- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write a Plot

I. What is Plot?

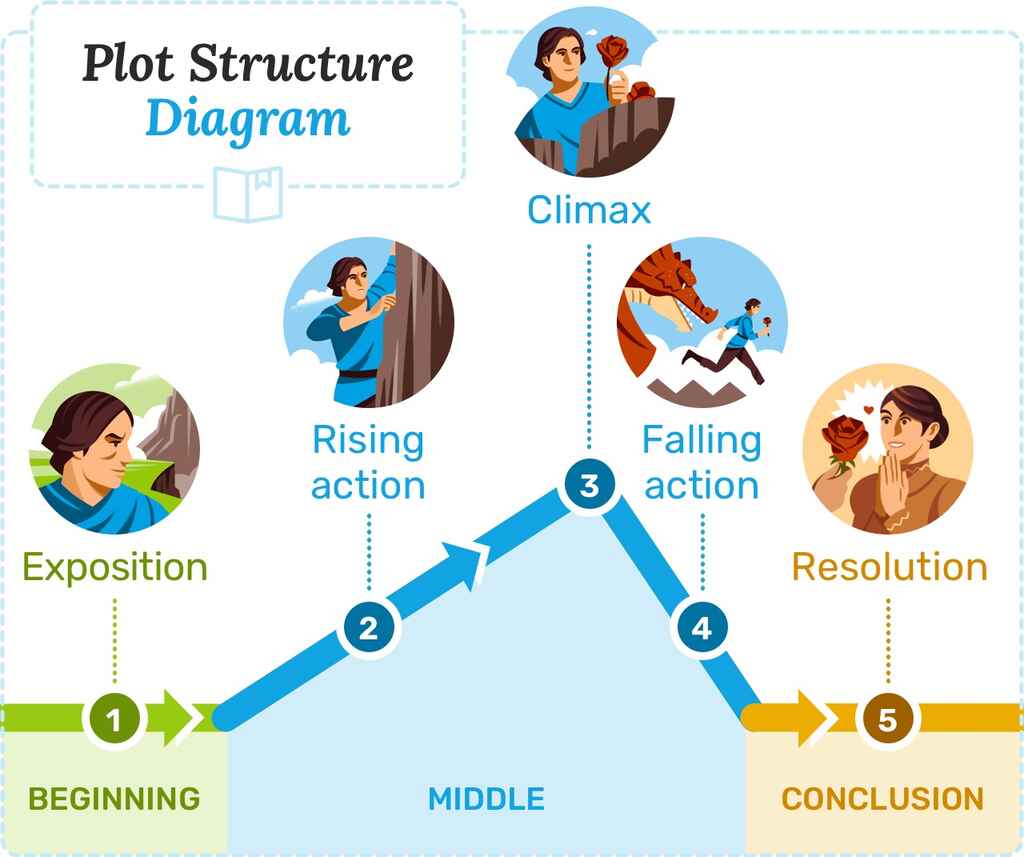

In a narrative or creative writing, a plot is the sequence of events that make up a story, whether it’s told, written, filmed, or sung. The plot is the story, and more specifically, how the story develops, unfolds, and moves in time. Plots are typically made up of five main elements:

1. Exposition: At the beginning of the story, characters , setting, and the main conflict are typically introduced.

2. Rising Action: The main character is in crisis and events leading up to facing the conflict begin to unfold. The story becomes complicated.

3. Climax: At the peak of the story, a major event occurs in which the main character faces a major enemy, fear, challenge, or other source of conflict. The most action, drama, change, and excitement occurs here.

4. Falling Action: The story begins to slow down and work towards its end, tying up loose ends.

5. Resolution/ Denoument: Also known as the denouement, the resolution is like a concluding paragraph that resolves any remaining issues and ends the story.

Plots, also known as storylines, include the most significant events of the story and how the characters and their problems change over time.

II. Examples of Plot

Here are a few very short stories with sample plots:

Kaitlin wants to buy a puppy. She goes to the pound and begins looking through the cages for her future pet. At the end of the hallway, she sees a small, sweet brown dog with a white spot on its nose. At that instant, she knows she wants to adopt him. After he receives shots and a medical check, she and the dog, Berkley, go home together.

In this example, the exposition introduces us to Kaitlin and her conflict. She wants a puppy but does not have one. The rising action occurs as she enters the pound and begins looking. The climax is when she sees the dog of her dreams and decides to adopt him. The falling action consists of a quick medical check before the resolution, or ending, when Kaitlin and Berkley happily head home.

Scott wants to be on the football team, but he’s worried he won’t make the team. He spends weeks working out as hard as possible, preparing for try outs. At try outs, he amazes coaches with his skill as a quarterback. They ask him to be their starting quarterback that year and give him a jersey. Scott leaves the field, ecstatic!

The exposition introduces Scott and his conflict: he wants to be on the team but he doubts his ability to make it. The rising action consists of his training and tryout; the climax occurs when the coaches tell him he’s been chosen to be quarterback. The falling action is when Scott takes a jersey and the resolution is him leaving the try-outs as a new, happy quarterback.

Each of these stories has

- an exposition as characters and conflicts are introduced

- a rising action which brings the character to the climax as conflicts are developed and faced, and

- a falling action and resolution as the story concludes.

III. Types of Plot

There are many types of plots in the world! But, realistically, most of them fit some pattern that we can see in more than one story. Here are some classic plots that can be seen in numerous stories all over the world and throughout history.

a. Overcoming the Monster

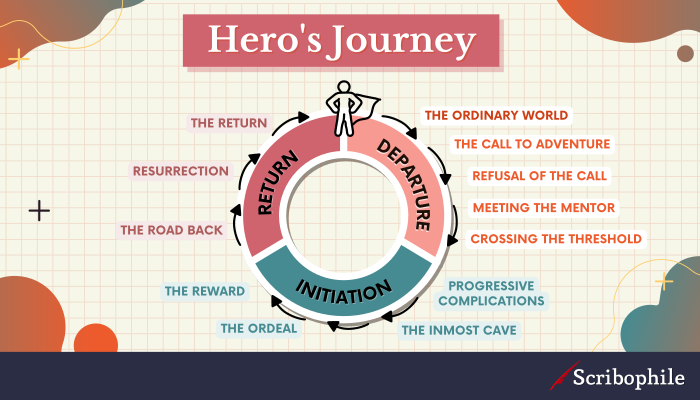

The protagonist must defeat a monster or force in order to save some people—usually everybody! Most often, the protagonist is forced into this conflict, and comes out of it as a hero, or even a king. This is one version of the world’s most universal and compelling plot—the ‘monomyth’ described by the great thinker Joseph Campbell.

Examples:

Beowulf, Harry Potter, and Star Wars.

b. Rags to Riches:

This story can begin with the protagonist being poor or rich, but at some point, the protagonist will have everything, lose everything, and then gain it all back by the end of the story, after experiencing great personal growth.

The Count of Monte Cristo, Cinderella, and Jane Eyre.

c. The Quest:

The protagonist embarks on a quest involving travel and dangerous adventures in order to find treasure or solve a huge problem. Usually, the protagonist is forced to begin the quest but makes friends that help face the many tests and obstacles along the way. This is also a version of Campbell’s monomyth.

The Iliad, The Lord of the Rings, and Eragon

d. Voyage and Return:

The protagonist goes on a journey to a strange or unknown place, facing danger and adventures along the way, returning home with experience and understanding. This is also a version of the monomyth.

Alice in Wonderland, The Chronicles of Narnia, and The Wizard of Oz

A happy and fun character finds a happy ending after triumphing over difficulties and adversities.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Fantastic Mr. Fox, Home Alone

f. Tragedy:

The protagonist experiences a conflict which leads to very bad ending, typically death.

Romeo and Juliet, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and Macbeth

g. Rebirth:

The protagonist is a villain who becomes a good person through the experience of the story’s conflict.

The Secret Garden, A Christmas Carol, The Grinch

As these seven examples show, many stories follow a common pattern. In fact, according to many thinkers, such as the great novelist Kurt Vonnegut, and Joseph Campbell, there are only a few basic patterns, which are mixed and combined to form all stories.

