Experience the Joy of Learning

- Just Great DataBase

- Study Guides

Hiroshima Essays

John Hersey’s writing career was mostly dedicated to writing compositions about important and moving events in history. Because the United States of America is one of the pioneer in both World War I and World War II, the American-born John Hersey saw things firsthand, if not had an easy...

Hiroshima traces the experiences of six people who survived the atomic blast of August 6, 1945 at 8:15 am. The six people vary in age, education, financial status and employment. Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a personnel clerk; Dr. Masakazu Fuji, a physician; Mrs. Hatsuyo Nakamura, a tailor's widow with...

The most significant theme in John Hersey's book "Hiroshima" are the long- term effects of war, confusion about what happened, long term mental and physical scars, short term mental and physical scars, and people being killed. The confusing things after the A-bomb was dropped on Hiroshima where...

Hiroshima is a work of nonfiction that illuminates the terrors of nuclear warfare. The novel begins introducing the six main characters, Reverend Mr. Kiyoshi Tanimoto, Mrs. Hatsuyo Nakamura, Dr. Masakazu Fujii, Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge, Dr. Terufumi Sasaki and Toshiko Sasaki. John Hersey goes on...

John Hersey was born in China on June 17th, 1914. John Hersey wrote the book Hiroshima on August 31, 1946. The book is about six survivors from the bombing of Hiroshima. The survivors was: Mrs. Hatsuy Nakamura, Dr. Terufumi Sasaki, Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge, Toshiko Sasaki, Dr. Masakazu Fujii, and...

I. Manhatten Project (C)before German & Japanese, Pearl Harbor opportunity, Japan already defeat, Hiroshima (70,000), Nagasaki (40,000), “complete destruction” “utter destruction” a. Through many see the bombing as immoral, the atomic bombings actually saved lives of both Japanese and U. S...

Y9 Hiroshima PLP On August 6, 1945, a new step in technological warfare was taken when the first atomic bomb was dropped on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. The impact of the bomb alone killed at least 66,000 people. This was an event that would not soon be forgotten in history. The Americans, who...

Hiroshima - John Hersey Book Report – Natalie Kirby Hiroshima by John Hersey is a collection of biographies from six survivors from the bombing of Hiroshima. John Hersey wrote this book as an essay at first, but then the New York newspaper made a big deal out of it and how good it was. So a few...

Griffin Dangler Shawn Smith Honors American Literature 27 June 2012 The Use of Atomic Weapons On August 6th, 1945, the world was forever changed when the world’s first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan. The attack was made as an attempt to end World War 2, and it succeeded at a...

1 221 words

Alexa Gombert English-Kiernan 10/28/12 Period 1 On August 6, 1945, America was responsible for the death of over 100,000 innocent souls. On this day, an American aircraft dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. This was the first atomic bomb ever used in the history of warfare. In...

The Hiroshima bomb, dropped in (insert year, i forget which) was a deadly atomic bomb that drastically affected the lives of Japanese citizens in both novels and in reality. In the fictional novel, The Street of a Thousand Blossoms, written by Gail Tsukiyama, the author portrays a very accurate...

1 013 words

In the book Hiroshima by John Hersey, six characters were shown as survivors during the Hiroshima bomb in 1945. The highlighted character given was Dr. Masakazu Fuiji. Out of the six characters that were chosen by Hersey, Dr. Fuiji was one of two scientists, but may have been the most affected or...

John Hersey's journalist narrative, Hiroshima focuses on the detonation of the atomic bomb, Little Boy, that dropped on the city of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Although over one hundred thousand people died in the dropping of the bomb, there were also several survivors. John Hersey travelled...

? The setting of a story can help show the progress of a character. The setting may also be the reason the main character(s) act a certain way. In the novel Hiroshima by John Hersey he describes the life of six different individuals who were effected by the atomic bomb in 1945. The setting of the...

?Final Seminar Chapter 2: The Fire, closely follows the story of the 6 survivors or hibakusha, immediately after the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Each individual struggles to find a place of refuge amongst the chaos as spot fires cover the entire city. There is an emphasis on the...

1 173 words

For the book you are reading, write a paragraph of five to six sentences summarizing what you have read so far. What are your predictions about the story? Use proper spelling and grammar. What I have read so far in my book is that after the explosion, three of the main characters got very ill do...

?Deliver a tutorial presentation on the following statement to other students about Module B: Texts and Ways of Thinking, Elective 1: After the Bomb. Texts emerge from, respond to, critique, and shape our understanding of ways of thinking during a particular historical period, however valuing of...

1 607 words

Hiroshima Pearl Harbour was one of the most terrible acts in history. December 7, 1941 Japan bombed a naval base in Hawaii that was called Pearl Harbor. After this incident the U. S. declared decided to declare war on Japan. After a number of years in battle the U. S. was forced to make a major...

?Student Name Mr. Insert Name History Date Research Paper Outline: The Atomic Bombing of Japan I. Introduction A. Background Information 1. Atomic bombing of Hiroshima occurred on August 6, 1945. a) Estimated 140,000 casualties in the attack and aftermath b) Nuclear weapon named “Little Boy” 2...

Hiroshima: Necessary Warnings Bill Eckley HIST560 4026624 “The final decision of where and when to use the atomic bomb was up to me. Let there be no mistake about it. I regarded the bomb as a military weapon and never had any doubt that it should be used. ”1 –President Harry S. Truman By the...

2 578 words

The human mind cannot comprehend the split-second deaths of 100 000 people when the atomic bomb hit the people of Japan in August, 1945. However this event, which has changed the world forever, can be relived through the lives of six survivors in John Hersey's Hiroshima. Expository texts such...

1 154 words

At 8:15, Japanese time, August 6, 1945 the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. About a hundred thousand people were killed by the inhumane act of those Americans. John Hersey tells the story of six lucky survivors: Miss Toshinki Sasaki, Dr. Masakazu Fuji, Mrs. Hatsuyo Nakamura, Father Wilhelm...

There is fundamental relationship between literature and society. In fact, literature does not exist without society. Indian writing in English has travelled a long journey and is now fully matured. The writers of the Indian diaspora have been centerstage in the last decades. The critique of their...

1 286 words

“Do not work primarily for money; do your duty to patients first and let the money follow; our life is short, we don't live twice; the whirlwind will pick up the leaves and spin them, but then it will drop them and they will form a pile.” — Page 78 — “There, in the tin factory, in the first moment...

Ionizing radiation is normally utilized in our day-to-day lives in little sums e.g. X raies. However, radiation exposure consequences in harmful effects on Deoxyribonucleic acid construction, taking to establish alterations ( oxidization, alkylation ) , cross-link formation or bulky lesions...

2 043 words

About all chest malignant neoplastic disease patients receive radiation therapy after undergoing chest preservation or mastectomy. The benefits of radiation therapy on long term endurance may non basically be free of complications. Patients may hold a broad scope of normal tissue reactions, and...

3 745 words

Gorman timely presents the inquiry “Do historiographers as historiographers have an ethical duty. and if so to whom? ” in his essay Historians and their Duties particularly in an epoch which has seen the usage of history as a manner to foster political docket. invent or falsify historical fact to...

