You are using an outdated browser and it's not supported. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- LOGIN FOR PROGRAM PARTICIPANTS

- PROGRAM SUPPORT

Building Fluency: Unbound A Guide to 6-12 ELA/Literacy Practices

Introduction, what is fluency, why is fluency important, part 2: how english language arts instruction supports fluency, standards expectations, analyzing syllables, sharing the text to support fluency, text-based discussions, choral reading, reader’s theater, repeated oral reading, partner reading, sets of texts on related topics, a note about struggling readers, part 4: supporting fluency beyond the ela block, appendix: fluency strategy directions.

Welcome to the Unbounded ELA Guide series! These guides are designed to explain what the new, high standards for ELA say about what students should learn in each grade, what they mean for curriculum and instruction, and how we can implement teaching practices that support them. This guide, which focuses on fluency in Grades 6-12, demonstrates how fluency practice can be integrated into ELA and instruction across content areas. It includes four parts. The first part defines reading fluency and why it is important for overall reading proficiency. The second part provides insight into how fluency can be fostered within thoughtfully structured ELA instruction. The third part provides proven and practical activities, framed by the expectations of the standards, that can be integrated into the ELA block. And the fourth part provides guidance on how many of these activities can be used to support fluency beyond the ELA Block.

Why do we focus on fluency? Nearly two-thirds of U.S. students in grades 4, 8 and 12 cannot read proficiently. This isn’t a new problem, either: Only a small increase in the percentage of proficient readers has occurred in the last 25 years. 1 http://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading_math_2015/#reading http://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading_math_2015/#reading http://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading_math_2015/#reading The stakes have never been higher, though, as it’s increasingly difficult to meet the demands of college coursework and a range of careers without sophisticated reading and writing skills. The specificity and rigor of the new standards provide us with an opportunity to turn this tide, though—improving reading proficiency and life prospects for all students.

Part 1: Understanding Fluency

It’s likely that you have worked with students who stumble over words, sound them out very slowly, or read them too quickly in a robotic, monotone voice. These are examples of disfluent reading, and often indicate that these students are struggling with one or more of the characteristics of fluency. Fluency refers to how smoothly an individual reads and is defined by three characteristics:

- Accurate decoding and word recognition.

- Reading at a conversational pace.

- Reading with appropriate prosody, or expression.

Fluency is a critical link between decoding and comprehension. Although fluent reading doesn’t guarantee comprehension, we know that disfluent reading hinders comprehension, especially with complex texts. Disfluent readers, instead of being able to make meaning as they read, spend a disproportionate amount of cognitive capacity sounding out words or wrestling with sentence structure, leaving little time and energy to actually comprehend what they’re reading.

The good news is that fluency is an element of reading that can be improved relatively quickly with some attention and practice. We can work on building fluency during existing lessons, with few additional resources. The heaviest lift lies in planning to make time for a routine in which fluency instruction and practice is intentional and frequent.

Before we explore how to build fluency, let’s consider elements of fluency in a bit more detail. As fluent readers ourselves, we have developed automatic and accurate recognition of a great many words, and the ability to quickly sound out (or attack) those that we don’t automatically recognize. This automaticity allows us to maintain a conversational pace as we read. As fluent readers, we also understand intrinsically how to use intonation, pauses, stops, phrasing and inflection so our reading sounds as though we are speaking naturally to a friend. Our foundation of vocabulary and background knowledge provides support to help us make meaning of the text. These components that we rarely think about when reading are the foundations on which students’ reading fluency rests. To grow and improve students’ reading fluency, our goals must include:

- Building students’ word attack skills and word recognition .

- Building students’ understanding of how pace and expression are cued by syntax , vocabulary and text structure .

- Building students’ vocabulary and background knowledge.

Reading fluency can change with text content, genre or complexity, so we must continue to provide fluency practice for our students—beyond the elementary grades. We can achieve the goals above by integrating activities and teaching practices that target fluency into the context of the work we do within complex, grade-level texts. For struggling readers, it may feel counterintuitive to use grade-level texts, but this is the most effective approach to building fluency for students at all levels. Using grade-level (versus reading-level) texts will require us to move more slowly, but the support that accompanies fluency work—rereading, modeling and feedback—will help all students access the rigor of these grade-level texts. We will approach our fluency work through modeled readings, shared readings and repeated readings, which will allow us to support students’ productive struggle with the text. This shared struggle is designed to culminate in shared comprehension and success. Using complex, grade-level texts allows us to maximize gains within the short time we share with our students each day.

Part 3: Building Fluency During English Language Arts Instruction

Let’s begin by looking at fluency expectations. Then we’ll look at some activities we can use to support fluency using complex, grade-level texts. We’ll provide examples of where these activities can be included in lessons conducted with a variety of open educational resources (OER). Appendix A includes steps for how to conduct each activity or practice.

We don’t find any standards for Grades 6-12 that explicitly address fluency, as the expectation is that students arrive to these grades having already developed it. However, as previously mentioned, fluency can change with text content, genre or complexity. So it’s important that we continue to provide models of what fluent reading sounds like and practices that allow our students to improve their own fluency. It is also important to recognize that the standards that we do address in these grades are inextricably intertwined with fluency. In order to read the range, quality and complexity of texts demanded by the standards, our students will need to develop insight into knowledge of language ( ELA.RA.L.3 ) and structure of texts, ( ELA.RA.R.5 ) which will also assist their understanding of the expression with which the texts are to be read. They’ll have to develop background knowledge to fully understand the ideas expressed through text. With this background knowledge comes vocabulary ( ELA.RA.L.4 ) – the development of which contributes to our students’ ability to automatically and accurately recognize words, another key element of fluency. Finally, exposure to the range of genres exemplified by the standards ( ELA.RA.R.10 ) will foster in our students greater understanding of how each has its own appropriate pace and cadence of reading. While we address the standards, we provide conditions for improving fluency. By explicitly targeting fluency in our instruction, we support students’ comprehension of the texts they read.

Strategic word attack to build fluency

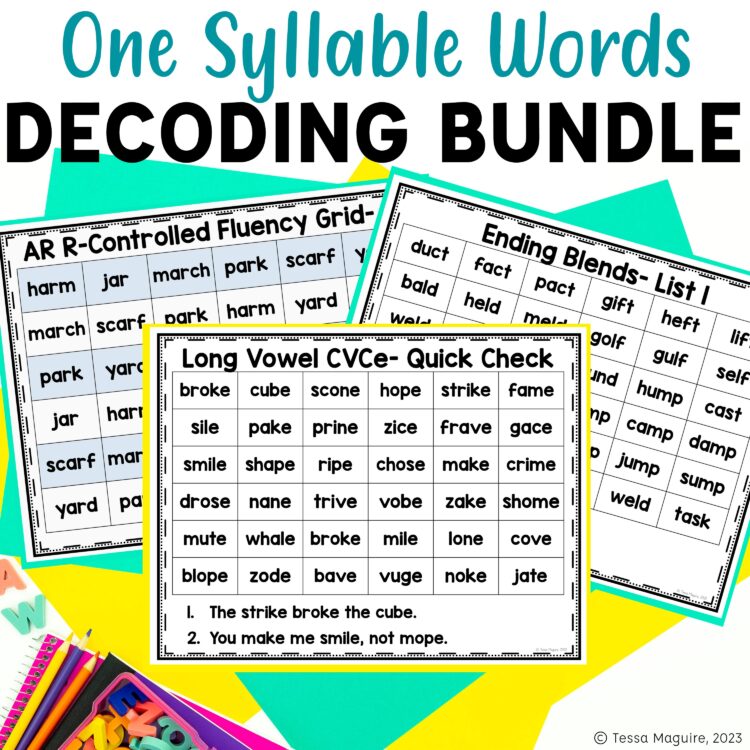

Before we look at strategies that practice incorporating all of the elements of fluency, let’s first take a look at how we can strengthen our students’ word attack skills. Remember, fluency requires automatic word recognition, and the ability to quickly “attack,” or figure out, words that are not immediately recognized.

We can teach our students to analyze syllables and word parts by explicitly teaching them the six syllable types (see “The Glorious Whitewasher” example below) and providing them with practice blending and segmenting known syllables to form and read words, phrases and sentences created from those syllables. We need to teach our students to look for meaningful chunks in unknown words. Understanding how to break words into syllables will aid them in pronunciation of words that they do not recognize.

Our students who struggle in reading often have trouble with multisyllabic words. For struggling students, these word attack skills are critical if we want them to make progress. For some students, this may require systematic, intentional intervention beyond the ELA classroom. During ELA, however, our struggling readers can benefit from instruction and practice in recognizing the spelling patterns that comprise syllables and morphemes (meaningful word parts, like prefixes and suffixes), improvement of which can improve the automaticity with which words are decoded and recognized.

Syllable instruction and practice as part of a routine, will allow us to strengthen students’ ability to quickly figure out unknown words. The grade-level text you are currently using in class can be used as a resource to reinforce how to divide words into syllables, analyze them and blend them again to read them. This blending and segmenting practice with known words will support students’ ability to apply the analysis to unknown words.

When to use syllabic analysis:

- Explicitly teach students the six syllable types and rules for segmenting words based on the syllable, providing additional practice opportunities for struggling readers as often as possible.

Texts to use:

- Choose grade-level texts and passages from grade-level texts that you are using in your classroom instruction.

- Choose lists of words (for oral reading) that demonstrate the six syllable types.

Morpholog y

Understanding the meaningful parts of words (morphemes) helps both strong and struggling readers to determine or infer word meanings. When they learn about prefixes and suffixes, they begin to understand that there are word parts that have common meaning across words. Knowledge of these word parts will support both decoding and comprehension and, with enough practice, recognition of words. Targeting these word parts can be quite efficient: The seven most common prefixes account for 70 percent of prefixed words in printed English texts for Grades 3 through 9:

The meanings of suffixes are often less concrete, but are more frequently used in students’ oral language, so learning to recognize them, with instruction and practice, can also be a powerful step toward fluency (and for proficient students, support additional vocabulary acquisition). Again, when we teach a small number of these suffixes, we build students’ ability to apply meaning to many words. The five most frequent suffixes account for 75 percent of suffixed words in printed English texts for Grades 3 through 9:

When we provide students skills that help them to recognize, decode and understand the most common syllable patterns and affixes, we provide them with word-attack skills that will help them to read words comprised of those parts. By strategically focusing our work on the affixes that appear most often, we can maximize results in the limited time that we have with students.

When to use morphological analysis:

- Explicitly teach students common root, base and compound words, along with common prefixes and suffixes during ELA class, providing additional practice opportunities for struggling readers as often as possible.

- Subsequently, choose words from the text that will enhance the meaning of what students are reading.

- Multiple exposures to these target words will support memory and retrieval, expanding the student’s repertoire of recognized words.

- Choose g rade-level texts and passages from grade-level texts that you are using in your classroom instruction.

