Center for Teaching

Case studies.

Print Version

Case studies are stories that are used as a teaching tool to show the application of a theory or concept to real situations. Dependent on the goal they are meant to fulfill, cases can be fact-driven and deductive where there is a correct answer, or they can be context driven where multiple solutions are possible. Various disciplines have employed case studies, including humanities, social sciences, sciences, engineering, law, business, and medicine. Good cases generally have the following features: they tell a good story, are recent, include dialogue, create empathy with the main characters, are relevant to the reader, serve a teaching function, require a dilemma to be solved, and have generality.

Instructors can create their own cases or can find cases that already exist. The following are some things to keep in mind when creating a case:

- What do you want students to learn from the discussion of the case?

- What do they already know that applies to the case?

- What are the issues that may be raised in discussion?

- How will the case and discussion be introduced?

- What preparation is expected of students? (Do they need to read the case ahead of time? Do research? Write anything?)

- What directions do you need to provide students regarding what they are supposed to do and accomplish?

- Do you need to divide students into groups or will they discuss as the whole class?

- Are you going to use role-playing or facilitators or record keepers? If so, how?

- What are the opening questions?

- How much time is needed for students to discuss the case?

- What concepts are to be applied/extracted during the discussion?

- How will you evaluate students?

To find other cases that already exist, try the following websites:

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science , University of Buffalo. SUNY-Buffalo maintains this set of links to other case studies on the web in disciplines ranging from engineering and ethics to sociology and business

- A Journal of Teaching Cases in Public Administration and Public Policy , University of Washington

For more information:

- World Association for Case Method Research and Application

Book Review : Teaching and the Case Method , 3rd ed., vols. 1 and 2, by Louis Barnes, C. Roland (Chris) Christensen, and Abby Hansen. Harvard Business School Press, 1994; 333 pp. (vol 1), 412 pp. (vol 2).

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Case Study in Education Research

Introduction, general overview and foundational texts of the late 20th century.

- Conceptualisations and Definitions of Case Study

- Case Study and Theoretical Grounding

- Choosing Cases

- Methodology, Method, Genre, or Approach

- Case Study: Quality and Generalizability

- Multiple Case Studies

- Exemplary Case Studies and Example Case Studies

- Criticism, Defense, and Debate around Case Study

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Mixed Methods Research

- Program Evaluation

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Gender, Power, and Politics in the Academy

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- Non-Formal & Informal Environmental Education

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Case Study in Education Research by Lorna Hamilton LAST REVIEWED: 21 April 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 27 June 2018 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0201

It is important to distinguish between case study as a teaching methodology and case study as an approach, genre, or method in educational research. The use of case study as teaching method highlights the ways in which the essential qualities of the case—richness of real-world data and lived experiences—can help learners gain insights into a different world and can bring learning to life. The use of case study in this way has been around for about a hundred years or more. Case study use in educational research, meanwhile, emerged particularly strongly in the 1970s and 1980s in the United Kingdom and the United States as a means of harnessing the richness and depth of understanding of individuals, groups, and institutions; their beliefs and perceptions; their interactions; and their challenges and issues. Writers, such as Lawrence Stenhouse, advocated the use of case study as a form that teacher-researchers could use as they focused on the richness and intensity of their own practices. In addition, academic writers and postgraduate students embraced case study as a means of providing structure and depth to educational projects. However, as educational research has developed, so has debate on the quality and usefulness of case study as well as the problems surrounding the lack of generalizability when dealing with single or even multiple cases. The question of how to define and support case study work has formed the basis for innumerable books and discursive articles, starting with Robert Yin’s original book on case study ( Yin 1984 , cited under General Overview and Foundational Texts of the Late 20th Century ) to the myriad authors who attempt to bring something new to the realm of case study in educational research in the 21st century.

This section briefly considers the ways in which case study research has developed over the last forty to fifty years in educational research usage and reflects on whether the field has finally come of age, respected by creators and consumers of research. Case study has its roots in anthropological studies in which a strong ethnographic approach to the study of peoples and culture encouraged researchers to identify and investigate key individuals and groups by trying to understand the lived world of such people from their points of view. Although ethnography has emphasized the role of researcher as immersive and engaged with the lived world of participants via participant observation, evolving approaches to case study in education has been about the richness and depth of understanding that can be gained through involvement in the case by drawing on diverse perspectives and diverse forms of data collection. Embracing case study as a means of entering these lived worlds in educational research projects, was encouraged in the 1970s and 1980s by researchers, such as Lawrence Stenhouse, who provided a helpful impetus for case study work in education ( Stenhouse 1980 ). Stenhouse wrestled with the use of case study as ethnography because ethnographers traditionally had been unfamiliar with the peoples they were investigating, whereas educational researchers often worked in situations that were inherently familiar. Stenhouse also emphasized the need for evidence of rigorous processes and decisions in order to encourage robust practice and accountability to the wider field by allowing others to judge the quality of work through transparency of processes. Yin 1984 , the first book focused wholly on case study in research, gave a brief and basic outline of case study and associated practices. Various authors followed this approach, striving to engage more deeply in the significance of case study in the social sciences. Key among these are Merriam 1988 and Stake 1995 , along with Yin 1984 , who established powerful groundings for case study work. Additionally, evidence of the increasing popularity of case study can be found in a broad range of generic research methods texts, but these often do not have much scope for the extensive discussion of case study found in case study–specific books. Yin’s books and numerous editions provide a developing or evolving notion of case study with more detailed accounts of the possible purposes of case study, followed by Merriam 1988 and Stake 1995 who wrestled with alternative ways of looking at purposes and the positioning of case study within potential disciplinary modes. The authors referenced in this section are often characterized as the foundational authors on this subject and may have published various editions of their work, cited elsewhere in this article, based on their shifting ideas or emphases.

Merriam, S. B. 1988. Case study research in education: A qualitative approach . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

This is Merriam’s initial text on case study and is eminently accessible. The author establishes and reinforces various key features of case study; demonstrates support for positioning the case within a subject domain, e.g., psychology, sociology, etc.; and further shapes the case according to its purpose or intent.

Stake, R. E. 1995. The art of case study research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Stake is a very readable author, accessible and yet engaging with complex topics. The author establishes his key forms of case study: intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Stake brings the reader through the process of conceptualizing the case, carrying it out, and analyzing the data. The author uses authentic examples to help readers understand and appreciate the nuances of an interpretive approach to case study.

Stenhouse, L. 1980. The study of samples and the study of cases. British Educational Research Journal 6:1–6.

DOI: 10.1080/0141192800060101

A key article in which Stenhouse sets out his stand on case study work. Those interested in the evolution of case study use in educational research should consider this article and the insights given.

Yin, R. K. 1984. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . Beverley Hills, CA: SAGE.

This preliminary text from Yin was very basic. However, it may be of interest in comparison with later books because Yin shows the ways in which case study as an approach or method in research has evolved in relation to detailed discussions of purpose, as well as the practicalities of working through the research process.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Grounded Theory

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Research

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Learning Strategies

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Literature Reviews

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Narrative Research in Education

- Native American Studies

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Politics of Education

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Response to Intervention

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Science Education

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-sex Education

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Science and Education Research

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development

- Teacher Unions and Associations

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Technologies, Teaching, and Learning in Higher Education

- Technology Education in Early Childhood

- Technology, Educational

- Technology-based Assessment

- The Bologna Process

- The Regulation of Standards in Higher Education

- Theories of Educational Leadership

- Three Conceptions of Literacy: Media, Narrative, and Gamin...

- Tracking and Detracking

- Traditions of Quality Improvement in Education

- Transformative Learning

- Transitions in Early Childhood Education

- Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities in the Unite...

- Understanding the Psycho-Social Dimensions of Schools and ...

- University Faculty Roles and Responsibilities in the Unite...

- Using Ethnography in Educational Research

- Value of Higher Education for Students and Other Stakehold...

- Virtual Learning Environments

- Vocational and Technical Education

- Wellness and Well-Being in Education

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Young Children and Spirituality

- Young Children's Learning Dispositions

- Young Children's Working Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.14.133]

- 185.66.14.133

Advertisement

Face to face or blended learning? A case study: Teacher training in the pedagogical use of ICT

- Published: 17 June 2022

- Volume 27 , pages 12939–12967, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Charalampos Zagouras 1 , 2 ,

- Demetra Egarchou 1 ,

- Panayiotis Skiniotis 1 &

- Maria Fountana 1

4435 Accesses

9 Citations

Explore all metrics

We are experiencing a transitional period in education: from the traditional, face to face teaching model to new teaching and learning models that apply modern pedagogical approaches, utilize technological achievements and respond to current social needs. For a number of reasons including the recent pandemic covid-19 situation, technology enhanced distance learning, seems to gain ground against traditional face to face teaching and in fact, in a sharp way. Acknowledging that changes in education need time, research and careful steps in order to be successfully applied and established at large scale, in this paper we attempt to compare face to face (“traditional”) teacher training with teacher training through a blended learning approach/ model. The latest combines characteristics of both face to face and distance learning models. The case study is based on a large-scale in-service teacher training initiative which has been taking place in Greece for over a decade to train teachers in the utilization and application of digital technologies in the teaching practice (i.e. B-Level ICT Teacher Training) . The B-Level ICT Teacher Training was initially based exclusively on face to face teaching but it was later adapted to a specially designed blended learning model which combined both face to face and synchronous distance sessions, accompanied by asynchronous activities and supported by specific e-learning platforms and tools. The comparison refers to the effectiveness of the two models/ approaches, as it derives from teacher trainees’ performance, especially in the framework of the certification procedure that takes place through nationwide, independent exams that follow the training and assesses the relevant knowledge and skills acquired. Research findings point out better performances of a small or marginal scale for the teachers of various specialties who participated in blended learning teacher training programs compared to those who participated in traditional teacher training programs. Actually, it is shown that blended learning model trainees i) feel more comfortable to participate in the exams for the certification of knowledge and skills acquired, ii) have some better success rate and iii) get a bit higher grades in these exams. Thus, it can be argued that learning outcomes of the blended learning application in this teacher training initiative, overstep those of the “traditional” model in a small scale and with some slight differentiations among teacher specialties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Training Elementary Teachers in Vietnam by Blended Learning Model

The Blended Learning Pedagogical Model in Higher Education

The Blended Learning Concept e:t:p:M@Math: Practical Insights and Research Findings

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 the present situation.

It seems that we are experiencing a transitional period in education. Actually, a transition from the traditional, face to face teaching model to new teaching and learning models that apply modern pedagogical approaches, utilize technological achievements and respond to current social needs.

In this framework, for a number of reasons (e.g. technology evolution, costing issues, special needs and situations) distance learning seems to gain ground against traditional face to face teaching (Kentnor, 2015 ; Kemp & Grieve, 2014 ). In fact, during the current unpleasant situation of the Covid-19 pandemic (Kusmaryono et al., 2021 ; Dhawan, 2020 ; Favale et al., 2020 ) the massive application of distance learning was enforced using digital technologies, in most cases without the necessary preparatory work, even in audiences where such a method is not generally considered as appropriate (e.g. school pupils).

On the other hand, changes in education need time in order to be successfully applied and established, prior research is also needed, whereas careful steps should be followed for the application of any change or innovation at large scale.

The study of a large scale teacher training program which a) was initially designed and successfully implemented for face to face teaching approach and subsequently, b) was carefully transformed for the blended learning approach maintaining some of the valuable trainer-trainees physical/synchronous contact and then, c) applied utilizing synchronous and asynchronous distance learning digital tools, may provide us with some interesting conclusions for the comparative learning results of these approaches and suggestions on how technology can effectively and essentially contribute to the learning process.

1.2 Related work

The term Blended Learning, often seen as used with ambigious meaning (Hrastinski, 2019 ) that may signify the combination of two or more teaching or pedagogical approaches, media, contexts or learning objectives and is at times questioned for its aptness as a term (Oliver & Trigwell, 2005 ), is often described as involving a mix of online and face to face teaching (Graham et al., 2014 ; Driscoll, 2002 ). It is with this later definition that Blended learning is being adopted in the current case study, i.e. as a model that combines the characteristics of face to face and distance learning model and which can be utilized for various educational audiences, including training actions for teachers concerning their professional development. The blended learning approach for the teacher training program that concerns our case study in this paper, as described in detail in Section 2.1 , utilizes digital technologies and includes face to face and distance synchronous teaching, as well as asynchronous learning activities.

Actually, training actions, especially those addressing teachers, are implemented either a) face to face (traditional teaching), or b) from a distance, applying synchronous and/or asynchronous teaching and learning methodologies, using digital technologies (online learning), as well as c) combining of all the above-mentioned approaches/ models (blended learning).

Training actions concerning the utilization of digital technologies in school have special characteristics, since the use of digital tools, software and environments is included in the training subject itself, while participants’ interaction and collaboration is needed. Furthermore, the knowledge to be gained and the skills to be acquired by the teacher trainees, in order to integrate digital technologies into their classes, are complicated since they effectively combine disciplines, technological media and pedagogical approaches in everyday teaching practice (Psillos, 2014 ).

These characteristics introduce additional issues, difficulties and challenges when distance education methodologies are selected, that may affect the training outcomes. Thus, some questions arise about the most effective teacher training method in order for participating teachers to meet the learning objectives and acquire the expected skills and competences.

Although many studies have been conducted on the application of distance education methodologies using digital media (online learning) (Moore et al., 2010 ), research on blended learning is scarce and most commonly addresses six (6) thematic categories: design issues, blended model as an education strategy, factors for effectiveness, evaluation, methodology issues, literature review for various levels of education (Zhang & Zhu, 2017 ).

Some research referring to specific case studies in various educational frameworks and to the comparison of different models, can be found in the above-mentioned thematic category of methodology issues. For example, comparative study between traditional and blended learning model applied to K-12 pupils in N. Zealand, based on learning outcomes and on the perceptions of both pupils and their teachers for the model they followed (traditional or blended learning model) didn’t show any difference in pupils’ assessed work between the two groups. On the contrary, there were differences in their perceptions regarding individual learning issues, connectedness, enjoyment and teacher support (Smith, 2013 ). Other indicative comparative studies concern a) English Language teaching for Mechanical Engineering students in Serbia, where higher “involvement” and higher marks were shown for blended learning model students (Šafranj, 2013 ), b) A course on Physical Education in Early Childhood in the Democritus University of Thrace, Greece, where significant differences were revealed in students’ performance in the case of blended learning (Vernadakis et al., 2012 ), c) Courses on Medication administration for new nurses, where it was shown that a blended learning approach is useful and effective for this kind of education programs (Sung et al., 2008 ).

Furthermore, distance e-learning systems and services for covering the educational needs of remote and isolated areas have been developed and successfully tested, for instance: Teaching English Language in Small Remote Primary Schools (Egarchou et al., 2007 ) and Providing Lifelong Learning opportunities to adults living in small remote regions (Hadzilacos et al., 2009 ).

It has also been demonstrated “that in recent applications, purely online learning is equivalent to face to face instruction in effectiveness, and blended learning approaches have been more effective than instruction offered entirely in face to face mode” (Means et al., 2013 ).

More specifically, in studies concerning the application of blended learning model in teacher education or training actions, the feasibility of blending—integrating interactive e-learning and contact learning was shown, especially when learners construct professional knowledge and skills (Kupetz & Ziegenmeyer, 2005 ). It was also indicated that the combination of different training models (in-labs and on-line training, workshops etc.), was perceived as a challenging innovation by teachers and attracted their interest (Mouzakis et al., 2012 ). Moreover, specific issues and difficulties have been met for the design of a blended learning model for teacher training on ICT (Dagdilelis, 2014 ). In parallel, the design and pilot implementation of such a model for teachers of natural sciences (Psillos, 2014 ) and the respective conceptual design of the model for primary school teachers (Komis et al., 2014 ) were described and discussed. Regarding teachers’ perceptions on the integration of digital technologies in their lessons, significant difference, i.e. more positive attitude, has been observed among the teachers trained for this subject, through blended learning approaches (Qasem & Nathappa, 2016 ). Finally, the implementation of blended learning approaches sets specific additional requirements for trainers and trainees as well as for the development of the training material and activities etc., in order to reach the expected results (Byrka, 2017 ).

Nonetheless, there are still limited studies concerning the implementation of blended learning model in teacher education or training and thus, more empirical studies are needed as they could help to stimulate reflections on effective strategies for such a model design and implementation (Keengwe & Kang, 2013 ). This need becomes more imperative especially since the effectiveness of various schemas /structures for blended learning models depends on the specific characteristics of the program, the implementation conditions and the pedagogical approaches applied (Kim et al., 2015 ). Moreover, multiple parameters affect a successful implementation of a blended learning model such as the subject matter, the competences of the instructors, the quality of educational material and learning activities, the support provided for the learning procedure etc. (Lim, 2002 ).

1.3 About this paper

The implementation of the B-Level ICT in-service teacher training in the utilization and application of digital technologies in the teaching practice , a large-scale training action, taking place in Greece for more than ten years, allowed us to compare in this research, the traditional training model with the blended training model as it was designed and implemented in this framework, and to evaluate their results. This comparison refers to the effectiveness of the two models/ approaches, as it derives from teacher trainees’ performances, especially in the framework of the certification procedure regarding the knowledge and skills acquired, through exams that follow the training.

Τhe following sections of this paper include: a description of the research environment, referring to a) the design and implementation of the B-Level ICT in-service teacher training through both the traditional / face to face and the blended learning model, b) the certification procedure which follows, as well as c) the research methodology and d) information about the data that were used (Section 2 ), the results of the two models comparative study in the present framework (Section 3 ) and finally, conclusions of our work in this research study (Section 4 ).

2 The research framework and methodology

2.1 the b-level ict teacher training, the “traditional” and the blended learning model.

The “B-Level ICT Teacher Training” or “In-service teacher training in the utilization and application of information and communication technologies (ICT) in the teaching practice” (full title) is a long-lasting and popular teacher training program of the Greek Ministry of Education, offered to Greek teachers since 2008 ( https://e-pimorfosi.cti.gr , http://b-epipedo2.cti.gr ).

This teacher training, in the form it was implemented from 2010 until 2015 where this study refers to, addressed teachers of the main specialties i.e. Language, Mathematics, Natural Science, Informatics, Primary School and Kindergarten teachers.

The main aim of B-Level ICT teacher training is to provide teachers with the knowledge and skills needed and to help them create a certain stance towards:

the pedagogical utilization of digital technologies (e.g. educational software and tools, educational platforms, school digital infrastructure etc.) in the classroom

being able to adapt new technology developments into their educational practice (i.e. not depend on specific tools and technologies)

Training content and objectives put special emphasis on the design of educational activities and scenarios, since their role in the integration of ICT in class is considered as significant and necessary. Furthermore, the “in-class application of ICT” phase of the program , during which trainees put into practice the knowledge and skills they acquire, by implementing educational activities using ICT in their classes with their pupils, constitutes a mandatory and integral part of the teacher training itself.

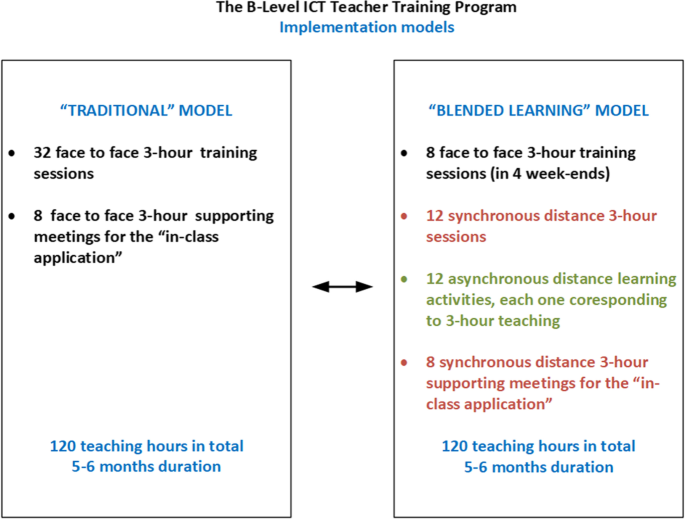

The training program had a duration of 5–6 months, including 96 teaching hours, accompanied by 24 more hours of supporting meetings for the preparation and review of “in-class application of ICT” activities Fig. 5 . Trainers who undertook training sessions, are highly qualified teachers, i.e. coming from teachers’ community themselves, selected through an open process, in order to attend a specialized long educational program (380 h) in Universities and subsequently become certified for the role of “B-Level ICT Teacher Trainer” through demanding exams.

At the beginning, the traditional training model was followed, including entirely face to face sessions in Training Centers (Fig. 1 ), which are usually schools that provide for that purpose their computer labs, as well as support staff (e.g. technical support, program administration) during after school hours. In this framework, 2.057 training programs were implemented between 2010 and 2015, each of them addressing a group of 10–12 teacher trainees of the same or similar specialty.

Snapshots from the implementation of B-Level ICT Teacher Training—Face to Face sessions

However, through that method, it was not possible to cover the training needs in small remote and isolated areas, where there aren’t enough trainees (of the same specialty) to form a group or there is no trainer or training center available and thus, there is no possibility for implementing traditional – face to face training programs.

Thus, for covering remote or isolated, hard to reach areas (e.g. small islands, mountainous areas), as well as in the case of lack of training facilities, a blended learning model , appropriately designed to serve the specific training needs and objectives, was applied to a number of B-Level ICT training programs.

Interaction, effective communication and collaboration between trainer and trainees, as well as among the trainees themselves, constitute a significant asset of the B-Level ICT teacher training program, mainly achieved through the face to face contact and direct interaction during the lessons in the Training Centers, taking place twice a week, in case of traditional training programs. The pedagogical approach of the training program and the nature of its content, which includes lab classes and workshops (e.g. educational software and tools’ learning), discussions, exchange of experiences, ideas and opinions on educational scenarios etc., as an integral part of the learning process, make the above elements extremely necessary. This frequent contact, the discussions, the exchange of experiences, ideas and opinions contribute to building a team spirit and finally, to the creation of a learning community of practice, which usually remains active even after the end of the training program.

In typical distance education models the above elements are absent or difficult to be achieved. However, they are considered as crucial for the effectiveness of the B-Level ICT teacher training and thus, in the design of the blended learning model emphasis was put on keeping them, through regular (at least, on a weekly basis) synchronous distance learning sessions, using special tools (synchronous distance learning platform), as well as through a few number of face to face training sessions (Fig. 2 ).

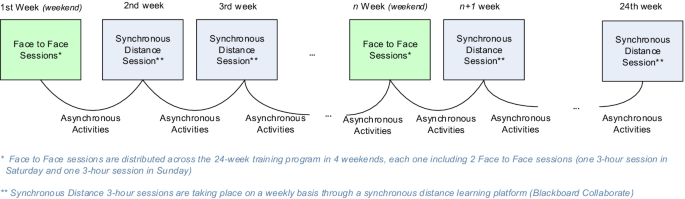

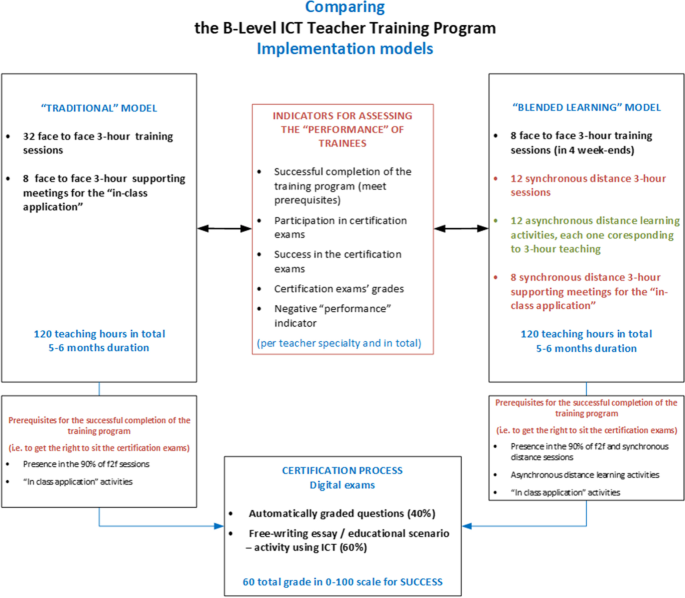

Schematic representation of the B-Level ICT Teacher Training

Every blended training program consisted of a group of 10–12 teachers of the same or similar specialty and had a duration of 24 weeks. Training sessions were taking place either face to face in the Training Center or synchronously from a distance (through the synchronous distance learning platform) and were accompanied by asynchronous activities across the course. In the same way as in the traditional B-Level ICT teacher training model, after the first 8 weeks, “in-class application of ICT” activities were introduced through the weekly “supporting meetings”, where the trainees were coached by their trainers for the implementation of educational activities using ICT in their classes with their pupils, and/or they were discussing on the outcomes of them after their application at school Fig. 5 .

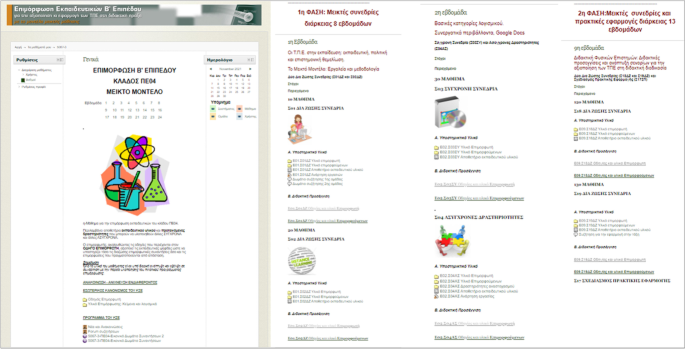

Face to face training sessions were taking place in four (4) weekends (3 h on Saturday and 3 h on Sunday, each weekend). Synchronous distance training sessions were taking place on a weekly basis, through the synchronous distance learning platform Blackboard Collaborate (Fig. 3 ), while the asynchronous activities were carried out using the Learning Management system (LMS) Moodle i.e. assignments, upload of work, assessing and grading, communication and collaboration etc.(Fig. 4 ). LMS was also used for the delivery of the training material. Tools for virtual class management and operation like video conferencing, application sharing, whiteboard, chat, voting, recording etc. were also available by the synchronous distance learning platform.

A Snapshot from a synchronous distance B-Level ICT Training session—Screenshot of the synchronous distance learning platform supporting the B-Level ICT blended learning model

Screenshots of the Learning Management System supporting the B-Level ICT Blended Learning Model (course materials, asynchronous activities etc.)

Technical support was offered to the trainers and to the trainees by the technical staff of the training center during both the face to face meetings and the synchronous distance sessions. Help was also provided for various preparatory actions e.g. educational tools and software installation in trainees’ laptops, connection to the platforms.

Consequently, the trainees of a blended training program were participating in face to face meetings of a total duration of 24 h, distributed in the course appropriately (at the beginning, in the middle and before the end). That way the contact and interaction elements that were previously mentioned, could create conditions towards ensuring the effectiveness of the distance communication and collaboration in the weekly synchronous sessions and asynchronous activities that followed, given also the technical support offered by the training center staff (Fig. 5 ).

The B-Level ICT teacher training program—implementation models

The B-Level ICT Blended Training model was applied in a small number of programs, in two phases, in 2013–2014 time period. First pilot phase included ten (10) programs (two for each teacher specialty), that were implemented in order to test and improve the methods, the tools and the training material (formative evaluation). This phase was followed by a second one, including forty-five (45) programs, in order to offer the possibility of a further study of the results, before applying the model in a wider scale.

2.2 The B-Level ICT certification

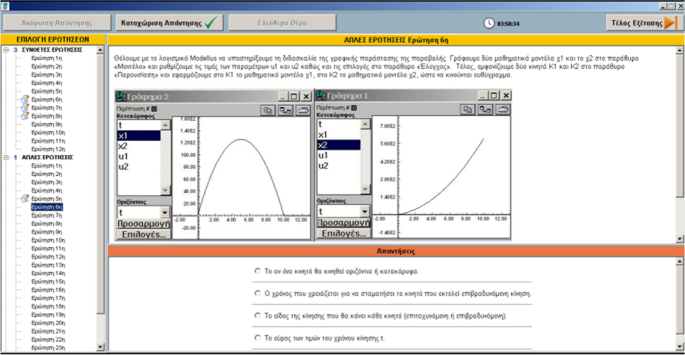

Teacher Training is followed by a certification process regarding the knowledge and skills acquired by teacher trainees, through special, independent, nationwide, digital exams which take place in University Computer Labs acting as Certification Centers (Fig. 6 ).

Snapshot from a B-Level ICT certification program (Teacher trainees sitting digital exams)

The aim of the certification process is to find out whether the teachers who attended the B-Level ICT Teacher Training, have gained the theoretical knowledge regarding the pedagogical utilization of ICT and have acquired the skills needed to be able to organize their teaching (in their specific specialty subjects) using digital technology tools.

The right to participate in the exams was offered only to the trainees who had successfully completed the training program, according to specific prerequisites regarding their presence in lessons (at least 90%), the “in-class application” activities using ICT, as well as, especially in the case of blended training model for the period studied in this paper, the elaboration of specific project activities (e.g. the development of educational scenarios using ICT) at the asynchronous phase of the course.

The computer-based exams (Fig. 7 ) have a duration of 4 h maximum and include two parts: a first part with automatically graded questions (e.g. multiple-choice questions) and a second one, concerning the development of an educational activity – scenario on a specific topic of a discipline in relation to their specialty (an essay, anonymously graded by a body of assessors consisting of B-Level Teacher Trainers) utilizing ICT.

Screenshot of the software application supporting the B-Level ICT certification process—digital exams

In the first part of the exam, a test is assigned to each candidate who is asked to answer a number of questions of graduated difficulty on the training cognitive subjects. The questions are answered through a specialized certification software application and they are automatically graded. The development of questions follows specific rules and quality assurance processes, in order for a big test item bank to be constructed, which feeds the tests (Christakoudis et al., 2011 ). Some questions and their alternative answers are extremely simple while other ones are more complicated i.e. concerning a combination of concepts, understanding of specific situations, scenarios for software applications etc. Each candidate has to take a separate test i.e. including different but equivalent questions selected randomly from the above-mentioned bank in a way that assures entirety, variety in types of questions, representation of the specific cognitive subjects, objectivity for the process, diversity of the tests while keeping the same difficulty level (Zagouras, 2005 ). The test item bank is frequently renewed following a specific process which includes: a) the addition of new questions in each new certification period, b) the removal of questions after their usage in a specific number of tests, c) improvement or replacement of questions according to a formative evaluation of the test results.

In the second part of the exam, the candidates are asked to free-write an essay on a specific theme concerning a lesson plan and its in-class application using ICT. This theme addresses all concepts that the teacher trainees faced during the training, mainly through the projects and activities they carried out. It mainly concerns educational scenarios and activities where educational or other software tools and environments were used as a significant part of the B-Level ICT Teacher Training process. These themes are only used once in the exams and are totally renewed for each new certification period.

The final certification grade derives from the formula: G cert = 0,40*G partA + 0,60*G partB , where G partA and G partB refer respectively to the grades of the first and the second part of the exam, as described above. The participation of a teacher trainee in the exams is successful so that she/he is considered to be certified for the specific B-Level ICT knowledge and skills, if the final certification grade she/he got is at least 60 in 0–100 scale.

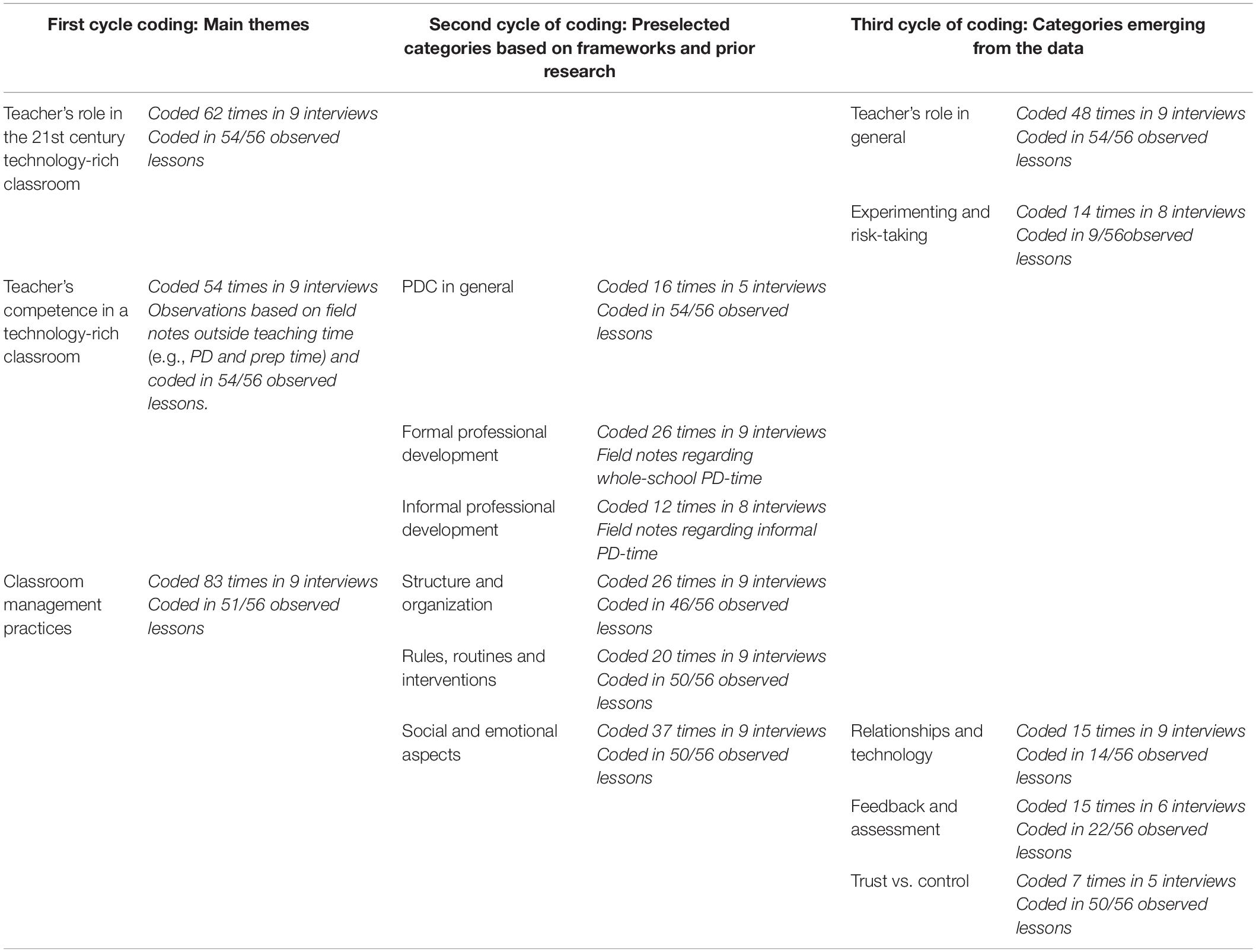

2.3 The methodology

This research was carried out by scientific staff of the organization responsible for the implementation of B-Level ICT Teacher training on behalf of the Greek Ministry of Education. It was carried out as part of a broader attempt to compare the B-Level ICT “traditional” and “blended learning” models, before proceeding with the application of the Blended learning model at a wider scale, acknowledging that changes in well-established education processes should be gradually and carefully applied in order to be successful.

The aim of this specific research is to study whether the approach/model i.e. the methodology followed for the implementation of the teacher training (traditional or blended learning model), affects the “performance” of the trainees, in the framework of their participation in the training program and more specifically, in the certification process of the knowledge and skills acquired that follows the training. In this framework the research questions attempted to be answered include: a) How are the rates of the trainees who successfully completed the training program affected by the different training approaches (i.e. the traditional versus the blended learning model)? b) How are the percentages of the trained teachers who participated successfully in the training program and then sat the exams compared in between the two approaches? c) How the success rates at the certification exams of the above two approaches are compared? d) How are the grades achieved at the exams compared in between the two categories of trainees? e) How is certain “poor” performance of the trainees compared in between the two models? f)Is there any difference on the above “performance” factors between the various teacher specialties?

Therefore, the data examined as indicators for the “performance” of the teacher participants in the training and certification process refer to (Fig. 8 ): a) the successful or no completion of the training program, i.e. to the fulfillment of the minimum requirements such as the presence in the training sessions, the implementation of “in-class application” activities using ICT etc., in order to get the right to participate in the certification exams, b) to the participation in or abstention from the exams, as well as to c) the grades achieved at the certification exams (automatically graded questions and free-writing theme/ essay on an educational scenario / activity utilizing ICT).

Comparing the B-Level ICT teacher training program implementation models

For measuring and comparatively processing the above indicators, we used data from all the B-Level ICT Training programs implemented in 2010–2015 time period (of both traditional and blended learning model) all over Greece, where 23.689 teachers of “basic” specialties (Language, Mathematics, Natural Science, Informatics, Primary School and Kindergarten Teachers) participated.

Actually, it was not only a sample of data concerning a number of teacher trainees that was examined, but all the data concerning the trainees who participated in the above-mentioned training initiative in total. The authors of this paper, coming from the organization responsible for the implementation of B-Level ICT Teacher training, were able to access all the data needed for this research, through the Management Information System (MIS) supporting this large scale initiative. In specific, they collected and analysed the following data per teacher specialty and training model: a) the total number of trainees registered in the teacher training course, b) the total number of trainees who successfully completed the training course, c) the total number of trainees who participated in the certification, d) the grades of the trainees in these exams (and consequently the certification result: success or fail).

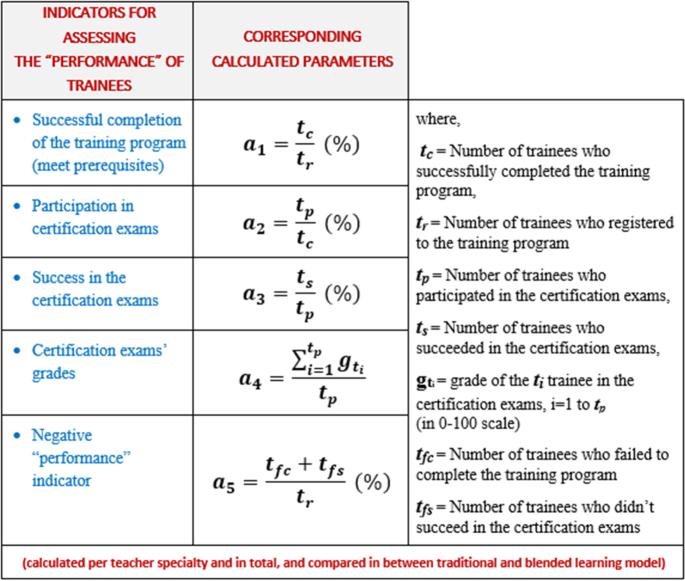

Based on the above data, the aforementioned indicators were examined through the comparison of the corresponding parameters presented in the following table (Fig. 9 ).

Indicators for assessing the "performance" of trainees and corresponding parameters calculated and compared in between traditional and blended learning model

The comparative study of these parameters and indicators in between the two models (traditional and blended learning model) both in total and per teacher specialty, actually answers to the corresponding research questions above, and leads to the results of this research as presented in the following section.

3 Comparative assessment of the trainees’ “performance” – results

The results of the research are presented below per indicator and per teacher specialty, as well as in total, for all teacher specialties.

3.1 Successful completion of the program

As aforementioned, in order for a teacher trainee to have successfully completed the B-Level ICT Training program and thus be eligible to participate in the respective certification exams, it is required that he/she is present in 90% of the training sessions (face to face and synchronous distance ones) as well as to have carried out a number of “in class application” activities using ICT. Especially in the case of the blended training model, a number of homework activities (e.g. the development of educational activities/ scenarios utilizing ICT) in the framework of the asynchronous part of the program, were also necessary.

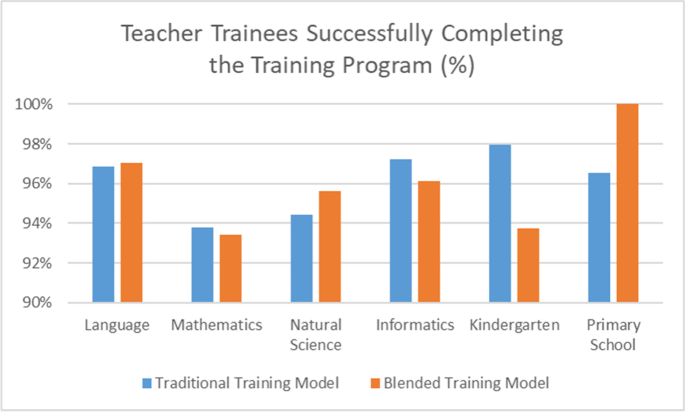

The percentage of the teacher trainees who successfully completed the training program per teacher specialty and training model (parameter α 1 in Fig. 9 ), is presented in the following Table 1 and Fig. 10 .

Percentage of teacher trainees who successfully completed the training program

The percentage of the trainees who successfully completed the training program is high, over 93% for all the teacher specialties. However, we can see some small differences between the trainees of blended training programs and those of traditional ones, indicating a small lead of the blended training model for the Primary School, Physics and Language Teachers (up to 3,5 percentage units, in the case of Primary Teachers), as well as a small lead of traditional training model for Kindergarten, Informatics and Mathematics teachers (up to 4,2 percentage units, in the case of Kindergarten teachers).

3.2 Participation in certification exams

The teacher trainee who successfully completes the training program gets the right to participate in the certification exams. As this certification contributes to the professional development of the teachers and their placement in higher positions of responsibility (as a criterion), teachers who successfully complete this training program wish, in general, to get the B-Level ICT certification and thus, they sit the respective exams. The abstention from the exams may show that the trainee feels insecure and unconfident regarding the respective knowledge and skills expected to have been acquired, and for that reason this element was selected as one of the indicators of the trainees’ “performance”.

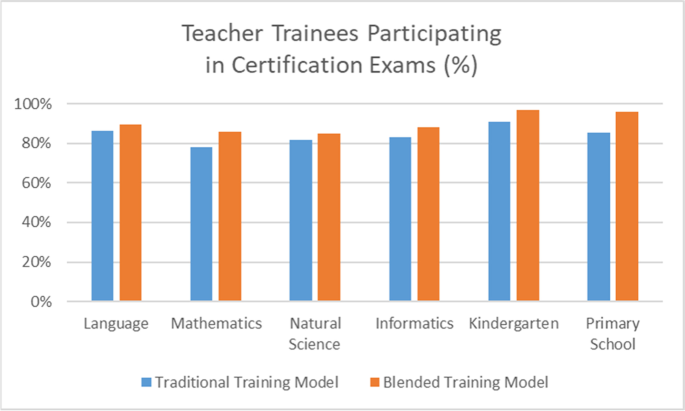

The percentage of the teacher trainees who participated in the certification exams (parameter α 2 in Fig. 9 ), per teacher specialty and training model is presented in the following Table 2 and Fig. 11 .

Percentage of teacher trainees who participated in certification exams

The percentage of the teacher trainees who sat the exams ranges from 78 to 90% in the case of the traditional training model, and from 85 to 97% in the case of the blended training model. Thus, a noticeably higher percentage was found in the case of the trainees of blended learning programs for all teacher specialties, with the Primary School teachers on top, with a difference of 10,54 percentage units, followed by the Mathematics teachers, with a difference of 7,69 percentage units and the Language teachers on bottom, with a difference of 3,11 percentage units.

3.3 Success in the certification exams

As aforementioned, the participation of a teacher trainee in the certification exams is considered as successful if the final certification grade, deriving from the grades of the first part (automatically graded questions) and the second part (free-writing theme/ essay on an educational scenario / activity utilizing ICT) of the certification exam, she/he got is at least 60 in 0–100 scale.

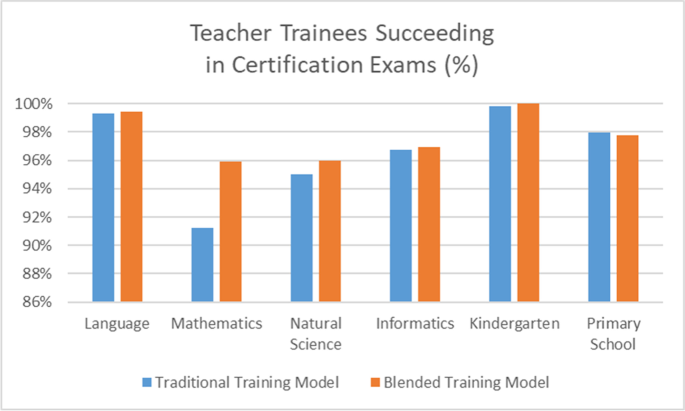

The percentage of the teacher trainees who succeeded in the certification exams (i.e. those who got final certification grade > = 60) per teacher specialty and training model (parameter α 3 in Fig. 9 ) is presented in the following Table 3 and Fig. 12 .

Percentage of teacher trainees who succeeded in certification exams

The percentage of the teacher trainees who succeeded in the certification exams is generally high (> 91%), regardless of the teacher specialties and the training model. Besides, in the case of the blended training model a minor overstepping is observed (less than one percentage unit), with a positive exception at the Mathematics teachers where the percentage is 4,65 units higher and a negative exception at the Primary School teachers, where it seems that the percentage for the traditional model is marginally greater (0,24 percentage units).

3.4 Certification exams’ grades

The grades achieved by the teacher trainees in the certification exams and more specifically, both the final certification grade and the grade of each part of the exam (automatically graded questions and free-writing theme) distinctly (since each part corresponds to different knowledge and/or skills – competences), were the next indicators considered appropriate to be examined.

For that reason, the average (AVG) of grades of all the trainees who participated in the certification exams, was calculated per teacher specialty and training model.

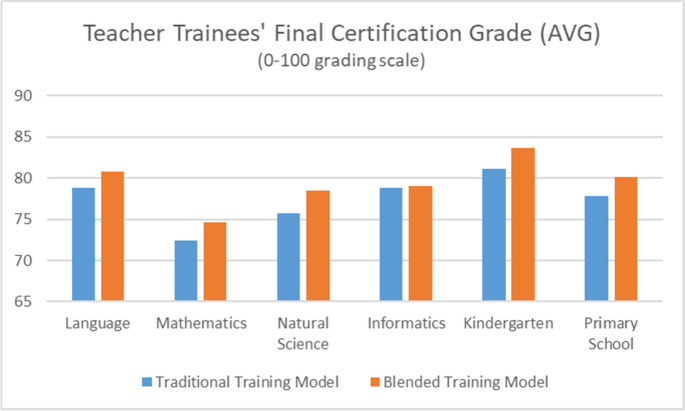

The average of all trainees’ final certification grades (regardless of the final result), per teacher specialty and training model (parameter α 4 in Fig. 9 ) is presented in the following Table 4 and Fig. 13 .

Average of teacher trainees final certification grades

It is noted that the blended learning model trainees got 2–3 units better final certification grade on average (in scale 0–100), with an exception in the case of Informatics teachers, where this difference is only 0,16 units.

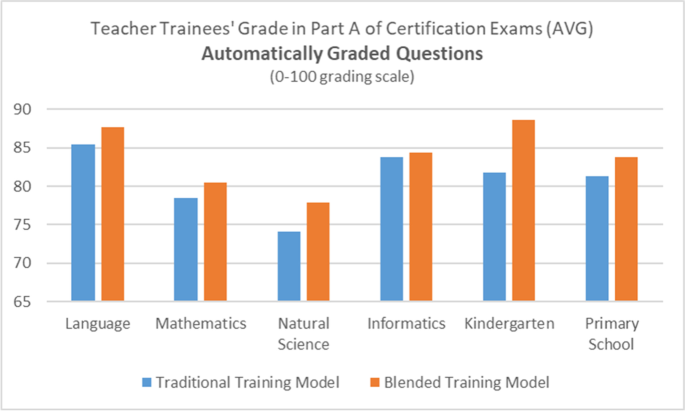

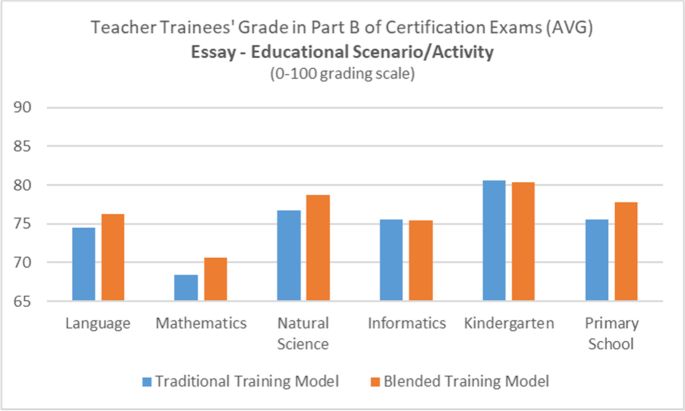

Below, the average of all trainees’ grades corresponding to the first part (automatically graded questions) and to the second part (free-writing theme/ educational scenario – activity utilizing ICT) of the certification exam are presented distinctly, per teacher specialty and training model (Table 5 , Fig. 14 , Table 6 , Fig. 15 ).

Average of teacher trainees' grades in Part A of certification exams (Automatically Graded Questions)

Average of teacher trainees' grades in Part B of certification exams (Essay—Educational Scenario)

According to this data, the situation with the averages of all trainees’ grades for the first or the second part seems similar to the one of the final certification grades, as no essential differentiation to this is observed. More specifically, both first and second part average grades are similarly 2 – 4 units higher (in scale 0–100) in the case of the blended learning model trainees, with a positive exception at Kindergarten teachers for the first part of the certification exam where a higher overstepping in blended training model is observed (6,75 units difference) and for the second part of the certification exam, negative exceptions at Informatics and Kindergarten teachers where a marginal overstepping of the traditional training model is observed (0,16 and 0,21 units differences, respectively).

3.5 Negative “Performance” indicator

Obviously, unsuccessful completion of the training program or unsuccessful participation in the certification exams mean a negative “performance” for the respective training participants. Thus, the sum of the percentage of the teacher trainees who didn’t successfully complete the training program and the percentage of the teacher trainees who didn’t succeed in the certification exams could be an indicator of “negative (poor) performance” for all the training participants (Negative/ Poor “Performance” rate) and for that reason, it was also examined per teacher specialty and training model.

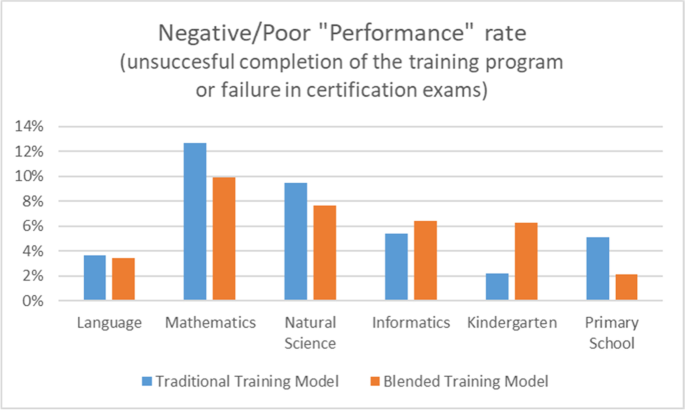

The percentage of the teacher trainees who either didn’t successfully complete the training program or didn’t succeed in the certification exams (i.e. they got a final grade < 60 in scale 0–100), per teacher specialty and training model (parameter α 5 in Fig. 9 ), is presented in the following Table 7 and Fig. 16 .

Negative "Performance" rate (unsuccessful completion of the training or failure in certification exams)

This indicator, corresponding to “negative/poor” performances of the B-Level ICT Teacher Training, is generally displayed with low values. In traditional training model the values range from 2,2% for Kindergarten teachers to 12,6% for Mathematics Teachers. In blended training model these values appear a little lower, ranging from 2,1% for Primary School Teachers to 9,9% for Mathematics Teachers, indicating in general, a marginally better performance for the blended learning model trainees. However, the higher values of this indicator for Informatics and Kindergarten teachers (a difference of 1,1 and 4,1 percentage units, respectively), present in contrary a better performance of the traditional training model in these cases.

3.6 Overall teacher trainees’ “performance” (regardless of teacher specialty)

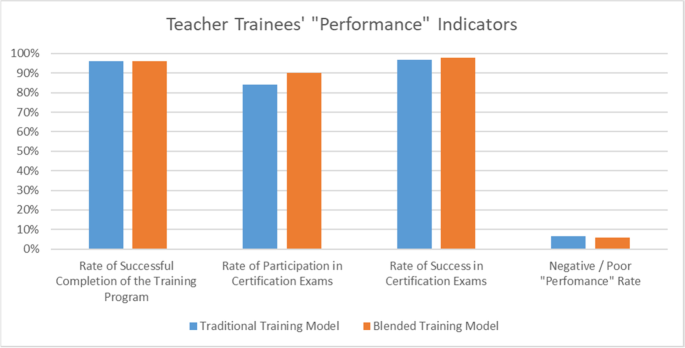

In addition, the above mentioned “performance” indicators were examined for all the teachers who participated in traditional training programs or in blended training program, as a total, i.e. regardless of teacher specialty.

In the following Table 8 and Fig. 17 there are presented for all the B-level ICT teacher trainees, regardless their teacher specialty (per training model): a) the percentage of the trainees who successfully completed the training program (parameter α 1 in Fig. 9 ), b) the percentage of the trainees who sat the certification exams (parameter α 2 in Fig. 9 ), c) the percentage of the trainees who succeeded in the certification exams (parameter α 3 in Fig. 9 ), as well as d) the indicator of negative/poor performance corresponding to the sum of the percentages of the trainees who didn’t complete successfully the training program and them who didn’t succeed in the certification exams (parameter α 5 in Fig. 9 ).

Teacher trainees' "Performance" indicators

In the above data a slightly better performance appears among trainees of the blended learning model, as we can see 5,91 units overstepping at the percentage of the trainees who sat the exams and 0,96 units overstepping at the percentage of the trainees who succeeded in the certification exams, as well as 0,43 percentage units decrease to the negative/poor performance indicator. A minor increase of 0,14 units to the percentage of the traditional model trainees who successfully completed the training program, is also noted.

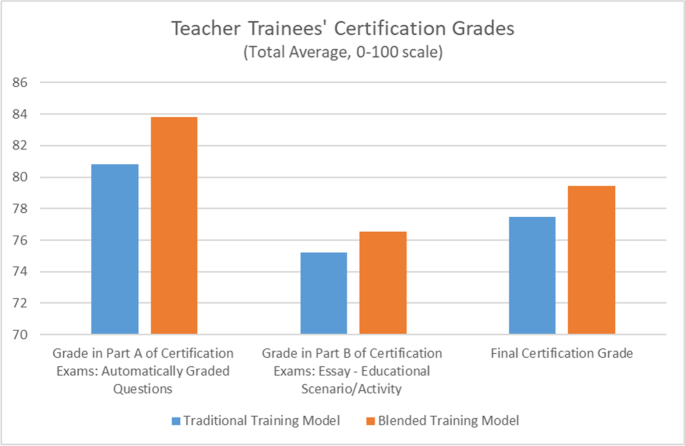

Finally, the grades achieved by the trainees in the certification exams, were studied overall, regardless the teacher specialties.

In the following Table 9 and Fig. 18 , for all the B-level ICT teacher trainees, regardless of their teacher specialty (per training model), the following data are presented (in reference to parameter α 4 in Fig. 9 ): a) the average of all trainees’ grades corresponding to the first part (automatically graded questions) of the certification exams , b) the average of all trainees’ grades corresponding to the second part (free-writing theme/ educational scenario – activity utilizing ICT) of the certification exams and c) the average of all trainees’ final certification grades (deriving from the grades of the above two parts).

Teacher trainees' certification grades

Concerning the final certification grade, according to the above data, higher grades for the trainees of blended learning programs are clearly observed (by 2 units, in 0–100 scale). This difference inheres obviously in the grades of the first and the second part of the exam, where higher grades, by 3 and 1,3 percentage units respectively, appear. This better performance for the trainees of blended learning programs, especially in the second part of the exam (essay/ educational scenario—activity utilizing ICT), could result from the increased involvement of the participants with the training subjects, carrying out relevant projects and activities in the framework of the asynchronous part of the blended training program.

4 Discussion—conclusions

In this paper we attempted to compare “traditional” teacher training (taking place entirely through face to face sessions) with teacher training through blended learning approach/ model (including both face to face and synchronous distance sessions accompanied by asynchronous activities), as it was designed and implemented in the in-service teacher training for the utilization and application of digital technologies in the teaching practice (B-Level ICT Teacher Training) that has been taking place in Greece for more than ten years. In response to a need for further research towards this direction (Garrison & Kanuka, 2004 ; Watson, 2008 ), this comparison refers to assessing the effectiveness of the two models/ approaches, as it derives from teacher trainees’ performances, especially in the framework of the certification procedure regarding the knowledge and skills acquired, through exams that follow the training.

In the present research we haven’t dealt with the various elements of the two training models, but we based their comparison on the final results, focusing on the learning outcomes of the trainees, as they derive from the final certification process (nationwide-independent digital exams).

Research findings show better performances of a small or marginal scale for the teachers who participated in blended leaning teacher training programs compared to those who participated in traditional teacher training programs, in consistency with relevant research that reports blended learning as offering a slight advantage regarding overall student success and withdrawal rates (Dziuban et al., 2018 ; Means et al., 2010 ; Youngers, 2014 ).

Furthermore, some other aspects could be considered as factors that have influenced trainees’ improved performance in the blended training model, such as: a) the fact that the training activities in the technology enhanced blended training model were designed in a way which allowed a satisfying continuation and a strong link between face to face training sessions and synchronous distance training sessions with asynchronous activities, thus a strong integration between the two (Casanova & Moreira, 2017 ; Dagdilelis, 2014 ; Komis et al., 2014 ), b) the flexibility of the technology enhanced blended training model that enabled the trainees to experience a more personalized learning experience, which strengthened their confidence in sitting the certification exams (Casanova & Moreira, 2017 ; Dagdilelis, 2014 ; Komis et al., 2014 ), as well as c) the impact that technology had on the learning process, in the current blended training program (Casanova & Moreira, 2017 ).

Looking closer, B-Level ICT Teacher Training is a popular and successful training action for the Greek educational community and thus, both the percentage of trainees that successfully complete the program and the percentage of trainees who succeed in the certification exams, was always very high as long as the traditional training model was followed (96% and 97%, respectively). So, these too high percentage values don’t allow any major upward differentiation for the case of the blended training model. However, it seems that there is a minor lead at the blended training model percentage values referring to the trainees’ success rate in the certification exams (by around one percentage unit), as well as to the respective certification grades (an average of 2 units in 0–100 scale at the final certification grades and 1–3 units at the grades of part A and B of the exam). In addition, there is a difference at the percentage of the trainees who sat the exams (approximately 6 percentage units), which could mean that the participants of blended training programs feel better prepared for the exams, because of their greater involvement with the training subjects through carrying out projects and educational activities (e.g. educational scenarios-activities utilizing ICT etc.), especially in the framework of the asynchronous sessions of the program.

Studying the various teacher specialties separately, it’s worth noting some better “performance” values in the case of the blended training model a) for the Mathematics teachers, both the percentage of the trainees who sat the exams, which appears about 8 units higher than the one in the case of traditional training model and the percentage of the trainees who succeeded in the certification exams, which appears about 4,65 units higher, with higher average grades as well (by 2,12 units) and b) for the Natural Science teachers, the certification grades which appear about 3 units higher (bigger difference of all specialties). In addition, the case of Informatics teachers seems interesting, as in essence there is no difference at the trainees’ “performance” between the two models, while a few more blended learning model trainees drop out and do not successfully complete the training program (a difference in the order of 1%). Similar picture with the one of the Informatics teachers, with a little bigger difference at the percentage of the blended learning model trainees who do not complete the training program, appears for the Kindergarten teachers. Besides, it’s worth also noting that the success rate in the certification exams for the Kindergarten teachers is extremely high (approximately 100%) and remains the same in both models. This is in line with other research findings on the perceptions and practices for the utilization of ICT addressing Kindergarten teachers who have attended B-Level ICT teacher training, where their satisfaction from the training and their positive attitude for integrating ICT in their everyday teaching practice, are highlighted (Komis et al., 2015 ). Finally, it is impressive that in the case of the Primary School teachers, the percentage of blended learning model trainees who sat the exam are more than 10 units higher than the one of the traditional model trainees. This difference, similarly to the case of Kindergarten teachers, is not reflected in the success rate of the certification exam, which remains at the same high level (approximately 98%).

Consequently, the research findings lead to the basic conclusion that the application of the blended learning model in a teacher training action regarding the utilization of digital technologies in the teaching practice, for instance the combination of face to face training sessions and synchronous distance training sessions with asynchronous activities (supported by digital technologies), presents greater effectiveness of a small or marginal scale (depending on the teacher specialty) than the traditional training model which entirely consists of face to face sessions.

As described in the summary of references in previous related research studies included in the introduction section of this paper (Section 1 ), the results and the basic conclusion of our research in general is in line with related published findings and conclusions (Dziuban et al., 2018 ; Means et al., 2010 ; Youngers, 2014 ). However, recently, especially in the era of pandemic covid-19, where on line learning or blended learning were implemented in a rough way even in audiencies where such a method is not considered as appropriate, there are some findings stating that face to face learning is preferable and possibly more efficient for the learners (Atwa et al., 2022 ; Nasution et al., 2021 ).

Furhermore, as this research doesn’t deal with the various elements of the two training models, but is limited to the comparison of the trainees’ performance mainly based on the final certification process (through nationwide-independent digital exams), other issues concerning elaboration of qualitative data remain open. These issues could be considered as limitations of our study or subject for further research in the future and include the perceptions of the teacher trainees and the teacher trainers on the application of the training models, the comparison of an entirely distance training model with the blended one including additional face to face activities, the contribution of the particular elements and the characteristics of the models (i.e. the specific design of each model) in the effectiveness of the training program for the utilization of ICT in the teaching practice etc.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Training and Certification, Computer Technology Institute & Press – “Diophantus”, Patras, Greece

Charalampos Zagouras, Demetra Egarchou, Panayiotis Skiniotis & Maria Fountana

Department of Mathematics, University of Patras, Patras, Greece

Charalampos Zagouras

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Demetra Egarchou .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest, additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Zagouras, C., Egarchou, D., Skiniotis, P. et al. Face to face or blended learning? A case study: Teacher training in the pedagogical use of ICT. Educ Inf Technol 27 , 12939–12967 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11144-y

Download citation

Received : 20 May 2021

Accepted : 26 May 2022

Published : 17 June 2022

Issue Date : November 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11144-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Blended Learning

- Face to Face Learning

- Teacher Training

- Teacher Professional Development

- ICT in education

- B-Level ICT Teacher Training

- Certification of Teacher ICT skills

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Microbiol Biol Educ

- v.16(1); 2015 May