A global story

This piece is part of 19A: The Brookings Gender Equality Series . In this essay series, Brookings scholars, public officials, and other subject-area experts examine the current state of gender equality 100 years after the 19th Amendment was adopted to the U.S. Constitution and propose recommendations to cull the prevalence of gender-based discrimination in the United States and around the world.

The year 2020 will stand out in the history books. It will always be remembered as the year the COVID-19 pandemic gripped the globe and brought death, illness, isolation, and economic hardship. It will also be noted as the year when the death of George Floyd and the words “I can’t breathe” ignited in the United States and many other parts of the world a period of reckoning with racism, inequality, and the unresolved burdens of history.

The history books will also record that 2020 marked 100 years since the ratification of the 19th Amendment in America, intended to guarantee a vote for all women, not denied or abridged on the basis of sex.

This is an important milestone and the continuing movement for gender equality owes much to the history of suffrage and the brave women (and men) who fought for a fairer world. Yet just celebrating what was achieved is not enough when we have so much more to do. Instead, this anniversary should be a galvanizing moment when we better inform ourselves about the past and emerge more determined to achieve a future of gender equality.

Australia’s role in the suffrage movement

In looking back, one thing that should strike us is how international the movement for suffrage was though the era was so much less globalized than our own.

For example, how many Americans know that 25 years before the passing of the 19th Amendment in America, my home of South Australia was one of the first polities in the world to give men and women the same rights to participate in their democracies? South Australia led Australia and became a global leader in legislating universal suffrage and candidate eligibility over 125 years ago.

This extraordinary achievement was not an easy one. There were three unsuccessful attempts to gain equal voting rights for women in South Australia, in the face of relentless opposition. But South Australia’s suffragists—including the Women’s Suffrage League and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, as well as remarkable women like Catherine Helen Spence, Mary Lee, and Elizabeth Webb Nicholls—did not get dispirited but instead continued to campaign, persuade, and cajole. They gathered a petition of 11,600 signatures, stuck it together page by page so that it measured around 400 feet in length, and presented it to Parliament.

The Constitutional Amendment (Adult Suffrage) Bill was finally introduced on July 4, 1894, leading to heated debate both within the houses of Parliament, and outside in society and the media. Demonstrating that some things in Parliament never change, campaigner Mary Lee observed as the bill proceeded to committee stage “that those who had the least to say took the longest time to say it.” 1

The Bill finally passed on December 18, 1894, by 31 votes to 14 in front of a large crowd of women.

In 1897, Catherine Helen Spence became the first woman to stand as a political candidate in South Australia.

South Australia’s victory led the way for the rest of the colonies, in the process of coming together to create a federated Australia, to fight for voting rights for women across the entire nation. Women’s suffrage was in effect made a precondition to federation in 1901, with South Australia insisting on retaining the progress that had already been made. 2 South Australian Muriel Matters, and Vida Goldstein—a woman from the Australian state of Victoria—are just two of the many who fought to ensure that when Australia became a nation, the right of women to vote and stand for Parliament was included.

Australia’s remarkable progressiveness was either envied, or feared, by the rest of the world. Sociologists and journalists traveled to Australia to see if the worst fears of the critics of suffrage would be realised.

In 1902, Vida Goldstein was invited to meet President Theodore Roosevelt—the first Australian to ever meet a U.S. president in the White House. With more political rights than any American woman, Goldstein was a fascinating visitor. In fact, President Roosevelt told Goldstein: “I’ve got my eye on you down in Australia.” 3

Goldstein embarked on many other journeys around the world in the name of suffrage, and ran five times for Parliament, emphasising “the necessity of women putting women into Parliament to secure the reforms they required.” 4

Muriel Matters went on to join the suffrage movement in the United Kingdom. In 1908 she became the first woman to speak in the British House of Commons in London—not by invitation, but by chaining herself to the grille that obscured women’s views of proceedings in the Houses of Parliament. After effectively cutting her off the grille, she was dragged out of the gallery by force, still shouting and advocating for votes for women. The U.K. finally adopted women’s suffrage in 1928.

These Australian women, and the many more who tirelessly fought for women’s rights, are still extraordinary by today’s standards, but were all the more remarkable for leading the rest of the world.

A shared history of exclusion

Of course, no history of women’s suffrage is complete without acknowledging those who were excluded. These early movements for gender equality were overwhelmingly the remit of privileged white women. Racially discriminatory exclusivity during the early days of suffrage is a legacy Australia shares with the United States.

South Australian Aboriginal women were given the right to vote under the colonial laws of 1894, but they were often not informed of this right or supported to enroll—and sometimes were actively discouraged from participating.

They were later further discriminated against by direct legal bar by the 1902 Commonwealth Franchise Act, whereby Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were excluded from voting in federal elections—a right not given until 1962.

Any celebration of women’s suffrage must acknowledge such past injustices front and center. Australia is not alone in the world in grappling with a history of discrimination and exclusion.

The best historical celebrations do not present a triumphalist version of the past or convey a sense that the fight for equality is finished. By reflecting on our full history, these celebrations allow us to come together, find new energy, and be inspired to take the cause forward in a more inclusive way.

The way forward

In the century or more since winning women’s franchise around the world, we have made great strides toward gender equality for women in parliamentary politics. Targets and quotas are working. In Australia, we already have evidence that affirmative action targets change the diversity of governments. Since the Australian Labor Party (ALP) passed its first affirmative action resolution in 1994, the party has seen the number of women in its national parliamentary team skyrocket from around 14% to 50% in recent years.

Instead of trying to “fix” women—whether by training or otherwise—the ALP worked on fixing the structures that prevent women getting preselected, elected, and having fair opportunities to be leaders.

There is also clear evidence of the benefits of having more women in leadership roles. A recent report from Westminster Foundation for Democracy and the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership (GIWL) at King’s College London, shows that where women are able to exercise political leadership, it benefits not just women and girls, but the whole of society.

But even though we know how to get more women into parliament and the positive difference they make, progress toward equality is far too slow. The World Economic Forum tells us that if we keep progressing as we are, the global political empowerment gender gap—measuring the presence of women across Parliament, ministries, and heads of states across the world— will only close in another 95 years . This is simply too long to wait and, unfortunately, not all barriers are diminishing. The level of abuse and threatening language leveled at high-profile women in the public domain and on social media is a more recent but now ubiquitous problem, which is both alarming and unacceptable.

Across the world, we must dismantle the continuing legal and social barriers that prevent women fully participating in economic, political, and community life.

Education continues to be one such barrier in many nations. Nearly two-thirds of the world’s illiterate adults are women. With COVID-19-related school closures happening in developing countries, there is a real risk that progress on girls’ education is lost. When Ebola hit, the evidence shows that the most marginalized girls never made it back to school and rates of child marriage, teen pregnancy. and child labor soared. The Global Partnership for Education, which I chair, is currently hard at work trying to ensure that this history does not repeat.

Ensuring educational equality is a necessary but not sufficient condition for gender equality. In order to change the landscape to remove the barriers that prevent women coming through for leadership—and having their leadership fairly evaluated rather than through the prism of gender—we need a radical shift in structures and away from stereotypes. Good intentions will not be enough to achieve the profound wave of change required. We need hard-headed empirical research about what works. In my life and writings post-politics and through my work at the GIWL, sharing and generating this evidence is front and center of the work I do now.

GIWL work, undertaken in partnership with IPSOS Mori, demonstrates that the public knows more needs to be done. For example, this global polling shows the community thinks it is harder for women to get ahead. Specifically, they say men are less likely than women to need intelligence and hard work to get ahead in their careers.

Other research demonstrates that the myth of the “ideal worker,” one who works excessive hours, is damaging for women’s careers. We also know from research that even in families where each adult works full time, domestic and caring labor is disproportionately done by women. 5

In order to change the landscape to remove the barriers that prevent women coming through for leadership—and having their leadership fairly evaluated rather than through the prism of gender—we need a radical shift in structures and away from stereotypes.

Other more subtle barriers, like unconscious bias and cultural stereotypes, continue to hold women back. We need to start implementing policies that prevent people from being marginalized and stop interpreting overconfidence or charisma as indicative of leadership potential. The evidence shows that it is possible for organizations to adjust their definitions and methods of identifying merit so they can spot, measure, understand, and support different leadership styles.