CCSS Exemplar Text: From Tom Sawyer, “The Glorious Whitewasher”

Many adolescent struggling readers are challenged by multisyllabic words, often skipping letters or entire syllables as they read. Teaching our students to break words into their syllable components will assist them in decoding unknown words. We can provide instruction in and practice segmenting and blending the six syllable types and common affixes using passages from the grade-level texts we use in class. The example below demonstrates words within the passage that will allow us to provide practice with syllabication and morphological analysis.

Segmentation for each syllable type appears in green and is annotated below. Yellow highlights indicate common prefixes and suffixes. When we provide instruction on these word attack skills, along with practice reading text that contains opportunities to use them, we help our students decode, become familiar with and understand new words.

But Tom’s energy did not last. He began to think of the fun he had planned for this day, and his sorrows multiplied. Soon the free boys would come tripping along on all sorts of delicious expeditions, and they would make a world of fun of him for having to work—the very thought of it burnt him like fire. He got out his worldly wealth and examined it—bits of toys, marbles, and trash; enough to buy an exchange of WORK, maybe, but not half enough to buy so much as half an hour of pure freedom. So he returned his straitened means to his pocket, and gave up the idea of trying to buy the boys. At this dark and hopeless moment an inspiration burst upon him! Nothing less than a great, magnificent inspiration.

But Tom’s en /er/gy did not last. He 1 be Syllable type 1: Open Vowel /gan to think of the fun he had plan/n ed for this day, and his sor/row s multi /pli ed . Soon the free boys would come trip/p ing a/long on all sorts of de /li/ cious ex /pe/di/ tions , and they would make a world of fun of him for hav/ ing to work—the very thought of it burnt him like

f i r 2 e Syllable type 2: Silent e . He got out his world/ ly wealth and ex /am/in ed it—bit s of toy s ,

mar/b 3 les Syllable type 3: consonant -le , and trash; e/nough to buy an ex /change of WORK, may/be, but not half e/nough to buy so much as half an hour of pure free/ dom . So he re /turn/ ed his

str 4 ai Syllable type 4: Vowel Team /ten ed means to his

p o c/k 5 e Syllable type 5: Closed Vowel t, and gave up the idea of try/ ing to buy the boy s . At this dark and hope/ less mo/ ment an

in /sp 6 ir Syllable type 6: r-controlled Vowel /a/ tion burst up/on him! Noth/ ing less than a great, mag /ni/fi/ cent in /spir/a/ tion .

1 Syllable type 1: Open Vowel

2 Syllable type 2: Silent e

3 Syllable type 3: consonant -le

4 Syllable type 4: Vowel Team

5 Syllable type 5: Closed Vowel

6 Syllable type 6: r-controlled Vowel

Twain, M. (1884). The adventures of Tom Sawyer. Hartford: The American Publishing Company.

Launching To Kill a Mockingbird: Establishing Reading Routines (Chapter 1)

We can explicitly teach students common root, base and compound words, along with common prefixes and suffixes. Then, choose words from the text that will enhance the meaning of what our students are reading, and provide attention to the vocabulary words and other words that have the same morphological (meaningful) parts.

Teaching Notes

This lesson introduces students to a new structured notes routine that they will use throughout their study of the novel. Students used Structured Notes graphic organizers during Module 1 (while reading Inside Out & Back Again). But because the demands of To Kill a Mockingbird are different, the “structure” of the structured notes is also different here in Module 2A. 1 With each reading assignment, students write the gist of the reading homework, answer a focus question, and attend to teacher-selected vocabulary words. Key words for each chapter include academic words that serve a number of purposes. Most have prefixes, suffixes, or Latin and Greek roots. Many are adjectives that are used to describe setting or characters. Others are words students should know to understand critical incidents in the novel. Help students see connections between vocabulary and words in the same family for instance, allusion - allude; assuage - suave; disturbance - turbulence; ambled - ramble; optimism - optimum .

Lesson Vocabulary

allusion, assuaged, “the disturbance”, ambled, vague, optimism

1 Help students see connections between vocabulary and words in the same family for instance, allusion - allude; assuage - suave; disturbance - turbulence; ambled - ramble; optimism - optimum .

Expeditionary Learning, Grade 8, Module 2A, Unit 1, Lesson 8

Copyright © 2013 by Expeditionary Learning, New York, NY. All Rights Reserved

As ELA teachers, most of us would agree that great and rich texts deserve to be read more than once: Every time we go back to our favorite work, we have the opportunity to get something new from it. Several strategies for increasing fluency involve rereading:

Masterful Reading (Modeling)

When we read aloud—masterfully—to students, we can both model pronunciation and emphasize appropriate expression and pace. We can use read-alouds to draw our students’ attention to changes in the way a text is read. Some of our students may not really know how elements in the the text cue fluency. This is one of the reasons why a masterful read-aloud to explicitly model (and discuss) what fluent reading sounds like is helpful. As we read, we can also draw our students’ attention to and discuss the relationship between text structures, word choice, syntax and meaning. This allows us to foster in our students a habit of paying attention to language and not just the individual words in the text. This modeling will help our students imagine what their own reading is supposed to sound like. It is important that we give our students multiple opportunities to reread the passages that we model.

When to use masterful read-alouds:

- Introduce more complex texts and new genres by demonstrating what fluent reading sounds like through a masterful read of the text.

- Subsequently, provide an opportunity for students to reread the passage or text on their own.

- Choose complex texts 2-3 levels above grade level for read-alouds.

- Choose passages from grade-level complex texts.

Developing Core Proficiencies English Language Arts / Literacy Unit"The wolf you feed"

The lesson excerpts below demonstrate how a masterful read-aloud can be included in the context of a lesson.

Read Alouds and Modeling (p.5) : At key parts in the instruction, teachers read text aloud so that students can listen to the cadence and structure of texts while also following along themselves. By listening to a proficient reader, students pick up on natural pauses and pronunciation of words. Teachers also model “think alouds,” wherein they discuss what they visualize and think as they read. Teachers thus model reading proficiently, and also model using the skills and graphic organizer tools that help students learn to read closely. Students see the tools and skills modeled before they apply them, first in pairs or small groups, then independently.

Read Text #2 Aloud (p. 14)

- Direct students to the questions listed under “Topic, Information, and Ideas” in the Questioning Texts row of the GQ Handout.

- 1 As you read the passage aloud, students think about the question: “What information or ideas does this text present?” It is helpful to give students a purpose for listening before you conduct a masterful reading.

- Ask students to record/share their responses to the question, making sure that students refer to the text to support their responses.

Independent Reading (p. 14)

- Before students reread the passage independently, direct students to the questions listed under “Language” in the Questioning Texts row of the GQ Handout.

- Students think about the question: 2 “What words or phrases stand out to me as I read?” Drawing students’ attention to the words develops the habit of attention to language and not just the individual words in the text.

- While reading independently, students mark details they notice (electronically or with a pencil/highlighter).

1 It is helpful to give students a purpose for listening before you conduct a masterful reading.

2 Drawing students’ attention to the words develops the habit of attention to language and not just the individual words in the text.

Reading fluency can change with text content, genre or complexity, so introduce more complex texts and new genres by demonstrating what fluent reading sounds like through a masterful read of the text. Subsequently, provide an opportunity for students to reread the passage or text on their own.

Odell Education: Reading Closely for Textual Details, Grade 6

© 2015 Odell Education

Much of our work in Grades 6-12 will involve text-based discussions. We’ll use these discussions to dissect complex texts with our students, to ensure understanding of both the text and the meaning. To facilitate meaningful discussion, we need to assess which parts of the text will challenge our students. These are the clauses, phrases and vocabulary that we must highlight, model and discuss. For instance, by making sure that our discussion includes talking about text features that cue changes in expression and pace, we help our students build fluency and understanding at the same time. Don’t forget conversations about vocabulary—identifying morphological origins of words will support students’ word recognition and understanding. Point out how words are grouped to form meaningful phrases that change the pace and expression with which they are read.

For our struggling readers, select words from the text to practice syllable and affix word attack skills. We can help our students to better understand by having them practice parsing and chunking complex (juicy) sentences into their meaningful parts. Make sure these sentences and passages are read more than once, to strengthen both meaning-making and development of fluency. Having students shift their intonation and expression each time they read the sentence or passage can help them to understand how expression, called prosody, can change the interpretation of the sentence or passage. With practice, a reader with good prosody can use his or her skill to experiment or problem solve in order to find the intonation and expression that applies the correct meaning to an otherwise confusing phrase.

When to use text-based discussions:

- During shared reading of complex texts

- During masterful reading (read aloud) of complex texts

- Choose complex grade-level texts for shared/supported reading.

- Choose complex texts 2-3 levels above grade level for read alouds.

To learn more about facilitating discussions and sentence deconstruction, see What Does Text Complexity Mean For English Learners And Language Minority Students? by Lily Wong Fillmore & Charles J. Fillmore.

United States. Preamble to the United States Constitution.

When reading this text with our students, we can discuss elements of vocabulary, syntax and text structure that will impact the pace and expression with which it is read.

A passage like this is worthy of several rereadings to help students tease out the meaning.

On the first reading, we’ll have a class discussion about the gist of the passage. On the second and third readings, we’ll define vocabulary and discuss punctuation and what it means for how the passage is read (stops, pauses, intonation). It is helpful for us, while planning our instruction, to annotate these things in our text. On the fourth reading, we’ll discuss the pronouns and their [referents] . Beginning with “We” and its relation to “ all of the people of the United States ,” for whom the constitution is created. It is especially important for us to discuss pronouns because our students are often tripped up by not understanding to whom or what a pronoun refers. This confusion hinders fluency and comprehension. It is helpful for us, while planning our instruction, to annotate these things in our text.

During the next reading, we’ll have students use their new understanding of punctuation to break the fourth sentence into its component parts. Then, we’ll discuss the meaning of each part with students’ new understanding of vocabulary and pronouns.

Now we’ve fully prepared our students to reread the passage (one more time) with understanding and expression.

U.S. Constitution, pmbl.

Oral Reading

One of the easiest ways we can provide our students with practice and assess their progress in fluency is to listen to them read orally and to make sure that they have opportunities to listen to good examples of fluent oral reading. The oral reading activities described below provide models of what fluent reading sounds like, engaging all students in the task, and protecting weak readers from the embarrassment that comes from round-robin and popcorn reading. The activities below can be used individually, or in combination with one another to provide students with multiple opportunities to orally reread the same text.

Model pronunciation, pace and expression while reading a passage to the class or group, then read the same passage in unison, with the students. Choral reading provides students with a model of fluent reading and a gradual release from group reading to independent reading of the passage. Repeat the choral reading over several days to increase students’ fluent reading. As the week progresses, gradually release responsibility to transfer reading to our class.

When to use choral reading:

- Use this activity to introduce an introductory excerpt from the first text about a new topic (for topically related text sets) or to introduce new genres.

- Use this activity to introduce and practice pace and expression for poetry.

- Assign choral reading passages as homework (repeated oral reading) after choral reading takes place.

