Home — Essay Samples — Government & Politics — Presidents of the United States — Thomas Jefferson

Essays on Thomas Jefferson

What makes a good thomas jefferson essay topic.

When it comes to writing an essay on Thomas Jefferson, the topic you choose can make all the difference. A good essay topic will engage the reader, showcase your knowledge and critical thinking skills, and provide a unique perspective on the subject matter. So, What Makes a Good Thomas Jefferson essay topic? Here are some recommendations on how to brainstorm and choose an essay topic, what to consider, and What Makes a Good essay topic.

When brainstorming essay topics on Thomas Jefferson, it's essential to consider the aspects of his life, achievements, and impact that interest you the most. Are you passionate about his role as a founding father, his contributions to the Declaration of Independence, his presidency, or his views on democracy and individual rights? Start by making a list of these interests and then consider how you can develop them into a unique and engaging essay topic.

When choosing a Thomas Jefferson essay topic, it's important to consider the relevance and significance of the subject matter. Is the topic you're considering relevant to current events, debates, or scholarly discussions? Will it provide a fresh perspective or shed new light on a lesser-known aspect of Jefferson's life and legacy? A good essay topic should be thought-provoking, relevant, and contribute to the existing body of knowledge on Thomas Jefferson.

A good Thomas Jefferson essay topic should also be specific and focused. Rather than choosing a broad and generic topic, consider narrowing down your focus to a specific aspect of Jefferson's life, work, or impact. For example, instead of writing a general essay on Thomas Jefferson's presidency, you could focus on a specific policy or event during his time in office, such as the Louisiana Purchase or the Embargo Act of 1807.

In addition to these considerations, a good essay topic on Thomas Jefferson should also be well-researched and supported by credible sources. Before finalizing your topic, make sure that there is enough scholarly literature, primary sources, and reliable information available to support your arguments and analysis.

Best Thomas Jefferson Essay Topics

Looking for inspiration for your Thomas Jefferson essay? Here are some creative and stand-out essay topics that go beyond the ordinary and offer a fresh perspective on the life and legacy of this influential figure:

- Thomas Jefferson's views on education and the founding of the University of Virginia

- The role of Thomas Jefferson in shaping American democracy and individual rights

- Thomas Jefferson's complex relationship with slavery and his legacy as a slave owner

- The impact of Thomas Jefferson's foreign policy on the United States' global standing

- Thomas Jefferson's contributions to the field of architecture and his influence on American design

- The legacy of Thomas Jefferson's Declaration of Independence and its relevance in modern society

- The political philosophy of Thomas Jefferson and its influence on American politics

- Thomas Jefferson's role in the Lewis and Clark Expedition and the exploration of the American West

- The personal and public life of Thomas Jefferson: a study in contradictions

- Thomas Jefferson's interest in science, technology, and innovation

- The relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton: conflict and cooperation

- Thomas Jefferson's vision for the future of America and its relevance today

- The impact of Thomas Jefferson's agricultural innovations on American farming practices

- Thomas Jefferson's role as a diplomat and ambassador to France

- The legacy of Thomas Jefferson's writings and correspondence

- Thomas Jefferson's influence on American literature and the arts

- The portrayal of Thomas Jefferson in popular culture and historical memory

- Thomas Jefferson's legacy as a champion of religious freedom and separation of church and state

- The impact of Thomas Jefferson's presidency on the expansion of the United States

- Thomas Jefferson's vision for the relationship between government and the governed

These essay topics offer a wide range of opportunities to explore different aspects of Thomas Jefferson's life, work, and impact from a fresh and unique perspective.

Thomas Jefferson essay topics Prompts

Looking for some creative prompts to spark your imagination and inspire your Thomas Jefferson essay? Here are five engaging and thought-provoking prompts to get you started:

- Imagine you are having a conversation with Thomas Jefferson. What questions would you ask him, and what topics would you want to discuss?

- Write a letter to Thomas Jefferson, sharing your thoughts on his contributions to American democracy and individual rights.

- Create a fictional dialogue between Thomas Jefferson and another historical figure, exploring their differing views on a specific issue or event.

- Imagine you are a reporter covering a significant moment in Thomas Jefferson's life or presidency. Write a news article or feature story capturing the essence of the event.

- Choose a specific aspect of Thomas Jefferson's life or legacy and create a multimedia presentation (such as a podcast, video, or digital exhibition) to showcase its significance and relevance today.

These prompts are designed to encourage creative and critical thinking, as well as provide an opportunity to engage with Thomas Jefferson's life and legacy in a dynamic and interactive way. Have fun exploring these prompts and discovering new insights into the world of Thomas Jefferson.

Jeffersons Non Intercourse Act

Thomas jefferson’s racial views: a complicated legacy, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Thomas Jefferson: Founding Father and President

Thomas jefferson's achievements as the president of the united states, thomas jefferson and his moral character, the life and significant accomplishments of thomas jefferson, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Thomas Jefferson’s Biography

Thomas jefferson, the most important us president, thomas jefferson, the third american president, america's escape from the crutches of thomas jefferson's presidency, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Hofstadter’s Thomas Jefferson: an Original View on an Extraordinary Personality

Declaration of independence by thomas jefferson: critical analysis, benjamin banneker's argument against slavery, thomas jefferson and alexander hamilton: anti-federalist and federalist, thomas jefferson vs. alexander hamilton, hamilton and jefferson's disagreement on federal government power, federalists vs. constructionists: jefferson & madison era, benjamin banneker – a revolutionary figure in american history, benjamin banneker's letter to thomas jefferson: ethos, pathos, logos, thomas jefferson: a hero of vote-based system, the key arguments of jefferson for independence and the declaration of independence from great britain, review of the declaration of independence by thomas jefferson, time after victory: thomas jefferson vs alexander hamilton, thomas jefferson’s maligned actions, the challenges of thomas jefferson, thomas jefferson thesis statement, were the american colonists justified dbq, the declaration of independence: diction analysis, relevant topics.

- Andrew Jackson

- Abraham Lincoln

- Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Barack Obama

- James Madison

- John F. Kennedy

- George Washington

- Electoral College

- Transportation

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Thomas Jefferson

Scholars in general have not taken seriously Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) as a philosopher, perhaps because he never wrote a formal philosophical treatise. Yet Jefferson was a prodigious writer, and his writings were suffuse with philosophical content. Well-acquainted with the philosophical literature of his day and of antiquity, he left behind a rich philosophical legacy in his declarations, presidential messages and addresses, public papers, numerous bills, letters to philosophically minded correspondents, and his only book, Notes on the State of Virginia . Scrutiny of those writings reveals a refined political philosophy as well as a systemic approach to a philosophy of education in partnership with it. Jefferson’s political philosophy and his views on education were undergirded and guided by a consistent and progressive vision of humans, their place in the cosmos, and the good life that owed much to ancient philosophers like Epictetus, Antoninus, and Cicero; to the ethical precepts of Jesus; to coetaneous Scottish empiricists like Francis Hutcheson and Lord Kames; and even to esteemed religionists and philosophically inclined literary figures of the period like Laurence Sterne, Jean Baptiste Massillon, and Miguel Cervantes. In one area, however, he was behindhand: his views on race, the subject of the final section.

1. Life and Writings

2.1 the cosmos, 2.2 nature and society, 3.1 religion and morality, 3.2 the moral sense, 4.1 the “mother principle”, 4.2 the “natural aristoi ”, 4.3 usufruct and constitutional renewal, 4.4 revolution, 5.1 a system of education, 5.2 education and human thriving, primary literature, secondary literature, other internet resources, related entries.

From 1752 to 1757, Jefferson studied under the Scottish clergyman, Rev. William Douglas, “a superficial Latinist” and “less instructed in Greek,” from whom he learned French and the rudiments of Latin and Greek. With the death of his father in 1757, Jefferson earned a substantial inheritance—some £2,400 and some 5,000 acres of land to be divided between him and younger brother, Randolph—and then began to study under Rev. James Maury, “a correct classical scholar” ([Au], p. 4).