Taking the lessons learned from our shared history and the lives of the extraordinary women across the world, we know evidence needs to be combined with activism to truly move forward toward a fairer world. We are in a battle for both hearts and minds.

Why this year matters

We are also at an inflection point. Will 2020 will be remembered as the year that a global recession disproportionately destroyed women’s jobs, while women who form the majority of the workforce in health care and social services were at risk of contracting the coronavirus? Will it be remembered as a time of escalating domestic violence and corporations cutting back on their investments in diversity programs?

Or is there a more positive vision of the future that we can seize through concerted advocacy and action? A future where societies re-evaluate which work truly matters and determine to better reward carers. A time when men and women forced into lockdowns re-negotiated how they approach the division of domestic labor. Will the pandemic be viewed as the crisis that, through forcing new ways of virtual working, ultimately led to more balance between employment and family life, and career advancement based on merit and outcomes, not presentism and the old boys’ network?

This history is not yet written. We still have an opportunity to make it happen. Surely the women who led the way 100 years ago can inspire us to seize this moment and create that better, more gender equal future.

- December 7,1894: Welcome home meeting for Catherine Helen Spence at the Café de Paris. [ Register , Dec, 19, 1894 ]

- Clare Wright, You Daughters of Freedom: The Australians Who Won the Vote and Inspired the World , (Text Publishing, 2018).

- Janette M. Bomford, That Dangerous and Persuasive Woman, (Melbourne University Press, 1993)

- Cordelia Fine, Delusions of Gender: The Real Science Behind Sex Differences, (Icon Books, 2010)

This piece is part of 19A: The Brookings Gender Equality Series. Learn more about the series and read published work »

About the Author

Julia gillard, distinguished fellow – global economy and development, center for universal education.

Gillard is a distinguished fellow with the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. She is the Inaugural Chair of the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership at King’s College London. Gillard also serves as Chair of the Global Partnership for Education, which is dedicated to expanding access to quality education worldwide and is patron of CAMFED, the Campaign for Female Education.

Read full bio

MORE FROM JULIA GILLARD

Advancing women’s leadership around the world

More from the 19a series.

The gender revolution is stalling—What would reinvigorate it?

What’s necessary to reinvigorate the gender revolution and create progress in the areas where the movement toward equality has slowed or stalled—employment, desegregation of fields of study and jobs, and the gender pay gap?

The fate of women’s rights in Afghanistan

John R. Allen and Vanda Felbab-Brown write that as peace negotiations between the Afghan government and the Taliban commence, uncertainty hangs over the fate of Afghan women and their rights.

- Media Relations

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- For Instructors

- About SocImages

- Submitting Guest Posts

Examples of the Marginalization of Women and Girls

Enjoy a new round-up of examples in which men = people and women = women. The tendency to include women as a special type of human being, alongside men who get to be regular people, is a specific example of a more general phenomenon in which some people, but not others, are marked as a specific kind. We see this with race, routinely, in cases where there are “people” and “black people,” “families” and “ethnic families,” or when the skin tone of white people is substituted for the very idea of “skin” tone . And we’ve covered many examples of this in regards to gender; see our posts on the Body Worlds exhibits , avatars , fitness equipment , rulers , and this collection of many additional examples . Here is a new set of instances submitted by our Readers:

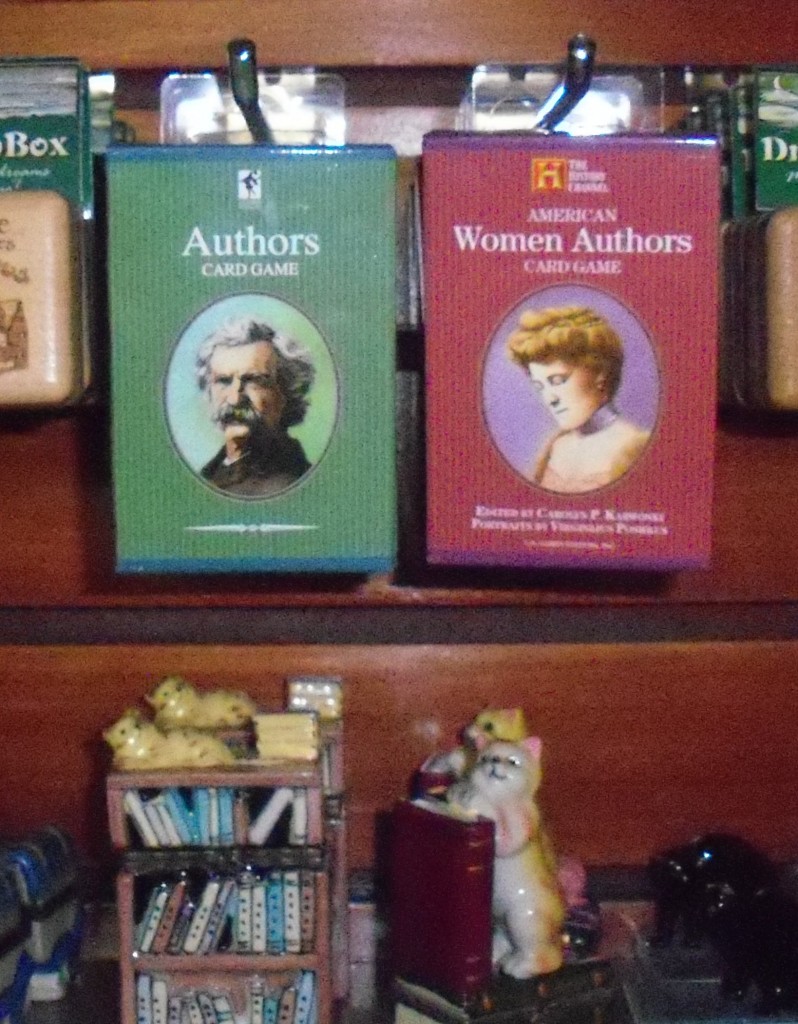

Michelle P. took this photo of two card games in Salem, MA at The House of the Seven Gables gift shop:

froodian sent along a set of guitar straps for sale. There are “guitar straps,” “giggin for god guitar straps,” “kids guitar straps,” and “girls’ guitar straps” in pink, purple, and baby blue:

Sarah J. noted that the website www.healthcare.gov features sections (along the bottom) for “healthy individuals,” “individuals with health conditions,” and “women”:

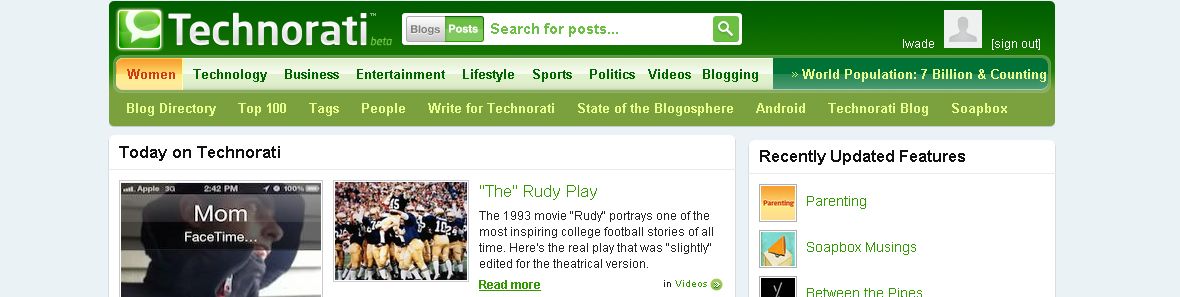

Finally, Leigh sent along Technorati’s odd effort to appeal to women. Their main site has a highlighted yellow tab to press if you’re female, labeled “women.” And, if you do, you get girly content, plus pretty flowers!

The main site:

The woman site:

Comments 72

Kaileyverse — april 24, 2011.

This is why we still need feminism.

Mazarine — April 24, 2011

I noticed that on the Technorati site yesterday, and I was frankly appalled.

They obviously think that women are all

2. Interested in breast cancer.

it's really sick, the way technorati is all, "let's throw them a bone" and make a website they think will appeal to "women" in general.

Why wouldn't women be interested in sports? In writing? In Music? In art? In just about anything that men would be interested in?

Way to go Technorati. Your flaccid site is very toilet.

Anonymous — April 24, 2011

To be fair, the Health Care example isn't quite the same.

Women face very different challenges in health care in the US, especially in regards to pregnancy.

