Case Study vs. Phenomenology

What's the difference.

Case study and phenomenology are both research methods used in social sciences to gain a deeper understanding of a particular phenomenon. However, they differ in their approach and focus. Case study involves an in-depth analysis of a specific case or individual, aiming to provide a detailed description and explanation of the phenomenon under investigation. It often involves collecting and analyzing various types of data, such as interviews, observations, and documents. On the other hand, phenomenology focuses on understanding the lived experiences and subjective perspectives of individuals. It aims to uncover the essence and meaning of a phenomenon by exploring the thoughts, feelings, and perceptions of those involved. Phenomenology often involves interviews and reflective analysis to gain insights into the subjective experiences of individuals. Overall, while case study emphasizes detailed analysis of a specific case, phenomenology focuses on understanding the subjective experiences and meanings associated with a phenomenon.

Further Detail

Introduction.

Research methodologies play a crucial role in understanding and exploring various phenomena in different fields. Two commonly used methodologies are case study and phenomenology. While both approaches aim to gain insights and generate knowledge, they differ in their focus, data collection methods, and analysis techniques. In this article, we will compare the attributes of case study and phenomenology, highlighting their similarities and differences.

Case study is a research method that involves an in-depth investigation of a particular individual, group, or phenomenon within its real-life context. It aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject under study by examining multiple variables and their interrelationships. Case studies often utilize a combination of qualitative and quantitative data, including interviews, observations, documents, and archival records.

One of the key strengths of case study research is its ability to provide rich and detailed descriptions of complex phenomena. By focusing on a specific case, researchers can explore the intricacies and nuances that may not be captured by broader research designs. Case studies also allow for the examination of rare or unique cases, providing valuable insights that can contribute to theory development or inform practical applications.

However, case studies also have limitations. Due to their in-depth nature, they may be time-consuming and resource-intensive. Generalizability can be a concern, as findings from a single case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations. Additionally, the subjective interpretation of data by the researcher can introduce bias, potentially impacting the validity and reliability of the study.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is a qualitative research approach that focuses on understanding the lived experiences of individuals and the meanings they attribute to those experiences. It aims to explore the essence and structure of a phenomenon as it is perceived by the participants. Phenomenological research often involves in-depth interviews, participant observations, and analysis of personal narratives or texts.

One of the main strengths of phenomenology is its emphasis on capturing the subjective experiences of individuals. By delving into the lived experiences, emotions, and perspectives of participants, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. Phenomenology also allows for the exploration of complex and abstract concepts, shedding light on the underlying meanings and motivations.

However, phenomenology also has its limitations. The findings may be highly subjective and context-dependent, limiting their generalizability. The researcher's interpretation and biases can influence the analysis and findings. Additionally, the process of phenomenological analysis can be time-consuming and require significant expertise in qualitative research methods.

While case study and phenomenology differ in their focus and approach, they share some commonalities. Both methodologies involve an in-depth exploration of a particular subject, aiming to gain a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study. They both utilize qualitative data collection methods, such as interviews and observations, to gather rich and detailed information.

However, there are also notable differences between case study and phenomenology. Case study research often examines multiple variables and their interrelationships, while phenomenology focuses on the subjective experiences and meanings attributed by individuals. Case studies aim to provide a holistic view of a complex phenomenon within its real-life context, whereas phenomenology aims to uncover the essence and structure of a phenomenon as it is perceived by the participants.

Another difference lies in the analysis techniques employed. In case study research, data analysis often involves a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods, allowing for a comprehensive examination of the subject. Phenomenological analysis, on the other hand, focuses on identifying themes, patterns, and structures within the qualitative data, aiming to uncover the underlying meanings and essences.

Furthermore, case studies are often used in applied fields, such as psychology, business, and education, where practical implications and real-life contexts are of particular interest. Phenomenology, on the other hand, is commonly employed in fields such as sociology, anthropology, and philosophy, where understanding subjective experiences and exploring abstract concepts are central to the research objectives.

Case study and phenomenology are two distinct research methodologies that offer valuable insights into various phenomena. While case study research provides a comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena within their real-life contexts, phenomenology focuses on exploring the subjective experiences and meanings attributed by individuals. Both approaches have their strengths and limitations, and the choice between them depends on the research objectives, the nature of the phenomenon under study, and the available resources. By understanding the attributes of case study and phenomenology, researchers can make informed decisions about the most appropriate methodology to employ in their studies.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

Case Study vs. Phenomenology: What's the Difference?

Key Differences

Comparison chart, data collection, application, depth vs. breadth, case study and phenomenology definitions, phenomenology, which method is broader: case study or phenomenology, is a case study the same as phenomenology, how many cases are typically studied in a case study research, are both methods qualitative in nature, what's the main goal of phenomenology, who coined the term "case study", can a case study be part of phenomenological research, which method is older: case study or phenomenology, how is phenomenology different from existentialism, can the results of a case study be generalized, can both case study and phenomenology be combined in a single research, is phenomenology only used in psychology, can a case study be quantitative, can a case study be experimental, is phenomenology only about negative experiences, what kind of data does phenomenology rely on, is phenomenology subjective, which method is more suitable for large-scale studies: case study or phenomenology, how long does a case study typically last, who is a key figure in the development of phenomenology.

Trending Comparisons

Popular Comparisons

New Comparisons

All about higher education & research

Marked Similarities and Key Differences between Case Study and Phenomenological Research Design

Case study and phenomenological research design share commonalities as qualitative research methods. Both approaches seek to provide in-depth insights into the complexities of human experiences and phenomena. They emphasize a qualitative nature, prioritizing rich, detailed exploration through methods like interviews, observations, and document analysis. Additionally, both approaches acknowledge the importance of context in understanding the subject matter and often involve flexible research designs that adapt to evolving insights. Moreover, they share a participant-centered focus, valuing the perspectives and experiences of those involved. In terms of analysis, both methodologies often employ inductive approaches, deriving themes and patterns from the collected data rather than imposing pre-existing theories.

Despite these similarities, key distinctions exist between case study and phenomenological research design. The primary focus of case studies is on a specific instance or bounded system, aiming for a holistic understanding within its real-life context. In contrast, phenomenological research design centers on uncovering the essence of lived experiences, exploring how individuals interpret and make sense of their encounters. The unit of analysis differs, with case studies examining a case itself (individual, group, organization), while phenomenological research focuses on the lived experiences of individuals.

Generalization is not the primary goal for either, but case studies may contribute to theory development, whereas phenomenological research is more inclined towards describing experiences rather than theory building. The role of the researcher also varies, with case study researchers often actively engaging with the case, while phenomenological researchers adopt a more neutral stance, bracketing preconceptions to facilitate a direct exploration of participants’ experiences.

These differences underscore the importance of choosing the most appropriate approach based on the specific research objectives and questions at hand. In this blog post, we highlight some of the noticeable similarities and stark differences between case study and phenomenological research design. But first of all, let us discuss the similarities between the two research designs.

Similarities between Case Study and Phenomenological Research Design

While case study and phenomenological research design have distinct characteristics, there are some very profound similarities between the two qualitative research approaches:

- Qualitative nature:

- Both case study and phenomenological research are qualitative research designs. They aim to explore and understand the complexities of human experiences and phenomena in depth.

- In-depth exploration:

- Both methods involve an in-depth exploration of the subject matter. Whether it’s a specific case or the lived experiences of individuals, researchers using these approaches seek to uncover rich, detailed information.