IV. The Importance of Using Plot

The plot is what makes a story a story. It gives the story character development, suspense, energy, and emotional release (also known as ‘catharsis’). It allows an author to develop themes and most importantly, conflict that makes a story emotionally engaging; everybody knows how hard it is to stop watching a movie before the conflict is resolved.

V. Examples of Plot in Literature

Plots can be found in all kinds of fiction. Here are a few examples.

The Razor’s Edge by Somerset Maugham

In The Razor’s Edge, Larry Darrell returns from World War I disillusioned. His fiancée, friends, and family urge him to find work, but he does not want to. He embarks on a voyage through Europe and Asia seeking higher truth. Finally, in Asia, he finds a more meaningful way of life.

In this novel, the plot follows the protagonist Larry as he seeks meaningful experiences. The story begins with the exposition of a disillusioned young man who does not want to work. The rising action occurs as he travels seeking an education. The story climaxes when he becomes a man perfectly at peace in meditation.

The Road not Taken’ by Robert Frost

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, And sorry I could not travel both And be one traveler, long I stood And looked down one as far as I could … Then took the other, as just as fair, And having perhaps the better claim … And both that morning equally lay In leaves no step had trodden black. … I shall be telling this with a sigh Somewhere ages and ages hence: Two roads diverged in a wood, and I, I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference.

Robert Frost’s famous poem “The Road Not Taken,” has a very clear plot: The exposition occurs when a man stands at the fork of two roads, his conflict being which road to take. The climax occurs when he chooses the unique path. The resolution announces that “that has made all the difference,” meaning the man has made a significant and meaningful decision.

VI. Examples of Plot in Pop Culture

Plots can also be found in television shows, movies, thoughtful storytelling advertisements, and song lyrics. Below are a few examples of plot in pop culture.

“Love Story” (excerpts) by Taylor Swift:

I’m standing there on a balcony in summer air. See the lights, see the party, the ball gowns. See you make your way through the crowd And say, “Hello, ” Little did I know… That you were Romeo, you were throwing pebbles, And my daddy said, “Stay away from Juliet” And I was crying on the staircase Begging you, “Please don’t go” So I sneak out to the garden to see you. We keep quiet ’cause we’re dead if they knew So close your eyes… escape this town for a little while. . . . He knelts to the ground and pulled out a ring and said… “Marry me, Juliet, you’ll never have to be alone. I love you, and that’s all I really know. I talked to your dad – go pick out a white dress It’s a love story, baby, just say, ‘Yes.'”

These excerpts reveal the plot of this song: the exposition occurs when we see two characters: a young woman and young man falling in love. The rising action occurs as the father forbids her from seeing the man and they continue see one another in secret. Finally, the climax occurs when the young man asks her to marry him and the two agree to make their love story come true.

Minions have a goal to serve the most despicable master. Their rising action is their search for the best leader, the conflict being that they cannot keep one. Movie trailers encourage viewers to see the movie by showing the conflict but not the climax or resolution.

VII. Related Terms

Many people use outlines which to create complex plots, or arguments in formal essays . In a story, an outline is a list of the scenes in the plot with brief descriptions. Like the skeleton is to the body, an outline is the framework upon which the rest of the story is built when it is written. In essays, outlines are used to help organize ideas into strong arguments and paragraphs that connect to each other in sensible ways.

The climax is considered the most important element of the plot. It contains the highest point of tension, drama, and change. The climax is when the conflict is finally faced and overcome. Without a climax, a plot does not exist.

For example, consider this simple plot:

The good army is about to face the evil army in a terrible battle. During this battle, the good army prevails and wins the war at last. After the war has ended, the two sides make piece and begin rebuilding the countryside which was ruined by the years-long war.

The climax occurred when the good army defeated the bad army. Without this climax, the story would simply be a never-ending war between a good army and bad army, with no happy or sad ending in sight. Here, the climax is absolutely necessary for a meaningful story with a clear ending.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

- Book Writing

What is a Plot? Definition, Examples & Writing Tips

- By Yves Lummer

Wondering about the plot definition and its role in the realm of storytelling? You’ve come to the right place! In this article, we’ll explore the plot as a crucial element of storytelling fundamentals , helping writers and readers alike to appreciate and understand narrative components and story structure .

Whether you’re a novice writer or a seasoned author, it’s essential to sharpen your skills in constructing engaging and memorable plots. Unravel the secrets of captivating storytelling as we delve into plot examples and expert writing tips that will give your narratives that extra punch. Ready to embark on this narrative journey? Let’s get started!

What is a Plot?

A plot serves as the backbone of any narrative, guiding readers through a structured series of events that encompass key turning points and dictate the storyline . Understanding plot is crucial for both budding writers and avid readers, as it goes beyond mere events to create a compelling narrative filled with growth, change, and resolution. In this section, we will explore the comprehensive definition of plot, its significance in developing a coherent and gripping tale, and delve into how it encompasses various narrative elements like character development and story arc .

At its core, a plot transforms a series of incidents into a coherent narrative by connecting these events through a clear narrative structure . This structure consists of a coherent organization of events and character reactions that reveal a larger pattern and carries the reader on a satisfying emotional journey. A plot’s narrative structure often includes the initial setup, the introduction of a challenge or conflict, a series of complications, a climax, and a resolution. These are the foundational building blocks that shape the storyline .

Equally important, the plot facilitates character development , as it provides the context in which characters face challenges, make choices, and grow throughout the story. A well-structured plot can unveil the complexities of protagonists, antagonists, and supporting characters, revealing their motivations, beliefs, strengths, and weaknesses as they navigate their unique circumstances.

Furthermore, the plot is responsible for defining the overarching story arc , which covers the entire narrative from beginning to end. The story arc typically showcases the progression of the main character from their initial state to their fully developed one, as well as how their world has transformed by the end of the tale.

“A plot is not a series of disconnected events, but a sequence of interconnected incidents that together tell a story.”

In conclusion, a plot is the backbone of a narrative, offering a structured sequence of events, character development opportunities, and an engaging story arc that can truly captivate readers. By understanding the importance of plot and its various components, you can work towards crafting stories that leave a lasting impact on your audience.

Why is a Plot Important?

A well-crafted plot is indispensable to effective storytelling. It has the power to captivate an audience and sustain their interest till the end, setting the stage for story engagement and providing a solid foundation for creating engaging narratives . In this section, we’ll explore the storytelling importance of a cohesive plot and how it significantly impacts the overall reading experience.

The plot isn’t just a random assortment of occurrences; it’s what gives a story its meaning and emotional impact.

A compelling plot weaves together the characters’ journeys, their development, and the ultimate resolution, serving as a vehicle for the themes and messages the writer wishes to convey. It is the glue that binds all narrative components , driving the story forward and providing direction.

- Consistent Structure: A well-developed plot fosters continuity and coherence throughout the story, enhancing readability and ensuring important elements don’t fall by the wayside.

- Character Development: A strong plot facilitates the growth and development of characters, allowing readers to empathize, understand, and relate to their experiences.

- Pacing and Suspense: One of the most important factors in maintaining reader interest is pacing. A well-structured plot governs pacing and tension, striking a balance between action-packed scenes and moments of introspection or respite.

- Theme Establishment: A cohesive plot allows writers to convey their underlying themes and messages effectively, providing a framework for exploring topical issues and delivering meaningful insights.

In conclusion, an engaging plot is crucial in delivering a captivating and fulfilling reading experience. Its plot significance lies in its ability to seamlessly join the various components of a story, resulting in a powerful emotional impact and resonating with readers long after they’ve turned the last page. As writers, it’s essential to recognize the importance of plot and strive to showcase its full potential in our storytelling endeavors.

Story vs. Plot: What’s the Difference?

Novice writers often confuse the terms “story” and “plot,” even though they represent different storytelling elements . Both are crucial aspects of a narrative; however, each fulfills a unique role in shaping and forming the final output. In this section, we will discuss the key differences between a story and a plot , and how understanding these concepts will enable writers to create more compelling and engaging narratives .

A story refers to the raw chronology and sequence of events in a narrative. It encompasses the primary actions of the protagonists, the setting, and the relevant factors that constitute the overall tale. On the other hand, plot comprises those same events, strategically and deliberately arranged to deliver an enticing and emotionally impactful journey.

