Why global health equity matters for all and what organizations can do to advance it

The pursuit of health equity is not just a moral obligation but also a strategic imperative. Image: Unsplash/CDC

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Burgess Harrison

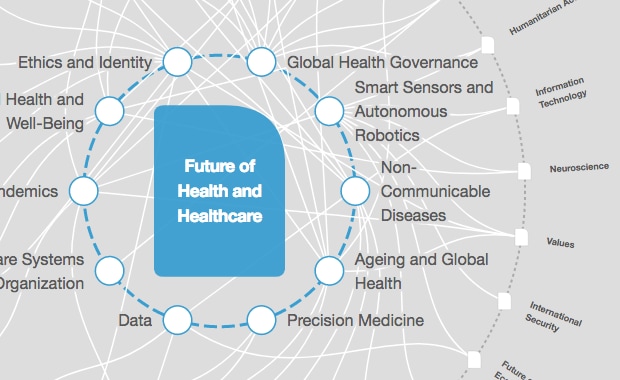

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Health and Healthcare is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, health and healthcare.

- The imperative for global health equity has never been more acute.

- Diseases know no boundaries, and our efforts to combat them must transcend borders, cultures and socio-economic divides.

- By championing health equity, we uplift the most vulnerable and marginalized and strengthen our global community against future health-related challenges.

In an era where the global expenditure on healthcare eclipses $8 trillion annually , a stark paradox emerges.

The World Health Organization (WHO) underscores a monumental investment in health, yet a growing wave of indifference threatens to undermine the fabric of our interconnected health ecosystem. As nations navigate the turbulence of polarization and isolationism, the imperative for global health equity has never been more acute. Here, I dive into the essence of health equity, its universal importance and the actionable steps organizations can undertake to champion this cause.

Global health equity: a collective mission

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a harrowing reminder of our shared vulnerability. It demonstrated unequivocally that the health of the individual is inextricably linked to the global health network. Diseases know no boundaries, and as such, our efforts to combat them must also transcend borders, cultures and socio-economic divides. The pandemic highlighted that indifference towards the health and well-being of communities, both domestically and internationally, can have cascading effects, underscoring the essence of health equity.

The rising tide of indifference

In the United States, resistance to initiatives aimed at fostering health equity is on the rise. Certain states have been at the forefront of opposing affirmative action, diversity, equity, inclusion (DE&I) and health equity programmes. This growing resistance is a microcosm of a larger global trend of retracting into silos, which poses a significant threat to the pursuit of global health equity.

The Global Health and Strategic Outlook 2023 highlighted that there will be an estimated shortage of 10 million healthcare workers worldwide by 2030.

The World Economic Forum’s Centre for Health and Healthcare works with governments and businesses to build more resilient, efficient and equitable healthcare systems that embrace new technologies.

Learn more about our impact:

- Global vaccine delivery: Our contribution to COVAX resulted in the delivery of over 1 billion COVID-19 vaccines and our efforts in launching Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, has helped save more than 13 million lives over the past 20 years .

- Davos Alzheimer's Collaborative: Through this collaborative initiative, we are working to accelerate progress in the discovery, testing and delivery of interventions for Alzheimer's – building a cohort of 1 million people living with the disease who provide real-world data to researchers worldwide.

- Mental health policy: In partnership with Deloitte, we developed a comprehensive toolkit to assist lawmakers in crafting effective policies related to technology for mental health .

- Global Coalition for Value in Healthcare: We are fostering a sustainable and equitable healthcare industry by launching innovative healthcare hubs to address ineffective spending on global health . In the Netherlands, for example, it has provided care for more than 3,000 patients with type 1 diabetes and enrolled 69 healthcare providers who supported 50,000 mothers in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- UHC2030 Private Sector Constituency : This collaboration with 30 diverse stakeholders plays a crucial role in advocating for universal health coverage and emphasizing the private sector's potential to contribute to achieving this ambitious goal.

Want to know more about our centre’s impact or get involved? Contact us .

Championing health equity in challenging environments

Despite these challenges, there is a path forward. Organizations and leaders have a pivotal role in advocating for and implementing strategies promoting health equity. By embracing innovative solutions and harnessing diverse voices, businesses can contribute significantly to this global endeavour.

The pursuit of health equity is not just a moral obligation. It is also a strategic imperative that benefits both the global population and the business community.

The role of businesses in promoting health equity

Businesses wield considerable influence and resources, which can be mobilized to champion the cause of health equity. They can make a substantial impact through corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, public-private partnerships and investments in health technology. And by prioritizing the health and well-being of all stakeholders, businesses contribute to a more equitable world and enhance their resilience and sustainability.

Have you read?

How investors can bolster global health equity while generating long-term value, how poor oral health impacts health equity , how cloud computing is helping close the health equity gap, introducing health — it's about you too.

To galvanize action and foster a culture of health equity, we have created the monthly feature, Health — it's about you, too . This initiative will explore various aspects of global health, sharing stories that highlight our interconnectedness and the importance of collective well-being.

Utilizing the acronym H.E.A.L.T.H— Hope, Education, Advocacy, Leadership, Technology, Humanity: it will highlight the role of hope and humanity in health, advocate for education and leadership in health initiatives and leverage technology for better health outcomes. We will delve into the critical dimensions of health equity without divisive language, inspiring individuals, communities and organizations to take meaningful action.

Each month, the feature will spotlight a different theme, providing insights, case studies and actionable steps for engagement. Through the universal language of art and storytelling, we aim to communicate the urgency of health equity in an engaging and comprehensive manner.

Public, private partnerships and nonprofit collaborative action is being taken as exemplified by:

Health is for EveryBODY™ : from the National Minority Health Association (NMHA) and Sage Growth Partners (SGP) and over 30 organizations highlighting the fact that globally, when it comes to health, we are all in it together with two days of focus: January 4 th was One for All day, and April 1 st is All for One day.

The HEART Framework : Rhia Ventures’ Health Equity Assessment and Rating Tool (HEART Framework), adapted from the Racial Equity Assessment Lab (REAL) Framework , was developed as a standardized approach to identifying where organizations (e.g., investors, nonprofits, startup companies, etc.) are positioned on their journey towards advancing health equity.

The World Economic Forum’s Zero Health Gap Pledge: All organizations have a role in advancing health equity and eliminating disparities in health and wellbeing outcomes between and within countries. The Zero Health Gaps Pledge is a commitment from CEOs across industries and regions for their organizations to play their part by embedding health equity in core strategies, operations, and investments.

Equity for All: Lupus : An NMHA health awareness campaign to address issues faced by people living with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE ) . This effort is supported by the Global Healthy Living Foundation , HealthFirst , Lupus Research Alliance , Biogen and UCB .

CEO Action for Racial Equity : This fellowship is a first-of-its-kind, business-led initiative working to advance racial equity through public policy. It's a Path to Progress , bringing business, communities and policy together to drive change. Through corporate and community engagement, the fellowship is fighting societal systemic racism by advancing racial equity through public policy at the federal, state and local levels. Our focus is to positively impact the 47+ million Black Americans and improve societal well-being.

American Kidney Fund Health Equity Coalition : In the US, Black and Hispanic people fare worse with kidney disease than White people. Black and Hispanic people are more likely to develop kidney failure and are less likely to receive a kidney transplant . It doesn't have to be this way. The American Kidney Fund programmes put solutions into practice that help break down common barriers — so that everyone can equally prevent and get treatment for kidney disease.