From 1760 to 1762, Jefferson attended William and Mary College and there befriended Professor William Small. He wrote in his Autobiography, “It was my great good fortune, and what probably fixed the destinies of my life that Dr. Wm. Small of Scotland was then professor of Mathematics, a man profound in most of the useful branches of science, with a happy talent of communication, correct and gentlemanly manners, & an enlarged & liberal mind.” Small, Jefferson added, had become attached to Jefferson, who became his “daily companion when not engaged in the school.” From Small, Jefferson learned of the “expansion of science & of the system of things in which we are placed” ([Au], pp. 4–5). Small introduced Jefferson to lawyer George Wythe, who “continued to be my faithful and beloved Mentor in youth, and my most affectionate friend through life,” and under whom Jefferson would soon be apprenticed in law—and Wythe introduced Jefferson to Governor Francis Fauquier, governor of Virginia from 1758 till his death ([Au], pp. 4–5). Small and Wythe especially would prove to be cynosures to the young man.

Upon leaving William and Mary (1762) and to the time he began his legal practice (1767), Jefferson, under the tutelage of Wythe ([Au: 5), undertook a rigorous course of study of law, which comprised for him study of not just the standard legal texts of the day but also anything of potential practical significance to advance human affairs. For Jefferson, a lawyer, having a mastery of all things except metempirical subjects and fiction, would be a human encyclopedia of useful knowledge. Advisory letters to John Garland Jefferson (11 June 1790) and to Bernard Moore (30 Aug. 1814) show a lengthy and full course of study, involving physical studies, morality, religion, natural law, politics, history, belle lettres, criticism, rhetoric, and oratory. Thereby, a lawyer would be fully readied for any turn of events in a case. As lawyer, Jefferson’s focus, David Konig notes, was cases involving property—e.g., the legal acquisition of lands and the quieting of titles—and that, adds Konig, shaped his political thinking on the need of the relative equal distribution of property among all male citizens for sound Republican government.

As lawyer, Jefferson took up six pro bono cases of slaves, seeking freedom. In the case of slave Samuel Howell in Howell v. Netherland (Apr. 1770), Jefferson argued, in keeping with sentiments he would include years later in his Declaration of Independence, “Under the law of nature, all men are born free, every one comes into the world with a right to his own person, which includes the liberty of moving and using it at his own will.” The case was awarded to Netherland, before his lawyer, George Wythe, could present his case (Catterall, 90–91).

Jefferson would practice law till August 11, 1774, when he passed his practice to Edmund Randolph at the start of the Revolutionary War.

In 1769, Jefferson gained admittance to the Virginian House of Burgesses. Delegates’ minds were, he said, “circumscribed within narrow limits by an habitual belief that it was our duty to be subordinate to the mother country in all matters of government” ([Au], p. 5). Jefferson’s thinking inclined otherwise. The experience in the House of Delegates substantially shaped his revolutionary spirit.

On February 1, 1770, Jefferson lost most of the books of his first library when a fire razed his house at Shadwell. Of the loss of his books, he wrote to boyhood friend John Page (21 Feb. 1770), “Would to god it had been the money [that the books cost and not the books]; then had it never cost me a sigh!” He was to have two other libraries at Monticello in his life, which, because of his passion for learning, centered on books. When he built his residence at Poplar Forest early in the nineteenth century, he kept there a number of books—focused on philosophy, history, and religion—for his own enjoyment.

Jefferson took as his wife Martha Wayles Skelton on January 1, 1772. In that same year, daughter Martha was born. In 1778, daughter Mary was born.

Upon retirement from law in 1774, Jefferson wrote Summary View of the Rights of British America—“an humble and dutiful address” of complaints addressed to King George III of England. The complaints concerned numerous American rights, contravened, and aimed at “some redress of their injured rights” ([S], 105). Due to its trenchant tone, it earned Jefferson considerable reputation among congressmen as a gifted writer and as a revolutionist.

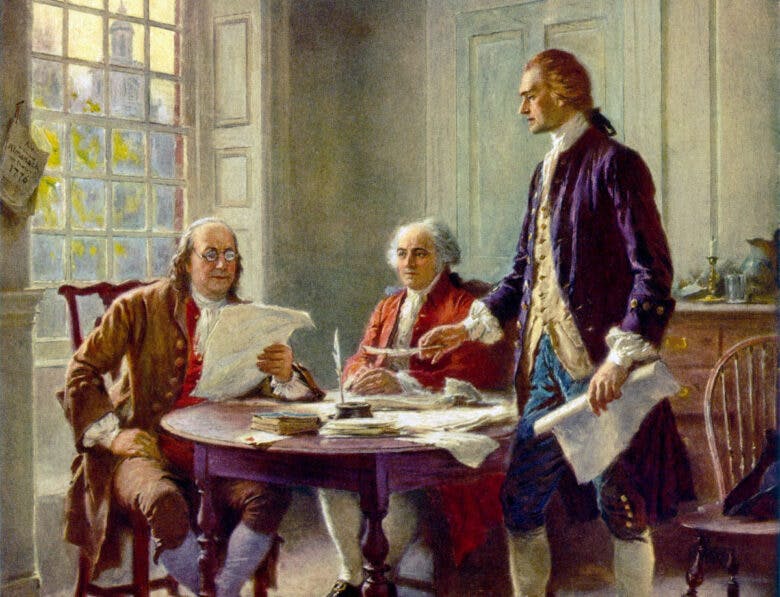

Jefferson was elected to the Continental Congress in 1775 as its second youngest member. He was soon invited to participate in a committee with John Adams, Roger Sherman, Benjamin Franklin, and Robert Livingston to draft a declaration on American independence. It was decided that Jefferson himself should compose a draft. As John Adams writes to Timothy Pickering (6 Aug. 1822) concerning his reasons for Jefferson being the sole drafter of the document: “Reason 1st. You are a Virginian, and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason 2nd. I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular; You are very much otherwise. Reason 3rd. You can write ten times better than I can” (Adams). For over two weeks, Jefferson worked on the Declaration of Independence in an upper-floor apartment at Seventh Street and Market Street in Philadelphia.

The document was intended to be “an expression of the American mind” and was put forth to the “tribunal of the world.” Jefferson’s draft listed certain “sacred & undeniable” truths: that all men are created “equal & independent”; that “from that equal creation,” all have the rights “to the preservation of life, & liberty, & the pursuit of happiness”; that governments, deriving their “just powers from the consent of the governed,” are instituted to secure such rights; and that the people have a right to abolish any government which “becomes destructive of these ends” and to institute a new government, by “laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness” ([D], 19).

Rigorous debate followed. Excisions and changes were made to reduce Jefferson’s draft to three-quarters of its original length, though the basic structure and the argument therein—a tightly structured argument that begins with rights, turns to duties of government, and moves to a justification for revolutionary behavior when citizens’ rights are consistently transgressed by government—was unaltered. Thus, the Declaration contained the rudiments of a political philosophy that would be fleshed out in the decades that followed. The document, not thought to be significant at the time, was approved on July 4, 1776, and it would become one of the most significant political writings ever composed.

Not long after Jefferson finished the Declaration on Independence, he was appointed to a committee to revise the outdated laws of Virginia, as a result of a bill introduced to the General Assembly of Virginia. That was a hefty task, which Jefferson—as part of a committee comprising also Thomas Ludwell Lee, George Mason, Edmund Pendleton, and George Wythe—began in 1776. Of the five, Lee and Mason excused themselves, and revision, comprising 126 bills, was undertaken by Jefferson, Wythe, and Pendleton. Revision was completed in 1779, a period of not quite three years. Notable among the bills Jefferson drafted, were Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge and Bill for Religious Freedom. The latter was passed while Jefferson was in France as Minister Plenipotentiary; the former, requiring educative reforms that demanded a system of public education, did not pass.

From 1779 to 1781, Jefferson began tenure as governor of Virginia. During his governorship, he reformed the curriculum of William and Mary College by “abolishing the Grammar school,” eliminating the professorships in Divinity and Oriental languages, and supplanting them with professorships in Law and Police; Anatomy, Medicine, and Chemistry; and Modern Languages ([Au], p. 5). He also began his only book, Notes on the State of Virginia , in which he described the geography, climate, and people of Virginia and their laws, religions, manners, and commerce, among other things. The book, in general, was well received by his Enlightenment friends and did even more to enhance his reputation as a gifted writer.

