Essay on Digital Literacy

Students are often asked to write an essay on Digital Literacy in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Digital Literacy

Understanding digital literacy.

Digital Literacy is knowing how to use digital devices like computers, tablets, and smartphones. It’s about understanding the internet and social media. It’s important because we live in a digital world. We use digital tools for school, work, and fun.

Why is Digital Literacy Important?

Digital Literacy helps us learn and communicate. It helps us find information quickly and easily. It can also keep us safe online. We need to know how to protect our personal information and avoid dangerous sites.

How Can We Improve Digital Literacy?

We can improve Digital Literacy by learning. Schools and libraries often have classes. We can also learn from friends or family. Practice is important too. The more we use digital tools, the better we get.

Challenges of Digital Literacy

Sometimes, Digital Literacy can be hard. Not everyone has access to digital tools. Some people might find them difficult to use. But with time and patience, we can overcome these challenges.

In conclusion, Digital Literacy is a vital skill in today’s world. It helps us learn, communicate, and stay safe online. Despite challenges, we can improve our skills with learning and practice.

250 Words Essay on Digital Literacy

What is digital literacy.

Digital literacy is the ability to use digital devices like computers, smartphones, and tablets. It’s about knowing how to search for information online, use social media, send emails, and protect your personal information. It’s a bit like learning to read and write, but with technology.

In today’s world, technology is everywhere. We use it for school, work, and even fun. Being digitally literate helps you do all these things easily. It also helps you stay safe online. For example, knowing how to spot a scam email can protect you from losing money or personal information.

Parts of Digital Literacy

Digital literacy has many parts. One part is technical skills, like knowing how to use a keyboard or mouse. Another part is understanding how to find and use information online. This could mean using a search engine, reading a blog post, or watching a video tutorial.

Learning Digital Literacy

You can learn digital literacy at school, at home, or even by yourself. Many schools teach students how to use technology safely and effectively. Parents can also help by showing their kids how to use devices and the internet responsibly.

The Future of Digital Literacy

As technology keeps changing, digital literacy will also change. It will be more important than ever to keep learning new skills. This will help us keep up with the digital world and make the most of the opportunities it offers.

In conclusion, digital literacy is a key skill for the modern world. It helps us use technology safely and effectively, and it will only become more important in the future.

500 Words Essay on Digital Literacy

Digital literacy is the ability to use digital technology, such as computers, smartphones, and the internet. It includes knowing how to find information online, how to use social media, and how to stay safe on the internet. Just like we need to know how to read and write in school, we also need to learn digital literacy in today’s world.

Digital literacy is important because we use technology every day. We use it for schoolwork, to talk to our friends, and even for fun. If we do not know how to use technology safely and effectively, we could get into trouble. For example, we might accidentally share personal information online, which can be dangerous. Or we might have trouble completing school assignments if we do not know how to use the internet for research.

Digital literacy is not just about knowing how to use a computer. It has many parts. Here are a few:

1. Technical skills: This includes knowing how to use different devices, like laptops, tablets, and smartphones. It also includes knowing how to use different types of software, like word processors and web browsers.

2. Information skills: This involves knowing how to find and evaluate information online. Not everything on the internet is true, so it is important to know how to tell the difference between reliable and unreliable sources.

3. Safety skills: This includes knowing how to protect yourself online. This means understanding how to create strong passwords, how to avoid scams, and how to protect your personal information.

Improving Digital Literacy

There are many ways to improve digital literacy. Schools often teach students how to use technology and the internet. There are also many online resources that can help. These include tutorials, videos, and websites that explain how to use different technologies. It is important to practice these skills regularly, just like any other skill.

In conclusion, digital literacy is a vital skill in today’s world. It involves understanding how to use technology, how to find and evaluate information online, and how to stay safe on the internet. By improving our digital literacy, we can become more confident and capable users of technology.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Inclusivity and Plurality are the Hallmarks of a Peaceful Society

- Essay on Discipline in College

- Essay on Who is a Good Citizen

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Open access

- Published: 08 June 2022

A systematic review on digital literacy

- Hasan Tinmaz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4310-0848 1 ,

- Yoo-Taek Lee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1913-9059 2 ,

- Mina Fanea-Ivanovici ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2921-2990 3 &

- Hasnan Baber ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8951-3501 4

Smart Learning Environments volume 9 , Article number: 21 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

43k Accesses

35 Citations

10 Altmetric

Metrics details

The purpose of this study is to discover the main themes and categories of the research studies regarding digital literacy. To serve this purpose, the databases of WoS/Clarivate Analytics, Proquest Central, Emerald Management Journals, Jstor Business College Collections and Scopus/Elsevier were searched with four keyword-combinations and final forty-three articles were included in the dataset. The researchers applied a systematic literature review method to the dataset. The preliminary findings demonstrated that there is a growing prevalence of digital literacy articles starting from the year 2013. The dominant research methodology of the reviewed articles is qualitative. The four major themes revealed from the qualitative content analysis are: digital literacy, digital competencies, digital skills and digital thinking. Under each theme, the categories and their frequencies are analysed. Recommendations for further research and for real life implementations are generated.

Introduction

The extant literature on digital literacy, skills and competencies is rich in definitions and classifications, but there is still no consensus on the larger themes and subsumed themes categories. (Heitin, 2016 ). To exemplify, existing inventories of Internet skills suffer from ‘incompleteness and over-simplification, conceptual ambiguity’ (van Deursen et al., 2015 ), and Internet skills are only a part of digital skills. While there is already a plethora of research in this field, this research paper hereby aims to provide a general framework of digital areas and themes that can best describe digital (cap)abilities in the novel context of Industry 4.0 and the accelerated pandemic-triggered digitalisation. The areas and themes can represent the starting point for drafting a contemporary digital literacy framework.

Sousa and Rocha ( 2019 ) explained that there is a stake of digital skills for disruptive digital business, and they connect it to the latest developments, such as the Internet of Things (IoT), cloud technology, big data, artificial intelligence, and robotics. The topic is even more important given the large disparities in digital literacy across regions (Tinmaz et al., 2022 ). More precisely, digital inequalities encompass skills, along with access, usage and self-perceptions. These inequalities need to be addressed, as they are credited with a ‘potential to shape life chances in multiple ways’ (Robinson et al., 2015 ), e.g., academic performance, labour market competitiveness, health, civic and political participation. Steps have been successfully taken to address physical access gaps, but skills gaps are still looming (Van Deursen & Van Dijk, 2010a ). Moreover, digital inequalities have grown larger due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and they influenced the very state of health of the most vulnerable categories of population or their employability in a time when digital skills are required (Baber et al., 2022 ; Beaunoyer, Dupéré & Guitton, 2020 ).

The systematic review the researchers propose is a useful updated instrument of classification and inventory for digital literacy. Considering the latest developments in the economy and in line with current digitalisation needs, digitally literate population may assist policymakers in various fields, e.g., education, administration, healthcare system, and managers of companies and other concerned organisations that need to stay competitive and to employ competitive workforce. Therefore, it is indispensably vital to comprehend the big picture of digital literacy related research.

Literature review

Since the advent of Digital Literacy, scholars have been concerned with identifying and classifying the various (cap)abilities related to its operation. Using the most cited academic papers in this stream of research, several classifications of digital-related literacies, competencies, and skills emerged.

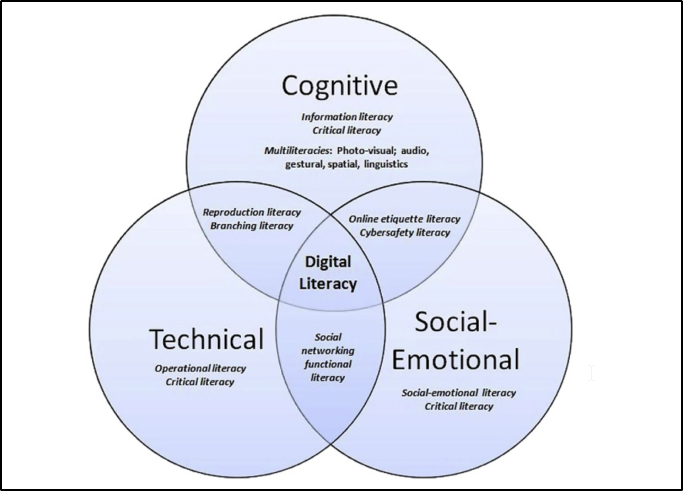

Digital literacies

Digital literacy, which is one of the challenges of integration of technology in academic courses (Blau, Shamir-Inbal & Avdiel, 2020 ), has been defined in the current literature as the competencies and skills required for navigating a fragmented and complex information ecosystem (Eshet, 2004 ). A ‘Digital Literacy Framework’ was designed by Eshet-Alkalai ( 2012 ), comprising six categories: (a) photo-visual thinking (understanding and using visual information); (b) real-time thinking (simultaneously processing a variety of stimuli); (c) information thinking (evaluating and combining information from multiple digital sources); (d) branching thinking (navigating in non-linear hyper-media environments); (e) reproduction thinking (creating outcomes using technological tools by designing new content or remixing existing digital content); (f) social-emotional thinking (understanding and applying cyberspace rules). According to Heitin ( 2016 ), digital literacy groups the following clusters: (a) finding and consuming digital content; (b) creating digital content; (c) communicating or sharing digital content. Hence, the literature describes the digital literacy in many ways by associating a set of various technical and non-technical elements.