American Epilepsy Society Disrupting Disparities Advisory Committee : This project aims to improve outcomes for underserved people with epilepsy by improving the epilepsy clinical knowledge of the non-specialist epilepsy care workforce and deepening understanding of social determinants of health and commitment to epilepsy self-management by the epilepsy specialist workforce.

HLTH Foundation Techquity: The HLTH Foundation launched Techquity for Health a coalition to help integrate health equity standards into healthcare technology and data practices.

Digital Medicine Society : (DiMe) brings a team together in a health equity coalition.

These are a few examples of the collaborative efforts being made to address health equity.

A call to action

The journey towards global health equity is a collective endeavour that requires the concerted effort of individuals, communities and organizations worldwide. We can build a healthier, more equitable world for future generations by fostering a culture of empathy, access and trust. It's not just about the health of the individual but about the well-being of humanity at large. Let us embrace our shared responsibility and act with the urgency and solidarity that global health equity demands.

The domino effect of global health equity can be profound. One small action or effort can often create the energy for change. It reminds us that our actions or inactions have far-reaching consequences. By championing health equity, we not only uplift the most vulnerable and marginalized among us but also strengthen our global community against future health-related challenges. Any business, government or organization can begin to work together to ensure that health equity is not just an ideal but a reality for all. As evidenced by the collaborative efforts underway and in the immortal words of Nike®, when it comes to health equity — Just do it.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Health and Healthcare Systems .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

This Earth Day we consider the impact of climate change on human health

Shyam Bishen and Annika Green

April 22, 2024

Scientists have invented a method to break down 'forever chemicals' in our drinking water. Here’s how

Johnny Wood

April 17, 2024

Young people are becoming unhappier, a new report finds

Promoting healthy habit formation is key to improving public health. Here's why

Adrian Gore

April 15, 2024

What's 'biophilic design' and how can it benefit neurodivergent people?

Fatemeh Aminpour, Ilan Katz and Jennifer Skattebol

Why stemming the rise of antibiotic resistance will be an historic achievement

Carel du Marchie Sarvaas

April 11, 2024

- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Open Access Articles

- Research Collections

- Review Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Health Policy and Planning

- About the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

- HPP at a glance

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, conclusions and recommendations, acknowledgements, the effects of global health initiatives on country health systems: a review of the evidence from hiv/aids control.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Regien G Biesma, Ruairí Brugha, Andrew Harmer, Aisling Walsh, Neil Spicer, Gill Walt, The effects of global health initiatives on country health systems: a review of the evidence from HIV/AIDS control, Health Policy and Planning , Volume 24, Issue 4, July 2009, Pages 239–252, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czp025

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This paper reviews country-level evidence about the impact of global health initiatives (GHIs), which have had profound effects on recipient country health systems in middle and low income countries. We have selected three initiatives that account for an estimated two-thirds of external funding earmarked for HIV/AIDS control in resource-poor countries: the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria, the World Bank Multi-country AIDS Program (MAP) and the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). This paper draws on 31 original country-specific and cross-country articles and reports, based on country-level fieldwork conducted between 2002 and 2007. Positive effects have included a rapid scale-up in HIV/AIDS service delivery, greater stakeholder participation, and channelling of funds to non-governmental stakeholders, mainly NGOs and faith-based bodies. Negative effects include distortion of recipient countries’ national policies, notably through distracting governments from coordinated efforts to strengthen health systems and re-verticalization of planning, management and monitoring and evaluation systems. Sub-national and district studies are needed to assess the degree to which GHIs are learning to align with and build the capacities of countries to respond to HIV/AIDS; whether marginalized populations access and benefit from GHI-funded programmes; and about the cost-effectiveness and long-term sustainability of the HIV and AIDS programmes funded by the GHIs. Three multi-country sets of evaluations, which will be reporting in 2009, will answer some of these questions.

Global health initiatives (GHIs) have enabled wider stakeholder participation in service delivery while often having early negative systems effects through establishing parallel bodies and processes that are poorly coordinated, harmonized and aligned with national systems.

Over time, GHIs have learned to better utilize country systems and support national disease control efforts, while making least progress in enabling countries to implement coordinated financial management and human resource strategies.

Independent longitudinal evaluations of GHIs are needed—especially at district, facility and community levels—to track developments and provide timely information to recipient countries, GHIs, civil society organizations and development agencies.

The past 10 years have witnessed a proliferation of what are commonly called global health initiatives (GHIs). They were put in place as an emergency response to accelerate the scale-up of control of the major communicable diseases, especially HIV/AIDS. GHIs are characterized by their ability to mobilize huge levels of financial resources, linking inputs to performance; and by the channelling of resources directly to non-governmental civil society groups (Caines 2005 ). Three GHIs—the World Bank's Multi-country HIV/AIDS Programme (MAP), the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria, and The President's Emergency Plan For AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) (see Table 1 for main features)—are contributing more than two-thirds of all direct external funding to scaling up HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care in resource-poor countries (GFATM 2007 ; Oomman et al . 2007 ). They have leveraged high-level political support for HIV/AIDS at the global level and captured the attention of country-level stakeholders.

Main characteristics and HIV/AIDS commitments from the three GHIs (in millions of constant US$)

* Sources : OECD CRS database (last accessed 20 November 2008), Oomman et al . ( 2007 ).

Surprisingly, predictions that GHIs were likely to have profound effects on recipient country health systems (Brugha and Walt 2001 ) remain only partially explored (Brugha 2008 ; Yu et al . 2008 ), and speculation rather than systematic review of evidence characterizes current understanding of this major shift towards disease-specific funding, and its impact on health systems in recipient countries. Analysis has focused most closely on the Global Fund, and where analysis has been conducted on MAP and PEPFAR, lessons learned have not been collated and widely disseminated. The purpose of our review, therefore, is to systematically review, discuss and make recommendations for global and country policy makers around future evidence needs, based on available empirical data from countries on the specific effects on country health systems of these three GHIs.

In this review, we follow Brugha ( 2008 ) where, based on functions rather than governance structure, a GHI is defined as: ‘a blueprint for financing, resourcing, coordinating and/or implementing disease control across at least several countries in more than one region of the world’. According to this definition, GHIs may be bilateral agency—government to government—aid mechanisms, as in the case of PEPFAR; they can be established by a multilateral agency, as in the case of the World Bank's MAP; or they may be public-private partnerships, as in the case of the Global Fund. What characterizes them as GHIs is that they use uniform approaches to applying large levels of resources for HIV/AIDS control across a range of different countries and regions. 1 Our analysis of the effects of GHIs on country health systems focuses primarily on the effects that they have on those organizations, institutions and resources that produce actions whose primary purpose is to improve health (WHO 2000), which includes public, non-profit and for-profit private sectors, as well as international and bilateral donors, foundations and voluntary organizations involved in funding or implementing health activities at central, regional, district, community and/or household levels (Islam 2007 ).

Search strategy

In late 2007, we conducted a review of key documents, initially using as search terms research themes derived from a three-country study of the effects of the Global Fund (Stillman and Bennett 2005 ) and a draft of a policy review on GHIs (Brugha 2008 ). These themes and the names of the three selected GHIs were used as search terms for conducting a comprehensive search of six databases (AIDS Portal, CAB Direct, ELDIS, POPLINE, PubMed, and Web of Knowledge) for the period 2002–07. 2 We also performed internet searches for grey literature, reviewing the websites of three global health organizations (The World Bank's Independent Evaluation Group, the Global Fund Evaluation Library, and PEPFAR), and the research archives of three global health research institutes (Centre for Global Development, the UK Department for International Development Health Resource Centre, and Partnerships for Health Reform). Additional publications were obtained through reference lists of identified papers and by contacting key informants in the field.

