Home Blog Design Understanding Data Presentations (Guide + Examples)

Understanding Data Presentations (Guide + Examples)

In this age of overwhelming information, the skill to effectively convey data has become extremely valuable. Initiating a discussion on data presentation types involves thoughtful consideration of the nature of your data and the message you aim to convey. Different types of visualizations serve distinct purposes. Whether you’re dealing with how to develop a report or simply trying to communicate complex information, how you present data influences how well your audience understands and engages with it. This extensive guide leads you through the different ways of data presentation.

Table of Contents

What is a Data Presentation?

What should a data presentation include, line graphs, treemap chart, scatter plot, how to choose a data presentation type, recommended data presentation templates, common mistakes done in data presentation.

A data presentation is a slide deck that aims to disclose quantitative information to an audience through the use of visual formats and narrative techniques derived from data analysis, making complex data understandable and actionable. This process requires a series of tools, such as charts, graphs, tables, infographics, dashboards, and so on, supported by concise textual explanations to improve understanding and boost retention rate.

Data presentations require us to cull data in a format that allows the presenter to highlight trends, patterns, and insights so that the audience can act upon the shared information. In a few words, the goal of data presentations is to enable viewers to grasp complicated concepts or trends quickly, facilitating informed decision-making or deeper analysis.

Data presentations go beyond the mere usage of graphical elements. Seasoned presenters encompass visuals with the art of storytelling with data, so the speech skillfully connects the points through a narrative that resonates with the audience. Depending on the purpose – inspire, persuade, inform, support decision-making processes, etc. – is the data presentation format that is better suited to help us in this journey.

To nail your upcoming data presentation, ensure to count with the following elements:

- Clear Objectives: Understand the intent of your presentation before selecting the graphical layout and metaphors to make content easier to grasp.

- Engaging introduction: Use a powerful hook from the get-go. For instance, you can ask a big question or present a problem that your data will answer. Take a look at our guide on how to start a presentation for tips & insights.

- Structured Narrative: Your data presentation must tell a coherent story. This means a beginning where you present the context, a middle section in which you present the data, and an ending that uses a call-to-action. Check our guide on presentation structure for further information.

- Visual Elements: These are the charts, graphs, and other elements of visual communication we ought to use to present data. This article will cover one by one the different types of data representation methods we can use, and provide further guidance on choosing between them.

- Insights and Analysis: This is not just showcasing a graph and letting people get an idea about it. A proper data presentation includes the interpretation of that data, the reason why it’s included, and why it matters to your research.

- Conclusion & CTA: Ending your presentation with a call to action is necessary. Whether you intend to wow your audience into acquiring your services, inspire them to change the world, or whatever the purpose of your presentation, there must be a stage in which you convey all that you shared and show the path to staying in touch. Plan ahead whether you want to use a thank-you slide, a video presentation, or which method is apt and tailored to the kind of presentation you deliver.

- Q&A Session: After your speech is concluded, allocate 3-5 minutes for the audience to raise any questions about the information you disclosed. This is an extra chance to establish your authority on the topic. Check our guide on questions and answer sessions in presentations here.

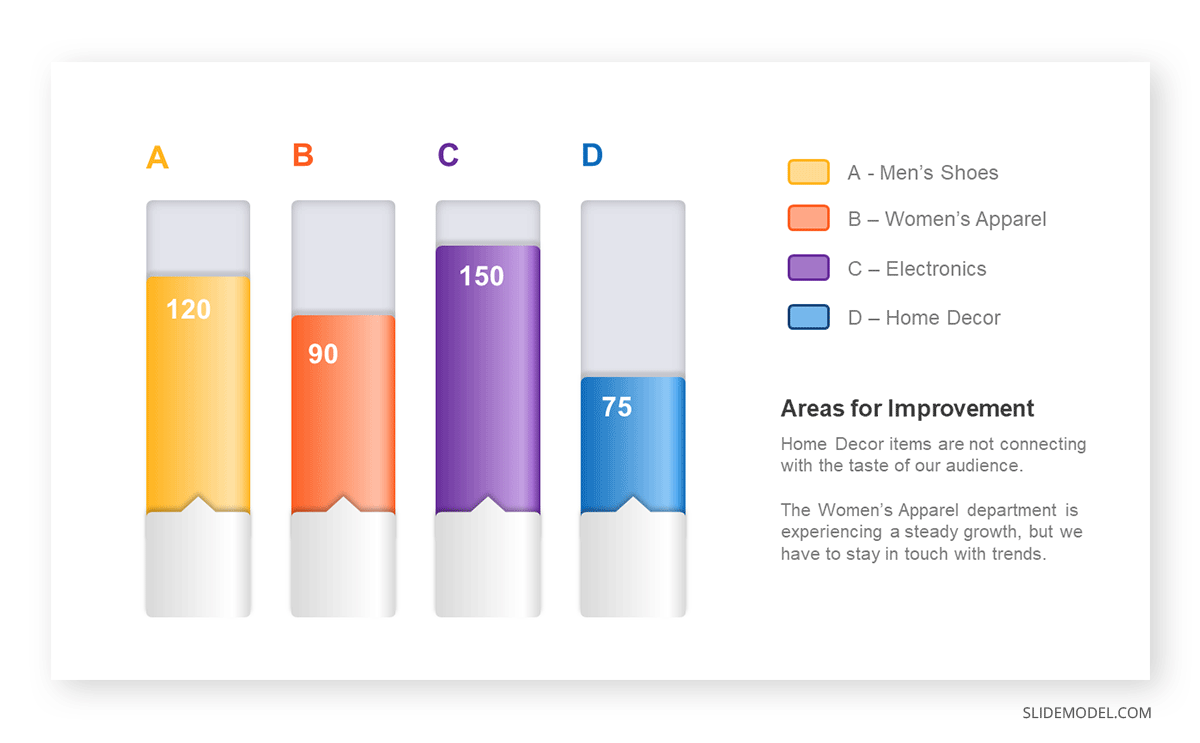

Bar charts are a graphical representation of data using rectangular bars to show quantities or frequencies in an established category. They make it easy for readers to spot patterns or trends. Bar charts can be horizontal or vertical, although the vertical format is commonly known as a column chart. They display categorical, discrete, or continuous variables grouped in class intervals [1] . They include an axis and a set of labeled bars horizontally or vertically. These bars represent the frequencies of variable values or the values themselves. Numbers on the y-axis of a vertical bar chart or the x-axis of a horizontal bar chart are called the scale.

Real-Life Application of Bar Charts

Let’s say a sales manager is presenting sales to their audience. Using a bar chart, he follows these steps.

Step 1: Selecting Data

The first step is to identify the specific data you will present to your audience.

The sales manager has highlighted these products for the presentation.

- Product A: Men’s Shoes

- Product B: Women’s Apparel

- Product C: Electronics

- Product D: Home Decor

Step 2: Choosing Orientation

Opt for a vertical layout for simplicity. Vertical bar charts help compare different categories in case there are not too many categories [1] . They can also help show different trends. A vertical bar chart is used where each bar represents one of the four chosen products. After plotting the data, it is seen that the height of each bar directly represents the sales performance of the respective product.

It is visible that the tallest bar (Electronics – Product C) is showing the highest sales. However, the shorter bars (Women’s Apparel – Product B and Home Decor – Product D) need attention. It indicates areas that require further analysis or strategies for improvement.

Step 3: Colorful Insights

Different colors are used to differentiate each product. It is essential to show a color-coded chart where the audience can distinguish between products.

- Men’s Shoes (Product A): Yellow

- Women’s Apparel (Product B): Orange

- Electronics (Product C): Violet

- Home Decor (Product D): Blue

Bar charts are straightforward and easily understandable for presenting data. They are versatile when comparing products or any categorical data [2] . Bar charts adapt seamlessly to retail scenarios. Despite that, bar charts have a few shortcomings. They cannot illustrate data trends over time. Besides, overloading the chart with numerous products can lead to visual clutter, diminishing its effectiveness.

For more information, check our collection of bar chart templates for PowerPoint .

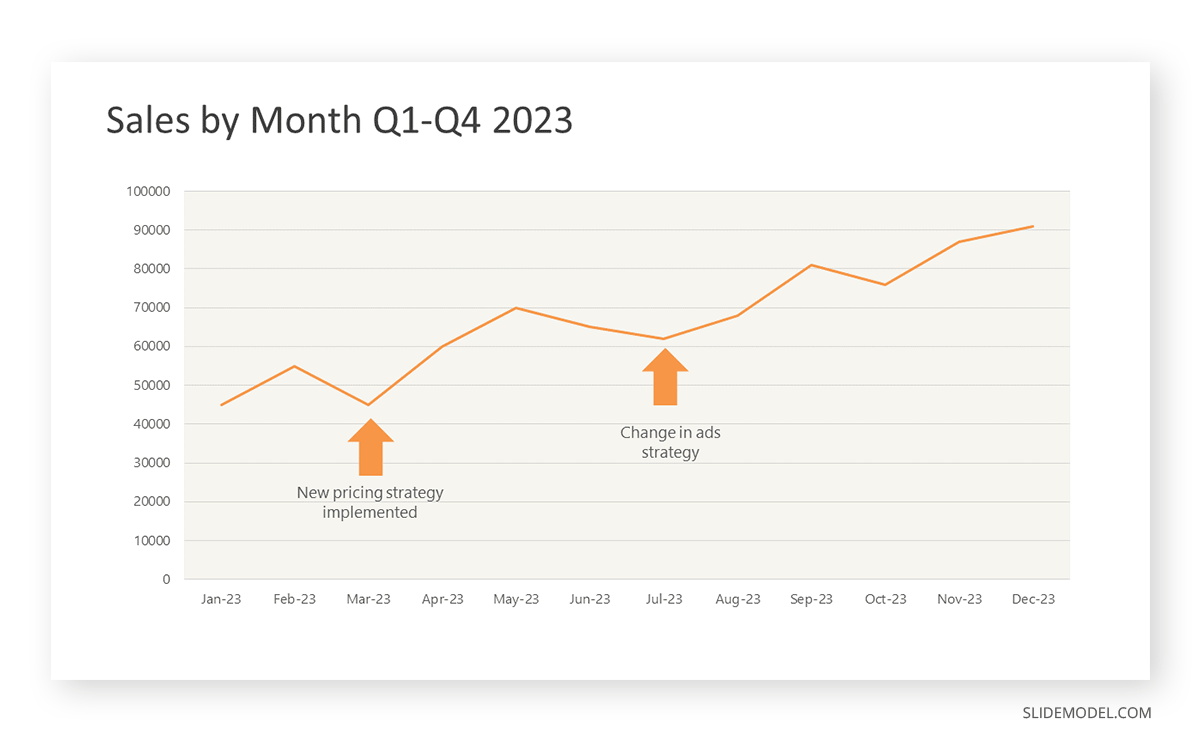

Line graphs help illustrate data trends, progressions, or fluctuations by connecting a series of data points called ‘markers’ with straight line segments. This provides a straightforward representation of how values change [5] . Their versatility makes them invaluable for scenarios requiring a visual understanding of continuous data. In addition, line graphs are also useful for comparing multiple datasets over the same timeline. Using multiple line graphs allows us to compare more than one data set. They simplify complex information so the audience can quickly grasp the ups and downs of values. From tracking stock prices to analyzing experimental results, you can use line graphs to show how data changes over a continuous timeline. They show trends with simplicity and clarity.

Real-life Application of Line Graphs

To understand line graphs thoroughly, we will use a real case. Imagine you’re a financial analyst presenting a tech company’s monthly sales for a licensed product over the past year. Investors want insights into sales behavior by month, how market trends may have influenced sales performance and reception to the new pricing strategy. To present data via a line graph, you will complete these steps.

First, you need to gather the data. In this case, your data will be the sales numbers. For example:

- January: $45,000

- February: $55,000

- March: $45,000

- April: $60,000

- May: $ 70,000

- June: $65,000

- July: $62,000

- August: $68,000

- September: $81,000

- October: $76,000

- November: $87,000

- December: $91,000

After choosing the data, the next step is to select the orientation. Like bar charts, you can use vertical or horizontal line graphs. However, we want to keep this simple, so we will keep the timeline (x-axis) horizontal while the sales numbers (y-axis) vertical.

Step 3: Connecting Trends

After adding the data to your preferred software, you will plot a line graph. In the graph, each month’s sales are represented by data points connected by a line.

Step 4: Adding Clarity with Color

If there are multiple lines, you can also add colors to highlight each one, making it easier to follow.

Line graphs excel at visually presenting trends over time. These presentation aids identify patterns, like upward or downward trends. However, too many data points can clutter the graph, making it harder to interpret. Line graphs work best with continuous data but are not suitable for categories.

For more information, check our collection of line chart templates for PowerPoint and our article about how to make a presentation graph .