- Emphasis on context:

- Both approaches acknowledge the importance of context in understanding the phenomenon under investigation. Case studies often examine a case within its real-life context, while phenomenological research explores the subjective experiences within the context in which they occur.

- Flexible research design:

- Both case study and phenomenological research design allow for flexibility in their research design. Researchers have the freedom to adapt their methods and data collection techniques based on the evolving understanding of the phenomenon.

- Holistic approach:

- Both approaches often take a holistic perspective. Case studies aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the entire case, considering various aspects and relationships. Phenomenological research seeks to capture the essence of the lived experience as a whole.

- Use of qualitative data collection methods:

- Both methodologies typically rely on qualitative data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis. These methods allow researchers to gather rich, detailed information directly from participants.

- Participant-centered:

- Both approaches prioritize the experiences and perspectives of participants. Whether studying a case or exploring lived experiences, the goal is to capture the participant’s viewpoint and make sense of their unique context.

- Inductive analysis:

- Both case study and phenomenological research often involve inductive analysis. Researchers aim to derive themes, patterns, and insights from the data rather than imposing pre-existing theories or frameworks.

- Rich descriptions:

- Both methodologies value the production of rich, detailed descriptions. Whether describing the intricacies of a case or the nuances of individual experiences, researchers aim to provide a thorough account of the subject of study.

- Subjectivity of Researcher:

- Both methods recognize the subjectivity of the researcher and the influence they may have on the research process. Researchers in both case study and phenomenological research design often engage in reflexivity to acknowledge and address their own biases.

While these similarities exist, it’s essential to recognize the differences as well, as they shape the specific goals, methods, and outcomes of each approach. Researchers should carefully consider their research questions and objectives when choosing between case study and phenomenological research design. In the next section of the write-up, we discuss key differences between case study and phenomenological research design

Key differences between Case Study and Phenomenological Research Design

Case study and phenomenological research design are two distinct qualitative research approaches, each with its own set of characteristics and purposes. Here are the key differences between them:

- Focus and purpose:

- Focuses on a particular instance or a bounded system (the “case”).

- Aims to provide an in-depth understanding of a specific phenomenon, often within its real-life context.

- Emphasizes a holistic approach to exploring the complexities of a case.

- Focuses on understanding and describing the essence of lived experiences.

- Aims to explore how individuals make sense of and interpret their experiences.

- Emphasizes the subjective nature of the phenomenon under investigation.

- Nature of data:

- Involves a rich and detailed description of the case, including various sources of data such as interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts.

- Seeks to capture the complexity and uniqueness of the case.

- Involves gathering in-depth descriptions of participants’ experiences through methods like interviews and sometimes participant observations.

- Focuses on the meanings individuals attribute to their experiences.

- Unit of analysis:

- The unit of analysis is the case itself, which could be an individual, a group, an organization, or a community.

- The unit of analysis is the lived experience of individuals who have directly encountered the phenomenon being studied.

- Generalization:

- Generalization is typically not the primary goal; instead, the emphasis is on providing detailed insights into a specific case.

- Generalization is often not the main objective, as phenomenological research aims to explore the depth and richness of individual experiences rather than making broad generalizations.

- Analysis approach:

- Analysis often involves pattern recognition, exploring relationships between different elements within the case, and deriving meaningful insights.

- Analysis is focused on identifying and describing the essential themes and structures that characterize the lived experiences of participants.

- Theory development:

- May contribute to theory development, especially when patterns and relationships observed in the case have broader implications. However, it is not the sole and prime aim of the research endeavour

- Emphasizes the description of experiences rather than theory development. However, findings can inform or contribute to existing theories.

- Role of Researcher:

- The researcher often plays an active role, engaging with the case and collecting multiple forms of data.

- The researcher aims for a more neutral stance, trying to bracket their preconceptions to allow for a more direct exploration of participants’ experiences.

Conclusion:

In summary, while both case study and phenomenological research are qualitative approaches that delve into the richness of human experiences, they differ in their focus, purpose, unit of analysis, and the nature of data they collect and analyze. The choice between the two depends on the research question, objectives, and the nature of the phenomenon under investigation.

Dr Syed Hafeez Ahmad

You Might Also Like

What is phenomenological research design and how it is used in a qualitative research study?

A Comprehensive Guide to Understand the Philosophical underpinnings of Ethnographic Research Design

Challenges in writing a PhD Research Proposal

How to Choose a perfect Theoretical Framework for Your Ethnographic Research Study?

Choosing the Right Research Philosophy for Grounded Theory Research Design

Exploring the Profound Importance and Limitations of Ethnography

What do you think cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

No Comments Yet.

Recent Posts

Philanthropy in higher education in pakistan: learning to donate, how to overcome inordinate delays in recruitment and selection in universities in pakistan, appointment of new vice chancellors: demands urgent attention of the government in pakistan, how the graduates, medical professionals and healthcare system in pakistan shall be benefited from pm&dc accreditation by the wfme.

- How to undertake a Case Study Research: Explained with practical examples.

Recent Comments

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2021

- November 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- Academic Integrity

- Academic Leadership

- Book Review

- Critical Thinking

- Data Analysis

- Enterprising skillset

- Ethnography

- Grounded Theory

- Historical Research

- Innovations

- Leadership Theories

- Medical Education

- Personalities

- Phenomenology

- Public Policy

- Public Sector

- Research Proposal

- Universities Governance

- University-Industry Collaboration

- Work from Home

About Author

Hi, my name is Dr. Hafeez

I am a research blogger, YouTuber and content writer. This blog is aimed at sharing my knowledge, experience and insight with the academics, research scholars and policy makers about universities' governance and changing dynamics of higher education landscape in Pakistan.

Historical Research Design: A step-by-step guide on how to develop it?

- Organizations

- Planning & Activities

- Product & Services

- Structure & Systems

- Career & Education

- Entertainment

- Fashion & Beauty

- Political Institutions

- SmartPhones

- Protocols & Formats

- Communication

- Web Applications

- Household Equipments

- Career and Certifications

- Diet & Fitness

- Mathematics & Statistics

- Processed Foods

- Vegetables & Fruits

Difference Between Case Study and Phenomenology

• Categorized under Miscellaneous | Difference Between Case Study and Phenomenology