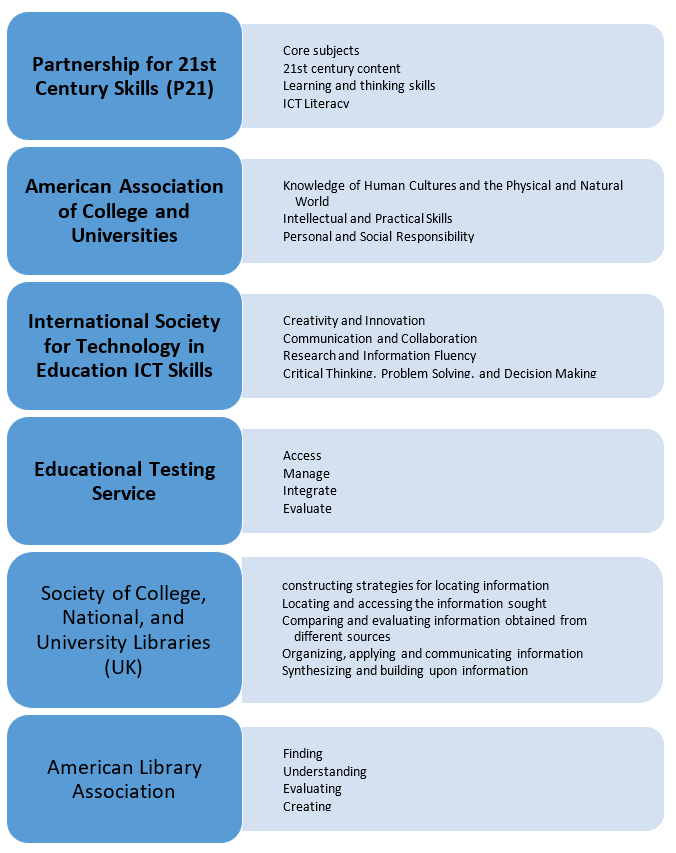

- Digital competencies

The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens (DigComp 2.1.), the most recent framework proposed by the European Union, which is currently under review and undergoing an updating process, contains five competency areas: (a) information and data literacy, (b) communication and collaboration, (c) digital content creation, (d) safety, and (e) problem solving (Carretero, Vuorikari & Punie, 2017 ). Digital competency had previously been described in a technical fashion by Ferrari ( 2012 ) as a set comprising information skills, communication skills, content creation skills, safety skills, and problem-solving skills, which later outlined the areas of competence in DigComp 2.1, too.

- Digital skills

Ng ( 2012 ) pointed out the following three categories of digital skills: (a) technological (using technological tools); (b) cognitive (thinking critically when managing information); (c) social (communicating and socialising). A set of Internet skill was suggested by Van Deursen and Van Dijk ( 2009 , 2010b ), which contains: (a) operational skills (basic skills in using internet technology), (b) formal Internet skills (navigation and orientation skills); (c) information Internet skills (fulfilling information needs), and (d) strategic Internet skills (using the internet to reach goals). In 2014, the same authors added communication and content creation skills to the initial framework (van Dijk & van Deursen). Similarly, Helsper and Eynon ( 2013 ) put forward a set of four digital skills: technical, social, critical, and creative skills. Furthermore, van Deursen et al. ( 2015 ) built a set of items and factors to measure Internet skills: operational, information navigation, social, creative, mobile. More recent literature (vaan Laar et al., 2017 ) divides digital skills into seven core categories: technical, information management, communication, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, and problem solving.

It is worth mentioning that the various methodologies used to classify digital literacy are overlapping or non-exhaustive, which confirms the conceptual ambiguity mentioned by van Deursen et al. ( 2015 ).

- Digital thinking

Thinking skills (along with digital skills) have been acknowledged to be a significant element of digital literacy in the educational process context (Ferrari, 2012 ). In fact, critical thinking, creativity, and innovation are at the very core of DigComp. Information and Communication Technology as a support for thinking is a learning objective in any school curriculum. In the same vein, analytical thinking and interdisciplinary thinking, which help solve problems, are yet other concerns of educators in the Industry 4.0 (Ozkan-Ozen & Kazancoglu, 2021 ).

However, we have recently witnessed a shift of focus from learning how to use information and communication technologies to using it while staying safe in the cyber-environment and being aware of alternative facts. Digital thinking would encompass identifying fake news, misinformation, and echo chambers (Sulzer, 2018 ). Not least important, concern about cybersecurity has grown especially in times of political, social or economic turmoil, such as the elections or the Covid-19 crisis (Sulzer, 2018 ; Puig, Blanco-Anaya & Perez-Maceira, 2021 ).

Ultimately, this systematic review paper focuses on the following major research questions as follows:

Research question 1: What is the yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers?

Research question 2: What are the research methods for digital literacy related papers?

Research question 3: What are the main themes in digital literacy related papers?

Research question 4: What are the concentrated categories (under revealed main themes) in digital literacy related papers?

This study employed the systematic review method where the authors scrutinized the existing literature around the major research question of digital literacy. As Uman ( 2011 ) pointed, in systematic literature review, the findings of the earlier research are examined for the identification of consistent and repetitive themes. The systematic review method differs from literature review with its well managed and highly organized qualitative scrutiny processes where researchers tend to cover less materials from fewer number of databases to write their literature review (Kowalczyk & Truluck, 2013 ; Robinson & Lowe, 2015 ).

Data collection

To address major research objectives, the following five important databases are selected due to their digital literacy focused research dominance: 1. WoS/Clarivate Analytics, 2. Proquest Central; 3. Emerald Management Journals; 4. Jstor Business College Collections; 5. Scopus/Elsevier.

The search was made in the second half of June 2021, in abstract and key words written in English language. We only kept research articles and book chapters (herein referred to as papers). Our purpose was to identify a set of digital literacy areas, or an inventory of such areas and topics. To serve that purpose, systematic review was utilized with the following synonym key words for the search: ‘digital literacy’, ‘digital skills’, ‘digital competence’ and ‘digital fluency’, to find the mainstream literature dealing with the topic. These key words were unfolded as a result of the consultation with the subject matter experts (two board members from Korean Digital Literacy Association and two professors from technology studies department). Below are the four key word combinations used in the search: “Digital literacy AND systematic review”, “Digital skills AND systematic review”, “Digital competence AND systematic review”, and “Digital fluency AND systematic review”.

A sequential systematic search was made in the five databases mentioned above. Thus, from one database to another, duplicate papers were manually excluded in a cascade manner to extract only unique results and to make the research smoother to conduct. At this stage, we kept 47 papers. Further exclusion criteria were applied. Thus, only full-text items written in English were selected, and in doing so, three papers were excluded (no full text available), and one other paper was excluded because it was not written in English, but in Spanish. Therefore, we investigated a total number of 43 papers, as shown in Table 1 . “ Appendix A ” shows the list of these papers with full references.

Data analysis

The 43 papers selected after the application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, respectively, were reviewed the materials independently by two researchers who were from two different countries. The researchers identified all topics pertaining to digital literacy, as they appeared in the papers. Next, a third researcher independently analysed these findings by excluded duplicates A qualitative content analysis was manually performed by calculating the frequency of major themes in all papers, where the raw data was compared and contrasted (Fraenkel et al., 2012 ). All three reviewers independently list the words and how the context in which they appeared and then the three reviewers collectively decided for how it should be categorized. Lastly, it is vital to remind that literature review of this article was written after the identification of the themes appeared as a result of our qualitative analyses. Therefore, the authors decided to shape the literature review structure based on the themes.