Jefferson’s wife Martha died on September 6, 1782. Overwhelmingly distraught, he found some consolation in an invitation to function as Minister to France—he needed to be away from Monticello—which he did from 1784 to 1789. He ended the post at the bidding of George Washington, who asked him to be his Secretary of State—a post he held till 1793. Political disagreements between Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton on political issues resulted in formation of the Republican and Federalist parties—the former, championing small, unobtrusive government and strict constructionism; the latter, larger, strong government and a less strict interpretation of the Constitution. After a brief retirement, he was elected Vice-President of the United States for one term that ended in 1801, and then President of the United States, which lasted two terms. His presidency, which began triumphantly with his conciliatory First Inaugural Address, was highlighted by the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, which doubled the size of the country; the subsequent Lewis and Clark Expedition, which ended in 1806; and the failed Embargo Act of 1807, which aimed, among other things, to punish England during its war with France, by prohibiting exchange of goods. During his tenure as president, his daughter Maria died (1804).

In retirement, Jefferson resumed his domestic life at Monticello, continued as president of the American Philosophical Society (a position he held for nearly 20 years), and began activities that would lead to the birth of the University of Virginia, which opened one year before his death. Irretrievably saddled with debt throughout his retirement, he sold his library, approximately 6,700 books, to Congress in 1815 to pay off some of that debt. He died, as did John Adams, on July 4, 1826. On his obelisk, there was written, upon his request ([E]: 706):

Here was buried Thomas Jefferson Author of the Declaration of American Independence Of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom & Father of the University of Virginia.

Jefferson wrote prodigiously. He penned some 19,000 letters. He published Notes on the State of Virginia (English version) in 1787. He wrote key declarations such as Summary View of the Rights of British Americans (1774), Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms (1775), and the Declaration of Independence (1776); authored numerous bills; and wrote his Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States, a modified copy of which was still in use till 1977. He put together two harmonies, The Philosophy of Jesus (1804)—no copies are known to survive—and The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth (1820), by extracting passages from the New Testament. Last, Jefferson undertook late in life an autobiography (never completed), “for my own ready reference & for the information of my family” ([Au]: 3).

2. Deity, Nature, and Society

Like many other contemporaries he read—e.g., Hutcheson, Kames, Bolingbroke, Tracy, and Hume—Jefferson was an empiricist, and in keeping with Isaac Newton, a dyed-in-the-wool materialist. To John Adams (15 Aug. 1820), he writes, “A single sense may indeed be sometimes decieved, [ 1 ] but rarely: and never all our senses together, with their faculty of reasoning.” Jefferson continues: “‘I feel: therefore I exist.’ I feel bodies which are not myself: there are other existencies then. I call them matter. I feel them changing place. This gives me motion. Where there is an absence of matter, I call it void, or nothing, or immaterial space.” Given matter and motion, everything else, even thinking, is explicable. As all loadstones are magnetic, matter too is merely “an action of a particular organization of matter, formed for that purpose by it’s creator.” Even mind and god are material. “To talk of immaterial existences is to talk of nothings.”

To Massachusetts politician Edward Everett (24 Feb. 1823), Jefferson says that observed particulars are found to be nothing but concretizations of atoms. He cautions, “By analyzing too minutely we often reduce our subject to atoms, of which the mind loses hold.” That suggests a sort of pragmatic atomism— viz ., atoms being merely arbitrary epistemological stopping points in the analysis of matter to keep the mind from entertaining the dizzying thought of dividing without end.

Jefferson, however, was not a metaphysical atomist of the Epicurean sort, but a nominalist like philosopher John Locke (1690). To New Jersey politician Dr. John Manners (22 Feb. 1814), he says:

Nature has, in truth, produced units only through all her works. Classes, orders, genera, species, are not of her works. Her creation is of individuals. No two animals are exactly alike; no two plants, nor even two leaves or blades of grass; no two crystallizations. And if we may venture from what is within the cognizance of such organs as ours, to conclude on that beyond their powers, we must believe that no two particles of matter are of exact resemblance.

Humans categorize out of need, for the “infinitude of units or individuals” outstrips the capacity of memory. There is grouping and subgrouping until there are formed classes, orders, genera, and species. Yet such grouping is man’s doing, not nature’s. [ 2 ] Jefferson begins with biota—the system he questions is the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus’—and works his way down to “particles of matter.”

In Jefferson’s cosmos, which is Stoic-like in etiology, all events are linked. The hand of deity is manifestly behind the etiological arrangements. Jefferson writes to Adams (11 Apr. 1823):

I hold (without appeal to revelation) that when we take a view of the universe; in it’s parts general or particular, it is impossible for the human mind not to percieve and feel a conviction of design, consummate skill, and indefinite power in every atom of it’s composition. The movements of the heavenly bodies, so exactly held in their courses by the balance of centrifugal and centripetal forces; the structure of our earth itself, with its distribution of lands, waters, and atmosphere; animal and vegetable bodies, each perfectly organized whether as insect, man or mammoth; it is impossible not to believe, that there is in all this, design, cause and effect, up to an ultimate cause, a Fabricator of all things from matter and motion, their preserver and regulator while permitted to exist in their present forms, and their regenerator into new and other forms.

The language of perception is in keeping with his empiricism; the language of feel, with his appropriation of philosophers Destutt de Tracy’s (1818/1827: 164) and Lord Kames’ (1758: 250) epistemology. Appeal to an ultimate cause implies a demiurge, of whose nature little can be known other than its superior intelligence and overall beneficence. [ 3 ] There is nothing here or in any other cosmological letters to suggest that deity privileges human life any more than, in David Hume’s words, “that of an oyster” (1755 [1987]: 583).

Jefferson continues in his 1823 letter to Adams. Deity superintends the cosmos. Some stars disappear; others come to be. Comets, with their “incalculable courses”, deviate from regular orbits and demand “renovation under other laws.” Some species of animal have become extinct. “Were there no restoring power, all existences might extinguish successively, one by one, until all should be reduced to a shapeless chaos.”

What precisely does divine superintendence entail?

William Wilson argues that the “‘cut’ of Jefferson’s mind” demands theism—divine interpositionism. He writes:

Calling him a deist registers great misunderstanding of that mind. But the root of his thinking remained Newtonian, including its belief in an omnipresent divine activity in nature. The God of deism from this point of view would be a complete abstraction. As the statistician reduces a person of flesh and blood to a mere integer, so the deist reduces God to a functionary of no real description who abandons nature to a well-ordered dust. (Wilson 2017, 122)

Holowchak thinks that it is unlikely that divine superintendence—i.e., extinction and restoration—implies supernatural intervention in the natural course of events (e.g., TJ to Francis Adrian Van der Kemp, 25 Sept. 1816, and TJ to Daniel Salmon, 15 Feb. 1808). It is probable, thinks Holowchak, that a natural capacity for restoration exists in certain types of matter in the same way that mind, for Jefferson, is in certain types of matter (2013a). Deity’s superintendence is likely the capacity for pre-established cosmic self-regulation comparable in some sense to the work of a thermostat in regulating the temperature of a building. [ 4 ] Following Lord Bolingbroke whose views from Philosophical Works he “commonplaced” early in life ([LCB]: 40–55), Jefferson believed that to posit that God needed to intervene in cosmic events to keep aright them (e.g., by sending down Jesus to save humanity) was to belie the capacities of deity. God, thought Bolingbroke, and Jefferson’s god owed more to Bolingbroke than to any other thinker, got things right the first time.

How for Jefferson does man leave the state of nature and enter into society? Jefferson appeals to nature in what one scholar calls a “middle landscape” manner (Marx 1964: 104–5). The happiest state for humans is one that seeks a middle ground between what is savage and what is “refined.” Jefferson’s vision, thinks Marx, is Arcadian. Jefferson’s aim, early writings indicate (e.g., TJ to James Madison, 20 Dec. 1787 and [NV]: 290–91), was for America to be a pastoral society that had the freedom of primitivism, because it was neither materialist nor manufacturing and it had an abundancy of land. America, because it was neither primitive nor uncultured, could have the trimmings of cultured societies, without their degenerative excesses.

