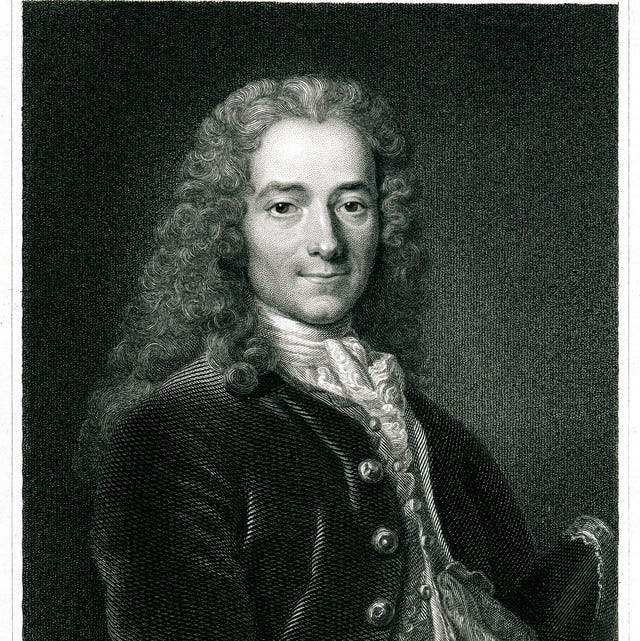

Author of the satirical novella 'Candide,' Voltaire is widely considered one of France's greatest Enlightenment writers.

(1694-1778)

Who Was Voltaire?

Voltaire established himself as one of the leading writers of the Enlightenment. His famed works include the tragic play Zaïre , the historical study The Age of Louis XIV and the satirical novella Candide . Often at odds with French authorities over his politically and religiously charged works, he was twice imprisoned and spent many years in exile. He died shortly after returning to Paris in 1778.

Voltaire was born François-Marie Arouet to a prosperous family on November 21, 1694, in Paris, France. He was the youngest of five children born to François Arouet and Marie Marguerite d'Aumart. When Voltaire was just seven years old, his mother passed away. Following her death, he grew closer to his free-thinking godfather.

In 1704, Voltaire was enrolled at the Collége Louis-le-Grand, a Jesuit secondary school in Paris, where he received a classical education and began showing promise as a writer.

Beliefs and Philosophy

Voltaire, in keeping with other Enlightenment thinkers of the era, was a deist — not by faith, according to him, but rather by reason. He looked favorably on religious tolerance, even though he could be severely critical towards Christianity, Judaism and Islam.

As a vegetarian and an advocate of animal rights, however, Voltaire praised Hinduism, stating Hindus were "[a] peaceful and innocent people, equally incapable of hurting others or of defending themselves."

Major Works

Voltaire wrote poetry and plays, as well as historical and philosophical works. His most well-known poetry includes The Henriade (1723) and The Maid of Orleans , which he started writing in 1730 but never fully completed.

Among the earliest of Voltaire's best-known plays is his adaptation of Sophocles' tragedy Oedipus , which was first performed in 1718. Voltaire followed with a string of dramatic tragedies, including Mariamne (1724). His Zaïre (1732), written in verse, was something of a departure from previous works: Until that point, Voltaire's tragedies had centered on a fatal flaw in the protagonist's character; however, the tragedy in Zaïre was the result of circumstance. Following Zaïre, Voltaire continued to write tragic plays, including Mahomet (1736) and Nanine (1749).

Voltaire's body of writing also includes the notable historical works The Age of Louis XIV (1751) and Essay on the Customs and the Spirit of the Nations (1756). In the latter, Voltaire took a unique approach to tracing the progression of world civilization by focusing on social history and the arts.

Voltaire's popular philosophic works took the form of the short stories Micromégas (1752) and Plato's Dream (1756), as well as the famed satirical novella Candide (1759), which is considered Voltaire's greatest work. Candide is filled with philosophical and religious parody, and in the end the characters reject optimism. There is great debate on whether Voltaire was making an actual statement about embracing a pessimistic philosophy or if he was trying to encourage people to be actively involved to improve society.

In 1764, he published another of his acclaimed philosophical works, Dictionnaire philosophique , an encyclopedic dictionary that embraced the concepts of Enlightenment and rejected the ideas of the Roman Catholic Church.

Arrests and Exiles

In 1716, Voltaire was exiled to Tulle for mocking the duc d'Orleans. In 1717, he returned to Paris, only to be arrested and exiled to the Bastille for a year on charges of writing libelous poetry. Voltaire was sent to the Bastille again in 1726, for arguing with the Chevalier de Rohan. This time he was only detained briefly before being exiled to England, where he remained for nearly three years.

The publication of Voltaire's Letters on the English (1733) angered the French church and government, forcing the writer to flee to safer pastures. He spent the next 15 years with his mistress, Émilie du Châtelet, at her husband's home in Cirey-sur-Blaise.

Voltaire moved to Prussia in 1750 as a member of Frederick the Great's court, and spent later years in Geneva and Ferney. By 1778, he was recognized as an icon of the Enlightenment's progressive ideals, and he was given a hero's welcome upon his return to Paris. He died there shortly afterward, on May 30, 1778.

In 1952, researcher and writer Theodore Besterman established a museum devoted to Voltaire in Geneva. He later set about writing a biography of his favorite subject, and following his death in 1976, the Voltaire Foundation was vested permanently at the University of Oxford.

The foundation continued to work toward making the Enlightenment writer's prolific output available to the public. It was later announced that The Oxford Complete Works of Voltaire , the first exhaustive annotated edition of Voltaire’s novels, plays and letters, would expand to 220 volumes by 2020.

In November 2017, during an event to celebrate what would have been Voltaire's 323rd birthday, foundation director Nicholas Cronk explained how the famed writer used inaccuracies to generate attention. Among his fabrications, Voltaire offered up differing dates for his birthday and lied about the identity of his biological father.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Voltaire

- Birth Year: 1694

- Birth date: November 21, 1694

- Birth City: Paris

- Birth Country: France

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Author of the satirical novella 'Candide,' Voltaire is widely considered one of France's greatest Enlightenment writers.

- Writing and Publishing

- Astrological Sign: Scorpio

- Collége Louis-le-Grand

- Nationalities

- Occupations

- Death Year: 1778

- Death date: May 30, 1778

- Death City: Paris

- Death Country: France

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- A witty saying proves nothing.

- All murderers are punished unless they kill in large numbers and to the sound of trumpets.

Philosophers

Francis Bacon

Auguste Comte

Charles-Louis de Secondat

Saint Thomas Aquinas

William James

John Stuart Mill

Jean-Paul Sartre

Immanuel Kant

Biography Online

Voltaire Biography

“Love truth, but pardon error.”

– Voltaire

Voltaire was a prolific writer, producing more than 20,000 letters and over 2,000 books and pamphlets. Despite strict censorship laws, he frequently risked large penalties by breaking them and questioning the establishment.

Short Biography of Voltaire

Voltaire was born François-Marie Arouet, in Paris. He was educated by Jesuits at the Collège Louis-le-Grand (1704–1711), becoming fluent in Greek, Latin and the major European languages.

His father tried to encourage Voltaire to become a lawyer, but Voltaire was more interested in becoming a writer. Instead of studying to be a lawyer, he began writing poetry and mild criticisms of the church and state. His humorous, satirical writing made him popular with sections of Paris society, though they also started attracting the attention of the censors.

In 1726, he was exiled to England after being involved in a scuffle with a French nobleman. The nobleman used his wealth to have him arrested, and this would cause Voltaire to try and reform the French judicial system. After this first imprisonment in the Bastilles, he changed his name to Voltaire – signifying his departure from his past. He also used numerous other pen names throughout the course of his life, in a bid to escape censorship.

Voltaire spent three years in England, where he was influenced by British writers, such as William Shakespeare and also the different political system, which saw a constitutional monarchy rather than an absolute monarchy as in France. He also learnt from great scientists, such as Sir Isaac Newton . Voltaire was particularly impressed by the Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, such as Adam Smith and David Hume, saying once:

“We look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilisation”

Although he had much in common with fellow French Enlightenment philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau , the pair often disagreed and had a prickly relationship. However, after Rousseau wrote Emile / Vicaire Savoyard, Voltaire offered Rousseau a safe haven because he appreciated Rousseau’s attack on religious hypocrisy. Rousseau regretted not replying to Voltaire’s offer.

