An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci

- v.366(1567); 2011 Apr 12

Language evolution and human history: what a difference a date makes

Historical inference is at its most powerful when independent lines of evidence can be integrated into a coherent account. Dating linguistic and cultural lineages can potentially play a vital role in the integration of evidence from linguistics, anthropology, archaeology and genetics. Unfortunately, although the comparative method in historical linguistics can provide a relative chronology, it cannot provide absolute date estimates and an alternative approach, called glottochronology, is fundamentally flawed. In this paper we outline how computational phylogenetic methods can reliably estimate language divergence dates and thus help resolve long-standing debates about human prehistory ranging from the origin of the Indo-European language family to the peopling of the Pacific.

1. Introduction

Historical inference is hard. Trying to work out what happened 600 years ago is difficult enough. Trying to make inferences about events 6000 years ago may seem close to impossible. As W. S. Holt observed, the study of human history is ‘a damn dim candle over a damn dark abyss’. And yet evolutionary biologists routinely make inferences about events millions of years in the past. Our ability to do this was revolutionized by Zuckerkandl & Pauling's [ 1 ] insight that molecules are ‘documents of evolutionary history’. Molecular sequences have inscribed in their structure a record of their past. Similarities generally reflect common ancestry. Today, computational phylogenetic methods are routinely used to make inferences about evolutionary relationships and processes from these sequences. These inferences are more powerful when independent lines of evidence, such as information from studies of morphology, geology and palaeontology, are brought to bear on a common problem.

Languages, like genes, are also ‘documents of history’. A vast amount of information about our past is inscribed in the content and structure of the approximately 7000 languages that are spoken today [ 2 ]. Historical linguists have developed a careful set of procedures termed the ‘comparative method’ to infer ancestral states and construct language family trees [ 3 , 4 ]. Ideally, as Kirch & Green [ 5 ] and Renfrew [ 6 ] have argued, independent evidence from anthropology, archaeology and human genetics are used to ‘triangulate’ inferences about human prehistory and cultural evolution. From anthropology comes an understanding of social organization, from archaeology comes an absolute chronology of changes in material culture, and from genetic studies we get information about the sequence of population movements and the extent of admixture. Traditionally, historical linguistics has contributed inferences about ancestral vocabulary and a relative cultural chronology to this synthesis.

While this ‘new synthesis’ [ 7 ] is a worthy aim, it is often very difficult to link the different lines of evidence together. Archaeological remains do not speak. Genes and languages can have different histories or appear spuriously congruent. The one thing that is critically important to successfully triangulating the different lines of evidence together is timing. If archaeological, genetic and linguistic lines of evidence show similar absolute dates for a common sequence of events, then our confidence that a common process is involved would be hugely increased, and the ‘damn dark abyss’ of human history greatly illuminated. Sadly, the absence of appropriate calibration points and systematic violations of the molecular clock mean that there are large sources of error associated with most genetic dates for human population history [ 8 ]. Sadder still, although the comparative method in linguistics can provide a relative chronology, it cannot provide absolute date estimates. In the words of April MacMahon & Rob MacMahon [ 9 ] ‘linguists don't do dates’. We are not so pessimistic. In what follows we will outline why dating linguistic lineages is a difficult, but not impossible, task.

2. Dating difficulties

A quick glance at an Old English text, such as the epic poem Beowulf , should be enough to convince anyone of two facts. Languages evolve and they evolve rapidly. New words arise and others are replaced. Sounds change, grammar morphs and speech communities split into dialects and then distinct languages. Given this linguistic divergence over time, one plausible intuition is that it might be possible to use some measure of this divergence to estimate the age of linguistic lineages in much the same way that biologists use the divergence of molecular sequences to date biological lineages. ‘Glottochronology’ attempts to do just that. In the early 1950s, a full decade before Zuckerkandl & Pauling introduced the idea of a molecular clock to biology, Swadesh [ 10 , 11 ] developed an approach to historical linguistics termed lexicostatistics and its derivative ‘glottochronology’. This approach used lexical data to determine language relationships and to estimate absolute divergence times. Lexicostatistical methods infer language trees on the basis of the percentage of shared cognates between languages—the more similar the languages, the more closely they are related. Cognates are words in different languages that have a common ancestor. In biological terminology they are homologous. Words are judged to be cognate if they have a pattern of systematic sound correspondences and similar meanings. Glottochronology is an extension of lexicostatistics that estimates language divergence times under the assumption of a ‘glottoclock’, or constant rate of language change. The following formulae can be used to relate language similarity to time along an exponential decay curve:

where t is time depth in millennia, C is the percentage of cognates shared and r is the ‘universal’ constant or rate of retention (the expected proportion of cognates remaining after 1000 years of separation). Usually analyses are restricted to the Swadesh word list—a collection of 100–200 basic meanings that are thought to be relatively culturally universal, stable and resistant to borrowing. These include kinship terms (e.g. mother, father), terms for body parts (e.g. hand, mouth, hair), numerals and basic verbs (e.g. to drink, to sleep, to burn). For the Swadesh 200-word list, the retention rate ( r ) was estimated from cases where the divergence date between languages was known from historical records. This rate was found to be approximately 81 per cent.

Unfortunately, this apparently simple and elegant solution to the important problem of dating linguistic lineages encountered some major obstacles [ 12 , 13 ], and thus most historical linguists now view glottochronological calculations with considerable scepticism. The most fundamental obstacle encountered by glottochronology is the fact that languages, just like genes, often do not evolve at a constant rate. In their classic critique of glottochronology, Bergsland & Vogt [ 12 ] compared present-day languages with their archaic forms. They found considerable evidence of rate variation between languages. For example, Icelandic and Norwegian were compared with their common ancestor, Old Norse, spoken roughly 1000 years ago. Norwegian has retained 81 per cent of the vocabulary of Old Norse, correctly suggesting an age of approximately 1000 years. However, Icelandic has retained over 95 per cent of the Old Norse vocabulary, falsely suggesting that Icelandic split from Old Norse less than 200 years ago. This is not an isolated example. In a survey of Malayo-Polynesian languages, Blust [ 13 ] documented variations in the retention of basic vocabulary driven by factors such as language contact and large changes in population size that ranged from 5 to 50 per cent in the approximately 4000 years from Proto Malayo-Polynesian to the present. Blust argued that these huge differences in retention rates inevitably distorted both the trees obtained by lexicostatistics and the glottochronological dates.

It is ironic that over the past half-century, computational methods in historical linguistics have fallen out of favour while in evolutionary biology computational methods have blossomed. Rather than giving up and saying, ‘we don't do dates’, computational biologists have developed methods that can accurately estimate phylogenetic trees and divergence dates even when there is considerable lineage-specific rate heterogeneity. Evolutionary biologists today typically use likelihood and Bayesian methods to explicitly model all the substitution events, instead of building trees from pairwise distance matrices [ 14 , 15 ]. The development of these more powerful computational methods has been facilitated by both a spectacular increase in the availability of molecular sequences and dramatic increases in computational power in the past 20 years [ 16 ]. The use of all the sequence information and more complex and realistic models of the substitution process mean that likelihood and Bayesian methods outperform the simple clustering methods, especially when rates of molecular change are not constant [ 17 ]. In addition to developing methods to build more accurate trees, evolutionary biologists have recently developed methods to obtain more accurate date estimates, even when there are departures from the assumption of a strict molecular clock.