- Choose p assages from texts used for instruction 2-3 minutes long (approximately 150-300 words), including:

- Complex texts at or slightly above grade-level for shared/supported reading.

- New or previously read texts or passages.

- Achieve the Core fluency packets for Grades 6-8 and Grades 9-10 .

For reader’s theater, students rehearse reading of a text containing parts for multiple readers in preparation for oral presentation. Be sure that presentations are expressive oral readings and not memorizations of the text. It can be tempting to have students memorize scripts and poems, but for the purposes of fluency practice, it is the reading that is important.

When to use Reader’s Theater:

- Use this technique in class groups, pairs or individually to deliver texts that lend themselves to presentation.

- Ensure that presentations are expressive oral readings and not memorizations of the text.

- Choose g rade-level texts that provide an authentic purpose for presentation such as poems, plays, personal letters, speeches and narrative texts that include dialogue.

A Choral and Dramatic Reading of Macbeth

In these lesson excerpts, the Reader’s Theater techniques are use to help our students interpret self-selected scenes from Shakespeare’s Macbeth. One adaptation we could make is to include a masterful read and or choral reading of a passage before students select and practice their own passage.

It is important for Reader’s Theater to choose texts that provide an authentic reason for oral reading. Macbeth offers a perfect opportunity for the approach, as the piece includes several parts meant for dramatic reading.

Introduction In this lesson, students use interpretive dramatic reading techniques to interpret self-selected scenes from William Shakespeare’s Macbeth . After meeting in their small groups for a final rehearsal, students present their interpretive dramatic 1 reading Be sure that presentations are expressive oral readings and not memorizations of the text. It can be tempting to have students memorize scripts and poems, but for the purposes of fluency practice, it is the reading that is important. performances, either to a group of peers or to the whole class, who evaluate the performances and/or digitally record for future teacher review.

Addressed Standards

L.9-10.5.a , b

2 Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meanings. The standards place a focus on understanding how the nuances of the language and words contribute to the work’s meaning.

A high performance response to the task should should demonstrate this understanding.

a. Interpret figures of speech (e.g., euphemism, oxymoron) in context and analyze their role in the text.

b . Analyze nuances in the meaning of words with similar denotations.

Assessment(s)

Student learning in this lesson is assessed via student participation in the following task:

- Choose an excerpt from Macbeth. Deliver the excerpt demonstrating your understanding of the cumulative impact of Shakespeare’s specific word choices on meaning and tone.

High Performance Response(s)

A High Performance Response should:

- Demonstrate fluency through appropriate reading rates, volume and expression.

- 3 Demonstrate understanding of the cumulative impact of words on meaning and tone through expressive reading. This understanding in turn supports students’ understanding of the pace and expression that should be exhibited in a fluent reading of the text. A high performance response to the task should should demonstrate this understanding.

Activity 1: Introduction of Lesson Agenda Begin by reviewing the agenda and the assessed standards for this lesson: RL.9-10.4 and SL.9-10.1.b . In this lesson, 4 students complete a final rehearsal of their interpretive dramatic readings before performing for small groups of peers. Again, to target fluency, it is important to make sure that our students know that the presentations are dramatic readings and not memorized recitations of the text. Students may digitally record performances for later review. Students conclude by evaluating their peers and completing self-assessments.

1 Be sure that presentations are expressive oral readings and not memorizations of the text. It can be tempting to have students memorize scripts and poems, but for the purposes of fluency practice, it is the reading that is important.

2 The standards place a focus on understanding how the nuances of the language and words contribute to the work’s meaning.

3 This understanding in turn supports students’ understanding of the pace and expression that should be exhibited in a fluent reading of the text. A high performance response to the task should should demonstrate this understanding.

4 Again, to target fluency, it is important to make sure that our students know that the presentations are dramatic readings and not memorized recitations of the text.

The Interpretive Dramatic Reading Performance Checklist from lesson 16 can be used to evaluate student performance. As you assess student reading of the passage, consider those elements of the reading that demonstrate characteristics of fluency. The checklist’s exemplars for language, expression and performance stress important elements of fluency practice.

Public Consulting Group, Grade 10, Module 4, Unit 2, Lesson 20

© 2014 Public Consulting Group

Repeated reading of previously read grade-level texts helps students recognize words and spellings. The repetition from rereading provides great practice and new learning. It is also an excellent strategy for helping students to comprehend increasingly complex grade-level texts. Repeated reading provides our students with increasing familiarity with the text—its words and its literary and syntactical features.

When to use repeated oral reading:

- Have students reread complex sentences and passages as part of text-based discussions aimed at eliciting meaning from the text.

- Introduce new texts through read-alouds and oral reading, then give students time to practice orally reading the text repeatedly throughout the week.

- Choose c omplex grade-level texts for shared / supported reading.

- Use selections from texts are being used for instruction, or use the topic related texts.

- Choose Achieve the Core fluency packets for Grades 6-8 and Grades 9-10 .

Partner reading is a strategy that allows your students to provide support to one another. Pair students to practice reading orally to one another, alternating sentences, paragraphs or pages. Provide guidance for students regarding how and when to correct one another. In doing so, more proficient readers will model for their peers important elements of fluent reading including pace, expression and self-correction. In turn, the more proficient readers will gain reading exposure that continues to strengthen and grow their own fluency. We can also conduct a “whisper” partner reading, where students read to one another in pairs or small groups at a whisper level. Whisper reading will create a less distracting background if small group work is being conducted at the same time as partner reading. In either case, circulate through the groups or partnerships, to assess students’ fluency.

When to conduct partner reading:

- Allow students to read to one another during small group work with other student or while rotating to monitor progress.

- Choose g rade-level texts that are the focus of instruction.

“St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves” by Karen Russell

Lessons can be easily adapted to include partner reading. The lesson excerpt below illustrates one such opportunity.

Activity 4: Reading and Discussion Instruct students to form groups. Post or project the questions below for students to discuss. Instruct students to annotate the text as they read and discuss, and to keep track of character development in the text using the Character Tracking Tool.

- If necessary to support comprehension and fluency, consider using a masterful reading of the focus excerpt for the lesson.

- Differentiation Consideration: Consider posting or projecting the following guiding question to support students in their reading throughout this lesson:

How does Russell describe the pack?

1 Instruct student groups to read pages 225–227 Rather than having groups of students silently read the passage, we can have pairs partner read orally to one another. This will allow students to practice and will allow you to monitor their fluency as you rotate amongst the students. Provide clear guidelines on when to alternate reading and how to provide feedback to the reader. Be sure to pair struggling readers with a more fluent reader who can provide a fluent model of reading during his or her turn, and who can provide feedback and support to their partner. of “St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves” (from “Stage 1: The initial period is one in which everything is new” to “our parents were sending us away for good. Neither did they”) and answer the following questions before sharing out with the class.

1 Rather than having groups of students silently read the passage, we can have pairs partner read orally to one another. This will allow students to practice and will allow you to monitor their fluency as you rotate amongst the students. Provide clear guidelines on when to alternate reading and how to provide feedback to the reader. Be sure to pair struggling readers with a more fluent reader who can provide a fluent model of reading during his or her turn, and who can provide feedback and support to their partner.

Public Consulting Group, Grade 9, Module 1, Unit 1, Lesson 4

Reading sets of texts on a related topic across subsequent days supports fluency by reinforcing vocabulary and content. Two or more authors writing about the same topic will use many of the same words, and this repeated exposure builds vocabulary and content knowledge, which supports the development of fluency and comprehension.

It is important for us to make the distinction between topically related and theme-based texts. Although themes, like struggle, friendship and heroism, can connect texts, these texts won’t likely include much overlap in vocabulary. The theme itself may have some vocabulary associated with it (e.g., hero, villain, courage), but the texts likely will be about different situations or characters representing the theme. Topics, or domains of knowledge, on the other hand, bring with them the vocabulary of the topic (e.g., the topic plants has a common vocabulary of root, leaf, stem, photosynthesis, nutrient, etc).

Occasionally reading aloud from sets of related texts will support our students’ development of language, vocabulary and content. This repetition supports word recognition for shared and independent reading. These text sets provide benefits similar to repeated reading—increased exposure to and repetition of a set of common words, but also offer the benefit of allowing our students to read a different text rather than rereading the same text.

When to use related texts:

- Conduct shared and scaffolded reading of sets of texts on a related topic to address grade-level reading and writing standards.

- Read and discuss related texts to build knowledge and vocabulary during occasional read-alouds.

- Choose content-rich fiction and nonfiction about a related topic (e.g., plants, Native Americans, insects).

- Choose exemplars of sets of related texts including:

- Achieve the Core Grade 6 and Grade 7 Expert Packs

- Achieve the Core Grade 9 and Grade 10 Expert Packs

Students who are reading behind grade level need many opportunities to engage in a volume of reading that includes a wide variety of genre and topics. Remember, it takes a repeated exposure to a large amount of text to acquire a deep inventory of words that are instantly recognized. This additional reading also deepens the reader’s knowledge of the world, which increases comprehension. Unfortunately, struggling students—as a result of their poor reading—often lack the motivation to engage in the amount of reading that will, in turn, improve their reading. It is incumbent upon us, across all content areas, to find ways to support and encourage reading throughout the day. This additional reading (i.e., reading beyond the texts we are teaching) can be guided or not, it can include reading-level texts as well as those above the students’ reading levels, and it can be fueled by interest to the reader. Intervention and support for struggling readers must include opportunities to read and must not come at the expense of interaction with grade-level texts or knowledge and vocabulary building content.

The standards call for an increasing balance of fiction and nonfiction, and not just in the ELA block, but other parts of the school day as well. Some of the nonfiction reading can take place in the social studies and science blocks. We can use reading of content area texts as opportunities to include additional lessons and activities build students’ reading fluency. Many of the same activities and practices can be used to support fluency in the content areas, with minimal shifts and nuance.

Modeling Fluent Reading of Text

Use read-alouds of content area texts to emphasize expression and pace while reading aloud during social studies and science. Through read-alouds you can introduce new topics and model pronunciation of related content area vocabulary before students have to read these words on their own. This gives students a solid footing for their independent and scaffolded reading about the content.

Sets of Text on Related Topics

Use a variety of books, articles, digital sources, etc. about content area topics of study to provide exposure that reinforces common vocabulary and concepts through different texts. Reading across texts about the same topic will support development or word recognition along with content knowledge.

Text-based Discussions

Engage students in discussions about complex sentences, text structure and new vocabulary found in content area texts. Parse complex sentences into their component parts, having students describe the meaning in of each part in their own words. Be sure to bring closure to the conversation by allowing students to put the component parts back together, discussing meaning based on their new understanding of the component parts of the sentence.

Also have students reread complex sentences and passages as part of text-based discussions aimed at eliciting meaning from the text.

Assign a passage from the text as homework to be read aloud nightly, at home—or provide such text, related to subject area content, to ELA teachers for their use.