Criteria for selection

Three authors examined the list of references generated by the search and independently assessed the retrieved studies for inclusion using the following criteria: This review does not include broad overviews of secondary material or ‘grey’ literature (for example, policy briefs, media or journal ‘comments’). We excluded studies restricted to data collection only at the global level, those based only on secondary data, and reviews and commentaries. This was sometimes a difficult judgement as some important reviews contained or cited some relevant primary data, but were excluded if these could not be directly sourced from papers or reports in the public domain.

Reports and papers must provide data about one or more of the key research themes as it relates to one or more of the three HIV/AIDS GHIs: Global Fund, PEPFAR or World Bank MAP;

Reports and papers must present primary data collected at the country level;

There must be some outline of methods, i.e. some explanation of how data were collected and analysed and how findings were derived;

The data are ‘original’. This might take the form of (i) primary qualitative or quantitative research findings; and (ii) external or internal multi-country evaluations of one or more of the GHIs.

A health systems framework for GHIs

Drawing on the conceptual framework for analysing system-wide effects of the Global Fund developed by Bennett and Fairbank ( 2003 ) and selected national-level effects reported in a policy review (Brugha 2008 ), a draft health systems framework was developed. This was composed of three health system's functions: policy development, policy implementation and service delivery. Given the lack of published evidence, 2002–07, on the effects of these GHIs on focal and non-focal services, the framework was shortened and focused on specific themes under policy development and policy implementation. Policy development reflected global concerns around country ownership, harmonization and alignment of global initiatives with national priorities and policies, as expressed in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (OECD 2005 ). Policy implementation explored four cross-cutting health systems themes: coordination and planning, stakeholder engagement, monitoring and evaluation, and human resources (see Table 2 ). As new studies provide additional evidence, the framework can be expanded to include GHI effects on infrastructure and availability of drugs and other equipment; on coverage, equity and access to services; and the effects on non-focal, non-GHI supported services. Under each of these themes, we first present and interpret negative effects, which often correspond with the early effects of the GHIs, followed by positive effects and lessons learned by GHIs across this period.

Framework for assessing the published effects of GHIs on national health systems

Adapted from the SWEF framework by Bennett & Fairbank ( 2003 ) and Brugha ( 2008 ).

Description of studies

Thirty-one reports, where data were collected between 2002 and 2007, met the inclusion criteria (see Table 3 ). Some were disseminated both as individual and as cross-country outputs, notably the four-country Global Fund Tracking Study and the four-country SWEF (System Wide Effects of the Fund) studies. All were descriptive cross-sectional studies. A limited number of studies in this review have collected data both at the national and sub-national level, notably the SWEF study in Georgia, Benin and Ethiopia (Curatio 2004 ; Banteyerga et al . 2006 ; Gbangbadthore et al . 2006 ) and some others (GFATM 2004 ; McKinsey 2005 ; Kelly et al . 2006 ). Most of the studies included in this review used mainly or wholly qualitative methods (in-depth interviews).

Included studies with main characteristics

GF = Global Fund.

National policy development

Alignment to national policy, plans and priorities for health.

Negative effects of all three GHIs were reported by most early studies, including examples of how GHIs distracted governments from coordinated efforts to strengthen health systems through distorting national priorities and through imposing donor implementation conditions (Brugha et al . 2004 ; Grace 2004 ; World Bank 2004 ; McKinsey 2005 ; Stillman and Bennett 2005 ). The Global Fund aims to support programmes that reflect local priorities and fit within existing country structures, but in practice the extent to which this occurred varied widely (Stillman and Bennett 2005 ). The Fund rejected Uganda's 2002 Round One cross-cutting systems-strengthening proposal, requiring Uganda to break it into disease-specific components (Donoghue et al . 2005a ). In response, the Government established a discrete project management unit, which it and its donor partners viewed in 2003 as a distortion of Uganda's policy of channelling all funds to support a coordinated national health sector strategy. Pressure from World Health Organization (WHO) consultants led to Tanzania applying for Global Fund support for an anti-retroviral treatment programme, in place of the government's priority to fund a programme on orphans and children (Starling et al . 2005a ). Concerns were reported about PEPFAR-imposed policy prescriptions such as disallowing grant recipients from providing counselling on abortion and promotion of abstinence-only prevention approaches (ITPC 2005 ). An evaluation commissioned by the US Congress reported that PEPFAR's commitment to country ownership had been undermined by its rigid budget allocations to specific control measures (Sepulveda et al . 2007 ). Oomman et al . ( 2007 ) reported that PEPFAR's funding allocations were remarkably consistent despite epidemiological and health systems’ differences across Mozambique, Uganda and Zambia. This suggested that global earmarks and donor conditionalities were driving funding allocations regardless of countries’ diseases, health needs and priorities.

GHI-imposed priorities and funding decisions also reflected country systems’ weaknesses. An evaluation of the World Bank MAP reported that its approach was undermined by countries lacking national plans that prioritized the components of an HIV/AIDS programme according to their importance or anticipated effectiveness (OED 2005 ). In the early years of MAP, most Ministries of Health had been slow to respond to the HIV epidemic and some felt disempowered by MAP's support to a multisectoral response which channelled funds to other ministries in the fight against AIDS (World Bank 2004 ). The World Bank's interim review found that governments’ multisectoral response to the MAP had been disappointing. The different ministries’ sectoral plans lacked inter-sectorality and had not moved beyond their own workplace interventions to consider programmes for their beneficiaries such as students (Education) and farmers (Agriculture). Despite these early concerns, MAP was evaluated in 2007 as having succeeded in promoting a multisectoral response over the course of its 7 years (Gorgens-Albino et al . 2007 ), which corresponded with positive findings from an independent study in Uganda (Donoghue et al . 2005b ) indicating that GHI approaches had promoted lesson-learning by governments.

Global Fund and PEPFAR have also reportedly learned lessons and modified their processes over time. Studies across 2002–07 suggest that the Global Fund was beginning to adapt its early approach to fit with countries’ priorities for aligning new funds with country systems. In 2006, it was seen as more supportive of Ethiopia's decentralization policies than in 2005 (Banteyerga et al . 2005 ; Banteyerga et al . 2006 ). A follow-up study in Benin showed that the Global Fund was becoming better aligned with Benin's policies on partnership, although the planning of activities remained top-down, which conflicted with bottom-up processes supported by national health policy (Gbangbadthore et al . 2006 ). The US evaluation reported that recipient governments perceived PEPFAR's Country Operational Plans as becoming better aligned with national plans over time (Sepulveda et al . 2007 ). In Mozambique, while PEPFAR remained outside of the Sector Wide Approach (SWAp) pooled mechanism for funding the health and HIV/AIDS sectors, its representatives did participate in the annual planning activities undertaken by the Ministry of Health and National AIDS Council (Oomman et al . 2007 ). In Ethiopia, PEPFAR was working with the government to align with its priorities, although it was channelling its funds to its preferred implementing partners (Banteyerga 2006 ).

Donor harmonization and aid mechanisms

Negative effects on donor harmonization were reported in the early years of the GHIs. Those such as the Global Fund that lacked a country presence were radically new financing mechanisms in the international aid architecture; and they had not agreed with partners about their respective roles and responsibilities (McKinsey 2005 ). Although all of these GHIs had stated their willingness to harmonize their activities with other partners, the reality was often different. For example, the World Bank's review of MAP recommended that it and other donors should adopt ‘The Three Ones’ principles of harmonization: one strategic framework, one national authority and one monitoring and evaluation system for HIV/AIDS (World Bank 2004 ). However, MAP projects themselves continued to burden government officials with extensive and complex procedural and reporting requirements (Oomman et al . 2007 ).

