15 Famous Experiments and Case Studies in Psychology

Psychology has seen thousands upon thousands of research studies over the years. Most of these studies have helped shape our current understanding of human thoughts, behavior, and feelings.

The psychology case studies in this list are considered classic examples of psychological case studies and experiments, which are still being taught in introductory psychology courses up to this day.

Some studies, however, were downright shocking and controversial that you’d probably wonder why such studies were conducted back in the day. Imagine participating in an experiment for a small reward or extra class credit, only to be left scarred for life. These kinds of studies, however, paved the way for a more ethical approach to studying psychology and implementation of research standards such as the use of debriefing in psychology research .

Case Study vs. Experiment

Before we dive into the list of the most famous studies in psychology, let us first review the difference between case studies and experiments.

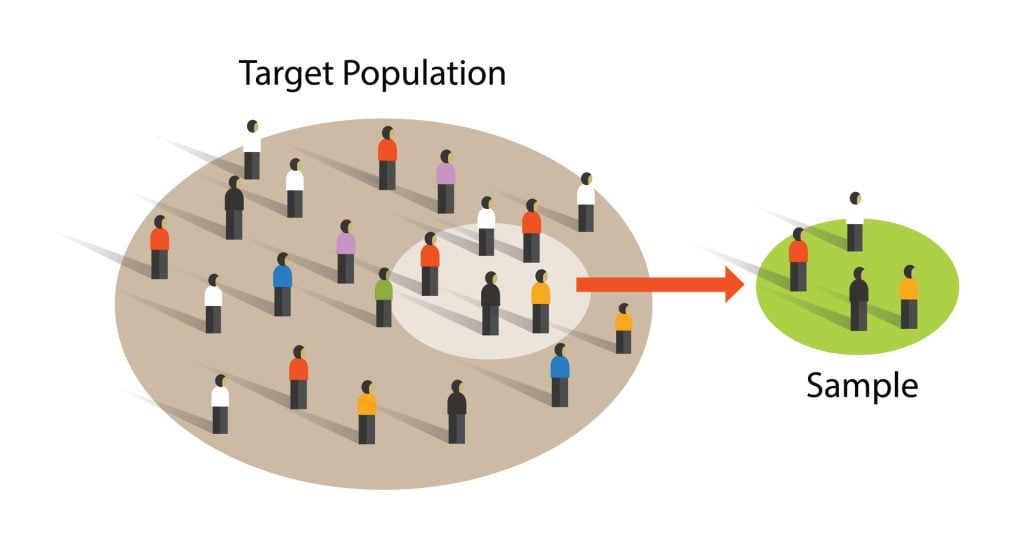

- It is an in-depth study and analysis of an individual, group, community, or phenomenon. The results of a case study cannot be applied to the whole population, but they can provide insights for further studies.

- It often uses qualitative research methods such as observations, surveys, and interviews.

- It is often conducted in real-life settings rather than in controlled environments.

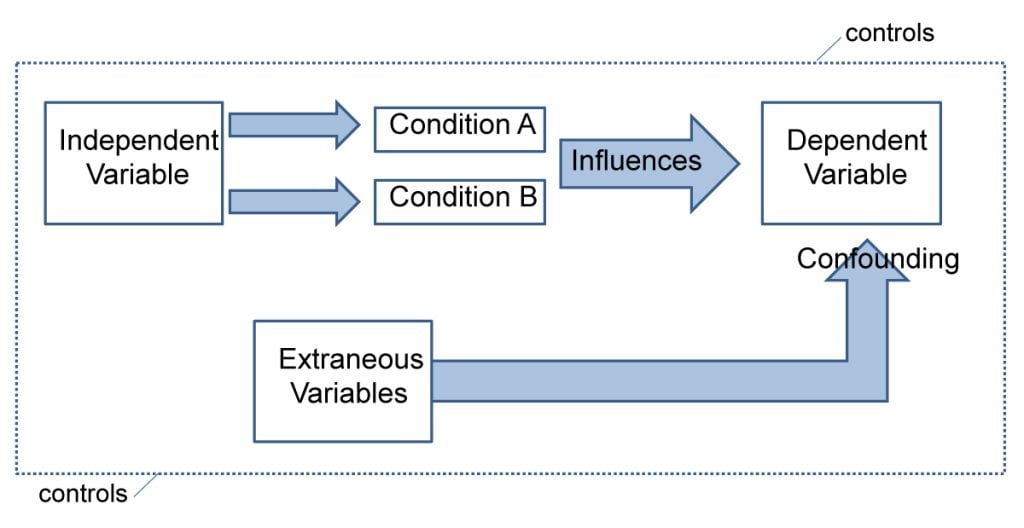

- An experiment is a type of study done on a sample or group of random participants, the results of which can be generalized to the whole population.

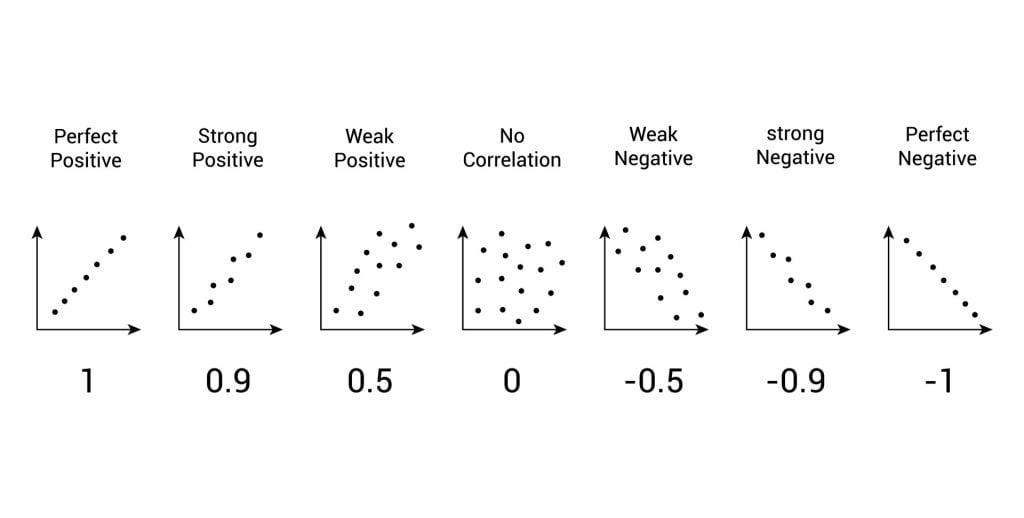

- It often uses quantitative research methods that rely on numbers and statistics.

- It is conducted in controlled environments, wherein some things or situations are manipulated.

See Also: Experimental vs Observational Studies

Famous Experiments in Psychology

1. the marshmallow experiment.

Psychologist Walter Mischel conducted the marshmallow experiment at Stanford University in the 1960s to early 1970s. It was a simple test that aimed to define the connection between delayed gratification and success in life.

The instructions were fairly straightforward: children ages 4-6 were presented a piece of marshmallow on a table and they were told that they would receive a second piece if they could wait for 15 minutes without eating the first marshmallow.

About one-third of the 600 participants succeeded in delaying gratification to receive the second marshmallow. Mischel and his team followed up on these participants in the 1990s, learning that those who had the willpower to wait for a larger reward experienced more success in life in terms of SAT scores and other metrics.

This case study also supported self-control theory , a theory in criminology that holds that people with greater self-control are less likely to end up in trouble with the law!

The classic marshmallow experiment, however, was debunked in a 2018 replication study done by Tyler Watts and colleagues.

This more recent experiment had a larger group of participants (900) and a better representation of the general population when it comes to race and ethnicity. In this study, the researchers found out that the ability to wait for a second marshmallow does not depend on willpower alone but more so on the economic background and social status of the participants.

2. The Bystander Effect

In 1694, Kitty Genovese was murdered in the neighborhood of Kew Gardens, New York. It was told that there were up to 38 witnesses and onlookers in the vicinity of the crime scene, but nobody did anything to stop the murder or call for help.