Use choral reading to introduce an introductory excerpt from the first text about a new topic (for topically related text sets). This passage can also be assigned as homework (repeated oral reading) after choral reading takes place.

Use reader’s theater for content area texts, like speeches, plays and poetry, allowing rehearsal time in class or at home. Have all students prepare for presentation, even if time doesn’t permit individual presentations. Different students can present each time this activity is used.

As we said at the outset of this guide, fluency is an element of reading proficiency that can be improved relatively quickly with little in the way of additional time and resources. A few last things before you embark on targeting reading fluency:

- Frequency is important—embed fluency activities into lessons within and beyond the ELA block as often as you can. With attention and practice, fluency can be improved for most readers.

- Fluency changes with text complexity, context or genre—that is, students who read one text fluently may not read another type of text with the same level of fluency. Supporting fluency is an ongoing endeavor, rather than a goal that is achieved.

- Intervention and support for struggling readers must include opportunities to read and must not come at the expense of interaction with grade-level texts or knowledge and vocabulary building content.

Repeated oral reading

Repeated oral reading is an activity in which a selected passage is read aloud, repeatedly during the week. Repetition builds accurate word recognition, expression, pace—the elements of fluency. Rereading provides great practice and new learning. It is also an excellent strategy for helping students to comprehend increasingly complex grade-level texts:

- A fluent reader (teacher, coach or more fluent peer) reads the passage to student.

- Student reads the passage focusing on reading at an appropriate pace, accurately pronouncing words, and reading with appropriate expression.

- The fluent reader provides the students with feedback regarding pace, pronunciation and expression.

- The student continues to practice orally reading the text over the course of the week.

- The teacher monitors oral reading throughout the week and assesses oral reading at the end of the week.

Choral reading

Choral reading is an activity in which teacher and students (whole class or group) read together, in unison. Choral reading provides students with a model of what fluent reading sounds like, including pronunciation, expression and pace. This activity also provides gradual release of students from group practice to independent reading of the passage.

- The teacher models pronunciation, pace and expression while reading a passage to the class or group.

- Teacher and children then read the passage together, as the teacher rotates to monitor individual children’s reading. Note: Initially, students may need practice reading in unison, but with a little practice starting and stopping together, students will acquire the routine.

A note about purposeful text selection: Students benefit most when excerpts and texts for choral reading are of grade-level complexity and do not take more than three minutes to read aloud. Matching the topics in choral reading to the topic being studied benefits students by building content knowledge and vocabulary.

Partner reading

Partner reading can be done in two ways.

A. Students can read aloud to one another, taking turns by sentence, paragraph or page, with the peer reader providing feedback on pronunciation, pace and expression. Partner reading supports self-correction through modeling and word recognition.

- Select a turn-taking cue (sentence, paragraph, page) and model for students how turn-taking will take place. Also, model for students how they are to provide feedback to their partner.

- One student reads until his or her turn is complete, while the partner student follows along in the text.

- The partner student provides feedback and correction as needed during the reading.

- The process is repeated as each turn is taken.

- The teacher monitors pairs to ensure progress and attention to the task.

B. Partner reading can also take the form of “whisper” reading, where students read chorally in pairs or groups in a whisper, allowing for less distracting background noise. As a teacher circulates through groups or partnerships, students can raise their voices to an oral reading level for teachers to get a better feeling for their fluency.

For students who need more support, variations on partner reading that provide modeling can be employed, with the understanding that a strong classroom culture is necessary for the following to take place successfully without student humiliation.

In the listening while reading variation, partners read the same portion of the passage, with the more fluent partner reading aloud first and thus, modeling for his or her partner, who follows along silently. The less fluent partner then reads aloud while the more fluent partner provides corrective feedback and support as needed. The pair then moves to the next sentence, paragraph, or page, using the same process.

In the tandem reading variation, the pair read aloud in tandem with the more accomplished reader providing a model for his or her partner, until the less fluent reader signals that he or she is ready to continue on his or her own. When the student makes a reading error, tandem reading begins again, until the less fluent reader again signals that he or she is ready to continue solo.

Reader’s theater

Reader’s theater is an activity in which a text is divided into parts for each reader and read-aloud. The text is practiced throughout the week (repeatedly read) for presentation at the end of the week. Reader’s theater provides purposeful practice of pace and expression, and through rehearsal provides repetition that builds word recognition. It’s important to note that during presentation, students are reading the text with expression, rather than performing the text from memory.

- Teacher chooses a text suitable for performance (poems, speeches, scenes from plays and text with dialog are particularly suitable).

- The teacher performs a model reading of the text, then assigns parts to students.

- Throughout the week, time is dedicated to oral practice, with some practice time spent mid-week specifically focused on expressive reading of the selection.

- At the end of the week, the text is presented to the audience.

Practice beyond mastery

It’s important to ensure students have the opportunity to practice beyond simply mastering the spelling-sound correspondences. The goal is for students to reach automaticity. This will require ongoing practice accompanied by corrective feedback. Even the world’s best home run hitters still go to batting practice. That is, they practice, even though they have already mastered the home-run hit. This is similar with fluency: to foster automatic decoding, we need to provide practice (beyond mastery) of letter-sound correspondences we’ve already taught, even as we move on to teaching new letter-sounds correspondences.

Practice beyond mastery also plays a role in developing automatic word recognition. The more students read, the more individual words they recognize automatically. With explicit instruction and plenty of time reading, many high-frequency words (words that appear repeatedly in a variety of texts) become recognized. Over time, words that students have repeatedly decoded also become recognized, so they no longer need to be sounded out.

Providing topically related sets of texts

We support the development of vocabulary and content knowledge when we provide topically related reading. Several authors writing about the same topic are likely to use many of the same words. Repeated exposure to vocabulary in context builds vocabulary and content knowledge, which supports the development of fluency and comprehension.

Why topically related and not theme-based texts? While themes, like struggle, friendship and heroism can connect texts, these texts will likely not include much overlap in vocabulary. The theme itself may have some vocabulary associated with it (e.g., hero, villain, courage), but the texts will likely be about different situations or characters representing the theme. Topics, on the other hand, bring with them the vocabulary of the topic (e.g., the topic of plants has a common vocabulary of root, leaf, stem, photosynthesis, nutrient, etc.), allowing for students to build their fluency in reading around that topic.

Modeling and discussion

Some children may not really know how elements of the text cue fluency, and this is one of the reasons why reading aloud to explicitly model (and discuss) what fluent reading sounds like is helpful. As we read, we can also draw students’ attention to and discuss the relationship between text structures, word choice, syntax and meaning. This allows us to foster a habit of attention to language and not just the individual words in the text. To get the most success using modeling and discussion, planning prior to class is a critical component. To facilitate meaningful discussion, we need to assess which parts of the text will challenge our students:

- Choose several sentences or short passages from a current text that are complex and convey important elements of meaning.

- Parse the sentence or passage so that we can clearly identify elements of main and subordinate clauses, including the subject, verb, topic and action.

- Translate each part of the passage to its meaning ahead of time.

- Identify elements of text structure and meaning-making word choice included in the text.

Bibliography

Allington, R. L. (1983). Fluency: The neglected goal of the reading program. The Reading Teacher , 36, 556–561.

Allington, R. L. (2014). How Reading Volume Affects both Reading Fluency and Reading Achievement. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education , 7 (1), 13.

Allington, Richard L. What really matters for struggling readers: Designing research-based programs. New York, NY: Pearson, 2012.

Archer, A. L., Gleason, M. M., & Vachon, V. L. (2003). Decoding and fluency: Foundation skills for struggling older readers. Learning Disability Quarterly, 26(2), 89-101.

Armbruster, B., Lehr, F., & Osborn, J. (2001). The research building blocks for teaching children to read: Put reading first.

August, D., McCardle, P., & Shanahan, T. (2014). Developing Literacy in English Language Learners: Findings From a Review of the Experimental Research. School Psychology Review , 43 (4), 490-498.

Camahalan, F. M. G., & Wyraz, A. (2015). Using Additional Literacy Time and Variety of Reading Programs. Reading Improvement , 52 (1), 19-26.

Denton, C., Bryan, D., Wexler, J., Reed, D., & Vaughn, S. (2007). Effective Instruction for Middle School Students with Reading Difficulties.

Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2014). Close reading as an intervention for struggling middle school readers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 57 (5), 367-376.

Ford, K. (n.d.). ELLs and Reading Fluency in English. Retrieved April 08, 2016, from http://www.colorincolorado.org/article/ells-and-reading-fluency-english

Francis, D. J., Rivera, M., Lesaux, N. K., Kieffer, M. J., & Rivera, H. (2006, October). Practical guidelines for the education of English language learners. In Presentation at LEP Partnership Meeting, Washington, DC. Available for download from http://www.centeroninstruction.org .

Geva, E., & Farnia, F. (2012). Developmental changes in the nature of language proficiency and reading fluency paint a more complex view of reading comprehension in ELL and EL1. Reading and Writing , 25 (8), 1819-1845.

Goldenberg, C. (2008). Teaching English language learners. American Educator .

Hasbrouck, J. (2006). For Students Who Are Not Yet Fluent, Silent Reading Is Not the Best Use of Classroom Time. American Educator , 30(2).

Kuhn, M. R., Schwanenflugel, P. J., and Meisinger, E. B. (2010). Aligning Theory and Assessment of Reading Fluency: Automaticity, Prosody, and Definitions of Fluency. Reading Research Quarterly , 45(2), 230–251.

Maddox, K., & Feng, J. (2013). Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students. Online Submission .

Meyer, M. S. and Felton, R. H. (1999). Repeated reading to enhance fluency: Old approaches and new directions. Annals of Dyslexia , 49, 283–306.

Morris, D., & Gaffney, M. (2011). Building Reading Fluency in a Learning‐Disabled Middle School Reader. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 54 (5), 331-341.

National Reading Panel (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Paige, D. D., & Magpuri-Lavell, T. (2014). Reading Fluency in the Middle and Secondary Grades. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education , 7 (1), 83.

Paige, D. D., Rasinski, T. V., & Magpuri‐Lavell, T. (2012). Is fluent, expressive reading important for high school readers?. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 56 (1), 67-76.

Pikulski, J. J., & Chard, D. J. (2005). Fluency: Bridge between decoding and reading comprehension. The Reading Teacher, 58(6), 510-519.

Rasinski, T. (2013). Supportive Fluency Instruction: The Key to Reading Success.

Rasinski, T. (2006). Reading Fluency for Adolescents: Should We Care? Retrieved April 08, 2016, from http://ohiorc.org/adlit/inperspective/issue/2006-09/Article/feature.aspx

Rasinski, Tim (2006). Reading fluency instruction: Moving beyond accuracy, automaticity, and prosody. The Reading Teacher , 59(7), 704–706.

Rasinski, T. & Burns, M.S. (2014). Brain science and reading instruction .

Rasinski, T. V., Padak, N. D., McKeon, C. A., Wilfong, L. G., Friedauer, J. A., & Heim, P. (2005). Is reading fluency a key for successful high school reading? Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy , 22-27.

