What Is the Purpose of Education? Essay

Introduction, understanding the notion of education, the purpose of education, reasons to have education, features of an educated person, works cited.

Education has always been regarded as a significant part of the life of every individual. People had developed a particular understanding of education since the first civilizations appeared. Nowadays, primary education is mandatory for children in most of the countries. This necessity is predetermined by the fact that the individual should have the education to become a full value member of society. Also, education is vital for both personal and professional growth. The importance of education cannot be overestimated because it improves one’s potential and knowledge, promotes the development of society, and enhances the understanding of the surrounding world.

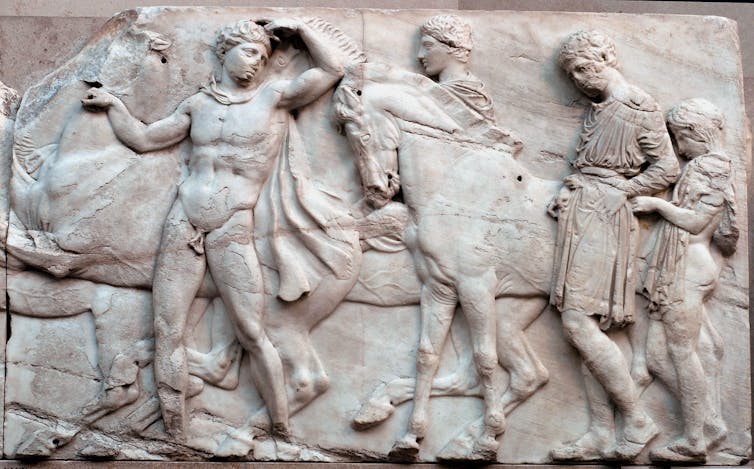

As it has been already mentioned, education became an important part of life since the beginning of humanity. Every epoch and civilization, starting from the Antiquity, shared the particular understanding of the notion of education and relationship between teachers and students. For example, the Ancient Greek understanding of the relationships between educators and learners may be described as follows: “The instructor is not noticeably older than the boys, but they appear to give him the respect and deference that would be due an honored teacher” (Austin 7). Such view of the learning process demonstrates the belief that the relationships between teachers and students should be based on the mutual respect. However, other ancient civilizations shared different views.

Hsun Tsu, a disciple of Confucius, saw education as a strict process of alternation. “He compared the process of educating a child to the process of straightening a piece of wood against a board or sharpening a piece of metal with a stone” (Austin 8). Such an approach is more teacher-centered in comparison to the other. Understanding of the notion of education is connected with its definition as well.

In Wikipedia, education is defined as “the process of facilitating learning, or the acquisition of knowledge, skills, values, beliefs, and habits” (“Education” par. 1). Such understanding of education usually presupposes that the individual studies at school or any other educational establishment to receive particular knowledge. Austin writes about Okakok’s argument that the word “education” should not be used interchangeably with the word “schooling” (79). The author writes that people are tended to speak about an educated person when they mean somebody who has received an official education. “Since all of our traditional knowledge and expertise is of this latter type, the concept of an ‘educated person’ has worked against us as a people, creating conflicting attitudes, and weakening older and proven instructional methods and objects of knowledge” (Austin 79). However, the controversial nature of education is described not only in the meaning of the word.

An interesting view on the nature of education was expressed by Paulo Freire in 1970. According to Freire, education reflects the political situation in the country. In authoritative countries, teachers have the absolute authority over learners who have to follow their orders. Freire considers that the interaction between the teacher and learner has a narrative character. Thus, the teacher is a person who narrates while the student listens. “Education is suffering from narration sickness” (Austin 63). Freire believes that the teacher should let students express their opinions and participate in the process. Ideas of Freire vividly describe one of the purposes of education.

It is difficult to understand and appreciate the significance of education without knowing its purposes. Many students are reluctant to study because they see no point in studying formulas and learning poems by heart. The problem is that not only students but many people are confused when they try to define the purpose of education. Philip Guo writes that many individuals use clichés (e.g. education teaches us how to learn) to explain the purpose of education. “The main purpose of education is to strengthen your mind” (Guo par. 1). Guo considers that permanent learning makes one’s mind strong. Thus, education lets people be prepared to challenging situations in life. Guo provides analog from sport to demonstrate his point of view. He writes that a good player has to work on his or her body all the time. The same is with mental conditioning. Mary Wollstonecraft, one of the first advocates of the rights of women, realizes that all people need to develop the strength of mind. Wollstonecraft writes that people always react to something new or unusual “because they want the activity of mind, because they have not cherished the virtues of the heart” (Austin 37). By asserting the rights of women, Wollstonecraft recognizes the importance of education to become an active member of society.

Education comprises a significant part of the social life. The purpose of education was explained by Nick Gibb, the Minister of Education in the United Kingdom in 2015. Gibb dwelled on that education formed a cornerstone of the economy and social life (Gibb par. 10). This statement describes the second significant purpose of education. Proper education is necessary for being able to live in society. When people study at schools, universities, or other institutions, they happen to be involved in various social situations. Also, educators provide students with knowledge concerning the proper behavior in society often. Seneca wrote, “they [liberal arts] are raw materials out of which a virtuous life can be built — such as they are indispensable to the functioning of a free society” (Austin 16). Thus, education is what makes people prepared to the life with others. It makes everybody familiar with the concepts of justice, equity, and freedom. Such identification of the purpose of education is rather limited at the same time if take into account that education is a much broader concept.

Kim Jones writes that when it comes to finding the solution to the particular problem, education becomes inevitable aspect of the proper decision. Education is crucial for addressing poverty issues or environmental problems. For example, Douglas contemplates that education is directly connected with freedom. The author takes slavery as an example. He writes, “Education goes hand in hand with freedom, and the only way to keep people enslaved is to prevent them from learning and acquiring knowledge” (Austin 46). Jones considers that there is no universal purpose of education because it is a too diverse phenomenon (par. 8). The aim of education is connected with the reasons to have it.

The importance of education cannot be overestimated. It is necessary to evaluate the reasons to have education in various spheres of life. First, education is vital for individual development. When the individual receives knowledge, it alters his or her vision of the world. Also, education promotes the development of critical skills. Thus, educated people know how to analyze different situations (“Why is Education So Important” par. 3). In addition, education is useful for the improvement of character. Education teaches individuals how to become civilized citizens and behave properly. Hsun Tzu uses the word “gentleman” to describe an educated man. Confucius’ follower believes that a proper education is necessary for staying human and making right choices in life. “Therefore, a gentleman will take care in selecting the community he intends to live in, and will choose men of breeding for his companions. In this way he wards off evil and meanness, and draws close to fairness and right” (Austin 10). Education makes the individual aware of the way the world works. An educated person does not believe in illusions.

The second reason to have the education is connected with the professional development. College graduates are more likely to find an interesting job in comparison to those who neglect education. People with education have the possibility to build careers and improve their financial situation (“Importance of Education in Society” par. 4). One may argue that education brings purely material rewards. Still, the feeling of personal growth from career achievements should not be overlooked as well. As Tzu states, “If you make use of the erudition of others and the explanations of gentlemen, then you will become honored and may make your way anywhere in the world” (Austin 12).