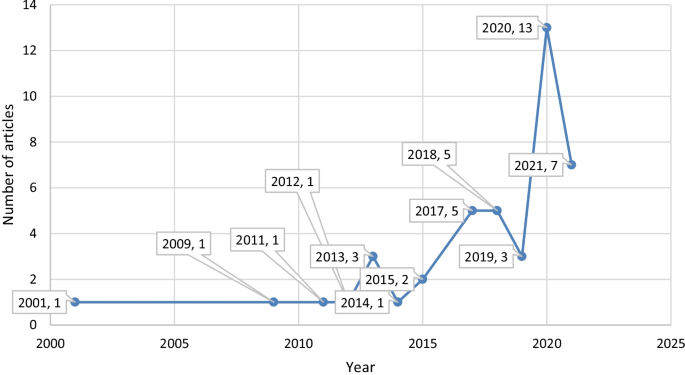

As an answer to the first research question (the yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers), Fig. 1 demonstrates the yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers. It is seen that there is an increasing trend about the digital literacy papers.

Yearly distribution of digital literacy related papers

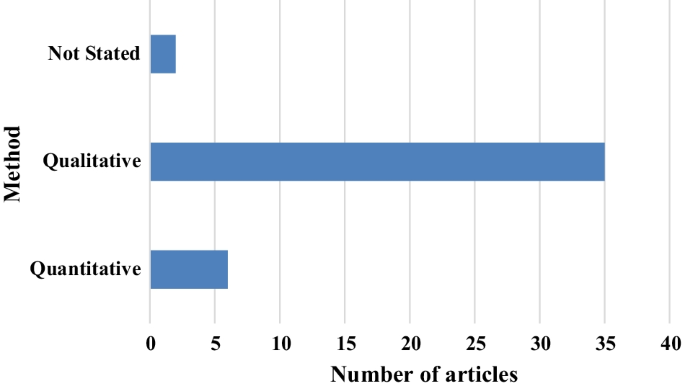

Research question number two (The research methods for digital literacy related papers) concentrates on what research methods are employed for these digital literacy related papers. As Fig. 2 shows, most of the papers were using the qualitative method. Not stated refers to book chapters.

Research methods used in the reviewed articles

When forty-three articles were analysed for the main themes as in research question number three (The main themes in digital literacy related papers), the overall findings were categorized around four major themes: (i) literacies, (ii) competencies, (iii) skills, and (iv) thinking. Under every major theme, the categories were listed and explained as in research question number four (The concentrated categories (under revealed main themes) in digital literacy related papers).

The authors utilized an overt categorization for the depiction of these major themes. For example, when the ‘creativity’ was labelled as a skill, the authors also categorized it under the ‘skills’ theme. Similarly, when ‘creativity’ was mentioned as a competency, the authors listed it under the ‘competencies’ theme. Therefore, it is possible to recognize the same finding under different major themes.

Major theme 1: literacies

Digital literacy being the major concern of this paper was observed to be blatantly mentioned in five papers out forty-three. One of these articles described digital literacy as the human proficiencies to live, learn and work in the current digital society. In addition to these five articles, two additional papers used the same term as ‘critical digital literacy’ by describing it as a person’s or a society’s accessibility and assessment level interaction with digital technologies to utilize and/or create information. Table 2 summarizes the major categories under ‘Literacies’ major theme.

Computer literacy, media literacy and cultural literacy were the second most common literacy (n = 5). One of the article branches computer literacy as tool (detailing with software and hardware uses) and resource (focusing on information processing capacity of a computer) literacies. Cultural literacy was emphasized as a vital element for functioning in an intercultural team on a digital project.

Disciplinary literacy (n = 4) was referring to utilizing different computer programs (n = 2) or technical gadgets (n = 2) with a specific emphasis on required cognitive, affective and psychomotor skills to be able to work in any digital context (n = 3), serving for the using (n = 2), creating and applying (n = 2) digital literacy in real life.

Data literacy, technology literacy and multiliteracy were the third frequent categories (n = 3). The ‘multiliteracy’ was referring to the innate nature of digital technologies, which have been infused into many aspects of human lives.

Last but not least, Internet literacy, mobile literacy, web literacy, new literacy, personal literacy and research literacy were discussed in forty-three article findings. Web literacy was focusing on being able to connect with people on the web (n = 2), discover the web content (especially the navigation on a hyper-textual platform), and learn web related skills through practical web experiences. Personal literacy was highlighting digital identity management. Research literacy was not only concentrating on conducting scientific research ability but also finding available scholarship online.

Twenty-four other categories are unfolded from the results sections of forty-three articles. Table 3 presents the list of these other literacies where the authors sorted the categories in an ascending alphabetical order without any other sorting criterion. Primarily, search, tagging, filtering and attention literacies were mainly underlining their roles in information processing. Furthermore, social-structural literacy was indicated as the recognition of the social circumstances and generation of information. Another information-related literacy was pointed as publishing literacy, which is the ability to disseminate information via different digital channels.

While above listed personal literacy was referring to digital identity management, network literacy was explained as someone’s social networking ability to manage the digital relationship with other people. Additionally, participatory literacy was defined as the necessary abilities to join an online team working on online content production.

Emerging technology literacy was stipulated as an essential ability to recognize and appreciate the most recent and innovative technologies in along with smart choices related to these technologies. Additionally, the critical literacy was added as an ability to make smart judgements on the cost benefit analysis of these recent technologies.

Last of all, basic, intermediate, and advanced digital assessment literacies were specified for educational institutions that are planning to integrate various digital tools to conduct instructional assessments in their bodies.

Major theme 2: competencies

The second major theme was revealed as competencies. The authors directly categorized the findings that are specified with the word of competency. Table 4 summarizes the entire category set for the competencies major theme.

The most common category was the ‘digital competence’ (n = 14) where one of the articles points to that category as ‘generic digital competence’ referring to someone’s creativity for multimedia development (video editing was emphasized). Under this broad category, the following sub-categories were associated:

Problem solving (n = 10)

Safety (n = 7)

Information processing (n = 5)

Content creation (n = 5)

Communication (n = 2)

Digital rights (n = 1)

Digital emotional intelligence (n = 1)

Digital teamwork (n = 1)

Big data utilization (n = 1)

Artificial Intelligence utilization (n = 1)

Virtual leadership (n = 1)

Self-disruption (in along with the pace of digitalization) (n = 1)

Like ‘digital competency’, five additional articles especially coined the term as ‘digital competence as a life skill’. Deeper analysis demonstrated the following points: social competences (n = 4), communication in mother tongue (n = 3) and foreign language (n = 2), entrepreneurship (n = 3), civic competence (n = 2), fundamental science (n = 1), technology (n = 1) and mathematics (n = 1) competences, learning to learn (n = 1) and self-initiative (n = 1).

Moreover, competencies were linked to workplace digital competencies in three articles and highlighted as significant for employability (n = 3) and ‘economic engagement’ (n = 3). Digital competencies were also detailed for leisure (n = 2) and communication (n = 2). Furthermore, two articles pointed digital competencies as an inter-cultural competency and one as a cross-cultural competency. Lastly, the ‘digital nativity’ (n = 1) was clarified as someone’s innate competency of being able to feel contented and satisfied with digital technologies.

Major theme 3: skills

The third major observed theme was ‘skills’, which was dominantly gathered around information literacy skills (n = 19) and information and communication technologies skills (n = 18). Table 5 demonstrates the categories with more than one occurrence.

Table 6 summarizes the sub-categories of the two most frequent categories of ‘skills’ major theme. The information literacy skills noticeably concentrate on the steps of information processing; evaluation (n = 6), utilization (n = 4), finding (n = 3), locating (n = 2) information. Moreover, the importance of trial/error process, being a lifelong learner, feeling a need for information and so forth were evidently listed under this sub-category. On the other hand, ICT skills were grouped around cognitive and affective domains. For instance, while technical skills in general and use of social media, coding, multimedia, chat or emailing in specific were reported in cognitive domain, attitude, intention, and belief towards ICT were mentioned as the elements of affective domain.

Communication skills (n = 9) were multi-dimensional for different societies, cultures, and globalized contexts, requiring linguistic skills. Collaboration skills (n = 9) are also recurrently cited with an explicit emphasis for virtual platforms.