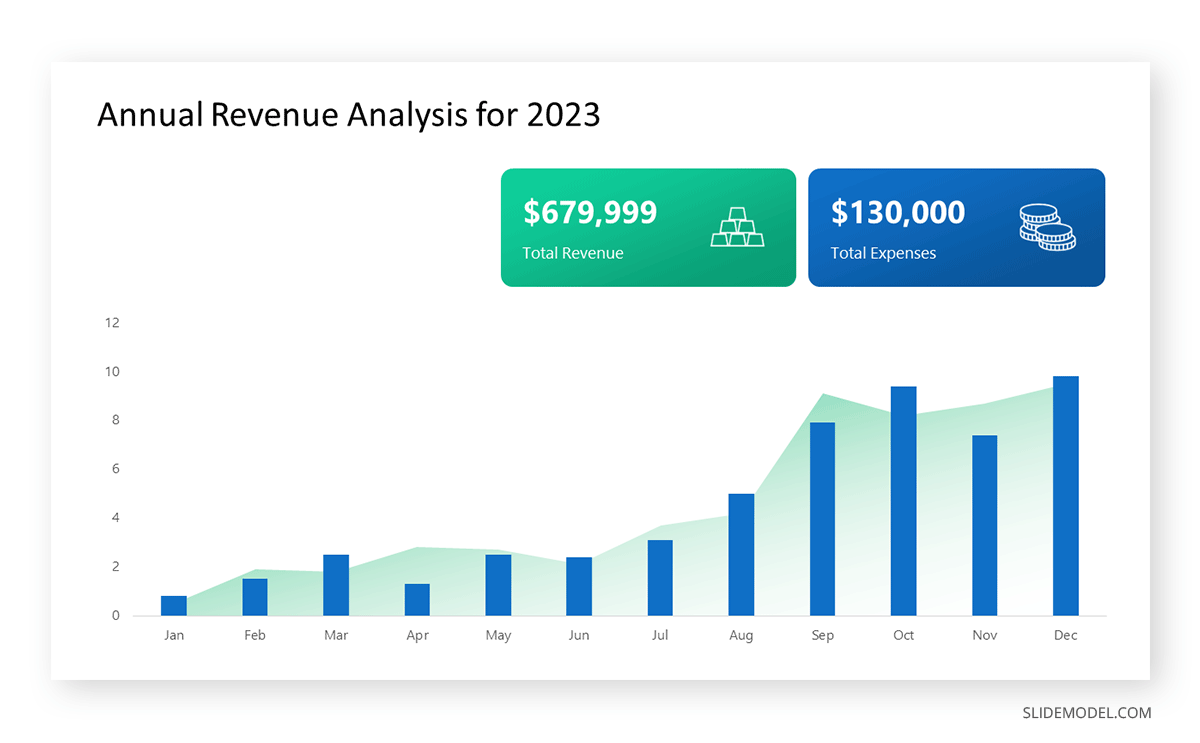

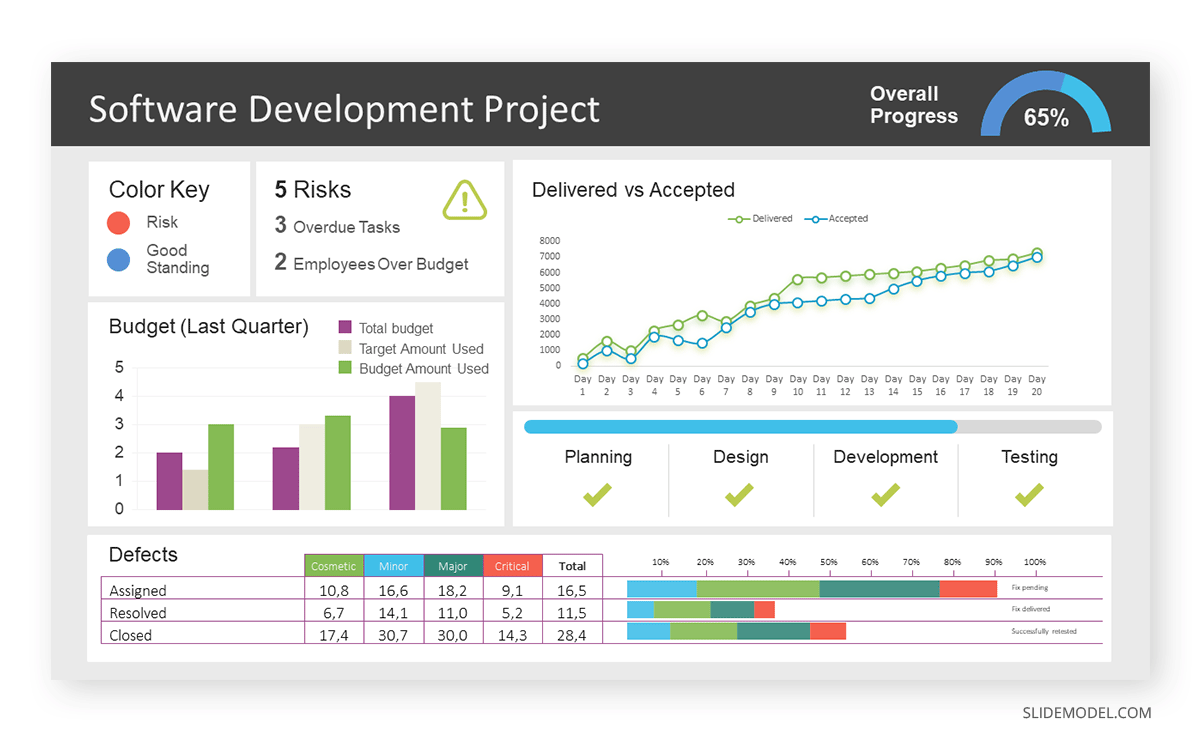

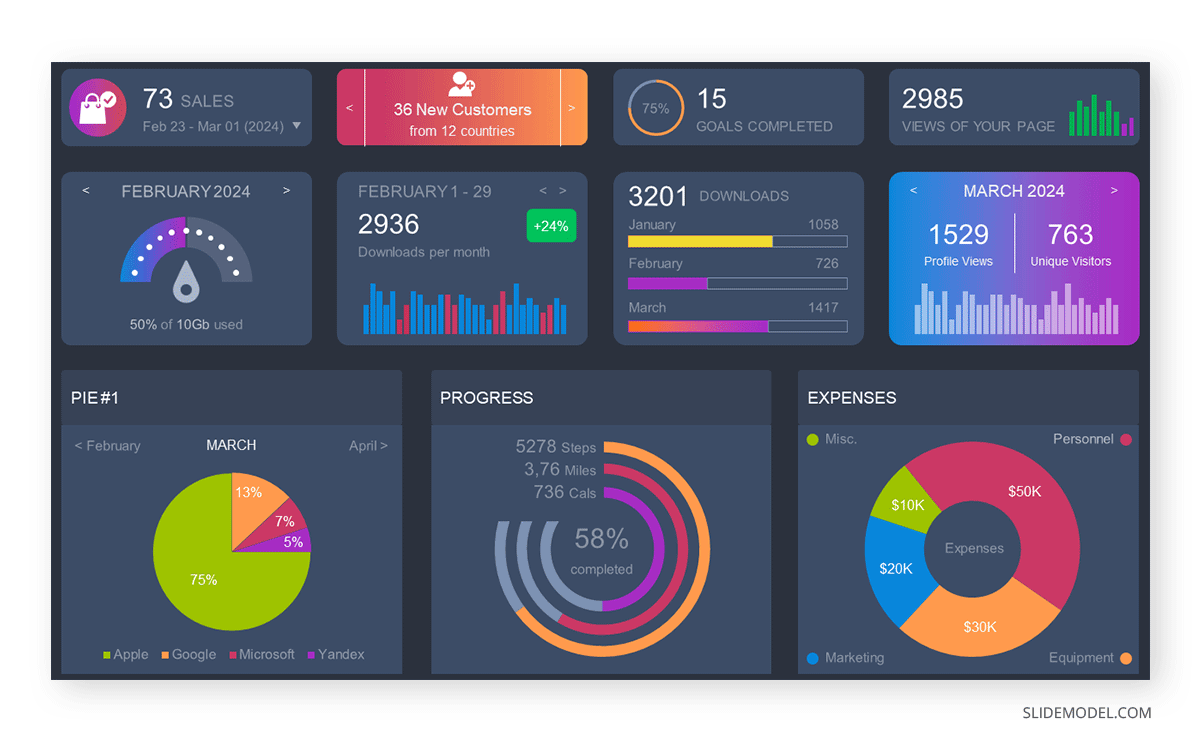

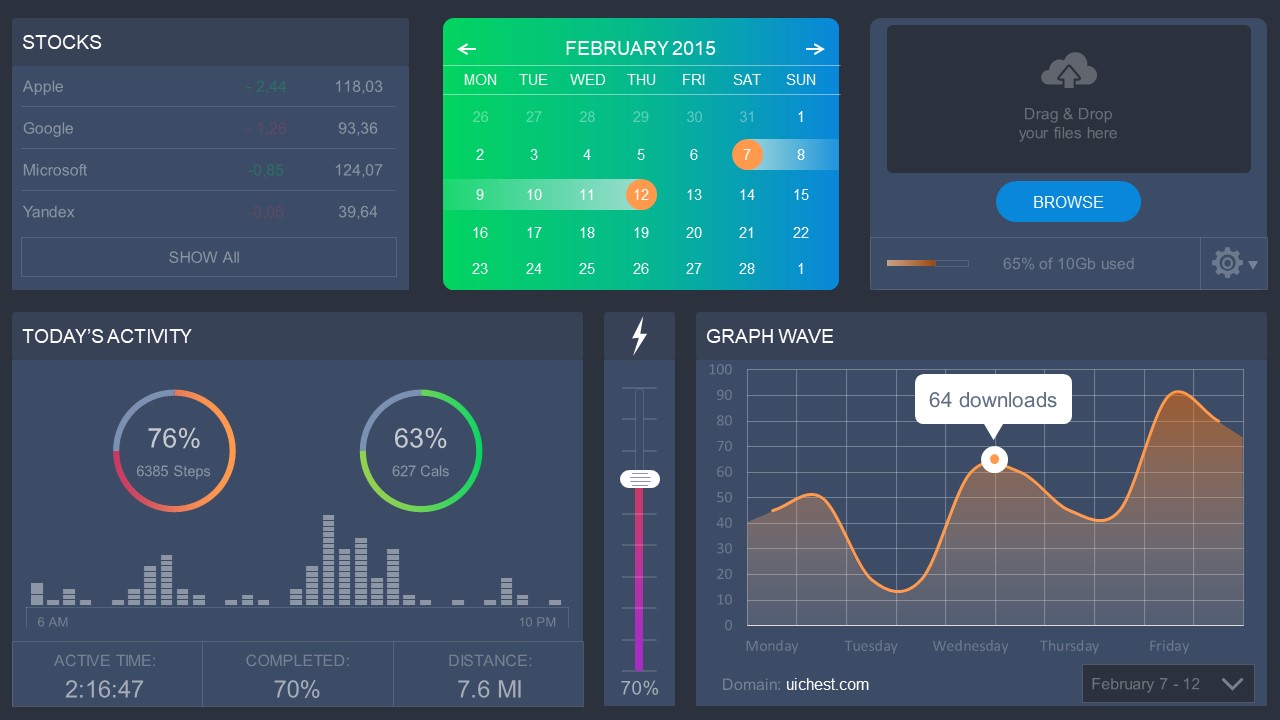

A data dashboard is a visual tool for analyzing information. Different graphs, charts, and tables are consolidated in a layout to showcase the information required to achieve one or more objectives. Dashboards help quickly see Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). You don’t make new visuals in the dashboard; instead, you use it to display visuals you’ve already made in worksheets [3] .

Keeping the number of visuals on a dashboard to three or four is recommended. Adding too many can make it hard to see the main points [4]. Dashboards can be used for business analytics to analyze sales, revenue, and marketing metrics at a time. They are also used in the manufacturing industry, as they allow users to grasp the entire production scenario at the moment while tracking the core KPIs for each line.

Real-Life Application of a Dashboard

Consider a project manager presenting a software development project’s progress to a tech company’s leadership team. He follows the following steps.

Step 1: Defining Key Metrics

To effectively communicate the project’s status, identify key metrics such as completion status, budget, and bug resolution rates. Then, choose measurable metrics aligned with project objectives.

Step 2: Choosing Visualization Widgets

After finalizing the data, presentation aids that align with each metric are selected. For this project, the project manager chooses a progress bar for the completion status and uses bar charts for budget allocation. Likewise, he implements line charts for bug resolution rates.

Step 3: Dashboard Layout

Key metrics are prominently placed in the dashboard for easy visibility, and the manager ensures that it appears clean and organized.

Dashboards provide a comprehensive view of key project metrics. Users can interact with data, customize views, and drill down for detailed analysis. However, creating an effective dashboard requires careful planning to avoid clutter. Besides, dashboards rely on the availability and accuracy of underlying data sources.

For more information, check our article on how to design a dashboard presentation , and discover our collection of dashboard PowerPoint templates .

