Major theories and models of learning

Several ideas and priorities, then, affect how we teachers think about learning, including the curriculum, the difference between teaching and learning, sequencing, readiness, and transfer. The ideas form a “screen” through which to understand and evaluate whatever psychology has to offer education. As it turns out, many theories, concepts, and ideas from educational psychology do make it through the “screen” of education, meaning that they are consistent with the professional priorities of teachers and helpful in solving important problems of classroom teaching. In the case of issues about classroom learning, for example, educational psychologists have developed a number of theories and concepts that are relevant to classrooms, in that they describe at least some of what usually happens there and offer guidance for assisting learning. It is helpful to group the theories according to whether they focus on changes in behavior or in thinking. The distinction is rough and inexact, but a good place to begin. For starters, therefore, consider two perspectives about learning, called behaviorism (learning as changes in overt behavior) and constructivism, (learning as changes in thinking). The second category can be further divided into psychological constructivism (changes in thinking resulting from individual experiences), and social constructivism, (changes in thinking due to assistance from others). The rest of this chapter describes key ideas from each of these viewpoints. As I hope you will see, each describes some aspects of learning not just in general, but as it happens in classrooms in particular. So each perspective suggests things that you might do in your classroom to make students’ learning more productive.

Behaviorism: changes in what students do

Behaviorism is a perspective on learning that focuses on changes in individuals’ observable behaviors— changes in what people say or do. At some point we all use this perspective, whether we call it “behaviorism” or something else. The first time that I drove a car, for example, I was concerned primarily with whether I could actually do the driving, not with whether I could describe or explain how to drive. For another example: when I reached the point in life where I began cooking meals for myself, I was more focused on whether I could actually produce edible food in a kitchen than with whether I could explain my recipes and cooking procedures to others. And still another example—one often relevant to new teachers: when I began my first year of teaching, I was more focused on doing the job of teaching—on day-to-day survival—than on pausing to reflect on what I was doing.

Note that in all of these examples, focusing attention on behavior instead of on “thoughts” may have been desirable at that moment, but not necessarily desirable indefinitely or all of the time. Even as a beginner, there are times when it is more important to be able to describe how to drive or to cook than to actually do these things. And there definitely are many times when reflecting on and thinking about teaching can improve teaching itself. (As a teacher-friend once said to me: “Don’t just do something; stand there!”) But neither is focusing on behavior which is not necessarily less desirable than focusing on students’ “inner” changes, such as gains in their knowledge or their personal attitudes. If you are teaching, you will need to attend to all forms of learning in students, whether inner or outward.

In classrooms, behaviorism is most useful for identifying relationships between specific actions by a student and the immediate precursors and consequences of the actions. It is less useful for understanding changes in students’ thinking; for this purpose we need theories that are more cognitive (or thinking-oriented) or social, like the ones described later in this chapter. This fact is not a criticism of behaviorism as a perspective, but just a clarification of its particular strength or usefulness, which is to highlight observable relationships among actions, precursors and consequences. Behaviorists use particular terms (or “lingo,” some might say) for these relationships. One variety of behaviorism that has proved especially useful to educators is operant conditioning, described in the next section.

Operant conditioning: new behaviors because of new consequences

Operant conditioning focuses on how the consequences of a behavior affect the behavior over time. It begins with the idea that certain consequences tend to make certain behaviors happen more frequently. If I compliment a student for a good comment made during discussion, there is more of a chance that I will hear further comments from the student in the future (and hopefully they too will be good ones!). If a student tells a joke to classmates and they laugh at it, then the student is likely to tell more jokes in the future and so on.

The original research about this model of learning was not done with people, but with animals. One of the pioneers in the field was a Harvard professor named B. F. Skinner, who published numerous books and articles about the details of the process and who pointed out many parallels between operant conditioning in animals and operant conditioning in humans (1938, 1948, 1988). Skinner observed the behavior of rather tame laboratory rats (not the unpleasant kind that sometimes live in garbage dumps). He or his assistants would put them in a cage that contained little except a lever and a small tray just big enough to hold a small amount of food. (Figure 1 shows the basic set-up, which is sometimes nicknamed a “Skinner box.”) At first the rat would sniff and “putter around” the cage at random, but sooner or later it would happen upon the lever and eventually happen to press it. Presto! The lever released a small pellet of food, which the rat would promptly eat. Gradually the rat would spend more time near the lever and press the lever more frequently, getting food more frequently. Eventually it would spend most of its time at the lever and eating its fill of food. The rat had “discovered” that the consequence of pressing the level was to receive food. Skinner called the changes in the rat’s behavior an example of operant conditioning , and gave special names to the different parts of the process. He called the food pellets the reinforcement and the lever-pressing the operant (because it “operated” on the rat’s environment). See below.

Figure 1: Operant conditioning with a laboratory rat

Skinner and other behavioral psychologists experimented with using various reinforcers and operants. They also experimented with various patterns of reinforcement (or schedules of reinforcement ), as well as with various cues or signals to the animal about when reinforcement was available. It turned out that all of these factors—the operant, the reinforcement, the schedule, and the cues—affected how easily and thoroughly operant conditioning occurred. For example, reinforcement was more effective if it came immediately after the crucial operant behavior, rather than being delayed, and reinforcements that happened intermittently (only part of the time) caused learning to take longer, but also caused it to last longer.

Operant conditioning and students’ learning: Since the original research about operant conditioning used animals, it is important to ask whether operant conditioning also describes learning in human beings, and especially in students in classrooms. On this point the answer seems to be clearly “yes.” There are countless classroom examples of consequences affecting students’ behavior in ways that resemble operant conditioning, although the process certainly does not account for all forms of student learning (Alberto & Troutman, 2005). Consider the following examples. In most of them the operant behavior tends to become more frequent on repeated occasions:

- A seventh-grade boy makes a silly face (the operant) at the girl sitting next to him. Classmates sitting around them giggle in response (the reinforcement).

- A kindergarten child raises her hand in response to the teacher’s question about a story (the operant). The teacher calls on her and she makes her comment (the reinforcement).

- Another kindergarten child blurts out her comment without being called on (the operant). The teacher frowns, ignores this behavior, but before the teacher calls on a different student, classmates are listening attentively (the reinforcement) to the student even though he did not raise his hand as he should have.

- A twelfth-grade student—a member of the track team—runs one mile during practice (the operant). He notes the time it takes him as well as his increase in speed since joining the team (the reinforcement).

- A child who is usually very restless sits for five minutes doing an assignment (the operant). The teaching assistant compliments him for working hard (the reinforcement).

- A sixth-grader takes home a book from the classroom library to read overnight (the operant). When she returns the book the next morning, her teacher puts a gold star by her name on a chart posted in the room (the reinforcement).

These examples are enough to make several points about operant conditioning. First, the process is widespread in classrooms—probably more widespread than teachers realize. This fact makes sense, given the nature of public education: to a large extent, teaching is about making certain consequences (like praise or marks) depend on students’ engaging in certain activities (like reading certain material or doing assignments). Second, learning by operant conditioning is not confined to any particular grade, subject area, or style of teaching, but by nature happens in every imaginable classroom. Third, teachers are not the only persons controlling reinforcements. Sometimes they are controlled by the activity itself (as in the track team example), or by classmates (as in the “giggling” example). This leads to the fourth point: that multiple examples of operant conditioning often happen at the same time. A case study in Appendix A of this book ( The decline and fall of Jane Gladstone ) suggests how this happened to someone completing student teaching.

