Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

How to Write a Research Paper Introduction (with Examples)

The research paper introduction section, along with the Title and Abstract, can be considered the face of any research paper. The following article is intended to guide you in organizing and writing the research paper introduction for a quality academic article or dissertation.

The research paper introduction aims to present the topic to the reader. A study will only be accepted for publishing if you can ascertain that the available literature cannot answer your research question. So it is important to ensure that you have read important studies on that particular topic, especially those within the last five to ten years, and that they are properly referenced in this section. 1 What should be included in the research paper introduction is decided by what you want to tell readers about the reason behind the research and how you plan to fill the knowledge gap. The best research paper introduction provides a systemic review of existing work and demonstrates additional work that needs to be done. It needs to be brief, captivating, and well-referenced; a well-drafted research paper introduction will help the researcher win half the battle.

The introduction for a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your research topic

- Capture reader interest

- Summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Define your specific research problem and problem statement

- Highlight the novelty and contributions of the study

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The research paper introduction can vary in size and structure depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or is a review paper. Some research paper introduction examples are only half a page while others are a few pages long. In many cases, the introduction will be shorter than all of the other sections of your paper; its length depends on the size of your paper as a whole.

- Break through writer’s block. Write your research paper introduction with Paperpal Copilot

Table of Contents

What is the introduction for a research paper, why is the introduction important in a research paper, craft a compelling introduction section with paperpal. try now, 1. introduce the research topic:, 2. determine a research niche:, 3. place your research within the research niche:, craft accurate research paper introductions with paperpal. start writing now, frequently asked questions on research paper introduction, key points to remember.

The introduction in a research paper is placed at the beginning to guide the reader from a broad subject area to the specific topic that your research addresses. They present the following information to the reader

- Scope: The topic covered in the research paper

- Context: Background of your topic

- Importance: Why your research matters in that particular area of research and the industry problem that can be targeted

The research paper introduction conveys a lot of information and can be considered an essential roadmap for the rest of your paper. A good introduction for a research paper is important for the following reasons:

- It stimulates your reader’s interest: A good introduction section can make your readers want to read your paper by capturing their interest. It informs the reader what they are going to learn and helps determine if the topic is of interest to them.

- It helps the reader understand the research background: Without a clear introduction, your readers may feel confused and even struggle when reading your paper. A good research paper introduction will prepare them for the in-depth research to come. It provides you the opportunity to engage with the readers and demonstrate your knowledge and authority on the specific topic.

- It explains why your research paper is worth reading: Your introduction can convey a lot of information to your readers. It introduces the topic, why the topic is important, and how you plan to proceed with your research.

- It helps guide the reader through the rest of the paper: The research paper introduction gives the reader a sense of the nature of the information that will support your arguments and the general organization of the paragraphs that will follow. It offers an overview of what to expect when reading the main body of your paper.

What are the parts of introduction in the research?

A good research paper introduction section should comprise three main elements: 2

- What is known: This sets the stage for your research. It informs the readers of what is known on the subject.

- What is lacking: This is aimed at justifying the reason for carrying out your research. This could involve investigating a new concept or method or building upon previous research.

- What you aim to do: This part briefly states the objectives of your research and its major contributions. Your detailed hypothesis will also form a part of this section.

How to write a research paper introduction?

The first step in writing the research paper introduction is to inform the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening statement. The second step involves establishing the kinds of research that have been done and ending with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to address. Finally, the research paper introduction clarifies how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses. If your research involved testing hypotheses, these should be stated along with your research question. The hypothesis should be presented in the past tense since it will have been tested by the time you are writing the research paper introduction.

The following key points, with examples, can guide you when writing the research paper introduction section:

- Highlight the importance of the research field or topic

- Describe the background of the topic

- Present an overview of current research on the topic

Example: The inclusion of experiential and competency-based learning has benefitted electronics engineering education. Industry partnerships provide an excellent alternative for students wanting to engage in solving real-world challenges. Industry-academia participation has grown in recent years due to the need for skilled engineers with practical training and specialized expertise. However, from the educational perspective, many activities are needed to incorporate sustainable development goals into the university curricula and consolidate learning innovation in universities.

- Reveal a gap in existing research or oppose an existing assumption

- Formulate the research question

Example: There have been plausible efforts to integrate educational activities in higher education electronics engineering programs. However, very few studies have considered using educational research methods for performance evaluation of competency-based higher engineering education, with a focus on technical and or transversal skills. To remedy the current need for evaluating competencies in STEM fields and providing sustainable development goals in engineering education, in this study, a comparison was drawn between study groups without and with industry partners.

- State the purpose of your study

- Highlight the key characteristics of your study

- Describe important results

- Highlight the novelty of the study.

- Offer a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

Example: The study evaluates the main competency needed in the applied electronics course, which is a fundamental core subject for many electronics engineering undergraduate programs. We compared two groups, without and with an industrial partner, that offered real-world projects to solve during the semester. This comparison can help determine significant differences in both groups in terms of developing subject competency and achieving sustainable development goals.

Write a Research Paper Introduction in Minutes with Paperpal

Paperpal Copilot is a generative AI-powered academic writing assistant. It’s trained on millions of published scholarly articles and over 20 years of STM experience. Paperpal Copilot helps authors write better and faster with:

- Real-time writing suggestions

- In-depth checks for language and grammar correction

- Paraphrasing to add variety, ensure academic tone, and trim text to meet journal limits

With Paperpal Copilot, create a research paper introduction effortlessly. In this step-by-step guide, we’ll walk you through how Paperpal transforms your initial ideas into a polished and publication-ready introduction.

How to use Paperpal to write the Introduction section

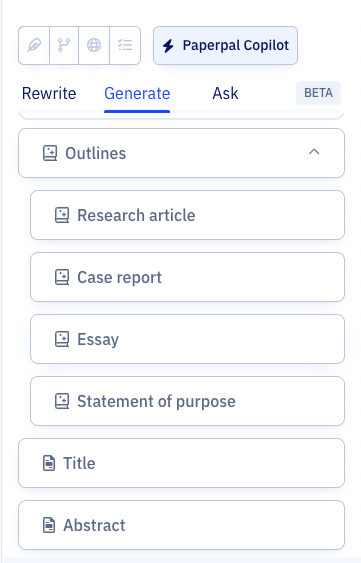

Step 1: Sign up on Paperpal and click on the Copilot feature, under this choose Outlines > Research Article > Introduction

Step 2: Add your unstructured notes or initial draft, whether in English or another language, to Paperpal, which is to be used as the base for your content.

