An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Innov Aging

Family Relationships and Well-Being

Patricia a thomas.

1 Department of Sociology and Center on Aging and the Life Course, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana

2 Department of Sociology, Michigan State University, East Lansing

Debra Umberson

3 Department of Sociology and Population Research Center, University of Texas at Austin

Family relationships are enduring and consequential for well-being across the life course. We discuss several types of family relationships—marital, intergenerational, and sibling ties—that have an important influence on well-being. We highlight the quality of family relationships as well as diversity of family relationships in explaining their impact on well-being across the adult life course. We discuss directions for future research, such as better understanding the complexities of these relationships with greater attention to diverse family structures, unexpected benefits of relationship strain, and unique intersections of social statuses.

Translational Significance

It is important for future research and health promotion policies to take into account complexities in family relationships, paying attention to family context, diversity of family structures, relationship quality, and intersections of social statuses in an aging society to provide resources to families to reduce caregiving burdens and benefit health and well-being.

For better and for worse, family relationships play a central role in shaping an individual’s well-being across the life course ( Merz, Consedine, Schulze, & Schuengel, 2009 ). An aging population and concomitant age-related disease underlies an emergent need to better understand factors that contribute to health and well-being among the increasing numbers of older adults in the United States. Family relationships may become even more important to well-being as individuals age, needs for caregiving increase, and social ties in other domains such as the workplace become less central in their lives ( Milkie, Bierman, & Schieman, 2008 ). In this review, we consider key family relationships in adulthood—marital, parent–child, grandparent, and sibling relationships—and their impact on well-being across the adult life course.

We begin with an overview of theoretical explanations that point to the primary pathways and mechanisms through which family relationships influence well-being, and then we describe how each type of family relationship is associated with well-being, and how these patterns unfold over the adult life course. In this article, we use a broad definition of well-being, including multiple dimensions such as general happiness, life satisfaction, and good mental and physical health, to reflect the breadth of this concept’s use in the literature. We explore important directions for future research, emphasizing the need for research that takes into account the complexity of relationships, diverse family structures, and intersections of structural locations.

Pathways Linking Family Relationships to Well-Being

A life course perspective draws attention to the importance of linked lives, or interdependence within relationships, across the life course ( Elder, Johnson, & Crosnoe, 2003 ). Family members are linked in important ways through each stage of life, and these relationships are an important source of social connection and social influence for individuals throughout their lives ( Umberson, Crosnoe, & Reczek, 2010 ). Substantial evidence consistently shows that social relationships can profoundly influence well-being across the life course ( Umberson & Montez, 2010 ). Family connections can provide a greater sense of meaning and purpose as well as social and tangible resources that benefit well-being ( Hartwell & Benson, 2007 ; Kawachi & Berkman, 2001 ).

The quality of family relationships, including social support (e.g., providing love, advice, and care) and strain (e.g., arguments, being critical, making too many demands), can influence well-being through psychosocial, behavioral, and physiological pathways. Stressors and social support are core components of stress process theory ( Pearlin, 1999 ), which argues that stress can undermine mental health while social support may serve as a protective resource. Prior studies clearly show that stress undermines health and well-being ( Thoits, 2010 ), and strains in relationships with family members are an especially salient type of stress. Social support may provide a resource for coping that dulls the detrimental impact of stressors on well-being ( Thoits, 2010 ), and support may also promote well-being through increased self-esteem, which involves more positive views of oneself ( Fukukawa et al., 2000 ). Those receiving support from their family members may feel a greater sense of self-worth, and this enhanced self-esteem may be a psychological resource, encouraging optimism, positive affect, and better mental health ( Symister & Friend, 2003 ). Family members may also regulate each other’s behaviors (i.e., social control) and provide information and encouragement to behave in healthier ways and to more effectively utilize health care services ( Cohen, 2004 ; Reczek, Thomeer, Lodge, Umberson, & Underhill, 2014 ), but stress in relationships may also lead to health-compromising behaviors as coping mechanisms to deal with stress ( Ng & Jeffery, 2003 ). The stress of relationship strain can result in physiological processes that impair immune function, affect the cardiovascular system, and increase risk for depression ( Graham, Christian, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2006 ; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001 ), whereas positive relationships are associated with lower allostatic load (i.e., “wear and tear” on the body accumulating from stress) ( Seeman, Singer, Ryff, Love, & Levy-Storms, 2002 ). Clearly, the quality of family relationships can have considerable consequences for well-being.

Marital Relationships

A life course perspective has posited marital relationships as one of the most important relationships that define life context and in turn affect individuals’ well-being throughout adulthood ( Umberson & Montez, 2010 ). Being married, especially happily married, is associated with better mental and physical health ( Carr & Springer, 2010 ; Umberson, Williams, & Thomeer, 2013 ), and the strength of the marital effect on health is comparable to that of other traditional risk factors such as smoking and obesity ( Sbarra, 2009 ). Although some studies emphasize the possibility of selection effects, suggesting that individuals in better health are more likely to be married ( Lipowicz, 2014 ), most researchers emphasize two theoretical models to explain why marital relationships shape well-being: the marital resource model and the stress model ( Waite & Gallager, 2000 ; Williams & Umberson, 2004 ). The marital resource model suggests that marriage promotes well-being through increased access to economic, social, and health-promoting resources ( Rendall, Weden, Favreault, & Waldron, 2011 ; Umberson et al., 2013 ). The stress model suggests that negative aspects of marital relationships such as marital strain and marital dissolutions create stress and undermine well-being ( Williams & Umberson, 2004 ), whereas positive aspects of marital relationships may prompt social support, enhance self-esteem, and promote healthier behaviors in general and in coping with stress ( Reczek, Thomeer, et al., 2014 ; Symister & Friend, 2003 ; Waite & Gallager, 2000 ). Marital relationships also tend to become more salient with advancing age, as other social relationships such as those with family members, friends, and neighbors are often lost due to geographic relocation and death in the later part of the life course ( Liu & Waite, 2014 ).

Married people, on average, enjoy better mental health, physical health, and longer life expectancy than divorced/separated, widowed, and never-married people ( Hughes & Waite, 2009 ; Simon, 2002 ), although the health gap between the married and never married has decreased in the past few decades ( Liu & Umberson, 2008 ). Moreover, marital links to well-being depend on the quality of the relationship; those in distressed marriages are more likely to report depressive symptoms and poorer health than those in happy marriages ( Donoho, Crimmins, & Seeman, 2013 ; Liu & Waite, 2014 ; Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, 2006 ), whereas a happy marriage may buffer the effects of stress via greater access to emotional support ( Williams, 2003 ). A number of studies suggest that the negative aspects of close relationships have a stronger impact on well-being than the positive aspects of relationships (e.g., Rook, 2014 ), and past research shows that the impact of marital strain on health increases with advancing age ( Liu & Waite, 2014 ; Umberson et al., 2006 ).

Prior studies suggest that marital transitions, either into or out of marriage, shape life context and affect well-being ( Williams & Umberson, 2004 ). National longitudinal studies provide evidence that past experiences of divorce and widowhood are associated with increased risk of heart disease in later life especially among women, irrespective of current marital status ( Zhang & Hayward, 2006 ), and longer duration of divorce or widowhood is associated with a greater number of chronic conditions and mobility limitations ( Hughes & Waite, 2009 ; Lorenz, Wickrama, Conger, & Elder, 2006 ) but only short-term declines in mental health ( Lee & Demaris, 2007 ). On the other hand, entry into marriages, especially first marriages, improves psychological well-being and decreases depression ( Frech & Williams, 2007 ; Musick & Bumpass, 2012 ), although the benefits of remarriage may not be as large as those that accompany a first marriage ( Hughes & Waite, 2009 ). Taken together, these studies show the importance of understanding the lifelong cumulative impact of marital status and marital transitions.