Such tragedy was the catalyst that inspired social psychologists Bibb Latane and John Darley to formulate the phenomenon called bystander effect or bystander apathy .

Subsequent investigations showed that this story was exaggerated and inaccurate, as there were actually only about a dozen witnesses, at least two of whom called the police. But the case of Kitty Genovese led to various studies that aim to shed light on the bystander phenomenon.

Latane and Darley tested bystander intervention in an experimental study . Participants were asked to answer a questionnaire inside a room, and they would either be alone or with two other participants (who were actually actors or confederates in the study). Smoke would then come out from under the door. The reaction time of participants was tested — how long would it take them to report the smoke to the authorities or the experimenters?

The results showed that participants who were alone in the room reported the smoke faster than participants who were with two passive others. The study suggests that the more onlookers are present in an emergency situation, the less likely someone would step up to help, a social phenomenon now popularly called the bystander effect.

3. Asch Conformity Study

Have you ever made a decision against your better judgment just to fit in with your friends or family? The Asch Conformity Studies will help you understand this kind of situation better.

In this experiment, a group of participants were shown three numbered lines of different lengths and asked to identify the longest of them all. However, only one true participant was present in every group and the rest were actors, most of whom told the wrong answer.

Results showed that the participants went for the wrong answer, even though they knew which line was the longest one in the first place. When the participants were asked why they identified the wrong one, they said that they didn’t want to be branded as strange or peculiar.

This study goes to show that there are situations in life when people prefer fitting in than being right. It also tells that there is power in numbers — a group’s decision can overwhelm a person and make them doubt their judgment.

4. The Bobo Doll Experiment

The Bobo Doll Experiment was conducted by Dr. Albert Bandura, the proponent of social learning theory .

Back in the 1960s, the Nature vs. Nurture debate was a popular topic among psychologists. Bandura contributed to this discussion by proposing that human behavior is mostly influenced by environmental rather than genetic factors.

In the Bobo Doll Experiment, children were divided into three groups: one group was shown a video in which an adult acted aggressively toward the Bobo Doll, the second group was shown a video in which an adult play with the Bobo Doll, and the third group served as the control group where no video was shown.

The children were then led to a room with different kinds of toys, including the Bobo Doll they’ve seen in the video. Results showed that children tend to imitate the adults in the video. Those who were presented the aggressive model acted aggressively toward the Bobo Doll while those who were presented the passive model showed less aggression.

While the Bobo Doll Experiment can no longer be replicated because of ethical concerns, it has laid out the foundations of social learning theory and helped us understand the degree of influence adult behavior has on children.

5. Blue Eye / Brown Eye Experiment

Following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, third-grade teacher Jane Elliott conducted an experiment in her class. Although not a formal experiment in controlled settings, A Class Divided is a good example of a social experiment to help children understand the concept of racism and discrimination.

The class was divided into two groups: blue-eyed children and brown-eyed children. For one day, Elliott gave preferential treatment to her blue-eyed students, giving them more attention and pampering them with rewards. The next day, it was the brown-eyed students’ turn to receive extra favors and privileges.

As a result, whichever group of students was given preferential treatment performed exceptionally well in class, had higher quiz scores, and recited more frequently; students who were discriminated against felt humiliated, answered poorly in tests, and became uncertain with their answers in class.

This study is now widely taught in sociocultural psychology classes.

6. Stanford Prison Experiment

One of the most controversial and widely-cited studies in psychology is the Stanford Prison Experiment , conducted by Philip Zimbardo at the basement of the Stanford psychology building in 1971. The hypothesis was that abusive behavior in prisons is influenced by the personality traits of the prisoners and prison guards.

The participants in the experiment were college students who were randomly assigned as either a prisoner or a prison guard. The prison guards were then told to run the simulated prison for two weeks. However, the experiment had to be stopped in just 6 days.

The prison guards abused their authority and harassed the prisoners through verbal and physical means. The prisoners, on the other hand, showed submissive behavior. Zimbardo decided to stop the experiment because the prisoners were showing signs of emotional and physical breakdown.

Although the experiment wasn’t completed, the results strongly showed that people can easily get into a social role when others expect them to, especially when it’s highly stereotyped .

7. The Halo Effect

Have you ever wondered why toothpastes and other dental products are endorsed in advertisements by celebrities more often than dentists? The Halo Effect is one of the reasons!

The Halo Effect shows how one favorable attribute of a person can gain them positive perceptions in other attributes. In the case of product advertisements, attractive celebrities are also perceived as intelligent and knowledgeable of a certain subject matter even though they’re not technically experts.

The Halo Effect originated in a classic study done by Edward Thorndike in the early 1900s. He asked military commanding officers to rate their subordinates based on different qualities, such as physical appearance, leadership, dependability, and intelligence.

The results showed that high ratings of a particular quality influences the ratings of other qualities, producing a halo effect of overall high ratings. The opposite also applied, which means that a negative rating in one quality also correlated to negative ratings in other qualities.

Experiments on the Halo Effect came in various formats as well, supporting Thorndike’s original theory. This phenomenon suggests that our perception of other people’s overall personality is hugely influenced by a quality that we focus on.

8. Cognitive Dissonance

There are experiences in our lives when our beliefs and behaviors do not align with each other and we try to justify them in our minds. This is cognitive dissonance , which was studied in an experiment by Leon Festinger and James Carlsmith back in 1959.

In this experiment, participants had to go through a series of boring and repetitive tasks, such as spending an hour turning pegs in a wooden knob. After completing the tasks, they were then paid either $1 or $20 to tell the next participants that the tasks were extremely fun and enjoyable. Afterwards, participants were asked to rate the experiment. Those who were given $1 rated the experiment as more interesting and fun than those who received $20.

The results showed that those who received a smaller incentive to lie experienced cognitive dissonance — $1 wasn’t enough incentive for that one hour of painstakingly boring activity, so the participants had to justify that they had fun anyway.

Famous Case Studies in Psychology

9. little albert.

In 1920, behaviourist theorists John Watson and Rosalie Rayner experimented on a 9-month-old baby to test the effects of classical conditioning in instilling fear in humans.

This was such a controversial study that it gained popularity in psychology textbooks and syllabi because it is a classic example of unethical research studies done in the name of science.

In one of the experiments, Little Albert was presented with a harmless stimulus or object, a white rat, which he wasn’t scared of at first. But every time Little Albert would see the white rat, the researchers would play a scary sound of hammer and steel. After about 6 pairings, Little Albert learned to fear the rat even without the scary sound.

Little Albert developed signs of fear to different objects presented to him through classical conditioning . He even generalized his fear to other stimuli not present in the course of the experiment.

10. Phineas Gage

Phineas Gage is such a celebrity in Psych 101 classes, even though the way he rose to popularity began with a tragic accident. He was a resident of Central Vermont and worked in the construction of a new railway line in the mid-1800s. One day, an explosive went off prematurely, sending a tamping iron straight into his face and through his brain.

Gage survived the accident, fortunately, something that is considered a feat even up to this day. He managed to find a job as a stagecoach after the accident. However, his family and friends reported that his personality changed so much that “he was no longer Gage” (Harlow, 1868).

New evidence on the case of Phineas Gage has since come to light, thanks to modern scientific studies and medical tests. However, there are still plenty of mysteries revolving around his brain damage and subsequent recovery.

11. Anna O.

Anna O., a social worker and feminist of German Jewish descent, was one of the first patients to receive psychoanalytic treatment.

Her real name was Bertha Pappenheim and she inspired much of Sigmund Freud’s works and books on psychoanalytic theory, although they hadn’t met in person. Their connection was through Joseph Breuer, Freud’s mentor when he was still starting his clinical practice.

Anna O. suffered from paralysis, personality changes, hallucinations, and rambling speech, but her doctors could not find the cause. Joseph Breuer was then called to her house for intervention and he performed psychoanalysis, also called the “talking cure”, on her.

Breuer would tell Anna O. to say anything that came to her mind, such as her thoughts, feelings, and childhood experiences. It was noted that her symptoms subsided by talking things out.