Because operant conditioning happens so widely, its effects on motivation are a bit complex. Operant conditioning can encourage intrinsic motivation , to the extent that the reinforcement for an activity is the activity itself. When a student reads a book for the sheer enjoyment of reading, for example, he is reinforced by the reading itself, and we we can say that his reading is “intrinsically motivated.” More often, however, operant conditioning stimulates both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation at the same time. The combining of both is noticeable in the examples in the previous paragraph. In each example, it is reasonable to assume that the student felt intrinsically motivated to some partial extent, even when reward came from outside the student as well. This was because part of what reinforced their behavior was the behavior itself—whether it was making faces, running a mile, or contributing to a discussion. At the same time, though, note that each student probably was also extrinsically motivated , meaning that another part of the reinforcement came from consequences or experiences not inherently part of the activity or behavior itself. The boy who made a face was reinforced not only by the pleasure of making a face, for example, but also by the giggles of classmates. The track student was reinforced not only by the pleasure of running itself, but also by knowledge of his improved times and speeds. Even the usually restless child sitting still for five minutes may have been reinforced partly by this brief experience of unusually focused activity, even if he was also reinforced by the teacher aide’s compliment. Note that the extrinsic part of the reinforcement may sometimes be more easily observed or noticed than the intrinsic part, which by definition may sometimes only be experienced within the individual and not also displayed outwardly. This latter fact may contribute to an impression that sometimes occurs, that operant conditioning is really just “bribery in disguise,” that only the external reinforcements operate on students’ behavior. It is true that external reinforcement may sometimes alter the nature or strength of internal (or intrinsic) reinforcement, but this is not the same as saying that it destroys or replaces intrinsic reinforcement. But more about this issue later!

Key concepts about operant conditioning: Operant conditioning is made more complicated, but also more realistic, by several additional ideas. They can be confusing because the ideas have names that sound rather ordinary, but that have special meanings with the framework of operant theory. Among the most important concepts to understand are the following:

- generalization

- discrimination

- schedules of reinforcement

The paragraphs below explain each of these briefly, as well as their relevance to classroom teaching and learning.

Extinction refers to the disappearance of an operant behavior because of lack of reinforcement. A student who stops receiving gold stars or compliments for prolific reading of library books, for example, may extinguish (i.e. decrease or stop) book-reading behavior. A student who used to be reinforced for acting like a clown in class may stop clowning once classmates stop paying attention to the antics.

Generalization refers to the incidental conditioning of behaviors similar to an original operant . If a student gets gold stars for reading library books, then we may find her reading more of other material as well—newspapers, comics, etc.–even if the activity is not reinforced directly. The “spread” of the new behavior to similar behaviors is called generalization. Generalization is a lot like the concept of transfer discussed early in this chapter, in that it is about extending prior learning to new situations or contexts. From the perspective of operant conditioning, though, what is being extended (or “transferred” or generalized) is a behavior, not knowledge or skill.

Discrimination means learning not to generalize. In operant conditioning, what is not overgeneralized (i.e. what is discriminated) is the operant behavior. If I am a student who is being complimented (reinforced) for contributing to discussions, I must also learn to discriminate when to make verbal contributions from when not to make them—such as when classmates or the teacher are busy with other tasks. Discrimination learning usually results from the combined effects of reinforcement of the target behavior and extinction of similar generalized behaviors. In a classroom, for example, a teacher might praise a student for speaking during discussion, but ignore him for making very similar remarks out of turn. In operant conditioning, the schedule of reinforcement refers to the pattern or frequency by which reinforcement is linked with the operant. If a teacher praises me for my work, does she do it every time, or only sometimes? Frequently or only once in awhile? In respondent conditioning, however, the schedule in question is the pattern by which the conditioned stimulus is paired with the unconditioned stimulus. If I am student with Mr Horrible as my teacher, does he scowl every time he is in the classroom, or only sometimes? Frequently or rarely?

Behavioral psychologists have studied schedules of reinforcement extensively (for example, Ferster, et al., 1997; Mazur, 2005), and found a number of interesting effects of different schedules. For teachers, however, the most important finding may be this: partial or intermittent schedules of reinforcement generally cause learning to take longer, but also cause extinction of learning to take longer. This dual principle is important for teachers because so much of the reinforcement we give is partial or intermittent. Typically, if I am teaching, I can compliment a student a lot of the time, for example, but there will inevitably be occasions when I cannot do so because I am busy elsewhere in the classroom. For teachers concerned both about motivating students and about minimizing inappropriate behaviors, this is both good news and bad. The good news is that the benefits of my praising students’ constructive behavior will be more lasting, because they will not extinguish their constructive behaviors immediately if I fail to support them every single time they happen. The bad news is that students’ negative behaviors may take longer to extinguish as well, because those too may have developed through partial reinforcement. A student who clowns around inappropriately in class, for example, may not be “supported” by classmates’ laughter every time it happens, but only some of the time. Once the inappropriate behavior is learned, though, it will take somewhat longer to disappear even if everyone—both teacher and classmates—make a concerted effort to ignore (or extinguish) it.

Finally, behavioral psychologists have studied the effects of cues . In operant conditioning, a cue is a stimulus that happens just prior to the operant behavior and that signals that performing the behavior may lead to reinforcement. In the original conditioning experiments, Skinner’s rats were sometimes cued by the presence or absence of a small electric light in their cage. Reinforcement was associated with pressing a lever when, and only when, the light was on. In classrooms, cues are sometimes provided by the teacher deliberately, and sometimes simply by the established routines of the class. Calling on a student to speak, for example, can be a cue that if the student does say something at that moment, then he or she may be reinforced with praise or acknowledgment. But if that cue does not occur—if the student is not called on—speaking may not be rewarded. In more everyday, non-behaviorist terms, the cue allows the student to learn when it is acceptable to speak, and when it is not.

Constructivism: changes in how students think

Behaviorist models of learning may be helpful in understanding and influencing what students do, but teachers usually also want to know what students are thinking , and how to enrich what students are thinking. For this goal of teaching, some of the best help comes from constructivism , which is a perspective on learning focused on how students actively create (or “construct”) knowledge out of experiences. Constructivist models of learning differ about how much a learner constructs knowledge independently, compared to how much he or she takes cues from people who may be more of an expert and who help the learner’s efforts (Fosnot, 2005; Rockmore, 2005). For convenience these are called psychological constructivism and social constructivism (or sometimes sociocultural theory ). As explained in the next section, both focus on individuals’ thinking rather than their behavior, but they have distinctly different implications for teaching.

Psychological constructivism: the independent investigator

The main idea of psychological constructivism is that a person learns by mentally organizing and reorganizing new information or experiences. The organization happens partly by relating new experiences to prior knowledge that is already meaningful and well understood. Stated in this general form, individual constructivism is sometimes associated with a well-known educational philosopher of the early twentieth century, John Dewey (1938–1998). Although Dewey himself did not use the term constructivism in most of his writing, his point of view amounted to a type of constructivism, and he discussed in detail its implications for educators. He argued, for example, that if students indeed learn primarily by building their own knowledge, then teachers should adjust the curriculum to fit students’ prior knowledge and interests as fully as possible. He also argued that a curriculum could only be justified if it related as fully as possible to the activities and responsibilities that students will probably have later , after leaving school. To many educators these days, his ideas may seem merely like good common sense, but they were indeed innovative and progressive at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Another recent example of psychological constructivism is the cognitive theory of Jean Piaget (Piaget, 2001; Gruber & Voneche, 1995). Piaget described learning as interplay between two mental activities that he called assimilation and accommodation . Assimilation is the interpretation of new information in terms of pre-existing concepts, information or ideas. A preschool child who already understands the concept of bird , for example, might initially label any flying object with this term—even butterflies or mosquitoes. Assimilation is therefore a bit like the idea of generalization in operant conditioning, or the idea of transfer described at the beginning of this chapter. In Piaget’s viewpoint, though, what is being transferred to a new setting is not simply a behavior (Skinner’s “operant” in operant conditioning), but a mental representation for an object or experience.