Rasinski, T. V., Reutzel, D. R., Chard, D., & Linan-Thompson, S. (2010). 13 Reading Fluency. Handbook of reading research , 4 , 286.

Rasinski, T., Homan, S., & Biggs, M. (2009). Teaching reading fluency to struggling readers: Method, materials, and evidence. Reading & Writing Quarterly , 25 (2-3), 192-204.

Rasinski, Tim (March 2004). Creating Fluent Readers. Educational Leadership , 61(6).

Stahl, S. A. (2004). What Do We Know About Fluency? Findings of the National Reading Panel.

Topping, K. J. (2014). Paired Reading and Related Methods for Improving Fluency. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education , 7 (1), 57.

Walpole, S., & McKenna, M. C. (2012). Literacy Coach's Handbook: A Guide to Research-Based Practice . Guilford Press.

White, T. G., Sowell, J., & Yanagihara, A. (1989). Teaching elementary students to use word-part clues. The Reading Teacher, 42(4), 302-308.

Whithear, J. (2011). A review of fluency research and practices for struggling readers in secondary school. Literacy Learning: The Middle Years , 19 (1), 18.

Wolf, M. (2013). New Research on an Old Problem: A Brief History of Fluency | Scholastic.com Retrieved April 08, 2016, from http://www.scholastic.com/teachers/article/new-research-old-problem-brief-history-fluency .

[1] http://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading_math_2015/#reading

- Our Mission

A 3-Step Strategy to Build Students’ Reading Fluency

Young readers learn how to self-direct when they read in pairs, read the same text repeatedly, and use fluency trackers.

Fluency is often discussed by elementary teachers simply as the rate of words read aloud per minute, although the full definition includes reading accuracy plus voice tone and inflection. It’s an important measure of student reading success, and as students move through grades, poor fluency becomes increasingly serious. To raise fluency levels, students need to practice reading in short bursts of effort, and they need to practice word attack skills that are used for frustration-level text , in which more than one out of 20 words are difficult to decode.

Independent reading is one way to help students build fluency, but we all know that they’re not necessarily going to focus if you simply hand them a book and tell them to read it. I’ve found that if I combine repeat reading, paired reading, and fluency trackers, students are more motivated to do that crucial work that builds fluency.