On returning to France, he wrote letters praising the British system of government and their greater respect for freedom of speech. This enraged the French establishment, and again he was forced to flee Paris.

Seeking a safe place, Voltaire began a collaboration with Marquise du Chatelet. During this time, Voltaire wrote on Newton’s scientific theories and helped to make Newton’s ideas accessible to a much wider section of European society. He also began attacking the church’s relationship with the state. Voltaire argued for the separation of religion and state and also allowing freedom of belief and religious tolerance. Voltaire had a mixed opinion of the Bible and was willing to criticise it. Though not professing a religion, he believed in God, as a matter of reason.

“What is faith? Is it to believe that which is evident? No. It is perfectly evident to my mind that there exists a necessary, eternal, supreme, and intelligent being. This is no matter of faith, but of reason.” On Catholicism

In a letter to Frederick II, King of Prussia, (5 January 1767) he once wrote:

“Ours [religion] is without a doubt the most ridiculous, the most absurd, and the most blood-thirsty ever to infect the world.”

In 1744, Voltaire returned to Paris, where he began a relationship with his niece, Marie Louise Mignot. They remained together until his death.

For a brief time, he was invited by Frederick the Great, to Potsdam. Here, Voltaire wrote more articles of a scientific nature, but later incurred the displeasure of the king as he started satirising the abuses of power within the state.

In 1759, he wrote his best-known work – Candide, ou l’Optimisme ( Candide , or Optimism ) This was a satire on the philosophy of Leibniz. After a brief stay in Geneva, he settled for 20 years in Ferny on the French border.

In his later life, Voltaire continued to write and also to support persecuted religious minorities. He was visited by some of the leading European intellectuals of the day – such as James Boswell and Adam Smith.

In 1778, he died after shortly returning to Paris. Some of his enemies claimed he made a deathbed conversion to Catholicism, but this is disputed.

In February of that year, fearing he would die, he wrote:

“I die adoring God, loving my friends, not hating my enemies, and detesting superstition.”

Voltaire was secretly buried before a pronouncement could be made public.

Three years after his death, on 11 July 1791, he was brought back to Paris to be enshrined in the Pantheon. It is said up to a million people came to see Voltaire – now considered a French hero and fore-runner of the French revolution.

Influence of Voltaire

- Voltaire revolutionised the art of history. He sought to avoid bias and included discussion of social and economic issues, moving away from dry military accounts.

- Voltaire argued for an extension of education, hoping greater literacy would free society from ignorance.

- Voltaire wrote poems and plays, including two epics. Voltaire politicised writing by showing that even poetry and romance could be laced with satire and political polemic. Often it was indirect criticism that was most effective.

- Voltaire was a passionate and persistent critic of those in power who misused their position. By attacking the abuses of the absolute monarchy and church, he paved the way for a less deferential attitude which was a significant underlying cause of the French revolution.

- At a time of religious persecution, Voltaire illustrated how religious dogmas were created by human ignorance and led to needless bloodshed and suffering.

- Voltaire was a key figure of the enlightenment which sought to use a range of scientific and literary books to explain the underlying nature of life. Voltaire believed no one book or dogma could explain everything. But, true understanding required the use of reason and an open mind.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan. “ Biography of Voltaire” , Oxford, www.biographyonline.net – 3 February 2013. Last updated 7 February 2018.

Voltaire Quotes

“It does not require great art, or magnificently trained eloquence, to prove that Christians should tolerate each other. I, however, am going further: I say that we should regard all men as our brothers. What? The Turk my brother? The Chinaman my brother? The Jew? The Siam? Yes, without doubt; are we not all children of the same father and creatures of the same God?”

– Voltaire A Treatise on Toleration (1763)

Candide – Voltaire

Candide – Voltaire at Amazon

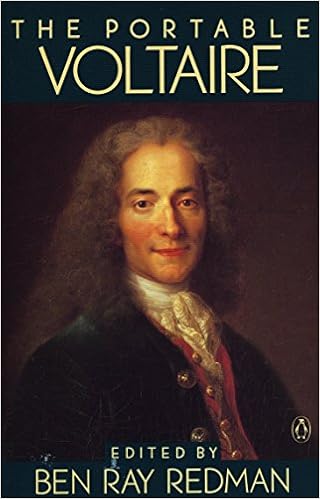

The Portable Voltaire

The Portable Voltaire at Amazon

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

François-Marie d’Arouet (1694–1778), better known by his pen name Voltaire, was a French writer and public activist who played a singular role in defining the eighteenth-century movement called the Enlightenment. At the center of his work was a new conception of philosophy and the philosopher that in several crucial respects influenced the modern concept of each. Yet in other ways Voltaire was not a philosopher at all in the modern sense of the term. He wrote as many plays, stories, and poems as patently philosophical tracts, and he in fact directed many of his critical writings against the philosophical pretensions of recognized philosophers such as Leibniz, Malebranche, and Descartes. He was, however, a vigorous defender of a conception of natural science that served in his mind as the antidote to vain and fruitless philosophical investigation. In clarifying this new distinction between science and philosophy, and especially in fighting vigorously for it in public campaigns directed against the perceived enemies of fanaticism and superstition, Voltaire pointed modern philosophy down several paths that it subsequently followed.

To capture Voltaire’s unconventional place in the history of philosophy, this article will be structured in a particular way. First, a full account of Voltaire’s life is offered, not merely as background context for his philosophical work, but as an argument about the way that his particular career produced his particular contributions to European philosophy. Second, a survey of Voltaire’s philosophical views is offered so as to attach the legacy of what Voltaire did with the intellectual viewpoints that his activities reinforced.

1.1 Voltaire’s Early Years (1694–1726)

1.2 the english period (1726–1729), 1.3 becoming a philosophe, 1.4 the newton wars (1732–1745), 1.5 from french newtonian to enlightenment philosophe (1745–1755), 1.6 fighting for philosophie (1755–1778), 1.7 voltaire, philosophe icon of enlightenment philosophie (1778–present), 2.1 liberty, 2.2 hedonism, 2.3 skepticism, 2.4 newtonian empirical science, 2.5 toward science without metaphysics, primary literature, primary literature in translation, secondary literature, other internet resources, related entries, 1. voltaire’s life: the philosopher as critic and public activist.

Voltaire only began to identify himself with philosophy and the philosophe identity during middle age. His work Lettres philosophiques , published in 1734 when he was forty years old, was the key turning point in this transformation. Before this date, Voltaire’s life in no way pointed him toward the philosophical destiny that he was later to assume. His early orientation toward literature and libertine sociability, however, shaped his philosophical identity in crucial ways.

François-Marie d’Arouet was born in 1694, the fourth of five children, to a well-to-do public official and his well bred aristocratic wife. In its fusion of traditional French aristocratic pedigree with the new wealth and power of royal bureaucratic administration, the d’Arouet family was representative of elite society in France during the reign of Louis XIV. The young François-Marie acquired from his parents the benefits of prosperity and political favor, and from the Jesuits at the prestigious Collège Louis-le-Grand in Paris he also acquired a first-class education. François-Marie also acquired an introduction to modern letters from his father who was active in the literary culture of the period both in Paris and at the royal court of Versailles. François senior appears to have enjoyed the company of men of letters, yet his frustration with his son’s ambition to become a writer is notorious. From early in his youth, Voltaire aspired to emulate his idols Molière, Racine, and Corneille and become a playwright, yet Voltaire’s father strenuously opposed the idea, hoping to install his son instead in a position of public authority. First as a law student, then as a lawyer’s apprentice, and finally as a secretary to a French diplomat, Voltaire attempted to fulfill his father’s wishes. But in each case, he ended up abandoning his posts, sometimes amidst scandal.