Gender Differences

Gender is a central focus of research on marital relationships and well-being and an important determinant of life course experiences ( Bernard, 1972 ; Liu & Waite, 2014 ; Zhang & Hayward, 2006 ). A long-observed pattern is that men receive more physical health benefits from marriage than women, and women are more psychologically and physiologically vulnerable to marital stress than men ( Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001 ; Revenson et al., 2016 ; Simon, 2002 ; Williams, 2004 ). Women tend to receive more financial benefits from their typically higher-earning male spouse than do men, but men generally receive more health promotion benefits such as emotional support and regulation of health behaviors from marriage than do women ( Liu & Umberson, 2008 ; Liu & Waite, 2014 ). This is because within a traditional marriage, women tend to take more responsibility for maintaining social connections to family and friends, and are more likely to provide emotional support to their husband, whereas men are more likely to receive emotional support and enjoy the benefit of expanded social networks—all factors that may promote husbands’ health and well-being ( Revenson et al., 2016 ).

However, there is mixed evidence regarding whether men’s or women’s well-being is more affected by marriage. On the one hand, a number of studies have documented that marital status differences in both mental and physical health are greater for men than women ( Liu & Umberson, 2008 ; Sbarra, 2009 ). For example, Williams and Umberson (2004) found that men’s health improves more than women’s from entering marriage. On the other hand, a number of studies reveal stronger effects of marital strain on women’s health than men’s including more depressive symptoms, increases in cardiovascular health risk, and changes in hormones ( Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001 ; Liu & Waite, 2014 ; Liu, Waite, & Shen, 2016 ). Yet, other studies found no gender differences in marriage and health links (e.g., Umberson et al., 2006 ). The mixed evidence regarding gender differences in the impact of marital relationships on well-being may be attributed to different study samples (e.g., with different age groups) and variations in measurements and methodologies. More research based on representative longitudinal samples is clearly warranted to contribute to this line of investigation.

Race-Ethnicity and SES Heterogeneity

Family scholars argue that marriage has different meanings and dynamics across socioeconomic status (SES) and racial-ethnic groups due to varying social, economic, historical, and cultural contexts. Therefore, marriage may be associated with well-being in different ways across these groups. For example, women who are black or lower SES may be less likely than their white, higher SES counterparts to increase their financial capital from relationship unions because eligible men in their social networks are more socioeconomically challenged ( Edin & Kefalas, 2005 ). Some studies also find that marital quality is lower among low SES and black couples than white couples with higher SES ( Broman, 2005 ). This may occur because the former groups face more stress in their daily lives throughout the life course and these higher levels of stress undermine marital quality ( Umberson, Williams, Thomas, Liu, & Thomeer, 2014 ). Other studies, however, suggest stronger effects of marriage on the well-being of black adults than white adults. For example, black older adults seem to benefit more from marriage than older whites in terms of chronic conditions and disability ( Pienta, Hayward, & Jenkins, 2000 ).

Directions for Future Research

The rapid aging of the U.S. population along with significant changes in marriage and families indicate that a growing number of older adults enter late life with both complex marital histories and great heterogeneity in their relationships. While most research to date focuses on different-sex marriages, a growing body of research has started to examine whether the marital advantage in health and well-being is extended to same-sex couples, which represents a growing segment of relationship types among older couples ( Denney, Gorman, & Barrera, 2013 ; Goldsen et al., 2017 ; Liu, Reczek, & Brown, 2013 ; Reczek, Liu, & Spiker, 2014 ). Evidence shows that same-sex cohabiting couples report worse health than different-sex married couples ( Denney et al., 2013 ; Liu et al., 2013 ), but same-sex married couples are often not significantly different from or are even better off than different-sex married couples in other outcomes such as alcohol use ( Reczek, Liu, et al., 2014 ) and care from their partner during periods of illness ( Umberson, Thomeer, Reczek, & Donnelly, 2016 ). These results suggest that marriage may promote the well-being of same-sex couples, perhaps even more so than for different-sex couples ( Umberson et al., 2016 ). Including same-sex couples in future work on marriage and well-being will garner unique insights into gender differences in marital dynamics that have long been taken for granted based on studies of different-sex couples ( Umberson, Thomeer, Kroeger, Lodge, & Xu, 2015 ). Moreover, future work on same-sex and different-sex couples should take into account the intersection of other statuses such as race-ethnicity and SES to better understand the impact of marital relationships on well-being.

Another avenue for future research involves investigating complexities of marital strain effects on well-being. Some recent studies among older adults suggest that relationship strain may actually benefit certain dimensions of well-being. These studies suggest that strain with a spouse may be protective for certain health outcomes including cognitive decline ( Xu, Thomas, & Umberson, 2016 ) and diabetes control ( Liu et al., 2016 ), while support may not be, especially for men ( Carr, Cornman, & Freedman, 2016 ). Explanations for these unexpected findings among older adults are not fully understood. Family and health scholars suggest that spouses may prod their significant others to engage in more health-promoting behaviors ( Umberson, Crosnoe, et al., 2010 ). These attempts may be a source of friction, creating strain in the relationship; however, this dynamic may still contribute to better health outcomes for older adults. Future research should explore the processes by which strain may have a positive influence on health and well-being, perhaps differently by gender.

Intergenerational Relationships

Children and parents tend to remain closely connected to each other across the life course, and it is well-established that the quality of intergenerational relationships is central to the well-being of both generations ( Merz, Schuengel, & Schulze, 2009 ; Polenick, DePasquale, Eggebeen, Zarit, & Fingerman, 2016 ). Recent research also points to the importance of relationships with grandchildren for aging adults ( Mahne & Huxhold, 2015 ). We focus here on the well-being of parents, adult children, and grandparents. Parents, grandparents, and children often provide care for each other at different points in the life course, which can contribute to social support, stress, and social control mechanisms that influence the health and well-being of each in important ways over the life course ( Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2003 ; Pinquart & Soerensen, 2007 ; Reczek, Thomeer, et al., 2014 ).

Family scholarship highlights the complexities of parent–child relationships, finding that parenthood generates both rewards and stressors, with important implications for well-being ( Nomaguchi & Milkie, 2003 ; Umberson, Pudrovska, & Reczek, 2010 ). Parenthood increases time constraints, producing stress and diminishing well-being, especially when children are younger ( Nomaguchi, Milkie, & Bianchi, 2005 ), but parenthood can also increase social integration, leading to greater emotional support and a sense of belonging and meaning ( Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000 ), with positive consequences for well-being. Studies show that adult children play a pivotal role in the social networks of their parents across the life course ( Umberson, Pudrovska, et al., 2010 ), and the effects of parenthood on health and well-being become increasingly important at older ages as adult children provide one of the major sources of care for aging adults ( Seltzer & Bianchi, 2013 ). Norms of filial obligation of adult children to care for parents may be a form of social capital to be accessed by parents when their needs arise ( Silverstein, Gans, & Yang, 2006 ).