Jefferson’s natural-law theory is Stoical, not Hobbesian or Rousseauian. For Jefferson, the basal laws of nature that obtain when man is in the state of nature are roughly the self-same laws that obtain in civil society. They are also roughly the same basal laws that obtain between states.

The moral duties which exist between individual and individual in the state of nature, accompany them into a state of society, and the aggregate of the duties of all the individuals composing the society constitutes the duties of that society towards any other; so that between society and society the same moral duties exist as did between individuals composing them, while in an unassociated state, and their maker not having released them from those duties on their forming themselves into a nation ([F]: 423).

The ideological frame that allows for social stability is in the Declaration of Independence, in which Jefferson lists two self-evident truths: the equality of all men and their endowment of unalienable rights.

“Equality” for Jefferson comprises equality of opportunity and moral equality. Equality of opportunity recognizes the differences between persons—e.g., talents, prior social status, education, and wealth—and seeks to level the playing field through republican reforms such as introduction of a bill to secure human rights; elimination of primogeniture, entails, and state-sanctioned religion; periodic constitutional renewal; and and educational reform for the self-sufficiency of the general citizenry. To remedy the unequal distribution of property, Jefferson advocates in his Draft Constitution for Virginia that 50 acres of property go to every male Virginian [ 5 ] ([CV]: 343). Moral equality recognizes that each human deserves equal status in personhood and citizenship, hence again the need of republican reforms of the sort listed above.

Rights are held to obtain, whether or not holders recognize them, and they have a moral dimension apart from their obvious legal dimension. There are, for instance, the moral obligations to obey the law and to recognize and uphold the rights of others. [ 6 ]

Jefferson, mostly following Locke, mentions three unalienable rights in the Declaration of Independence: life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness. The right to life constitutes a right to one’s own personhood. The rights to liberty and pursuit of happiness (Locke lists property instead of happiness) entail self-determination through labor, art, industry, and self-governance. Government has no right to control the lives of its citizens or dictate a course of happiness. Therein lies the foundation of Jeffersonian liberalism.

There is also the right to revolution, which entails the right to abolish any tyrannical form of government, given long abuses.

3. Morality

The right to the pursuit of happiness implies too that all persons are free to worship as they choose. Since religion is a matter between a man and his deity (e.g., TJ to Miles King, 26 Sept. 1814), no one owes any account of his faith to another. Moreover, legislature should make “no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” thus building a wall of separation between church and state ([DB]: 510). [ 7 ]

Being personal, religion ought not to be politicized. When the clergy engraft themselves into the “machine of government,” they prove a “very formidable engine against the civil and religious rights of man” (TJ to Jeremiah Moor, 14 Aug. 1800). All people, Jefferson asserts, should follow the example of the Quakers: live without priests, be guided their internal monitor of right and wrong, and eschew matters inaccessible to common sense, for belief can only rightly be shaped by “the assent of the mind to an intelligible proposition” (TJ to John Adams, 22 Aug. 1813).

The true principles of morality are the “mild and simple principles of the Christian philosophy” (TJ to Gerry Elbridge, 29 Mar. 1801)—the principles common to all right-intended religions. Jefferson writes to Thomas Leiper (21 Jan. 1809):

My religious reading has long been confined to the moral branch of religion, which is the same in all religions; while in that branch which consists of dogmas, all differ, all have a different set. The former instructs us how to live well and worthily in society; the latter are made to interest our minds in the support of the teachers who inculcate them. [ 8 ]

Thus, the principles common to all religions are few, exoteric, and the true principles of morality. [ 9 ]

Though chary of sectarian religion due to the empleomania of sectarian clerics and a sharp critic of Christianity in his youth ([NR]), “Christianity,” deterged of its political trappings and metaphysical twaddle, in time became special to Jefferson (e.g., TJ to John Adams, 12 Oct. 1813 and 24 Jan. 1814). He states to Dr. Benjamin Rush (21 Apr. 1803):

I am a Christian, in the only sense [Jesus] wished any one to be; sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to him every human excellence; & believing he never claimed any other.

Jesus’ teachings make up the greatest moral system, and Jesus is “the greatest of all the [religious] reformers.” [ 10 ] To Benjamin Waterhouse (26 June 1822), Jefferson writes:

The doctrines of Jesus are simple, and tend all to the happiness of man. 1. That there is one only God, and he all perfect. 2. That there is a future state of rewards and punishments. 3. That to love God with all thy heart and thy neighbor as thyself, is the sum of religion.

Consequently, Jesus’ message comprises love of god (being one, pace Calvin, not three), love of mankind, and belief in an afterlife of reward or punishment.

Yet much in the Bible, Jefferson thought, was redundant, hyperbolic, bathetic, absurd, and beyond the bounds of physical possibility (e.g., TJ to John Adams, 28 Oct. 1813). That was confirmed by inspection of a late-in-life “harmony” Jefferson constructed, The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth (1820), in which the virgin birth, miraculous cures, and resurrection were excised. Christ was neither the savior of mankind nor the son of God, but the great moral reformer of the Jewish religion([B]).

Even after he purged the Bible of its corruptions—in his own words, after he plucked, in an oft-used metaphor, the diamonds from the dungheap (TJ to John Adams, 12 Oct. 1813, and TJ to )—to try both to make plain Jesus’ true teachings and to give a credible account of the life of Jesus, Jefferson did not completely follow Jesus’ uncontaminated teachings. He did think love of God was needed for one to be of upstanding virtue, for each could see and feel the existence of deity in the cosmos. Thus, atheists, however ostensibly virtuous, suffered from a defect of moral sensibility. Yet when Jefferson expressed his own view on the branches of morality (true religion), he did not mention belief in an afterlife, as did Jesus. [ 11 ] His 1814 letter to Law (13 June) mentions belief in an afterlife merely as one of the correctives to lack of a moral sense, along with self-interest, the approbation of others upon doing good, and the rewards and punishments of laws. Given that, along with his out-and-out commitment to materialism and given the evidence of four letters that unequivocally express skepticism apropos of an afterlife, [ 12 ] and given that he and his wife wrote about the “eternal separation” they were about to make on her deathbed, it is probable, asserts one scholar, that he did not believe in an afterlife (Holowchak 2019a, pp. 128–2). So, belief in an afterlife, one of the chief teachings of Jesus, was likely not an essential part of morality for Jefferson. In contrast, Charles Sanford, noting that Jefferson appeals to the hereafter in several letters and addresses, offers a small-step argument in defense of belief in an afterlife. “‘The prospects of a future state of retribution for the evil as well as the good done while here’ [are] among the moral forces necessary to motivate individuals to live good lives in society.” He adds: “Jefferson had begun with the conviction that God had created in man a hunger for the rights of equality, freedom, and life and a desire to follow God’s moral law. It was only a small step further to believe that God had also created man with an immortal soul” (152). [ 13 ]

Finally, Jefferson later in life claimed to be a Unitarian. What did “Unitarianism” mean for him?

Jefferson finds the notion of three deities in one inscrutable, and therefore physically impossible. Here he falls back on his naturalism. He allows nothing inconsistent with the laws of nature, gleaned through experience. The sort of Unitarianism Jefferson promotes is not a religious sect, but instead a manner of approaching religion. Of his Unitarianism, Jefferson asserts to John Adams (22 Aug. 1813), “We should all then, like the Quakers, live without an order of priests, moralize for ourselves, follow the oracle of conscience, and say nothing about what no man can understand, nor therefore believe.” To Dr. Thomas Cooper (2 Nov. 1822), Jefferson contrasts Unitarians with sectarian preachers, so Unitarians can be grasped as persons living fully in accordance with the dictates of their moral sense faculty. To Benjamin Waterhouse (8 Jan. 1825), Jefferson states that Unitarianism is “primitive Christianity, in all the simplicity in which it came from the lips of Jesus.” Such letters show plainly that monotheism, incomplexity, and non-sectarianism are dependent issues. Jefferson made purchase of monotheism because it and benevolence were key tenets of Jesus’ uncorrupted teachings. Those two tenets, letters indicate, were the framework of his Unitarianism, or of any right religion.