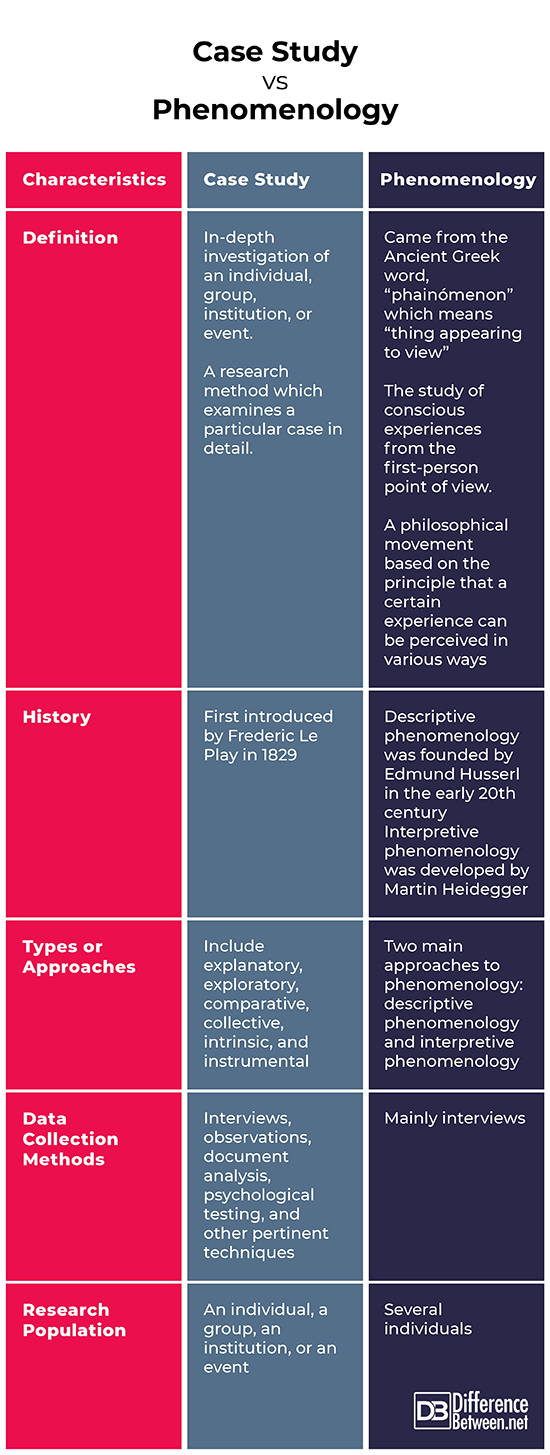

Both case study and phenomenology are involved with research processes. They are also concerned with in-depth investigations of their respective subjects. Regarding their distinctions, a case study is a research method while phenomenology is a methodology as well as a philosophical movement. More of their differences are discussed below.

What is a Case Study?

A case study is an in-depth investigation of an individual, group, institution, or event. It is a research method which examines a particular case in detail and answers the questions “why”, “how”, and “what”. Researchers who utilize this method may employ interviews, observations, document analysis, psychological testing, and other pertinent techniques in gathering information. The case-study method is believed to be first introduced by Frederic Le Play, a French engineer, sociologist, and economist, in 1829. Le Play had a comprehensive study on family budgeting (2017, Sclafani).

The following are the different types of case studies:

- Explanatory

This type focuses on an explanation for a phenomenon or research question. It answers the questions “how” and “why”.

- Exploratory

This often leads to a large-scale research since it aims to prove that further investigation is essential. Exploratory case studies answer the questions “what” and “how”.

- Comparative

This type focuses on the comparison of cases and answers questions such as, “How are cases different?” and “How are the cases alike?”.

This type uses data from various studies to frame the new study. It uses past research to find more information without spending more money and time.

This type focuses on a more comprehensive understanding of a very specific case. Intrinsic case studies aim to answer the questions “what”, “how”, and “why”.

- Instrumental

This type aims to help refine a theory or generate more insights. Instrumental case studies play supportive roles.

What is Phenomenology?

“Phenomenology” came from the Ancient Greek word, “phainómenon” which means “thing appearing to view”. It is the study of conscious experiences from the first-person point of view (Gallagher, 2012). As a methodology, it is generally a qualitative approach which centers on the collection of research participants’ descriptions of their lived experiences.

It is also a philosophical movement founded by Edmund Husserl, a German philosopher, in the early 20 th century. Phenomenology is based on the principle that a certain experience can be perceived in various ways, that an individual’s reality is different from another’s. For instance, you and your friend watched the same movie at the same time and place; however, the feelings and thoughts that you have experienced during the film are generally more positive than those of your friend’s.

There are two main approaches to phenomenology (Sloan, & Bowe, 2014):

- Descriptive Phenomenology

This is also known as transcendental phenomenology and was developed by Husserl. In this approach, the observer takes a global view of the phenomena. Its focus is on what is being experienced and on how it is being experienced.

- Interpretive Phenomenology

This is also known as hermeneutic phenomenology or existential phenomenology; this was developed by Martin Heidegger, Husserl’s student, and later his academic assistant. In this approach, the observer is one with the phenomena and is involved in interpreting meanings. As compared to descriptive phenomenology, interpretive phenomenology is more complex as it takes time and interaction with the environment into consideration.

Difference between Case Study and Phenomenology

Definition .

A case study is an in-depth investigation of an individual, group, institution, or event. It is a research method which examines a particular case in detail and answers the questions “why”, “how”, and “what”. In comparison, “phenomenology” came from the Ancient Greek word, “phainómenon” which means “thing appearing to view”. It is the study of conscious experiences from the first-person point of view. It is also a philosophical movement based on the principle that a certain experience can be perceived in various ways.

The case-study method is believed to be first introduced by Frederic Le Play, a French engineer, sociologist, and economist, in 1829. Le Play had a comprehensive study on family budgeting. On the other hand, descriptive phenomenology, also known as transcendental phenomenology, was founded by Edmund Husserl, a German philosopher, in the early 20 th century. Consequently, interpretive phenomenology, hermeneutic phenomenology, or existential phenomenology was developed by Martin Heidegger, Husserl’s student, and later his academic assistant.

Types or Approaches

The types of case studies include explanatory, exploratory, comparative, collective, intrinsic, and instrumental. In comparison, the two main approaches to phenomenology are descriptive phenomenology and interpretive phenomenology.

Data Collection Methods

Researchers who conduct case studies may employ interviews, observations, document analysis, psychological testing, and other pertinent techniques in gathering information. As for the phenomenological approach, the main data gathering technic is interviews.

Research Population

Case studies focus on an individual, a group, an institution, or an event while phenomenology research looks into the lived experiences of several individuals.

Case Study vs Phenomenology

Summary

- A case study is an in-depth investigation of an individual, group, institution, or event.

- Phenomenology is the study of conscious experiences from the first-person point of view.

- The case-study method is believed to be first introduced by Le Play while descriptive phenomenology was founded by Husserl.

- Researchers who conduct case studies may employ interviews, observations, document analysis, and psychological testing while those who conduct phenomenological research mainly use interviews.

- Case studies generally focus on an individual or group while phenomenological research delves into the experiences of several individuals.

- Recent Posts

- Difference Between Hematoma and Melanoma - February 9, 2023

- Difference Between Bruising and Necrosis - February 8, 2023

- Difference Between Brain Hematoma and Brain Hemorrhage - February 8, 2023

Sharing is caring!

- Pinterest 4

Search DifferenceBetween.net :

- Difference Between Qualitative and Quantitative

- Difference Between Qualitative and Quantitative Research

- Difference Between How and Why

- Difference Between Science and Philosophy

- Difference Between Anthropology and History

Cite APA 7 Brown, g. (2020, July 14). Difference Between Case Study and Phenomenology. Difference Between Similar Terms and Objects. http://www.differencebetween.net/miscellaneous/difference-between-case-study-and-phenomenology/. MLA 8 Brown, gene. "Difference Between Case Study and Phenomenology." Difference Between Similar Terms and Objects, 14 July, 2020, http://www.differencebetween.net/miscellaneous/difference-between-case-study-and-phenomenology/.

Leave a Response

Name ( required )

Email ( required )

Please note: comment moderation is enabled and may delay your comment. There is no need to resubmit your comment.

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail

References :

Advertisments, more in 'miscellaneous'.

- Difference Between an Arbitrator and a Mediator

- Difference Between Cellulite and Stretch Marks

- Difference Between Taliban and Al Qaeda

- Difference Between Kung Fu and Karate

- Difference Between Expression and Equation

Top Difference Betweens

Get new comparisons in your inbox:, most emailed comparisons, editor's picks.