One popular approach pioneered by Sanderson [ 18 , 19 ] involves two steps. First, a set of phylogenetic trees and their associated branch lengths are estimated. In Bayesian phylogenetic analyses of molecular evolution, the branch lengths are proportional to the number of substitutions along a branch given the data, the substitution model and the priors. The second step involves converting the relative branch lengths into time. Calibration points are required to do this. These are places where nodes (branching points) on the trees can be constrained to a known date range. These known node ages are then combined with the branch-length information to estimate rates of evolution across each tree. A penalized-likelihood model is used to allow rates to vary across the tree while incorporating a ‘roughness penalty’. The more the rates vary from branch-to-branch, the greater the cost (see [ 18 , 19 ] for more detail). The algorithm allows an optimal value of the roughness penalty to be selected. In this way, the combination of calibrations, branch-length estimates and the rate-smoothing algorithm enables dates to be estimated without assuming a strict clock. An alternative ‘relaxed phylogenetics’ approach, in which the tree and the dates are simultaneously estimated, has recently been developed by Drummond et al . [ 20 ]. In ‘relaxed phylogenetics’, the assumption of a strict clock can be eased by modelling the rate variation using lognormal or exponential distributions (see [ 20 ] for more detail). In the sections that follow, we will explore how these computational phylogenetic methods can be used to illuminate the linguistic and cultural history of people both in Europe and in the Pacific.

3. The origin of the indo-european languages

The origin of the Indo-European languages has recently been described as ‘one of the most intensively studied, yet still most recalcitrant problems of historical linguistics’ [ 21 , p. 601]. Despite over 200 years of scrutiny, scholars have been unable to locate the origin of Indo-European definitively in time or place. Theories have been put forward advocating ages ranging from 4000 to 23 000 years, with hypothesized homelands including Central Europe, the Balkans and even India. Mallory [ 22 ] acknowledges 14 distinct homeland hypotheses since 1960 alone. He rather colourfully remarks that, ‘the quest for the origins of the Indo-Europeans has all the fascination of an electric light in the open air on a summer night: it tends to attract every species of scholar or would-be savant who can take pen to hand’ [ 22 , p. 143].

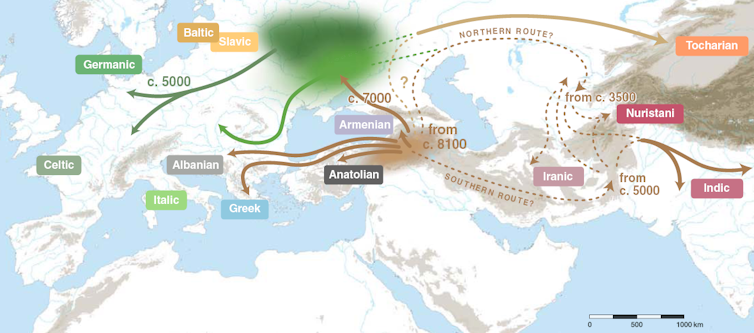

Of all the diverse theories about the origin of Indo-Europeans there are currently two that receive the most attention. The first, put forward by Gimbutas [ 23 , 24 ] on the basis of linguistic and archaeological evidence, links Proto-Indo-European (the hypothesized ancestral Indo-European tongue) with the Kurgan culture of southern Russia and the Ukraine. The Kurgans were a group of semi-nomadic, pastoralist, warrior-horsemen who expanded from their homeland in the Pontic steppes during the fifth and sixth millennia BP, conquering Danubian Europe, Central Asia and India, and later the Balkans and Anatolia. This expansion is thought to roughly match the accepted ancestral range of Indo-European [ 25 ]. As well as the apparent geographical congruence between Kurgan and Indo-European territories, there is linguistic evidence for an association between the two cultures. Words for supposed Kurgan technological innovations are consistent across widely divergent Indo-European sub-families. These include terms for ‘wheel’ (*rotho-, *k W (e)k W l-o-), ‘axle’ (*aks-lo-), ‘yoke’ (*jug-o-), ‘horse’ (*ekwo-) and ‘to go, transport in a vehicle’ (*wegh- [ 14 , 15 ]): it is argued that these words and associated technologies must have been present in the Proto-Indo-European culture and that they were likely to have been Kurgan in origin. Hence, the argument goes, the Indo-European language family is no older than 5000–6000 BP. Mallory [ 22 ] argues for a similar time and place of Indo-European origin—a region around the Black Sea about 5000–6000 BP (although he and many linguists are more cautious and refrain from identifying Proto-Indo-European with a specific culture such as the Kurgans).

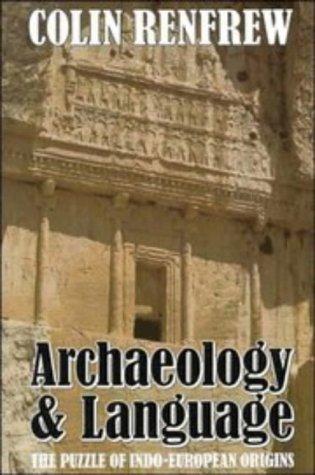

The second theory, proposed by the archaeologist Renfrew [ 26 ], holds that Indo-European languages spread, not with marauding horsemen, but with the expansion of agriculture from Anatolia between 8000 and 9500 years ago. Radiocarbon analysis of the earliest Neolithic sites across Europe provides a fairly detailed chronology of agricultural dispersal. This archaeological evidence indicates that agriculture spread from Anatolia, arriving in Greece at some time during the ninth millennium BP and reaching as far as the British Isles by 5500 BP [ 27 ]. Renfrew maintains that the linguistic argument for the Kurgan theory is based only on limited evidence for a few enigmatic Proto-Indo-European word forms. He points out that parallel semantic shifts or wide-spread borrowing can produce similar word forms across different languages without requiring that an ancestral term was present in the proto-language. Renfrew also challenges the idea that Kurgan social structure and technology was sufficiently advanced to allow them to conquer whole continents in a time when even small cities did not exist. Far more credible, he argues, is that Proto-Indo-European spread with the spread of agriculture.

The debate about Indo-European origins thus centres on archaeological evidence for two population expansions, both implying very different timescales—the Kurgan theory with a date of 5000–6000 BP, and the Anatolian theory with a date of 8000–9500 BP. One way of potentially resolving the debate is to look outside the archaeological record for independent evidence, which allows us to test between these two time depths. Does linguistics hold the key? Well, not if linguists do not do dates. However, if we could reliably date the origin of the Indo-European languages, then it would make a huge difference to this 200 year old debate.