For Jefferson, morality was not reason-guided, but dictated by a moral sense. Here he followed Scottish empiricists, [ 14 ] such as William Small (Hull 1997: 102–5 and [Au]: 4–5)—the only non-minister at William and Mary College—and Francis Hutcheson and especially Lord Kames. [ 15 ]

To nephew Peter Carr (19 Aug. 1785), Jefferson says that the god-given moral sense, innate and instinctual, is as much a part of a person’s nature as are the senses of hearing and seeing, or as is a leg or arm. Jefferson’s comparisons to hearing and sight invite depiction of the moral sense tied to a bodily organ, like the heart (TJ to Maria Cosway, 12 Oct. 1785). Like strength of limbs, it too is given to persons in a greater or lesser degree, and can be made better or worse through exercise or its neglect.

A letter to daughter Martha (11 Dec. 1783) suggests the moral sense works spontaneously, without any input of reason. The language of “feel” is critical.

If ever you are about to say any thing amiss or to do any thing wrong, consider before hand. You will feel something within you which will tell you it is wrong and ought not to be said or done: this is your conscience, and be sure to obey it. [ 16 ]

One ought to resist the temptation to act viciously in circumstances when vice will not be detected. He tells Carr (19 Aug. 1785) to act always and in all circumstances as if everyone in the world were looking at him. Jefferson bids grandson Thomas Jefferson Randolph (24 Nov. 1808) to appeal to moral exemplars before acting, and he lists Small, Wythe, and Peyton Randolph. “I am certain that this mode of deciding on my conduct, tended more to correctness than any reasoning powers I possessed.” Thus, one can use the moral sense unerringly, or relatively so, if one disregards the intrusions of reason and assumes that all of one’s actions are under the scrutiny of cynosures—i.e., there will be no temptation to act from the pressure of peers. In another letter to Carr (10 Aug. 1787), Jefferson disadvises his nephew to attend lectures on moral philosophy and appeals counterfactually to a ham-handed creator. “He who made us would have been a pitiful bungler if he had made the rules of our moral conduct a matter of science.” Here and elsewhere, [ 17 ] Jefferson is explicit that reason is uninvolved in moral “judgments.”

Not everyone possesses a moral sense. Napoleon, he tells Adams (25 Feb. 1823), is an illustration. To Thomas Law (13 June 1814), Jefferson says that want of the moral sense can somewhat be rectified by education and employment of rational calculation, but such educative remedies are blandishments not aimed to encourage morally correct action, because that is impossible without a moral sense, but to discourage actions with pernicious consequences. In short, one without a moral sense can be induced or shaped to behave as if having a moral sense, though such actions would merely be consistent with morally correct actions, not be morally correct actions.

Finally, the function of reason, he says in his 1787 letter to Carr, is “in some degree” to oversee the exercise of the moral faculty, “but it is a small stock which is required for this”. Reason might function, thinks one scholar, (1) to encourage or reinforce morally correct action, [ 18 ] (2) to keep the moral sense vital and vigorous, (3) to instill the first elements of morality in children through exposure to history, (4) to allow for cultural sensitivity to morally retarded cultures, (5) to continue moral advance through reading history as adults, (6) to help make plain the rights (especially derivative rights) of humans, (7) to form general rules to serve as rough guides human action, [ 19 ] and (8) to encourage moral improvement through breeding for morality (Holowchak 2014b, 177–80). None of those functions, however, directly involves reason in moral “judgments.”

Jefferson also believed, following the lead of many thinkers of his day—e.g., Francis Ferguson, John Millar, Lord Kames (1798 and 1774), William Robertson, Claude Adrien Helvétius, the Marquis de Condorcet, and Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot—that humans were morally progressing over time (e.g., TJ to John Adams, 11 Jan. 1816, and TJ to P.S. Dupont de Nemours, 24 Apr. 1816). There were, however, periodic glitches—periods of moral stagnation or decline. The belligerence between England and France in Jefferson’s later years was to him evidence of such decline. Still, such moral declinations, considered overall, were temporary setbacks or “retrogradations,” not genuine declinations. In a letter to Adams (1 Aug. 1816), he writes that the Americas will show Europe the path to moral advance.

We are destined to be a barrier against the returns of ignorance and barbarism. Old Europe will have to lean on our shoulders, and to hobble along by our side, under the monkish trammels of priest and kings, as she can.

Thus, moral progress is movement, prompted by embrace of liberty and respect for humans’ rights, toward the ideals of love of deity and love of humanity through beneficence—the ideals taught best by Jesus. [ 20 ]

4. Political Philosophy

In his First Inaugural Address (1801), Jefferson lists the “essential principles of our Government” in 15 doctrines—perhaps his first attempt at a definition of republicanism ([I 1 ]: 494–95).

- Equal and exact justice to all men, irrespective of political or religious persuasion;

- peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, without entangling alliances to any;

- Federal support in the rights of states’ government;

- preservation of constitutional vigor of the Federal government;

- election by the people;

- absolute acquiescence in the decisions of the majority;

- a well-disciplined militia;

- supremacy of the civil over the military authority;

- light taxation;

- ready payment of debts;

- encouragement of agriculture and commerce;

- the diffusion of information and arraignment of all abuses at the bar of the public reason;

- freedom of the press;

- protection by habeas corpus and trial by juries impartially selected; and

- freedom of religion.

Fifteen years later in a series of letters, Jefferson again grapples with a definition of “republicanism.” To P.S. Dupont de Nemours (24 Apr. 1816), Jefferson lists nine “moral principles” upon which republican government is grounded.

I believe with you that morality, compassion, generosity, are innate elements of the human constitution; that there exists a right independent of force; that a right to property is founded in our natural wants, in the means with which we are endowed to satisfy these wants, and the right to what we acquire by those means without violating the similar rights of other sensible beings; that no one has a right to obstruct another, exercising his faculties innocently for the relief of sensibilities made a part of his nature; that justice is the fundamental law of society; that the majority, oppressing an individual, is guilty of a crime, abuses its strength, and by acting on the law of the strongest breaks up the foundations of society; that action by the citizens in person, in affairs within their reach and competence, and in all others by representatives, chosen immediately, and removable by themselves, constitutes the essence of a republic; that all governments are more or less republican in proportion as this principle enters more or less into their composition; and that a government by representation is capable of extension over a greater surface of country than one of any other form.

Among the nine principles, the seventh

Action by the citizens in person, in affairs within their reach and competence, and in all others by representatives, chosen immediately, and removable by themselves, constitutes the essence of a republic.

comes closest to the essence of republicanism. To John Taylor (28 May 1816), Jefferson attempts a “precise and definite idea” of republicanism:

A government by its citizens in mass, acting directly and personally, according to rules established by the majority.

Every other government is more or less republican, in proportion as it has in this composition more or less of this ingredient of the direct action of the citizens.

To Samuel Kercheval (12 July 1816), Jefferson gives his “mother principle”:

Governments are republican only in proportion as they embody the will of their people, and execute it.

A government is republican in proportion as every member composing it has his equal voice in the direction of its concerns (not indeed in person, which would be impracticable beyond the limits of a city, or small township, but) by representatives chosen by himself, and responsible to him at short periods).

Such writings suggest the following “barebones” definition of “republic” for Jefferson, or a “Jeffersonian republic”:

A government is a Jeffersonian republic if and only if it allows all citizens ample opportunity to participate politically in affairs within their reach and competency; it employs representatives, chosen and recallable by the citizenry and functioning for short periods, for affairs outside citizens’ reach and competency; it functions according to the rules (periodically revisable) established by the majority of the citizens; and it guarantees the equal rights, in person and property, of all citizens.