Although the general pattern is that receiving support from adult children is beneficial for parents’ well-being ( Merz, Schulze, & Schuengel, 2010 ), there is also evidence showing that receiving social support from adult children is related to lower well-being among older adults, suggesting that challenges to an identity of independence and usefulness may offset some of the benefits of receiving support ( Merz et al., 2010 ; Thomas, 2010 ). Contrary to popular thought, older parents are also very likely to provide instrumental/financial support to their adult children, typically contributing more than they receive ( Grundy, 2005 ), and providing emotional support to their adult children is related to higher well-being for older adults ( Thomas, 2010 ). In addition, consistent with the tenets of stress process theory, most evidence points to poor quality relationships with adult children as detrimental to parents’ well-being ( Koropeckyj-Cox, 2002 ; Polenick et al., 2016 ); however, a recent study found that strain with adult children is related to better cognitive health among older parents, especially fathers ( Thomas & Umberson, 2017 ).

Adult Children

As children and parents age, the nature of the parent–child relationship often changes such that adult children may take on a caregiving role for their older parents ( Pinquart & Soerensen, 2007 ). Adult children often experience competing pressures of employment, taking care of their own children, and providing care for older parents ( Evans et al., 2016 ). Support and strain from intergenerational ties during this stressful time of balancing family roles and work obligations may be particularly important for the mental health of adults in midlife ( Thomas, 2016 ). Most evidence suggests that caregiving for parents is related to lower well-being for adult children, including more negative affect and greater stress response in terms of overall output of daily cortisol ( Bangerter et al., 2017 ); however, some studies suggest that caregiving may be beneficial or neutral for well-being ( Merz et al., 2010 ). Family scholars suggest that this discrepancy may be due to varying types of caregiving and relationship quality. For example, providing emotional support to parents can increase well-being, but providing instrumental support does not unless the caregiver is emotionally engaged ( Morelli, Lee, Arnn, & Zaki, 2015 ). Moreover, the quality of the adult child-parent relationship may matter more for the well-being of adult children than does the caregiving they provide ( Merz, Schuengel, et al., 2009 ).

Although caregiving is a critical issue, adult children generally experience many years with parents in good health ( Settersten, 2007 ), and relationship quality and support exchanges have important implications for well-being beyond caregiving roles. The preponderance of research suggests that most adults feel emotionally close to their parents, and emotional support such as encouragement, companionship, and serving as a confidant is commonly exchanged in both directions ( Swartz, 2009 ). Intergenerational support exchanges often flow across generations or towards adult children rather than towards parents. For example, adult children are more likely to receive financial support from parents than vice versa until parents are very old ( Grundy, 2005 ). Intergenerational support exchanges are integral to the lives of both parents and adult children, both in times of need and in daily life.

Grandparents

Over 65 million Americans are grandparents ( Ellis & Simmons, 2014 ), 10% of children lived with at least one grandparent in 2012 ( Dunifon, Ziol-Guest, & Kopko, 2014 ), and a growing number of American families rely on grandparents as a source of support ( Settersten, 2007 ), suggesting the importance of studying grandparenting. Grandparents’ relationships with their grandchildren are generally related to higher well-being for both grandparents and grandchildren, with some important exceptions such as when they involve more extensive childcare responsibilities ( Kim, Kang, & Johnson-Motoyama, 2017 ; Lee, Clarkson-Hendrix, & Lee, 2016 ). Most grandparents engage in activities with their grandchildren that they find meaningful, feel close to their grandchildren, consider the grandparent role important ( Swartz, 2009 ), and experience lower well-being if they lose contact with their grandchildren ( Drew & Silverstein, 2007 ). However, a growing proportion of children live in households maintained by grandparents ( Settersten, 2007 ), and grandparents who care for their grandchildren without the support of the children’s parents usually experience greater stress ( Lee et al., 2016 ) and more depressive symptoms ( Blustein, Chan, & Guanais, 2004 ), sometimes juggling grandparenting responsibilities with their own employment ( Harrington Meyer, 2014 ). Using professional help and community services reduced the detrimental effects of grandparent caregiving on well-being ( Gerard, Landry-Meyer, & Roe, 2006 ), suggesting that future policy could help mitigate the stress of grandparent parenting and enhance the rewarding aspects of grandparenting instead.

Substantial evidence suggests that the experience of intergenerational relationships varies for men and women. Women tend to be more involved with and affected by intergenerational relationships, with adult children feeling closer to mothers than fathers ( Swartz, 2009 ). Moreover, relationship quality with children is more strongly associated with mothers’ well-being than with fathers’ well-being ( Milkie et al., 2008 ). Motherhood may be particularly salient to women ( McQuillan, Greil, Shreffler, & Tichenor, 2008 ), and women carry a disproportionate share of the burden of parenting, including greater caregiving for young children and aging parents as well as time deficits from these obligations that lead to lower well-being ( Nomaguchi et al., 2005 ; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2006 ). Mothers often report greater parental pressures than fathers, such as more obligation to be there for their children ( Reczek, Thomeer, et al., 2014 ; Stone, 2007 ), and to actively work on family relationships ( Erickson, 2005 ). Mothers are also more likely to blame themselves for poor parent–child relationship quality ( Elliott, Powell, & Brenton, 2015 ), contributing to greater distress for women. It is important to take into account the different pressures and meanings surrounding intergenerational relationships for men and for women in future research.

Family scholars have noted important variations in family dynamics and constraints by race-ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Lower SES can produce and exacerbate family strains ( Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010 ). Socioeconomically disadvantaged adult children may need more assistance from parents and grandparents who in turn have fewer resources to provide ( Seltzer & Bianchi, 2013 ). Higher SES and white families tend to provide more financial and emotional support, whereas lower SES, black, and Latino families are more likely to coreside and provide practical help, and these differences in support exchanges contribute to the intergenerational transmission of inequality through families ( Swartz, 2009 ). Moreover, scholars have found that a happiness penalty exists such that parents of young children have lower levels of well-being than nonparents; however, policies such as childcare subsidies and paid time off that help parents negotiate work and family responsibilities explain this disparity ( Glass, Simon, & Andersson, 2016 ). Fewer resources can also place strain on grandparent–grandchild relationships. For example, well-being derived from these relationships may be unequally distributed across grandparents’ education level such that those with less education bear the brunt of more stressful grandparenting experiences and lower well-being ( Mahne & Huxhold, 2015 ). Both the burden of parenting grandchildren and its effects on depressive symptoms disproportionately fall upon single grandmothers of color ( Blustein et al., 2004 ). These studies demonstrate the importance of understanding structural constraints that produce greater stress for less advantaged groups and their impact on family relationships and well-being.

Research on intergenerational relationships suggests the importance of understanding greater complexity in these relationships in future work. For example, future research should pay greater attention to diverse family structures and perspectives of multiple family members. There is an increasing trend of individuals delaying childbearing or choosing not to bear children ( Umberson, Pudrovska, et al., 2010 ). How might this influence marital quality and general well-being over the life course and across different social groups? Greater attention to the quality and context of intergenerational relationships from each family member’s perspective over time may prove fruitful by gaining both parents’ and each child’s perceptions. This work has already yielded important insights, such as the ways in which intergenerational ambivalence (simultaneous positive and negative feelings about intergenerational relationships) from the perspectives of parents and adult children may be detrimental to well-being for both parties ( Fingerman, Pitzer, Lefkowitz, Birditt, & Mroczek, 2008 ; Gilligan, Suitor, Feld, & Pillemer, 2015 ). Future work understanding the perspectives of each family member could also provide leverage in understanding the mixed findings regarding whether living in blended families with stepchildren influences well-being ( Gennetian, 2005 ; Harcourt, Adler-Baeder, Erath, & Pettit, 2013 ) and the long-term implications of these family structures when older adults need care ( Seltzer & Bianchi, 2013 ). Longitudinal data linking generations, paying greater attention to the context of these relationships, and collected from multiple family members can help untangle the ways in which family members influence each other across the life course and how multiple family members’ well-being may be intertwined in important ways.