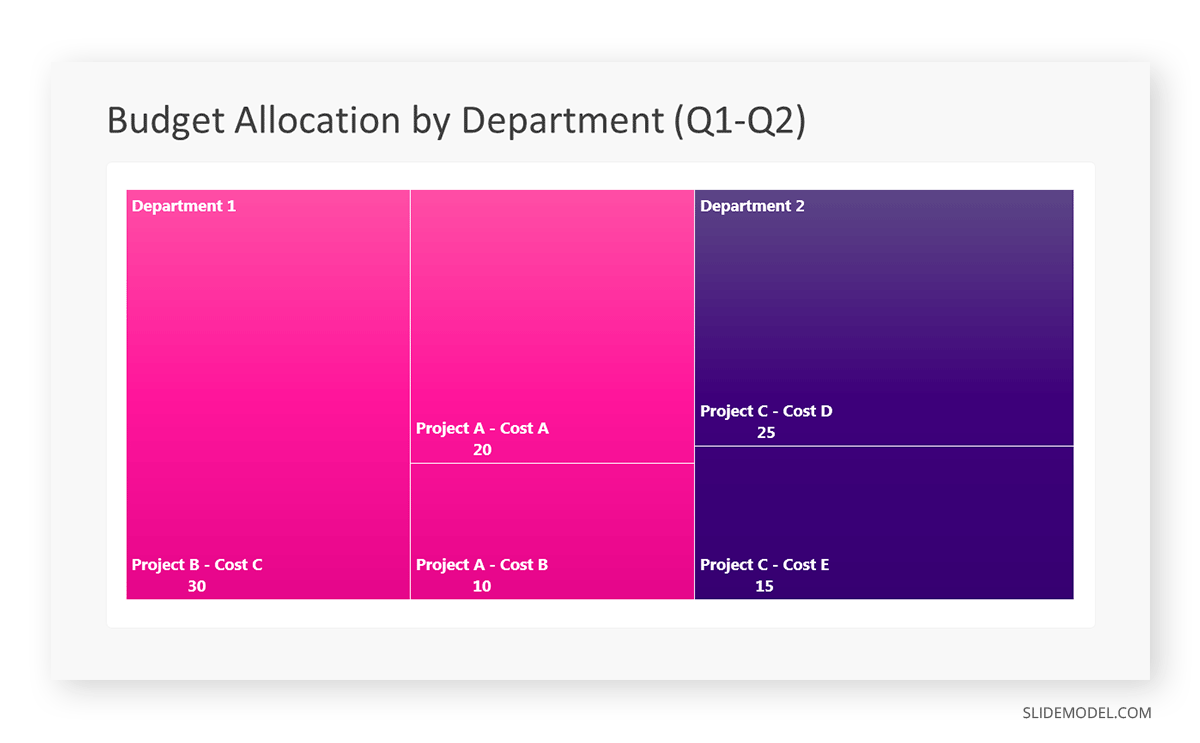

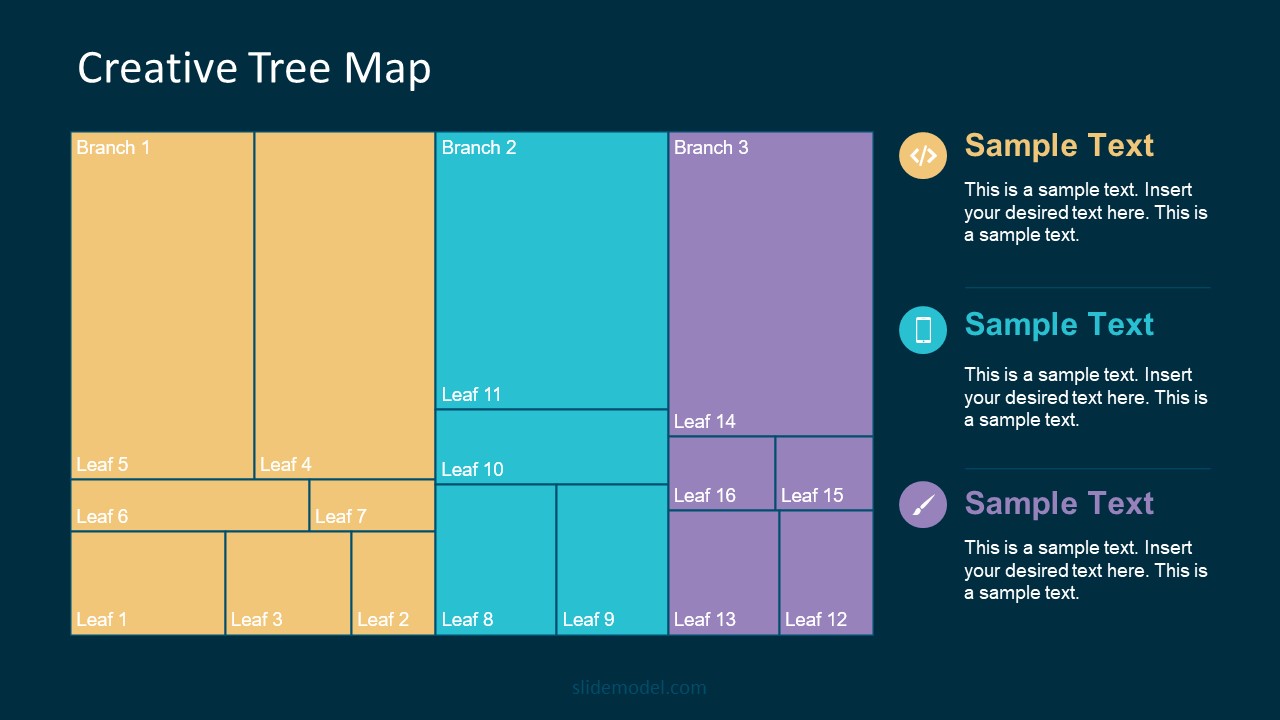

Treemap charts represent hierarchical data structured in a series of nested rectangles [6] . As each branch of the ‘tree’ is given a rectangle, smaller tiles can be seen representing sub-branches, meaning elements on a lower hierarchical level than the parent rectangle. Each one of those rectangular nodes is built by representing an area proportional to the specified data dimension.

Treemaps are useful for visualizing large datasets in compact space. It is easy to identify patterns, such as which categories are dominant. Common applications of the treemap chart are seen in the IT industry, such as resource allocation, disk space management, website analytics, etc. Also, they can be used in multiple industries like healthcare data analysis, market share across different product categories, or even in finance to visualize portfolios.

Real-Life Application of a Treemap Chart

Let’s consider a financial scenario where a financial team wants to represent the budget allocation of a company. There is a hierarchy in the process, so it is helpful to use a treemap chart. In the chart, the top-level rectangle could represent the total budget, and it would be subdivided into smaller rectangles, each denoting a specific department. Further subdivisions within these smaller rectangles might represent individual projects or cost categories.

Step 1: Define Your Data Hierarchy

While presenting data on the budget allocation, start by outlining the hierarchical structure. The sequence will be like the overall budget at the top, followed by departments, projects within each department, and finally, individual cost categories for each project.

- Top-level rectangle: Total Budget

- Second-level rectangles: Departments (Engineering, Marketing, Sales)

- Third-level rectangles: Projects within each department

- Fourth-level rectangles: Cost categories for each project (Personnel, Marketing Expenses, Equipment)

Step 2: Choose a Suitable Tool

It’s time to select a data visualization tool supporting Treemaps. Popular choices include Tableau, Microsoft Power BI, PowerPoint, or even coding with libraries like D3.js. It is vital to ensure that the chosen tool provides customization options for colors, labels, and hierarchical structures.

Here, the team uses PowerPoint for this guide because of its user-friendly interface and robust Treemap capabilities.

Step 3: Make a Treemap Chart with PowerPoint

After opening the PowerPoint presentation, they chose “SmartArt” to form the chart. The SmartArt Graphic window has a “Hierarchy” category on the left. Here, you will see multiple options. You can choose any layout that resembles a Treemap. The “Table Hierarchy” or “Organization Chart” options can be adapted. The team selects the Table Hierarchy as it looks close to a Treemap.

Step 5: Input Your Data

After that, a new window will open with a basic structure. They add the data one by one by clicking on the text boxes. They start with the top-level rectangle, representing the total budget.

Step 6: Customize the Treemap

By clicking on each shape, they customize its color, size, and label. At the same time, they can adjust the font size, style, and color of labels by using the options in the “Format” tab in PowerPoint. Using different colors for each level enhances the visual difference.

Treemaps excel at illustrating hierarchical structures. These charts make it easy to understand relationships and dependencies. They efficiently use space, compactly displaying a large amount of data, reducing the need for excessive scrolling or navigation. Additionally, using colors enhances the understanding of data by representing different variables or categories.

In some cases, treemaps might become complex, especially with deep hierarchies. It becomes challenging for some users to interpret the chart. At the same time, displaying detailed information within each rectangle might be constrained by space. It potentially limits the amount of data that can be shown clearly. Without proper labeling and color coding, there’s a risk of misinterpretation.

A heatmap is a data visualization tool that uses color coding to represent values across a two-dimensional surface. In these, colors replace numbers to indicate the magnitude of each cell. This color-shaded matrix display is valuable for summarizing and understanding data sets with a glance [7] . The intensity of the color corresponds to the value it represents, making it easy to identify patterns, trends, and variations in the data.

As a tool, heatmaps help businesses analyze website interactions, revealing user behavior patterns and preferences to enhance overall user experience. In addition, companies use heatmaps to assess content engagement, identifying popular sections and areas of improvement for more effective communication. They excel at highlighting patterns and trends in large datasets, making it easy to identify areas of interest.

We can implement heatmaps to express multiple data types, such as numerical values, percentages, or even categorical data. Heatmaps help us easily spot areas with lots of activity, making them helpful in figuring out clusters [8] . When making these maps, it is important to pick colors carefully. The colors need to show the differences between groups or levels of something. And it is good to use colors that people with colorblindness can easily see.

Check our detailed guide on how to create a heatmap here. Also discover our collection of heatmap PowerPoint templates .

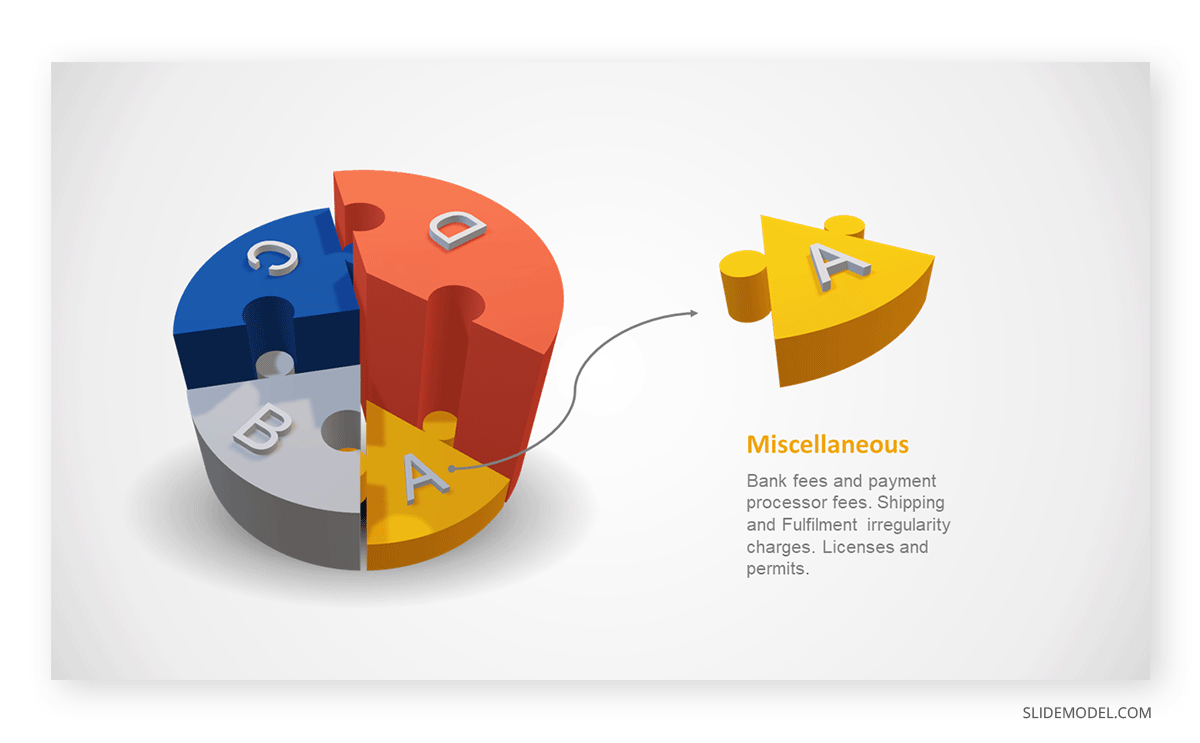

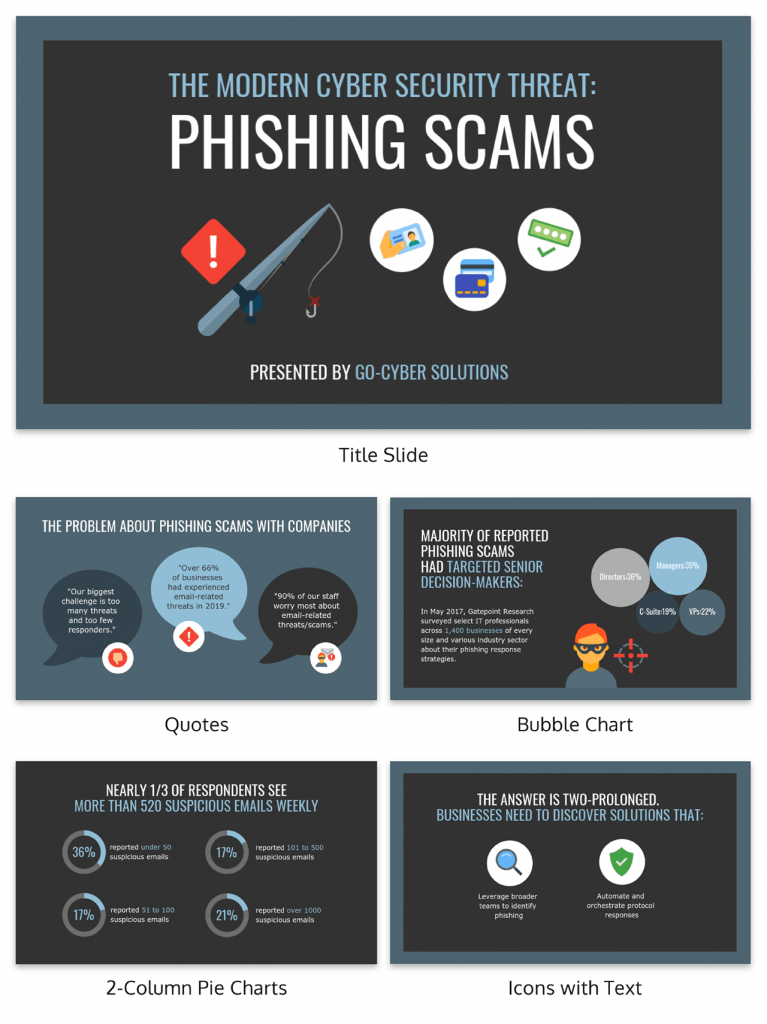

Pie charts are circular statistical graphics divided into slices to illustrate numerical proportions. Each slice represents a proportionate part of the whole, making it easy to visualize the contribution of each component to the total.