Step 3: Fill in the specifics, such as your field of study, brief description or details you want to include, which will help the AI generate the outline for your Introduction.

Step 4: Use this outline and sentence suggestions to develop your content, adding citations where needed and modifying it to align with your specific research focus.

Step 5: Turn to Paperpal’s granular language checks to refine your content, tailor it to reflect your personal writing style, and ensure it effectively conveys your message.

You can use the same process to develop each section of your article, and finally your research paper in half the time and without any of the stress.

The purpose of the research paper introduction is to introduce the reader to the problem definition, justify the need for the study, and describe the main theme of the study. The aim is to gain the reader’s attention by providing them with necessary background information and establishing the main purpose and direction of the research.

The length of the research paper introduction can vary across journals and disciplines. While there are no strict word limits for writing the research paper introduction, an ideal length would be one page, with a maximum of 400 words over 1-4 paragraphs. Generally, it is one of the shorter sections of the paper as the reader is assumed to have at least a reasonable knowledge about the topic. 2 For example, for a study evaluating the role of building design in ensuring fire safety, there is no need to discuss definitions and nature of fire in the introduction; you could start by commenting upon the existing practices for fire safety and how your study will add to the existing knowledge and practice.

When deciding what to include in the research paper introduction, the rest of the paper should also be considered. The aim is to introduce the reader smoothly to the topic and facilitate an easy read without much dependency on external sources. 3 Below is a list of elements you can include to prepare a research paper introduction outline and follow it when you are writing the research paper introduction. Topic introduction: This can include key definitions and a brief history of the topic. Research context and background: Offer the readers some general information and then narrow it down to specific aspects. Details of the research you conducted: A brief literature review can be included to support your arguments or line of thought. Rationale for the study: This establishes the relevance of your study and establishes its importance. Importance of your research: The main contributions are highlighted to help establish the novelty of your study Research hypothesis: Introduce your research question and propose an expected outcome. Organization of the paper: Include a short paragraph of 3-4 sentences that highlights your plan for the entire paper

Cite only works that are most relevant to your topic; as a general rule, you can include one to three. Note that readers want to see evidence of original thinking. So it is better to avoid using too many references as it does not leave much room for your personal standpoint to shine through. Citations in your research paper introduction support the key points, and the number of citations depend on the subject matter and the point discussed. If the research paper introduction is too long or overflowing with citations, it is better to cite a few review articles rather than the individual articles summarized in the review. A good point to remember when citing research papers in the introduction section is to include at least one-third of the references in the introduction.

The literature review plays a significant role in the research paper introduction section. A good literature review accomplishes the following: Introduces the topic – Establishes the study’s significance – Provides an overview of the relevant literature – Provides context for the study using literature – Identifies knowledge gaps However, remember to avoid making the following mistakes when writing a research paper introduction: Do not use studies from the literature review to aggressively support your research Avoid direct quoting Do not allow literature review to be the focus of this section. Instead, the literature review should only aid in setting a foundation for the manuscript.

Remember the following key points for writing a good research paper introduction: 4

- Avoid stuffing too much general information: Avoid including what an average reader would know and include only that information related to the problem being addressed in the research paper introduction. For example, when describing a comparative study of non-traditional methods for mechanical design optimization, information related to the traditional methods and differences between traditional and non-traditional methods would not be relevant. In this case, the introduction for the research paper should begin with the state-of-the-art non-traditional methods and methods to evaluate the efficiency of newly developed algorithms.

- Avoid packing too many references: Cite only the required works in your research paper introduction. The other works can be included in the discussion section to strengthen your findings.

- Avoid extensive criticism of previous studies: Avoid being overly critical of earlier studies while setting the rationale for your study. A better place for this would be the Discussion section, where you can highlight the advantages of your method.

- Avoid describing conclusions of the study: When writing a research paper introduction remember not to include the findings of your study. The aim is to let the readers know what question is being answered. The actual answer should only be given in the Results and Discussion section.

To summarize, the research paper introduction section should be brief yet informative. It should convince the reader the need to conduct the study and motivate him to read further. If you’re feeling stuck or unsure, choose trusted AI academic writing assistants like Paperpal to effortlessly craft your research paper introduction and other sections of your research article.

1. Jawaid, S. A., & Jawaid, M. (2019). How to write introduction and discussion. Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia, 13(Suppl 1), S18.

2. Dewan, P., & Gupta, P. (2016). Writing the title, abstract and introduction: Looks matter!. Indian pediatrics, 53, 235-241.

3. Cetin, S., & Hackam, D. J. (2005). An approach to the writing of a scientific Manuscript1. Journal of Surgical Research, 128(2), 165-167.

4. Bavdekar, S. B. (2015). Writing introduction: Laying the foundations of a research paper. Journal of the Association of Physicians of India, 63(7), 44-6.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

Practice vs. Practise: Learn the Difference

Academic paraphrasing: why paperpal’s rewrite should be your first choice , you may also like, ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , should you use ai tools like chatgpt for..., publish research papers: 9 steps for successful publications , what are the different types of research papers, how to make translating academic papers less challenging, self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how....

How to Start a Methods Section in Research? [with Examples]

The examples below are from 76,350 full-text PubMed research papers that I analyzed in order to explore common ways to start the Materials and Methods section.

Research papers included in this analysis were selected at random from those uploaded to PubMed Central between the years 2016 and 2021. I used the BioC API to download the data (see the References section below).