It was the forenoon of Aug 6 1945. It was a really beautiful rose-colored sky. You heard the birds chirping and yet it was so peaceable and unagitated. All of a sudden there was a thump. Then all of a sudden everything went rather and nil was left of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Then three yearss...

1 123 words

The period in history normally considered to hold begun with the first usage of the atomic bomb ( 1945 ) . It is characterized by atomic energy as a military. industrial. and sociopolitical factor. Besides called atomic age. The Nuclear Age Began When The US Detonated The First Atomic BombOn June...

Introduction:The cold war originated from the difference between the Soviet Union and the United States of America over Poland. The Americans accused the Russians of go againsting the Yalta understanding that was signed between the allied powers and the Soviet Union. The cold war was more of an...

1 802 words

Skip to Main Content of WWII

The legacy of john hersey’s “hiroshima”.

Seventy-five years ago, journalist John Hersey’s article “Hiroshima” forever changed how Americans viewed the atomic attack on Japan.

On August 31, 1946, the editors of The New Yorker announced that the most recent edition “will be devoted entirely to just one article on the almost complete obliteration of a city by one atomic bomb.” Though President Harry S. Truman had ordered the use of two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki a year earlier, the staff at The New Yorker believed that “few of us have yet comprehended the all but incredible destructive power of this weapon, and that everyone might well take time to consider the terrible implications of its use.”

Theirs was a weighty introduction to wartime reporter John Hersey’s four-chapter account of the wreckage of the atomic bomb, but such a warning was necessary for the stories of human suffering The New Yorker ’s readers would be exposed to.

Hersey was certainly not the first journalist to report on the aftermath of the bombs. Stories and newsreels provided details of the attacks: the numbers wounded and dead, the staggering estimated costs—numerically and culturally—of property lost, and some of the visual horrors. But Hersey’s account focused on the human toll of the bombs and the individual stories of six survivors of the nuclear attack on Hiroshima rather than statistics.

View of Hiroshima after the bombing, courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Hersey was both a respected reporter and a gifted novelist, two occupations that provided him with the skills and compassion necessary to write his extensive essay on Hiroshima. Born in Tientsin, China in 1914 to missionary parents, Hersey later returned to the states and graduated from Yale University in 1936. Shortly after, he began a career as a foreign correspondent for Time and Life magazines and covered current events in Asia, Italy, and the Soviet Union from 1937 to 1946. Hersey won the Pulitzer Prize for his novel A Bell For Adano (a story of the Allied occupation of a town in Sicily) in 1944, and his talents for fiction inspired his later nonfiction writing. He spent three weeks in May of 1946 on assignment for The New Yorker interviewing survivors of the atomic attacks and returned home where he began to write what would become “Hiroshima.”

Hersey was determined to present a real and raw image of the impact of the bomb to American readers. They could not depend on censored materials from the US Occupying Force in Japan to accurately present the wreckage of the atomic blast. Hersey’s graphic and gut-wrenching descriptions of the misery he encountered in Hiroshima offered what officials could not: the human cost of the bomb. He wanted the story of the victims he interviewed to speak for themselves, and to reconstruct in dramatic yet relatable detail their experiences.

Portrait of John Hersey by Carl Van Vechten from 1958, courtesy of The Library of Congress.

Hersey organized his article around six survivors he met in Hiroshima. These were “ordinary” Japanese with families, friends, and jobs just like Americans. Miss Toshiko Sasaki was a 20 year old former clerk whose leg had been severely damaged by fallen debris during the attack and she was forced to wait for days for medical treatment. Kiyoshi Tanimoto was a pastor of a Methodist Church who appeared to be suffering from “radiation sickness,” a plight that befell another of Hersey’s interviewees, German-born Jesuit Priest Father Wilhelm Kleinsorge. Mrs. Hatsuyo Nakamura’s husband died while serving with the Japanese army, and she struggled to rebuild her life with her young children after the attack. Finally, two doctors—Masakazu Fujii and Terufumi Sasaki—were barely harmed but witnessed the death and destruction around them as they tended to the victims.

Each of the essay’s four chapters delves into the experiences of the six individuals before, during, and after the bombing, but it’s Hersey’s unembellished language that makes his writing so haunting. Unvarnished descriptions of “pus oozing” from wounds and the stench of rotting flesh are found throughout all of the survivors’ stories. Mr. Tanimoto recounted his search for victims and encountering several naked men and women with “great burns…yellow at first, then red and swollen with skin sloughed off and finally in the evening suppurated and smelly.” Tanimoto—for all of the chaos that surrounded him—recalled that “the silence in the grove by the river, where hundreds of gruesomely wounded suffered together, was one of the most dreadful and awesome phenomena of his whole experience.”

“The hurt ones were quiet; no one wept, much less screamed in pain; no one complained; none of the many who died did so noisily; not even the children cried; very few people even spoke.”

John Hershey

At the same time, Hersey also describes the prevalence of radiation sickness amongst the victims. Many who had suffered no physical injuries, including Mrs. Nakamura, reported feeling nauseated long after the attack. Father Kleinsorge “complained that the bomb had upset his digestion and given him abdominal pains” and his white blood count was elevated to seven times the normal level while he consistently ran a 104 degree temperature. Doctors encountered many instances of what would become known as radiation poisoning but often assured their patients that they would “be out of the hospital in two weeks.” Meanwhile, they told families, “All these people will die—you’ll see. They go along for a couple of weeks and then they die.”

Hersey’s interviews also highlighted the inconceivable impact of the nuclear blast. Americans may have believed that such a powerful explosion would be deafening, but the interviewees offered a different take. More than a sound, most of the interviewees described blinding light at the moment of the attack. Dr. Terufumi Sasaki remembered the light of the bomb “reflected, like a gigantic photographic flash,” through an open window while Father Kleinsorge later realized that the “terrible flash” had “reminded him of something he had read as a boy about a large meteor colliding with the earth.” Hersey’s title of the first chapter is, in fact, “A Noiseless Flash.”

The attack also left a bizarre mark on the landscape. While buildings were reduced to rubble, the power of the bomb “had not only left the underground organs of plants intact; it had stimulated them.” Miss Sasaki was surprised upon her return to Hiroshima in September by the “blanket of fresh, vivid, lush, optimistic green” plants that grew over the destruction and the day lilies that blossomed from the heaps of debris. Others remembered eating pumpkins and potatoes that were perfectly roasted in the ground by the fantastic heat and energy of the bomb.

With its raw descriptions of the terror and destruction faced by the residents of Hiroshima, Hersey’s article broke records for The New Yorker and became the first human account of the attack for most Americans. All 300,000 editions of The New Yorker sold out almost immediately. The success of the article resulted in a reprinted book edition in November that continues to be read by many around the world. Meanwhile, Hersey remained relatively removed from his work, refusing most interviews on the book and choosing instead to let the work speak for itself.