The size of the pie charts is influenced by the value of data points within each pie. The total of all data points in a pie determines its size. The pie with the highest data points appears as the largest, whereas the others are proportionally smaller. However, you can present all pies of the same size if proportional representation is not required [9] . Sometimes, pie charts are difficult to read, or additional information is required. A variation of this tool can be used instead, known as the donut chart , which has the same structure but a blank center, creating a ring shape. Presenters can add extra information, and the ring shape helps to declutter the graph.

Pie charts are used in business to show percentage distribution, compare relative sizes of categories, or present straightforward data sets where visualizing ratios is essential.

Real-Life Application of Pie Charts

Consider a scenario where you want to represent the distribution of the data. Each slice of the pie chart would represent a different category, and the size of each slice would indicate the percentage of the total portion allocated to that category.

Step 1: Define Your Data Structure

Imagine you are presenting the distribution of a project budget among different expense categories.

- Column A: Expense Categories (Personnel, Equipment, Marketing, Miscellaneous)

- Column B: Budget Amounts ($40,000, $30,000, $20,000, $10,000) Column B represents the values of your categories in Column A.

Step 2: Insert a Pie Chart

Using any of the accessible tools, you can create a pie chart. The most convenient tools for forming a pie chart in a presentation are presentation tools such as PowerPoint or Google Slides. You will notice that the pie chart assigns each expense category a percentage of the total budget by dividing it by the total budget.

For instance:

- Personnel: $40,000 / ($40,000 + $30,000 + $20,000 + $10,000) = 40%

- Equipment: $30,000 / ($40,000 + $30,000 + $20,000 + $10,000) = 30%

- Marketing: $20,000 / ($40,000 + $30,000 + $20,000 + $10,000) = 20%

- Miscellaneous: $10,000 / ($40,000 + $30,000 + $20,000 + $10,000) = 10%

You can make a chart out of this or just pull out the pie chart from the data.

3D pie charts and 3D donut charts are quite popular among the audience. They stand out as visual elements in any presentation slide, so let’s take a look at how our pie chart example would look in 3D pie chart format.

Step 03: Results Interpretation

The pie chart visually illustrates the distribution of the project budget among different expense categories. Personnel constitutes the largest portion at 40%, followed by equipment at 30%, marketing at 20%, and miscellaneous at 10%. This breakdown provides a clear overview of where the project funds are allocated, which helps in informed decision-making and resource management. It is evident that personnel are a significant investment, emphasizing their importance in the overall project budget.

Pie charts provide a straightforward way to represent proportions and percentages. They are easy to understand, even for individuals with limited data analysis experience. These charts work well for small datasets with a limited number of categories.

However, a pie chart can become cluttered and less effective in situations with many categories. Accurate interpretation may be challenging, especially when dealing with slight differences in slice sizes. In addition, these charts are static and do not effectively convey trends over time.

For more information, check our collection of pie chart templates for PowerPoint .

Histograms present the distribution of numerical variables. Unlike a bar chart that records each unique response separately, histograms organize numeric responses into bins and show the frequency of reactions within each bin [10] . The x-axis of a histogram shows the range of values for a numeric variable. At the same time, the y-axis indicates the relative frequencies (percentage of the total counts) for that range of values.

Whenever you want to understand the distribution of your data, check which values are more common, or identify outliers, histograms are your go-to. Think of them as a spotlight on the story your data is telling. A histogram can provide a quick and insightful overview if you’re curious about exam scores, sales figures, or any numerical data distribution.

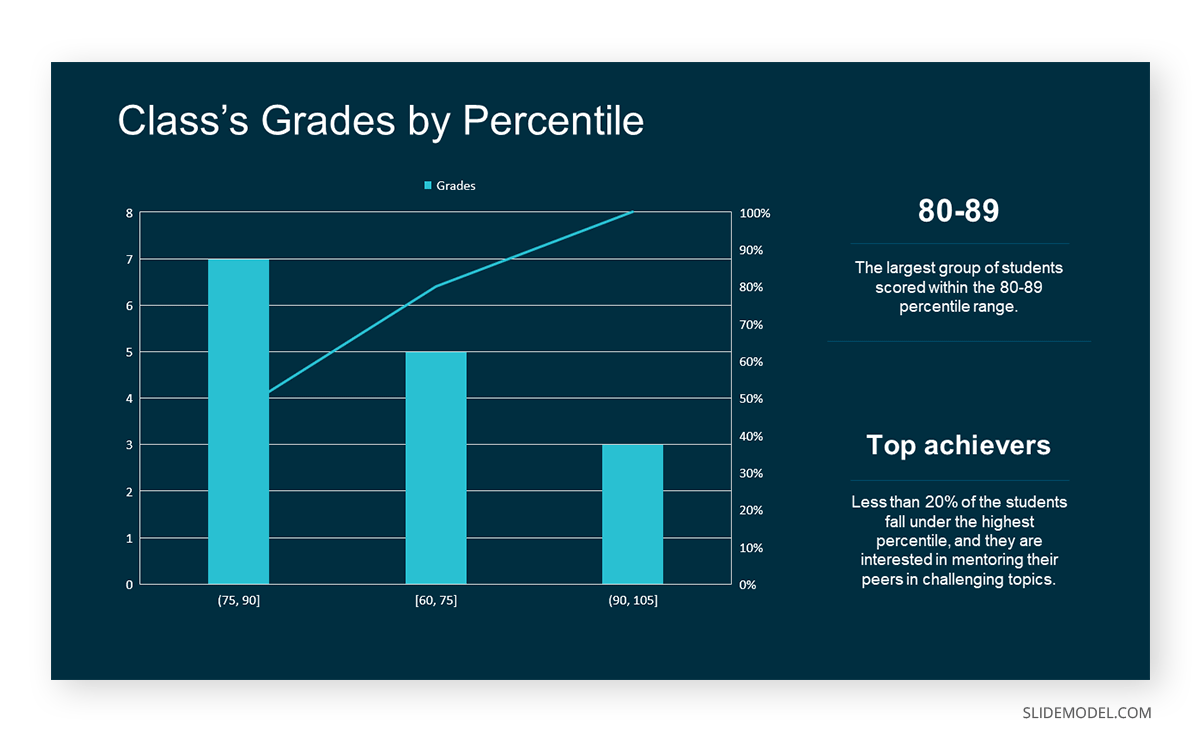

Real-Life Application of a Histogram

In the histogram data analysis presentation example, imagine an instructor analyzing a class’s grades to identify the most common score range. A histogram could effectively display the distribution. It will show whether most students scored in the average range or if there are significant outliers.

Step 1: Gather Data

He begins by gathering the data. The scores of each student in class are gathered to analyze exam scores.

After arranging the scores in ascending order, bin ranges are set.

Step 2: Define Bins

Bins are like categories that group similar values. Think of them as buckets that organize your data. The presenter decides how wide each bin should be based on the range of the values. For instance, the instructor sets the bin ranges based on score intervals: 60-69, 70-79, 80-89, and 90-100.

Step 3: Count Frequency

Now, he counts how many data points fall into each bin. This step is crucial because it tells you how often specific ranges of values occur. The result is the frequency distribution, showing the occurrences of each group.

Here, the instructor counts the number of students in each category.

- 60-69: 1 student (Kate)

- 70-79: 4 students (David, Emma, Grace, Jack)

- 80-89: 7 students (Alice, Bob, Frank, Isabel, Liam, Mia, Noah)

- 90-100: 3 students (Clara, Henry, Olivia)

Step 4: Create the Histogram

It’s time to turn the data into a visual representation. Draw a bar for each bin on a graph. The width of the bar should correspond to the range of the bin, and the height should correspond to the frequency. To make your histogram understandable, label the X and Y axes.

In this case, the X-axis should represent the bins (e.g., test score ranges), and the Y-axis represents the frequency.

The histogram of the class grades reveals insightful patterns in the distribution. Most students, with seven students, fall within the 80-89 score range. The histogram provides a clear visualization of the class’s performance. It showcases a concentration of grades in the upper-middle range with few outliers at both ends. This analysis helps in understanding the overall academic standing of the class. It also identifies the areas for potential improvement or recognition.

Thus, histograms provide a clear visual representation of data distribution. They are easy to interpret, even for those without a statistical background. They apply to various types of data, including continuous and discrete variables. One weak point is that histograms do not capture detailed patterns in students’ data, with seven compared to other visualization methods.

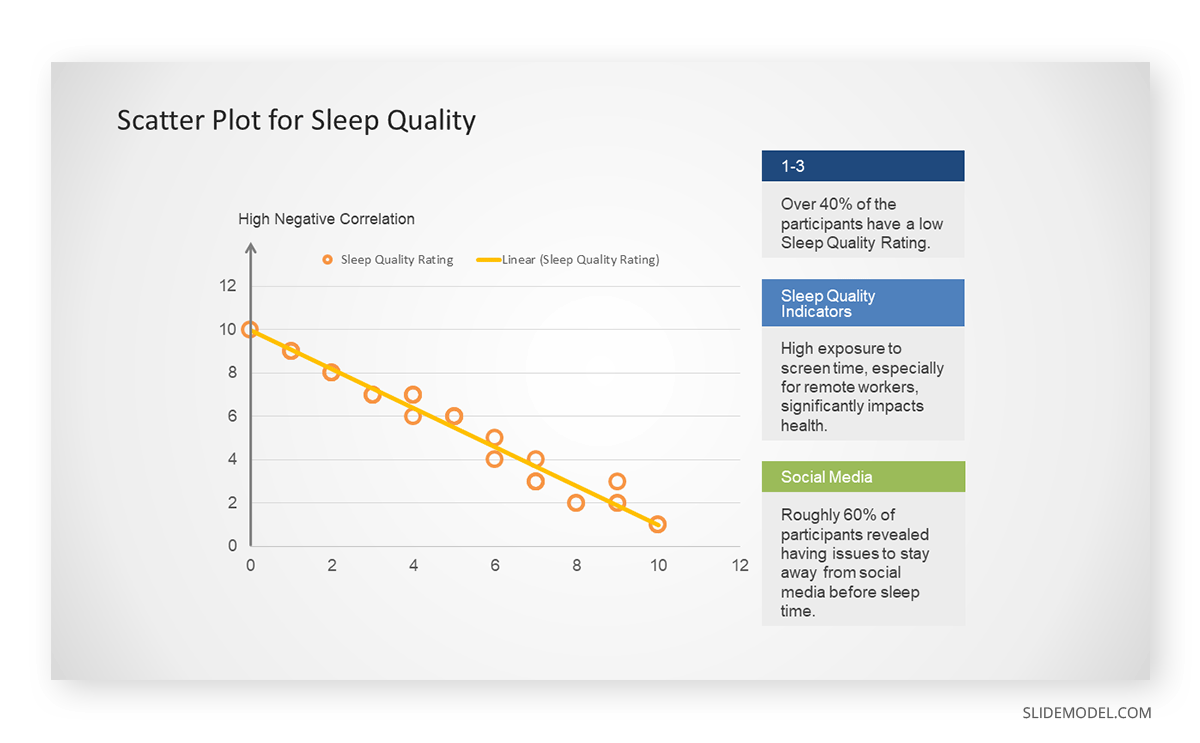

A scatter plot is a graphical representation of the relationship between two variables. It consists of individual data points on a two-dimensional plane. This plane plots one variable on the x-axis and the other on the y-axis. Each point represents a unique observation. It visualizes patterns, trends, or correlations between the two variables.

Scatter plots are also effective in revealing the strength and direction of relationships. They identify outliers and assess the overall distribution of data points. The points’ dispersion and clustering reflect the relationship’s nature, whether it is positive, negative, or lacks a discernible pattern. In business, scatter plots assess relationships between variables such as marketing cost and sales revenue. They help present data correlations and decision-making.

Real-Life Application of Scatter Plot

A group of scientists is conducting a study on the relationship between daily hours of screen time and sleep quality. After reviewing the data, they managed to create this table to help them build a scatter plot graph:

In the provided example, the x-axis represents Daily Hours of Screen Time, and the y-axis represents the Sleep Quality Rating.

The scientists observe a negative correlation between the amount of screen time and the quality of sleep. This is consistent with their hypothesis that blue light, especially before bedtime, has a significant impact on sleep quality and metabolic processes.

There are a few things to remember when using a scatter plot. Even when a scatter diagram indicates a relationship, it doesn’t mean one variable affects the other. A third factor can influence both variables. The more the plot resembles a straight line, the stronger the relationship is perceived [11] . If it suggests no ties, the observed pattern might be due to random fluctuations in data. When the scatter diagram depicts no correlation, whether the data might be stratified is worth considering.

Choosing the appropriate data presentation type is crucial when making a presentation . Understanding the nature of your data and the message you intend to convey will guide this selection process. For instance, when showcasing quantitative relationships, scatter plots become instrumental in revealing correlations between variables. If the focus is on emphasizing parts of a whole, pie charts offer a concise display of proportions. Histograms, on the other hand, prove valuable for illustrating distributions and frequency patterns.

Bar charts provide a clear visual comparison of different categories. Likewise, line charts excel in showcasing trends over time, while tables are ideal for detailed data examination. Starting a presentation on data presentation types involves evaluating the specific information you want to communicate and selecting the format that aligns with your message. This ensures clarity and resonance with your audience from the beginning of your presentation.

1. Fact Sheet Dashboard for Data Presentation

Convey all the data you need to present in this one-pager format, an ideal solution tailored for users looking for presentation aids. Global maps, donut chats, column graphs, and text neatly arranged in a clean layout presented in light and dark themes.

Use This Template

2. 3D Column Chart Infographic PPT Template

Represent column charts in a highly visual 3D format with this PPT template. A creative way to present data, this template is entirely editable, and we can craft either a one-page infographic or a series of slides explaining what we intend to disclose point by point.