Examples of how to start writing the Methods section

The Methods section is the recipe for the study: it should provide the reader enough information to replicate the study without looking elsewhere. [for more information, see: How to Write & Publish a Research Paper: Step-by-Step Guide ]

The Methods section can:

1. Start by mentioning the approvals acquired to conduct the study

For example:

“ The study protocol was approved by the institutional research commissions of the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute (Swiss TPH; Basel, Switzerland) and the Centre Suisse de Recherches Scientifiques en Côte d’Ivoire (CSRS; Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire). Ethical approval was granted by the ethics committee of Basel (EKBB; reference no. 316/08), and the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research in Côte d’Ivoire (reference no. 124/MESRS/DGRSIT/YKS/sac).” Source: taken from the Methods section of this PubMed article

2. Start by mentioning the study design

“This cross-sectional study was performed among students and staff of one of the largest government-funded universities in Malaysia.” Source: taken from the Methods section of this PubMed article

3. Start by mentioning the date, duration, and place of the study

“This cross-sectional study was a part of the Student Mental Health Survey that was conducted at Akita University between May 20 and June 16, 2020 .” Source: taken from the Methods section of this PubMed article

4. Start by mentioning the source of the data

“ This study used three datasets from the 2007, 2013–14, and 2018 Zambian Demographic Health Surveys (DHS).” Source: taken from the Methods section of this PubMed article

5. Start by mentioning the sample size

“Data were acquired on 30 patients with schizophrenia and 30 healthy controls .” Source: taken from the Methods section of this PubMed article

6. Start by justifying the use of the main material or method

“ In order to describe the infectious disease progression we use the minimal and prototypical SIR model.” Source: taken from the Methods section of this PubMed article

Common words used to start a Methods section

Here’s a list of the most common words used at the beginning of the Methods section:

- “This study was approved by…”

- “This study was conducted at…”

- “This was a retrospective study…”

- “This cross-sectional study was conducted…”

- “This study was conducted in accordance…”

- “This study was performed in accordance…”

- “All procedures were approved by the…”

- “Written informed consent was obtained from…”

- Comeau DC, Wei CH, Islamaj Doğan R, and Lu Z. PMC text mining subset in BioC: about 3 million full text articles and growing, Bioinformatics , btz070, 2019.

Further reading

- How Long Should the Methods Section Be? Data from 61,514 Examples

- How to Write & Publish a Research Paper: Step-by-Step Guide

- Does the Number of Authors Matter? Data from 101,580 Research Papers

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Methods Section for a Research Paper

A common piece of advice for authors preparing their first journal article for publication is to start with the methods section: just list everything that was done and go from there. While that might seem like a very practical approach to a first draft, if you do this without a clear outline and a story in mind, you can easily end up with journal manuscript sections that are not logically related to each other.

Since the methods section constitutes the core of your paper, no matter when you write it, you need to use it to guide the reader carefully through your story from beginning to end without leaving questions unanswered. Missing or confusing details in this section will likely lead to early rejection of your manuscript or unnecessary back-and-forth with the reviewers until eventual publication. Here, you will find some useful tips on how to make your methods section the logical foundation of your research paper.

Not just a list of experiments and methods

While your introduction section provides the reader with the necessary background to understand your rationale and research question (and, depending on journal format and your personal preference, might already summarize the results), the methods section explains what exactly you did and how you did it. The point of this section is not to list all the boring details just for the sake of completeness. The purpose of the methods sections is to enable the reader to replicate exactly what you did, verify or corroborate your results, or maybe find that there are factors you did not consider or that are more relevant than expected.

To make this section as easy to read as possible, you must clearly connect it to the information you provide in the introduction section before and the results section after, it needs to have a clear structure (chronologically or according to topics), and you need to present your results according to the same structure or topics later in the manuscript. There are also official guidelines and journal instructions to follow and ethical issues to avoid to ensure that your manuscript can quickly reach the publication stage.

Table of Contents:

- General Methods Structure: What is Your Story?

- What Methods Should You Report (and Leave Out)?

- Details Frequently Missing from the Methods Section

More Journal Guidelines to Consider

- Accurate and Appropriate Language in the Methods

General Methods Section Structure: What Is Your Story?

You might have conducted a number of experiments, maybe also a pilot before the main study to determine some specific factors or a follow-up experiment to clarify unclear details later in the process. Throwing all of these into your methods section, however, might not help the reader understand how everything is connected and how useful and appropriate your methodological approach is to investigate your specific research question. You therefore need to first come up with a clear outline and decide what to report and how to present that to the reader.

The first (and very important) decision to make is whether you present your experiments chronologically (e.g., Experiment 1, Experiment 2, Experiment 3… ), and guide the reader through every step of the process, or if you organize everything according to subtopics (e.g., Behavioral measures, Structural imaging markers, Functional imaging markers… ). In both cases, you need to use clear subheaders for the different subsections of your methods, and, very importantly, follow the same structure or focus on the same topics/measures in the results section so that the reader can easily follow along (see the two examples below).

If you are in doubt which way of organizing your experiments is better for your study, just ask yourself the following questions:

- Does the reader need to know the timeline of your study?

- Is it relevant that one experiment was conducted first, because the outcome of this experiment determined the stimuli or factors that went into the next?

- Did the results of your first experiment leave important questions open that you addressed in an additional experiment (that was maybe not planned initially)?

- Is the answer to all of these questions “no”? Then organizing your methods section according to topics of interest might be the more logical choice.

If you think your timeline, protocol, or setup might be confusing or difficult for the reader to grasp, consider adding a graphic, flow diagram, decision tree, or table as a visual aid.

What Methods Should You Report (and Leave Out)?

The answer to this question is quite simple–you need to report everything that another researcher needs to know to be able to replicate your study. Just imagine yourself reading your methods section in the future and trying to set up the same experiments again without prior knowledge. You would probably need to ask questions such as:

- Where did you conduct your experiments (e.g., in what kind of room, under what lighting or temperature conditions, if those are relevant)?

- What devices did you use? Are there specific settings to report?

- What specific software (and version of that software) did you use?

- How did you find and select your participants?

- How did you assign participants into groups?

- Did you exclude participants from the analysis? Why and how?

- Where did your reagents or antibodies come from? Can you provide a Research Resource Identifier (RRID) ?

- Did you make your stimuli yourself or did you get them from somewhere?

- Are the stimuli you used available for other researchers?

- What kind of questionnaires did you use? Have they been validated?

- How did you analyze your data? What level of significance did you use?

- Were there any technical issues and did you have to adjust protocols?

Note that for every experimental detail you provide, you need to tell the reader (briefly) why you used this type of stimulus/this group of participants/these specific amounts of reagents. If there is earlier published research reporting the same methods, cite those studies. If you did pilot experiments to determine those details, describe the procedures and the outcomes of these experiments. If you made assumptions about the suitability of something based on the literature and common practice at your institution, then explain that to the reader.

In a nutshell, established methods need to be cited, and new methods need to be clearly described and briefly justified. However, if the fact that you use a new approach or a method that is not traditionally used for the data or phenomenon you study is one of the main points of your study (and maybe already reflected in the title of your article), then you need to explain your rationale for doing so in the introduction already and discuss it in more detail in the discussion section .