An early synthesis of studies compiled by the Global Fund reported little harmonization between the Global Fund and pre-existing planning and funding mechanisms, such as SWAps and joint interagency committees (GFATM 2004 ). Later, Wilkinson et al . ( 2006 ) reported variable experiences of the Global Fund across different countries. While it supported donor harmonization and alignment efforts in Cambodia, Nigeria and Namibia, it was reportedly undermining these efforts in Sri Lanka and Cameroon, through requiring separate reporting systems with associated transaction costs. PEPFAR's requirement of US Federal Drugs Administration approval of antiretroviral drugs has prevented it relying on the WHO prequalification for quality assurance on which most donors and countries rely (Sepulveda et al . 2007 ). Other barriers to harmonization and collective donor action have included PEPFAR's requirement that results be attributable to its inputs, and its lack of transparency and unwillingness to involve other donors in its own annual planning processes, which have been considered procurement-sensitive (Sepulveda et al . 2007 ).

There is evidence, over time, that the GHIs—especially the Global Fund—have learned lessons and begun to harmonize their approaches and align them with governments. Follow-up studies across 2004 and 2005 in Benin and Ethiopia, where the Global Fund and PEPFAR signed a memorandum of understanding, reported significant improvements in GHI harmonization (Stillman and Bennett 2005 ; Banteyerga 2006 ). The Global Fund's agreement in 2004 to allow its funds be channelled through Mozambique's SWAp, the Common Fund, was seen as a pioneering example of how disease-specific programmes can learn to adapt to and strengthen country systems (McKinsey 2005 ). In Mozambique, the World Bank MAP followed the Global Fund's lead, but PEPFAR remained outside of the SWAp as PEPFAR does not support Ministry of Finance fund management processes (McKinsey 2005 ; Oomman et al . 2007 ). However, despite not being able to contribute funds directly to the SWAp, it had become an active participant in donor partnerships that aimed to harmonize donor and country activities (Oomman et al . 2007 ).

The integration of Global Fund support into Malawi's SWAp to fund its integrated service delivery approach was perceived as positive for its sustainability (Mtonya and Chizimbi 2006 ). The MAP mainly focused its harmonization activities through National AIDS Councils (NACs), where it contributed to pooled-funding to the NAC's Integrated Annual Work Plan for 2003–2008 (Mtonya and Chizimbi 2006 ). In other countries, MAP has contributed funds to support implementation of Global Fund plans, and several MAP projects have implemented joint supervision missions (Gorgens-Albino et al . 2007 ).

Policy implementation

Coordination and planning structures.

The three-disease focus of the Global Fund has required the establishment of a new planning structure: the Country Coordination Mechanism (CCM); and coordination has continued to be a contentious issue for national planners (Wilkinson et al . 2006 ). The result has been duplication in planning for HIV/AIDS control, between CCMs and national AIDS councils. In Uganda, this led to competition between the MoH and the Uganda AIDS Commission for control and funds (Donoghue et al . 2005b ). In Malawi, it was reported that there were parallel planning structures for the NAC Integrated National Work Plan and the SWAp Programme of Work, which Global Fund support had aggravated (Mtonya and Chizimbi 2006 ). The McKinsey study ( 2005 ) found that in Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo there were at least four committees overseeing HIV/AIDS control, with little communication between them about their activities. Respondents in Angola believed there were too many coordinating bodies that did not meet the country's needs (McKinsey 2005 ).

The World Bank, which endorsed the UNAIDS ‘Three Ones’ principles, had a simpler task in that it worked with existing national AIDS councils (OED 2005 ). However, several studies reported longstanding weaknesses in NACs, which have not provided consistent leadership and oversight (Donoghue et al . 2005a ; ITPC 2005 ; Starling et al . 2005a ). Their secretariats have often become implementation agencies rather than coordinators and facilitators (World Bank 2004 ). One three-country study reported that preparation of annual country operational plans, a condition of PEPFAR support, consumed considerable time and effort of recipient organizations in Uganda, Zambia and Mozambique (Oomman et al . 2007 ). While duplication of planning structures has persisted, some positive effects of GHIs on coordination and planning have been reported. In Malawi, after a USAID policy project study in 2004 had pointed to the multiplicity of HIV/AIDS coordinating structures, the Malawi Partnership Forum was created in 2005 as a central coordination structure overarching all existing mechanisms (Mtonya and Chizimbi 2006 ).

Coordination and planning processes

Several studies have reported systemic weaknesses in CCM governance, such as suboptimal communication between its members, and a lack of trust between government and non-government sectors (Brugha et al . 2004 ; Curatio 2004 ; Doupe 2004 ; GFATM 2004 ; Grace 2004 ; Brugha et al . 2005 ; Donoghue et al . 2005a ; ITPC 2005 ; Starling et al . 2005a ; Stillman and Bennett 2005 ; Kelly et al . 2006 ; Wilkinson et al . 2006 ). Often CCMs were too large and unwieldy, which detracted from efficient functioning (Doupe 2004 ; Grace 2004 ). Concerns emerged in 2004 about the degree of participation and the capacity of Mozambique's CCM to adapt to its new role in overseeing Principal Recipient activities, in that the two principal recipients of funding were bodies represented by the Chair and Vice-Chair of the CCM (Starling et al . 2005b ). Similar concerns were also reported in Uganda with regard to the CCM Chair influencing the selection of its own constituency as the principal recipient of funds (Donoghue et al . 2005b ). However, comparable evidence of the effects of the MAP and PEPFAR on planning processes is lacking, reflecting PEPFAR's lack of transparency; and because the World Bank has traditionally negotiated directly with government behind closed doors.

GHI requirements and feed-back have also had positive effects on planning capacity (McKinsey 2005 ). In Georgia and China, feedback on the country proposals enhanced their capacity to plan and anticipate future needs (Curatio 2004 ; van Kerkhoff and Szlezak 2006 ). In Angola, which had recently emerged from conflict and where the risk of HIV/AIDS transmission was increasing, Global Fund and World Bank support was seen as critical in identifying appropriate measures for control of the epidemic (McKinsey 2005 ).

Widening stakeholder involvement: engaging and funding civil society

All three GHIs, most visibly the Global Fund through its CCMs, have boosted stakeholder engagement. However, several negative early effects were reported, which stemmed partly from government responses to these new ways of working. In 2002–04, some governments were perceived to be controlling the Global Fund processes and marginalizing civil society (Brugha et al . 2004 ; Grace 2004 ). Several studies reported problems in CCM constituencies, such as reluctance by government-dominated CCMs to include strong non-governmental partners (including the private for-profit sector), strong advocates for communities living with AIDS, geographical representation and strong technical expertise (Curatio 2004 ; Doupe 2004 ; GFATM 2004 ; Brugha et al . 2005 ; Donoghue et al . 2005a ; ITPC 2005 ; Starling et al . 2005a ; Stillman and Bennett 2005 ; Kelly et al . 2006 ). As a result, the Global Fund introduced tighter conditions, stipulating that CCMs, which prepare proposals and apply for funds, must include these sectors (Wilkinson et al . 2006 ).