Under the 'women' section on that site it addresses concerns such as women being denied coverage due to previous pregnancies and paying higher health care costs because of pregnancies. Men have no comparable issues.

http://www.healthcare.gov/foryou/women/index.html

There's a difference between women being considered as lesser or as something less notable than men, and separating men and women based on biological facts and issues that are exclusive to one gender. The healthcare.gov site does bring up very real issues of discrimination against women, but it does so in an effort to combat it and protect women from further discrimination.

J — April 24, 2011

Why there are so many magazines for females than for males? They are probably doing that for "commercial reasons" rather than "social discrimination." They did it because "girls" want it.

James — April 24, 2011

What I think, is that the "women" section was created by thinking of giving women a fair representation in the site. I don't see men as interested in the health issues particular to our sex (prostate cancer, what else?) as much as women do (pregnancy, breast cancer, vaginal infections).

So these people were thinking of giving fair treatment to women, not of differentiating them from "normal people" through some obscure deconstructivist sexist spell.

Sunny — April 24, 2011

Also, science pretty much ignored research on women for a long time, and now that we know the particulars of how diseases effect women specifically, it seems a good idea to highlight it. For example, when looking for the symptoms of a heart attack, you will find that many sites give generalized symptoms (left arm pain, chest tightness, etc.) which are the symptoms common to men, but could happen in women. Now we know that women can experience heart attacks very differently from men, and very often do. Is it really that bad to have a special place to put that information, since we didn't even have it for such a long time?

PJ — April 24, 2011

And don't you wonder why something like a guitar strap has to be labeled as a "girl's" guitar strap because it's pink? I am fairly certain that there are some boys out there who would LOVE a pink guitar strap!

thewhatifgirl — April 24, 2011

In regards to the health section, the idea that women have unique health needs and therefore need a different health section doesn't even hold up. Women are half of the entire human race; our needs are not unique, they are universal for one half of the human race. The idea that a uterus and ovaries must force a person to be considered divisible and separate from "normal people", and that "normal people" are assumed to be male, is the issue here, not the idea that different body parts require different types of health care.

Luna — April 24, 2011

Obviously there's a lot to be said about the issues and problems here, but I wanna point out that I own the "authors" deck, and there are two women in it.

Karyn — April 24, 2011

Anyone else find it weird that the image for "Healthy Individuals" is a white man, while the image for "Individuals with Health Conditions" is a black man? Perhaps not purposeful, but I think it sends a message nonetheless.

Why is it that I get really nervous talking to pretty girls and is that lack of confidence? | game for girls — April 25, 2011

[...] Examples of the Marginalization of Women and Girls » Sociological … [...]

Ekate — April 26, 2011

BTW,Can't men use pink regardless of their sexual orientation? A little bit tired of so many stereotypes! Growing a girl/woman was tough for me but I don't think "becoming a man" is easy either...what if we try to get rid of stupid colour schemes together (where possible)?

Mancao Joyce — August 11, 2011

shaggggggggggggggggggggggggg

cutieeeeeeeee — August 11, 2011

its better that you can give some examples about marginalization........so that the readers should understand more about it.

Bellandr — October 21, 2011

So what's wrong with a guitar strap that says "Giggin for God"?

The default human — March 13, 2012

[...] (or comediennes), as if being female means that you need a rider to describe you. There are authors and “women authors” because authors are male by default. And of course, in the same vein as that last link there are [...]

kay — January 8, 2014

The game called "Authors" has male and female authors in it. http://www.amazon.com/gp/aw/d/1572814454/ref=mw_dp_mdsc?dsc=1

Marginalization and Gender – Rethinking "Reality" — February 22, 2015

[…] Lisa Wade professor of sociology, best describes marginalization as “the tendency to include women as […]

Dudecommon — January 25, 2017

Realize how all the comments are from women

Lesson 23: Conflict, Cohesion and Inequality | HSP3C with Ms. Maharaj — April 21, 2017

[…] https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2011/04/24/35201/comment-page-1/ […]

Calafia — January 29, 2019

Psssst...it's this really strange thing called "market-ing". Target marketing, niche marketing, whatever you want to call it. I think that really IS it. I'm a woman of color, and we are the new feminists. So look out world, it's about to get real interesting ;-).

Jane — February 2, 2019

I'm a mature woman; mother, grandmother, widow, divorcee. I definitely have different issues in my life than a man does. And while we might share some common interests, we are each unique. Physically, emotionally mentally. Maybe all this anger and resentment could be solved by simply adding the label "men" to a column/tab and including generalized sports and political topics in the women's sections. Why are some women so threatened or angry being called a woman or being given something specifically for women? Don't you know how special you are? Women have run the world since the beginning of time. Wasn't it Eve who talked Adam into eating the apple? We are not victims, ladies. We are survivors.....no matter what size, shape, color or sexual orientation. Stop complaining about being treated differently as a woman. There's nothing wrong with being special. And you are.

rhods jog — March 18, 2019

NBA 2K19 APK OBB on PC

Catie — June 2, 2019

The most marginalized in our society are incarcerated women. I work with them and they are treated as “less than” in every possible way. Marginalization is more serious than last pink guitar straps.

Aleop8 — March 29, 2022

Games for you to play. Yukon Gold offers 150 chances to win $1 Million!

abel — May 18, 2023

Discriminatory practices and societal norms can restrict women's economic Mini Crossword participation and limit their financial independence.

Harry Smith — September 25, 2023

Powerful examples shedding light on the marginalization of women and girls. When it's time to share your own insights, consider collaborating with a professional ghostwriting company .

Jenni Morgan — December 14, 2023

Delve into a critical exploration of societal issues with Examples of the Marginalization of Women and Girls. Much like the commitment of the best book publishing company to spotlight diverse narratives, this compilation sheds light on the various ways women and girls face marginalization. Through poignant examples and insightful analysis, the title serves as a catalyst for fostering awareness and understanding. Explore the impactful narratives within, akin to the commitment of the best book publishing company to amplify stories that resonate with readers across the spectrum.

George Mark — December 18, 2023

Fantastic blog i have never ever read this type of amazing information. La Knight Vest

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

About Sociological Images

Sociological Images encourages people to exercise and develop their sociological imaginations with discussions of compelling visuals that span the breadth of sociological inquiry. Read more…

Posts by Topic

Subscribe by email.

CC Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 17 May 2016

“Marginalization” in third world feminism: its problematics and theoretical reconfiguration

- Asma Mansoor 1

Palgrave Communications volume 2 , Article number: 16026 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

32k Accesses

1 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

A Corrigendum to this article was published on 07 June 2016

With the imposition of certain notions of agency and marginalization prescribed by first world feminist discourses, global feminism has cumulatively remained mired within a binaristic closure. This closure is based on the idea of an agentive Western feminist center and a passive third world feminism at the margin. This article endeavours to go beyond this closure to initiate debates regarding the operational praxis of a third world woman’s marginal placement as articulated in third world feminist discourses. It problematizes the idea of “disempowerment” that stems from a patriarchal model depicting man as the nucleus and a woman as a peripheral and centripetal entity, drawn within the mise en abyme of self-consolidating representations. Therefore, the argument presented here revisits the notion of the marginalization of third world women by subjecting the theoretical approaches regarding female marginalization and agency—as articulated by Spivak, Irigaray and Kristeva, et al. —to a deconstructive mode of analysis to explore the theoretical reconfiguration of a third world woman’s marginal placement. This article reconsiders the margin as discursively “limitrophic” so that the binaries between the margin/center, agency/disempowerment and third world feminism/first world feminism are re-scrutinized. The margin, thus, becomes an agentive plane for a third world woman as she uses it to direct her gaze away from any discursive center. In this way, a third world woman undermines the West-centric centripetal force despite being englobed within what Kristeva calls “supranational sociocultural ensembles” and sees her “self” as independent of any fixed center so that she redefines herself as an autonomous thinking woman able to dismantle the notion of a congealed subalternity. This article is published as part of a thematic collection on gender studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

The East-West dialogue: methodical diversity and frailties of feminist accounts

Linghui Nancy Zhou

Back to Marx: reflections on the feminist crisis at the crossroads of neoliberalism and neoconservatism

Jinlong Lin & Yang Wang

An intimate dialog between race and gender at Women’s Suffrage Centennial

Introduction.