However, Breuer later referred Anna O. to the Bellevue Sanatorium, where she recovered and set out to be a renowned writer and advocate of women and children.

12. Patient HM

H.M., or Henry Gustav Molaison, was a severe amnesiac who had been the subject of countless psychological and neurological studies.

Henry was 27 when he underwent brain surgery to cure the epilepsy that he had been experiencing since childhood. In an unfortunate turn of events, he lost his memory because of the surgery and his brain also became unable to store long-term memories.

He was then regarded as someone living solely in the present, forgetting an experience as soon as it happened and only remembering bits and pieces of his past. Over the years, his amnesia and the structure of his brain had helped neuropsychologists learn more about cognitive functions .

Suzanne Corkin, a researcher, writer, and good friend of H.M., recently published a book about his life. Entitled Permanent Present Tense , this book is both a memoir and a case study following the struggles and joys of Henry Gustav Molaison.

13. Chris Sizemore

Chris Sizemore gained celebrity status in the psychology community when she was diagnosed with multiple personality disorder, now known as dissociative identity disorder.

Sizemore has several alter egos, which included Eve Black, Eve White, and Jane. Various papers about her stated that these alter egos were formed as a coping mechanism against the traumatic experiences she underwent in her childhood.

Sizemore said that although she has succeeded in unifying her alter egos into one dominant personality, there were periods in the past experienced by only one of her alter egos. For example, her husband married her Eve White alter ego and not her.

Her story inspired her psychiatrists to write a book about her, entitled The Three Faces of Eve , which was then turned into a 1957 movie of the same title.

14. David Reimer

When David was just 8 months old, he lost his penis because of a botched circumcision operation.

Psychologist John Money then advised Reimer’s parents to raise him as a girl instead, naming him Brenda. His gender reassignment was supported by subsequent surgery and hormonal therapy.

Money described Reimer’s gender reassignment as a success, but problems started to arise as Reimer was growing up. His boyishness was not completely subdued by the hormonal therapy. When he was 14 years old, he learned about the secrets of his past and he underwent gender reassignment to become male again.

Reimer became an advocate for children undergoing the same difficult situation he had been. His life story ended when he was 38 as he took his own life.

15. Kim Peek

Kim Peek was the inspiration behind Rain Man , an Oscar-winning movie about an autistic savant character played by Dustin Hoffman.

The movie was released in 1988, a time when autism wasn’t widely known and acknowledged yet. So it was an eye-opener for many people who watched the film.

In reality, Kim Peek was a non-autistic savant. He was exceptionally intelligent despite the brain abnormalities he was born with. He was like a walking encyclopedia, knowledgeable about travel routes, US zip codes, historical facts, and classical music. He also read and memorized approximately 12,000 books in his lifetime.

This list of experiments and case studies in psychology is just the tip of the iceberg! There are still countless interesting psychology studies that you can explore if you want to learn more about human behavior and dynamics.

You can also conduct your own mini-experiment or participate in a study conducted in your school or neighborhood. Just remember that there are ethical standards to follow so as not to repeat the lasting physical and emotional harm done to Little Albert or the Stanford Prison Experiment participants.

Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 70 (9), 1–70. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093718

Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1961). Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63 (3), 575–582. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045925

Elliott, J., Yale University., WGBH (Television station : Boston, Mass.), & PBS DVD (Firm). (2003). A class divided. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Films.

Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58 (2), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041593

Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison. Naval Research Review , 30 , 4-17.

Latane, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group inhibition of bystander intervention in emergencies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 10 (3), 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0026570

Mischel, W. (2014). The Marshmallow Test: Mastering self-control. Little, Brown and Co.

Thorndike, E. (1920) A Constant Error in Psychological Ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology , 4 , 25-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0071663

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of experimental psychology , 3 (1), 1.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- The 25 Most Influential Psychological Experiments in History

While each year thousands and thousands of studies are completed in the many specialty areas of psychology, there are a handful that, over the years, have had a lasting impact in the psychological community as a whole. Some of these were dutifully conducted, keeping within the confines of ethical and practical guidelines. Others pushed the boundaries of human behavior during their psychological experiments and created controversies that still linger to this day. And still others were not designed to be true psychological experiments, but ended up as beacons to the psychological community in proving or disproving theories.

This is a list of the 25 most influential psychological experiments still being taught to psychology students of today.

1. A Class Divided

Study conducted by: jane elliott.

Study Conducted in 1968 in an Iowa classroom

Experiment Details: Jane Elliott’s famous experiment was inspired by the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the inspirational life that he led. The third grade teacher developed an exercise, or better yet, a psychological experiment, to help her Caucasian students understand the effects of racism and prejudice.

Elliott divided her class into two separate groups: blue-eyed students and brown-eyed students. On the first day, she labeled the blue-eyed group as the superior group and from that point forward they had extra privileges, leaving the brown-eyed children to represent the minority group. She discouraged the groups from interacting and singled out individual students to stress the negative characteristics of the children in the minority group. What this exercise showed was that the children’s behavior changed almost instantaneously. The group of blue-eyed students performed better academically and even began bullying their brown-eyed classmates. The brown-eyed group experienced lower self-confidence and worse academic performance. The next day, she reversed the roles of the two groups and the blue-eyed students became the minority group.

At the end of the experiment, the children were so relieved that they were reported to have embraced one another and agreed that people should not be judged based on outward appearances. This exercise has since been repeated many times with similar outcomes.

For more information click here

2. Asch Conformity Study

Study conducted by: dr. solomon asch.

Study Conducted in 1951 at Swarthmore College

Experiment Details: Dr. Solomon Asch conducted a groundbreaking study that was designed to evaluate a person’s likelihood to conform to a standard when there is pressure to do so.

A group of participants were shown pictures with lines of various lengths and were then asked a simple question: Which line is longest? The tricky part of this study was that in each group only one person was a true participant. The others were actors with a script. Most of the actors were instructed to give the wrong answer. Strangely, the one true participant almost always agreed with the majority, even though they knew they were giving the wrong answer.

The results of this study are important when we study social interactions among individuals in groups. This study is a famous example of the temptation many of us experience to conform to a standard during group situations and it showed that people often care more about being the same as others than they do about being right. It is still recognized as one of the most influential psychological experiments for understanding human behavior.

3. Bobo Doll Experiment

Study conducted by: dr. alburt bandura.

Study Conducted between 1961-1963 at Stanford University

In his groundbreaking study he separated participants into three groups:

- one was exposed to a video of an adult showing aggressive behavior towards a Bobo doll

- another was exposed to video of a passive adult playing with the Bobo doll

- the third formed a control group

Children watched their assigned video and then were sent to a room with the same doll they had seen in the video (with the exception of those in the control group). What the researcher found was that children exposed to the aggressive model were more likely to exhibit aggressive behavior towards the doll themselves. The other groups showed little imitative aggressive behavior. For those children exposed to the aggressive model, the number of derivative physical aggressions shown by the boys was 38.2 and 12.7 for the girls.

The study also showed that boys exhibited more aggression when exposed to aggressive male models than boys exposed to aggressive female models. When exposed to aggressive male models, the number of aggressive instances exhibited by boys averaged 104. This is compared to 48.4 aggressive instances exhibited by boys who were exposed to aggressive female models.

While the results for the girls show similar findings, the results were less drastic. When exposed to aggressive female models, the number of aggressive instances exhibited by girls averaged 57.7. This is compared to 36.3 aggressive instances exhibited by girls who were exposed to aggressive male models. The results concerning gender differences strongly supported Bandura’s secondary prediction that children will be more strongly influenced by same-sex models. The Bobo Doll Experiment showed a groundbreaking way to study human behavior and it’s influences.

4. Car Crash Experiment

Study conducted by: elizabeth loftus and john palmer.