The third reason to have education refers to its significance to societies and nations. Kurniawan dwells on the connection of the lack of education with large scale problems such as poverty (1). The writer provides insights from the macroeconomic theory arguing that government’s investment in education results in a better productivity of the labor force. Consequently, people can perform better activities and receive high wages. Also, education makes the whole society aware of the challenges and ways of their overcoming. Even more, education leads to the achievement of the higher level of awareness. “It epitomizes the special characteristics of consciousness: being conscious of , not only as intent on objects but as turned in upon itself in Jasperian “split” — consciousness as consciousness of consciousness” (Austin 65).

The importance of education may be understood after the evaluation of the features of an educated person. Many people consider that an educated person knows a lot of facts and can remember information easily. Knowing facts does not make somebody an educated person. For example, one may memorize numerous things but fail to use them in practice. An educated person should have imagination and the ability to think and use acquired knowledge. Otherwise, no efficient result will be achieved. Al-Ghazali thinks that “effort to acquire knowledge is the worship of mind” (Austin 25). Thus, an educated person enjoys the process of learning something new and knows rationales for all efforts. An educated individual comprehends that education is not about having a diploma or certificate (Burdick par. 5). It is about learning how to live and become a better person.

McKay provides an interesting description of three features of educated people. The author believes that educated people do not wait for someone to entertain them. They always know what to do. Second, any educated person may entertain his or her friend. As far as such individuals know a variety of information, they face no difficulty in amusing others (McKay par. 8). The last distinctive feature of an educated person is open-mindedness. Such an individual is open to new suggestions and ideas. Educated people are not prejudiced or biased against something. They always enjoy learning something new even from the extremely different perspective because it broadens their scope of knowledge.

The role of education has always been important for people. Philosophers and educators of ancient civilizations realized the significance of knowledge acquisition. Nowadays, education has become an integral part of modern life. Education is often defined as the process of acquisition of new knowledge, skills, and habits. However, some scholars argue that such a definition does not reveal the true nature of education because it is more than having certificates or diplomas. Numerous views exist about the purpose of education, but most of them recognize the fact that education aims to improve lives of people. Reasons to have education also predetermine its significance. Thus, educated people are aware of many things in the surrounding world. They cannot be easily tricked. Also, they know the true value of knowledge. Besides, educated people have better opportunities for the professional development in comparison to those who do not have the education. Finally, education brings benefits to the nations. An educated society is a substantial advantage of every country. It is also important to be aware of what makes educated people better and different. Educated people are not only those who know a lot of facts. An educated individual realizes that being able to use knowledge is as important as having knowledge. All these factors demonstrate the significance of education in the modern society.

Austin, Michael. Reading the World: Ideas That Matter. New York City, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010. Print.

Burdick, Eamon. An Educated Person . 2014. Web.

Education n.d. Web.

Importance of Education in Society n.d. Web.

Gibb, Nick. The purpose of education . 2015. Web.

Guo, Philip. The Main Purpose of Education . 2010. Web.

Jones, Kim. What is the purpose of education . 2012. Web.

Kurniawan, Budi. The Important of Education for Economic Growth . n.d. PDF file. 2016.

McKay, Brett. The 3 Characteristics of an Educated Man . 2011. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, May 14). What Is the Purpose of Education? https://ivypanda.com/essays/what-is-the-purpose-of-education/

"What Is the Purpose of Education?" IvyPanda , 14 May 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/what-is-the-purpose-of-education/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'What Is the Purpose of Education'. 14 May.

IvyPanda . 2020. "What Is the Purpose of Education?" May 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/what-is-the-purpose-of-education/.

1. IvyPanda . "What Is the Purpose of Education?" May 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/what-is-the-purpose-of-education/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "What Is the Purpose of Education?" May 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/what-is-the-purpose-of-education/.

- Re-evaluating Freire and Seneca

- Arguments on Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire

- Paulo Freire's Life, Philosophy and Teachings

- The “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” Book by Paulo Freire

- The Banking Concept of Education by Paulo Freire

- Literacy Poses in Paulo Freire’s Philosophy

- College Teaching Method: Paulo Freire's and James Loewen's Ideas

- The “Banking” Concept of Education: An Analysis

- Role of the Notion of Education

- Early Childhood Philosophy of Learning

- Reading and Signing Skills in Deaf Children

- Achieving Academic Excellence

- Ending Cultural and Cognitive Relativism in Special Education

- Technology Revolution in Learning

- Public Policy for Career Development

- Our Mission

What Is Education For?

Read an excerpt from a new book by Sir Ken Robinson and Kate Robinson, which calls for redesigning education for the future.

What is education for? As it happens, people differ sharply on this question. It is what is known as an “essentially contested concept.” Like “democracy” and “justice,” “education” means different things to different people. Various factors can contribute to a person’s understanding of the purpose of education, including their background and circumstances. It is also inflected by how they view related issues such as ethnicity, gender, and social class. Still, not having an agreed-upon definition of education doesn’t mean we can’t discuss it or do anything about it.

We just need to be clear on terms. There are a few terms that are often confused or used interchangeably—“learning,” “education,” “training,” and “school”—but there are important differences between them. Learning is the process of acquiring new skills and understanding. Education is an organized system of learning. Training is a type of education that is focused on learning specific skills. A school is a community of learners: a group that comes together to learn with and from each other. It is vital that we differentiate these terms: children love to learn, they do it naturally; many have a hard time with education, and some have big problems with school.

There are many assumptions of compulsory education. One is that young people need to know, understand, and be able to do certain things that they most likely would not if they were left to their own devices. What these things are and how best to ensure students learn them are complicated and often controversial issues. Another assumption is that compulsory education is a preparation for what will come afterward, like getting a good job or going on to higher education.

So, what does it mean to be educated now? Well, I believe that education should expand our consciousness, capabilities, sensitivities, and cultural understanding. It should enlarge our worldview. As we all live in two worlds—the world within you that exists only because you do, and the world around you—the core purpose of education is to enable students to understand both worlds. In today’s climate, there is also a new and urgent challenge: to provide forms of education that engage young people with the global-economic issues of environmental well-being.

This core purpose of education can be broken down into four basic purposes.

Education should enable young people to engage with the world within them as well as the world around them. In Western cultures, there is a firm distinction between the two worlds, between thinking and feeling, objectivity and subjectivity. This distinction is misguided. There is a deep correlation between our experience of the world around us and how we feel. As we explored in the previous chapters, all individuals have unique strengths and weaknesses, outlooks and personalities. Students do not come in standard physical shapes, nor do their abilities and personalities. They all have their own aptitudes and dispositions and different ways of understanding things. Education is therefore deeply personal. It is about cultivating the minds and hearts of living people. Engaging them as individuals is at the heart of raising achievement.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights emphasizes that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights,” and that “Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.” Many of the deepest problems in current systems of education result from losing sight of this basic principle.

