Creating a new NHS England: Health Education England, NHS Digital and NHS England have merged. Learn more

More results...

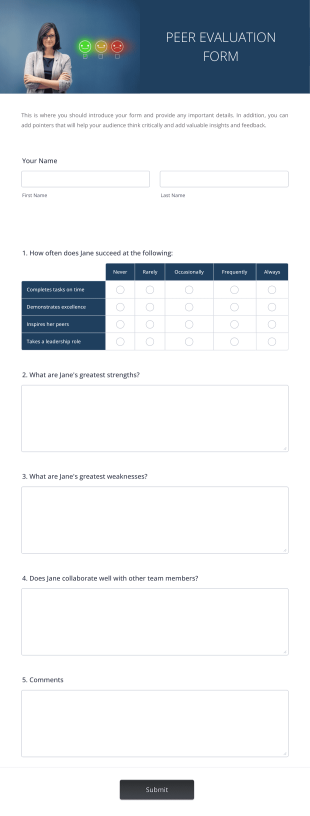

Workplace-based assessment feedback form

This document is the new, generic feedback form that should be used by assessors to provide feedback on Case-Based Discussions (CBDs), Observed Clinical Events (OCEs) and Direct Observations of Practical Skills (DOPS).

Document(s):

Workplace-based Assessment Feedback Form

Cookies on the nshcs website.

We've put some small files called cookies on your device to make our site work.

We'd like to set some additional cookies to understand how you use the website and to improve it.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

Let us know if this is OK. We'll use a cookie to save your choice. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

- I'm OK with analytics cookies

- Do not use analytics cookies

- Accessibility options:

Improving Care by Using Patient Feedback

Health and Social Care Services Research

doi: 10.3310/themedreview-04237

Both staff and patients want feedback from patients about the care to be heard and acted upon and the NHS has clear policies to encourage this. Doing this in practice is, however, complex and challenging. This report features nine new research studies about using patient experience data in the NHS. These show what organisations are doing now and what could be done better. Evidence ranges from hospital wards to general practice to mental health settings. There are also insights into new ways of mining and analyzing big data, using online feedback and approaches to involving patients in making sense of feedback and driving improvements.

Large amounts of patient feedback are currently collected in the NHS, particularly data from surveys and the NHS Friends and Family Test. Less attention is paid to other sources of patient feedback. A lot of resource and energy goes in to collecting feedback data but less into analysing it in ways that can lead to change or into sharing the feedback with staff who see patients on a day to day basis. Patients’ intentions in giving feedback are sometimes misunderstood. Many want to give praise and support staff and to have two way conversations about care, but the focus of healthcare providers can be on complaints and concerns, meaning they unwittingly disregard useful feedback.

There are many different reasons for looking at patient experience feedback data. Data is most often used for performance assessment and benchmarking in line with regulatory body requirements, making comparisons with other healthcare providers or to assess progress over time. Staff are sometimes unaware of the feedback, or when they are, they struggle to make sense of it in a way that can lead to improvements. They are not always aware of unsolicited feedback, such as that received online and when they are, they are often uncertain how to respond.

Staff need the time, skills and resources to make changes in practice. In many organisations, feedback about patient experience is managed in different departments from those that lead quality improvement. Whilst most organisations have a standardised method for quality improvement, there is less clarity and consistency in relation to using patient experience data.

Staff act on informal feedback in ways that are not always recognised as improvement. Where change does happen, it tends to be on transactional tasks rather than relationships and the way patients feel.

The research featured in this review shows that these challenges can be overcome and provides recommendations and links to practical resources for services and staff.

What can healthcare providers change as a result of these findings?

Organisations should embrace all forms of feedback (including complaints and unsolicited feedback) as an opportunity to review and improve care. While the monitoring of performance and compliance needs to conform to measures of reliability and validity, not all patient experience data needs to be numerical and representative – there can still be value in qualitative and unrepresentative intelligence to provide rich insights on specific issues and to highlight opportunities for improvement. Organisations sometimes try to triangulate different types of information into a single view, but it is important to respect different sources - sometimes the outliers are more useful data than the average. Organisations should also learn from positive as well as negative feedback.

Organisations should collect, collate and analyse feedback in ways that remain recognisable to the people who provide it whilst offering staff actionable findings. In many areas, including general practice, one of the major blocks to getting to grips with feedback is not having dedicated staff time allotted to it. Where there are dedicated staff leading patient experience, specialist training is likely to be needed, particularly in relation to improvement science. They also need to understand the strengths and weaknesses of different sources of feedback and be given the resources to use a broad range of collection systems.

The UK has led the world in the use of patient surveys, but staff are not always aware of them. Other forms of feedback including both structured and unstructured online feedback are emerging faster than the NHS’s ability to respond. Staff want to engage but need more understanding of, and confidence in, the use of different methods. As well as improving the transactional aspects of care (things like appointments and waiting times), organisations need to consider how data on relational experience (how the staff made them feel) is presented to staff. Summaries and infographics, together with patient stories, can motivate staff who interact with patients directly to explore aspects of the feedback about how staff made them feel. Patient experience data should be presented alongside safety and clinical effectiveness data and the associations between them made explicit.

Leaders need to ensure that staff have the authority and resources, together with the confidence and skill, to act on both formal and informal feedback. They may also need expert facilitation to help them decide what action to take in response to feedback and to integrate this with patient safety and effectiveness programmes. Engaging staff and patients in co design to analyse feedback is likely to result in sustainable improvements at a local level. A number of the featured studies have produced and tested toolkits that can assist with this. These can be found in the body of the review and in the study summaries.

The area of online feedback is a growing field, but staff are often uneasy and many organisations do not have systems and processes for responding to it. Organisations need to think about how they respond to unsolicited feedback, including complaints.

Looking to the future

Our review of the evidence on the use and usefulness of patient experience feedback shows that whilst there is a growing interest in using feedback for both accountability and service improvement, there are gaps in healthcare providers’ capacity to analyse and use it. These studies have added to our understanding of what helps and hinders staff and services to use patient experience feedback to drive improvement. But there are still areas where we do not know enough.

Further research is needed to determine methods of easily capturing patient experience that can meet multiple purposes, including performance monitoring and system redesign, and how to present this to staff in an easy to use way.

Understanding the patient experience is part of the wider evaluation of healthcare services and research is needed to consider how to integrate it with clinical outcomes and safety evaluations and with the ‘soft intelligence’ that staff and patients have about delivering and receiving care.

Research examining the ways in which patient safety, patient experience and clinical outcomes data overlap and interact in the everyday practices of hospital work (e.g. care on the wards, meetings, reports, etc.) would provide useful insights to inform improvement. More research is needed on how organisations and teams use different types of patient experience data for improving services and what support they need to do this well. Including how best to present the data to staff

Observational studies are needed that take a longitudinal perspective to understand how staff and organisations deal with patient feedback over time. These should consider comments on acute care as well as from people with chronic conditions. As we move into an era where services become more integrated it will become essential to view feedback across organisational boundaries.

Why we wrote this review

Research into patient experience feedback is relatively recent, gathering pace in the 1990s. Research into how healthcare providers then use this data to improve services is at an early stage. We wrote this review to bring together emergent themes and to provide practitioners, policy makers and the public with an overview of the findings of current NIHR funded research and to influence debate, policy and practice on the use of patient experience data.

Introduction to patient experience feedback

Healthcare is increasingly understood as an experience as well as an outcome. In addition, in a publicly funded service, patient experience feedback is a form of holding those services to account. The NHS Constitution for England enshrines the focus of patients’ experience in principle 4, which states that:

The patient will be at the heart of everything the NHS does. It should support individuals to promote and manage their own health. NHS services must reflect, and should be coordinated around and tailored to, the needs and preferences of patients, their families and their carers .