Assimilation operates jointly with accommodation , which is the revision or modification of pre-existing concepts in terms of new information or experience. The preschooler who initially generalizes the concept of bird to include any flying object, for example, eventually revises the concept to include only particular kinds of flying objects, such as robins and sparrows, and not others, like mosquitoes or airplanes. For Piaget, assimilation and accommodation work together to enrich a child’s thinking and to create what Piaget called cognitive equilibrium , which is a balance between reliance on prior information and openness to new information. At any given time, cognitive equilibrium consists of an ever-growing repertoire of mental representations for objects and experiences. Piaget called each mental representation a schema (all of them together—the plural—were called schemata ). A schema was not merely a concept, but an elaborated mixture of vocabulary, actions, and experience related to the concept. A child’s schema for bird , for example, includes not only the relevant verbal knowledge (like knowing how to define the word “bird”), but also the child’s experiences with birds, pictures of birds, and conversations about birds. As assimilation and accommodation about birds and other flying objects operate together over time, the child does not just revise and add to his vocabulary (such as acquiring a new word, “butterfly”), but also adds and remembers relevant new experiences and actions. From these collective revisions and additions the child gradually constructs whole new schemata about birds, butterflies, and other flying objects. In more everyday (but also less precise) terms, Piaget might then say that “the child has learned more about birds.”

Exhibit 1 diagrams the relationships among the Piagetian version of psychological constructivist learning. Note that the model of learning in the Exhibit is rather “individualistic,” in the sense that it does not say much about how other people involved with the learner might assist in assimilating or accommodating information. Parents and teachers, it would seem, are left lingering on the sidelines, with few significant responsibilities for helping learners to construct knowledge. But the Piagetian picture does nonetheless imply a role for helpful others: someone, after all, has to tell or model the vocabulary needed to talk about and compare birds from airplanes and butterflies! Piaget did recognize the importance of helpful others in his writings and theorizing, calling the process of support or assistance social transmission . But he did not emphasize this aspect of constructivism. Piaget was more interested in what children and youth could figure out on their own, so to speak, than in how teachers or parents might be able to help the young figure out (Salkind, 2004). Partly for this reason, his theory is often considered less about learning and more about development , or long-term change in a person resulting from multiple experiences that may not be planned deliberately. For the same reason, educators have often found Piaget’s ideas especially helpful for thinking about students’ readiness to learn, another one of the lasting educational issues discussed at the beginning of this chapter. We will therefore return to Piaget later to discuss development and its importance for teaching in more detail

Exhibit 1: Learning According to Piaget

Assimilation + Accommodation → Equilibrium → Schemata

Social Constructivism: assisted performance

Unlike Piaget’s orientation to individuals’ thinking in his version of constructivism, some psychologists and educators have explicitly focused on the relationships and interactions between a learner and other individuals who are more knowledgeable or experienced. This framework often is called social constructivism or sociocultural theory . An early expression of this viewpoint came from the American psychologist Jerome Bruner (1960, 1966, 1996), who became convinced that students could usually learn more than had been traditionally expected as long as they were given appropriate guidance and resources. He called such support instructional scaffolding —literally meaning a temporary framework like the ones used to construct buildings and that allow a much stronger structure to be built within it. In a comment that has been quoted widely (and sometimes disputed), Bruner wrote: “We [constructivist educators] begin with the hypothesis that any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development.” (1960, p. 33). The reason for such a bold assertion was Bruner’s belief in scaffolding—his belief in the importance of providing guidance in the right way and at the right time. When scaffolding is provided, students seem more competent and “intelligent,” and they learn more.

Similar ideas were independently proposed by the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1978), whose writing focused on how a child’s or novice’s thinking is influenced by relationships with others who are more capable, knowledgeable, or expert than the learner. Vygotsky made the reasonable proposal that when a child (or novice) is learning a new skill or solving a new problem, he or she can perform better if accompanied and helped by an expert than if performing alone—though still not as well as the expert. Someone who has played very little chess, for example, will probably compete against an opponent better if helped by an expert chess player than if competing against the opponent alone. Vygotsky called the difference between solo performance and assisted performance the zone of proximal development (or ZPD for short)—meaning, figuratively speaking, the place or area of immediate change. From this social constructivist perspective, learning is like assisted performance (Tharp & Gallimore, 1991). During learning, knowledge or skill is found initially “in” the expert helper. If the expert is skilled and motivated to help, then the expert arranges experiences that let the novice to practice crucial skills or to construct new knowledge. In this regard the expert is a bit like the coach of an athlete—offering help and suggesting ways of practicing, but never doing the actual athletic work himself or herself. Gradually, by providing continued experiences matched to the novice learner’s emerging competencies, the expert-coach makes it possible for the novice or apprentice to appropriate (or make his or her own) the skills or knowledge that originally resided only with the expert. These relationships are diagrammed in Exhibit 2.

Exhibit 2: Learning According to Vygotsky

Novice → Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) ← Expert

In both the psychological and social versions of constructivist learning, the novice is not really “taught” so much as simply allowed to learn. But compared to psychological constructivism, social constructivism highlights a more direct responsibility of the expert for making learning possible. He or she must not only have knowledge and skill, but also know how to arrange experiences that make it easy and safe for learners to gain knowledge and skill themselves. These requirements sound, of course, a lot like the requirements for classroom teaching. In addition to knowing what is to be learned, the expert (i.e. the teacher) also has to organize the content into manageable parts, offer the parts in a sensible sequence, provide for suitable and successful practice, bring the parts back together again at the end, and somehow relate the entire experience to knowledge and skills meaningful to the learner already. But of course, no one said that teaching is easy!

The teacher’s role in Psychological and Social Constructivism

As some of the comments above indicate, psychological and social constructivism have differences that suggest different ways for teachers to teach most effectively. The theoretical differences are related to three ideas in particular: the relationship of learning and long-term development, the role or meaning of generalizations and abstractions during development, and the mechanism by which development occurs.

The relationship of learning and long-term development of the child

In general psychological constructivism such as Piaget emphasize the ways that long-term development determines a child’s ability to learn, rather than the other way around. The earliest stages of a child’s life are thought to be rather self-centered and to be dependent on the child’s sensory and motor interactions with the environment. When acting or reacting to his or her surroundings, the child has relatively little language skill initially. This circumstance limits the child’s ability to learn in the usual, school-like sense of the term. As development proceeds, of course, language skills improve and hence the child becomes progressively more “teachable” and in this sense more able to learn. But whatever the child’s age, ability to learn waits or depends upon the child’s stage of development. From this point of view, therefore, a primary responsibility of teachers is to provide a very rich classroom environment, so that children can interact with it independently and gradually make themselves ready for verbal learning that is increasingly sophisticated.

Social constructivists such as Vygotsky, on the other hand, emphasize the importance of social interaction in stimulating the development of the child. Language and dialogue therefore are primary, and development is seen as happening as a result—the converse of the sequence pictured by Piaget. Obviously a child does not begin life with a lot of initial language skill, but this fact is why interactions need to be scaffolded with more experienced experts— people capable of creating a zone of proximal development in their conversations and other interactions. In the preschool years the experts are usually parents; after the school years begin, the experts broaden to include teachers. A teacher’s primary responsibility is therefore to provide very rich opportunities for dialogue, both among children and between individual children and the teacher.