Escaping from the burdens of these public obligations, Voltaire would retreat into the libertine sociability of Paris. It was here in the 1720s, during the culturally vibrant period of the Regency government between the reigns of Louis XIV and XV (1715–1723), that Voltaire established one dimension of his identity. His wit and congeniality were legendary even as a youth, so he had few difficulties establishing himself as a popular figure in Regency literary circles. He also learned how to play the patronage game so important to those with writerly ambitions. Thanks, therefore, to some artfully composed writings, a couple of well-made contacts, more than a few bon mots , and a little successful investing, especially during John Law’s Mississippi Bubble fiasco, Voltaire was able to establish himself as an independent man of letters in Paris. His literary debut occurred in 1718 with the publication of his Oedipe , a reworking of the ancient tragedy that evoked the French classicism of Racine and Corneille. The play was first performed at the home of the Duchesse du Maine at Sceaux, a sign of Voltaire’s quick ascent to the very pinnacle of elite literary society. Its published title page also announced the new pen name that Voltaire would ever after deploy.

During the Regency, Voltaire circulated widely in elite circles such as those that congregated at Sceaux, but he also cultivated more illicit and libertine sociability as well. This pairing was not at all uncommon during this time, and Voltaire’s intellectual work in the 1720s—a mix of poems and plays that shifted between playful libertinism and serious classicism seemingly without pause—illustrated perfectly the values of pleasure, honnêteté , and good taste that were the watchwords of this cultural milieu. Philosophy was also a part of this mix, and during the Regency the young Voltaire was especially shaped by his contacts with the English aristocrat, freethinker,and Jacobite Lord Bolingbroke. Bolingbroke lived in exile in France during the Regency period, and Voltaire was a frequent visitor to La Source, the Englishman’s estate near Orléans. The chateau served as a reunion point for a wide range of intellectuals, and many believe that Voltaire was first introduced to natural philosophy generally, and to the work of Locke and the English Newtonians specifically, at Bolingbroke’s estate. It was certainly true that these ideas, especially in their more deistic and libertine configurations, were at the heart of Bolingbroke’s identity.

Yet even if Voltaire was introduced to English philosophy in this way, its influence on his thought was most shaped by his brief exile in England between 1726–29. The occasion for his departure was an affair of honor. A very powerful aristocrat, the Duc de Rohan, accused Voltaire of defamation, and in the face of this charge the untitled writer chose to save face and avoid more serious prosecution by leaving the country indefinitely. In the spring of 1726, therefore, Voltaire left Paris for England.

It was during his English period that Voltaire’s transition into his mature philosophe identity began. Bolingbroke, whose address Voltaire left in Paris as his own forwarding address, was one conduit of influence. In particular, Voltaire met through Bolingbroke Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope, and John Gay, writers who were at that moment beginning to experiment with the use of literary forms such as the novel and theater in the creation of a new kind of critical public politics. Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels , which appeared only months before Voltaire’s arrival, is the most famous exemplar of this new fusion of writing with political criticism. Later the same year Bolingbroke also brought out the first issue of the Craftsman , a political journal that served as the public platform for his circle’s Tory opposition to the Whig oligarchy in England. The Craftsman helped to create English political journalism in the grand style, and for the next three years Voltaire moved in Bolingbroke’s circle, absorbing the culture and sharing in the public political contestation that was percolating all around him.

Voltaire did not restrict himself to Bolingbroke’s circle alone, however. After Bolingbroke, his primary contact in England was a merchant by the name of Everard Fawkener. Fawkener introduced Voltaire to a side of London life entirely different from that offered by Bolingbroke’s circle of Tory intellectuals. This included the Whig circles that Bolingbroke’s group opposed. It also included figures such as Samuel Clarke and other self-proclaimed Newtonians. Voltaire did not meet Newton himself before Sir Isaac’s death in March, 1727, but he did meet his sister—learning from her the famous myth of Newton’s apple, which Voltaire would play a major role in making famous. Voltaire also came to know the other Newtonians in Clarke’s circle, and since he became proficient enough with English to write letters and even fiction in the language, it is very likely that he immersed himself in their writings as well. Voltaire also visited Holland during these years, forming important contacts with Dutch journalists and publishers and meeting Willem’s Gravesande and other Dutch Newtonian savants. Given his other activities, it is also likely that Voltaire frequented the coffeehouses of London even if no firm evidence survives confirming that he did. It would not be surprising, therefore, to learn that Voltaire attended the Newtonian public lectures of John Theophilus Desaguliers or those of one of his rivals. Whatever the precise conduits, all of his encounters in England made Voltaire into a very knowledgeable student of English natural philosophy.

When French officials granted Voltaire permission to re-enter Paris in 1729, he was devoid of pensions and banned from the royal court at Versailles. But he was also a different kind of writer and thinker. It is no doubt overly grandiose to say with Lord Morley that, “Voltaire left France a poet and returned to it a sage.” It is also an exaggeration to say that he was transformed from a poet into a philosophe while in England. For one, these two sides of Voltaire’s intellectual identity were forever intertwined, and he never experienced an absolute transformation from one into the other at any point in his life. But the English years did trigger a transformation in him.

After his return to France, Voltaire worked hard to restore his sources of financial and political support. The financial problems were the easiest to solve. In 1729, the French government staged a sort of lottery to help amortize some of the royal debt. A friend perceived an opportunity for investors in the structure of the government’s offering, and at a dinner attended by Voltaire he formed a society to purchase shares. Voltaire participated, and in the fall of that year when the returns were posted he had made a fortune. Voltaire’s inheritance from his father also became available to him at the same time, and from this date forward Voltaire never again struggled financially. This result was no insignificant development since Voltaire’s financial independence effectively freed him from one dimension of the patronage system so necessary to aspiring writers and intellectuals in the period. In particular, while other writers were required to appeal to powerful financial patrons in order to secure the livelihood that made possible their intellectual careers, Voltaire was never again beholden to these imperatives.

The patronage structures of Old Regime France provided more than economic support to writers, however, and restoring the crédit upon which his reputation as a writer and thinker depended was far less simple. Gradually, however, through a combination of artfully written plays, poems, and essays and careful self-presentation in Parisian society, Voltaire began to regain his public stature. In the fall of 1732, when the next stage in his career began to unfold, Voltaire was residing at the royal court of Versailles, a sign that his re-establishment in French society was all but complete.

During this rehabilitation, Voltaire also formed a new relationship that was to prove profoundly influential in the subsequent decades. He became reacquainted with Emilie Le Tonnier de Breteuil,the daughter of one of his earliest patrons, who married in 1722 to become the Marquise du Châtelet. Emilie du Châtelet was twenty-nine years old in the spring of 1733 when Voltaire began his relationship with her. She was also a uniquely accomplished woman. Du Châtelet’s father, the Baron de Breteuil, hosted a regular gathering of men of letters that included Voltaire, and his daughter, ten years younger than Voltaire, shared in these associations. Her father also ensured that Emilie received an education that was exceptional for girls at the time. She studied Greek and Latin and trained in mathematics, and when Voltaire reconnected with her in 1733 she was a very knowledgeable thinker in her own right even if her own intellectual career, which would include an original treatise in natural philosophy and a complete French translation of Newton’s Principia Mathematica —still the only complete French translation ever published—had not yet begun. Her intellectual talents combined with her vivacious personality drew Voltaire to her, and although Du Châtelet was a titled aristocrat married to an important military officer, the couple was able to form a lasting partnership that did not interfere with Du Châtelet’s marriage. This arrangement proved especially beneficial to Voltaire when scandal forced him to flee Paris and to establish himself permanently at the Du Châtelet family estate at Cirey. From 1734, when this arrangement began, to 1749, when Du Châtelet died during childbirth, Cirey was the home to each along with the site of an intense intellectual collaboration. It was during this period that both Voltaire and Du Châtelet became widely known philosophical figures, and the intellectual history of each before 1749 is most accurately described as the history of the couple’s joint intellectual endeavors.

For Voltaire, the events that sent him fleeing to Cirey were also the impetus for much of his work while there. While in England, Voltaire had begun to compose a set of letters framed according to the well-established genre of a traveler reporting to friends back home about foreign lands. Montesquieu’s 1721 Lettres Persanes , which offered a set of fictionalized letters by Persians allegedly traveling in France, and Swift’s 1726 Gulliver’s Travels were clear influences when Voltaire conceived his work. But unlike the authors of these overtly fictionalized accounts, Voltaire innovated by adopting a journalistic stance instead, one that offered readers an empirically recognizable account of several aspects of English society. Originally titled Letters on England , Voltaire left a draft of the text with a London publisher before returning home in 1729. Once in France, he began to expand the work, adding to the letters drafted while in England, which focused largely on the different religious sects of England and the English Parliament, several new letters including some on English philosophy. The new text, which included letters on Bacon, Locke, Newton and the details of Newtonian natural philosophy along with an account of the English practice of inoculation for smallpox, also acquired a new title when it was first published in France in 1734: Lettres philosophiques .