Evidence shows that patient experience feedback can shape services to better meet patient needs. We also know that better patient experience is associated with the efficient use of services. It results in the patient being better able to use the clinical advice given, and to use primary care more effectively. It has also been shown to affect hospital length of stay (Doyle et al 2013).

Good patient experience is therefore seen as a central outcome for the NHS, alongside clinical effectiveness and safety; however, people have different ideas about what constitutes patient experience and feedback is collected in different ways. Patients and healthcare providers do not come to this on an equal footing and the power to determine the question, the nature of the feedback, the interpretation and action remains largely with the professionals. The public inquiry into Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust showed that healthcare providers have some way to go in ensuring that patient experience becomes central to care management.

What feedback does the NHS collect?

Learning from what patients think about the care they have received is widely accepted as a key to improving healthcare services. However, collecting actionable data across the breadth of patient experience and making change based on it remains a challenge.

The NHS excels in collecting certain kinds of patient experience data, with the national in-patient survey in England being one of the first of its kind in the world when introduced in 2001. The Friends and Family Test (FFT) is a further mandatory method of data collection used in the NHS in England (see box X). Scotland introduced a national survey in 2010, Wales in 2013 and Northern Ireland in 2014. Robert and Cornwell (2013) reported that the first similar international public reporting was in 2008 in the USA. Australia, Canada, New Zealand and most European countries have not developed measures of patients’ experience at national level. It is less clear how the national survey has triggered improvement.

Feedback is also collected through complaint systems but Liu et al (2019) found that an emphasis on ‘putting out fires’ may detract from using the feedback within them to improve care for future patients.

Other types of feedback are collected in the NHS in more ad hoc ways, including online feedback such as Care Opinion and the former website, NHS Choices. It is also collected through local unit level surveys, patient forums, informal feedback to Patient Advice and Liaison Services, and quality improvement projects. Data is collected in a variety of ways with local organisations using different methods, from feedback kiosks to narratives and patient stories.

There has been widespread acceptance that good patient experience is an important outcome of care in its own right… patient experience is a domain of quality that is distinct from, but complementary to, the quality of clinical care. Although an increasing number of surveys have been developed to measure patient experience, there has been equally widespread acceptance that these measures have not been very effective at actually improving care. Study H

Research featured in this review

What do we mean by patient experience data.

We define patient experience data in this review as what individuals say about the care they have received. This is different from patients evaluating their care and treatment, such as through patient reported outcome data. Patient experience is wider than the data collected about it and this review focuses on documented forms of experience feedback, including unsolicited feedback. We acknowledge that this does not fully represent patient experience nor all the ways it is provided or the ways in which it influences change.

Studies we have included

This review focuses on research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), which has made a substantial investment in new research in this area. In 2014 the NIHR called for research on the use and usefulness of patient experience data. Eight large, multi-method bids were successful, seven of which have been published in 2019 or will be published early in 2020. Prior to this, two other large studies looking at patient experience data were funded. Together these studies cover a range of care settings including general practice and mental health, although most are set in acute hospitals These nine studies form the core of this themed review. We do not consider them individually in the main text but use them to illustrate our main themes and we refer to them as studies A-I (listed below). For more details about how they were undertaken and some of their key findings, please see the study summaries and references to full text reports.

The featured studies found some remarkably consistent themes. While we have used particular studies to illustrate each theme, this does not mean other studies didn’t find similar things.

In addition to the main nine studies, we also mention some other important evidence funded by NIHR and some research funded by other bodies, to add context and supporting information, and these are referenced in.

Featured studies in this review

A - Sheard, L. Using patient experience data to develop a patient experience toolkit to improve hospital care: a mixed-methods study (published October 2019 ) B - Weich, S. Evaluating the Use of Patient Experience Data to Improve the Quality of Inpatient Mental Health Care (estimated publication March 2020) C - Donetto, S. Organisational strategies and practices to improve care using patient experience data in acute NHS hospital trusts: an ethnographic study (published October 2019) D - Locock, L. Understanding how frontline staff use patient experience data for service improvement – an exploratory case study evaluation (published June2019) E - Powell, J. Using online patient feedback to improve NHS services: the INQUIRE multimethod study (published October 2019) F - Sanders, M. Enhancing the credibility, usefulness and relevance of patient experience data in services for people with long-term physical and mental health conditions using digital data capture and improved analysis of narrative data (estimated publication January 2020) G - Rivas, C. PRESENT: Patient Reported Experience Survey Engineering of Natural Text: developing practical automated analysis and dashboard representations of cancer survey free text answers (published July 2019) H - Burt, J. Improving patient experience in primary care: a multimethod programme of research on the measurement and improvement of patient experience (published May 2017) I - Graham, C. An evaluation of a near real-time survey for improving patients’ experiences of the relational aspects of care: a mixed-methods evaluation (published March 2018) A summary of these studies is included in the Summaries Studies section at the end of this review.

This review seeks to explore the complexity and ambiguities around understanding and learning from patient experience. We also offer some solutions and recommendations. We hope that by shining a light on the tensions and assumptions uncovered in the featured studies, the review will help to start conversations between different parts of the system and with users of healthcare services. We anticipate that the audience will be broad, including policy makers, healthcare provider boards (including Non-Executive directors and governors), clinical staff as well as service users and the public at large.

A few words on research methods

Patient experience is highly personal and not all aspects of experience lend themselves to quantitative measurement. This makes research into patient experience complex.

The most common methods in this review were surveys, case studies, action research and improvement science approaches. Our featured studies contain a mixture of these methods, and each method has to be judged separately on its own merits rather than applying a universal set of criteria to all.

- Surveys obtain structured information although they can provide opportunity for free text comments

- Case studies provide rich contextual data that can enable deeper understanding of how things work. They rely on multiple sources of evidence and often use mixed methods. This might include routine data collected from local sites combined with observation methods – researchers spending time shadowing staff and services – and interviews or focus groups around practices, process and relationships.

- Action research involves researchers working alongside staff and patients to plan and study change as it happens. The researcher is involved in constant assessment and redesign of a process as it moves toward a desired outcome.

- Improvement science approaches explore how successful strategies to improve healthcare service are, and why.

Structure of this review

In this review, we ask three key questions about collecting and using patient experience feedback; why, what and how? before considering how healthcare service providers make sense of and act on the feedback. We then reflect on the gaps in our knowledge and offer some immediate and longer term recommendations.

Why should people share their experience?

Different approaches to collecting patient experience feedback to some extent reflect underlying assumptions about why we might be interested in it and therefore how we respond to it. For some healthcare staff and policy makers, feedback helps to assess service performance against expectations. For others its primary purpose is to understand and respect individual experiences and for others to improve services.

Table: Different purposes of patient experience feedback data for healthcare organisations of practitioners

For performance or comparison

The distinction between different purposes directs the type of information collected, the way it is analysed and how it is subsequently used. Where the focus is on performance or comparisons, quantitative data such as that obtained from surveys are the most common method and patients largely report their experience against a pre-determined set of criteria. Individual responses to core questions are aggregated into a score for the organisation or the individual member of staff. Surveys often attempt to address wider issues by including free text boxes that allow people to discuss what is important to them. We discuss some of the challenges around analysing free text data later in this review.