Decades later, his six interviewees remain a human connection to the attacks and the deep, philosophical questions they raised. “A hundred thousand people were killed by the atomic bomb, and these six were among the survivors,” Hersey said, leaving them to “still wonder why they lived when so many others died,” or “too busy or too weary or too badly hurt to care that they were the objects of the first great experiment in the use of the atomic power which…no country except the United States, with its industrial know-how, its willingness to throw two billion gold dollars into an important wartime gamble, could possibly have developed.”

This article is part of a series commemorating the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II made possible by the Department of Defense.

Stephanie Hinnershitz, PhD

Stephanie Hinnershitz is a historian of twentieth century US history with a focus on the Home Front and civil-military relations during World War II.

From Hiroshima to Human Extinction: Norman Cousins and the Atomic Age

In 1945 the American intellectual, Norman Cousins, was one of the first to raise terrifying questions for humanity about the successful splitting of the atom.

The Most Fearsome Sight: The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima

On the morning of August 6, 1945, the American B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped an atomic bomb on the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

FALLOUT: The Hiroshima Cover-Up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World with Author Lesley Blume

This presentation of FALLOUT , which premiered on the Museum’s Facebook page, recounts how John Hersey got the story that no other journalist could—and how he subsequently played a role in ensuring that no nuclear attack has happened since, possibly saving millions of lives.

Should Atomic Bombs Never Be Used as a Weapon?

From the Manhattan Project to Hiroshima and atomic diplomacy.

Explore Further

Our War Too: Women's History Symposium

The symposium, which took place from February 29 to March 1, 2024, featured topics expanding upon the Museum’s special exhibit, Our War Too: Women in Service .

Unaccounted For No More: Sgt. Harold Hammett

WWII US Marine Corps Sergeant Harold Hammett, fallen on Tarawa in 1943, is finally laid to rest in the family plot after 80 years.

The Second Great Fire of London: 'A Dreadful Masterpiece'

In this column, journalist Ernie Pyle describes the bombing of London in late December 1940 as “the most hateful, most beautiful single scene” he had ever witnessed as the city was “stabbed with fire” by the German Luftwaffe .

What Happened to Lieutenant Curtis R. Biddick?

V for Victory: A Sign of Resistance

Created by a Belgian politician and broadcaster fleeing Nazi persecution, the V for Victory symbol became one of the most enduring signs of the war.

The Origins of International Holocaust Remembrance Day

The commemorations on January 27 remind us that the Holocaust was the result of step-by-step decisions by individuals that led to the largest genocide in the history of mankind in a wave of antisemitism, intolerance, and hatred.

The 'Bloody 100th' Bomb Group

The Eighth Air Force’s hard luck unit was filled with colorful personalities who made the unit one of the most storied of World War II.

Meet the Author: James B. Conroy, 'The Devils Will Get No Rest'

Conroy discussed his unique perspective of the Anglo-American clash over military strategy in January 1943 that ultimately produced the Allied plan for victory in World War II.

John Hersey

Everything you need for every book you read..

Welcome to the LitCharts study guide on John Hersey's Hiroshima . Created by the original team behind SparkNotes, LitCharts are the world's best literature guides.

Hiroshima: Introduction

Hiroshima: plot summary, hiroshima: detailed summary & analysis, hiroshima: themes, hiroshima: quotes, hiroshima: characters, hiroshima: symbols, hiroshima: theme wheel, brief biography of john hersey.

Historical Context of Hiroshima

Other books related to hiroshima.

- Full Title: Hiroshima

- When Written: The first chapters were written in the first half of 1946; Hersey later added additional chapters, including one written forty years after the bombing

- Where Written: New York City and the Solomon Islands (in the Pacific)

- When Published: The first portion of the book first appeared as the entirety of the August 31, 1946 issue of The New Yorker , and it later appeared as a full-length book in November 1946. In 1985, The New Yorker published another full-length Hersey piece on the aftermath of the bombing, which was later included in editions of Hiroshima .

- Literary Period: The book has been considered one of the founding texts of New Journalism, the journalistic technique of depicting nonfiction events with a narrative literary style. However, Hersey later said that he despised New Journalism, so he probably wouldn’t appreciate being remembered as its godfather!

- Genre: nonfiction

- Setting: Hiroshima, Japan, and surrounding towns

- Climax: None—the book follows characters through many stages in their lives, so that action never really “rises” or “falls”

- Antagonist: The United States, nuclear technology, or the indifferent Japanese state could all be considered antagonists

- Point of View: Third person omniscient (moving back and forth between the six main characters)

Extra Credit for Hiroshima

How to get a job by being a jerk. John Hersey was famous, and notorious, for his blunt, outspoken manner. As a young man, he wrote a long article on how horrible Time magazine’s journalism had become. Time ’s editors read the article—and promptly hired Hersey to make the magazine better!

The sincerest form of flattery. John Hersey was a highly-respected journalist, but he had his share of detractors. In 1988, he gained some new enemies after he was found to have plagiarized large chunks of Laurence Bergreen’s biography of the writer James Agee for his own article on Agee in The New Yorker . Hersey was reportedly humiliated by the discovery, and he publicly apologized to Bergreen. But later, a reader discovered that Hersey had plagiarized other articles, too!

- Nieman Foundation

- Fellowships

To promote and elevate the standards of journalism

Nieman News

Back to News

From the Editor

August 6, 2021, collected reflections on john hersey's "hiroshima", on the 76th anniversary of the bombing of hiroshima, hersey's book still teaches about humanity and the craft of writing.

By Jacqui Banaszynski

Tagged with

The first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, on Aug. 6, 1945. LitHub.com

One of the ways I remember is with an annual read of John Hersey’s short book “Hiroshima.” It has never been knocked from its place at the top of my list of Things Every Journalist Should Study. Today, to enrich that education, I hunted back through previous Storyboard posts that explore what makes the book endure:

- Journalist and teacher Peter Richmond took a senior seminar with Hersey at Yale. In 2013, he wrote a semi-confessional essay about having to lose his ego to find his writing voice. It includes the six takeaways from Hersey’s class that stayed with him.

- Former Storyboard editor Constance Hale included “Hiroshima” as one of the pieces of writing she has learned most from in her career.

- Mark Kramer, founding director of the Power of Narrative conference, cited a passage from “Hiroshima” in a talk on narrative voice at this year’s virtual gathering.

- Last year, on the 75th anniversary, I reflected on how the teaching power of Hersey’s book grows for me over time, and that every reading offers new insights. I cribbed, with credit, from those who had written about “Hiroshima” before, but also found myself studying how Hersey used individual names to build the humanity and universality of his story.

If you don’t have a well-thumbed copy of your own, it’s time. Or simply Google references to Hersey and “Hiroshima” to read how how others are still using Hersey’s iconiic work to uncover deeper and deeper truths about that horrible reality.

Writing Lessons From John Hersey’s “Hiroshima”

“The battle line between good and evil runs through the heart of every man,” Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn once wrote. Nowhere do we witness this eternal struggle more movingly than in Hiroshima , John Hersey’s unforgettable account of that fateful day on August 6th, 1945 when the atomic bomb was dropped. Hailed as the “most celebrated piece of journalism to come out of WWII,” Hiroshima follows six survivors as they navigate the devastating aftermath of nuclear war. Obliterating 100,000 lives in an infernal blast that will reverberate through the centuries as human history’s “most unspeakable crime,” the atom bomb is an unsettling reminder that the human heart is neither wholly good nor evil.