To better understand these concepts, let’s examine the key narrative differences and components that distinguish a story from a plot.

- Chronology vs. Structure: While a story follows a chronological order of events, a plot weaves those events in a purposeful manner to enhance the emotional effect and maintain the reader’s curiosity.

- Events vs. Relevance: A story consists of all events that take place, whereas a plot highlights only the relevant events that contribute to dramatic tension and character development , omitting unnecessary details.

- Fact vs. Art: Storytelling is the presentation of facts, while plotting is the art of assembling and organizing those facts in a way that maximizes interest and emotional response from the audience.

“The king died and then the queen died is a story. The king died, and then the queen died of grief is a plot.” – E. M. Forster

By distinguishing between story and plot, writers can harness the narrative differences and strike a balance between raw events and controlled structure. This helps in constructing a compelling narrative that effectively connects with readers on an emotional level.

In conclusion, recognizing the nuances between story and plot is essential for writers to create captivating narratives. By mastering the art of arranging events in a meaningful and engaging manner, you’ll reach new heights in your storytelling endeavors.

Elements of a Plot Structure

Mastering the traditional five-part plot structure is fundamental to crafting compelling narratives. Each element, from exposition to denouement, plays a critical role in setting up the story, building suspense, climactic moments, winding down tensions, and providing closure. In this section, you will discover the purpose of each plot element and how they collectively serve to engage the reader and deliver a satisfying story experience.

The exposition is the opening part of a story where the literary structure is introduced. It sets the stage for the rest of the narrative by providing essential information on the characters, the setting, and the primary conflict. The exposition aims to establish the story’s foundation, giving the reader a grasp of the characters’ motivations and the world they inhabit.

- Rising Action

As the story proceeds, the rising action forms the majority of the story framework . In this phase, the main conflict develops and intensifies, with smaller conflicts and complications arising along the way. The tension builds, drawing the reader deeper into the narrative while showcasing the characters’ growth and setting the stage for the story’s climax.

The climax is the pivotal moment in the narrative blueprint when the tension peaks. Often referred to as the “turning point,” the climax presents the protagonist with a major challenge or decision. This critical phase showcases a key character’s emotional high point, either physical or internal, in a confrontation that could alter the story’s course.

- Falling Action

Following the climax, the falling action deals with the consequences and aftermath of the critical moment. Tension begins to subside as characters come to terms with what happened during the climax, and the story heads towards resolution. While the intensity decreases, the falling action serves to wrap up loose ends and set the stage for the denouement.

The final piece of the plot elements puzzle is the denouement . It provides closure for the characters and the story as a whole. The denouement may bring together different storylines, reveal the fates of the characters, and tie up any remaining loose ends. It leaves the reader with a sense of completion and satisfaction, knowing that the narrative has reached its conclusion.

Examples of Plot

Plots can take various forms, with many following time-honored archetypes that resonate with audiences across cultures and historical contexts. In this section, we will discuss some of the most enduring classic plot types , including The Quest, Rags to Riches, Overcoming the Monster, The Voyage and Return, and The Tragedy. By understanding these universal storylines and narrative archetypes , you can draw inspiration for your own stories or recognize these patterns in works you’re reading.

One of the most iconic plot examples , The Quest narrative, follows the protagonist’s journey to accomplish a specific goal or objective. Often, this goal requires the character to overcome numerous obstacles and challenges. The Lord of the Rings trilogy is an excellent example of The Quest plot archetype, featuring a group of characters on a journey to destroy the One Ring.

Rags to Riches

The Rags to Riches plot centers on a protagonist who begins in a lowly state and, through hard work, determination, or a series of fortunate events, rises to greatness. Cinderella is a classic example of this narrative archetype, telling the story of a young woman who, despite her humble beginnings, ascends to royalty.

Overcoming the Monster

In the Overcoming the Monster plot, the central conflict revolves around the protagonist battling a great evil or antagonistic force, often on behalf of others or their society. In many cases, the “monster” can be a literal creature, but it can also represent evil organizations, oppressive systems, or personal fears. The Harry Potter series is a prime example of this plot type, detailing the struggle between Harry Potter and the dark wizard, Voldemort.

The Voyage and Return

The Voyage and Return narrative follows the protagonist as they embark on a journey to an unfamiliar world, where they experience various trials before returning home, often transformed or enlightened by their experiences. This plot archetype is prominent in works such as The Chronicles of Narnia and The Wizard of Oz, where the protagonists traverse magical lands before returning to their own reality.

The Tragedy

Finally, The Tragedy plot concerns stories marked by personal downfall or loss, often resulting from a character’s own flawed choices, circumstances, or fate. One of the most well-known examples of this plot type is Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, a story of star-crossed lovers whose tragic deaths are the result of unlucky events and personal misjudgments.

By understanding these classic plot types and their respective examples, you can gain inspiration for your writing and develop a keen analytical eye when recognizing these patterns in literature and cinema.

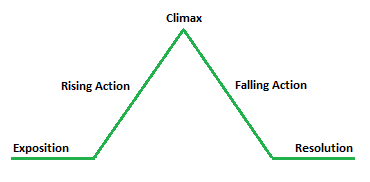

What Is a Plot Diagram?

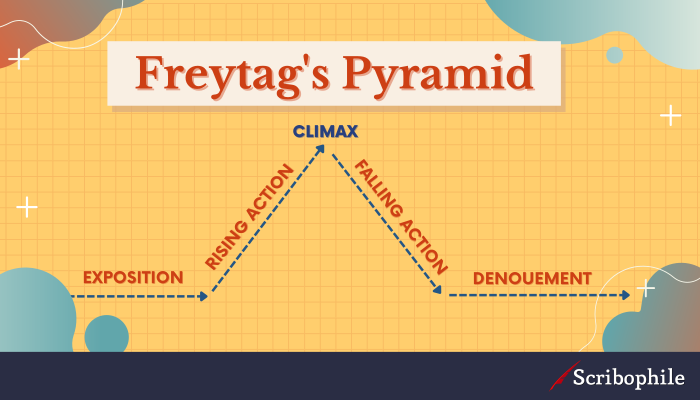

A plot diagram is a valuable visualization tool that helps writers outline and organize the key components of their narrative structure . This handy instrument aids in comprehending and mapping out the exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. In turn, it serves as a guide for balancing pacing and tension throughout a story. Popular frameworks like Freytag’s Pyramid play a pivotal role in crafting well-structured plots.

As a story outline tool , plot diagrams offer writers a visual representation of their narrative’s progression, depicting it as a chart or graph. They typically showcase transitions, subplots, and turning points – all essential elements that contribute to developing an engaging story.

A plot diagram challenges writers to focus on crucial story elements, ensuring a satisfying balance between character development and dramatic tension. – Gustav Freytag

One widely recognized plot chart , known as Freytag’s Pyramid , was developed by German playwright Gustav Freytag in the 19th century. It is based on the classical dramatic structure used in Greek and Roman plays, which involves five key stages. Freytag’s model represents the five stages (as listed below) as a series of steps or divisions, forming a pyramid shape:

- Resolution (Denouement)

Each part of the pyramid corresponds with a specific part of the narrative, denoting how the plot should unfold from the initial background information to the ultimate resolution. The table below exemplifies each stage and its role in the story:

By thoroughly understanding the components of a plot diagram and leveraging tools like Freytag’s Pyramid , you can create well-structured and engaging stories that successfully captivate your readers.

How to Plot a Story

Plotting a story can seem daunting, but by following these straightforward steps, you’ll be crafting a captivating narrative with ease. With techniques such as character development, thematic exploration, and subplot integration , you’ll create a solid foundation on which to build your story.