Study Conducted in 1974 at The University of California in Irvine

The participants watched slides of a car accident and were asked to describe what had happened as if they were eyewitnesses to the scene. The participants were put into two groups and each group was questioned using different wording such as “how fast was the car driving at the time of impact?” versus “how fast was the car going when it smashed into the other car?” The experimenters found that the use of different verbs affected the participants’ memories of the accident, showing that memory can be easily distorted.

This research suggests that memory can be easily manipulated by questioning technique. This means that information gathered after the event can merge with original memory causing incorrect recall or reconstructive memory. The addition of false details to a memory of an event is now referred to as confabulation. This concept has very important implications for the questions used in police interviews of eyewitnesses.

5. Cognitive Dissonance Experiment

Study conducted by: leon festinger and james carlsmith.

Study Conducted in 1957 at Stanford University

Experiment Details: The concept of cognitive dissonance refers to a situation involving conflicting:

This conflict produces an inherent feeling of discomfort leading to a change in one of the attitudes, beliefs or behaviors to minimize or eliminate the discomfort and restore balance.

Cognitive dissonance was first investigated by Leon Festinger, after an observational study of a cult that believed that the earth was going to be destroyed by a flood. Out of this study was born an intriguing experiment conducted by Festinger and Carlsmith where participants were asked to perform a series of dull tasks (such as turning pegs in a peg board for an hour). Participant’s initial attitudes toward this task were highly negative.

They were then paid either $1 or $20 to tell a participant waiting in the lobby that the tasks were really interesting. Almost all of the participants agreed to walk into the waiting room and persuade the next participant that the boring experiment would be fun. When the participants were later asked to evaluate the experiment, the participants who were paid only $1 rated the tedious task as more fun and enjoyable than the participants who were paid $20 to lie.

Being paid only $1 is not sufficient incentive for lying and so those who were paid $1 experienced dissonance. They could only overcome that cognitive dissonance by coming to believe that the tasks really were interesting and enjoyable. Being paid $20 provides a reason for turning pegs and there is therefore no dissonance.

6. Fantz’s Looking Chamber

Study conducted by: robert l. fantz.

Study Conducted in 1961 at the University of Illinois

Experiment Details: The study conducted by Robert L. Fantz is among the simplest, yet most important in the field of infant development and vision. In 1961, when this experiment was conducted, there very few ways to study what was going on in the mind of an infant. Fantz realized that the best way was to simply watch the actions and reactions of infants. He understood the fundamental factor that if there is something of interest near humans, they generally look at it.

To test this concept, Fantz set up a display board with two pictures attached. On one was a bulls-eye. On the other was the sketch of a human face. This board was hung in a chamber where a baby could lie safely underneath and see both images. Then, from behind the board, invisible to the baby, he peeked through a hole to watch what the baby looked at. This study showed that a two-month old baby looked twice as much at the human face as it did at the bulls-eye. This suggests that human babies have some powers of pattern and form selection. Before this experiment it was thought that babies looked out onto a chaotic world of which they could make little sense.

7. Hawthorne Effect

Study conducted by: henry a. landsberger.

Study Conducted in 1955 at Hawthorne Works in Chicago, Illinois

Landsberger performed the study by analyzing data from experiments conducted between 1924 and 1932, by Elton Mayo, at the Hawthorne Works near Chicago. The company had commissioned studies to evaluate whether the level of light in a building changed the productivity of the workers. What Mayo found was that the level of light made no difference in productivity. The workers increased their output whenever the amount of light was switched from a low level to a high level, or vice versa.

The researchers noticed a tendency that the workers’ level of efficiency increased when any variable was manipulated. The study showed that the output changed simply because the workers were aware that they were under observation. The conclusion was that the workers felt important because they were pleased to be singled out. They increased productivity as a result. Being singled out was the factor dictating increased productivity, not the changing lighting levels, or any of the other factors that they experimented upon.

The Hawthorne Effect has become one of the hardest inbuilt biases to eliminate or factor into the design of any experiment in psychology and beyond.

8. Kitty Genovese Case

Study conducted by: new york police force.

Study Conducted in 1964 in New York City

Experiment Details: The murder case of Kitty Genovese was never intended to be a psychological experiment, however it ended up having serious implications for the field.

According to a New York Times article, almost 40 neighbors witnessed Kitty Genovese being savagely attacked and murdered in Queens, New York in 1964. Not one neighbor called the police for help. Some reports state that the attacker briefly left the scene and later returned to “finish off” his victim. It was later uncovered that many of these facts were exaggerated. (There were more likely only a dozen witnesses and records show that some calls to police were made).

What this case later become famous for is the “Bystander Effect,” which states that the more bystanders that are present in a social situation, the less likely it is that anyone will step in and help. This effect has led to changes in medicine, psychology and many other areas. One famous example is the way CPR is taught to new learners. All students in CPR courses learn that they must assign one bystander the job of alerting authorities which minimizes the chances of no one calling for assistance.

9. Learned Helplessness Experiment

Study conducted by: martin seligman.

Study Conducted in 1967 at the University of Pennsylvania

Seligman’s experiment involved the ringing of a bell and then the administration of a light shock to a dog. After a number of pairings, the dog reacted to the shock even before it happened. As soon as the dog heard the bell, he reacted as though he’d already been shocked.

During the course of this study something unexpected happened. Each dog was placed in a large crate that was divided down the middle with a low fence. The dog could see and jump over the fence easily. The floor on one side of the fence was electrified, but not on the other side of the fence. Seligman placed each dog on the electrified side and administered a light shock. He expected the dog to jump to the non-shocking side of the fence. In an unexpected turn, the dogs simply laid down.

The hypothesis was that as the dogs learned from the first part of the experiment that there was nothing they could do to avoid the shocks, they gave up in the second part of the experiment. To prove this hypothesis the experimenters brought in a new set of animals and found that dogs with no history in the experiment would jump over the fence.

This condition was described as learned helplessness. A human or animal does not attempt to get out of a negative situation because the past has taught them that they are helpless.

10. Little Albert Experiment

Study conducted by: john b. watson and rosalie rayner.

Study Conducted in 1920 at Johns Hopkins University

The experiment began by placing a white rat in front of the infant, who initially had no fear of the animal. Watson then produced a loud sound by striking a steel bar with a hammer every time little Albert was presented with the rat. After several pairings (the noise and the presentation of the white rat), the boy began to cry and exhibit signs of fear every time the rat appeared in the room. Watson also created similar conditioned reflexes with other common animals and objects (rabbits, Santa beard, etc.) until Albert feared them all.

This study proved that classical conditioning works on humans. One of its most important implications is that adult fears are often connected to early childhood experiences.

11. Magical Number Seven

Study conducted by: george a. miller.

Study Conducted in 1956 at Princeton University

Experiment Details: Frequently referred to as “ Miller’s Law,” the Magical Number Seven experiment purports that the number of objects an average human can hold in working memory is 7 ± 2. This means that the human memory capacity typically includes strings of words or concepts ranging from 5-9. This information on the limits to the capacity for processing information became one of the most highly cited papers in psychology.

The Magical Number Seven Experiment was published in 1956 by cognitive psychologist George A. Miller of Princeton University’s Department of Psychology in Psychological Review . In the article, Miller discussed a concurrence between the limits of one-dimensional absolute judgment and the limits of short-term memory.

In a one-dimensional absolute-judgment task, a person is presented with a number of stimuli that vary on one dimension (such as 10 different tones varying only in pitch). The person responds to each stimulus with a corresponding response (learned before).

Performance is almost perfect up to five or six different stimuli but declines as the number of different stimuli is increased. This means that a human’s maximum performance on one-dimensional absolute judgment can be described as an information store with the maximum capacity of approximately 2 to 3 bits of information There is the ability to distinguish between four and eight alternatives.

12. Pavlov’s Dog Experiment

Study conducted by: ivan pavlov.

Study Conducted in the 1890s at the Military Medical Academy in St. Petersburg, Russia

Pavlov began with the simple idea that there are some things that a dog does not need to learn. He observed that dogs do not learn to salivate when they see food. This reflex is “hard wired” into the dog. This is an unconditioned response (a stimulus-response connection that required no learning).