Before it appeared, Voltaire attempted to get official permission for the book from the royal censors, a requirement in France at the time. His publisher, however, ultimately released the book without these approvals and without Voltaire’s permission. This made the first edition of the Lettres philosophiques illicit, a fact that contributed to the scandal that it triggered, but one that in no way explains the furor the book caused. Historians in fact still scratch their heads when trying to understand why Voltaire’s Lettres philosophiques proved to be so controversial. The only thing that is clear is that the work did cause a sensation that subsequently triggered a rapid and overwhelming response on the part of the French authorities. The book was publicly burned by the royal hangman several months after its release, and this act turned Voltaire into a widely known intellectual outlaw. Had it been executed, a royal lettre de cachet would have sent Voltaire to the royal prison of the Bastille as a result of his authorship of Lettres philosophiques ; instead, he was able to flee with Du Châtelet to Cirey where the couple used the sovereignty granted by her aristocratic title to create a safe haven and base for Voltaire’s new position as a philosophical rebel and writer in exile.

Had Voltaire been able to avoid the scandal triggered by the Lettres philosophiques , it is highly likely that he would have chosen to do so. Yet once it was thrust upon him, he adopted the identity of the philosophical exile and outlaw writer with conviction, using it to create a new identity for himself, one that was to have far reaching consequences for the history of Western philosophy. At first, Newtonian science served as the vehicle for this transformation. In the decades before 1734, a series of controversies had erupted, especially in France, about the character and legitimacy of Newtonian science, especially the theory of universal gravitation and the physics of gravitational attraction through empty space. Voltaire positioned his Lettres philosophiques as an intervention into these controversies, drafting a famous and widely cited letter that used an opposition between Newton and Descartes to frame a set of fundamental differences between English and French philosophy at the time. He also included other letters about Newtonian science in the work while linking (or so he claimed) the philosophies of Bacon, Locke, and Newton into an English philosophical complex that he championed as a remedy for the perceived errors and illusions perpetuated on the French by René Descartes and Nicolas Malebranche. Voltaire did not invent this framework, but he did use it to enflame a set of debates that were then raging, debates that placed him and a small group of young members of the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris into apparent opposition to the older and more established members of this bastion of official French science. Once installed at Cirey, both Voltaire and Du Châtelet further exploited this apparent division by engaging in a campaign on behalf of Newtonianism, one that continually targeted an imagined monolith called French Academic Cartesianism as the enemy against which they in the name of Newtonianism were fighting.

The centerpiece of this campaign was Voltaire’s Éléments de la Philosophie de Newton , which was first published in 1738 and then again in 1745 in a new and definitive edition that included a new section, first published in 1740, devoted to Newton’s metaphysics. Voltaire offered this book as a clear, accurate, and accessible account of Newton’s philosophy suitable for ignorant Frenchman (a group that he imagined to be large). But he also conceived of it as a machine de guerre directed against the Cartesian establishment, which he believed was holding France back from the modern light of scientific truth. Vociferous criticism of Voltaire and his work quickly erupted, with some critics emphasizing his rebellious and immoral proclivities while others focused on his precise scientific views. Voltaire collapsed both challenges into a singular vision of his enemy as “backward Cartesianism”. As he fought fiercely to defend his positions, an unprecedented culture war erupted in France centered on the character and value of Newtonian natural philosophy. Du Châtelet contributed to this campaign by writing a celebratory review of Voltaire’s Éléments in the Journal des savants , the most authoritative French learned periodical of the day. The couple also added to their scientific credibility by receiving separate honorable mentions in the 1738 Paris Academy prize contest on the nature of fire. Voltaire likewise worked tirelessly rebutting critics and advancing his positions in pamphlets and contributions to learned periodicals. By 1745, when the definitive edition of Voltaire’s Éléments was published, the tides of thought were turning his way, and by 1750 the perception had become widespread that France had been converted from backward, erroneous Cartesianism to modern, Enlightened Newtonianism thanks to the heroic intellectual efforts of figures like Voltaire.

This apparent victory in the Newton Wars of the 1730s and 1740s allowed Voltaire’s new philosophical identity to solidify. Especially crucial was the way that it allowed Voltaire’s outlaw status, which he had never fully repudiated, to be rehabilitated in the public mind as a necessary and heroic defense of philosophical truth against the enemies of error and prejudice. From this perspective, Voltaire’s critical stance could be reintegrated into traditional Old Regime society as a new kind of legitimate intellectual martyrdom. Since Voltaire also coupled his explicitly philosophical writings and polemics during the 1730s and 1740s with an equally extensive stream of plays, poems, stories, and narrative histories, many of which were orthogonal in both tone and content to the explicit campaigns of the Newton Wars, Voltaire was further able to reestablish his old identity as an Old Regime man of letters despite the scandals of these years. In 1745, Voltaire was named the Royal Historiographer of France, a title bestowed upon him as a result of his histories of Louis XIV and the Swedish King Charles II. This royal office also triggered the writing of arguably Voltaire’s most widely read and influential book, at least in the eighteenth century, Essais sur les moeurs et l’esprit des nations (1751), a pioneering work of universal history. The position also legitimated him as an officially sanctioned savant. In 1749, after the death of du Châtelet, Voltaire reinforced this impression by accepting an invitation to join the court of the young Frederick the Great in Prussia, a move that further assimilated him into the power structures of Old Regime society.

Had this assimilationist trajectory continued during the remainder of Voltaire’s life, his legacy in the history of Western philosophy might not have been so great. Yet during the 1750s, a set of new developments pulled Voltaire back toward his more radical and controversial identity and allowed him to rekindle the critical philosophe persona that he had innovated during the Newton Wars. The first step in this direction involved a dispute with his onetime colleague and ally, Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis. Maupertuis had preceded Voltaire as the first aggressive advocate for Newtonian science in France. When Voltaire was preparing his own Newtonian intervention in the Lettres philosophiques in 1732, he consulted with Maupertuis, who was by this date a pensioner in the French Royal Academy of Sciences. It was largely around Maupertuis that the young cohort of French academic Newtonians gathered during the Newton wars of 1730s and 40s, and with Voltaire fighting his own public campaigns on behalf of this same cause during the same period, the two men became the most visible faces of French Newtonianism even if they never really worked as a team in this effort. Like Voltaire, Maupertuis also shared a relationship with Emilie du Châtelet, one that included mathematical collaborations that far exceeded Voltaire’s capacities. Maupertuis was also an occasional guest at Cirey, and a correspondent with both du Châtelet and Voltaire throughout these years. But in 1745 Maupertuis surprised all of French society by moving to Berlin to accept the directorship of Frederick the Great’s newly reformed Berlin Academy of Sciences.

Maupertuis’s thought at the time of his departure for Prussia was turning toward the metaphysics and rationalist epistemology of Leibniz as a solution to certain questions in natural philosophy. Du Châtelet also shared this tendency, producing in 1740 her Institutions de physiques , a systematic attempt to wed Newtonian mechanics with Leibnizian rationalism and metaphysics. Voltaire found this Leibnizian turn dyspeptic, and he began to craft an anti-Leibnizian discourse in the 1740s that became a bulwark of his brand of Newtonianism. This placed him in opposition to Du Châtelet, even if this intellectual rift in no way soured their relationship. Yet after she died in 1749, and Voltaire joined Maupertuis at Frederick the Great’s court in Berlin, this anti-Leibnizianism became the centerpiece of a rift with Maupertuis. Voltaire’s public satire of the President of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Berlin published in late 1752, which presented Maupertuis as a despotic philosophical buffoon, forced Frederick to make a choice. He sided with Maupertuis, ordering Voltaire to either retract his libelous text or leave Berlin. Voltaire chose the latter, falling once again into the role of scandalous rebel and exile as a result of his writings.