As a resident third world woman, for me the existing mantra of the disempowerment and passivity of third world women has been particularly difficult to accept in its entirety. One of the problematic aspects of third world feminist discourses in general is that they rely heavily on West-centric, patriarchal terms such as empowerment, agency, selfhood and so on. These terms have percolated into third world feminist discourses without undergoing much of a discursive diffraction that would necessarily stem from their transplantation into a different cultural context. One of the reasons why these terms were not discursively reconfigured during this contextual migration may be that they were mired within the boundaries uncritically prescribed by the rigid, colonial bifurcation between the East and the West. In this theoretical thought experiment, my argument revises the notion of ‘marginalization” as propounded by Western feminisms and absorbed within third world feminist discourses. Instead of viewing the margin as a space of disempowered passivity, I, as a third world woman, view the margin as a discursively permeable space for the agentive reconfiguration of the binaries contouring contemporary feminist discourses.

My argument proposes that the margin needs to be seen as a “limitrophic” ( Derrida, 2002 : 397) domain generating an interplay of “différance” between third and first world feminist discourses. Therefore, the Derridean terms, “limitrophy” ( Derrida, 2002 : 397) and “différance” ( Derrida, 1967 : 23) channelize this thought experiment. The reason why the margin is to be seen as limitrophic is that not only does this concept present boundaries as permeable zones, it also displays an active variation within its space. It is necessary to clarify at the very outset that this limitrophic processuality is able to extract the supposedly third world women out of any monolithic, ontological fixity imposed upon them by first world feminist discourses. Moreover, since the limitrophic margin is seen as permutative, the entities anchored within it are also malleable both within their constitution and “situatedness” ( Spivak, 2010 ). This implies that third world feminism is constitutively heterogeneous. However, at the opening of this discussion, it is essential for me to begin by presenting third world feminism as a monolithic notion only to subsequently disband this essentialism. With a deconstructive mode of reading outlining this thought experiment, this mode of essentialist categorization is “inaccurate yet necessary” ( Spivak, 1976 : xii) to dismantle the a priori , monolithic construction of third world women.

In addition, with the dynamics of the masculine and feminine gaze establishing the infrastructure of my argument, I have utilized ray diagrams of reflection in conjunction with figures illustrating circular motion to provide an analogical subtext to this thought experiment. They elucidate the ideas of the re-configuration of the margin in terms of the interplay of différance as propounded by Derrida in Of Grammatology . In this article, this interplay of différance takes place between first and third world feminisms. This interplay is consolidated by the idea of a limitrophic margin at which a third world woman is supposedly positioned. Here, différance implies a state of constant erasure and modification so that no construct is “ thought at one go ” ( Derrida, 1967 : 23; author’s italics) in all its entirety. Thus, the idea of a third world woman is in a state of constant deferral as an “erased determinator”, which reconfigures both itself, in all its “radical heterogeneity” ( MacCabe, 1987 : xvii), and also its relationship with the first world feminist center. In this way, it is constantly creating alternative modes of self-constitution that constantly postpone any ontological fixity thereby defying any “theoretical closure” ( Said, 1983 : 242). In addition, the ideas of “différance” and “limitrophy” provide tools for questioning Western epistemic paradigms influencing the construction of third world feminism. The incorporation of these ideas is strengthened by the fact that Western feminist discourses need to be countered through their own terminology, so that the tenuousness of their centrality may be effectively conveyed. While Deconstruction itself is a Western theory, however, it may be argued that it is able to exceed “the limits of Western representionalist discourse” even while altering the “images of marginality” ( Bhabha, 1994 : 68–69). Therefore, my argument is anchored in the deconstructive thought process since it aims at avoiding any re-centering of either first or third world feminist discourses.

The opthalmic relationship between first and third world feminisms

Since most first world feminist discourses place themselves at the powerful discursive center, ocularly outlining the third world woman, the third world feminist discourses either defend or contest their peripheral position ( Mohanty, 1988 ; Eisenstein, 2004 ; Spivak, 2010 ) without questioning the dynamics of the optics that govern these discourses. Here, I attempt to question the optics of these discourses along with the ontological fixity of the boundaries that situate first and third world feminisms within an ophthalmic interrelationship. This is because most global feminist discourses have upheld the boundary-based patriarchal dualisms that have contoured gender relations. These US/Other antagonisms have been perceived as ontological absolutes recognizable through a relational interaction with each other. Likewise, the global feminist discourses remain confined within the a priori notion of the central masculine gaze, defining the peripheral feminine entity in terms of its centripetal pull, which the feminine entity resists, and perhaps undermines, in a centrifugal manner. This sub-atomic image of an agentive nucleus binding and neutralizing an opposite marginal entity continues to outline the hierarchal male-female gender relations as well as the relationship between first and third world feminisms.

With this in mind, not only do I question the binaries of the margin/center, agency/ disempowerment and third world feminism/first world feminism, I also attempt to deconstructively revise the accepted associations that these terms carry. My argument is that not only do these West-centric terms carry over their associative ideological baggage into the third world feminist discourses, they are also absorbed by them as they are. In this way, third world feminisms are co-opted by first world feminist discourses adhering to their inherent assumptions. Resultantly, not only does the inherently binaristic, discursive speculum of the West continue to frame the arguments of first world feminists like Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray and so on, it also outlines the arguments of third world feminist theorists like Spivak who are situated in the first world academia. These theorists, at times, function like afferents, taking stimuli from the supposedly Eastern periphery to the Western nervous center for decoding and vice versa. While theorists like Mohanty, Judith Butler, Zillah Eisenstein and so on, endeavour to challenge this binarism, my effort is to focus on the operational paradigms of the periphery and the entity located within that periphery.

It is worth restating that third world feminist discourses cover a range of issues demanding a re-writing and re-reading of male texts such as those of Freud in a “race sensitive” ( Spivak, 1986 : 81) manner so that the production of a third world woman as a “colonial object” produced by the “hegemonic First World intellectual practices” ( Spivak, 1986 : 81–82) is brought back into focus. These intellectual practices stem from an assumed privileged position of “what can I do for them?” ( Spivak, 1981 : 155; author’s italics), assuming that most third world women need help. Mohanty, on the other hand, in line with Zillah Eisenstin, argues against such an imposition of an uncritical universality and “cross-cultural validation” ( Mohanty, 1988 : 199) on all categories of women since she postulates that feminism has to be classified on the basis of a “concrete historical and political praxis” ( Mohanty, 1988 : 201). However, since the Third World’s historical and political praxis is contextually diverse, here the limitrophic margin within which they are theoretically located simply serves to depict their heterogeneous wholeness. In this way, the ideas of “agency” and “marginalization” undergo a revision owing to their “transplantation, transference, circulation, and commerce” within new situated contexts ( Said, 1983 : 226) that are multivalent in nature.

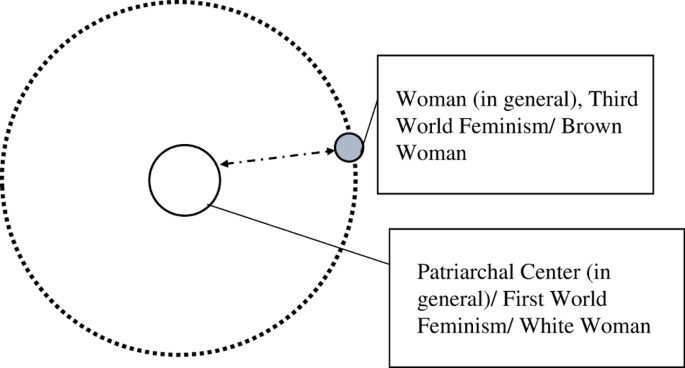

To present the marginal placement of a woman as empowering, Fig. 1 becomes the provisional origin of this argument as I engage it here to evaluate the notions of marginalization as presented by Luce Irigaray, Kristeva and Gayatri Spivak. I am not out rightly refuting their arguments, rather I am working through them to define some possibilities of empowerment that stem from a brown woman’s placement at the margin. In my opinion, which stems from my own situatedness at the margin, this permeable margin needs to be seen in a state of constant erasure that challenges the ontology of both the circumference itself and of the center.

The ocular mechanics of the center/periphery interaction in global gender discourses contour not merely the male/female relation but also the reflective mechanics in the relationship between first and third world feminisms, as well as between white and brown women. The gaze of the marginal entity is directed inwards towards the objectifying gaze of the center.