Future studies should also consider the impact of intersecting structural locations that place unique constraints on family relationships, producing greater stress at some intersections while providing greater resources at other intersections. For example, same-sex couples are less likely to have children ( Carpenter & Gates, 2008 ) and are more likely to provide parental caregiving regardless of gender ( Reczek & Umberson, 2016 ), suggesting important implications for stress and burden in intergenerational caregiving for this group. Much of the work on gender, sexuality, race, and socioeconomic status differences in intergenerational relationships and well-being examine one or two of these statuses, but there may be unique effects at the intersection of these and other statuses such as disability, age, and nativity. Moreover, these effects may vary at different stages of the life course.

Sibling Relationships

Sibling relationships are understudied, and the research on adult siblings is more limited than for other family relationships. Yet, sibling relationships are often the longest lasting family relationship in an individual’s life due to concurrent life spans, and indeed, around 75% of 70-year olds have a living sibling ( Settersten, 2007 ). Some suggest that sibling relationships play a more meaningful role in well-being than is often recognized ( Cicirelli, 2004 ). The available evidence suggests that high quality relationships characterized by closeness with siblings are related to higher levels of well-being ( Bedford & Avioli, 2001 ), whereas sibling relationships characterized by conflict and lack of closeness have been linked to lower well-being in terms of major depression and greater drug use in adulthood ( Waldinger, Vaillant, & Orav, 2007 ). Parental favoritism and disfavoritism of children affects the closeness of siblings ( Gilligan, Suitor, & Nam, 2015 ) and depression ( Jensen, Whiteman, Fingerman, & Birditt, 2013 ). Similar to other family relationships, sibling relationships can be characterized by both positive and negative aspects that may affect elements of the stress process, providing both resources and stressors that influence well-being.

Siblings play important roles in support exchanges and caregiving, especially if their sibling experiences physical impairment and other close ties, such as a spouse or adult children, are not available ( Degeneffe & Burcham, 2008 ; Namkung, Greenberg, & Mailick, 2017 ). Although sibling caregivers report lower well-being than noncaregivers, sibling caregivers experience this lower well-being to a lesser extent than spousal caregivers ( Namkung et al., 2017 ). Most people believe that their siblings would be available to help them in a crisis ( Connidis, 1994 ; Van Volkom, 2006 ), and in general support exchanges, receiving emotional support from a sibling is related to higher levels of well-being among older adults ( Thomas, 2010 ). Relationship quality affects the experience of caregiving, with higher quality sibling relationships linked to greater provision of care ( Eriksen & Gerstel, 2002 ) and a lower likelihood of emotional strain from caregiving ( Mui & Morrow-Howell, 1993 ; Quinn, Clare, & Woods, 2009 ). Taken together, these studies suggest the importance of sibling relationships for well-being across the adult life course.

The gender of the sibling dyad may play a role in the relationship’s effect on well-being, with relationships with sisters perceived as higher quality and linked to higher well-being ( Van Volkom, 2006 ), though some argue that brothers do not show their affection in the same way but nevertheless have similar sentiments towards their siblings ( Bedford & Avioli, 2001 ). General social support exchanges with siblings may be influenced by gender and larger family context; sisters exchanged more support with their siblings when they had higher quality relationships with their parents, but brothers exhibited a more compensatory role, exchanging more emotional support with siblings when they had lower quality relationships with their parents ( Voorpostel & Blieszner, 2008 ). Caregiving for aging parents is also distributed differently by gender, falling disproportionately on female siblings ( Pinquart & Sorensen, 2006 ), and sons provide less care to their parents if they have a sister ( Grigoryeva, 2017 ). However, men in same-sex marriages were more likely than men in different-sex marriages to provide caregiving to parents and parents-in-law ( Reczek & Umberson, 2016 ), which may ease the stress and burden on their female siblings.

Although there is less research in this area, family scholars have noted variations in sibling relationships and their effects by race-ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Lower socioeconomic status has been associated with reports of feeling less attached to siblings and this influences several outcomes such as obesity, depression, and substance use ( Van Gundy et al., 2015 ). Fewer socioeconomic resources can also limit the amount of care siblings provide ( Eriksen & Gerstel, 2002 ). These studies suggest sibling relationship quality as an axis of further disadvantage for already disadvantaged individuals. Sibling relationships may influence caregiving experiences by race as well, with black caregivers more likely to have siblings who also provide care to their parents than white caregivers ( White-Means & Rubin, 2008 ) and sibling caregiving leading to lower well-being among white caregivers than minority caregivers ( Namkung et al., 2017 ).

Research on within-family differences has made great strides in our understanding of family relationships and remains a fruitful area of growth for future research (e.g., Suitor et al., 2017 ). Data gathered on multiple members within the same family can help researchers better investigate how families influence well-being in complex ways, including reciprocal influences between siblings. Siblings may have different perceptions of their relationships with each other, and this may vary by gender and other social statuses. This type of data might be especially useful in understanding family effects in diverse family structures, such as differences in treatment and outcomes of biological versus stepchildren, how characteristics of their relationships such as age differences may play a role, and the implications for caregiving for aging parents and for each other. Moreover, it is important to use longitudinal data to understand the consequences of these within-family differences over time as the life course unfolds. In addition, a greater focus on heterogeneity in sibling relationships and their consequences at the intersection of gender, race-ethnicity, SES, and other social statuses merit further investigation.

Relationships with family members are significant for well-being across the life course ( Merz, Consedine, et al., 2009 ; Umberson, Pudrovska, et al., 2010 ). As individuals age, family relationships often become more complex, with sometimes complicated marital histories, varying relationships with children, competing time pressures, and obligations for care. At the same time, family relationships become more important for well-being as individuals age and social networks diminish even as family caregiving needs increase. Stress process theory suggests that the positive and negative aspects of relationships can have a large impact on the well-being of individuals. Family relationships provide resources that can help an individual cope with stress, engage in healthier behaviors, and enhance self-esteem, leading to higher well-being. However, poor relationship quality, intense caregiving for family members, and marital dissolution are all stressors that can take a toll on an individual’s well-being. Moreover, family relationships also change over the life course, with the potential to share different levels of emotional support and closeness, to take care of us when needed, to add varying levels of stress to our lives, and to need caregiving at different points in the life course. The potential risks and rewards of these relationships have a cumulative impact on health and well-being over the life course. Additionally, structural constraints and disadvantage place greater pressures on some families than others based on structural location such as gender, race, and SES, producing further disadvantage and intergenerational transmission of inequality.

Future research should take into account greater complexity in family relationships, diverse family structures, and intersections of social statuses. The rapid aging of the U.S. population along with significant changes in marriage and families suggest more complex marital and family histories as adults enter late life, which will have a large impact on family dynamics and caregiving. Growing segments of family relationships among older adults include same-sex couples, those without children, and those experiencing marital transitions leading to diverse family structures, which all merit greater attention in future research. Moreover, there is some evidence that strain in relationships can be beneficial for certain health outcomes, and the processes by which this occurs merit further investigation. A greater use of longitudinal data that link generations and obtain information from multiple family members will help researchers better understand the ways in which these complex family relationships unfold across the life course and shape well-being. We also highlighted gender, race-ethnicity, and socioeconomic status differences in each of these family relationships and their impact on well-being; however, many studies only consider one status at a time. Future research should consider the impact of intersecting structural locations that place unique constraints on family relationships, producing greater stress or providing greater resources at the intersections of different statuses.