For sharing with other patients and public

For patients and the public, there may also be other purposes. For example, to share with other potential service users. Ziebland et al (2016) reviewed the literature and identified that hearing about other people’s experiences of a health condition could influence a person’s own health through seven domains: finding information, feeling supported, maintaining relationships, using health services, changing behaviours, learning to tell the story and visualising illness. Study E found that some people see giving feedback as a form of public accountability for the service and part of a sense of ‘caring for care’ (although it is not always used as such by the healthcare providers). There can be tension between these purposes, and sometimes the intended purpose of the person giving the feedback is not matched by its use by care providers. Study F found that the purpose of providing feedback was not clear to most patients. The lack of organisational response to their survey feedback meant they perceived it as a ‘tick box exercise’ and they thought that their comments would not be used.

Study D notes that although survey data are collected from patients, they are not usually involved in analysing it nor deciding how to act on it.

Patients' understanding of the purpose of feedback

A number of studies found that patients value giving feedback as ‘conversations’, using their own words to focus on the aspects of care important to them rather than what is important to the organisation. Most importantly they want a response so that feedback can be a two way street. This can be a powerful way of understanding the difference between an ideal service imagined by planners and the lived experience of how the service works in practice. Patient stories often identify parts of the process that have previously been overlooked, or the impact of local context on how services are experienced.

Patients felt that their feedback could serve different purposes. Study E found that patients distinguish between generalised feedback that is intended for other patients, carers and their families and feedback that is raising a specific concern to the service provider. When providing online feedback for other patients, people said the fact that feedback is public and anonymised data is key. This sort of feedback was seen by patients as a way of publicly thanking staff, boosting morale, encouraging best practice and providing other patients with a positive signal about good care. Significantly, they reported that they saw their feedback as something staff might use to promote and maintain the service at times of increased financial pressure and cuts. This sort of feedback was shared over social media, especially health forums and Facebook. Twitter, and to a lesser extent blogs, were often used to communicate with healthcare professionals and service providers, including policy-makers and opinion leaders, while at the same time being accessible to the wider public. Patients said that concerns and complaints about their care require focused feedback and they use different online routes for this, such as local websites (these differed depending on the Trust and/or service in question) or third party platforms such as Care Opinion or iWantGreatCare.

Frontline staff perception of the purpose

The central collection of some types of feedback means that hospital staff are often unaware that the data was even being collected. Study B found that patient experience data were often viewed (particularly by frontline staff) as necessary only for regulatory compliance. Concerns about ‘reliability’ meant that vulnerable people, such as those with acute mental health problems, were sometimes excluded from giving the formal feedback that feeds into compliance and assurance programmes.

Matching purpose and interpretation

Understanding the purpose of feedback is critical not only to decisions about how to collect it but also to interpreting it. Study H notes a mismatch between what patients say about their experience in response to survey questionnaires and what they say at interview and Gallan et. al. (2017) report a difference between survey scores and free text. It is not possible, or even helpful, to triangulate patient experience data from different sources down to a single ‘truth’. Instead, comparing different sources elicits common themes and provides a rounded picture. Study G found that negative comments can be sandwiched between positive comments and vice versa and that staff felt it was important to consider this context rather than separate out the positive from the negative

What sort of feedback?

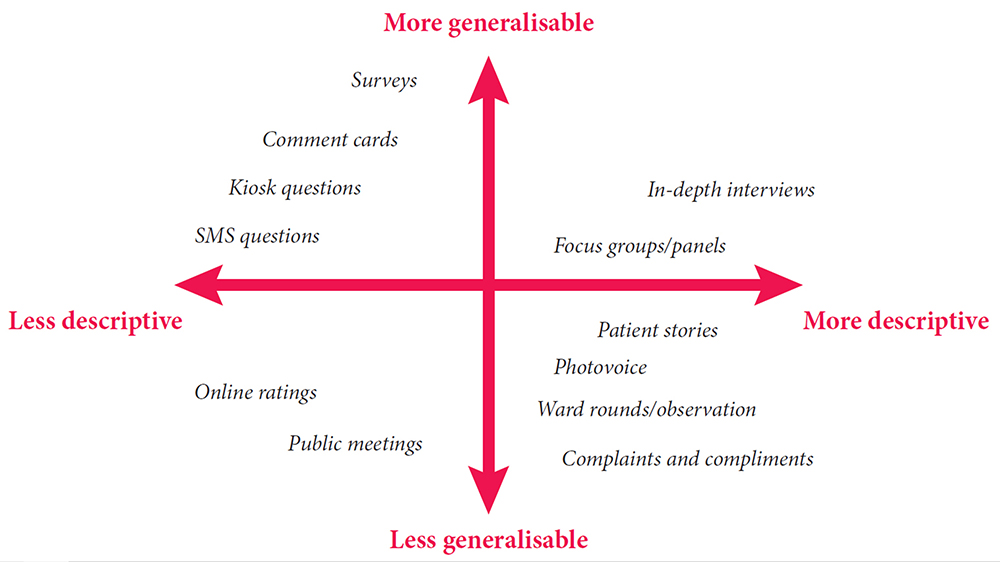

Patient experience is multi-dimensional. On one hand, it can be the ‘transactional’ experience of the process, e.g. waiting times, information provided and the immediate outcomes. On the other hand, it can be how people feel about interactions with healthcare staff and whether people felt treated with dignity and respect. Different types of information are needed to explore different aspects of experience. Whilst many surveys ask about relational as well as transactional experience, other methods, such as patient narratives might provide richer information. This difference is reflected in Study A’s observation that there are at least thirty eight different types of data collection on patient experience. Healthcare providers don’t always know how to make the best of this diverse range of data, or of the myriad of unsolicited feedback. This can leave both the public and healthcare providers confused and uncertain about how best to collect patient experience and also how to act on it.

Image taken from Measuring Patient Experience, by the Health Foundation

Who gives the feedback?

Study D asks whether data have to come directly from patients to ‘count’ as patient experience data. This raises the question of whether families and friends, who often have a ringside seat to the care, might be legitimate sources of patient experience feedback. Study D also found staff feedback and observations of their patients’ experience as well as their own experience had potential as a source of improvement ideas and motivation to achieve change care.

Credibility of the data

Some healthcare staff feel more comfortable with feedback that meets traditional measures of objectivity and are sceptical about the methods by which patient experience data is collected. Study H reported that general medical practitioners express strong personal commitments to incorporating patient feedback in quality improvement efforts. At the same time, they express strong negative views about the credibility of survey findings and patients’ motivations and competence in providing feedback, leading on balance to negative engagements with patient feedback.

Despite Trusts routinely collecting patient experience data, this data is often felt to be of limited value, because of methodological problems (including poor or unknown psychometric properties or missing data) or because the measures used lack granular detail necessary to produce meaningful action plans to address concerns raised. Study B

The suggestion that patient experience does not need to be representative of the whole population or collected in a standardised way has led some to question the quasi-research use of the term ‘data’, with its assumptions about which data are acceptable.

Objectivity or richness?

In contrast to objective data, Martin et al (2015) discuss the importance of ‘soft’ intelligence: the informal data that is hard to classify and quantify but which can provide holistic understanding and form the basis for local interventions. This applies well to patient experience and Locock et. al. (2014), in another NIHR-funded study, discuss the use of narratives as a powerful way of understanding human experience. Bate and Robert (2007) note that narratives are not intended to be objective or verifiable but celebrate the uniquely human and subjective recalled experience or set of experiences. One form of narrative based approach to service improvement is experience based co-design.

Experience-Based Co-Design (EBCD)

EBCD involves gathering experiences from patients and staff through in-depth interviewing, observations and group discussions, identifying key ‘touch points’ (emotionally significant points) and assigning positive or negative feelings. A short edited film is created from the patient interviews. This is shown to staff and patients, conveying in an impactful way how patients experience the service. Staff and patients are then brought together to explore the findings and to work in small groups to identify and implement activities that will improve the service or the care pathway. Accelerated EBCD, which replaces the individual videos with existing videos from an archive has been found to generate a similar response.