Hiroshima stands as a masterpiece of reporting for its ability to humanize the Japanese people at a time when words were weaponized as instruments of war. Rather than reduce them to a one-dimensional demonized “enemy,” Hersey revealed Dr. Masakazu Fujii, Dr. Terufumi Sasaki, Father Wilhem Kliensorge, Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto, Toshiko Sasaki, and Hatsuyo Nakamura as ordinary people: people who were staring out windows and sitting at their desks just as they had hundreds of times when their lives were forever shattered by an unprecedented act of war.

While some reporters marveled at man’s ability to harness the cataclysmic power of atomic energy ( New York Times staff member William Laurence, the only journalist to witness the terrible technology first hand, wrote with wonder, “It was no longer smoke, or dust, or even a cloud of fire. It was a living thing, a new species of being, born right before our incredulous eyes.” ), others focused on calculating the staggering number of lives lost or capturing the wasteland left behind ( New York Herald Tribune’s Homer Bigart observed when he visited Hiroshima in September 1945 that “across the river there was only flat, appalling desolation, the starkness accentuated by bare, blackened tree trunks and the occasional shell of a reinforced concrete building.” )

Hersey took a different approach. Hiroshima , originally published as a 30,000 word feature in the August 1946 issue of the New Yorker , is now considered a landmark of new journalism, a style of reporting that blended the impartial facts of traditional journalism with the pacing and storytelling of a novel. By funneling the harrowing events of that historic day through the soul-expanding subjectivity of stories instead of the heartless objectivity of mere numbers, Hersey was able to demolish the barricade between ally and enemy so often erected by war. The result is a compassionate document that — as one critic put it — “stirs the conscience” of the soul.

Hiroshima’s first line is perhaps one of journalism’s best-known:

“At exactly fifteen minutes past eight in the morning, on August 6, 1945, Japanese time, at the moment when the atomic bomb flashed above Hiroshima, Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the personnel department of the East Asia Tin Works, had just sat down at her place in the plant office and was turning her head to speak to the girl at the next desk.”

In his instructive new book The Art of X-Ray Reading: How the Secrets of 25 Great Works of Literature Will Improve Your Writing , journalist and Poynter Institute senior scholar Roy Peter Clark seeks to break down this stellar first sentence so we can better understand how it works. A curator of spellbinding sentences and lover of lively prose, Clark contends the secret to writing well is hidden in literature’s masterworks or — as Matthew Arnold might say — in “the best that’s been thought and said” in the world. If we want to be compelling writers, we just have to crack the code. “Cracking the code” means paying attention to how an author mesmerizes us with his words. Like Hemingway, does he seduce us to turn the page by revealing less information than he withholds ? Or like Plath, does he create a sense of unity by repeating an overarching motif or symbol ? In much the same way authors of that endlessly edifying guide to close-reading How to Read a Book revere books as absent teachers , Clark believes literature has a wealth of writing wisdom to offer.

So how, Clark wonders, does Hersey manage to captivate us from Hiroshima’s very first line?

The sentence itself is rather simple: 63 words, 32 of which are only 1-syllable. There is no flamboyant expression, no elaborate sentence structure, no theatrical melodrama. Even the subject matter is mundane: other than the offhand reference to the bomb “flashing above Hiroshima,” the sentence focuses on the ordinary and everyday, particularly one Miss Toshiko Sasaki, who’s doing the most uninteresting thing you could possibly conceive: turning her head to chat with a co-worker. So why is this one of the most riveting first lines in all of literature? For Clark, the secret is pacing:

“This feels like a most unconventional way to begin a story. In spite of the importance of time to the telling of all narratives, we rarely see this degree of temporal specificity in a first line. The word exactly is not a modifier but an intensifier. We then learn the minutes, the hour ante meridiem, the month, day, year, and time zone. That’s seven discrete time metrics before a verb. The rhetorical effect of such specificity is that of a historical marker. Something world-changing is about to happen (a meteor struck the earth; a volcano exploded; a jet plane flew into the Pentagon). Chaucer’s springtime at the beginning of The Canterbury Tales is generic and cyclical. In Hiroshima we are about to meet a group of pilgrims who share an experience that is triggered at a specific moment in time.

In a way, time is also about to stand still. Clocks and watches, damaged by the atomic blast, stopped at the moment of destruction. This symbol of the stopped watch in relation to Hiroshima is repeated as late as 2014 in the updated version of the movie Godzilla. The original was made in Japan in 1954 and is widely recognized as a science-fiction, monster-movie allegory of the consequences of nuclear destruction. In the updated version, Japanese actor Ken Watanabe carries around the talisman of a pocket watch owned by his grandfather, killed at Hiroshima. The time is frozen at eight fifteen.”

As writers, what can we take away from this unforgettable first sentence? Just as Hersey uses temporal specificity to stop time and signal that something history-making is about to happen, we can decelerate — or “freeze frame” — our narrative to amplify drama and build suspense:

Writing Lesson #1

“Stories are about time in motion. But there are moments when time seems to stop, at least in narrative terms: when the atom bomb drops, when Kennedy is shot, when the Challenger explodes. As a writer, you can mark that moment when time stands still. Freeze a movie into a still frame.”

Hiroshima is not only a paragon of pacing — it’s a matchless example of understatement. “If ever there was a subject calculated to make a writer overwrought and a piece overwritten, it was the bombing of Hiroshima,” observed New Yorker journalist and political commentator Hendrik Hertzberg. When a story is as momentous as Pearl Harbor or September 11th, it seems made for the newspapers. There’s conflict, there’s catastrophe, there’s lives lost. But though it’s tempting to hyperbolize, a good writer will restrain himself. What makes Hiroshima so powerful is the way Hersey lets the material speak for itself. Instead of indulging in melodrama — say, by sensationalizing the carnage or heavy-handedly accentuating the scene’s pathos — Hersey writes in a matter-of-fact style, employing only plain words all the while maintaining a dispassionate, journalistic tone. As Clark explains, when a story is “big,” the key is to write “small”:

“In bringing us finally to the main part of the sentence, the author puts into practice two reliable rhetorical strategies, one from ancient Greece, the other from the American newsroom. The name for the first is litotes, or understatement- the opposite of hyperbole. While an unwise writer might overwhelm us with the visceral imagery of destruction, Hersey chooses to introduce a most common scene of daily life: one office worker turning to another, allowing the drama to unfold. In the face of astonishing content, step back a bit. Don’t call undue attention to the tricks of the writer.

A related strategy comes from an old bit of newsroom wisdom: “The bigger the smaller.” Nowhere was this strategy used more than in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on New York City on September 11th. Faced with almost apocalyptic physical destruction and the loss of nearly three thousand lives, writers such as Jim Dwyer of the New York Times looked for ways to tell a story that seemed from its inception “too big.” Dwyer chose to highlight physical objects with stories hiding inside of them: a window washer’s squeegee used to help a group break out of a stalled elevator in one of the Twin Towers; a family photo discovered in the rubble; a paper cup used by an escaping stranger to give water to another.