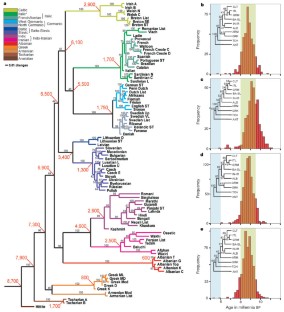

We set about this rather daunting task by building on what Darwin dubbed the ‘curious parallels’ between biological and linguistic evolution (see [ 28 ] for an analysis of the history of these parallels). If languages, like biological species, are also ‘documents of history’, then perhaps they could be analysed using the same computational evolutionary methods. Maybe the solutions biologists have found to violations of the molecular clock could be used to overcome problems with glottochronology. It requires a large amount of data to estimate tree topology and branch lengths accurately. Our data were taken from the Dyen et al . [ 29 ] Indo-European lexical database, which contains expert cognacy judgements for 200 Swadesh list terms in 95 languages. Dyen et al . [ 29 ] identified 11 languages as less reliable and hence they were not included in the analysis presented here. We added three extinct languages (Hittite, Tocharian A and Tocharian B) to the database in an attempt to improve the resolution of basal relationships in the inferred phylogeny. For each meaning in the database, languages were grouped into cognate sets. By restricting analyses to basic vocabulary, such as the Swadesh word list, the influence of borrowing can be minimized. For example, although English is a Germanic language, it has borrowed around 60 per cent of its total lexicon from French and Latin. However, only about 6 per cent of English entries in the Swadesh 200-word list are clear Romance language borrowings [ 30 ]. Known borrowings were not coded as cognate in the Dyen et al . database. The cognate sets were binary-coded—that is in a matrix a column was set up for each cognate set in which the presence of a cognate for a language was denoted with a ‘1’ and an absence with a ‘0’. This produced a matrix of 2449 cognate sets for 87 languages. This matrix was analysed in the Bayesian phylogenetics package MRBAYES [ 31 ] using a simple model that assumed equal rates of cognate gains and losses to produce a sample of trees from the posterior probability distribution of the trees (the set of trees found in the Markov chain Monte Carlo runs post ‘burn in’ given the data, model of cognate evolution and priors on variables such as the parameters of the model and branch lengths). In order to infer divergence dates, we needed to calibrate the rates of evolution by constraining the age of nodes on each tree in accordance with historically attested dates. For example, the Romance languages probably began to diverge prior to the fall of the Roman Empire. The last Roman troops were withdrawn south of the Danube in AD 270. Thus, we constrained the age of the node corresponding to the most recent common ancestor of the Romance languages to AD 150–300. We constrained the age of 14 nodes on the trees. The penalized rate-smoothing algorithm was then used to covert the set of trees into dated ‘chronotrees’ (see [ 32 ] for more details on the methods and calibrations used).

Our initial analyses provided strong support for the time-depth predictions of Anatolian hypothesis. The date estimates for the age of Proto Indo-European centred around 8700 BP ( figure 1 ). None of our sample of chronotrees was in the 5000–6000 years BP age range predicted by the Kurgan hypothesis. A key part of any Bayesian phylogenetic analysis is an assessment of the robustness of the inferences. We did our best to try and ‘break’ the initial result. We examined the impact of altering the branch length priors in our analysis, of throwing out cognates Dyen et al . had dubbed ‘dubious’, of removing some calibrations, of trimming the data to the most stable items and rerooting the trees. None of these changes substantially altered our date estimates of the age of Proto Indo-European. If anything, they often tended to make the distribution older, not younger [ 32 , 33 ].

A dated phylogenetic tree of 87 Indo-European languages. The tree is a consensus tree derived from the posterior samples of trees in the Bayesian analyses reported by Gray & Atkinson [ 32 ]. The values on the branches are the posterior probability of that clade. The root age of the tree is in the age range predicted by the Anatolian hypothesis. This figure also shows an interesting point that we had noted, but not emphasized, in our initial paper—while the root of the tree goes back around 8700 years, much of the diversification of the major Indo-European subgroups happened around 6000–7000 BP. This means that both the Anatolian and the Kurgan hypotheses could be simultaneously true. There was an initial movement out of Anatolia 8700 years ago and then a major radiation 6000–7000 years ago from southern Russia and the Ukraine. It also means that the intuition shared by many linguists that the Indo-European language family is about 6000 years old could be correct for the vast majority of Indo-European languages, just not the deeper subgroups.

The response to our paper was rather mixed. While some linguists were positive, many simply failed to understand that the methods we had used were substantially different from traditional glottochronology [ 34 ]. A small number of critics raised concerns about the data we had used, the binary coding of the cognate sets, the simple model of cognate evolution and the impact of undetected borrowing. Let us deal with each of these potentially valid concerns in turn.

First, although the cognate coding in the Dyen et al . dataset was conducted by experienced linguists, it may well contain some errors [ 35 ]. While these errors are likely to be a relatively small proportion of the total data, it is possible that they might have biased our date estimates. It is also possible that the simple stochastic model of cognate evolution we used led to inaccurate results because the model assumed that the rates of cognate gain and loss were equal—an assumption that is not realistic. It is rare for very similar words with similar meanings to be independently invented [ 36 ]. A more realistic model would thus allow cognates to be gained only once but lost multiple times. This mirrors the principle in evolution biology known as Dollo's Law, which suggests that once complex structures are lost they are unlikely to be evolved again. While simple models do not necessarily produce inaccurate results [ 33 ], in Bayesian analyses it is important to assess the robustness of the conclusions to any model misspecification. For this reason, Geoff Nicholls and R.G. developed a stochastic ‘Dollo’ model of cognate evolution [ 37 ]. We used this model to analyse an independent dataset [ 38 ], predominantly comprising ancient Indo-European languages. These analyses of a separate dataset with an entirely different model produced almost identical results to our initial analyses of the Dyen data [ 37 , 39 ]. Not content with this proof of the robustness of our analyses, we recently re-analysed the Ringe et al . data using the lognormal relaxed clock and the stochastic Dollo model implemented in the package BEAST [ 40 ]. Yet again the date estimates for Proto Indo-European fell into the age range predicted by the Anatolian hypothesis ( figure 2 ). Re-analysing the Dyen et al . data with the lognormal relaxed clock and the stochastic Dollo model also produced results that are highly congruent with the initial results of Gray & Atkinson.

Distributions of the age of Proto Indo-European estimated from the data of Ringe et al . [ 38 ]. Four different analyses were conducted using the program BEAST. Two analyses assumed equal rates of cognate gain and loss—one with a strict clock (light green) and one with a lognormal relaxed clock (orange). The other two analyses assumed that cognates could only be gained once but lost multiple times (stochastic Dollo). Again one implemented a strict clock (purple) and one used a lognormal relaxed clock (light blue). The date estimates obtained in all four analyses were consistent with the Anatolian hypothesis.

If either problems with the data or the model of cognate evolution appear to have biased our results, what about the binary coding of the cognate sets? Evans et al . [ 41 ] claim that our coding is ‘patently inappropriate’ because it assumes independence between the cognate sets. Our sets are clearly not independent because one form will often replace another within a meaning class (although some polymorphism does occur). On the surface this is a plausible argument. However, Evans et al . provide no argument for why the lack of independence will bias the time-depth estimates to be too old (rather than merely underestimating the variance). On the contrary, we have simulated totally dependent cognate evolution and shown that it does not bias the date estimates [ 39 ]. Others have found empirically that binary and multi-state codings of the same lexical data produce virtually identical results [ 42 ]. Furthermore, Pagel & Mead [ 43 ] demonstrated that, at least when the number of states is constant, binary and multi-state-coded data produce trees that differ only in length by a constant proportionality. In other words, the binary and multi-state trees are just scaled versions of one another and therefore the date estimates will not be biased. This result is also likely to hold when the number of states varies (M. Pagel 2010, personal communication).

Removing all the borrowed cognates from a dataset can be difficult. While irregular sound correspondences might make some easy to identify, others may be difficult to detect. Garrett [ 44 ] argues that borrowing of lexical terms, or advergence, within the major Indo-European subgroups could have distorted our results. To assess this possibility, we examined the impact of different borrowing scenarios by simulating cognate evolution [ 45 ]. The results showed that tree topologies constructed with Bayesian phylogenetic methods were robust to realistic levels of borrowing in basic vocabulary (0–15%). Inferences about divergence dates were slightly less robust and showed a tendency to underestimate dates ( figure 3 ). The effect is pronounced only when there is global rather than local borrowing on the tree. This is the least likely scenario we simulated and suggests that if our estimates for the age of Indo-European are biased by undetected borrowing at all, they are likely to be too young, rather than too old.