The role of generalizations and abstractions during development

Consistent with the ideas above, psychological constructivism tends to see a relatively limited role for abstract or hypothetical reasoning in the life of children—and even in the reasoning of youth and many adults. Such reasoning is regarded as an outgrowth of years of interacting with the environment very concretely. As explained more fully in the next chapter (“Student development”), elementary-age students can reason, but they are thought to reason only about immediate, concrete objects and events. Even older youth are thought to reason in this way much, or even all of the time. From this perspective a teacher should limit the amount of thinking about abstract ideas that she expects from students. The idea of “democracy,” for example, may be experienced simply as an empty concept. At most it might be misconstrued as an oversimplified, overly concrete idea—as “just” about taking votes in class, for instance. Abstract thinking is possible, according to psychological constructivism, but it emerges relatively slowly and relatively late in development, after a person accumulates considerable concrete experience.

Social constructivism sees abstract thinking emerging from dialogue between a relative novice (a child or youth) and a more experienced expert (a parent or teacher). From this point of view, the more such dialogue occurs, then the more the child can acquire facility with it. The dialogue must, of course, honor a child’s need for intellectual scaffolding or a zone of proximal development. A teacher’s responsibility can therefore include engaging the child in dialogue that uses potentially abstract reasoning, but without expecting the child to understand the abstractions fully at first. Young children, for example, can not only engage in science experiments like creating a “volcano” out of baking soda and water, but also discuss and speculate about their observations of the experiment. They may not understand the experiment as an adult would, but the discussion can begin moving them toward adult-like understandings.

How development occurs

In psychological constructivism, as explained earlier, development is thought to happen because of the interplay between assimilation and accommodation —between when a child or youth can already understand or conceive of, and the change required of that understanding by new experiences. Acting together, assimilation and accommodation continually create new states of cognitive equilibrium . A teacher can therefore stimulate development by provoking cognitive dissonance deliberately: by confronting a student with sights, actions, or ideas that do not fit with the student’s existing experiences and ideas. In practice the dissonance is often communicated verbally, by posing questions or ideas that are new or that students may have misunderstood in the past. But it can also be provoked through pictures or activities that are unfamiliar to students—by engaging students in a community service project, for example, that brings them in contact with people who they had previously considered “strange” or different from themselves.

In social constructivism, as also explained earlier, development is thought to happen largely because of scaffolded dialogue in a zone of proximal development. Such dialogue is by implication less like “disturbing” students’ thinking than like “stretching” it beyond its former limits. The image of the teacher therefore is more one of collaborating with students’ ideas rather than challenging their ideas or experiences. In practice, however, the actual behavior of teachers and students may be quite similar in both forms of constructivism. Any significant new learning requires setting aside, giving up, or revising former learning, and this step inevitably therefore “disturbs” thinking, if only in the short term and only in a relatively minor way.

Implications of constructivism for teaching

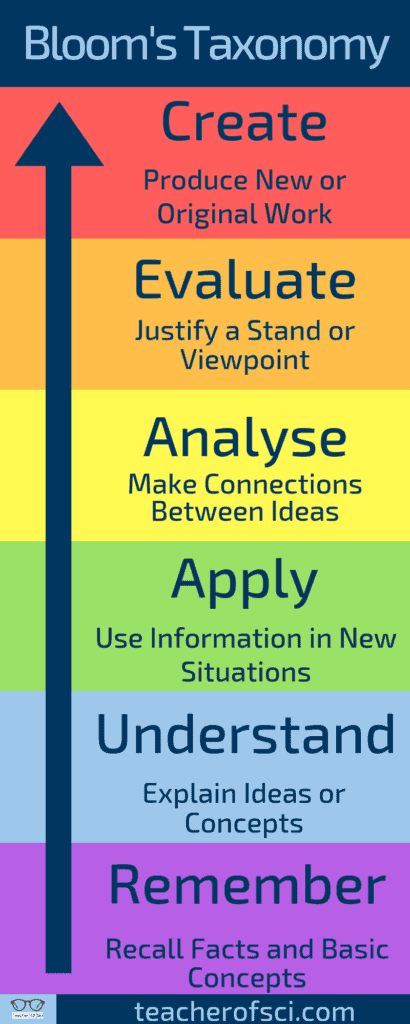

Whether you think of yourself as a psychological constructivist or a social constructivist, there are strategies for helping students help in develop their thinking—in fact the strategies constitute a major portion of this book, and are a major theme throughout the entire preservice teacher education programs. For now, look briefly at just two. One strategy that teachers often find helpful is to organize the content to be learned as systematically as possible, because doing this allows the teacher to select and devise learning activities that are better tailored to students’ cognitive abilities, or that promote better dialogue, or both. One of the most widely used frameworks for organizing content, for example, is a classification scheme proposed by the educator Benjamin Bloom, published with the somewhat imposing title of Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Handbook #1: Cognitive Domain (Bloom, et al., 1956; Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001). Bloom’s taxonomy , as it is usually called, describes six kinds of learning goals that teachers can in principle expect from students, ranging from simple recall of knowledge to complex evaluation of knowledge. (The levels are defined briefly in Error: Reference source not found with examples from Goldilocks and the Three Bears.)

Bloom’s taxonomy makes useful distinctions among possible kinds of knowledge needed by students, and therefore potentially helps in selecting activities that truly target students’ zones of proximal development in the sense meant by Vygotsky. A student who knows few terms for the species studied in biology unit (a problem at Bloom’s knowledge and comprehension levels), for example, may initially need support at remembering and defining the terms before he or she can make useful comparisons among species (Bloom’s analysis level). Pinpointing the most appropriate learning activities to accomplish this objective remains the job of the teacher-expert (that’s you), but the learning itself has to be accomplished by the student. Put in more social constructivist terms, the teacher arranges a zone of proximal development that allows the student to compare species successfully, but the student still has to construct or appropriate the comparisons for him or herself.

A second strategy may be coupled with the first. As students gain experience as students, they become able to think about how they themselves learn best, and you (as the teacher) can encourage such self-reflection as one of your goals for their learning. These changes allow you to transfer some of your responsibilities for arranging learning to the students themselves. For the biology student mentioned above, for example, you may be able not only to plan activities that support comparing species, but also to devise ways for the student to think about how he or she might learn the same information independently. The resulting self-assessment and self-direction of learning often goes by the name of metacognition —an ability to think about and regulate one’s own thinking (Israel, 2005). Metacognition can sometimes be difficult for students to achieve, but it is an important goal for social constructivist learning because it gradually frees learners from dependence on expert teachers to guide their learning. Reflective learners, you might say, become their own expert guides. Like with using Bloom’s taxonomy, though, promoting metacognition and self-directed learning is important enough that I will come back to it later in more detail (in the chapter on “Facilitating complex thinking”).

By assigning a more active role to expert helpers—which by implication includes teachers—than does the psychological constructivism, social constructivism may be more complete as a description of what teachers usually do when actually busy in classrooms, and of what they usually hope students will experience there. As we will see in the next chapter, however, there are more uses for a theory than its description of moment-to-moment interactions between teacher and students. As explained there, some theories can be helpful for planning instruction rather than for doing it. It turns out that this is the case for psychological constructivism, which offers important ideas about the appropriate sequencing of learning and development. This fact makes the psychological constructivism valuable in its own way, even though it (and a few other learning theories as well) may seem to omit mentioning teachers, parents, or experts in detail. So do not make up your mind about the relative merits of different learning theories yet!