This event proved to be Voltaire’s last official rupture with establishment authority. Rather than returning home to Paris and restoring his reputation, Voltaire instead settled in Geneva. When this austere Calvinist enclave proved completely unwelcoming, he took further steps toward independence by using his personal fortune to buy a chateau of his own in the hinterlands between France and Switzerland. Voltaire installed himself permanently at Ferney in early 1759, and from this date until his death in 1778 he made the chateau his permanent home and capital, at least in the minds of his intellectual allies, of the emerging French Enlightenment.

During this period, Voltaire also adopted what would become his most famous and influential intellectual stance, announcing himself as a member of the “party of humanity” and devoting himself toward waging war against the twin hydras of fanaticism and superstition. While the singular defense of Newtonian science had focused Voltaire’s polemical energies in the 1730s and 1740s, after 1750 the program became the defense of philosophie tout court and the defeat of its perceived enemies within the ecclesiastical and aristo-monarchical establishment. In this way, Enlightenment philosophie became associated through Voltaire with the cultural and political program encapsulated in his famous motto, “ Écrasez l’infâme! ” (“Crush the infamy!”). This entanglement of philosophy with social criticism and reformist political action, a contingent historical outcome of Voltaire’s particular intellectual career, would become his most lasting contribution to the history of philosophy.

The first cause to galvanize this new program was Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie . The first volume of this compendium of definitions appeared in 1751, and almost instantly the work became buried in the kind of scandal to which Voltaire had grown accustomed. Voltaire saw in the controversy a new call to action, and he joined forces with the project soon after its appearance, penning numerous articles that began to appear with volume 5 in 1755. Scandal continued to chase the Encyclopédie , however, and in 1759 the work’s publication privilege was revoked in France, an act that did not kill the project but forced it into illicit production in Switzerland. During these scandals, Voltaire fought vigorously alongside the project’s editors to defend the work, fusing the Encyclopédie ’s enemies, particularly the Parisian Jesuits who edited the monthly periodical the Journal de Trevoux , into a monolithic “infamy” devoted to eradicating truth and light from the world. This framing was recapitulated by the opponents of the Encyclopédie , who began to speak of the loose assemblage of authors who contributed articles to the work as a subversive coterie of philosophes devoted to undermining legitimate social and moral order.

As this polemic crystallized and grew in both energy and influence, Voltaire embraced its terms and made them his cause. He formed particularly close ties with d’Alembert, and with him began to generalize a broad program for Enlightenment centered on rallying the newly self-conscious philosophes (a term often used synonymously with the Encyclopédistes ) toward political and intellectual change. In this program, the philosophes were not unified by any shared philosophy but through a commitment to the program of defending philosophie itself against its perceived enemies. They were also imagined as activists fighting to eradicate error and superstition from the world. The ongoing defense of the Encyclopédie was one rallying point, and soon the removal of the Jesuits—the great enemies of Enlightenment, the philosophes proclaimed—became a second unifying cause. This effort achieved victory in 1763, and soon the philosophes were attempting to infiltrate the academies and other institutions of knowledge in France. One climax in this effort was reached in 1774 when the Encyclopédiste and friend of Voltaire and the philosophes , Anne-Robert Jacques Turgot, was named Controller-General of France, the most powerful ministerial position in the kingdom, by the newly crowned King Louis XVI. Voltaire and his allies had paved the way for this victory through a barrage of writings throughout the 1760s and 1770s that presented philosophie like that espoused by Turgot as an agent of enlightened reform and its critics as prejudicial defenders of an ossified tradition.

Voltaire did bring out one explicitly philosophical book in support this campaign, his Dictionnaire philosophique of 1764–1770. This book republished his articles from the original Encyclopédie while adding new entries conceived in the spirit of the original work. Yet to fully understand the brand of philosophie that Voltaire made foundational to the Enlightenment, one needs to recognize that it just as often circulated in fictional stories, satires, poems, pamphlets, and other less obviously philosophical genres. Voltaire’s most widely known text, for instance, Candide, ou l’Optimisme , first published in 1759, is a fictional story of a wandering traveler engaged in a set of farcical adventures. Yet contained in the text is a serious attack on Leibnizian philosophy, one that in many ways marks the culmination of Voltaire’s decades long attack on this philosophy started during the Newton wars. Philosophie à la Voltaire also came in the form of political activism, such as his public defense of Jean Calas who, Voltaire argued, was a victim of a despotic state and an irrational and brutal judicial system. Voltaire often attached philosophical reflection to this political advocacy, such as when he facilitated a French translation of Cesare Beccaria’s treatise on humanitarian justice and penal reform and then prefaced the work with his own essay on justice and religious toleration (Calas was a French protestant persecuted by a Catholic monarchy). Public philosophic campaigns such as these that channeled critical reason in a direct, oppositionalist way against the perceived injustices and absurdities of Old Regime life were the hallmark of philosophie as Voltaire understood the term.

Voltaire lived long enough to see some of his long-term legacies start to concretize. With the ascension of Louis XVI in 1774 and the appointment of Turgot as Controller-General, the French establishment began to embrace the philosophes and their agenda in a new way. Critics of Voltaire and his program for philosophie remained powerful, however, and they would continue to survive as the necessary backdrop to the positive image of the Enlightenment philosophe as a modernizer, progressive reformer, and courageous scourge against traditional authority that Voltaire bequeathed to later generations. During Voltaire’s lifetime, this new acceptance translated into a final return to Paris in early 1778. Here, as a frail and sickly octogenarian, Voltaire was welcomed by the city as the hero of the Enlightenment that he now personified. A statue was commissioned as a permanent shrine to his legacy, and a public performance of his play Irène was performed in a way that allowed its author to be celebrated as a national hero. Voltaire died several weeks after these events, but the canonization that they initiated has continued right up until the present.

Western philosophy was profoundly shaped by the conception of the philosophe and the program for Enlightenment philosophie that Voltaire came to personify. The model he offered of the philosophe as critical public citizen and advocate first and foremost, and as abstruse and systematic thinker only when absolutely necessary, was especially influential in the subsequent development of the European philosophy. Also influential was the example he offered of the philosopher measuring the value of any philosophy according by its ability to effect social change. In this respect, Karl Marx’s famous thesis that philosophy should aspire to change the world, not merely interpret it, owes more than a little debt Voltaire. The link between Voltaire and Marx was also established through the French revolutionary tradition, which similarly adopted Voltaire as one of its founding heroes. Voltaire was the first person to be honored with re-burial in the newly created Pantheon of the Great Men of France that the new revolutionary government created in 1791. This act served as a tribute to the connections that the revolutionaries saw between Voltaire’s philosophical program and the cause of revolutionary modernization as a whole. In a similar way, Voltaire remains today an iconic hero for everyone who sees a positive linkage between critical reason and political resistance in projects of progressive, modernizing reform.

2. Voltaire’s Enlightenment Philosophy

Voltaire’s philosophical legacy ultimately resides as much in how he practiced philosophy, and in the ends toward which he directed his philosophical activity, as in any specific doctrine or original idea. Yet the particular philosophical positions he took, and the way that he used his wider philosophical campaigns to champion certain understandings while disparaging others, did create a constellation appropriately called Voltaire’s Enlightenment philosophy. True to Voltaire’s character, this constellation is best described as a set of intellectual stances and orientations rather than as a set of doctrines or systematically defended positions. Nevertheless, others found in Voltaire both a model of the well-oriented philosophe and a set of particular philosophical positions appropriate to this stance. Each side of this equation played a key role in defining the Enlightenment philosophie that Voltaire came to personify.

Central to this complex is Voltaire’s conception of liberty. Around this category, Voltaire’s social activism and his relatively rare excursions into systematic philosophy also converged. In 1734, in the wake of the scandals triggered by the Lettres philosophiques , Voltaire wrote, but left unfinished at Cirey, a Traité de metaphysique that explored the question of human freedom in philosophical terms. The question was particularly central to European philosophical discussions at the time, and Voltaire’s work explicitly referenced thinkers like Hobbes and Leibniz while wrestling with the questions of materialism, determinism, and providential purpose that were then central to the writings of the so-called deists, figures such as John Toland and Anthony Collins. The great debate between Samuel Clarke and Leibniz over the principles of Newtonian natural philosophy was also influential as Voltaire struggled to understand the nature of human existence and ethics within a cosmos governed by rational principles and impersonal laws.

