Capstone Form and Style

Scholarly voice: tone and audience, tone and audience.

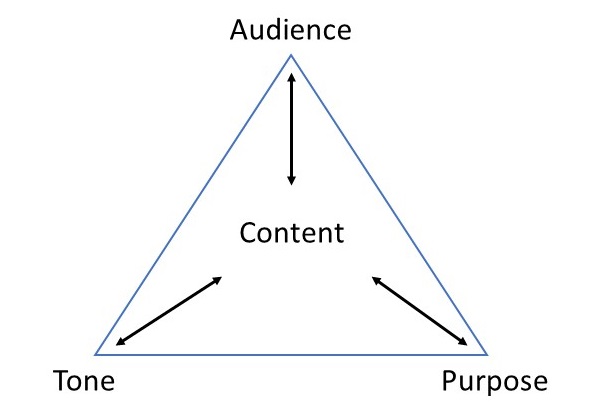

The concepts of tone and audience are interwoven with many topics addressed throughout the Scholarly Voice pages. The purpose of this page is to define these concepts as they relate to writing, APA style, and capstone documents.

Basics of Tone

Tone refers to the attitude a writer conveys toward the subject matter and the reader. The tone of a document can affect how the reader perceives the writer’s intentions. These perceptions, in turn, can influence the reader’s attitude toward the text and the writer. To strike the right tone, writers should be mindful of the purpose and audience for their work when making decisions about word choice, sentence structure , and specificity of information.

Tone in APA Style

In APA style, the tone (see APA 7, Section 4.7) should reveal a writer’s attitude as interested but neutral and professional. Writers should present information and arguments in an engaging but objective manner and choose courteous and respectful language when providing critical analysis of the work of past researchers.

Discourteous: However, the researchers completely neglected to consider. . .

Neutral: However, the researchers did not address. . .

Discourteous: Jones (2018) missed the point about. . .

Neutral: Jones (2018) did not mention. . .

In the above examples, the first version appears to reveal assumptions and judgments about the previous researchers’ intentions or abilities. The revised versions present the same criticism but without the subjective and unduly harsh tone.

Tone in Capstone Writing

Capstone writers may have strong feelings or opinions about the problems they are addressing through their research. However, revealing personal attitudes through a subjective tone can make writers appear to take sides (e.g., in defense of the population they seek to help). In the spirit of scientific objectivity and professionalism, capstone writers should rely on compelling evidence and analysis rather than emotional appeals. Readers of APA-style writing expect logical, evidence-based arguments and critical but respectful discussion of previous research, and they may perceive emotionally charged, hyperbolic, or seemingly biased language as less credible.

Certain words (e.g., unfortunately, clearly, heartbreaking, amazing, etc.) can reveal a subjective attitude and seem to impose the writer’s opinion instead of allowing readers to form their own opinions based on the presented information. Generally, such words can be omitted without taking away from the substance of the sentence.

Subjective: Unfortunately, researchers have found that many health professionals lack the necessary health literacy awareness, knowledge, and skills.

Objective: Researchers have found that many health professionals lack the necessary health literacy awareness, knowledge, and skills.

Basics of Audience

The fundamental purpose of writing is to communicate ideas to other people—an audience . To do this effectively, writers should consider questions such as the following before and during the writing process:

- Who are the intended or likely readers for the document?

- What do these readers want and/or expect from the writer and from the text?

- What level of background knowledge do the readers probably have related to the subject matter?

Answering these questions can help writers see the document from the viewpoint of the prospective audience and decide what to write and how to write it—that is, the content of the text and the form, style, and tone of that content.

Audience for APA Style

Readers tend to approach a text with certain expectations based on their prior experience with texts in the same genre. Because of the emphasis in APA style on precision and clarity, readers have generally come to expect APA-style research writing to be clear, efficient, and logically organized, and they expect specific, credible information that is reported in a straightforward, unbiased manner. In other words, they expect clarity, objectivity, specificity, economy of expression, and professionalism. To communicate effectively with an APA-minded audience, writers should work to meet these expectations.

Audience for Capstone Writing

A capstone document shares many traits with research articles published in journals. However, because capstone writers are both student and researcher, they need to bear in mind two levels of audience: a smaller immediate audience and a somewhat broader eventual audience.

Capstone writers’ immediate audience includes their committee, the URR, and the CAO, who evaluate the document and determine whether or when it moves forward in the capstone process. These readers serve in some ways as a trial audience, providing feedback to ensure that the document is ready for the larger audience. However, they have some capstone-specific expectations. For example, because capstone students are in the process of demonstrating their readiness to conduct research independently, faculty expect them to display mastery of certain research concepts or processes with a level of specificity that would be unnecessary in an article published in a journal.

The larger audience, at whom the bulk of the capstone document’s message is aimed, consists of interested researchers and professionals in the student’s field and related fields—in other words, the writer’s professional and academic peers. Capstone writers should keep this audience in mind throughout the writing process. Following the advice of faculty, the program checklist or rubric, and the guidelines in the APA manual will help capstone writers convey their message to these eventual readers.

Summary of Tone and Audience for the Capstone

A capstone document marks a writer’s debut as a member of a community of scholars. The attitude conveyed in this document necessarily reflects the position of a person displaying an understanding of certain research concepts and writing conventions while also contributing something new to the literature. By adopting an objective and professional tone and keeping the audience in mind, a writer can demonstrate awareness of and respect for other members of the scholarly community and ensure that readers are able to focus on the substance of the document.

- Previous Page: Home

- Next Page: Avoiding Bias

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Tone, Mood, and Audience

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When thinking about proper diction, an author should consider three main categories: tone , mood , and audience .

Audience refers to who will be reading the work. Authors tend to write to a particular audience, whether kids, or young adults, or specialist within a field. The audience can affect the mood and tone of the writing because different audiences have different expectations. Tone refers to the author’s attitude—how they feel about their subject and their readers. It expresses something of the author’s persona, the aspects of their personality they wish to show to their readers. For example, are they being funny or serious? Are they writing with fondness or with derision ? Mood refers to the overall atmosphere or feeling of a piece of writing. It is often closely related to tone, because the author’s attitude influences the overall feeling of a text. It’s difficult, for instance, to take a jovial tone if the overall mood of the piece ought to be somber, or vice versa. Wuthering Heights by Emily Bront ë would be far less effective as a gothic text if its spooky atmosphere was interrupted by witty , sarcastic commentary in the style of Jane Austen .

Take, for example, this qu ote from Wuthering Heights :

Th is passage displays heightened emotions and dark themes through the use of words like “ghost,” “haunt,” a nd “abyss,” among others. Consider how much less effective this p assage would be if the narration sounded like Pride and Prejudice : “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

Using the appropriate kind of descriptive words, including imagery , or vivid language used to paint a mental picture, can convey mood and tone by helping readers get a clearer sense of what they’re reading about and how the author thinks and feels about the subject, and thus what they’re supposed to think and feel.

Diction can help authors make audiences feel a certain way, like in the example above. Similarly, different styles of diction may be targeted at different audiences— there’s a good reason Wuthering Heights is aimed at teenagers and adults rather than young children, for instance. In addition to the content of the text, the elevated and somewhat antiquated diction would make it very challenging for younger audiences to understand. Conversely, a paper aimed at an audience of academic experts would probably be expected to use more jargon and complicated diction.