The changing landscape of families combined with population aging present unique challenges and pressures for families and health care systems. With more experiences of age-related disease in a growing population of older adults as well as more complex family histories as these adults enter late life, such as a growing proportion of diverse family structures without children or with stepchildren, caregiving obligations and availability may be less clear. It is important to address ways to ease caregiving or shift the burden away from families through a variety of policies, such as greater resources for in-home aid, creation of older adult residential communities that facilitate social interactions and social support structures, and patient advocates to help older adults navigate health care systems. Adults in midlife may experience competing family pressures from their young children and aging parents, and policies such as childcare subsidies and paid leave to care for family members could reduce burden during this often stressful time ( Glass et al., 2016 ). Professional help and community services can also reduce the burden for grandparents involved in childcare, enabling grandparents to focus on the more positive aspects of grandparent–grandchild relationships. It is important for future research and health promotion policies to take into account the contexts and complexities of family relationships as part of a multipronged approach to benefit health and well-being, especially as a growing proportion of older adults reach late life.

This work was supported in part by grant, 5 R24 HD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

- Bangerter L. R., Liu Y., Kim K., Zarit S. H., Birditt K. S., & Fingerman K. L (2017). Everyday support to aging parents: Links to middle-aged children’s diurnal cortisol and daily mood . The Gerontologist , gnw207. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw207 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bedford V. H., & Avioli P. S (2001). Variations on sibling intimacy in old age . Generations , 25 , 34–40. [ Google Scholar ]

- Berkman L. F., Glass T., Brissette I., & Seeman T. E (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium . Social Science & Medicine , 51 , 843–857. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernard J. (1972). The future of marriage . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blustein J., Chan S., & Guanais F. C (2004). Elevated depressive symptoms among caregiving grandparents . Health Services Research , 39 , 1671–1689. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00312.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Broman C. L. (2005). Marital quality in black and white marriages . Journal of Family Issues , 26 , 431–441. doi:10.1177/0192513X04272439 [ Google Scholar ]

- Carpenter C., & Gates G. J (2008). Gay and lesbian partnership: Evidence from California . Demography , 45 , 573–590. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0014 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carr D., Cornman J. C., & Freedman V. A (2016). Marital quality and negative experienced well-being: An assessment of actor and partner effects among older married persons . Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 71 , 177–187. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv073 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carr D., & Springer K. W (2010). Advances in families and health research in the 21st century . Journal of Marriage and Family , 72 , 743–761. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00728.x [ Google Scholar ]

- Cicirelli V. G. (2004). Midlife sibling relationships in the context of the family . The Gerontologist , 44 , 541. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen S. (2004). Social relationships and health . American Psychologist , 59 , 676–684. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Conger R. D., Conger K. J., & Martin M. J (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development . Journal of Marriage and the Family , 72 , 685–704. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00725.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Connidis I. A. (1994). Sibling support in older age . Journal of Gerontology , 49 , S309–S318. doi:10.1093/geronj/49.6.S309 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Degeneffe C. E., & Burcham C. M (2008). Adult sibling caregiving for persons with traumatic brain injury: Predictors of affective and instrumental support . Journal of Rehabilitation , 74 , 10–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Denney J. T., Gorman B. K., & Barrera C. B (2013). Families, resources, and adult health: Where do sexual minorities fit ? Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 54 , 46. doi:10.1177/0022146512469629 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Donoho C. J., Crimmins E. M., & Seeman T. E (2013). Marital quality, gender, and markers of inflammation in the MIDUS cohort . Journal of Marriage and Family , 75 , 127–141. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01023.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Drew L. M., & Silverstein M (2007). Grandparents’ psychological well-being after loss of contact with their grandchildren . Journal of Family Psychology , 21 , 372–379. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.372 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dunifon R. E., Ziol-Guest K. M., & Kopko K (2014). Grandparent coresidence and family well-being . The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 654 , 110–126. doi:10.1177/0002716214526530 [ Google Scholar ]

- Edin K., & Kefalas M (2005). Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Elder G. H., Johnson M. K., & Crosnoe R (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory . In Mortimer J. T. & Shanahan M. J. (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–19). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-0-306-48247-2_1 [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliott S., Powell R., & Brenton J (2015). Being a good mom: Low-income, black single mothers negotiate intensive mothering . Journal of Family Issues , 36 , 351–370. doi:10.1177/0192513X13490279 [ Google Scholar ]

- Ellis R. R., & Simmons T (2014). Coresident grandparents and their grandchildren: 2012 . Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. [ Google Scholar ]

- Erickson R. J. (2005). Why emotion work matters: Sex, gender, and the division of household labor . Journal of Marriage and Family , 67 , 337–351. doi:10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00120.x [ Google Scholar ]

- Eriksen S., & Gerstel N (2002). A labor of love or labor itself . Journal of Family Issues , 23 , 836–856. doi:10.1177/019251302236597 [ Google Scholar ]

- Evans K. L., Millsteed J., Richmond J. E., Falkmer M., Falkmer T., & Girdler S. J (2016). Working sandwich generation women utilize strategies within and between roles to achieve role balance . PLOS ONE , 11 , e0157469. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157469 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fingerman K. L., Pitzer L., Lefkowitz E. S., Birditt K. S., & Mroczek D (2008). Ambivalent relationship qualities between adults and their parents: Implications for the well-being of both parties . The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 63 , P362–P371. doi:10.1093/geronb/63.6.P362 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frech A., & Williams K (2007). Depression and the psychological benefits of entering marriage . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 48 , 149. doi:10.1177/002214650704800204 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fukukawa Y., Tsuboi S., Niino N., Ando F., Kosugi S., & Shimokata H (2000). Effects of social support and self-esteem on depressive symptoms in Japanese middle-aged and elderly people . Journal of Epidemiology , 10 , 63–69. doi:10.2188/jea.10.1sup_63 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gennetian L. A. (2005). One or two parents? Half or step siblings? The effect of family structure on young children’s achievement . Journal of Population Economics , 18 , 415–436. doi:10.1007/s00148-004-0215-0 [ Google Scholar ]

- Gerard J. M., Landry-Meyer L., & Roe J. G (2006). Grandparents raising grandchildren: The role of social support in coping with caregiving challenges . The International Journal of Aging and Human Development , 62 , 359–383. doi:10.2190/3796-DMB2-546Q-Y4AQ [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilligan M., Suitor J. J., Feld S., & Pillemer K (2015). Do positive feelings hurt? Disaggregating positive and negative components of intergenerational ambivalence . Journal of Marriage and Family , 77 , 261–276. doi:10.1111/jomf.12146 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilligan M., Suitor J. J., & Nam S (2015). Maternal differential treatment in later life families and within-family variations in adult sibling closeness . The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 70 , 167–177. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbu148 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Glass J., Simon R. W., & Andersson M. A (2016). Parenthood and happiness: Effects of work-family reconciliation policies in 22 OECD countries . AJS; American Journal of Sociology , 122 , 886–929. doi:10.1086/688892 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldsen J., Bryan A., Kim H.-J., Muraco A., Jen S., & Fredriksen-Goldsen K (2017). Who says I do: The changing context of marriage and health and quality of life for LGBT older adults . The Gerontologist , 57 , S50. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw174 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Graham J. E., Christian L. M., & Kiecolt-Glaser J. K (2006). Marriage, health, and immune function: A review of key findings and the role of depression . In Beach S. & Wamboldt M. (Eds.), Relational processes in mental health, Vol. 11 . Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Grigoryeva A. (2017). Own gender, sibling’s gender, parent’s gender: The division of elderly parent care among adult children . American Sociological Review , 82 , 116–146. doi:10.1177/0003122416686521 [ Google Scholar ]