Schools should enable students to understand their own cultures and to respect the diversity of others. There are various definitions of culture, but in this context the most appropriate is “the values and forms of behavior that characterize different social groups.” To put it more bluntly, it is “the way we do things around here.” Education is one of the ways that communities pass on their values from one generation to the next. For some, education is a way of preserving a culture against outside influences. For others, it is a way of promoting cultural tolerance. As the world becomes more crowded and connected, it is becoming more complex culturally. Living respectfully with diversity is not just an ethical choice, it is a practical imperative.

There should be three cultural priorities for schools: to help students understand their own cultures, to understand other cultures, and to promote a sense of cultural tolerance and coexistence. The lives of all communities can be hugely enriched by celebrating their own cultures and the practices and traditions of other cultures.

Education should enable students to become economically responsible and independent. This is one of the reasons governments take such a keen interest in education: they know that an educated workforce is essential to creating economic prosperity. Leaders of the Industrial Revolution knew that education was critical to creating the types of workforce they required, too. But the world of work has changed so profoundly since then, and continues to do so at an ever-quickening pace. We know that many of the jobs of previous decades are disappearing and being rapidly replaced by contemporary counterparts. It is almost impossible to predict the direction of advancing technologies, and where they will take us.

How can schools prepare students to navigate this ever-changing economic landscape? They must connect students with their unique talents and interests, dissolve the division between academic and vocational programs, and foster practical partnerships between schools and the world of work, so that young people can experience working environments as part of their education, not simply when it is time for them to enter the labor market.

Education should enable young people to become active and compassionate citizens. We live in densely woven social systems. The benefits we derive from them depend on our working together to sustain them. The empowerment of individuals has to be balanced by practicing the values and responsibilities of collective life, and of democracy in particular. Our freedoms in democratic societies are not automatic. They come from centuries of struggle against tyranny and autocracy and those who foment sectarianism, hatred, and fear. Those struggles are far from over. As John Dewey observed, “Democracy has to be born anew every generation, and education is its midwife.”

For a democratic society to function, it depends upon the majority of its people to be active within the democratic process. In many democracies, this is increasingly not the case. Schools should engage students in becoming active, and proactive, democratic participants. An academic civics course will scratch the surface, but to nurture a deeply rooted respect for democracy, it is essential to give young people real-life democratic experiences long before they come of age to vote.

Eight Core Competencies

The conventional curriculum is based on a collection of separate subjects. These are prioritized according to beliefs around the limited understanding of intelligence we discussed in the previous chapter, as well as what is deemed to be important later in life. The idea of “subjects” suggests that each subject, whether mathematics, science, art, or language, stands completely separate from all the other subjects. This is problematic. Mathematics, for example, is not defined only by propositional knowledge; it is a combination of types of knowledge, including concepts, processes, and methods as well as propositional knowledge. This is also true of science, art, and languages, and of all other subjects. It is therefore much more useful to focus on the concept of disciplines rather than subjects.

Disciplines are fluid; they constantly merge and collaborate. In focusing on disciplines rather than subjects we can also explore the concept of interdisciplinary learning. This is a much more holistic approach that mirrors real life more closely—it is rare that activities outside of school are as clearly segregated as conventional curriculums suggest. A journalist writing an article, for example, must be able to call upon skills of conversation, deductive reasoning, literacy, and social sciences. A surgeon must understand the academic concept of the patient’s condition, as well as the practical application of the appropriate procedure. At least, we would certainly hope this is the case should we find ourselves being wheeled into surgery.

The concept of disciplines brings us to a better starting point when planning the curriculum, which is to ask what students should know and be able to do as a result of their education. The four purposes above suggest eight core competencies that, if properly integrated into education, will equip students who leave school to engage in the economic, cultural, social, and personal challenges they will inevitably face in their lives. These competencies are curiosity, creativity, criticism, communication, collaboration, compassion, composure, and citizenship. Rather than be triggered by age, they should be interwoven from the beginning of a student’s educational journey and nurtured throughout.

From Imagine If: Creating a Future for Us All by Sir Ken Robinson, Ph.D and Kate Robinson, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by the Estate of Sir Kenneth Robinson and Kate Robinson.

What Is Education? Insights from the World's Greatest Minds

Forty thought-provoking quotes about education..

Posted May 12, 2014 | Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

As we seek to refine and reform today’s system of education , we would do well to ask, “What is education?” Our answers may provide insights that get to the heart of what matters for 21st century children and adults alike.

It is important to step back from divisive debates on grades, standardized testing, and teacher evaluation—and really look at the meaning of education. So I decided to do just that—to research the answer to this straightforward, yet complex question.

Looking for wisdom from some of the greatest philosophers, poets, educators, historians, theologians, politicians, and world leaders, I found answers that should not only exist in our history books, but also remain at the core of current education dialogue.

In my work as a developmental psychologist, I constantly struggle to balance the goals of formal education with the goals of raising healthy, happy children who grow to become contributing members of families and society. Along with academic skills, the educational journey from kindergarten through college is a time when young people develop many interconnected abilities.

As you read through the following quotes, you’ll discover common threads that unite the intellectual, social, emotional, and physical aspects of education. For me, good education facilitates the development of an internal compass that guides us through life.

Which quotes resonate most with you? What images of education come to your mind? How can we best integrate the wisdom of the ages to address today’s most pressing education challenges?

If you are a middle or high school teacher, I invite you to have your students write an essay entitled, “What is Education?” After reviewing the famous quotes below and the images they evoke, ask students to develop their very own quote that answers this question. With their unique quote highlighted at the top of their essay, ask them to write about what helps or hinders them from getting the kind of education they seek. I’d love to publish some student quotes, essays, and images in future articles, so please contact me if students are willing to share!

What Is Education? Answers from 5th Century BC to the 21 st Century

- The principle goal of education in the schools should be creating men and women who are capable of doing new things, not simply repeating what other generations have done. — Jean Piaget, 1896-1980, Swiss developmental psychologist, philosopher

- An education isn't how much you have committed to memory , or even how much you know. It's being able to differentiate between what you know and what you don't. — Anatole France, 1844-1924, French poet, novelist

- Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world. — Nelson Mandela, 1918-2013, South African President, philanthropist

- The object of education is to teach us to love beauty. — Plato, 424-348 BC, philosopher mathematician

- The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character - that is the goal of true education — Martin Luther King, Jr., 1929-1968, pastor, activist, humanitarian

- Education is what remains after one has forgotten what one has learned in school. Albert Einstein, 1879-1955, physicist

- It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it. — Aristotle, 384-322 BC, Greek philosopher, scientist

- Education is the power to think clearly, the power to act well in the world’s work, and the power to appreciate life. — Brigham Young, 1801-1877, religious leader

- Real education should educate us out of self into something far finer – into a selflessness which links us with all humanity. — Nancy Astor, 1879-1964, American-born English politician and socialite

- Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire. — William Butler Yeats, 1865-1939, Irish poet

- Education is freedom . — Paulo Freire, 1921-1997, Brazilian educator, philosopher

- Education is not preparation for life; education is life itself. — John Dewey, 1859-1952, philosopher, psychologist, education reformer

- Education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom. — George Washington Carver, 1864-1943, scientist, botanist, educator