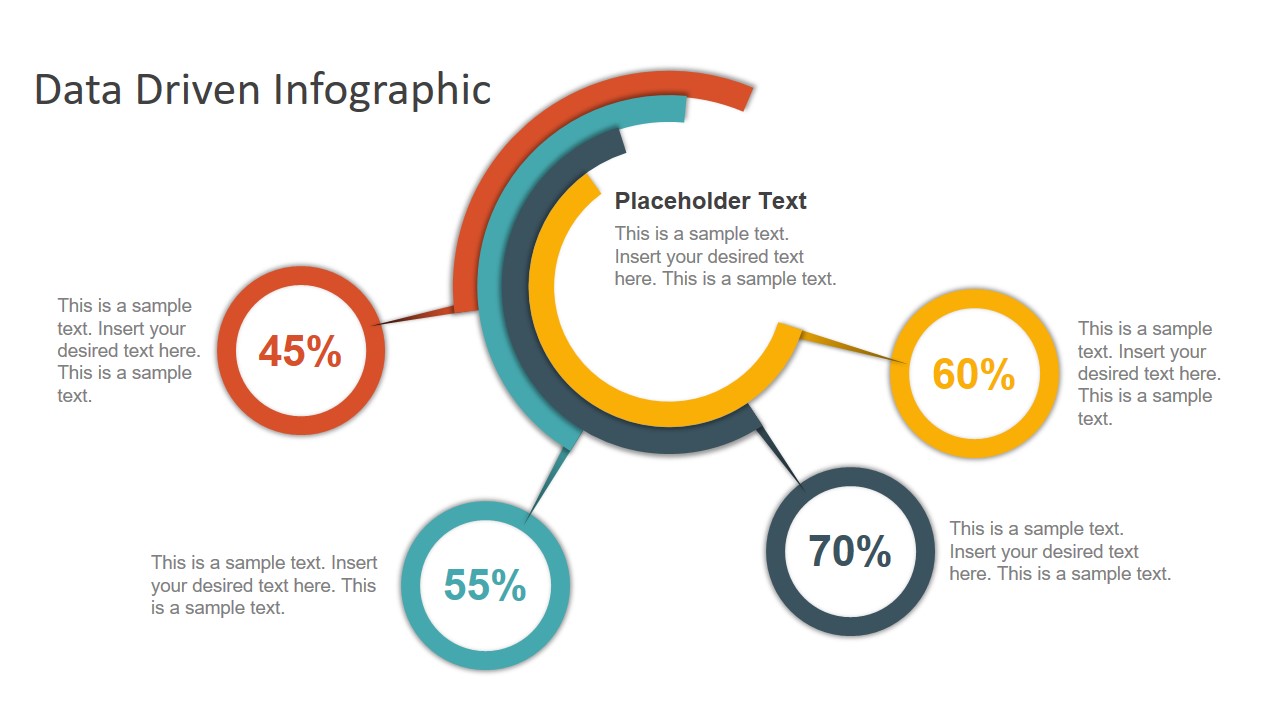

3. Data Circles Infographic PowerPoint Template

An alternative to the pie chart and donut chart diagrams, this template features a series of curved shapes with bubble callouts as ways of presenting data. Expand the information for each arch in the text placeholder areas.

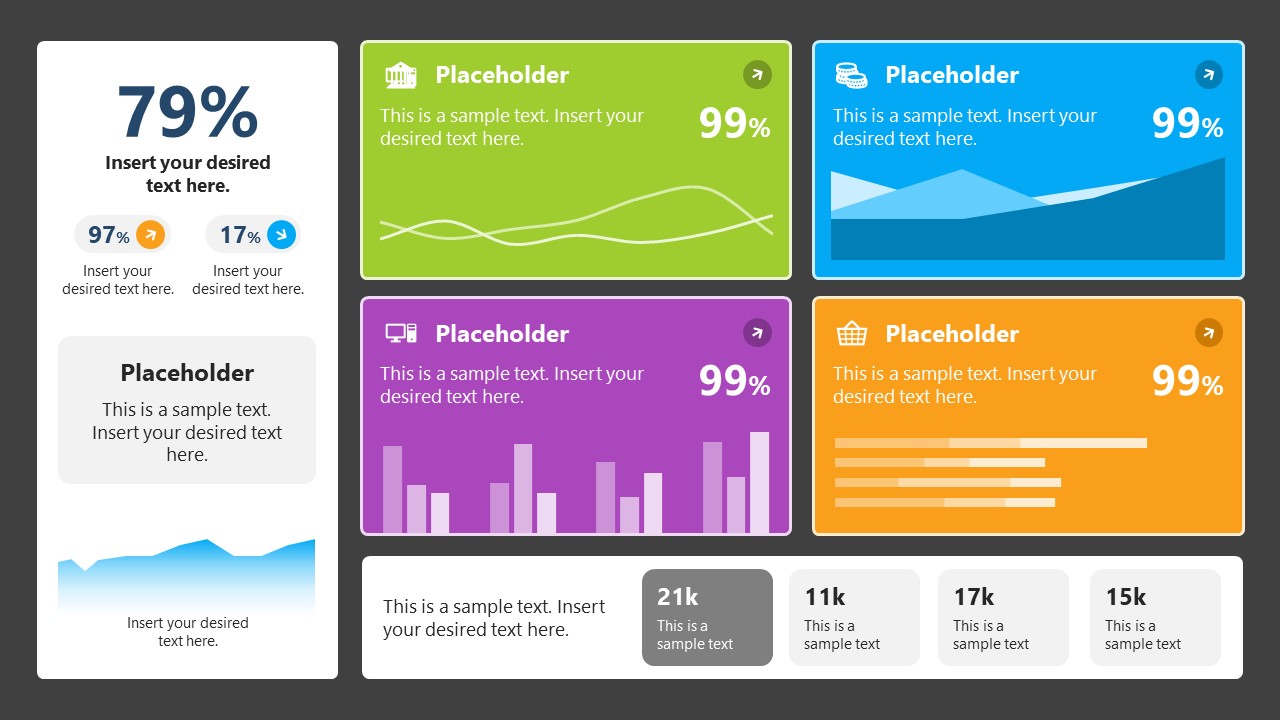

4. Colorful Metrics Dashboard for Data Presentation

This versatile dashboard template helps us in the presentation of the data by offering several graphs and methods to convert numbers into graphics. Implement it for e-commerce projects, financial projections, project development, and more.

5. Animated Data Presentation Tools for PowerPoint & Google Slides

A slide deck filled with most of the tools mentioned in this article, from bar charts, column charts, treemap graphs, pie charts, histogram, etc. Animated effects make each slide look dynamic when sharing data with stakeholders.

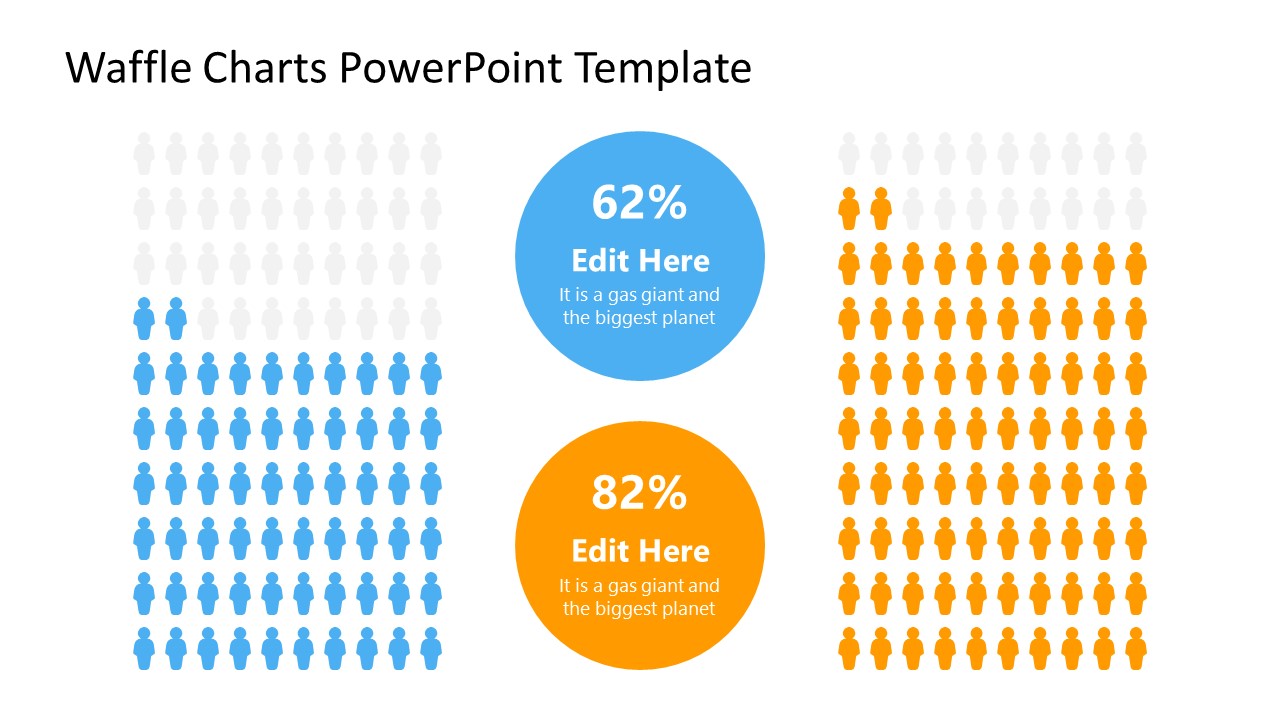

6. Statistics Waffle Charts PPT Template for Data Presentations

This PPT template helps us how to present data beyond the typical pie chart representation. It is widely used for demographics, so it’s a great fit for marketing teams, data science professionals, HR personnel, and more.

7. Data Presentation Dashboard Template for Google Slides

A compendium of tools in dashboard format featuring line graphs, bar charts, column charts, and neatly arranged placeholder text areas.

8. Weather Dashboard for Data Presentation

Share weather data for agricultural presentation topics, environmental studies, or any kind of presentation that requires a highly visual layout for weather forecasting on a single day. Two color themes are available.

9. Social Media Marketing Dashboard Data Presentation Template

Intended for marketing professionals, this dashboard template for data presentation is a tool for presenting data analytics from social media channels. Two slide layouts featuring line graphs and column charts.

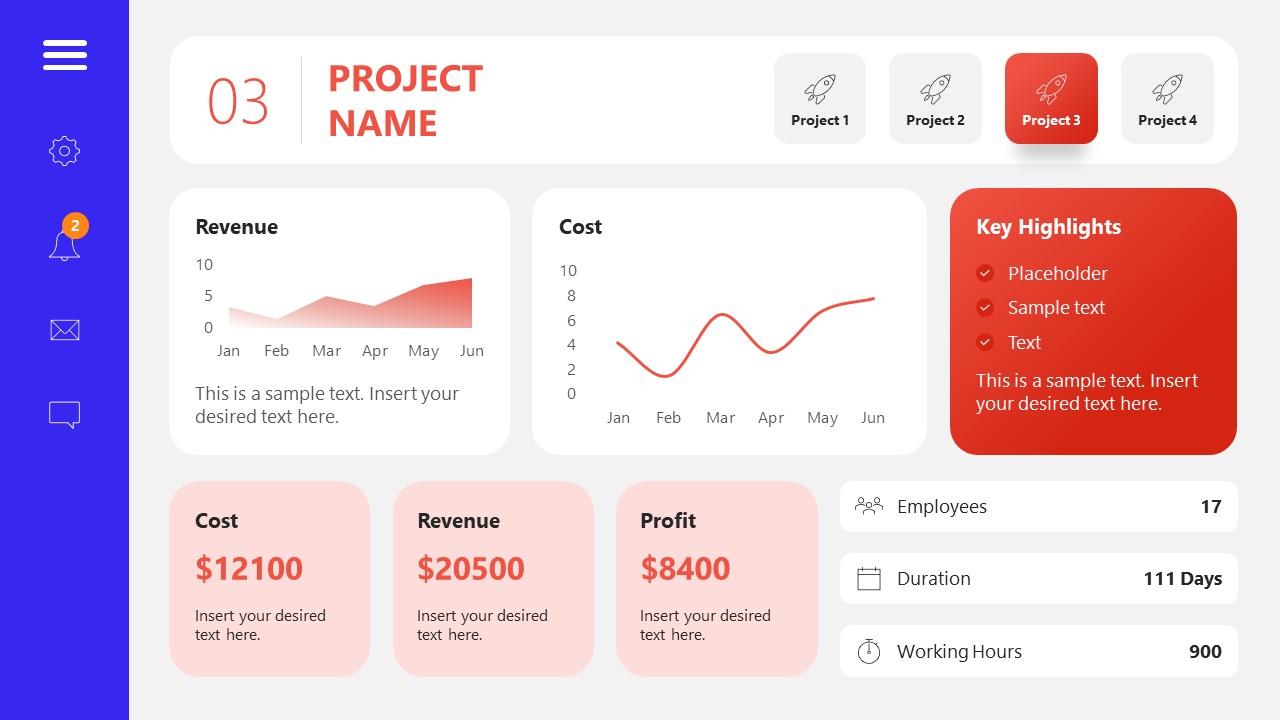

10. Project Management Summary Dashboard Template

A tool crafted for project managers to deliver highly visual reports on a project’s completion, the profits it delivered for the company, and expenses/time required to execute it. 4 different color layouts are available.