Alberto, P. & Troutman, A. (2005). Applied behavior analysis for teachers, 7th edition . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Anderson, L. & Krathwohl, D. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives . New York: Longman.

Bruner, J. (1960). The process of education . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dewey, J. (1938/1998). How we think . Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Ferster, C., Skinner, B. F., Cheney, C., Morse, W., & Dews, D. Schedules of reinforcement . New York: Copley Publishing Group.

Fosnot, C. (Ed.). (2005). Constructivism: Theory, perspectives, and practice, 2nd edition . New York: Teachers College Press.

Gruber, H. & Voneche, J. (Eds.). (1995). The essential Piaget. New York: Basic Books.

Israel, S. (Ed.). (2005). Metacognition in literacy learning. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Mazur, J. (2005). Learning and behavior, 6th edition . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Piaget, J. (2001). The psychology of intelligence . London, UK: Routledge.

Rockmore, T. (2005). On constructivist epistemology . Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Salkind, N. (2004). An introduction to theories of human development . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms . New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Skinner, B. F. (1948). Walden Two . New York: Macmillan.

Skinner, B. F. (1988). The selection of behavior: The operant behaviorism of B. F. Skinner . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tharp, R. & Gallimore, R. (1991). Rousing minds to life: Teaching, learning, and schooling in social context . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Privacy Policy

- QUICK LINKS

- How to enroll

- Career services

5 educational learning theories and how to apply them

By Michael Feder

This article has been vetted by University of Phoenix's editorial advisory committee. Read more about our editorial process.

Reviewed by Pamela M. Roggeman , EdD, Dean, College of Education

At a glance

- There are five primary educational learning theories : behaviorism, cognitive, constructivism, humanism, and connectivism.

- Additional learning theories include transformative, social, and experiential .

- Understanding learning theories can result in a variety of outcomes , from improving communication between students and teachers to determining what students learn.

- Learn more about how University of Phoenix can aid you in your educational journey at phoenix.edu .

This article was updated on 12/4/2023.

How educational learning theories can impact your education

Teaching and learning may appear to be a universal experience. After all, everyone goes to school and learns more or less the same thing, right? Well, not quite.

As the prolific number of educational theorists in learning suggests, there’s actually an impressive variety of educational approaches to the art and science of teaching. Many of them have been pioneered by educational theorists who’ve studied the science of learning to determine what works best and for whom.

"Learning is defined as a process that brings together personal and environmental experiences and influences for acquiring, enriching or modifying one’s knowledge, skills, values, attitudes, behavior and worldviews," notes the International Bureau of Education . "Learning theories develop hypotheses that describe how this process takes place."

Generally, there are five widely accepted learning theories teachers rely on:

- Behaviorism learning theory

- Cognitive learning theory

- Constructivism learning theory

- Humanism learning theory

- Connectivism learning theory

Educational theorists, teachers, and experts believe these theories can inform successful approaches for teaching and serve as a foundation for developing lesson plans and curriculum.

Learn more about degree offerings at University of Phoenix!

What are learning theories?

Theories in education didn’t begin in earnest until the early 20th century, but curiosity about how humans learn dates back to the ancient Greek philosophers Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. They explored whether knowledge and truth could be found within oneself (rationalism) or through external observation (empiricism).

By the 19th century, psychologists began to answer this question with scientific studies. The goal was to understand objectively how people learn and then develop teaching approaches accordingly.

In the 20th century, the debate among educational theorists centered on behaviorist theory versus cognitive psychology. Or, in other words, do people learn by responding to external stimuli or by using their brains to construct knowledge from external data?

The five educational learning theories

Today, much research, study, and debate have given rise to the following five learning theories:

Why are learning theories important?

It is part of the human condition to crave knowledge. Consequently, numerous scientists, psychologists, and thought leaders have devoted their careers to studying learning theories. Understanding how people learn is a critical step in optimizing the learning process.

It is for this reason that teacher colleges or educator preparation programs spend so much time having teacher candidates study human development and multiple learning theories. Foundational knowledge of how humans learn, and specifically how a child learns and develops cognitively, is essential for all educators to be their most effective instructors in the classroom.

Pamela Roggeman, EdD, dean of University of Phoenix’s College of Education , explains her take on the role learning theory plays in preparing teachers:

"Just as no two people are the same, no two students learn in the exact the same way or at the exact same rate. Effective educators need to be able to pivot and craft instruction that meets the needs of the individual student to address the needs of the ‘whole child.’ Sound knowledge in multiple learning theories is a first step to this and another reason why great teachers work their entire careers to master both the art and the science of teaching."

Although espousing a particular learning theory isn’t necessarily required in most teaching roles, online learning author and consultant Tony Bates points out that most teachers tend to follow one or another theory, even if it’s done unconsciously.

So, whether you’re an aspiring or experienced teacher, a student, or a parent of a student (or some combination thereof), knowing more about each theory can make you more effective in the pursuit of knowledge.

Are there other theories in education?

Like students themselves, learning theories in education are varied and diverse. In addition to the five theories outlined above, there are still more options, including:

- Transformative learning theory: This theory is particularly relevant to adult learners. It posits that new information can essentially change our worldviews when our life experience and knowledge are paired with critical reflection.

- Social learning theory: This theory incorporates some of the tacit tenets of peer pressure. Specifically, students observe other students and model their own behavior accordingly. Sometimes it’s to emulate peers; other times it’s to distinguish themselves from peers. Harnessing the power of this theory involves getting students’ attention, focusing on how students can retain information, identifying when it’s appropriate to reproduce a previous behavior, and determining students’ motivation.

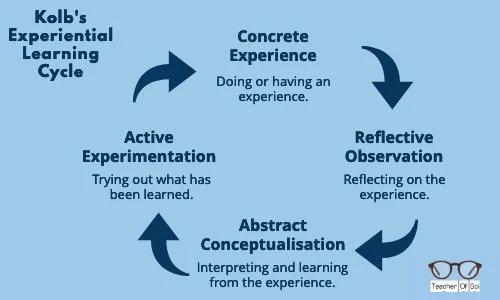

- Experiential learning theory: There are plenty of clichés and parables about teaching someone something by doing it, although it wasn’t until the early 1980s that it became an official learning theory. This approach emphasizes both learning about something and experiencing it so that students can apply knowledge in real-world situations.

How educational theories influence learning

Educational theories influence learning in a variety of ways. For teachers, learning theory examples can impact their approach to instruction and classroom management. Finding the right approach (even if it’s combining two or more learning theories) can make the difference between an effective and inspiring classroom experience and an ineffective one.

Applied learning theories directly impact a classroom experience in a variety of ways, such as:

- Providing students with structure and a comfortable, steady environment.

- Helping educators, administrators, students and parents align on goals and outcomes .

- Empowering teachers to be, as Bates says, "in a better position to make choices about how to approach their teaching in ways that will best fit the perceived needs of their students."

- Impacting how and what a person learns.

- Helping outsiders (colleges, testing firms, etc.) determine what kind of education you had or are receiving.

- Allowing students a voice in determining how the class will be managed .

- Deciding if instruction will be mostly teacher-led or student-led .

- Determining how much collaboration will happen in a classroom.

How to apply learning theories

So, how do learning theories apply in the real world? Education is an evolving field with a complicated future . And, according to Roggeman, the effects of applied educational theory can be long-lasting.