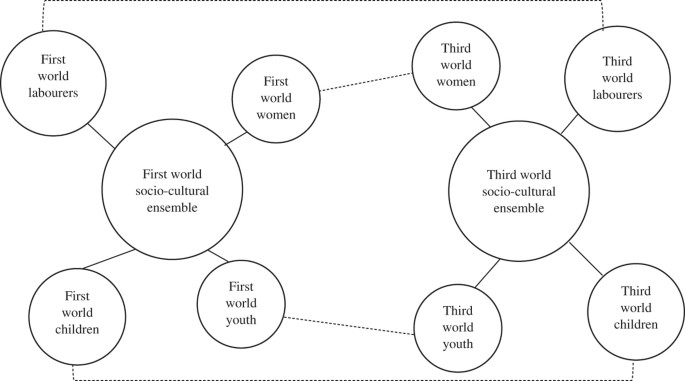

Therefore, my theorization begins by focusing on the center/periphery binary between man and woman, as well as first world and third world feminisms as shown in Fig. 1 , which limns the dynamics of interrelationality in the context of a permeable circumference. From my position as a third world woman, I see this circumference as a tentative, dotted and kinetic—hence, “limitrophic” ( Derrida, 2002 : 397)—line. This line is not to be seen as a confining limit, but an osmotic plane, where the third world woman counters the supposed center’s centripetal gaze as she is easily englobed within “supranational sociocultural ensembles” ( Kristeva, 1981 : 14). The “limitrophic” circumference serves as the first stage in my theorization for undermining the center. My contestation is that through an ophthalmic diffraction of the objectifying centripetal gaze, a third world woman can see her “self” independently of a dominating center. This problematization of the margin and its reconfiguration serves as an “alternativism” ( Suleri, 1992 [1994] : 250) that could lead to a re-articulation of the notions of agency and alterity that have framed global feminisms. Here, the concept of limitrophy needs further elucidation.

For Derrida, limitrophy was his “subject” ( Derrida, 2002 : 397) not merely because it was concerned with what was growing at the limit but what also allowed the limit to remain a tangibility, “by maintaining the limit”, and what complicated the limit ( Derrida, 2002 : 397–398). Derrida (2002) adds that while limitrophy depicts a curdling of the boundary, this curdling is designed to “multiply its figures, to complicate, thicken … precisely by making it increase and multiply” (398). Resultantly, curdling here implies that the margin enters a “liminal state between fluid and solid, which opens the border onto multiple forms beyond two defined as one side or the other of the limit” ( Oliver, 2009 : 126). What is important in this exploration is that the limit remains in its place, so that the interplay of différance continues between first and third world feminisms. The maintenance of a permeable boundary is necessary because a complete collapse of boundaries is not really feasible within the socio-cultural domains wherein they are functioning. It is not that the edge or the circumference is deleted, rather it continues to affirm itself through its malleability. However, it undergoes a perspectival shift in its operational modality. Since the curdled edge is semi-solid, therefore it allows an interplay of différance between the supposed center and periphery. The circumference becomes a malleable plane, both present and not-present; solid and not solid at the same instant, so that both entities at the center and the periphery are constituted precisely because of the delayed presentation of their presence. This deferment of the margin’s presence as an absolute also undermines the absoluteness of the supposed center so that a deferment of their ontological fixity comes into play. If the margin becomes fluctuant, it implies a corresponding fluctuation within the centripetal pull of the center. If the circumference is malleable, it plausibly leads to the notion that the center in itself is also a malleable construct.

The margin, therefore, remains actively engaged in the creation of alternative meanings within the existing Eidos or culturally accepted systems of meanings. With the center no longer being an absolute, its hierarchal placement becomes tenuous. This notion has important implications for a third world woman who has been conditioned to perceive herself as passively marginal to the first world feminist center. Not only that, owing to her marginal placement, she is also assumed to be “alienated” living under the “surveillance of a sign of identity” ( Bhabha, 1994 : 63) that pushed her within an irreversible alterity. Therefore, my argument does not erase the circumference completely; rather, it presents it as an agentive plane in a state of re-constitutive erasure. While some might argue that even if the margin and the center are in a state of constant erasure, the center is not displaced from the center. However, I argue that in challenging the absoluteness of the center, the curdled margin in effect challenges its possible connectivity to the supposed, self-validating truth of the center. It is not the location of the center, which is challenged, it is its operational function as the origin of the truth and ontology of all entities which is challenged. The center thus becomes the “originary” non-origin ( Derrida, 1967 : 19) that initiates the play of différance. This non-origin is originary precisely because it leads to the origination of other entities while undergoing an erasure itself, hence conveying the impossibility of an originating center. Within this deconstructive theoretical paradigm, the center is no longer the binding force so the marginal entity no longer needs a center to reflect it back to articulate itself. When the center is no longer an absolute originator of meaning, the marginal entity is no longer its product either. While this does not de-center the center per se , it does lead to a decentering of its operational mechanics.

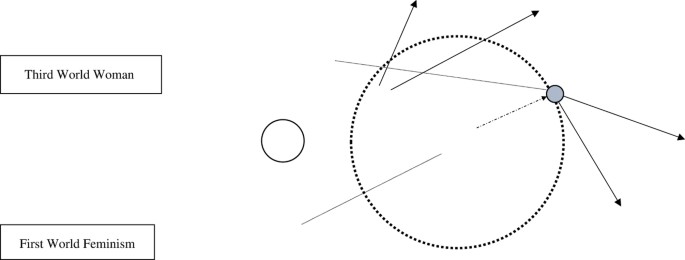

Consequently, it is the operational mechanics of the margin that are altered. The margin can thus become a space for deflecting the centripetal pull of the center’s gaze. This is because in becoming a kinetic space, the entity revolving on the circumference also becomes a participant of the kinesis that frames its context. Returning to Fig. 1 , the marginal placement of the third world woman, becomes a space of agentive manoeuvreing so that she can constitute herself in terms of her own situatedness, rather than situating herself within the discursive confines of the first world feminist discourses. In this way, she may use her situated position to deflect the gaze of the center, as is illustrated by the examples of Kishwar Naheed, Azra Abbas and Syeda Ghulam Fatima in the latter half of this article.

Problematizing the margin

As mentioned earlier, to initiate the reconfiguration of marginalization of a third world woman, I felt it necessary to bring into focus the center/periphery binary that dynamizes the global discourses on gender. This is because binary structures do not only serve as discursive “coding ingredients” ( Spivak, 2010 ), they have, in fact, reified into material realities that govern how both genders perceive each other as discourses blend with material realities such as economic, juridical and socio-cultural institutions and practices. Hence, the discursive coding of knowledge influences the way these are enacted within the material embodiment of a particular ideology. Resultantly, the discourse formations of race and gender coupled with juridico-legal and socio-economic practices lead to the concretization of the binaristic infrastructure of social functionalism. This social functionalism produces specific modes of perceiving race and gender across the cultural divide, placing one entity at the margin and the other at the center. Therefore, to re-scrutinize the idea of marginalization, it is necessary for me to initiate a “ rhetorical oscillation between a thing and its opposite” ( Spivak, 1977 : 5, author’s ) as the “provisional origin” ( Spivak, 1976 : xii) of this argument to displace and reconfigure this opposition ( Spivak, 1977 : 5). This is done to inaugurate a rethinking of a relationship through engagement in terms of non-relationship with which my argument culminates.