The Point of Care Foundation has a toolkit which includes short videos from staff and patients involved in experience-based co-design (EBCD) projects.

How is feedback on patient experience collected and used?

Currently the NHS expends a lot of energy on collecting data with less attention paid to whether this provides the information necessary to act. Study B’s economic modelling revealed that the costs of collecting patient feedback (i.e. staff time) far outweighed efforts to use the findings to drive improvement in practice at present. This may go some way to explaining DeCourcy et al (2012) findings that results of the national NHS patient survey in England have been remarkably stable over time, with the only significant improvements seen in areas where there have been coordinated government-led campaigns, targets and incentives. Study G found that staff consider presentation of the data to be important. They want to be able to navigate it in ways that answer questions specific to their service or to particular patients

Study C found variations in how data are generated and processed at different Trusts and describe the differences in how Friends and Family Test data are collected. The 2015 guidance from NHS England states that ‘Patients should have the opportunity to provide their feedback via the FFT on the day of discharge, or within 48 hours after discharge’. However, discharge is a complex process and ward managers and matrons frequently said that this was an inappropriate point at which to ask patients for feedback.

The Friends and Family Test

Launched in April 2013, the Friends and Family Test (FFT) has been rolled out in phases to most NHS funded services in England. FFT asks people if they would recommend the services they have used and offers supplementary follow-up questions. A review of the test and the way it is used has led to revised guidance for implementing the new FFT from 1 April 2020.

The changes announced already mean that:

- There will be a new FFT mandatory question and six new response options

- Mandatory timescales where some services are currently required to seek feedback from users within a specific period will be removed to allow more local flexibility and enable people to give feedback at any time, in line with other services

- There will be greater emphasis on use of the FFT feedback to drive improvement

- New, more flexible, arrangements for ambulance services where the FFT has proved difficult to implement in practice

Hearing stories (not just counting them)

Entwistle et al (2012) have argued that existing health care quality frameworks do not cover all aspects that patients want to feedback and that procedure-driven, standardised approaches such as surveys and checklists are too narrow. For many of the public, patient experience feedback is about being heard as a unique individual and not just as part of a group. This requires their experience to be considered as a whole, rather than reduced to a series of categories. Patient stories are also powerful ways of connecting with healthcare staff, however they are often seen as too informal to be considered as legitimate data.

Study A suggests that hearing stories means more than simply collecting patient stories but also including the patient voice in interpreting feedback. Shifting away from the idea of patient feedback as objective before and after measures for improvement, the authors used participative techniques including critical, collective reflection to consider what changes should take place. The researchers suggest that this approach has similarities with the principles of experience based co-design and other participatory improvement frameworks and that is an area that is ripe for further exploration.

Asking about patient experience can appear straightforward, however Study B observed that the quality of relationships between staff and patients affects the nature of feedback patients or carers give to staff. In their study of people in mental health units, patients or carers would only offer feedback selectively and only about particular issues at the end of their stay if they had experience good relationships with staff during the admission.

Positive experience feedback

Many patients provide feedback about good experience, but staff don’t always recognise and value it. Study A observed that most wards had plenty of generic positive feedback. However, this feedback is not probed and therefore specific elements of positive practice that should be illuminated and encouraged are rarely identified. Study G found that positive feedback tends to be shorter; often a single word like ‘fantastic’. There is a danger of giving less weight to this type of feedback. Study B described how patients in mental health settings spent time thinking about the way to frame and phrase praise, however, positive feedback was often treated in an (unintentionally) dismissive way by staff.

Learning from positive experience feedback

Vanessa Sweeney, Deputy Chief Nurse and Head of Nursing – Surgery and Cancer Board at University College London Hospitals NHS FT decided to share an example of positive feedback from a patient with staff. The impact on the staff was immediate and Vanessa decided to share their reaction with the patient who provided the feedback. The letter she sent, and the patient’s response are reproduced here:

Dear XXXXX,

Thank you for your kind and thoughtful letter, it has been shared widely with the teams and the named individuals and has had such a positive impact.

I’m the head of nursing for the Surgery and Cancer Board and the wards and departments where you received care. I’m also one of the four deputy chief nurses for UCLH and one of my responsibilities is to lead the trust-wide Sisters Forum. It is attended by more than 40 senior nurses and midwives every month who lead wards and departments across our various sites. Last week I took your letter to this forum and shared it with the sisters and charge nurses. I removed your name but kept the details about the staff. I read your letter verbatim and then gave the sisters and charge nurses the opportunity in groups to discuss in more detail. I asked them to think about the words you used, the impact of care, their reflections and how it will influence their practice. Your letter had a very powerful impact on us as a group and really made us think about how we pay attention to compliments but especially the detail of your experience and what really matters. I should also share that this large room of ward sisters were so moved by your kindness, compassion and thoughtfulness for others.

We are now making this a regular feature of our Trust Sisters Forum and will be introducing this to the Matrons Forum – sharing a compliment letter and paying attention to the narrative, what matters most to a person.

Thank you again for taking the time to write this letter and by doing so, having such a wide lasting impact on the teams, individuals and now senior nurses from across UCLH. We have taken a lot from it and will have a lasting impact on the care we give.

The patient replied: Thank you so much for your email and feedback. As a family we were truly moved on hearing what impact the compliment has had. My son said – “really uplifting”. I would just like to add that if you ever need any input from a user of your services please do not hesitate to contact me again.

Informal feedback

Study F describes how staff recognised that sometimes experience is shared naturally in day to day discussions with service users but does not get formally captured. Staff expressed a wish for more opportunities to capture verbal feedback, especially in mental health services. Study D found that staff do use informal feedback and patient stories to inform quality improvements at ward level, but this was not considered as ‘data’. This made the patient contribution invisible and staff could not always reference where the intelligence informing a proposed change came from.

So, the ‘big ticket’ items like clinical outcomes, Never Events, tend to be subject to QI [Quality Improvement] methodology. Patient experience on the other hand tends to get addressed through ‘actions’, which isn’t necessarily a formal method as such and not in line with QI methodology. So, for instance, you get a set of complaints or comments about a particular thing on a ward. They act to change it, that’s an action. They just change that. It’s not formal and it’s not following a method. That’s not to say it’s not a quality improvement, because it is: the action was based on feedback and it’s led to a change. But it is informal as opposed to formal. It’s because we don’t know how to deal with the feedback that is informal. Study C

Online feedback

A new and developing area of patient experience feedback is through digital platforms. UK and US data show that online feedback about healthcare is increasing and likely to continue to grow fast but this presents its own specific challenges to healthcare providers.

Who writes and reads it?

Study E surveyed 1824 internet users. 42% of people surveyed read online patient experience feedback, even though only 8% write it. Younger people and with higher incomes are more likely to read feedback, particularly women, and they were more likely to be experiencing a health challenge, live in urban areas and be frequent internet users.

What are they writing/reading?

The majority of online reviews are positive and numeric ratings for healthcare providers tend to be high. Members of the public who had left or read on line feedback framed it as a means of improving healthcare services, supporting staff and other patients and described it as ‘caring for care’ to be supportive and help the NHS to learn. Respondents said they would like more of a ‘conversation’ although in practice they often struggled to do this. In contrast to the positive intent expressed by the public, many healthcare professionals are cautious about online feedback, believing it to be mainly critical and unrepresentative, and rarely encourage it. This reflects a lack of value given to different types of feedback data. In Study E , medical staff were more likely than nurses to believe online feedback is unrepresentative and generally negative in tone with primary care professionals being more cautious than their secondary care counterparts.