Despite early problems, GHIs have been more effective than other financing mechanisms in diversifying stakeholder participation and involving NGOs and faith-based organizations (FBOs), enabling them to gain direct access to financial resources (GFATM 2004 ; OED 2004 ; McKinsey 2005 ; Wilkinson et al . 2006 ). MAP has expanded the scope and range of FBO and community responses to the HIV epidemic (Gorgens-Albino et al . 2007 ; Oomman et al . 2007 ). However, little published evidence was found on how communities’ planning capacity was strengthened. PEPFAR's focus on civil society has been at the expense of building government capacity and through heavy use of US NGOs (Oomman et al . 2007 ). A follow-up survey in Benin showed that the Global Fund CCM had become more pro-active since the baseline survey by including a broader range of stakeholders (Gbangbadthore et al . 2006 ). In Malawi, Benin and Zambia, the new opportunities provided by the Global Fund strengthened public/private collaborations, through NGOs establishing umbrella organizations that helped to channel funds through principal recipients to sub-recipients (Donoghue et al . 2005a ; Mtonya et al . 2005 ; Smith et al . 2005 ; Stillman and Bennett 2005 ). This also served to improve the capacity of local district structures, local NGOs and community groups.

Widening stakeholder involvement: multiple funding channels

Several studies report that GHIs, which focus on the same diseases, channel funds through many different routes, both within and outside the public sector. While there are clear advantages to involving a greater diversity of actors, many countries have found it difficult to cope with the complexity. For example, in Angola MAP channelled funds through the Ministry of Planning rather than the Ministry of Health, which was the usual channel, and the Global Fund did so through the United Nations Development Programme, UNDP (McKinsey 2005 ). PEPFAR, on the other hand, has chosen to channel its funds outside the public sector, mainly through international (often US-based) NGOs. These NGOs then fund country-based civil society and faith-based groups (Oomman et al . 2007 ). There were concerns in South Africa, Uganda, Benin, Ethiopia and Malawi about the rapid growth of the NGO sector, where many new NGOs were seen as having limited capacity and were only weakly accountable (Donoghue et al . 2005b ; Bennett et al . 2006 ; Kelly et al . 2006 ). These studies concluded that too little attention was paid to strengthening community-level systems and to ensuring adequate regulation or quality control in the non-public sector. There has been minimal reported involvement of the private for-profit sector in GHI processes and in receipt of funds, apart from the Global Fund in Malawi where private clinics were allocated free antiretroviral drugs (Stillman and Bennett 2005 ).

Despite concerns about capacity, it has been accepted almost universally as a positive feature of the GHIs that they all have disbursed significant funds to civil society. The Global Fund mandated that 30% of all grants should be allocated to civil society groups (Wilkinson et al . 2006 ); and the SWEF and Tracking Studies reported early evidence that the Global Fund was achieving this objective (Banteyerga et al . 2005 ; Donohoe et al . 2005a ; Mtonya et al . 2005 ; Smith et al . 2005 ).

Disbursement, absorption and management of GHI funds: disbursement and absorptive capacity

From 2002 to 2007, countries reported that the combination of different fiscal years, the different disbursement mechanisms of the three GHIs and unpredictable disbursement had made it difficult for countries to draw down funds and integrate these resources into coordinated national plans (Brugha et al . 2004 ; Grace 2004 ; Stillman and Bennett 2005 ; McKinsey 2005 ; Wilkinson et al . 2006 ; Oomman et al . 2007 ). Tanzania experienced quite similar problems in drawing down MAP and later Global Fund money; and respondents commented on the lack of lesson-learning across GHIs (Starling et al . 2005a ). In the Global Fund Tracking Studies (2003–04) and baseline SWEF studies (2004–05), countries reported immense pressure due to the Global Fund's performance-based disbursement conditions (Brugha et al . 2004 ; Stillman and Bennett 2005 ). Such conditions were not seen as inherently wrong, but as compounding problems of low absorptive capacity due to weak country budgetary systems and incompatible donor systems (ITPC 2005 ; McKinsey 2005 ). In Ethiopia, weak government plans were seen as not providing a solid base for guiding Global Fund-supported activities (Banteyerga et al . 2005 ). In Laos, the Global Fund delayed disbursements until the country resolved its financial, monitoring and evaluation systems’ weaknesses (McKinsey 2005 ). Lack of a country presence (a key feature of the Global Fund), and the slowness of it and its global multilateral and bilateral partners to respond to the need for stronger technical support to countries, often delayed and impaired grant implementation (Wilkinson et al . 2006 ).

On the positive side, evidence has shown that over the years 2002–07, the three GHIs have significantly increased total aid flows in the areas of the focal diseases (Gorgens-Albino et al . 2007 ; Oomman et al . 2007 ; Sepulveda et al . 2007 ). GHIs have been achieving their objective of prioritizing and funding the control of major diseases that were previously under-resourced (McKinsey 2005 ). In Benin, the Global Fund raised the overall budget for health spending by about 15% (Gbangbadthore et al . 2006 ). In the early 2000s, MAP made large commitments to HIV and AIDS control in advance of other donors with US$1 billion being fully committed by 2004 (Gorgens-Albino et al . 2007 ). Since 2004, MAP funding has been more moderate, while the Global Fund and in particular PEPFAR have increased their funding dramatically, as reported for Mozambique, Uganda and Malawi (Oomman et al . 2007 ). PEPFAR has disbursed more quickly than the Global Fund and MAP, partly by working outside of and making little effort to build government systems, which have been slower to draw down funds than non-government recipients (Stillman and Bennett 2005 ; Oomman et al . 2007 ). However, PEPFAR has provided countries with the least flexibility in how funds could be used, whereas the Global Fund has been seen as willing to fund gaps (Oomman et al . 2007 ).

Disbursement, absorption and management of GHI funds: financial management

Several studies have reported GHI-imposed duplication and parallelism in financial and programmatic management systems and cycles, which have created fragmentation and increased the administrative burden for already overloaded staff (Brugha et al . 2004 ; Grace 2004 ; Brugha et al . 2005 ; McKinsey 2005 ; Stillman and Bennett 2005 ; Oomman et al . 2007 ). Although separate systems for financing were sometimes justified, GHIs differed in efforts to use existing systems and/or to improve the capacity of recipient organizations.

The stringent World Bank MAP requirements have often led to the establishment of new financial management systems rather than using standard government systems. However, the World Bank MAP projects have made progress in building reliable country systems for financial management. Specific project staff, who sit within government ministries, were hired to oversee grant implementation and to train government staff in MAP-specific procedures (Oomman et al . 2007 ). PEPFAR, in their function as an emergency response, required recipient organizations that were able to manage funding efficiently and implement fast. Often they have channelled funding outside of the government system, following PEPFAR-specific accounting and reporting procedures, while they relied on their recipient organizations to build the capacity of the government and other local organizations (Oomman et al . 2007 ). The Global Fund has continued to utilize an independent Local Fund Agent (LFA) financial management and audit model. However, evaluations of the LFA system reported that, in practice, LFAs have often not been well aligned with government systems. Frequently they have lacked programmatic skills and have been unable to mobilize and work in partnership with other country partners (Kruse and Claussen 2004 ; Euro Health Group 2007 ). Recently, the Global Fund has been aiming to strengthen its LFA system through providing more comprehensive tools and guidelines for recipient (and sub-recipient) organizations (Euro Health Group 2007 ). However, evaluations of GHIs across 2002–07 have reported little progress in reducing GHI systems’ duplications.