If Fig. 1 were to be drawn in the light of mainstream global feminism, which is based on “a metaphoricity dominated by the photological” ( Irigaray, 1974 : 20), the center is seen as a phallocratic nucleus, which defines all women. This nucleus functions as a self-proclaimed “ultimate meaning of all discourse, …, the signifier and/or the ultimate signified of all desire, … as emblem and agent of the patriarchal system” ( Irigaray, 1977 : 67). The woman, assumed to be circumambulating at the circumference like an electron, is also a mirror looking inwards. Irigaray (1974) has pointed out that a woman is not only man’s desire, she also modifies her own desire in the self-replication of the masculine One (32) through a phallo-tropic mode of self-recognition. The neological term “phallo-tropic” emanates out of Irigaray’s (1974) notion that a woman’s only relation to the origin is prescribed by man through a form of “tropism” (33) that compels her to grow only in relation to masculine source. Intriguingly, tropism suggests that even if she grows away from a masculine center, her roots remain mired within a masculine substratum; and if she grows towards a masculine nucleus, she is engaged in a heliotropic engagement with masculinity. In brief, a woman, within the existing global gender discourses remains bound to a patriarchal nucleus that stages representational practices “according to exclusively masculine parameters” ( Irigaray, 1977 : 68; author’s italics). Not only that, a major issue that I have found within these theorizations is that they cannot somehow go beyond pre-determined binaristic oppositions. Hence, the notion of womanhood remains operant within a logos that is essentially based on a patriarchal Eidos . For instance, in This Sex which is not One , Irigaray takes the following position:

It is not a matter of toppling that order so as to replace it—that amounts to the same thing in the end—but of disrupting and modifying it, starting from an ‘outside’ that is exempt, in part, from phallocratic law. ( Irigaray, 1977 : 68)

The problem with this argument is that it presents “the outside” as a space that evades the law of the phallocratic center, without taking into account the fact that the outside is in effect created by the center. The outside is that which has been exiled by the center, hence its nomenclature as an exteriority is in effect a product of the nucleus in itself. Irigaray’s acceptance of the pre-existing categories as they are, thus, concretizes the dualisms that have led to the reification of gender-based categories. Hence, the binaries of man/woman, outside/inside remain “reactionary position(s)” ( Spivak, 1986 : 77) and are related in terms of a hierarchal exercise of control in the Western feminist discourse. However, while reactionary positions remain the major pattern around which all paradigms of social functionalism are structured, a displacement within the discourses that have generated these positions may be engaged to revise them, at least theoretically. Therefore, to deconstruct them, one has to begin with provisional definitions that enable one to take a tentative stand that is constantly effaced, so that no “rigorous definition of anything is ultimately possible” ( Spivak, 1986 : 77). This deconstructivist argument by Spivak provides me with an additional groove for problematizing the notion of the “marginalization” of the third world woman in particular.

Before further delving into the problematics of the margin, I feel it necessary to take on certain assumptions regarding third world women from Julia Kristeva’s theorization. In “Women’s Time”, Kristeva (1981) states that the solidity grounded in a particular mode of re-production and representation of any entity is rooted within a specific “socio-cultural ensemble” (14). Every socio-cultural ensemble has its own temporality and memory which exceeds the confines of local history. Humanity, however, exists across multiple ensembles and temporalities. Therefore, when one socio-cultural ensemble establishes a conglomerate with other socio-cultural ensembles, it becomes connected with an overarching heterogeneous humanity. Kristeva adds that through this miscegenation, a specific regional ensemble also rises above its spatio-temporal boundaries and becomes a part of a broader temporal whole wherein one common social denominator specific to a particular region becomes reflected in another socio-cultural ensemble. For instance, when third world feminism comes in contact with other forms of feminist discourses, some common themes and issues do come to the surface, such as issues of domestic and sexual violence, gender discrimination and so on. Yet, these commonalities serve to bring to the fore significant differences as well. To cite one example, the laws governing the penalty of rape in Pakistan differ significantly from those implemented in the United States. In Pakistan, until February 2015, DNA profiling was not admissible as the main evidence to inculpate a rapist since Pakistan’s Council of Islamic Ideology insisted that it should only be taken as corroborating evidence. On the other hand, DNA evidence is sufficient for apprehending a rapist in the United States. Hence, the legal position of a Pakistani rape victim is monumentally different from that of an American rape victim owing to differences in cultural attitudes and legal procedures.

While the dynamics of the interaction between two socio-cultural ensembles that Kristeva has theorized are valid, some aspects of her paper are problematic for a third world woman. First and foremost, on the surface, Kristeva’s (1981) argument suggests that in the process of osmosis, both ensembles ought to undergo a socio-cultural and discursive meiosis as they become participants of a supra-cultural ensemble (14). This would be an ideal situation. However, in the interaction between first world and third world feminisms, it seems that it is primarily third world feminism that, in all its variegated patterns, is losing it solidity in becoming a part of a West-dominated supra-cultural ensemble. The miscegenation that she has presented would ideally take place between two ensembles that are equal in power and have similar racial and historical paradigms. This mode of miscegenation becomes problematic when a politically powerful socio-cultural ensemble, for example a European one, juxtaposes with a different and perhaps contrapositional ensemble such as that of Asia. In this context, what comes to the fore is that the inherent specificity and characteristics of a less dominating socio-cultural ensemble are threatened by those of the dominating ensemble. In this light, the validity of Spivak’s argument that Kristeva’s stance is essentially Euro-centric cannot be refuted as the importing of the West-centric associations of “marginalization” and “agency” within the third world feminist discourses also attests to this fact. This comes in conflict with Kristeva’s own theorization that when a particular socio-cultural ensemble within which first world feminism is placed, meets a different socio-cultural ensemble such as that of third world feminism, both ought to undergo an equal reconfiguration.

Second, the diagrammatic representation in Fig. 2 of Kristeva’s idea about the interactions among different socio-cultural ensembles brings another problem to light. According to Kristeva in “Women’s Time”, within all socio-cultural conglomerates, there are additional formations that are not a part of the mainstream ensemble owing to their place in its production, re-production and representation. Hence, they are attached to the periphery of their respective socio-cultural ensemble. In this way, they are not only participants of the “cursive time” ( Kristeva, 1981 : 14) of their respective region, they also go beyond its boundaries to become participants of the global “monumental time” ( Ibid .) since they become linked (as shown through the dotted lines in Fig. 2 ) with the socio-cultural groups of other sociocultural ensembles. In this way, all marginal socio-cultural groups equally become participants of a global ensemble. As a third world woman, I question whether this supra-cultural global ensemble includes both the remembered histories and the forgotten memories of all the groups involved since all groups must undergo a reciprocal, discursive osmosis. However, what is observed with reference to first world feminist discourses is that while supposedly functioning as supra-cultural ensembles, they practically co-opt third world feminist discourses within their own ideological framework. Hence, from a third world woman’s perspective, the supra-cultural ensembles are not as democratic as suggested by Kristeva. Moreover, despite being based on the notion of exchange, Kristeva’s argument does not focus on the boundaries around these ensembles nor the modalities of their functioning. As a matter of fact, her argument does not question the relationship of first world and third world feminisms, as she elucidates the culture of the Chinese women. In short, her arguments replicate the Western center and non-Western periphery structure, wherein she gives voice to the supposedly mute Chinese women.

A diagrammatic depiction of Kristeva’s idea of supra-national ensembles and the interactions among different regional socio-cultural ensembles and their peripheral formations.

On the other hand, Spivak (1981) correctly argues against the homogenization imposed on third world women by a first world feminist theorist like Kristeva saying that it is “always about her own identity” (158), thus resulting in the stereotyping of both categories of women as agentive or passive respectively. While Spivak identifies inconsistencies in Kristeva’s treatment of Chinese women, my contention against both is that in their arguments, the margin remains uncontroversial and unproblematic, particularly in Kristeva’s argument as she continues to stamp it as a stationary space wherein a third world woman is glaciated in a mute alterity. The central socio-cultural ensemble has always been seen as agentive, thus prescribing the role of the margin in terms of passivity. The margin functions merely as a line separating the regional socio-cultural ensembles from the secondary formations peripherally attached to them ( Fig. 2 ).

However, in Derridean terms, if the inside and outside are arbitrary and constituted through mutual negotiation, the margin functions as a fluctuant plane of negotiation. This idea leads to a dynamic shift within Fig. 2 . If the circumferences of all the ensembles in this diagram are seen as limitrophic, then not only does the central socio-cultural ensemble lose its hierarchal prestige, the idea of a subaltern woman also experiences a shift and leads to a re-thinking of the questions of whether the subaltern can speak ( Spivak, 1988 [1994] : 66) and whether it can be heard ( Maggio, 2007 : 419). This is because the subaltern woman’s agentive act of speaking is no longer to be defined by the Western feminist center’s ability to hear as this speaking-hearing modality experiences a multi-tiered variation. The subaltern may speak without any need to be heard by a Western listener and vice versa . Thus, the agentive/passive binary would be in a state of constant displacement as multiple patterns of agentive manoeuvrings would continue to influence the inter-ensemble interactions. Thus, a subaltern would not strictly remain a subaltern. In the context of first and third world feminisms, this reconfiguration of Kristeva’s idea leads to the notion that both ensembles enjoy a certain degree of freedom to continually constitute themselves and each other while interacting across limitrophic boundaries. This interaction extracts the ideas of the subaltern and the margin out of a monolithic closure.