Healthcare providers' response to online feedback

Baines et. al. (2018) found that adult mental health patients leaving feedback in an online environment expected a response within seven days, but healthcare professionals are unsure of how to respond to online feedback. Ramsey et al (2019) report five response types to online feedback: non-responses, generic responses, appreciative responses, offline responses and transparent, conversational responses. The different response types reflect the organisational approach to patient experience data, which in itself may reflect deeper cultures. As yet unpublished work by Gillespie (2019) suggests that there is an association between defensiveness in staff responses to online feedback and the summary hospital mortality indicator. This suggests that staff responses to online feedback might reveal a broader hospital culture which blocks critical, but potentially important, information moving from patients to staff.

The idea of a digitally sophisticated health consumer at the centre of a technology-enabled health system, actively engaged in managing their own care, which elsewhere we have characterised as the “digital health citizen”, has caught the imagination of policy makers seeking to address the challenges of twenty-first century health care. At the same time…providing online feedback is a minority activity, there is professional scepticism and a lack of organisational preparedness. Study E

Study E notes that a vast amount of feedback left online is largely unseen by Trusts, either because they are not looking in those places, or because they do not think of those avenues as legitimate feedback channels. Organisations often state that they can only respond to individual, named cases. In general, only sanctioned channels get monitored and responded to with feedback from other channels ignored. Staff are often unsure where the responsibility to respond to online feedback lies or feel powerless to do so as anonymous comments are perceived to restrict what response can be made. The authors recommend the NHS must improve the culture around receiving unsolicited feedback and consider their response-ability (their ability to respond specifically to online feedback), as well as their responsivity (ensuring responses are timely, as well as visible).

Organisational attitudes to online feedback influence the ways in which individual staff respond. Study D suggests that staff find unstructured and unsolicited online feedback interesting and potentially useful but they do not feel it has organisational endorsement and so it is rarely used proactively. Study E reports that a quarter of nurses and over half of doctors surveyed said they had never yet changed practices as a result of online feedback.

Who, where and when?

Feedback on general practice care.

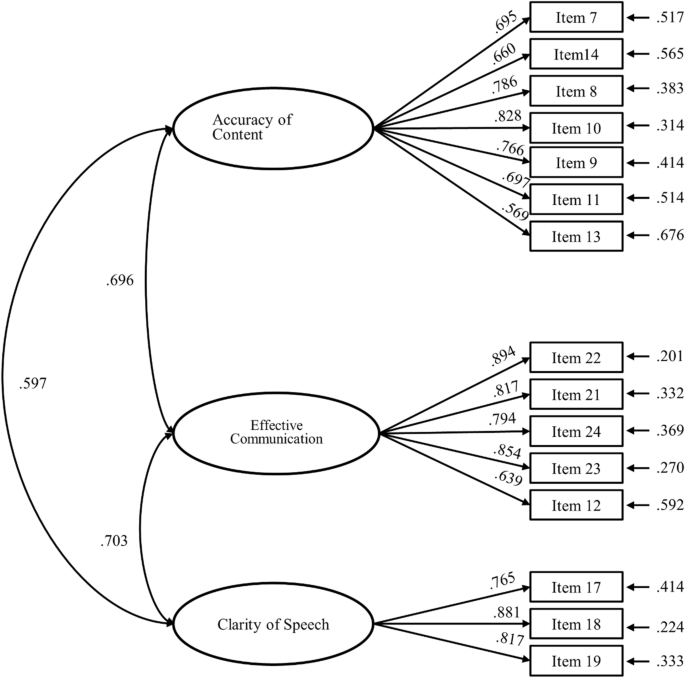

Much of the research into using patient feedback has been on inpatient, acute hospital care. However, Study H looked at how people using primary care services provide feedback through patient surveys and how the staff in GP practices used the findings. The study was particularly interested in practices with low scores on the GP Patient Survey and whether patient feedback reflected actual GP behaviours. The findings were similar to studies in hospitals. GP practice staff neither believed nor trusted patient surveys and expressed concerns about their validity and reliability and the likely representativeness of respondents. They were also more comfortable with addressing transactional experience such as appointment systems and telephone answering. Addressing relational aspects, such as an individual doctor’s communication skills was seen to be much more difficult.

The researchers videoed a number of patient/GP consultations and then asked the patients to complete a questionnaire about the GP’s communication. The researchers interviewed a sample of these patients, showing them the video and asked them to reflect on how they completed the questionnaire. The patients readily criticised the care verbally when reviewing the videos and acknowledged that they had been reluctant to be critical when completing the questionnaire because of the need to maintain a relationship with the GP but also because they were grateful for NHS care that they had received in the past. Patients rating of the videos were similar to those of trained raters when communication was good. But when the raters judged communication in a consultation to be poor, patients’ assessments were highly variable from ‘poor’ to ‘very good’. The authors concluded that patient reluctance to give negative feedback on surveys means that when scores for a GP are lower than those in comparable practices, there is likely to be a significant concern.

Although the GP Patient Survey is available in 15 languages, fewer than 0.2% of surveys are completed in languages other than English and feedback from people who have minority ethnicity backgrounds tends to be low. Study H explored the feedback of patients from South Asian backgrounds. These respondents tend to be registered in practices with generally low scores, explaining about half of the difference between South Asian and white British patients in their experience of care. In fact, when people from both white and South Asian backgrounds were shown videos of simulated consultations with GPs, people with South Asian backgrounds gave scores that were much higher when adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics than white respondents. This suggests that low patient experience scores from South Asian communities reflect care that isworse than for their white counterparts.

Feedback from vulnerable people

Healthcare staff often express concerns about asking vulnerable people and those who have had a traumatic experience to give feedback but are reluctant to accept anonymised feedback. Speed et al (2016) describe this as the anonymity paradox where some patients feel anonymity is a prerequisite for effective use of feedback processes in order to ensure future care is not compromised but professionals see it as a major barrier as they are concerned about reputational damage if they cannot fact check the account.

Study B studied patient experience feedback in mental health settings. Some staff felt that inpatient settings were an inappropriate place to obtain feedback or that the feedback would be unhelpful. This was partly because staff recognised they felt they did not have enough time to spend with people who were very unwell and to make sense of their feedback. However, there was also a belief in some units that the feedback from those who were acutely unwell (especially if psychotic) was not reliable. The researchers found that people in mental health settings are able to provide feedback about their experiences even when unwell, but detailed and specific feedback was only available near to or after discharge. Some patients were wary of giving formal feedback before discharge for fear of the consequences, an anxiety shared by carers. However, patients wanted their feedback gathered informally at different points during their stay, including their day to day experience, irrespective of wellness. The researchers also found that where patients were not listened to in the early part of their admission, they were less likely to provide feedback when asked at the end of their stay.

Feedback from people with long term conditions

Study F explored patient experience data in services for people with long-term musculo- skeletal conditions and people with mental health conditions across inpatient, outpatient and general practice settings. Patients felt that there should be more opportunities to capture verbal feedback, especially in mental health services. Gaining feedback required considerable sensitivity given the complexity that some people live with. People with mental health problems often said they would be unlikely to use digital methods to give feedback, especially when unwell, when they might feel unable to write and would prefer to give verbal feedback. Some older respondents with experience of musculoskeletal conditions expressed a concern that some people with painful or swollen hands or mobility restrictions may find feedback kiosks difficult to use. The study also highlighted the issues for people for whom English is not a first language.