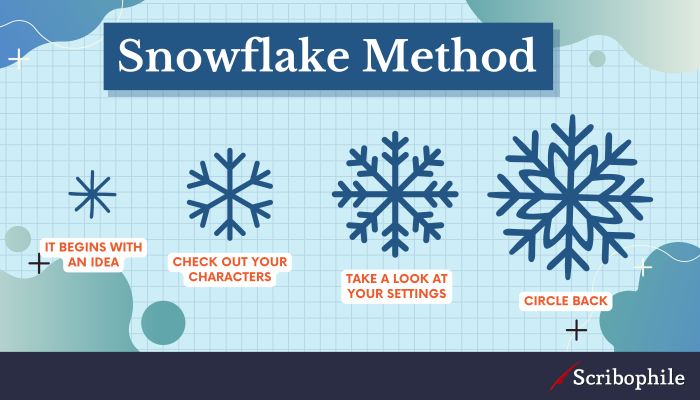

Identify the Central Idea or Theme

Begin by determining the core concept or message you wish to convey. This will serve as the guiding principle for your story, and aid in crafting a narrative that effectively expresses your intended theme.

Create Compelling Characters

Develop interesting, relatable characters that evolve throughout the story. Focus on their motivations, desires, and flaws, as these will help create engaging character arcs to keep readers invested in their journeys.

Establish the Setting

Choose a setting that complements your theme and characters, immersing readers in a world that enhances the story. Pay attention to the environment, culture, and time period, as these can significantly impact the plot and character development.

Outline the Plot Structure

Sketch the story’s plot structure, including the exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. Develop a cohesive series of events that logically progress, captivate your audience, and support your theme.

Plan Key Events

Outline the major events and turning points in your story. These pivotal moments help drive the plot forward, compelling readers to follow the character’s journey and anticipate the climax and resolution.

Develop Subplots

Integrate subplots to enrich your story’s depth and complexity. Ensuring they complement the main plot, subplots add variety, enhance character development, and help create a multi-layered narrative.

Consider the Narrative Arc

Reflect on the overall trajectory of your story, identifying how it progresses from beginning to end. Visualize how your characters evolve and the pacing of the narrative, ensuring it maintains reader interest and delivers a satisfying conclusion.

Build Tension and Pacing

Strategically design the story’s pacing and tension to evoke emotions and keep readers engaged. Be mindful of dramatic moments, action sequences, and quiet scenes, as proper balance is critical to maintaining interest.

Foreshadowing

Master the art of foreshadowing by planting subtle hints throughout your story, creating anticipation and suspense. When used effectively, this technique helps maintain reader fascination and sets the stage for impactful revelations.

By following these steps, you’ll be well-equipped to produce a gripping, well-plotted story that will resonate with your audience and leave them eager for more.

What is the difference between a story and a plot?

A story refers to the raw sequence of events as they happen chronologically, while a plot is the structure of those events deliberately arranged to maximize interest and emotional impact.

What are the five elements of a traditional plot structure?

The five elements of a traditional plot structure are Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and Denouement.

Can you provide some examples of classic plot types?

Examples of classic plot types include The Quest, Rags to Riches, Overcoming the Monster, The Voyage and Return, and The Tragedy.

What is a plot diagram and how is it helpful for writers?

A plot diagram is a visualization tool that helps writers outline and organize the key components of their narrative structure . It helps map out the exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, and serves as a guide for balancing pacing and tension throughout a story.

What are some essential steps to plot a story effectively?

To plot a story effectively, you should identify the central idea or theme, create compelling characters, establish the setting, outline the plot structure, plan key events, develop subplots, consider the narrative arc, and utilize techniques for building tension and pacing like foreshadowing.

Want To Sell More Books?

Get exclusive access to book marketing secrets, proven strategies, and powerful tools for your self-publishing journey.

Related Posts

What Is Exposition In a Story? Definition, Examples & Writing Tips

How To Write A Book Press Release

Extended Metaphor: Definition, Structure & Examples

Unabridged vs. Abridged Audiobooks: What’s the Difference?

How to Write a Mystery: 11 Secret Steps

What is an Appendix Page in a Book? Definition & Examples

© 2023 - 2024 StorySurfer All rights reserved.

Definition of Plot

Plot is a literary device that writers use to structure what happens in a story . However, there is more to this device than combining a sequence of events. Plots must present an event, action, or turning point that creates conflict or raises a dramatic question, leading to subsequent events that are connected to each other as a means of “answering” the dramatic question and conflict. The arc of a story’s plot features a causal relationship between a beginning, middle, and end in which the conflict is built to a climax and resolved in conclusion .

For example, A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens features one of the most well-known and satisfying plots of English literature.

I will honour Christmas in my heart, and try to keep it all the year. I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me. I will not shut out the lessons that they teach.

Dickens introduces the protagonist , Ebenezer Scrooge, who is problematic in his lack of generosity and participation in humanity–especially during the Christmas season. This conflict results in three visitations by spirits that help Scrooge’s character and the reader understand the causes for the conflict. The climax occurs as Scrooge’s dismal future is foretold. The above passage reflects the second chance given to Scrooge as a means of changing his future as well as his present life. As the plot of Dickens’s story ends, the reader finds resolution in Scrooge’s changed attitude and behavior. However, if any of the causal events were removed from this plot, the story would be far less valuable and effective.

Common Examples of Plot Types

In general, the plot of a literary work is determined by the kind of story the writer intends to tell. Some elements that influence the plot are genre , setting , characters, dramatic situation, theme , etc. However, there are seven basic, common examples of plot types:

- Tragedy : In a tragic story, the protagonist typically experiences suffering and a downfall, The plot of the tragedy almost always includes a reversal of fortune, from good to bad or happy to sad.

- Comedy : In a comedic story, the ending is generally not tragic. Though characters in comic plots may be flawed, their outcomes are not usually painful or destructive.

- Journey of the Hero : In general, the plot of a hero’s journey features two elements: recognition and a situation reversal. Typically, something happens from the outside to inspire the hero, bringing about recognition and realization. Then, the hero undertakes a quest to solve or reverse the situation.

- Rebirth : This plot type generally features a character’s transformation from bad to good. Typically, the protagonist carries their tragic past with them which results in negative views of life and poor behavior. The transformation occurs when events in the story help them see a better worldview.

- Rags-to-Riches : In this common plot type, the protagonist begins in an impoverished, downtrodden, or struggling state. Then, story events take place (magical or realistic) that lead to the protagonist’s success and usually a happy ending.

- Good versus Evil : This plot type features a generally “good” protagonist that fights a typically “evil” antagonist . However, both the protagonist and antagonist can be groups of characters rather than simply individuals, all with the same goal or mission.

- Voyage/Return : In this plot type, the main character goes from point A to point B and back to point A. In general, the protagonist sets off on a journey and returns to the start of their voyage, having gained wisdom and/or experience.

Aristotle’s Plot Structure Formula

Though this principle may seem obvious to modern readers, in his work Poetics , Aristotle first developed the formula for plot structure as three parts: beginning, middle, and end. Each of these parts is purposeful, integral, and challenging for writers. It

can be difficult for writers to create an effective plot device in terms of making decisions about how a story begins, what happens in the middle, and how it ends. Here is a further explanation of Aristotle’s plot structure formula:

- Beginning : The beginning of a story holds great value. It has to capture the reader’s attention, introduce the characters, setting, and the central conflict.

- Middle : The middle of a plot requires movement toward the conclusion of the story, as well as plot points, obstacles, or various subplots along the way to maintain the reader’s interest and infuse value and meaning into the story.

- End : The end of a story brings about the conclusion and resolution of the conflict, generally leaving the reader with a sense of satisfaction, value, and deeper understanding.

Freytag’s Pyramid

In 1863, Gustav Freytag (a German novelist) published a book that expanded Aristotle’s concept of plot. Freytag added two components: rising action and falling action . This dramatic arc of plot structure, termed Freytag’s Pyramid, is the most prevalent depiction of plot as a literary device. Here are the elements of Freytag’s Pyramid:

- Exposition : the beginning of the story, in which the writer establishes or introduces pertinent information such as setting, characters, dramatic situation, etc.

- Rising Action : increased tension as a result of the central conflict.

- Climax (middle) : pinnacle and/or turning point of the plot.

- Falling Action : also referred to as denouement , begins with consequences resulting from the climax and moves towards the conclusion.

- Resolution : end of the story.

