Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

Social media harms teens’ mental health, mounting evidence shows. what now.

Understanding what is going on in teens’ minds is necessary for targeted policy suggestions

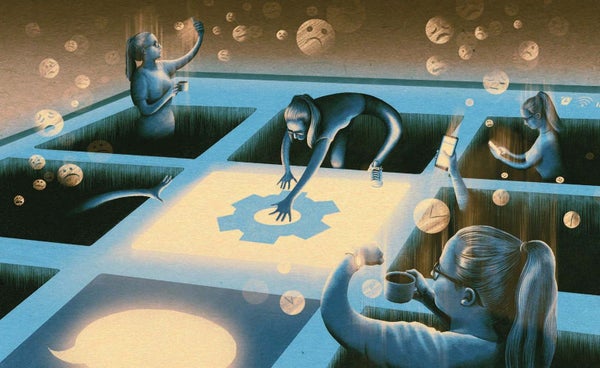

Most teens use social media, often for hours on end. Some social scientists are confident that such use is harming their mental health. Now they want to pinpoint what explains the link.

Carol Yepes/Getty Images

Share this:

By Sujata Gupta

February 20, 2024 at 7:30 am

In January, Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook’s parent company Meta, appeared at a congressional hearing to answer questions about how social media potentially harms children. Zuckerberg opened by saying: “The existing body of scientific work has not shown a causal link between using social media and young people having worse mental health.”

But many social scientists would disagree with that statement. In recent years, studies have started to show a causal link between teen social media use and reduced well-being or mood disorders, chiefly depression and anxiety.

Ironically, one of the most cited studies into this link focused on Facebook.

Researchers delved into whether the platform’s introduction across college campuses in the mid 2000s increased symptoms associated with depression and anxiety. The answer was a clear yes , says MIT economist Alexey Makarin, a coauthor of the study, which appeared in the November 2022 American Economic Review . “There is still a lot to be explored,” Makarin says, but “[to say] there is no causal evidence that social media causes mental health issues, to that I definitely object.”

The concern, and the studies, come from statistics showing that social media use in teens ages 13 to 17 is now almost ubiquitous. Two-thirds of teens report using TikTok, and some 60 percent of teens report using Instagram or Snapchat, a 2022 survey found. (Only 30 percent said they used Facebook.) Another survey showed that girls, on average, allot roughly 3.4 hours per day to TikTok, Instagram and Facebook, compared with roughly 2.1 hours among boys. At the same time, more teens are showing signs of depression than ever, especially girls ( SN: 6/30/23 ).

As more studies show a strong link between these phenomena, some researchers are starting to shift their attention to possible mechanisms. Why does social media use seem to trigger mental health problems? Why are those effects unevenly distributed among different groups, such as girls or young adults? And can the positives of social media be teased out from the negatives to provide more targeted guidance to teens, their caregivers and policymakers?

“You can’t design good public policy if you don’t know why things are happening,” says Scott Cunningham, an economist at Baylor University in Waco, Texas.

Increasing rigor

Concerns over the effects of social media use in children have been circulating for years, resulting in a massive body of scientific literature. But those mostly correlational studies could not show if teen social media use was harming mental health or if teens with mental health problems were using more social media.

Moreover, the findings from such studies were often inconclusive, or the effects on mental health so small as to be inconsequential. In one study that received considerable media attention, psychologists Amy Orben and Andrew Przybylski combined data from three surveys to see if they could find a link between technology use, including social media, and reduced well-being. The duo gauged the well-being of over 355,000 teenagers by focusing on questions around depression, suicidal thinking and self-esteem.

Digital technology use was associated with a slight decrease in adolescent well-being , Orben, now of the University of Cambridge, and Przybylski, of the University of Oxford, reported in 2019 in Nature Human Behaviour . But the duo downplayed that finding, noting that researchers have observed similar drops in adolescent well-being associated with drinking milk, going to the movies or eating potatoes.

Holes have begun to appear in that narrative thanks to newer, more rigorous studies.

In one longitudinal study, researchers — including Orben and Przybylski — used survey data on social media use and well-being from over 17,400 teens and young adults to look at how individuals’ responses to a question gauging life satisfaction changed between 2011 and 2018. And they dug into how the responses varied by gender, age and time spent on social media.

Social media use was associated with a drop in well-being among teens during certain developmental periods, chiefly puberty and young adulthood, the team reported in 2022 in Nature Communications . That translated to lower well-being scores around ages 11 to 13 for girls and ages 14 to 15 for boys. Both groups also reported a drop in well-being around age 19. Moreover, among the older teens, the team found evidence for the Goldilocks Hypothesis: the idea that both too much and too little time spent on social media can harm mental health.

“There’s hardly any effect if you look over everybody. But if you look at specific age groups, at particularly what [Orben] calls ‘windows of sensitivity’ … you see these clear effects,” says L.J. Shrum, a consumer psychologist at HEC Paris who was not involved with this research. His review of studies related to teen social media use and mental health is forthcoming in the Journal of the Association for Consumer Research.

Cause and effect

That longitudinal study hints at causation, researchers say. But one of the clearest ways to pin down cause and effect is through natural or quasi-experiments. For these in-the-wild experiments, researchers must identify situations where the rollout of a societal “treatment” is staggered across space and time. They can then compare outcomes among members of the group who received the treatment to those still in the queue — the control group.

That was the approach Makarin and his team used in their study of Facebook. The researchers homed in on the staggered rollout of Facebook across 775 college campuses from 2004 to 2006. They combined that rollout data with student responses to the National College Health Assessment, a widely used survey of college students’ mental and physical health.

The team then sought to understand if those survey questions captured diagnosable mental health problems. Specifically, they had roughly 500 undergraduate students respond to questions both in the National College Health Assessment and in validated screening tools for depression and anxiety. They found that mental health scores on the assessment predicted scores on the screenings. That suggested that a drop in well-being on the college survey was a good proxy for a corresponding increase in diagnosable mental health disorders.

Compared with campuses that had not yet gained access to Facebook, college campuses with Facebook experienced a 2 percentage point increase in the number of students who met the diagnostic criteria for anxiety or depression, the team found.

When it comes to showing a causal link between social media use in teens and worse mental health, “that study really is the crown jewel right now,” says Cunningham, who was not involved in that research.

A need for nuance

The social media landscape today is vastly different than the landscape of 20 years ago. Facebook is now optimized for maximum addiction, Shrum says, and other newer platforms, such as Snapchat, Instagram and TikTok, have since copied and built on those features. Paired with the ubiquity of social media in general, the negative effects on mental health may well be larger now.

Moreover, social media research tends to focus on young adults — an easier cohort to study than minors. That needs to change, Cunningham says. “Most of us are worried about our high school kids and younger.”

And so, researchers must pivot accordingly. Crucially, simple comparisons of social media users and nonusers no longer make sense. As Orben and Przybylski’s 2022 work suggested, a teen not on social media might well feel worse than one who briefly logs on.

Researchers must also dig into why, and under what circumstances, social media use can harm mental health, Cunningham says. Explanations for this link abound. For instance, social media is thought to crowd out other activities or increase people’s likelihood of comparing themselves unfavorably with others. But big data studies, with their reliance on existing surveys and statistical analyses, cannot address those deeper questions. “These kinds of papers, there’s nothing you can really ask … to find these plausible mechanisms,” Cunningham says.