- Difference Between MAC and IP Address

- Difference Between Platinum and White Gold

- Difference Between Civil and Criminal Law

- Difference Between GRE and GMAT

- Difference Between Immigrants and Refugees

- Difference Between DNS and DHCP

- Difference Between Computer Engineering and Computer Science

- Difference Between Men and Women

- Difference Between Book value and Market value

- Difference Between Red and White wine

- Difference Between Depreciation and Amortization

- Difference Between Bank and Credit Union

- Difference Between White Eggs and Brown Eggs

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 6: Phenomenology

Darshini Ayton

Learning outcomes

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Identify the key terms, concepts and approaches used in phenomenology.

- Explain the data collection methods and analysis for phenomenology.

- Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of phenomenological research.

What is phenomenology ?

The key concept in phenomenological studies is the individual .

Phenomenology is a method and a philosophical approach, influenced by different paradigms and disciplines. 1

Phenomenology is the everyday world from the viewpoint of the person. In this viewpoint, the emphasis is on how the individual constructs their lifeworld and seeks to understand the ‘taken for granted-ness’ of life and experiences. 2,3 Phenomenology is a practice that seeks to understand, describe and interpret human behaviour and the meaning individuals make of their experiences; it focuses on what was experienced and how it was experienced. 4 Phenomenology deals with perceptions or meanings, attitudes and beliefs, as well as feelings and emotions. The emphasis is on the lived experience and the sense an individual makes of those experiences. Since the primary source of data is the experience of the individual being studied, in-depth interviews are the most common means of data collection (see Chapter 13). Depending on the aim and research questions of the study, the method of analysis is either thematic or interpretive phenomenological analysis (Section 4).

Types of phenomenology

Descriptive phenomenology (also known as ‘transcendental phenomenology’) was founded by Edmund Husserl (1859–1938). It focuses on phenomena as perceived by the individual. 4 When reflecting on the recent phenomenon of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is clear that there is a collective experience of the pandemic and an individual experience, in which each person’s experience is influenced by their life circumstances, such as their living situation, employment, education, prior experiences with infectious diseases and health status. In addition, an individual’s life circumstances, personality, coping skills, culture, family of origin, where they live in the world and the politics of their society also influence their experience of the pandemic. Hence, the objectiveness of the pandemic is intertwined with the subjectiveness of the individual living in the pandemic.

Husserl states that descriptive phenomenological inquiry should be free of assumption and theory, to enable phenomenological reduction (or phenomenological intuiting). 1 Phenomenological reduction means putting aside all judgements or beliefs about the external world and taking nothing for granted in everyday reality. 5 This concept gave rise to a practice called ‘bracketing’ — a method of acknowledging the researcher’s preconceptions, assumptions, experiences and ‘knowing’ of a phenomenon. Bracketing is an attempt by the researcher to encounter the phenomenon in as ‘free and as unprejudiced way as possible so that it can be precisely described and understood’. 1(p132) While there is not much guidance on how to bracket, the advice provided to researchers is to record in detail the process undertaken, to provide transparency for others. Bracketing starts with reflection: a helpful practice is for the researcher to ask the following questions and write their answers as they occur, without overthinking their responses (see Box 1). This is a practice that ideally should be done multiple times during the research process: at the conception of the research idea and during design, data collection, analysis and reporting.

Box 6.1 Example s of bracketing prompts

How does my education, family background (culture), religion, politics and job relate to this topic or phenomenon?

What is my previous experience of this topic or phenomenon? Do I have negative and/or positive reactions to this topic or phenomenon? What has led to this reaction?

What have I read or understood about this topic or phenomenon?

What are my beliefs and attitudes about this topic or phenomenon? What assumptions am I making?

Interpretive or hermeneutic phenomenology was founded by Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), a junior colleague of Husserl. It focuses on the nature of being and the relationship between an individual and their lifeworld. While Heidegger’s initial work and thinking aligned with Husserl’s, he later challenged several elements of descriptive phenomenology, leading to a philosophical separation in ideas. Husserl’s descriptive phenomenology takes an epistemological (knowledge) focus while Heidegger’s interest was in ontology 4 (the nature of reality), with the key phrase ‘being-in-the-world’ referencing how humans exist, act or participate in the world. 1 In descriptive phenomenology, the practice of bracketing is endorsed and experience is stripped from context to examine and understand it.

Interpretive or hermeneutic phenomenology embraces the intertwining of an individual’s subjective experience with their social, cultural and political contexts, regardless of whether they are conscious of this influence. 4 Interpretive or hermeneutic phenomenology moves beyond description to the interpretation of the phenomenon and the study of meanings through the lifeworld of the individual. While the researcher’s knowledge, experience, assumptions and beliefs are valued, they do need to be acknowledged as part of the process of analysis. 4

For example, Singh and colleagues wanted to understand the experiences of managers involved in the implementation of quality improvement projects in an assisted living facility, and thus they conducted a hermeneutic phenomenology study. 6 The objective was to ‘understand how managers define the quality of patient care and administrative processes’, alongside an exploration of the participant’s perspectives of leadership and challenges to the implementation of quality improvement strategies. (p3) Semi-structured interviews (60–75 minutes in duration) were conducted with six managers and data was analysed using inductive thematic techniques.

New phenomenology , or American phenomenology , has initiated a transition in the focus of phenomenology from the nature and understanding of the phenomenon to the lived experience of individuals experiencing the phenomenon. This transition may seem subtle but fundamentally is related to a shift away from the philosophical approaches of Husserl and Heidegger to an applied approach to research. 1 New phenomenology does not undergo the phenomenological reductionist approach outlined by Husserl to examine and understand the essence of the phenomenon. Dowling 1 emphasises that this phenomenological reduction, which leads to an attempt to disengage the researcher from the participant, is not desired or practical in applied research such as in nursing studies. Hence, new phenomenology is aligned with interpretive phenomenology, embracing the intersubjectivity (shared subjective experiences between two or more people) of the research approach. 1

Another feature of new phenomenology is the positioning of culture in the analysis of an individual’s experience. This is not the case for the traditional phenomenological approaches 1 ; hence, philosophical approaches by European philosophers Husserl and Heidegger can be used if the objective is to explore or understand the phenomenon itself or the object of the participant’s experience. The methods of new phenomenology, or American phenomenology, should be applied if the researcher seeks to understand a person’s experience(s) of the phenomenon. 1

See Table 6.1. for two different examples of phenomenological research.

Advantages and disadvantages of phenomenological research

Phenomenology has many advantages, including that it can present authentic accounts of complex phenomena; it is a humanistic style of research that demonstrates respect for the whole individual; and the descriptions of experiences can tell an interesting story about the phenomenon and the individuals experiencing it. 7 Criticisms of phenomenology tend to focus on the individuality of the results, which makes them non-generalisable, considered too subjective and therefore invalid. However, the reason a researcher may choose a phenomenological approach is to understand the individual, subjective experiences of an individual; thus, as with many qualitative research designs, the findings will not be generalisable to a larger population. 7,8

Table 6.1. Examples of phenomenological studies

Phenomenology focuses on understanding a phenomenon from the perspective of individual experience (descriptive and interpretive phenomenology) or from the lived experience of the phenomenon by individuals (new phenomenology). This individualised focus lends itself to in-depth interviews and small scale research projects.