- Grundy E. (2005). Reciprocity in relationships: Socio-economic and health influences on intergenerational exchanges between third age parents and their adult children in Great Britain . The British Journal of Sociology , 56 , 233–255. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2005.00057.x [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Harcourt K. T., Adler-Baeder F., Erath S., & Pettit G. S (2013). Examining family structure and half-sibling influence on adolescent well-being . Journal of Family Issues , 36 , 250–272. doi:10.1177/0192513X13497350 [ Google Scholar ]

- Harrington Meyer M. (2014). Grandmothers at work - juggling families and jobs . New York, NY: NYU Press. doi:10.18574/nyu/9780814729236.001.0001 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hartwell S. W., & Benson P. R (2007). Social integration: A conceptual overview and two case studies . In Avison W. R., McLeod J. D., & Pescosolido B. (Eds.), Mental health, social mirror (pp. 329–353). New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-36320-2_14 [ Google Scholar ]

- Hughes M. E., & Waite L. J (2009). Marital biography and health at mid-life . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 50 , 344. doi:10.1177/002214650905000307 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jensen A. C., Whiteman S. D., Fingerman K. L., & Birditt K. S (2013). “Life still isn’t fair”: Parental differential treatment of young adult siblings . Journal of Marriage and the Family , 75 , 438–452. doi:10.1111/jomf.12002 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kawachi I., & Berkman L. F (2001). Social ties and mental health . Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine , 78 , 458–467. doi:10.1093/jurban/78.3.458 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiecolt-Glaser J. K., & Newton T. L (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers . Psychological Bulletin , 127 , 472–503. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.127.4.472 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim H.-J., Kang H., & Johnson-Motoyama M (2017). The psychological well-being of grandparents who provide supplementary grandchild care: A systematic review . Journal of Family Studies , 23 , 118–141. doi:10.1080/13229400.2016.1194306 [ Google Scholar ]

- Koropeckyj-Cox T. (2002). Beyond parental status: Psychological well-being in middle and old age . Journal of Marriage and Family , 64 , 957–971. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00957.x [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee E., Clarkson-Hendrix M., & Lee Y (2016). Parenting stress of grandparents and other kin as informal kinship caregivers: A mixed methods study . Children and Youth Services Review , 69 , 29–38. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.07.013 [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee G. R., & Demaris A (2007). Widowhood, gender, and depression: A longitudinal analysis . Research on Aging , 29 , 56–72. doi:10.1177/0164027506294098 [ Google Scholar ]

- Lipowicz A. (2014). Some evidence for health-related marriage selection . American Journal of Human Biology , 26 , 747–752. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22588 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu H., Reczek C., & Brown D (2013). Same-sex cohabitors and health: The role of race-ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 54 , 25. doi:10.1177/0022146512468280 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu H., & Umberson D. J (2008). The times they are a changin’: Marital status and health differentials from 1972 to 2003 . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 49 , 239–253. doi:10.1177/002214650804900301 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu H., & Waite L (2014). Bad marriage, broken heart? Age and gender differences in the link between marital quality and cardiovascular risks among older adults . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 55 , 403–423 doi:10.1177/0022146514556893 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu H., Waite L., & Shen S (2016). Diabetes risk and disease management in later life: A national longitudinal study of the role of marital quality . Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 71 , 1070–1080. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbw061 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lorenz F. O., Wickrama K. A. S., Conger R. D., & Elder G. H (2006). The short-term and decade-long effects of divorce on women’s midlife health . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 47 , 111–125. doi:10.1177/002214650604700202 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mahne K., & Huxhold O (2015). Grandparenthood and subjective well-being: Moderating effects of educational level . The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 70 , 782–792. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbu147 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McQuillan J., Greil A. L., Shreffler K. M., & Tichenor V (2008). The importance of motherhood among women in the contemporary United States . Gender & Society , 22 , 477–496. doi:10.1177/0891243208319359 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Merz E.-M., Consedine N. S., Schulze H.-J., & Schuengel C (2009). Well-being of adult children and ageing parents: Associations with intergenerational support and relationship quality . Ageing & Society , 29 , 783–802. doi:10.1017/s0144686x09008514 [ Google Scholar ]

- Merz E.-M., Schuengel C., & Schulze H.-J (2009). Intergenerational relations across 4 years: Well-being is affected by quality, not by support exchange . Gerontologist , 49 , 536–548. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp043 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Merz E.-M., Schulze H.-J., & Schuengel C (2010). Consequences of filial support for two generations: A narrative and quantitative review . Journal of Family Issues , 31 , 1530–1554. doi:10.1177/0192513x10365116 [ Google Scholar ]

- Milkie M. A., Bierman A., & Schieman S (2008). How adult children influence older parents’ mental health: Integrating stress-process and life-course perspectives . Social Psychology Quarterly , 71 , 86. doi:10.1177/019027250807100109 [ Google Scholar ]

- Morelli S. A., Lee I. A., Arnn M. E., & Zaki J (2015). Emotional and instrumental support provision interact to predict well-being . Emotion , 15 , 484–493. doi:10.1037/emo0000084 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mui A. C., & Morrow-Howell N (1993). Sources of emotional strain among the oldest caregivers . Research on Aging , 15 , 50–69. doi:10.1177/0164027593151003 [ Google Scholar ]

- Musick K., & Bumpass L (2012). Reexamining the case for marriage: Union formation and changes in well-being . Journal of Marriage and Family , 74 , 1–18. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00873.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Namkung E. H., Greenberg J. S., & Mailick M. R (2017). Well-being of sibling caregivers: Effects of kinship relationship and race . The Gerontologist , 57 , 626–636. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw008 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ng D. M., & Jeffery R. W (2003). Relationships between perceived stress and health behaviors in a sample of working adults . Health Psychology , 22 , 638–642. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.22.6.638 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nomaguchi K. M., & Milkie M. A (2003). Costs and rewards of children: The effects of becoming a parent on adults’ lives . Journal of Marriage and Family , 65 , 356–374. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00356.x 0022-2445 [ Google Scholar ]

- Nomaguchi K. M., Milkie M. A., & Bianchi S. B (2005). Time strains and psychological well-being: Do dual-earner mothers and fathers differ ? Journal of Family Issues , 26 , 756–792. doi:10.1177/0192513X05277524 [ Google Scholar ]