- Education is an admirable thing, but it is well to remember from time to time that nothing that is worth knowing can be taught. — Oscar Wilde, 1854-1900, Irish writer, poet

- The whole purpose of education is to turn mirrors into windows. — Sydney J. Harris, 1917-1986, journalist

- Education's purpose is to replace an empty mind with an open one. — Malcolm Forbes, 1919-1990, publisher, politician

- No one has yet realized the wealth of sympathy, the kindness and generosity hidden in the soul of a child. The effort of every true education should be to unlock that treasure. — Emma Goldman, 1869 – 1940, political activist, writer

- Much education today is monumentally ineffective. All too often we are giving young people cut flowers when we should be teaching them to grow their own plants. — John W. Gardner, 1912-2002, Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare under President Lyndon Johnson

- Education is simply the soul of a society as it passes from one generation to another. — Gilbert K. Chesterton, 1874-1936, English writer, theologian, poet, philosopher

- Education is the movement from darkness to light. — Allan Bloom, 1930-1992, philosopher, classicist, and academician

- Education is learning what you didn't even know you didn't know. -- Daniel J. Boorstin, 1914-2004, historian, professor, attorney

- The aim of education is the knowledge, not of facts, but of values. — William S. Burroughs, 1914-1997, novelist, essayist, painter

- The object of education is to prepare the young to educate themselves throughout their lives. -- Robert M. Hutchins, 1899-1977, educational philosopher

- Education is all a matter of building bridges. — Ralph Ellison, 1914-1994, novelist, literary critic, scholar

- What sculpture is to a block of marble, education is to the soul. — Joseph Addison, 1672-1719, English essayist, poet, playwright, politician

- Education is the passport to the future, for tomorrow belongs to those who prepare for it today. — Malcolm X, 1925-1965, minister and human rights activist

- Education is the key to success in life, and teachers make a lasting impact in the lives of their students. — Solomon Ortiz, 1937-, former U.S. Representative-TX

- The very spring and root of honesty and virtue lie in good education. — Plutarch, 46-120AD, Greek historian, biographer, essayist

- Education is a shared commitment between dedicated teachers, motivated students and enthusiastic parents with high expectations. — Bob Beauprez, 1948-, former member of U.S. House of Representatives-CO

- The most influential of all educational factors is the conversation in a child’s home. — William Temple, 1881-1944, English bishop, teacher

- Education is the leading of human souls to what is best, and making what is best out of them. — John Ruskin, 1819-1900, English writer, art critic, philanthropist

- Education levels the playing field, allowing everyone to compete. — Joyce Meyer, 1943-, Christian author and speaker

- Education is what survives when what has been learned has been forgotten. — B.F. Skinner , 1904-1990, psychologist, behaviorist, social philosopher

- The great end of education is to discipline rather than to furnish the mind; to train it to the use of its own powers rather than to fill it with the accumulation of others. — Tyron Edwards, 1809-1894, theologian

- Let us think of education as the means of developing our greatest abilities, because in each of us there is a private hope and dream which, fulfilled, can be translated into benefit for everyone and greater strength of the nation. — John F. Kennedy, 1917-1963, 35 th President of the United States

- Education is like a lantern which lights your way in a dark alley. — Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, 1918-2004, President of the United Arab Emirates for 33 years

- When educating the minds of our youth, we must not forget to educate their hearts. — Dalai Lama, spiritual head of Tibetan Buddhism

- Education is the ability to listen to almost anything without losing your temper or self-confidence . — Robert Frost, 1874-1963, poet

- The secret in education lies in respecting the student. — Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1803-1882, essayist, lecturer, and poet

- My mother said I must always be intolerant of ignorance, but understanding of illiteracy. That some people, unable to go to school, were more educated and more intelligent than college professors. — Maya Angelou, 1928-, author, poet

©2014 Marilyn Price-Mitchell. All rights reserved. Please contact for permission to reprint.

Marilyn Price-Mitchell, Ph.D., is an Institute for Social Innovation Fellow at Fielding Graduate University and author of Tomorrow’s Change Makers.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

What’s the point of education? It’s no longer just about getting a job

Researcher for the University of Queensland Critical Thinking Project; and Online Teacher at Education Queensland's IMPACT Centre, The University of Queensland

Disclosure statement

Luke Zaphir does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Queensland provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

This essay is part of a series of articles on the future of education.

For much of human history, education has served an important purpose, ensuring we have the tools to survive. People need jobs to eat and to have jobs, they need to learn how to work.

Education has been an essential part of every society. But our world is changing and we’re being forced to change with it. So what is the point of education today?

The ancient Greek model

Some of our oldest accounts of education come from Ancient Greece. In many ways the Greeks modelled a form of education that would endure for thousands of years. It was an incredibly focused system designed for developing statesmen, soldiers and well-informed citizens.

Most boys would have gone to a learning environment similar to a school, although this would have been a place to learn basic literacy until adolescence. At this point, a child would embark on one of two career paths: apprentice or “citizen”.

On the apprentice path, the child would be put under the informal wing of an adult who would teach them a craft. This might be farming, potting or smithing – any career that required training or physical labour.

The path of the full citizen was one of intellectual development. Boys on the path to more academic careers would have private tutors who would foster their knowledge of arts and sciences, as well as develop their thinking skills.

The private tutor-student model of learning would endure for many hundreds of years after this. All male children were expected to go to state-sponsored places called gymnasiums (“school for naked exercise”) with those on a military-citizen career path training in martial arts.

Those on vocational pathways would be strongly encouraged to exercise too, but their training would be simply for good health.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Homer's Iliad

Until this point, there had been little in the way of education for women, the poor and slaves. Women made up half of the population, the poor made up 90% of citizens, and slaves outnumbered citizens 10 or 20 times over .

These marginalised groups would have undergone some education but likely only physical – strong bodies were important for childbearing and manual labour. So, we can safely say education in civilisations like Ancient Greece or Rome was only for rich men.

While we’ve taken a lot from this model, and evolved along the way, we live in a peaceful time compared to the Greeks. So what is it that we want from education today?

We learn to work – the ‘pragmatic purpose’

Today we largely view education as being there to give us knowledge of our place in the world, and the skills to work in it. This view is underpinned by a specific philosophical framework known as pragmatism. Philosopher Charles Peirce – sometimes known as the “father of pragmatism” – developed this theory in the late 1800s.

There has been a long history of philosophies of knowledge and understanding (also known as epistemology). Many early philosophies were based on the idea of an objective, universal truth. For example, the ancient Greeks believed the world was made of only five elements: earth, water, fire, air and aether .

Read more: Where to start reading philosophy?

Peirce, on the other hand, was concerned with understanding the world as a dynamic place. He viewed all knowledge as fallible. He argued we should reject any ideas about an inherent humanity or metaphysical reality.

Pragmatism sees any concept – belief, science, language, people – as mere components in a set of real-world problems.

In other words, we should believe only what helps us learn about the world and require reasonable justification for our actions. A person might think a ceremony is sacred or has spiritual significance, but the pragmatist would ask: “What effects does this have on the world?”

Education has always served a pragmatic purpose. It is a tool to be used to bring about a specific outcome (or set of outcomes). For the most part, this purpose is economic .