Monitoring and evaluation (M&E)

Parallel systems and processes established by new GHIs contravene the Paris Principles of Aid Effectiveness, often bypassing countries’ own systems, and result in avoidable transaction costs (McKinsey 2005 ). However, M&E requirements of GHIs have often not been streamlined and, as a result, it is generally reported in national studies that managers, at the national and district levels, have to prepare multiple M&E reports, in different formats and with different deadlines for the different donors of their programmes. In some cases, additional indicators have been required that were not part of countries’ own systems (McKinsey 2005 ).

PEPFAR, which operates outside government systems, has continued to use project approaches and expects reporting to be carried out according its formats (Oomman et al . 2007 ). Several studies reported contrasting perceptions of Global Fund alignment with existing country M&E systems (Brugha et al . 2005 ; Wilkinson et al . 2006 ). In Cambodia, Uganda and Cameroon, the use of Global Fund project-related monitoring tools undermined national programmes and the ‘Three Ones’ principle of a single M&E system.

The M&E emphasis of the first generation of the World Bank supported AIDS projects was on monitoring as opposed to evaluation, but was often poorly designed, under-implemented and under-supervised (OED 2005 ). Informants in Tanzania, Malawi, Uganda and Mozambique also expressed concern about weak local M&E capacity or weak systems for monitoring GHI funds and were sceptical of their countries’ ability to demonstrate that they had met agreed targets (Brugha et al . 2005 ). Consequently, GHIs were encountering weak M&E systems and putting in place GHI-specific measures to address these weaknesses.

Improvements over time have been reported in that GHIs have started to work with countries on developing and strengthening their M&E systems (McKinsey 2005 ). In Sri Lanka and Nigeria, Global Fund indicators fitted with the national programme indicators and national M&E activities (Wilkinson et al . 2006 ). The follow-up SWEF studies in Ethiopia and Malawi in 2005–06 reported some improvements in integration, alignment and performance assessment since the baseline studies, one year earlier (Stillman and Bennett 2005 ). Recently, the World Bank developed an operational guide for programme M&E and put in place M&E country assistance capacity in the form of the Global Monitoring and Evaluation Support Team (GAMET), based at the World Bank (Gorgens-Albino et al . 2007 ). Recent findings show that PEPFAR has been supporting building local capacity for collecting, synthesizing and reporting on HIV/AIDS data through skills training, development of health information systems, and technical assistance, although neglecting or avoiding the strengthening of national systems (Sepulveda et al . 2007 ).

Human resources for health: availability of health workers

Shortage of trained staff was reported in early country studies as a major barrier to health systems, and GHI efforts to scale-up antiretroviral treatment services in particular (Grace 2004 ; Brugha et al . 2005 ; Mtonya et al . 2005 ). In 2002–04 in Zambia, it was reported that sufficient numbers of health workers were not being trained to compensate for losses due to illness, death from AIDS, and emigration (Donoghue et al . 2005a ). Both Malawi and Kenya reported public sector health worker shortages, which key informants believed would be aggravated by selectively investing in health workers to work in GHI-funded programmes for control of focal diseases such as HIV/AIDS (World Bank 2004 ; Mtonya et al . 2005 ). Migration of personnel from reproductive health and family planning through re-allocation to ‘follow the money of the Global Fund’ was reported in 2005–06 (Schott et al . 2005 ; Gbangbadthore et al . 2006 ; Wilkinson et al . 2006 ). In Ethiopia, Global Fund supported activities were inducing health workers to move away from the public to the private sector, NGOs and bilateral agencies (Banteyerga et al . 2005 ). The follow-up component of the study suggested this had worsened (Banteyerga et al . 2006 ). The nature of human resource problems varied, with shifts of health workers from public to donor supported projects/programmes as well as to other countries, causing both internal and external ‘brain drain’ (Sepulveda et al . 2007 ). However, national key informants perceived that the broader donor community and GHIs acted similarly in initiating projects that poached qualified staff from routine government programmes and employment, by offering them incentives or higher salaries (Donoghue et al . 2005a ; Drew and Purvis 2006 ).

Over time, positive responses to (partly GHI-induced) health worker shortages were reported. The follow-up study in Ethiopia found that the government had put in place a human resource strategy, which included increases in salaries and incentives to keep health workers in the public sector (Banteyerga et al . 2006 ). PEPFAR has supported a number of activities focused on retention of health workers, providing physicians working in rural areas with better working and living conditions such as housing, transportation, hardship allowances and educational stipends for their children (Sepulveda et al . 2007 ). Malawi's Global Fund Round 5 proposal addressed health worker distribution through aiming to increase community-based services by recruiting, training and retaining Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs) to assist in scaling up antiretrovirals (Mtonya et al . 2005 ). In Benin, the Global Fund was reported to have strengthened infrastructure and provided equipment that health workers needed to better perform their tasks (Gbangbadthore et al . 2006 ).

Human resources for health: workload, motivation and incentives

The combination of the additional workload, which GHI funding has facilitated, and restrictions on public health staffing levels and remuneration have increased the strain on public sector health workers. This has been further exacerbated when GHI-funded activities accelerated staff leakage to the private sector. In Benin, it was reported that workers already working in the public sector earned no additional pay despite the extra work due to the Global Fund. However, programmes that hired health workers directly with Global Fund money were receiving higher salaries (Smith et al . 2005 ). The 2003–04 studies in Zambia and Mozambique reported that the inability to use Global Fund support to supplement the salaries of government staff running HIV programmes—most funds were going to support programme activities and purchase commodities—was de-motivating staff (Donoghue et al . 2005a ; Starling et al . 2005b ). The early focus of PEPFAR was to strengthen the skills of existing health workers to provide HIV care and treatment services and, similar to the Global Fund, funding could not be used to top-up the salaries of existing public sector staff or to hire additional staff (Sepulveda et al . 2007 ). However, in Uganda, the salaries of staff hired by NGOs were supported by PEPAR funds, which enabled them to attract the best health workers from the public sector (Oomman et al . 2007 ). MAP funding could be used for salary top-ups but only at the district government level (Oomman et al . 2007 ).

The studies reviewed here (2002–07) showed little evidence that the early GHI-funded programmes had addressed issues of workload and motivation. Where there were pre-existing shortages of health workers, GHI-supported activities were overburdening already limited capacity. The evidence suggests that the Global Fund has changed its conditions over time. Mozambique's 2002 Round 2 request for salary support for scaling up the numbers of health workers to deliver its TB control programme was rejected by the Fund (Starling et al . 2005b ). In contrast, in Malawi a Round 1 Global Fund grant was re-allocated 3 years later in 2005 to increase all health worker salaries, at the request of the government and other donors (Stillman and Bennett 2005 ).

Human resources for health: training

Early studies of the Global Fund anticipated adverse effects as ministries of health were under pressure to spend large amounts of money quickly, for example on training workshops, and health workers were relying on per diem allowances to supplement salaries (GFATM 2004 ; Brugha et al . 2005 ; Stillman and Bennett 2005 ). Most training focused largely on improving clinical skills, while planning and managerial skills, critical to successful implementation, were often neglected (McKinsey 2005 ; Stillman and Bennett 2005 ; Drew and Purvis 2006 ). In Benin, there were early missed opportunities to use Global Fund money to develop generic and transferable skills, such as management, monitoring and evaluation (Smith 2005 ).