She explains:

"The learning theories we experienced as a student influence the type of work environment we prefer as adults. For example, if one experienced classrooms based heavily on social learning during the K-12 years, as an adult, one may be very comfortable in a highly collaborative work environment. Reflection on one’s own educational history might serve as an insightful tool as to one’s own fulfillment in the workplace as an adult."

Educational theories have come a long way since the days of Socrates and even the pioneers of behaviorism and cognitivism. And while learning theories will no doubt continue to evolve, teachers and students alike can reap the benefits of this evolution as we continue to develop our understanding of how humans most effectively learn.

Educational theories of learning are one thing. Adult learning theories are another. Learn more on our blog.

Ready to put theory into practice? Explore Foundations in Virtual Teaching at University of Phoenix!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael Feder is a content marketing specialist at University of Phoenix, where he researches and writes on a variety of topics, ranging from healthcare to IT. He is a graduate of the Johns Hopkins University Writing Seminars program and a New Jersey native!

want to read more like this?

What Is a Director of Curriculum and Instruction?

Online degrees.

August 31, 2023 • 6 minutes

Comparing Early Childhood Education vs. Elementary Education

March 11, 2023 • 6 minutes

What Can You Do With an Associate Degree?

July 19, 2022 • 12 minutes

- Publications

Schools of the Future: Defining New Models of Education for the Fourth Industrial Revolution

World Economic Forum reports may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License , and in accordance with our Terms of Use .

Further reading All related content

How can we prepare students for the Fourth Industrial Revolution? 5 lessons from innovative schools around the world

Here's how educational institutions can prepare students for the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Learning through play: how schools can educate students through technology

Learning through play has a critical role in education. Tech can help.

Global Education in Context: Four Models, Four Lessons

- Share article

Editor’s Intro: As part of a National Geographic Society -funded research project, a team of researchers is documenting how school systems are approaching global learning. Laura Engel , associate professor of international education and international affairs, George Washington University; Heidi Gibson, research assistant, George Washington University ; and Kayla Gatalica, manager, Global Programs , District of Columbia public schools, share the lessons they have learned.

The need to build the knowledge, skills, and dispositions required for the 21 st -century globalized world is well-recognized by education policymakers, researchers, and practitioners. Yet too often, there is a lack of a coherent picture of what global education looks like in the United States. The decentralized nature of the U.S. education system means that in many districts and states global education is built from the ground up. Some laudable projects have aimed to share initiatives across states and to connect state leaders. One example is the States Network on International Education, created by the Asia Society and Longview Foundation, currently involving 25 member states committed to building capacity in global education. Interactive online tools like Mapping the Nation and Global Education Certificates allow researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to learn more about district- and state-level initiatives.

Four Models

To better understand global education in context, a team from George Washington University (GW) and the District of Columbia public schools (DCPS) made a series of virtual and in-person site visits to North Carolina, Virginia, and Illinois. During each of the site visits, our team had the opportunity to hear perspectives from global education leaders, teachers, administrators, students, organizations, and policymakers. We also developed an extended case study focused on the work of the DCPS Global Education team, providing a fourth context from which to better understand global education policy and practice.

Each of these four contexts reveals a different model of global education. In North Carolina, an example of a top-down approach, the state board of education adopted a framework for global learning and created a process to assess and recognize efforts by districts, schools, and educators. North Carolina’s extensive rubric for schools and districts awards “global-ready” designations and also allows schools and districts to see where they fall on a global-ready continuum ranging from “early” to “model.”

In Illinois, a group of Naperville Central High School teachers leveraged district support and successfully pushed for legislation establishing the Illinois Global Scholars Certificate . As part of this push, global-learning advocates across the state joined forces to build a statewide global education network.

Virginia’s initiatives are currently more localized, with individual districts championing globally-focused educational approaches, especially related to schools’ study abroad and exchange programs. Advocates have also leveraged state programs, such as the Governor’s World Language Academies, and new policies, like the Profile of a Graduate initiative, in support of a focus on developing students’ skills for a global future.

Lastly, within our team, we have perspectives on the robust global programming in DCPS, which reveals a multipronged approach to global education. The DCPS Global Education team manages districtwide programs like International Food Days and fully funded study abroad as well as school-specific programs such as world-language instruction and Global Studies Schools.

Four Lessons Learned

These four distinct cases provide insights into the diversity of global education practice within the United States. They also offer common lessons on how to make progress toward global education goals:

1) The Power of the Champion Behind every example of a successful global education program, policy, or practice were champions—often individuals with the power and capacity to leverage change—who sought to invest in global education for all schools and students. In each of the four contexts, this role varied. For example, in the case of Illinois, two highly respected teachers have spurred a grassroots statewide movement, whereas, in North Carolina, global education leadership came from a state-level champion, providing district supports such as resources and training.

2) Leveraging Partnerships Movements in global education in each of the four contexts had much to do with the leveraging of partnerships. These partnerships involved a range of different stakeholders, including the business community, fellow schools and districts, nonprofit organizations, and the higher education community. The function of partnerships varied as well. In the District of Columbia and Virginia, for instance, partners provided global education opportunities, such as working with local embassies to give students access to experiential learning. In North Carolina, partners helped facilitate teacher exchange by sourcing educators who brought global perspectives to the classroom.

3) Developing and Telling the Story Experienced global education advocates know that generating support for global-learning initiatives often involves pitching these programs to the right person at the right time in the right way. Policymakers who have had transformative international experiences, such as DCPS’ former Chancellor Kaya Henderson’s time spent studying abroad, are more likely to see the value of global education. Strategic use of existing policies, such as tying new global education initiatives to Virginia’s Portrait of a Graduate requirements, can help convince district leadership. In other cases, strategic thinking is needed about the best level of governance to leverage change. In Illinois, after considering a district-level approach, advocates realized they would get better traction at the state level. Building support requires a canny assessment of how to leverage existing policies and attitudes, as well as understanding how to best explain the importance of global education.

4) Building a Network In each of the four contexts, we learned the value of cohesive networks in creating opportunities and spaces for global education policy, practice, and programs. These are cross-curricular, as well as across geographical boundaries. In Virginia, international approaches have often been confined to world-language classrooms, but advocates are beginning to reach out to other curricular areas for a more interdisciplinary approach. District and state leaders frequently remarked on the power of sharing their approaches and practices with others. By building strong networks across the state, such as the one in Illinois, advocates were able to push for change.

Across the four contexts and our lessons learned, there is a clear value added when district and state leaders connect and share practices, policies, and research about global education in K-12 U.S. settings. To further develop such cross-cutting conversations, we launched the K12 Global Forum, which hosted an inaugural convening last year at the United States Institute of Peace in Washington, D.C. We look forward to future convenings to continue to share information and advice with each other.

Connect with the authors and Heather on Twitter.

Image created on Pablo .

The opinions expressed in Global Learning are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

15 Learning Theories in Education (A Complete Summary)

So what are educational learning theories and how can we use them in our teaching practice? There are so many out there, how do we know which are still relevant and which will work for our classes?

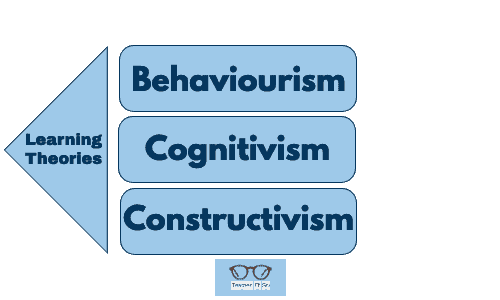

There are 3 main schemas of learning theories; Behaviorism, Cognitivism and Constructivism. In this article you will find a breakdown of each one and an explanation of the 15 most influential learning theories; from Vygotsky to Piaget and Bloom to Maslow and Bruner.