Why go to school? So you can get a job.

Education benefits you personally because you get to have a job, and it benefits society because you contribute to the overall productivity of the country, as well as paying taxes.

But for the economics-based pragmatist, not everyone needs to have the same access to educational opportunities. Societies generally need more farmers than lawyers, or more labourers than politicians, so it’s not important everyone goes to university.

You can, of course, have a pragmatic purpose in solving injustice or creating equality or protecting the environment – but most of these are of secondary importance to making sure we have a strong workforce.

Pragmatism, as a concept, isn’t too difficult to understand, but thinking pragmatically can be tricky. It’s challenging to imagine external perspectives, particularly on problems we deal with ourselves.

How to problem-solve (especially when we are part of the problem) is the purpose of a variant of pragmatism called instrumentalism.

Contemporary society and education

In the early part of the 20th century, John Dewey (a pragmatist philosopher) created a new educational framework. Dewey didn’t believe education was to serve an economic goal. Instead, Dewey argued education should serve an intrinsic purpose : education was a good in itself and children became fully developed as people because of it.

Much of the philosophy of the preceding century – as in the works of Kant, Hegel and Mill – was focused on the duties a person had to themselves and their society. The onus of learning, and fulfilling a citizen’s moral and legal obligations, was on the citizens themselves.

Read more: Explainer: what is inquiry-based learning and how does it help prepare children for the real world?

But in his most famous work, Democracy and Education , Dewey argued our development and citizenship depended on our social environment. This meant a society was responsible for fostering the mental attitudes it wished to see in its citizens.

Dewey’s view was that learning doesn’t just occur with textbooks and timetables. He believed learning happens through interactions with parents, teachers and peers. Learning happens when we talk about movies and discuss our ideas, or when we feel bad for succumbing to peer pressure and reflect on our moral failure.

Learning would still help people get jobs, but this was an incidental outcome in the development of a child’s personhood. So the pragmatic outcome of schools would be to fully develop citizens.

Today’s educational environment is somewhat mixed. One of the two goals of the 2008 Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians is that:

All young Australians become successful learners, confident and creative individuals, and active and informed citizens.

But the Australian Department of Education believes:

By lifting outcomes, the government helps to secure Australia’s economic and social prosperity.

A charitable reading of this is that we still have the economic goal as the pragmatic outcome, but we also want our children to have engaging and meaningful careers. We don’t just want them to work for money but to enjoy what they do. We want them to be fulfilled.

Read more: The Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians: what it is and why it needs updating

And this means the educational philosophy of Dewey is becoming more important for contemporary society.

Part of being pragmatic is recognising facts and changes in circumstance. Generally, these facts indicate we should change the way we do things.

On a personal scale, that might be recognising we have poor nutrition and may have to change our diet. On a wider scale, it might require us to recognise our conception of the world is incorrect, that the Earth is round instead of flat.

When this change occurs on a huge scale, it’s called a paradigm shift.

The paradigm shift

Our world may not be as clean-cut as we previously thought. We may choose to be vegetarian to lessen our impact on the environment. But this means we buy quinoa sourced from countries where people can no longer afford to buy a staple, because it’s become a “superfood” in Western kitchens.

If you’re a fan of the show The Good Place, you may remember how this is the exact reason the points system in the afterlife is broken – because life is too complicated for any person to have the perfect score of being good.

All of this is not only confronting to us in a moral sense but also seems to demand we fundamentally alter the way we consume goods.

And climate change is forcing us to reassess how we have lived on this planet for the last hundred years, because it’s clear that way of life isn’t sustainable.

Contemporary ethicist Peter Singer has argued that, given the current political climate, we would only be capable of radically altering our collective behaviour when there has been a massive disruption to our way of life.

If a supply chain is broken by a climate-change-induced disaster, there is no choice but to deal with the new reality. But we shouldn’t be waiting for a disaster to kick us into gear.

Making changes includes seeing ourselves as citizens not only of a community or a country, but also of the world.

Read more: Students striking for climate action are showing the exact skills employers look for

As US philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues, many issues need international cooperation to address . Trade, environment, law and conflict require creative thinking and pragmatism, and we need a different focus in our education systems to bring these about.

Education needs to focus on developing the personhood of children, as well as their capability to engage as citizens (even if current political leaders disagree) .

If you’re taking a certain subject at school or university, have you ever been asked: “But how will that get you a job?” If so, the questioner sees economic goals as the most important outcomes for education.

They’re not necessarily wrong, but it’s also clear that jobs are no longer the only (or most important) reason we learn.

Read the essay on what universities must do to survive disruption and remain relevant.

- Ancient Greece

- The future of education

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

Technical Skills Laboratory Officer

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

In the quest to transform education, putting purpose at the center is key

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, emily markovich morris and emily markovich morris fellow - global economy and development , center for universal education @emilymarmorris ghulam omar qargha ghulam omar qargha fellow - global economy and development , center for universal education.

February 16, 2023

This commentary is the first of a three-part series on (1) why it is important to define the purpose of education, (2) how historical forces have interacted to shape the purposes of today’s modern schooling systems , and (3) the role of power in reshaping how the purpose of school is taken up by global education actors in policy and practice .

Education systems transformation is creating buzz among educators, policymakers, researchers, and families. For the first time, the U.N. secretary general convened the Transforming Education Summit around the subject in 2022. In tandem, UNESCO, UNESCO Institute for Statistics, UNICEF, the World Bank, and the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) co-authored “ From Learning Recovery to Education Transformation ” to lay a roadmap for how to move from COVID-19 school closures to systems change. Donor institutions like the Global Partnership for Education’s most recent strategy centers on systems transformation, and groups like the Global Campaign for Education are advocating for broader public engagement on transformative education.

Unless we anchor ourselves and define where we are coming from and where we want to go as societies and institutions, discussions on systems transformation will continue to be circuitous and contentious.

What is missing from the larger discussion on systems transformation is an intentional and candid dialogue on how societies and institutions are defining the purpose of education. When the topic is discussed, it often misses the mark or proposes an intervention that takes for granted that there is a shared purpose among policymakers, educators, families, students, and other actors. For example, the current global focus on foundational learning is not a purpose unto itself but rather a mechanism for serving a greater purpose — whether for economic development, national identity formation, and/or supporting improved well-being.

The Role of Purpose in Systems Transformation

The purpose of education has sparked many conversations over the centuries. In 1930, Eleanor Roosevelt wrote in her essay in Pictorial Review , “What is the purpose of education? This question agitates scholars, teachers, statesmen, every group, in fact, of thoughtful men and women.” She argues that education is critical for building “good citizenship.” As Martin Luther King, Jr. urged in his 1947 essay, “ The Purpose of Education ,” education transmits “not only the accumulated knowledge of the race but also the accumulated experience of social living.” King urged us to see the purpose of education as a social and political struggle as much as a philosophical one.