Pavlov outlined that there are unconditioned responses in the animal by presenting a dog with a bowl of food and then measuring its salivary secretions. In the experiment, Pavlov used a bell as his neutral stimulus. Whenever he gave food to his dogs, he also rang a bell. After a number of repeats of this procedure, he tried the bell on its own. What he found was that the bell on its own now caused an increase in salivation. The dog had learned to associate the bell and the food. This learning created a new behavior. The dog salivated when he heard the bell. Because this response was learned (or conditioned), it is called a conditioned response. The neutral stimulus has become a conditioned stimulus.

This theory came to be known as classical conditioning.

13. Robbers Cave Experiment

Study conducted by: muzafer and carolyn sherif.

Study Conducted in 1954 at the University of Oklahoma

Experiment Details: This experiment, which studied group conflict, is considered by most to be outside the lines of what is considered ethically sound.

In 1954 researchers at the University of Oklahoma assigned 22 eleven- and twelve-year-old boys from similar backgrounds into two groups. The two groups were taken to separate areas of a summer camp facility where they were able to bond as social units. The groups were housed in separate cabins and neither group knew of the other’s existence for an entire week. The boys bonded with their cabin mates during that time. Once the two groups were allowed to have contact, they showed definite signs of prejudice and hostility toward each other even though they had only been given a very short time to develop their social group. To increase the conflict between the groups, the experimenters had them compete against each other in a series of activities. This created even more hostility and eventually the groups refused to eat in the same room. The final phase of the experiment involved turning the rival groups into friends. The fun activities the experimenters had planned like shooting firecrackers and watching movies did not initially work, so they created teamwork exercises where the two groups were forced to collaborate. At the end of the experiment, the boys decided to ride the same bus home, demonstrating that conflict can be resolved and prejudice overcome through cooperation.

Many critics have compared this study to Golding’s Lord of the Flies novel as a classic example of prejudice and conflict resolution.

14. Ross’ False Consensus Effect Study

Study conducted by: lee ross.

Study Conducted in 1977 at Stanford University

Experiment Details: In 1977, a social psychology professor at Stanford University named Lee Ross conducted an experiment that, in lay terms, focuses on how people can incorrectly conclude that others think the same way they do, or form a “false consensus” about the beliefs and preferences of others. Ross conducted the study in order to outline how the “false consensus effect” functions in humans.

Featured Programs

In the first part of the study, participants were asked to read about situations in which a conflict occurred and then were told two alternative ways of responding to the situation. They were asked to do three things:

- Guess which option other people would choose

- Say which option they themselves would choose

- Describe the attributes of the person who would likely choose each of the two options

What the study showed was that most of the subjects believed that other people would do the same as them, regardless of which of the two responses they actually chose themselves. This phenomenon is referred to as the false consensus effect, where an individual thinks that other people think the same way they do when they may not. The second observation coming from this important study is that when participants were asked to describe the attributes of the people who will likely make the choice opposite of their own, they made bold and sometimes negative predictions about the personalities of those who did not share their choice.

15. The Schacter and Singer Experiment on Emotion

Study conducted by: stanley schachter and jerome e. singer.

Study Conducted in 1962 at Columbia University

Experiment Details: In 1962 Schachter and Singer conducted a ground breaking experiment to prove their theory of emotion.

In the study, a group of 184 male participants were injected with epinephrine, a hormone that induces arousal including increased heartbeat, trembling, and rapid breathing. The research participants were told that they were being injected with a new medication to test their eyesight. The first group of participants was informed the possible side effects that the injection might cause while the second group of participants were not. The participants were then placed in a room with someone they thought was another participant, but was actually a confederate in the experiment. The confederate acted in one of two ways: euphoric or angry. Participants who had not been informed about the effects of the injection were more likely to feel either happier or angrier than those who had been informed.

What Schachter and Singer were trying to understand was the ways in which cognition or thoughts influence human emotion. Their study illustrates the importance of how people interpret their physiological states, which form an important component of your emotions. Though their cognitive theory of emotional arousal dominated the field for two decades, it has been criticized for two main reasons: the size of the effect seen in the experiment was not that significant and other researchers had difficulties repeating the experiment.

16. Selective Attention / Invisible Gorilla Experiment

Study conducted by: daniel simons and christopher chabris.

Study Conducted in 1999 at Harvard University

Experiment Details: In 1999 Simons and Chabris conducted their famous awareness test at Harvard University.

Participants in the study were asked to watch a video and count how many passes occurred between basketball players on the white team. The video moves at a moderate pace and keeping track of the passes is a relatively easy task. What most people fail to notice amidst their counting is that in the middle of the test, a man in a gorilla suit walked onto the court and stood in the center before walking off-screen.

The study found that the majority of the subjects did not notice the gorilla at all, proving that humans often overestimate their ability to effectively multi-task. What the study set out to prove is that when people are asked to attend to one task, they focus so strongly on that element that they may miss other important details.

17. Stanford Prison Study

Study conducted by philip zimbardo.

Study Conducted in 1971 at Stanford University

The Stanford Prison Experiment was designed to study behavior of “normal” individuals when assigned a role of prisoner or guard. College students were recruited to participate. They were assigned roles of “guard” or “inmate.” Zimbardo played the role of the warden. The basement of the psychology building was the set of the prison. Great care was taken to make it look and feel as realistic as possible.

The prison guards were told to run a prison for two weeks. They were told not to physically harm any of the inmates during the study. After a few days, the prison guards became very abusive verbally towards the inmates. Many of the prisoners became submissive to those in authority roles. The Stanford Prison Experiment inevitably had to be cancelled because some of the participants displayed troubling signs of breaking down mentally.

Although the experiment was conducted very unethically, many psychologists believe that the findings showed how much human behavior is situational. People will conform to certain roles if the conditions are right. The Stanford Prison Experiment remains one of the most famous psychology experiments of all time.

18. Stanley Milgram Experiment

Study conducted by stanley milgram.

Study Conducted in 1961 at Stanford University

Experiment Details: This 1961 study was conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram. It was designed to measure people’s willingness to obey authority figures when instructed to perform acts that conflicted with their morals. The study was based on the premise that humans will inherently take direction from authority figures from very early in life.

Participants were told they were participating in a study on memory. They were asked to watch another person (an actor) do a memory test. They were instructed to press a button that gave an electric shock each time the person got a wrong answer. (The actor did not actually receive the shocks, but pretended they did).

Participants were told to play the role of “teacher” and administer electric shocks to “the learner,” every time they answered a question incorrectly. The experimenters asked the participants to keep increasing the shocks. Most of them obeyed even though the individual completing the memory test appeared to be in great pain. Despite these protests, many participants continued the experiment when the authority figure urged them to. They increased the voltage after each wrong answer until some eventually administered what would be lethal electric shocks.

This experiment showed that humans are conditioned to obey authority and will usually do so even if it goes against their natural morals or common sense.

19. Surrogate Mother Experiment

Study conducted by: harry harlow.

Study Conducted from 1957-1963 at the University of Wisconsin

Experiment Details: In a series of controversial experiments during the late 1950s and early 1960s, Harry Harlow studied the importance of a mother’s love for healthy childhood development.

In order to do this he separated infant rhesus monkeys from their mothers a few hours after birth and left them to be raised by two “surrogate mothers.” One of the surrogates was made of wire with an attached bottle for food. The other was made of soft terrycloth but lacked food. The researcher found that the baby monkeys spent much more time with the cloth mother than the wire mother, thereby proving that affection plays a greater role than sustenance when it comes to childhood development. They also found that the monkeys that spent more time cuddling the soft mother grew up to healthier.

This experiment showed that love, as demonstrated by physical body contact, is a more important aspect of the parent-child bond than the provision of basic needs. These findings also had implications in the attachment between fathers and their infants when the mother is the source of nourishment.

20. The Good Samaritan Experiment

Study conducted by: john darley and daniel batson.

