- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About Migration Studies

- Editorial Board

- Call for Papers

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. studies of migration studies, 3. methodology, 4. metadata on migration studies, 5. topic clusters in migration studies, 6. trends in topic networks in migration studies, 7. conclusions, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

Mapping migration studies: An empirical analysis of the coming of age of a research field

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Asya Pisarevskaya, Nathan Levy, Peter Scholten, Joost Jansen, Mapping migration studies: An empirical analysis of the coming of age of a research field, Migration Studies , Volume 8, Issue 3, September 2020, Pages 455–481, https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mnz031

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Migration studies have developed rapidly as a research field over the past decades. This article provides an empirical analysis not only on the development in volume and the internationalization of the field, but also on the development in terms of topical focus within migration studies over the past three decades. To capture volume, internationalisation, and topic focus, our analysis involves a computer-based topic modelling of the landscape of migration studies. Rather than a linear growth path towards an increasingly diversified and fragmented field, as suggested in the literature, this reveals a more complex path of coming of age of migration studies. Although there seems to be even an accelerated growth for migration studies in terms of volume, its internationalisation proceeds only slowly. Furthermore, our analysis shows that rather than a growth of diversification of topics within migration topic, we see a shift between various topics within the field. Finally, our study shows that there is no consistent trend to more fragmentation in the field; in contrast, it reveals a recent recovery of connectedness between the topics in the field, suggesting an institutionalisation or even theoretical and conceptual coming of age of migration studies.

Migration studies have developed rapidly as a research field in recent decades. It encompasses studies on all types of international and internal migration, migrants, and migration-related diversity ( King, 2002 ; Scholten, 2018 ). Many scholars have observed the increase in the volume of research on migration ( Massey et al., 1998 ; Bommes and Morawska, 2005 ; Scholten et al., 2015 ). Additionally, the field has become increasingly varied in terms of links to broader disciplines ( King, 2012 ; Brettell and Hollifield, 2014 ) and in terms of different methods used ( Vargas-Silva, 2012 ; Zapata-Barrero and Yalaz, 2018 ). It is now a field that has in many senses ‘come of age’: it has internationalised with scholars involved from many countries; it has institutionalised through a growing number of journals; an increasing number of institutes dedicated to migration studies; and more and more students are pursuing migration-related courses. These trends are also visible in the growing presence of international research networks in the field of migration.

Besides looking at the development of migration in studies in terms of size, interdisciplinarity, internationalisation, and institutionalisation, we focus in this article on the development in topical focus of migration studies. We address the question how has the field of migration studies developed in terms of its topical focuses? What topics have been discussed within migration studies? How has the topical composition of the field changed, both in terms of diversity (versus unity) and connectedness (versus fragmentation)? Here, the focus is not on influential publications, authors, or institutes, but rather on what topics scholars have written about in migration studies. The degree of diversity among and connectedness between these topics, especially in the context of quantitative growth, will provide an empirical indication of whether a ‘field’ of migration studies exists, or to what extent it is fragmented.

Consideration of the development of migration studies invokes several theoretical questions. Various scholars have argued that the growth of migration studies has kept pace not only with the growing prominence of migration itself but also with the growing attention of nation–states in particular towards controlling migration. The coproduction of knowledge between research and policy, some argue ( Scholten, 2011 ), has given migration research an inclination towards paradigmatic closure, especially around specific national perspectives on migration. Wimmer and Glick Schiller (2002 ) speak in this regard of ‘methodological nationalism’, and others refer to the prominence of national models that would be reproduced by scholars and policymakers ( Bommes and Morawska, 2005 ; Favell, 2003 ). More generally, this has led, some might argue, to an overconcentration of the field on a narrow number of topics, such as integration and migration control, and a consequent call to ‘de-migranticise’ migration research ( Dahinden, 2016 ; see also Schinkel, 2018 ).

However, recent studies suggest that the growth of migration studies involves a ‘coming of age’ in terms of growing diversity of research within the field. This diversification of migration studies has occurred along the lines of internationalisation ( Scholten et al., 2015 ), disciplinary variation ( Yans-McLaughlin, 1990 ; King, 2012 ; Brettell and Hollifield, 2014 ) and methodological variation ( Vargas-Silva, 2012 ; Zapata-Barrero and Yalaz, 2018 ). The International Organization for Migration ( IOM, 2017 : 95) even concludes that ‘the volume, diversity, and growth of both white and grey literature preclude a [manual] systematic review’ of migration research produced in 2015 and 2016 alone .

Nonetheless, in this article, we attempt to empirically trace the development of migration studies over the past three decades, and seek to find evidence for the claim that the ‘coming of age’ of migration studies indeed involves a broadening of the variety of topics within the field. We pursue an inductive approach to mapping the academic landscape of >30 years of migration studies. This includes a content analysis based on a topic modelling algorithm, applied to publications from migration journals and book series. We trace the changes over time of how the topics are distributed within the corpus and the extent to which they refer to one another. We conclude by giving a first interpretation of the patterns we found in the coming of age of migration studies, which is to set an agenda for further studies of and reflection on the development of this research field. While migration research is certainly not limited to journals and book series that focus specifically on migration, our methods enable us to gain a representative snapshot of what the field looks like, using content from sources that migration researchers regard as relevant.

Migration has always been studied from a variety of disciplines ( Cohen, 1996 ; Brettell and Hollifield, 2014 ), such as economics, sociology, history, and demography ( van Dalen, 2018 ), using a variety of methods ( Vargas-Silva, 2012 ; Zapata-Barrero and Yalaz, 2018 ), and in a number of countries ( Carling, 2015 ), though dominated by Northern Hemisphere scholarship (see, e.g. Piguet et al., 2018 ), especially from North America and Europe ( Bommes and Morawska, 2005 ). Taking stock of various studies on the development of migration studies, we can define several expectations that we will put to an empirical test.

Ravenstein’s (1885) 11 Laws of Migration is widely regarded as the beginning of scholarly thinking on this topic (see Zolberg, 1989 ; Greenwood and Hunt, 2003 ; Castles and Miller, 2014 ; Nestorowicz and Anacka, 2018 ). Thomas and Znaniecki’s (1918) five-volume study of Polish migrants in Europe and America laid is also noted as an early example of migration research. However, according to Greenwood and Hunt (2003 ), migration research ‘took off’ in the 1930s when Thomas (1938) indexed 191 studies of migration across the USA, UK, and Germany. Most ‘early’ migration research was quantitative (see, e.g. Thornthwaite, 1934 ; Thomas, 1938 ). In addition, from the beginning, migration research developed with two empirical traditions: research on internal migration and research on international migration ( King and Skeldon, 2010 ; Nestorowicz and Anacka, 2018 : 2).

In subsequent decades, studies of migration studies describe a burgeoning field. Pedraza-Bailey (1990) refers to a ‘veritable boom’ of knowledge production by the 1980s. A prominent part of these debates focussed around the concept of assimilation ( Gordon, 1964 ) in the 1950s and 1960s (see also Morawska, 1990 ). By the 1970s, in light of the civil rights movements, researchers were increasingly focussed on race and ethnic relations. However, migration research in this period lacked an interdisciplinary ‘synthesis’ and was likely not well-connected ( Kritz et al., 1981 : 10; Pryor, 1981 ; King, 2012 : 9–11). Through the 1980s, European migration scholarship was ‘catching up’ ( Bommes and Morawska, 2005 : 14) with the larger field across the Atlantic. Substantively, research became increasingly mindful of migrant experiences and critical of (national) borders and policies ( Pedraza-Bailey, 1990 : 49). King (2012) also observes this ‘cultural turn’ towards more qualitative anthropological migration research by the beginning of the 1990s, reflective of trends in social sciences more widely ( King, 2012 : 24). In the 1990s, Massey et al. (1993, 1998 ) and Massey (1994) reflected on the state of the academic landscape. Their literature review (1998) notes over 300 articles on immigration in the USA, and over 150 European publications. Despite growth, they note that the field did not develop as coherently in Europe at it had done in North America (1998: 122).