‘Ethics for digital environment’ encapsulated ethical use of information (n = 4) and different technologies (n = 2), knowing digital laws (n = 2) and responsibilities (n = 2) in along with digital rights and obligations (n = 1), having digital awareness (n = 1), following digital etiquettes (n = 1), treating other people with respect (n = 1) including no cyber-bullying (n = 1) and no stealing or damaging other people (n = 1).

‘Digital fluency’ involved digital access (n = 2) by using different software and hardware (n = 2) in online platforms (n = 1) or communication tools (n = 1) or within programming environments (n = 1). Digital fluency also underlined following recent technological advancements (n = 1) and knowledge (n = 1) including digital health and wellness (n = 1) dimension.

‘Social intelligence’ related to understanding digital culture (n = 1), the concept of digital exclusion (n = 1) and digital divide (n = 3). ‘Research skills’ were detailed with searching academic information (n = 3) on databases such as Web of Science and Scopus (n = 2) and their citation, summarization, and quotation (n = 2).

‘Digital teaching’ was described as a skill (n = 2) in Table 4 whereas it was also labelled as a competence (n = 1) as shown in Table 3 . Similarly, while learning to learn (n = 1) was coined under competencies in Table 3 , digital learning (n = 2, Table 4 ) and life-long learning (n = 1, Table 5 ) were stated as learning related skills. Moreover, learning was used with the following three terms: learning readiness (n = 1), self-paced learning (n = 1) and learning flexibility (n = 1).

Table 7 shows other categories listed below the ‘skills’ major theme. The list covers not only the software such as GIS, text mining, mapping, or bibliometric analysis programs but also the conceptual skills such as the fourth industrial revolution and information management.

Major theme 4: thinking

The last identified major theme was the different types of ‘thinking’. As Table 8 shows, ‘critical thinking’ was the most frequent thinking category (n = 4). Except computational thinking, the other categories were not detailed.

Computational thinking (n = 3) was associated with the general logic of how a computer works and sub-categorized into the following steps; construction of the problem (n = 3), abstraction (n = 1), disintegration of the problem (n = 2), data collection, (n = 2), data analysis (n = 2), algorithmic design (n = 2), parallelization & iteration (n = 1), automation (n = 1), generalization (n = 1), and evaluation (n = 2).

A transversal analysis of digital literacy categories reveals the following fields of digital literacy application:

Technological advancement (IT, ICT, Industry 4.0, IoT, text mining, GIS, bibliometric analysis, mapping data, technology, AI, big data)

Networking (Internet, web, connectivity, network, safety)

Information (media, news, communication)

Creative-cultural industries (culture, publishing, film, TV, leisure, content creation)

Academia (research, documentation, library)

Citizenship (participation, society, social intelligence, awareness, politics, rights, legal use, ethics)

Education (life skills, problem solving, teaching, learning, education, lifelong learning)

Professional life (work, teamwork, collaboration, economy, commerce, leadership, decision making)

Personal level (critical thinking, evaluation, analytical thinking, innovative thinking)

This systematic review on digital literacy concentrated on forty-three articles from the databases of WoS/Clarivate Analytics, Proquest Central, Emerald Management Journals, Jstor Business College Collections and Scopus/Elsevier. The initial results revealed that there is an increasing trend on digital literacy focused academic papers. Research work in digital literacy is critical in a context of disruptive digital business, and more recently, the pandemic-triggered accelerated digitalisation (Beaunoyer, Dupéré & Guitton, 2020 ; Sousa & Rocha 2019 ). Moreover, most of these papers were employing qualitative research methods. The raw data of these articles were analysed qualitatively using systematic literature review to reveal major themes and categories. Four major themes that appeared are: digital literacy, digital competencies, digital skills and thinking.

Whereas the mainstream literature describes digital literacy as a set of photo-visual, real-time, information, branching, reproduction and social-emotional thinking (Eshet-Alkalai, 2012 ) or as a set of precise specific operations, i.e., finding, consuming, creating, communicating and sharing digital content (Heitin, 2016 ), this study reveals that digital literacy revolves around and is in connection with the concepts of computer literacy, media literacy, cultural literacy or disciplinary literacy. In other words, the present systematic review indicates that digital literacy is far broader than specific tasks, englobing the entire sphere of computer operation and media use in a cultural context.

The digital competence yardstick, DigComp (Carretero, Vuorikari & Punie, 2017 ) suggests that the main digital competencies cover information and data literacy, communication and collaboration, digital content creation, safety, and problem solving. Similarly, the findings of this research place digital competencies in relation to problem solving, safety, information processing, content creation and communication. Therefore, the findings of the systematic literature review are, to a large extent, in line with the existing framework used in the European Union.

The investigation of the main keywords associated with digital skills has revealed that information literacy, ICT, communication, collaboration, digital content creation, research and decision-making skill are the most representative. In a structured way, the existing literature groups these skills in technological, cognitive, and social (Ng, 2012 ) or, more extensively, into operational, formal, information Internet, strategic, communication and content creation (van Dijk & van Deursen, 2014 ). In time, the literature has become richer in frameworks, and prolific authors have improved their results. As such, more recent research (vaan Laar et al., 2017 ) use the following categories: technical, information management, communication, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, and problem solving.

Whereas digital thinking was observed to be mostly related with critical thinking and computational thinking, DigComp connects it with critical thinking, creativity, and innovation, on the one hand, and researchers highlight fake news, misinformation, cybersecurity, and echo chambers as exponents of digital thinking, on the other hand (Sulzer, 2018 ; Puig, Blanco-Anaya & Perez-Maceira, 2021 ).

This systematic review research study looks ahead to offer an initial step and guideline for the development of a more contemporary digital literacy framework including digital literacy major themes and factors. The researchers provide the following recommendations for both researchers and practitioners.

Recommendations for prospective research

By considering the major qualitative research trend, it seems apparent that more quantitative research-oriented studies are needed. Although it requires more effort and time, mixed method studies will help understand digital literacy holistically.

As digital literacy is an umbrella term for many different technologies, specific case studies need be designed, such as digital literacy for artificial intelligence or digital literacy for drones’ usage.

Digital literacy affects different areas of human lives, such as education, business, health, governance, and so forth. Therefore, different case studies could be carried out for each of these unique dimensions of our lives. For instance, it is worth investigating the role of digital literacy on lifelong learning in particular, and on education in general, as well as the digital upskilling effects on the labour market flexibility.

Further experimental studies on digital literacy are necessary to realize how certain variables (for instance, age, gender, socioeconomic status, cognitive abilities, etc.) affect this concept overtly or covertly. Moreover, the digital divide issue needs to be analysed through the lens of its main determinants.

New bibliometric analysis method can be implemented on digital literacy documents to reveal more information on how these works are related or centred on what major topic. This visual approach will assist to realize the big picture within the digital literacy framework.

Recommendations for practitioners

The digital literacy stakeholders, policymakers in education and managers in private organizations, need to be aware that there are many dimensions and variables regarding the implementation of digital literacy. In that case, stakeholders must comprehend their beneficiaries or the participants more deeply to increase the effect of digital literacy related activities. For example, critical thinking and problem-solving skills and abilities are mentioned to affect digital literacy. Hence, stakeholders have to initially understand whether the participants have enough entry level critical thinking and problem solving.

Development of digital literacy for different groups of people requires more energy, since each group might require a different set of skills, abilities, or competencies. Hence, different subject matter experts, such as technologists, instructional designers, content experts, should join the team.

It is indispensably vital to develop different digital frameworks for different technologies (basic or advanced) or different contexts (different levels of schooling or various industries).

These frameworks should be updated regularly as digital fields are evolving rapidly. Every year, committees should gather around to understand new technological trends and decide whether they should address the changes into their frameworks.

Understanding digital literacy in a thorough manner can enable decision makers to correctly implement and apply policies addressing the digital divide that is reflected onto various aspects of life, e.g., health, employment, education, especially in turbulent times such as the COVID-19 pandemic is.

Lastly, it is also essential to state the study limitations. This study is limited to the analysis of a certain number of papers, obtained from using the selected keywords and databases. Therefore, an extension can be made by adding other keywords and searching other databases.

Availability of data and materials

The authors present the articles used for the study in “ Appendix A ”.