Note that you also need to explain your statistical analyses at the end of your methods section. You present the results of these analyses later, in the results section of your paper, but you need to show the reader in the methods section already that your approach is either well-established or valid, even if it is new or unusual.

When it comes to the question of what details you should leave out, the answer is equally simple ‒ everything that you would not need to replicate your study in the future. If the educational background of your participants is listed in your institutional database but is not relevant to your study outcome, then don’t include that. Other things you should not include in the methods section:

- Background information that you already presented in the introduction section.

- In-depth comparisons of different methods ‒ these belong in the discussion section.

- Results, unless you summarize outcomes of pilot experiments that helped you determine factors for your main experiment.

Also, make sure your subheadings are as clear as possible, suit the structure you chose for your methods section, and are in line with the target journal guidelines. If you studied a disease intervention in human participants, then your methods section could look similar to this:

Since the main point of interest here are your patient-centered outcome variables, you would center your results section on these as well and choose your headers accordingly (e.g., Patient characteristics, Baseline evaluation, Outcome variable 1, Outcome variable 2, Drop-out rate ).

If, instead, you did a series of visual experiments investigating the perception of faces including a pilot experiment to create the stimuli for your actual study, you would need to structure your methods section in a very different way, maybe like this:

Since here the analysis and outcome of the pilot experiment are already described in the methods section (as the basis for the main experimental setup and procedure), you do not have to mention it again in the results section. Instead, you could choose the two main experiments to structure your results section ( Discrimination and classification, Familiarization and adaptation ), or divide the results into all your test measures and/or potential interactions you described in the methods section (e.g., Discrimination performance, Classification performance, Adaptation aftereffects, Correlation analysis ).

Details Commonly Missing from the Methods Section

Manufacturer information.

For laboratory or technical equipment, you need to provide the model, name of the manufacturer, and company’s location. The usual format for these details is the product name (company name, city, state) for US-based manufacturers and the product name (company name, city/town, country) for companies outside the US.

Sample size and power estimation

Power and sample size estimations are measures for how many patients or participants are needed in a study in order to detect statistical significance and draw meaningful conclusions from the results. Outside of the medical field, studies are sometimes still conducted with a “the more the better” approach in mind, but since many journals now ask for those details, it is better to not skip this important step.

Ethical guidelines and approval

In addition to describing what you did, you also need to assure the editor and reviewers that your methods and protocols followed all relevant ethical standards and guidelines. This includes applying for approval at your local or national ethics committee, providing the name or location of that committee as well as the approval reference number you received, and, if you studied human participants, a statement that participants were informed about all relevant experimental details in advance and signed consent forms before the start of the study. For animal studies, you usually need to provide a statement that all procedures included in your research were in line with the Declaration of Helsinki. Make sure you check the target journal guidelines carefully, as these statements sometimes need to be placed at the end of the main article text rather than in the method section.

Structure & word limitations

While many journals simply follow the usual style guidelines (e.g., APA for the social sciences and psychology, AMA for medical research) and let you choose the headers of your method section according to your preferred structure and focus, some have precise guidelines and strict limitations, for example, on manuscript length and the maximum number of subsections or header levels. Make sure you read the instructions of your target journal carefully and restructure your method section if necessary before submission. If the journal does not give you enough space to include all the details that you deem necessary, then you can usually submit additional details as “supplemental” files and refer to those in the main text where necessary.

Standardized checklists

In addition to ethical guidelines and approval, journals also often ask you to submit one of the official standardized checklists for different study types to ensure all essential details are included in your manuscript. For example, there are checklists for randomized clinical trials, CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) , cohort, case-control, cross‐sectional studies, STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology ), diagnostic accuracy, STARD (STAndards for the Reporting of Diagnostic accuracy studies) , systematic reviews and meta‐analyses PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses) , and Case reports, CARE (CAse REport) .

Make sure you check if the manuscript uses a single- or double-blind review procedure , and delete all information that might allow a reviewer to guess where the authors are located from the manuscript text if necessary. This means that your method section cannot list the name and location of your institution, the names of researchers who conducted specific tests, or the name of your institutional ethics committee.

Accurate and Appropriate Language in the Methods Section

Like all sections of your research paper, your method section needs to be written in an academic tone . That means it should be formal, vague expressions and colloquial language need to be avoided, and you need to correctly cite all your sources. If you describe human participants in your method section then you should be especially careful about your choice of words. For example, “participants” sounds more respectful than “subjects,” and patient-first language, that is, “patients with cancer,” is considered more appropriate than “cancer patients” by many journals.

Passive voice is often considered the standard for research papers, but it is completely fine to mix passive and active voice, even in the method section, to make your text as clear and concise as possible. Use the simple past tense to describe what you did, and the present tense when you refer to diagrams or tables. Have a look at this article if you need more general input on which verb tenses to use in a research paper .

Lastly, make sure you label all the standard tests and questionnaires you use correctly (look up the original publication when in doubt) and spell genes and proteins according to the common databases for the species you studied, such as the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee database for human studies .

Visit Wordvice AI’s AI Text Editor to receive a free grammar check and English editing services (including manuscript editing , paper editing , and dissertation editing ) before submitting your manuscript to journal editors.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write a Methods Section for a Psychology Paper

Tips and Examples of an APA Methods Section

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

Verywell / Brianna Gilmartin

The methods section of an APA format psychology paper provides the methods and procedures used in a research study or experiment . This part of an APA paper is critical because it allows other researchers to see exactly how you conducted your research.

Method refers to the procedure that was used in a research study. It included a precise description of how the experiments were performed and why particular procedures were selected. While the APA technically refers to this section as the 'method section,' it is also often known as a 'methods section.'

The methods section ensures the experiment's reproducibility and the assessment of alternative methods that might produce different results. It also allows researchers to replicate the experiment and judge the study's validity.

This article discusses how to write a methods section for a psychology paper, including important elements to include and tips that can help.

What to Include in a Method Section

So what exactly do you need to include when writing your method section? You should provide detailed information on the following:

- Research design

- Participants

- Participant behavior

The method section should provide enough information to allow other researchers to replicate your experiment or study.

Components of a Method Section

The method section should utilize subheadings to divide up different subsections. These subsections typically include participants, materials, design, and procedure.