Since the margin is located both within and without the inside and the outside, it blurs the binary between the two planes as shown in Fig. 1 . As a result, this blurring conjures up “a relationship that can no longer be thought within the simple difference and the uncompromising exteriority of ‘image’ and ‘reality’, of ‘outside’ and ‘inside’, of ‘appearance’ and ‘essence’, with the entire system of oppositions which necessarily follows from it”. ( Derrida, 1967 : 33). In the context of a third world woman, the tenuousness of her orbit around a central first world feminism becomes the foundation of her empowerment since she herself stands within the plane of mediation between the so-called interiority and exteriority. This allows her to defy any theoretical confinement, since she functions within “the contentious internal liminality” to speak of herself as the actively heterogeneous “emergent” ( Bhabha, 1994 : 149; author’s italics). This heterogeneity constantly undermines the reification of a third world woman as a constant category. This argument further becomes the corner stone in dismantling the center’s gaze dynamics which I shall elucidate in the ensuing section.

Deflecting the gaze of the center

As mentioned earlier, the malleable margin hosts an active process of exchange that constantly defies a rigid “closure” ( Derrida, 1967 : 4). It is pertinent to recollect here that in Derridean thought, closure is not the end since permutations may continuously take place within it. That does not imply that the entities at the margin and the center, in this case third and first world women respectively, lose their ontological specificity. This merely leads to the notion that the way these ontologies are perceived within themselves and their modalities of engagement with each other need to be reviewed in the light of the reconfiguration of the margin as a limitrophic space which grants a certain agentive freedom to marginal entities. Since the space within which I am embedded as a third world woman is fluctuant and not rigidly defined by a first world feminist center, it grants a certain leeway for me to see myself outside the first world feminist discourse. In drawing myself outside the center’s gaze and also withdrawing my own gaze from it, I may begin a process of self-configuration as a third world woman as elucidated below.

The theoretical assumptions underlying the theorization of Luce Irigaray’s photological metaphors of a woman’s situatedness vis-à-vis a masculine nucleus as shown in Fig. 1 , posit that a woman is a reflective entity that endlessly reflects the masculine center. Irigaray bases her argument on Derrida’s postulation that the paternal law is an abyme , infinitely replicating similar structures like a hall of mirrors. Explaining how patriarchy uses a woman as a mirror, Irigaray states that if the masculine ego is to be valuable, some “mirror” is needed to reassure it of its value. A woman will be the foundation of this specular duplication, giving man back “his” image and repeating it as the “same” ( Irigaray, 1977 : 52). For Irigaray, in a uterine economy, a woman is endlessly replicating the masculine center, whether it is through copulation, giving birth or nurturing a child; she is merely a means of multiplying the masculine subject’s “sameness” ( Irigaray, 1977 : 54), which is primarily concerned with “the image and the reproduction of the self. A faithful, polished mirror, empty of altering reflections. Immaculate of all auto-copies” ( Irigaray, 1977 : 136).

The application of this theoretical premise in the context of a third world woman would lead to the idea that she merely functions as a reflecting surface for a first world feminist center. Bringing Fig. 1 into play here again suggests that if the margin becomes tenuous and the center becomes weak, then it is possible for the marginal entity to turn away from the center so that it no longer has to “present its surfaces” and could easily rise out of her assumed “self-ignorance” ( Irigaray, 1977 : 136). In simple terms, with a weakened nucleus, a condition to which the porous nature of the circumference attests, the marginal entity is free to look away from the center.

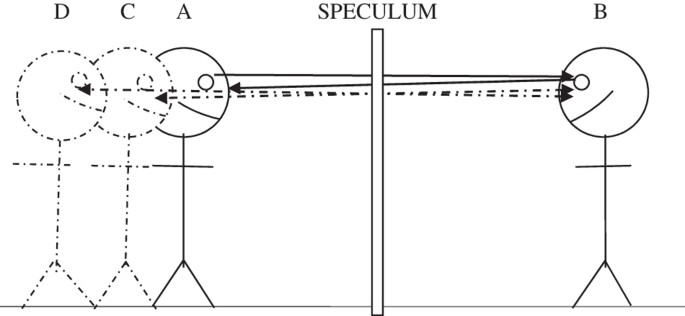

The reflecting capability of a marginal entity, such as a third world woman in the global feminist discourses, is generally described in terms of passivity. However, as a third world woman, I see this reflecting capability in agentive terms. Since the first world feminist center has come into existence precisely because the third world marginal entity continues to reflect it back; therefore, one way of challenging this center is by turning away from it so that the endless process of reflection of the same is disrupted. Fig. 3 elucidates this process.

The constant displacement of the originary center through the play of gazing back and forth between reflected and the reflections.

Figure 3 is an illustration of Derrida’s notion of reflection wherein the act of writing performs the function of a reflecting speculum. According to Derrida, the speculum produces a reflection that induces a split within the reflected so that the reflected also becomes a reflection of the reflection. If person A in Fig. 3 is the reflected individual and person B is the reflected image, the image goes on to displace the reflected person A, as is shown through the images B and C and many others that would be produced in a similar fashion. As the speculum continues to reflect the reflections and the origin at the same time, the distinctions between them are blurred so that they simultaneously become both real and unreal. According to Derrida, the world is a reflection, hence the reflection is both real and unreal so that it initiates a constant forgetting of the origin. In Fig. 3 , the origin is constantly displaced in the play of gazing back and forth. It is this ability of the speculum to displace the origin which is significant in theorizing the marginal entity. However, according to Irigaray, this displacement falls flat because even if the center or origin is displaced or split, the images remain images of the originary center while they themselves remain mired in self-ignorance as is the case with third world feminism. The fact that the terminology of Western feminist discourses has been absorbed by third world feminist discourses like a bolus endorses this view point. This observation undermines the agentive manoeuvreing of the third world woman. If the gaze mechanisms were to be viewed from Luce Irigaray’s angle, then the entire effort of deriving assumptions regarding the third world woman’s agency would fail. Hence, my argument segues from Irigaray’s to present an alternative.

According to Irigaray, a crisis would be induced within the gaze dynamics only if another mirror were used to intervene between a speculum and the reflected entity. On the other hand, my argument is that if the third world woman turns her polished surface away, it would disrupt the self-replication of the so-called center. This necessitates a modification of Fig. 1 in order for me to continue with my theorization in Fig. 4 .

The turning outwards of the marginal third world woman’s gaze, away from the first world feminist center.

In Fig. 4 , if the woman refuses to reflect the center and turns her gaze outwards, this could enable her to see the extensive space beyond the circumference. Moreover, because of the permeability of the margin and the weakening of the hold of the center, there is no ontologically fixed interior or exterior. Both exist in a state of fluctuant interactivity. Since the exteriority is no longer constructed by any nucleus, a woman can gaze in all directions, as is indicated by the multiple arrows emanating out of the shaded circle on the dotted circumference. This mode of resistance may be of use for any woman as she subverts the “voyeuristic heteronormative gaze” ( Eileraas, 2014 : 43), be it of a masculine principle or of Western feminism. This kind of subversion does not dismantle the differences between the genders and multiple races within the same gender. Rather, it enhances the differences between the two without discursively binding them within any ontological fixity. Thus both categories of first and third world women are subject to a constant revision. Within this play of différance between the first and third world feminist discourses, both the notions of agency and resistance gain an added complexity, particularly when the seeing/unseeing modality is engaged.