- Dowling M. From Husserl to van Manen. A review of different phenomenological approaches. Int J Nurs Stud . 2007;44(1):131-42. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.11.026

- Creswell J, Hanson W, Clark Plano V, Morales A. Qualitative research designs: selection and implementation. Couns Psychol . 2007;35(2):236-264. doi:10.1177/0011000006287390

- Morse JM, Field PA. Qualitative Research Methods for Health Professionals. 2nd ed. SAGE; 1995.

- Neubauer BE, Witkop CT, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Educ . 2019;8(2):90-97. doi:10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2

- Merleau-Ponty M, Landes D, Carman T, Lefort C. Phenomenology of Perception . 1st ed. Routledge; 2011.

- Singh J, Wiese A, Sillerud B. Using phenomenological hermeneutics to understand the experiences of managers working with quality improvement strategies in an assisted living facility. Healthcare (Basel) . 2019;7(3):87. doi:10.3390/healthcare7030087

- Liamputtong P, Ezzy D. Qualitative Research Methods: A Health Focus . Oxford University Press; 1999.

- Liamputtong P. Qualitative Research Methods . 5th ed. Oxford University Press; 2020.

- Abbaspour Z, Vasel G, Khojastehmehr R. Investigating the lived experiences of abused mothers: a phenomenological study. Journal of Qualitative Research in Health Sciences . 2021;10(2)2:108-114. doi:10.22062/JQR.2021.193653.0

- Engberink AO, Mailly M, Marco V, et al. A phenomenological study of nurses experience about their palliative approach and their use of mobile palliative care teams in medical and surgical care units in France. BMC Palliat Care . 2020;19:34. doi:10.1186/s12904-020-0536-0

Qualitative Research – a practical guide for health and social care researchers and practitioners Copyright © 2023 by Darshini Ayton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

From John W. Creswell \(2016\). 30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher \ . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Varieties of Qualitative Research Methods pp 377–382 Cite as

Phenomenological Studies

- Thomas Ndame 4

- First Online: 02 January 2023

3841 Accesses

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

Phenomenology, as both philosophy and research methodology, originated from the writings of a group of European philosophers with the movement championed by two German philosophers namely Franz Brentano (1838–1917) and Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) in the twentieth century.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Creswell, J.W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches . Sage.

Google Scholar

Husserl, E. (1964a). Psychological and transcendental phenomenology and the confrontation with Heidegger. Husserl Studies, 17 , 125–148. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010771906591

Article Google Scholar

Husserl, E. (1964b). The Paris lectures . Martinus Nijhoff.

Book Google Scholar

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2010). Designing qualitative research (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

Padilla-Díaz, M. (2015). Phenomenology in qualitative educational research: Philosophy as science or philosophical science? International Journal of Educational Excellence, 1 (2), 101–110.

Privitera, G., J., & Ahlgrim-Delzell, L. (2019). Research methods for education . Sage Publication.

Stone, F. (1979). Philosophical phenomenology: A methodology for holistic educational research. Multicultural Research Guides Series 4 . Connecticut University, Storrs. Thut (I.N.) World Education Centre.

Vallack, J. (2015). Alchemy for inquiry: A methodology of applied phenomenology in educational research. James Cook University, AARE Conference (pp. 1–10), Western Australia.

Additional Reading

Engelland, C. (2020). Phenomenology . MIT Press.

Manen, M., V. (2014). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing . Routledge.

Priya, A. (2017). Phenomenological social research: Some observations from the field. Qualitative Research Journal , 17(4) 294–305. DOI https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-08-2016-0047

Online Resources

Qualitative Research Design: Phenomenology (15.32 Minutes). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3aYRlNrO6oA .

Phenomenological Research (7.24). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RzDuxiALnCQ .

Creating an Effective Phenomenological Study (5.34). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZrdgqkpDTGY .

Susan Kozel: Phenomenology—Practice Based Research in the Arts, Stanford University. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mv7Vp3NPKw4 .

Phenomenology—IPA and Narrative Analysis. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xU9S8aRL6ys .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Buea, Buea, Cameroon

Thomas Ndame

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Thomas Ndame .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Administration, College of Education, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

Janet Mola Okoko

Scott Tunison

Department of Educational Administration, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada

Keith D. Walker

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Ndame, T. (2023). Phenomenological Studies. In: Okoko, J.M., Tunison, S., Walker, K.D. (eds) Varieties of Qualitative Research Methods. Springer Texts in Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04394-9_58

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04394-9_58

Published : 02 January 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-04396-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-04394-9

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Case Study vs. Phenomenology — What's the Difference?

Difference Between Case Study and Phenomenology

Table of contents, key differences, comparison chart, data origin, application fields, philosophical roots, compare with definitions, phenomenology, common curiosities, does phenomenology always involve interviews, are case studies subjective, is a case study quantitative or qualitative, is phenomenology purely descriptive, how does phenomenology differ from other qualitative methods, how long does a case study typically last, can a case study involve multiple cases, what's the primary goal of phenomenology, can case studies be published, is phenomenology only a research method, why are case studies important in business, does phenomenology aim to generalize findings, what's a limitation of the case study method, can a case study be exploratory, is phenomenology tied to any specific discipline, share your discovery.

Author Spotlight

Popular Comparisons

Trending Comparisons

New Comparisons

Trending Terms

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is the study of structures of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view. The central structure of an experience is its intentionality, its being directed toward something, as it is an experience of or about some object. An experience is directed toward an object by virtue of its content or meaning (which represents the object) together with appropriate enabling conditions.

Phenomenology as a discipline is distinct from but related to other key disciplines in philosophy, such as ontology, epistemology, logic, and ethics. Phenomenology has been practiced in various guises for centuries, but it came into its own in the early 20th century in the works of Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty and others. Phenomenological issues of intentionality, consciousness, qualia, and first-person perspective have been prominent in recent philosophy of mind.

1. What is Phenomenology?

2. the discipline of phenomenology, 3. from phenomena to phenomenology, 4. the history and varieties of phenomenology, 5. phenomenology and ontology, epistemology, logic, ethics, 6. phenomenology and philosophy of mind, 7. phenomenology in contemporary consciousness theory, classical texts, contemporary studies, other internet resources, related entries.

Phenomenology is commonly understood in either of two ways: as a disciplinary field in philosophy, or as a movement in the history of philosophy.

The discipline of phenomenology may be defined initially as the study of structures of experience, or consciousness. Literally, phenomenology is the study of “phenomena”: appearances of things, or things as they appear in our experience, or the ways we experience things, thus the meanings things have in our experience. Phenomenology studies conscious experience as experienced from the subjective or first person point of view. This field of philosophy is then to be distinguished from, and related to, the other main fields of philosophy: ontology (the study of being or what is), epistemology (the study of knowledge), logic (the study of valid reasoning), ethics (the study of right and wrong action), etc.

The historical movement of phenomenology is the philosophical tradition launched in the first half of the 20 th century by Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Jean-Paul Sartre, et al . In that movement, the discipline of phenomenology was prized as the proper foundation of all philosophy—as opposed, say, to ethics or metaphysics or epistemology. The methods and characterization of the discipline were widely debated by Husserl and his successors, and these debates continue to the present day. (The definition of phenomenology offered above will thus be debatable, for example, by Heideggerians, but it remains the starting point in characterizing the discipline.)