Study Conducted in 1973 at The Princeton Theological Seminary (Researchers were from Princeton University)

Experiment Details: In 1973, an experiment was created by John Darley and Daniel Batson, to investigate the potential causes that underlie altruistic behavior. The researchers set out three hypotheses they wanted to test:

- People thinking about religion and higher principles would be no more inclined to show helping behavior than laymen.

- People in a rush would be much less likely to show helping behavior.

- People who are religious for personal gain would be less likely to help than people who are religious because they want to gain some spiritual and personal insights into the meaning of life.

Student participants were given some religious teaching and instruction. They were then were told to travel from one building to the next. Between the two buildings was a man lying injured and appearing to be in dire need of assistance. The first variable being tested was the degree of urgency impressed upon the subjects, with some being told not to rush and others being informed that speed was of the essence.

The results of the experiment were intriguing, with the haste of the subject proving to be the overriding factor. When the subject was in no hurry, nearly two-thirds of people stopped to lend assistance. When the subject was in a rush, this dropped to one in ten.

People who were on the way to deliver a speech about helping others were nearly twice as likely to help as those delivering other sermons,. This showed that the thoughts of the individual were a factor in determining helping behavior. Religious beliefs did not appear to make much difference on the results. Being religious for personal gain, or as part of a spiritual quest, did not appear to make much of an impact on the amount of helping behavior shown.

21. The Halo Effect Experiment

Study conducted by: richard e. nisbett and timothy decamp wilson.

Study Conducted in 1977 at the University of Michigan

Experiment Details: The Halo Effect states that people generally assume that people who are physically attractive are more likely to:

- be intelligent

- be friendly

- display good judgment

To prove their theory, Nisbett and DeCamp Wilson created a study to prove that people have little awareness of the nature of the Halo Effect. They’re not aware that it influences:

- their personal judgments

- the production of a more complex social behavior

In the experiment, college students were the research participants. They were asked to evaluate a psychology instructor as they view him in a videotaped interview. The students were randomly assigned to one of two groups. Each group was shown one of two different interviews with the same instructor. The instructor is a native French-speaking Belgian who spoke English with a noticeable accent. In the first video, the instructor presented himself as someone:

- respectful of his students’ intelligence and motives

- flexible in his approach to teaching

- enthusiastic about his subject matter

In the second interview, he presented himself as much more unlikable. He was cold and distrustful toward the students and was quite rigid in his teaching style.

After watching the videos, the subjects were asked to rate the lecturer on:

- physical appearance

His mannerisms and accent were kept the same in both versions of videos. The subjects were asked to rate the professor on an 8-point scale ranging from “like extremely” to “dislike extremely.” Subjects were also told that the researchers were interested in knowing “how much their liking for the teacher influenced the ratings they just made.” Other subjects were asked to identify how much the characteristics they just rated influenced their liking of the teacher.

After responding to the questionnaire, the respondents were puzzled about their reactions to the videotapes and to the questionnaire items. The students had no idea why they gave one lecturer higher ratings. Most said that how much they liked the lecturer had not affected their evaluation of his individual characteristics at all.

The interesting thing about this study is that people can understand the phenomenon, but they are unaware when it is occurring. Without realizing it, humans make judgments. Even when it is pointed out, they may still deny that it is a product of the halo effect phenomenon.

22. The Marshmallow Test

Study conducted by: walter mischel.

Study Conducted in 1972 at Stanford University

In his 1972 Marshmallow Experiment, children ages four to six were taken into a room where a marshmallow was placed in front of them on a table. Before leaving each of the children alone in the room, the experimenter informed them that they would receive a second marshmallow if the first one was still on the table after they returned in 15 minutes. The examiner recorded how long each child resisted eating the marshmallow and noted whether it correlated with the child’s success in adulthood. A small number of the 600 children ate the marshmallow immediately and one-third delayed gratification long enough to receive the second marshmallow.

In follow-up studies, Mischel found that those who deferred gratification were significantly more competent and received higher SAT scores than their peers. This characteristic likely remains with a person for life. While this study seems simplistic, the findings outline some of the foundational differences in individual traits that can predict success.

23. The Monster Study

Study conducted by: wendell johnson.

Study Conducted in 1939 at the University of Iowa

Experiment Details: The Monster Study received this negative title due to the unethical methods that were used to determine the effects of positive and negative speech therapy on children.

Wendell Johnson of the University of Iowa selected 22 orphaned children, some with stutters and some without. The children were in two groups. The group of children with stutters was placed in positive speech therapy, where they were praised for their fluency. The non-stutterers were placed in negative speech therapy, where they were disparaged for every mistake in grammar that they made.

As a result of the experiment, some of the children who received negative speech therapy suffered psychological effects and retained speech problems for the rest of their lives. They were examples of the significance of positive reinforcement in education.

The initial goal of the study was to investigate positive and negative speech therapy. However, the implication spanned much further into methods of teaching for young children.

24. Violinist at the Metro Experiment

Study conducted by: staff at the washington post.

Study Conducted in 2007 at a Washington D.C. Metro Train Station

During the study, pedestrians rushed by without realizing that the musician playing at the entrance to the metro stop was Grammy-winning musician, Joshua Bell. Two days before playing in the subway, he sold out at a theater in Boston where the seats average $100. He played one of the most intricate pieces ever written with a violin worth 3.5 million dollars. In the 45 minutes the musician played his violin, only 6 people stopped and stayed for a while. Around 20 gave him money, but continued to walk their normal pace. He collected $32.

The study and the subsequent article organized by the Washington Post was part of a social experiment looking at:

- the priorities of people

Gene Weingarten wrote about the social experiment: “In a banal setting at an inconvenient time, would beauty transcend?” Later he won a Pulitzer Prize for his story. Some of the questions the article addresses are:

- Do we perceive beauty?

- Do we stop to appreciate it?

- Do we recognize the talent in an unexpected context?

As it turns out, many of us are not nearly as perceptive to our environment as we might like to think.

25. Visual Cliff Experiment

Study conducted by: eleanor gibson and richard walk.

Study Conducted in 1959 at Cornell University

Experiment Details: In 1959, psychologists Eleanor Gibson and Richard Walk set out to study depth perception in infants. They wanted to know if depth perception is a learned behavior or if it is something that we are born with. To study this, Gibson and Walk conducted the visual cliff experiment.

They studied 36 infants between the ages of six and 14 months, all of whom could crawl. The infants were placed one at a time on a visual cliff. A visual cliff was created using a large glass table that was raised about a foot off the floor. Half of the glass table had a checker pattern underneath in order to create the appearance of a ‘shallow side.’

In order to create a ‘deep side,’ a checker pattern was created on the floor; this side is the visual cliff. The placement of the checker pattern on the floor creates the illusion of a sudden drop-off. Researchers placed a foot-wide centerboard between the shallow side and the deep side. Gibson and Walk found the following:

- Nine of the infants did not move off the centerboard.

- All of the 27 infants who did move crossed into the shallow side when their mothers called them from the shallow side.

- Three of the infants crawled off the visual cliff toward their mother when called from the deep side.

- When called from the deep side, the remaining 24 children either crawled to the shallow side or cried because they could not cross the visual cliff and make it to their mother.

What this study helped demonstrate is that depth perception is likely an inborn train in humans.

Among these experiments and psychological tests, we see boundaries pushed and theories taking on a life of their own. It is through the endless stream of psychological experimentation that we can see simple hypotheses become guiding theories for those in this field. The greater field of psychology became a formal field of experimental study in 1879, when Wilhelm Wundt established the first laboratory dedicated solely to psychological research in Leipzig, Germany. Wundt was the first person to refer to himself as a psychologist. Since 1879, psychology has grown into a massive collection of:

- methods of practice

It’s also a specialty area in the field of healthcare. None of this would have been possible without these and many other important psychological experiments that have stood the test of time.

- 20 Most Unethical Experiments in Psychology

- What Careers are in Experimental Psychology?