The act of seeing needs to be undone through an agentive act of unseeing and not through an act of reflecting back. This is evident in the indigenous literature produced by the women writers of the Sub-Continent. One notices that despite the fact that Western feminist discourses did not lace these writings, they remained exceedingly candid about issues that were considered to be taboos in their respective societies. Both the writers and the women characters that they depict are totally oblivious to the Western feminist gaze as they continue to see themselves as they are in relation to their own circumstances. They are not writing for a white audience, although they have openly touched upon exceedingly sensitive issues such as lesbianism and gang rape, not unlike their Western contemporaries. The Pakistani poet Kishwar Naheed is a case in point. Her Urdu poem “Anticlockwise” reflects a woman’s articulation as an agentive act that consolidates the viewpoint of this thought experiment, that despite being a third world woman situated at the margin, she is empowered as she addresses the men of her society, declaring:

Even after you have tied the chains of domesticity, shame and modesty around my feet even after you have paralysed me this fear will not leave you that even though I cannot walk I can still think. ( Naheed, 1968 , ‘Anticlockwise’)

In this way, a third world woman’s ability to think and articulate herself in her own terms extracts her out of any form of monolithic subalternity. She speaks, but being situated at a limitrophic margin, her being heard by a Western feminist center is not of great import. This mode of resistance again belies first world feminists’ assumptions about the passivity of third world women and suggests that the peripheral position is anything but a passive space for a third world woman. In addition to Naheed, Azra Abbas, another female Pakistani Urdu poet also proclaim women’s femininity in accordance with their own selves. Abbas’s (1996) narrator in the poem “Bull Fighter” (95) waves her sexuality like a muleta , reminding man that her sexuality is not a man’s privilege but his responsibility, thus bringing it in alignment with her contextual Islamic gender discourse. Similarly, Naheed’s (1968) poem “The Grass is Really like Me” is a proclamation of a daring selfhood despite the patriarchal insistence of mowing her down as it suggests her rhizomatic ability extend herself beyond any enclosure.

However, it is not only through writing that numerous third world women in South Asia are configuring their marginal placement as agentive. Syeda Ghulam Fatima, a Pakistani Labour activist has liberated nearly 80,000 bonded labourers, despite threats to her life. Although gaining international attention and acclaim through the Humans of New York series on Facebook in 2015, Fatima has been engaged in this form of activism since 1988, long before any international body recognized her efforts. While it is true that these women do not encompass the entire canvas of third world women’s agentive manoeuvrings on the margin, they do constitute themselves in terms of their own situatedness within their respective contexts, as had been mentioned earlier. Through this mode of attaining autonomy of expression and action, they deflect the stereotyping gaze of the Western feminist center as they discard the stereotypical assumption that a third world woman’s sexuality and articulation are repressed. Their marginality thus allows them to acquire a fluctuant femininity that evades closure. In this context, it is the third world woman who becomes absolute différance, both in her situatedness at the margin and in her ability to unsee any Western center which has a hetero-cultural gaze.

Deflecting the Western feminist gaze

The problem with most forms of contemporary resistance by third world women is problematic, particularly as one sets out to deconstruct their modes of resistance which remain mired in reflective gaze mechanics. To elucidate this point, I will take the conflict between Femen’s nude protest across Europe and the pro-Hijab protest in Egypt immediately in its after math, as cases in point. Women across the first or third worlds are co-opted by both a masculine and a Western feminist gaze. My contention is that whether it is a pro-hijab or a topless women’s protest, both are responding to the gaze mechanics of a Western feminist center and its objectifying potential. Both protests address the Western gaze that prescribes how a third world woman is to be seen or unseen. In both contexts, our modes of resistance somehow get co-opted by the male “voyeuristic heteronormative gaze” ( Eileraas, 2014 : 43), whether it is ElMahdy in the nude protest or someone else in the hijab movement. The pro-hijab women argue that the hijab gives them a sense of freedom from the intrusive masculine gaze that most men in our region have. The hijab becomes a mode of freedom for them since they are veiled from the objectifying gaze of the center and thus they gain agency outside this gaze. Yet, at the same time, the hijab also responds to a specific modality of the central masculine gaze that is prescribed within their specific cultural discourses. On the other hand, the Western feminist gaze does not see the veil as a symbol of emancipation from the masculine center, but as a mode of cultural and religious suppression. They forget that there are certain circles, even within a conservative Muslim country like Pakistan, where wearing a hijab constrains a woman’s agency and they are discriminated against.

On the other hand, ElMahdy might be nude, but she is addressing both a masculine gaze and also seeking approval from a Western feminist gaze such as that of Femen that prescribes nudity as an act of freedom for all women, regardless of their socio-cultural environment. Since the body becomes a mode of social engagement, the third world woman ends up seeing and identifying her embodiment in terms of the gaze of the Western feminist center. By debating on this gaze, through nude or pro-hijab protests, third world women are constantly re-centering the masculine principle and the white feminist discourses. What needs to be remembered at this stage is that the Western feminist ideas of embodiment are in themselves responding to the objectifying Western masculine gaze, even as a veiled third world woman responds to the objectifying masculine gaze of her own society. In this context, the establishment of Femen in itself is problematic, since it was a man, Victor Svyatski, who was its mastermind ( Eileraas, 2014 : 48). Therefore, whether it is a liberal or a conservative man or a Western feminist discourse telling a third world woman to wear or not to wear a hijab, her action is constantly problematized by the fact that even her resistance adheres to certain modalities prescribed either by her immediate patriarchal order or the Western feminist gaze.

However, in turning her back to the gaze of the Western feminist center, some mode of self-knowledge may be extracted by a third world woman. This is because a woman on the periphery can use her situatedness in such a way that she no longer depends upon the Master Signifier for her signification, as the example of Ghulam Fatima indicates. She can remain in a state of constant flux and sous rature ( Derrida, 1967 : 146) to evade any prescriptive mechanisms imposed on her by Western feminist discourses. She can not only inscribe herself as a “political and sexual subject” ( Eileraas, 2014 : 46) but also as a thinking subject, as she constantly re-thinks her position and all its possibilities. It is by positing herself as a thinking subject that a third world woman can extract the symbols of her incarceration out of their global and local implications to be customized according to an understanding emanating out of her own situation. In this way, the hijab would no longer remain a symbol of suppression, nor a nude protest remain a symbol of emancipation. It is through context-based intellectual activism that a third world woman can exceed the universal representationalist dogmas of Western feminist thoughts that posit themselves in terms of liberalism. Once, she exceeds those dogmas, her need to justify herself in terms of the Western feminist terms of emancipation would fade. For a third world woman, the prescriptive social symbols, thus, lose their rigidity. The veil is both emancipatory and constraining, depending upon her usage of it within her own context. Since she reverts to no center, the way she appropriates the socio-symbolic order remains heterogeneously open, so that they reflect her in all her contradictions. A third world woman does not have to be a uniform essentialist category. It is in embracing this fluctuant heterogeneity that she can counter any prescriptive gaze. Clothing can become an emancipatory metaphor only if the third world woman’s gaze is withdrawn from any center. Only then can she evade any ontological fixity. While it may be acceded that her options are by and large limited, between her willingness to adhere or not to adhere to a particular dress code, the freedom to sustain or alter it ought to stem from a third world woman’s perception of her own self, rather than in compliance with any kind of gaze dynamics. It is not only through embodiment or that which is thought for her by Western feminists that she can exceed the center’s gaze. It is also through the thought that she thinks herself in terms of her own situatedness that she can gain emancipation since her thoughts may then osmose into her context. Her dress should not merely be reflective of the social gaze, it should be reflective of her own thinking processes. Her consciousness needs to be in a state of constant negotiation with the multi-layered contexts within which she is embedded so that it embraces her heterogeneity. Thus, in Eisensteinian paradigms, she becomes a shifting metaphor to correlate with the shifting dynamics of her location so that she turns her back both on the phallus and on global feminism and becomes a “dispersion and discontinuity” ( Eisenstein, 1988 : 41).

What needs to be considered here is that while a first world woman perceives a hijab-wearing third world woman as suppressed and a more Westernized woman as more liberal, Eisenstein (2004) has focused on how the privileging of the English language and the hierarchal binaries contouring its episteme have played on excluding numerous indigenous forms of non-Western feminisms, assuming that genuine agency only resides in white women, (203). Therefore, the first world woman’s gaze is also functioning like the masculine center that prescribes how a third world woman ought to dress or not. As a third world woman the question that I ask is a modified version of Spivak’s question: “Who am I or who am I (not)”, not only outside the masculine gaze but also outside the gaze of first world feminism?” ( Spivak, 1981 : 179). My answer is that my position as an Other can be used as an agent for displacing the central gaze so that it can no longer define the periphery. I am and I am not, both at the same time, because I am multiple and protean, hence heterogeneous. I am pure différance and within this dynamism lies my agency. My Otherness does not have to be in terms of my being passively objectified but in using my objectification to subvert the objectifying gaze. Once the center is in a process of constant displacement by my refusal to look back at it, so is my objectification as a third world woman, because I will no longer be able to rely on it to see myself as a single integrated projection. My agentive and mutating heterogeneity would only be visible in this displacement of the center’s gaze as it defies any mode of ontological determination.