- Pearlin L. I. (1999). Stress and mental health: A conceptual overview . In Horwitz A. V. & Scheid T. (Eds.), A Handbook for the study of mental health: Social contexts, theories, and systems (pp. 161–175). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pienta A. M., Hayward M. D., & Jenkins K. R (2000). Health consequences of marriage for the retirement years . Journal of Family Issues , 21 , 559–586. doi:10.1177/019251300021005003 [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinquart M., & Soerensen S (2007). Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: A meta-analysis . Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 62 , P126–P137. doi:10.1093/geronb/62.2.P126 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pinquart M., & Sorensen S (2006). Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: An updated meta-analysis . Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 61 , P33–P45. doi:10.1093/geronb/61.1.P33 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Polenick C. A., DePasquale N., Eggebeen D. J., Zarit S. H., & Fingerman K. L (2016). Relationship quality between older fathers and middle-aged children: Associations with both parties’ subjective well-being . The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , gbw094. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbw094 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Quinn C., Clare L., & Woods B (2009). The impact of the quality of relationship on the experiences and wellbeing of caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review . Aging & Mental Health , 13 , 143–154. doi:10.1080/13607860802459799 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reczek C., Liu H., & Spiker R (2014). A population-based study of alcohol use in same-sex and different-sex unions . Journal of Marriage and Family , 76 , 557–572. doi:10.1111/jomf.12113 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reczek C., Thomeer M. B., Lodge A. C., Umberson D., & Underhill M (2014). Diet and exercise in parenthood: A social control perspective . Journal of Marriage and Family , 76 , 1047–1062. doi:10.1111/jomf.12135 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reczek C., & Umberson D (2016). Greedy spouse, needy parent: The marital dynamics of gay, lesbian, and heterosexual intergenerational caregivers . Journal of Marriage and Family , 78 , 957–974. doi:10.1111/jomf.12318 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rendall M. S., Weden M. M., Favreault M. M., & Waldron H (2011). The protective effect of marriage for survival: A review and update . Demography , 48 , 481. doi:10.1007/s13524-011-0032-5 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Revenson T. A., Griva K., Luszczynska A., Morrison V., Panagopoulou E., Vilchinsky N., & Hagedoorn M (2016). Gender and caregiving: The costs of caregiving for women . In Caregiving in the Illness Context (pp. 48–63). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/9781137558985.0008 [ Google Scholar ]

- Rook K. S. (2014). The health effects of negative social exchanges in later life . Generations , 38 , 15–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sbarra D. A. (2009). Marriage protects men from clinically meaningful elevations in C-reactive protein: Results from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) . Psychosomatic Medicine , 71 , 828. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b4c4f2 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seeman T. E., Singer B. H., Ryff C. D., Love G. D., & Levy-Storms L (2002). Social relationships, gender, and allostatic load across two age cohorts . Psychosomatic Medicine , 64 , 395–406. doi:10.1097/00006842-200205000-00004 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Seltzer J. A., & Bianchi S. M (2013). Demographic change and parent-child relationships in adulthood . Annual Review of Sociology , 39 , 275–290. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145602 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Settersten R. A. (2007). Social relationships in the new demographic regime: Potentials and risks, reconsidered . Advances in Life Course Research , 12 , 3–28. doi:10.1016/S1040-2608(07)12001–3 [ Google Scholar ]

- Silverstein M., Gans D., & Yang F. M (2006). Intergenerational support to aging parents: The role of norms and needs . Journal of Family Issues , 27 , 1068–1084. doi:10.1177/0192513X06288120 [ Google Scholar ]

- Simon R. W. (2002). Revisiting the relationships among gender, marital status, and mental health . The American Journal of Sociology , 107 , 1065–1096. doi:10.1086/339225 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stone P. (2007). Opting out? Why women really quit careers and head home . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Suitor J. J., Gilligan M., Pillemer K., Fingerman K. L., Kim K., Silverstein M., & Bengtson V. L (2017). Applying within-family differences approaches to enhance understanding of the complexity of intergenerational relations . Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , gbx037. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbx037 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Swartz T. (2009). Intergenerational family relations in adulthood: Patterns, variations, and implications in the contemporary United States . Annual Review of Sociology , 35 , 191–212. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134615 [ Google Scholar ]

- Symister P., & Friend R (2003). The influence of social support and problematic support on optimism and depression in chronic illness: A prospective study evaluating self-esteem as a mediator . Health Psychology , 22 , 123–129. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.22.2.123 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thoits P. A. (2010). Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 51 , S41–S53. doi:10.1177/0022146510383499 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thomas P. A. (2010). Is it better to give or to receive? Social support and the well-being of older adults . Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 65 , 351–357. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbp113 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thomas P. A. (2016). The impact of relationship-specific support and strain on depressive symptoms across the life course . Journal of Aging and Health , 28 , 363–382. doi:10.1177/0898264315591004 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thomas P. A., & Umberson D (2017). Do older parents’ relationships with their adult children affect cognitive limitations, and does this differ for mothers and fathers ? Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , gbx009. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbx009 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D., Crosnoe R., & Reczek C (2010). Social relationships and health behavior across the life course . Annual Review of Sociology, Vol 36 , 36 , 139–157. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120011 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D., & Montez J. K (2010). Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 51 , S54–S66. doi:10.1177/0022146510383501 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D., Pudrovska T., & Reczek C (2010). Parenthood, childlessness, and well-being: A life course perspective . Journal of Marriage and Family , 72 , 612–629. doi:10.1111/j.1741- 3737.2010.00721.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D., Thomeer M. B., Kroeger R. A., Lodge A. C., & Xu M (2015). Challenges and opportunities for research on same-sex relationships . Journal of Marriage and Family , 77 , 96–111. doi:10.1111/jomf.12155 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D., Thomeer M. B., Reczek C., & Donnelly R (2016). Physical illness in gay, lesbian, and heterosexual marriages: Gendered dyadic experiences . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 57 , 517. doi:10.1177/0022146516671570 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D., Williams K., Powers D. A., Liu H., & Needham B (2006). You make me sick: Marital quality and health over the life course . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 47 , 1–16. doi:10.1177/002214650604700101 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D., Williams K., Thomas P. A., Liu H., & Thomeer M. B (2014). Race, gender, and chains of disadvantage: Childhood adversity, social relationships, and health . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 55 , 20–38. doi:10.1177/ 0022146514521426 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Umberson D., Williams K., & Thomeer M. B (2013). Family status and mental health: Recent advances and future directions . In Aneshensel C. S. & Phelan J. C. (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (2nd edn, pp. 405–431). Dordrecht: Springer Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4276-5_20 [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Gundy K. T., Mills M. L., Tucker C. J., Rebellon C. J., Sharp E. H., & Stracuzzi N. F (2015). Socioeconomic strain, family ties, and adolescent health in a rural northeastern county . Rural Sociology , 80 , 60–85. doi:10.1111/ruso.12055 [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Volkom M. (2006). Sibling relationships in middle and older adulthood . Marriage & Family Review , 40 , 151–170. doi:10.1300/J002v40n02_08 [ Google Scholar ]

- Voorpostel M., & Blieszner R (2008). Intergenerational solidarity and support between adult siblings . Journal of Marriage and Family , 70 , 157–167. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00468.x [ Google Scholar ]

- Waite L. J., & Gallager M (2000). The case for marriage: Why married people are happier, healthier, and better off financially . New York: Doubleday. [ Google Scholar ]

- Waldinger R. J., Vaillant G. E., & Orav E. J (2007). Childhood sibling relationships as a predictor of major depression in adulthood: A 30-year prospective study . American Journal of Psychiatry , 164 , 949–954. doi:10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.949 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- White-Means S. I., & Rubin R. M (2008). Parent caregiving choices of middle-generation blacks and whites in the United States . Journal of Aging and Health , 20 , 560–582. doi:10.1177/0898264308317576 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Williams K. (2003). Has the future of marriage arrived? A contemporary examination of gender, marriage, and psychological well-being . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 44 , 470. doi:10.2307/1519794 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Williams K. (2004). The transition to widowhood and the social regulation of health: Consequences for health and health risk behavior . Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 59 , S343–S349. doi:10.1093/ geronb/59.6.S343 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Williams K., & Umberson D (2004). Marital status, marital transitions, and health: A gendered life course perspective . Journal of Health and Social Behavior , 45 , 81–98. doi:10.1177/002214650404500106 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Xu M., Thomas P. A., & Umberson D (2016). Marital quality and cognitive limitations in late life . The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences , 71 , 165–176. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv014 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang Z., & Hayward M. D (2006). Gender, the marital life course, and cardiovascular disease in late midlife . Journal of Marriage and Family , 68 , 639–657. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00280.x [ Google Scholar ]

Read our research on: TikTok | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Family & relationships, parents, young adult children and the transition to adulthood.