Swimming through treacle!

That’s what it feels like when you are trying to sort through and make sense of the vast amount of learning theories we have at our disposal.

Way back in ancient Greece, the philosopher, Plato , first pondered the question “How does an individual learn something new if the subject itself is new to them” (ok, so I’m paraphrasing, my ancient Greek isn’t very good!).

Since Plato, many theorists have emerged, all with their different take on how students learn. Learning theories are a set of principles that explain how best a student can acquire, retain and recall new information.

In this complete summary, we will look at the work of the following learning theorists.

Despite the fact there are so many educational theorists, there are three labels that they all fall under. Behaviorism , Cognitivism and Constructivism .

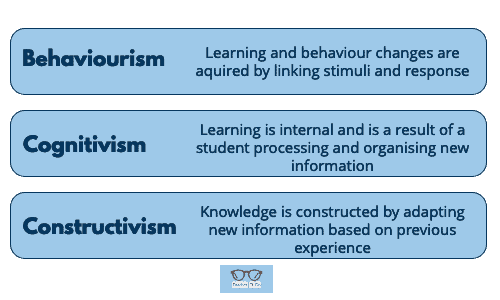

Behaviorism

Behaviorism is based on the idea that knowledge is independent and on the exterior of the learner. In a behaviorist’s mind, the learner is a blank slate that should be provided with the information to be learnt.

Through this interaction, new associations are made and thus learning occurs. Learning is achieved when the provided stimulus changes behavior. A non-educational example of this is the work done by Pavlov .

Through his famous “salivating dog” experiment, Pavlov showed that a stimulus (in this case ringing a bell every time he fed the dog) caused the dog to eventually start salivating when he heard a bell ring.

The dog associated the bell ring with being provided with food so any time a bell was rung the dog started salivating, it had learnt that the noise was a precursor to being fed.

I use a similar approach to classroom management.

I adapt my body language .

I have taught my students that if I stand in a specific place in the classroom with my arms folded, they know that I’m getting frustrated with the level of noise and they start to quieten down or if I sit cross-legged on my desk, I’m about to say something important, supportive and they should listen because it affects them directly.

Behaviorism involves repeated actions, verbal reinforcement and incentives to take part. It is great for establishing rules, especially for behavior management.

Cognitivism

In contrast to behaviorism, cognitivism focuses on the idea that students process information they receive rather than just responding to a stimulus, as with behaviorism.

There is still a behavior change evident, but this is in response to thinking and processing information.

Cognitive theories were developed in the early 1900s in Germany from Gestalt psychology by Wolfgang Kohler. In English, Gestalt roughly translates to the organization of something as a whole, that is viewed as more than the sum of its individual parts.

Cognitivism has given rise to many evidence based education theories, including cognitive load theory , schema theory and dual coding theory as well as being the basis for retrieval practice.

In cognitivism theory, learning occurs when the student reorganizes information, either by finding new explanations or adapting old ones.

This is viewed as a change in knowledge and is stored in the memory rather than just being viewed as a change in behavior. Cognitive learning theories are mainly attributed to Jean Piaget .

Examples of how teachers can include cognitivism in their classroom include linking concepts together, linking concepts to real-world examples, discussions and problem-solving.

Constructivism

Constructivism is based on the premise that we construct learning new ideas based on our own prior knowledge and experiences. Learning, therefore, is unique to the individual learner. Students adapt their models of understanding either by reflecting on prior theories or resolving misconceptions.

Students need to have a prior base of knowledge for constructivist approaches to be effective. Bruner’s spiral curriculum (see below) is a great example of constructivism in action.

As students are constructing their own knowledge base, outcomes cannot always be anticipated, therefore, the teacher should check and challenge misconceptions that may have arisen. When consistent outcomes are required, a constructivist approach may not be the ideal theory to use.

Examples of constructivism in the classroom include problem-based learning, research and creative projects and group collaborations.

1. Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Piaget is an interesting character in Psychology. His theory of learning differs from many others in some important ways:

First, he focuses exclusively on children; Second, he talks about development (not learning per se) and Third, it’s a stage theory, not a linear progression theory. OK, so what’s he on about?

Well, there are some basic ideas to get your head around and some stages to understand too. The basic ideas are:

- Schemas : The building blocks of knowledge.

- Adaptation processes : These allow the transition from one stage to another. He called these: Equilibrium, Assimilation and Accommodation.

- Stages of Cognitive development : Sensorimotor; Preoperational; Concrete Operational; Formal Operational.

So here’s how it goes. Children develop Schemas of knowledge about the world. These are clusters of connected ideas about things in the real world that allow the child to respond accordingly.

When the child has developed a working Schema that can explain what they perceive in the world, that Schema is in a state of Equilibrium .

When the child uses the schema to deal with a new thing or situation, that Schema is in Assimilation and Accommodation happens when the existing Schema isn’t up to the job of explaining what’s going on and needs to be changed.

Once it’s changed, it returns to Equilibrium and life goes on. Learning is, therefore, a constant cycle of Assimilation; Accommodation; Equilibrium; Assimilation and so on…

All that goes through the 4 Stages of Cognitive Development , which are defined by age:

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

The Sensorimotor Stage runs from birth to 2 years and the child spends their time learning basic Schemas and Object Permanence (the idea that something still exists when you can’t see it).

The Preoperational Stage runs from 2 years to 7 years and the child develops more Schemas and the ability to think Symbolically (the idea that one thing can stand for another; words for example, or objects). At this point, children still struggle with Theory of Mind (Empathy) and can’t really get their head around the viewpoints of others.

The Concrete Operational Stage runs from 7 years to 11 years and this is the Stage when children start to work things out in their head rather than physically in the real world. They also develop the ability to Conserve (understand that something stays the same quantity even if it looks different).

The Formal Operational Stage runs from 11 years into adulthood and this is where abstract thought develops, as does logic and cool stuff like hypothesis testing.

According to Piaget, the whole process is active and requires the rediscovery and reconstructing of knowledge across the entire process of Stages.

Understanding the Stage a child is in informs what they should be presented with based on what they can and cannot do at the Stage they’re in.

Piaget’s work on cognitivism has given rise to some brilliant work from people like John Sweller who developed the fantastic Cognitive Load Theory and John Flavell’s work on metacognition

2. Vygotsky’s Theory of Learning

Vygotsky takes a different approach to Piaget’s idea that development precedes learning.

Instead, he reckons that social learning is an integral part of cognitive development and it is culture, not developmental Stage that underlies cognitive development. Because of that, he argues that learning varies across cultures rather than being a universal process driven by the kind of structures and processes put forward by Piaget.

Zone of Proximal Development

He makes a big deal of the idea of the Zone of Proximal Development in which children and those they are learning from co-construct knowledge. Therefore, the social environment in which children learn has a massive impact on how they think and what they think about.

They also differ in how they view language. For Piaget, thought drives language but for Vygotsky, language and thought become intertwined at about 3 years and become a sort of internal dialogue for understanding the world.

And where do they get that from? Their social environment of course, which contains all the cognitive/linguistic skills and tools to understand the world.

Vygotsky talks about Elementary Mental Functions , by which he means the basic cognitive processes of Attention, Sensation, Perception and Memory.

By using those basic tools in interactions with their sociocultural environment, children sort of improve them using whatever their culture provides to do so. In the case of Memory, for example, Western cultures tend towards note-taking, mind-maps or mnemonics whereas other cultures may use different Memory tools like storytelling.

In this way, a cultural variation of learning can be described quite nicely.