In contemporary conversations, the purpose of education is often classified in terms of the individual and social benefits—such personal, cultural, economic, and social purposes or individual/social possibility and individual/social efficiency . However, when countries and communities define the purpose, it needs to be an intentional part of the transformation process. As laid out in the Center for Universal Education’s (CUE’s) policy brief “ Transforming Education Systems: Why, What, and How ,” defining and deconstructing assumptions is critical to building a “broadly shared vision and purpose” of education.

Education and the Sustainable Development Goals

Underlying all the different purposes of education lies the foundational framing of education as a human right in the Sustainable Development Goals. People of all races, ethnicities, gender identities, abilities, languages, religions, socio-economic status, and national or social origins have the right to an education as affirmed in Article 26 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights . This legal framework has fueled the education for all movement and civil rights movements around the world, alongside the Convention of the Rights of the Child of 1989 , which further protects children’s rights to a quality, safe, and equitable education. Defending people’s right to education regardless of how they will use their education helps keep us from losing sight of why we are having these conversations.

Themes in education from the Sustainable Development Goals cross multiple purposes. For example, lifelong learning and environmental education are two key areas that extend across purposes. Lifelong learning emphasizes that education extends across age groups, education levels, modalities, and geographies. In some contexts, lifelong learning can be professional growth for economic development, but it can also be practice for spiritual growth. Similarly, environmental education may be taught as sustainable development or the balance among economic, social, and environmental protections through well-being and flourishing — or taught through a perspective of culturally sustaining practices influenced by Indigenous philosophies in education.

Five Key Purposes of Education

The purposes of education overlap and intersect, but pulling them apart helps us interrogate the dominant ways of framing education in the larger ecosystem and to draw attention to those that receive less attention. Categories also help us move from very philosophical and academic conversations into practical discussions that educators, learners, and families can join. Although these five categories do not do justice to the complexity of the conversation, they are a start.

- Education for economic development is the idea that learners pursue an education to eventually obtain work or to improve the quality, safety, or earnings of their current work. This purpose is the most dominant framing used by education systems around the world and part of the agenda to modernize and develop societies according to different stages of economic growth . This economic purpose is rooted in the human capital theory, which poses that the more schooling a person completes, the higher their income, wages, or productivity ( Aslam & Rawal, 2015; Berman, 2022 ). Higher individual earnings lead to greater household income and eventually higher national economic growth. In addition to the World Bank , global institutions like the United States Agency for International Development and the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development often position education primarily in relation to economic development. The promise of education as a key to social mobility and helping individuals and communities improve their economic circumstances also falls under this purpose ( World Economic Forum ).

- Education for building national identities and civic engagement positions education as an important conduit for promoting national, community, or other identities. With the emergence of modern states, education became a key tool for building national identity — and in some contexts , also democratic citizenship as demonstrated in Eleanor Roosevelt’s essay; this motivation continues to be a primary purpose in many localities ( Verger, Lubienski, & Steiner-Khamsi, 2016 ). Today this purpose is heavily influenced by human right s education — or the teaching and learning of — as well as peace education, to “sustain a just and equitable peace and world” ( Bajaj & Hantzopoulus, 2016, p. 1 ). This purpose is foundational to civics and citizenship education and international exchange programming focused on building global citizenship to name a few.

- Education as liberation and critical conscientization looks at the centrality of education in confronting and redressing different forms of structural oppression. Martin Luther King wrote about the purpose of education “to teach one to think intensively and to think critically.” Educator and philosopher Paolo Freire wrote extensively about the importance of education in developing a critical consciousness and awareness of the roots of oppression, and in identifying opportunities to challenge and transform this oppression through action. Critical race, gender , disabilities, and other theories in education further examine the ways education reproduces multiple and intersectional subordinations , but also how teaching and learning has the power to redress oppression through cultural and social transformation. As liberatory and critical educator, bell hooks wrote, “To educate as a practice of freedom is a way of teaching that anyone can learn” ( hooks, 1994, p. 13 ). Efforts to teach social justice and equity—from racial literacy to gender equity—often draw on this purpose.

- Education for well-being and flourishing emphasizes how learning is fundamental to building thriving people and communities. Although economic well-being is a component of this purpose, it is not the only purpose—rather social, emotional, physical and mental, spiritual and other forms of well-being are also privileged. Amartya Sen’s and Martha Nussbaum’s work on well-being and capabilities have greatly informed this purpose. They argue that individuals and communities must define education in ways that they have reason to value beyond just an economic end. The Flourish Project has been developing and advocating an ecological model for helping understand and map these different types of well-being. Vital to this purpose are also social and emotional learning efforts that support children and youth in acquiring knowledge, attitudes, and skills critical to positive mental and emotional health, relationships with others, among other areas ( CASEL, 2018 ; EASEL Lab, 2023 ).

- Education as culturally and spiritually sustaining is one of the purposes that receives insufficient attention in global education conversations. This purpose is critical to the past, present, and future field of education and emphasizes building relationships to oneself and one’s land and environment, culture, community, and faith. Centered in Indigenous philosophies in education , this purpose encompasses sustaining cultural knowledges often disregarded and displaced by modern schooling efforts. Borrowing from Django Paris’s concept of “culturally sustaining pedagogy , ” the purpose of teaching and learning goes beyond “building bridges” among the home, community, and school and instead brings together the learning practices that happen in these different domains. Similarly neglected in the discourse is the purpose of education for spiritual and religious development, which can be intertwined with Indigenous pedagogies , as well as education for liberation, and education for well-being and flourishing. Examples include the Hibbert Lectures of 1965 , which argue that Christian values should guide the purposes of education, and scholars of Islamic education who delve into the purposes of education in the Muslim world. Indigenous pedagogies, as well as spiritual and religious teaching , predate modern school movements, yet this undercurrent of moral, religious, character, and spiritual purposes of education is still alive in much of the world.

Beyond the Buzz

The way we define the purpose of education is heavily influenced by our experiences, as well as those of our families, communities, and societies. The underlying philosophies of education that are presented both influence our education systems and are influenced by our education systems. Unless we anchor ourselves and define where we are coming from and where we want to go as societies and institutions, discussions on systems transformation will continue to be circuitous and contentious. We will continue to focus on upgrading and changing standards, competencies, content, and practices without looking at why education matters. We will continue to fight over the place of climate change education, critical race theory, socio-emotional learning, and religious learning in our schools without understanding the ways each of these fits into the larger education ecosystem.

The intent of this blog is not to box education into finite purposes, but to remind us in the quest for systems transformation that there are multiple ways to see the purpose of education. Taking time to dig into the philosophies, histories, and complexities behind these purposes will help us ensure that we are headed toward transformation and not just adding to the buzz.

Related Content

Amelia Peterson

February 15, 2023

Devi Khanna, Amelia Peterson

February 10, 2023

Ghulam Omar Qargha, Rangina Hamidi, Iveta Silova

September 16, 2022

Global Education K-12 Education

Global Economy and Development

Center for Universal Education

Modupe (Mo) Olateju, Grace Cannon

April 15, 2024

Brad Olsen, John McIntosh

April 3, 2024

Darcy Hutchins, Emily Markovich Morris, Laura Nora, Carolina Campos, Adelaida Gómez Vergara, Nancy G. Gordon, Esmeralda Macana, Karen Robertson

March 28, 2024

What is Education Essay: Essay on Education for Students in English

Education, a beacon of enlightenment and progress, is a multifaceted concept that transcends the boundaries of classrooms and textbooks. Let’s explore, What is Education Essay.