The author of Hiroshima offers readers something akin to writing teacher Robert McKee’s “inciting incident.” This is the moment that kicks off the energy of the story, the instant when normal life is transformed into story life. All the characters described in the first paragraph are experiencing a version of normal, everyday life- given the context of an ongoing world war- but whatever their expectations, they were changed forever at the exact moment the atomic bomb flashed over Hiroshima.”

Writing Lesson #2

“Given the exact nature of the news and the death toll, the author’s narrative feels somehow underwritten, in a good way. There are no elaborate metaphors. The author keeps the focus on the cast of characters and not on his own feelings or emotions. In general, this is a good rhetorical strategy. The more powerful or consequential the content, the more the author should “get out of the way.” This does not mean that craft must be set aside. Instead, it means craft must be used to create a feeling of understatement.”

Share this:

4 thoughts on “ writing lessons from john hersey’s “hiroshima” ”.

- Pingback: Writing Lessons From Sylvia Plath’s “The Bell Jar” – asia lenae

- Pingback: Writing Lessons from Ernest Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms” – asia lenae

- Pingback: Why Van Gogh Painted Irises & Night Skies: Art as a Grand Gesture of Generosity – asia lenae

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from asia lenae

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

'Fallout' Tells The Story Of The Journalist Who Exposed The 'Hiroshima Cover-Up'

Dave Davies

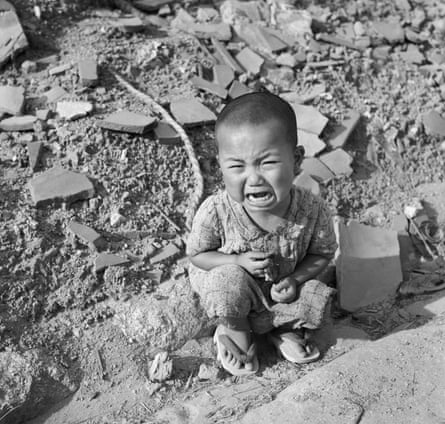

In 1945, an Allied war correspondent stands in the ruins of Hiroshima, weeks after an atomic bomb leveled the Japanese city. AP Photo hide caption

In 1945, an Allied war correspondent stands in the ruins of Hiroshima, weeks after an atomic bomb leveled the Japanese city.

When the U.S military dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, the American government portrayed the weapons as equivalent to large conventional bombs — and dismissed Japanese reports of radiation sickness as propaganda.

Military censors restricted access to Hiroshima, but a young journalist named John Hersey managed to get there and write a devastating account of the death, destruction and radiation poisoning he encountered. Author Lesley M.M. Blume tells Hersey's story in her book, Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed it to the World.

She writes that when Hersey, who had covered the war in Europe, arrived in Hiroshima to report on the aftereffects of the bomb a year later, the city was "still just a sort of smoldering wreck."

"Hersey had seen everything from that point, from combat to concentration camps," Blume says. "But he later said that nothing prepared him for what he saw in Hiroshima."

After Hiroshima Bombing, Survivors Sorted Through The Horror

Hersey wrote a 30,000-word essay , telling the story of the bombing and its aftermath from the perspective of six survivors. The article, which was published in its entirety by The New Yorker , was fundamental in challenging the government's narrative of nuclear bombs as conventional weapons.

"It helped create what many experts in the nuclear fields called the 'nuclear taboo,' " Blume says of Hersey's essay. "The world did not know the truth about what nuclear warfare really looks like on the receiving end, or did not really understand the full nature of these then experimental weapons, until John Hersey got into Hiroshima and reported it to the world."

Interview Highlights

On what Americans knew about the nature of nuclear weapons in 1945

Americans didn't know about the bomb — period — until it was detonated over Hiroshima. The Manhattan Project was cloaked in enormous secrecy, even though tens of thousands of people were working on it. ... When President Harry Truman announced that America had detonated the world's first atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima, he was announcing not only a new weapon, but the fact that we had entered into the Atomic Age, and Americans had no idea about the nature of these then-experimental weapons — namely, that these are weapons that continue to kill long after detonation. It would take quite a bit of time and reporting to bring that out.

Everybody who heard the announcement [from Truman] knew that they were dealing with something totally unprecedented, not just in the war, but in the history of human warfare. What was not stated was the fact that this bomb had radiological qualities, [that] blast survivors on the ground would die in an agonizing way for the days and the weeks and months and years that followed.

On how military generals focused on physical devastation when they testified before Congress about the effects of the atomic bomb

In the immediate weeks, very little [was said.] A lot of it was really painted in landscape devastation. Landscape photographs were released to newspapers showing the decimation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. There were rubble pictures, and also obviously people are seeing the mushroom cloud photos taken from the bombers themselves or from recon missions. But in terms of the radiation — even in Truman's announcement of the bomb — he's painting the bombs in conventional terms. He says these bombs are the equivalent to 20,000 tons of TNT. And so Americans, they know that it's a mega-weapon, but they don't understand the full nature of the weapons, the radiological effects are not in any way highlighted to the American public, and in the meantime, the U.S. military is scrambling to find out how the radiation of the bombs is affecting the physical landscape, how it's affecting human beings, because they're about to send tens of thousands occupation troops into Japan.

On America's PR campaign and cover-up of the radiation aftermath

[The U.S. military] created a PR campaign to really combat the notion that the U.S. had decimated these populations with a really destructive radiological weapon. Leslie Groves [who directed the Manhattan Project] and Robert Oppenheimer [who directed the Manhattan Project's laboratory at Los Alamos, N.M.] themselves went to the Trinity site of testing [in New Mexico] and brought a junket of reporters so they could show off the area. And they said that there was no residual radiation whatsoever, and that therefore, any news that was filtering over from Japan were "Tokyo tales." So right away they went into overdrive to contain that narrative. ...

The American officials were saying, for the most part, these are the defeated Japanese trying to create international sympathy, to create better terms for themselves and the occupation — ignore them.

On how reporters had limited access to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and their reports were often censored

In the early days of the occupation, there obviously would have been enormous interest in trying to get to Hiroshima and Nagasaki ... but as the occupation really took hold and became increasingly organized, the reports were intercepted. The last one that came out of Nagasaki was intercepted and lost. There was almost no point in trying to get down there because the obstacles that were put up for reporters were so tremendous by the military censors. ... I can't overstate how restricted your movements were as a reporter, as part of the occupation press corps. ... You could not get around, you could not eat. You couldn't do anything without the permission of the Army. ... The control was near total.

On concerning Japanese reports about "Disease X" affecting blast survivors

Hiroshima Atomic Bombing Raising New Questions 75 Years Later

As news started to filter over from Japanese reports about what it was like on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the aftermath, wire reports started picking up really disturbing information about the totality of the decimation and this sinister ... "Disease X" that was ravaging blast survivors. So this news was starting to trickle over early in August of 1945 to Americans.