The definition is barebones for several reasons. First, it does not fully capture the normative essence of Jefferson’s description of what is “proper for all conditions of society” in his letter to Dupont de Nemours. Yet it is not normatively neutral, as it speaks of equality of opportunity for each citizen to participate in government and it guarantees equal rights. Second, the definition ignores the partnership of politics and science, which is part of Jefferson’s conception of a republic. Jefferson insisted on periodic revisions of the Constitution at conventions to accommodate changes in the peoples’ will, when suitably informed. Such changes were not arbitrary, but dictated mostly by advances in science. [ 21 ] Jefferson writes to Samuel Kercheval (12 July 1816), “The laws and constitutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind.” Thus, a republic for Jefferson is essentially progressive and scientific, not static and conservative.

Thus, Jeffersonian republicanism is a schema for government by the people, not any particular system of governing. It is not wedded to any particular constitution—constitutions, Jefferson is clear, are merely provisional representations of the will of the people at the time of their drafting (TJ to George Washington, 7 Nov. 1792)—but to the principle of government representing the will of the people, suitably informed. That is why Jefferson says in his First Inaugural Address that for the will of the majority to be reasonable, it must be rightful ([I 1 ]: 493). [ 22 ] Thus, Jeffersonian republicanism is essentially in partnership with science.

Jefferson’s attempts at defining “republic” and his nine moral principles “proper for all conditions of society” shows that republicanism is a political philosophy. For Jefferson, republican governing is essentially progressive, and being government of and for the people, it aims at involving all citizens to their fullest capacity. Over the centuries, he recognized, human potentiality had been stifled by coercive governments. Instantiation of republican governing, thus, was an attempt to impose the minimal political structure needed to maximize human liberty, free human potentiality, and ensure the political ascendency of the “natural aristoi, ” the talented and virtuous, and not the “artificial aristoi, ” the wealthy and wellborn.

Jefferson’s republicanism was both democratic and meritocratic. It was democratic in that it aimed roughly to have no person disadvantaged at the start of life. That would be the same for Blacks, who were the equals of all others in moral sensibility—hence, their desert of equal rights and equal opportunities. Democratic republicanism demanded recognition of moral equality and equality of opportunity. Yet Jefferson realized that each person’s dreams, intelligence, and talents varied greatly. Thus, Jeffersonian republicanism was also meritocratic in that all persons were allowed to do with their life what they saw fit to do with it, so long as in doing so they did not disallow others the opportunity of doing what they saw fit to do. The most talented and virtuous, he assumed, would naturally strive to exercise fully their talents and virtue through politics and science.

Jefferson recognized two classes of people: laborers and learned (TJ to Peter Carr, 7 Sept. 1814). His distinction, however, was not determined by birth or wealth, as it was by most others of his day, but by merit. To John Adams (28 Oct. 1813), Jefferson writes:

There is a natural aristocracy among men. The grounds of this are virtue and talents.

There is also an artificial aristocracy founded on wealth and birth, without either virtue or talents; for with these it would belong to the first class.

What Jefferson claimed here was that the traditional, centuries-old class distinction, founded on birth or wealth, was in effect politically obsolete. What made men “best” was talent (i.e., skill, ambition, and genius) and virtue.

Jefferson then tells Adams that the natural aristoi comprise “the most precious gift of nature for the instruction, the trust, and government of society.” He adds that that government is best which allows for “a pure selection of these natural aristoi into the offices of government.” Through “instruction, trust, and government,” the natural aristoi will be not only political officials, but also teachers, trustees, and practitioners or patrons of science. [ 23 ]

To ensure that political offices will be held by the natural aristoi , there must be, inter alia , public access to general education and free presses for dissemination of information to the citizenry. With the citizenry generally educated, one has, Jefferson continues to Adams, merely “to leave to the citizens the free election and separation of the aristoi from the pseudo- aristoi, ” and “in general they will elect the real good and wise.” [ 24 ] That is much preferable to the centuries-old method of allowing the wealthy and wellborn to govern at the expense of the people.

For Jefferson, constitutions, unlike the rights of men, are alterable, in conformance to the level of progress of a state. Thus, constitutions are to be replaced, altered, or renewed pursuant to humans’ intellectual, political, and moral progress.

To James Madison (6 Sept. 1789), Jefferson writes:

The question Whether one generation of men has a right to bind another … is a question of such consequences as not only to merit decision, but place also, among the fundamental principles of every government. [ 25 ]

Beginning with the evident proposition—“the earth belongs in usufruct to the living”—Jefferson aims to prove that the deeds of each generation, defined by a nineteen-year period, [ 26 ] ought to be independent (or relatively so) of each other. Moreover, “usufruct” implies that each generation has an obligation to leave behind their property to the subsequent generation at least in the same condition in which it was received. For instance, any debts one incurs while owning some land are not to be inherited by another who obtains possession of that land after the former passes. What applies to individuals applies to any collection of individuals.

To instantiate the principle, there must be a period of adjustment. Present debts will be a matter of honor and expediency; future debts will be constrained by the principle. To constrain future debts, a constitution ought to stipulate that a nation can borrow no more than it can repay in the span of a generation. Temperate borrowing would “bridle the spirit of war,” inflamed much by the neglect of repayment of debts.

Usufruct theoretically fits neatly with Jefferson’s notions of political progress and of periodic constitutional renewal. Concerning the latter, he writes to C.F.W. Dumas (10 Sept. 1787):

No society can make a perpetual constitution, or even a perpetual law. … Every constitution, then, and every law, naturally expires at the end of 19. years. If it be enforced longer, it is an act of force and not of right.

At the end of nineteen years, there will be a constitutional convention, at which defects in laws can be addressed and changes can be made. [ 27 ] Should the principle of usufruct be adopted, republican government would have a built-in mechanism for obviating revolutions. [ 28 ] Without the debts and wars of one generation passed on to the next in a Jeffersonian republic and with that republic’s constitution being renewed each generation to accommodate the needs and advances of the next generation, Jefferson thinks, the stage is set for political progress.

James Madison wrote a lengthy letter several months later (4 Feb. 1790) in reply to Jefferson’s usufruct letter, and politely proffered “some very powerful objections.” Jefferson never answered that letter, though he never renounced generational sovereignty.

Even well-intended governments can still go astray. Jefferson writes in his Declaration of Independence,

Whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it, & to institute new government, laying it’s foundation on such principles, & organizing it’s powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety & happiness ([D]: 19).

However, long-standing governments ought not to be changed “for light & transient causes,” otherwise one risks supplantation of a corrupt government with another that is equally or more corrupt. Yet

when a long train of abuses & usurpations pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is [citizens’] right, it is their duty to throw off such government, & to provide new guards for their future security ([D]: 19).

In his Summary View of the Rights of British America, Jefferson states that for revolution to occur, there needs to be “many unwarrantable encroachments and usurpations” ([S]: 105). He adds,

Single acts of tyranny may be ascribed to the accidental opinion of a day; but a series of oppressions, begun at a distinguished period, and pursued unalterably through every change of ministers, too plainly prove a deliberate and systematical plan of reducing us to slavery ([S]: 110).

Therefore, a government becomes destructive when its abuses and usurpations are (1) many and long, (2) directed to the same end, and (3) clearly indicative of despotism.

For Jefferson, some amount of turbulence is one of the consequences of liberty. The manure of blood is needed for healthy governing because those governing will tend over time, Jefferson says to William S. Smith (13 Nov. 1787), to govern in their own interests, if not carefully watched. Moreover, those governed will assume mistakenly that rights once granted will be rights always granted. So, rebellion is the mechanism whereby those governing, Jefferson tells James Madison (30 Jan. 1787), are periodically reminded that government in a Jeffersonian republic is of and for the people—that is, that the will of the majority, fittingly educated, is the standard of justice.

The turbulence of which Jefferson speaks in the letters to Smith and Madison are illustrations of rebellion, says Holowchak (2019a, 73–76), not revolution. In contrast, revolution for Jefferson, following his Declaration, is a complex phenomenon. Unlike a rebellion, it is never to be undertaken for slight reasons or because of singular cases of governmental abuse. The difference, for Holowchak, is one of scope, size, and persistency. Rebellions, often violent, are generally quick signals to government concerning abuses, usually parochial. Revolutions, essentially violent, are long-term, well-planned, complex attempts at overthrowing a government, deemed habitually abusive.