Differences Between Narrative and Plot

Plot and narrative are both literary devices that are often used interchangeably. However, there is a distinction between them when it comes to storytelling. Plot involves causality and a connected series of events that make up a story. Plot refers to what actions and/or events take place in a story and the causal relationship between them.

Narrative encompasses aspects of a story that include choices by the writer as to how the story is told, such as point of view , verb tense, tone , and voice . Therefore, the plot is a more objective literary device in terms of a story’s definitive events. Narrative is more subjective as a literary device in that there are many choices a writer can make as to how the same plot is told and revealed to the reader.

Three Basic Patterns of Plot – William Foster-Harris

In his book, The Basic Patterns of Plot, Foster-Harris presented three types of plot.

- Happy Ending Plot: These plots end on a happy note when the central character makes a sacrifice or resolves the conflict. Also, there is a positive and light-hearted ending to the story.

- Unhappy Ending: In this type of plot, the central character acts logically that seems right and fails to completely resolve the conflict. The story also might end with conflict resolution but one or more characters lose something or sacrifice something.

- Tragedy : This type of plot poses questions by the end about the sadness and its reason as the central character does not make a choice for a sacrifice, or otherwise.

Master Plots – Ronald R. Tobias

The term master plots occur in the book of Ronald R. Tobias, 20 Master Plots . Some of the important ones are Quest, Adventure , Pursuit, and Rescue. These are followed by Escape, Revenge, The riddle , Rivalry, and Underdog, while Temptation, Metamorphosis, and Transformation follow them. Some others are Maturing, Love, and Forbidden Love. Sacrifice and Discovery are two other master plots with Wretched Excess, Ascension, and Descension following them. The important feature of these plots is that they all follow the style their title suggests.

Seven Types of Plots – Jessamyn West

Besides thematic plots, Jessamyn West, a volunteer librarian has listed seven basic and major plots for a story. His argument seems based on the type of characters.

- A woman against nature

- A woman against another woman, or a man against another man

- A woman against the environment or vice versa

- A woman against technology

- A woman against self

- A woman against supernatural elements

- A woman against religion or gods

Why it is Good to Break Traditional Plot Structures

Although most critics are very strict about a story having a plot, it is quite unusual to break the conventional structures and create a new one. This creativity is the hallmarks of a literary piece as breaking the traditional plot structure makes the literary piece in the process a unique addition to the long list of such other pieces. This also makes the writer flout new ideas about plot structures, making him a pioneer in such plots. It often happens in postmodern fiction to break away from traditions in creating plots such as Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut presents a non-linear storyline.

Linear and Non-Linear Plots

These two very simple terms, linear and non-linear in the literary world with reference to plots, define how a plot has been structured. A linear plot is constructed on the idea of chronological order having a clear beginning, a defined middle, and a definite ending. However, when an author, such as the referred novel in the above example shows, breaks away from the normal plot structures, it becomes a non-linear plot. It does not have any beginning or for that matter any ending or middle. It just presents fractured and broken thoughts or incidents in a way that the readers have to construct their own story.

Examples of Plot in Literature

When readers remember a work of literature, whether it’s a novel, short story , play , or narrative poem , their lasting impression often is due to the plot. The cause and effect of events in a plot are the foundation of storytelling, as is the natural arc of a story’s beginning, middle, and end. Literary plots resonate with readers as entertainment, education, and elemental to the act of reading itself. Here are some examples of plot in literature:

Example 1: Romeo and Juliet (Prologue) – William Shakespeare

Two households, both alike in dignity (In fair Verona, where we lay our scene), From ancient grudge break to new mutiny, Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean. From forth the fatal loins of these two foes A pair of star-crossed lovers take their life; Whose misadventured piteous overthrows Doth with their death bury their parents’ strife. The fearful passage of their death-marked love And the continuance of their parents’ rage, Which, but their children’s end, naught could remove, Is now the two hours’ traffic of our stage; The which, if you with patient ears attend, What here shall miss, our toil shall strive to mend.

In the prologue of Shakespeare’s famous tragedy, the arc of the plot is told–including the outcome of the story. However, though the overall plot is revealed before the story begins, this does not detract from the portrayal of the events in the story and the relationship between their cause and effect. Each character’s action drives forward connected events that build to a climax and then a tragic resolution, so that even if the reader/viewer knows what will happen, the play remains an engaging and memorable literary work.

Example 2: Six-word-long story, often attributed to Ernest Hemingway

For sale, baby shoes, never worn.

This famous six-word short story is attributed to Ernest Hemingway , although there has been no indisputable substantiation that it is his creation. Aside from its authorship, this story demonstrates the power of plot as a literary device and in particular the effectiveness of Aristotle’s formula. Through just six words, the plot of this story has a beginning, middle, and end that readers can identify. In addition, the plot allows readers to interpret the causality of the story’s events depending on the manner in which they view and interpret the narrative.

Example 3: Don Quixote – Miguel de Cervantes

“Destiny guides our fortunes more favorably than we could have expected. Look there, Sancho Panza, my friend , and see those thirty or so wild giants, with whom I intend to do battle and kill each and all of them, so with their stolen booty we can begin to enrich ourselves. This is noble, righteous warfare, for it is wonderfully useful to God to have such an evil race wiped from the face of the earth.” “What giants?” Asked Sancho Panza. “The ones you can see over there,” answered his master, “with the huge arms, some of which are very nearly two leagues long.” “Now look, your grace,” said Sancho, “what you see over there aren’t giants, but windmills, and what seems to be arms are just their sails, that go around in the wind and turn the millstone.” “Obviously,” replied Don Quijote, “you don’t know much about adventures.”

Don Quixote is considered the first modern novel, and the complexity of its plot is one of the reasons for this distinction. Each event that takes place in this overall hero’s journey is connected to and causes other actions in the story, bringing about a resolution at the end. This novel by de Cervantes features subplots as well, yet the story arc of the character reflects all elements of both Aristotle’s plot formula and Freytag’s Pyramid.

Synonyms of Plot

There are several synonyms that come close to the plot in meanings such as narrative, theme, events, tales, mythos, and subject , yet they are all literary devices in their own right. They do not replace the plot.

Related posts:

Post navigation.

The Art of Narrative

Learn to write.

What is Plot? A Writer’s Guide to Creating Amazing Plots

What’s plot? Discover the definition of plot, different types of plots, the various elements of a great plot including Vonnegut’s story shapes!

People are always stopping me on the street and asking, “What is plot? You look like a part-time writer, you should know!” I’m kidding. That never happens. But, if you came here for the basic definition for the plot, we’ve got that for you plus a lot more!

The Definition of Plot

In fiction, a plot is the cause and effect sequence of significant events that make up the story’s narrative. These events can include things like an inciting incident, mid-plot point, climax, and resolution.

But there is so much more to plot than this boring definition. So, today we are going to talk about what plot is all about. Let’s take a deep drive on plot and figure out how to use it for our own stories! We’ll start with types of plot.

Different types of plot

If you google “different types of plot” one of the first hits you’ll get is something like, “the 1,500 basic types of plot!” Needles to say, the subject of plot types can be confusing, and the truth is your plot is what you make it. You don’t have to conform to anyone’s pattern. But, if you help getting started there are plenty of plots diagrams you can use. For this post, we’ll cover the most beneficial ones.

Kurt Vonnegut’s Shape of Stories

A terrific source for outlining different plot types is the Shapes of Stories by famed writer Kurt Vonnegut. In case you’re not familiar, Vonnegut is the author of titles like Slaughterhouse-Five, and Breakfast of Champions. He also wrote a thesis, Shapes of Stories, arguing there were eight basic plot shapes that you could draw on a graph. He describes these story shapes as eight common character arcs.

Below is a short lecture Vonnegut gave on the concept:

The Eight Shapes of Stories

Man in a Hole:

With this plot your main character will get into some serious trouble. This trouble will upend your protagonist’s life and send them spiraling towards rock bottom. Through the plot of your story, the character will make their way out of trouble. By the conclusion the protagonist will be left off better than where they started, having crawled out of the hole.

The hole is usually metaphorical, but by all means, stick your character in a real hole if you want.