In recent philosophy of mind, the term “phenomenology” is often restricted to the characterization of sensory qualities of seeing, hearing, etc.: what it is like to have sensations of various kinds. However, our experience is normally much richer in content than mere sensation. Accordingly, in the phenomenological tradition, phenomenology is given a much wider range, addressing the meaning things have in our experience, notably, the significance of objects, events, tools, the flow of time, the self, and others, as these things arise and are experienced in our “life-world”.

Phenomenology as a discipline has been central to the tradition of continental European philosophy throughout the 20 th century, while philosophy of mind has evolved in the Austro-Anglo-American tradition of analytic philosophy that developed throughout the 20 th century. Yet the fundamental character of our mental activity is pursued in overlapping ways within these two traditions. Accordingly, the perspective on phenomenology drawn in this article will accommodate both traditions. The main concern here will be to characterize the discipline of phenomenology, in a contemporary purview, while also highlighting the historical tradition that brought the discipline into its own.

Basically, phenomenology studies the structure of various types of experience ranging from perception, thought, memory, imagination, emotion, desire, and volition to bodily awareness, embodied action, and social activity, including linguistic activity. The structure of these forms of experience typically involves what Husserl called “intentionality”, that is, the directedness of experience toward things in the world, the property of consciousness that it is a consciousness of or about something. According to classical Husserlian phenomenology, our experience is directed toward—represents or “intends”—things only through particular concepts, thoughts, ideas, images, etc. These make up the meaning or content of a given experience, and are distinct from the things they present or mean.

The basic intentional structure of consciousness, we find in reflection or analysis, involves further forms of experience. Thus, phenomenology develops a complex account of temporal awareness (within the stream of consciousness), spatial awareness (notably in perception), attention (distinguishing focal and marginal or “horizonal” awareness), awareness of one’s own experience (self-consciousness, in one sense), self-awareness (awareness-of-oneself), the self in different roles (as thinking, acting, etc.), embodied action (including kinesthetic awareness of one’s movement), purpose or intention in action (more or less explicit), awareness of other persons (in empathy, intersubjectivity, collectivity), linguistic activity (involving meaning, communication, understanding others), social interaction (including collective action), and everyday activity in our surrounding life-world (in a particular culture).

Furthermore, in a different dimension, we find various grounds or enabling conditions—conditions of the possibility—of intentionality, including embodiment, bodily skills, cultural context, language and other social practices, social background, and contextual aspects of intentional activities. Thus, phenomenology leads from conscious experience into conditions that help to give experience its intentionality. Traditional phenomenology has focused on subjective, practical, and social conditions of experience. Recent philosophy of mind, however, has focused especially on the neural substrate of experience, on how conscious experience and mental representation or intentionality are grounded in brain activity. It remains a difficult question how much of these grounds of experience fall within the province of phenomenology as a discipline. Cultural conditions thus seem closer to our experience and to our familiar self-understanding than do the electrochemical workings of our brain, much less our dependence on quantum-mechanical states of physical systems to which we may belong. The cautious thing to say is that phenomenology leads in some ways into at least some background conditions of our experience.

The discipline of phenomenology is defined by its domain of study, its methods, and its main results.

Phenomenology studies structures of conscious experience as experienced from the first-person point of view, along with relevant conditions of experience. The central structure of an experience is its intentionality, the way it is directed through its content or meaning toward a certain object in the world.

We all experience various types of experience including perception, imagination, thought, emotion, desire, volition, and action. Thus, the domain of phenomenology is the range of experiences including these types (among others). Experience includes not only relatively passive experience as in vision or hearing, but also active experience as in walking or hammering a nail or kicking a ball. (The range will be specific to each species of being that enjoys consciousness; our focus is on our own, human, experience. Not all conscious beings will, or will be able to, practice phenomenology, as we do.)

Conscious experiences have a unique feature: we experience them, we live through them or perform them. Other things in the world we may observe and engage. But we do not experience them, in the sense of living through or performing them. This experiential or first-person feature—that of being experienced—is an essential part of the nature or structure of conscious experience: as we say, “I see / think / desire / do …” This feature is both a phenomenological and an ontological feature of each experience: it is part of what it is for the experience to be experienced (phenomenological) and part of what it is for the experience to be (ontological).

How shall we study conscious experience? We reflect on various types of experiences just as we experience them. That is to say, we proceed from the first-person point of view. However, we do not normally characterize an experience at the time we are performing it. In many cases we do not have that capability: a state of intense anger or fear, for example, consumes all of one’s psychic focus at the time. Rather, we acquire a background of having lived through a given type of experience, and we look to our familiarity with that type of experience: hearing a song, seeing a sunset, thinking about love, intending to jump a hurdle. The practice of phenomenology assumes such familiarity with the type of experiences to be characterized. Importantly, also, it is types of experience that phenomenology pursues, rather than a particular fleeting experience—unless its type is what interests us.

Classical phenomenologists practiced some three distinguishable methods. (1) We describe a type of experience just as we find it in our own (past) experience. Thus, Husserl and Merleau-Ponty spoke of pure description of lived experience. (2) We interpret a type of experience by relating it to relevant features of context. In this vein, Heidegger and his followers spoke of hermeneutics, the art of interpretation in context, especially social and linguistic context. (3) We analyze the form of a type of experience. In the end, all the classical phenomenologists practiced analysis of experience, factoring out notable features for further elaboration.

These traditional methods have been ramified in recent decades, expanding the methods available to phenomenology. Thus: (4) In a logico-semantic model of phenomenology, we specify the truth conditions for a type of thinking (say, where I think that dogs chase cats) or the satisfaction conditions for a type of intention (say, where I intend or will to jump that hurdle). (5) In the experimental paradigm of cognitive neuroscience, we design empirical experiments that tend to confirm or refute aspects of experience (say, where a brain scan shows electrochemical activity in a specific region of the brain thought to subserve a type of vision or emotion or motor control). This style of “neurophenomenology” assumes that conscious experience is grounded in neural activity in embodied action in appropriate surroundings—mixing pure phenomenology with biological and physical science in a way that was not wholly congenial to traditional phenomenologists.

What makes an experience conscious is a certain awareness one has of the experience while living through or performing it. This form of inner awareness has been a topic of considerable debate, centuries after the issue arose with Locke’s notion of self-consciousness on the heels of Descartes’ sense of consciousness ( conscience , co-knowledge). Does this awareness-of-experience consist in a kind of inner observation of the experience, as if one were doing two things at once? (Brentano argued no.) Is it a higher-order perception of one’s mind’s operation, or is it a higher-order thought about one’s mental activity? (Recent theorists have proposed both.) Or is it a different form of inherent structure? (Sartre took this line, drawing on Brentano and Husserl.) These issues are beyond the scope of this article, but notice that these results of phenomenological analysis shape the characterization of the domain of study and the methodology appropriate to the domain. For awareness-of-experience is a defining trait of conscious experience, the trait that gives experience a first-person, lived character. It is that lived character of experience that allows a first-person perspective on the object of study, namely, experience, and that perspective is characteristic of the methodology of phenomenology.

Conscious experience is the starting point of phenomenology, but experience shades off into less overtly conscious phenomena. As Husserl and others stressed, we are only vaguely aware of things in the margin or periphery of attention, and we are only implicitly aware of the wider horizon of things in the world around us. Moreover, as Heidegger stressed, in practical activities like walking along, or hammering a nail, or speaking our native tongue, we are not explicitly conscious of our habitual patterns of action. Furthermore, as psychoanalysts have stressed, much of our intentional mental activity is not conscious at all, but may become conscious in the process of therapy or interrogation, as we come to realize how we feel or think about something. We should allow, then, that the domain of phenomenology—our own experience—spreads out from conscious experience into semi-conscious and even unconscious mental activity, along with relevant background conditions implicitly invoked in our experience. (These issues are subject to debate; the point here is to open the door to the question of where to draw the boundary of the domain of phenomenology.)