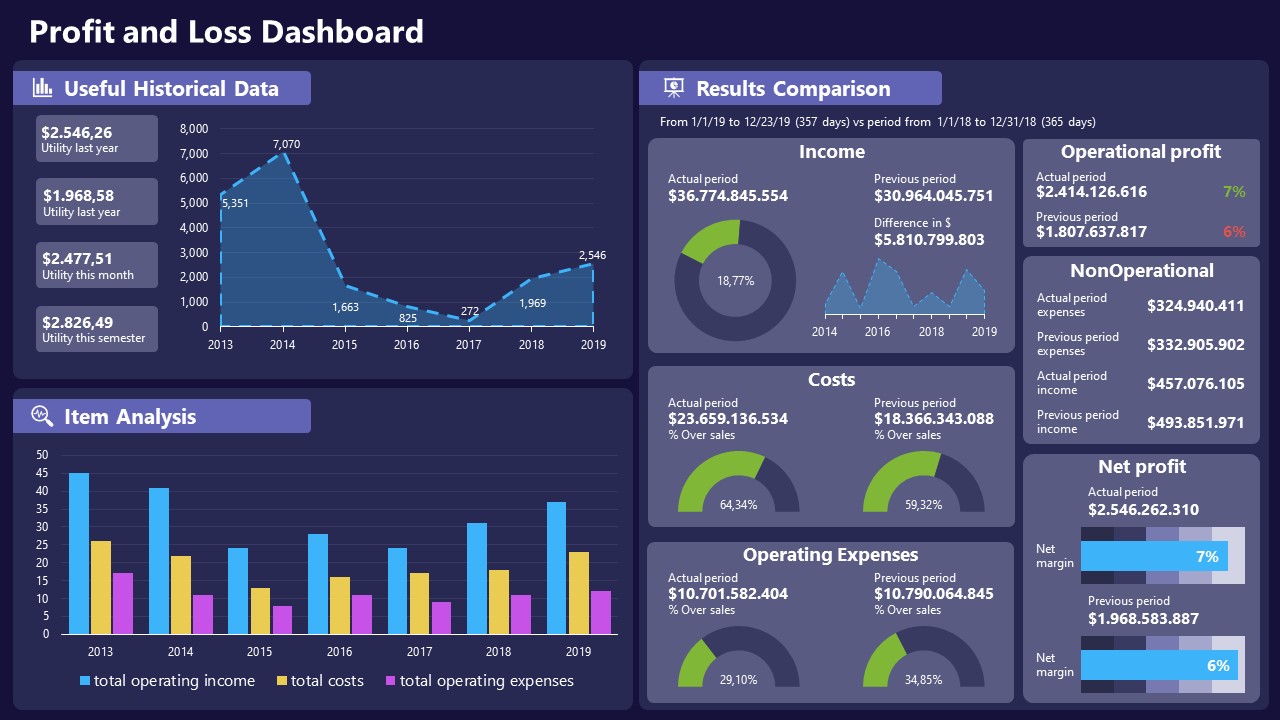

11. Profit & Loss Dashboard for PowerPoint and Google Slides

A must-have for finance professionals. This typical profit & loss dashboard includes progress bars, donut charts, column charts, line graphs, and everything that’s required to deliver a comprehensive report about a company’s financial situation.

Overwhelming visuals

One of the mistakes related to using data-presenting methods is including too much data or using overly complex visualizations. They can confuse the audience and dilute the key message.

Inappropriate chart types

Choosing the wrong type of chart for the data at hand can lead to misinterpretation. For example, using a pie chart for data that doesn’t represent parts of a whole is not right.

Lack of context

Failing to provide context or sufficient labeling can make it challenging for the audience to understand the significance of the presented data.

Inconsistency in design

Using inconsistent design elements and color schemes across different visualizations can create confusion and visual disarray.

Failure to provide details

Simply presenting raw data without offering clear insights or takeaways can leave the audience without a meaningful conclusion.

Lack of focus

Not having a clear focus on the key message or main takeaway can result in a presentation that lacks a central theme.

Visual accessibility issues

Overlooking the visual accessibility of charts and graphs can exclude certain audience members who may have difficulty interpreting visual information.

In order to avoid these mistakes in data presentation, presenters can benefit from using presentation templates . These templates provide a structured framework. They ensure consistency, clarity, and an aesthetically pleasing design, enhancing data communication’s overall impact.

Understanding and choosing data presentation types are pivotal in effective communication. Each method serves a unique purpose, so selecting the appropriate one depends on the nature of the data and the message to be conveyed. The diverse array of presentation types offers versatility in visually representing information, from bar charts showing values to pie charts illustrating proportions.

Using the proper method enhances clarity, engages the audience, and ensures that data sets are not just presented but comprehensively understood. By appreciating the strengths and limitations of different presentation types, communicators can tailor their approach to convey information accurately, developing a deeper connection between data and audience understanding.

[1] Government of Canada, S.C. (2021) 5 Data Visualization 5.2 Bar Chart , 5.2 Bar chart . https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/edu/power-pouvoir/ch9/bargraph-diagrammeabarres/5214818-eng.htm

[2] Kosslyn, S.M., 1989. Understanding charts and graphs. Applied cognitive psychology, 3(3), pp.185-225. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA183409.pdf

[3] Creating a Dashboard . https://it.tufts.edu/book/export/html/1870

[4] https://www.goldenwestcollege.edu/research/data-and-more/data-dashboards/index.html

[5] https://www.mit.edu/course/21/21.guide/grf-line.htm

[6] Jadeja, M. and Shah, K., 2015, January. Tree-Map: A Visualization Tool for Large Data. In GSB@ SIGIR (pp. 9-13). https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-1393/gsb15proceedings.pdf#page=15

[7] Heat Maps and Quilt Plots. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/population-health-methods/heat-maps-and-quilt-plots

[8] EIU QGIS WORKSHOP. https://www.eiu.edu/qgisworkshop/heatmaps.php

[9] About Pie Charts. https://www.mit.edu/~mbarker/formula1/f1help/11-ch-c8.htm

[10] Histograms. https://sites.utexas.edu/sos/guided/descriptive/numericaldd/descriptiven2/histogram/ [11] https://asq.org/quality-resources/scatter-diagram

Like this article? Please share

Data Analysis, Data Science, Data Visualization Filed under Design

Related Articles

Filed under Design • March 27th, 2024

How to Make a Presentation Graph

Detailed step-by-step instructions to master the art of how to make a presentation graph in PowerPoint and Google Slides. Check it out!

Filed under Presentation Ideas • January 6th, 2024

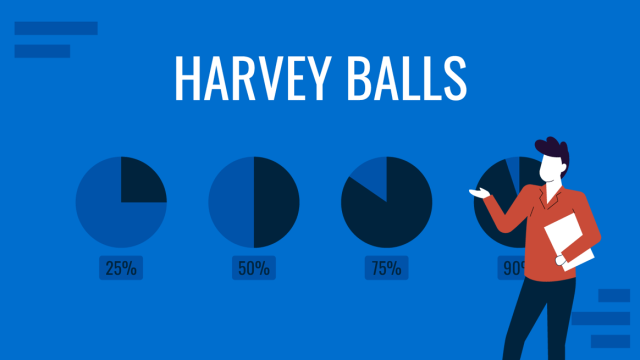

All About Using Harvey Balls

Among the many tools in the arsenal of the modern presenter, Harvey Balls have a special place. In this article we will tell you all about using Harvey Balls.

Filed under Business • December 8th, 2023

How to Design a Dashboard Presentation: A Step-by-Step Guide

Take a step further in your professional presentation skills by learning what a dashboard presentation is and how to properly design one in PowerPoint. A detailed step-by-step guide is here!

Leave a Reply

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Present Your Data Like a Pro

- Joel Schwartzberg

Demystify the numbers. Your audience will thank you.

While a good presentation has data, data alone doesn’t guarantee a good presentation. It’s all about how that data is presented. The quickest way to confuse your audience is by sharing too many details at once. The only data points you should share are those that significantly support your point — and ideally, one point per chart. To avoid the debacle of sheepishly translating hard-to-see numbers and labels, rehearse your presentation with colleagues sitting as far away as the actual audience would. While you’ve been working with the same chart for weeks or months, your audience will be exposed to it for mere seconds. Give them the best chance of comprehending your data by using simple, clear, and complete language to identify X and Y axes, pie pieces, bars, and other diagrammatic elements. Try to avoid abbreviations that aren’t obvious, and don’t assume labeled components on one slide will be remembered on subsequent slides. Every valuable chart or pie graph has an “Aha!” zone — a number or range of data that reveals something crucial to your point. Make sure you visually highlight the “Aha!” zone, reinforcing the moment by explaining it to your audience.

With so many ways to spin and distort information these days, a presentation needs to do more than simply share great ideas — it needs to support those ideas with credible data. That’s true whether you’re an executive pitching new business clients, a vendor selling her services, or a CEO making a case for change.

- JS Joel Schwartzberg oversees executive communications for a major national nonprofit, is a professional presentation coach, and is the author of Get to the Point! Sharpen Your Message and Make Your Words Matter and The Language of Leadership: How to Engage and Inspire Your Team . You can find him on LinkedIn and X. TheJoelTruth

Partner Center

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.3: Presentation of Data

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 577

Learning Objectives

- To learn two ways that data will be presented in the text.

In this book we will use two formats for presenting data sets. The first is a data list, which is an explicit listing of all the individual measurements, either as a display with space between the individual measurements, or in set notation with individual measurements separated by commas.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

The data obtained by measuring the age of \(21\) randomly selected students enrolled in freshman courses at a university could be presented as the data list:

\[\begin{array}{cccccccccc}18 & 18 & 19 & 19 & 19 & 18 & 22 & 20 & 18 & 18 & 17 \\ 19 & 18 & 24 & 18 & 20 & 18 & 21 & 20 & 17 & 19 &\end{array} \nonumber \]

or in set notation as:

\[ \{18,18,19,19,19,18,22,20,18,18,17,19,18,24,18,20,18,21,20,17,19\} \nonumber \]

A data set can also be presented by means of a data frequency table, a table in which each distinct value \(x\) is listed in the first row and its frequency \(f\), which is the number of times the value \(x\) appears in the data set, is listed below it in the second row.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

The data set of the previous example is represented by the data frequency table

\[\begin{array}{c|cccccc}x & 17 & 18 & 19 & 20 & 21 & 22 & 24 \\ \hline f & 2 & 8 & 5 & 3 & 1 & 1 & 1\end{array} \nonumber \]

The data frequency table is especially convenient when data sets are large and the number of distinct values is not too large.

Key Takeaway

- Data sets can be presented either by listing all the elements or by giving a table of values and frequencies.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

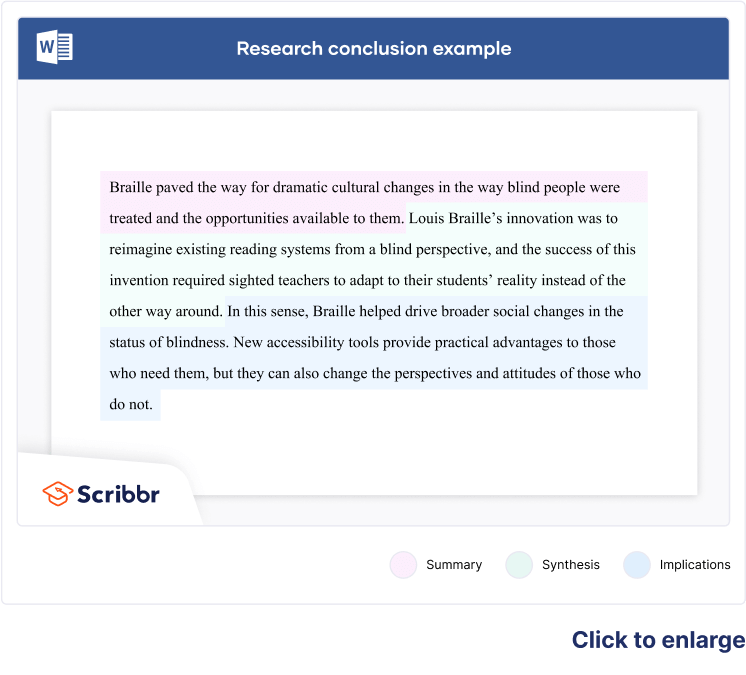

74 Drawing Conclusions From Your Data

As we mentioned earlier, it is important to not just state the results of your statistical analyses. You should interpret the meanings, because this will enable you to answer your research questions. At the end of your analysis, you should be able to conclude whether your hypotheses are confirmed or rejected. To ensure you are able to draw conclusions from your analyses, we offer the following suggestions:

- Highlight key findings from the data.

- Making generalized comparisons

- Assess the right strength of the claim. Are hypotheses supported? To what extent? To what extent do generalizations hold?

- Examine the goodness of fit.

Your conclusions could be framed in statements such as:

“Most respondents …..”

“Group A (e.g., Young adults) were more likely to ___than group B (older adults)

“Given the low degree of fit, other variables/factors might explain the relationship discovered”

Box 10.10 – Statistical Analysis Checklist

Access and Organize the Dataset

- I have checked whether an Institutional Ethics Review is needed. If it is needed, I have obtained it.

- I have recorded all the ways that I manipulated the data

- I have inspected the data set and have noted the limitations (e.g., sampling, non-response, measurement, coverage) and have inspected it for reliability and validity.

- I have inspected the data to ensure that it meets the requirements and assumptions of the statistical techniques that I wish to perform

Cleaning, Coding, and Recoding

- I have re-coded variables as appropriate.

- I have cleaned and processed the data set to make sure it is ready for analysis.

Research Design

- If it is secondary data I am using, my methodology has documented their method for deriving the data.

- My methodology documented the procedures for the quantitative data analysis.

- I have highlighted my research questions and how my findings relate to them

Statistical Analysis

- I have reported on the goodness of fit measures such as r2 and chi-square for the likelihood ratio test in order to show that your model fits the data well.

- I have not interpreted coefficients for models that do not fit the data.

- I have not merely provided statistical results, I have also interpreted the results.

- You must test relationships. Univariate statistics are not enough for quantitative research. Make some inferences supported by tests of significance. Correlations, Chi-square, ANOVAs, Regressions (Linear and Logistics) etc.

- I have stored all my statistical results in a central file which I can use to write up my results.