Mean reconstructed root time for each simulation under three borrowing scenarios: (i) local borrowing within 1000 years, (ii) local borrowing within 3000 years, and (iii) global borrowing. Two different tree topologies were used in the simulations: ( a ) tree 1 and ( b ) tree 2. The dotted line marks the true root age and the cross marks the root age under the no borrowing scenario.

While all these re-analyses and simulation studies demonstrate the reliability of our estimates for the age of Indo-European, perhaps the most compelling refutation of our critics' arguments comes from the model validation analyses we recently conducted. Nicholls & Gray [ 46 ] sequentially removed calibration points from some analyses conducted using the stochastic Dollo model implemented in the program T raitlab . We then re-ran the analysis and examined the date estimates of these nodes. If model misspecification meant that our age estimates were systematically too old, then the estimated ages should be systematically older than the known ages of the nodes in the trees that we removed the calibrations from. This was not the case. Overwhelmingly, the estimates were congruent with the known node ages.

4. The austronesian expansion

The Austronesian settlement of the vast Pacific Ocean has been a topic of enduring fascination. It is the greatest human migrations in terms of the distance covered and the most recent. There are two major hypotheses for the Austronesian settlement of the Pacific. The first hypothesis is the ‘pulse–pause’ scenario [ 5 , 47 – 49 ]. This scenario argues that the ancestral Austronesian society developed in Taiwan around 5500 years ago. Around 4000–4500 years ago, there was a rapid expansion pulse across the Bashii channel into the Philippines, into Island Southeast Asia, along the coast of New Guinea, reaching Near Oceania by around 3000–3300 years ago [ 50 ]. As the Austronesians travelled this route, they integrated with the existing populations in the area (particularly in New Guinea), and innovated new technologies. After reaching Western Polynesia (Fiji, Tonga and Samoa) approximately 3000 years ago, the Austronesian expansion paused for around 1000–1500 years, before a second rapid expansion pulse spread Polynesian languages as far afield as New Zealand, Hawaii and Rapanui.

The second hypothesis of Pacific settlement—the ‘slow boat’ scenario—argues for a much older origin in Island Southeast Asia [ 51 – 53 ]. According to this scenario, date estimates from mitochondrial DNA lineages suggest that Austronesian society developed around 13 000–17 000 years ago in an extensive network of sociocultural exchange in the Wallacean region around Sulawesi and the Moluccas. Proponents of this scenario propose that the submerging of the Sunda shelf at the end of the last ice-age triggered the Austronesian expansion [ 53 ]. This ‘flood’ led to a two-pronged movement of people, north into the Philippines and Taiwan, and east into the Pacific. Significantly, they argue that this movement of people was paralleled by the spread of Austronesian languages (i.e. Austronesian genes and languages have a common history). ‘The Austronesian languages originated within island Southeast Asia during the Pleistocene era and spread through Melanesia and into the remote Pacific within the past 6000 years’ [ 54 , p. 1236].

These two scenarios of Pacific settlement make quite different predictions about the origin, age and sequence of the Austronesian expansion. The pulse–pause model predicts that a phylogenetic tree of Austronesian languages should be rooted in Taiwan and show a chained topology that mirrors the generally eastwards spread of the languages. According to this model, the Austronesian language family should be about 5500 years old. Most boldly, the model predicts that there should be a long pause between the Taiwanese languages and the rest of Austronesian, followed by a rapid diversification pulse and then another long pause in Polynesia. In contrast, the slow boat model predicts that any language family tree should be rooted in the Wallacean region, be between 13 000 and 17 000 years old and have a two-pronged topology with one branch going north to the Philippines and Taiwan and the other eastwards along the New Guinea coast out into Oceania.

Clearly, a robustly dated language phylogeny would be an ideal way to test between the pulse–pause and slow boat models of Austronesian expansion. However, the construction of an accurate, dated language phylogeny for the Austronesian languages provides numerous challenges for any would be language phylogenticist. First, the rapid expansion of the Austronesian family means that it is likely to be difficult to resolve the fine branching structure of the Austronesian language tree as there is little time for the internal branches on the tree to develop numerous shared innovations [ 55 ]. Second, as these languages moved across the Pacific, they encountered new environments and the consequent need for new terminology may have increased the rates of language replacement. This acceleration in rates is likely to be exacerbated by the effects of language contact—particularly within Near Oceania [ 56 ]. Additionally, many Austronesian languages have small speech communities, which are also likely to speed up the rates of language evolution [ 57 ]. The effects of these factors can be seen in the 10-fold variation in cognate retention rates in Austronesian languages [ 13 ].

Successful phylogenetic analyses require data with sufficient historical information to resolve the aspects of the phylogeny we are interested in. Over the past 7 years we have compiled a large web-accessible database of cognate-coded basic vocabulary for over 700 Austronesian languages [ 16 ]. This database was initially based on 230 language word lists we obtained from Bob Blust, but by placing it on the web we have been able to grow and refine the database and cognate coding with the generous assistance of linguists around the globe. In the 400-language dataset reported in Gray et al . [ 49 ], the 210 items of basic vocabulary produced a matrix of 34 440 binary-coded cognate sets.

The first prediction we tested with the Bayesian phylogenetic analyses of this data concerned the origin and sequence of Austronesian expansion. Under the pulse–pause scenario, the Austronesians originated in Taiwan and had a single-chained expansion down through the Philippines, through Wallacea, along New Guinea into Near Oceania and Polynesia. In contrast, the slow boat scenario posits a two-pronged expansion from a Wallacean origin. Our set of trees placed the root of trees in Taiwan, and followed it with the sequence predicted by the pulse–pause scenario ( figure 4 ).

Map and language family tree showing the settlement of the Pacific by Austronesian-speaking peoples. The map shows the settlement sequence and location of expansion pulses and settlement pauses. The tree is rooted with some outgroup languages (Buyang and Old Chinese) at its base. It shows an Austronesian origin in Taiwan around 5200 years ago, followed by a settlement pause (pause 1) between 5200 and 4000 years ago. After this pause, a rapid expansion pulse (pulse 1) led to the settlement of Island Southeast Asia, New Guinea and Near Oceania in less than 1000 years. A second pause (pause 2) occurs after the initial settlement of Polynesia. This pause is followed by two pulses further into Polynesia and Micronesia around 1400 years ago (pulses 2 and 4). A third expansion pulse occurred around 3000–2500 years ago in the Philippines.

The second key prediction of the two Pacific settlement scenarios concerned the age of the expansion. To test this prediction, we estimated the age at the root of our trees. To begin with, we calibrated 10 nodes on the trees with archaeological date estimates and known settlement times. For example, speakers of the Chamic language subgroup were described in Chinese records around 1800 years ago and probably entered Vietnam around 2600 years ago [ 58 ]. We can therefore calibrate the appearance of the Chamic node on our tree to between 2000 and 3000 years ago. A second calibration, based on archaeological evidence, constrains the age of the hypothesized ancestral language spoken by all the languages of Near Oceania, Proto Oceanic. The speakers of Proto Oceanic arrived in Oceania around 3000–3300 years ago and brought with them distinctively Austronesian societal organization and cultural artefacts. These artefacts have been identified and dated archaeologically, and include the Lapita adze/axe kits, housing types, fishing equipment (such as the one-piece rotating fishhooks, and one-piece trolling lure), as well as common food plants and domesticated animals from Southeast Asia.

To estimate the age of the Austronesian family without assuming a strict glottoclock, we used the penalized likelihood approach outlined above. The results unequivocally supported the younger age of the pulse–pause scenario, with an origin of the Austronesian family around 5200 years ago ( figure 5 a ). Like the Indo-European analyses, the results were robust to assumptions about specific calibration points. For example, when we removed all the calibration points, apart from the Proto Oceanic constraint and the three ancient languages [ 59 ], the estimated age of Proto Austronesian was virtually identical ( figure 5 b ).