Participants

In this part of the method section, you should describe the participants in your experiment, including who they were (and any unique features that set them apart from the general population), how many there were, and how they were selected. If you utilized random selection to choose your participants, it should be noted here.

For example: "We randomly selected 100 children from elementary schools near the University of Arizona."

At the very minimum, this part of your method section must convey:

- Basic demographic characteristics of your participants (such as sex, age, ethnicity, or religion)

- The population from which your participants were drawn

- Any restrictions on your pool of participants

- How many participants were assigned to each condition and how they were assigned to each group (i.e., randomly assignment , another selection method, etc.)

- Why participants took part in your research (i.e., the study was advertised at a college or hospital, they received some type of incentive, etc.)

Information about participants helps other researchers understand how your study was performed, how generalizable the result might be, and allows other researchers to replicate the experiment with other populations to see if they might obtain the same results.

In this part of the method section, you should describe the materials, measures, equipment, or stimuli used in the experiment. This may include:

- Testing instruments

- Technical equipment

- Any psychological assessments that were used

- Any special equipment that was used

For example: "Two stories from Sullivan et al.'s (1994) second-order false belief attribution tasks were used to assess children's understanding of second-order beliefs."

For standard equipment such as computers, televisions, and videos, you can simply name the device and not provide further explanation.

Specialized equipment should be given greater detail, especially if it is complex or created for a niche purpose. In some instances, such as if you created a special material or apparatus for your study, you might need to include an illustration of the item in the appendix of your paper.

In this part of your method section, describe the type of design used in the experiment. Specify the variables as well as the levels of these variables. Identify:

- The independent variables

- Dependent variables

- Control variables

- Any extraneous variables that might influence your results.

Also, explain whether your experiment uses a within-groups or between-groups design.

For example: "The experiment used a 3x2 between-subjects design. The independent variables were age and understanding of second-order beliefs."

The next part of your method section should detail the procedures used in your experiment. Your procedures should explain:

- What the participants did

- How data was collected

- The order in which steps occurred

For example: "An examiner interviewed children individually at their school in one session that lasted 20 minutes on average. The examiner explained to each child that he or she would be told two short stories and that some questions would be asked after each story. All sessions were videotaped so the data could later be coded."

Keep this subsection concise yet detailed. Explain what you did and how you did it, but do not overwhelm your readers with too much information.

Tips for How to Write a Methods Section

In addition to following the basic structure of an APA method section, there are also certain things you should remember when writing this section of your paper. Consider the following tips when writing this section:

- Use the past tense : Always write the method section in the past tense.

- Be descriptive : Provide enough detail that another researcher could replicate your experiment, but focus on brevity. Avoid unnecessary detail that is not relevant to the outcome of the experiment.

- Use an academic tone : Use formal language and avoid slang or colloquial expressions. Word choice is also important. Refer to the people in your experiment or study as "participants" rather than "subjects."

- Use APA format : Keep a style guide on hand as you write your method section. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association is the official source for APA style.

- Make connections : Read through each section of your paper for agreement with other sections. If you mention procedures in the method section, these elements should be discussed in the results and discussion sections.

- Proofread : Check your paper for grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors.. typos, grammar problems, and spelling errors. Although a spell checker is a handy tool, there are some errors only you can catch.

After writing a draft of your method section, be sure to get a second opinion. You can often become too close to your work to see errors or lack of clarity. Take a rough draft of your method section to your university's writing lab for additional assistance.

A Word From Verywell

The method section is one of the most important components of your APA format paper. The goal of your paper should be to clearly detail what you did in your experiment. Provide enough detail that another researcher could replicate your study if they wanted.

Finally, if you are writing your paper for a class or for a specific publication, be sure to keep in mind any specific instructions provided by your instructor or by the journal editor. Your instructor may have certain requirements that you need to follow while writing your method section.

Frequently Asked Questions

While the subsections can vary, the three components that should be included are sections on the participants, the materials, and the procedures.

- Describe who the participants were in the study and how they were selected.

- Define and describe the materials that were used including any equipment, tests, or assessments

- Describe how the data was collected

To write your methods section in APA format, describe your participants, materials, study design, and procedures. Keep this section succinct, and always write in the past tense. The main heading of this section should be labeled "Method" and it should be centered, bolded, and capitalized. Each subheading within this section should be bolded, left-aligned and in title case.

The purpose of the methods section is to describe what you did in your experiment. It should be brief, but include enough detail that someone could replicate your experiment based on this information. Your methods section should detail what you did to answer your research question. Describe how the study was conducted, the study design that was used and why it was chosen, and how you collected the data and analyzed the results.

Erdemir F. How to write a materials and methods section of a scientific article ? Turk J Urol . 2013;39(Suppl 1):10-5. doi:10.5152/tud.2013.047

Kallet RH. How to write the methods section of a research paper . Respir Care . 2004;49(10):1229-32. PMID: 15447808.

American Psychological Association. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). Washington DC: The American Psychological Association; 2019.

American Psychological Association. APA Style Journal Article Reporting Standards . Published 2020.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- SpringerLink shop

Introduction, Methods and Results

Introduction.

The Introduction should provide readers with the background information needed to understand your study, and the reasons why you conducted your experiments. The Introduction should answer the question: what question/problem was studied?

While writing the background, make sure your citations are:

- Well balanced: If experiments have found conflicting results on a question, have you cited studies with both kinds of results?

- Current: Every field is different, but you should aim to cite references that are not more than 10 years old if possible. Although be sure to cite the first discovery or mention in the literature even if it older than 10 years.

- Relevant: This is the most important requirement. The studies you cite should be strongly related to your research question.

TIP: Do not write a literature review in your Introduction, but do cite reviews where readers can find more information if they want it.

Once you have provided background material and stated the problem or question for your study, tell the reader the purpose of your study. Usually the reason is to fill a gap in the knowledge or to answer a previously unanswered question. For example, if a drug is known to work well in one population, but has never been tested in a different population, the purpose of a study could be to test the efficacy and safety of the drug in the second population.

The final thing to include at the end of your Introduction is a clear and exact statement of your study aims. You might also explain in a sentence or two how you conducted the study.