When to give feedback

The use of feedback relates to the timing of both its collection and reporting. There can be a tension between the different needs of people providing feedback and of those acting on it. Patients often value the anonymity and reflection space of giving feedback after the care episode has been completed, however Study A reported that staff want real time feedback rather than the delayed feedback from surveys that can be months old. In contrast, Study I notes the concerns of some that near real time feedback surveys have potential for sampling bias from staff, who select which patients are most suitable to provide feedback. However, Davies et al (2008) argue that the aims of real-time data collection are not about representative samples but to feed data back quickly to staff so that the necessary changes can be identified and acted on. Study I explored the use of real-time patient experience data collection on older people’s wards and in A&E departments and found that it was associated with a small but statistically significant improvement (p = 0.044) in measured relational aspects of care over the course of the study.

Ensuring patient feedback is collected from a diverse range of people and places, and at different points in their journey, is important and the evidence suggests that it will require multiple routes, tailored to the specific circumstances of different groups of service users and different settings. What do healthcare providers do with patient experience feedback?

Numerous studies point to an appetite amongst healthcare staff for ‘credible’ feedback. However, despite the rhetoric and good intentions, healthcare providers appear to struggle to use patient experience data to change practice. Study B’s national survey found few English Mental Health NHS Trusts were able to describe how patient experience data were analysed and used to drive service improvements or change. Only 27% of Trusts were able to collect, analyse and use patient experience data to support change. 51% of Trusts were collecting feedback but they were experiencing difficulty in using it to create change, whilst 22% were struggling to collect patient experience feedback routinely. The researchers report it was clear that data analysis was the weakest point in the cycle. Study D found only half of Trusts responding to their survey had a specific plan/strategy for the collection and use of patient experience data, although 60% said their quality improvement (QI) strategy included how they would use patient experience data.

Study B produced a short video explaining their research :

How does the data get analysed?

Understanding the feedback depends on how it is analysed and by whom. It is rare that patients are invited to participate or to confirm the analysis. Data for performance assessment is reduced to categories and stripped of its context. Whilst many healthcare staff express a wish to have an overview or average figure, evidence shows that there is a tendency for more people who are either very pleased or very unhappy to response. This means that there is a U shape distribution of responses and using averages can therefore be misleading. This is echoed in aggregated organisational scores, which can mask significant variation between different teams and units.

Data collection and analysis of surveys is often outsourced and individual organisations may not receive support to make sense of survey findings and to translate that into improvement actions (Flott et al 2016).

Study D found that staff look at multiple feedback sources plus their own ideas of what needs to change, using a sense-making process akin to ‘clinical mind lines’ as described by Gabbay and Le May (2004), where understanding is informed by a combination of evidence and experience, resulting in socially constructed “knowledge in practice”.

Despite the desire for patients to tell their stories in their own words, the challenge of managing and integrating large volumes of free text feedback prevents its widespread use. Two of the NIHR studies featured in this review sought to address this by developing automated tools to analyse free text feedback. Study F and Study G both applied data mining techniques to free-text comments to identify themes and associated sentiments (positive, negative, or neutral) although they used slightly different techniques to do so. In Study F the text mining around sentiment compared well against those produced by qualitative researchers working on the same datasets in both general hospital and mental health facilities, although for some themes, e.g. care quality, the qualitative researchers appeared to provide a higher number of positive sentiments than the text mining. The researchers produced an electronic tool that allowed the rapid automated processing of free-text comments to give an overview of comments for particular themes whilst still providing an opportunity to drill down into specific or unusual comments for further manual analysis to gain additional insight. The study highlighted the challenges of dealing with informal and complex language that frequently appears in patient feedback. This meant that many comments are automatically excluded from analysis by the text mining computer programmes. Whilst text mining can provide useful analysis for reporting on large datasets and within large organisation: qualitative analysis may be more useful for small datasets or small teams.

Managing big data

Large amount of free text data on patient experience are collected in surveys. There comes a point where it is impossible to manage and analyse this data manually. Using automated qualitative analysis techniques, whilst still allowing drill down to individual feedback is a promising approach to enabling these data to be used.

Study G sought to involve patients and carers as well as NHS staff and the third sector (the stakeholders) in the development of their approach. The aim was to the use of patient experience free text comments in the National Cancer Patient Experience Survey. They developed a toolkit to process raw survey free text data and to sort it into themes; quantitative summaries of the themes were provided in graphs, with local, regional and national benchmarks. The rule based data mining approach used was 86% accurate when compared with a human coder. Data could be sorted and filter in bespoke ways then drilled down to the original comments. Dta was also sorted by sentiment and the weighting to positive or negative shown on a graphic for staff to see at a glance which areas might need improving and which could be highlighted to boost staff morale. The software was designed specifically for the Cancer Experience survey, but the researchers believe it will be possible to develop the software to be as accurate on other clinical aspects of care.

How does the data get used?

Study C set out to describe the journey from data to impact but found that ‘journey’ was not a useful way of looking at what happened to the data and the processing did not follow a linear path. They found that the transformation of the data to action is partly dependent on whether the process is independent from other concerns and whether the people involved have the authority to act in a meaningful way. For example, Clinical Nurse Specialists in cancer care have a formal responsibility for patient experience and have the authority to act on data in ways that clearly lead to improvements in care. Similarly, organisationally recognised and validated mechanisms such as ward accreditation schemes are seen as producing recognised data which can lead directly to change. Where there is no recognised system or person to act, change can falter.

Clinical staff are busy and need information in quick access presentations. Study I and Study G found that the response of patient facing staff to formal feedback (e.g. surveys) was influenced by the format of the feedback: accessible reporting such as infographics were particularly helpful Study A found senior ward staff were often sent spreadsheets of unfiltered and unanalysed feedback, but a lack of skills meant they could not interrogate it. This was compounded by a lack of time as staffing calculations did not factor in any time for reflecting and acting on patient feedback. Short summaries (e.g. dashboards and graphs) were essential tools to help staff understand areas for improvements quickly.

Who uses patient experience data?

Patient experience data is most widely used to assess performance. Study A observed that formal sources of patient feedback (such as surveys or the Friends and Family Test) are used by hospital management for assurance and benchmarking purposes. Study C noted that patient feedback in national surveys is frequently presented at the corporate level rather than at individual unit level which hinders local ownership. It is rarely linked to other indicators of quality (such as safety and clinical effectiveness) and this is compounded by the delay between data collection and receiving the reports. They also identified a frequent disconnect between the data generation and management work carried out by Patient Experience teams and the action for care improvement resulting from that data, which is more often the responsibility of nursing teams.

What gets improved?

There is a potential tension between quick wins and more complex improvement. Study A reported that ward teams want to get information from patients about things that can be quickly fixed, but they also want to understand how their patients feel so they can develop more appropriate ways of relating to them. This is reflected in the observations by many studies that actions taken in response to feedback are largely to improve transactional experience. Study B contrasts ‘environmental’ change (changes that related to the physical environment or tangibles like diet, seating areas in wards, temperature control and the physical environment of the ward) with ‘cultural’ change (changes related to relationships with patients including feelings of respect and dignity and staff attitudes). This resonates with Gleeson et al.’s (2016) systematic review which found that patient experience data were largely used to identify small areas of incremental change to services that do not require a change to staff behaviour.

The Yorkshire Patient Experience Toolkit (PET), developed by Study A , helps frontline staff to make changes based on patient experience feedback.

Are service providers ready for patient feedback?