And so the U.S. realized that not only were they going to have to really try to study very quickly how radioactive the atomic cities might have been, as they were bringing in their own occupation troops. But they [also] realized that they had a potential PR disaster on their hands, because the U.S. had just won this horribly hard-earned military victory, and were on the moral high ground, they felt, in defeating the Axis powers. And they had avenged Pearl Harbor. They had avenged Japanese atrocities throughout the Pacific theater in Asia. But then reports that they had decimated a largely civilian population in this excruciating way with an experimental weapon — it was concerning because it might have deprived the U.S. government of [its] moral high ground.

On how Hiroshima and Nagasaki were seen as souvenir sites for American military

An Atomic Bomb Survivor On Her Journey From Revenge To Peace

Hiroshima was seen as a site of just enormous victory for these guys. And a lot of them would go even to ground zero of the bombings in Hiroshima. ... They saw it as a souvenir site. It's essentially a graveyard. There are still remains that are being dug up in Hiroshima and Nagasaki today. But many of them kind of pillaged the ruins to grab a souvenir to bring home. It was the ultimate victory souvenir. So whether it's a broken teacup to use as an ashtray or what have you, they went and they took their equivalent of selfies at ground zero. At one point in Nagasaki, Marines cleared a football field-sized amount of space in the ruins and they had what they called the "Atomic Bowl," which was a New Year's Day football game where they had conscripted Japanese women as cheerleaders. It was an astonishing scene in both cities. They were seen as sites of a victory. And most of the "occupationaires" were totally unrepentant about what had gone down there.

On Hersey getting a firsthand account from the Rev. Kiyoshi Tanimoto of what the moment of the bombing was like

Rev. Tanimoto, at the moment of the bombing, was slightly outside of the city. He had been transporting some goods to the outskirts of the city, and he was up on a hill. And so therefore, he had a bird's-eye view of what happened. He fell to the ground when the actual bomb went off. But then when he got up, he saw that the city had been enveloped in flames and black clouds. And ... he saw a procession of survivors starting to straggle out of the city. He was just absolutely horrified by what he had seen and baffled, too, because usually an attack on this level would have been perpetrated by a fleet of bombers. But this was just a single flash.

And the survivors who were making their way out of the city and who would not survive for long, I mean, most of them were naked. Some of them had flesh hanging from their bodies. He saw just unspeakable sights as he ran into the city because he had a wife and an infant daughter. He wanted to find his parishioners. The closer he got towards the detonation, the worse the scene was. The ground was just littered with scalded bodies and people who were trying to drag themselves out of the ruins and wouldn't make it. There were walls of fire that were consuming the areas. The enormous firestorm was starting to consume the city. He, at one point, was picked up by a whirlwind, because winds had been unleashed throughout the city, and ... he was lifted up in a red-hot whirlwind. ... It was just unbelievable that he survived not only the initial blast, but then [headed] into [the] city center and the extreme trauma of having witnessed what he witnessed. It's remarkable that he came out of it alive.

On how Hersey's reporting changed the world's perception of nuclear weapons

The Japanese could not, for years, tell the world what it had been like to be on the receiving end of nuclear warfare, because they were under such dire press restrictions by the occupation forces. And so it took John Hersey's reporting to show the world what the true aftermath and the true experience of nuclear warfare looks like. ... It changed overnight for many people, what was described by one of Hersey's contemporaries as the "Fourth of July feeling" about Hiroshima. There was a lot of dark humor about the bombings in Hiroshima. [The essay] just really imbued the event with a sobriety that really hadn't been there before. And also it just completely deprived the U.S. government of the ability to be able to paint nuclear bombs as conventional weapons. ... [Hersey] himself later said the thing that has kept the world safe from another nuclear attack since 1945 has been the memory of what happened in Hiroshima. And he certainly created a cornerstone of that memory.

Sam Briger and Seth Kelley produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the Web.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Hiroshima by John Hersey – survivors' stories carry weight of history

The New Yorker’s 1946 special report on the aftermath of the first atomic bomb attack is clear-eyed and dispassionate, and all the more powerful for that

- Guardian Witness: which books do you love to share?

- Read more in our ‘A book to share’ series

A quiet hysteria buzzed through Hiroshima in the summer of 1945. The Americans had been firebombing Japan for weeks, and it was one of only two key cities they had not yet hit. B-29 Superfortresses were stationed north-east of Hiroshima and had been flying ominously overhead – locals called these planes B-san or Mr B. “The frequency of the warnings and the continued abstinence of Mr B with respect to Hiroshima had made its citizens jittery,” wrote the New Yorker’s John Hersey. “A rumour was going around that the Americans were saving something special for the city.”

And then it came. At 8.15am on 6 August, Little Boy was dropped over Hiroshima. More than 100,000 people died, instantly or in the atomic bomb’s aftermath. “Such clouds had risen that there was a sort of twilight around … The day grew darker and darker,” Hersey wrote. A different sort of darkness would linger in Hiroshima.

Western press reports on the attack mainly covered the gruesome statistics; missing were the stories of the survivors. That autumn, New Yorker editor William Shawn decided the magazine had to cover the story. “He wants to wake people up and says we are the people with a chance to do it, and probably the only people to do it,” Harold Ross, the magazine’s founder, wrote to EB White . In May 1946 they sent the war correspondent John Hersey, who was in Shanghai, to see what he would find.

The result was Hiroshima, a 30,000-word piece published in a single issue in August 1946 and later reprinted as a book. Over the years, it has been recommended to me several times, often by other writers, as a canonical example of New Journalism . I duly added it to my list of books to read, but another title always seemed to make its way to the top of the pile beside my bed. In 2015, however, I received a slender edition of Hiroshima, released by Penguin on the 70th anniversary of the attack. When I look back on a year of reading, it is this book I would recommend without hesitation to anyone saddened and distressed by news from Paris, Beirut, San Bernardino, Syria. The subject is utterly, horribly contemporary.

Hersey tells the intertwined stories of six people in Hiroshima in the hours and weeks after the attack: a young surgeon; a pastor; a tailor’s widow with three children; a prosperous doctor; a female clerk at a tin factory; and a German priest. Its tick-tock approach gives it a Law and Order quality, as it switches its focus between the six subjects. But it is so much more: a chronicle of life amid the wreckage, with nary a word of hyperbole – a book that seems, at the close of 2015, more relevant than ever. It never promises an explanation for war, it never preaches. It eschews statistics in favour of story.

In fact, Hersey’s writing is so straightforward as to seem plain, but he often uses just the right word, or a simple but exquisite phrase, or a shattering detail, and his sentences are unmediated by a writerly presence. In one chapter, the pastor Mr Tanimoto was looking for a boat that would help him ferry the gravely injured across the river to safety. He came upon a punt on the shore. “It was an awful tableau – five dead men, nearly naked, badly burned, who must have expired more or less all at once, for they were in attitudes which suggested that they had been working together to push the boat down into the river.” Mr Tanimoto knew what he must do: he dutifully pulled the bodies away from the boat, but was so disturbed by “preventing them, he momentarily felt, from going on their ghostly way – that he said out loud, ‘Please forgive me for taking this boat. I must use it for others, who are alive.’”