Voltaire adopted a stance in this text somewhere between the strict determinism of rationalist materialists and the transcendent spiritualism and voluntarism of contemporary Christian natural theologians. For Voltaire, humans are not deterministic machines of matter and motion, and free will thus exists. But humans are also natural beings governed by inexorable natural laws, and his ethics anchored right action in a self that possessed the natural light of reason immanently. This stance distanced him from more radical deists like Toland, and he reinforced this position by also adopting an elitist understanding of the role of religion in society. For Voltaire, those equipped to understand their own reason could find the proper course of free action themselves. But since many were incapable of such self-knowledge and self-control, religion, he claimed, was a necessary guarantor of social order. This stance distanced Voltaire from the republican politics of Toland and other materialists, and Voltaire echoed these ideas in his political musings, where he remained throughout his life a liberal, reform-minded monarchist and a skeptic with respect to republican and democratic ideas.

In the Lettres philosophiques , Voltaire had suggested a more radical position with respect to human determinism, especially in his letter on Locke, which emphasized the materialist reading of the Lockean soul that was then a popular figure in radical philosophical discourse. Some readers singled out this part of the book as the major source of its controversy, and in a similar vein the very materialist account of “ Âme ,” or the soul, which appeared in volume 1 of Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie , was also a flashpoint of controversy. Voltaire also defined his own understanding of the soul in similar terms in his own Dictionnaire philosophique . What these examples point to is Voltaire’s willingness, even eagerness, to publicly defend controversial views even when his own, more private and more considered writings often complicated the understanding that his more public and polemical writings insisted upon. In these cases, one often sees Voltaire defending less a carefully reasoned position on a complex philosophical problem than adopting a political position designed to assert his conviction that liberty of speech, no matter what the topic, is sacred and cannot be violated.

Voltaire never actually said “I disagree with what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” Yet the myth that associates this dictum with his name remains very powerful, and one still hears his legacy invoked through the redeclaration of this pronouncement that he never actually declared. Part of the deep cultural tie that joins Voltaire to this dictum is the fact that even while he did not write these precise words, they do capture, however imprecisely, the spirit of his philosophy of liberty. In his voluminous correspondence especially, and in the details of many of his more polemical public texts, one does find Voltaire articulating a view of intellectual and civil liberty that makes him an unquestioned forerunner of modern civil libertarianism. He never authored any single philosophical treatise on this topic, however, yet the memory of his life and philosophical campaigns was influential in advancing these ideas nevertheless. Voltaire’s influence is palpably present, for example, in Kant’s famous argument in his essay “What is Enlightenment?” that Enlightenment stems from the free and public use of critical reason, and from the liberty that allows such critical debate to proceed untrammeled. The absence of a singular text that anchors this linkage in Voltaire’s collected works in no way removes the unmistakable presence of Voltaire’s influence upon Kant’s formulation.

Voltaire’s notion of liberty also anchored his hedonistic morality, another key feature of Voltaire’s Enlightenment philosophy. One vehicle for this philosophy was Voltaire’s salacious poetry, a genre that both reflected in its eroticism and sexual innuendo the lived culture of libertinism that was an important feature of Voltaire’s biography. But Voltaire also contributed to philosophical libertinism and hedonism through his celebration of moral freedom through sexual liberty. Voltaire’s avowed hedonism became a central feature of his wider philosophical identity since his libertine writings and conduct were always invoked by those who wanted to indict him for being a reckless subversive devoted to undermining legitimate social order. Voltaire’s refusal to defer to such charges, and his vigor in opposing them through a defense of the very libertinism that was used against him, also injected a positive philosophical program into these public struggles that was very influential. In particular, through his cultivation of a happily libertine persona, and his application of philosophical reason toward the moral defense of this identity, often through the widely accessible vehicles of poetry and witty prose, Voltaire became a leading force in the wider Enlightenment articulation of a morality grounded in the positive valuation of personal, and especially bodily, pleasure, and an ethics rooted in a hedonistic calculus of maximizing pleasure and minimizing pain. He also advanced this cause by sustaining an unending attack upon the repressive and, to his mind, anti-human demands of traditional Christian asceticism, especially priestly celibacy, and the moral codes of sexual restraint and bodily self-abnegation that were still central to the traditional moral teachings of the day.

This same hedonistic ethics was also crucial to the development of liberal political economy during the Enlightenment, and Voltaire applied his own libertinism toward this project as well. In the wake of the scandals triggered by Mandeville’s famous argument in The Fable of the Bees (a poem, it should be remembered) that the pursuit of private vice, namely greed, leads to public benefits, namely economic prosperity, a French debate about the value of luxury as a moral good erupted that drew Voltaire’s pen. In the 1730s, he drafted a poem called Le Mondain that celebrated hedonistic worldly living as a positive force for society, and not as the corrupting element that traditional Christian morality held it to be. In his Essay sur les moeurs he also joined with other Enlightenment historians in celebrating the role of material acquisition and commerce in advancing the progress of civilization. Adam Smith would famously make similar arguments in his founding tract of Enlightenment liberalism, On the Wealth of Nations , published in 1776. Voltaire was certainly no great contributor to the political economic science that Smith practiced, but he did contribute to the wider philosophical campaigns that made the concepts of liberty and hedonistic morality central to their work both widely known and more generally accepted.

The ineradicable good of personal and philosophical liberty is arguably the master theme in Voltaire’s philosophy, and if it is, then two other themes are closely related to it. One is the importance of skepticism, and the second is the importance of empirical science as a solvent to dogmatism and the pernicious authority it engenders.

Voltaire’s skepticism descended directly from the neo-Pyrrhonian revival of the Renaissance, and owes a debt in particular to Montaigne, whose essays wedded the stance of doubt with the positive construction of a self grounded in philosophical skepticism. Pierre Bayle’s skepticism was equally influential, and what Voltaire shared with these forerunners, and what separated him from other strands of skepticism, such as the one manifest in Descartes, is the insistence upon the value of the skeptical position in its own right as a final and complete philosophical stance. Among the philosophical tendencies that Voltaire most deplored, in fact, were those that he associated most powerfully with Descartes who, he believed, began in skepticism but then left it behind in the name of some positive philosophical project designed to eradicate or resolve it. Such urges usually led to the production of what Voltaire liked to call “philosophical romances,” which is to say systematic accounts that overcome doubt by appealing to the imagination and its need for coherent explanations. Such explanations, Voltaire argued, are fictions, not philosophy, and the philosopher needs to recognize that very often the most philosophical explanation of all is to offer no explanation at all.

Such skepticism often acted as bulwark for Voltaire’s defense of liberty since he argued that no authority, no matter how sacred, should be immune to challenge by critical reason. Voltaire’s views on religion as manifest in his private writings are complex, and based on the evidence of these texts it would be wrong to call Voltaire an atheist, or even an anti-Christian so long as one accepts a broad understanding of what Christianity can entail. But even if his personal religious views were subtle, Voltaire was unwavering in his hostility to church authority and the power of the clergy. For similar reasons, he also grew as he matured ever more hostile toward the sacred mysteries upon which monarchs and Old Regime aristocratic society based their authority. In these cases, Voltaire’s skepticism was harnessed to his libertarian convictions through his continual effort to use critical reason as a solvent for these “superstitions” and the authority they anchored. The philosophical authority of romanciers such as Descartes, Malebranche, and Leibniz was similarly subjected to the same critique, and here one sees how the defense of skepticism and liberty, more than any deeply held opposition to religiosity per se, was often the most powerful motivator for Voltaire.