Gkeredakis et al (2011) point out that simply presenting NHS staff with raw data will not lead to change. An organisation’s capacity to collect and act on patient experience is related to its systems and processes and the way staff work. Study A for example, found it was difficult to establish multi-disciplinary involvement in patient experience initiatives unless teams already work in this way. Study A referred to an earlier study (Sheard et al, 2017) to help explain some of the challenges observed. Two conditions need to be in place for effective use of patient experience feedback. Firstly, staff need to believe that listening to patients is worthwhile and secondly, they need organisational permission and resources to make changes. Staff in most (but not all) wards they studied believed patient experience feedback was worthwhile but did not have the resources to act. Even where staff expressed strong belief in the importance of listening to patient feedback, they did not always have confidence in their ability or freedom to make change. Study A sought to address some of these barriers as they arose through its action research approach but found them to be persistent and hard to shift. In addition to organisational and resource issues, Study A also revealed that staff found responding to patient experience emotionally difficult and needed sensitive support to respond constructively.

Study I found buy-in from senior staff was a key factor in both the collection and use of the feedback. For example, directors of nursing or ward leaders revisiting action plans during regularly scheduled meetings and progress monitoring.

Patient Experience and Quality Improvement

Whilst patient experience is often talked about as one of the cornerstones of quality, patient experience feedback was seen by a number of researchers to have an ambiguous relationship with quality improvement systems. Study C noted that informal feedback gets acted on, but the improvements are also seen as informal and not captured. This illustrates a theme running through many of the featured studies that patient experience data is seen as separate from other quality processes and that it is often collected and considered outside organisational quality improvement structures.

…patient experience is almost [our emphasis] an indicator of something but it’s not used as a direct measure in any improvement project […] I like things in black and white, I don’t like things that are grey. Patient experience is grey. (Head of Quality Improvement). Study C

Lee et al (2017) studied how two NHS Trust boards used patient experience feedback. They found that although patient survey findings were presented to the boards, they were not used as a form of quality assurance. The discussion of surveys and other kinds of feedback did not of itself lead to action or explicit assurance, and external pressures were equally important in determining whether and how boards use feedback.

Study A found that Quality Improvement teams were rarely involved in managing and acting on patient experience feedback, or if they were, they focused on strategy at an organisational level rather than practice change at local level. Study D observed that in most organisations ‘experience’ and ‘complaints’ are dealt with separately, by different teams with different levels of authority. There was a strong feeling that there needs to be a formal process for managing experience data with sufficient resources to ensure specific action can be taken.

The Point of Care Foundation website hosts a guide developed as part of Study D . It provides a guide for clinical, patient experience and quality teams to draw on patient experience data to improve quality in healthcare and covers gathering data, getting started and improvement methods.

Study C observed complex relationships between institutionally recognised quality improvement efforts (formal QI) and the vast amount of unsystematised improvement work that takes place in response to patient experience data in less well-documented ways (everyday QI). They found that when frontline staff (often nurses) had the right skills, they were able to use imperfect data, set it into context and search for further data to fill the gaps and use it to improve services.

Study C created a video explaining what they found about how staff can use patient experience feedback to improve care.

NHS Improvement Patient Experience Improvement Framework

The framework was developed to help NHS organisations to achieve good and outstanding ratings in their Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspections. The framework enables organisations to carry out an organisational diagnostic to establish how far patient experience is embedded in its leadership, culture and operational processes. It is divided into six sections, each sub-divided and listing the characteristics and processes of organisations that are effective in continuously improving the experience of patients. The framework integrates policy guidance with the most frequent reasons CQC gives for rating acute trusts ‘outstanding’.

Conclusions

Our review of the evidence shows that there is much work in NHS organisations exploring how to collect and use data about patient experience. This complements the ‘soft intelligence’ acquired through experience and informal inquiry by staff and patients. However, we found that this work can be disjointed and stand alone from other quality improvement work and the management of complaints.

The research we feature highlights that patients are often motivated to give praise, or to be constructively critical and suggest improvements and wanting to help the NHS. NHS England has developed a programme to pilot and test Always Events, those aspects of the patient and family experience that should always occur when patients interact with healthcare professionals and the health care delivery system. However, the research features here suggest a managerial focus on ‘bad’ experiences and therefore the rich information about what goes right and what can be learnt from this can be overlooked. Positive feedback often comes from unsolicited feedback and the NHS needs to think about how to use this well.

Our featured studies show that staff need time and skills to collect, consider and act on patient feedback, and that patients often want to be actively involved in all stages.

The NHS has made important strides towards partnering with patients to improve services and the research featured in this review can help direct the next steps.

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Elaine Maxwell with Tara Lamont of the NIHR Dissemination Centre.

We acknowledge the input of the following experts who formed our Steering Group:

Jocelyn Cornwell - CEO, Point of Care Foundation Dr Sara Donetto - Lecturer, King's College London Chris Graham - CEO, Picker Institute Julia Holding - Head of Patient Experience, NHS Improvement Professor Louise Locock - Professor in Health Service Research, University of Aberdeen Dr Claire Marsh - Senior Research Fellow/Patient and Public Engagement Lead - Bradford Institute for Health Research David McNally - Head of Experience of Care, NHS England James Munro - Chief Executive, Care Opinion Laurie Olivia - Head of Public Engagement and Involvement, NIHR Clinical Research Network Professor John Powell - Associate Professor, University of Oxford Professor Glenn Robert - Professor, King's College London Neil Tester - Director, Richmond Group Professor Scott Weich - Professor of Mental Health - University of Sheffield

We are also grateful to the following staff in NHS organisations who reviewed the final draft:

Melanie Gager - Nurse Consultant in Critical Care Royal Berkshire NHS FT Lara Harwood - Service Experience Lead, Hertfordshire Partnership NHS FT Lisa Anderton - Head of Patient Experience, University College London Hospitals NHS FT

Study summaries

Study a - u sing patient experience data to develop a patient experience toolkit to improve hospital care: a mixed-methods study .

Principal investigator Lawton, R. (Sheard et al, 2019)

This study aimed to understand and enhance how hospital staff learn from and act on patient experience feedback. A scoping review, qualitative exploratory interviews and focus groups with 50 NHS staff found use of patient feedback is hindered at both micro and macro levels. These findings fed into a co-design process with staff and patients to produce a Patient Experience Tool that could overcome these challenges. The tool was trialled, tested and refined in six wards across three NHS Trusts (chosen to reflect diversity in size and patient population) over a 12 month period using an action research methodology. Its critical components were open-ended conversational interviews with patients by volunteers to elicit key topics of importance, facilitated team discussions around these topics, and coached quality improvement cycles to enact changes. A large, mixed methods evaluation was conducted over the same 12 month period to understand what aspects of the toolkit worked or did not work, how and why, with a view to highlighting critical success factors. Ethnographic observations of key meetings were collected, together with in depth interviews at the half way and end point with key stakeholders and detailed reflective diaries kept by the action researchers. Ritchie and Spencer’s Framework approach was used to analyse these data. A 12 item patient experience survey was completed by around 15 - 20 patients per week in total (across the six wards) beginning four weeks before the action research formally started and ending four weeks after it formally ceased.