Hiroshima is stitched together with many moments like this. Early on, we meet the tailor’s widow shortly after the mysterious explosion: “As Mrs Nakamura stood watching her neighbour, everything flashed whiter than any white she had ever seen … the reflex of a mother set her in motion towards her children. She had taken a single step … when something picked her up and she seemed to fly into the next room, over the raised sleeping platform, pursued by parts of her house.” (The family survived.)

Hersey’s documentary eye captures a full spectrum of feeling – panic, grief, disgust, resilience, hope – often on the same page. The German Jesuit Father Kleinsorge is at Asano Park, on the outskirts of the city, climbing over dead bodies to fill a teapot with fresh water, which he will offer to survivors. Coming back, he finds a group of 20 injured soldiers: “Their faces were wholly burned, their eye sockets were hollow, the fluid from their melted eyes had run down their cheeks.” With a flash of ingenuity, he makes a straw from a piece of grass so the men, whose mouths are swollen and covered in pus and who will probably not live out the night, can drink.

“Since that day, Father Kleinsorge has thought back to how queasy he had once been at the sight of pain … Yet in the park he was so benumbed that immediately after leaving this horrible sight he stopped on a path by one of the pools and discussed with a lightly wounded man whether it would be safe to eat the fat, two-foot carp that floated dead on the surface of the water. They decided, after some consideration, that it would be unwise.”

Hiroshima is filled with evidence of humanity at its worst and best , with stories of generosity, grief and pain. I was sickened by some descriptions, while others were surprising, like when the priests discovered that the pumpkins at the mission had roasted on the vine and made a tasty dinner. I also found myself disheartened that the book had little sense of resolution.

In the months after the attack, Japanese people tried to make sense of what had happened. Some were angry, some detached: “It was a war and we had to expect it,” many said. Others were philosophical: “The crux of the matter is whether total war in its present form is justifiable, even when it serves a just purpose. Does it not have material and spiritual evil as its consequences, which far exceed whatever good might result? When will our moralists give us a clear answer to this question?”

Hersey doesn’t attempt one himself and, notably, he closes with a young boy describing life after the atomic bomb. The boy seems remarkably well adjusted, so much so that it suggests the message that life goes on, that children will grow up and they will get by – one I found difficult to accept, perhaps because I realised that, 70 years later, not much has changed.

In this way, Hiroshima doesn’t seem like a history lesson. It is a raw, very human account of the death, destruction and resilience that, all these decades later, we still witness around the world. And it is also, as Harold Ross put it in 1946, “one hell of a story”.

- A book to share

- Second world war

- History books

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

by John Hersey

Hiroshima essay questions.

How do Hersey's six subjects display different ways of coping with tragedy in the years following the bombing?

In the aftermath of the attack on Hiroshima, the six subjects all lead very different lives that reflect both their personal differences from each other, as well as the varying ways of internalizing a tragic event. Some find that the best way to move forward is to remember what happened, by constantly engaging with victims and working to better their lives. Both Mr. Tanimoto and Father Kleinsorge do this, through fundraising and efforts to spread their faith. Others, like Dr. Sasaki, find that remembering is too painful. Dr. Sasaki moves his practice and tries to change his life after he finds that treating hibakusha is too overwhelming for him. For still others, coping with tragedy involves leading a purely selfish and hedonistic lifestyle; one could argue that Dr. Fujii's life of partying and self-indulgence is a product of the shock of being given a second chance at life. All of these are legitimate ways of reacting to a dramatic disaster such as the bombing.

Why does Hersey not take a more anti-American sentiment in this piece?

Though it employs the strategies of New Journalism and is told like a work of prose, Hiroshima is primarily a factual account that is meant to report the truth as it happened. It is subjective in that it relays the feelings and emotions of its subjects, but it does not take a strong stance against the United States' decision to use the bomb. This is fitting with the widespread Japanese reaction to the tragedy: people were more focused on recovering rather than on hating America, and the general mentality was one of pacifism and reconciliation, not a desire for revenge. Many also understood that they had been fighting a total war, and thus they had to expect any kind of attack. Thus, Hersey's piece is more a general statement against the horrors of war in general, not a condemnation of the individual decisions made in this particular one.

Why is it important to the narrative structure that the subjects' stories converge in Asano Park?

Mr. Tanimoto, Mrs. Nakamura, and Father Kleinsorge all end up in Asano Park in the hours immediately following the bombing. This is significant because it allows readers to see how the subjects relate to each other both as victims and as neighbors, helping each other and leaning on each other whenever necessary. This is true of Asano Park as a whole: it represents the setting where victims from all walks of life converge, stripped of the precious distinctions that social class, occupation, gender, or age would have given them, focused solely on the two very human experiences of grief and survival.

How does faith play a role in the survivors' stories?

In the aftermath of a tragedy, faith can be both an uplifting force and a crushing force: people look to a higher power for comfort and hope, but they also wonder how any god could allow them to suffer like this. For this reason, John Hersey chooses two subjects, Mr. Tanimoto and Father Kleinsorge, who are men of faith. Their experiences, along with Miss Sasaki's later in life, generally support the idea that faith is powerful in a positive way during disaster. Faith drives both Mr. Tanimoto and Father Kleinsorge to selflessly help their neighbors in the immediate hours following the bombing, and later to help the hibakusha in the years to come. Miss Sasaki is initially skeptical, but Father Kleinsorge helps to show her the powerful healing that religion can provide her, and she eventually converts to Catholicism and becomes a nun. Faith is important in all of these people's lives, just as it is important to many people following a disaster or war.

How does Japanese culture color the way survivors cope with the bombing?

There is a prevailing sense of shame and honor in Japanese culture, as pointed out in the experience of Mr. Tanimoto: he thinks it is shameful that he is uninjured while so many others are dead or dying. This means that the Japanese victims of Hiroshima did not make a show of their suffering; instead, they endured their pain in silence and stoically attempted to help others. This cultural norm translated into Japanese people's acceptance of their surrender; they viewed it as a sacrifice they had to tolerate for the sake of peace in the world, rather than a terrible disgrace.

Hiroshima Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Hiroshima is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

why did mr. tanimoto hate miss tanaka’s father?

What was the name of Mr. Tanaka's father. I know this is in chapter three.

Figure of speech of nanking store

Sorry, I'm not sure what you are asking here.

Use details from the text to write two or three sentences describing Mr.Tanimoto. What important aspects of his character can the reader infer from the letter he wrote?

A Methodist who lives in Hiroshima. Plays the role of a physician, helping many victims of the bomb. Later, he becomes a peace activist. He has a daughter named Koko.

Study Guide for Hiroshima

Hiroshima study guide contains a biography of John Hersey, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Hiroshima

- Hiroshima Summary

- Character List

Essays for Hiroshima

Hiroshima essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Hiroshima by John Hersey.

- The Rebirth of a Few: Depicting Suffering and Endurance in 'Hiroshima'

Lesson Plan for Hiroshima

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to Hiroshima

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- Hiroshima Bibliography

Wikipedia Entries for Hiroshima

- Introduction

- Lasting impact

I work with the same writer every time. He knows my preferences and always delivers as promised. It’s like having a 24/7 tutor who is willing to help you no matter what. My grades improved thanks to him. That’s the story.