Building Fluency in the Classroom

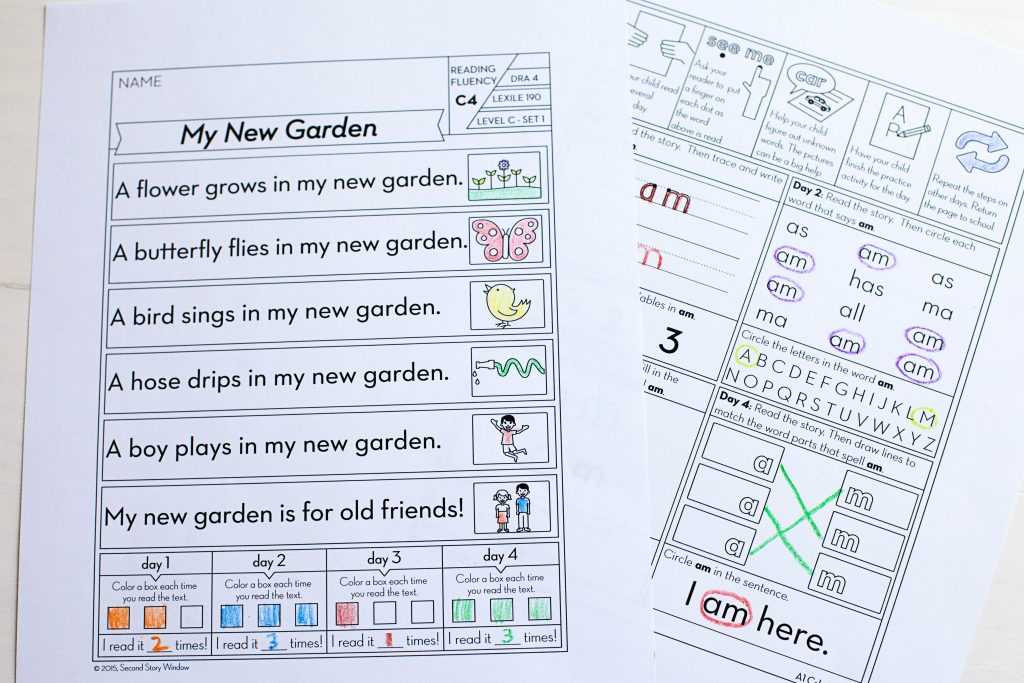

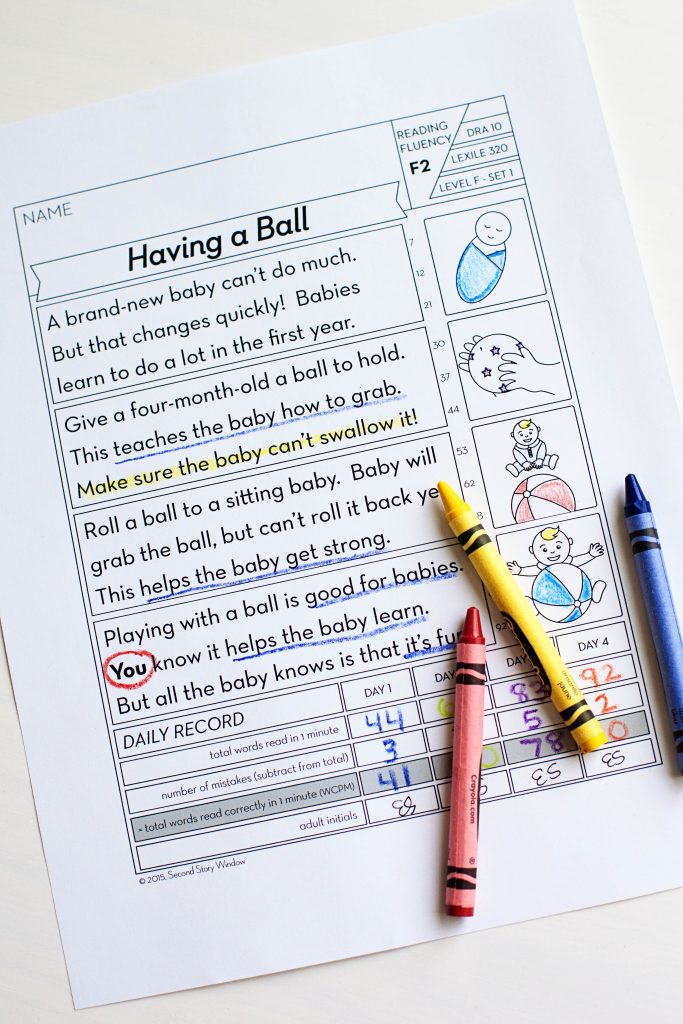

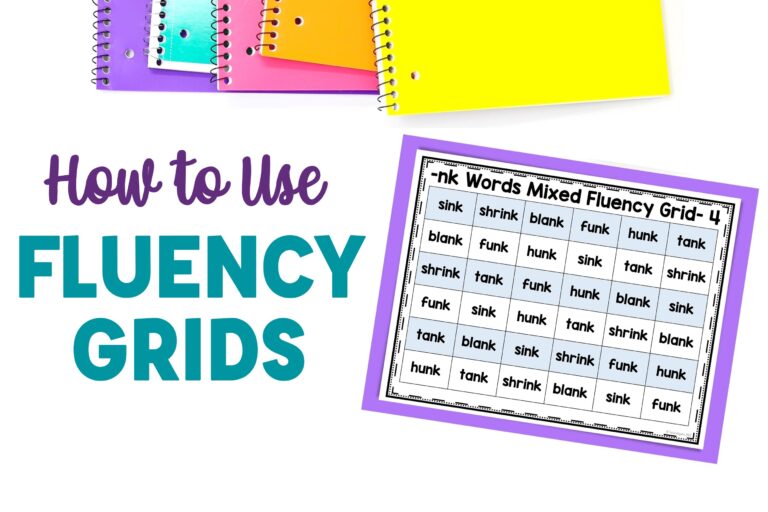

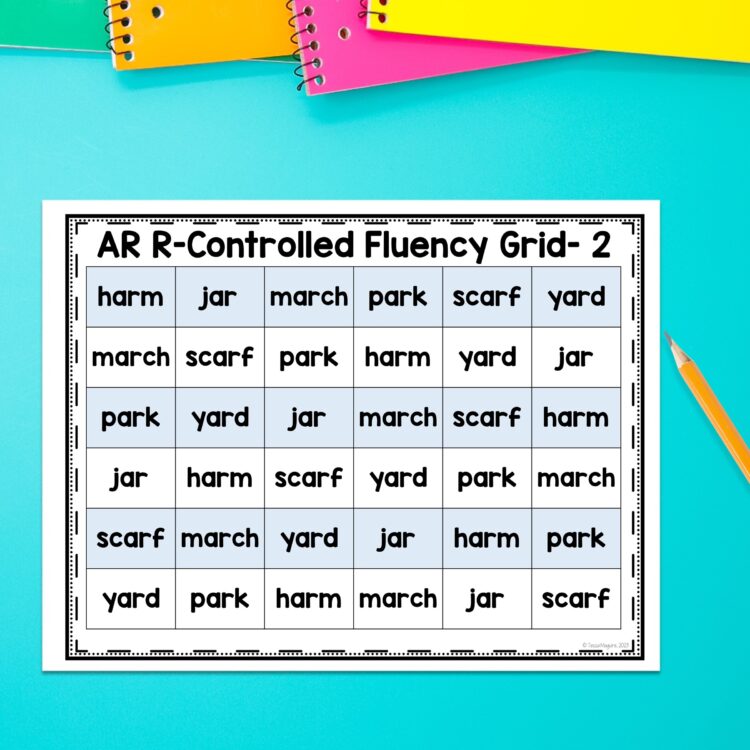

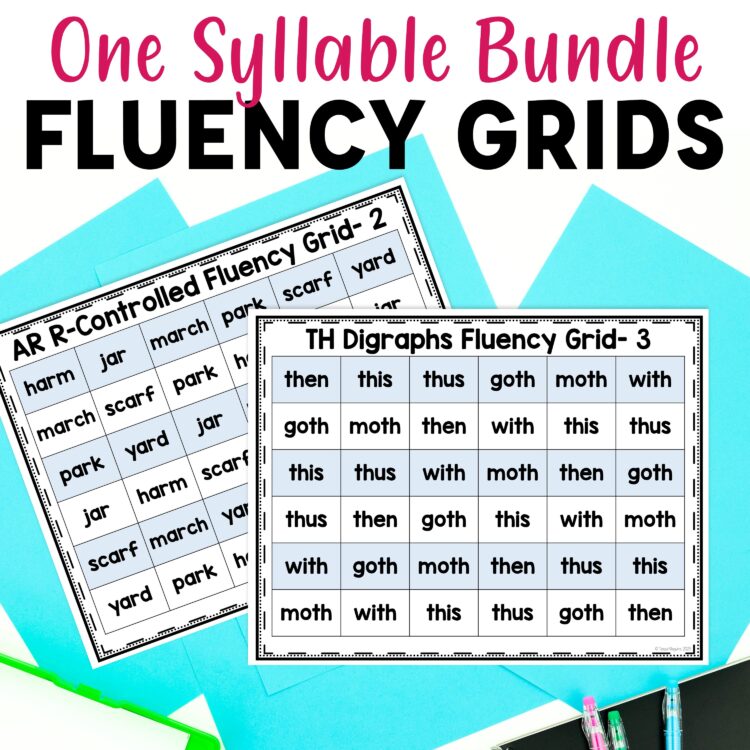

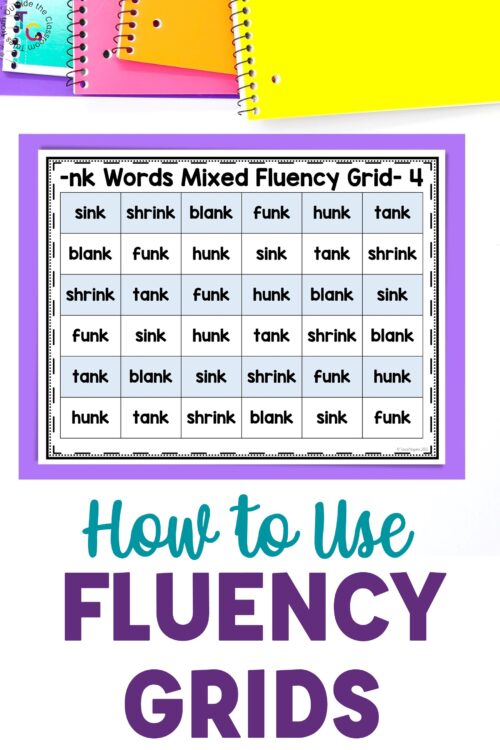

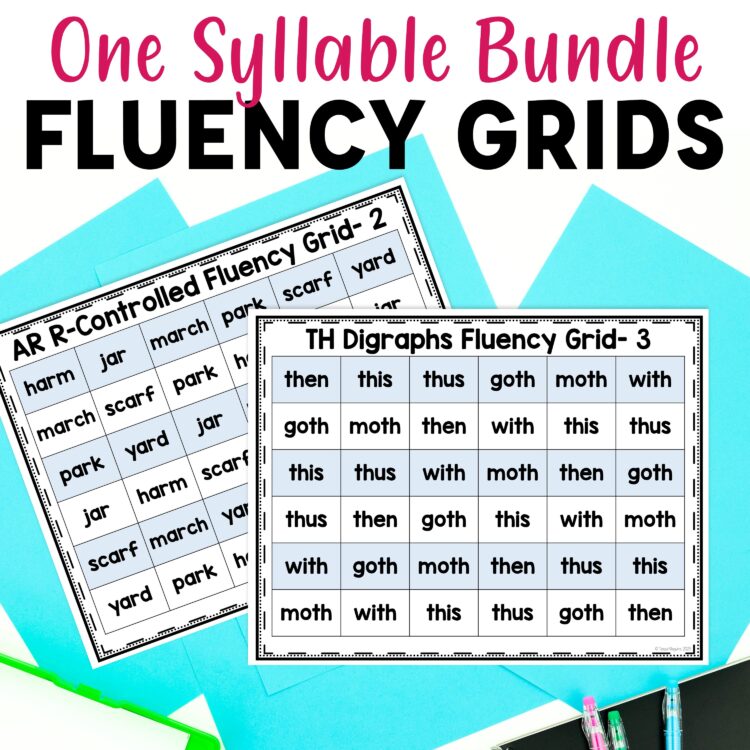

In my teaching practice, I’ve long relied on two strategies to support my students’ literacy growth: repeated reading and fluency trackers (grids on which students record their fluency scores over time). Reading a passage multiple times (repeated reading) scaffolds the student’s ability both to decode and to remember familiar words and syllable patterns, building their fluency and comprehension; and fluency trackers give students agency and motivate them while giving me a quick read on their progress. When integrating repeated reading with fluency trackers, I often use a one-page passage: Students read the passage three times, graphing each attempt (first, second, and third) with a different-colored crayon.

That combination has always served me well, but once I added in a third component—paired reading—I noticed that not only did the atmosphere in the classroom get a boost, but engagement improved and students got their work done more readily. Repeated reading gives them the practice and reinforcement they need to build their literacy skills, the pairing creates a positive social element, and the fluency trackers simultaneously help them to self-direct, see their progress, and stay on track while working in pairs, when socializing is tempting.

Steps to Fluency Tracker Practice

Create a tracker folder for each student: Use a letter-size manila folder, and staple in a data tracker for fluency scores. (You can find fluency trackers in a number of places, such as these free ones , or you can create your own using graph paper.)

Locate and print out reading passages: Find passages that are somewhere between the student’s instructional and frustrational reading level. Often, reading passages of this type are available in the support materials to the grade-level reading program at your school. You’ll need two copies of each passage for each pair: one for the student reading and one for the listener/scorer.

Pair the students: Match students who read at about the same level. Consider sociability and distractibility as well. If one student is volatile or touchy, put them with a classmate who has a calm, steady personality.

Model paired reading and fluency tracker record keeping: To model fluency tracking, gather the class in a circle so they can watch you and a student as the two of you go through the process of doing a timed fluency reading. Set a timer and have the model student begin reading. After a minute, stop the timer, count the words, report the score to the student, and have the student record the result on the fluency tracker.

Send the students out to practice: After giving the students the names of their partners, review the behavior norms (voice level, where they are to sit, how to get help) and direct them to try using their fluency trackers themselves.

Debrief and continue to practice: Once your students have tried paired reading and fluency tracking, bring them together to answer questions and work out the kinks—for example, “Did anyone have trouble using the timers?” While they are working, walk around the class to see how the students are reading and to make sure they stay on task. Eventually, they will require minimal supervision.

Give students the opportunity to set their own goals: Make the goals specific; allow them to be personal, not public; and include a time for reaching the goal. Appropriate goals might be reaching a certain level of fluency (“I’ll be able to read 60 words a minute by the first of the next month”) or accuracy (“I’ll read for one minute with two errors or less by winter break”).

Once you’ve landed on a routine for fluency trackers, schedule them regularly for 10 to 15 minutes at a time.

I used this strategy with a small group of second graders this spring, and three out of four students made significant gains in speed over four months with daily practice, while half of them doubled their reading speed. A colleague used fluency trackers with fourth graders who were reading significantly below grade level; in a group with a dozen or so students, all made significant fluency gains—and they enjoyed the activity. “They love it!” she told me. “When it’s time for fluency, they jump up to get their folders and get to work. It’s wonderful.”

The Fluency Development Lesson (FDL): Synergistic Fluency Instruction

by Timothy Rasinski, PhD

January 5, 2023

Reading fluency is the ability of readers to read words in text automatically and with a level of expression and phrasing that reflects the meaning of the text. Since the publication of the report of the National Reading Panel (2000), reading fluency has been recognized as a critical competency for success in reading. It is often viewed as a bridge between phonics or word decoding and comprehension. Research indicates that many children who struggle in reading have not adequately crossed that fluency bridge – and, as a result, comprehension and overall reading proficiency suffer (White, et al., 2021).

Key elements of fluency instruction include modeling fluent reading (read aloud to students), assisted reading (students read a text while simultaneously hearing the same text read to them by a partner, group, or recording), wide reading (students read a text one time and then move on to a new text), and deep or repeated reading (students read one text multiple times until they are able to read it with a degree of fluency). Research has shown that each of these instructional tools can promote fluency as well as improve overall reading proficiency. Typically, teachers focus on fluency by either focusing primarily on one or two of these instructional strategies, or, over the course of multiple days, tap into a different strategy each day.

Given that fluency is often neglected (often in lieu of additional phonics instruction) and because so many of our struggling readers exhibit significant difficulties in fluency, it may be helpful to think of fluency instruction synergistically. By synergistic fluency instruction I mean a regular instructional routine that contains all the elements of fluency instruction mentioned previously. In this way, the benefits from each of these instructional elements interact with one another to produce an effect together than they would if used individually – the whole being greater than the sum of the parts.

The Fluency Development Lesson (FDL) is one such synergistic approach to systematic, direct, and intensive fluency instruction. The FDL is a single lesson that employs short reading passages (poems, story segments, or other texts of between 50-200 words) that students read and reread over a short period of time. The goal of each Fluency Development Lesson is for students to achieve success in reading the text for that lesson. The general format for each 20-minute lesson follows:

- Students read a familiar passage from the previous lesson to the teacher or a fellow student for accuracy and fluency.

- Model Fluent Reading. The teacher introduces a new short authentic text and reads it to the students two or three times while the students follow along. The text can be a poem, song, or a short story segment, etc.

- Model Fluent Reading. The teacher and students discuss the nature and content of the passage as well as how the teacher read the text. If the teacher reads the text to students multiple times, she may wish to make one or more of her readings less-than-fluent in order to invite comparisons with more fluent readings.

- Assisted Reading. The teacher and students read the passage chorally several times – whole group reading, antiphonal reading (breaking a poem into parts for different students or groups), and other variations of choral reading are used to create variety and maintain engagement.

- Repeated Reading. The teacher organizes groups of 2 or 3. Each student then practices the passage two to three times while the partner(s) listens, follows along, and provides support and encouragement.

- Repeated Reading. Individuals and groups of students perform their reading for the class or other audience. That audience may just be a parent or two sitting outside the classroom listening to each student and providing positive feedback.

- Word Study. The students and teacher choose 4 to 10 words of interest from the text to add to personal word banks and/or to the classroom word wall. The words are then read (and continue to be read regularly over the following few days.)

- Word Study. Students engage in a brief period of word study activities with the words (e.g., word sorts, examination of and expansion of word families, flash card practice, word meanings, words, word games, etc.

- Repeated Readings. Students take a copy of the passage home to practice with and perform for parents and other family members.

- Students return to school the following day and read the passage to the teacher or a partner who checks for fluency and accuracy.

- Repeat the lesson daily or as often as possible using different texts for each new lesson.

As you can see in the above overview, each lesson contains fluency (and other) instructional components. Done on a regular basis (3-5 times per week), the results of using the FDL can be significant and substantial. Indeed, the National Reading Panel (2000) identified the FDL as a promising approach for improving fluency in struggling readers. In one study of fourth-grade struggling readers provided the FDL over four months, these struggling readers made twice the gain in reading fluency (words read correct per minute) and nearly three times the gain in comprehension over what would be normally expected (Disalle & Rasinski, 2017). In our own university summer reading clinic for struggling elementary and middle grade students, we have found consistent gains, well above what would normally be expected, for word recognition, fluency, and comprehension (Zimmerman, et al., 2019). Indeed, a systematic review of fluency interventions such as the FDL used with learning-disabled students found that regular implementation of such interventions produced gains in both fluency and comprehension. Indeed, in a review of studies of fluency interventions on learning-disabled students, Stevens, Walker, and Vaughn (2017) found that multi-component interventions such as the FDL produce gains in fluency and comprehension for struggling readers.