To begin an elementary exercise in phenomenology, consider some typical experiences one might have in everyday life, characterized in the first person:

- I see that fishing boat off the coast as dusk descends over the Pacific.

- I hear that helicopter whirring overhead as it approaches the hospital.

- I am thinking that phenomenology differs from psychology.

- I wish that warm rain from Mexico were falling like last week.

- I imagine a fearsome creature like that in my nightmare.

- I intend to finish my writing by noon.

- I walk carefully around the broken glass on the sidewalk.

- I stroke a backhand cross-court with that certain underspin.

- I am searching for the words to make my point in conversation.

Here are rudimentary characterizations of some familiar types of experience. Each sentence is a simple form of phenomenological description, articulating in everyday English the structure of the type of experience so described. The subject term “I” indicates the first-person structure of the experience: the intentionality proceeds from the subject. The verb indicates the type of intentional activity described: perception, thought, imagination, etc. Of central importance is the way that objects of awareness are presented or intended in our experiences, especially, the way we see or conceive or think about objects. The direct-object expression (“that fishing boat off the coast”) articulates the mode of presentation of the object in the experience: the content or meaning of the experience, the core of what Husserl called noema. In effect, the object-phrase expresses the noema of the act described, that is, to the extent that language has appropriate expressive power. The overall form of the given sentence articulates the basic form of intentionality in the experience: subject-act-content-object.

Rich phenomenological description or interpretation, as in Husserl, Merleau-Ponty et al ., will far outrun such simple phenomenological descriptions as above. But such simple descriptions bring out the basic form of intentionality. As we interpret the phenomenological description further, we may assess the relevance of the context of experience. And we may turn to wider conditions of the possibility of that type of experience. In this way, in the practice of phenomenology, we classify, describe, interpret, and analyze structures of experiences in ways that answer to our own experience.

In such interpretive-descriptive analyses of experience, we immediately observe that we are analyzing familiar forms of consciousness, conscious experience of or about this or that. Intentionality is thus the salient structure of our experience, and much of phenomenology proceeds as the study of different aspects of intentionality. Thus, we explore structures of the stream of consciousness, the enduring self, the embodied self, and bodily action. Furthermore, as we reflect on how these phenomena work, we turn to the analysis of relevant conditions that enable our experiences to occur as they do, and to represent or intend as they do. Phenomenology then leads into analyses of conditions of the possibility of intentionality, conditions involving motor skills and habits, background social practices, and often language, with its special place in human affairs.

The Oxford English Dictionary presents the following definition: “Phenomenology. a. The science of phenomena as distinct from being (ontology). b. That division of any science which describes and classifies its phenomena. From the Greek phainomenon , appearance.” In philosophy, the term is used in the first sense, amid debates of theory and methodology. In physics and philosophy of science, the term is used in the second sense, albeit only occasionally.

In its root meaning, then, phenomenology is the study of phenomena : literally, appearances as opposed to reality. This ancient distinction launched philosophy as we emerged from Plato’s cave. Yet the discipline of phenomenology did not blossom until the 20th century and remains poorly understood in many circles of contemporary philosophy. What is that discipline? How did philosophy move from a root concept of phenomena to the discipline of phenomenology?

Originally, in the 18th century, “phenomenology” meant the theory of appearances fundamental to empirical knowledge, especially sensory appearances. The Latin term “Phenomenologia” was introduced by Christoph Friedrich Oetinger in 1736. Subsequently, the German term “Phänomenologia” was used by Johann Heinrich Lambert, a follower of Christian Wolff. Immanuel Kant used the term occasionally in various writings, as did Johann Gottlieb Fichte. In 1807, G. W. F. Hegel wrote a book titled Phänomenologie des Geistes (usually translated as Phenomenology of Spirit ). By 1889 Franz Brentano used the term to characterize what he called “descriptive psychology”. From there Edmund Husserl took up the term for his new science of consciousness, and the rest is history.

Suppose we say phenomenology studies phenomena: what appears to us—and its appearing. How shall we understand phenomena? The term has a rich history in recent centuries, in which we can see traces of the emerging discipline of phenomenology.

In a strict empiricist vein, what appears before the mind are sensory data or qualia: either patterns of one’s own sensations (seeing red here now, feeling this ticklish feeling, hearing that resonant bass tone) or sensible patterns of worldly things, say, the looks and smells of flowers (what John Locke called secondary qualities of things). In a strict rationalist vein, by contrast, what appears before the mind are ideas, rationally formed “clear and distinct ideas” (in René Descartes’ ideal). In Immanuel Kant’s theory of knowledge, fusing rationalist and empiricist aims, what appears to the mind are phenomena defined as things-as-they-appear or things-as-they-are-represented (in a synthesis of sensory and conceptual forms of objects-as-known). In Auguste Comte’s theory of science, phenomena ( phenomenes ) are the facts ( faits , what occurs) that a given science would explain.

In 18 th and 19 th century epistemology, then, phenomena are the starting points in building knowledge, especially science. Accordingly, in a familiar and still current sense, phenomena are whatever we observe (perceive) and seek to explain.

As the discipline of psychology emerged late in the 19 th century, however, phenomena took on a somewhat different guise. In Franz Brentano’s Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint (1874), phenomena are what occur in the mind: mental phenomena are acts of consciousness (or their contents), and physical phenomena are objects of external perception starting with colors and shapes. For Brentano, physical phenomena exist “intentionally” in acts of consciousness. This view revives a Medieval notion Brentano called “intentional in-existence”, but the ontology remains undeveloped (what is it to exist in the mind, and do physical objects exist only in the mind?). More generally, we might say, phenomena are whatever we are conscious of: objects and events around us, other people, ourselves, even (in reflection) our own conscious experiences, as we experience these. In a certain technical sense, phenomena are things as they are given to our consciousness, whether in perception or imagination or thought or volition. This conception of phenomena would soon inform the new discipline of phenomenology.

Brentano distinguished descriptive psychology from genetic psychology. Where genetic psychology seeks the causes of various types of mental phenomena, descriptive psychology defines and classifies the various types of mental phenomena, including perception, judgment, emotion, etc. According to Brentano, every mental phenomenon, or act of consciousness, is directed toward some object, and only mental phenomena are so directed. This thesis of intentional directedness was the hallmark of Brentano’s descriptive psychology. In 1889 Brentano used the term “phenomenology” for descriptive psychology, and the way was paved for Husserl’s new science of phenomenology.

Phenomenology as we know it was launched by Edmund Husserl in his Logical Investigations (1900–01). Two importantly different lines of theory came together in that monumental work: psychological theory, on the heels of Franz Brentano (and also William James, whose Principles of Psychology appeared in 1891 and greatly impressed Husserl); and logical or semantic theory, on the heels of Bernard Bolzano and Husserl’s contemporaries who founded modern logic, including Gottlob Frege. (Interestingly, both lines of research trace back to Aristotle, and both reached importantly new results in Husserl’s day.)