Materials and Methods

This section provides the reader with all the details of how you conducted your study. You should:

- Use subheadings to separate different methodologies

- Describe what you did in the past tense

- Describe new methods in enough detail that another researcher can reproduce your experiment

- Describe established methods briefly, and simply cite a reference where readers can find more detail

- State all statistical tests and parameters

TIP: Check the ‘Instructions for Authors’ for your target journal to see how manuscripts should present the Materials and Methods. Also, as another guide, look at previously published papers in the journal or sample reports on the journal website.

In the Results section, simply state what you found, but do not interpret the results or discuss their implications.

- As in the Materials and Methods section, use subheadings to separate the results of different experiments.

- Results should be presented in a logical order . In general this will be in order of importance, not necessarily the order in which the experiments were performed. Use the past tense to describe your results; however, refer to figures and tables in the present tense.

- Do not duplicate data among figures, tables, and text. A common mistake is to re-state much of the data from a table in the text of the manuscript. Instead, use the text to summarize what the reader will find in the table, or mention one or two of the most important data points. It is usually much easier to read data in a table than in the text.

- Include the results of statistical analyses in the text, usually by providing p values wherever statistically significant differences are described.

TIP: There is a famous saying in English: “A picture is worth a thousand words.” This means that, sometimes, an image can explain your findings far better than text could. So make good use of figures and tables in your manuscript! However, avoid including redundant figures and tables (e.g. two showing the same thing in a different format), or using figures and tables where it would be better to just include the information in the text (e.g. where there is not enough data for a table or figure).

Back │ Next

How to write an effective introduction for your research paper

Last updated

20 January 2024

Reviewed by

However, the introduction is a vital element of your research paper. It helps the reader decide whether your paper is worth their time. As such, it's worth taking your time to get it right.

In this article, we'll tell you everything you need to know about writing an effective introduction for your research paper.

- The importance of an introduction in research papers

The primary purpose of an introduction is to provide an overview of your paper. This lets readers gauge whether they want to continue reading or not. The introduction should provide a meaningful roadmap of your research to help them make this decision. It should let readers know whether the information they're interested in is likely to be found in the pages that follow.

Aside from providing readers with information about the content of your paper, the introduction also sets the tone. It shows readers the style of language they can expect, which can further help them to decide how far to read.

When you take into account both of these roles that an introduction plays, it becomes clear that crafting an engaging introduction is the best way to get your paper read more widely. First impressions count, and the introduction provides that impression to readers.

- The optimum length for a research paper introduction

While there's no magic formula to determine exactly how long a research paper introduction should be, there are a few guidelines. Some variables that impact the ideal introduction length include:

Field of study

Complexity of the topic

Specific requirements of the course or publication

A commonly recommended length of a research paper introduction is around 10% of the total paper’s length. So, a ten-page paper has a one-page introduction. If the topic is complex, it may require more background to craft a compelling intro. Humanities papers tend to have longer introductions than those of the hard sciences.

The best way to craft an introduction of the right length is to focus on clarity and conciseness. Tell the reader only what is necessary to set up your research. An introduction edited down with this goal in mind should end up at an acceptable length.

- Evaluating successful research paper introductions

A good way to gauge how to create a great introduction is by looking at examples from across your field. The most influential and well-regarded papers should provide some insights into what makes a good introduction.

Dissecting examples: what works and why

We can make some general assumptions by looking at common elements of a good introduction, regardless of the field of research.

A common structure is to start with a broad context, and then narrow that down to specific research questions or hypotheses. This creates a funnel that establishes the scope and relevance.

The most effective introductions are careful about the assumptions they make regarding reader knowledge. By clearly defining key terms and concepts instead of assuming the reader is familiar with them, these introductions set a more solid foundation for understanding.

To pull in the reader and make that all-important good first impression, excellent research paper introductions will often incorporate a compelling narrative or some striking fact that grabs the reader's attention.

Finally, good introductions provide clear citations from past research to back up the claims they're making. In the case of argumentative papers or essays (those that take a stance on a topic or issue), a strong thesis statement compels the reader to continue reading.

Common pitfalls to avoid in research paper introductions

You can also learn what not to do by looking at other research papers. Many authors have made mistakes you can learn from.

We've talked about the need to be clear and concise. Many introductions fail at this; they're verbose, vague, or otherwise fail to convey the research problem or hypothesis efficiently. This often comes in the form of an overemphasis on background information, which obscures the main research focus.

Ensure your introduction provides the proper emphasis and excitement around your research and its significance. Otherwise, fewer people will want to read more about it.

- Crafting a compelling introduction for a research paper

Let’s take a look at the steps required to craft an introduction that pulls readers in and compels them to learn more about your research.

Step 1: Capturing interest and setting the scene

To capture the reader's interest immediately, begin your introduction with a compelling question, a surprising fact, a provocative quote, or some other mechanism that will hook readers and pull them further into the paper.

As they continue reading, the introduction should contextualize your research within the current field, showing readers its relevance and importance. Clarify any essential terms that will help them better understand what you're saying. This keeps the fundamentals of your research accessible to all readers from all backgrounds.

Step 2: Building a solid foundation with background information

Including background information in your introduction serves two major purposes:

It helps to clarify the topic for the reader

It establishes the depth of your research

The approach you take when conveying this information depends on the type of paper.

For argumentative papers, you'll want to develop engaging background narratives. These should provide context for the argument you'll be presenting.

For empirical papers, highlighting past research is the key. Often, there will be some questions that weren't answered in those past papers. If your paper is focused on those areas, those papers make ideal candidates for you to discuss and critique in your introduction.

Step 3: Pinpointing the research challenge

To capture the attention of the reader, you need to explain what research challenges you'll be discussing.

For argumentative papers, this involves articulating why the argument you'll be making is important. What is its relevance to current discussions or problems? What is the potential impact of people accepting or rejecting your argument?

For empirical papers, explain how your research is addressing a gap in existing knowledge. What new insights or contributions will your research bring to your field?

Step 4: Clarifying your research aims and objectives

We mentioned earlier that the introduction to a research paper can serve as a roadmap for what's within. We've also frequently discussed the need for clarity. This step addresses both of these.

When writing an argumentative paper, craft a thesis statement with impact. Clearly articulate what your position is and the main points you intend to present. This will map out for the reader exactly what they'll get from reading the rest.

For empirical papers, focus on formulating precise research questions and hypotheses. Directly link them to the gaps or issues you've identified in existing research to show the reader the precise direction your research paper will take.