Histograms of the Bayesian phylogenetic estimates for the age of Proto Austronesian. ( a ) Shows the estimated age when all calibrations were used. ( b ) Shows the estimates when only Proto Oceanic and three ancient languages were used as calibrations.

The pulse–pause scenario makes a third key prediction by proposing a sequence of expansion pulses and pauses. Under this scenario, there were two pauses in the great expansion—the first occurred before the Austronesians entered the Philippines around 5000–4000 years ago, and the second occurred after the settlement of Western Polynesia (Fiji, Samoa, Tonga) starting around 2800 years ago. We tested this prediction in two ways. First, we identified the branches on our trees corresponding to these two pauses ( figure 4 ). The length of the branches again represents the number of changes in cognate sets. If these pauses did occur, then those branches should be much longer than others owing to the increased amount of time for linguistic change. Indeed, the length of these branches was significantly longer than the overall branch-length distribution, providing good evidence that pauses did occur in the predicted locations.

The pulse–pause scenario predicts pulses as well as pauses. If there were expansion pulses in language change, then we would expect to see increases in language diversification rates after the predicted pauses. To test this prediction, we modelled language diversification rate over our set of language trees. This method identified a number of significant increases in language diversification rates (branches coloured red in figure 4 ). Two of these increases occurred as predicted on the branches just after the two pauses. Intriguingly, we identified some unpredicted pulses as well. The third pulse we identified suggested a more recent population expansion in the Philippines around 2000–2500 years ago as one language subgroup expanded at the expense of others. The fourth pulse occurred in the Micronesian languages and appears to be linked to the second pulse into Polynesia.

What insights can these language dates give us about the great Austronesian expansion? It has been suggested that the first pause might be linked to an inability of the Austronesians to cross the 350 km Bashi channel separating the Philippines from Taiwan [ 47 , 48 ]. Terms for outrigger canoes and sails can only be reconstructed back to the languages occurring after the first pause [ 47 , 48 ]. It seems likely therefore that the invention of the outrigger enabled the Austronesians to cross the channel and spread rapidly across the rest of the Pacific. After travelling 7000 km in 1000 years, what might have caused the Austronesians to stop in Western Polynesia? Expanding into Eastern Polynesia presented the Austronesians with a new range of challenges that would have also required technological or social solutions including: the ability to estimate latitude from the stars, the ability to sail across the prevailing easterly tradewinds, double-hulled canoes for greater stability and carrying capacity, and social strategies for handling the greater isolation [ 60 ].

The results reveal the rapidity of cultural spread. The Austronesians travelled—and settled—the 7000 km between the Philippines and Polynesia in around 1000 years. During this relatively short time, the Austronesian culture not only spread, but developed the collection of technologies known as the Lapita cultural complex [ 5 ]. This complex includes distinctive and elaborately decorated pottery, adzes/axes, tattooing, bark-cloth and shell ornamentation. Our results suggest that either this complex was generated in a very short time-window (four or five generations), or there was substantial post-settlement contact between Near Oceania and the pre-Polynesian society. One possibility is that there is a more complex history in this region. The languages of New Caledonia and Vanuatu show some strikingly non-Austronesian features such as serial verb constructions, and the cultures there show some unusual similarities with some cultures from highland New Guinea—including nasal septum piercings, penis sheathes and mop-like headdresses [ 61 ]. It has recently been suggested that one explanation for these similarities might be two waves of settlement into Remote Oceania, with a first wave of Austronesian-speaking settlers being rapidly followed by a second wave of Papuan peoples who had acquired Austronesian voyaging technology [ 61 ].

5. Conclusion

Some scholars are rather sceptical that anything of substance can come out of attempts to ‘Darwinize culture’. They concede that some loose analogies can be found, but claim that these are rather superficial and unlikely to yield substantive insights into complex cultural processes. In the words of Fracchia & Lewontin [ 62 , p. 14], Darwinian approaches to culture do not ‘contribute anything new except a misleading vocabulary that anesthetises history’. The focus of Fracchia & Lewontin's critique is on selectionist, memetic accounts of historical change. Elsewhere, we have argued that phylogenetic or ‘tree thinking’ provides another way of Darwinizing culture that does not require a commitment to problematic aspects of memetics such as particulate cultural inheritance and tidy lineages of directly copied replicators [ 63 ]. One aspect of phylogenetic inference is the estimation of divergence dates. The accurate estimation of divergence dates is a tricky business. Care needs to be taken to ensure that the calibrations are valid and the inferences are robust to possible model misspecification and undetected borrowing. However, the central theme of this paper has been that when it comes to understanding our past these carefully estimated dates really do make a difference. Robust phylogenetic estimates of linguistic divergence dates give us a powerful tool for testing hypotheses about human prehistory. They enable us to integrate linguistic, archaeological and genetic data, and link major population expansions to innovations in culture such as the development of farming and the invention of the outrigger canoe. In short, a phylogenetic approach to culture illuminates rather than anaesthetizes history.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Lyle Campbell, Kevin Laland, April McMahon, Robert Ross, Andy Whiten and an anonymous referee for their helpful comments on this manuscript. Figures are reprinted with permission from Proceedings of the Royal Society B ( figure 3 ) and Science ( figure 4 ). This work was funded by Marsden grants from the Royal Society of New Zealand.

One contribution of 26 to a Discussion Meeting Issue ‘ Culture evolves ’.

Indo-European languages: new study reconciles two dominant hypotheses about their origin

Profesor Titular (lingüística, traducción), Universitat Jaume I

Disclosure statement

Kim Schulte has worked on "IE-CoR: A Database on Cognate Relationships in ‘core’ Indo-European vocabulary ", funded by the Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

Universitat Jaume I provides funding as a member of The Conversation ES.

View all partners

The languages in the Indo-European family are spoken by almost half of the world’s population. This group includes a huge number of languages, ranging from English and Spanish to Russian, Kurdish and Persian.

Ever since the discovery, over two centuries ago, that these languages belong to the same family, philologists have worked to reconstruct the first Indo-European language (known as Proto-Indo-European) and establish a “language family tree”, where branches represent the evolution and separation of languages over time. This approach draws on phylogenetics – the study of how biological species evolve – which also provides the most appropriate model for describing and quantifying the historical relationships between languages.

Despite numerous studies, many questions still remain as to the origin of Indo-European: where was the original Indo-European language spoken in prehistoric times? How long ago did this language group emerge? How did it spread across Eurasia?

Anatolia or the Pontic Steppe?

There are two main, though apparently contradictory, established hypotheses. On one side we have the Anatolian Hypothesis , which traces the origins of the Indo-European people to Anatolia, in modern day Turkey, during the Neolithic era. According to this hypothesis, created by British archaeologist Colin Renfrew , Indo-European languages began to spread towards Europe around 9,000 years ago, alongside the expansion of agriculture.

On the other side we have the Steppe Hypothesis , which places the origin of Indo-European languages further north, in the Pontic Steppe . This theory states that Proto-Indo-European language emerged somewhere north of the Black Sea around 5,000 or 6,000 years ago. It is linked to Kurgan culture , known for its distinctive burial mounds and horse breeding practices.

DNA comparison

In order to decide which of these two hypotheses is correct, genetic studies have been carried out to compare DNA found at prehistoric sites with that of modern humans. However, this type of research can only provide indirect clues as to the origins of Indo-European languages, since language, unlike, for example, blood type, is not inherited through genes.