Boy Meets Girl :

Or girl meets boy. Like the hole from the example above, the person your character meets can be symbolic. Your character doesn’t have to meet a person; they can find something wonderful or life-changing. The character will experience the awesome benefits of this thing or person they found. Then, as it often does, tragedy strikes.

At some point in the story, your character will lose the wonderful thing they found, and they will become deeply depressed. We’re back in the hole. However, by the story’s conclusion the character will regain the thing they lost. What’s more, they will get it back permanently, and, like with Man in a Hole, they will end better than they started.

From Bad to Worse :

Are you a sadist? Well, do I have the plot for you! From Bad to Worse character arcs are exactly what they sound like. You start your character off in a terrible situation. Then things get gradually worse for them as the story progresses. By the end, your protagonist has lost all hope of things ever getting better. Because they won’t.

This kind of arc makes great horror stories. They also put your readers through the wringer.

Which Way is Up?

Life imitates art in the Which Way is Up story arc. Things are confusing; events are ambiguous. It’s difficult to tell whether a turn of fate will benefit or harm your protagonist. These stories hit close to home, as with a reader’s life, we’re not guaranteed a happy ending.

Great for thrillers and mysteries, this kind of story will keep readers on the edge of their seat.

Creation Story :

In the beginning, there was light! Creation stories follow the pattern of a deity creating all of existence. God or some other deity will create humankind and then bestow gifts on them gradually, one at a time.

One day you get a garden, then the next you get some animal friends. Later, you might get a spouse. These are pretty common stories to all cultures as they helped people describe the mystery of life. They’re not quite as popular in modern culture, but maybe you’ll be the one to revive them.

Old Testament :

If you were to say you were going “old testament” on someone, that person is probably in for a bad time. Because let’s face it, the Old Testament isn’t the most cheery tome. Whether it’s Lot’s wife, or Abel, or the “OGs,” Adam and Eve, there’s a lot of fire and brimstone raining down on people.

Old Testament stories build on the Creation story arc. A deity gradually rewards humankind. However, at some point humans suffer a sudden and drastic fall from grace. So, how would you update this story for a modern audience? Shrink it a little.

You don’t have to write about all of humankind. Focus your story on one character- your protagonist. They are blessed by the gods, or society, or just parents with a fat bank account, but they lose it all. Slowly, your hero will have to earn their way back into the garden.

New Testament :

New Testament stories follow the same track as their Old Testament counterparts, but humankind, or your hero, will overcome their fall from grace. Your hero is bestowed gradual gifts from some higher power, they experience a sudden loss of all those gifts, but regain them and achieve heavenly transcendence. This transformation is usually the result of your character’s internal growth.

Cinderella

Now to everyone’s favorite, a true Cinderella story. In this arc, your character begins at rock bottom, as low as they can be. They are probably born to a low station or suffered a devastating tragedy early in life. As bad things are for your hero, the one thing that can’t be taken from her is her resilience. She has hope that things can get better, but she at least knows they can’t possibly be worse.

And things do get better. Your character experiences pure ecstasy for a short while. They discover what it means to be truly happy, but nothing lasts forever. Eventually, the clock strikes midnight, and that carriage turns back into a pumpkin.

However, the experience of happiness has a lasting effect on your hero. She will never again be as low as she started at the beginning of the story because she now has the memory of being happy. At your story’s climax, your hero will regain what she lost and experience an everlasting happiness!

Most stories you read or watch probably fit into one of these eight types of plots, or character arcs. So, if you’re struggling with the direction you’d like to take your story, use one of these basic plot arcs as your guide.

Plot Structure

What is plot structure .

Plot structure refers to the story beats, or series of events, that make up your story.

Above, with the shape of stories, we discussed character arcs. Now, with plot structure, we’re talking about story arcs. Like the shape of stories or character arcs, there are many different ways to approach how you structure your plot. Let’s start with the most common plot structure you’ll find.

Different types of plot structure

Freytag’s Story Pyramid

You probably know this plot structure, also called the story pyramid. It’s the plot structure you learned way back in grade school. Freytag’s Pyramid breaks down to five plot segments. They are as follows:

Exposition:

In a story’s exposition you establish the ordinary world. Introduce all of the main characters, and show them in their everyday life. Introduce the setting of the story as well as the mood, and maybe hint at the conflict. You’ll end this section with an inciting incident that shatters the ordinary world and begins the conflict.

Read more about inciting incidents here.

Rising Action:

This is where the plot starts to move. The inciting event has caused some significant problems for your hero. During the rising action, your character is trying, and failing, to solve their problem. The character’s action will get increasingly drastic. Rising action will take up the majority of your story.

This is the most thrilling part of your story; it’s the primary turning point. The climax is when the story’s main antagonist is finally confronted. The stakes are at their highest point. If your character loses, then they will die either literally or metaphorically. They will often have to overcome a character flaw to win.

Falling Action:

This is a moment of final suspense when the hero seems to have lost. Freytag suggests as few characters as possible are involved at this point of the story and that there are fewer scenes than there were during the rising action.

Catastrophe or Denouement:

The logical endpoint of your story. There should be some catharsis for your reader and a tying up of loose ends. Your hero may die in sacrifice at this point, or they may be triumphant. All conflicts should be resolved. A denouement sees your story ending on a high note. However, if you’re writing a tragedy, you’ll end with a catastrophe.

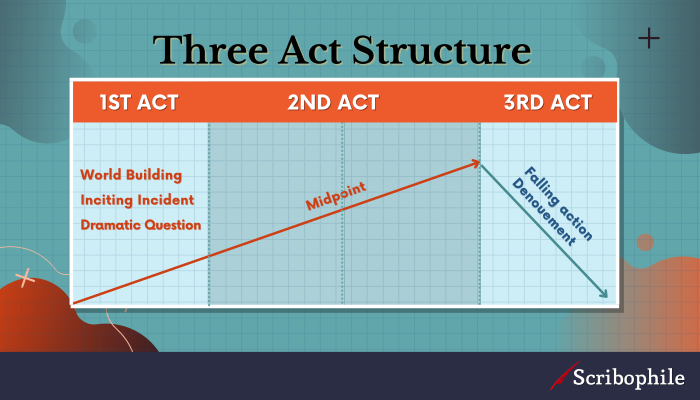

Three Act Structure

Popular for its simplicity, this is another plot structure commonly used in Western storytelling. As the name suggests, the design is subdivided into three acts with five plot points interspersed between them. Here they are:

Act I – Setup:

The setup in this structure is very similar to the story pyramid’s exposition phase. The author will establish characters, setting, and tone. You want to show the characters in their everyday life. The setup will contain, or be concluded by, the inciting incident, which will disrupt your character’s life.

- Plot Point 1: this plot point ends your setup. It is a dramatic event that represents the point of no return for your hero. Once this happens, they cannot return to their ordinary life. Think of it like a cave-in that seals your hero within the story.

Act II- Confrontation:

Your character struggles to overcome their conflict set off by the inciting event. They will try one thing after the other, each time not achieving their goal and becoming more extreme in their measures.

- Mid Point: happens in the middle of your story. It is the most dramatic turn up to that point. It raises the stakes for the hero exponentially.

- Plot Point 2: This ends the second act of your story. The second plot point is when the hero prepares to confront their antagonist. This point will set up the final confrontation.

Act III- Resolution:

The final battle or obstacle. The point where your character is truly tested. This act will change a fundamental part of your character’s life or personality as they overcome internal demons or external threats.

- Climax: The most intense part of your characters struggle. They may have a sudden realization of how to end the conflict, or they may have to overcome a deep-seated flaw.

Read more about Three Act structure here.

Developed in Japan, Jo-ha-kyū is more of a concept than a structure. Still, it is used to structure stories, especially in theatre. In Jo-ha-kyū, things begin slowly, speed up gradually, and end fast. Jo-ha-kyū has three stages:

Beginning :

Just like the other two structures, this is an exposition phase that moves at a leisurely pace.

The story begins to intensify here. Things start to speed up at a gradual pace. The plot intensifies.

The story moves at break-neck speed to its conclusion. All the conflict and loose ends are resolved.

Kishōtenketsu

Kishōtenketsu is a Korean story structure that prioritizes a significant plot twist over a pattern of conflict and resolution. We’ll go over the four parts of this structure today.