Statistical Presentation

- My tables and figures conform to the referencing styles that I am using.

- Report both statistically significant and non-statistically significant results. Do not be tempted to ignore the non-statistically significant results. They also tell a story.

- I have avoided generalizations that my statistics cannot make.

- I have discussed all of the relevant demographics

Practicing and Presenting Social Research Copyright © 2022 by Oral Robinson and Alexander Wilson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

30 Examples: How to Conclude a Presentation (Effective Closing Techniques)

By Status.net Editorial Team on March 4, 2024 — 9 minutes to read

Ending a presentation on a high note is a skill that can set you apart from the rest. It’s the final chance to leave an impact on your audience, ensuring they walk away with the key messages embedded in their minds. This moment is about driving your points home and making sure they resonate. Crafting a memorable closing isn’t just about summarizing key points, though that’s part of it, but also about providing value that sticks with your listeners long after they’ve left the room.

Crafting Your Core Message

To leave a lasting impression, your presentation’s conclusion should clearly reflect your core message. This is your chance to reinforce the takeaways and leave the audience thinking about your presentation long after it ends.

Identifying Key Points

Start by recognizing what you want your audience to remember. Think about the main ideas that shaped your talk. Make a list like this:

- The problem your presentation addresses.

- The evidence that supports your argument.

- The solution you propose or the action you want the audience to take.

These key points become the pillars of your core message.

Contextualizing the Presentation

Provide context by briefly relating back to the content of the whole presentation. For example:

- Reference a statistic you shared in the opening, and how it ties into the conclusion.

- Mention a case study that underlines the importance of your message.

Connecting these elements gives your message cohesion and makes your conclusion resonate with the framework of your presentation.

30 Example Phrases: How to Conclude a Presentation

- 1. “In summary, let’s revisit the key takeaways from today’s presentation.”

- 2. “Thank you for your attention. Let’s move forward together.”

- 3. “That brings us to the end. I’m open to any questions you may have.”

- 4. “I’ll leave you with this final thought to ponder as we conclude.”

- 5. “Let’s recap the main points before we wrap up.”

- 6. “I appreciate your engagement. Now, let’s turn these ideas into action.”

- 7. “We’ve covered a lot today. To conclude, remember these crucial points.”

- 8. “As we reach the end, I’d like to emphasize our call to action.”

- 9. “Before we close, let’s quickly review what we’ve learned.”

- 10. “Thank you for joining me on this journey. I look forward to our next steps.”

- 11. “In closing, I’d like to thank everyone for their participation.”

- 12. “Let’s conclude with a reminder of the impact we can make together.”

- 13. “To wrap up our session, here’s a brief summary of our discussion.”

- 14. “I’m grateful for the opportunity to present to you. Any final thoughts?”

- 15. “And that’s a wrap. I welcome any final questions or comments.”

- 16. “As we conclude, let’s remember the objectives we’ve set today.”

- 17. “Thank you for your time. Let’s apply these insights to achieve success.”

- 18. “In conclusion, your feedback is valuable, and I’m here to listen.”

- 19. “Before we part, let’s take a moment to reflect on our key messages.”

- 20. “I’ll end with an invitation for all of us to take the next step.”

- 21. “As we close, let’s commit to the goals we’ve outlined today.”

- 22. “Thank you for your attention. Let’s keep the conversation going.”

- 23. “In conclusion, let’s make a difference, starting now.”

- 24. “I’ll leave you with these final words to consider as we end our time together.”

- 25. “Before we conclude, remember that change starts with our actions today.”

- 26. “Thank you for the lively discussion. Let’s continue to build on these ideas.”

- 27. “As we wrap up, I encourage you to reach out with any further questions.”

- 28. “In closing, I’d like to express my gratitude for your valuable input.”

- 29. “Let’s conclude on a high note and take these learnings forward.”

- 30. “Thank you for your time today. Let’s end with a commitment to progress.”

Summarizing the Main Points

When you reach the end of your presentation, summarizing the main points helps your audience retain the important information you’ve shared. Crafting a memorable summary enables your listeners to walk away with a clear understanding of your message.

Effective Methods of Summarization

To effectively summarize your presentation, you need to distill complex information into concise, digestible pieces. Start by revisiting the overarching theme of your talk and then narrow down to the core messages. Use plain language and imagery to make the enduring ideas stick. Here are some examples of how to do this:

- Use analogies that relate to common experiences to recap complex concepts.

- Incorporate visuals or gestures that reinforce your main arguments.

The Rule of Three

The Rule of Three is a classic writing and communication principle. It means presenting ideas in a trio, which is a pattern that’s easy for people to understand and remember. For instance, you might say, “Our plan will save time, cut costs, and improve quality.” This structure has a pleasing rhythm and makes the content more memorable. Some examples include:

- “This software is fast, user-friendly, and secure.”

- Pointing out a product’s “durability, affordability, and eco-friendliness.”

Reiterating the Main Points

Finally, you want to circle back to the key takeaways of your presentation. Rephrase your main points without introducing new information. This reinforcement supports your audience’s memory and understanding of the material. You might summarize key takeaways like this:

- Mention the problem you addressed, the solution you propose, and the benefits of this solution.

- Highlighting the outcomes of adopting your strategy: higher efficiency, greater satisfaction, and increased revenue.

Creating a Strong Conclusion

The final moments of your presentation are your chance to leave your audience with a powerful lasting impression. A strong conclusion is more than just summarizing—it’s your opportunity to invoke thought, inspire action, and make your message memorable.

Incorporating a Call to Action

A call to action is your parting request to your audience. You want to inspire them to take a specific action or think differently as a result of what they’ve heard. To do this effectively:

- Be clear about what you’re asking.

- Explain why their action is needed.

- Make it as simple as possible for them to take the next steps.

Example Phrases:

- “Start making a difference today by…”

- “Join us in this effort by…”

- “Take the leap and commit to…”

Leaving a Lasting Impression

End your presentation with something memorable. This can be a powerful quote, an inspirational statement, or a compelling story that underscores your main points. The goal here is to resonate with your audience on an emotional level so that your message sticks with them long after they leave.

- “In the words of [Influential Person], ‘…'”

- “Imagine a world where…”

- “This is more than just [Topic]; it’s about…”

Enhancing Audience Engagement

To hold your audience’s attention and ensure they leave with a lasting impression of your presentation, fostering interaction is key.

Q&A Sessions

It’s important to integrate a Q&A session because it allows for direct communication between you and your audience. This interactive segment helps clarify any uncertainties and encourages active participation. Plan for this by designating a time slot towards the end of your presentation and invite questions that promote discussion.

- “I’d love to hear your thoughts; what questions do you have?”

- “Let’s dive into any questions you might have. Who would like to start?”

- “Feel free to ask any questions, whether they’re clarifications or deeper inquiries about the topic.”

Encouraging Audience Participation

Getting your audience involved can transform a good presentation into a great one. Use open-ended questions that provoke thought and allow audience members to reflect on how your content relates to them. Additionally, inviting volunteers to participate in a demonstration or share their experiences keeps everyone engaged and adds a personal touch to your talk.

- “Could someone give me an example of how you’ve encountered this in your work?”

- “I’d appreciate a volunteer to help demonstrate this concept. Who’s interested?”

- “How do you see this information impacting your daily tasks? Let’s discuss!”

Delivering a Persuasive Ending

At the end of your presentation, you have the power to leave a lasting impact on your audience. A persuasive ending can drive home your key message and encourage action.

Sales and Persuasion Tactics

When you’re concluding a presentation with the goal of selling a product or idea, employ carefully chosen sales and persuasion tactics. One method is to summarize the key benefits of your offering, reminding your audience why it’s important to act. For example, if you’ve just presented a new software tool, recap how it will save time and increase productivity. Another tactic is the ‘call to action’, which should be clear and direct, such as “Start your free trial today to experience the benefits first-hand!” Furthermore, using a touch of urgency, like “Offer expires soon!”, can nudge your audience to act promptly.

Final Impressions and Professionalism

Your closing statement is a chance to solidify your professional image and leave a positive impression. It’s important to display confidence and poise. Consider thanking your audience for their time and offering to answer any questions. Make sure to end on a high note by summarizing your message in a concise and memorable way. If your topic was on renewable energy, you might conclude by saying, “Let’s take a leap towards a greener future by adopting these solutions today.” This reinforces your main points and encourages your listeners to think or act differently when they leave.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are some creative strategies for ending a presentation memorably.

To end your presentation in a memorable way, consider incorporating a call to action that engages your audience to take the next step. Another strategy is to finish with a thought-provoking question or a surprising fact that resonates with your listeners.

Can you suggest some powerful quotes suitable for concluding a presentation?

Yes, using a quote can be very effective. For example, Maya Angelou’s “People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel,” can reinforce the emotional impact of your presentation.

What is an effective way to write a conclusion that summarizes a presentation?

An effective conclusion should recap the main points succinctly, highlighting what you want your audience to remember. A good way to conclude is by restating your thesis and then briefly summarizing the supporting points you made.

As a student, how can I leave a strong impression with my presentation’s closing remarks?

To leave a strong impression, consider sharing a personal anecdote related to your topic that demonstrates passion and conviction. This helps humanize your content and makes the message more relatable to your audience.

How can I appropriately thank my audience at the close of my presentation?

A simple and sincere expression of gratitude is always appropriate. You might say, “Thank you for your attention and engagement today,” to convey appreciation while also acknowledging their participation.

What are some examples of a compelling closing sentence in a presentation?

A compelling closing sentence could be something like, “Together, let’s take the leap towards a greener future,” if you’re presenting on sustainability. This sentence is impactful, calls for united action, and leaves your audience with a clear message.

- How to Build Rapport: Effective Techniques

- Active Listening (Techniques, Examples, Tips)

- Effective Nonverbal Communication in the Workplace (Examples)

- What is Problem Solving? (Steps, Techniques, Examples)

- 2 Examples of an Effective and Warm Letter of Welcome

- Effective Interview Confirmation Email (Examples)

Presentation of Data

Statistics deals with the collection, presentation and analysis of the data, as well as drawing meaningful conclusions from the given data. Generally, the data can be classified into two different types, namely primary data and secondary data. If the information is collected by the investigator with a definite objective in their mind, then the data obtained is called the primary data. If the information is gathered from a source, which already had the information stored, then the data obtained is called secondary data. Once the data is collected, the presentation of data plays a major role in concluding the result. Here, we will discuss how to present the data with many solved examples.

What is Meant by Presentation of Data?

As soon as the data collection is over, the investigator needs to find a way of presenting the data in a meaningful, efficient and easily understood way to identify the main features of the data at a glance using a suitable presentation method. Generally, the data in the statistics can be presented in three different forms, such as textual method, tabular method and graphical method.

Presentation of Data Examples

Now, let us discuss how to present the data in a meaningful way with the help of examples.

Consider the marks given below, which are obtained by 10 students in Mathematics:

36, 55, 73, 95, 42, 60, 78, 25, 62, 75.

Find the range for the given data.

Given Data: 36, 55, 73, 95, 42, 60, 78, 25, 62, 75.

The data given is called the raw data.

First, arrange the data in the ascending order : 25, 36, 42, 55, 60, 62, 73, 75, 78, 95.

Therefore, the lowest mark is 25 and the highest mark is 95.

We know that the range of the data is the difference between the highest and the lowest value in the dataset.

Therefore, Range = 95-25 = 70.

Note: Presentation of data in ascending or descending order can be time-consuming if we have a larger number of observations in an experiment.

Now, let us discuss how to present the data if we have a comparatively more number of observations in an experiment.

Consider the marks obtained by 30 students in Mathematics subject (out of 100 marks)

10, 20, 36, 92, 95, 40, 50, 56, 60, 70, 92, 88, 80, 70, 72, 70, 36, 40, 36, 40, 92, 40, 50, 50, 56, 60, 70, 60, 60, 88.

In this example, the number of observations is larger compared to example 1. So, the presentation of data in ascending or descending order is a bit time-consuming. Hence, we can go for the method called ungrouped frequency distribution table or simply frequency distribution table . In this method, we can arrange the data in tabular form in terms of frequency.

For example, 3 students scored 50 marks. Hence, the frequency of 50 marks is 3. Now, let us construct the frequency distribution table for the given data.

Therefore, the presentation of data is given as below:

The following example shows the presentation of data for the larger number of observations in an experiment.

Consider the marks obtained by 100 students in a Mathematics subject (out of 100 marks)

95, 67, 28, 32, 65, 65, 69, 33, 98, 96,76, 42, 32, 38, 42, 40, 40, 69, 95, 92, 75, 83, 76, 83, 85, 62, 37, 65, 63, 42, 89, 65, 73, 81, 49, 52, 64, 76, 83, 92, 93, 68, 52, 79, 81, 83, 59, 82, 75, 82, 86, 90, 44, 62, 31, 36, 38, 42, 39, 83, 87, 56, 58, 23, 35, 76, 83, 85, 30, 68, 69, 83, 86, 43, 45, 39, 83, 75, 66, 83, 92, 75, 89, 66, 91, 27, 88, 89, 93, 42, 53, 69, 90, 55, 66, 49, 52, 83, 34, 36.

Now, we have 100 observations to present the data. In this case, we have more data when compared to example 1 and example 2. So, these data can be arranged in the tabular form called the grouped frequency table. Hence, we group the given data like 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, ….,90-99 (As our data is from 23 to 98). The grouping of data is called the “class interval” or “classes”, and the size of the class is called “class-size” or “class-width”.

In this case, the class size is 10. In each class, we have a lower-class limit and an upper-class limit. For example, if the class interval is 30-39, the lower-class limit is 30, and the upper-class limit is 39. Therefore, the least number in the class interval is called the lower-class limit and the greatest limit in the class interval is called upper-class limit.

Hence, the presentation of data in the grouped frequency table is given below:

Hence, the presentation of data in this form simplifies the data and it helps to enable the observer to understand the main feature of data at a glance.