The goal of any reading instruction routine or intervention is improvement in comprehension and overall reading proficiency. In as much as reading fluency is the bridge from word decoding to comprehension, and significant numbers of our struggling readers fail to cross that bridge, fluency interventions such as the FDL offer great promise for improving reading outcomes for the students we worry the most about.

DiSalle, K., & Rasinski, T. (2017). Impact of short-term fluency instruction on students’ reading achievement: A classroom-based, teacher-initiated research study. Journal of Teacher Action Research, 3, 1-14.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read. Report of the subgroups . Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health.

Rasinski, T. V. (2010). The Fluent Reader: Oral reading strategies for building word recognition, fluency, and comprehension (2 nd edition) . New York: Scholastic.

Rasinski, T., & Cheesman Smith, M. (2018). The Megabook of Fluency . New York: Scholastic (Winner of the 2019 Teachers’ Choice Award for the classroom).

Rasinski, T., & Young, C. (2023). Build Reading Fluency: Practice and Performance (2 nd edition). Huntington Beach, CA: Shell Education.

Stevens, E., Walker, M., & Vaughn, S. (2017). The effects of fluency interventions on the reading fluency and reading comprehension performance of elementary students with learning disabilities: A Synthesis of the research from 2001-2014. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 50 , 576-590.

White, S., Sabatini, J. Park, B., Chen, J., Bernstein, J., and Li, M. (2021). The 2018 NAEP Oral Fluency Study. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

Zimmerman, B.S., Rasinski, T.V., Kruse, S.D., Was, C.A., Rawson, K.A., Dunlosky, J., & Nikbakht, E. (2019). Enhancing outcomes for struggling readers: Empirical analysis of the fluency development lesson, Reading Psychology, 40 (1), 70-94.

Timothy Rasinski is a professor of literacy education at Kent State University and director of its award winning reading clinic. He also holds the Rebecca Tolle and Burton W. Gorman Endowed Chair in Educational Leadership. Tim has written over 250 articles and has authored, co-authored or edited over 50 books or curriculum programs on reading education. He is author of the best selling books on reading fluency The Fluent Reader and The Megabook of Fluency. Tim’s scholarly interests include reading fluency and word study, reading in the elementary and middle grades, and readers who struggle. His research on reading has been cited by the National Reading Panel and has been published in journals such as Reading Research Quarterly, The Reading Teacher, Reading Psychology, and the Journal of Educational Research. Tim is the first author of the fluency chapter for the Handbook of Reading Research, Volume IV. Tim served a three year term on the Board of Directors of the International Reading Association and was co-editor of The Reading Teacher, the world’s most widely read journal of literacy education. He has also served as co-editor of the Journal of Literacy Research. Rasinski is past-president of the College Reading Association and he has won the A. B. Herr and Laureate Awards from the College Reading Association for his scholarly contributions to literacy education. In 2010 Tim was elected to the International Reading Hall of Fame and he is also the 2020 recipient of the William S. Gray Citation of Merit from the International Literacy Association. In a 2021 study done at Stanford University Tim was identified as being among the top 2% of scientists in the world. Prior to coming to Kent State Tim taught literacy education at the University of Georgia. He taught for several years as an elementary and middle school classroom and reading intervention teacher in Omaha, Nebraska. Tim is a veteran of the United States armed forces.

More Resources for Supporting Literacy

Explore our the Free Teaching Strategies and blog posts related to reading acquisition

Recommended For You

Supporting Students in Developing Automatic Word Recognition

Poetry in the Age of Science of Reading

Using a Decoding Toolkit to Develop a Common Language

Support your students with sld.

Receive free teaching resources, information about professional development opportunities, and alerts about promotions

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Check Out Our Blog

A blog for busy teachers.

Learn about our new updated blog format that will combine our monthly newsletter and Free Teaching Strategies into one resource!

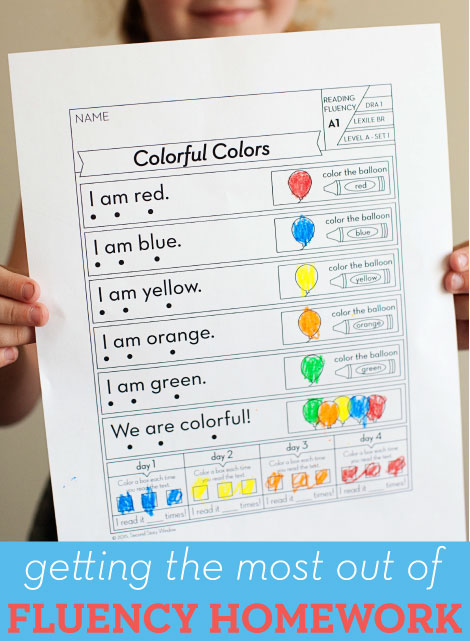

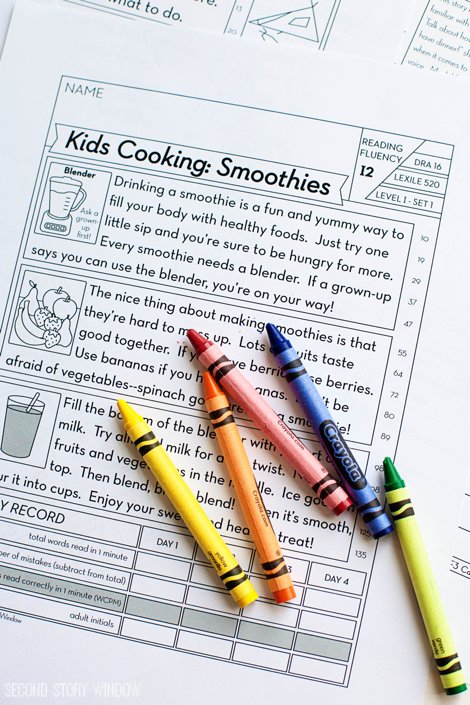

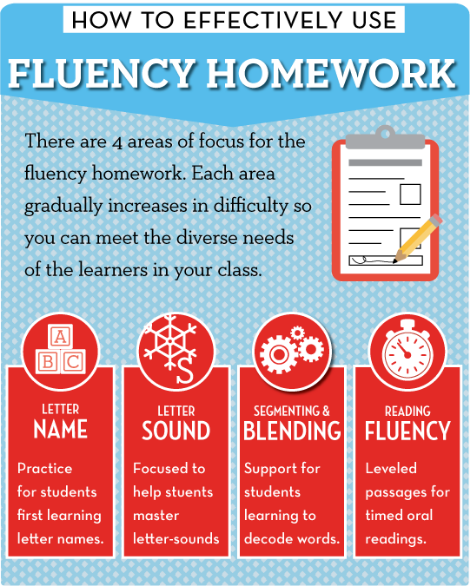

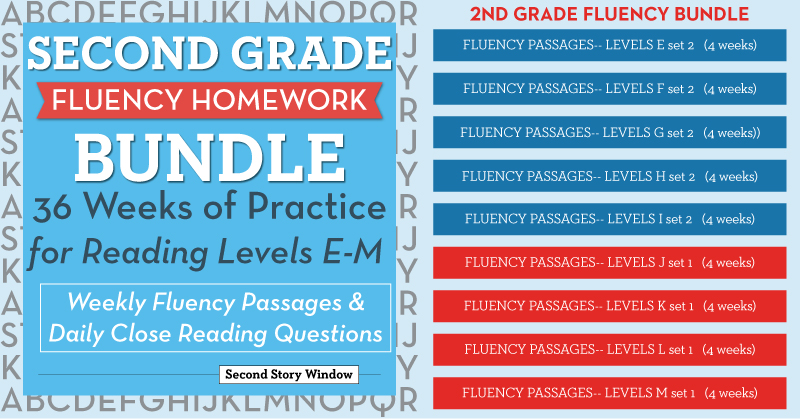

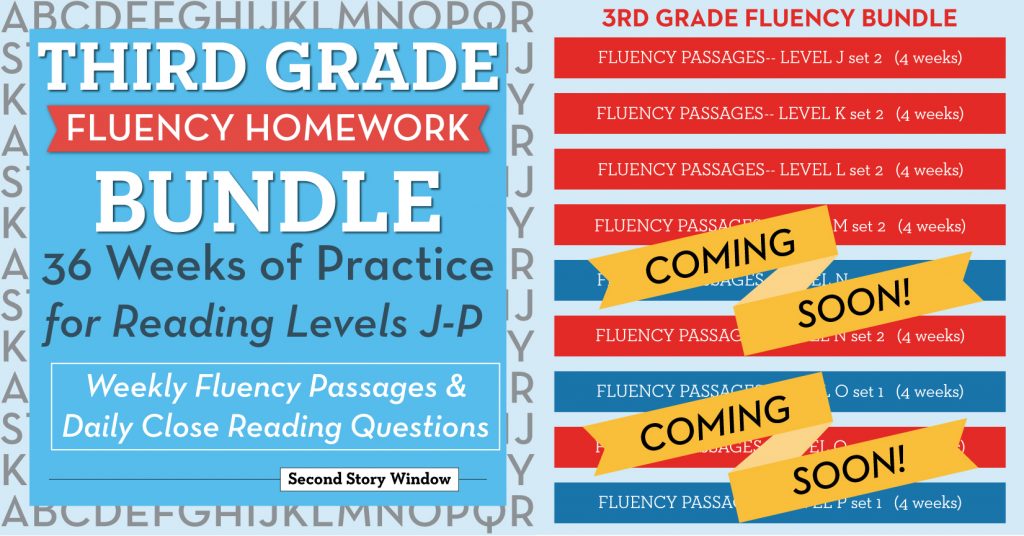

Getting the Most Out of Fluency Homework

Timed, repeated readings with feedback are one of the best ways to improve students’ reading fluency.

Read more about repeated readings here!

How you manage repeated readings depends on what works best in your class. Some teachers have parent helpers or aides work with the students. Some teachers do timed readings as part of individual reading conferences. Some teachers have students read along with audio recordings.

Find what works for you!

For us, what worked best was assigning repeated readings as fluency homework.

How Does Fluency Homework Work?

