the following school-related factors were associated with higher odds of mental health problems: lower grades in Swedish (OR = 1.42, CI 1.22–1.67); uninteresting or meaningless schoolwork (OR = 2.44, CI 2.13–2.78); feeling unwell at school (OR = 1.64, CI 1.34–1.85); unstructured school lessons (OR = 1.31, CI = 1.16–1.47); and no praise for achievements (OR = 1.19, CI 1.06–1.34). After adjustment for all covariates, being bullied at school remained associated with higher odds of mental health problems (OR = 2.57; CI 2.24–2.96). Demographic and school-related factors explained 12% and 6% of the variance in mental health problems, respectively (Pseudo R-Square). The inclusion of socioeconomic factors did not alter the variance explained.

Our findings indicate that mental health problems increased among Swedish adolescents between 2014 and 2020, while the prevalence of bullying at school remained stable (< 1% increase), except among girls in year 11, where the prevalence increased by 2.5%. As previously reported [ 5 , 6 ], mental health problems were more common among girls and older adolescents. These findings align with previous studies showing that adolescents who are bullied at school are more likely to experience mental health problems compared to those who are not bullied [ 3 , 4 , 9 ]. This detrimental relationship was observed after adjustment for school-related factors shown to be associated with adolescent mental health [ 10 ].

A novel finding was that boys who had been bullied at school reported a four-times higher prevalence of mental health problems compared to non-bullied boys. The corresponding figure for girls was 2.5 times higher for those who were bullied compared to non-bullied girls, which could indicate that boys are more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of bullying than girls. Alternatively, it may indicate that boys are (on average) bullied more frequently or more intensely than girls, leading to worse mental health. Social support could also play a role; adolescent girls often have stronger social networks than boys and could be more inclined to voice concerns about bullying to significant others, who in turn may offer supports which are protective [ 21 ]. Related studies partly confirm this speculative explanation. An Estonian study involving 2048 children and adolescents aged 10–16 years found that, compared to girls, boys who had been bullied were more likely to report severe distress, measured by poor mental health and feelings of hopelessness [ 22 ].

Other studies suggest that heritable traits, such as the tendency to internalize problems and having low self-esteem are associated with being a bully-victim [ 23 ]. Genetics are understood to explain a large proportion of bullying-related behaviors among adolescents. A study from the Netherlands involving 8215 primary school children found that genetics explained approximately 65% of the risk of being a bully-victim [ 24 ]. This proportion was similar for boys and girls. Higher than average body mass index (BMI) is another recognized risk factor [ 25 ]. A recent Australian trial involving 13 schools and 1087 students (mean age = 13 years) targeted adolescents with high-risk personality traits (hopelessness, anxiety sensitivity, impulsivity, sensation seeking) to reduce bullying at school; both as victims and perpetrators [ 26 ]. There was no significant intervention effect for bullying victimization or perpetration in the total sample. In a secondary analysis, compared to the control schools, intervention school students showed greater reductions in victimization, suicidal ideation, and emotional symptoms. These findings potentially support targeting high-risk personality traits in bullying prevention [ 26 ].

The relative stability of bullying at school between 2014 and 2020 suggests that other factors may better explain the increase in mental health problems seen here. Many factors could be contributing to these changes, including the increasingly competitive labour market, higher demands for education, and the rapid expansion of social media [ 19 , 27 , 28 ]. A recent Swedish study involving 29,199 students aged between 11 and 16 years found that the effects of school stress on psychosomatic symptoms have become stronger over time (1993–2017) and have increased more among girls than among boys [ 10 ]. Research is needed examining possible gender differences in perceived school stress and how these differences moderate associations between bullying and mental health.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the current study include the large participant sample from diverse schools; public and private, theoretical and practical orientations. The survey included items measuring diverse aspects of the school environment; factors previously linked to adolescent mental health but rarely included as covariates in studies of bullying and mental health. Some limitations are also acknowledged. These data are cross-sectional which means that the direction of the associations cannot be determined. Moreover, all the variables measured were self-reported. Previous studies indicate that students tend to under-report bullying and mental health problems [ 29 ]; thus, our results may underestimate the prevalence of these behaviors.

In conclusion, consistent with our stated hypotheses, we observed an increase in self-reported mental health problems among Swedish adolescents, and a detrimental association between bullying at school and mental health problems. Although bullying at school does not appear to be the primary explanation for these changes, bullying was detrimentally associated with mental health after adjustment for relevant demographic, socio-economic, and school-related factors, confirming our third hypothesis. The finding that boys are potentially more vulnerable than girls to the deleterious effects of bullying should be replicated in future studies, and the mechanisms investigated. Future studies should examine the longitudinal association between bullying and mental health, including which factors mediate/moderate this relationship. Epigenetic studies are also required to better understand the complex interaction between environmental and biological risk factors for adolescent mental health [ 24 ].

Availability of data and materials

Data requests will be considered on a case-by-case basis; please email the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Olweus D. School bullying: development and some important challenges. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9(9):751–80. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516 .

Article Google Scholar

Arseneault L, Bowes L, Shakoor S. Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: “Much ado about nothing”? Psychol Med. 2010;40(5):717–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709991383 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Arseneault L. The long-term impact of bullying victimization on mental health. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):27–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20399 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Moore SE, Norman RE, Suetani S, Thomas HJ, Sly PD, Scott JG. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7(1):60–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60 .

Hagquist C, Due P, Torsheim T, Valimaa R. Cross-country comparisons of trends in adolescent psychosomatic symptoms—a Rasch analysis of HBSC data from four Nordic countries. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1097-x .