A new study published in Science has approached the question from a different angle by using direct linguistic data to assess the timelines put forward by both hypotheses.

In this project, carried out by over 80 linguists under the direction of Paul Heggarty and Cormac Anderson from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, we applied a new methodology that allowed us to obtain more exact results.

More comprehensive sampling

The samples used in earlier phylogenetic studies were taken from a limited pool of languages. Moreover, some analyses had assumed that modern languages are derived directly from ancient written languages, when they actually come from oral variants that were spoken during the same period – Spanish, for example, did not come from the classical Latin found in Virgil’s works, but from the popular or “vulgar” Latin which was spoken by ordinary people. These shortcomings and assumptions have distorted age estimates for Indo-European language family subgroups such as Germanic, Slavic or Romance.

The new study addresses these issues, eliminating inconsistencies and taking data from a wider range of sources (from 161 languages, to be exact), to provide a more balanced and complete sample set. This data then underwent a Bayesian phylogenetic analysis , a statistical method for establishing the most probable relationships between languages and branches of the family tree.

The study showed, for example, that an Italo-Celtic language family cannot exist, since the Italic and Celtic languages separated several centuries before the separation of the Germanic and Celtic languages, which took place around 5,000 years ago.

An eight thousand year old language family

Regarding the question of the origin of Indo-European languages, calculations based on the new data show that they were first spoken approximately 8,000 years ago.

The results of this research do not line up neatly with either the Anatolian or the Kurgan hypotheses. Instead they suggest that the birthplace of Indo-European languages is somewhere in the south of the Caucasus region. From there, they then expanded in various directions: westward towards Greece and Albania; eastward towards India, and northward towards the Pontic Steppe.

Around three millennia later there was then a second wave of expansion from the Pontic Steppe towards Europe, which gave rise to the majority of the languages that are spoken today in Europe. This hybrid hypothesis, which marries up the two previously established theories, also aligns with the results of the most recent studies in the field of genetic anthropology.

In addition to bringing us closer to solving the centuries-old enigma of the origin of our languages, this research illustrates how disciplines as disparate as genetics and linguistics can complement each other to provide more reliable answers to questions of human prehistory. It is hoped that the same methodology will also serve, in future research, to expand our understanding of how languages and populations spread to other continents.

This article was originally published in Spanish

- The Conversation Europe

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Partner, Senior Talent Acquisition

Deputy Editor - Technology

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic and Student Life)

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 27 November 2003

Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin

- Russell D. Gray 1 &

- Quentin D. Atkinson 1

Nature volume 426 , pages 435–439 ( 2003 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

491 Citations

107 Altmetric

Metrics details

Languages, like genes, provide vital clues about human history 1 , 2 . The origin of the Indo-European language family is “the most intensively studied, yet still most recalcitrant, problem of historical linguistics” 3 . Numerous genetic studies of Indo-European origins have also produced inconclusive results 4 , 5 , 6 . Here we analyse linguistic data using computational methods derived from evolutionary biology. We test two theories of Indo-European origin: the ‘Kurgan expansion’ and the ‘Anatolian farming’ hypotheses. The Kurgan theory centres on possible archaeological evidence for an expansion into Europe and the Near East by Kurgan horsemen beginning in the sixth millennium BP 7 , 8 . In contrast, the Anatolian theory claims that Indo-European languages expanded with the spread of agriculture from Anatolia around 8,000–9,500 years bp 9 . In striking agreement with the Anatolian hypothesis, our analysis of a matrix of 87 languages with 2,449 lexical items produced an estimated age range for the initial Indo-European divergence of between 7,800 and 9,800 years bp . These results were robust to changes in coding procedures, calibration points, rooting of the trees and priors in the bayesian analysis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

The time and place of origin of South Caucasian languages: insights into past human societies, ecosystems and human population genetics

Alexander Gavashelishvili, Merab Chukhua, … Mehmet Somel

Phylogenetic evidence for Sino-Tibetan origin in northern China in the Late Neolithic

Menghan Zhang, Shi Yan, … Li Jin

Dated phylogeny suggests early Neolithic origin of Sino-Tibetan languages

Hanzhi Zhang, Ting Ji, … Ruth Mace

Pagel, M. in Time Depth in Historical Linguistics (eds Renfrew, C., McMahon, A. & Trask, L.) 189–207 (The McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, UK, 2000)

Google Scholar

Gray, R. D. & Jordan, F. M. Language trees support the express-train sequence of Austronesian expansion. Nature 405 , 1052–1055 (2000)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Diamond, J. & Bellwood, P. Farmers and their languages: the first expansions. Science 300 , 597–603 (2003)

Richards, M. et al. Tracing European founder lineage in the Near Eastern mtDNA pool. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67 , 1251–1276 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar

Semoni, O. et al. The genetic legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens in extant Europeans: a Y chromosome perspective. Science 290 , 1155–1159 (2000)

Article ADS Google Scholar

Chikhi, L., Nichols, R. A., Barbujani, G. & Beaumont, M. A. Y genetic data support the Neolithic Demic Diffusion Model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99 , 11008–11013 (2002)

Gimbutas, M. The beginning of the Bronze Age in Europe and the Indo-Europeans 3500–2500 B.C. J. Indo-Eur. Stud. 1 , 163–214 (1973)

Mallory, J. P. Search of the Indo-Europeans: Languages, Archaeology and Myth (Thames & Hudson, London, 1989)

Renfrew, C. in Time Depth in Historical Linguistics (eds Renfrew, C., McMahon, A. & Trask, L.) 413–439 (The McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, UK, 2000)

Swadesh, M. Lexico-statistic dating of prehistoric ethnic contacts. Proc. Am. Phil. Soc. 96 , 453–463 (1952)

Bergsland, K. & Vogt, H. On the validity of glottochronology. Curr. Anthropol. 3 , 115–153 (1962)

Article Google Scholar

Blust, R. in Time Depth in Historical Linguistics (eds Renfrew, C., McMahon, A. & Trask, L.) 311–332 (The McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, UK, 2000)

Steel, M. A., Hendy, M. D. & Penny, D. Loss of information in genetic distances. Nature 333 , 494–495 (1988)

Swofford, D. L., Olsen, G. J., Waddell, P. J. & Hillis, D. M. in Molecular Systematics (eds Hillis, D., Moritz, C. & Mable, B. K.) 407–514 (Sinauer Associates, Inc, Sunderland, Massachusetts, 1996)

Dixon, R. M. W. The Rise and Fall of Language (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, UK, 1997)

Book Google Scholar

Metropolis, N., Rosenbluth, A. W., Rosenbluth, M. N., Teller, A. H. & Teller, E. Equations of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 21 , 1087–1091 (1953)

Huelsenbeck, J. P., Ronquist, F., Nielsen, R. & Bollback, J. P. Bayesian inference of phylogeny and its impact on evolutionary biology. Science 294 , 2310–2314 (2001)

Huson, D. H. SplitsTree: analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics 14 , 68–73 (1998)

Sanderson, M. R8s, Analysis of Rates of Evolution,Version 1.50 (Univ. California, Davis, 2002)

Dyen, I., Kruskal, J. B. & Black, P. FILE IE-DATA1 . Available at 〈 http://www.ntu.edu.au/education/langs/ielex/IE-DATA1 〉 (1997).