Step 5: Sketching the blueprint of your study

Continue building a roadmap for your readers by designing a structured outline for the paper. Guide the reader through your research journey, explaining what the different sections will contain and their relationship to one another.

This outline should flow seamlessly as you move from section to section. Creating this outline early can also help guide the creation of the paper itself, resulting in a final product that's better organized. In doing so, you'll craft a paper where each section flows intuitively from the next.

Step 6: Integrating your research question

To avoid letting your research question get lost in background information or clarifications, craft your introduction in such a way that the research question resonates throughout. The research question should clearly address a gap in existing knowledge or offer a new perspective on an existing problem.

Tell users your research question explicitly but also remember to frequently come back to it. When providing context or clarification, point out how it relates to the research question. This keeps your focus where it needs to be and prevents the topic of the paper from becoming under-emphasized.

Step 7: Establishing the scope and limitations

So far, we've talked mostly about what's in the paper and how to convey that information to readers. The opposite is also important. Information that's outside the scope of your paper should be made clear to the reader in the introduction so their expectations for what is to follow are set appropriately.

Similarly, be honest and upfront about the limitations of the study. Any constraints in methodology, data, or how far your findings can be generalized should be fully communicated in the introduction.

Step 8: Concluding the introduction with a promise

The final few lines of the introduction are your last chance to convince people to continue reading the rest of the paper. Here is where you should make it very clear what benefit they'll get from doing so. What topics will be covered? What questions will be answered? Make it clear what they will get for continuing.

By providing a quick recap of the key points contained in the introduction in its final lines and properly setting the stage for what follows in the rest of the paper, you refocus the reader's attention on the topic of your research and guide them to read more.

- Research paper introduction best practices

Following the steps above will give you a compelling introduction that hits on all the key points an introduction should have. Some more tips and tricks can make an introduction even more polished.

As you follow the steps above, keep the following tips in mind.

Set the right tone and style

Like every piece of writing, a research paper should be written for the audience. That is to say, it should match the tone and style that your academic discipline and target audience expect. This is typically a formal and academic tone, though the degree of formality varies by field.

Kno w the audience

The perfect introduction balances clarity with conciseness. The amount of clarification required for a given topic depends greatly on the target audience. Knowing who will be reading your paper will guide you in determining how much background information is required.

Adopt the CARS (create a research space) model

The CARS model is a helpful tool for structuring introductions. This structure has three parts. The beginning of the introduction establishes the general research area. Next, relevant literature is reviewed and critiqued. The final section outlines the purpose of your study as it relates to the previous parts.

Master the art of funneling

The CARS method is one example of a well-funneled introduction. These start broadly and then slowly narrow down to your specific research problem. It provides a nice narrative flow that provides the right information at the right time. If you stray from the CARS model, try to retain this same type of funneling.

Incorporate narrative element

People read research papers largely to be informed. But to inform the reader, you have to hold their attention. A narrative style, particularly in the introduction, is a great way to do that. This can be a compelling story, an intriguing question, or a description of a real-world problem.

Write the introduction last

By writing the introduction after the rest of the paper, you'll have a better idea of what your research entails and how the paper is structured. This prevents the common problem of writing something in the introduction and then forgetting to include it in the paper. It also means anything particularly exciting in the paper isn’t neglected in the intro.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Turk J Urol

- v.39(Suppl 1); 2013 Sep

How to write an introduction section of a scientific article?

An article primarily includes the following sections: introduction, materials and methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Before writing the introduction, the main steps, the heading and the familiarity level of the readers should be considered. Writing should begin when the experimental system and the equipment are available. The introduction section comprises the first portion of the manuscript, and it should be written using the simple present tense. Additionally, abbreviations and explanations are included in this section. The main goal of the introduction is to convey basic information to the readers without obligating them to investigate previous publications and to provide clues as to the results of the present study. To do this, the subject of the article should be thoroughly reviewed, and the aim of the study should be clearly stated immediately after discussing the basic references. In this review, we aim to convey the principles of writing the introduction section of a manuscript to residents and young investigators who have just begun to write a manuscript.

Introduction

When entering a gate of a magnificent city we can make a prediction about the splendor, pomposity, history, and civilization we will encounter in the city. Occasionally, gates do not give even a glimpse of the city, and it can mislead the visitors about inner sections of the city. Introduction sections of the articles are like gates of a city. It is a presentation aiming at introducing itself to the readers, and attracting their attention. Attractiveness, clarity, piquancy, and analytical capacity of the presentation will urge the reader to read the subsequent sections of the article. On the other hand as is understood from the motto of antique Greek poet Euripides “a bad beginning makes a bad ending”, ‘Introduction’ section of a scientific article is important in that it can reveal the conclusion of the article. [ 1 ]

It is useful to analyze the issues to be considered in the ‘Introduction’ section under 3 headings. Firstly, information should be provided about the general topic of the article in the light of the current literature which paves the way for the disclosure of the objective of the manuscript. Then the specific subject matter, and the issue to be focused on should be dealt with, the problem should be brought forth, and fundamental references related to the topic should be discussed. Finally, our recommendations for solution should be described, in other words our aim should be communicated. When these steps are followed in that order, the reader can track the problem, and its solution from his/her own perspective under the light of current literature. Otherwise, even a perfect study presented in a non-systematized, confused design will lose the chance of reading. Indeed inadequate information, inability to clarify the problem, and sometimes concealing the solution will keep the reader who has a desire to attain new information away from reading the manuscript. [ 1 – 3 ]

First of all, explanation of the topic in the light of the current literature should be made in clear, and precise terms as if the reader is completely ignorant of the subject. In this section, establishment of a warm rapport between the reader, and the manuscript is aimed. Since frantic plunging into the problem or the solution will push the reader into the dilemma of either screening the literature about the subject matter or refraining from reading the article. Updated, and robust information should be presented in the ‘Introduction’ section.

Then main topic of our manuscript, and the encountered problem should be analyzed in the light of the current literature following a short instance of brain exercise. At this point the problems should be reduced to one issue as far as possible. Of course, there might be more than one problem, however this new issue, and its solution should be the subject matter of another article. Problems should be expressed clearly. If targets are more numerous, and complex, solutions will be more than one, and confusing.