Take, for example, this simplistic description of Pluto’s orbit from Astronomy.com’s Astronomy for Kids educational resource:

Compare this language with the highly techni cal language used in an Encyclopedia Britannica article on Pluto :

These texts, while essentially saying the same thing, are using wildly different language due to the disparity between their intended audiences.

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Online Guide to Writing and Research

Thinking strategies and writing patterns, explore more of umgc.

- Online Guide to Writing

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone

While reading, have you ever felt as though an author was talking to you inside your head? Perhaps you felt this sensation while reading a social media post, an article, or even a book. Writers achieve the feeling of someone talking to you through style, voice, and tone. Mastering these will help your readers know how to feel about your writing and help you communicate in a way that is unique to you.

- APPLICATION

In popular usage, the word “style” means a vague sense of personal style, or personality. Applied to writing, “style” does have this connotation—especially in fiction. However, style in writing has a more formal and unique meaning, too. Applied to writing, “style” is a technical term for word patterns that create a certain effect on readers.

If a piece of writing reflects a consistent choice of patterns, then it feels coherent and harmonious. This coherence and harmony can be quite pleasing for readers, and writers aspire to it. However, writers do not always choose a style. Rather, context, content, and purpose dictate the style a writer should use.

For example:

Genre will dictate a fiction writer’s style. Specific academic disciplines will dictate style for an academic writer. Both genre and discipline have stylistic conventions that writers take into account when creating a written work. When writing, pay close attention to the genre and discipline in which you are writing.

When writers speak of style in a more personal sense, they often use the word “voice.” When you hear an author talking inside your head, “voice” is what that author sounds like.

Of all the writerly qualities, voice is the most difficult to analyze and describe. Most writers have difficulty expressing what their voice is and how they achieved it, though most will allow their voice developed over time and after much practice. Still, there are qualities that, when identified and practiced, can help you develop your own voice.

Look closely at professional writing, and you may notice a certain rhythm or cadence to it. This rhythm is an element of voice.

Read a number of works from the same author, and you may notice common word choices, perhaps not the same words, but similar words or word patterns. Word choice (also called “diction”) is an element of voice.

Punctuation

You may also notice that some authors come across as flamboyant while others come across as blunt or assertive. Still others may come across as always second-guessing themselves, adding qualifications and asides to their statements. An author often achieves these qualities through carefully placed punctuation, another element of voice.

To assert your own personal writing style, practice rhythm and cadence, pay careful attention to word choice and develop an understanding of how punctuation can be used to express ideas.

Even when indulging their own voices, authors must keep in mind context, content, and purpose. To do this, they make adjustments to their voices using “tone.”

Tone is the attitude conveyed by an author’s voice. We use two general distinctions when discussing tone: informal and formal.

An Informal Tone

Ever read something, and your heart swells with pride? Or maybe you get angry, or you get scared. Write informally, and you’ll use emotions - big ones. You’ll use contractions, too. A lot of times, when you write informally, you talk about yourself and use the first-person pronoun (I). Sometimes you talk to the reader and use the second-person pronoun (you). An informal tone sounds conversational and familiar like you do when you talk with a friend.

A Formal Tone

When using a formal tone, authors avoid discussion about themselves. They use the third-person perspective. They do not use contractions, and they emphasize reason and logic. Though an author might appeal to an emotion, the emotional appeal would be subtler and more nuanced. Most of all, however, a formal tone suggests politeness and respect.

Key Takeaways

- When writing, mirror your style after the genre you are writing for.

- You can develop your own voice in your writing by paying special attention to rhythm, diction, and punctuation.

- Use an informal tone for creative writing, personal narratives, and personal essays.

- Use a formal tone for most essays, research papers, reports, and business writing

Mailing Address: 3501 University Blvd. East, Adelphi, MD 20783 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License . © 2022 UMGC. All links to external sites were verified at the time of publication. UMGC is not responsible for the validity or integrity of information located at external sites.

Table of Contents: Online Guide to Writing

Chapter 1: College Writing

How Does College Writing Differ from Workplace Writing?

What Is College Writing?

Why So Much Emphasis on Writing?

Chapter 2: The Writing Process

Doing Exploratory Research

Getting from Notes to Your Draft

Introduction

Prewriting - Techniques to Get Started - Mining Your Intuition

Prewriting: Targeting Your Audience

Prewriting: Techniques to Get Started

Prewriting: Understanding Your Assignment

Rewriting: Being Your Own Critic

Rewriting: Creating a Revision Strategy

Rewriting: Getting Feedback

Rewriting: The Final Draft

Techniques to Get Started - Outlining

Techniques to Get Started - Using Systematic Techniques

Thesis Statement and Controlling Idea

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Freewriting

Writing: Getting from Notes to Your Draft - Summarizing Your Ideas

Writing: Outlining What You Will Write

Chapter 3: Thinking Strategies

A Word About Style, Voice, and Tone: Style Through Vocabulary and Diction

Critical Strategies and Writing

Critical Strategies and Writing: Analysis

Critical Strategies and Writing: Evaluation

Critical Strategies and Writing: Persuasion

Critical Strategies and Writing: Synthesis

Developing a Paper Using Strategies

Kinds of Assignments You Will Write

Patterns for Presenting Information

Patterns for Presenting Information: Critiques

Patterns for Presenting Information: Discussing Raw Data

Patterns for Presenting Information: General-to-Specific Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Problem-Cause-Solution Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Specific-to-General Pattern

Patterns for Presenting Information: Summaries and Abstracts

Supporting with Research and Examples

Writing Essay Examinations

Writing Essay Examinations: Make Your Answer Relevant and Complete

Writing Essay Examinations: Organize Thinking Before Writing

Writing Essay Examinations: Read and Understand the Question

Chapter 4: The Research Process

Planning and Writing a Research Paper

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Ask a Research Question

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Cite Sources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Collect Evidence

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Decide Your Point of View, or Role, for Your Research

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Draw Conclusions

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Find a Topic and Get an Overview

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Manage Your Resources

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Outline

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Survey the Literature

Planning and Writing a Research Paper: Work Your Sources into Your Research Writing

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Human Resources

Research Resources: What Are Research Resources?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found?

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Electronic Resources

Research Resources: Where Are Research Resources Found? - Print Resources

Structuring the Research Paper: Formal Research Structure

Structuring the Research Paper: Informal Research Structure

The Nature of Research

The Research Assignment: How Should Research Sources Be Evaluated?

The Research Assignment: When Is Research Needed?

The Research Assignment: Why Perform Research?

Chapter 5: Academic Integrity

Academic Integrity

Giving Credit to Sources

Giving Credit to Sources: Copyright Laws

Giving Credit to Sources: Documentation

Giving Credit to Sources: Style Guides

Integrating Sources

Practicing Academic Integrity

Practicing Academic Integrity: Keeping Accurate Records

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Paraphrasing Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Quoting Your Source

Practicing Academic Integrity: Managing Source Material - Summarizing Your Sources

Types of Documentation

Types of Documentation: Bibliographies and Source Lists

Types of Documentation: Citing World Wide Web Sources

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - APA Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - CSE/CBE Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - Chicago Style

Types of Documentation: In-Text or Parenthetical Citations - MLA Style

Types of Documentation: Note Citations

Chapter 6: Using Library Resources

Finding Library Resources

Chapter 7: Assessing Your Writing

How Is Writing Graded?