- 10 Things to Know About the Psychology of Psychotherapy

About Education: Psychology

Explorable.com

Mental Floss.com

About the Author

After earning a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology from Rutgers University and then a Master of Science in Clinical and Forensic Psychology from Drexel University, Kristen began a career as a therapist at two prisons in Philadelphia. At the same time she volunteered as a rape crisis counselor, also in Philadelphia. After a few years in the field she accepted a teaching position at a local college where she currently teaches online psychology courses. Kristen began writing in college and still enjoys her work as a writer, editor, professor and mother.

- 5 Best Online Ph.D. Marriage and Family Counseling Programs

- Top 5 Online Doctorate in Educational Psychology

- 5 Best Online Ph.D. in Industrial and Organizational Psychology Programs

- Top 10 Online Master’s in Forensic Psychology

- 10 Most Affordable Counseling Psychology Online Programs

- 10 Most Affordable Online Industrial Organizational Psychology Programs

- 10 Most Affordable Online Developmental Psychology Online Programs

- 15 Most Affordable Online Sport Psychology Programs

- 10 Most Affordable School Psychology Online Degree Programs

- Top 50 Online Psychology Master’s Degree Programs

- Top 25 Online Master’s in Educational Psychology

- Top 25 Online Master’s in Industrial/Organizational Psychology

- Top 10 Most Affordable Online Master’s in Clinical Psychology Degree Programs

- Top 6 Most Affordable Online PhD/PsyD Programs in Clinical Psychology

- 50 Great Small Colleges for a Bachelor’s in Psychology

- 50 Most Innovative University Psychology Departments

- The 30 Most Influential Cognitive Psychologists Alive Today

- Top 30 Affordable Online Psychology Degree Programs

- 30 Most Influential Neuroscientists

- Top 40 Websites for Psychology Students and Professionals

- Top 30 Psychology Blogs

- 25 Celebrities With Animal Phobias

- Your Phobias Illustrated (Infographic)

- 15 Inspiring TED Talks on Overcoming Challenges

- 10 Fascinating Facts About the Psychology of Color

- 15 Scariest Mental Disorders of All Time

- 15 Things to Know About Mental Disorders in Animals

- 13 Most Deranged Serial Killers of All Time

Site Information

- About Online Psychology Degree Guide

The Top 10 Cases In The History Of Psychology

- By MS Broudy

- Published October 11, 2019

- Last Updated November 13, 2023

- Read Time 8 mins

Posted October 2019 by M.S. Broudy, B.A. English, B.A. Psychology; M.A. Social Psychology; Ph.D. Psychology; 6 updates since. Reading time: 8 min. Reading level: Grade 8+. Questions on the top cases in psychology history? Email Toni at: [email protected] .

Nothing captivates us more than the human mind. We are constantly attempting to understand the origins of behavior and the intricate workings of the brain. Throughout our history, there have been particular people whose story is so astonishing that they have remained a source of constant curiosity and learning. Here are 10 extraordinary cases from the realm of psychology that continue to fascinate.

Phineas Gage

In 1848, Phineas Gage was working as a foreman on a railroad crew in Vermont. While he was using a tamping iron to pack some explosive powder, the powder exploded, driving the iron through his head. Amazingly, he survived but friends noted that he no longer acted like the same person. He had limited intellectual ability and there were acute changes in his personality. He spewed profanity, was highly impulsive and showed little regard for other people. The change in Gage’s personality is consistent with damage to the orbitofrontal cortex of his frontal lobe, which impacts affect and emotion. It was one of the first cases to show a link between the brain and personality, in addition to cognitive functions.

Louis Victor Leborgne (Tan)

Similar to what H.M. did for memory, the case of Louis Victor Leborgne made significant contributions to the study of language production and comprehension. At age 30, he was admitted to a Paris hospital after losing his ability to speak. He could only say the word “tan” and was later called by that name in recalling his case. Despite his inability to speak, his cognitive functions appeared intact. Leborgne could comprehend what was being said to him and retained his intelligence. In 1861 he met physician Paul Broca after developing Gangrene. Upon Leborgne’s death, Broca examined his brain and found a lesion in his left frontal lobe. Due to Leborgne’s language, Broca postulated that this area of the brain was responsible for speech production. This area of the brain has become known as Broca’s area (Leborgne’s condition is called Broca’s aphasia) and is one of the most significant findings in the neurological study of speech.

Bertha Pappenheim (Anna O)

Bertha Pappenheim is thought to be the first person to undergo psychotherapy. Although her case is usually associated with the work of Sigmund Freud, it was his colleague, Joseph Breuer, who was initially her treating physician. Pappenheim suffered from “hysteria” as well as hallucinations and various ailments. Despite some records noting that she was cured by talk therapy, certain historians report that her improvements were temporary and she was never cured. Although Freud never met Pappenheim, he often publicly referred to Anna O. as the first recipient of the “talking cure” and said it was her case that was responsible for the birth of psychoanalysis.

Little Albert

In 1920, psychologist John Watson and his future wife, Rosalind Rayner, experimented on an infant to prove the theory of classical conditioning. They called the baby “Albert B.” And the case became known as the “Little Albert” experiment. Watson and Rayner paired a white rat and other objects with a loud noise to condition a fear response in Albert. The experiment showed that people can be conditioned to have emotional responses to a previously neutral object and that the response can be generalized to other stimuli. One of the most important conclusions drawn from the experiment is that early childhood experiences can influence later emotional development. Of course, scaring a baby for scientific purposes is now seen as highly unethical. The Little Albert experiment has become known as much for its lack of ethical boundaries as it has for its contributions to behavioral psychology.

Henry Gustav Molaison (H.M.)

In 1955, Henry Gustav Molaison (known frequently in the literature as H.M.) had brain surgery to cure himself of debilitating epilepsy. The surgery involved removing both halves of the hippocampus. Although the operation did relieve most of his seizures, it had an unintended effect: he could no longer form short-term memories. H.M. also suffered some retrograde amnesia, losing memories for 11 years before the operation. Otherwise, his long-term memory was intact. Because the surgery was so precise, it perfectly exhibited the role of the hippocampus in memory creation. H.M. was studied for the rest of his life and, upon his death, donated his brain to science. It would not be a stretch to say that he contributed more to the study of memory than any one subject.

Kitty Genovese

In 1964, Kitty Genovese was murdered on the street in Queens, New York. At the time, it was reported that a multitude of people saw her get killed and did nothing about it. Ever since, this event has been promoted as a prime example of the Bystander Effect: the more people that witness an event, the less likely they are to do something about it. Later investigations found that there were some discrepancies in the reporting and a couple of people at the scene may have indeed tried to report the crime. Although the basic principle of the Bystander Effect has held up over the past 50 years, the real legacy of the case is the research and activism it has inspired. The Genovese case has spurred an immense amount of psychological study across different areas, including forensic psychology and prosocial behavior. Additionally, it impacted the creation of victim services, Good Samaritan laws, and the 911 emergency call system.

Chris Costner Sizemore

You may not know the name Chris Costner Sizemore but you may have heard about her life in the movie “The Three Faces of Eve”. Sizemore’s case is one of the first and most famous involving multiple personalities, which is now known as Dissociative Identity Disorder. Until the publicity of her case, the possibility that people could have multiple personalities was, for most, a fantastical notion rather than a reality. In addition, Sizemore’s case shines a light on severe psychological consequences of early childhood trauma. Sizemore believes her different personalities developed as a way to cope with certain disturbing experiences she had when she was younger. After three of her personalities were publicized in the movie, she says she continued to experience other personalities throughout her life.

Genie was brought up in a house of extreme abuse and neglect. For most of her first 13 years, she was strapped onto a chair in a single room with almost no human interaction. When Genie was found, she possessed the development level of a one-year-old. She worked with numerous professionals and learned to develop motor skills and how to comprehend language. She also obtained a decent vocabulary, but could not catch up on her grammatical skills. It seemed Genie had missed a critical period of language development, proving you cannot learn grammatical language later in life. In addition to speech development, the case of Genie exhibits the effects of severe abuse and neglect. It also illustrates the great resiliency of human beings to overcome deprivation.