What is Education?

Education is a powerful journey that people embark on to gain knowledge, learn new skills, and grow as individuals. It’s not just sitting in a classroom. It’s a lifelong adventure that can happen anytime, anywhere.

The essence of education is learning. It’s about discovering new things, understanding the world around us, and finding ways to overcome life’s challenges. Education helps us understand the world and gives us the tools we need to make informed decisions.

One of the main goals of education is the transfer of knowledge. Think of it as a bridge between the wisdom of the past and the possibilities of the future. Throughout history, people have accumulated knowledge about the world, and education ensures that this knowledge is passed on to the next generation.

This knowledge includes facts about science, history, mathematics, literature, etc. It forms the basis on which we build our understanding of the world. But education is more than just memorizing facts and figures. It also leads to skill development.

These skills range from basic skills such as reading, writing, and arithmetic to more advanced skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity. Education is like a toolbox. The more skills you have, the better equipped you are to face life’s challenges.

Education does not only take place within schools. In fact, some of life’s most important lessons can be learned outside the classroom. Learning from experiences, making mistakes, and finding solutions are part of the educational journey. This informal education can be just as valuable, if not more valuable, than what you learn in school.

Moreover, education is not a unified concept. People have different interests, talents, and goals, and education must adapt to the needs of these individuals. Some people thrive in a traditional classroom environment, while others excel with hands-on experience and online learning. The key is to find the approach that works best for you.

Education also plays an important role in our personal growth and development. It helps us discover our passions and talents. It teaches us to be curious, ask questions, and look for answers. It encourages us to set goals and work hard to achieve them. As we learn, we become more confident in our abilities and more aware of the world around us.

Furthermore, education has the power to bring people together. Promote understanding and empathy between different cultures and communities. Learning about other people’s customs, traditions, and perspectives makes us more tolerant and open-minded. Education promotes a sense of unity and cooperation in a diverse world.

What is Education Essay

Education, often referred to as the foundation of civilization, is a complex concept that has evolved throughout human history. Its profound impact on individuals and society cannot be overstated.

This essay explores the complexities of education, looking at its purpose, importance, and the different forms it can take.

Education is not just the acquisition of knowledge, but a transformative process that empowers individuals and enlightens society. The Purpose of Education Education has many purposes, but one of its fundamental purposes is the transfer of knowledge. From ancient civilizations to modern society, education has been the means by which accumulated knowledge and discoveries are passed down from generation to generation. It provides individuals with the skills and information they need to navigate life’s complexities.

Education not only imparts knowledge but also promotes personal growth and development. Promotes problem-solving, critical thinking, and skills of communication. Education is a catalyst that helps individuals realize their potential and develop their talents and abilities.

Furthermore, education plays a central role in promoting social cohesion and equality. It is an effective tool for breaking down barriers and reducing inequalities between different groups within society. Access to quality education can empower marginalized communities and contribute to a more just world. The Significance of Education Education is not limited to the classroom of school or college. It goes far beyond the boundaries of formal institutions. This is a lifelong process that includes both formal and informal learning experiences.

Through education, individuals develop an understanding of the world around them and their place within it. It provides insight into different cultures, perspectives, and lifestyles, promoting tolerance and empathy.

Education is the foundation of progress and innovation. It drives scientific and technological progress and shapes humanity’s future. Promote economic growth by creating a skilled workforce that can contribute to industry and foster entrepreneurship . Education is an investment in the future, and societies that prioritize education tend to thrive.

Education also enables individuals to make informed decisions. This will give you the critical thinking skills you need to analyze complex issues and distinguish between truth and falsehood. In an age of information overload, education is a shield against manipulation and misinformation.

Forms of Education Education comes in many forms, both formal and informal, each with its own benefits. Formal education is structured and delivered through institutions such as schools, colleges, and universities. They follow a curriculum and are often recognized with a certificate or degree.

Non-formal education, on the other hand, takes place outside the classroom and is often self-directed. This includes activities such as reading, exploring nature, participating in community projects, and hobbies. Non-formal education is spontaneous and driven by personal interest and curiosity. Complement formal education by promoting lifelong learning.

Online education is a relatively new development and has changed the educational landscape. We leverage technology to deliver educational content and opportunities to audiences around the world. Online education offers flexibility and accessibility, allowing people to learn at their own pace from anywhere in the world.

Conclusion Education is a multifaceted concept that has a major impact on individuals and society. Its objectives go beyond the transfer of knowledge and include personal development, social cohesion, and equality.

Education is important because it fosters progress, empowers individuals, and equips them with the skills they need to survive in an increasingly complex world. It comes in many forms, both formal and informal, and online education has further revolutionized it.

Also, Read | Online Education Essay

After all, education is the key to self-determination and enlightenment, leading us to a better and more just future.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Essay Topic Generator

- Summary Generator

- Thesis Maker Academic

- Sentence Rephraser

- Read My Paper

- Hypothesis Generator

- Cover Page Generator

- Text Compactor

- Essay Scrambler

- Essay Plagiarism Checker

- Hook Generator

- AI Writing Checker

- Notes Maker

- Overnight Essay Writing

- Topic Ideas

- Writing Tips

- Essay Writing (by Genre)

- Essay Writing (by Topic)

Purpose of Education Essay: Writing Guide & Essay Ideas

“The more you read, the more things you will know, the more you learn, the more places you’ll go.”– these were the words of famous American poet Theodor Seuss Geisel.

Indeed, how do we go anywhere without knowledge, at least of basic notions?

Nevertheless, in the 21st century, people often ask themselves: “What is the purpose of education if I can Google anything?” It may seem you can get any piece of knowledge whenever needed. However, the answer to this question is much bigger than one can imagine.

- 🗣️ 5 Topics to Discuss

📜 Education Essay Topics

- 🎓 Education Essay Samples

🗣️ Education Essay: Top 5 Issues to Discuss

First, let’s see what the most discussed topics about education are. We’ve collected the five most popular themes you can use for the essay.

- We’ll start with the primary purpose of education and the benefits it gives. Why should people get educated?

- Our next stop is the value of education : is education a precious gift? What perspectives does it open?

- We cannot miss the issue of unequal access to education . Why is education a privilege that not all people have? What is done to change it?

- Another essential question is the cost of education : should education be free?

- Finally, we’ll speak about multicultural education : what borders does it break?

Let’s dive in!

What Is the Purpose of Education?

A pretty exciting notion is that education is multifunctional. Even the questions like “why should education be free?” incline one of the purposes of education. Let’s call it enlightenment: coming out of the darkness of ignorance.

Here are a few more significant goals that education pursue:

- Creating conscious, informed citizenry. A state can function properly when its residents know how to live in the community framework. Otherwise, chaos is unavoidable.

- Intellectual development and broad-based knowledge have several benefits. They activate the power of reasonably high self-esteem and self-respect.

- Finally, the basic knowledge of school subjects allows us to understand how the world works.