How Is Writing Graded?: A General Assessment Tool

The Draft Stage

The Draft Stage: The First Draft

The Draft Stage: The Revision Process and the Final Draft

The Draft Stage: Using Feedback

The Research Stage

Using Assessment to Improve Your Writing

Chapter 8: Other Frequently Assigned Papers

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Article and Book Reviews

Reviews and Reaction Papers: Reaction Papers

Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Adapting the Argument Structure

Writing Arguments: Purposes of Argument

Writing Arguments: References to Consult for Writing Arguments

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Anticipate Active Opposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Determine Your Organization

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Develop Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Introduce Your Argument

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - State Your Thesis or Proposition

Writing Arguments: Steps to Writing an Argument - Write Your Conclusion

Writing Arguments: Types of Argument

Appendix A: Books to Help Improve Your Writing

Dictionaries

General Style Manuals

Researching on the Internet

Special Style Manuals

Writing Handbooks

Appendix B: Collaborative Writing and Peer Reviewing

Collaborative Writing: Assignments to Accompany the Group Project

Collaborative Writing: Informal Progress Report

Collaborative Writing: Issues to Resolve

Collaborative Writing: Methodology

Collaborative Writing: Peer Evaluation

Collaborative Writing: Tasks of Collaborative Writing Group Members

Collaborative Writing: Writing Plan

General Introduction

Peer Reviewing

Appendix C: Developing an Improvement Plan

Working with Your Instructor’s Comments and Grades

Appendix D: Writing Plan and Project Schedule

Devising a Writing Project Plan and Schedule

Reviewing Your Plan with Others

By using our website you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about how we use cookies by reading our Privacy Policy .

Have a language expert improve your writing

Check your paper for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- College essay

Style and Tone Tips for Your College Essay | Examples

Published on September 21, 2021 by Kirsten Courault . Revised on June 1, 2023.

Unlike an academic essay, the college application essay does not require a formal tone. It gives you a chance to showcase your authentic voice and creative writing abilities. Here are some basic guidelines for using an appropriate style and tone in your college essay.

Table of contents

Strike a balance between casual and formal, write with your authentic voice, maintain a fast pace, use a paraphrasing tool for better style and tone, bend language rules for stylistic reasons, use american english, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about college application essays.

Use a conversational yet respectful tone, as if speaking with a familiar teacher, mentor, or coach. An academic, formal tone will seem too clinical, while an overly casual tone will seem unprofessional to admissions officers.

Find an appropriate middle ground without pedantic language or slang. For example, contractions are acceptable, but text message abbreviations are not.

Note that “Why this college?” essays , scholarship essays , and diversity essays are usually similarly conversational in tone.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Your essay shouldn’t read like a professor, parent, or friend wrote it for you. Use first-person singular “I” statements, appropriate vocabulary for your level, and original expressions.

Prioritize using the first-person singular

Unlike in some other kinds of academic writing, you should write in the first-person singular (e.g., “I,” “me”) in a college application essay to highlight your perspective.

Avoid using “one” for generalizations , since this sounds stilted and unnatural. Use “we” sparingly to avoid projecting your opinions or beliefs onto other people who may not share the same views. In some cases, you can use “we” to talk about a community you know well, such as your family or neighborhood.

The second-person pronoun “you” can be used in some cases. Don’t write the whole essay to an unknown “you,” but if the narrative calls for it, occasionally addressing readers as “you” is generally okay.

Write within your vocabulary range

Creative but careful word choice is essential to enliven your essay. You should embellish basic words, but it shouldn’t read like you used a thesaurus to impress admissions officers.

Use clichés and idioms with discretion

Find a more imaginative way of rewriting overused expressions一unless it’s an intentional stylistic choice.

Write concisely and in the active voice to maintain a quick pace throughout your essay. Only add definitions if they provide necessary explanation.

Write concisely

Opt for a simple, concise way of writing, unless it’s a deliberate stylistic choice to describe a scene. Be intentional with every word, especially since college essays have word limits. However, do vary the length of your sentences to create an interesting flow.

Don’t provide definitions just to sound smart

You should explain terms or concepts that may be unfamiliar to the reader. However, don’t show off with several definitions to impress admissions officers.

Prioritize the active voice to maintain a lively tone

The passive voice can be used when the subject is unimportant or unknown. But in most cases, use the active voice to keep a fast pace throughout your essay.

If it seems hard to find the right tone and voice for your college essay, there are tools that can help.

One of these tools is the paraphrasing tool .

To begin, you can type or copy text you’ve already written into the tool.

After that, select a paraphrasing mode (e.g., fluency for better flowing text) that will rewrite your college essay accordingly.

You can occasionally bend grammatical rules if it adds value to the storytelling process and the essay maintains clarity. This can help your writing stand out from the crowd. However, return to using standard language rules if your stylistic choices would otherwise distract the reader from your overall narrative or could be easily interpreted as unintentional errors.

Sentence fragments

Sentence fragments can convey a quicker pace, a more immediate tone, and intense emotion in your essay. Use them sparingly, as too many fragments can be choppy, confusing, and distracting.

Non-standard capitalization

Usually, common nouns should not be capitalized . But sometimes capitalization can be an effective tool to insert humor or signify importance.

For international students applying to US colleges, it’s important to remember to use US English rather than UK English .

For example, use double quotation marks rather than single ones, and don’t forget to put punctuation inside the double quotation marks. Also be careful to use American spelling, which can differ by just one or two letters from British spelling.

If you want to know more about academic writing , effective communication , or parts of speech , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Academic writing

- Writing process

- Transition words

- Passive voice

- Paraphrasing

Communication

- How to end an email

- Ms, mrs, miss

- How to start an email

- I hope this email finds you well

- Hope you are doing well

Parts of speech

- Personal pronouns

- Conjunctions

College application essays are less formal than other kinds of academic writing . Use a conversational yet respectful tone , as if speaking with a teacher or mentor. Be vulnerable about your feelings, thoughts, and experiences to connect with the reader.

Aim to write in your authentic voice , with a style that sounds natural and genuine. You can be creative with your word choice, but don’t use elaborate vocabulary to impress admissions officers.

Use first-person “I” statements to speak from your perspective . Use appropriate word choices that show off your vocabulary but don’t sound like you used a thesaurus. Avoid using idioms or cliché expressions by rewriting them in a creative, original way.

Write concisely and use the active voice to maintain a quick pace throughout your essay and make sure it’s the right length . Avoid adding definitions unless they provide necessary explanation.

In a college application essay , you can occasionally bend grammatical rules if doing so adds value to the storytelling process and the essay maintains clarity.

However, use standard language rules if your stylistic choices would otherwise distract the reader from your overall narrative or could be easily interpreted as unintentional errors.

A college application essay is less formal than most academic writing . Instead of citing sources formally with in-text citations and a reference list, you can cite them informally in your text.

For example, “In her research paper on genetics, Quinn Roberts explores …”

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Courault, K. (2023, June 01). Style and Tone Tips for Your College Essay | Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 20, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/college-essay/style-and-tone-tips/

Is this article helpful?