In general, the increase in funding for training has been reported as a positive effect of GHIs. The Global Fund has allowed recipients to determine their own needs in capacity building (Oomman et al . 2007 ). In Ethiopia, the Global Fund supported the scale up training of multiple cadres, such as nurses, health officers, laboratory technicians and health extension workers (Banteyerga et al . 2005 ). In Benin, some Global Fund training provided skills transferable to disease programmes beyond the three focal diseases (Smith et al . 2005 ). PEPFAR typically supported capacity-building activities focused on training of existing personnel as an approach to addressing the shortage in human resources (Sepulveda et al . 2007 ). For example, in Uganda it funded the training of teachers to implement revised school curricula on HIV/AIDS and technical assistance for the district AIDS committees to generate HIV/AIDS strategic plans for the districts (Oomman et al . 2007 ). Oomman et al . ( 2007 ) reports that PEPFAR plans for 2008 would focus on building local capacity and a substantial amount of targets are focused on training new health workers.

The capacity-building activities of the World Bank's MAP have focused on national government, civil society organizations, district government and in particular on the community level; and have generally been seen as positive (Oomman et al . 2007 ). They have concentrated on management, administration, finance and implementation skills, although most involved short-term training. MAP was the first donor to channel a substantial amount of funding to the community level and build local capacity. In Zambia, key informants were positive about the community-response component of the MAP project (Oomman et al . 2007 ). More research is needed to determine the effect of these GHI-funded activities on human resource capacity and retention at the service delivery level in recipient countries.

Interpreting the evidence

This study has reviewed the literature on the effects of three GHIs on country health systems with respect to: 1) national policy; 2) coordination and planning; 3) stakeholder involvement; 4) disbursement, absorptive capacity and management; 5) monitoring & evaluation; and 6) human resources. This section discusses the major strengths and limitations of the quality of available evidence which is of importance when interpreting the results.

The major strength and rationale for this paper is that it has taken a systematic approach to selecting and reviewing the evidence of the health systems effects of specific GHIs in what has become a politically-charged arena. A recent review by Yu et al . ( 2008 ), on the effects on health systems of HIV/AIDS funding more generally, has cited press releases and GHI assertions, as well as commissioned evaluations, when attributing effects to GHI funding. Studies that look more broadly at the effects of increased funding to HIV/AIDS control are also less likely to shed light on the specific health systems effects and the particular strengths and weaknesses of different GHIs. The chapter by Brugha ( 2008 ) was not a systematic review and aimed to draw out the policy processes involved and policy lessons learned since the emergence of GHIs, rather than to review their effects on health systems. The framework that has been applied here is derived from early country experiences in managing GHIs, experiences that are not adequately captured in WHO's health systems building blocks frameworks (WHO 2007 ). The review provides an historical backdrop to forthcoming district-level studies; but also points to some chronic, refractory problems at the national level, which are inherent in the incentive systems underlying disease-specific initiatives.

Despite our systematic approach, the available evidence in this review has several limitations. First, most studies have focused on the national level, where GHI effects are initially felt. There was little empirical evidence (and much conjecture) regarding their effects at the district, facility and community levels. It is here that the strengths, weaknesses and added value (or not) of these still new, disease-specific initiatives will play out and will need to be assessed.

Secondly, with a few exceptions, most were descriptive studies with a cross-sectional design, which limits their capacity to demonstrate changes over time. GHIs have evolved and have sometimes been quite adept in learning and applying lessons, which has been more evident with the Global Fund than with PEPFAR. Rapid lesson-learning has meant that some study findings quickly become outdated or new problems supersede old ones.

Thirdly, not all GHIs and regions of the world have been studied equally. The Global Fund, because of its visibility and transparency, has been evaluated most often, whereas PEPFAR has remained the most opaque of these GHIs. Moreover, the limited empirical evidence on MAP, Global Fund and PEPFAR country-level effects relied heavily on evaluations conducted or commissioned by—or on behalf of—these initiatives, which may affect their validity. Most evidence is also based on studies conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, which is naturally the priority region for three HIV/AIDS-focused GHIs.

Lastly, mainly because this review relied heavily on unpublished reports (‘grey literature’), appraisal of the quality of data collection and interpretation was hampered by limited information on methods, quality control and analysis. Furthermore, the lack of consensus on appropriate criteria for assessing qualitative research (Dixon-Woods et al . 2004 ; Goldsmith et al . 2007 ) precluded us from making formal judgements on the quality of the studies.

This review has contributed to the surprisingly thin body of evidence regarding the health systems effects of three major GHIs. The systematic approach adopted has produced a series of findings that are of relevance to the current international debate on this issue. Based on the findings presented above, conclusions and recommendations are proposed that are relevant to national and international policy makers, donors, researchers and indeed civil society organizations.

Overall, the findings of this review of studies published between 2002 and 2007 suggest that the three GHIs initially often had negative effects, and later—as they learned lessons—more often positive effects on health systems. They also had different effects. From its outset, MAP was viewed positively for its capacity-building activities at national and district public-sector levels, and particularly at the community level. The Global Fund's particular strength has been in boosting the engagement of NGOs and faith-based bodies, bringing them into planning structures with government and enabling them to access significant funds. PEPFAR is well regarded for its fast and predictable disbursement of funding to civil society implementers.

At the level of national policy development , GHIs have generally made most progress in aligning with national joint strategic planning processes, while harmonization of activities with other partners has remained a challenge. Effects on other national health priorities, such as family planning and maternal care, were not reported and will require district and facility studies to assess effects at the service delivery level. While the Global Fund supported, with variable success, programmes that reflected local priorities and country ownership, PEPFAR's rigid budget allocations were more difficult to fit to a country's own priorities for health.

MAP's support to a multisectoral response has been most hindered by the weak capacity and lack of intersectorality of recipient country ministries, which supports the hypothesis that GHIs reveal rather than cause country systems weaknesses. Indeed, GHIs did not initially consider health systems strengthening to be part of their mandate but are now more willing to address systems weaknesses (Brugha et al . 2005 ; McKinsey 2005 ). This is all the more important now because, due to the rapid GHI-supported scaling up of HIV care and treatment in low income countries, HIV and AIDS are being transformed from an epidemic emergency to an endemic manageable chronic disease . As such, HIV control will require health systems that support continuity of care and the retention and follow up of patients with multiple and multi-systems diseases (El-Sadr and Abrams 2007 ).

Despite some positive developments, such as the integration of Global Fund support into some countries’ SWAps, donor harmonization activities have continued to fall short. While the vertical funding, planning and performance monitoring approaches that have characterized the GHIs could be seen as more efficient responses to tackling disease emergencies, these approaches created substantial barriers to harmonizing donor activities. They also reflected GHIs’ inherent need to demonstrate value for money through donor-specific measurements of performance. More recently, the GHIs have retreated from making claims of initiative-specific attributable successes (Brugha 2007 ; Gorgens-Albino et al . 2007 ), acknowledging the interplay of the many inputs and factors affecting programme implementation and service delivery. This was probably in response to the inherent difficulties of attribution in the complex multi-funded terrain of African health systems (Bennett et al . 2006 ). It also reflected a change in the global development assistance climate in the light of the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (OECD 2005 ).

However, it is at the national policy implementation level where the main early effects of GHIs—often negative at first and subsequently positive—have been encountered and documented. GHIs have led to multiple and parallel coordinating bodies , such as Global Fund CCMs, that have conflicted and sometimes contested with pre-existing bodies such as National AIDS Councils. Often, neither was providing the necessary leadership and oversight. Others, such as PEPFAR, established and continued to use parallel planning processes, inevitably pulling governments and other implementers away from other important activities because of the volume of funds at stake. However, positive effects have followed negative ones in that CCMs have enabled substantial improvements in stakeholder participation in the health sector. Through all three GHIs, NGOs and faith-based organizations have become direct recipients of significant levels of funding and thereby additional programme implementers. While there are great advantages to involving a greater diversity of actors, these new sources of funds have provoked real tensions in resource-starved settings between governments, as the traditional recipients of donor aid, and new civil society implementing organizations. Emerging evidence suggests that GHIs, which have been either geographically or ideologically detached from these concerns, have not done enough to help manage these tensions.