Practice Problems

- The heights of 50 students (in cms) are given below. Present the data using the grouped frequency table by taking the class intervals as 160 -165, 165 -170, and so on. Data: 161, 150, 154, 165, 168, 161, 154, 162, 150, 151, 162, 164, 171, 165, 158, 154, 156, 172, 160, 170, 153, 159, 161, 170, 162, 165, 166, 168, 165, 164, 154, 152, 153, 156, 158, 162, 160, 161, 173, 166, 161, 159, 162, 167, 168, 159, 158, 153, 154, 159.

- Three coins are tossed simultaneously and each time the number of heads occurring is noted and it is given below. Present the data using the frequency distribution table. Data: 0, 1, 2, 2, 1, 2, 3, 1, 3, 0, 1, 3, 1, 1, 2, 2, 0, 1, 2, 1, 3, 0, 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 2, 2, 0.

To learn more Maths-related concepts, stay tuned with BYJU’S – The Learning App and download the app today!

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

A Reader on Data Visualization

Chapter 7 conclusion.

As we conclude our brief study on data visualization, it is clear that the field is rich in potential applications in diverse disciplines, at the same time we need to be aware of its practical and ethical complexities. In the previous chapters, we have presented some important theoretical and practical principles to keep in mind when designing a data visualization. We have also discussed and critiqued several examples of data visualizations, learning common pitfalls and helpful tricks along the way. As we have seen, developing an effective and ethical data visualization is a complex process. In this chapter we will touch upon the future of data visualization and additional resources for data visualizers.

7.1 The Future of Data Visualization

Towler ( 2015 )

Data visualization is entering a new era. Emerging sources of intelligence, theoretical developments and advances in multidimensional imaging are reshaping the potential value that analytics and insights can provide, with visualization playing a key role. The principles of effective data visualization won’t change. However, nextgen technologies and evolving cognitive frameworks are opening new horizons, moving data visualization from art to science.

Looking back, much attention has been given to the principles of effective data visualization, such as substance, context and actionability. As timeless tenets that will continue to be important, regardless of medium or format, a brief review seems in order:

Effective data visualization should be substantive And while creative visuals can enhance interest and memory, embellishment can’t make up for lack of substance. According to purist Edward Tufte, “Every single pixel should testify directly to content.”

Visualization should be accurate and contextual. David McCandless’s Billion Dollar O’Gram provides an example of how greater meaning can be added by incorporating the bigger picture. According to McCandless, “Absolute figures in a connected world don’t give you the whole picture. They’re not as true as they could be. We need relative figures that are connected to other data so that we can see a fuller picture.”

Billion Dollar O’Gram

(Source: Towler ( 2015 ) )

- More than anything else, data visualization should facilitate decision-making , a goal that is difficult to achieve for many. According to a recent [KPMG study] (International 2015 ) , while data and analytics are deemed increasingly important to organizations, generating actionable insights remains a top challenge.

7.1.1 Recent Developments

Consider the Internet of Things, Network and Complexity Theories, and recent developments in multidimensional visualization, we can clearly see how data visualization has evolved along with the field.

The Internet has transformed the way we visualize information through a better understanding of networks and an explosion in profile, behavioral and attitudinal data. Sociograms, for example, have gone from relatively simple graphs to multifaceted relational maps, as illustrated in the following two charts, courtesy of the Journal of Social Structure and the Leadership Learning Community.

Figure 2:Pre-Internet sociogram

Figure 3:Internet-age sociogram

The Internet of Things is expected to have a similar impact, with billions of connected devices capturing human and machine activity. Fully capitalizing on the data generated will require further advances in our ability to synthesize and display spatiotemporal activities.

Network Theory has been in use for decades, with its earliest applications largely in social structure analysis. More recently, Network Theory is being applied to understand relationships and interactions in a variety of domains, such as crime prevention and disease management. Dirk Brockmann and Dirk Helbling’s work modeling the spread of infectious diseases provides an example of the power that Network Theory holds.

7.1.2 Future Direction

Towler ( 2015 ) As the world becomes increasingly interconnected and interdependent, opportunities to generate value through data visualization will only increase. The Internet of Things will have a profound effect on the role that data visualization can play in organizations and society, improving our ability to understand how humans and machines interact with each other and the environment. Application of evolving cognitive frameworks, such as Network and Complexity Theories, will help us better reflect dynamic and intricate structural dependencies. Advances in multidimensional visualization will allow us to more effectively synthesize and explore spatiotemporal conditions.

Below are the salient points from the Data Visualization Summit 2016 (Source: Denham ( n.d. ) ) key note address highlighting the future of data visualization.

- Supporting big data 3 Vs at scale: like 100X for Volume, 10X for Velocity, 5X for Variety.

- The end-to-end set up time will be much shorter, the learning curve to be a data viz expert would be within days.

- More flexible user interfaces with easier ways to surface complicated cases w/o any further advanced coding for discovering the underlying knowledge and relationships, such as social graphing, 3+ dimensional graphing, etc.

- More integration could happen here, such as new intelligent features in data viz application for predictive modeling, pattern discovery, automatic alerting, etc.

- Given the recent crazy popularity in AR technology for Pokemon Go, interesting data viz application to support AR or VR will soon become available

With more and more data, the field of Data Science is challenged with the task of making meaningful sense out of the data. Data visualization tools slice and dice the data and present insights to scientists and data visualization will be the center piece in the analytics domain. Few of the fields which are really pushing its limits are Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality and Real Time Analytics based on Live Streaming data. An interesting article on the future of data visualization in the year 2019 and beyond (Source: Studio ( 2019 ) ) based on a survey from the data visualization community.

7.2 Key Lessons Going Forward

7.2.1 laying the groundwork for data visualization.

(SAS 2014 ) Before implementing new technology, there are some steps you need to take. Not only do you need to have a solid grasp on your data, you also need to understand your goals, needs and audience. Preparing your organization for data visualization technology requires that you first:

- Understand the data you’re trying to visualize, including its size and cardinality (the uniqueness of data values in a column).

- Determine what you’re trying to visualize and what kind of information you want to communicate.

- Know your audience and understand how it processes visual information.

- Use a visual that conveys the information in the best and simplest form for your audience.

Once you’ve answered those initial questions about the type of data you have and the audience who’ll be consuming the information, you need to prepare for the amount of data you’ll be working with. Big data brings new challenges to visualization because large volumes, different varieties and varying velocities must be taken into account. Plus, data is often generated faster that it can be managed and analyzed.

7.2.2 How Is It Being Used?

(SAS 2014 ) Regardless of industry or size, all types of businesses are using data visualization to help make sense of their data. Here’s how.

Comprehend information quickly By using graphical representations of business information, businesses are able to see large amounts of data in clear, cohesive ways – and draw conclusions from that information. And since it’s significantly faster to analyze information in graphical format (as opposed to analyzing information in spreadsheets), businesses can address problems or answer questions in a more timely manner.

Identify relationships and patterns Even extensive amounts of complicated data start to make sense when presented graphically; businesses can recognize parameters that are highly correlated. Some of the correlations will be obvious, but others won’t. Identifying those relationships helps organizations focus on areas most likely to influence their most important goals.

Pinpoint emerging trends Using data visualization to discover trends – both in the business and in the market – can give businesses an edge over the competition, and ultimately affect the bottom line. It’s easy to spot outliers that affect product quality or customer churn, and address issues before they become bigger problems.

Communicate the story to others Once a business has uncovered new insights from visual analytics, the next step is to communicate those insights to others. Using charts, graphs or other visually impactful representations of data is important in this step because it’s engaging and gets the message across quickly.

Improved collaboration among work teams Data visualization makes it easier to gain vital information, identify trends, collaborate at a likeminded pace, and from there put decisions to action — all with much greater speed than is generally allowed by presentations that lack the proper visual tools.

Establish Clear Correlation Between Business Operations And Activities Since the data is visualized in a highly comprehensive and interactive manner, establishing existing or possible correlations between various business operations comes in easy here. This gives business leaders a clear insight into business performance and needs for further strategies. Data visualization allows decision makers to make sense out of the visible patterns and parallel operations in terms of the overall business performance. It also allows them to establish a correlation between the daily tasks and the long-term outcomes for these in terms of business performance.

###Helpful tips for a good visualization * Don’t try to be too cute. Using all the fancy features of a visualization tool can lead to complex and confusing graphics. Just because you have a flashy hammer, it does not mean that everything is a nail. Don’t lose your purpose in your infatuation with a new tool or feature. Stick to good design principles, and keep it simple (as was mentioned in the discussion about Patterns).

Don’t provide more data than you need to tell your story. Humans have a tendency to want to create visualizations with multi-drill downs, filters, and tables. This is fine for ad hoc analysis, but if we are presenting a visual with a single story or argument, we must make sure every piece of data included plays a meaningful part in the story.

Have more data to show what-ifs. A great way to provide more information in a visualization is to use filters to provide what-if views. Having filters for different scenarios, options, and time slices provide the user a way to review and discover various perspectives on your data. Just make sure the user does not have to work too hard to get there and that they do not get lost in the data.

Deliver value in your visualization. Many graphs may be aesthetically pleasing or exciting but deliver no value. A graph with good value should deliver important insights to aid decision-making or prompt an action. Keep in mind, the main objective of a visualization is to deliver value, and each design decision should help achieve this.

Understanding your audience is the most difficult and important part of developing a visualization. Different audiences will feel differently about the same chart. So when we develop the argument from the data, we should keep our intended audience in mind.

Share what you have found. A visualization can be an effective influencer if used in the correct way and at the correct time.

Think as author / reader When designing graphs, try to stand at the reader side, to check whether the graph is making sense or if there is any misleading information being showcased. As a reader, one needs to detect if there is any visualization deception in the graph. Before making any conclusion, understanding details and information the graph is providing like legend, caption, numbers, etc. is important.

Do Calculations Accurate representation of data is necessary. Sometimes the original data cannot strongly support the main thesis. In that case, some extra calcuations based on the original dataset could make the idea more clear.

It should be ethical Visualization : Research has found that even if viewers do not support an idea, data presented in charts can persuade viewers on the subject matter. It means that visualization can also be used to mislead either unintentionally or intentionally. Misleading, incomprehensible, or incredible data visualization can jeopardize people’s trust, goodwill, or faith in research and advocacy on vital human rights issues. So, certain standards should be followed in order to generate meaningful, accurate and ethical visuals.

7.3 Additional Resources for Aspiring Data Visualizers

The field of data visualization is huge, and the capability of linking storytelling and data-experience design is a commodity. An aspiring visualizer seeking to further broaden his/her knowledge might find these additional resources helpful.

7.3.1 Tableau Community

(Tableau Software 2018 a ) helps you to explore Tableau further :

- It will help us enhance our learning

- Get answers for most of your doubts In tableau

- Post new questions and crowd source answers

- Attend events, seminars and join conferences conducted locally/ globally

- Give back to the community once you become an expert in that field

There are very active Tableau social media groups (Tableau Software 2018 b ) :

- Tableau Enthusiasts: LinkedIn Group (19K members)

- Tableau Software Fans & Friends: LinkedIn Group (45k members)

Describe Artists with Emoji . Using the data from Spotify, the author listed the 10 most distinctive emoji used in the playlists related to popular artists. The table being used in this visual is very straight-forward to link artist to the emojis and is very easy to compare among artists. When you hover over the emoji, further information is presented.

Anaconda Python for visualization (na 2017 b ) :

Anaconda Python provides different packages that can help with more robust data sets and provide different packages that can offer a variety of visualization solutions (na 2017 b ) .

Bokeh One of them is Bokeh an open source interactive visualization for Python (na 2019 ) . Elegant, concise versatile graphics . High performance interactivity over large streaming data sets . Easily create interactive plots, dashboard and data applications

Matplot (na 2017 a )

Is a Python 2D plotting library and object oriented. This package can do the following: . Lines, bars and markers . Images, contours and fields . Statistics graphs . Pie and polar charts . Text, labels and annotations . Pyplot . Others Other packages: Datashader & Holoviews Anaconda community (na 2017 b ) provides many solution and resources for all visualization packages.

Altair Altair is a declarative statistical visualization library for Python (Visualization 2019 ) There are gallerries and it is a powerful and concise visualization tool.

7.3.2 D3.js Community

D3 stands for Data-Driven Documents .The best place to start with D3.js (version 5.9.2) is the D3.js official portal itself ( https://d3js.org/ ). It has features like:

- Introduction, with the help of code snippets.

- Installation guide.

- Features guide.

- It also has a reference guide.

- Newsletters.

- Blogs which introduces D3.js with examples.

- Video lectures which makes the learning experience more interesting.

D3.js has a large and growing presence on GitHub .One can find,clone and use all the needed materials. The content is as follows :

- It has a source repository( https://github.com/d3/d3 ) which allows users to clone ad use the packages.

- It links you to vaious othrer platforms for discussion like: stack overflow ( https://stackoverflow.com/questions/tagged/d3.js ), Google Group ( https://groups.google.com/forum/#!forum/d3-js ), Slack ( https://d3js.slack.com/ ).

- It has an extensive tutorials repository on GitHub ( https://github.com/d3/d3/wiki/Tutorials ).

- It also has a Gallery on GitHub with code snippets for each visualization( https://github.com/d3/d3/wiki/Gallery )

- Links to official ( https://github.com/d3/d3/blob/master/API.md ) and community based modules( https://www.npmjs.com/search?q=keywords:d3-module ) for D3.js .

7.3.3 Blogs

Here are some blogs recommended by Tableau (Tableau Software 2018 c ) :

7.3.4 Useful Links on Data Visualization Resources, Trends, and Tutorials

Towler, Will. 2015. “Data Visualization: The Future of Data Visualization.” http://analytics-magazine.org/data-visualization-the-future-of-data-visualization/ .