Kirsten Courault

Other students also liked, how to revise your college admissions essay | examples, college essay format & structure | example outlines, how to write about yourself in a college essay | examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

20 Academic Tone and Language

Academic language.

Academic language has certain characteristics regardless of the course you are writing for.

- It is formal (see tone ), yet not overly complicated. It is unlike standard conversational language and the hints and tips below will help to elevate your writing style.

- It should be factual and objective; free from personal opinions, bias and value judgments. On rare occasions you may be asked to state your own personal point of view on a particular concept or issue. You should only do so if it is explicitly prescribed. This is the only time first person pronouns (I, my, we, our – see Chapter 5) are permitted.

- Academic writing is always supported by evidence rather than personal opinion, therefore emotional (emotive) or exaggerated (hyperbolic) language are not used.

- Academic language is most often enquiring or analytical in nature, therefore you must be willing to review more than one perspective on a topic and use language that demonstrates the ability to compare and contrast ideas (see signposting below).

- Academic language should be explicit; clear and not vague. Signposting can be used to lead the reader through the text from one section to another or from one idea to the next (see below).

- Passive voice (see chapter 7) can be used to avoid the use of personal pronouns. For example, instead of writing “In this essay I will discuss…”, you can write “This essay will discuss…”

Signposting

Signposting is the use of words and phrases to guide the reader through your written work. There are two types – major and minor.

Major Signposting

Major signposting is used to signal the introduction of key sections or aspects of the work. These might include the aim, purpose, or structure.

In the introduction

- This essay will…

- The aim of this essay is to…

- The major issue being discussed is…

- This essay will define and describe…

- This essay will critically examine…

- This essay will first define…then discuss…before making recommendations for…

- This essay is organised in the following way;

In the conclusion

- To conclude,

- In conclusion,

- To summarise,

- It is evident that

Minor Signposting

Minor signposting are linking words and phrases that make connections for your reader and move them through the text.

- They may be as simple as: First, second, third, next, then, last, lastly, finally

- To offer a counterpoint: However, although, though, yet, alternatively, nevertheless

- To indicate an example: For example, notably, for instance, in this case

These are just a few examples of signposting. For further information and some very useful instances of signposting please follow the link to Queen’s University Belfast [1]

Filetoupload,597684,en.pdf (qub.ac.uk)

Academic Tone

Tone is the general character or attitude of a work and it is highly dependent on word choice and structure. It should match the intended purpose and audience of the text. As noted in the Academic Language section above, the tone should be formal, direct, consistent (polished and error-free), and objective. It should also be factual and not contain personal opinions.

What is the difference between tone and voice?

When learning academic writing skills you may hear “voice” referred to, especially in terms of source integration and maintaining your own “voice” when you write. Note this does not mean maintaining your own opinion. This is something entirely separate. Voice is the unique word choices of the author that reflect the viewpoint they are arguing. Your “voice” is about WHO the reader ‘hears’ when they read your text. Are they ‘hearing’ what you have to say on the topic? Are your claims direct and authoritative ? Or, is your “voice” being drowned out by overuse or overreliance on external sources? This is why it is so important to understand that academic sources should ONLY be used to support what you have to say – your “voice”, NOT opinion – rather than being overused to speak on your behalf. This comes with practise and increased confidence in your own writing and knowing that you have something worth saying. Therefore, do plenty of background reading and research so that you can write from a well-informed position.

Hints and Tips

- First person pronouns (e.g., I, my, me) and second person pronouns (e.g., you, your, yours) (see Chapter 5).

- Contractions: as part of everyday conversational English, contractions have no place in formal academic writing. For example didn’t (did not), can’t (cannot), won’t (will not), it’s (it is – not to be confused with the pronoun its), shouldn’t (should not), and many more. Use the full words.

- Poor connectives: “but”, in particular is a very poor connective. Instead, refer to the signposting examples of however, although, nevertheless, yet, though. Also the overuse of “and”; try alternatives, such as plus, in addition, along with, also, as well as, moreover, together with.

- Avoid colloquial language.

- Avoid hyperbole .

- Avoid emotive language. Even in a persuasive text, appeal to the readers’ minds, not feelings.

- Avoid being verbose .

- Avoid generalizing .

- Avoid statements such as “I think”, “I feel”, or “I believe”; they are clear indicators of personal opinion.

- Do not begin a sentence with “and”, “because”, or digits – e.g., 75% of participants… Always begin a sentence with a word – Seventy-five percent.

- Do not use digits 0-9 as digits; write the whole word – zero, one, two, three. Once you get to double digits you may use the number – 10, 11, 12. The only exception to this rule would be sharing data or statistics, however the previous rule still applies.

- Academic vocabulary (sometimes this is discipline specific, such as technical or medical terms).

- Use tentative or low modal language when something you are writing is not definite or final. For example, could, might, or may, instead of will, definitely, or must.

- Be succinct .

- Include variance of sentence structure (see Chapter 7).

- Use powerful reporting verbs (see Chapter 14).

- Use clever connectives and conjunctions (see Chapter 5).

- Ensure you have excellent spelling, grammar, and punctuation.

- Use accurate referencing, both in-text and the reference list (see Chapter 10).

- Ensure correct use of capital letters for the beginning of each new sentence and for all proper nouns .

- Lastly, use correct subject-verb agreement . For an excellent list of examples of subject-verb agreement, please refer to Purdue Online Writing Lab. [2]

Subject/Verb Agreement // Purdue Writing Lab

- Queen's University Belfast. (n.d.). Signposting. Learning Development Service. https://www.qub.ac.uk/graduate-school/Filestore/Filetoupload,597684,en.pdf#search=signposting ↵

- Purdue University. (2021). Making subjects and verbs argree. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/grammar/subject_verb_agreement.html ↵

able to be trusted as being accurate or true; reliable

researched, reliable, written by academics and published by reputable publishers; often, but not always peer reviewed

informal, ordinary, everyday or familiar conversation, rather than formal speech or writing

obvious and intentional exaggeration; extravagant statement or figure of speech not to be taken literally

characterized by or pertaining to emotions; used to produce an emotional response

characterized by the use of many or too many words; wordy

to infer a general principle from particular facts; e.g., my five year old loves chocolate ice cream, therefore all five year olds love chocolate ice cream

concise expressed in few words

a verb used to report or talk about the ideas of others

used to link words or phrases together See 'Language Basics'

refer to a single entity; names of people, places, and things (e.g., cities, monuments, icons, businesses)

refers to the relationship between the subject and the predicate (part of the sentence containing the verb) of the sentence. Subjects and verbs must always agree in two ways: tense and number.

Academic Writing Skills Copyright © 2021 by Patricia Williamson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Tone in Writing: 42 Examples of Tone For All Types of Writing

by Joe Bunting | 0 comments

What is tone in writing and why does it matter?

Tone is key to all communication. Think of the mother telling her disrespectful child, “Watch your tone, young man.” Or the sarcastic, humorous tone of a comedian performing stand up. Or the awe filled way people speak about their favorite musician, author, or actor. Or the careful, soft tones that people use with each other when they first fall in love.

Tone is communication, sometimes more than the words being used themselves.

So then how do you use tone in writing, and how does tone influence the meaning of a writing piece?