If you wish to find out more about educational purposes, check this article.

What Is the Value of Education?

What was once said by Kofi Annan perfectly fits at this point:

“Knowledge is power. Information is liberating. Education is the premise of progress, in every society, in every family.”

Developing multiple skills through the education process, a person also learns how to think and make decisions. And these skills can hardly be overestimated: considering people determine how society develops. Education contributes significantly to building up one’s character and mindset. If one realizes the value of practical knowledge and not just the degree, one is destined to succeed.

This is why people need to have equal access to education.

Equal Access to Education. Main Problems

Education is one of the spheres where inequality remains intensive. For example, the USA is considered one of the most advanced countries in the world. Still, the educational gap between the white population and minorities is too vast to ignore. Analysts think the position of students of color is disturbing . This inequity in education predictably leads to a gap in life quality.

The factors contributing to the increase of this gap are:

- Low-quality schools,

- Impoverished neighborhoods,

- Lack of parents’ attention in the upbringing process,

- Discouraged teachers.

Low quality of education leads to an intimidating number of unskilled workers who cannot earn decent amounts of money. That causes increasing crime rates, including petty crimes like thievery and much more severe crimes.

Activists in the field of education equity claim the following regulations to be asserted:

- Better quality schools and more experienced teachers should be integrated with minority communities and neighborhoods.

- The study process should be implemented in smaller groups to increase its quality.

- Children should get access to education earlier. The amount of time spent on learning should be increased, too.

Why Should Education Be Free? Or Shouldn’t?

The tuition fee has been constantly and dramatically growing. The overall student debt in the USA overcomes the amount of a trillion dollars. Low-income families cannot provide an appropriate education for their children.

Still, the question if education should be ultimately free is a pretty debatable issue.

On the one hand, the benefits of free education may seem completely apparent.

- Many talented young people from impoverished households could potentially contribute to society. As we know, university study gives a degree and subject skills and develops networking. It helps promote one into desirable communities or positions.

- Education fee immunity could allow students to focus on gaining knowledge and developing skills necessary for work and social life.

But what is an unobvious side of the question?

- The most fundamental reason against free high education is the tremendous cost of that venue for the government budget. It’s assumed to be more than 70 billion annually.

- Besides, various grants and scholarship programs allow low-income but gifted students to enroll in college. The only problem with it is that not all students have open access to such programs. This issue could be solved by spreading knowledge on available sources such as college websites, for instance.

Why Is Multicultural Education Important?

When we try to answer the question “What is the purpose of education?” we should embrace one of the most valuable education purposes in general—tolerance. The feature is provided by the spaciousness of mind and acceptance of diversity.

We all are different – and that’s great. However, cultural and racial diversity demands various approaches. And sometimes, it can be challenging for educators to achieve this balance. A multicultural society has a chance to flourish when its members experience joint development. This is where the importance of multicultural education becomes evident.

However, this sphere is especially vulnerable. Students’ academic achievement, who belong to minorities, frequently depends on teachers’ attitudes and beliefs. At the same time, any extremities are destructive in this question. To feel happy and encouraged, each society member should be able to express themselves freely. However, it shouldn’t bring harm to others.

- The smaller, the better . How does the number of students in a class affect the education quality in schools and colleges?

- Teaching Culturally and Ethnically Diverse Learners in Science Classroom .

- Supervisory Behaviors in Education .

- Equal Education. How have education conditions for minority representatives changed over the past thirty years? Is there any progress we can embrace?

- The Impact of Modern Technology on Education in Elementary Schools .

- Bringing Science and Social Studies Together: Clinical Field Experience .

- Multicultural education . Consider and classify the positive impacts of multicultural education on society.

- Global Education in Modern Society .

- Racial, ethnic, gender, health, economic and other prejudices. What are the consequences of any kind of bias in the process of education?

- Concepts of Learning Communities .

- A College Education: The Importance of Obtaining .

- Improved schools, more experienced teachers, modern facilities, and more funding. Classify and describe the measures to be taken to increase education quality for low-income pupils.

- Cultural and Linguistic Differences in Education .

- Learning Styles and Strategies .

- Elaborate on Aristotle’s quote about education : “Educating the mind without educating the heart is no education at all.” What did he mean by saying it?

- Scholarship Preparation Program: The Accelerated Learning and Professional Growth .

- Behaviorist, Humanist and Other Learning Theories .

- Analyze the supposed correlation between education and life quality. Does the number of educated people affect society’s well-being and happiness?

- The Benefit of Studying Abroad Compared to Studying in the Home Country .

- Legitimacy of Online Learning Institutions .

- The phenomenal 1,5 trillion of students’ debt. Speculate on the controversial question of whether education should or shouldn’t be free for everyone .

- Memory Techniques in Learning English Vocabulary .

- The real value of education. Touch upon credentials and degrees chasing instead of appreciating the actual knowledge.

- Role of BSN Students in the Promotion of Health .

- Friendships among International and Domestic Students.

- The Impact of Type of Reward on Performance .

- Do you agree that it’s impossible to withhold education from the receptive mind as it is impossible to force it upon the unreasoning?

- Digital Knowledge Platforms Versus Traditional Education Systems .

- Life Skills Need to Be Taught in High Schools .

- Should the government spend means on education institutions more than on warfare?

- What Makes a Successful Teacher?

- Choose two countries to compare their methods for education quality improvement.

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Homeschooling .

- Technology Integration in Special Needs Education.

- Bilingual Education in the USA .

- Do Libraries Provide Sufficient Learning Support to Mature Students?

- Compare and contrast regular and homeschooling: what are the pros and cons of each?

- Teaching Children How to Read and Write .

- What Are the Part-Time Work Benefits for College Students?

- Public Schools Are Better Than Private Schools .

- Burnout in Special Education Teachers .

- How to integrate international students who don’t speak English into the learning process?

- Early Childhood Education Activities and Trends .

- The Benefits of Repeated Reading – Discussion .

- Grants and scholarships: how low-income students can get a quality education for free?

- Adult Education, Its Objectives and Approaches .

- Elementary School Educational Models .

- Does career counseling at high school help potential students avoid mistakes in the future?

- Chinese vs. American Education System .

- Analyze the advantages and disadvantages of early education.

- Plato and Aristotle: Thoughts About Education .

- Investigate the positive impact education has on life quality.

- Social Class and Socialization in Education .

- Learners’ Perception of Personal Learning Environment .

- How to solidify the relationships within multicultural students’ communities?

- Critical Thinking and EFL Learners’ L2 Development .

- Lesson Plan Development Based on English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Model .

- Analyze the role of parents in the education process : can they make it better or worse?

- Student Engagement and Motivation Strategies .

- Investigate the challenges that students with autism face during their study.

- Equal Opportunities for Students With Disabilities .

- What is the connection between high crime rates and low levels of education?

- Teaching Strategies for Students With Autism .

- Education Philosophy and Classroom Management Plan .

- Responsibility of the Teacher .

🧑🎓 Education Essay Samples

To make you feel the value of education fully, we have something in store. Check out our great value of education essay samples to get inspired and create your paper!

Value of Education Essay