Sanderson, M. J. & Donoghue, M. J. Patterns of variation in levels of homoplasy. Evolution 43 , 1781–1795 (1989)

Gamkrelidze, T. V. & Ivanov, V. V. Trends in Linguistics 80: Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans (Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, 1995)

Rexova, K., Frynta, D. & Zrzavy, J. Cladistic analysis of languages: Indo-European classification based on lexicostatistical data. Cladistics 19 , 120–127 (2003)

Ringe, D., Warnow, T. & Taylor, A. IndoEuropean and computational cladistics. Trans. Philol. Soc. 100 , 59–129 (2002)

Gkiasta, M., Russell, T., Shennan, S. & Steele, J. Neolithic transition in Europe: the radiocarbon record revisited. Antiquity 77 , 45–62 (2003)

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., Menozzi, P. & Piazza, A. The History and Geography of Human Genes (Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, 1994)

MATH Google Scholar

Holden, C. J. Bantu language trees reflect the spread of farming across sub-Saharan Africa: a maximum-parsimony analysis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269 , 793–799 (2002)

Barbrook, A. C., Howe, C. J., Blake, N. & Robinson, P. The phylogeny of The Canterbury Tales. Nature 394 , 839 (1998)

McMahon, A. & McMahon, R. Finding families: Quantitative methods in language classification. Trans. Philol. Soc. 101 , 7–55 (2003)

Huelsenbeck, J. P. & Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformatics 17 , 754–755 (2001)

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Allan, L. Campbell, L. Chikhi, M. Corballis, N. Gavey, S. Greenhill, J. Hamm, J. Huelsenbeck, G. Nichols, A. Rodrigo, F. Ronquist, M. Sanderson and S. Shennan for useful advice and/or comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, 1020, Auckland, New Zealand

Russell D. Gray & Quentin D. Atkinson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Russell D. Gray .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary table (doc 35 kb), rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gray, R., Atkinson, Q. Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin. Nature 426 , 435–439 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02029

Download citation

Received : 18 July 2003

Accepted : 22 August 2003

Issue Date : 27 November 2003

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02029

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Inferring language dispersal patterns with velocity field estimation.

- Menghan Zhang

Nature Communications (2024)

Machine culture

- Levin Brinkmann

- Fabian Baumann

- Iyad Rahwan

Nature Human Behaviour (2023)

Reliability models in cultural phylogenetics

- Rafael Ventura

Biology & Philosophy (2023)

Valence-dependent mutation in lexical evolution

- Joshua Conrad Jackson

- Kristen Lindquist

- Joseph Watts

Nature Human Behaviour (2022)

An evolutionary view of institutional complexity

- Victor Zitian Chen

- John Cantwell

Journal of Evolutionary Economics (2022)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- Undergraduate courses

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Postgraduate courses

- How to apply

- Postgraduate events

- Fees and funding

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Term dates and calendars

- Visiting the University

- Annual reports

- Equality and diversity

- A global university

- Public engagement

- Give to Cambridge

- For Cambridge students

- For our researchers

- Business and enterprise

- Colleges & departments

- Email & phone search

- Museums & collections

- Cambridge Language Sciences

- About overview

- Directory overview

- Academic Staff

- Graduate Students

- Associate Members

- Visiting Scholars

- Editing your profile

- Impact overview

- Policy overview

- Languages, Society and Policy

- Language Analysis in Schools: Education and Research (LASER)

- Is it possible to differentiate multilingual children and children with Developmental Language Disorder (DLD)?

- Refugee Access to Early Childhood Education and Care in the UK

- Modern Languages Educational Policy in the UK

- Multilingualism and Wellbeing in UK

- The Educated Brain seminar series

- What is the value of languages in the UK?

- Improving support for pupils with English as an additional language

- Events overview

- Upcoming Events

- Research Strategy Forum

- Past Events

- Funding overview

- Language Sciences Incubator Fund overview

- Incubator Fund projects

- Eligibility & funding criteria

- Feedback from awardees

- Language Sciences Workshop Fund overview

- Workshops funded

- Language Sciences Impact Fund

- Jobs & Studentships

- Graduate Students overview

- Language Sciences Interdisciplinary Programme overview

- Applying for the Programme

- Sharable Options

- Examples of Research Projects

New evidence supports Anatolia hypothesis for origins of English

Submitted by Administrator on Thu, 30/08/2012 - 11:34

A recent study published in Science , and reported by news agencies including the BBC, backs a hypothesis about the origins of the Indo-European languages (including English) first proposed by the distinguished Cambridge archaeologist Professor Colin Renfrew (Lord Renfrew of Kaimsthorn) in 1987.

Professor Renfrew's Anatolian hypothesis suggested that modern Indo-European languages originated in Anatolia in Neolithic times, and linked their arrival in Europe with the spread of farming. The alternative, and for many years, the more accepted view was that Indo-European languages originated around 3,000 years later in the Steppes of Russia (the Kurgan hypothesis ).

Researchers in New Zealand led by Dr. Quentin Atkinson of the University of Auckland have now applied research techniques used to trace virus epidemics to the study of language evolution. Using very different methods to those used by Professor Renfrew in the 1980s, they tested both the Anatolian and the Kurgan hypotheses, and their findings support the former.

Professor Renfrew comments:

"The hypothesis, which I put forward 25 years ago in my book Archaeology and Language , that the original home of the first Indo-European language was in Anatolia, was based on archaeological evidence that early farming (and the increase in population density that came with it) came to Europe from Anatolia. The argument was that the widespread adoption of a new language required a major economic and demographic change, such as the adoption of farming. Supporting evidence has come through since then that the wide regional distribution of several other language families (including Austronesian and Bantu) came about as the result of early farming dispersals.

The new and impressive finding by Quentin Atkinson and his colleagues is based on the phylogeographic analysis of purely linguistic data, and thus comes to much the same conclusion independently, using very different evidence. This gives striking support to the Anatolian hypothesis.

The traditional view that the homeland of the Proto-Indo-Europeans was in the steppe lands north of the Black Sea derives from the old misconception that the early population of that area were mounted warrior nomad pastoralists, who allegedly invaded Europe around the beginning of the Bronze Age. Few archaeologist now believe that. But this old myth dies hard. In reality, the development of mounted cavalry did not much pre-date the Scythians of the first millennium BC.

Much emphasis is traditionally placed by some Indo-Europeanists on just a few vocabulary terms, such as those for ‘horse’, ‘wheel’, chariot’, ‘cart’ etc. on the very reasonable grounds that these features make their appearance relatively late in the archaeological record. Since there are words for these things in the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language, that language cannot (they argue) have dispersed before the invention, for instance, of the wheel. But these linguists sometimes use this method of linguistic palaeontology in a rather cumbersome way. They sometimes fail to acknowledge that with the invention of a new concept (e.g. the wheel), the new noun that was invented for it in the by-then different early Indo-European languages was often derived from existing concepts (e.g. ‘to rotate’ for the Latin rota , and similarly for the reconstructed Indo-European * kweklos , related to the Greek kyklos , ‘circle’). Circles and rotation have been known to humans for tens of thousands of years and cannot be used to date Proto-Indo-European!"

Follow the links for more on this item.

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/337/6097/957.abstract?sid=192102e8-a5bc-4744-ac5a-5500338ab381

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-19368988

Cambridge Language Sciences is an Interdisciplinary Research Centre at the University of Cambridge. Our virtual network connects researchers from five schools across the university as well as other world-leading research institutions. Our aim is to strengthen research collaborations and knowledge transfer across disciplines in order to address large-scale multi-disciplinary research challenges relating to language research.

JOIN OUR NETWORK

JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

- 12 Jul 10th Cambridge Conference on Language Endangerment

- 21 Nov Language Sciences Annual Symposium 2024: How can learning a second language be made effortless?