Husserl’s Logical Investigations was inspired by Bolzano’s ideal of logic, while taking up Brentano’s conception of descriptive psychology. In his Theory of Science (1835) Bolzano distinguished between subjective and objective ideas or representations ( Vorstellungen ). In effect Bolzano criticized Kant and before him the classical empiricists and rationalists for failing to make this sort of distinction, thereby rendering phenomena merely subjective. Logic studies objective ideas, including propositions, which in turn make up objective theories as in the sciences. Psychology would, by contrast, study subjective ideas, the concrete contents (occurrences) of mental activities in particular minds at a given time. Husserl was after both, within a single discipline. So phenomena must be reconceived as objective intentional contents (sometimes called intentional objects) of subjective acts of consciousness. Phenomenology would then study this complex of consciousness and correlated phenomena. In Ideas I (Book One, 1913) Husserl introduced two Greek words to capture his version of the Bolzanoan distinction: noesis and noema , from the Greek verb noéō (νοέω), meaning to perceive, think, intend, whence the noun nous or mind. The intentional process of consciousness is called noesis , while its ideal content is called noema . The noema of an act of consciousness Husserl characterized both as an ideal meaning and as “the object as intended”. Thus the phenomenon, or object-as-it-appears, becomes the noema, or object-as-it-is-intended. The interpretations of Husserl’s theory of noema have been several and amount to different developments of Husserl’s basic theory of intentionality. (Is the noema an aspect of the object intended, or rather a medium of intention?)

For Husserl, then, phenomenology integrates a kind of psychology with a kind of logic. It develops a descriptive or analytic psychology in that it describes and analyzes types of subjective mental activity or experience, in short, acts of consciousness. Yet it develops a kind of logic—a theory of meaning (today we say logical semantics)—in that it describes and analyzes objective contents of consciousness: ideas, concepts, images, propositions, in short, ideal meanings of various types that serve as intentional contents, or noematic meanings, of various types of experience. These contents are shareable by different acts of consciousness, and in that sense they are objective, ideal meanings. Following Bolzano (and to some extent the platonistic logician Hermann Lotze), Husserl opposed any reduction of logic or mathematics or science to mere psychology, to how people happen to think, and in the same spirit he distinguished phenomenology from mere psychology. For Husserl, phenomenology would study consciousness without reducing the objective and shareable meanings that inhabit experience to merely subjective happenstances. Ideal meaning would be the engine of intentionality in acts of consciousness.

A clear conception of phenomenology awaited Husserl’s development of a clear model of intentionality. Indeed, phenomenology and the modern concept of intentionality emerged hand-in-hand in Husserl’s Logical Investigations (1900–01). With theoretical foundations laid in the Investigations , Husserl would then promote the radical new science of phenomenology in Ideas I (1913). And alternative visions of phenomenology would soon follow.

Phenomenology came into its own with Husserl, much as epistemology came into its own with Descartes, and ontology or metaphysics came into its own with Aristotle on the heels of Plato. Yet phenomenology has been practiced, with or without the name, for many centuries. When Hindu and Buddhist philosophers reflected on states of consciousness achieved in a variety of meditative states, they were practicing phenomenology. When Descartes, Hume, and Kant characterized states of perception, thought, and imagination, they were practicing phenomenology. When Brentano classified varieties of mental phenomena (defined by the directedness of consciousness), he was practicing phenomenology. When William James appraised kinds of mental activity in the stream of consciousness (including their embodiment and their dependence on habit), he too was practicing phenomenology. And when recent analytic philosophers of mind have addressed issues of consciousness and intentionality, they have often been practicing phenomenology. Still, the discipline of phenomenology, its roots tracing back through the centuries, came to full flower in Husserl.

Husserl’s work was followed by a flurry of phenomenological writing in the first half of the 20 th century. The diversity of traditional phenomenology is apparent in the Encyclopedia of Phenomenology (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1997, Dordrecht and Boston), which features separate articles on some seven types of phenomenology. (1) Transcendental constitutive phenomenology studies how objects are constituted in pure or transcendental consciousness, setting aside questions of any relation to the natural world around us. (2) Naturalistic constitutive phenomenology studies how consciousness constitutes or takes things in the world of nature, assuming with the natural attitude that consciousness is part of nature. (3) Existential phenomenology studies concrete human existence, including our experience of free choice or action in concrete situations. (4) Generative historicist phenomenology studies how meaning, as found in our experience, is generated in historical processes of collective experience over time. (5) Genetic phenomenology studies the genesis of meanings of things within one’s own stream of experience. (6) Hermeneutical phenomenology studies interpretive structures of experience, how we understand and engage things around us in our human world, including ourselves and others. (7) Realistic phenomenology studies the structure of consciousness and intentionality, assuming it occurs in a real world that is largely external to consciousness and not somehow brought into being by consciousness.

The most famous of the classical phenomenologists were Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, and Merleau-Ponty. In these four thinkers we find different conceptions of phenomenology, different methods, and different results. A brief sketch of their differences will capture both a crucial period in the history of phenomenology and a sense of the diversity of the field of phenomenology.

In his Logical Investigations (1900–01) Husserl outlined a complex system of philosophy, moving from logic to philosophy of language, to ontology (theory of universals and parts of wholes), to a phenomenological theory of intentionality, and finally to a phenomenological theory of knowledge. Then in Ideas I (1913) he focused squarely on phenomenology itself. Husserl defined phenomenology as “the science of the essence of consciousness”, centered on the defining trait of intentionality, approached explicitly “in the first person”. (See Husserl, Ideas I, ¤¤33ff.) In this spirit, we may say phenomenology is the study of consciousness—that is, conscious experience of various types—as experienced from the first-person point of view. In this discipline we study different forms of experience just as we experience them, from the perspective of the subject living through or performing them. Thus, we characterize experiences of seeing, hearing, imagining, thinking, feeling (i.e., emotion), wishing, desiring, willing, and also acting, that is, embodied volitional activities of walking, talking, cooking, carpentering, etc. However, not just any characterization of an experience will do. Phenomenological analysis of a given type of experience will feature the ways in which we ourselves would experience that form of conscious activity. And the leading property of our familiar types of experience is their intentionality, their being a consciousness of or about something, something experienced or presented or engaged in a certain way. How I see or conceptualize or understand the object I am dealing with defines the meaning of that object in my current experience. Thus, phenomenology features a study of meaning, in a wide sense that includes more than what is expressed in language.

In Ideas I Husserl presented phenomenology with a transcendental turn. In part this means that Husserl took on the Kantian idiom of “transcendental idealism”, looking for conditions of the possibility of knowledge, or of consciousness generally, and arguably turning away from any reality beyond phenomena. But Husserl’s transcendental turn also involved his discovery of the method of epoché (from the Greek skeptics’ notion of abstaining from belief). We are to practice phenomenology, Husserl proposed, by “bracketing” the question of the existence of the natural world around us. We thereby turn our attention, in reflection, to the structure of our own conscious experience. Our first key result is the observation that each act of consciousness is a consciousness of something, that is, intentional, or directed toward something. Consider my visual experience wherein I see a tree across the square. In phenomenological reflection, we need not concern ourselves with whether the tree exists: my experience is of a tree whether or not such a tree exists. However, we do need to concern ourselves with how the object is meant or intended. I see a Eucalyptus tree, not a Yucca tree; I see that object as a Eucalyptus, with a certain shape, with bark stripping off, etc. Thus, bracketing the tree itself, we turn our attention to my experience of the tree, and specifically to the content or meaning in my experience. This tree-as-perceived Husserl calls the noema or noematic sense of the experience.