Baber, H., Fanea-Ivanovici, M., Lee, Y. T., & Tinmaz, H. (2022). A bibliometric analysis of digital literacy research and emerging themes pre-during COVID-19 pandemic. Information and Learning Sciences . https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-10-2021-0090 .

Article Google Scholar

Beaunoyer, E., Dupéré, S., & Guitton, M. J. (2020). COVID-19 and digital inequalities: Reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 111 , 10642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106424

Blau, I., Shamir-Inbal, T., & Avdiel, O. (2020). How does the pedagogical design of a technology-enhanced collaborative academic course promote digital literacies, self-regulation, and perceived learning of students? The Internet and Higher Education, 45 , 100722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100722

Carretero, S., Vuorikari, R., & Punie, Y. (2017). DigComp 2.1: The Digital Competence Framework for Citizens with eight proficiency levels and examples of use (No. JRC106281). Joint Research Centre, https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC106281

Eshet, Y. (2004). Digital literacy: A conceptual framework for survival skills in the digital era. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia , 13 (1), 93–106, https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/4793/

Eshet-Alkalai, Y. (2012). Thinking in the digital era: A revised model for digital literacy. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 9 (2), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.28945/1621

Ferrari, A. (2012). Digital competence in practice: An analysis of frameworks. JCR IPTS, Sevilla. https://ifap.ru/library/book522.pdf

Fraenkel, J. R., Wallen, N. E., & Hyun, H. H. (2012). How to design and evaluate research in education (8th ed.). Mc Graw Hill.

Google Scholar

Heitin, L. (2016). What is digital literacy? Education Week, https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/what-is-digital-literacy/2016/11

Helsper, E. J., & Eynon, R. (2013). Distinct skill pathways to digital engagement. European Journal of Communication, 28 (6), 696–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323113499113

Kowalczyk, N., & Truluck, C. (2013). Literature reviews and systematic reviews: What is the difference ? . Radiologic Technology, 85 (2), 219–222.

Ng, W. (2012). Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Computers & Education, 59 (3), 1065–1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.016

Ozkan-Ozen, Y. D., & Kazancoglu, Y. (2021). Analysing workforce development challenges in the Industry 4.0. International Journal of Manpower . https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-03-2021-0167

Puig, B., Blanco-Anaya, P., & Perez-Maceira, J. J. (2021). “Fake News” or Real Science? Critical thinking to assess information on COVID-19. Frontiers in Education, 6 , 646909. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.646909

Robinson, L., Cotten, S. R., Ono, H., Quan-Haase, A., Mesch, G., Chen, W., Schulz, J., Hale, T. M., & Stern, M. J. (2015). Digital inequalities and why they matter. Information, Communication & Society, 18 (5), 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1012532

Robinson, P., & Lowe, J. (2015). Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39 (2), 103. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12393

Sousa, M. J., & Rocha, A. (2019). Skills for disruptive digital business. Journal of Business Research, 94 , 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.051

Sulzer, A. (2018). (Re)conceptualizing digital literacies before and after the election of Trump. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 17 (2), 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1108/ETPC-06-2017-0098

Tinmaz, H., Fanea-Ivanovici, M., & Baber, H. (2022). A snapshot of digital literacy. Library Hi Tech News , (ahead-of-print).

Uman, L. S. (2011). Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20 (1), 57–59.

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., Helsper, E. J., & Eynon, R. (2015). Development and validation of the Internet Skills Scale (ISS). Information, Communication & Society, 19 (6), 804–823. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2015.1078834

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2009). Using the internet: Skills related problems in users’ online behaviour. Interacting with Computers, 21 , 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2009.06.005

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2010a). Measuring internet skills. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 26 (10), 891–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2010.496338

Van Deursen, A. J. A. M., & van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2010b). Internet skills and the digital divide. New Media & Society, 13 (6), 893–911. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810386774

van Dijk, J. A. G. M., & Van Deursen, A. J. A. M. (2014). Digital skills, unlocking the information society . Palgrave MacMillan.

van Laar, E., van Deursen, A. J. A. M., van Dijk, J. A. G. M., & de Haan, J. (2017). The relation between 21st-century skills and digital skills: A systematic literature review. Computer in Human Behavior, 72 , 577–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.010

Download references

This research is funded by Woosong University Academic Research in 2022.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

AI & Big Data Department, Endicott College of International Studies, Woosong University, Daejeon, South Korea

Hasan Tinmaz

Endicott College of International Studies, Woosong University, Daejeon, South Korea

Yoo-Taek Lee

Department of Economics and Economic Policies, Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania

Mina Fanea-Ivanovici

Abu Dhabi School of Management, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Hasnan Baber

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The authors worked together on the manuscript equally. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hasnan Baber .

Ethics declarations

Competing of interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Tinmaz, H., Lee, YT., Fanea-Ivanovici, M. et al. A systematic review on digital literacy. Smart Learn. Environ. 9 , 21 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-022-00204-y

Download citation

Received : 23 February 2022

Accepted : 01 June 2022

Published : 08 June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-022-00204-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Digital literacy

- Systematic review

- Qualitative research

Advertisement

Teachers’ role in digitalizing education: an umbrella review

- Research Article

- Open access

- Published: 31 October 2022

- Volume 71 , pages 339–365, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Olivia Wohlfart ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5020-6590 1 &

- Ingo Wagner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3915-6793 1

7755 Accesses

9 Citations

18 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

As teachers are central to digitalizing education, we summarize 40 years of research on their role in that process within a systematic umbrella review that includes 23 systematic reviews with a total of 1062 primary studies focusing technology integration and aspects of digital literacy. Our findings highlight the international acceptance of the TPACK framework as well as the need for a clear concept of digital literacy. It is unique that we identify and discuss parallels in developing teachers’ digital literacy and integrating digital technologies in the teaching profession as well as barriers to those goals. We conclude by suggesting future directions for research and describing the implications for schools, teacher education, and institutions providing professional development to in-service teachers.Kindly check and confirm whether the corresponding author is correctly identified.Olivia Wohlfart is correctly identified as corresponding author.

Similar content being viewed by others

Digital Literacy in Teacher Education: Transforming Pedagogy for the Modern Era

From Tinkering Around the Edges to Reconceptualizing Courses: Literacy/English Teacher Educators’ Views and Use of Digital Technology

Digitization in teacher education—quality enhancement, status quo, and professionalization approaches

Charlott Rubach & Iris Backfisch

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A variety of stakeholders must be mutually committed to creating digitally competent schools (Pettersson, 2018 ; Sailer et al., 2021 ), and teachers are seen as crucial to this process of digitalization (Bridwell-Mitchell, 2015 ; Lockton & Fargason, 2019 ). Moreover, the role of teachers in digitalizing education must be recognized as a complex, holistic phenomenon (Ertmer & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, 2010 ). Teachers can be a driving force of digitalization, but the COVID-19 pandemic and associated distance teaching/learning have also made teachers prisoners of the rapid digitalization of society and of the associated expectations for education as they are forced to use digital technologies (Wohlfart et al., 2021 ). Before 2020, some institutions were still discussing data protection guidelines while others were already trying to “crack the code of education reform” (Tienken & Starr, 2020 ). By 2021, this situation had changed entirely, and distance learning and digitalization became inescapable, yet only 41% of teachers internationally reported having learned how to integrate digital technologies into teaching (Drossel et al., 2019 ; IEA, 2019 ). While policy and organizational infrastructure are pivotal in successfully promoting the digitalization of education, research has shown that teachers’ digital literacy is more important in that process than rich access to digital technologies (Pettersson, 2018 ).

Previous research on the role of teachers in this process has often focused either on their (perceived) digital literacy or on their willingness and ability to integrate technology (e.g., Granić & Marangunić, 2019 ; McKnight et al., 2016 ). Various models have been developed to examine the digital literacy of teachers and teacher educators, the most prominent being the Technological-Pedagogical-Content-Knowledge (TPACK) model (Koehler & Mishra, 2008 ; Mishra & Koehler, 2006 ), which acknowledges the complexity of teaching by differentiating seven knowledge domains in the interplay of technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge. Since the model’s first publication in the mid-2000s, the international scientific community has directed much attention and encouragement but also criticism toward it. To date, the original article by Mishra and Koehler ( 2006 ) has been cited over 10,000 times (Google Scholar).