Sheard L, Marsh C, Mills T, Peacock R, Langley J, Partridge R, et al. Using patient experience data to develop a patient experience toolkit to improve hospital care: a mixed-methods study. Health Serv Deliv Res 2019;7(36)

Sheard L, Peacock R, Marsh C, Lawton L. (2019). What’s the problem with patient experience feedback? A macro and micro understanding, based on findings from a three site UK quality study . Health Expectations, 22 (1) 46-53

Study B - Evaluating the Use of Patient Experience Data to Improve the Quality of Inpatient Mental Health Care (EURIPDIES)

Principal investigator Weich, S. (2020)

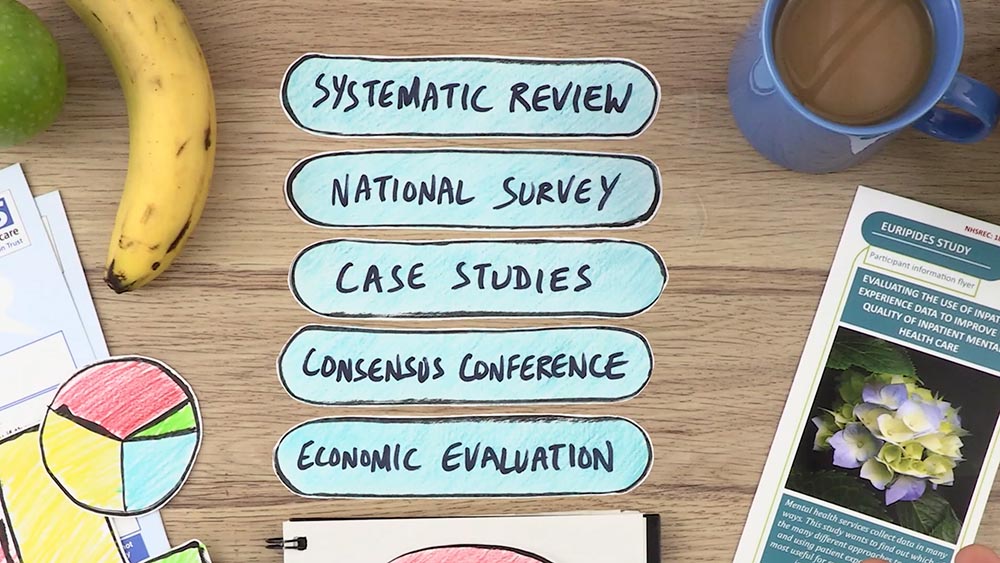

This study looked at the way patient experience data are collected and used in inpatient mental health services. Using a realist research design it had five work packages; (1) a systematic review of 116 papers to identify patient experience themes relevant to inpatient mental health care, (2) a national survey of patient experience leads in inpatient mental health Trusts in England, (3) six in-depth case studies of what works, for whom, in what circumstances and why, including which types of patient experience measures and organisational processes facilitate effective translation of these data into service improvement actions, (4) a consensus conference with forty four participants to agree recommendations about best practice in the collection and use of mental health inpatient experience data and (5) health economic modelling to estimate resource requirements and barriers to adoption of best practice.

Patient experience work was well regarded but vulnerable to cost improvement pressure and only 27% of Trusts were able to collect and analyse patient experience data to support change. Few trusts had robust or extensive processes for analysing data in any detail and there was little evidence that patient feedback led to service change. A key finding was that patients can provide feedback about their experiences even when unwell and there is a loss of trust when staff are unwilling to listen at these times. The researchers described a set of conditions necessary for effective collection and use of data from the program theories tested in the case studies. These were refined by the consensus conference and provide a series of recommendations to support people at the most vulnerable point in their mental health care.

The researchers have produced a video of their findings.

Study C - Organisational strategies and practices to improve care using patient experience data in acute NHS hospital trusts: an ethnographic study

Principal investigator Donetto, S. (2019)

The main aim of this study was to explore the strategies and practices organisations use to collect and interpret patient experience data and to translate the findings into quality improvements in five purposively sampled acute NHS hospital trusts in England. A secondary aim was to understand and optimise the involvement and responsibilities of nurses in senior managerial and frontline roles with respect to such data. An ethnographic study of the ‘journeys’ of patient experience data, in cancer and dementia services in particular, guided by Actor-Network Theory, was undertaken. This was followed by workshops (one cross-site, and one at each Trust) bringing together different stakeholders (members of staff, national policymakers, patient/carer representatives) considering how to use patient experience data. The researchers observed that each type of data takes multiple forms and can generate improvements in care at different stages in its complex ‘journey’ through an organisation. Some improvements are part of formal quality improvement systems, but many are informal and therefore not identified as quality improvement. Action is dependent on the context of the patient experience data collection and on people or systems interacting with the data having the autonomy and authority to act. The responsibility for acting on patient experience data falls largely on nurses, but other professionals also have important roles. The researchers found that sense-making exercises to understand and reflect on the findings can support organisational learning. The authors conclude that it is not sufficient to focus solely on improving the quantity and quality of data NHS Trusts collect. Attention should also be paid , to how these data are made meaningful to staff and ensuring systems are in place that enable these data to trigger action for improvement.

Donetto S, Desai A, Zoccatelli G, Robert G, Allen D, Brearley S & Rafferty AM (2019) Organisational strategies and practices to improve care using patient experience data in acute NHS hospital trusts: an ethnographic study . Health Serv Deliv Res;7(34)

Study D - Un derstanding how frontline staff use patient experience data for service improvement - an exploratory case study evaluation and national survey (US-PEx)

Principal Investigator Locock L (2019)

This mixed methods study used national staff survey results and a new national survey of patient experience leads together with case study research in six carefully selected hospital medical wards to explore what action staff took in relation to particular quality improvement projects prompted by concerns raised by patient experience data. The effects of the projects were measured by surveys of experience of medical patients before and after the changes and observation on the wards.

Over a third of patient experience leads responded to the survey and they reported the biggest barrier to making good use of patient experience data was lack of time. Responses to the before and after patient surveys were received from about a third of patients in total, although this varied between sites (1134 total survey responses before, 1318 after) and these showed little significant change in patient experience ratings following quality improvement projects. Insights from observations and interviews showed that staff were often unsure about how to use patient experience data. Ward-specific feedback, as generated for this study, appeared helpful. Staff drew on a range of informal and formal sources of intelligence about patient experience, not all of which they recognized as ‘data’. This included their own informal observations of care and conversations with patients and families. Some focused on improving staff experience as a route to improving patient experience. Research showed that teams with people from different backgrounds, including a mix of disciplines and NHS Band levels, brought a wider range of perspectives, organisational networks and resources (‘team capital’). This meant the they were more likely to be able to make changes on the ground and therefore be more likely to be successful in improving care.

Insights from this study were used to develop an online guide to using patient experience data for improvement.

Study E - Online pat ient feedback: a multimethod study to understand how to Improve NHS Quality Using Internet Ratings and Experiences (INQUIRE)

Principal investigator powell, j. (2019).

This study explored what patients feed back online, how the public and healthcare professionals in the United Kingdom feel about it and how it can be used by the NHS to improve the quality of services. It comprised five work programmes, starting with a scoping review on what was already known. A questionnaire survey of the public was used to find out who reads and write online feedback are, and the reasons they choose to comment on health services in this way. 8% had written and 42% had read online health care feedback in the last year. This was followed up by face to face interviews with patients about their experiences of giving feedback to the NHS. A further questionnaire explored the views and experiences of doctors and nurses. Finally, the researchers spent time in four NHS trusts to learn more about the approaches that NHS organisations take to receiving and dealing with online feedback from patients. A key finding was that people who leave feedback online are motivated primarily to improve healthcare services and they want their feedback to form part of a conversation. However, many professionals are cautious about online patient feedback and rarely encourage it. Doctors were more likely than nurses to believe online feedback is unrepresentative and generally negative in tone. NHS trusts do not monitor all feedback routes and staff are often unsure where the responsibility to respond lies. It is important that NHS staff have the ability to respond and can do so in a timely and visible way.

Study F - Developing and Enhancing the Usefulness of Patient Experience Data using digital methods in services for long term conditions (the DEPEND mixed methods study). Understanding and enhancing how hospital staff learn from and act on patient experience feedback.

Principal investigator Sanders, C. (2020)