Write essay for me and soar high!

We always had the trust of our customers, and this is due to the superior quality of our writing. No sign of plagiarism is to be found within any content of the entire draft that we write. The writings are thoroughly checked through anti-plagiarism software. Also, you can check some of the feedback stated by our customers and then ask us to write essay for me.

Andre Cardoso

How does this work

Gustavo Almeida Correia

Customer Reviews

We use cookies to make your user experience better. By staying on our website, you fully accept it. Learn more .

Customer Reviews

Is buying essays online safe?

Shopping through online platforms is a highly controversial issue. Naturally, you cannot be completely sure when placing an order through an unfamiliar site, with which you have never cooperated. That is why we recommend that people contact trusted companies that have hundreds of positive reviews.

As for buying essays through sites, then you need to be as careful as possible and carefully check every detail. Read company reviews on third-party sources or ask a question on the forum. Check out the guarantees given by the specialists and discuss cooperation with the company manager. Do not transfer money to someone else's account until they send you a document with an essay for review.

Good online platforms provide certificates and some personal data so that the client can have the necessary information about the service manual. Service employees should immediately calculate the cost of the order for you and in the process of work are not entitled to add a percentage to this amount, if you do not make additional edits and preferences.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In essence, the function of the atomic bomb—the splitting apart of an atom—is to disturb and corrupt nature. The bomb is able to harness the power of the elements, earth, wind, fire, and water, and control nature as if it has the power of a god. Nature, however, quickly begins to reassert its own power, as the plants and flowers in ...

Hiroshima Essay. The most significant theme in John Hersey's book "Hiroshima" are the long- term effects of war, confusion about what happened, long term mental and physical scars, short term mental and physical scars, and people being killed. ... Hiroshima Outline. I. Manhatten Project (C)before German & Japanese, Pearl Harbor opportunity ...

Hiroshima Summary. Hiroshima, by John Hersey, deals with the human impact of the atomic bomb used on Hiroshima in 1945. Chapter 1 begins on the morning of the dropping of the atomic bomb (August 6 1945), resulting in the deaths of over one-hundred-thousand people.

Seventy-five years ago, journalist John Hersey's article "Hiroshima" forever changed how Americans viewed the atomic attack on Japan. On August 31, 1946, the editors of The New Yorker announced that the most recent edition "will be devoted entirely to just one article on the almost complete obliteration of a city by one atomic bomb.".

He went on to write "Hiroshima," a nonfiction account of the dropping of the first atomic bomb, which was published in August 1946 in the New Yorker. Illustration using an AP photo. Seventy-five years ago, on Aug. 6, 1945, a plane called the Enola Gay, manned by a crew from the U.S. Army Air Force, flew over the Japanese city of Hiroshima and ...

Hiroshima By John Hersey Chapter One A Noiseless Flash At exactly fifteen minutes past eight in the morning, on August 6, 1945, Japanese time, at the moment when the atomic bomb flashed above Hiroshima, Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the personnel department of the East Asia Tin Works, had just sat down at her place in the plant office and

The bombing of Hiroshima inspired many great works of fiction and nonfiction. Arguably the greatest was the 1959 film Hiroshima mon amour, directed by the French New Way auteur Alain Resnais, with a screenplay by the novelist Marguerite Duras.Readers looking for an authoritative account of the history and politics of the Hiroshima bombing should consult Ronald Takaki's Hiroshima: Why America ...

in which it first appeared. The following essay evaluates aspects of the post-World War II American milieu, the circumstances which led to the writing and publication of Hiroshima, and the techniques which Hersey employed in order to determine the meaning of his study for the Americans who first encountered it. The essay thereby

On the 76th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, Hersey's book still teaches about humanity and the craft of writing. The first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, on Aug. 6, 1945. LitHub.com. Today is the 76th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima. That's not a notable number in the rather arbitrary realm of anniversary stories.

Hiroshima's first line is perhaps one of journalism's best-known: "At exactly fifteen minutes past eight in the morning, on August 6, 1945, Japanese time, at the moment when the atomic bomb flashed above Hiroshima, Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the personnel department of the East Asia Tin Works, had just sat down at her place in the ...

Hiroshima is a nonfiction work by American journalist and writer John Hersey that was first published in 1946.It describes the stories of six survivors of the August 6, 1945, atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan. In one of the earliest examples of the New Journalism approach, Hersey applied techniques generally associated with fiction writing to tell the survivors' factual stories.

Lesley M.M. Blume's new book tells the story of John Hersey, the young journalist whose on-the-ground reporting in Hiroshima, Japan, exposed the world to the devastation of nuclear weapons.

The result was Hiroshima, a 30,000-word piece published in a single issue in August 1946 and later reprinted as a book. Over the years, it has been recommended to me several times, often by other ...

Hiroshima, and the admonition that his readers should know "them for they are like you" reflects his view that readers of. Hiroshima. should know the six survivors he tracks in his narrative because they too are "like" us, or more precisely, the readers of Hiroshima. In 1944, Hersey wrote, in three weeks, A. Bell for Adano.

Hiroshima Essay Questions. 1. How do Hersey's six subjects display different ways of coping with tragedy in the years following the bombing? In the aftermath of the attack on Hiroshima, the six subjects all lead very different lives that reflect both their personal differences from each other, as well as the varying ways of internalizing a ...

On the morning of August 6, 1945, the United States U.S. Army Air Forces B-29 Enola Gay dropped a uranium gun type device code named "Little Boy" on the city of Hiroshima (Military History, 2009). There were some 350,000 people living in Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945. Approximately 140,000 died that day and in the five months that ...

An essay about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. the start of the atomic age wwii began on september 1939, when germany invaded poland. as the war progressed, Skip to document. Ask AI. ... AP world chapter 29 outline. World History 100% (3) 9. 10.4 SQ 4. How did the British gain, consolidate, and maintain power in India Student.

Hiroshima Essay Outline. We select our writers from various domains of academics and constantly focus on enhancing their skills for our writing essay services. All of them have had expertise in this academic world for more than 5 years now and hold significantly higher degrees of education. Once the writers get your topic in hand, only after ...

Hiroshima Essay Outline - 2646 . Customer Reviews. Nursing Management Business and Economics History +104. 12 Customer reviews. ID 4817. We use cookies to make your user experience better. By staying on our website, you fully accept it. Learn more. 603 . Customer Reviews ...

Hiroshima Essay Outline. Social Sciences. Nursing Business and Economics Management Marketing +130. Deadline: Hire a Writer. Of course, we can deliver your assignment in 8 hours. Degree: Bachelor's.

Hiroshima Essay Outline | Best Writing Service. If you can't write your essay, then the best solution is to hire an essay helper. Since you need a 100% original paper to hand in without a hitch, then a copy-pasted stuff from the internet won't cut it. To get a top score and avoid trouble, it's necessary to submit a fully authentic essay.

Hiroshima Essay Outline. EssayService boasts its wide writer catalog. Our writers have various fields of study, starting with physics and ending with history. Therefore we are able to tackle a wide range of assignments coming our way, starting with the short ones such as reviews and ending with challenging tasks such as thesis papers.