We therefore expect to see a significant growth of the field during the 1980s and 1990s, and more fragmentation, with a prominence of topics related to culture and borders.

At the turn of the millennium, Portes (1997) lists what were, in his view, the five key themes in (international) migration research: 1 transnational communities; 2 the new second generation; 3 households and gender; 4 states and state systems; and 5 cross-national comparisons. This came a year after Cohen’s review of Theories of Migration (1996), which classifies nine key thematic ‘dyads’ in migration studies, such as internal versus international migration; individual versus contextual reasons to migrate; temporary versus permanent migration; and push versus pull factors (see full list in Cohen, 1996 : 12–15). However, despite increasing knowledge production, Portes argues that the problem in these years was the opposite of what Kritz et al. (1981) observe above; scholars had access to and generated increasing amounts of data, but failed to achieve ‘conceptual breakthrough’ ( Portes, 1997 : 801), again suggesting fragmentation in the field.

Thus, in late 1990s and early 2000s scholarship we expect to find a prominence of topics related to these five themes, and a limited number of “new” topics.

In the 21st century, studies of migration studies indicate that there has been a re-orientation away from ‘states and state systems’. This is exemplified by Wimmer and Glick Schiller’s (2002) widely cited commentary on ‘methodological nationalism’, and the alleged naturalisation of nation-state societies in migration research (see Thranhardt and Bommes, 2010 ), leading to an apparent pre-occupation with the integration paradigm since the 1980s according to Favell (2003) and others ( Dahinden, 2016 ; Schinkel, 2018 ). This debate is picked up in Bommes and Morawska’s (2005) edited volume, and Lavenex (2005) . Describing this shift, Geddes (2005) , in the same volume, observes a trend of ‘Europeanised’ knowledge production, stimulated by the research framework programmes of the EU. Meanwhile, on this topic, others highlight a ‘local turn’ in migration and diversity research ( Caponio and Borkert, 2010 ; Zapata-Barrero et al., 2017) .

In this light, we expect to observe a growth in references to European (and other supra-national) level and local-level topics in the 21t century compared to before 2000.

As well as the ‘cultural turn’ mentioned above, King (2012 : 24–25) observes a re-inscription of migration within wider social phenomena—in terms of changes to the constitutive elements of host (and sending) societies—as a key development in recent migration scholarship. Furthermore, transnationalism, in his view, continues to dominate scholarship, though this dominance is disproportionate, he argues, to empirical reality. According to Scholten (2018) , migration research has indeed become more complex as the century has progressed. While the field has continued to grow and institutionalise thanks to networks like International Migration, Integration and Social Cohesion in Europe (IMISCOE) and Network of Migration Research on Africa (NOMRA), this has been in a context of apparently increasing ‘fragmentation’ observed by several scholars for many years (see Massey et al., 1998 : 17; Penninx et al., 2008 : 8; Martiniello, 2013 ; Scholten et al., 2015 : 331–335).

On this basis, we expect a complex picture to emerge for recent scholarship, with thematic references to multiple social phenomena, and a high level of diversity within the topic composition of the field. We furthermore expect increased fragmentation within migration studies in recent years.

The key expectation of this article is, therefore, that the recent topical composition of migration studies displays greater diversity than in previous decades as the field has grown. Following that logic, we hypothesise that with diversification (increasingly varied topical focuses), fragmentation (decreasing connections between topics) has also occurred.

The empirical analysis of the development in volume and topic composition of migration studies is based on the quantitative methods of bibliometrics and topic modelling. Although bibliometric analysis has not been widely used in the field of migration (for some exceptions, see Carling, 2015 ; Nestorowicz and Anacka, 2018 ; Piguet et al., 2018 ; Sweileh et al., 2018 ; van Dalen, 2018 ), this type of research is increasingly popular ( Fortunato et al., 2018 ). A bibliometric analysis can help map what Kajikawa et al. (2007) call an ‘academic landscape’. Our analysis pursues a similar objective for the field of migration studies. However, rather than using citations and authors to guide our analysis, we extract a model of latent topics from the contents of abstracts . In other words, we are focussed on the landscape of content rather than influence.

3.1 Topic modelling

Topic modelling involves a computer-based strategy for identifying topics or topic clusters that figure centrally in a specific textual landscape (e.g. Jiang et al., 2016 ). This is a class of unsupervised machine learning techniques ( Evans and Aceves, 2016 : 22), which are used to inductively explore and discover patterns and regularities within a corpus of texts. Among the most widely used topic models is Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA). LDA is a type of Bayesian probabilistic model that builds on the assumption that each document in a corpus discusses multiple topics in differing proportions. Therefore, Document A might primarily be about Topic 1 (60 per cent), but it also refers to terms associated with Topic 2 (30 per cent), and, to a lesser extent, Topic 3 (10 per cent). A topic, then, is defined as a probability distribution over a fixed vocabulary, that is, the totality of words present in the corpus. The advantage of the unsupervised LDA approach that we take is that it does not limit the topic model to our preconceptions of which topics are studied by migration researchers and therefore should be found in the literature. Instead, it allows for an inductive sketching of the field, and consequently an element of surprise ( Halford and Savage, 2017 : 1141–1142). To determine the optimal number of topics, we used the package ldatuning to calculate the statistically optimal number of topics, a number which we then qualitatively validated.

The chosen LDA model produced two main outcomes. First, it yielded a matrix with per-document topic proportions, which allow us to generate an idea of the topics discussed in the abstracts. Secondly, the model returned a matrix with per-topic word probabilities. Essentially, the topics are a collection of words ordered by their probability of (co-)occurrence. Each topic contains all the words from all the abstracts, but some words have a much higher likelihood to belong to the identified topic. The 20–30 most probable words for each topic can be helpful in understanding the content of the topic. The third step we undertook was to look at those most probable words by a group of experts familiar with the field and label them. We did this systematically and individually by first looking at the top 5 words, then the top 30, trying to find an umbrella label that would summarize the topic. The initial labels suggested by each of us were then compared and negotiated in a group discussion. To verify the labels even more, in case of a doubt, we read several selected abstracts marked by the algorithm as exhibiting a topic, and through this were able to further refine the names of the topics.

It is important to remember that this list of topics should not be considered a theoretically driven attempt to categorize the field. It is purely inductive because the algorithm is unable to understand theories, conceptual frames, and approaches; it makes a judgement only on the basis of words. So if words are often mentioned together, the computer regards their probability of belonging to one topic as high.

3.2 Dataset of publications

For the topic modelling, we created a dataset that is representative of publications relevant to migration studies. First, we identified the most relevant sources of literature. Here we chose not only to follow rankings in citation indices, but also to ask migration scholars, in an expert survey, to identify what they considered to be relevant sources. This survey was distributed among a group of senior scholars associated with the IMISCOE Network; 25 scholars anonymously completed the survey. A set of journals and book series was identified from existing indices (such as Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus) which were then validated and added to by respondents. Included in our eventual dataset were all journals and book series that were mentioned at least by two experts in the survey. The dataset includes 40 journals and 4 book series (see Supplementary Data A). Non-English journals were omitted from data collection because the algorithm can only analyse one language. Despite their influence on the field, we also did not consider broader disciplinary journals (for instance, sociological journals or economic journals) for the dataset. Such journals, we acknowledge, have published some of the most important research in the history of migration studies, but even with their omission, it is still possible to achieve our goal of obtaining a representative snapshot of what migration researchers have studied, rather than who or which papers have been most influential. In addition, both because of the language restriction of the algorithm and because of the Global North’s dominance in the field that is mentioned above ( Bommes and Morawska, 2005 ; Piguet et al., 2018 ), there is likely to be an under-representation of scholarship from the Global South in our dataset.

Secondly, we gathered metadata on publications from the selected journals and book series using the Scopus and Web of Science electronic catalogues, and manually collecting from those sources available on neither Scopus nor Web of Science. The metadata included authors, years, titles, and abstracts. We collected all available data up to the end of 2017. In total, 94 per cent of our metadata originated from Scopus, ∼1 per cent from Web of Science, and 5 per cent was gathered manually. One limitation of our dataset lies in the fact that the electronic catalogue of Scopus, unfortunately, does not list all articles and abstracts ever published by all the journals (their policy is to collect articles and abstracts ‘where available’ ( Elsevier, 2017 )). There was no technical possibility of assessing Scopus or WoS’ proportional coverage of all articles actually published. The only way to improve the dataset in this regard would be to manually collect and count abstracts from journal websites. This is also why many relevant books were not included in our dataset; they are not indexed in such repositories.

In the earliest years of available data, only a few journals were publishing (with limited coverage of this on Scopus) specifically on migration. However, Fig. 1 below demonstrates that the numbers constantly grew between 1959 and 2018. As Fig. 1 shows, in the first 30 years (1959–88), the number of migration journals increased by 15, while in the following three decades (1989–2018), this growth intensified as the number of journals tripled to 45 in the survey (see Supplementary Data A for abbreviations).

Number of journals focussed on migration and migration-related diversity (1959–2018) Source: Own calculations.

Within all 40 journals in the dataset, we were able to access and extract for our analysis 29,844 articles, of which 22,140 contained abstracts. Furthermore, we collected 901 available abstracts of chapters in the 4 book series: 2 series were downloaded from the Scopus index (Immigration and Asylum Law in Europe; Handbook of the Economics of International Migration), and the abstracts of the other 2 series, selected from our expert survey (the IMISCOE Research Series Migration Diasporas and Citizenship), were collected manually. Given the necessity of manually collecting the metadata for 896 abstracts of the chapters in these series, it was both practical and logical to set these two series as the cut-off point. Ultimately, we get a better picture of the academic landscape as a whole with some expert-approved book series than with none .

Despite the limitations of access, we can still have an approximate idea on how the volume of publications changed overtime. The chart ( Fig. 2 ) below shows that both the number of published articles and the number of abstracts of these articles follow the same trend—a rapid growth after the turn of the century. In 2017, there were three times more articles published per year than in 2000.

Publications and abstracts in the dataset (1959–2018).

The cumulative graph ( Fig. 3 ) below shows the total numbers of publications and the available abstracts. For the creation of our inductively driven topic model, we used all available abstracts in the entire timeframe. However, to evaluate the dynamics of topics over time, we decided to limit the timeframe of our chronological analyses to 1986–2017, because as of 1986, there were more than 10 active journals and more articles had abstracts. This analysis therefore covers the topical evolution of migration studies in the past three decades.

Cumulative total of publications and abstracts (1959–2017).

Migration studies has only internationalised very slowly in support of what others have previously argued ( Bommes and Morawska, 2005 ; Piguet et al., 2018 ). Figure 4 gives a snapshot of the geographic dispersion of the articles (including those without abstracts) that we collected from Scopus. Where available, we extracted the country of authors’ university affiliations. The colour shades represent the per capita publication volume. English-language migration scholarship has been dominated by researchers based, unsurprisingly, in Anglophone and Northern European countries.

Migration research output per capita (based on available affiliation data within dataset).

The topic modelling (following the LDA model) led us, as discussed in methods, to the definition of 60 as the optimal number of topics for mapping migration studies. Each topic is a string of words that, according to the LDA algorithm, belong together. We reviewed the top 30 words for each word string and assigned labels that encapsulated their meaning. Two of the 60 word strings were too generic and did not describe anything related to migration studies; therefore, we excluded them. Subsequently, the remaining 58 topics were organised into a number of clusters. In the Table 1 below, you can see all the topic labels, the topic clusters they are grouped into and the first 5 (out of 30) most probable words defining those topics.

Topics in migration studies

After presenting all the observed topics in the corpus of our publication data, we examined which topics and topic clusters are most frequent in general (between 1964 and 2017), and how their prominence has been changing over the years. On the basis of the matrix of per-item topic proportions generated by LDA analysis, we calculated the shares of each topic in the whole corpus. On the level of individual topics, around 25 per cent of all abstract texts is about the top 10 most prominent topics, which you can see in Fig. 5 below. Among those, #56 identity narratives (migration-related diversity), #39 migration theory, and #29 migration flows are the three most frequently detected topics.

Top 10 topics in the whole corpus of abstracts.

On the level of topic clusters, Fig. 6 (left) shows that migration-related diversity (26 per cent) and migration processes (19 per cent) clearly comprise the two largest clusters in terms of volume, also because they have the largest number topics belonging to them. However, due to our methodology of labelling these topics and grouping them into clusters, it is complicated to make comparisons between topic clusters in terms of relative size, because some clusters simply contain more topics. Calculating average proportions of topics within each cluster allows us to control for the number of topics per cluster, and with this measure, we can better compare the relative prominence of clusters. Figure 6 (right) shows that migration research and statistics have the highest average of topic proportions, followed by the cluster of migration processes and immigrant incorporation.

Topic proportions per cluster.

An analysis on the level of topic clusters in the project’s time frame (1986–2017) reveals several significant trends. First, when discussing shifts in topics over time, we can see that different topics have received more focus in different time frames. Figure 7 shows the ‘age’ of topics, calculated as average years weighted by proportions of publications within a topic per year. The average year of the articles on the same topic is a proxy for the age of the topic. This gives us an understanding of which topics were studied more often compared with others in the past and which topics are emerging. Thus, an average year can be understood as the ‘high-point’ of a topic’s relative prominence in the field. For instance, the oldest topics in our dataset are #22 ‘Migrant demographics’, followed by #45 ‘Governance of migration’ and #46 ‘Migration statistics and survey research’. The newest topics include #14 ‘Mobilities’ and #48 ‘Intra-EU mobility’.

Average topic age, weighted by proportions of publications (publications of 1986–2017). Note: Numbers near dots indicate the numeric id of topics (see Table 1 for the names).

When looking at the weighted ‘age’ of the clusters, it becomes clear that the focus on migration research and statistics is the ‘oldest’, which echoes what Greenwood and Hunt (2003 ) observe. This resonates with the idea that migration studies has roots in more demographic studies of migration and diversity (cf. Thornthwaite, 1934 ; Thomas, 1938 ), which somewhat contrasts with what van Dalen (2018) has found. Geographies of migration (studies related to specific migration flows, origins, and destinations) were also more prominent in the 1990s than now, and immigrant incorporation peaked at the turn of the century. However, gender and family, diversity, and health are more recent themes, as was mentioned above (see Fig. 8 ). This somewhat indicates a possible post-methodological nationalism, post-integration paradigm era in migration research going hand-in-hand with research that, as King (2012) argues, situates migration within wider social and political domains (cf. Scholten, 2018 ).

Diversity of topics and topic clusters (1985–2017).

Then, we analysed the diversification of publications over the various clusters. Based on the literature review, we expected the diversification to have increased over the years, signalling a move beyond paradigmatic closure. Figure 9 (below) shows that we can hardly speak of a significant increase of diversity in migration studies publications. Over the years, only a marginal increase in the diversity of topics is observed. The Gini-Simpson index of diversity in 1985 was around 0.95 and increased to 0.98 from 1997 onwards. Similarly, there is little difference between the sizes of topic clusters over the years. Both ways of calculating the Gini-Simpson index of diversity by clusters resulted in a rather stable picture showing some fluctuations between 0.82 and 0.86. This indicates that there has never been a clear hegemony of any cluster at any time. In other words, over the past three decades, the diversity of topics and topic clusters was quite stable: there have always been a great variety of topics discussed in the literature of migration studies, with no topic or cluster holding a clear monopoly.

Average age of topic clusters, weighted by proportions (publications of 1986–2017).

Subsequently, we focussed on trends in topic networks. As our goal is to describe the general development of migration studies as a field, we decided to analyse topic networks in three equal periods of 10 years (Period 1 (1988–97); Period 2 (1998–2007); Period 3 (2008–17)). On the basis of the LDA-generated matrix with per-abstract topic proportions (The LDA algorithm determines the proportions of all topics observed within each abstract. Therefore, each abstract can contain several topics with a substantial prominence), we calculated the topic-by-topic Spearman correlation coefficients in each of the time frames. From the received distribution of the correlation coefficients, we chose to focus on the top 25 per cent strongest correlations period. In order to highlight difference in strength of connections, we assigned different weights to the correlations between the topics. Coefficient values above the 75th percentile (0.438) but ≤0.5 were weighted 1; correlations above 0.5 but ≤0.6 were weighted 2; and correlations >0.6 were weighted 3. We visualised these topic networks using the software Gephi.

To compare networks of topics in each period, we used three common statistics of network analysis: 1 average degree of connections; 2 average weighted degree of connections; and 3 network density. The average degree of connections shows how many connections to other topics each topic in the network has on average. This measure can vary from 0 to N − 1, where N is the total number of topics in the network. Some correlations of topics are stronger and were assigned the Weight 2 or 3. These are included in the statistics of average weighted degree of connections, which shows us the variations in strength of existing connections between the topics. Network density is a proportion of existing links over the number of all potentially possible links between the topics. This measure varies from 0 = entirely disconnected topics to 1 = extremely dense network, where every topic is connected to every topic.

Table 2 shows that all network measures vary across the three periods. In Period 1, each topic had on average 21 links with other topics, while in Period 2, that number was much lower (11.5 links). In Period 3, the average degree of connections grew again, but not to the level of Period 1. The same trend is observed in the strength of these links—in Period 1, the correlations between the topics were stronger than in Period 3, while they were the weakest in Period 2. The density of the topic networks was highest in Period 1 (0.4), then in Period 2, the topic network became sparser before densifying again in Period 3 (but not to the extent of Period 1’s density).

Topic network statistics

These fluctuations on network statistics indicate that in the years 1988–97, topics within the analysed field of migration studies were mentioned in the same articles and book chapters more often, while at the turn of the 21st century, these topic co-occurrences became less frequent; publications therefore became more specialised and topics were more isolated from each other. In the past 10 years, migration studies once again became more connected, the dialogues between the topics emerged more frequently. These are important observations about topical development in the field of migration studies. The reasons behind these changes require further, possibly more qualitative explanation.

To get a more in-depth view of the content of these topic networks, we made an overview of the changes in the topic clusters across the three periods. As we can see in Fig. 10 , some changes emerge in terms of the prominence of various clusters. The two largest clusters (also by the number of topics within them) are migration-related diversity and migration processes. The cluster of migration-related diversity increased in its share of each period’s publications by around 20 per cent. This reflects our above remarks on the literature surrounding the integration debate, and the ‘cultural turn’ King mentions (2012). And the topic cluster migration processes also increased moderately its share.

Prominence and change in topic clusters 1988–2017.

Compared with the first period, the topic cluster of gender and family studies grew the fastest, with the largest growth observed in the turn of the century (relative to its original size). This suggests a growing awareness of gender and family-related aspects of migration although as a percentage of the total corpus it remains one the smallest clusters. Therefore, Massey et al.’s (1998) argument that households and gender represented a quantitatively significant pillar of migration research could be considered an overestimation. The cluster of health studies in migration research also grew significantly in the Period 2 although in Period 3, the percentage of publications in this cluster diminished. This suggests a rising awareness of health in relation to migration and diversity (see Sweileh et al., 2018 ) although this too remains one of the smallest clusters.

The cluster on Immigrant incorporation lost prominence the most over the past 30 years. This seems to resonate with the argument that ‘integrationism’ or the ‘integration paradigm’ was rather in the late 1990s (see Favell, 2003 ; Dahinden, 2016 ) and is losing its prominence. A somewhat slower but steady loss was also observed in the cluster of Geographies of migration and Migration research and statistics. This also suggests not only a decreasing emphasis on demographics within migration studies, but also a decreasing reflexivity in the development of the field and the focus on theory-building.

We will now go into more detail and show the most connected topics and top 10 most prominent topics in each period. Figures 11–13 show the network maps of topics in each period. The size of circles reflects the number and strength of links per each topic: the bigger the size, the more connected this topic is to the others; the biggest circles indicate the most connected topics. While the prominence of a topic is measured by the number of publications on that topic, it is important to note that the connectedness the topic has nothing necessarily to do with the amount of publications on that topic; in theory, a topic could appear in many articles without any reference to other topics (which would mean that it is prominent but isolated).

Topic network in 1988–97. Note: Numbers indicate topics' numerical ids, see Table 1 for topics' names.

Topic network in 1998–2007. Note: Numbers indicate topics' numerical ids, see Table 1 for topics' names.

Topic network in 2008–2017. Note: Numbers indicate topics' numerical ids, see Table 1 for topics' names.

Thus, in the section below, we describe the most connected and most prominent topics in migration research per period. The degree of connectedness is a useful indicator of the extent to which we can speak of a ‘field’ of migration research. If topics are well-connected, especially in a context of increased knowledge production and changes in prominence among topics, then this would suggest that a shared conceptual and theoretical language exists.

6.1 Period 1: 1988–97

The five central topics with the highest degree of connectedness (the weighted degree of connectedness of these topics was above 60) were ‘black studies’, ‘mobilities’, ‘ICT, media and migration’, ‘migration in/from Israel and Palestine’, and ‘intra-EU mobility’. These topics are related to geopolitical regions, ethnicity, and race. The high degree of connectedness of these topics shows that ‘they often occurred together with other topics in the analysed abstracts from this period’. This is expected because research on migration and diversity inevitably discusses its subject within a certain geographical, political, or ethnic scope. Geographies usually appear in abstracts as countries of migrants’ origin or destination. The prominence of ‘black studies’ reflects the dominance of American research on diversity, which was most pronounced in this period ( Fig. 11 ).

The high degree of connectedness of the topics on ICT and ‘media’ is indicative of wider societal trends in the 1990s. As with any new phenomenon, it clearly attracted the attention of researchers who wanted to understand its relationship with migration issues.

Among the top 10 topics with the most publications in this period (see Supplementary Data B) were those describing the characteristics of migration flows (first) and migration populations (third). It goes in line with the trends of the most connected topics described above. Interest in questions of migrants’ socio-economic position (fourth) in the receiving societies and discussion on ‘labour migration’ (ninth) were also prevalent. Jointly, these topics confirm that in the earlier years, migration was ‘studied often from the perspectives of economics and demographics’ ( van Dalen, 2018 ).

Topics, such as ‘education and language training’ (second), community development’ (sixth), and ‘intercultural communication’ (eighth), point at scholarly interest in the issues of social cohesion and socio-cultural integration of migrants. This lends strong support to Favell’s ‘integration paradigm’ argument about this period and suggests that the coproduction of knowledge between research and policy was indeed very strong ( Scholten, 2011 ). This is further supported by the prominence of the topic ‘governance of migration’ (seventh), reflecting the evolution of migration and integration policymaking in the late 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, exemplified by the development of the Schengen area and the EU more widely; governance of refugee flows from the Balkan region (also somewhat represented in the topic ‘southern-European migration’, which was the 10th most prominent); and governance of post-Soviet migration. Interestingly, this is the only period in which ‘migration histories’ is among the top 10 topics, despite the later establishment of a journal dedicated to the very discipline of history. Together these topics account for 42 per cent of all migration studies publications in that period of time.

6.2 Period 2: 1998–2007

In the second period, as the general degree of connectedness in the topic networks decreased, the following five topics maintained a large number of connections in comparison to others, as their average weighted degree of connections ranged between 36 and 57 ties. The five topics were ‘migration in/from Israel and Palestine’, ‘black studies’, ‘Asian migration’, ‘religious diversity’, and ‘migration, sexuality, and health’ ( Fig. 12 ).

Here we can observe the same geographical focus of the most connected topics, as well as the new trends in the migration research. ‘Asian migration’ became one of the most connected topics, meaning that migration from/to and within that region provoked more interest of migration scholars than in the previous decade. This development appears to be in relation to high-skill migration, in one sense, because of its strong connections with the topics ‘Asian expat migration’ and ‘ICT, media, and migration’; and, in another sense, in relation to the growing Muslim population in Europe thanks to its strong connection to ‘religious diversity’. The high connectedness of the topic ‘migration sexuality and health’ can be explained by the dramatic rise of the volume of publications within the clusters ‘gender and family’ studies and ‘health’ in this time-frame as shown in the charts on page 13, and already argued by Portes (1997) .

In this period, ‘identity narratives’ became the most prominent topic (see Supplementary Data B), which suggests increased scholarly attention on the subjective experiences of migrants. Meanwhile ‘migrant flows’ and ‘migrant demographics’ decreased in prominence from the top 3 to the sixth and eighth position, respectively. The issues of education and socio-economic position remained prominent. The emergence of topics ‘migration and diversity in (higher) education’ (fifth) and ‘cultural diversity’ (seventh) in the top 10 of this period seem to reflect a shift from integrationism to studies of diversity. The simultaneous rise of ‘migration theory’ (to fourth) possibly illustrates the debates on methodological nationalism which emerged in the early 2000s. The combination of theoretical maturity and the intensified growth in the number of migration journals at the turn of the century suggests that the field was becoming institutionalised.

Overall, the changes in the top 10 most prominent topics seem to show a shifting attention from ‘who’ and ‘what’ questions to ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions. Moreover, the top 10 topics now account only for 26 per cent of all migration studies (a 15 per cent decrease compared with the period before). This means that there were many more topics which were nearly as prominent as those in the top 10. Such change again supports our claim that in this period, there were more intensive ‘sub-field’ developments in migration studies than in the previous period.

6.3 Period 3: 2008–17

In the last decade, the most connected topics have continued to be: ‘migration in/from Israel and Palestine’, ‘Asian migration’, and ‘black studies’. The hypothetical reasons for their central position in the network of topics are the same as in the previous period. The new most-connected topics—‘Conflicts, violence, and migration’, together with the topic ‘Religious diversity’—might indicate to a certain extent the widespread interest in the ‘refugee crisis’ of recent years ( Fig. 13 ).

The publications on the top 10 most prominent topics constituted a third of all migration literature of this period analysed in our study. A closer look at them reveals the following trends (see Supplementary Data B for details). ‘Mobilities’ is the topic of the highest prominence in this period. Together with ‘diasporas and transnationalism’ (fourth), this reflects the rise of critical thinking on methodological nationalism ( Wimmer and Glick Schiller, 2002 ) and the continued prominence of transnationalism in the post-‘mobility turn’ era ( Urry (2007) , cited in King, 2012 ).

The interest in subjective experiences of migration and diversity has continued, as ‘identity narratives’ continues to be prominent, with the second highest proportion of publications, and as ‘Discrimination and socio-psychological issues’ have become the eighth most prominent topic. This also echoes an increasing interest in the intersection of (mental) health and migration (cf. Sweileh et al., 2018 ).

The prominence of the topics ‘human rights law and protection’ (10th) and ‘governance of migration and diversity’ (9th), together with ‘conflicts, violence, and migration’ being one of the most connected topics, could be seen as a reflection of the academic interest in forced migration and asylum. Finally, in this period, the topics ‘race and racism’ (fifth) and ‘black studies’ (seventh) made it into the top 10. Since ‘black studies’ is also one of the most connected topics, such developments may reflect the growing attention to structural and inter-personal racism not only in the USA, perhaps reflecting the #blacklivesmatter movement, as well as in Europe, where the idea of ‘white Europeanness’ has featured in much public discourse.

6.4 Some hypotheses for further research

Why does the connectedness of topics change across three periods? In an attempt to explain these changes, we took a closer look at the geographical distribution of publications in each period. One of the trends that may at least partially explain the loss of connectedness between the topics in Period 2 could be related to the growing internationalisation of English language academic literature linked to a sharp increase in migration-focussed publications during the 1990s.

Internationalisation can be observed in two ways. First, the geographies of English language journal publications have become more diverse over the years. In the period 1988–97, the authors’ institutional affiliations spanned 57 countries. This increased to 72 in 1998–2007, and then to 100 in 2007–18 (we counted only those countries which contained at least 2 publications in our dataset). Alongside this, even though developed Anglophone countries (the USA, Canada, Australia, the UK, Ireland, and New Zealand) account for the majority of publications of our overall dataset, the share of publications originating from non-Anglophone countries has increased over time. In 1988–97, the number of publications from non-Anglophone European (EU+EEA) countries was around 13 per cent. By 2008–17, this had significantly increased to 28 per cent. Additionally, in the rest of the world, we observe a slight proportional increase from 9.5 per cent in the first period to 10.6 per cent in the last decade. Developed Anglophone countries witness a 16 per cent decrease in their share of all articles on migration. The trends of internationalisation illustrated above, combined with the loss of connectedness at the turn of the 21st century, seem to indicate that English became the lingua-franca for academic research on migration in a rather organic manner.

It is possible that a new inflow of ideas came from the increased number of countries publishing on migration whose native language is not English. This rise in ‘competition’ might also have catalysed innovation in the schools that had longer established centres for migration studies. Evidence for this lies in the rise in prominence of the topic ‘migration theory’ during this period. It is also possible that the expansion of the European Union and its research framework programmes, as well as the Erasmus Programmes and Erasmus Mundus, have perhaps brought novel, comparative, perspectives in the field. All this together might have created fruitful soil for developing unique themes and approaches, since such approaches in theory lead to more success and, crucially, more funds for research institutions.

This, however, cannot fully explain why in Period 3 the field became more connected again, other than that the framework programmes—in particular framework programme 8, Horizon 2020—encourage the building of scientific bridges, so to speak. Our hypothesis is thus that after the burst of publications and ideas in Period 2, scholars began trying to connect these new themes and topics to each other through emergent international networks and projects. Perhaps even the creation and work of the IMISCOE (2004-) and NOMRA (1998-) networks contributed to this process of institutionalisation. This, however, requires much further thought and exploration, but for now, we know that the relationship between the growth, the diversification, and the connectedness in this emergent research field is less straightforward than we might previously have suggested. This begs for further investigation perhaps within a sociology of science framework.

This article offers an inductive mapping of the topical focus of migration studies over a period of more than 30 years of development of the research field. Based on the literature, we expected to observe increasing diversity of topics within the field and increasing fragmentation between the topics, also in relation to the rapid growth in volume and internationalisation of publications in migration studies. However, rather than growth and increased diversity leading to increased fragmentation, our analysis reveals a complex picture of a rapidly growing field where the diversity of topics has remained relatively stable. Also, even as the field has internationalised, it has retained its overall connectedness, albeit with a slight and temporary fragmentation at the turn of the century. In this sense, we can argue that migration studies have indeed come of age as a distinct research field.

In terms of the volume of the field of migration studies, our study reveals an exponential growth trajectory, especially since the mid-1990s. This involves both the number of outlets and the number of publications therein. There also seems to be a consistent path to internationalisation of the field, with scholars from an increasing number of countries publishing on migration, and a somewhat shrinking share of publications from Anglo-American countries. However, our analysis shows that this has not provoked an increased diversity of topics in the field. Instead, the data showed that there have been several important shifts in terms of which topics have been most prominent in migration studies. The field has moved from focusing on issues of demographics, statistics, and governance, to an increasing focus on mobilities, migration-related diversity, gender, and health. Also, interest in specific geographies of migration seems to have decreased.

These shifts partially resonated with the expectations derived from the literature. In the 1980s and 1990s, we observed the expected widespread interest in culture, seen in publications dealing primarily with ‘education and language training’, ‘community development’, and ‘intercultural communication’. This continued to be the case at the turn of the century, where ‘identity narratives’ and ‘cultural diversity’ became prominent. The expected focus on borders in the periods ( Pedraza-Bailey, 1990 ) was represented by the high proportion of research on the ‘governance of migration’, ‘migration flows’, and in the highly connected topic ‘intra-EU mobility’. Following Portes (1997) , we expected ‘transnational communities’, ‘states and state systems’, and the ‘new second generation’ to be key themes for the ‘new century’. Transnationalism shifts attention away from geographies of migration and nation–states, and indeed, our study shows that ‘geographies of migration’ gave way to ‘mobilities’, the most prominent topic in the last decade. This trend is supported by the focus on ‘diasporas and transnationalism’ and ‘identity narratives’ since the 2000s, including literature on migrants’ and their descendants’ dual identities. These developments indicate a paradigmatic shift in migration studies, possibly caused by criticism of methodological nationalism. Moreover, our data show that themes of families and gender have been discussed more in the 21st century, which is in line with Portes’ predictions.

The transition from geographies to mobilities and from the governance of migration to the governance of migration-related diversity, race and racism, discrimination, and social–psychological issues indicates a shifting attention in migration studies from questions of ‘who’ and ‘what’ towards ‘how’ and ‘why’. In other words, a more nuanced understanding of the complexity of migration processes and consequences emerges, with greater consideration of both the global and the individual levels of analysis.

However, this complexification has not led to thematic fragmentation in the long run. We did not find a linear trend towards more fragmentation, meaning that migration studies have continued to be a field. After an initial period of high connectedness of research mainly coming from America and the UK, there was a period with significantly fewer connections within migration studies (1998–2007), followed by a recovery of connectedness since then, while internationalisation has continued. What does this tell us?

We may hypothesise that the young age of the field and the tendency towards methodological nationalism may have contributed to more connectedness in the early days of migration studies. The accelerated growth and internationalisation of the field since the late 1990s may have come with an initial phase of slight fragmentation. The increased share of publications from outside the USA may have caused this, as according to Massey et al. (1998) , European migration research was then more conceptually dispersed than across the Atlantic. The recent recovery of connectedness could then be hypothesised as an indicator of the field’s institutionalisation, especially at the European level, and growing conceptual and theoretical development. As ‘wisdom comes with age’, this may be an indication of the ‘coming of age’ of migration studies as a field with a shared conceptual and theoretical foundation.

The authors would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback, as well as dr. J.F. Alvarado for his advice in the early stages of work on this article.

This research is associated with the CrossMigration project, funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the grant agreement Ares(2017) 5627812-770121.

Conflict of interest statement . None declared.

Bommes M. , Morawska E. ( 2005 ) International Migration Research: Constructions, Omissions and the Promises of Interdisciplinarity . Aldershot : Ashgate .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Brettell C. B. , Hollifield J. F. ( 2014 ) Migration Theory: Talking across Disciplines . London : Routledge .

Caponio T. , Borkert M. ( 2010 ) The Local Dimension of Migration Policymaking . Amsterdam : Amsterdam University Press .

Carling J. ( 2015 ) Who Is Who in Migration Studies: 107 Names Worth Knowing < https://jorgencarling.org/2015/06/01/who-is-who-in-migration-studies-108-names-worth-knowing/#_Toc420761452 > accessed 1 Jun 2015.

Castles S. , Miller M. J. ( 2014 ) The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World , 5th edn. Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan .

Cohen R. ( 1996 ) Theories of Migration . Cheltenham : Edward Elgar .

Dahinden J. ( 2016 ) ‘A Plea for the “De-migranticization” of Research on Migration and Integration,’ Ethnic and Racial Studies , 39 / 13 : 2207 – 25 .

Elsevier ( 2017 ) Scopus: Content Coverage Guide . < https://www.elsevier.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/69451/0597-Scopus-Content-Coverage-Guide-US-LETTER-v4-HI-singles-no-ticks.pdf > accessed 18 Dec 2018.

Evans J. A. , Aceves P. ( 2016 ) ‘Machine Translation: Mining Text for Social Theory,’ Annual Review of Sociology’ , 42 / 1 : 21 – 50 .

Favell A. ( 2003 ) ‘Integration Nations: The Nation-State and Research on Immigrants in Western Europe’, in Brochmann G. , ed. The Multicultural Challenge , pp. 13 – 42 . Bingley : Emerald .

Fortunato S. , et al. ( 2018 ) ‘Science of Science’ , Science , 359 / 6379 : 1 – 7 .

Geddes A. ( 2005 ) ‘Migration Research and European Integration: The Construction and Institutionalization of Problems of Europe’, in Bommes M. , Morawska E. (eds). International Migration Research: Constructions, Omissions and the Promises of Interdisciplinarity , pp. 265 – 280 . Aldershot : Ashgate .

Gordon M. ( 1964 ) Assimilation in American Life . New York : Oxford University Press .

Greenwood M. J. , Hunt G. L. ( 2003 ) ‘The Early History of Migration Research,’ International Regional Sciences Review , 26 / 1 : 3 – 37 .

Halford S. , Savage M. ( 2017 ) ‘Speaking Sociologically with Big Data: Symphonic Social Science and the Future for Big Data Research,’ Sociology , 51 / 6 : 1132 – 48 .

IOM ( 2017 ) ‘Migration Research and Analysis: Growth, Reach and Recent Contributions’, in IOM, World Migration Report 2018 , pp. 95 – 121 . Geneva : International Organization for Migration .

Jiang H. , Qiang M. , Lin P. ( 2016 ) ‘A Topic Modeling Based Bibliometric Exploratoin of Hydropower Research,’ Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews , 57 : 226 – 37 .

Kajikawa Y. , et al. ( 2007 ) ‘Creating an Academic Landscape of Sustainability Science: An Analysis of the Citation Network,’ Sustainability Science , 2 / 2 : 221 – 31 .

King R. , Skeldon R. ( 2010 ) ‘Mind the Gap: Integrating Approaches to Internal and International Migration,’ Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies , 36 / 10 : 1619 – 46 .

King R. , Skeldon R. ( 2002 ) ‘Towards a New Map of European Migration,’ International Journal of Population Geography , 8 / 2 : 89 – 106 .

King R. , Skeldon R. ( 2012 ) Theories and Typologies of Migration: An Overview and a Primer . Malmö : Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM ).

Kritz M. M. , Keely C. B. , Tomasi S. M. ( 1981 ) Global Trends in Migration: Theory and Research on International Population Movements . New York : The Centre for Migration Studies .

Lavenex S. ( 2005 ) ‘National Frames in Migration Research: The Tacit Political Agenda’, in Bommes M. , Morawska E. (eds) International Migration Research: Constructions, Omissions and the Promises of Interdisciplinarity , pp. 243 – 263 . Aldershot : Ashgate .

Martiniello M. ( 2013 ) ‘Comparisons in Migration Studies,’ Comparative Migration Studies , 1 / 1 : 7 – 22 .

Massey D. S. , et al. ( 1993 ) ‘Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal,’ Population and Development Review , 19 / 3 : 431 – 66 .

Massey D. S. ( 1994 ) ‘An Evaluation of International Migration Theory: The North American Case,’ Population and Development Review , 20 / 4 : 699 – 751 .

Massey D. S. , et al. ( 1998 ) Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium . Oxford : Clarendon .

Morawska E. ( 1990 ) ‘The Sociology and Historiography of Immigration’, In Yans-McLaughlin V. , (ed.) Immigration Reconsidered: History, Sociology, and Politics . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Nestorowicz J. , Anacka M. ( 2018 ) ‘Mind the Gap? Quantifying Interlinkages between Two Traditions in Migration Literature,’ International Migration Review , 53/1 : 1 – 25 .

Pedraza-Bailey S. ( 1990 ) ‘Immigration Research: A Conceptual Map,’ Social Science History , 14 / 1 : 43 – 67 .

Penninx R. , Spencer D. , van Hear N. ( 2008 ) Migration and Integration in Europe: The State of Research . Oxford : ESRC Centre on Migration, Policy and Society .

Piguet E. , Kaenzig R. , Guélat J. ( 2018 ) ‘The Uneven Geography of Research on “Environmental Migration”,’ Population and Environment , 39 / 4 : 357 – 83 .

Portes A. ( 1997 ) ‘Immigration Theory for a New Century: Some Problems and Opportunities,’ International Migration Review , 31 / 4 : 799 – 825 .

Pryor R. J. ( 1981 ) ‘Integrating International and Internal Migration Theories’, in Kritz M. M. , Keely C. B. , Tomasi S. M. (eds) Global Trends in Migration: Theory and Research on International Population Movements , pp. 110 – 129 . New York : The Center for Migration Studies .

Ravenstein G. E. ( 1885 ) ‘The Laws of Migration,’ Journal of the Royal Statistical Society , 48 : 167 – 235 .

Schinkel W. ( 2018 ) ‘Against “Immigrant Integration”: For an End to Neocolonial Knowledge Production,’ Comparative Migration Studies , 6 / 31 : 1 – 17 .

Scholten P. ( 2011 ) Framing Immigrant Integration: Dutch Research-Policy Dialogues in Comparative Perspective . Amsterdam : Amsterdam University Press .

Scholten P. ( 2018 ) Mainstreaming versus Alienation: Conceptualizing the Role of Complexity in Migration and Diversity Policymaking . Rotterdam : Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam .

Scholten P. , et al. ( 2015 ) Integrating Immigrants in Europe: Research-Policy Dialogues . Dordrecht : Springer .

Sweileh W. M. , et al. ( 2018 ) ‘Bibliometric Analysis of Global Migration Health Research in Peer-Reviewed Literature (2000–2016)’ , BMC Public Health , 18 / 777 : 1 – 18 .

Thomas D. S. ( 1938 ) Research Memorandum on Migration Differentials . New York : Social Science Research Council .

Thornthwaite C. W. ( 1934 ) Internal Migration in the United States . Philadelphia, PA : University of Pennsylvania Press .

Thränhardt D. , Bommes M. ( 2010 ) National Paradigms of Migration Research . Göttingen : V&R Unipress .

Urry J. ( 2007 ) Mobilities . Cambridge : Polity .

van Dalen H. ( 2018 ) ‘Is Migration Still Demography’s Stepchild?’ , Demos: Bulletin over Bevolking en Samenleving , 34 / 5 : 8 .

Vargas-Silva C. ( 2012 ) Handbook of Research Methods in Migration . Cheltenham : Edward Elgar .

Wimmer A. , Glick Schiller N. ( 2002 ) ‘Methodological Nationalism and beyond: Nation-State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences,’ Global Networks , 2 / 4 : 301 – 34 .

Yans-McLaughlin V. ( 1990 ) Immigration Reconsidered: History, Sociology, and Politics . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Zapata-Barrero R. , Yalaz E. ( 2018 ) Qualitative Research in European Migration Studies . Dordrecht : Springer .

Zapata-Barrero R. , Caponio T. , Scholten P. ( 2017 ) ‘Theorizing the “Local Turn” in a Multi-Level Governance Framework of Analysis: A Case Study in Immigrant Policies,’ International Review of Administrative Sciences , 83 / 2 : 241 – 6 .

Zolberg A. R. ( 1989 ) ‘The Next Waves: Migration Theory for a Changing World,’ International Migration Review , 23 / 3 : 403 – 30 .

Supplementary data

Email alerts, citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2049-5846

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Advertisement

A systematic review of climate migration research: gaps in existing literature

- Review Paper

- Open access

- Published: 16 April 2022

- Volume 2 , article number 47 , ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Rajan Chandra Ghosh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9027-6649 1 , 2 &

- Caroline Orchiston ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3171-2006 1

9895 Accesses

9 Citations

12 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

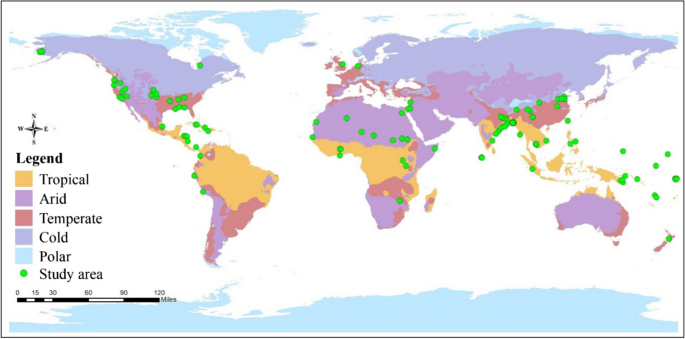

Climatic disasters are displacing millions of people every year across the world. Growing academic attention in recent decades has addressed different dimensions of the nexus between climatic events and human migration. Based on a systematic review approach, this study investigates how climate-induced migration studies are framed in the published literature and identifies key gaps in existing studies. 161 journal articles were systematically selected and reviewed (published between 1990 and 2019). Result shows diverse academic discourses on policies, climate vulnerabilities, adaptation, resilience, conflict, security, and environmental issues across a range of disciplines. It identifies Asia as the most studied area followed by Oceania, illustrating that the greatest focus of research to date has been tropical and subtropical climatic regions. Moreover, this study identifies the impact of climate-induced migration on livelihoods, socio-economic conditions, culture, security, and health of climate-induced migrants. Specifically, this review demonstrates that very little is known about the livelihood outcomes of climate migrants in their international destination and their impacts on host communities. The study offers a research agenda to guide academic endeavors toward addressing current gaps in knowledge, including a pressing need for global and national policies to address climate migration as a significant global challenge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Climate-Conflict-Migration Nexus: An Assessment of Research Trends Based on a Bibliometric Analysis

Scales and sensitivities in climate vulnerability, displacement, and health

Lori M. Hunter, Stephanie Koning, … Jamon Van Den Hoek

Climate change-induced migration: a bibliometric review

Juan Milán-García, José Luis Caparrós-Martínez, … Jaime de Pablo Valenciano

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Population displacement can be driven by climatic hazards such as floods, droughts (hydrologic), and storms (atmospheric), and geophysical hazards such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and tsunami (Smith and Smith 2013 ). The interactions between natural hazard events, and social, political, and human factors, frequently act to intensify the negative effects of climatic and geophysical hazards, leading to political and social unrest, increased social vulnerability, and human suffering. As a consequence of these adverse effects, people migrate from their native land, causing stress, uncertainty, and loss of lives and properties. However, such migration can also have positive impacts on migrants’ lives. For example, migrants may be able to diversify their livelihood and have greater access to education or healthcare.

In 2020, 30.7 million people from 149 countries and territories were displaced due to different natural disasters. Among them, climatic disasters were solely responsible for displacing 30 million people within their own country, with the highest recorded displacement occurring in 2010 when 38.3 million people were displaced (IDMC 2021a ; IOM 2021 ). It is difficult to estimate the actual number of people that moved due to the impacts of climate change (Mcleman 2019 ), because peoples’ migration decisions are triggered by a range of contextual factors (de Haas 2021 ). Nevertheless, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) states that approximately 283.4 million people were displaced internally between the years 2008 and 2020 because of climatic disasters across the globe (Table 1 ). This number represents almost 89% of the total disaster-induced displacement that occurred during this timeframe (IDMC 2021a ).

People who move from their homes due to climate-driven hazards are described in a range of ways, including climate migrants, environmental migrants, climate refugees, environmental refugees, and so on (Perkiss and Moerman 2018 ). The process of migration related to climate-driven hazards is variously described as environmental migration, environmental displacement, climate-induced migration or climigration (Bronen 2008 ).

In this research, we focus on climate-induced migration more specifically induced by slow-onset climatic disasters (sea-level rise, drought, salinity etc.), rapid onset extreme climatic events (storms, floods etc.), or both (precipitation, erosion etc.). This study investigates how climate change-induced migration studies are framed in the existing literature and identifies key gaps in the published literature.

There is a significant ongoing debate about the links between climate change and human migration in the academic literature. Some researchers strongly believe that climate change directly causes people to move, whereas the others argue that climate change is just one of the contextual factors in peoples’ migration decisions (Laczko and Aghazarm 2009 ). Although there are scholarly opinions that call into question climate change as a primary cause of migration (Black 2001 ; Black et al. 2011 ; McLeman 2014 ), there is also evidence that climate change causes severe environmental effects and exacerbates the vulnerabilities of people that force them to leave their place of living (Bronen and Chapin 2013 ; Laczko and Aghazarm 2009 ; McLeman 2014 ).

Moreover, the relationship between the adverse effects of climate change and different types of human mobility (migration, displacement, or planned relocation) has become increasingly recognized in recent years (Kälin and Cantor 2017 ). It is assumed in general that the number of climate displaced people is likely to increase in future (Mcleman 2019 ; Wilkinson et al. 2016 ), and climate change could permanently displace an estimated 150 million to nearly 1 billion people as a critical driver by 2050 (Held 2016 ; Perkiss and Moerman 2018 ). As the number of climate migrants increases rapidly in some areas of the world (IDMC 2017 ), it is now confirmed as a significant global challenge (Apap 2019 ) and recognized as a considerable threat to human populations (Ionesco et al. 2017 ).

Climate migration has multifaceted impacts on peoples’ livelihoods. Being displaced from their home, people migrate within their own country, described as internal migration, or across borders to other countries known as international migration. Internal movements of climate migrants occur mostly to nearby major cities or large urban centers (Poncelet et al. 2010 ). Climate migrants who try to move internationally are significantly challenged by two different security problems. Firstly, they cannot live in their own homeland because of worsening climatic impacts and are forced to leave their ancestral land. Secondly, they cannot move to other countries quickly to find a safer place because, according to international law, climate migrants are not refugees and they are not supported by the UN Refugee Convention or any international formal protection policies (Apap 2019 ; Mcleman 2019 ). In this situation, they live with significant livelihood uncertainty. The United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR) recognize them as a key group that is highly exposed and vulnerable because of their circumstances (Ionesco et al. 2017 ). Hence, policy development to address complex climate migration issues has become an emerging priority around the globe (Apap 2019 ).

In order to address this global challenge, there has been growing academic and policy attention focused on regional (Kampala Convention-2009 by African Union), national (Nansen Initiative—2012 by Norway and Switzerland), and international (Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration- 2018 by United Nations) levels of climate-induced migration in recent years. Myers’s ( 2002 ) seminal article signposted environmentally driven migration as one of the most significant challenges of the twenty-first century, and later, similar assumptions were made by Christian Aid (Baird et al. 2007 ), IOM (Brown 2008 ), and Care International (Warner et al. 2009 ). Such predictions led to a proliferation of the academic discourse on migration, focused on national and international security, policy frameworks, and human rights (Boncour and Burson 2009 ). Other studies have focused on vulnerability assessment, risk reduction, adaptation, resettlement, relocation, sustainability, and resilience, considering pre-, during and post-disaster circumstances of climate migration (Bronen 2011 ; Bronen and Chapin 2013 ; IDMC 2019 ; IOM 2021 ; King et al. 2014 ).

This research contributes to the discourse by identifying the gaps in the published literature regarding climate migration. A systematic literature review was undertaken to shed light on the current extent of academic literature, including gaps in knowledge to develop a climate migration research agenda. Two notable review papers provided a solid foundation for this endeavor. First, Piguet et al. ( 2018 ) developed a comprehensive review of publications on environment-induced migration from a global perspective based on a bibliographic database—CliMig. Their detailed mapping of environmentally induced migration research focused on five categories of climatic hazards (droughts, floods, hurricanes, sea-level rise, and rainfall); however, it did not include salinity and erosion which are also climate-driven and has direct effects on internal and international migration (Chen and Mueller 2018 ; Mallick and Sultana 2017 ; Rahman and Gain 2020 ).

The second key review paper was by Obokata et al. ( 2014 ), which provided an evidence-based explanation of the environmental factors leading to migration, and the non-environmental factors that influence the migration behaviors of people. Their scope of analysis was limited to international migration and excluded other types of migration, such as internal climate-induced migration.

Although migration, or more specifically environmental migration, was occurring over many decades of the twentieth century, the IPCC First Assessment report was released in 1990, which presented the first indications of the risks of climate change-induced human movement (IPCC 1990 ). This milestone report then stimulated the academic discourse, and consequently, a rapid increase in climate migration publication resulted. For this reason, the current study undertook a systematic review of literature across three decades beginning in 1990 and ending in 2019. This study aims to understand how the published literature has framed the climate-induced migration discourse. This paper identifies the key gaps in existing scholarship in this field and proposes a research agenda for future consideration on current and emerging climate migration issues.

In the following section, we outline the systematic review method and identify how journal articles were searched, selected, reviewed, and analyzed. In the next section, we present the results of this study. Results are organized into four subsections that illustrate the reviewed literature in the following ways—spatial and temporal trends, disciplinary foci, triggering forces of migration, and other key issues. Finally, we conclude by identifying research gaps, addressing the limitations of this study, and presenting a research agenda.

Methodology

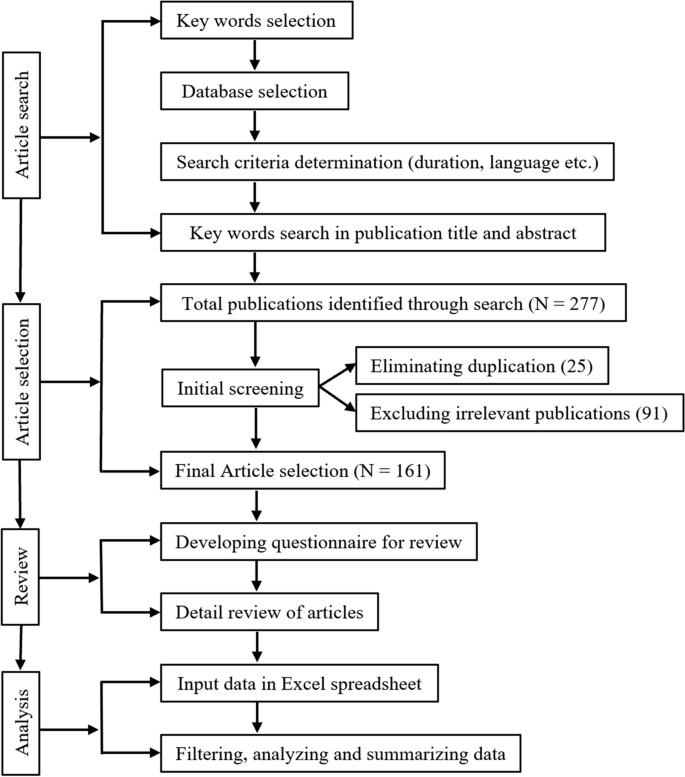

We have adopted a systematic review methodology for this study because it provides an …overall picture of the evidence in a topic area which is needed to direct future research efforts (Petticrew and Robert 2006 ). Systematic reviews reduce the bias of a traditional narrative review, although it is challenging to eliminate researcher bias while interpreting and synthesizing results (Doyle et al. 2019 ). It also limits systematic bias by identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing all relevant studies to answer specific questions or sets of questions, and produces a scientific summary of the evidence in any research area (Petticrew and Robert 2006 ). Moreover, systematic reviews effectively address the research question and identify knowledge gaps and future research priorities (Mallett et al. 2012 ). We have adopted this approach following the methodology developed by Berrang-Ford et al. ( 2011 ) which was tested in the field of environmental and climate change studies, with measurable outcomes. We have conducted the review following these four steps—article search, selection, review, and analysis (Fig. 1 ).

Systematic review flowchart

Article search

We conducted a comprehensive literature search to identify the published academic literature on climate-induced migration to develop a clear understanding of this field of study. We identified sixteen commonly used keywords to search for articles that are predominantly used in the literature. ProQuest central database was selected and used in consultation with a skilled subject librarian to search for the relevant articles for this study. We conducted this literature search in July 2019 using the key thesaurus terms, presented in Table 2 . All keywords were then searched individually in the publication’s title and abstract. We only considered English language peer-reviewed articles for this study, published between the years 1990 and 2019 (up to June).

Article selection

The main purpose of this process was to ensure the selection of appropriate literatures for further analysis. We approached the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA), a systematic evaluation tool, which was also used by Huq et al. ( 2021 ). In stage one of the selection process, 277 articles were counted based on our search criteria. In stage two, we excluded 25 duplicates, and 252 articles remained for further assessment. In the third and final stage of the detailed assessment of each paper, we identified a further 91 publications that were not relevant to our study but appeared in our searched list because search terms were briefly mentioned in their title and/or abstract without being described in further detail. As these articles did not fit with the aim and content of this research, we excluded those 91 and selected a final 161 articles for this study.

Article review