From this perspective, Voltaire might fruitfully be compared with Socrates, another founding figure in Western philosophy who made a refusal to declaim systematic philosophical positions a central feature of his philosophical identity. Socrates’s repeated assertion that he knew nothing was echoed in Voltaire’s insistence that the true philosopher is the one who dares not to know and then has the courage to admit his ignorance publicly. Voltaire was also, like Socrates, a public critic and controversialist who defined philosophy primarily in terms of its power to liberate individuals from domination at the hands of authoritarian dogmatism and irrational prejudice. Yet while Socrates championed rigorous philosophical dialectic as the agent of this emancipation, Voltaire saw this same dialectical rationalism at the heart of the dogmatism that he sought to overcome. Voltaire often used satire, mockery and wit to undermine the alleged rigor of philosophical dialectic, and while Socrates saw this kind of rhetorical word play as the very essence of the erroneous sophism that he sought to alleviate, Voltaire cultivated linguistic cleverness as a solvent to the false and deceptive dialectic that anchored traditional philosophy.

Against the acceptance of ignorance that rigorous skepticism often demanded, and against the false escape from it found in sophistical knowledge—or what Voltaire called imaginative philosophical romances—Voltaire offered a different solution than the rigorous dialectical reasoning of Socrates: namely, the power and value of careful empirical science. Here one sees the debt that Voltaire owed to the currents of Newtonianism that played such a strong role in launching his career. Voltaire’s own critical discourse against imaginative philosophical romances originated, in fact, with English and Dutch Newtonians, many of whom were expatriate French Huguenots, who developed these tropes as rhetorical weapons in their battles with Leibniz and European Cartesians who challenged the innovations of Newtonian natural philosophy. In his Principia Mathematica (1687; 2 nd rev. edition 1713), Newton had offered a complete mathematical and empirical description of how celestial and terrestrial bodies behaved. Yet when asked to explain how bodies were able to act in the way that he mathematically and empirically demonstrated that they did, Newton famously replied “I feign no hypotheses.” From the perspective of traditional natural philosophy, this was tantamount to hand waving since offering rigorous causal accounts of the nature of bodies in motion was the very essence of this branch of the sciences. Newton’s major philosophical innovation rested, however, in challenging this very epistemological foundation, and the assertion and defense of Newton’s position against its many critics, not least by Voltaire, became arguably the central dynamic of philosophical change in the first half of the eighteenth century.

While Newtonian epistemology admitted of many variations, at its core rested a new skepticism about the validity of apriori rationalist accounts of nature and a new assertion of brute empirical fact as a valid philosophical understanding in its own right. European Natural philosophers in the second half of the seventeenth century had thrown out the metaphysics and physics of Aristotle with its four part causality and teleological understanding of bodies, motion and the cosmic order. In its place, however, a new mechanical causality was introduced that attempted to explain the world in equally comprehensive terms through the mechanisms of an inert matter acting by direct contact and action alone. This approach lead to the vortical account of celestial mechanics, a view that held material bodies to be swimming in an ethereal sea whose action pushed and pulled objects in the manner we observe. What could not be observed, however, was the ethereal sea itself, or the other agents of this supposedly comprehensive mechanical cosmos. Yet rationality nevertheless dictated that such mechanisms must exist since without them philosophy would be returned to the occult causes of the Aristotelian natural tendencies and teleological principles. Figuring out what these point-contact mechanisms were and how they worked was, therefore, the charge of the new mechanical natural philosophy of the late seventeenth century. Figures such as Descartes, Huygens, and Leibniz established their scientific reputations through efforts to realize this goal.

Newton pointed natural philosophy in a new direction. He offered mathematical analysis anchored in inescapable empirical fact as the new foundation for a rigorous account of the cosmos. From this perspective, the great error of both Aristotelian and the new mechanical natural philosophy was its failure to adhere strictly enough to empirical facts. Vortical mechanics, for example, claimed that matter was moved by the action of an invisible agent, yet this, the Newtonians began to argue, was not to explain what is really happening but to imagine a fiction that gives us a speciously satisfactory rational explanation of it. Natural philosophy needs to resist the allure of such rational imaginings and to instead deal only with the empirically provable. Moreover, the Newtonians argued, if a set of irrefutable facts cannot be explained other then by accepting the brute facticity of their truth, this is not a failure of philosophical explanation so much as a devotion to appropriate rigor. Such epistemological battles became especially intense around Newton’s theory of universal gravitation. Few questioned that Newton had demonstrated an irrefutable mathematical law whereby bodies appear to attract one another in relation to their masses and in inverse relation to the square of the distance between them. But was this rigorous mathematical and empirical description a philosophical account of bodies in motion? Critics such as Leibniz said no, since mathematical description was not the same thing as philosophical explanation, and Newton refused to offer an explanation of how and why gravity operated the way that it did. The Newtonians countered that phenomenal descriptions were scientifically adequate so long as they were grounded in empirical facts, and since no facts had yet been discerned that explained what gravity is or how it works, no scientific account of it was yet possible. They further insisted that it was enough that gravity did operate the way that Newton said it did, and that this was its own justification for accepting his theory. They further mocked those who insisted on dreaming up chimeras like the celestial vortices as explanations for phenomena when no empirical evidence existed to support of such theories.

The previous summary describes the general core of the Newtonian position in the intense philosophical contests of the first decades of the eighteenth century. It also describes Voltaire’s own stance in these same battles. His contribution, therefore, was not centered on any innovation within these very familiar Newtonian themes; rather, it was his accomplishment to become a leading evangelist for this new Newtonian epistemology, and by consequence a major reason for its widespread dissemination and acceptance in France and throughout Europe. A comparison with David Hume’s role in this same development might help to illuminate the distinct contributions of each. Both Hume and Voltaire began with the same skepticism about rationalist philosophy, and each embraced the Newtonian criterion that made empirical fact the only guarantor of truth in philosophy. Yet Hume’s target remained traditional philosophy, and his contribution was to extend skepticism all the way to the point of denying the feasibility of transcendental philosophy itself. This argument would famously awake Kant’s dogmatic slumbers and lead to the reconstitution of transcendental philosophy in new terms, but Voltaire had different fish to fry. His attachment was to the new Newtonian empirical scientists, and while he was never more than a dilettante scientist himself, his devotion to this form of natural inquiry made him in some respects the leading philosophical advocate and ideologist for the new empirico-scientific conception of philosophy that Newton initiated.

For Voltaire (and many other eighteenth-century Newtonians) the most important project was defending empirical science as an alternative to traditional natural philosophy. This involved sharing in Hume’s critique of abstract rationalist systems, but it also involved the very different project of defending empirical induction and experimental reasoning as the new epistemology appropriate for a modern Enlightened philosophy. In particular, Voltaire fought vigorously against the rationalist epistemology that critics used to challenge Newtonian reasoning. His famous conclusion in Candide , for example, that optimism was a philosophical chimera produced when dialectical reason remains detached from brute empirical facts owed a great debt to his Newtonian convictions. His alternative offered in the same text of a life devoted to simple tasks with clear, tangible, and most importantly useful ends was also derived from the utilitarian discourse that Newtonians also used to justify their science. Voltaire’s campaign on behalf of smallpox inoculation, which began with his letter on the topic in the Lettres philosophiques , was similarly grounded in an appeal to the facts of the case as an antidote to the fears generated by logical deductions from seemingly sound axiomatic principles. All of Voltaire’s public campaigns, in fact, deployed empirical fact as the ultimate solvent for irrational prejudice and blind adherence to preexisting understandings. In this respect, his philosophy as manifest in each was deeply indebted to the epistemological convictions he gleaned from Newtonianism.

Voltaire also contributed directly to the new relationship between science and philosophy that the Newtonian revolution made central to Enlightenment modernity. Especially important was his critique of metaphysics and his argument that it be eliminated from any well-ordered science. At the center of the Newtonian innovations in natural philosophy was the argument that questions of body per se were either irrelevant to, or distracting from, a well focused natural science. Against Leibniz, for example, who insisted that all physics begin with an accurate and comprehensive conception of the nature of bodies as such, Newton argued that the character of bodies was irrelevant to physics since this science should restrict itself to a quantified description of empirical effects only and resist the urge to speculate about that which cannot be seen or measured. This removal of metaphysics from physics was central to the overall Newtonian stance toward science, but no one fought more vigorously for it, or did more to clarify the distinction and give it a public audience than Voltaire.