If you’d like to know more about Kishōtenketsu, you can read an entire post on the form here.

The four components of Kishōtenketsu are:

This is an introduction to characters, setting, mood, and any other important information.

This is a development stage. The author expands on the characters and setting established in the introduction.

TWIST! The twist is the most crucial part of the story. The dramatic twist takes the place of any conflict a typical story would have.

The conclusion of your story. Everything is wrapped up, and things return to normal.

Story vs. Plot

So, what is the difference between story and plot? The two can be hard to define, but most people have decided that causality differentiates the two.

A story is a retelling of events in chronological order with no definable through-line. A plot is a series of events organized by cause and effect.

With a plot, on the other hand, there is a clear depiction of cause and effect. A story can be reported in a newspaper as- there was a five-alarm fire in an apartment building last night. One person died. Investigators believe faulty wiring was the cause of the fire.

A plot would show us how these events are connected. A slumlord, building owner fires his hardworking superintendent to cut costs. Therefore, the faulty wiring in Mrs. Jones’ apartment is never fixed. On a cold night, Mrs. Jones plugs in a space heater to stay warm. With no one to repair it, the building’s furnace has been broken for months. A spark from the outlet catches the drapes on fire. The flames spread filling the bedroom with smoke. Mrs. Jones suffocates, and the slumlord cashes in on his insurance policy.

Here we see the cause and effect pattern, and even a theme developing.

Elements of a Plot

The plot elements depend on the type of story you’re telling, and we’ve covered many of them already. Plot points, climaxes, raising, and falling action are all elements of different plots. Let’s cover a few essential factors that are common to most plot structures.

Setup & exposition :

Most stories will start by introducing characters, settings, and a mood. Authors may also hint at a coming conflict or theme in this section.

Action & confrontation :

A majority of the time spent in any story will show a character trying to overcome some conflict in their life. Usually, they try small actions at first; then, as they continue to fail, action will gradually become more drastic. These actions lead to an escalation of the stakes of the story.

Climax & conclusion :

There is a high point of every story. A moment where the stakes are highest and failure means dire consequences for your hero. The character either overcomes their conflict or is consumed by it depending on the story you want to tell.

Dramatic Contrast :

Stories, like any work of art, need contrast. Contrast is what makes a story interesting. Ordinary characters can contrast with extraordinary events. The setup of your story will contrast with the conflict. You don’t always need conflict to create this contrast. In Kishōtenketsu arcs there is no conflict, but a jarring and dramatic twist is what creates contrast. Your character’s personality can create contrast. They may start the story as a coward and end as a hero.

Wrapping Up

Ok, there are about twenty-five hundred words on plot. We’ve discussed what plot is, the different types of plot, what makes a story different from a plot, and plot elements. I’d love to continue, but I, literally, have nothing left to say. So, if you have any questions about plot, please drop them in the comments. I’ll answer them. Promise.

If you want to read more about plot, here is an outstanding book, Story Genius , that taught me plenty!

Continued reading on plot

“ In Story Genius Cron takes you, step-by-step, through the creation of a novel from the first glimmer of an idea, to a complete multilayered blueprint —including fully realized scenes—that evolves into a first draft with the authority, richness, and command of a riveting sixth or seventh draft.”

Resources :

Author’s Guide to Storytelling- Reedsy Blog

Five Elements of Plot- The Write Practice

1,462 Basic Plot Types- Daily Writing Tips

This post contains affiliate links to products. We may receive a commission for purchases made through these links

Published by John

View all posts by John

1 comments on “What is Plot? A Writer’s Guide to Creating Amazing Plots”

- Pingback: What is the Protagonist in a Story? - The Art of Narrative

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Copy and paste this code to display the image on your site

Discover more from The Art of Narrative

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing group!

What is Plot? Definition, Examples & 10+ Types of Story Plots

by Fija Callaghan

It’s been said that there are a finite number of stories in the world. It’s also been said that there are more stories in the world that we can ever imagine. Both of these things are true.

New writers often find themselves overwhelmed by the indescribably vast landscape of plot. Maybe you have an idea for a great main character, or a place where you want to tell your story from, or even some glimmers of things you want your characters to be doing in these places. But is that enough for an entire story? Not quite. Your story needs plot —the structural road map that will carry your readers through to the very end. But what is plot, and how do we find the plot of a story? Let’s take a look at some definitions, plot elements, and a few examples to show you how it’s done.

What is plot in a story?

In writing, plot is the sequence of events that guides a narrative such as a novel, short story, play, or film. Every time a character makes a choice or reacts to the consequences of a choice, the plot of the story moves forward. This pattern of cause and effect hurtles the protagonist and everyone around them towards the climax.

There are a few different ways to map out your plot , but in the end most stories follow a pattern of action and reaction. The protagonist takes a step forward, makes a choice, creates something, or puts some new energy into being—this is the action. Then, the reaction : the protagonist’s action triggers an effect that they didn’t expect, or an effect they did expect but that has unintended consequences. In response, the main character takes another action. And the plot pushes back, again and again and again.

How these actions and reactions progress will naturally fall into the rhythmic patterns of storytelling that we call story structure.

Why do I need plot structure?

It’s not uncommon for new writers (or even experienced writers) to have some hesitancy when it comes to formally structuring their work. There’s often the fear that letting your plot fall into a recognizable pattern will make it somehow less original, less distinct, less yours .

It’s understandable to feel this way, but the truth is that all successful stories will naturally follow these patterns because they speak to the rhythms of storytelling that we all have within ourselves. When the plot points of a film or novel deviates too far from these plot structures we will usually feel it in our bones; something in the narrative isn’t working. It’ll begin to feel too rushed and chaotic, or too slow and drawn out, and in either case we’ll begin to lose our sense of immersion. We start to disconnect from it without entirely understanding why.

Plot structure is really just a clear, approachable way of looking at why stories affect us the way they do, why readers and viewers become so invested in the rhythms of these stories, and how we can recreate those rhythms in our own work.

What’s the difference between plot and story?

Plot and story are two literary elements that are inextricably entwined, but are they the same thing? Not quite.

The most important difference is that story establishes a framework of events that supports a larger theme, while plot explores the cause-and-effect relationship of how these events inform one another. To put it another way—story is about the who, where, and when while plot is about the how and why.

For example, the fable “The Tortoise and the Hare” is a powerful story with a strong plot. The story is: “The tortoise and the hare agree to race. Because of the hare’s arrogance, the tortoise wins and learns a valuable lesson about tenacity and commitment.”

The plot is: “The hare challenges the tortoise to a race. The hare runs so fast and is so certain of his victory that he takes a nap before he reaches the finish line. When he wakes, he discovers the slow tortoise has finished the race before him.”

The story gives us a picture of the work as a whole including its character development and theme, while the plot shows us how the story comes to be. You need both in order to create a coherent narrative work that resonances with your readers.

Elements you’ll find in every plot

For any plot to work—whether it’s a short story, novel, screenplay, or any other narrative form—it needs a basic plot foundation. You can think of these essential elements as the “Three Cs” of plot structure: character, causation, and conflict.

Character is the backbone of any good narrative. The most important element of plot structure, a character’s choices are what drive the story forward and encourage readers to empathise with their journey (we’ll talk a bit more about the “Hero’s Journey” story archetype below).

For a reader to care about what your story is trying to say, you need engaging main characters.

Causation is the pattern of factors that influence the events of the plot. This begins with the inciting incident—an external factor that instigates a change in the lives of your characters—and continues with every choice your characters make.

Every turning point in your plot is directly caused by the events that have come before it.

Conflict is what drives your characters to make the choices that they do. One character wants something, and another character wants something, and the plot happens because those desires can’t exist at the same time. Each character takes steps to pursue their goals, and in doing so, unleash an unexpected maelstrom of story.

Sometimes the conflicting goal might come from something like an impersonal organisation, or even a force of nature. You can read more about finding the right conflict for your story here .

The 7 universal stories

Most scholars agree that there are a certain number of plot archetypes which all stories across all mediums follow. What they tend to disagree on is exactly how many plot types there are. Aristotle, John Gardner, Kurt Vonnegut, Christopher Booker, Ronald Tobias, and Georges Polti are all scholars and authors who have tried to compartmentalise the diversity of story. They’ve suggested that all stories are born from a handful of different plot archetypes.