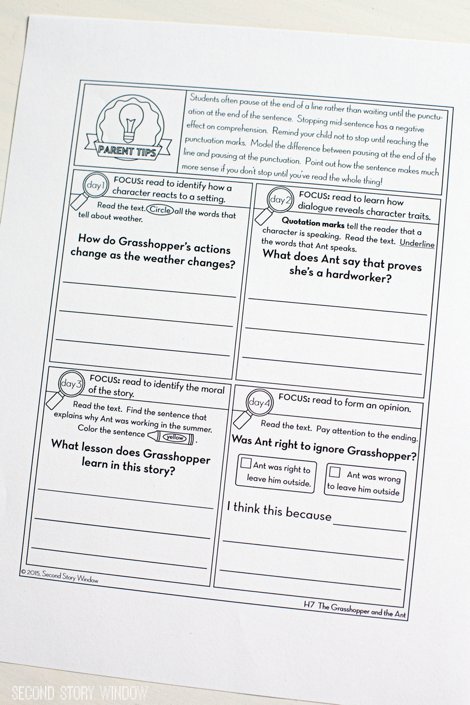

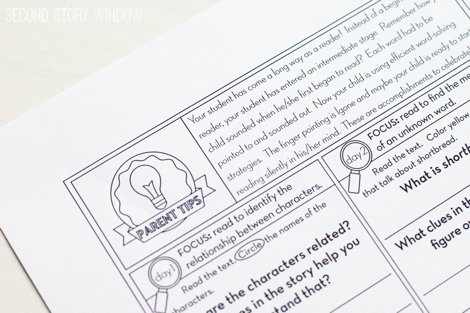

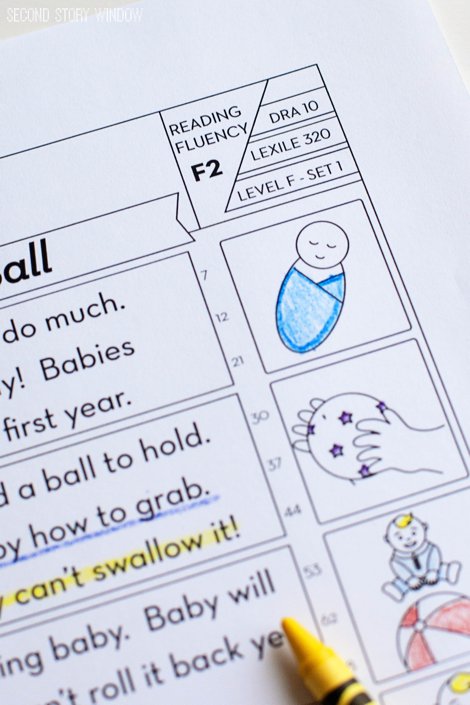

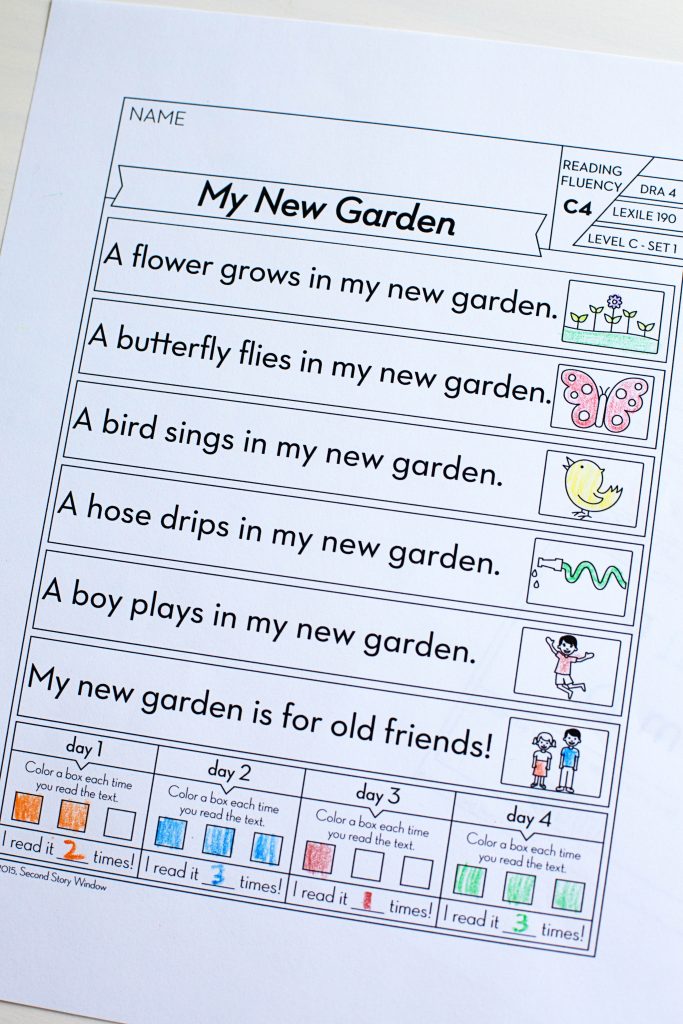

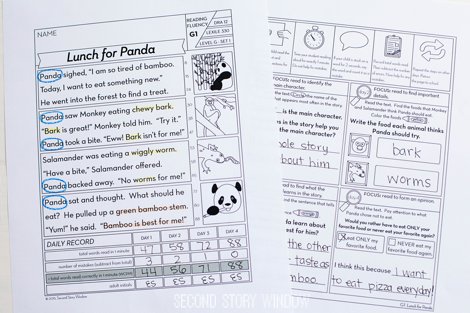

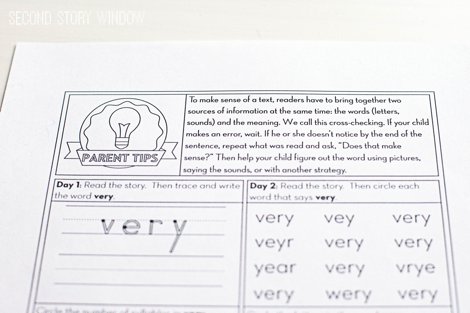

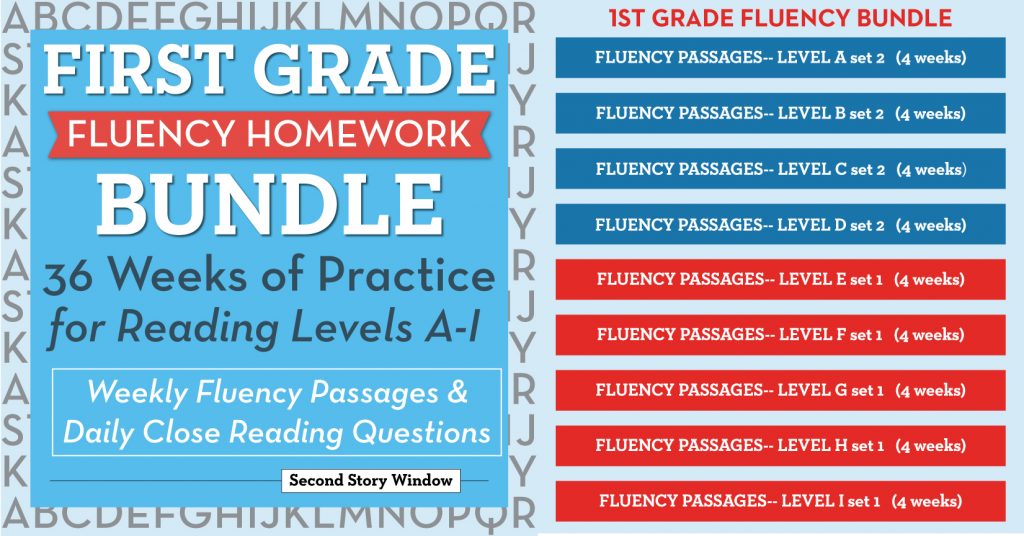

I send each student home with a passage on Monday. Most of my kids get the same passage, but I differentiate for my highest and lowest readers. (You can differentiate for each individual reader if you have the time/patience!) Students read the same text for 4 days. For the lower reading levels (A-D, kindergarten and part of 1st grade) students color a box after each complete reading. It’s not appropriate to time them at this stage in their development. Starting on Level E, they’re timed reading for 1 minute and parents find their WCPM.

The reading passage is on the front. The daily assignments are copied on the back. Because we want to connect fluency with greater comprehension , from levels E and up students have a specific comprehension focus each day (levels A-D focus on sight words). In a format that models close reading, the questions get progressively complex.

The key to making this assignment effective is to provide parent support . Parents need to know how to give feedback. Each week’s assignment has tips for how parents can make the most of the homework . Some of it is general information on how to do the assignment or why reading fluency is important. Some of the tips are related to that week’s particular story. For example, how to read dialogue or how to give a character a unique voice. Like the questions, the tips are related to the text.

Organization tip: make a stack of copies ahead of time for each level and store them in file folders. When it’s time to send home practice, use a check list to quickly pull fluency pages from your files.

What Makes Fluency Homework Worthwhile?

In the post about leveled passages (find it here ), I wrote about how to find quality texts for reading. I set out 5 guidelines for recognizing quality:

- It’s leveled

- It’s brief

- It uses sight words

- It covers a variety of genres

- It fosters deeper comprehension

These are the guidelines we used when creating our fluency passages .

- Is it leveled? It is leveled according to Guided Reading level. You will find the leveling information in the top corner. Estimated DRA and Lexile details are also included.

What does Level A look like? • designed to help develop concepts of print • short, predictable sentences • illustrations that support meaning • simple narratives and familiar themes

What does Level B look like? • short, predictable sentences • repetitive stories with familiar themes • illustrations that closely match print • text in a large, plain font

What does Level C look like? • predictable text with longer sentences, but still on a single line • illustrations that match print, but offer less support • greater range of high frequency words

What does Level D look like? • increasing number of lines of text per page • less repetition • some words in bold for emphasis • word-solving strategies may be required to understand meaning • simple dialogue

What does Level E look like? • more complex stories with subtler meanings • sentences that carry over to multiple lines • simple and split dialogue • large number of high-frequency words

What does Level F look like? • stories with greater development of plot and character • non-fiction texts are focus on a single idea • longer sentences • illustrations that support text, but don’t carry all the meaning • greater range of vocabulary

What does Level G look like? • more complex stories and ideas • wider variety of settings, characters, and vocabulary • includes plurals, possessives, and contractions • longer dialogue

What does Level H look like? • stories that run longer than 100 words • humorous situations and a wider variety of themes • dialogue that adds to the drama • a variety of words used to assign dialogue to readers (explained, told, etc.) • many words with inflectional endings • complex illustrations and text features

What does Level I look like? • several sentences longer than 10 words • prepositional phrases, adjectives, and clauses • abstract themes supported by the text and illustrations • stories that require inference

Levels J+ are still under construction.

- Is it brief? All the stories in these passages fit on a single page. For lower levels, it uses a large type with plenty of space between lines.

- Does it use sight words? In the early levels (A-D) students are introduced to a sight word that is used repeatedly in the passage. They also practice the word in multiple ways over the course of a week. From level E and up, the focus is less on high-frequency words and more on comprehension. However, the text is full of sight words and no more than one vocabulary word is introduced per passage. Character names are short and decodable. There are no difficult proper nouns or dates in the transitional level passages (E-K).