In this article, you'll learn everything you need to know about how to use tone in all types of writing, from creative writing to academic and even business writing. You'll learn what tone actually is in writing and how it's conveyed. You'll learn the forty-two types of tone in writing, plus even have a chance to test your tone recognition with a practice exercise.

Ready to become a tone master? Let's get started.

Why You Should Listen To Me?

I've been a professional writer for more than a decade, writing in various different formats and styles. I've written formal nonfiction books, descriptive novels, humorous memoir chapters, and conversational but informative online articles (like this one!).

Which is all to say, I earn a living in part by matching the right tone to each type of writing I work on. I hope you find the tips on tone below useful!

Table of Contents

Definition of Tone in Writing Why Tone Matters in Writing 42 Types of Tone Plus Tone Examples How to Choose the Right Tone for Your Writing Piece Tone Writing Identification Exercise Tone Vs. Voice in Writing The Role of Tone in Different Types of Writing

Tone in Creative Writing Tone in Academic Writing Tone in Business Writing Tone in Online Writing

Conclusion: How to Master Tone Practice Exercise

Definition of Tone in Writing

Examples of tone can be formal, informal, serious, humorous, sarcastic, optimistic, pessimistic, and many more (see below for all forty-two examples)

Why Does Tone Matter in Writing

I once saw a version of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream in which the dialogue had been completely translated into various Indian dialects, including Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, and more. And yet, despite not knowing any of those languages, I was amazed to find that I could follow the story perfectly, infinitely better than the average Shakespeare in the park play.

How could I understand the story so well despite the fact that it was in another language? In part, it was the skill of the actors and their body language. But one of the biggest ways that the actors communicated meaning was one thing.

Their tone of voice.

Tone is one of the most important ways we grasp the meaning of what someone is saying. If someone says, “I love you,” in an angry, sneering way, it doesn't matter what their words are saying, the meaning will be completely changed by their tone.

In the same way, tone is crucial in writing because it significantly influences how readers interpret and react to the text. Here are a few reasons why tone is important:

- Tone conveys feeling. The tone reflects the writer's attitude toward the subject and the audience, helping to shape readers' perceptions and emotional responses.

- Tone can help readers understand the meaning of the text. A well-chosen tone can clarify meaning, making it easier for readers to understand the writer's intent and message.

- Tone is engaging! As humans, we are designed to respond to emotion and feeling! Tone can help to engage or disengage readers. A relatable or compelling tone can draw readers in, while an off-putting tone can push them away.

- Tone sets the mood. Tone can set the mood or atmosphere of a piece of writing, influencing how readers feel as they go through the text.

- Tone persuades. In persuasive writing, tone plays a significant role in influencing how convincing or compelling your arguments are.

- Tone reflects professionalism. In professional or academic contexts, maintaining an appropriate tone is crucial to uphold the writer's authority.

42 Types of Tone in Writing Plus Examples of Tone

Tone is about feeling—the feeling of a writer toward the topic and audience. Which means that nearly any attitude or feeling can be a type of tone, not just the forty-two listed below.

However, you have to start somewhere, so here a list of common tones that can be used in writing, with an example for each type:

- Example : “Upon analysis of the data, it's evident that the proposed hypothesis is substantiated.”

- Example : “Hey folks, today we'll be chatting about the latest trends in tech.”

- Example : “The implications of climate change on our future generations cannot be overstated.”

- Example : “Why don't scientists trust atoms? Because they make up everything!”

- Example : “Oh great, another diet plan. Just what I needed!”

- Example : “Despite the setbacks, we remain confident in our ability to achieve our goals.”

- Example : “Given the declining economy, it's doubtful if small businesses can survive.”

- Example : “We must act now! Every moment we waste increases the danger.”

- Example : “The experiment concluded with the subject showing a 25% increase in performance.”

- Example : “I've always found the taste of coffee absolutely heavenly.”

- Example : “We owe our success to the ceaseless efforts of our esteemed team.”

- Example : “So much for their ‘revolutionary' product. It's as exciting as watching paint dry.”

- Example : “The film's plot was so predictable it felt like a tiresome déjà vu.”

- Example : “Every setback is a setup for a comeback. Believe in your potential.”

- Example : “A politician making promises? Now there's something new.”

- Example : “We must fight to protect our planet—it's the only home we have.”

- Example : “Whether it rains or shines tomorrow, it makes little difference to me.”

- Example : “As the doors creaked open, a chilling wind swept through the abandoned mansion.”

- Example : “She gazed at the fading photograph, lost in the echoes of a time long past.”

- Example : “The fire station caught on fire—it's almost poetic, isn't it?”

- Example : “I can understand how challenging this period has been for you.”

- Example : “His excuse for being late was as pathetic as it was predictable.”

- Example : “Our feline companion has gone to pursue interests in a different locale” (meaning: the cat ran away).

- Example : “Your report is due by 5 PM tomorrow, no exceptions.”

- Example : “So, you've got a hankering to learn about star constellations—well, you're in the right place!”

- Example : “She tiptoed down the dim hallway, every shadow pulsating with the mysteries of her childhood home.”

- Example : “With the approaching footsteps echoing in his ears, he quickly hid in the dark alcove, heart pounding.”

- Example : “His eyes were a stormy sea, and in their depths, she found an anchor for her love.”

- Example : “In the heart of the mystical forest, nestled between radiant will-o'-the-wisps, was a castle spun from dreams and starlight.”

- Example : “The quantum mechanical model posits that electrons reside in orbitals, probabilistic regions around the nucleus, rather than fixed paths.”

- Example : “When constructing a thesis statement, it's crucial to present a clear, concise argument that your paper will substantiate.”

- Example : “The juxtaposition of light and dark imagery in the novel serves to illustrate the dichotomy between knowledge and ignorance.”

- Example : “Upon deconstructing the narrative, one can discern the recurrent themes of loss and redemption.”

- Example : “One must remember, however, that the epistemological underpinnings of such an argument necessitate a comprehensive understanding of Kantian philosophy.”

- Example : “The ephemeral nature of existence prompts us to contemplate the purpose of our pursuits and the value of our accomplishments.”

- Example : “She left the room.”

- Example : “Global warming is a major issue that needs immediate attention.”

- Example : “Maybe she’ll come tomorrow, I thought, watching the cars pass by, headlights blurring in the rain—oh, to be somewhere else, anywhere, the beach maybe, sand between my toes, the smell of the sea…”

- Example : “In the quiet solitude of the night, I grappled with my fears, my hopes, my dreams—how little I understood myself.”

- Example : “The autumn leaves crunched underfoot, their vibrant hues of scarlet and gold painting a brilliant tapestry against the crisp, cerulean sky.”

- Example : “Looking back on my childhood, I see a time of joy and innocence, a time when the world was a playground of endless possibilities.”

- Example : “Gazing up at the star-studded sky, I was struck by a sense of awe; the universe's vast expanse dwarfed my existence, reducing me to a speck in the cosmic canvas.”

- Example : “His unwavering determination in the face of adversity serves as a shining beacon for us all, inspiring us to strive for our dreams, no matter the obstacles.”

Any others that we forgot? Leave a comment and let us know!

Remember, tone can shift within a piece of writing, and a writer can use more than one tone in a piece depending on their intent and the effect they want to create.

The tones used in storytelling are particularly broad and flexible, as they can shift and evolve according to the plot's developments and the characters' arcs.