One ongoing effort to understand social media use from this more nuanced vantage point is the SMART Schools project out of the University of Birmingham in England. Pedagogical expert Victoria Goodyear and her team are comparing mental and physical health outcomes among children who attend schools that have restricted cell phone use to those attending schools without such a policy. The researchers described the protocol of that study of 30 schools and over 1,000 students in the July BMJ Open.

Goodyear and colleagues are also combining that natural experiment with qualitative research. They met with 36 five-person focus groups each consisting of all students, all parents or all educators at six of those schools. The team hopes to learn how students use their phones during the day, how usage practices make students feel, and what the various parties think of restrictions on cell phone use during the school day.

Talking to teens and those in their orbit is the best way to get at the mechanisms by which social media influences well-being — for better or worse, Goodyear says. Moving beyond big data to this more personal approach, however, takes considerable time and effort. “Social media has increased in pace and momentum very, very quickly,” she says. “And research takes a long time to catch up with that process.”

Until that catch-up occurs, though, researchers cannot dole out much advice. “What guidance could we provide to young people, parents and schools to help maintain the positives of social media use?” Goodyear asks. “There’s not concrete evidence yet.”

More Stories from Science News on Science & Society

Separating science fact from fiction in Netflix’s ‘3 Body Problem’

Language models may miss signs of depression in Black people’s Facebook posts

Aimee Grant investigates the needs of autistic people

In ‘Get the Picture,’ science helps explore the meaning of art

What Science News saw during the solar eclipse

During the awe of totality, scientists studied our planet’s reactions

Your last-minute guide to the 2024 total solar eclipse

Protein whisperer Oluwatoyin Asojo fights neglected diseases

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

Skip to content

Read the latest news stories about Mailman faculty, research, and events.

Departments

We integrate an innovative skills-based curriculum, research collaborations, and hands-on field experience to prepare students.

Learn more about our research centers, which focus on critical issues in public health.

Our Faculty

Meet the faculty of the Mailman School of Public Health.

Become a Student

Life and community, how to apply.

Learn how to apply to the Mailman School of Public Health.

Just How Harmful Is Social Media? Our Experts Weigh-In.

A recent investigation by the Wall Street Journal revealed that Facebook was aware of mental health risks linked to the use of its Instagram app but kept those findings secret. Internal research by the social media giant found that Instagram worsened body image issues for one in three teenage girls, and all teenage users of the app linked it to experiences of anxiety and depression. It isn’t the first evidence of social media’s harms. Watchdog groups have identified Facebook and Instagram as avenues for cyberbullying , and reports have linked TikTok to dangerous and antisocial behavior, including a recent spate of school vandalism .

As social media has proliferated worldwide—Facebook has 2.85 billion users—so too have concerns over how the platforms are affecting individual and collective wellbeing. Social media is criticized for being addictive by design and for its role in the spread of misinformation on critical issues from vaccine safety to election integrity, as well as the rise of right-wing extremism. Social media companies, and many users, defend the platforms as avenues for promoting creativity and community-building. And some research has pushed back against the idea that social media raises the risk for depression in teens . So just how healthy or unhealthy is social media?

Two experts from Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and Columbia Psychiatry share their insights into one crucial aspect of social media’s influence—its effect on the mental health of young people and adults. Deborah Glasofer , associate professor of psychology in psychiatry, conducts psychotherapy development research for adults with eating disorders and teaches about cognitive behavioral therapy. She is the co-author of the book Eating Disorders: What Everyone Needs to Know. Claude Mellins , Professor of medical psychology in the Departments of Psychiatry and Sociomedical Sciences, studies wellbeing among college and graduate students, among other topics, and serves as program director of CopeColumbia, a peer support program for Columbia faculty and staff whose mental health has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. She co-led the SHIFT research study to reduce sexual violence among undergraduates. Both use social media.

What do we know about the mental health risks of social media use?

Mellins : Facebook and Instagram and other social media platforms are important sources of socialization and relationship-building for many young people. Although there are important benefits, social media can also provide platforms for bullying and exclusion, unrealistic expectations about body image and sources of popularity, normalization of risk-taking behaviors, and can be detrimental to mental health. Girls and young people who identify as sexual and gender minorities can be especially vulnerable as targets. Young people’s brains are still developing, and as individuals, young people are developing their own identities. What they see on social media can define what is expected in ways that is not accurate and that can be destructive to identity development and self-image. Adolescence is a time of risk-taking, which is both a strength and a vulnerability. Social media can exacerbate risks, as we have seen played out in the news.

Although there are important benefits, social media can also provide platforms for bullying and exclusion, unrealistic expectations about body image and sources of popularity, normalization of risk-taking behaviors, and can be detrimental to mental health. – Claude Mellins

Glasofer : For those vulnerable to developing an eating disorder, social media may be especially unhelpful because it allows people to easily compare their appearance to their friends, to celebrities, even older images of themselves. Research tells us that how much someone engages with photo-related activities like posting and sharing photos on Facebook or Instagram is associated with less body acceptance and more obsessing about appearance. For adolescent girls in particular, the more time they spend on social media directly relates to how much they absorb the idea that being thin is ideal, are driven to try to become thin, and/or overly scrutinize their own bodies. Also, if someone is vulnerable to an eating disorder, they may be especially attracted to seeking out unhelpful information—which is all too easy to find on social media.

Are there any upsides to social media?

Mellins : For young people, social media provides a platform to help them figure out who they are. For very shy or introverted young people, it can be a way to meet others with similar interests. During the pandemic, social media made it possible for people to connect in ways when in-person socialization was not possible. Social support and socializing are critical influences on coping and resilience. Friends we couldn’t see in person were available online and allowed us important points of connection. On the other hand, fewer opportunities for in-person interactions with friends and family meant less of a real-world check on some of the negative influences of social media.

Whether it’s social media or in person, a good peer group makes the difference. A group of friends that connects over shared interests like art or music, and is balanced in their outlook on eating and appearance, is a positive. – Deborah Glasofer

Glasofer : Whether it’s social media or in person, a good peer group makes the difference. A group of friends that connects over shared interests like art or music, and is balanced in their outlook on eating and appearance, is a positive. In fact, a good peer group online may be protective against negative in-person influences. For those with a history of eating disorders, there are body-positive and recovery groups on social media. Some people find these groups to be supportive; for others, it’s more beneficial to move on and pursue other interests.

Is there a healthy way to be on social media?

Mellins : If you feel social media is a negative experience, you might need a break. Disengaging with social media permanently is more difficult—especially for young people. These platforms are powerful tools for connecting and staying up-to-date with friends and family. Social events, too. If you’re not on social media then you’re reliant on your friends to reach out to you personally, which doesn’t always happen. It’s complicated.

Glasofer : When you find yourself feeling badly about yourself in relation to what other people are posting about themselves, then social media is not doing you any favors. If there is anything on social media that is negatively affecting your actions or your choices—for example, if you’re starting to eat restrictively or exercise excessively—then it’s time to reassess. Parents should check-in with their kids about their lives on social media. In general, I recommend limiting social media— creating boundaries that are reasonable and work for you—so you can be present with people in your life. I also recommend social media vacations. It’s good to take the time to notice the difference between the virtual world and the real world.

Is social media use bad for young people’s mental health? It’s complicated.