What are crucial in this learning theory are the ideas of Scaffolding, the Zone of Proximal Development ( ZPD ) and the More Knowledgeable Other ( MKO ). Here’s how all that works:

More Knowledgeable Other

The MKO can be (but doesn’t have to be) a person who literally knows more than the child. Working collaboratively, the child and the MKO operate in the ZPD, which is the bit of learning that the child can’t do on their own.

As the child develops, the ZPD gets bigger because they can do more on their own and the process of enlarging the ZPD is called Scaffolding .

Vygotsky Scaffolding

Knowing where that scaffold should be set is massively important and it’s the MKO’s job to do that so that the child can work independently AND learn collaboratively.

For Vygotsky, language is at the heart of all this because a) it’s the primary means by which the MKO and the child communicate ideas and b) internalizing it is enormously powerful in cementing understanding about the world.

That internalization of speech becomes Private Speech (the child’s “inner voice”) and is distinct from Social Speech , which occurs between people.

Over time, Social Speech becomes Private Speech and Hey Presto! That’s Learning because the child is now collaborating with themselves!

The bottom line here is that the richer the sociocultural environment, the more tools will be available to the child in the ZPD and the more Social Speech they will internalize as Private Speech. It doesn’t take a genius to work out, therefore, that the learning environment and interactions are everything.

Scaffolding is also an integral part of Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction .

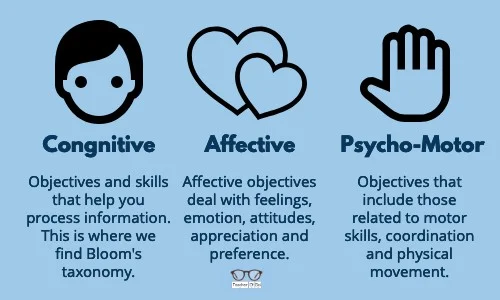

3. Bloom’s Domains of Learning

In 1956, American educational psychologist, Benjamin Bloom, first proposed three domains of learning; cognitive, affective and psycho-motor . Bloom worked in collaboration with David Krathwohl and Anne Harrow throughout the 1950s-70s on the three domains.

The Cognitive Domain (Bloom’s Taxonomy)

This was the first domain to be proposed in 1956 and it focuses on the idea that objectives that are related to cognition could be divided into subdivisions and ranked in order of cognitive difficulty.

These ranked subdivisions are what we commonly refer to as Bloom’s taxonomy . The original subdivisions are as follows (knowledge is the lowest with evaluation being the most cognitively difficult):

- Understanding

- Application

However, there was a major revision of the subdivisions in 2000-01 by Bloom’s original partner, David Krathwohl and his colleague, Lorin Anderson (Anderson was a former student of Bloom’s).

The highlights of this revision were switching names of the subdivisions from nouns to verbs, thus making them easier to use when curriculum and lesson planning .

The other main change was the order of the top two subdivisions was reversed. The updated taxonomy is as follows:

The Affective Domain

The affective domain (sometimes referred to as the feeling domain) is concerned with feelings and emotions and also divides objectives into hierarchical subcategories. It was proposed by Krathwohl and Bloom in 1964.

The affective domain is not usually used when planning for math and sciences as feelings and emotion are not relevant for those subjects. However, for educators of arts and language, the inclusion of the affective domain is imperative wherever possible.

The ranked domain subcategories range from “receiving” at the lower end up to “characterization” at the top. The full ranked list is as follows:

- Receiving. Being aware of an external stimulus (feel, sense, experience).

- Responding. Responding to the external stimulus (satisfaction, enjoyment, contribute)

- Valuing. Referring to the student’s belief or appropriation of worth (showing preference or respect).

- Organization. The conceptualizing and organizing of values (examine, clarify, integrate.)

- Characterization. The ability to practice and act on their values. (Review, conclude, judge).

The Psychomotor Domain

The psychomotor domain refers to those objectives that are specific to reflex actions interpretive movements and discreet physical functions.

A common misconception is that physical objectives that support cognitive learning fit the psycho-motor label, for example; dissecting a heart and then drawing it.

While these are physical (kinesthetic) actions, they are a vector for cognitive learning, not psycho-motor learning.

Psychomotor learning refers to how we use our bodies and senses to interact with the world around us, such as learning how to move our bodies in dance or gymnastics.

Anita Harrow classified different types of learning in the psycho-motor domain from those that are reflex to those that are more complex and require precise control.

- Reflex movements. These movements are those that we possess from birth or appear as we go through puberty. They are automatic, that is they do not require us to actively think about them e.g. breathing, opening and closing our pupils or shivering when cold.

- Fundamental movements. These are those actions that are the basic movements, running, jumping, walking etc and commonly form part of more complex actions such as playing a sport.

- Perceptual abilities. This set of abilities features those that allow us to sense the world around us and coordinate our movements in order to interact with our environment. They include visual, audio and tactile actions.

- Physical abilities. These abilities refer to those involved with strength, endurance, dexterity and flexibility etc.

- Skilled movements. Objectives set in this area are those that include movements learned for sport (twisting the body in high diving or trampolining), dance or playing a musical instrument (placing fingers on guitar strings to produce the correct note). It is these movements that we sometimes use the layman’s term “muscle memory”.

- Non-discursive communication. Meaning communication without writing, non-discursive communication refers to physical actions such as facial expressions, posture and gestures.

4. Gagné’s Conditions of Learning

Robert Mills Gagné was an American educational psychologist who, in 1965 published his book “The Conditions of Learning”. In it, he discusses the analysis of learning objectives and how the different classes of objective require specific teaching methods.

He called these his 5 conditions of learning, all of which fall under the cognitive, affective and psycho-motor domains discussed earlier.

Gagné’s 5 Conditions of Learning

- Verbal information (Cognitive domain)

- Intellectual skills (Cognitive domain)

- Cognitive strategies (Cognitive domain)

- Motor skills (Psycho-Motor domain)

- Attitudes (Affective domain)

Gagné’s 9 Levels of Learning

To achieve his five conditions of learning, Gagné believed that learning would take place when students progress through nine levels of learning and that any teaching session should include a sequence of events through all nine levels. The idea was that the nine levels of learning activate the five conditions of learning and thus, learning will be achieved.

- Gain attention.

- Inform students of the objective.

- Stimulate recall of prior learning.

- Present the content.

- Provide learning guidance.

- Elicit performance (practice).

- Provide feedback.

- Assess performance.

- Enhance retention and transfer to the job.

Benefits of Gagné’s Theory

Used in conjunction with Bloom’s taxonomy, Gagné’s nine levels of learning provide a framework that teachers can use to plan lessons and topics. Bloom provides the ability to set objectives that are differentiated and Gagné gives a scaffold to build your lesson on.

5. Jerome Bruner

Bruner’s Spiral Curriculum (1960)

Cognitive learning theorist, Jerome Bruner based the spiral curriculum on his idea that “ We begin with the hypothesis that any subject can be taught in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development” .

In other words, he meant that even very complex topics can be taught to young children if structured and presented in the right way. The spiral curriculum is based on three key ideas.

- Students revisit the same topic multiple times throughout their school career. This reinforces the learning each time they return to the subject.

- The complexity of the topic increases each time a student revisits it. This allows progression through the subject matter as the child’s cognitive ability develops with age.

- When a student returns to a topic, new ideas are linked with ones they have previously learned. The student’s familiarity with the keywords and ideas enables them to grasp the more difficult elements of the topic in a stronger way.

Bruner’s 3 Modes of Representation (1966)