How do you choose the right tone for your writing piece?

The tone of a piece of writing is significantly determined by its purpose, genre, and audience. Here's how these three factors play a role:

- Purpose: The main goal of your writing guides your tone. If you're trying to persuade someone, you might adopt a passionate, urgent, or even a formal tone, depending on the subject matter. If you're trying to entertain, a humorous, dramatic, or suspenseful tone could be suitable. For educating or informing, an objective, scholarly, or didactic tone may be appropriate.

- Genre: The type of writing also influences the tone. For instance, academic papers often require a formal, objective, or scholarly tone, while a personal blog post might be more informal and conversational. Similarly, a mystery novel would have a suspenseful tone, a romance novel a romantic or passionate tone, and a satirical essay might adopt an ironic or sarcastic tone.

- Audience: Understanding your audience is crucial in setting the right tone. Professional audiences may expect a formal or respectful tone, while a younger audience might appreciate a more conversational or even irreverent tone. Furthermore, if your audience is familiar with the topic, you can use a more specialized or cerebral tone. In contrast, for a general audience, a clear and straightforward tone might be better.

It's also worth mentioning that the tone can shift within a piece of writing. For example, a novel might mostly maintain a dramatic tone, but could have moments of humor or melancholy. Similarly, an academic paper could be mainly objective but might adopt a more urgent tone in the conclusion to emphasize the importance of the research findings.

In conclusion, to choose the right tone for your writing, consider the intent of your piece, the expectations of the genre, and the needs and preferences of your audience. And don't forget, maintaining a consistent tone is key to ensuring your message is received as intended.

How to Identify Tone in Writing

How do you identify the tone in various texts (or even in your own writing)? What are the key indicators that help you figure out what tone a writing piece is?

Identifying the tone in a piece of writing can be done by focusing on a few key elements:

- Word Choice (Diction): The language an author uses can give you strong clues about the tone. For instance, formal language with lots of technical terms suggests a formal or scholarly tone, while casual language with slang or contractions suggests an informal or conversational tone.

- Sentence Structure (Syntax): Longer, complex sentences often indicate a formal, scholarly, or descriptive tone. Shorter, simpler sentences can suggest a more direct, informal, or urgent tone.

- Punctuation: The use of punctuation can also impact tone. Exclamation marks may suggest excitement, urgency, or even anger. Question marks might indicate confusion, curiosity, or sarcasm. Ellipsis (…) can suggest suspense, uncertainty, or thoughtfulness.

- Figurative Language: The use of metaphors, similes, personification, and other literary devices can help set the tone. For instance, an abundance of colorful metaphors and similes could suggest a dramatic, romantic, or fantastical tone.

- Mood: The emotional atmosphere of the text can give clues to the tone. If the text creates a serious, somber mood, the tone is likely serious or melancholic. If the mood is light-hearted or amusing, the tone could be humorous or whimsical.

- Perspective or Point of View: First-person narratives often adopt a subjective, personal, or reflective tone. Third-person narratives can have a range of tones, but they might lean towards being more objective, descriptive, or dramatic.

- Content: The subject matter itself can often indicate the tone. A text about a tragic event is likely to have a serious, melancholic, or respectful tone. A text about a funny incident will probably have a humorous or light-hearted tone.

By carefully analyzing these elements, you can determine the tone of a text. In your own writing, you can use these indicators to check if you're maintaining the desired tone consistently throughout your work.

Tone Writing Exercise: Identify the tone in each of the following sentences

Let’s do a little writing exercise by identifying the tones of the following example sentences.

- “The participants in the study displayed a significant improvement in their cognitive abilities post intervention.”

- “Hey guys, just popping in to share some cool updates from our team!”

- “The consequences of climate change are dire and demand immediate attention from world leaders.”

- “I told my wife she should embrace her mistakes. She gave me a hug.”

- “Despite the challenges we've faced this year, I'm confident that brighter days are just around the corner.”

- “Given the state of the economy, it seems unlikely that we'll see any significant improvements in the near future.”

- “No mountain is too high to climb if you believe in your ability to reach the summit.”

- “As she stepped onto the cobblestone streets of the ancient city, the echoes of its rich history whispered in her ears.”

- “Oh, you're late again? What a surprise.”

- “The methodology of this research hinges upon a quantitative approach, using statistical analysis to derive meaningful insights from the collected data.”

Give them a try. I’ll share the answers at the end!

Tone Versus Voice in Writing

Tone and voice in writing are related but distinct concepts:

Voice is the unique writing style or personality of the writing that makes it distinct to a particular author. It's a combination of the author's syntax, word choice, rhythm, and other stylistic elements.

Voice tends to remain consistent across different works by the same author, much like how people have consistent speaking voices.

For example, the voice in Ernest Hemingway's work is often described as minimalist and straightforward, while the voice in Virginia Woolf's work is more stream-of-consciousness and introspective.

Tone , on the other hand, refers to the attitude or emotional qualities of the writing. It can change based on the subject matter, the intended audience, and the purpose of the writing.

In the same way that someone's tone of voice can change based on what they're talking about or who they're talking to, the tone of a piece of writing can vary. Using the earlier examples, a work by Hemingway might have a serious, intense tone, while a work by Woolf might have a reflective, introspective tone.

So, while an author's voice remains relatively consistent, the tone they use can change based on the context of the writing.

Tone and voice are two elements of writing that are closely related and often work hand in hand to create a writer's unique style. Here's how they can be used together:

- Consistency: A consistent voice gives your writing a distinctive personality, while a consistent tone helps to set the mood or attitude of your piece. Together, they create a uniform feel to your work that can make your writing instantly recognizable to your readers.

- Audience Engagement: Your voice can engage readers on a fundamental level by giving them a sense of who you are or the perspective from which you're writing. Your tone can then enhance this engagement by setting the mood, whether it's serious, humorous, formal, informal, etc., depending on your audience and the purpose of your writing.

- Clarity of Message: Your voice can express your unique perspective and values, while your tone can help convey your message clearly by fitting the context. For example, a serious tone in an academic research paper or a casual, friendly tone in a personal blog post helps your audience understand your purpose and message.

- Emotional Impact: Voice and tone together can create emotional resonance. A distinctive voice can make readers feel connected to you as a writer, while the tone can evoke specific emotions that align with your content. For example, a melancholic tone in a heartfelt narrative can elicit empathy from the reader, enhancing the emotional impact of your story.

- Versatility: While maintaining a consistent overall voice, you can adjust your tone according to the specific piece you're writing. This can show your versatility as a writer. For example, you may have a generally conversational voice but use a serious tone for an important topic and a humorous tone for a lighter topic.

Remember, your unique combination of voice and tone is part of what sets you apart as a writer. It's worth taking the time to explore and develop both.

The Role of Tone in Different Types of Writing

Just as different audiences require different tones of voice, so does your tone change depending on the audience of your writing.

Tone in Creative Writing

Tone plays a crucial role in creative writing, shaping the reader's experience and influencing their emotional response to the work. Here are some considerations for how to use tone in creative writing:

- Create Atmosphere: Tone is a powerful tool for creating a specific atmosphere or mood in a story. For example, a suspenseful tone can create a sense of tension and anticipation, while a humorous tone can make a story feel light-hearted and entertaining.