Finally, the last paragraphs of the ‘Introduction’ section should include the solution in which we will describe the information we generated, and related data. Our sentences which arouse curiosity in the readers should not be left unanswered. The reader who thinks to obtain the most effective information in no time while reading a scientific article should not be smothered with mysterious sentences, and word plays, and the readers should not be left alone to arrive at a conclusion by themselves. If we have contrary expectations, then we might write an article which won’t have any reader. A clearly expressed or recommended solutions to an explicitly revealed problem is also very important for the integrity of the ‘Introduction’ section. [ 1 – 5 ]

We can summarize our arguments with the following example ( Figure 1 ). The introduction section of the exemplary article is written in simple present tense which includes abbreviations, acronyms, and their explanations. Based on our statements above we can divide the introduction section into 3 parts. In the first paragraph, miniaturization, and evolvement of pediatric endourological instruments, and competitions among PNL, ESWL, and URS in the treatment of urinary system stone disease are described, in other words the background is prepared. In the second paragraph, a newly defined system which facilitates intrarenal access in PNL procedure has been described. Besides basic references related to the subject matter have been given, and their outcomes have been indicated. In other words, fundamental references concerning main subject have been discussed. In the last paragraph the aim of the researchers to investigate the outcomes, and safety of the application of this new method in the light of current information has been indicated.

An exemplary introduction section of an article

Apart from the abovementioned information about the introduction section of a scientific article we will summarize a few major issues in brief headings

Important points which one should take heed of:

- Abbreviations should be given following their explanations in the ‘Introduction’ section (their explanations in the summary does not count)

- Simple present tense should be used.

- References should be selected from updated publication with a higher impact factor, and prestigous source books.

- Avoid mysterious, and confounding expressions, construct clear sentences aiming at problematic issues, and their solutions.

- The sentences should be attractive, tempting, and comjprehensible.

- Firstly general, then subject-specific information should be given. Finally our aim should be clearly explained.

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Methodology – Types, Examples and writing Guide

Research Methodology – Types, Examples and writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Methodology

Definition:

Research Methodology refers to the systematic and scientific approach used to conduct research, investigate problems, and gather data and information for a specific purpose. It involves the techniques and procedures used to identify, collect , analyze , and interpret data to answer research questions or solve research problems . Moreover, They are philosophical and theoretical frameworks that guide the research process.

Structure of Research Methodology

Research methodology formats can vary depending on the specific requirements of the research project, but the following is a basic example of a structure for a research methodology section:

I. Introduction

- Provide an overview of the research problem and the need for a research methodology section

- Outline the main research questions and objectives

II. Research Design

- Explain the research design chosen and why it is appropriate for the research question(s) and objectives

- Discuss any alternative research designs considered and why they were not chosen

- Describe the research setting and participants (if applicable)

III. Data Collection Methods

- Describe the methods used to collect data (e.g., surveys, interviews, observations)

- Explain how the data collection methods were chosen and why they are appropriate for the research question(s) and objectives

- Detail any procedures or instruments used for data collection

IV. Data Analysis Methods

- Describe the methods used to analyze the data (e.g., statistical analysis, content analysis )

- Explain how the data analysis methods were chosen and why they are appropriate for the research question(s) and objectives

- Detail any procedures or software used for data analysis

V. Ethical Considerations

- Discuss any ethical issues that may arise from the research and how they were addressed

- Explain how informed consent was obtained (if applicable)

- Detail any measures taken to ensure confidentiality and anonymity

VI. Limitations

- Identify any potential limitations of the research methodology and how they may impact the results and conclusions

VII. Conclusion

- Summarize the key aspects of the research methodology section

- Explain how the research methodology addresses the research question(s) and objectives

Research Methodology Types

Types of Research Methodology are as follows:

Quantitative Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the collection and analysis of numerical data using statistical methods. This type of research is often used to study cause-and-effect relationships and to make predictions.

Qualitative Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the collection and analysis of non-numerical data such as words, images, and observations. This type of research is often used to explore complex phenomena, to gain an in-depth understanding of a particular topic, and to generate hypotheses.

Mixed-Methods Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that combines elements of both quantitative and qualitative research. This approach can be particularly useful for studies that aim to explore complex phenomena and to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a particular topic.

Case Study Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves in-depth examination of a single case or a small number of cases. Case studies are often used in psychology, sociology, and anthropology to gain a detailed understanding of a particular individual or group.

Action Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves a collaborative process between researchers and practitioners to identify and solve real-world problems. Action research is often used in education, healthcare, and social work.

Experimental Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the manipulation of one or more independent variables to observe their effects on a dependent variable. Experimental research is often used to study cause-and-effect relationships and to make predictions.

Survey Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the collection of data from a sample of individuals using questionnaires or interviews. Survey research is often used to study attitudes, opinions, and behaviors.

Grounded Theory Research Methodology

This is a research methodology that involves the development of theories based on the data collected during the research process. Grounded theory is often used in sociology and anthropology to generate theories about social phenomena.

Research Methodology Example

An Example of Research Methodology could be the following:

Research Methodology for Investigating the Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Reducing Symptoms of Depression in Adults

Introduction:

The aim of this research is to investigate the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in reducing symptoms of depression in adults. To achieve this objective, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) will be conducted using a mixed-methods approach.

Research Design:

The study will follow a pre-test and post-test design with two groups: an experimental group receiving CBT and a control group receiving no intervention. The study will also include a qualitative component, in which semi-structured interviews will be conducted with a subset of participants to explore their experiences of receiving CBT.

Participants:

Participants will be recruited from community mental health clinics in the local area. The sample will consist of 100 adults aged 18-65 years old who meet the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder. Participants will be randomly assigned to either the experimental group or the control group.

Intervention :

The experimental group will receive 12 weekly sessions of CBT, each lasting 60 minutes. The intervention will be delivered by licensed mental health professionals who have been trained in CBT. The control group will receive no intervention during the study period.

Data Collection:

Quantitative data will be collected through the use of standardized measures such as the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). Data will be collected at baseline, immediately after the intervention, and at a 3-month follow-up. Qualitative data will be collected through semi-structured interviews with a subset of participants from the experimental group. The interviews will be conducted at the end of the intervention period, and will explore participants’ experiences of receiving CBT.

Data Analysis:

Quantitative data will be analyzed using descriptive statistics, t-tests, and mixed-model analyses of variance (ANOVA) to assess the effectiveness of the intervention. Qualitative data will be analyzed using thematic analysis to identify common themes and patterns in participants’ experiences of receiving CBT.

Ethical Considerations: