This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

Advertisement

A Literature Review of Pandemics and Development: the Long-Term Perspective

- Original Paper

- Published: 27 January 2022

- Volume 6 , pages 183–212, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Beniamino Callegari ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5513-7299 1 , 2 &

- Christophe Feder ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1239-513X 3 , 4

6360 Accesses

13 Citations

7 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Pandemics have been a long-standing object of study by economists, albeit with declining interest, that is until COVID-19 arrived. We review current knowledge on the pandemics’ effects on long-term economic development, spanning economic and historical debates. We show that all economic inputs are potentially affected. Pandemics reduce the workforce and human capital, have mixed effects on investment and savings, but potentially positive consequences for innovation and knowledge development, depending on accompanying institutional change. In the absence of an innovative response supporting income redistribution, pandemics tend to increase income inequalities, worsening poverty traps and highlighting the distributional issues built into insurance-based health insurance systems. We find that the effects of pandemics are asymmetric over time, in space, and among sectors and households. Therefore, we suggest that the research focus on the theoretical plausibility and empirical significance of specific mechanisms should be complemented by meta-analytic efforts aimed at reconstructing the resulting complexity. Finally, we suggest that policymakers prioritize the development of organizational learning and innovative capabilities, focusing on the ability to adapt to emergencies rather than developing rigid protocols or mimicking solutions developed and implemented in different contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship and small businesses

Maksim Belitski, Christina Guenther, … Roy Thurik

The impact of climate change on migration: a synthesis of recent empirical insights

David J. Kaczan & Jennifer Orgill-Meyer

Why Do Some Countries Develop and Others Not?

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

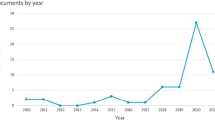

As the COVID-19 emergency appears to slowly and unevenly recede in the wake of medical breakthroughs and the development of more effective prevention and treatment protocols, the question of the long-term impact of the pandemic grows more urgent. There is little doubt that this global health crisis found economists mostly unprepared, as the analysis of the pandemic’s effects has hardly found its way into the discipline’s most central publication avenues (Noy and Managi 2020 ). However, this does not mean that the economic analysis of pandemics is starting from scratch, as economists and economic historians have never ceased to expand our knowledge on the subject.

The connection between pandemics and economic theory has historically been so relevant that it has directly contributed to labeling economics as the ‘dismal science’. Cipolla ( 1974 ) illustrates how reflections on the plague and its consequences led many scholars to develop Malthusian ideas on the complex long-term relationships between population growth, economic growth, and diseases, well in advance of the Essay on the Principle of Population (Malthus 1798 ). However, the Industrial Revolution and the concomitant development of medical knowledge led to a decreased incidence of catastrophic plagues in the West, and a corresponding decline in the interest in pandemics on the part of economists (Easterlin 1995 ). The demographic boom of the West and the visible lack of corresponding pestilence and famine further discredited Malthusian perspectives, leading to a disconnection between the demographic and economic disciplines. Furthermore, from 1900 to 2019, pandemics were either eclipsed by more disruptive events or had a relatively limited economic impact (Garrett 2008 ; Lee and McKibbin 2004 ; Noy and Managi 2020 ). Finally, the marginalist revolution greatly focused economists’ attention on purely economic elements, eliminating from the discipline those elements perceived as spurious, like the study of pandemics’ effects (Schumpeter 1954 ), relegating it to a debate of mainly historical interest.

The expansion of economic analysis beyond its traditional boundaries that has occurred in the last two decades has gradually re-included the consequences of pandemics within economic theory, although most contributions remain on the periphery of academic debate and are relatively hidden (Arora 2001 ; Dunn 2006 ; Weil 2014 ). As Noy and Managi ( 2020 ) observed, the inherently multidisciplinary nature of pandemics, combined with its poor fit with what are called “hard” methods, have both conspired to make the contribution made by economists to the analysis of pandemics modest. The efforts of economists have been greatly augmented by the continuous work done by economic historians to understand the impact of past pandemics on the long-term development of various socioeconomic systems. Yet, while the total contribution to the economic analysis of the long-term impact of pandemics is significant, it is scattered across different journals, disciplines, academic approaches, and debates, making a review work necessary in order for all these contributions to become accessible.

This paper reviews the long-term economic effects of pandemics, defined as health shocks arising from infectious diseases with global diffusion. Within the definition of long-term effects, we include both those mechanisms that are immediately present and persist for a significant amount of time and those effects that arise in the long term. Due to the focus of our analysis, transient short-term effects are not part of our study. To the best of our knowledge, few literature reviews have studied the connection between pandemics and economic development. Bleakley ( 2010 ) critically reviews how diseases, rather than pandemics specifically, affect human capital formation and income growth at the micro and macro levels. Costa ( 2015 ) describes how health improvements affect economic growth, with a specific focus on the US, concluding that improved health is not sufficient to foster growth. Finally, Boucekkine et al. ( 2008 ) formally analyze how and which growth models are better able to mathematically describe the epidemics’ effects. Moreover, some scholars have also reviewed the long-term economic effects of particular health shocks, like the preindustrial epidemics (Alfani 2021 ), Spanish flu (Beach et al. 2021 ), HIV (Gaffeo 2003 ; Zinyemba et al. 2020 ), and modern pandemics (Bloom et al. 2021 ). We differ from these works because we analyze the long-term impact of pandemics in general on economic development. A similar approach has been adopted by Gries and Naudé ( 2021 ) and Callegari and Feder ( 2021a ), but with an entrepreneurship and not a macroeconomic focus.

Our broad approach has led us to review a large number of studies in order to identify recurrent results across very different pandemic events. Pandemics could affect aggregate demand, aggregate supply, and productivity growth (Basco et al. 2021 ; Dieppe 2021 ; Guerrieri et al. 2020 ; Jinjarak et al. 2021 ; Rassy and Smith 2013 ; World Bank 2020 ). Recalling the Solovian framework, we divide the long-term pandemic economic effects into three categories: labor and human capital; investments and physical capital; and knowledge and innovation. We find that all productive inputs are affected in the long term by the pandemic. More specifically, labor and human capital are negatively affected directly by health shocks. However, the intensity of this effect is heterogeneous among countries, labor markets, and industries. Investments and physical capital are affected by pandemics through complex, interacting, and often contrasting mechanisms, leaving long-term effects ambiguous and usually marginal and non-linear. However, the asymmetric impact of pandemics on the capital market and household income leads to the poverty trap and highlights the weakness of the health insurance system in coping with these shocks. Finally, pandemics could positively affect innovations in public and private institutions and bring about relevant technological changes in industries. The scope and direction of these socioeconomic changes appear to mediate the long-term effects of pandemics, determining both their direction and scope. However, relevant and radical institutional changes are necessary if the impact of pandemics on development is to be positive. We therefore suggest that scholars should develop meta-analysis to understand the complex tapestry of long-term pandemic mechanisms. Many policy implications follow directly: an efficient public intervention must be characterized in the long term by flexibility, pro-market orientation, and design customization.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 explains the selection methodology used in the review. Sections 3 , 4 , and 5 describe, respectively, the long-term effects of pandemics on: labor and human capital; investment and physical capital; and knowledge and innovation. Section 6 critically discusses the survey and summarizes the main lessons drawn from the literature for researchers and policymakers. Section 7 concludes.

Methodology

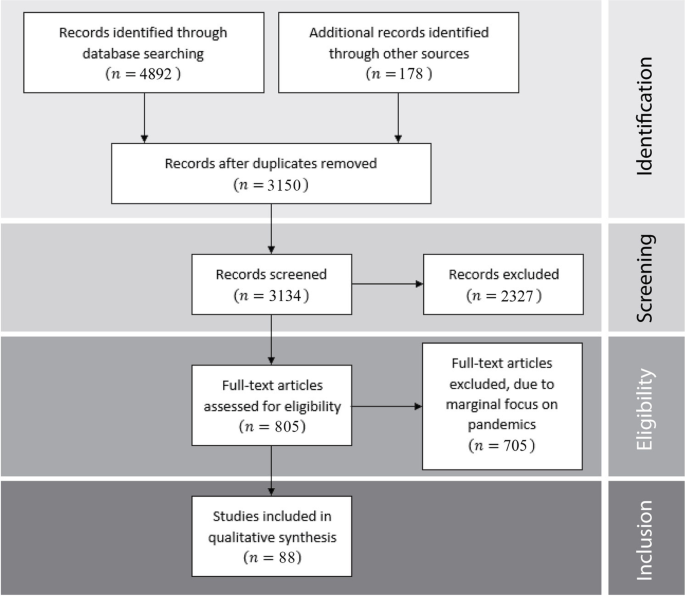

This literature review aims to illustrate, compare, and discuss the mechanisms through which pandemics affect long-term economic development. To achieve this goal, we adopted the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology (Moher et al. 2009 ). First, we defined a list of keywords that express the main aspects of the “pandemic” and “economic development” concepts. Second, we identified which data sets to search: JSTOR, IDEAS/RePEc, Google Scholar, and EconLit. We excluded working papers and unpublished articles from our search, to ensure that the mechanisms presented are accepted by the scientific community. Moreover, we restricted our focus to the fields of economics and economic history, to ensure the economic relevance of the mechanisms described. Finally, we excluded papers focused on the COVID-19 pandemic, as it is too early for a comprehensive evaluation of its long-term effects. Applying these criteria, we obtained a first sample of more than 4800 potential articles. Important contributions were not missed due to excessively strict methodological adherence, we also parsed the references lists of the most influential contributions within our initial corpus, identifying in this way 178 additional relevant manuscripts to potentially include in our review.

From this corpus of potential articles, we operated a further selection by analyzing their abstracts and, in uncertain cases, by searching the main body of the paper concerned for evidence of relevant discourse, thereby identifying 805 potential contributions. We then proceeded to evaluate the selected articles for inclusion according to their relevance to our research topic and their relative originality, evaluated in terms of the mechanisms analyzed. We then proceeded to summarize the resulting papers according to their research questions and aims, their theoretical references, their methodology, and their results, focusing on the featured economic mechanisms, in order to identify the structure of our corpus in terms of the main debates, the empirical object of study, the methods applied, and the theoretical foundations. In this way, after eliminating redundant contributions, we selected 88 articles, each describing specific mechanisms through which pandemics may affect the economic system in the long term. Finally, we identified a criterion to organize the resulting mechanisms, inspired by the well-known Solovian model of long-term growth, dividing them into the following three broad categories: labor, capital, and innovation.

We then identified a corpus of high-quality contributions, each offering a specific contribution to the academic debate in terms of one or more relevant mechanisms, supported by either theoretical or empirical arguments. Figure 1 summarizes the main steps of the selection process by using a PRISMA diagram.

The PRISMA process

Labor and Human Capital

The most intuitive and direct effect of pandemics is the adverse shock to the population and the labor market. Delfino and Simmons ( 2005 ) propose a Lotka-Volterra model showing that a negative demographic effect could become persistent if the pandemic is not eradicated. The magnitude of this effect is, however, mediated by contextual factors. Alfani ( 2013 ) shows that, in southern Europe, the plagues of the XVII century had higher mortality and territorial pervasiveness compared with those affecting northern Europe in the same period and the southern Europe plagues of the previous century. Furthermore, the rate of mortality and territorial pervasiveness was heterogeneous among Italian regions and cities. Using a long-term perspective, Rodríguez-Caballero and Vera-Valdés ( 2020 ) find that pandemics reduced the unemployment rate persistently from 1854 to 2016 in Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, the UK, and the US. They also observe that, in the UK, pandemics reduced the GDP per capita over 1270–2019, and that this effect was increasingly persistent in the last 300 years. Fiaschi and Fioroni ( 2019 ) have built a model which shows how pandemics’ impact on growth trajectories is mediated by the production structure and the mortality reduction brought by technological progress. Bloom and Sachs ( 1998 ) observe that the mortality and morbidity of pandemics are highest in tropical regions. They explain that differences in climate and nature, together with anthropomorphic factors, affect the spread of the virus over the population. However, this direct effect on labor and population could decline in the long term.

The long-term effects of pandemics on the labor supply also depend on their impact on fertility. By analyzing 15 relevant infectious diseases from 75 countries between 1940 and 2000, Acemoglu and Johnson ( 2007 ) find that pandemics reduce demographic equilibria in the long term through their impact on fertility rates. Birth rates are influenced directly, as the pandemic reduces the number of fertile women, and indirectly, as future life expectancy influences decisions to have children in the long term. They empirically confirm that the higher mortality of those affected by infectious diseases sharply reduces births and slightly reduces the share of the young in the population because of their lower life expectancy. Lorentzen et al. ( 2008 ) show that a pandemic affects not only fertility, i.e. the number of births, but also the net fertility, i.e. the fertility of the surviving population. Parents care about the number of surviving newborns: higher infant mortality increases births. Moreover, parents invest time and money in their children, who become irreplaceable when they grow up. Therefore, higher adult mortality increases fertility, even more than infant mortality. Finally, given the family budget constraint, parents must choose between the quantity and quality of their children. Consequently, the uncertainty of the pandemic reduces the investment rent in human capital, leading parents to rationally prefer quantity to quality. The authors find empirical support for these hypotheses, observing that the probability of contracting malaria negatively affects adult and infant life expectancy, and that both expectations improve the fertility rate.

Fertility mechanisms interact with human capital accumulation. Lagerlöf ( 2003 ) describes an overlapping-generations model where adults confront the children’s quality-quantity trade-off. Infant survival is negatively affected by both the chance of random pandemics and population density, which both increase the risk of contagion, but is positively affected by human capital (higher medical knowledge), which is cumulative in time and positively affected by population density (knowledge spillovers). They find that, when pandemics are frequent, where the decision to have children is concerned, parents prefer quantity to quality; human capital does not increase; and population density remains low. When sufficient human capital has accumulated, however, the growth path of the economy is no longer affected by new pandemic waves. Consequently, only if, by chance, pandemics do not strike for a sufficiently long time, will parents then increase their investments in future generations, thus reaching the human capital threshold necessary to achieve robust growth trajectories. Gori et al. ( 2020 ) integrate all previously described mechanisms in a three-stage overlapping-generations growth model, including adolescent, adult, and elderly agents. In this model, only the elderly are sexually inactive and are, therefore, not exposed to HIV infection. The probability of dying from the pandemic is negatively associated with human capital endowment and positively associated with the number of virus-spreaders. The pandemic increases both infant and adult mortality. Adult mortality reduces both labor supply and life expectancy. If life expectancy is reduced below a certain threshold level, parents prefer to have more children; otherwise, they prefer to invest in human capital. Parameterizing the model for the Sub-Saharan African countries, Gori et al. ( 2020 ) find that HIV reduces labor supply and human capital but increases fertility. Cervellati and Sunde ( 2015 ) model an economy where parents confront the children’s quality-quantity trade-off, given the child mortality and the inborn ability of the offspring. Also in this model, higher human capital leads to an improvement in both medical care and adult life expectancy: intensive economic growth follows an initial quasi-stagnation. Cervellati and Sunde ( 2015 ) observe, like Lorentzen et al. ( 2008 ), that adult mortality and human capital affect the economic dynamics more than fertility and child mortality. Cervellati and Sunde ( 2011 ) combine Lorentzen et al. ( 2008 )‘s life expectancy effects on mortality and fertility with the Acemoglu and Johnson ( 2007 )‘s model and find non-monotonic patterns of demographic growth. Before the demographic transition, more newborns could compensate for higher mortality, leaving the overall demographic effect ambiguous; after the demographic transition, parents prefer quality over quantity in regard to children, making pandemic demographic effects definitively negative in the long term.

A pandemic’s negative demographic impact reduces the number of available workers. However, its long-term impact is mixed. Gori et al. ( 2020 ) and Dauda ( 2019 ) provide a comprehensive literature review of the complex link between HIV and growth. They conclude that, while strong evidence exists for a negative link at the micro level, the empirical support for the macro effects is weaker. Keogh-Brown et al. ( 2010 ) find four ways in which the pandemic can affect the work supply. Death and infection of workers result in a temporary reduction of the workforce, partially persistent in the long term. However, they observe that these effects could be mitigated by migration (see also Alfani 2013 ), labor market inefficiencies (see also Bloom and Mahal 1997 ), and inventories. Using a structural econometric model of the UK to estimate the economic effects of a modern pandemic, they conclude that it would reduce production and increase firms’ costs, leading to the emergence of inflation in the long term. Voigtländer and Voth ( 2013 ) describe a model where pandemics reduce population but increase labor in the manufacturing sectors. Since the land supply remains constant, labor productivity increases, and therefore survivors’ wages are higher than they would be without the pandemic in the long term. If the welfare increase is sufficiently high, the demand for manufactured goods increases trade and population density. Moreover, manufactured goods are easily taxable, thus enabling the financing of more wars. All these mechanisms increase the transmission of disease, leading to long-term demographic stagnation. Using data on the Black Death, the calibrated model correctly approximates the growth of both the European urbanization and per capita GDP from 1000 to 1700.

Historical research provides further support for the hypothesis. Herlihy ( 1997 ) confirms that wages and the demand for manufactured goods increased after the Plague; however, he observes higher lethality for adults than for both the young and the elderly. The Black Death first reduced the number of available workers and the length of their productive life. Additionally, the Plague took away both the skill and experience of previous workers and the parent’s investment in the education of their children. Moreover, high turnover increased labor demand, further reducing the productivity of new workers in the long term. Low labor supply increased wages, as land rents decreased. Finally, consumption grew quantitatively, shifting qualitatively towards higher-quality goods, leading to the emergence of a positive long-term impact on the real wages and welfare of the survivors. Pamuk ( 2007 ) supports all Herlihy ( 1997 )‘s results. Moreover, he finds that the great difference in economic growth between North and South Europe, which is observed only some centuries later, originates from the Black Death of the fourteenth century. Indeed, if at first the Plague increased wages across Europe, afterwards, when the population began to grow again, the real wages remained persistently higher in North Europe. The higher flexibility of institutions and guilds allowed a better economic and social response to the Black Death in the North, for example by obtaining lease contracts more advantageous for farmers, or making it easier for women to enter the labor market, and then structurally and radically changing the fertility rate and demographic trends in those countries. Alfani and Percoco ( 2019 ) produce empirical evidence that the plagues that infested Italy in the XVII century also led to long-term reductions in real wages. Indeed, although the population remained below pre-plague levels for more than two centuries, the reduction of skills (as well as of capital and technologies) was particularly large for various reasons. First, these plagues were particularly severe compared with the outbreaks in other European countries. Second, these plagues hit all population strata equally, including the poor, nobles, and bourgeois alike. Moreover, the demographic impact was not compensated by migration flows. Finally, the destruction of human capital reduced the competitiveness of the Italian economy.

Economists disagree on the intensity of the long-term effect of pandemics on the accumulation of human capital. Bleakley ( 2010 ) shows that the effect of the pandemic on schooling is uncertain due to the simultaneous decrease in both benefits (following lessons is more difficult) and opportunity costs (labor productivity is lower). Moreover, he observes that the pandemic could already have negative effects on the intellectual development of the child during gestation. Almond ( 2006 ) supports this argument using 1960–80 decennial microdata to analyze the long-term effects on those US children who were conceived during the Spanish flu. He observes that, if the mother was infected during pregnancy, then her offspring had lower educational attainment and a higher probability of being physically disabled. Both factors reduce their future wages and then increase their participation in illegal activities and, more generally, harm their socioeconomic status 40, 50, and 60 years after the pandemic. Parman ( 2015 ) resizes the effect, affirming that in the US the Spanish flu did not affect human capital in aggregate because parents redirected their investments towards older siblings. Meyers and Thomasson ( 2021 ) show that in 1916 the negative effect of polio on human capital differed between the US states and also depended on the age of students and the family income. However, the effect is usually nonlinear on age and more damaging to the richest because of the specific characteristics of polio.

The relationship between pandemics and human capital accumulation has been studied not only in the US. Odugbesan and Rjoub ( 2019 ) show that, for 26 sub-Saharan African countries from 1990 to 2016, the link between a pandemic and human capital is negative and bidirectional due to persistent short-term effects. Using two Tanzanian databases, Wobst and Arndt ( 2004 ) show that the HIV pandemic has decreased human capital (and then wages and income per capita) in at least four ways. First, the pandemic has directly and persistently reduced labor supply and skills availability. Second, the number of teachers has also decreased, worsening the quality of the process of accumulation of human capital. Third, the lower labor supply has increased the demand for new workers, raising the opportunity cost of education for the young, thus reducing the need for human capital investments. Finally, the pandemic has also reduced the long-term demand for education through an increase in the number of orphans. Novella ( 2018 ) confirms the last link using a Zimbabwean survey for 2007–8. This revealed that orphans leave (secondary) school early and hence enter the labor market early compared with non-orphans. The worst effects emerge when both parents are dead or when the household is blended, i.e., when orphans and non-orphans live together. He also observes that this lower household income after a parent’s death only partially explains the lower investment in the orphans’ human capital. Evans and Miguel ( 2007 ) extend previous results for Kenya. Analyzing an extensive database of over 20,000 children, they observe that not only are orphans more likely to quit primary school, but the probability is higher in those cases where the mother dies and/or their academic performance was already weak. Therefore, they conclude that the inability to pay school fees and the need to find work seem less significant in the long term than the lack of emotional support and the presence of psychological trauma. Fortson ( 2011 ) models the schooling decision that maximizes the expected present value of lifetime utility, considering that HIV reduces its discount rate. He uses data of 15–49-year-olds covering the birth cohorts 1952–91 in 15 sub-Saharan African countries in order to confirm that HIV reduces longevity and human capital investments persistently in the long term. Moreover, the author suggests that both orphans and non-orphans are affected by pandemics, and that decreased schooling provision does not play a key role. Many scholars have analyzed the effects of HIV on educational achievements. Bell and Gersbach ( 2009 ) confirm all previous results by using an overlapping-generations model where both parents and children decide how much to invest in human capital. Moreover, they observe that (i) selective health and educational policies are more effective than comprehensive ones; and (ii) simultaneous health and educational policies are more (less) efficient than sequential ones if disease mortality is above (below) a threshold level.

Young ( 2005 ) combines two fertility effects with the orphan effect. First, if the virus is sexually transmitted, e.g. by HIV infection, then unprotected sexual activities and births are reduced. Second, the labor supply contraction, induced by the pandemic, improves wages and then reduces the mothers’ fertility. Third, lack of parental guidance reduces the human capital of orphans. These emerging long-term effects are mixed. Calibrating the model with South African microdata, he finds that: the female labor supply is more elastic than the male labor supply; fertility effects always prevail in the long term despite pessimistic assumptions; and per capita income tends to increase. Some scholars find that, in addition to human capital, pandemics depress other types of intangible capital. Aassve et al. ( 2021 ) show that the Spanish flu decreased social capital for many generations in the US. They use a long-term social trust survey and discover that: (i) the immigrants born after the Spanish flu and their heirs have lower social trust than those born before; and (ii) the effect is higher for those from countries with less uncensored information on pandemic effects. Using a behavioral experiment in Uganda, McCannon and Rodriguez ( 2019 ) find that grown-up orphans tend to have lower social capital. The probability of prosocial behavior is lower because orphans are more pessimistic about the community’s social contributions. McDonald and Roberts ( 2006 ) analyze data for 112 countries from 1960 to 1998 to determine how much HIV and malaria affect health capital and, consequently, income per capita growth in the long term. They observe that the degree of HIV prevalence in a country negatively affects health capital directly and economic growth indirectly. Moreover, they observe that this mechanism is significant in Africa, through both HIV and malaria, and in Latin America, only through HIV, but not in OECD and Asian Countries. Focusing on sub-Saharan Africa, Odugbesan and Rjoub ( 2019 ) confirm that income plays a key role in explaining the long-term effects of a pandemic. However, the direction of their results is reversed: the bidirectional link between a pandemic and human capital for upper-middle-, low-middle-, and low-income countries is, respectively, negative, positive, and insignificant.

Finally, the majority of effects described in this section are generally more severe in low-income countries. Here, reduced access to medical care, undernourishment, and the presence of other diseases could induce a poverty trap (Beach et al. 2021 ; Bloom et al. 2021 ; Lorentzen et al. 2008 ). A Malthusian equilibrium with low income, underinvestment in schooling and health, and high fertility emerge for tuberculosis (Delfino and Simmons 2005 ) but only partially for malaria (Bloom and Sachs 1998 ; Gallup and Sachs 2001 ). Moreover, the poverty trap is unclear for HIV, where both positive and negative pandemic effects on income distribution could emerge (Bloom and Mahal 1997 ; Bloom and Sachs 1998 ; Mahal 2004 ). Alfani ( 2021 ) suggests that high-mortality pandemics, like the plague, could reduce poverty by either exterminating the poor or redistributing income to the poor. Vice versa, Karlsson et al. ( 2014 ) suggest that low-mortality pandemics, like the Spanish flu, increase poverty due to pandemic-induced unemployment, inability to work for long periods, and general loss of income. As these effects are particularly severe and persistent for poor households, pandemics could aggravate inequality. Therefore, the long-term effects of pandemics on income distribution appear to depend on the medical profile of the disease.

Investments and Physical Capital

While pandemics affect the long-term dynamics of labor supply and human capital also through durable short-term mechanisms, their impact on capital and savings arise in the long term specifically. Acemoglu and Johnson ( 2007 ) argue that, since land and physical capital are not affected in the short term, the lower levels of labor supply and human capital reduce GDP but have an unclear effect on per capita income. Since pandemics reduce GDP and income growth, they also reduce physical capital accumulation, thereby triggering a long-term negative loop between GDP and capital. The authors hypothesize that, in the long term, GDP per capita should drop in high-income countries but not in low-income countries, where land is more relevant than physical and human capital, and the negative loop effect is weaker.

Bai et al. ( 2021 ) confirm that the long-term pandemic effect differs among countries. They show that infectious diseases in the last 15 years have increased permanent volatility in the US, UK, China, and Japan capital markets. However, public policies of correct timing and intensity could reduce the effect. Ru et al. ( 2021 ) find that countries that have already experienced similar pandemics react better and more readily to future pandemics, especially if past pandemics have led to deaths. Analyzing the 65 largest financial markets in the world, the authors note that countries with firsthand SARS experienced the deepest fall in the stock market during the COVID-19 pandemic. This reaction is positively correlated to the pandemic’s mortality. Donadelli et al. ( 2017 ) confirm that, from 2003 to 2014, disease-related news had adversely affected the returns of the pharmaceutical stock market. Analyzing 102 pharmaceutical firms listed on the US stock market, the authors note that investors were too optimistic about the future liquidity of pharmaceutical sector flows after the shock. This irrational behavior has a positive and persistent effect on the returns of the pharmaceutical stock portfolio. Cakici and Zaremba ( 2021 ) extend the previous results outside the pharmaceutical sector. They observe that pandemics induce irrationality among investors, impacting assets across countries and firms heterogeneously. Analyzing 19 international stock markets, they observe that the stock trend signals to investors the firms’ resilience and ability to react to negative shocks, leading to increased future share performance. Summarizing, the literature analyzing the effects of pandemics on equity markets concludes that these health shocks induce irrational behavior of investors, causing positive and negative long-term effects, heterogeneous among countries, sectors, and firms.

Consensus among scholars is lacking in regard to both the size and direction of the long-term pandemic effects on investments and physical capital. Cuddington ( 1993a ) observes that pandemics affect labor demand and capital markets. The total effect on wages is uncertain: supply shock increases wages, but the demand shock reduces them, because infected workers are less effective, as they need to take sick leave and are less productive. Pandemics also affect domestic capital accumulation because health care costs reduce savings. Therefore, the total impact on capital per capita, GDP, and GDP per capita is uncertain; however, calibrating the model with Tanzanian data, he finds that both GDP and GDP per capita sharply decreased from 1985 to 2010. Cuddington and Hancock ( 1994 ) confirm the result for Malawi, although the lower number of infected people reduced the long-term effects on the economy. Moreover, Cuddington (Cuddington 1993b ) observes that previously predicted effects also hold when formal and informal productive sectors coexist, and formal wages are sticky. Basco et al. ( 2021 ) affirm that the Spanish flu in Spain was primarily a demand shock but confirm that the pandemic impact on the real return of capital is ambiguous in the long term. Although at the theoretical level Karlsson et al. ( 2014 ) confirm the ambiguity of the long-term effect of the Spanish flu on the per capita return on capital, this ambiguity is not observed in the empirical analysis of the Swedish counties. Indeed, by analyzing the effects in the decade following the pandemic, the authors estimate no statistically significant effect on earnings per capita, but clear negative effects emerge on capital returns per capita. Finally, Jinjarak et al. ( 2021 ) show that the H3N2 pandemic reduces GDP, consumption, and the investments of 52 countries.

Other scholars demonstrate that the effect of pandemics is heterogeneous among sectors, a trait shared with most disasters (Halkos and Zisiadou 2019 ). In Egypt, pandemics depleted the rural workforce necessary for the maintenance of the crucial centralized irrigation system, which remained in a state of disrepair, hampering the well-being of the region for centuries (Borsch 2005 , 2015 ). Herlihy ( 1997 ) shows that the rise in wages following the Black Death increased demand for more nutritious and elaborate goods, diversifying consumption and improving welfare. Similarly, Pamuk ( 2007 ) shows that the Plague increased the demand for luxury goods in particular. Moreover, he observes a reduction in interest rates and increased investments, although with asymmetric components. Indeed, Alfani ( 2013 ) shows that the XVII century plague depressed Italian industries, in particular, the wool, flax, silk, and construction sectors, due to the loss of skills and the impossibility of procuring raw materials. Alfani and Percoco ( 2019 ) highlight that the shift of investments from urban to rural activities in this period reoriented the post-plague Italian manufacturing sector towards the production of semi-finished and low-quality goods. Summarizing, scholars observe that short-term changes in the relative composition of both demand and supply structures can lead to long-term sectoral effects.

Similar sectoral asymmetric effects have been recorded for more recent pandemics. Analyzing the potential effects of SARS in Asia, Lee and McKibbin ( 2004 ) find that countries specializing in trade and the tertiary sector are more damaged by both temporary and persistent pandemic shocks. Indeed, in these sectors, close contact with other people is often necessary. The retail and tourism sectors are particularly vulnerable. Gallup and Sachs ( 2001 ) provide further support by showing that Mediterranean and Caribbean countries benefited from the rapid and stable development of the tourism industry after the eradication of malaria. Finally, Mahal ( 2004 )‘s literature review on HIV effects shows a similar, although weaker, effect for sub-Saharan tourism. Moreover, the author shows that health, transport, and the primary sectors are also negatively affected by HIV. Pandemics affect the health sector by increasing costs for healthcare services and insurance. Moreover, he shows that workers in the transport and primary sectors belong to the social classes most affected by HIV. Oster ( 2012 ) finds that export is an essential explanation of the spread of HIV in Africa because more truckers and miners, among others, stay away from home for more extended and more numerous periods. As a result, they and their partners are more likely to engage in risky sexual intercourse, putting themselves and their stable partners in danger. She also affirms that trade could further aggravate the effect in the long term, as additional income could increase the amount of money spent on prostitution, or mitigate it, if money is spent on preventive measures. Using a quasi-experimental variation, Adda ( 2016 ) confirms that the new transportation networks and inter-regional trade accelerated disease diffusion in France from 1984 to 2010. Delfino and Simmons ( 2005 ) combine the effect of capital and labor, using a Lotka-Volterra predator-prey model where only healthy individuals are productive. The authors observe that the introduction of capital makes the path more complex, but that the economy still cyclically converges to a stationary equilibrium. Indeed, when labor supply decreases, GDP decreases. Therefore, both savings and investments are lower, and GDP per worker also decreases. Lower welfare reduces health services consumption, but the impact on the disease transmission is uncertain: it increases as the share of infected rises, but it decreases as the contagion period became shorter. When the labor supply increases again, the cycle restarts. Augier and Yaly ( 2013 ) show that complex growth paths could emerge even in a model where the pandemic affects only capital accumulation. The authors describe an overlapping-generations model where the pandemic increases premature deaths, and then only the survivors will use savings previously accumulated. The government proposes a funds system that redistributes rents among the survivors. Young people must decide how much to invest in this public fund, and how much to spend on health or other goods, knowing that better health reduces the chance of dying prematurely. They observe that the pandemic, capital, and health investments are linked in an articulated and recursive way: (i) the pandemic causes health investment to drop; but (ii) health investment reduces the diffusion of the pandemic; (iii) capital directly affects the investment; and then (iv) it indirectly affects the spread of the pandemic. Therefore, the economy converges to a long-term equilibrium only when contagion rates are low. Finally, Stiglitz and Guzman ( 2021 ) show that pandemics act as an unanticipated technology shock, generating unemployment that government intervention can effectively counteract. In the long term, uncertainty does not decline, thus further increasing the desirability of government intervention.

In Section 3 , we showed that, after a pandemic, life expectancy decreases because a healthy lifespan becomes more uncertain than before, leading to decreased investments in human capital. Similarly, scholars observe that the pandemic also reduces investments in physical capital. Lorentzen et al. ( 2008 ) show that the indirect effects of malaria on life expectancy are higher on physical rather than on human capital investments. Analyzing different databases and case studies, Gallup and Sachs ( 2001 ) conclude that the effects on per capita and total income are negative because both foreign investments and the revenues from tourist and business travelers are drastically lower in those countries affected by malaria. Analyzing the effects of HIV on 43 Asian countries from 1990 to 2015, Fawaz et al. ( 2019 ) conclude that investments and savings are usually inversely related to that pandemic. However, they show that both the sign and the intensity of the effect could differ depending on how far-sighted people are. Additionally, in low income countries, the negative effect of investment is independent of gender, but the pandemic affects men’s saving propensity more than women’s. Vice versa, in high income countries, when life expectancy decreases because of pandemic mortality, men save more but do not increase their investments, while women save less but invest more. Bloom and Mahal ( 1997 ) also focus on savings behavior, using it to explain the insignificant effect of HIV on the income per capita growth rate in 51 countries from 1980 to 1992. First, they observe that poor people are most affected by HIV, and that expensive medical treatments further aggravate their disadvantaged situation. However, social and economic mechanisms partially compensate for the high costs of official health services. Second, higher care costs cause both consumption and savings to drop. Moreover, lower life expectancy may increase precautionary savings in favor of surviving family members. Garrett ( 2008 ) studies the economic and social effects of the influenza pandemic 1918–9 in the US, analyzing newspaper articles and academic papers to draw lessons for modern pandemics. He observes that health care is relevant only with ideal health systems that certainly do not collapse after a pandemic, no matter how serious it is. Moreover, he concludes that, although a higher percentage of life insurance mitigates the adverse financial effects of a pandemic on households, the wealthiest households that will need it least will also be the more protected. Gustafsson-Wright et al. ( 2011 ) show that, in the case of pandemics, the private insurance system can be unfair and distortive, even in countries like Namibia, where the quality of public health care is relatively high, and most people have health insurance. The poor who cannot afford health insurance suffer from higher medical expenditure during a pandemic. There are no substantial effects on medical expenditure and family income until the virus starts affecting working capabilities; then, the economic consequences for the poorer strata worsen severely.

The comprehensive review from Hallegatte et al. ( 2020 ) confirms that poor people are disproportionately affected by natural hazards and disasters. Pandemics are no exception. Gaffeo ( 2003 ) provides additional support for the idea that pandemics can lead households into a poverty trap. Higher care costs and physical weakness reduce income capacity: for poor households, this leads to malnutrition, further reducing their physical capabilities, and increasing the pandemic’s morbidity and mortality. Physical and human capital trends reinforce this adverse and cumulative loop. Finally, he observes that pandemics worsen market failures for health insurance and local credit availability. Due to adverse selection and moral hazard, the higher uncertainty and information asymmetries inherent to pandemics lead to higher insurance premiums and reduced access to credit for the needy. Habyarimana et al. ( 2010 ) show that, while private firms could invest in their workers’ medical care, they are unlikely to do so. They describe the case of the pioneering firm Debswana Diamond Company in Botswana, which, since 2001, has invested in a program to improve the health of its workers affected by HIV. They observe that the treatment works, but the investment is unprofitable as the costs are too high, supporting the idea that African firms can only bear a small share of their workers’ health costs, if any.

While the previous literature shows that a pandemic increases income inequalities, Odugbesan and Rjoub ( 2019 ) argue that pandemics could hinder sustainable development. In this connection, these authors analyze the link between HIV and both public and private adjusted net savings, as an indicator of sustainable economic development, for 26 sub-Saharan African countries from 1990 to 2016. They show that HIV negatively and unidirectionally affects saving, and that the effect is particularly intense for upper-middle- and low-income countries. HIV also negatively affects the perception of government efficiency in low-middle-income countries. Odugbesan and Rjoub ( 2020 ) show that, for 23 sub-Saharan African countries from 1993 to 2016, the adverse relationship is bidirectional because the HIV control program and sustainable development compete for the same public spending budget. Keerthiratne and Tol ( 2017 ) show that the financial impact of disasters, pandemics included, is country- and time-specific. Moreover, Chakrabarty and Roy ( 2021 ) propose a model where the future pandemic uncertainty reduces government allocation of non-health expenditures in favor of the health ones. In 143 countries from 2000 to 2017, they found that higher-debt countries present a public misallocation and delay due to public constraints. A similar effect also emerges in low-income countries, but this is due to asymmetric information. Bai et al. ( 2021 ) show that, up to a point, the effects of pandemics could be efficiently mitigated with fiscal and monetary policies. Finally, Cavallo et al. ( 2013 ) confirm that governments and institutions could play a key role in the economic effects of a pandemic. Using a database from the Centre for Research on Epidemiology and Disasters, they observe that natural disasters, such as a pandemic, have a long-term negative economic impact only when they simultaneously cause a high number of deaths and are followed by institutional and political revolutions.

Knowledge and Innovation

Historians have identified numerous cases of pandemics being catalysts of significant, systemic change. In his comprehensive overview of the impact of the Black Death on Europe, Herlihy ( 1997 ) argues that it led to larger economic diversification, improved technology, and better lives, breaking the XIII century Malthusian deadlock by directing technological change towards the now cheaper input, i.e. capital. Although educational institutions were gravely hit, with one-sixth of European universities closed, as a long-term reaction to this short-term impact, a number of new educational institutions were built in reaction to the dearth of scholars. The new universities adopted more flexible curricula, contributing to the revival of classical studies. The need to face the Plague also forced the acceptance and diffusion of anatomical studies, fostering the development of the scientific approach in medicine. Epstein ( 2000 ) offers a similarly positive account, underlining how the Black Death brought much needed renewal. European feudalism was locked in a low-growth pattern, not because of lacking innovative capabilities, or market institutions, but rather due to the intensity of seigniorial rights, and the jurisdictional power of towns and lords, which were used to maximize the extraction of resources, mostly for military purposes, greatly hampering development. The scarcity of workforce caused by the Plague shock reduced the bargaining power of the landowner in favor of the worker. The resulting political and economic struggle is described as a process of “creative destruction”. The centralization process was greatly accelerated, leading to the consolidation of internal markets, the standardization of legal procedures and business norms, and the progressive rationalization of hierarchies. As a result, in the long term, transaction costs and economic uncertainty declined significantly, as testified by the structural decline in interest rates, which quickened the pace of innovation and trade growth. One of the long-lasting consequences of the pandemic for Europe was a more centralized, less predatory authority, able to support the process of economic development.

The institutionally “liquidationist” account of pandemics also applies to other centuries. For example, Alfani ( 2013 ) observes how plagues irrevocably affected the balance of power in Italy, favoring the rise of the House of Savoy, which eventually led to the Italian unification. Pamuk ( 2007 ) describes how the Plague created local skilled labor scarcity, incentivizing migration and fostering the dissemination of knowledge in the long term. Higher wages stimulated the substitution of land and capital for labor, creating conditions favorable to the implementation and diffusion of labor-saving innovations across all economic fields: the printing press, firearms, and high-capacity maritime transportation can all be linked to this general trend. Voigtländer and Voth ( 2013 ) offer what is perhaps the more optimistic view of the long-term impact of the Black Death, arguing that the positive impact of the persistently high European mortality rates dwarfed the effects of technological change for the entire 1500–1700 period. Clark ( 2007 ) provides a useful counterfactual, analyzing how the Far East, relatively less affected by plagues, maintained a growth regime characterized by both low income and low mortality. Not all plagues, however, are described in such a positive light.

Alfani and Percoco ( 2019 ) document the significant negative impact of the plague of 1629–30 on the long-term development of the Italian cities and the Italian economy. In addition to the mechanisms already explored in the previous sections, the authors argue that the significant losses suffered by the urban economic elite, who controlled most of the advanced manufacturing activities, caused an “ingenuity shock”, i.e. decreased both the availability and the willingness of the surviving elite to innovate in the urban industry, preferring agricultural investments instead. The latter took a dramatic hit in terms of production capabilities, which recovered only after decades. The exceptionally late recovery slowed the process of recovery and urbanization, weakening the Italian competitive position vis-à-vis Northern Europe in manufacturing. The almost uniform lack of wage increases signals how the long-term reduction in supply capabilities was not a consequence of lacking a skilled workforce, but rather a significant long-term change in the pattern of capitalist investments. This argument is important to underline how general, systemic renewal might encompass significant relative changes. The hypothesis that the plague did not damage, and perhaps even fostered, European development as a whole, is entirely consistent with the description of significant short- and long-term harm being wrought to large sections of the continental socioeconomic system. This is also consistent with Pamuk ( 2007 )‘s description of the divergence between North and South Europe, which emerged in response to the Plague as a consequence of the greater entrenchment of Southern political and economic elites, and the associated slower degree of institutional flexibility and, consequently, innovation and knowledge diffusion. In his recent overview of the subject, Alfani ( 2021 ) provides further evidence for the relevance of institutional change and policy choices on the long-term impact of pandemics on economic distribution and growth, illustrating how pandemics create opportunities for institutional change while also creating issues that, if not effectively tackled, can severely worsen the economic conditions of the poorer sections of the population.

On the negative side of the debate, Bar and Leukhina ( 2010 ) argue that epidemics have the capability to disrupt knowledge transfer across generations, leading to significant reductions in total factor productivity growth over time. They show that the long-term loss is moderated by the possibility of knowledge diffusion from regions that were spared negative health shocks, implying that the scope of this negative mechanism would be much greater in the case of a pandemic. Karlsson et al. ( 2014 ) document the impact of the Spanish flu on the Swedish economy, finding a long-term negative effect on capital income and a positive effect on the rate of poverty, both possibly driven by a significant persistent loss of skilled workers and consequently a decline in labor productivity. Jinjarak et al. ( 2021 ) show that the H3N2 epidemic can have permanent negative effects on productivity. Indeed, also when the productivity rate returns to its pre-shock level, some opportunities are lost or delayed forever, and then the innovation path will be always lower than without pandemics. Chen et al. ( 2021 ) even state that epidemics have the worst impact on innovation among natural disasters. Indeed, they affirm that epidemics reallocate public expenditure from innovation to health, reducing patent applications and innovation in 49 countries over 1985–2018. In Eastern Europe, feudal lords reacted to epidemics by re-enslaving the peasantry, greatly hampering the diffusion and implementation of new agricultural techniques, and locking the regions in a relative underdevelopment pattern called “second serfdom” (Domar 1970 ; Robinson and Acemoglu 2012 ). Similarly, the plagues affecting the Roman Empire and its successor states led to persistent socioeconomic degradation, aided by conservative political reforms introduced by the surviving elites (Duncan-Jones 1996 ; Sarris 2002 ; Little 2007 ; Harper 2016 ).

Yet pandemics are also great opportunities for the creation and diffusion of new knowledge. Bresalier ( 2012 ) documents how the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918–9 was a turning point in the modernization of British medicine, leading to the establishment of key institutions and organizations that would shape the long-term development of medical research and healthcare, chief among them the Medical Research Council. The latter led to a wider active involvement of the state in sanitary matters. In general, the author shows that the pandemic’s effects were instrumental in developing the modern medical research system. Hopkins ( 1988 ) provides a description, similar in spirit, of how the successful smallpox eradication campaign conducted by the World Health Organization led to organizational learning, and the development and institutionalization of best practices, thereby greatly enhancing global medical response and prevention capabilities. Furthermore, large shocks, such as pandemics, can create windows of opportunity for change. This is echoed by Cohen ( 2019 )‘s review of the same episode, concluding that, while research and innovation activities played a key role in ensuring the campaign’s success, these efforts were at first greatly hindered by inappropriate practices and institutional routines. Only when the involved organizations implemented new and improved procedures did technological solutions become truly effective. While the scale differs, the argument echoes Pamuk ( 2007 )‘s. Wallace and Ràfols ( 2018 ) show that the avian flu highlighted how both excellence-based funding schemes and economic interests contribute to unduly restrict the field of active research as compared with the broad range of scientific opinions offered by experts, resulting in the development of a limited selection of techniques from the available knowledge base.

Analyzing the impact on the knowledge generation of vaccination subsidies, Finkelstein ( 2004 ) observes that, apart from the direct health impact from the eradication of illnesses, higher expected profitability might lead to socially wasteful competition for market share in the long term. Empirical evidence supports the hypothesis that the outcome depends on the state of the technological frontier and market conditions, as expressed by vaccination rates. In most cases, subsidies appear to lead to purely wasteful competition, but, in the case of the flu, there is evidence of increased product quality and demand, with the associated dynamic benefits outweighing static gains. Consistently, Kremer ( 2000 ) pointed out that market failures are endemic in the markets for both vaccine provision and vaccine research. While this opens up opportunities for policy intervention, it simultaneously underlines the challenges involved in the design of truly effective instruments. Similar challenges are described by Keohane ( 2016 ), in which innovative financial practices developed in the long term as a reaction to large shocks, including pandemics. He argues that “risk transfer for disease is a vital public good that the market has not otherwise provided” (ibid,130), and that new preventive and preparedness measures could be financed through the issue of catastrophe bonds. While these catastrophe bonds are expensive, the benefits of increased resilience in the face of health shocks might be a net gain, especially if the costs are somewhat lessened by pooled funds international initiatives. Although significant overlapping exists in terms of health-crisis preparedness and the organizational capacity of response, such an approach is probably more effective for estimating regional epidemic risks. Such instruments may be particularly useful in light of Confraria and Wang ( 2020 )‘s finding of persistent radical disparity between the disease burden carried by African countries and the amount of medical research dedicated to specifically African issues relative to global efforts.

The discussion so far has been focused on mechanisms that connect pandemics to the development of knowledge and practice, and from those to their economic and financial impact. Easterlin ( 1995 ) provides an original analysis based on a different viewpoint. Analyzing the steep decline in mortality that took place in northwestern Europe in the nineteenth century, he maintains that both the industrial and the health revolutions have a common root: the ascendancy of the scientific approach leading to technological change in both areas. The argument implies, on the one hand, that economic growth is not the main driver of life expectancy improvements, and, on the other, that improvements in health and life expectancy do not have a direct effect on economic outcomes, a position compatible with the relatively weak empirical evidence available (Acemoglu and Johnson 2007 ). The cause of structural change is argued to be found in the extraordinary stream of innovations implemented during the period, supported by a swarm of Schumpeterian “entrepreneurs”, only marginally motivated by profitability. Both those revolutions were triggered by the acceleration in the accumulation of usable empirical knowledge through the establishment and diffusion of the scientific method, the difference in timing to be imputed to the difficulty of developing and implementing the scientific solution. Deaton ( 2004 ) similarly argues that knowledge transfer, in the form of both effective practices and useful information, is key for explaining different national patterns of mortality decline and life expectancy increase, pointing out how globalization could benefit developing countries in this respect.

The argument is further expanded by Easterlin ( 1999 ), who showed that, while private firms have been crucial in fostering economic development, their role in improving health and especially infectious disease control practices has been marginal at best. Indeed, the preventive measures improve life expectancy more than the therapeutic ones, but firms rarely adopt them. However, the actions of households and governments are more important for disease prevention. The role of government is especially relevant because public action is necessary for both health education and prevention programs. Easterlin shows how irreplaceable effective knowledge and healthy practices are in the process of preventing and curing diseases, but how ineffective markets, contracts, and private property institutions have been in fostering their historical development, due to a number of related market failures. In fact, medical practitioners and public servants working towards the diffusion of salubrious norms have often found themselves hindered by economic actors defending their profitable, if deleterious, business. In his account of the US development, Gordon ( 2016 ) confirms both the decisive role of scientific advances and the importance of government intervention and regulation for the drastic improvement in health and life expectancy that took place in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. However, Birchenall ( 2007 ) proposes an alternative explanation for the manifestly weak correlation between contemporaneous income growth and mortality, highlighting the significant long-term impact of income growth in terms of improved adult health and life expectancy, and subsequent mortality reduction. The argument is supported by a model illustrating how sustained economic growth, no matter the source, is sufficient to escape the Malthusian equilibrium, leading to drastically lower mortality in the process. Cervellati and Sunde ( 2015 ) provide further support by developing a model based on unified growth theory, also characterized by an inevitable take-off triggered by sufficient technological progress.

From the historical description emerges a complex interplay of negative and positive relations between health and business practices, driven by the contrast between short- and long-term interests, on the one hand, and private and public interests, on the other. This complexity is faced by Mokyr ( 2010 ) in his attempt to outline the principles of an evolutionary approach to the study of the development of useful medical knowledge. He begins by highlighting the two key idiosyncratic characteristics of such a knowledge field: the largely inelastic character of its demand, as all humans value their lives and health under all circumstances, and the relevance of negative exogenous shocks, such as the spread of pandemics. Medical knowledge maps to a set of instructions and recipes capable of guiding action, called techniques. According to context-specific selection criteria, only a subset of related techniques will actually be implemented for a given set of knowledge. While the actual usage of techniques is rival, knowledge can endlessly accumulate with only limited downsides. The evolutionary process of knowledge is mostly based on persuasion mechanisms; on the contrary, the related techniques are evaluated on their relative effectiveness. However, persistent empirical failure might not be sufficient as a selection mechanism, if no better technique is available on the basis of the socially accepted set of useful knowledge. This is particularly likely in the case of singleton techniques, based on the limited empirical knowledge that “this works”, and is therefore incapable of adaptation to sudden change. The shift towards scientific knowledge ensures that techniques are based on a more nuanced understanding of natural phenomena, enabling quicker and more efficient adaptation to exogenous shocks. Limits are provided by the path-dependency of knowledge development, which is only indirectly affected by the usefulness of related techniques. While this might result in the generation of “useless” knowledge, degrading response capacity in the present, sudden exogenous changes might lead to equally sudden revaluations. Summarizing, pandemics are a simultaneous shock to both practices and the underlying knowledge, as their often dramatic impact is sufficient to create opportunities for shifting entire development trajectories. The emergence of new knowledge and practices can be further amplified by diffuse and profound institutional change, which in turn may lead to significant upheavals, positive or negative. Owing to the complex nature of the outcomes, however, normative judgment lies beyond the capabilities of purely theoretical analysis.

The first key result of this review is that in the analysis of pandemics’ long-term economic consequences, historical and epidemiological characteristics are key (Donadelli et al. 2021 ; Meyers and Thomasson 2021 ). The extraordinary mortality associated with the Black Death is the most crucial factor in explaining its exceptional long-term consequences for European and global socioeconomic development (Pamuk 2007 ; Voigtländer and Voth 2013 ). Research on the consequences of HIV has rightly focused on its sexual transmission (Young 2005 ; Oster 2012 ; Fawaz et al. 2019 ; Gori et al. 2020 ) and the intergenerational consequences of increased mortality among working-age adults (Wobst and Arndt 2004 ; McDonald and Roberts 2006 ; McCannon and Rodriguez 2019 ). Therefore, the results offered by a general economic analysis of pandemics should be considered a wide collection of potential mechanisms, their empirical applicability and relative importance to be carefully weighed on a case-by-case basis. This does not imply that knowledge is not cumulative in this field, but rather that application of past knowledge should account for contextual factors in order to determine the likely long-term impact of a specific pandemic.

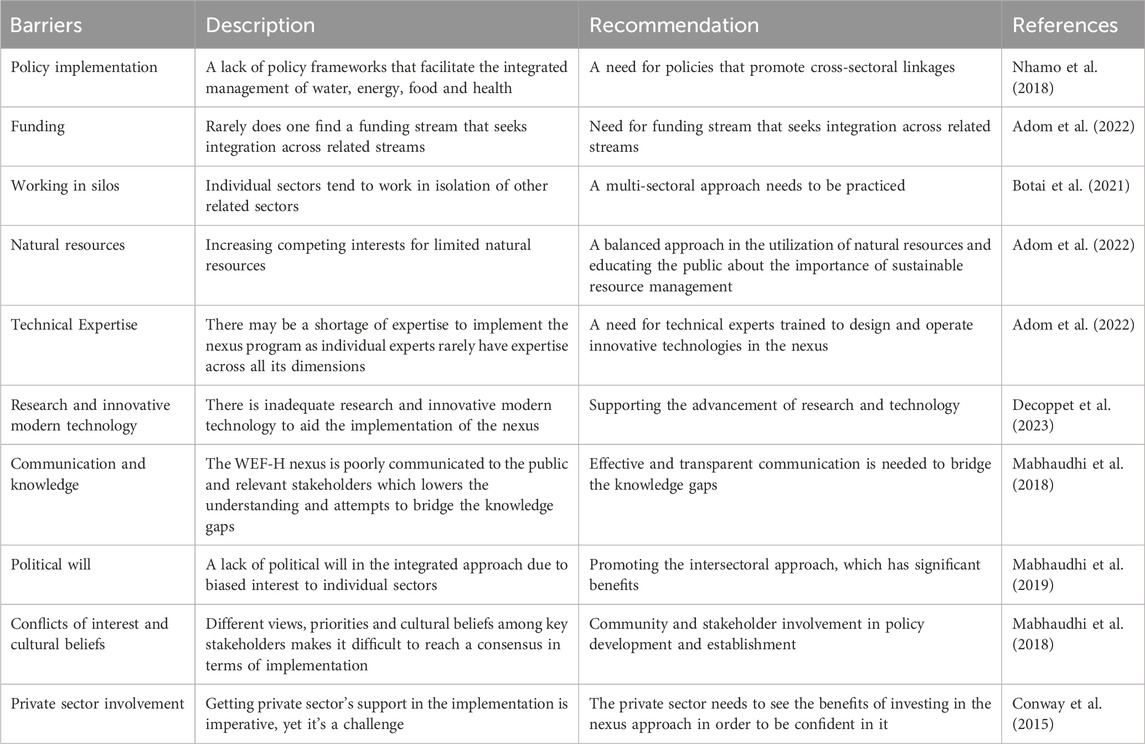

Our review of the literature goes one step further. By aggregating the pandemics by their effects on various economic factors, we observe some recurring trends, allowing some useful general conclusions to emerge. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of papers published in English focused on the relationship between pandemics and economic development. Following this paper’s structure, we organize the papers according to the mechanisms investigated into three broad categories: labor and human capital; physical capital and investments; and knowledge and innovation. We show that diseases can potentially affect all the productive factors of an economy in the long term. Most of the articles focus on the pandemic impacts on labor and human capital, all finding negative long-term impacts. However, some authors show that this effect could be partially mitigated in specific geographical areas, workers’ categories, and industrial sectors. The long-term effects on investment and physical capital are ambiguous: many papers show contrasting and complex mechanisms that do not allow us to know a priori the overall economic effects of pandemics on long-term investment trajectories. Notably, all papers which show long-term positive effects of pandemics on economic development focus on knowledge and innovation. However, negative cases also exist, leading many scholars to observe that the effect is potentially mixed, its direction dependent on necessary but not always implemented institutional changes.

The following general picture of the effects of pandemics on economic development emerges from our analysis. First, pandemics tend to reduce population and labor supply in both the short and the long term. This increases labor productivity, and therefore average wages. However, pandemics also hinder human capital accumulation, reducing productivity and per capita income growth. The negative effect is further compounded by the associated loss of knowledge, skills, experience, and innovative capabilities. Investments and savings are also negatively affected, leading to potential long-term hysteresis and the emergence of new, lower-income equilibria.

The pandemic shock can also break old patterns, opening new innovative trajectories previously inaccessible. The aggregate impact of these long-term mechanisms on the economic system is dependent on the relative relevance of, mostly harmful, adaptive mechanisms vis-à-vis potentially fruitful innovative responses. When the latter dominate the picture, negative long-term effects are overwhelmed by the benefits captured by radically new socioeconomic models of production, trade, and consumption. Therefore, the key factor determining the long-term impact of pandemics is identified with the innovation processes to which they give rise, and particularly the necessary accompanying processes of institutional change. While these effects are more difficult to capture using traditional economic methods, they are highlighted by historical analysis and should not be ignored by researchers and policymakers alike (Callegari and Feder 2021b ; Jena et al. 2021 ; Mandel and Veetil 2020 ).

Another important conclusion that can be drawn from this review is that most short-term outcomes, such as the immediate reduction in labor supply (Bloom and Sachs 1998 ; Alfani 2013 ), can bring, in the long term, significantly different consequences in both scope and quality when compared with the transient short-term effects (Delfino and Simmons 2005 ; Acemoglu and Johnson 2007 ; Basco et al. 2021 ). Several specific long-term mechanisms also emerge (e.g., Herlihy 1997 ; Young 2005 ; Augier and Yaly 2013 ), whose impact can hardly be overstated (Lorentzen et al. 2008 ; Voigtländer and Voth 2013 ). Therefore, it is unsurprising that attempts to produce comprehensive quantitative measurements of the economic consequences of pandemics appear to be affected by a significant downward bias (Lee and McKibbin 2004 ; Mahal 2004 ; Keogh-Brown et al. 2010 ). The exceptional nature of the shock brought by the Black Death of 1347–52 has obscured the economic consequences of the other late-medieval plagues, of which we know little. Lack of strong empirical evidence should be understood in the context of the complexity of the phenomena involved, and therefore not be interpreted at first sight as sufficient for falsification purposes. At the same time, however, the mechanisms at work in the most deadly pandemics should not be assumed to apply in exactly the same way to weaker, shorter, or smaller case episodes: the complexity of the phenomena under analysis cannot be reduced to a single formal model. Research on the long-term impacts of pandemics should be understood as a collaborative effort, with single researchers and teams focusing on different, yet compatible, mechanisms. A comprehensive picture can only emerge from subsequent efforts to produce cohesive overviews of the entirety of the debate rather than from a single model, no matter how ambitious.

Some lessons for policymakers also follow. The first is that, in light of the idiosyncratic characteristics of pandemics, precise and detailed analyses of their long-term effects are only possible ex-post. Therefore, preparations for such events should focus on reactive capabilities to ensure that: research efforts can be quickly and adequately supported; their results are credibly communicated to the authorities and the general public; and scientifically-founded counter-measures are rapidly implemented. These characteristics apply to both health measures and economic policy. Furthermore, when these dramatic events occur, the effective public intervention should be timely (Bai et al. 2021 ; Martin et al. 2020 ; Rodríguez-Caballero and Vera-Valdés 2020 ; Stiglitz and Guzman 2021 ) and designed starting from the general characteristics that emerged in this review, and then directed over time by distinctive challenges brought by the specific health shock. The second lesson is that symmetric health shocks will lead to asymmetric economic long-term consequences, as country-specific institutional settings mediate most effects. The tendencies towards the uncritical adoption of global solutions should be tempered by concern for the specific features of local socioeconomic systems, leading to a preliminary process of policy customization. Resistance and push-back from below should not be interpreted automatically as regressive tendencies, but rather as symptoms of the need for policy adaptation to local concerns. Finally, the third lesson is that, while pandemics require careful and extensive public intervention, what matters most in the long term is to avoid crushing the innovative response capabilities of the private sector. A virtuous process of creative destruction may emerge only if public intervention does not attempt to restore the old socioeconomic regime, potentially now unsustainable, at all costs, trampling adaptive bottom-up initiatives in the process. Consequently, while initial efforts should be aimed towards counteracting immediate shocks, they should eventually be complemented by measures aiming to support the positive qualitative developments triggered by the pandemic and curb emerging negative trends. Thus, a potential positive role for policy action can be expected to persist well beyond the outbreak period, focusing on enabling and supporting positive private responses through processes of institutional change.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has made evident the need to study the overall economic effects of global health shocks. This literature review collects the main contributions that describe the long-term impact of a pandemic, in order to better understand the lessons from the current economic literature on this topic, and then to better address and analyze the effects on economic development of COVID-19 and of future risks of pandemics. The contributions are organized by discussing, in turn, the mechanisms affecting: labor and human capital; investments and physical capital; and knowledge and innovation. We conclude that pandemics could affect aggregate demand, aggregate supply, and productivity (Jinjarak et al. 2021 ). More precisely, we show that a pandemic reduces labor supply and human capital accumulation in the long term; that the complex interaction of these contrasting and idiosyncratic mechanisms on investments and savings is theoretically indeterminate; and that pandemics, when accompanied by supporting institutional change, can greatly benefit innovation and knowledge development. However, a detailed analysis of the pandemic’s specific characteristics, the affected economic systems, and their response remains necessary to understand which mechanisms can be expected to prevail and which policies should be implemented. The key factors determining their long-term impact are the associated processes of institutional change. We finally identify some general lessons for both researchers and policymakers. The research focuses on the theoretical plausibility and empirical significance of specific mechanisms that should be complemented by meta-analytic efforts aimed at reconstructing the resulting complexity. Policymakers should prioritize developing organizational learning and innovative capabilities, focusing on the ability to quickly adapt to emergencies, rather than developing rigid protocols calibrated over previous pandemics.

We expect the emergence of three new strands of literature in the near future. The first field of research will be on the long-term economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (Jordà et al. 2021 ; Poblete-Cazenave 2021 ; Tokic 2020 ). Such research will contribute to testing previously identified mechanisms reviewed here, while potentially also leading to the identification and theorization of new ones (Cacault et al. 2021 ; Silverio-Murillo et al. 2021 ; Costa Junior et al. 2021 ; Favilukis et al. 2021 ; Pagano et al. 2021 ). We also expect significant interest in comparing the impact of COVID-19 with previous pandemics, in order to highlight the relative importance of their respective defining features. The second field of research will be on the public and private responses to the effects of pandemics. The heterogeneity of both the method and timing of the institutional responses for the same health shock can be used to effectively test their efficiency and reduce the impact of future pandemic and epidemic waves (Adolph et al. 2021 ; Caserotti et al. 2021 ; Chakrabarty and Roy 2021 ; Croce et al. 2021 ; Martin et al. 2020 ). The ongoing debate on structural changes as a response to COVID-19 can be seen as a first step in increasing academic attention to the problem of the prediction of possible future pandemics and the precautionary measures to be taken in dealing with these events (Büscher et al. 2021 ; Dosi et al. 2020 ; Leach et al. 2021 ). Finally, we expect a more extensive interaction between, and cross-fertilization of, the medical and economic literatures (Avery et al. 2020 ; Murray 2020 ; Verikios 2020 ). This combination will be needed to better understand how a specific feature of the virus impacts economic development. A taxonomy of pandemics is necessary to group them correctly and then clarify how the different mechanisms move in and impact economic development. In general, we expect the academic debate on the long-term economic impact of pandemics to be renewed and reinforced in the coming years. This survey has the ultimate goal of preparing the basis for this inevitable and intellectually challenging new generation of scientific contributions on the long-term economic effects of pandemics.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Aassve A, Alfani G, Gandolfi F, Le Moglie M (2021) Epidemics and trust: the case of the Spanish flu. Health Econ 30(4):840–857

Article Google Scholar

Acemoglu D, Johnson S (2007) Disease and development: the effect of life expectancy on economic growth. J Polit Econ 115(6):925–985

Adda J (2016) Economic activity and the spread of viral diseases: evidence from high frequency data. Q J Econ 131(2):891–941

Adolph C, Amano K, Bang-Jensen B, Fullman N, Wilkerson J (2021) Pandemic politics: timing state-level social distancing responses to COVID-19. J Health Polit Policy Law 46(2):211–233

Alfani G (2013) Plague in seventeenth-century Europe and the decline of Italy: an epidemiological hypothesis. Eur Rev Econ Hist 17(4):408–430