- Character Development: The tone of a character's dialogue and thoughts can reveal a lot about their personality and emotional state. A character might speak in a sarcastic tone, revealing a cynical worldview, or their internal narrative might be melancholic, indicating feelings of sadness or regret.

- Plot Development: The tone can shift with the plot, reflecting changes in the story's circumstances. An initially optimistic tone might become increasingly desperate as a situation worsens, or a serious tone could give way to relief and joy when a conflict is resolved.

- Theme Expression: The overall tone of a story can reinforce its themes. For instance, a dark and somber tone could underscore themes of loss and grief, while a hopeful and inspirational tone could enhance themes of resilience and personal growth.

- Reader Engagement: A well-chosen tone can engage the reader's emotions, making them more invested in the story. A dramatic, high-stakes tone can keep readers on the edge of their seats, while a romantic, sentimental tone can make them swoon.

- Style and Voice: The tone is part of the writer's unique voice and style. The way you blend humor and seriousness, or the balance you strike between formal and informal language, can give your work a distinctive feel.

In creative writing, it's important to ensure that your tone is consistent, unless a change in tone is intentional and serves a specific purpose in your story. An inconsistent or shifting tone can be jarring and confusing for the reader. To check your tone, try reading your work aloud, as this can make shifts in tone more evident.

Tone in Academic Writing

In academic writing, the choice of tone is crucial as it helps to establish credibility and convey information in a clear, unambiguous manner. Here are some aspects to consider about tone in academic writing:

- Formal: Academic writing typically uses a formal tone, which means avoiding colloquialisms, slang, and casual language. This helps to maintain a level of professionalism and seriousness that is appropriate for scholarly work. For instance, instead of saying “experts think this is really bad,” a more formal phrasing would be, “scholars have identified significant concerns regarding this matter.”

- Objective: The tone in academic writing should usually be objective, rather than subjective. This means focusing on facts, evidence, and logical arguments rather than personal opinions or emotions. For example, instead of saying “I believe that climate change is a major issue,” an objective statement would be, “Research indicates that climate change poses substantial environmental risks.”

- Precise: Precision is crucial in academic writing, so the tone should be specific and direct. Avoid vague or ambiguous language that might confuse the reader or obscure the meaning of your argument. For example, instead of saying “several studies,” specify the exact number of studies or name the authors if relevant.

- Respectful: Even when critiquing other scholars' work, it's essential to maintain a respectful tone. This means avoiding harsh or judgmental language and focusing on the intellectual content of the argument rather than personal attacks.

- Unbiased: Strive for an unbiased tone by presenting multiple perspectives on the issue at hand, especially when it's a subject of debate in the field. This shows that you have a comprehensive understanding of the topic and that your conclusions are based on a balanced assessment of the evidence.

- Scholarly: A scholarly tone uses discipline-specific terminology and acknowledges existing research on the topic. However, it's also important to explain any complex or specialized terms for the benefit of readers who may not be familiar with them.

By choosing an appropriate tone, you can ensure that your academic writing is professional, credible, and accessible to your intended audience. Remember, the tone can subtly influence how your readers perceive your work and whether they find your arguments convincing.

Tone in Business Writing

In business writing, your tone should be professional, clear, and respectful. Here are some aspects to consider:

- Professional and Formal: Just like in academic writing, business writing typically uses a professional and formal tone. This ensures that the communication is taken seriously and maintains an air of professionalism. However, remember that “formal” doesn't necessarily mean “stiff” or “impersonal”—a little warmth can make your writing more engaging.

- Clear and Direct: Your tone should also be clear and direct. Ambiguity can lead to misunderstanding, which can have negative consequences in a business setting. Make sure your main points are obvious and not hidden in jargon or overly complex sentences.

- Respectful: Respect is crucial in business communication. Even when addressing difficult topics or delivering bad news, keep your tone courteous and considerate. This fosters a positive business relationship and shows that you value the other party.

- Concise: In the business world, time is often at a premium. Therefore, a concise tone—saying what you need to say as briefly as possible—is often appreciated. This is where the minimalist tone can shine.

- Persuasive: In many situations, such as a sales pitch or a negotiation, a persuasive tone is beneficial. This involves making your points convincingly, showing enthusiasm where appropriate, and using language that motivates the reader to act.

- Neutral: In situations where you're sharing information without trying to persuade or express an opinion, a neutral tone is best. For example, when writing a business report or summarizing meeting minutes, stick to the facts without letting personal bias influence your language.

By adapting your tone based on these guidelines and the specific context, you can ensure your business writing is effective and appropriate.

Tone in Online Writing

Online writing can vary greatly depending on the platform and purpose of the content. However, some common considerations for tone include:

- Conversational and Informal: Online readers often prefer a more conversational, informal tone that mimics everyday speech. This can make your writing feel more personal and relatable. Blogs, social media posts, and personal websites often employ this tone.

- Engaging and Enthusiastic: With so much content available online, an engaging and enthusiastic tone can help grab readers' attention and keep them interested. You can express your passion for a topic, ask questions, or use humor to make your writing more lively and engaging.

- Clear and Direct: Just like in business and academic writing, clarity is key in online writing. Whether you're writing a how-to article, a product description, or a blog post, make your points clearly and directly to help your readers understand your message.

- Descriptive and Vivid: Because online writing often involves storytelling or explaining complex ideas, a descriptive tone can be very effective. Use vivid language and sensory details to help readers visualize what you're talking about.

- Authoritative: If you're writing content that's meant to inform or educate, an authoritative tone can help establish your credibility. This involves demonstrating your knowledge and expertise on the topic, citing reliable sources, and presenting your information in a confident, professional manner.

- Optimistic and Inspirational: Particularly for motivational blogs, self-help articles, or other content meant to inspire, an optimistic tone can be very effective. This involves looking at the positive side of things, encouraging readers, and offering hope.

Remember, the best tone for online writing depends heavily on your audience, purpose, and platform. Always keep your readers in mind, and adapt your tone to suit their needs and expectations.

How to Master Tone

Tone isn't as hard as you think.

If you've ever said something with feeling in your voice or with a certain attitude, you know how it works.

And while mastering the word choice, syntax, and other techniques to use tone effectively can be tricky, just by choosing a tone, being aware of tone in your writing, and making a concerted effort to practice it will add depth and style to your writing, heightening both the meaning and your audiences enjoyment.

Remember, we all have tone. You just need to practice using it. Happy writing!

What tone do you find yourself using the most in your writing ? Let us know in the comments .

Here are two writing exercises for you to practice tone.

Exercise 1: Identify the Tone

Using the ten identification examples above, write out the tones for each of the examples. Then use this answer guide to check your work.

- Pessimistic

- Inspirational

How many did you get correctly? Let me know in the comments .

Exercise 2: Choose One Tone and Write

Choose one of the tones above, set a timer for fifteen minutes, then free write in that tone.

When your time's up, post your practice in the Pro Practice Workshop here (and if you’re not a member yet, you can join here ), and share feedback with a few other writers.

Joe Bunting

Joe Bunting is an author and the leader of The Write Practice community. He is also the author of the new book Crowdsourcing Paris , a real life adventure story set in France. It was a #1 New Release on Amazon. Follow him on Instagram (@jhbunting).