July 17, 2023 – On May 23, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued an advisory warning about the potential dangers of social media for the mental health of children and teens . Laura Marciano , postdoctoral research fellow at the Lee Kum Sheung Center for Health and Happiness and in the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, says that social media use might be detrimental for young people’s well-being but can also have positive effects.

Q: What are your thoughts on the Surgeon General’s advisory?

A: The advisory highlighted compelling evidence published during the last decade on the potential harmful impact of social media on children and adolescents. Some of what young people experience online—including cyberbullying, online harassment and abuse, predatory behaviors, and exposure to violent, sexual, and hate-based content—can undoubtedly be negative. But social media experiences are not limited to these types of content.

Much of the scientific literature on the effects of social media use has focused on negative outcomes. But the link between social media use and young people’s mental health is complicated. Literature reviews show that study results are mixed: Associations between social media use and well-being can be positive, negative, and even largely null when advanced data analyses are carried out, and the size of the effects is small. And positive and negative effects can co-exist in the same individual. We are still discovering how to compare the effect size of social media use with the effects of other behavioral habits—such as physical activity, sleep, food consumption, life events, and time spent in offline social connections—and psychological processes happening offline. We are also still studying how social media use may be linked positively with well-being.

It’s important to note that many of the existing studies relied on data from people living in so-called WEIRD countries (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic), thus leaving out the majority of the worldwide population living in the Global South. In addition, we know that populations like minorities, people experiencing health disparities and chronic health conditions , and international students can find social media extremely helpful for creating and maintaining social communities to which they feel they belong.

A number of large cohort studies have measured social media use according to time spent on various platforms. But it’s important to consider not just time spent, but whether that time is displacing time for other activities promoting well-being, like physical activity and sleep. Finally, the effects of social media use are idiosyncratic, meaning that each child and adolescent might be affected differently, which makes it difficult to generalize about the effects.

Literature reviews on interventions limiting social media use present a more balanced picture. For example, one comprehensive review on the effects of digital detox—refraining from using devices such as smartphones—wasn’t able to draw any clear conclusions about whether such detox could be effective at promoting a healthy way of life in the digital era, because the findings were mixed and contradictory.

Q: What has your research found regarding the potential risks and benefits of social media use among young people?

A: In my work with Prof. Vish Viswanath , we have summarized all the papers on how social media use is related to positive well-being measures, to balance the ongoing bias of the literature on negative outcomes such as depression and anxiety. We found both positive and negative correlations between different social media activities and well-being. The most consistent results show a link between social media activities and hedonic well-being (positive emotions) and social well-being. We also found that social comparison—such as comparing how many likes you have with how many someone else has, or comparing yourself to digitally enhanced images online—drives the negative correlation with well-being.

Meanwhile, I am working on the “ HappyB ” project, a longitudinal project based in Switzerland, through which I have collected data from more than 1,500 adolescents on their smartphone and social media use and well-being. In a recent study using that cohort, we looked at how social media use affects flourishing , a construct that encompasses happiness, meaning and purpose, physical and mental health, character, close social relationships, and financial stability. We found that certain positive social media experiences are associated with flourishing. In particular, having someone to talk to online when feeling lonely was the item most related to well-being. That is not surprising, considering that happiness is related to the quality of social connections.

Our data suggest that homing in on the psychological processes triggered during social media use is key to determining links with well-being. For example, we should consider if a young person feels appreciated and part of a group in a particular online conversation. Such information can help us shed light on the dynamics that shape young people’s well-being through digital activities.

In our research, we work to account for the fact that social media time is a sedentary behavior. We need to consider that any behavior that risks diminishing the time spent on physical activity and sleep—crucial components of brain development and well-being—might be detrimental. Interestingly, some studies suggest that spending a short amount of time using social media, around 1-2 hours, is beneficial, but—as with any extreme behavior—it can cause harm if the time spent online dominates a child’s or adolescent’s day.

It’s also important to consider how long the effects of social media last. Social media use may have small ephemeral effects that can accumulate over time. A step for future research is to disentangle short- versus long-term effects and how long each last. In addition, we should better understand how digital media usage affects the adolescent brain. Colleagues and I have summarized existing neuroscientific studies on the topic, but more multidisciplinary research is needed.

Q: What are some steps you’d recommend to make social media use safer for kids?

A: I’ll use a metaphor to answer this question. Is a car safe for someone that is not able to drive? To drive safely, we need to learn how to accelerate, recognize road signs, make safe decisions according to certain rules, and wear safety belts. Similarly, to use social media safely, I think we as a society—including schools, educators, and health providers—should provide children and families with clear, science-based information on both its positive and negative potential impacts.

We can also ask social media companies to pay more attention to how some features—such as the number of “likes”—can modulate adolescent brain activity, and to think about ways to limit negative effects. We might even ask adolescents to advise designers on how to create social media platforms specifically for them. It would be extremely valuable to ask them which features would be best for them and which ones they would like to avoid. I think that co-designing apps and conducting research with the young people who use the platforms is a crucial step.

For parents, my suggestion is to communicate with your children and promote a climate of safety and empathy when it comes to social media use. Try to use these platforms along with them, for example by explaining how a platform works and commenting on the content. Also, I would encourage schools and parents to collaborate on sharing information with young people about social media and well-being.

Also, to offset children’s sedentary time spent on social media, parents could offer them alternative extracurricular activities to provide some balance. But it’s important to remember that social well-being depends on the quality of social connections, and that social media can help to promote this kind of well-being. So I’d recommend trying to keep what is good—according to my research that would include instant messaging, the chance to talk to people when someone is feeling lonely, and funny or inspirational content—and minimizing what’s negative, such as too much sedentary time or too much time spent on social comparison.

– Karen Feldscher

Find anything you save across the site in your account

All products are independently selected by our editors. If you buy something, we may earn an affiliate commission.

How Harmful Is Social Media?

By Gideon Lewis-Kraus

In April, the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt published an essay in The Atlantic in which he sought to explain, as the piece’s title had it, “Why the Past 10 Years of American Life Have Been Uniquely Stupid.” Anyone familiar with Haidt’s work in the past half decade could have anticipated his answer: social media. Although Haidt concedes that political polarization and factional enmity long predate the rise of the platforms, and that there are plenty of other factors involved, he believes that the tools of virality—Facebook’s Like and Share buttons, Twitter’s Retweet function—have algorithmically and irrevocably corroded public life. He has determined that a great historical discontinuity can be dated with some precision to the period between 2010 and 2014, when these features became widely available on phones.

“What changed in the 2010s?” Haidt asks, reminding his audience that a former Twitter developer had once compared the Retweet button to the provision of a four-year-old with a loaded weapon. “A mean tweet doesn’t kill anyone; it is an attempt to shame or punish someone publicly while broadcasting one’s own virtue, brilliance, or tribal loyalties. It’s more a dart than a bullet, causing pain but no fatalities. Even so, from 2009 to 2012, Facebook and Twitter passed out roughly a billion dart guns globally. We’ve been shooting one another ever since.” While the right has thrived on conspiracy-mongering and misinformation, the left has turned punitive: “When everyone was issued a dart gun in the early 2010s, many left-leaning institutions began shooting themselves in the brain. And, unfortunately, those were the brains that inform, instruct, and entertain most of the country.” Haidt’s prevailing metaphor of thoroughgoing fragmentation is the story of the Tower of Babel: the rise of social media has “unwittingly dissolved the mortar of trust, belief in institutions, and shared stories that had held a large and diverse secular democracy together.”

These are, needless to say, common concerns. Chief among Haidt’s worries is that use of social media has left us particularly vulnerable to confirmation bias, or the propensity to fix upon evidence that shores up our prior beliefs. Haidt acknowledges that the extant literature on social media’s effects is large and complex, and that there is something in it for everyone. On January 6, 2021, he was on the phone with Chris Bail, a sociologist at Duke and the author of the recent book “ Breaking the Social Media Prism ,” when Bail urged him to turn on the television. Two weeks later, Haidt wrote to Bail, expressing his frustration at the way Facebook officials consistently cited the same handful of studies in their defense. He suggested that the two of them collaborate on a comprehensive literature review that they could share, as a Google Doc, with other researchers. (Haidt had experimented with such a model before.) Bail was cautious. He told me, “What I said to him was, ‘Well, you know, I’m not sure the research is going to bear out your version of the story,’ and he said, ‘Why don’t we see?’ ”

Bail emphasized that he is not a “platform-basher.” He added, “In my book, my main take is, Yes, the platforms play a role, but we are greatly exaggerating what it’s possible for them to do—how much they could change things no matter who’s at the helm at these companies—and we’re profoundly underestimating the human element, the motivation of users.” He found Haidt’s idea of a Google Doc appealing, in the way that it would produce a kind of living document that existed “somewhere between scholarship and public writing.” Haidt was eager for a forum to test his ideas. “I decided that if I was going to be writing about this—what changed in the universe, around 2014, when things got weird on campus and elsewhere—once again, I’d better be confident I’m right,” he said. “I can’t just go off my feelings and my readings of the biased literature. We all suffer from confirmation bias, and the only cure is other people who don’t share your own.”

Haidt and Bail, along with a research assistant, populated the document over the course of several weeks last year, and in November they invited about two dozen scholars to contribute. Haidt told me, of the difficulties of social-scientific methodology, “When you first approach a question, you don’t even know what it is. ‘Is social media destroying democracy, yes or no?’ That’s not a good question. You can’t answer that question. So what can you ask and answer?” As the document took on a life of its own, tractable rubrics emerged—Does social media make people angrier or more affectively polarized? Does it create political echo chambers? Does it increase the probability of violence? Does it enable foreign governments to increase political dysfunction in the United States and other democracies? Haidt continued, “It’s only after you break it up into lots of answerable questions that you see where the complexity lies.”

Haidt came away with the sense, on balance, that social media was in fact pretty bad. He was disappointed, but not surprised, that Facebook’s response to his article relied on the same three studies they’ve been reciting for years. “This is something you see with breakfast cereals,” he said, noting that a cereal company “might say, ‘Did you know we have twenty-five per cent more riboflavin than the leading brand?’ They’ll point to features where the evidence is in their favor, which distracts you from the over-all fact that your cereal tastes worse and is less healthy.”

After Haidt’s piece was published, the Google Doc—“Social Media and Political Dysfunction: A Collaborative Review”—was made available to the public . Comments piled up, and a new section was added, at the end, to include a miscellany of Twitter threads and Substack essays that appeared in response to Haidt’s interpretation of the evidence. Some colleagues and kibbitzers agreed with Haidt. But others, though they might have shared his basic intuition that something in our experience of social media was amiss, drew upon the same data set to reach less definitive conclusions, or even mildly contradictory ones. Even after the initial flurry of responses to Haidt’s article disappeared into social-media memory, the document, insofar as it captured the state of the social-media debate, remained a lively artifact.

Near the end of the collaborative project’s introduction, the authors warn, “We caution readers not to simply add up the number of studies on each side and declare one side the winner.” The document runs to more than a hundred and fifty pages, and for each question there are affirmative and dissenting studies, as well as some that indicate mixed results. According to one paper, “Political expressions on social media and the online forum were found to (a) reinforce the expressers’ partisan thought process and (b) harden their pre-existing political preferences,” but, according to another, which used data collected during the 2016 election, “Over the course of the campaign, we found media use and attitudes remained relatively stable. Our results also showed that Facebook news use was related to modest over-time spiral of depolarization. Furthermore, we found that people who use Facebook for news were more likely to view both pro- and counter-attitudinal news in each wave. Our results indicated that counter-attitudinal exposure increased over time, which resulted in depolarization.” If results like these seem incompatible, a perplexed reader is given recourse to a study that says, “Our findings indicate that political polarization on social media cannot be conceptualized as a unified phenomenon, as there are significant cross-platform differences.”

Interested in echo chambers? “Our results show that the aggregation of users in homophilic clusters dominate online interactions on Facebook and Twitter,” which seems convincing—except that, as another team has it, “We do not find evidence supporting a strong characterization of ‘echo chambers’ in which the majority of people’s sources of news are mutually exclusive and from opposite poles.” By the end of the file, the vaguely patronizing top-line recommendation against simple summation begins to make more sense. A document that originated as a bulwark against confirmation bias could, as it turned out, just as easily function as a kind of generative device to support anybody’s pet conviction. The only sane response, it seemed, was simply to throw one’s hands in the air.

When I spoke to some of the researchers whose work had been included, I found a combination of broad, visceral unease with the current situation—with the banefulness of harassment and trolling; with the opacity of the platforms; with, well, the widespread presentiment that of course social media is in many ways bad—and a contrastive sense that it might not be catastrophically bad in some of the specific ways that many of us have come to take for granted as true. This was not mere contrarianism, and there was no trace of gleeful mythbusting; the issue was important enough to get right. When I told Bail that the upshot seemed to me to be that exactly nothing was unambiguously clear, he suggested that there was at least some firm ground. He sounded a bit less apocalyptic than Haidt.

“A lot of the stories out there are just wrong,” he told me. “The political echo chamber has been massively overstated. Maybe it’s three to five per cent of people who are properly in an echo chamber.” Echo chambers, as hotboxes of confirmation bias, are counterproductive for democracy. But research indicates that most of us are actually exposed to a wider range of views on social media than we are in real life, where our social networks—in the original use of the term—are rarely heterogeneous. (Haidt told me that this was an issue on which the Google Doc changed his mind; he became convinced that echo chambers probably aren’t as widespread a problem as he’d once imagined.) And too much of a focus on our intuitions about social media’s echo-chamber effect could obscure the relevant counterfactual: a conservative might abandon Twitter only to watch more Fox News. “Stepping outside your echo chamber is supposed to make you moderate, but maybe it makes you more extreme,” Bail said. The research is inchoate and ongoing, and it’s difficult to say anything on the topic with absolute certainty. But this was, in part, Bail’s point: we ought to be less sure about the particular impacts of social media.

Bail went on, “The second story is foreign misinformation.” It’s not that misinformation doesn’t exist, or that it hasn’t had indirect effects, especially when it creates perverse incentives for the mainstream media to cover stories circulating online. Haidt also draws convincingly upon the work of Renée DiResta, the research manager at the Stanford Internet Observatory, to sketch out a potential future in which the work of shitposting has been outsourced to artificial intelligence, further polluting the informational environment. But, at least so far, very few Americans seem to suffer from consistent exposure to fake news—“probably less than two per cent of Twitter users, maybe fewer now, and for those who were it didn’t change their opinions,” Bail said. This was probably because the people likeliest to consume such spectacles were the sort of people primed to believe them in the first place. “In fact,” he said, “echo chambers might have done something to quarantine that misinformation.”

The final story that Bail wanted to discuss was the “proverbial rabbit hole, the path to algorithmic radicalization,” by which YouTube might serve a viewer increasingly extreme videos. There is some anecdotal evidence to suggest that this does happen, at least on occasion, and such anecdotes are alarming to hear. But a new working paper led by Brendan Nyhan, a political scientist at Dartmouth, found that almost all extremist content is either consumed by subscribers to the relevant channels—a sign of actual demand rather than manipulation or preference falsification—or encountered via links from external sites. It’s easy to see why we might prefer if this were not the case: algorithmic radicalization is presumably a simpler problem to solve than the fact that there are people who deliberately seek out vile content. “These are the three stories—echo chambers, foreign influence campaigns, and radicalizing recommendation algorithms—but, when you look at the literature, they’ve all been overstated.” He thought that these findings were crucial for us to assimilate, if only to help us understand that our problems may lie beyond technocratic tinkering. He explained, “Part of my interest in getting this research out there is to demonstrate that everybody is waiting for an Elon Musk to ride in and save us with an algorithm”—or, presumably, the reverse—“and it’s just not going to happen.”

When I spoke with Nyhan, he told me much the same thing: “The most credible research is way out of line with the takes.” He noted, of extremist content and misinformation, that reliable research that “measures exposure to these things finds that the people consuming this content are small minorities who have extreme views already.” The problem with the bulk of the earlier research, Nyhan told me, is that it’s almost all correlational. “Many of these studies will find polarization on social media,” he said. “But that might just be the society we live in reflected on social media!” He hastened to add, “Not that this is untroubling, and none of this is to let these companies, which are exercising a lot of power with very little scrutiny, off the hook. But a lot of the criticisms of them are very poorly founded. . . . The expansion of Internet access coincides with fifteen other trends over time, and separating them is very difficult. The lack of good data is a huge problem insofar as it lets people project their own fears into this area.” He told me, “It’s hard to weigh in on the side of ‘We don’t know, the evidence is weak,’ because those points are always going to be drowned out in our discourse. But these arguments are systematically underprovided in the public domain.”

In his Atlantic article, Haidt leans on a working paper by two social scientists, Philipp Lorenz-Spreen and Lisa Oswald, who took on a comprehensive meta-analysis of about five hundred papers and concluded that “the large majority of reported associations between digital media use and trust appear to be detrimental for democracy.” Haidt writes, “The literature is complex—some studies show benefits, particularly in less developed democracies—but the review found that, on balance, social media amplifies political polarization; foments populism, especially right-wing populism; and is associated with the spread of misinformation.” Nyhan was less convinced that the meta-analysis supported such categorical verdicts, especially once you bracketed the kinds of correlational findings that might simply mirror social and political dynamics. He told me, “If you look at their summary of studies that allow for causal inferences—it’s very mixed.”

As for the studies Nyhan considered most methodologically sound, he pointed to a 2020 article called “The Welfare Effects of Social Media,” by Hunt Allcott, Luca Braghieri, Sarah Eichmeyer, and Matthew Gentzkow. For four weeks prior to the 2018 midterm elections, the authors randomly divided a group of volunteers into two cohorts—one that continued to use Facebook as usual, and another that was paid to deactivate their accounts for that period. They found that deactivation “(i) reduced online activity, while increasing offline activities such as watching TV alone and socializing with family and friends; (ii) reduced both factual news knowledge and political polarization; (iii) increased subjective well-being; and (iv) caused a large persistent reduction in post-experiment Facebook use.” But Gentzkow reminded me that his conclusions, including that Facebook may slightly increase polarization, had to be heavily qualified: “From other kinds of evidence, I think there’s reason to think social media is not the main driver of increasing polarization over the long haul in the United States.”

In the book “ Why We’re Polarized ,” for example, Ezra Klein invokes the work of such scholars as Lilliana Mason to argue that the roots of polarization might be found in, among other factors, the political realignment and nationalization that began in the sixties, and were then sacralized, on the right, by the rise of talk radio and cable news. These dynamics have served to flatten our political identities, weakening our ability or inclination to find compromise. Insofar as some forms of social media encourage the hardening of connections between our identities and a narrow set of opinions, we might increasingly self-select into mutually incomprehensible and hostile groups; Haidt plausibly suggests that these processes are accelerated by the coalescence of social-media tribes around figures of fearful online charisma. “Social media might be more of an amplifier of other things going on rather than a major driver independently,” Gentzkow argued. “I think it takes some gymnastics to tell a story where it’s all primarily driven by social media, especially when you’re looking at different countries, and across different groups.”

Another study, led by Nejla Asimovic and Joshua Tucker, replicated Gentzkow’s approach in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and they found almost precisely the opposite results: the people who stayed on Facebook were, by the end of the study, more positively disposed to their historic out-groups. The authors’ interpretation was that ethnic groups have so little contact in Bosnia that, for some people, social media is essentially the only place where they can form positive images of one another. “To have a replication and have the signs flip like that, it’s pretty stunning,” Bail told me. “It’s a different conversation in every part of the world.”

Nyhan argued that, at least in wealthy Western countries, we might be too heavily discounting the degree to which platforms have responded to criticism: “Everyone is still operating under the view that algorithms simply maximize engagement in a short-term way” with minimal attention to potential externalities. “That might’ve been true when Zuckerberg had seven people working for him, but there are a lot of considerations that go into these rankings now.” He added, “There’s some evidence that, with reverse-chronological feeds”—streams of unwashed content, which some critics argue are less manipulative than algorithmic curation—“people get exposed to more low-quality content, so it’s another case where a very simple notion of ‘algorithms are bad’ doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. It doesn’t mean they’re good, it’s just that we don’t know.”

Bail told me that, over all, he was less confident than Haidt that the available evidence lines up clearly against the platforms. “Maybe there’s a slight majority of studies that say that social media is a net negative, at least in the West, and maybe it’s doing some good in the rest of the world.” But, he noted, “Jon will say that science has this expectation of rigor that can’t keep up with the need in the real world—that even if we don’t have the definitive study that creates the historical counterfactual that Facebook is largely responsible for polarization in the U.S., there’s still a lot pointing in that direction, and I think that’s a fair point.” He paused. “It can’t all be randomized control trials.”

Haidt comes across in conversation as searching and sincere, and, during our exchange, he paused several times to suggest that I include a quote from John Stuart Mill on the importance of good-faith debate to moral progress. In that spirit, I asked him what he thought of the argument, elaborated by some of Haidt’s critics, that the problems he described are fundamentally political, social, and economic, and that to blame social media is to search for lost keys under the streetlamp, where the light is better. He agreed that this was the steelman opponent: there were predecessors for cancel culture in de Tocqueville, and anxiety about new media that went back to the time of the printing press. “This is a perfectly reasonable hypothesis, and it’s absolutely up to the prosecution—people like me—to argue that, no, this time it’s different. But it’s a civil case! The evidential standard is not ‘beyond a reasonable doubt,’ as in a criminal case. It’s just a preponderance of the evidence.”

The way scholars weigh the testimony is subject to their disciplinary orientations. Economists and political scientists tend to believe that you can’t even begin to talk about causal dynamics without a randomized controlled trial, whereas sociologists and psychologists are more comfortable drawing inferences on a correlational basis. Haidt believes that conditions are too dire to take the hardheaded, no-reasonable-doubt view. “The preponderance of the evidence is what we use in public health. If there’s an epidemic—when COVID started, suppose all the scientists had said, ‘No, we gotta be so certain before you do anything’? We have to think about what’s actually happening, what’s likeliest to pay off.” He continued, “We have the largest epidemic ever of teen mental health, and there is no other explanation,” he said. “It is a raging public-health epidemic, and the kids themselves say Instagram did it, and we have some evidence, so is it appropriate to say, ‘Nah, you haven’t proven it’?”

This was his attitude across the board. He argued that social media seemed to aggrandize inflammatory posts and to be correlated with a rise in violence; even if only small groups were exposed to fake news, such beliefs might still proliferate in ways that were hard to measure. “In the post-Babel era, what matters is not the average but the dynamics, the contagion, the exponential amplification,” he said. “Small things can grow very quickly, so arguments that Russian disinformation didn’t matter are like COVID arguments that people coming in from China didn’t have contact with a lot of people.” Given the transformative effects of social media, Haidt insisted, it was important to act now, even in the absence of dispositive evidence. “Academic debates play out over decades and are often never resolved, whereas the social-media environment changes year by year,” he said. “We don’t have the luxury of waiting around five or ten years for literature reviews.”

Haidt could be accused of question-begging—of assuming the existence of a crisis that the research might or might not ultimately underwrite. Still, the gap between the two sides in this case might not be quite as wide as Haidt thinks. Skeptics of his strongest claims are not saying that there’s no there there. Just because the average YouTube user is unlikely to be led to Stormfront videos, Nyhan told me, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t worry that some people are watching Stormfront videos; just because echo chambers and foreign misinformation seem to have had effects only at the margins, Gentzkow said, doesn’t mean they’re entirely irrelevant. “There are many questions here where the thing we as researchers are interested in is how social media affects the average person,” Gentzkow told me. “There’s a different set of questions where all you need is a small number of people to change—questions about ethnic violence in Bangladesh or Sri Lanka, people on YouTube mobilized to do mass shootings. Much of the evidence broadly makes me skeptical that the average effects are as big as the public discussion thinks they are, but I also think there are cases where a small number of people with very extreme views are able to find each other and connect and act.” He added, “That’s where many of the things I’d be most concerned about lie.”

The same might be said about any phenomenon where the base rate is very low but the stakes are very high, such as teen suicide. “It’s another case where those rare edge cases in terms of total social harm may be enormous. You don’t need many teen-age kids to decide to kill themselves or have serious mental-health outcomes in order for the social harm to be really big.” He added, “Almost none of this work is able to get at those edge-case effects, and we have to be careful that if we do establish that the average effect of something is zero, or small, that it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be worried about it—because we might be missing those extremes.” Jaime Settle, a scholar of political behavior at the College of William & Mary and the author of the book “ Frenemies: How Social Media Polarizes America ,” noted that Haidt is “farther along the spectrum of what most academics who study this stuff are going to say we have strong evidence for.” But she understood his impulse: “We do have serious problems, and I’m glad Jon wrote the piece, and down the road I wouldn’t be surprised if we got a fuller handle on the role of social media in all of this—there are definitely ways in which social media has changed our politics for the worse.”

It’s tempting to sidestep the question of diagnosis entirely, and to evaluate Haidt’s essay not on the basis of predictive accuracy—whether social media will lead to the destruction of American democracy—but as a set of proposals for what we might do better. If he is wrong, how much damage are his prescriptions likely to do? Haidt, to his great credit, does not indulge in any wishful thinking, and if his diagnosis is largely technological his prescriptions are sociopolitical. Two of his three major suggestions seem useful and have nothing to do with social media: he thinks that we should end closed primaries and that children should be given wide latitude for unsupervised play. His recommendations for social-media reform are, for the most part, uncontroversial: he believes that preteens shouldn’t be on Instagram and that platforms should share their data with outside researchers—proposals that are both likely to be beneficial and not very costly.

It remains possible, however, that the true costs of social-media anxieties are harder to tabulate. Gentzkow told me that, for the period between 2016 and 2020, the direct effects of misinformation were difficult to discern. “But it might have had a much larger effect because we got so worried about it—a broader impact on trust,” he said. “Even if not that many people were exposed, the narrative that the world is full of fake news, and you can’t trust anything, and other people are being misled about it—well, that might have had a bigger impact than the content itself.” Nyhan had a similar reaction. “There are genuine questions that are really important, but there’s a kind of opportunity cost that is missed here. There’s so much focus on sweeping claims that aren’t actionable, or unfounded claims we can contradict with data, that are crowding out the harms we can demonstrate, and the things we can test, that could make social media better.” He added, “We’re years into this, and we’re still having an uninformed conversation about social media. It’s totally wild.”

New Yorker Favorites

A Harvard undergrad took her roommate’s life, then her own. She left behind her diary.

Ricky Jay’s magical secrets .

A thirty-one-year-old who still goes on spring break .

How the greatest American actor lost his way .

What should happen when patients reject their diagnosis ?

The reason an Addams Family painting wound up hidden in a university library .

Fiction by Kristen Roupenian: “Cat Person”

Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Adam Iscoe

By Helen Rosner

By Gary Shteyngart

By Eric Lach

How bad is social media, actually?

The scientific community is still divided on the effects of social media on your mental health, kohava mendelsohn • february 21, 2024.

Social media may just be a scapegoat for our other worries, say some psychologists [Photo Credit: mikito.raw | Pexels ]

The real story behind the ‘tiktok tics’, delaney dryfoos • april 13, 2022, does playing violent video games really lead to violent behavior, jeremy hsu • november 20, 2006, instagram could be the new clipboard survey for nyc parks, marion renault • november 15, 2018, when wildlife goes viral, olivia gieger • february 19, 2024, what happens when wild animals become social media sensations, alice sun • september 18, 2023.

On Oct 24, 2023, 41 states banded together to sue the international tech giant Meta for intentionally making social media addictive for children and causing them to have worse mental health. New York City has now joined them. And some would say these states have a point. Haven’t we known for years that social media is terrible for us?

Science paints a more complex story.

On a global scale, greater use of Facebook is not linked to any effect on well-being, says a study from Oxford University published August 2023. Andrew Przybylski and Matti Vuorre , psychologists at Oxford’s Internet Institute, analyzed well-being indicators among residents of 72 countries, alongside data that tracked how much people in those countries used Facebook.

Looking at data from almost one million people over the course of 12 years, they found no link between using Facebook and experiencing worse mental health. In fact, in a given year, if a country increased the proportion of its citizens using Facebook, “it was likely that the well-being levels in that country were also slightly elevated,” Vuorre says. This is completely contrary to the conventional wisdom that social media has a negative association with mental health.

These findings confirmed the results of many other studies over the years, including ones from Brock University and Oxford , that have either found positive links between social media and mental health, or none at all.

Studies that take a more granular look at the connection between social media use and mental health, however, do sometimes manage to find a negative correlation. As Vuorre puts it, “this field is full of extremely mixed results.”

One such study was conducted recently by Andrea Irmer and Florian Shmiedek at Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany. They conducted an experiment over two weeks, where a group of 200 children aged 10 to 14 reported on their social media use and mental health. On average, those who used social media more were more likely to think other people had better lives than they did — called upward comparisons — and to report more negative well-being. These correlations were also consistent in each child on a day-to-day basis. On a day where a child used social media more than average, they “had stronger upwards comparisons and felt worse than they generally do,” says Shmiedek. Other studies also show correlations between social media use and poorer mental health.

So given the mixed evidence on the effect of social media, why has all the focus been on the negative findings like the one from the small study in Germany? Christopher Ferguson , a psychology researcher for over 20 years, has a theory: a media-based moral panic. Ferguson says there is a pattern where an older group of people are uncomfortable with new technologies that they haven’t grown up with. They get scared, and blame current societal issues on a new thing they don’t understand.

For other examples, Ferguson says, just look back through history. “Twenty years ago, we kind of had a similar thing over particularly violent video games ,” he says. There was a time when everyone was worried about television, and before that, comic books. “And for a while, everybody agrees that [the] thing is bad. And then after about 20 years, everybody thinks that [the] thing is okay again,” says Ferguson.

Because of this push from some older generations, the media tends to only cover the studies that support the panic, which can lead to a cycle where no one is aware that other studies even exist, says Ferguson. The older people have more money, more power and vote more, so they are listened to.

That’s what he thinks is going on with the current lawsuit against Meta. “Politicians have to make us [older people] happy,” Ferguson says.

Another important thing to note, in any scientific study, is that just because two things (like social media use and poor mental health) are correlated, that doesn’t mean that we can definitely know one caused the other, or even which one caused which. “You could take Beyoncé’s salary year to year, and correlate that against the temperature of the Earth, you know, and you will find a probably pretty strong correlation,” Ferguson says, “but we wouldn’t say Beyoncé is literally making the world hotter … maybe figuratively, but not literally.” Scientists and lawmakers should always use caution when exploring why two variables are linked.

It might take years for this lawsuit to play out, but Ferguson says he wouldn’t be surprised if social media issues eventually make their way to the Supreme Court. He doesn’t know exactly how it would go, but a video game violence lawsuit titled Brown v. Entertainment Merchants made it to the Supreme Court in 2011. The court failed to find a link between violent video games and harm to children, and ruled that the sale of violent video games was legal. Ferguson will be watching to see if history repeats itself — or not.

About the Author

Kohava Mendelsohn

Kohava is a science and technology writer from Toronto, Canada. She has an undergraduate degree in Robotics Engineering from the University of Toronto. She loves explaining math, science, and technology concepts to all ages and experiences level, and believes anyone can learn anything if it’s taught well.

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

The Scienceline Newsletter

Sign up for regular updates.

Social Media Can Damage Mental Health

Here’s how we can change that..

Posted September 9, 2021 | Reviewed by Tyler Woods

- There is a connection between poor mental health and social media usage.

- We need to lessen the impact social media use is having on our health, particularly that of our teens.

- Many people know that social media use is correlated to increased anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem, yet few want to make any changes.

With alarming frequency, the research reports hit my inbox, my newspaper, and—yes—my Twitter feed.

“ Excess screen time impacting teen mental health ”

“ Teens around the world are lonelier than a decade ago. The reason may be smartphones. ”

“ This Is Our Chance to Pull Teenagers Out of the Smartphone Trap ”

And that’s just from the last few weeks.

As a parent and as a professional who works in the field of education , the connection between poor mental health and smartphone usage—and more specifically, social media apps—is downright scary. That more doctors, schools, governments, and community groups aren’t speaking out is disheartening.

A recent piece from Helen Lee Bouygues recommends we declare social media a public mental health crisis and wage a campaign against it, much like we did with tobacco. I often work with Bouygues’s Reboot Foundation and wondered: What would that look like? What would it be like to have a public campaign?

For starters, it would include PSAs, educational outreach, both short-term and long-term research, and age restrictions on who can use social media platforms, according to Bouygues.

While I’m not sure that would work in my house, or with the teens I know—they’re too practiced to be dissuaded by a warning label, and too tech savvy to be defeated by an age restriction—I do think Bouygues is generally right. We need to mitigate the impact social media is having on our children’s mental health.

What we must do is give technology users, and teenagers especially, the critical thinking skills necessary to interpret what they see online, so that they can contextualize it and ultimately assess whether the latest meme or trending topic is worth their time or consideration.

This past spring the Reboot Foundation surveyed more than 1,000 Americans on their social media usage and its impact on their mental health, and the results were alarming. More than half of the people who took part in the survey acknowledged that their social media use intensified their feelings of anxiety , depression , or loneliness . They also knew that it contributed to feelings of low self-esteem and made it harder for them to concentrate.

So what did users do about this? Basically, nothing. Only about a third said that they took steps to limit their social media use. That same survey revealed that 40 percent of the respondents said they would give up their cars, TV, and their pets before they would give up their social media accounts.

See what we're up against?

Critical thinking begins with reflective thinking. This requires us to step back and examine our own thinking process, and to notice when we are thinking irrationally or unproductively. This type of thinking is also called “ metacognition .”

Social media apps and platforms were designed to discourage reflective thinking. The algorithms that control our feeds have been perfected to supply their users high octane emotional content that’s easy to share and amplify, regardless if it’s good for society, or for your mental health.

Teaching young people to be reflective thinkers would give them tools to resist conclusions based on raw emotion or knee-jerk reactions. This would go a long way to helping slow the spread of harmful content online.

Another way improved critical thinking skills would help address the mental health crisis teens face online is by giving them the confidence to think independently and to resist group pressure. This cool, rational thought is often called objective thinking and allows users to free themselves of the “hivemind” and to recognize that just because something is trending on Twitter doesn’t mean it’s worthy of your attention .

In short, good critical thinkers reflect on and correct their thinking. They’re objective and rational, even when things get heated or the facts get muddy.

Heated arguments and muddy facts. Doesn’t that sound like social media these days?

The good news is that these critical thinking skills can be taught and there is overwhelming public support for doing so . The bad news is that most schools don’t teach these skills very well.

That needs to change. Our’s kids’ mental health depends on it.

Ulrich Boser is the founder of The Learning Agency and a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. He is the author of Learn Better, which Amazon called “the best science book of the year.”

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Why Can Social Media Have Such a Negative Effect On Us?

Social media, for better and worse, is a part of most of our lives, trainee psychotherapist emma kilburn explores two psychological theories that explain why social media is addictive .

We all know that too much time spent on social media can have a negative impact on our wellbeing. Too much time spent scrolling through feeds and stories can have a numbing effect and can sometimes unhelpfully distract us from people, situations and thoughts that require our attention. Social media also notoriously feeds our FOMO , and research has also shown that the comparisons it encourages us to make with the shiny, edited highlights of other people’s lives also has a negative psychological effect, whether or not we feel we are better off than the friends or celebrities with whose posts we are making comparisons. Psychological theories can develop our understanding of the deleterious effects of social media further, and help us make informed decisions about how and how much we engage with it.

One reason social media is so addictive is because of the way in which it fulfils our ego needs. According to Freud, our minds are made up of three components: the id, the super-ego and the ego. The id is the instinctual part of the mind that contains sexual and aggressive drives, and hidden memories. Our super-ego is our moral conscience, and the ego is the most realistic part of the mind, which mediates between the id and the super-ego, between the internal world and the external world. The ego aims to make the desires of the id socially acceptable.