Most U.S. young adults are at least mostly financially independent and happy with their parents’ involvement in their lives. Parent-child relationships are mostly strong.

The Modern American Family: Key Trends in Marriage and Family Life

Working husbands in u.s. have more leisure time than working wives do, especially among those with children, how people around the world view same-sex marriage, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

All Family & Relationships Publications

How teens and parents approach screen time.

Most teens at least sometimes feel happy and peaceful when they don’t have their phone, but 44% say this makes them anxious. Half of parents say they have looked through their teen’s phone.

Most East Asian adults say men and women should share financial and caregiving duties

Around eight-in-ten adults in Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam say both men and women should be primarily responsible for earning money.

Among young adults without children, men are more likely than women to say they want to be parents someday

Among adults ages 18 to 34, 69% of those who have never been married say they want to get married one day.

Black Americans’ Views on Success in the U.S.

While Black adults define personal and financial success in different ways, most see these measures of success as major sources of pressure in their lives.

For Valentine’s Day, facts about marriage and dating in the U.S.

Overall, 69% of Americans say they are married (51%), living with a partner (11%), or otherwise in a committed romantic relationship (8%).

Most U.S. young adults are at least mostly financially independent and happy with their parents' involvement in their lives. Parent-child relationships are mostly strong.

A majority of Americans have a friend of a different religion

About six-in-ten U.S. adults say only some (43%) or hardly any or none (18%) of their friends have the same religion they do.

Striking findings from 2023

Here’s a look back at 2023 through some of our most striking research findings.

Across Asia, views of same-sex marriage vary widely

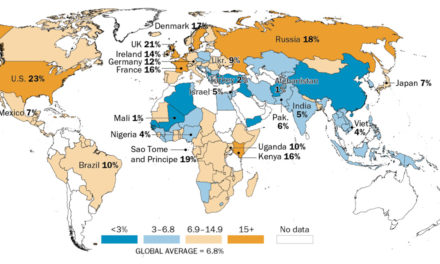

A median of 49% of people in 12 places in Asia say they at least somewhat favor allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally.

Among the 32 places surveyed, support for legal same-sex marriage is highest in Sweden, where 92% of adults favor it, and lowest in Nigeria, where only 2% back it.

Refine Your Results

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- Open access

- Published: 30 November 2020

Family perspectives of COVID-19 research

- Shelley M. Vanderhout 1 ,

- Catherine S. Birken 2 ,

- Peter Wong 3 ,

- Sarah Kelleher 4 ,

- Shannon Weir 4 &

- Jonathon L. Maguire 1 , 5

Research Involvement and Engagement volume 6 , Article number: 69 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

185k Accesses

19 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

The COVID-19 pandemic has uniquely affected children and families by disrupting routines, changing relationships and roles, and altering usual child care, school and recreational activities. Understanding the way families experience these changes from parents’ perspectives may help to guide research on the effects of COVID-19 among children.

As a multidisciplinary team of child health researchers, we assembled a group of nine parents to identify concerns, raise questions, and voice perspectives to inform COVID-19 research for children and families. Parents provided a range of insightful perspectives, ideas for research questions, and reflections on their experiences during the pandemic.

Including parents as partners in early stages of COVID-19 research helped determine priorities, led to more feasible data collection methods, and hopefully has improved the relevance, applicability and value of research findings to parents and children.

Peer Review reports

Plain English summary

Understanding the physical, mental, and emotional impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic for children and families will help to guide approaches to support families and children during the pandemic and after. As a team of child health researchers in Toronto, Canada, we assembled a group of parents and clinician researchers during the COVID-19 pandemic to identify concerns, raise questions, and voice perspectives to inform COVID-19 research for children and families. Parents were eager to share their experience of shifting roles, priorities, and routines during the pandemic, and were instrumental in guiding research priorities and methods to understand of the effects of COVID-19 on families. First-hand experience that parents have in navigating the COVID-19 pandemic with their families contributed to collaborative relationships between researchers and research participants, helped orient research about COVID-19 in children around family priorities, and offered valuable perspectives for the development of guidelines for safe return to school and childcare. Partnerships between researchers and families in designing and delivering COVID-19 research may lead to a better understanding of how health research can best support children and their families during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Children and families have been uniquely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. While children appear to experience milder symptoms from COVID-19 infection than older individuals [ 1 ], sudden changes in routines, resources, and relationships as a result of restrictions on physical interaction have resulted in major impacts on families with young children. In the absence of school, child care, extra-curricular activities and family gatherings, children’s social and support networks have been broadly disrupted. Stress from COVID-19 has been compounded by additional responsibilities for parents as they adapt to their new roles as educators and playmates while balancing full-time caregiving with their own stressful changes to work, financial and social situations. On the contrary, families with greater parental support and perceived control have had less perceived stress during COVID-19 [ 2 ].

The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly sparked research activity across the globe. Patient and family voices are increasingly considered essential to research agenda and priority setting [ 3 ]. Understanding the physical, mental, and emotional consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for families will inform approaches to support parents and children during the pandemic and after. In this unusual time, patient and family voices can be valuable in informing health research priorities, study designs, implementation plans and knowledge translation strategies that directly affect them [ 4 ].

As a multidisciplinary team of child health researchers with expertise in general paediatrics, nutrition and mental health, we assembled a group of nine parents to identify concerns, raise questions, and voice perspectives to inform COVID-19 research for children and families. Parents were recruited from the TARGet Kids! primary care research network [ 5 ], which is a collaboration between applied health researchers at the SickKids and St. Michael’s Hospitals, primary care providers from the Departments of Pediatrics and Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto, and families. Parents were contacted by email and invited to voluntary meetings on April 7 and 23, 2020 via Zoom [ 6 ] for 3 h. In an unstructured discussion, we asked how parents imagined research about COVID-19 could make an impact on child and family well-being. Parents were encouraged to share their lived experience and perspectives on the anticipated effects of COVID-19 and social distancing policies on their children and families, and opinions to inform how research on child mental and physical health during and after the pandemic could best be conducted. Parents had opportunities to review proposed data collection tools such as smartphone apps and serology testing devices, and provided feedback about the feasibility and meaningfulness of each. Content, frequency and organization of questionnaires were also reviewed by parents to ensure they were appropriate in length and feasible to complete.

Parent perspectives

Parents were optimistic that research would provide an understanding of the effects of COVID-19 on families and deliver solutions to minimize negative effects and bolster positive effects. Parents wondered about several questions which they hoped research would answer including: What will be the effects of physical distancing and disrupted routines for my children? How can I help my children develop healthy coping habits? How can I appropriately talk about the virus with my children? What factors might predict resiliency against negative effects of the pandemic among children and families, and how can these be strengthened?

Parents speculated what risks children might face as a result of schoolwork transitioning to home, educational activities provided online, child care being limited or unavailable, social relationships changing, sports and extra-curricular activities being cancelled, and stress and anxiety increasing at home. Some parents reflected on feeling some relief from not having to coordinate usual extracurricular activities. However, they expressed frustration in finding high quality educational activities and resources to support physical and mental health for their children during physical isolation. Parents voiced a need for a centralized, accessible hub with peer reviewed, high quality resources to keep children entertained and supported while spending more time indoors, away from usual activities and school. They hoped for resources to help families adjust to new routines and roles, as well as answer children’s questions in truthful ways that would not increase anxiety.