Due to global trends of digitalization, the literature on digitalization in education has flourished in recent decades, occasioning a number of literature reviews in this crowded field. As the number of publications per year relentlessly increases, it has become difficult to stay abreast of current findings, but literature reviews have the advantage of systematically structuring and summarizing the previous literature on a specific topic (Mullins et al., 2014 ). Because teachers are central to implementing digitalization, this second-order review study aims to examine the (main) research focus of previous reviews related to teachers’ perspectives on the digitalization of school education and to identify future directions for research on the role of teachers in this process. Due to varying theoretical approaches and research questions, timeframes and sample groups, previous reviews on teachers’ role on the digital transformation often focus very specific aspects of these. It is unique to this approach, that we are able to identify parallels and connections between overarching themes which have been examined independently in the past. With this holistic overview of research on the digitalization of education from a teachers’ perspective, we aim to answer the following research questions:

What is the (main) research focus of previous reviews concerning teachers’ role in the digitalization of school education?

What is the current state of research on the digital literacy of teachers?

What is the current state of research on the role of teachers in technology integration?

What are the future directions for research focusing on the role of teachers in the digitalization of school education?

To answer these research questions, literature reviews and meta-analyses with a focus on teachers and digitalization were examined by means of a systematic umbrella review.

An abundance of research on teachers and the digitization of education has been conducted in the past decades. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses offer context-specific overviews and critical reviews of these studies and add to our knowledge base. Our goal is to refine this knowledge base by combining these reviews “under one umbrella.” Instead of repeating searches, assessing the study eligibility of included articles, etc., we provide a systematic overview and critical review of research on a complex topic, following the protocol recommended for umbrella reviews by the Joanna Briggs Institute (Aromataris et al., 2015 ). Furthermore, we analyze whether, and discuss how, independently derived conclusions and discussions of these reviews align.

Inclusion criteria

In our umbrella review, we refer to syntheses of research evidence, including systematic reviews and meta-analyses focusing on pre- and in-service teachers’ digital literacy as well as their application of technology-based education in primary and secondary education. Due to the emerging nature of our research topic, we include all available review types and articles (Grant & Booth, 2009 ).

Search procedure

The search was conducted using the search engine EBSCOhost and included the databases Education Resource Complete, Academic Search Complete, and Education Resources Information Center. To ensure the quality of the syntheses, only articles and reviews published in peer-reviewed journals were included. For better reproducibility, we opted for articles in English language as the lingua franca in the global, scientific community. The selected search terms were determined by means of an exploratory literature analysis of scientific and educational policy documents as well as the authors’ expertise.

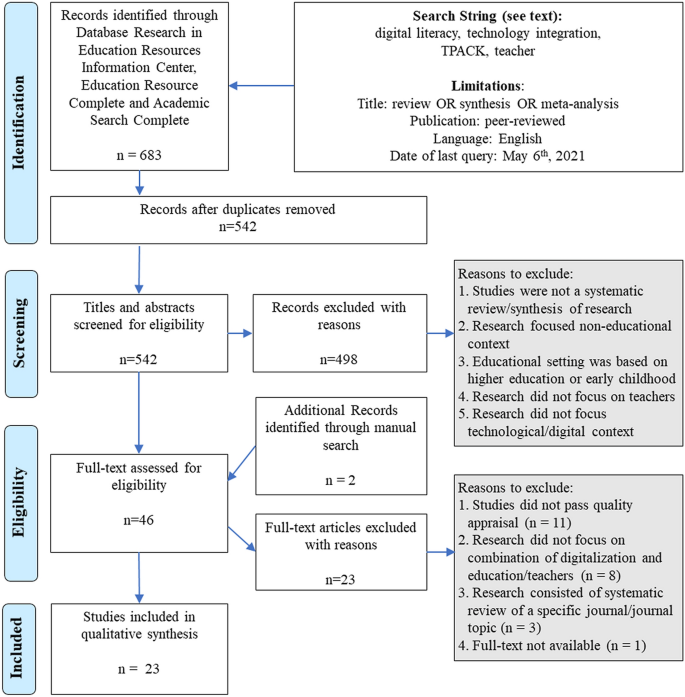

In a first search attempt, we used various synonyms of the terms “digital literacy” and “digital competence” as well as “technology integration” and “educational technology,” with the addition of “teachers” and various “review” methods. As this yielded over 20,000 results, we refined the search string to focus on teachers’ digital literacy and integration of technology. This resulted in the following Boolean search phrase: (“digital literac*” OR “digital competenc*” OR “ICT skill*” OR “digital skill*” OR “computer skill*” OR “technological skill*” OR “e-literac*” OR “multi-modal skill*” OR (“technology” AND (“implementation” OR “integration” OR “application”)) AND teacher* AND (review OR synthesis OR meta-analysis). A total of 9,080 results were identified in the search (date of last search: May 6, 2021). To further reduce the number of articles to a manageable amount, we adapted our search string to consider only studies including “review,” “synthesis,” or “meta-analysis” in the title, which yielded a total of 683 results across the three databases. After duplicates were removed, 542 studies were submitted for further title and abstract screening. Figure 1 summarizes the search (identification) and eligibility steps (screening and checking).

Flow diagram of the literature search and selection of eligible reviews (adapted from the PRISMA Statement; Moher et al., 2009 )

Study selection

All the identified articles were examined by two researchers through an initial screening of titles and abstracts based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This resulted in the exclusion of 498 publications. We excluded articles that did not conduct a systematic review or meta-study as well as those lacking an educational, digital, or teacher-centered focus. Articles focusing on studies of early childhood or higher education were also excluded from further analysis.

Of the selected 44 articles, we were not able to access one paper and received no positive response after reaching out to the authors via email. Furthermore, we conducted hand searches of pertinent academic journals in the field and of the reference lists of the identified articles and extracted two additional papers: Rokenes and Krumsvik ( 2014 ) and Wang et al. ( 2018 ). In summary, 45 articles were read in full text and assessed for eligibility based on the a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Context the study examined digitization in the context of teaching and learning.

Teacher sample the study targeted pre- or in-service teachers in primary or secondary education.

Methodological quality the study was a systematic review or meta-study.

The decision to exclude full-text articles was made by the first author in discussion with the second author. Upon reading the full texts, 11 articles were excluded due to the context or sample of the study.

Next, the methodological quality of the remaining 34 articles was assessed with an appraisal checklist based on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses (Aromataris et al., 2015 ; Moher et al., 2009 ) as well as Gessler and Siemer ( 2020 ). Only articles that at least partially met all the appraisal criteria were included in the subsequent qualitative synthesis of our umbrella review. Eleven articles did not meet the minimum requirements and were excluded from further analysis.

In total, we included 23 articles in our qualitative synthesis based on extensive screening and assessment of the identified records (Fig. 1 ). Except for two meta-analyses, the conducted studies are categorized as systematic reviews with narrative overviews of the state of research on the given topic.

Data analysis

To answer the research questions, we conducted a quantitative and qualitative content analysis of the 23 systematic reviews. For the quantitative analysis, a protocol was developed for categorizing the general characteristics (publication site, research design, included studies, research objective(s)/questions). This was followed by a content-based thematic analysis of the 23 articles to identify latent patterns, themes, and subthemes through an iterative reading and coding process (Braun & Clarke, 2006 ) supported by MAXQDA software. The identified themes were discussed by the team of authors and then recoded by the first author. Finally, 16 categories (with varying numbers of subcategories) were identified from 1780 coded posts.