Where GHIs have been most retrograde has been in maintaining their own fiscal cycles, systems for auditing expenditure and GHI-specific reporting requirements. There have been gradual efforts to reduce transaction costs for countries. For example, the Global Fund has shown a willingness (in principle, at least) to adapt and align with country systems and directly fund countries’ national disease control plans, for example through ‘rolling continuation channels’ (GFATM 2007 ). However, it has continued to utilize a non-aligned Local Fund Agent model for financial management and audit (GFATM 2008b ). More recently, GHIs have started to work with countries in strengthening monitoring and evaluation systems and increasing local capacity, although this has mainly been for HIV/AIDS programmes and strengthening of the wider national health system has been neglected.

Finally, the effective implementation of GHI-supported programmes depends on human resources , which are recognized as the main bottleneck to scaling-up service delivery, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. There were credible, if anecdotal, early reports that different funding sources were competing for a limited pool of health workers by offering them incentives or higher salaries, which accelerated public sector staff leakage to non-government sectors. The combination of additional workload and remuneration constraints led to de-motivated and overburdened health workers in the public sector. One of the reasons was that GHI requirements in the early years, except to some extent MAP, precluded the funding of salaries for additional public sector health workers. Countries have also invested heavily in writing funding applications, whereas capacity for implementation of GHI-funded programmes has often been lacking. The early studies reviewed here suggest that the Global Fund and PEPFAR limited their human capacity-building activities to training existing health care workers, while MAP undertook a wider approach to capacity building at national and community levels. However, again, emerging evidence suggests that GHIs have been increasingly recognizing the importance of focusing attention on (and funding for) training and improving work and living conditions of health workers in rural areas as retention strategies.

The principal recommendation to GHIs, recipient donor countries, civil society organizations and technical agencies alike is to engage more fully with the Paris Principles for Aid Effectiveness as an important step in maximizing positive and minimizing negative effects of their programmes: Secondly, country and global policy makers and donors should demand and fund the acquisition of better evidence on what is a complex and rapidly evolving arena. What is now needed are coordinated evaluations using multiple methods in order to assess and understand the combined effects of GHIs and how they work alongside longer-standing disease-control financing mechanisms. Given the rapid learning of GHIs, which is often but not always applied, continuous monitoring and independent evaluations are needed to track changes and identify refractory problems. Early evaluations have been generally descriptive, necessary because of the rapid evolution in the GHI arena. Now, more analytical health policy and health systems evaluations are needed.

GHIs, which have signed up to these principles, could do much more to promote country ownership through aligning their objectives with comprehensive national health (rather than only HIV/AIDS) priorities.

Coordinated GHI investment to strengthen the capacity of national systems for financial management, M&E and reporting could thereby give GHIs the confidence to harmonize, align and use these systems.

There is an obvious need for stronger coordination of donor investments to support countries’ national strategic health plans, which can include flexibility to allow GHIs and other donors to support specific components of such plans.

GHIs should give recipient countries sufficient flexibility to address systems’ weaknesses and strengthen implementation capacity, especially in human resources at all levels.

Public sector health worker shortages, recognized as the key determinant for wide-ranging efforts to scale-up health-related priority interventions, should be addressed by GHIs through providing long-term funding for additional human resources for the health sector.

GHIs should continue to encourage the participation of non-government as well as government stakeholders, while reducing tensions created by funding new implementers in service delivery by requiring them, as far as possible, to utilize and contribute data to national information systems.

We believe this review of evidence on the early national effects of GHIs is timely, in advance of dissemination of findings in 2009 from the Global Fund Five Year Evaluation ( http://www.theglobalfund.org/en/about/terg/five_year_evaluation/ ), the Global HIV/AIDS Initiatives Network (GHIN – http://www.ghinet.org ) 3 and the recent WHO-launched initiative ‘Maximising Positive Synergies between health systems and GHIs’ (WHO 2008 ). Syntheses and interpretation of findings from these different evaluations—on a country-by-country basis—could provide invaluable lessons on how a much more complex mix of funding for disease control and health systems strengthening can work together in a complementary way to support country-led efforts to roll back the HIV and AIDS epidemic. They could also provide lessons for the establishment of effective long-term, comprehensive monitoring and evaluation systems.

Regien Biesma was funded under a 4-year research project grant, ‘GHIs in Africa’ (INCO-CT-2006-032371), funded by the EU 6th framework INCO-DEV programme. The INCO partners are based in three southern African countries (Angola, Mozambique and South Africa) and three European countries (Belgium, Ireland and Portugal). The authors would like to thank all partners who provided helpful comments on an earlier review of global health initiatives. Neil Spicer is funded under a grant from the Open Society Institute (OSI). Aisling Walsh is funded under the Global HIV/AIDS Initiatives Network (GHIN) grant, funded by Irish Aid and DANIDA. Ruairí Brugha and Gill Walt are co-coordinators of the GHIN network. Andrew Harmer was funded under a UK Department for International Development (DFID) grant to design a database on global health initiatives.

The authors acknowledge with appreciation financial support from the Open Society Institute to undertake research on global HIV/AIDS initiatives and their effects on health systems.

MAP was small relative to the total annual amounts provided by the Global Fund and PEPFAR, which had become the major external funder of HIV/AIDS control in sub-Saharan Africa by 2007 (Oomman et al . 2007 ). However, MAP was the first of these new GHIs for funding HIV/AIDS control, whose impact on countries’ health systems was experienced and reported across 2002–07.

Our initial review used the following Boolean string: (global health initiatives OR global health partnership OR public-private partnership OR Global Fund OR PEPFAR OR World Bank MAP) AND (HIV/AIDS) AND (effects OR national policy OR financial flow OR public-private partnerships OR planning and coordination OR implementation and monitoring and evaluation OR human resources).

The Global HIV/AIDS Initiatives Network (GHIN) is examining the effects and the inter-relationships of the three global health initiatives. GHIN has its origins in the Global Fund Tracking Study (2003–04), and in the SWEF studies (2005–06), which together provided several of the studies and papers reviewed.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

- acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

- delivery of health care

- world health

- human resource management

- president's emergency plan for aids relief

- nongovernmental organizations

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2237

- Copyright © 2024 The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

Advancing the Global Health Agenda

About the author, ilona kickbusch.

December 2011, No. 4 Vol. XLVIII, 7 Billion People, 1 United Nations, Hand in Hands

I n just over two decades, global health has gained a political visibility and status that some authors have called a political revolution. As health related issues have become a centre piece of the global agenda, significant resources in development aid have been made available to address major health problems. Global health has gained this political prominence because three agendas have reinforced one another in a variety of ways:

a security agenda driven by the fear of global pandemics or the intentional spread of disease, in an era where viruses have the potential to spread from one part of the world to another in a matter of hours;

an economic agenda, which is concerned not only with the economic impact of poor health on development or of pandemic outbreaks in the global marketplace, but increasingly considers the economic relevance of the health sector, in particular of certain industries, such as tobacco, food, and pharmaceuticals, and the growing global market of goods and services in relation to health;