One thing is clear. Revolutions or elitist rebellions, for Jefferson, are larger, more persistent, and more complex than rebellions or populist rebellions. To John Adams (4 Sept. 1823), Jefferson writes of the beginning, sustainment, and resolution of revolutions. “The generation which commences a revolution can rarely compleat it. Habituated from their infancy to passive submission of body and mind to their kings and priests, they are not qualified, when called on, to think and provide for themselves, and their inexperience, their ignorance and bigotry make them instruments often, in the hands of the Bonapartes and Iturbides to defeat their own rights and purposes.” Revolutions cannot be expected to establish a sustainable, free government in the first effort.

Moreover, the revolutionary generation is generally suited to begin and sustain the revolution, Jefferson continues in the letter to Adams, but not to resolve it. It is, for Jefferson, incapable of fixing a viable republican constitution. There are, thus, generational responsibilities for a Jeffersonian revolution to succeed. The role of the first generation is inchoation. Subsequent generations must sustain and complete the initial effort to usurp the coercive government. In the final stage, there is implementation of a constitution, reflective of and beholden to the will of the people.

It is because of the complexity and cost, in terms of human lives, that Jefferson maintained that revolutions ought only to be undertaken in cases of extreme, consistent despotism. As he writes in his Declaration ([D]: 19), “When a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them [the people] under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.” Still, he thought that they were “mechanisms” needed in republican governments, for there is a human tendency for those in power to be seduced by that power (TJ to Spencer Roane, 9 Mar. 1821).

5. Philosophy of Education

Jefferson’s views on education fit hand in glove with his political philosophy. [ 29 ] To facilitate a government of and for the people, there must be educational reform to allow for the general education of the citizenry for fullest political participation, to enable citizens to carry on daily affairs without governmental intervention, and to funnel the most talented and virtuous to a first-tier institution like the University of Virginia.

The sources of Jefferson’s views on education were many. From the French, Jefferson learned that education ought to be equalitarian, secular, and philosophically grounded (Arrowood 1930 [1970]: 49–50). He likely studied the works of Condorcet, La Chalotais, Diderot, Charon, and Turgot, and was influenced by men such as Lafayette, Correa de Serra, Cuvier, Buffon, Humboldt, and Say. Moreover, Jefferson corresponded with or read the works of Britons and Americans such as John Adams, Priestley, Locke, Thomas Cooper, Pictet, Stewart, Tichnor, Richard Price, William Small, Wythe, Fauquier, Peyton Randolph, and Patrick Henry (Holowchak 2014a, 69). That education ought to be scientific and useful was emphasized by William Small at William and Mary College as well as his uptake of the empirical philosophers of his day and their disdain of metempirical squabbling.

Jefferson’s educational views are spelled out neatly in four bills proposed to the General Assembly of Virginia (1779), in his Bill for Establishing a System of Public Education (1817), in his Rockfish Gap Report (1818), and in key letters to correspondents—e.g., Carr, Banister, Munford, Adams, Cabell, Burwell, Brazier, and Breckinridge.

When Jefferson, Pendleton, and Wythe undertook the task of revising the laws of Virginia in 1776, Jefferson drafted four significant bills—Bills 79 to 82.

I consider 4 of these bills … as forming a system by which every fibre would be eradicated of ancient or future aristocracy; and a foundation laid for a government truly republican. [ 30 ] ([WTJ5]: 44)

Bill 79 proposed to create wards or hundreds, each of which would have a school for general education in which “reading, writing, and common arithmetic should be taught” ([BG]). Virginia was to be subdivided in twenty-four districts, each of which would have a school for “classical learning, grammar, geography, and the higher branches of numerical arithmetic” ([BG]). Bill 80 proposed to secularize William and Mary College and add to its curriculum by enlarging its “sphere of science” ([BWM]). [ 31 ] Bill 81 proposed to create a public library for Virginia for scholars, elected officials, and inquisitive citizens ([BL]). Bill 82, the only bill that would eventually pass (1786), proposed to disallow state patronage of any particular religion ([BR]; [Au]: 31–44).

Jefferson made it clear (TJ to George Wythe, 13 Aug. 1786) that Bill 79—concerning implementation of wards and ward schools—was “the most important bill of our whole code”, as it was the “foundation … for the preservation of freedom and happiness” in a true republic. It was the key to engendering the sort of reforms needed for Jeffersonian republicanism—reforms aimed at an educated and thriving citizenry.

It is an axiom in my mind that our liberty can never be safe but in the hands of the people themselves, and that too of the people with a certain degree of education,

he says to George Washington (4 Jan. 1786). “Wherever the people are well-informed, they can be trusted with their own government,” he writes to philosopher Richard Price (8 Jan. 1789). [ 32 ]

Yet Jefferson’s trust in the people was not unconditional. He never asserted categorically that government for and of the people must, or even can, work. Experience had shown him that governments in which officials were not elected by and beholden to the people did not work—i.e., they were ultimately unresponsive to the needs of the people—and so he often called republicanism an “experiment” or “great experiment” (TJ to John Adams, 28 Feb. 1796, and WTJ5: 484). If citizens’ rights were to be respected and defended and if governors were not to govern in their own best interest but as stewards f the citizenry, all citizens needed a basic education—hence, the indispensability of ward-school education.

Given two classes of citizens, the laborers and the learned, Jefferson recognized two levels of education ([R]: 459–60). The laborers—divided roughly into husbandmen, manufacturers, and craftsmen—needed to conduct business to sustain and improve their domestic affairs. Thus, they needed access to primary education. The learned needed access to college-level (Jefferson’s intermediary grammar schools) and university-level education. To Peter Carr (7 Sept. 1814), Jefferson writes,

It is the duty of [our country’s] functionaries, to provide that every citizen in it should receive an education proportioned to the conditions and pursuits of his life.

Needs are not all personal. People are, for Jefferson, social creatures, republics are progressive, and thus, citizens have political duties. Education is critical. “If the condition of man is to be progressively ameliorated, as we fondly hope and believe,” writes Jefferson to the French revolutionary Marc Antoine Jullien (6 Oct. 1818), “education is to be the chief instrument in effecting it.” To fit and function in a stable, thriving democracy, all citizens are expected to know and assume a participatory role to the best of their capacities.

To promote both fullest political participation and moral progress, Jefferson realized that educational reform had to be systemic. In a letter to Senator Joseph C. Cabell (9 Sept. 1817), Jefferson outlines six features of that system.

- Basic education should be available to all.

- Education should be tax-supported.

- Education should be free from religious dictation.

- The educational system should be controlled at the local level.

- The upper levels of education should feature free inquiry.

- The mentally proficient should be enabled to pursue education to the highest levels at public expense.

Only a system could offer all citizens an education proportioned to their needs: the laborers, a broad, general education; the learned, an education suited to their idiosyncratic needs (Bowers 1943: 243 and Walton 1984: 119). Jefferson gets across that point to academician George Ticknor (25 Nov. 1817) in the manner of Bacon by limning the important truths—“that knowledge is power, that knowledge is safety, and that knowledge is happiness.” That knowledge is useful, data-driven.

Overall, observation showed that human capacities were greatly underdeveloped (TJ to William Green Munford, 17 June 1799). Consequently, education needed to tap into untapped human potential in morally responsible ways.

As well might it be urged that the wild and uncultivated tree, hitherto yielding sour and bitter fruit only, can never be made to yield better; yet we know that the grafting art implants a new tree on the savage stock, producing what is most estimable both in kind and degree. Education, in like manner, engrafts a new man on the native stock, and improves what in his nature was vicious and perverse into qualities of virtue and social worth ([R]: 461).

Human perfectibility, for Jefferson, was a matter of improved efficiency of living, which implied not merely progress in the fields of human health and human productivity through discoveries and labor-saving inventions, but also and especially moral improvement. Moral improvement was much more important than exercise of rationality (e.g., TJ to Maria Cosway, 12 Oct. 1786). Pure rationality was a matter of humans abstracting from reality; moral sensibility was a matter of humans immersed in reality.