Quantitative results

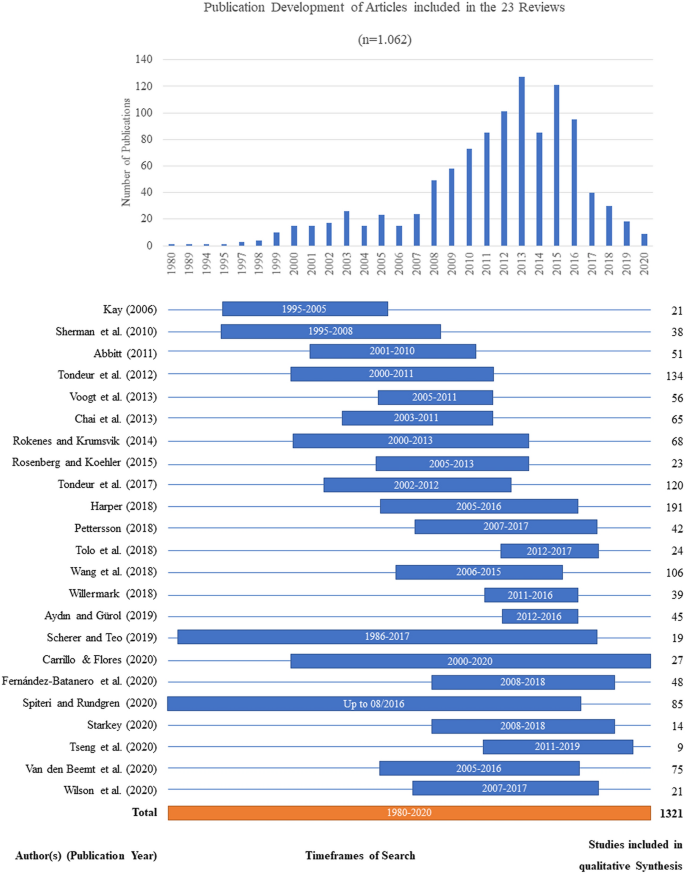

The umbrella review included 23 research articles from 18 scientific journals, published between 2006 and 2020. Without regard to possible duplicates, we found 1321 studies within the reviews. Footnote 1 We identified the overlapping studies among the reviews and determined that this umbrella review includes 1062 studies.

The reviews included studies published between 1980 and 2020 (Fig. 2 ). We found that several authors were mentioned and included repeatedly: Chai, Koh, Koehler, Mishra, Polly, and Tondeur. We also found overlap for several publications; e.g., the study by Niess ( 2005 ) was included in seven of the reviews, six studies were included in five reviews, and a further 14 studies appeared in four reviews. Notwithstanding, 84% of the studies (890) were included in only one review.

Publication development of articles included in the selected reviews (n = 23)

Qualitative findings

The qualitative analysis was guided by the formulated research questions. In " Research focus of previous reviews " section, we provide an overview of the main research foci of the included reviews (RQ 1). Next, we describe the current state of research on teachers’ digital literacy (" Digital literacy " section RQ 2) and their (supposed) role in the integration of technology (" Technology integration "section RQ 3). Finally, in " Future research " section, we identify relevant areas for future research, focusing on the role of teachers and their digital literacy in the digitalization of school education (RQ 4).

Research focus of previous reviews

In regard to RQ 1, we identified six themes as main research foci of previous reviews on the digitalization of school education from the perspective of teachers:

Digital Literacy,

Teacher Preparation (Programs),

Role of Teachers,

Institutional Environment,

Technology Integration, and.

Technology as Tools.

The most prominent theme, which was included in over half of the reviews, concerned teachers’ digital literacy (n = 14). Within these reviews, methods and instruments which assessed and discussed digital literacy of teachers were analyzed (e.g. Rosenberg and Koehler ( 2015 ) critically reflect how context is considered in TPACK research). The role and responsibilities of teacher preparation (programs) was addressed in eleven of the reviews, often in combination with a demand for a better preparation concerning digital literacy (e.g. Rokenes & Krumsvik, 2014 ). Several reviews also focused the critical role of teachers (n = 11) and/or the institutional environment (n = 9) in the process of digital transformation within the education system, highlighting the need for a holistic analysis on digitalization of school education and reliance on further stakeholders (e.g. Pettersson, 2018 ). Critical factors and requirements for successful technology integration were included and discussed in seven of the reviews. Finally, we identified a sixth theme which examined (specific) technologies as tools which influence and support student learning as well as interaction between teachers and students (Harper, 2018 ). Table 1 offers an overview of the main research focus of all 23 reviews as well as the identified themes included within these.

To better understand and classify the diverse foci of the reviews, we examined the theoretical frameworks as applied or recognized by the author(s). In 11 reviews, no specific theoretical framework was applied (cf. Table 1 ). Eight reviews based their work specifically on the TPACK framework. Three further frameworks were applied in individual studies; Carrillo and Flores ( 2020 ) used the Community of Inquiry Framework (Garrison et al., 1999 ) as an analytical tool, Scherer and Teo ( 2019 ) analyzed and discussed the variables of the technology acceptance model (TAM) (Davis, 1986 ) in their meta-analysis, and Tolo et al. ( 2018 ) considered aspects of classroom assessment practices under their own theoretical framework, “Assessment for Learning” (Hopfenbeck et al., 2015 ).

- Digital literacy

To answer RQ2, we analyzed how teachers’ digital literacy was approached in the reviews and considered their main findings. This topic was a thematic focus of 14 of the 23 systematic reviews, including 10 reviews that applied the TPACK framework. We present the findings of our qualitative analysis related to the individual and the assumed concept of digital literacy (4.2.1), TPACK (4.2.2), approaches to developing teachers’ digital literacy (4.2.3), and prevalent requirements (4.2.4).

Concept of digital literacy

The reviews offer a variety of definitions of digital literacy from policy papers and scientific studies alike. Rokenes and Krumsvik ( 2014 , p. 252) follow a definition of digital literacy from Scandinavian studies on ICT in education and include “skills, knowledge, creativity and attitudes” in respect to digital media. Spiteri and Chang Rundgren ( 2020 ) include areas of digital literacy as proposed by the European Commission’s framework for developing and understanding digital competence in Europe (Ferrari, 2013 ; Starkey, 2020 ) differentiates three types of digital competency for teachers: generic digital competency, digital teaching competency, and professional digital competency. The reviews focusing on TPACK, meanwhile, present the original concept of the framework as introduced by Mishra and Koehler ( 2006 ).

Eight reviews specifically focus on the TPACK framework and examine various aspects of previous research, including publication development, the distinction between TPACK knowledge domains, the measurement of TPACK, the interplay between context and TPACK, and model development and TPACK development (Table 2 ).

The reviews report (in broad agreement) on the emergence and publication development of the TPACK model based on the original contribution of Shulman ( 1986 ) and the contributions of Mishra and Koehler (Koehler & Mishra, 2008 ; Mishra & Koehler, 2006 ). In addition, the studies of Pierson ( 2001 ) and Niess ( 2005 ) play a special role. These emerged shortly before and concurrently with the TPACK model, respectively, and refer to TPCK as “technology-enhanced” PCK.

Concerning the distinction of knowledge domains, four reviews specifically acknowledge that a clear definition and delineation of individual knowledge domains is rare and nearly impossible. They also concur that clear definitions and operationalization of knowledge domains would be helpful in (further) developing both the theoretical model and individual survey instruments. The reviews often report TPACK as an overarching knowledge domain. Nevertheless, individual reviews refer to specific knowledge domains, with technical knowledge (TK) taking a special role, as it strongly correlates with the development of TPACK (Wang et al., 2018 ). TK was defined in various ways and aligned with specific technologies (both analog and digital) or types of knowledge (Voogt et al., 2013 ), which points to challenges in distinguishing domain-specific from domain-unspecific technologies (Chai et al., 2013 ) as well as their dynamic and changeable nature over time (Abbitt, 2011 ; Voogt et al., 2013 ; Wang et al., 2018 ).

The most prominent topic discussed in the TPACK reviews is how to measure teachers’ TPACK. Five of the reviews present approaches and instruments for identifying and measuring TPACK, distinguishing between self-assessment and performance assessment, the former being applied in the large majority of studies. The survey instrument developed and validated by Schmidt et al. ( 2009 ) to measure self-perceived TPACK is explicitly highlighted in five of the eight reviews. In addition to quantified surveys, these studies also mention interviews, open-ended questions (mostly in the context of student teaching), interventions (with pre/post survey designs), reflective questionnaires, and document analyses as possible data collection methods. In addition to self-assessment, the reviews acknowledge that performance assessment by experts or peers plays an important role in measuring TPACK; such assessment applies either quantitative or qualitative content analysis (or both) to evaluate observations, reflection sheets, interviews, and classroom materials.

Overall, although they agree on the importance of context in connection with TPACK, the reviews treat this topic rather marginally as a limitation or area for further research and thus refer predominantly to school types, subject areas, pedagogical approaches, and the characteristics and beliefs of teachers. An exception is Rosenberg and Koehler’ ( 2015 ) context-specific review, which discusses the meaning and presence of context in TPACK research based on Porras-Hernández and Salinas-Amescua’s ( 2013 ) conceptual framework for context at three levels (micro, meso, and macro) and among two groups of actors (teachers and students). The authors conclude that context is often missing from research on TPACK and, when included, differs greatly in definition. Additionally, Chai et al. ( 2013 ) propose the “Technological Learning Content Knowledge” (TLCK) framework as a revision of the TPACK framework to include the learner perspective, addressing criticism of the examined studies and contributing to the further development of the model. Analogously, Willermark ( 2018 ) introduces the category of “TPACK as knowledge” versus “TPACK as competence” and examines the extent to which prior studies interpreted TPACK. Based on the results of her review (finding that most previous studies adopted the former perspective), she recommends adopting a changed perspective that understands and examines TPACK as a competence that can be developed and transferred (Willermark, 2018 ).