Today, most writers agree on the “seven story format,” which states that there are seven grand, overarching master plots that contain within them all the stories in the world. Many stories will fit snugly into one of these well-worn patterns, or master plots, that have been shaped and perfected over time; others will draw from two or more of these plot archetypes.

Let’s look at the basic plots that form these seven universal stories.

1. The Quest

In a Quest plot type, the protagonist begins with a very clear objective; this may be of his or her own choosing, or it may be something that is thrust upon them. In any case, the main character goes on a journey and faces a string of nearly insurmountable obstacles in order to reach their all-consuming goal: a physical object, a sacred place, an achievement that they can see and feel.

The Lord of the Rings is a classic example of a Quest plot, in which the main character goes through a series of trials in order to reach an object of great power. King Arthur’s story of the Holy Grail and King Solomon’s Mines are other Quest stories.

In contemporary settings, a quest can also be for things like intercepting a hastily sent email, gaining entry into a prestigious institution, or finding a rare copy of a valuable book.

2. Voyage and Return

These types of stories were popular in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. They feature a protagonist who goes off to discover a fascinating new place, full of treasures and creatures barely imaginable, before returning safely home with a wealth of new stories to share.

The Hobbit ’s well-known alternate title There and Back Again makes it clear that we can expect it to follow this age-old pattern. Alice in Wonderland, The Wizard of Oz, and Where the Wild Things Are are other classic examples of the Voyage and Return.

Although this plot type lends itself very well to fantastical settings, that doesn’t always have to be the case. A protagonist can “voyage and return” to an unfamiliar country, cultural landscape, or class of society.

3. Rags to Riches

This plot type tends to follow this arc not once, but twice: the protagonist begins in a place of disprivilege before coming upon a sudden change in fortune—whether that manifests as money, influence, attention, or love. Then—usually due to their own rash actions—the protagonist loses their newfound glory and has to work to get it back.

The difference in these two story arcs is that the first time the protagonist is usually given their “riches” as a twist of fate, while the second time the protagonist is forced to prove themselves worthy of the riches. Cinderella is a classic Rags to Riches plot, as is the fable of The Ugly Duckling , and Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess .

We tend to think of these reversal-of-fortune plots as stories of wealth and class, but they can also come in the form of newfound respect, beauty, or influence.

Many of these stories have their roots in Christian mythology, but today Rebirth stories are simply a character arc so dramatic as to affect a complete transformation. Usually these plot types begin with a deeply flawed character who, rather begrudgingly, begins to see the error of their ways and how they can become a better person.

A Christmas Carol is a classic archetypal example of how a thoroughly dislikeable man can, through powerful experiences and deep personal introspection, become someone who makes a positive impact on the world. Beauty and the Beast and The Snow Queen are faerie tales that also follow this plot type.

Today’s screenwriters know that the ability to make people laugh sells better than just about anything; it’s rare these days to see a film or TV series, no matter the genre, that doesn’t have some lighthearted moments in it.

In classic literature, however, the term “comedy” refers more to a continuous push and pull of dramatic irony—the reader or viewer always knows more than the characters, and we watch with bubbling delight as the cast of players gets themselves into one predictable scrape after another. In many ways, classic comedies show us our own flaws and give us permission to recognize those flaws as part of being human.

That’s not to say that comedies can’t have surprises—often the clever twists and unearthing of hidden secrets are the most satisfying parts of a well-written comedy. But no matter what path they take, the distinguishing characteristic of literary comedies is that they always have happy endings.

Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a classic example of comedy. P. G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves and Wooster , and Bridget Jones’s Diary are other stories that follow these patterns.

Contrary to comedies, a tragedy plot structure shows us our human failings and how they can be irreparably damaging. They usually follow a character with a major flaw or weakness that leads to their inevitable undoing. Often these are weaknesses that we can find within ourselves, which makes the protagonist’s downfall all the more resonant and compelling.

The Great Gatsby is an example of a modern tragedy, in which the choices the protagonist thinks will lead him to the love of his life are the same choices that send him hurtling towards his ultimate collapse. Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray and the quintessential tragedy Romeo and Juliet are other stories that show the power of human limitation.

7. Overcoming the Monster

The lifeblood of folk myths, this plot archetype shows an inspiring but very human character facing an opponent made out of nightmares. The “monster” in this case might be a literal creature from the dark; it might be a person behaving monstrously, like a serial killer in a thriller novel; or it might be a monster that lives inside of us, like mental illness or addiction.

Classically, however, the monsters faced were very real otherworldly antagonists. Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a famous example of an Overcoming the Monster story, and the legends of Beowulf and Saint George and the Dragon are ancient stories that have influenced our idea of monsters today.

Drawing on the 7 universal plots to create your own story

These seven plot types have existed since the first cave drawings appeared out of charcoal and firelight—since our ancestors spun stories out of shadows so they could hold onto the light a little longer. Many, many more stories will be written in the generations to come that follow these ancient rhythms.

But don’t feel that you need to limit yourself to just one of these structural outlines. Many successful stories draw from several of these archetypal patterns to create something powerful and new. The Wizard of Oz , for example, follows a character who explores a strange and wondrous land (Voyage and Return), goes in search of a mysterious power in order to help her friends and return home (the Quest), and faces a fearsome witch with her own reasons for taking our heroine down (Overcoming the Monster). This classic tale weaves together several plot archetypes to create something that readers have returned to again and again for generations.

When you begin writing, these seven plot structures will give you an idea of the patterns that storytellers have followed and recognized as great universal truths. Your work will probably draw on several or even all of them as it becomes a part of the neverending tapestry of story.

Plot structures to guide your fiction writing

Now that you know a little more about what the plot of a story is and why it matters in creative writing, let’s look at some classic ways to develop the plot of your story. By using a specific plot structure like ones outlined below, you can create a coherent series of plot points and connected events that will make you story work —every time.

How to plot your story using the three act structure

Human beings have always liked the number three. It’s the number from which our brains begin to recognize pattern, and so over the centuries that number has gained a lot of sacred significance in cultures all over the world. We see it in Christian mythology’s holy trinity, in the triquetra and three sacred trees of the Celts, in three wishes, in three crossroads, in the three witches of Macbeth, and in the three stages of life. “Three” feels complete. This is why the three act structure has remained such a powerful part of our storytelling consciousness for so long.

The first act

Despite being a third of the plot’s structural blueprint, the first act only takes up about a quarter of the plot. However, it packs in quite a lot of important information for such a small section.

The first act does three very important things from which our story can emerge: firstly, it introduces us to the world of our characters. In fantastical settings this includes our worldbuilding —our understanding of the world’s mechanics, politics, systems, beauties, and struggles. Much the same can be said of historical fiction; the first act helps the reader understand the story’s time and place, along with the strengths and limitations that come with that time and place.

Even in contemporary settings we’ll see the world of our protagonist, where they spend their time, who they spend it with, and their relationship to the world around them. This is called exposition , and without it as the foundation of our plot our story can’t exist.

The second is the inciting incident —the moment where our plot is launched into motion. This can be the arrival of a new character or a new piece of information, a disaster that changes the landscape of the protagonist’s world (physically or emotionally), a birth, a death, a choice—something that irreparably ruptures the characters’ world into a before and an after. This is where our story begins.

Lastly, the first act introduces us to our dramatic question . This is directly related to the inciting incident; it creates a question in the reader’s mind that the writer promises to answer by the time the plot reaches its close. Will the hero manage to save the city from imminent destruction? Will the boy reach the girl he loves before it’s too late? Will the heroine manage to escape and find her way back home? These questions are essential to create tension for the reader. Amidst the twists and turns the plot takes as it reaches its conclusion, this dramatic question stays with us continuously until the very end.

The second act

The second act is our major player; it takes up about half of the plot, or the second and third quarters. Once your main character has been thrown into a new set of circumstances by the first act, the second act will raise higher stakes and throw more obstacles in the protagonist’s way. This is where most of your story’s major events will occur.