Still Jefferson thought courses in morality were unneeded, if not injurious. “I think it lost time to attend lectures in this branch,” Jefferson writes to Carr (10 Aug. 1787), for moral conduct is not a matter of reason. That of course was consistent with the empiricism of his day—e.g., Lord Kames and David Hume. Nonetheless, Jefferson in Notes on the State of Virginia has a role for education in moral development. The first stage of education is not the time to encourage critical engagement with material like the Bible, for human rationality is not sufficiently developed, but instead a time when children should store historical facts to be used critically later in life. While doing so, the “elements of morality” can be instilled. Such elements teach children, says Jefferson in Aristotelian fashion, that

their own greatest happiness … does not depend on their condition in life in which chance has placed them, but is always the result of a good conscience, good health, occupation [i.e., industry], and freedom in all just pursuits ([NV]: 147).

Moral “learning” is, thus, less a matter of ingesting and digesting moral principles to apply to circumstances—there were no inviolable principles for Jefferson, as morality was a matter of sensing the right thing to do in circumstances—but of placing faith in the capacity of one’s moral sense to “decide” the right course of action without the corruptive influence of reason or peer pressure (TJ to Martha Jefferson, 11 Dec. 1783, TJ to Peter Carr, 19 Aug. 1785 and 10 Aug. 1787).

Because of the subordination of rationality to morality, education must be useful. It must engender effective, participatory citizenry and political stability. Jefferson always insisted on the practicality of education, because his take on knowledge was Baconian. [ 33 ] Consider what Jefferson says to scientist and physician Edward Jenner (14 May 1806) on behalf of the “whole human family” for his discovery of a vaccine for small pox.

Medecine has never before produced any single improvement of such ability. Harvey’s discovery of the circulation of the blood was a beautiful addition to our knowledge of the animal economy, but on a review of the practice of medicine before & since that epoch, I do not see any great amelioration which has been derived from that discovery, you have erased from the Calendar of human afflictions one of it’s greatest. Yours is the comfortable reflection that mankind can never forget that you have lived.

Yet every scientific discovery is potentially fruitful. “No discovery is barren; it always serves as a step to something else” (TJ to Robert Patterson, 17 Apr. 1803).

“Useful” for Jefferson was broad and with normative implications. [ 34 ] A complete education for Jefferson would produce men who were

in all ways useful to society—useful because intelligent, cultured, well-informed, technically competent, moral (this particularly), capable of earning a living, happy, and fitted for political and social leadership (Martin: 37).

Useful implied socially and politically active. Male citizens of greatest virtue and greatest genius would contribute by participation in science and in the most politically prominent positions. Lesser citizens would contribute more modestly and mostly at local levels through, for illustration, jury duty, participation in militia, and voting for and overseeing elected representatives.

Finally, education for Jefferson was a way of living. Its aim was to give persons the tools they would need to make them socially and politically involved, free, self-sufficient, and happy. As Karl Lehmann (201–2) notes:

To Thomas Jefferson, school would never be a ‘finishing’ agency. From each stage, man would have to move on in a never ending process of self-education…. The narrow professional who had but a technical knowledge of his little vocational area was a curse to him. Education had to be broad in order to assure the freedom and happiness of man.

Jefferson’s views on race have been the focus of considerable discussion in the secondary literature. [ 35 ] Those views, which would be considered today as racist, were likely influenced by the views of the leading naturalists of his day. In that regard, he was the product, not ahead, of his time.

Most of the discussion of Jefferson’s views on Blacks concerns his Notes on the State of Virginia. In Query XIV, Jefferson writes, “In memory [Blacks] are equal to the whites” ([NV]: 139). “In reason,” Jefferson says, “[Blacks are] much inferior [to Whites], as I think one could scarcely be found capable of tracing and comprehending the investigations of Euclid” ([NV]: 139). He adds, “Never yet could I find that a black had uttered a thought above the level of plain narration” ([NV]: 140). “In imagination [Blacks] are dull, tasteless, and anomalous,” and that is evident in their art. In music, Blacks have accurate ears “for tune and time,” are generally more gifted than Whites, and are capable of a “small catch,” as illustrated by their talent with the “Banjar,” a guitar-like instrument “brought … from Africa.” “Whether they will be equal to the composition of a more extensive run of melody, or of complicated harmony, is yet to be proved.” Despite their misery, which “is often the parent of the most affecting touches of poetry,” they have “no poetry” ([NV]: 40–41 and 288n10).

Inferiority of mind and imagination, he adds, is also confirmed, in Jefferson’s estimation, by “the improvement of the blacks in body and mind, in the first instance of their mixture with the whites,” and that “has been observed by every one, and proves that their inferiority is not the effect merely of their condition of life” ([NV]: 141). Here he may be referencing “observations” in scientific texts of his day in his library.

In morality, Jefferson admits, Blacks are the equals of all others.

We find among them numerous instances of the most rigid integrity, and as many as among their better instructed masters, of benevolence, gratitude, and unshaken fidelity.

What he takes to be their “disposition to theft,” Jefferson explains thus: “The man, in whose favour no laws of property exist, probably feels himself less bound to respect those made in favour of others.” Might not a slave “justifiably take a little from one, who has taken all from him” ([NV]: 142).

All such conclusions, Jefferson says, are provisional: They have the confirmation of observation, but Blacks as well as “red men” hitherto have not been the subjects of natural history.

The opinion, that they are inferior in the faculties of reason and imagination, must be hazarded with great diffidence. To justify a general conclusion, requires many observations, even where the subject may be submitted to the Anatomical knife, to Optical glasses, to analysis by fire or by solvents. How much more then where it is a faculty, not a substance, we are examining; where it eludes the research of all the senses; where the conditions of its existence are various and variously combined; where the effects of those which are present or absent bid defiance to calculation; let me add too, as a circumstance of great tenderness, where our conclusion would degrade a whole race of men from the rank in the scale of beings which their Creator may perhaps have given them. To our reproach it must be said, that though for a century and a half we have had under our eyes the races of black and of red men, they have never yet been viewed by us as subjects of natural history. I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks … are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind ([NV]: 143).

Though he stated that Blacks and Native Americans had not been the subjects of natural history, there was a large body of literature by leading naturalists of his day—e.g., Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus ([1758] 1808), Oliver Goldsmith ([1774] 1823), and “Georges” Cuvier ([1817] 1831)—to which Jefferson had access and which he doubtless assimilated. That literature viewed Blacks and Native Americans as inferior to white Europeans, and the overall tendency was to associate darker skin with increased inferiority. [ 36 ] Prominent philosophers like David Hume (1755 [1987]: 208n10), Adam Smith (1759 [1982]: 208), and C.F. de Volney in (1802 [2010]: 68) also asserted the inferiority of Blacks and Native Americans.

This smattering of the “science” of Jefferson’s time shows that some of the most esteemed scientists held that Blacks and Native Americans, considering each as a race or subspecies of humans, were regarded as inferior or defective. [ 37 ] Jefferson owned and was informed by most of that literature, since he tended to be aware of recent developments in all of the sciences. Thus Jefferson’s “observations” were tainted by the “observations” or prejudgments of the authorities of his day. Despite his view of them as inferior, he recognized Blacks, as moral equals of all others, had the same rights as all other men. He writes to Bishop Grégoire (25 Feb. 1809):

Whatever be [Blacks’] degree of talent it is no measure of their rights. Because Sir Isaac Newton was superior to others in understanding, he was not therefore lord of the person or property of others.

Nonetheless, Jefferson’s view of Native Americans was inconsistent with those naturalists who viewed them too as a race inferior to Europeans, and that requires some explanation. In Query XIV of his Notes on the State of Virginia , Jefferson offers a brief analysis of Native Americans as a race. Not having had the “advantages” of exposure to European culture that Blacks have had, still Native Americans “often carve figures on their pipes not destitute of design and merit” ([NV]: 140). Their carvings and drawings “prove the existence of a germ in their minds which only wants cultivation.” [ 38 ] He continues,