Want best-seller coaching? Book Joe here.

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

Styles & Tones Used in Research Essays

Differences of Literature & Writing Courses

Writing research essays requires a specific style and tone according to who the audience is and what the subject matter is. Knowing how to accurately use a specific style guide will lend organization and credibility to your essay, whether you are writing it for publication or a college class. Essay styles differ according to subject matter and teacher preference and cannot be used interchangeably.

Formal Tone vs. Casual Tone

The audience and intentions of a research paper decide the tone. If your essay is going to be printed in a scholarly or didactic publication or reviewed by a college professor, a formal and succinct tone is best. Writing for a more leisurely and laid back audience calls for a more casual and conversational tone.

Scientific Research Essays

Scientific research essays are written with brevity, authority, and precision because they usually include statistics, numbers and data. Most scientific papers are written in the American Chemical Society style, which provides guidelines for using numbers, tables, graphs and figures.

Modern Language Association Style

The Modern Language Association style is the most common style used for research essays in college. The MLA style formats how to cite sources of information both in the body of your essay, footnotes, endnotes and at the end in a bibliography.

American Psychological Association Style

The American Psychological Association style is another style commonly used in college research essays, but is seen more in upper-level and graduate level classes and in social science essays. As with the MLA style, it guides writers on how to cite sources of information, but has a different format than the MLA style.

Chicago Manual of Style

The Chicago Manual of Style is primarily used by editors, but can also be used in research essays for documenting sources and for grammatical usage. The CMS style is used for essays in literature, history, the arts and the social sciences.

Related Articles

Why Use APA Formatting in College Writing?

How to cite the 4th amendment.

How to Head a College Paper

How to Introduce a Research Paper Sample

How to Write a 20-Page Term Paper

Difference Between College-Level and Casual Writing?

How to Write APA Papers in Narrative Style

How to Analyze Expository Writing

- Purdue Online Writing Lab: MLA Formatting and Style Guide

- Purdue Online Writing Lab: General Format

- Purdue Online Writing Lab: Chicago Manual of Style...

Comprehensive Guide: Understanding Tone & Examples

What is tone, types of tone, how to identify tone, why tone matters, examples of tone, common mistakes when interpreting tone, tips for using tone effectively, using tone in different genres.

Imagine you're reading a story. Suddenly, you sense a chill creeping up your spine, or maybe you're grinning ear to ear. What's causing these reactions? Is it the words on the page, or is it something a bit more subtle? The answer lies in 'tone', an often overlooked but significant aspect of writing. Ever wondered what exactly tone is or how it influences your reading experience? Let's break it down and explore the intriguing world of tone in literature.

Before we dive in, let's simplify the definition of tone. In the simplest terms, tone is the attitude or emotion a writer conveys in their work. It's like the secret ingredient that spices up the reading experience, making you feel a certain way — happy, sad, scared, or even excited.

Now that we've got the basic definition of tone, let's look at some key points:

- Tone influences how you interpret a text: It's the writer's tone that guides you in understanding the text's mood. For example, a serious tone might tell you that the situation in the story is intense.

- Tone can vary: Just like your emotions change, the tone in writing can fluctuate too. One moment you might be reading a cheerful dialogue, and the next, the tone could shift to something more somber.

- Tone isn't what you say, but how you say it: Here's an interesting thing about tone — it's not about the words themselves, but how they're put together. The choice of words, sentence structure, and even punctuation can all affect the tone.

In a nutshell, the definition of tone in literature isn't just about what is being said, but how it's being said. It's that extra layer that adds depth and perspective to the written word, enhancing your overall reading experience.

Now that we've got a basic understanding of what tone means, let's explore the different types of tone that can appear in writing.

- Formal Tone: You'll typically find this in academic writing, business correspondence, or professional settings. It's like wearing a suit and tie — it's all about precision, clarity, and respect.

- Informal Tone: This is like the casual Friday of tones. It's more relaxed and personal, often used in conversational writing or personal communication.

- Optimistic Tone: Here, the writer sees the glass as half full. Expect to find cheerful, hopeful and positive vibes in this tone.

- Pessimistic Tone: In contrast to the optimistic tone, this one sees the glass as half empty. It's often more negative, focusing on the downsides or potential failures.

- Humorous Tone: Who doesn't love a good laugh? This tone is all about making you smile, chuckle, or even burst out laughing.

- Serious Tone: The serious tone is all business, no jokes. This tone sets a sober and straightforward mood.

Remember, these are just a few examples. The tone of a piece can be as varied and complex as human emotions themselves. The key is to recognize how these tones can influence a reader's perception and understanding of the text.

Okay. We've covered what tone is and peeked at a few common types. But how do you identify the tone in a piece of writing? Well, it's not as hard as you might think. Here are a few pointers to help you on your way.

- Pay Attention to Word Choice: Think of this as the wardrobe of the writing. The words an author chooses to use can tell you a lot about the tone they're trying to set. Big, fancy words? Probably a formal tone. Simple, everyday language? Likely more informal.

- Check Out the Sentence Structure: Is the author using long, complex sentences? Or are they keeping it short and sweet? The structure of the sentences can give you clues about the tone.

- Look for Punctuation Clues: Punctuation isn't just about being grammatically correct. It can also help set the tone. Lots of exclamation points suggest excitement or urgency. Question marks could mean the author is posing rhetorical questions to get you thinking.

- Consider the Content: If an author is writing about a serious topic, they're probably not going to use a humorous tone. The content of the writing itself can be a big hint about the tone.

Identifying the tone isn't an exact science, and it can sometimes take a bit of detective work. But with practice, you'll become a pro at sniffing out the tone in no time!

So, you've got the definition of tone down, and you're getting the hang of identifying it in different pieces of writing. But why does it matter? Why should you care about tone? Well, let's break it down.

First, tone helps communicate a message more effectively. It's like adding color to a black and white photo—it brings depth and nuance. Imagine reading a suspense novel written in a casual, laid-back tone. Not quite the same thrill, right?

Second, tone helps to build a connection between the writer and the reader. It's a way for the writer to say, "Hey, I'm talking to you. I understand you. I'm on your level." It's like choosing to speak the same language as your reader.

Finally, tone can express the writer's attitude or feelings towards the subject matter. It's a way for writers to show their personality and to make their writing uniquely theirs.

In essence, tone is a powerful tool in a writer's toolbox, and understanding it can help you not only in writing but also in reading and understanding the work of others. So, keep practicing and before you know it, you'll be a tone detective!

Now that we've explored the definition of tone and grasped why it matters, let's dive into some concrete examples. Seeing tone in action can really help clarify things.

Serious Tone: A serious tone is often used in academic or professional writing. For instance, a scientific research paper on climate change would likely adopt a serious tone. It wouldn't include jokes or casual language—it needs to be straight to the point and factual. The serious tone says, "This is important, and we need to pay attention."

Humorous Tone: This is where the writer uses wit, humor, or satire to engage the reader. A great example of a humorous tone is found in the "Diary of a Wimpy Kid" series. The lighthearted and funny tone makes the books entertaining and engaging for kids and adults alike.

Informal Tone: An informal tone is like a friendly chat. Think of a blog post about someone's travel adventures. The tone is relaxed and personal, making you feel like you're sitting down for a coffee with the writer.