Approaches to developing teachers’ digital literacy

Ten of the reviews highlight best-practice examples of developing teachers’ digital literacy/TPACK within teacher preparation programs and professional development programs. The most promising approach to developing digital literacy appears to be (role) modelling (in 7 reviews). Rokenes and Krumsvik ( 2014 ) describe this approach as involving “teacher educators, in-service teachers, mentors, and peers promoting particular practices and views of learning through intentionally displaying certain teaching behavior, which could play an important role in shaping student teachers’ professional learning” (p. 262). A significant advantage for preservice teachers is the transferability of this approach to authentic classroom situations (Kay, 2006 ). The role of teacher educators and their training is also highlighted in this context (Tondeur et al., 2012 ), as poor modelling on the part of teacher educators may negatively impact preservice teachers’ TPACK development (Wang et al., 2018 ).

In addition to modelling, collaboration is considered to be important in developing teachers’ digital literacy and enhancing it in various formats; this was examined among preservice teachers, preservice teachers and teacher educators, in-service teachers, and in-service teachers and their students. In this context, the social dimensions of knowledge creation are repeatedly highlighted as important elements in increasing digital literacy.

Authentic learning situations are also highlighted as fruitful elements in developing teachers’ digital literacy (in 5 reviews). In discussing TPACK, Willermark ( 2018 ) argues that the authenticity of learning situations is decisive in the development of (theoretical) knowledge vs. (practical) competence and strongly recommends applying authentic approaches in learning situations to empower teachers both to be digitally literate and to have the skills to apply specific tools in their teaching.

Further strategies to develop teachers’ digital literacy include metacognition as reflection on action, bridging the theory/practice gap, learning by doing, implementing diverse assessment strategies, and blended learning. While the reviews present a variety of strategies, the success or effectiveness of these measures in developing teachers’ digital literacy is seldom reported.

Requirements for developing teachers’ digital literacy

Several reviews critically reflect on the requirements for developing teachers’ digital literacy, highlighting the importance of teacher preparation, the institutional environment, and the role of teachers. The reviews strongly agree on the need to integrate approaches to develope digital literacy in both teacher education (n = 6) and teacher professional development (n = 6) to prepare teachers for digitalized schools. In light of this, digitally literate teacher educators are indispensable in teacher preparation. Tondeur et al. ( 2012 ) recommend the development and maintenance of a technology plan for teacher education that considers both technical and instructional circumstances, with the ultimate goal of empowering end users.

Furthermore, the reviews report that institutional environment significantly affects success in developing digital literacy in various arenas, including leadership (n = 5), the policy debate (n = 4), and school culture (n = 2). Pettersson ( 2018 ) concludes that school leaders are pivotal in translating policies on digital literacy into specific goals and support actions at schools and contends that a failure to do so is the “main barrier for transforming ICT-policies into system-wide professional development and educational change” (p. 1013). A supportive policy debate at the local and national level is also reported as a requirement for enabling the development of preservice teachers’ digital literacy in the context of their teacher preparation (Wilson et al., 2020 ) as well as that of in-service teachers in the context of teacher professional development (Sherman et al., 2010 ). Analogously, a supportive school culture is described as a requirement, especially in further developing in-service teachers’ digital literacy (Spiteri & Chang Rundgren, 2020 ).

A final identified factor in developing digital literacy is the teachers’ role in the process. In the reviews, we identified four areas that directly impact digital literacy and its development: pedagogical beliefs (n = 11), personal characteristics (n = 7), interaction with students (n = 6), and experience with technology (n = 3). While not all these items can be directly influenced, the results highlight two main findings: (1) the evidence shows no differences in developing digital literacy between in-service and pre-service teachers (dispelling the myth of digital natives); (2) introducing and promoting a student-centered, constructivist pedagogical approach in teacher education positively influences the development of digital literacy.

- Technology integration

To answer the third research question, we examined whether and how the reviews discussed the integration and application of technology from the teachers’ perspective. We identified seven reviews which focus aspects of technology integration. The qualitative analysis highlights the relevance of specific strategies, requirements, and barriers to technology integration (4.3.1) as well as various facets of technology acceptance (4.3.2).

Strategies, requirements, and barriers to technology integration

The strategies and requirements for technology integration often mirror approaches to developing digital literacy. According to the qualitative findings, technology integration is influenced by the availability of technical support and facilitation, access to resources, paths to professional development, accurate pedagogical approaches, teachers’ digital literacy, possibilities of collaboration, leadership, and teacher educators. The review authors consent that integrating technology for the first time or integrating new technology requires knowledge of and access to these tools and, furthermore, time to explore them. Wilson et al. ( 2020 ) examine knowledge as key to a better integration of technology and highlight the relevance of specific teacher education courses for technology integration. In this sense, Spiteri and Chang Rundgren ( 2020 ) also underline the time allocated to training and teachers’ perceived support from school as two of the most influential factors in integrating technology. After access and time constraints, teachers’ attitudes or personal fears are repeatedly depicted as negatively affecting technology integration. Additionally, teachers’ fears pertaining to a perceived lack or loss of control is described (e.g. Carrillo & Flores 2020 ). Concerning the integration of social media, van den Beemt et al. ( 2020 , p. 43) report additional barriers related to privacy, security, cyberbullying, and ethics. In conclusion, rather than offering a systematic approach towards technology integration, the reviews highlighted the need to take a closer look at the context of teaching and consider the interdependency of a variety of factors. A broad consensus exists that technology integration is promoted by external support via professional development measures as well as by supportive school environments.

Technology acceptance

Technology integration and application are closely linked with technology acceptance (Davis, 1986 ). In their meta-analysis, Scherer and Teo ( 2019 ) examine teachers’ technology acceptance in light of the theoretical implications of the TAM. Several other reviews also refer to and discuss individual or multiple assumptions of this framework to explain teachers’ intentions to integrate technology or their actual use of it. In relation to the model, researchers report that a number of factors directly influence technology integration, including perceived usefulness (PU; n = 3), perceived ease of use (PEOU; n = 2), and, most prominently, attitude towards technology (ATT; n = 8). In their meta-analysis, Scherer and Teo ( 2019 ) conclude that all relations within the TAM exhibit statistical significance, and they note the validity of PU, PEOU, and ATT in predicting technology integration.

Additionally, researchers have identified a variety of moderator variables that affect teachers’ acceptance and integration of technology. Scherer and Teo ( 2019 ) differentiate these variables as “organizational factors,” “technological factors,” and “individual factors” (p. 92). Among organizational factors, the studies highlight three contextual areas that affect teachers’ technology acceptance and integration: school type and culture, grade level, and subject area. These areas as well as their interdependency are reported to directly affect technology acceptance and, via this, technology integration (Spiteri & Chang Rundgren, 2020 ; Carrillo & Flores, 2020 ) focus on teaching and learning practices and highlight the need to differentiate various organizational situations, such as online teaching. Regarding technological factors, Scherer and Teo’s ( 2019 ) meta-analysis offers no statistical explanation of the effect of technology in general vs. specific technologies on the structural parameters of the TAM. Their meta-analysis, however, did not examine differences between specific technologies. Tondeur et al. ( 2012 ), meanwhile, discuss the advantages of specific technology education courses in transferring and implementing specific digital tools in future classrooms. Finally, teachers’ individual factors (i.e., gender, age, cultural background, intellectual capabilities, experience, subjective norms, and pedagogical beliefs) feature prominently in the results of several reviews. For example, Spiteri and Chang Rundgren ( 2020 ) report that technology acceptance/integration was influenced not by a teacher’s age but rather by teaching experience. In summary, while an abundance of variables on various levels is presented, previous reviews most often focused the influence of teachers’ personal attitudes towards technology in understanding technology acceptance in teaching.

Future research

To answer our last research question, we examined the calls for future research in the individual reviews and identified the following five areas: