Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 679–689, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Drishti Yadav ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2974-0323 1

73k Accesses

25 Citations

71 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then, references of relevant articles were surveyed to find noteworthy, distinct, and well-defined pointers to good qualitative research. This review presents an investigative assessment of the pivotal features in qualitative research that can permit the readers to pass judgment on its quality and to condemn it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the necessity to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. It also offers some prospects and recommendations to improve the quality of qualitative research. Based on the findings of this review, it is concluded that quality criteria are the aftereffect of socio-institutional procedures and existing paradigmatic conducts. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single and specific set of quality criteria is neither feasible nor anticipated. Since qualitative research is not a cohesive discipline, researchers need to educate and familiarize themselves with applicable norms and decisive factors to evaluate qualitative research from within its theoretical and methodological framework of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

What is Qualitative in Qualitative Research

Patrik Aspers & Ugo Corte

Qualitative Research: Ethical Considerations

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

Loraine Busetto, Wolfgang Wick & Christoph Gumbinger

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“… It is important to regularly dialogue about what makes for good qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 , p. 837)

To decide what represents good qualitative research is highly debatable. There are numerous methods that are contained within qualitative research and that are established on diverse philosophical perspectives. Bryman et al., ( 2008 , p. 262) suggest that “It is widely assumed that whereas quality criteria for quantitative research are well‐known and widely agreed, this is not the case for qualitative research.” Hence, the question “how to evaluate the quality of qualitative research” has been continuously debated. There are many areas of science and technology wherein these debates on the assessment of qualitative research have taken place. Examples include various areas of psychology: general psychology (Madill et al., 2000 ); counseling psychology (Morrow, 2005 ); and clinical psychology (Barker & Pistrang, 2005 ), and other disciplines of social sciences: social policy (Bryman et al., 2008 ); health research (Sparkes, 2001 ); business and management research (Johnson et al., 2006 ); information systems (Klein & Myers, 1999 ); and environmental studies (Reid & Gough, 2000 ). In the literature, these debates are enthused by the impression that the blanket application of criteria for good qualitative research developed around the positivist paradigm is improper. Such debates are based on the wide range of philosophical backgrounds within which qualitative research is conducted (e.g., Sandberg, 2000 ; Schwandt, 1996 ). The existence of methodological diversity led to the formulation of different sets of criteria applicable to qualitative research.

Among qualitative researchers, the dilemma of governing the measures to assess the quality of research is not a new phenomenon, especially when the virtuous triad of objectivity, reliability, and validity (Spencer et al., 2004 ) are not adequate. Occasionally, the criteria of quantitative research are used to evaluate qualitative research (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008 ; Lather, 2004 ). Indeed, Howe ( 2004 ) claims that the prevailing paradigm in educational research is scientifically based experimental research. Hypotheses and conjectures about the preeminence of quantitative research can weaken the worth and usefulness of qualitative research by neglecting the prominence of harmonizing match for purpose on research paradigm, the epistemological stance of the researcher, and the choice of methodology. Researchers have been reprimanded concerning this in “paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2000 ).

In general, qualitative research tends to come from a very different paradigmatic stance and intrinsically demands distinctive and out-of-the-ordinary criteria for evaluating good research and varieties of research contributions that can be made. This review attempts to present a series of evaluative criteria for qualitative researchers, arguing that their choice of criteria needs to be compatible with the unique nature of the research in question (its methodology, aims, and assumptions). This review aims to assist researchers in identifying some of the indispensable features or markers of high-quality qualitative research. In a nutshell, the purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyze the existing knowledge on high-quality qualitative research and to verify the existence of research studies dealing with the critical assessment of qualitative research based on the concept of diverse paradigmatic stances. Contrary to the existing reviews, this review also suggests some critical directions to follow to improve the quality of qualitative research in different epistemological and ontological perspectives. This review is also intended to provide guidelines for the acceleration of future developments and dialogues among qualitative researchers in the context of assessing the qualitative research.

The rest of this review article is structured in the following fashion: Sect. Methods describes the method followed for performing this review. Section Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies provides a comprehensive description of the criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. This section is followed by a summary of the strategies to improve the quality of qualitative research in Sect. Improving Quality: Strategies . Section How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings? provides details on how to assess the quality of the research findings. After that, some of the quality checklists (as tools to evaluate quality) are discussed in Sect. Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality . At last, the review ends with the concluding remarks presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook . Some prospects in qualitative research for enhancing its quality and usefulness in the social and techno-scientific research community are also presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook .

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed from many databases using generic search terms such as Qualitative Research , Criteria , etc . The following databases were chosen for the literature search based on the high number of results: IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The following keywords (and their combinations using Boolean connectives OR/AND) were adopted for the literature search: qualitative research, criteria, quality, assessment, and validity. The synonyms for these keywords were collected and arranged in a logical structure (see Table 1 ). All publications in journals and conference proceedings later than 1950 till 2021 were considered for the search. Other articles extracted from the references of the papers identified in the electronic search were also included. A large number of publications on qualitative research were retrieved during the initial screening. Hence, to include the searches with the main focus on criteria for good qualitative research, an inclusion criterion was utilized in the search string.

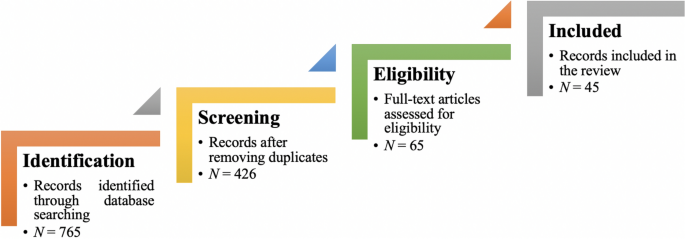

From the selected databases, the search retrieved a total of 765 publications. Then, the duplicate records were removed. After that, based on the title and abstract, the remaining 426 publications were screened for their relevance by using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2 ). Publications focusing on evaluation criteria for good qualitative research were included, whereas those works which delivered theoretical concepts on qualitative research were excluded. Based on the screening and eligibility, 45 research articles were identified that offered explicit criteria for evaluating the quality of qualitative research and were found to be relevant to this review.

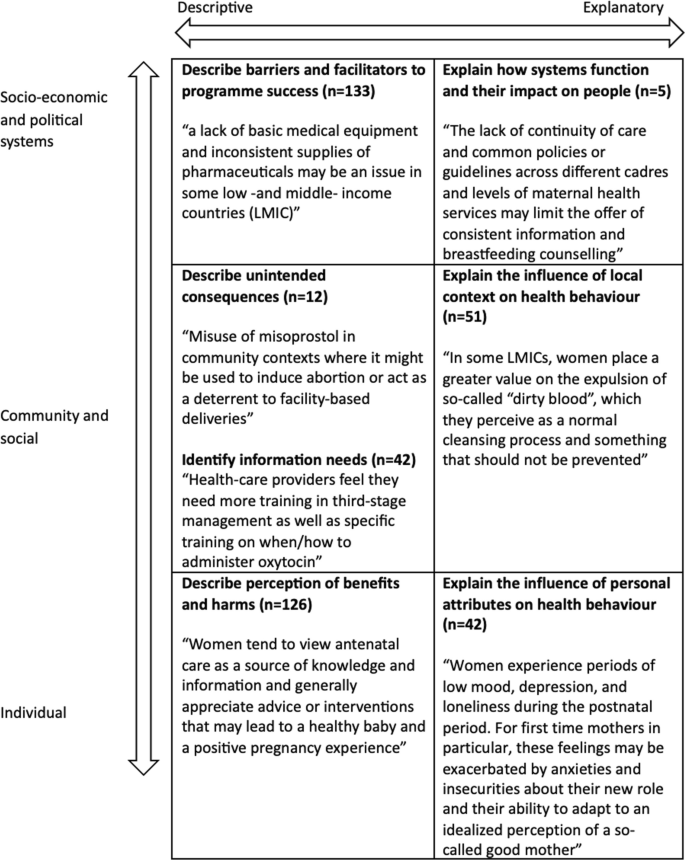

Figure 1 illustrates the complete review process in the form of PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, i.e., “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” is employed in systematic reviews to refine the quality of reporting.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and inclusion process. N represents the number of records

Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies

Fundamental criteria: general research quality.

Various researchers have put forward criteria for evaluating qualitative research, which have been summarized in Table 3 . Also, the criteria outlined in Table 4 effectively deliver the various approaches to evaluate and assess the quality of qualitative work. The entries in Table 4 are based on Tracy’s “Eight big‐tent criteria for excellent qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 ). Tracy argues that high-quality qualitative work should formulate criteria focusing on the worthiness, relevance, timeliness, significance, morality, and practicality of the research topic, and the ethical stance of the research itself. Researchers have also suggested a series of questions as guiding principles to assess the quality of a qualitative study (Mays & Pope, 2020 ). Nassaji ( 2020 ) argues that good qualitative research should be robust, well informed, and thoroughly documented.

Qualitative Research: Interpretive Paradigms

All qualitative researchers follow highly abstract principles which bring together beliefs about ontology, epistemology, and methodology. These beliefs govern how the researcher perceives and acts. The net, which encompasses the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises, is referred to as a paradigm, or an interpretive structure, a “Basic set of beliefs that guides action” (Guba, 1990 ). Four major interpretive paradigms structure the qualitative research: positivist and postpositivist, constructivist interpretive, critical (Marxist, emancipatory), and feminist poststructural. The complexity of these four abstract paradigms increases at the level of concrete, specific interpretive communities. Table 5 presents these paradigms and their assumptions, including their criteria for evaluating research, and the typical form that an interpretive or theoretical statement assumes in each paradigm. Moreover, for evaluating qualitative research, quantitative conceptualizations of reliability and validity are proven to be incompatible (Horsburgh, 2003 ). In addition, a series of questions have been put forward in the literature to assist a reviewer (who is proficient in qualitative methods) for meticulous assessment and endorsement of qualitative research (Morse, 2003 ). Hammersley ( 2007 ) also suggests that guiding principles for qualitative research are advantageous, but methodological pluralism should not be simply acknowledged for all qualitative approaches. Seale ( 1999 ) also points out the significance of methodological cognizance in research studies.

Table 5 reflects that criteria for assessing the quality of qualitative research are the aftermath of socio-institutional practices and existing paradigmatic standpoints. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single set of quality criteria is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the researchers must be reflexive about the criteria they use in the various roles they play within their research community.

Improving Quality: Strategies

Another critical question is “How can the qualitative researchers ensure that the abovementioned quality criteria can be met?” Lincoln and Guba ( 1986 ) delineated several strategies to intensify each criteria of trustworthiness. Other researchers (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016 ; Shenton, 2004 ) also presented such strategies. A brief description of these strategies is shown in Table 6 .

It is worth mentioning that generalizability is also an integral part of qualitative research (Hays & McKibben, 2021 ). In general, the guiding principle pertaining to generalizability speaks about inducing and comprehending knowledge to synthesize interpretive components of an underlying context. Table 7 summarizes the main metasynthesis steps required to ascertain generalizability in qualitative research.

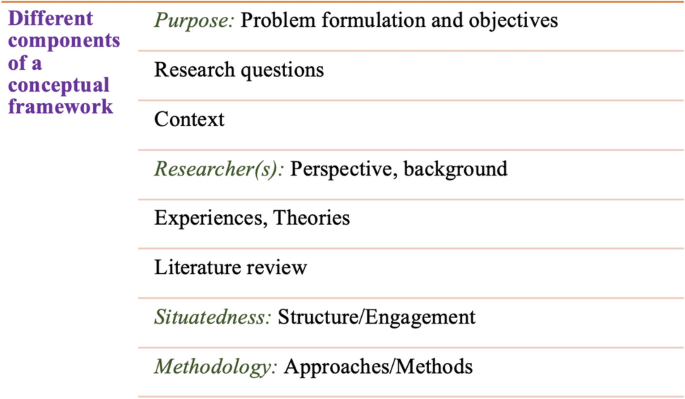

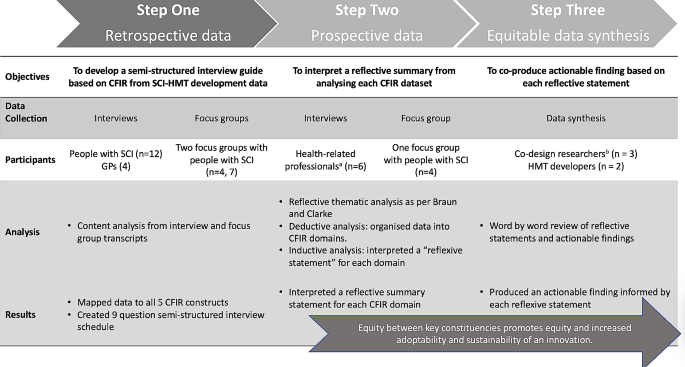

Figure 2 reflects the crucial components of a conceptual framework and their contribution to decisions regarding research design, implementation, and applications of results to future thinking, study, and practice (Johnson et al., 2020 ). The synergy and interrelationship of these components signifies their role to different stances of a qualitative research study.

Essential elements of a conceptual framework

In a nutshell, to assess the rationale of a study, its conceptual framework and research question(s), quality criteria must take account of the following: lucid context for the problem statement in the introduction; well-articulated research problems and questions; precise conceptual framework; distinct research purpose; and clear presentation and investigation of the paradigms. These criteria would expedite the quality of qualitative research.

How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings?

The inclusion of quotes or similar research data enhances the confirmability in the write-up of the findings. The use of expressions (for instance, “80% of all respondents agreed that” or “only one of the interviewees mentioned that”) may also quantify qualitative findings (Stenfors et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the persuasive reason for “why this may not help in intensifying the research” has also been provided (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020 ). Further, the Discussion and Conclusion sections of an article also prove robust markers of high-quality qualitative research, as elucidated in Table 8 .

Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality

Numerous checklists are available to speed up the assessment of the quality of qualitative research. However, if used uncritically and recklessly concerning the research context, these checklists may be counterproductive. I recommend that such lists and guiding principles may assist in pinpointing the markers of high-quality qualitative research. However, considering enormous variations in the authors’ theoretical and philosophical contexts, I would emphasize that high dependability on such checklists may say little about whether the findings can be applied in your setting. A combination of such checklists might be appropriate for novice researchers. Some of these checklists are listed below:

The most commonly used framework is Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007 ). This framework is recommended by some journals to be followed by the authors during article submission.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is another checklist that has been created particularly for medical education (O’Brien et al., 2014 ).

Also, Tracy ( 2010 ) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021 ) offer criteria for qualitative research relevant across methods and approaches.

Further, researchers have also outlined different criteria as hallmarks of high-quality qualitative research. For instance, the “Road Trip Checklist” (Epp & Otnes, 2021 ) provides a quick reference to specific questions to address different elements of high-quality qualitative research.

Conclusions, Future Directions, and Outlook

This work presents a broad review of the criteria for good qualitative research. In addition, this article presents an exploratory analysis of the essential elements in qualitative research that can enable the readers of qualitative work to judge it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. In this review, some of the essential markers that indicate high-quality qualitative research have been highlighted. I scope them narrowly to achieve rigor in qualitative research and note that they do not completely cover the broader considerations necessary for high-quality research. This review points out that a universal and versatile one-size-fits-all guideline for evaluating the quality of qualitative research does not exist. In other words, this review also emphasizes the non-existence of a set of common guidelines among qualitative researchers. In unison, this review reinforces that each qualitative approach should be treated uniquely on account of its own distinctive features for different epistemological and disciplinary positions. Owing to the sensitivity of the worth of qualitative research towards the specific context and the type of paradigmatic stance, researchers should themselves analyze what approaches can be and must be tailored to ensemble the distinct characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. Although this article does not assert to put forward a magic bullet and to provide a one-stop solution for dealing with dilemmas about how, why, or whether to evaluate the “goodness” of qualitative research, it offers a platform to assist the researchers in improving their qualitative studies. This work provides an assembly of concerns to reflect on, a series of questions to ask, and multiple sets of criteria to look at, when attempting to determine the quality of qualitative research. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the need to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. Bringing together the vital arguments and delineating the requirements that good qualitative research should satisfy, this review strives to equip the researchers as well as reviewers to make well-versed judgment about the worth and significance of the qualitative research under scrutiny. In a nutshell, a comprehensive portrayal of the research process (from the context of research to the research objectives, research questions and design, speculative foundations, and from approaches of collecting data to analyzing the results, to deriving inferences) frequently proliferates the quality of a qualitative research.

Prospects : A Road Ahead for Qualitative Research

Irrefutably, qualitative research is a vivacious and evolving discipline wherein different epistemological and disciplinary positions have their own characteristics and importance. In addition, not surprisingly, owing to the sprouting and varied features of qualitative research, no consensus has been pulled off till date. Researchers have reflected various concerns and proposed several recommendations for editors and reviewers on conducting reviews of critical qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2021 ; McGinley et al., 2021 ). Following are some prospects and a few recommendations put forward towards the maturation of qualitative research and its quality evaluation:

In general, most of the manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts. Hence, it is more likely that they would prefer to adopt a broad set of criteria. However, researchers and reviewers need to keep in mind that it is inappropriate to utilize the same approaches and conducts among all qualitative research. Therefore, future work needs to focus on educating researchers and reviewers about the criteria to evaluate qualitative research from within the suitable theoretical and methodological context.

There is an urgent need to refurbish and augment critical assessment of some well-known and widely accepted tools (including checklists such as COREQ, SRQR) to interrogate their applicability on different aspects (along with their epistemological ramifications).

Efforts should be made towards creating more space for creativity, experimentation, and a dialogue between the diverse traditions of qualitative research. This would potentially help to avoid the enforcement of one's own set of quality criteria on the work carried out by others.

Moreover, journal reviewers need to be aware of various methodological practices and philosophical debates.

It is pivotal to highlight the expressions and considerations of qualitative researchers and bring them into a more open and transparent dialogue about assessing qualitative research in techno-scientific, academic, sociocultural, and political rooms.

Frequent debates on the use of evaluative criteria are required to solve some potentially resolved issues (including the applicability of a single set of criteria in multi-disciplinary aspects). Such debates would not only benefit the group of qualitative researchers themselves, but primarily assist in augmenting the well-being and vivacity of the entire discipline.

To conclude, I speculate that the criteria, and my perspective, may transfer to other methods, approaches, and contexts. I hope that they spark dialog and debate – about criteria for excellent qualitative research and the underpinnings of the discipline more broadly – and, therefore, help improve the quality of a qualitative study. Further, I anticipate that this review will assist the researchers to contemplate on the quality of their own research, to substantiate research design and help the reviewers to review qualitative research for journals. On a final note, I pinpoint the need to formulate a framework (encompassing the prerequisites of a qualitative study) by the cohesive efforts of qualitative researchers of different disciplines with different theoretic-paradigmatic origins. I believe that tailoring such a framework (of guiding principles) paves the way for qualitative researchers to consolidate the status of qualitative research in the wide-ranging open science debate. Dialogue on this issue across different approaches is crucial for the impending prospects of socio-techno-educational research.

Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16 (10), 1472–1482.

Article Google Scholar

Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (3–4), 201–212.

Bryman, A., Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 261–276.

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2 (2), 1–13.

CASP (2021). CASP checklists. Retrieved May 2021 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6 (4), 331–339.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd.

Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Epp, A. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2021). High-quality qualitative research: Getting into gear. Journal of Service Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520961445

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. In Alternative paradigms conference, mar, 1989, Indiana u, school of education, San Francisco, ca, us . Sage Publications, Inc.

Hammersley, M. (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 30 (3), 287–305.

Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A Delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406920976417.

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99 (2), 178–188.

Horsburgh, D. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12 (2), 307–312.

Howe, K. R. (2004). A critique of experimentalism. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 42–46.

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84 (1), 7120.

Johnson, P., Buehring, A., Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2006). Evaluating qualitative management research: Towards a contingent criteriology. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8 (3), 131–156.

Klein, H. K., & Myers, M. D. (1999). A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 23 (1), 67–93.

Lather, P. (2004). This is your father’s paradigm: Government intrusion and the case of qualitative research in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 15–34.

Levitt, H. M., Morrill, Z., Collins, K. M., & Rizo, J. L. (2021). The methodological integrity of critical qualitative research: Principles to support design and research review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68 (3), 357.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986 (30), 73–84.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 163–188). Sage Publications.

Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91 (1), 1–20.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2020). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Health Care . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867.ch15

McGinley, S., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The state of qualitative research in hospitality: A 5-year review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62 (1), 8–20.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, US.

Meyer, M., & Dykes, J. (2019). Criteria for rigor in visualization design study. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 26 (1), 87–97.

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2020). When I say… quantification in qualitative research. Medical Education, 54 (3), 186–187.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 250.

Morse, J. M. (2003). A review committee’s guide for evaluating qualitative proposals. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (6), 833–851.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24 (4), 427–431.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406919899220.

Reid, A., & Gough, S. (2000). Guidelines for reporting and evaluating qualitative research: What are the alternatives? Environmental Education Research, 6 (1), 59–91.

Rocco, T. S. (2010). Criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. Human Resource Development International . https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2010.501959

Sandberg, J. (2000). Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (1), 9–25.

Schwandt, T. A. (1996). Farewell to criteriology. Qualitative Inquiry, 2 (1), 58–72.

Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (4), 465–478.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 (2), 63–75.

Sparkes, A. C. (2001). Myth 94: Qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qualitative Health Research, 11 (4), 538–552.

Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2004). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence.

Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17 (6), 596–599.

Taylor, E. W., Beck, J., & Ainsworth, E. (2001). Publishing qualitative adult education research: A peer review perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 33 (2), 163–179.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19 (6), 349–357.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16 (10), 837–851.

Download references

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Informatics, Technische Universität Wien, 1040, Vienna, Austria

Drishti Yadav

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Drishti Yadav .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yadav, D. Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31 , 679–689 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Download citation

Accepted : 28 August 2021

Published : 18 September 2021

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Evaluative criteria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

About Journal

American Journal of Qualitative Research (AJQR) is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal that publishes qualitative research articles from a number of social science disciplines such as psychology, health science, sociology, criminology, education, political science, and administrative studies. The journal is an international and interdisciplinary focus and greatly welcomes papers from all countries. The journal offers an intellectual platform for researchers, practitioners, administrators, and policymakers to contribute and promote qualitative research and analysis.

ISSN: 2576-2141

Call for Papers- American Journal of Qualitative Research

American Journal of Qualitative Research (AJQR) welcomes original research articles and book reviews for its next issue. The AJQR is a quarterly and peer-reviewed journal published in February, May, August, and November.

We are seeking submissions for a forthcoming issue published in February 2024. The paper should be written in professional English. The length of 6000-10000 words is preferred. All manuscripts should be prepared in MS Word format and submitted online: https://www.editorialpark.com/ajqr

For any further information about the journal, please visit its website: https://www.ajqr.org

Submission Deadline: November 15, 2023

Announcement

Dear AJQR Readers,

Due to the high volume of submissions in the American Journal of Qualitative Research , the editorial board decided to publish quarterly since 2023.

Volume 8, Issue 1

Current issue.

Social distancing requirements resulted in many people working from home in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 pandemic. The topic of working from home was often discussed in the media and online during the pandemic, but little was known about how quality of life (QOL) and remote working interfaced. The purpose of this study was to describe QOL while working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. The novel topic, unique methodological approach of the General Online Qualitative Study ( D’Abundo & Franco, 2022a), and the strategic Social Distancing Sampling ( D’Abundo & Franco, 2022c) resulted in significant participation throughout the world (n = 709). The United Kingdom subset of participants (n = 234) is the focus of this article. This big qual, large qualitative study (n >100) included the principal investigator-developed, open-ended, online questionnaire entitled the “Quality of Life Home Workplace Questionnaire (QOLHWQ)” and demographic questions. Data were collected peak-pandemic from July to September 2020. Most participants cited increased QOL due to having more time with family/kids/partners/pets, a more comfortable work environment while being at home, and less commuting to work. The most cited issue associated with negative QOL was social isolation. As restrictions have been lifted and public health emergency declarations have been terminated during the post-peak era of the COVID-19 pandemic, the potential for future public health emergencies requiring social distancing still exists. To promote QOL and work-life balance for employees working remotely in the United Kingdom, stakeholders could develop social support networks and create effective planning initiatives to prevent social isolation and maximize the benefits of remote working experiences for both employees and organizations.

Keywords: qualitative research, quality of life, remote work, telework, United Kingdom, work from home.

(no abstract)

This essay reviews classic works on the philosophy of science and contemporary pedagogical guides to scientific inquiry in order to present a discussion of the three logics that underlie qualitative research in political science. The first logic, epistemology, relates to the essence of research as a scientific endeavor and is framed as a debate between positivist and interpretivist orientations within the discipline of political science. The second logic, ontology, relates to the approach that research takes to investigating the empirical world and is framed as a debate between positivist qualitative and quantitative orientations, which together constitute the vast majority of mainstream researchers within the discipline. The third logic, methodology, relates to the means by which research aspires to reach its scientific ends and is framed as a debate among positivist qualitative orientations. Additionally, the essay discusses the present state of qualitative research in the discipline of political science, reviews the various ways in which qualitative research is defined in the relevant literature, addresses the limitations and trade-offs that are inherently associated with the aforementioned logics of qualitative research, explores multimethod approaches to remedying these issues, and proposes avenues for acquiring further information on the topics discussed.

Keywords: qualitative research, epistemology, ontology, methodology

This paper examines the phenomenology of diagnostic crossover in eating disorders, the movement within or between feeding and eating disorder subtypes or diagnoses over time, in two young women who experienced multiple changes in eating disorder diagnosis over 5 years. Using interpretative phenomenological analysis, this study found that transitioning between different diagnostic labels, specifically between bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa binge/purge subtype, was experienced as disempowering, stigmatizing, and unhelpful. The findings in this study offer novel evidence that, from the perspective of individuals diagnosed with EDs, using BMI as an indicator of the presence, severity, or change of an ED may have adverse consequences for well-being and recovery and may lead to mischaracterization or misclassification of health status. The narratives discussed in this paper highlight the need for more person-centered practices in the context of diagnostic crossover. Including the perspectives of those with lived experience can help care providers working with individuals with eating disorders gain an in-depth understanding of the potential personal impact of diagnosis changing and inform discussions around developing person-focused diagnostic practices.

Keywords: feeding and eating disorders, bulimia nervosa, diagnostic labels, diagnostic crossover, illness narrative

Often among the first witnesses to child trauma, educators and therapists are on the frontline of an unfolding and multi-pronged occupational crisis. For educators, lack of support and secondary traumatic stress (STS) appear to be contributing to an epidemic in professional attrition. Similarly, therapists who do not prioritize self-care can feel depleted of energy and optimism. The purpose of this phenomenological study was to examine how bearing witness to the traumatic narratives of children impacts similar helping professionals. The study also sought to extrapolate the similarities and differences between compassion fatigue and secondary trauma across these two disciplines. Exploring the common factors and subjective individual experiences related to occupational stress across these two fields may foster a more complete picture of the delicate nature of working with traumatized children and the importance of successful self-care strategies. Utilizing Constructivist Self-Development Theory (CSDT) and focus group interviews, the study explores the significant risk of STS facing both educators and therapists.

Keywords: qualitative, secondary traumatic stress, self-care, child trauma, educators, therapists.

This study explored the lived experiences of residents of the Gulf Coast in the USA during Hurricane Katrina, which made landfall in August 2005 and caused insurmountable destruction throughout the area. A heuristic process and thematic analysis were employed to draw observations and conclusions about the lived experiences of each participant and make meaning through similar thoughts, feelings, and themes that emerged in the analysis of the data. Six themes emerged: (1) fear, (2) loss, (3) anger, (4) support, (5) spirituality, and (6) resilience. The results of this study allude to the possible psychological outcomes as a result of experiencing a traumatic event and provide an outline of what the psychological experience of trauma might entail. The current research suggests that preparedness and expectation are key to resilience and that people who feel that they have power over their situation fare better than those who do not.

Keywords: mass trauma, resilience, loss, natural disaster, mental health.

Women from rural, low-income backgrounds holding positions within the academy are the exception and not the rule. Most women faculty in the academy are from urban/suburban areas and middle- and upper-income family backgrounds. As women faculty who do not represent this norm, our primary goal with this article is to focus on the unique barriers we experienced as girls from rural, low-income areas in K-12 schools that influenced the possibilities for successfully transitioning to and engaging with higher education. We employed a qualitative duoethnographic and narrative research design to respond to the research questions, and we generated our data through semi-structured, critical, ethnographic dialogic conversations. Our duoethnographic-narrative analyses revealed six major themes: (1) independence and other benefits of having a working-class mom; (2) crashing into middle-class norms and expectations; (3) lucking and falling into college; (4) fish out of water; (5) overcompensating, playing middle class, walking on eggshells, and pushing back; and (6) transitioning from a working-class kid to a working class academic, which we discuss in relation to our own educational attainment.

Keywords: rurality, working-class, educational attainment, duoethnography, higher education, women.

This article draws on the findings of a qualitative study that focused on the perspectives of four Indian American mothers of youth with developmental disabilities on the process of transitioning from school to post-school environments. Data were collected through in-depth ethnographic interviews. The findings indicate that in their efforts to support their youth with developmental disabilities, the mothers themselves navigate multiple transitions across countries, constructs, dreams, systems of schooling, and services. The mothers’ perspectives have to be understood against the larger context of their experiences as citizens of this country as well as members of the South Asian diaspora. The mothers’ views on services, their journey, their dreams for their youth, and their interpretation of the ideas anchored in current conversations on transition are continually evolving. Their attempts to maintain their resilience and their indigenous understandings while simultaneously negotiating their experiences in the United States with supporting their youth are discussed.

Keywords: Indian-American mothers, transitioning, diaspora, disability, dreams.

This study explored the influence of yoga on practitioners’ lives ‘off the mat’ through a phenomenological lens. Central to the study was the lived experience of yoga in a purposive sample of self-identified New Zealand practitioners (n=38; 89.5% female; aged 18 to 65 years; 60.5% aged 36 to 55 years). The study’s aim was to explore whether habitual yoga practitioners experience any pro-health downstream effects of their practice ‘off the mat’ via their lived experience of yoga. A qualitative mixed methodology was applied via a phenomenological lens that explicitly acknowledged the researcher’s own experience of the research topic. Qualitative methods comprised an open-ended online survey for all participants (n=38), followed by in-depth semi-structured interviews (n=8) on a randomized subset. Quantitative methods included online outcome measures (health habits, self-efficacy, interoceptive awareness, and physical activity), practice component data (tenure, dose, yoga styles, yoga teacher status, meditation frequency), and socio-demographics. This paper highlights the qualitative findings emerging from participant narratives. Reported benefits of practice included the provision of a filter through which to engage with life and the experience of self-regulation and mindfulness ‘off the mat’. Practitioners experienced yoga as a self-sustaining positive resource via self-regulation guided by an embodied awareness. The key narrative to emerge was an attunement to embodiment through movement. Embodied movement can elicit self-regulatory pathways that support health behavior.

Keywords: embodiment, habit, interoception, mindfulness, movement practice, qualitative, self-regulation, yoga.

Historically and in the present day, Black women’s positionality in the U.S. has paradoxically situated them in a society where they are both intrinsically essential and treated as expendable. This positionality, known as gendered racism, manifests commonly in professional environments and results in myriad harms. In response, Black women have developed, honed, and practiced a range of coping styles to mitigate the insidious effects of gendered racism. While often effective in the short-term, these techniques frequently complicate Black women’s well-being. For Black female clinicians who experience gendered racism and work on the frontlines of community mental health, myriad bio-psycho-social-spiritual harms compound. This project provided an opportunity for Black female clinicians from across the U.S. to share their experiences during the dual pandemics of COVID-19 and anti-Black violence. I conducted in-depth interviews with clinicians (n=14) between the ages of 30 and 58. Using the Listening Guide voice-centered approach to data generation and analysis, I identified four voices to help answer this project’s central question: How do you experience being a Black female clinician in the U.S.? The voices of self, pride, vigilance, and mediating narrated the complex ways participants experienced their workplaces. This complexity seemed to be context-specific, depending on whether the clinicians worked in predominantly White workplaces (PWW), a mix of PWW and private practice, or private practice exclusively. Participants who worked only in PWW experienced the greatest stress, oppression, and burnout risk, while participants who worked exclusively in private practice reported more joy, more authenticity, and more job satisfaction. These findings have implications for mentoring, supporting, and retaining Black female clinicians.

Keywords: Black female clinicians, professional experiences, gendered racism, Listening Guide voice-centered approach.

The purpose of this article is to speak directly to the paucity of research regarding Dominican American women and identity narratives. To do so, this article uses the Listening Guide Method of Qualitative Inquiry (Gilligan, et al., 2006) to explore how 1.5 and second-generation Dominican American women narrated their experiences of individual identity within American cultural contexts and constructs. The results draw from the emergence of themes across six participant interviews and showed two distinct voices: The Voice of Cultural Explanation and the Tides of Dominican American Female Identity. Narrative examples from five participants are offered to illustrate where 1.5 and second-generation Dominican American women negotiate their identity narratives at the intersection of their Dominican and American selves. The article offers two conclusions. One, that participant women use the Voice of Cultural Explanation in order to discuss their identity as reflected within the broad cultural tensions of their daily lives. Two, that the Tides of Dominican American Female Identity are used to express strong emotions that manifest within their personal narratives as the unwanted distance from either the Dominican or American parts of their person.

Keywords: Dominican American, women, identity, the Listening Guide, narratives

- April 1, 2024 | Weekly Report – April 1, 2024

- March 25, 2024 | Weekly Report – March 25, 2024

- March 18, 2024 | Weekly Report – March 18, 2024

- March 11, 2024 | Weekly Report – March 11, 2024

- March 4, 2024 | Weekly Report – March 4, 2024

Research Journals

The qualitative report guide to qualitative research journals, curated by ronald j. chenail.

The Qualitative Report Guide to Qualitative Research Journals is a unique resource for researchers, scholars, and students to explore the world of professional, scholarly, and academic journals publishing qualitative research. The number and variety of journals focusing primarily on qualitative approaches to research have steadily grown over the last forty years. From discipline- or profession-specific to trans-, cross-, and multidisciplinary missions, these journals represent a richly diverse approach to qualitative inquiry.

Acta Ethnographica Hungarica: An International Journal of Sociocultural Anthropology (First Issue: 1955)

Action Research (First Issue: 2003)

Action Research Electronic Reader (First Issue: 1997)

Action Research International (First Issue: 1998)

AI Practitioner (First Issue: 2003)

ALARA Journal (First Issue: 1996)

American Ethnologist (First Issue: 1974)

American Journal of Qualitative Research (First Issue: 2017)

Anthropology and Education Quarterly (First Issue: 1970)

The Applied Anthropologist (First Issue: 1981)

Biograf: časopis pro kvalitativní výzkum (Biograf: journal for qualitative research) (First Issue: 1994) (English Version )

Cadernos de Arte e Antropologia (First Issue: 2012)

The Canadian Journal of Action Research (First Issue: 2011; Formerly Ontario Action Researcher

Commoning Ethnography (First Issue: 2018)

Critical Approaches to Discourse Analysis Across Disciplines (First Issue: 2007)

Critical Discourse Studies (First Issue: 2004)

Cultural Anthropology (First issue: 1986)

Cultural Studies <=> Critical Methodologies (First Issue: 2001)

Current Narratives (First Issue: 2009)

Departures in Critical Qualitative Research (First Issue: 2012) (This journal was formally known as Qualitative Communication Research )

Discourse Analysis Online (First Issue: 2003)

Discourse, Context and Media (First Issue: 2012)

Discourse Processes (First Issue: 1978)

Discourse Studies (First Issue: 1999)

Educational Action Research (First Issue: 1993)

Electronic Journal of Sociology (First Issue: 1995)

Entanglements: Experiments in Multimodal Ethnography (First Issue: 2018)

Ethnographic Encounters (First Issue: 2012)

ethnographiques.org (First Issue: 2002)

Ethnography (First Issue: 2000)

Ethnography and Education (First Issue: 2006)

Ethnologia Europaea (Journal of European Ethnology, First issue: 1967)

Etnográfica (First issue: 1997)

Etnografia e ricerca qualitativa (Ethnography and Qualitative Research) (First issue: 2008)

European Journal for Qualitative Research in Psychotherapy (First Issue: 2006)

Feminism & Psychology (First Issue: 1991)

Field Methods (First Issue: 1989) (Formerly Cultural Anthropology Methods CAM Journal)

Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung

(Forum: Qualitative Social Research) (First Issue: 2000)

Gestalt Theory: An International Multidisciplinary Journal (First Issue: 1978)

Global Ethnographic: An Online Magazine of Interpretive Anthropology (First Issue: 2009)

Global Qualitative Nursing Research (First Issue: 2015)

The Grounded Theory Review (First Issue: 1999)

HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory (First Issue: 2011)

The Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology (First Issue: 2001)

International Journal of Action Research (First Issue: 2005)

International Journal of Qualitative Methods (First Issue: 2002)

International Journal of Qualitative Research (First Issue: 2021)

International Journal of Qualitative Research in Services (First Issue: 2013)

International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education (First Issue: 1988)

International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being (First Issue: 2006)

International Journal of Social Research Methodology (First Issue: 1998)

International Review of Qualitative Research (First Issue: 2008)

Investigación Cualitativa (First issue: 2016)

日本質的心理学会 (Japanese Journal of Qualitative Psychology) (First Issue: 2002)

Le Journal des anthropologues (First Issue: 1990)

The Journal for Undergraduate Ethnography (First Issue: 2011)

Journal of Autoethnography (First Issue: 2020)

Journal of Business Anthropology (First Issue: 2011)

Journal of Contemporary Ethnography (First Issue: 1972) (Formerly Urban Life and Culture)

Journal of Qualitative Research in Education (Eğitimde Nitel Araştırmalar Dergisi – ENAD, First Issue: 2013)

Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research (First Issue: 2007)

Journal of Mixed Methods Research (First Issue: 2007)

Journal of Museum Ethnography (First Issue: 1976)

Journal of Organizational Ethnography (First Issue: 2012)

Journal of Phenomenological Psychology (First Issue: 1970)

Journal of Qualitative Criminal Justice & Criminology (First Issue: 2013)

تحقیقات کیفی در علوم سلامت (Journal of Qualitative Research in Health Sciences) (First Issue: 2019)

Journal of Qualitative Research in Tourism (First Issue: 2020)

Journal of Video Ethnography (First Issue: 2014)

Kaleidoscope: A Graduate Journal of Qualitative Communication Research (First Issue: 2002)

KWALON, tijdschrift voor kwalitatief onderzoek (JOurnal for Qualitative Research) (First Issue: 1996)

The Malaysian Journal of Qualitative Research (First Issue: 2005)

Medical Anthropology Quarterly (First Issue: 1970)

Medicine Anthropology Theory (MAT) (First Issue: 2014)

Medische Antropologie (Medical Anthropology) (First Issue: 1989)

Methodological Innovations Online (First Issue: 2006)

Moroccan Journal of Quantitative and Qualitative Research (First Issue: 2019)

MOTRICIDADES: Revista da Sociedade de Pesquisa Qualitativa em Motricidade Humana (First Issue: 2017)

Murmurations: Journal of Transformative Systemic Practice (First Issue: 2017)

Museum Anthropology (First Issue: 1976)

Narrative Inquiry (First Issue: 1991) (Formerly Journal of Narrative and Life History; ( Old Web Page )

Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics: A Journal of Qualitative Research (First Issue: 2011)

Narrative Works: Issues, Investigations & Interventions (First Issue: 2011)

New Trends in Qualitative Research (First Issue: 2021)

Nitel Sosyal Bilimler (Qualitative Social Sciences) (First Issue: 2020)

Ontario Action Researcher (First Issue: 1998; Name changed to > The Canadian Journal of Action Research in 2011)

PhaenEx: Journal of Existential and Phenomenological Theory and Culture (First Issue: 2006)

Phenomenology & Practice (First Issue: 2007)

Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences (First Issue: 2001)

Poroi: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Rhetorical Analysis and Invention (First Issue: 2001)

Pragmatic Case Studies in Psychotherapy (First Issue: 2005)

Psychotherapie & Sozialwissenschaft (Psychotherapy & Social Science, First Issue: 2005)

QRSIG: Newsletter of the AERA Qualitative Research Interest Group (First Issue: 2007)

QQML: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries (First issue: 2012)

Qualitative Health Research (First Issue: 1991)

Qualitative Inquiries in Music Therapy: A Monograph Series (First Issue: 2004)

Qualitative Inquiry (First Issue: 1995)

Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal (First Issue: 1994)

Qualitative and Multi-Method Research (First Issue: 2014)

(Formerly Qualitative Methods)

Qualitative Psychology (First Issue: 2014)

質的心理学フォーラム (Qualitative Psychology Forums) (First Issue: 2009)

The Qualitative Report (First Issue: 1990)

Qualitative Research (First Issue: 2001)

Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management (First issue: 2004)

Qualitative Research in Education (First Issue: 2012)

Qualitative Research in Medicine & Healthcare (First Issue: 2017)

Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal (First Issue: 2005)

Qualitative Research in Psychology (First Issue: 2004)

Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise, and Health (First Issue: 2009)

Qualitative Research Journal (First issue: 2002)

Qualitative Research Reports in Communication (First Issue: 2000)

Qualitative Researcher (First Issue: 2005)

Qualitative Social Work: Research and Practice (First Issue: 2002)

Qualitative Sociology (First Issue: 1978)

Przeglądu Socjologii Jakościowej! (Qualitative Sociology Review) (First Issue: 2005)

Qualitative Studies (First Issue: 2009)

Quality and Quantity: International Journal of Methodology (First Issue: 1967)

QUILT: Journal of Qualitative Health Research & Case Studies Reports (iphorr.com) (First Issue: 2021)

QuiViRR: Qualitative Video Research Reports (First Issue: 2020)

QuPuG – Journal für Qualitative Forschung in Pflege- und Gesundheitswissenschaft (Journal of Qualitative Research in Nursing and Health Sciences) (First Issue: 2014)

Recherches qualitatives (First Issue: 1989)

Research in Phenomenology (First Issue: 1971)

Revista Pesquisa Qualitativa (Qualitative Research Journal) (First Issue: 2005)

Revue Internationale d’Ethnographie (First Issue: 2013) (Formerly Revue Européenne d’Ethnographie de l’Education)

Sociological Research Online (First Issue: 1996)

Social Research Update (First Issue: 1993)

The Socjournal: A New Media Journal of Sociology and Society (First Issue: 2010)

SSM – Qualitative Research in Health (First Issue: 2021)

Student Anthropologist (First Issue: 2014)

Symbolic Interaction (First Issue: 1977)

Tamara Journal for Critical Organization Inquiry (First Issue: 2002) (Formerly Tamara Journal for Critical Post Modern Organization)

Terrain (First Issue: 1983)

Turkish Online Journal of Qualitative Inquiry (First Issue: 2010)

Visual Ethnography (First Issue: 2012)

Visual Studies (First Issue: 1986)

Vitae Scholasticae: The Journal of Educational Biography (First Issue: 1983)

The Weekly Qualitative Report (First Issue: 2008)

ZQF – Zeitschrift für Qualitative Forschung (First issue: 1999)

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Practical thematic...

A new dawn for qualitative research in the BMJ

Rapid response to:

Practical thematic analysis: a guide for multidisciplinary health services research teams engaging in qualitative analysis

- Related content

- Article metrics

- Rapid responses

Rapid Response:

Dear Editor

We were delighted that a qualitative research methods paper was recently published in the BMJ.[1] We wondered if the BMJ had therefore reversed its stance that:

“We have chosen to focus our efforts on quantitative research that reports outcomes that are important to patient, doctors and policy makers.” [2]

We do, however, have some minor criticisms of the paper. We note that the old-fashioned term ‘theoretical saturation’ is used. Qualitative research methods are developing very rapidly, and the communities who use these methods now more usually refer to ‘theoretical sufficiency’ or ‘information power,’[3] which recognise that it is not possible to be sure of saturation. We also note that the authors refer to ‘member checking’ and ‘triangulation,’ without acknowledging contemporary debates about the usefulness of such these stages.[4] We recognise that some of these terms stem directly from the COREQ reporting guidelines, but also note that at seven years old, these guidelines are already out of touch with current thinking. The validity of COREQ has also been brought into question due to a lack of repeatability of its development.[5]

We were surprised that the authors did not make any reference to the incorporation of existing literature. Most qualitative analytical methods aim to build on existing studies, by incorporating theory either as ‘sensitising concepts’[6] or by predefining some of the codes. In the absence of this, researchers risk producing a study which constitutes a ‘brick on the pile’[7] as opposed to meaningfully adding to research in their area of interest (a brick in the wall).

We agree that the paper provides a wonderfully clear introduction to thematic analysis for novices, and commend the authors for making a somewhat complex process more accessible to clinicians.

We also hope that this paper heralds a new dawn for qualitative research publication within the BMJ, the results of which can be equally meaningful and important to patient, healthcare practitioners and the systems in which we work.

References 1 Saunders C, Sierpe A, von Plessen C, et al. Practical thematic analysis: a guide for multidisciplinary health services research teams engaging in qualitative analysis. BMJ 2023;e074256:381. 2 Loder E, Groves T, Schroter S, et al. Qualitative research and The BMJ. Bmj. 2016;352. 3 Varpio L, Ajjawi R, Monrouxe L V, et al. Shedding the cobra effect: problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Med Educ 2017;51:40–50. 4 Varpio L, Paradis E, Uijtdehaage S, et al. The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Academic Medicine 2020;95:989–94. 5 Buus N, Perron A. The quality of quality criteria: Replicating the development of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ). Int J Nurs Stud 2020;102:103452. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103452 6 Blumer H. What is wrong with social theory? Am Sociol Rev 1954;19:3–10. 7 Forscher BK. Chaos in the brickyard. Science (1979) 1963;142:35–8.

Competing interests: No competing interests

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 5, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 14 June 2021

Nurses in the lead: a qualitative study on the development of distinct nursing roles in daily nursing practice

- Jannine van Schothorst–van Roekel 1 ,

- Anne Marie J.W.M. Weggelaar-Jansen 1 ,

- Carina C.G.J.M. Hilders 1 ,

- Antoinette A. De Bont 1 &

- Iris Wallenburg 1

BMC Nursing volume 20 , Article number: 97 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

17k Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Transitions in healthcare delivery, such as the rapidly growing numbers of older people and increasing social and healthcare needs, combined with nursing shortages has sparked renewed interest in differentiations in nursing staff and skill mix. Policy attempts to implement new competency frameworks and job profiles often fails for not serving existing nursing practices. This study is aimed to understand how licensed vocational nurses (VNs) and nurses with a Bachelor of Science degree (BNs) shape distinct nursing roles in daily practice.

A qualitative study was conducted in four wards (neurology, oncology, pneumatology and surgery) of a Dutch teaching hospital. Various ethnographic methods were used: shadowing nurses in daily practice (65h), observations and participation in relevant meetings (n=56), informal conversations (up to 15 h), 22 semi-structured interviews and member-checking with four focus groups (19 nurses in total). Data was analyzed using thematic analysis.

Hospital nurses developed new role distinctions in a series of small-change experiments, based on action and appraisal. Our findings show that: (1) this developmental approach incorporated the nurses’ invisible work; (2) nurses’ roles evolved through the accumulation of small changes that included embedding the new routines in organizational structures; (3) the experimental approach supported the professionalization of nurses, enabling them to translate national legislation into hospital policies and supporting the nurses’ (bottom-up) evolution of practices. The new roles required the special knowledge and skills of Bachelor-trained nurses to support healthcare quality improvement and connect the patients’ needs to organizational capacity.

Conclusions

Conducting small-change experiments, anchored by action and appraisal rather than by design , clarified the distinctions between vocational and Bachelor-trained nurses. The process stimulated personal leadership and boosted the responsibility nurses feel for their own development and the nursing profession in general. This study indicates that experimental nursing role development provides opportunities for nursing professionalization and gives nurses, managers and policymakers the opportunity of a ‘two-way-window’ in nursing role development, aligning policy initiatives with daily nursing practices.

Peer Review reports

The aging population and mounting social and healthcare needs are challenging both healthcare delivery and the financial sustainability of healthcare systems [ 1 , 2 ]. Nurses play an important role in facing these contemporary challenges [ 3 , 4 ]. However, nursing shortages increase the workload which, in turn, boosts resignation numbers of nurses [ 5 , 6 ]. Research shows that nurses resign because they feel undervalued and have insufficient control over their professional practice and organization [ 7 , 8 ]. This issue has sparked renewed interest in nursing role development [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. A role can be defined by the activities assumed by one person, based on knowledge, modulated by professional norms, a legislative framework, the scope of practice and a social system [ 12 , 9 ].

New nursing roles usually arise through task specialization [ 13 , 14 ] and the development of advanced nursing roles [ 15 , 16 ]. Increasing attention is drawn to role distinction within nursing teams by differentiating the staff and skill mix to meet the challenges of nursing shortages, quality of care and low job satisfaction [ 17 , 18 ]. The staff and skill mix include the roles of enrolled nurses, registered nurses, and nurse assistants [ 19 , 20 ]. Studies on differentiation in staff and skill mix reveal that several countries struggle with the composition of nursing teams [ 21 , 22 , 23 ].

Role distinctions between licensed vocational-trained nurses (VNs) and Bachelor of Science-trained nurses (BNs) has been heavily debated since the introduction of the higher nurse education in the early 1970s, not only in the Netherlands [ 24 , 25 ] but also in Australia [ 26 , 27 ], Singapore [ 20 ] and the United States of America [ 28 , 29 ]. Current debates have focused on the difficulty of designing distinct nursing roles. For example, Gardner et al., revealed that registered nursing roles are not well defined and that job profiles focus on direct patient care [ 30 ]. Even when distinct nursing roles are described, there are no proper guidelines on how these roles should be differentiated and integrated into daily practice. Although the value of differentiating nursing roles has been recognized, it is still not clear how this should be done or how new nursing roles should be embedded in daily nursing practice. Furthermore, the consequences of these roles on nursing work has been insufficiently investigated [ 31 ].