Kim Peek was the inspiration for Dustin Hoffman’s character in the movie Rain Man. Although many people believe he was autistic, he was a non-autistic savant, with exceptional mental abilities. His memory and capacity to perform certain mathematical calculations were nothing short of astounding. An MRI exam showed that Peek was lacking the corpus callosum, the part of the brain that connects the two hemispheres. It is thought that this brain abnormality contributed to his special abilities. Despite his uniqueness, his brain was not his biggest contribution to psychology. Ironically, the misconception of his autism helped to raise the profile of the little-known disorder into the mainstream.

David Reimer (John/Joan Case)

David Reimer was born a boy but his penis was castrated by accident during a circumcision procedure. Instead of trying to reconstruct his penis, it was recommended by a doctor, John Money, that he be brought up as a girl. Money believed that gender was a choice and could override any natural inclination. As a result, when he was 17 months old, David underwent surgery and became Brenda Reimer. Despite Money’s assurances that the process was a success, David’s parents could tell that he was not happy as a girl. Eventually, when he was 14, his parents told him he was born a boy and David elected to reverse the gender reassignment process to become male again. David’s story has become a cautionary tale. He committed suicide at age 38. He spent much of his life campaigning against gender assignment surgery being forced upon children without consent. His case is one of the most high profile indications that gender identity is not a choice, attempting to undo the damage caused by John Money’s false assertions.

More Articles of Interest:

- How Is Technology Changing The Study Of Psychology?

- The 10 Most Important People In The History Of Psychology

- 10 Key Moments in the History of Psychology

- WWII And Its Impact On Psychology

Trending now

404 Not found

Psychology Case Study Examples: A Deep Dive into Real-life Scenarios

Peeling back the layers of the human mind is no easy task, but psychology case studies can help us do just that. Through these detailed analyses, we’re able to gain a deeper understanding of human behavior, emotions, and cognitive processes. I’ve always found it fascinating how a single person’s experience can shed light on broader psychological principles.

Over the years, psychologists have conducted numerous case studies—each with their own unique insights and implications. These investigations range from Phineas Gage’s accidental lobotomy to Genie Wiley’s tragic tale of isolation. Such examples not only enlighten us about specific disorders or occurrences but also continue to shape our overall understanding of psychology .

As we delve into some noteworthy examples , I assure you’ll appreciate how varied and intricate the field of psychology truly is. Whether you’re a budding psychologist or simply an eager learner, brace yourself for an intriguing exploration into the intricacies of the human psyche.

Understanding Psychology Case Studies

Diving headfirst into the world of psychology, it’s easy to come upon a valuable tool used by psychologists and researchers alike – case studies. I’m here to shed some light on these fascinating tools.

Psychology case studies, for those unfamiliar with them, are in-depth investigations carried out to gain a profound understanding of the subject – whether it’s an individual, group or phenomenon. They’re powerful because they provide detailed insights that other research methods might miss.

Let me share a few examples to clarify this concept further:

- One notable example is Freud’s study on Little Hans. This case study explored a 5-year-old boy’s fear of horses and related it back to Freud’s theories about psychosexual stages.

- Another classic example is Genie Wiley (a pseudonym), a feral child who was subjected to severe social isolation during her early years. Her heartbreaking story provided invaluable insights into language acquisition and critical periods in development.

You see, what sets psychology case studies apart is their focus on the ‘why’ and ‘how’. While surveys or experiments might tell us ‘what’, they often don’t dig deep enough into the inner workings behind human behavior.

It’s important though not to take these psychology case studies at face value. As enlightening as they can be, we must remember that they usually focus on one specific instance or individual. Thus, generalizing findings from single-case studies should be done cautiously.

To illustrate my point using numbers: let’s say we have 1 million people suffering from condition X worldwide; if only 20 unique cases have been studied so far (which would be quite typical for rare conditions), then our understanding is based on just 0.002% of the total cases! That’s why multiple sources and types of research are vital when trying to understand complex psychological phenomena fully.

In the grand scheme of things, psychology case studies are just one piece of the puzzle – albeit an essential one. They provide rich, detailed data that can form the foundation for further research and understanding. As we delve deeper into this fascinating field, it’s crucial to appreciate all the tools at our disposal – from surveys and experiments to these insightful case studies.

Importance of Case Studies in Psychology

I’ve always been fascinated by the human mind, and if you’re here, I bet you are too. Let’s dive right into why case studies play such a pivotal role in psychology.

One of the key reasons they matter so much is because they provide detailed insights into specific psychological phenomena. Unlike other research methods that might use large samples but only offer surface-level findings, case studies allow us to study complex behaviors, disorders, and even treatments at an intimate level. They often serve as a catalyst for new theories or help refine existing ones.

To illustrate this point, let’s look at one of psychology’s most famous case studies – Phineas Gage. He was a railroad construction foreman who survived a severe brain injury when an iron rod shot through his skull during an explosion in 1848. The dramatic personality changes he experienced after his accident led to significant advancements in our understanding of the brain’s role in personality and behavior.

Moreover, it’s worth noting that some rare conditions can only be studied through individual cases due to their uncommon nature. For instance, consider Genie Wiley – a girl discovered at age 13 having spent most of her life locked away from society by her parents. Her tragic story gave psychologists valuable insights into language acquisition and critical periods for learning.

Finally yet importantly, case studies also have practical applications for clinicians and therapists. Studying real-life examples can inform treatment plans and provide guidance on how theoretical concepts might apply to actual client situations.

- Detailed insights: Case studies offer comprehensive views on specific psychological phenomena.

- Catalyst for new theories: Real-life scenarios help shape our understanding of psychology .

- Study rare conditions: Unique cases can offer invaluable lessons about uncommon disorders.

- Practical applications: Clinicians benefit from studying real-world examples.

In short (but without wrapping up), it’s clear that case studies hold immense value within psychology – they illuminate what textbooks often can’t, offering a more nuanced understanding of human behavior.

Different Types of Psychology Case Studies

Diving headfirst into the world of psychology, I can’t help but be fascinated by the myriad types of case studies that revolve around this subject. Let’s take a closer look at some of them.

Firstly, we’ve got what’s known as ‘Explanatory Case Studies’. These are often used when a researcher wants to clarify complex phenomena or concepts. For example, a psychologist might use an explanatory case study to explore the reasons behind aggressive behavior in children.

Second on our list are ‘Exploratory Case Studies’, typically utilized when new and unexplored areas of research come up. They’re like pioneers; they pave the way for future studies. In psychological terms, exploratory case studies could be conducted to investigate emerging mental health conditions or under-researched therapeutic approaches.

Next up are ‘Descriptive Case Studies’. As the name suggests, these focus on depicting comprehensive and detailed profiles about a particular individual, group, or event within its natural context. A well-known example would be Sigmund Freud’s analysis of “Anna O”, which provided unique insights into hysteria.

Then there are ‘Intrinsic Case Studies’, which delve deep into one specific case because it is intrinsically interesting or unique in some way. It’s sorta like shining a spotlight onto an exceptional phenomenon. An instance would be studying savants—individuals with extraordinary abilities despite significant mental disabilities.

Lastly, we have ‘Instrumental Case Studies’. These aren’t focused on understanding a particular case per se but use it as an instrument to understand something else altogether—a bit like using one puzzle piece to make sense of the whole picture!

So there you have it! From explanatory to instrumental, each type serves its own unique purpose and adds another intriguing layer to our understanding of human behavior and cognition.

Exploring Real-Life Psychology Case Study Examples

Let’s roll up our sleeves and delve into some real-life psychology case study examples. By digging deep, we can glean valuable insights from these studies that have significantly contributed to our understanding of human behavior and mental processes.

First off, let me share the fascinating case of Phineas Gage. This gentleman was a 19th-century railroad construction foreman who survived an accident where a large iron rod was accidentally driven through his skull, damaging his frontal lobes. Astonishingly, he could walk and talk immediately after the accident but underwent dramatic personality changes, becoming impulsive and irresponsible. This case is often referenced in discussions about brain injury and personality change.