The battles with Leibnizianism in the 1740s were the great theater for Voltaire’s work in this regard. In 1740, responding to Du Châtelet’s efforts in her Institutions de physiques to reconnect metaphysics and physics through a synthesis of Leibniz with Newton, Voltaire made his opposition to such a project explicit in reviews and other essays he published. He did the same during the brief revival of the so-called “vis viva controversy” triggered by du Châtelet’s treatise, defending the empirical and mechanical conception of body and force against those who defended Leibniz’s more metaphysical conception of the same thing. In the same period, Voltaire also composed a short book entitled La Metaphysique de Newton , publishing it in 1740 as an implicit counterpoint to Châtelet’s Institutions . This tract did not so much articulate Newton’s metaphysics as celebrate the fact that he avoided practicing such speculations altogether. It also accused Leibniz of becoming deluded by his zeal to make metaphysics the foundation of physics. In the definitive 1745 edition of his Éléments de la philosophie de Newton , Voltaire also appended his tract on Newton’s metaphysics as the book’s introduction, thus framing his own understanding of the relationship between metaphysics and empirical science in direct opposition to Châtelet’s Leibnizian understanding of the same. He also added personal invective and satire to this same position in his indictment of Maupertuis in the 1750s, linking Maupertuis’s turn toward metaphysical approaches to physics in the 1740s with his increasingly deluded philosophical understanding and his authoritarian manner of dealing with his colleagues and critics.

While Voltaire’s attacks on Maupertuis crossed the line into ad hominem , at their core was a fierce defense of the way that metaphysical reasoning both occludes and deludes the work of the physical scientist. Moreover, to the extent that eighteenth-century Newtonianism provoked two major trends in later philosophy, first the reconstitution of transcendental philosophy à la Kant through his “Copernican Revolution” that relocated the remains of metaphysics in the a priori categories of reason, and second, the marginalization of metaphysics altogether through the celebration of philosophical positivism and the anti-speculative scientific method that anchored it, Voltaire should be seen as a major progenitor of the latter. By also attaching what many in the nineteenth century saw as Voltaire’s proto-positivism to his celebrated campaigns to eradicate priestly and aristo-monarchical authority through the debunking of the “irrational superstitions” that appeared to anchor such authority, Voltaire’s legacy also cemented the alleged linkage that joined positivist science on the one hand with secularizing disenchantment and dechristianization on the other. In this way, Voltaire should be seen as the initiator of a philosophical tradition that runs from him to Auguste Comte and Charles Darwin, and then on to Karl Popper and Richard Dawkins in the twentieth century.

Because of Voltaire’s celebrity, efforts to collect and canonize his writings began immediately after his death, and still continue today. The result has been the production of three major collections of his writings including his vast correspondence, the last unfinished. Together these constitute the authoritative corpus of Voltaire’s written work.

- Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire , edited by A. Beuchot. 72 vols. Paris: Lefevre, 1829–1840.

- Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire , edited by L.E.D. Moland and G. Bengesco. 52 vols. Paris: Garnier Frères, 1877–1885.

- Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire , edited by Theodore Besterman. 135 vols. (projected) Geneva, Banbury, and Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1968–.

Collections of Writings

- The Works of Voltaire: A Contemporary Version , William F. Fleming (ed. and tr.), 21 vols., New York: E.R. Du Mont, 1901. [Complete edition available at the Online Library of Liberty ]

- The Portable Voltaire , Ben Ray Redman (ed.), New York: Penguin Books, 1977.

- Selected Works of Voltaire , Joseph McCabe (ed.), London: Watts, 2007.

- Shorter Writings of Voltaire , J.I. Rodale (ed.), New York: A.S. Barnes, 1960.

- Voltaire in his Letters, Being a Selection of his Correspondence , S.G. Tallentyre (tr.), Honolulu, HI: University Press of the Pacific, 2004.

- Voltaire on Religion: Selected Writings , Kenneth W. Applegate (ed.), New York: F. Ungar, 1974.

- Voltaire: Selected Writings , Christopher Thacker (ed.), London: Dent, 1995.

- Voltaire: Selections , Paul Edwards (ed.), New York: Macmillan, 1989.

- Translations of Voltaire’s major plays are found in: The Works of Voltaire: A Contemporary Version , William F. Fleming (ed. and tr.), New York: E.R. Du Mont, 1901. [Complete edition available at the Online Library of Liberty ]

- Seven Plays (Mérope (1737), Olympia (1761), Alzire (1734), Orestes (1749), Oedipus (1718), Zaire, Caesar) , William Fleming (tr.), New York: Howard Fertig, 1988.

- The Age of Louis XIV (1733) and other Selected Writings , J.H. Brumfitt (ed.), New York: Twayne, 1963.

- The Age of Louis XIV (1733) , Martyn P. Pollack (tr.), London and New York: Dutton, 1978.

- History of Charles XII, King of Sweden (1727) , Honolulu, HI: University Press of the Pacific, 2002.

- History of Charles XII, King of Sweden (1727) , Antonia White and Ragnhild Marie Hatton (eds.), New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1993.

- The Philosophy of History (1764) , New York: The Philosophical Library, 1965.

Essays, Letters, and Stories

- Vol. 1: The Huron (1771), The History of Jenni (1774), The One-eyed Street Porter, Cosi-sancta (1715), An Incident of Memory (1773), The Travels of Reason (1774), The Man with Forty Crowns (1768), Timon (1755), The King of Boutan (1761), and The City of Cashmere (1760).

- Vol. 2: The Letters of Amabed (1769), The Blind Judges of Colors (1766), The Princess of Babylon (1768), The Ears of Lord Chesterfield and Chaplain Goudman (1775), Story of a Good Brahman (1759), An Indian Adventure (1764), and Zadig, or, Destiny (1757).

- Vol. 3: Micromegas (1738), Candide, or Optimism (1758), The World as it Goes (1750), The White and the Black (1764), Jeannot and Colin (1764), The Travels of Scarmentado (1756), The White Bull (1772), Memnon (1750), Plato’s Dream (1737), Bababec and the Fakirs (1750), and The Two Consoled Ones (1756).

- The English Essays of 1727 , David Williams and Richard Walker (eds.), Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1996.

- Epistle of M. Voltaire to the King of Prussia (1738) , Glasgow, 1967.

- The History of the Travels of Scarmentado (1756) , Glasgow: The College Press, 1969.

- Micromégas and other Short Fictions (1738), Theo Cuffe and Haydn Mason (eds.), London and New York: Penguin Books, 2002.

- The Princess of Babylon (1768) , London: Signet Books, 1969.

- The Virgin of Orleans, or Joan of Arc (1755) , Howard Nelson (tr.), Denver: A. Swallow, 1965.

- Voltaire. Essay on Milton (1727) , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1954.

- Voltaire’s Romances , New York: P. Eckler, 1986.

- Zadig, or L’Ingénu (1757), London: Penguin Books, 1984.

- Zadig, or the Book of Fate (1757) , New York: Garland, 1974.

- Zadig, or The Book of Fate an Oriental History (1757) , Woodbridge, CT: Research Publications, 1982.

- The Calas Affair: A Treatise on Tolerance (1762) , Brian Masters (ed.), London: The Folio Society, 1994.

- The Sermon of the Fifty (1759) , J.A.R. Séguin (ed.), Jersey City, NJ: R. Paxton, 1963.

- A Treatise on Toleration and Other Essays , Joseph McCabe (ed.), Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1994.

- A Treatise on Tolerance and other Writings , edited by Brian Masters, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994

- Voltaire. Political Writings , edited by David Williams, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994

Editions of Major Individual Works

- Translated John Hanna. London: Cass, 1967.

- Birmingham, AL: Gryphon Editions, 1991.

- Edited by Theodore Besterman. London: Penguin Books, 2002.

- Translated by Peter Gay. New York: Basic Books, 1962.

- Philosophical Dictionary: A Compendium , Wade Baskin (ed.), New York: Philosophical Library, 1961.

- Philosophical Dictionary: Selections , Chicago: The Great Books Foundation, 1965.

- John Leigh and Prudence L. Steiner (ed.), Indianapolis, IN: Hackett, 2007.

- Leonard Tancock (ed.), London and New York: Penguin Books, 2003.

- Ernest Dilworth (ed.), Mineola, NY: Dover, 2003.

- Nicholas Cronk (ed.), New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- F.A. Taylor (ed.), Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1946.