For Freud, those desires were primarily related to libido, or sexual energy. The ego would convert the id’s raw desire into something more socially acceptable, such as making oneself attractive to others. Today, our understanding of the id’s instinctual desires has expanded to include a more general desire to relate to others. Social networks are a useful tool that enable us to do this. As has been frequently discussed, they also enable us to present an idealised image of ourselves as we would like to seem and to be seen. Both practically and psychically, this can lead to an over insistence on the outward presentation of the ego, at the expense of more inward expressions of our identities and the elements of ourselves – perhaps those parts that we consider vulnerable or shameful – that we do not want to share with other people. This can create a psychological imbalance and reinforce our negative perception of those aspects of our identity that we feel the need to conceal.

Alongside this, our super-ego can bring its harsh judgement to bear on the face we are presenting to the outside world, if it feels we are not succeeding. Our super-ego encourages us to compare ourselves negatively to other people and in this respect is perfectly aligned with the way in which social media pushes us to be aspirational and to make comparisons with profiles, feeds and stories we see online. Again, this can be to the detriment of a healthy ego and a more complete sense of self.

The false self

The ways in which social media encourages us to present online, and the manner in which this can feed the less healthy aspects of our ego and super-ego can lead us to establish a false self. It was psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott who first defined the notion of the false self. As children develop, they begin to realise which feelings are OK and which are not OK (feelings like anger, rage, anxiety and unhappiness). If the behaviour of adults around them teaches them to hide that second group of feelings away, they can then develop a false self, the acceptable face that they present to the outside world, which hides and protects their true self.

The false self behaves and interacts in a way that is expected and accepted, while the true self is concealed, still feeling all the things that have been deemed to be unacceptable. To a certain extent, the false self is an adaptation to our need to mediate our interactions with the outside world, with society. But it can be maladaptive in the sense that our interaction is partial, leaving vast parts of ourselves unrecognised. This can lead to a sense of alienation, to feelings of shame and even to depression . Social media can feed and support this maladaptive relationship with our sense of self, since it requires us to be wearing a social and socially acceptable mask.

Our awareness that multiple audiences see our posts and stories can create a tension between our daily lives and what of them we choose to share – have you ever gone to post a picture of a night out and hesitated, aware that your gran and your work colleagues will see it, as well as your closest friends? Navigating multiple relationships and aspects of self via a single online identity can be difficult, and can limit our self-expression. Our tendency to present an idealised version of our lives online can also lead to a sense of disconnection. And however much control we have over what we choose to post, we then have very little control over how others respond to and use that information, which can lead us to feel we have lost our sense of ownership of what is most personal to us: our identity.

Internal objects

The final theory it can be helpful to draw upon when seeking to explain why social media can have such an adverse effect is Melanie Klein’s Theory of Internal Objects. Melanie Klein was a psychotherapist who was the main figure in the development of object relations theory.

Object relations refers to dynamic, internalised relationships between the self and significant others, or ‘objects’. There are three main components to an object relation: the object as it is perceived by the self, the self in relation to the object and the relationship between self and object. The object as it is perceived by the self is an ‘internal object’, an emotional and mental image of another person that has been internalised.

We initially form these internal objects in infancy, through our experiences with our caregivers – particularly mothers. In healthy development, these mental representations evolve over time, and change depending on our experiences in relationships with others. In less healthy development they can remain at a more immature level, and there is a tendency to see relationships and people in black and white terms, as either good or bad. This can occur particularly if a mother is not able to meet a child’s emotional needs. Where a mother is emotionally available, a child will come to merge the negative and positive aspects of that mother into an integrated and more realistic whole. Since the child has internalised the relationship and her representation of the mother, this integration extends to the child’s own sense of identity. Conversely, if the mother is at times emotionally absent, the child is likely to repress bad aspects of the mother’s identity and of the self. This repression is not sustainable – i.e. these negative aspects will re-emerge and cause difficulties in terms of self-esteem and relationships with others. These damaged internal objects can also lead to anxiety and undermine our sense of wellbeing.

These difficult feelings can be linked to and be exacerbated by our use of social media. Melanie Klein identified ways in which infants protect themselves against negative feelings, and the processes she describes can also apply to adults who are struggling with anxiety or low self-esteem . In Klein’s model, we project hate and ‘badness’ onto other people, to get rid of our own negative feelings. This process of projection is closely aligned with the ways in which we might use social media to help us feel good about ourselves, by getting drawn into comparisons with other people’s feeds and stories. This can be harmful in two ways.

Firstly, as mentioned, research has shown that comparisons can have an adverse effect, even if we emerge on the positive side of the comparison. Secondly, we are just as likely to compare ourselves negatively to other people. Then, rather than projecting the bad, we introject it, and use others’ social media feeds to reinforce our negative feelings about ourselves. While Melanie Klein saw healthy projection and introjection as a way to cope with anxiety and to form links with others, she also recognised that if they are used excessively, they can sabotage our sense of a secure, coherent self, and a reliable other. Social media can encourage us to do just that.

Klein also made a clear link between a lack of the strong sense of self and envy – an emotion that can be fuelled by social media. What makes envy so destructive is that it is an urge to destroy not badness but goodness. Envy makes it impossible to benefit from goodness, leading us to discard or destroy positive possibilities in terms of relationships. According to Klein, an insecure sense of self also leads us to fragment our identity, and those of others. The limited and edited versions of an individual’s identity presented by social media accounts support this sense of fragmentation, which leads us further away from more positive and rounded relationships with ourselves and others.

As ever, the fact remains that social media can play a vital role in connecting people and in creating opportunities for self-expression. However, an awareness of some of the ways that it can exacerbate psychological tendencies we may already have, or undermine our sense of self, can help us take a more measured and considered approach social networks. If time online leaves us feeling low or empty, we can reflect on why this might be, and seek out other forms of social interactions that can support our psychological wellbeing.

Emma Kilburn is a trainee psychotherapist and writer

Further reading

The psychology of social media malice, how social and political forces shape our identity, is it time to quit social media, how childhood shame shapes adult identity, who am i and why does it matter a therapist's view on identity, find welldoing therapists near you, related articles, recent posts.

Book of the Month: No One Talks About This Stuff by Kat Brown

Dear Therapist..."My Sexual Self is Dead"

Meet the Therapist: George Roberts

The Anxious-Avoidant Dance: What Happens When Insecure Attachment Styles Combine?

The Many Symptoms of Stress, And What To Do About Them

Why Bother Being Mindful?

Meet the Therapist: Jayne Morris

Dear Therapist..."I've Spoken Up About Past Abuse – My Family Hasn't Supported Me"

Is FOPO Holding You Back at Work and In Your Personal Life?

Are Mental Health Diagnoses Doing More Harm Than Good To Our Children?

Find counsellors and therapists in London

Find counsellors and therapists in your region, join over 23,000 others on our newsletter.

Too much social media can be harmful, but it’s not addictive like drugs

Professor of Addictions and Health Psychology, University of South Wales

Senior Lecturer in Psychology of Relationships, University of South Wales

Disclosure statement

Bev John has received funding from European Social Funds/Welsh Government, Alcohol Concern (now Alcohol Change), Research Councils and the personal research budgets of a number of Welsh Senedd members. She is an invited observer of the Cross-Party Group on Problem Gambling at the Welsh Parliament and sits on the “Beat the Odds” steering group that is run by Cais Ltd.