View all events

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- Contact the University

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

- Privacy policy and cookies

- Statement on Modern Slavery

- Terms and conditions

- University A-Z

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- Research news

- About research at Cambridge

- Spotlight on...

May 1, 2016

12 min read

Farmers vs. Nomads: Whose Lingo Spread the Farthest?

Did the most successful family of languages in history originate in Turkey or the Pontic steppes? New evidence from DNA and evolutionary biology has only heightened the scientific disagreements

By Michael Balter

Mark Allen Miller

“What's in a name?” asked Juliet of Romeo. “That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” A real-life Juliet probably would have spoken to Romeo in an obscure medieval Italian dialect rather than Shakespeare's English. Nevertheless, her word for the sweet-smelling flower would have shared the same linguistic root ( rosa , in modern Italian) as the English version does and indeed as many other languages spoken throughout Europe do— Rose , capitalized in German fashion, or the lowercase French rose . Croatian? An aromatic ruža . To the nearly 60,000 Scots who still speak the ancient Scottish Gaelic, this symbol of passionate love is a ròs .

Why do such geographically diverse languages use similar words for the same flower? All these tongues, along with more than 400 others, belong to the same family of languages—the incredibly far-flung Indo-European language family—and have a common origin. Indo-European languages, which include Greek, Latin, English, Sanskrit, and many languages spoken in Iran and on the Indian subcontinent, are the most dominant linguistic group in the history of humanity. They account for about 7 percent of the world's estimated 6,500 languages but are nonetheless spoken by three billion people—nearly half the world's population. Understanding how, why and when they spread so readily is key to understanding the social, cultural and demographic changes that created today's diverse populations in Europe and much of Asia. As Paul Heggarty, a linguist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany, puts it: “We have to explain why Indo-European was so outrageously, overpoweringly successful.”

Because words and languages do not fossilize, the task of tracking their movements across time and space was left for more than a century to traditional linguists and a small number of archaeologists. Recently, however, the search for Indo-European origins has gone high tech, as biologists and experts in ancient DNA have gotten into the act. Armed with new theoretical and statistical approaches, these investigators have begun to transform linguistics from a paper-and-pencil exercise into a field that uses powerful computers and methods borrowed from evolutionary biology to trace language origins.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

You might think that this attempt to modernize linguistics would bring researchers closer to an understanding of where and when the Indo-European languages arose. But in many ways, the opposite has happened, and the question is in even greater dispute. Everyone agrees on one key point: the Indo-European languages descend from a common ancestor, a mother tongue called Proto-Indo-European, or PIE. But as to why this particular language produced so many linguistic offspring or where it originated, there is no accord.

Researchers have fallen into two warring camps. One camp, which includes the majority of traditional linguists, argues that Central Asian nomads, who invented the wheel and domesticated the horse, spread the mother tongue throughout Europe and Asia beginning about 6,000 years ago. The other camp, led by British archaeologist Colin Renfrew, credits early farmers from more than 500 miles to the south in what is now Turkey with disseminating the language at some point after they began spreading their agricultural know-how 8,500 years ago.

Over the years first one idea then another has had the upper hand. Evolutionary biologists published a series of studies in 2003 that concluded that the Indo-European family tree originated in the Middle East at least 8,000 years ago, based on the idea that the evolution of words can mimic the evolution of living organisms; their results are consistent with the farmer hypothesis. In the past year or two some linguists, archaeologists and geneticists struck back, using rival computational analyses and samples of DNA from ancient skeletons to support the nomad hypothesis. And so the pendulum continues to swing.

The Horse, of Course

Scholars did not have to wait for high-speed computers to recognize connections among the Indo-European languages. That realization dawned as early as the 1700s, after Europeans had begun to travel far afield. Some of the parallels among widely distributed tongues are now seen as dead giveaways. Thus, the Sanskrit and Latin words for “fire,” agní - and ignis , clearly indicate their Indo-European family ties.

By the 19th century, linguists were sure there must be a common ancestor for all Indo-European languages. “There was a sense of shock that the classical languages of European civilization sprang from the same source as Sanskrit, an exotic language spoken in India, on the other side of the world,” says David Anthony, an archaeologist at Hartwick College and a fierce advocate of PIE's nomadic origin.

So linguists set about reconstructing this ancestral tongue. Sometimes this was not too difficult, especially if the original word had not changed unrecognizably. For example, linguists could take the English word “birch,” the German Birke , the Sanskrit bhūrjá and other Indo-European words for this slender tree and, by applying basic linguistic rules of language change, extrapolate backward to figure out that the PIE root was something like * bherh 1 ǵ - (the asterisk indicates that this is a reconstructed word for which there is no direct evidence). Other reconstructions are not as obvious. Thus, the PIE word for “horse”— áśva - in Sanskrit, híppos in Greek, equus in Latin and ech in Old Irish—was determined to be * h 1 éḱwo (the subscript 1 refers to a sound made in the back of the mouth).

But when some linguists tried to identify the peoples behind the language, things became trickier. These scholars began linking certain cultures with PIE, an approach called linguistic paleontology. They noticed that PIE contained many terms for domesticated animals, such as horses, sheep and cattle, and began postulating a pastoral Indo-European “homeland.”

That approach eventually led to trouble. In the early 20th century German prehistorian Gustaf Kossinna proposed that a group of Central European settlers, who created intricately engraved pottery called Corded Ware starting 5,000 years ago, were in fact the first Indo-Europeans. Kossinna argued that they later spread out of what is today Germany, carrying their language with them. That idea was music to the ears of the Nazis, who resurrected the term “Aryan” (a 19th-century term for Indo-Europeans), along with its connotations of racial superiority.

The Nazi endorsement gave Indo-European studies a bad name for many years. Many researchers give credit to Marija Gimbutas, an archaeologist who died in 1994, for making the subject respectable again, starting in the 1950s. Gimbutas situated the origins of PIE in the so-called Pontic steppes north of the Black Sea. For her, the prime mover of PIE was the Copper Age Kurgan culture, which can first be identified in the archaeological record about 6,000 years ago. After a millennium of roaming the barren steppes—in which the nomads learned how to domesticate the horse—Gimbutas argued, they charged forth into Eastern and Central Europe, imposing their patriarchal culture as well as the strongly enunciated vowels and consonants of their native Indo-European language. More specifically, Gimbutas identified the Yamnaya people, who lived in the Pontic steppes between about 5,600 and 4,300 years ago, as the original PIE speakers.

Other researchers also found evidence to support such a view. In 1989 David Anthony began working in Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan, focusing on horse teeth that had been earlier excavated by Soviet archaeologists. Anthony and his colleagues confirmed previous suggestions that there was bit wear on teeth dated as early as 6,000 years ago, pushing back the earliest evidence for horse domestication—and horse riding—by about 2,000 years. Their studies also provided evidence to link several technological developments—including the use of wheeled vehicles such as chariots—to the Yamnaya people. These finds supported the idea that the steppe pastoralists had the necessary transportation and technology to fan out rapidly from their homeland and spread their language in all directions.

Revolutionary Farmers

The steppe hypothesis, also known as the kurgan hypothesis, after the kurgans, or burial mounds, in which the pastoralists buried their chiefs, was rarely questioned until the 1980s. Then Renfrew put forth a radically different idea, called the Anatolian hypothesis. ( Anatolia , from the Greek for “sunrise,” refers to present-day Turkey.) Renfrew, the dean of British prehistorians, who now sits in the House of Lords, had spent years digging in Greece and was struck by how much the artifacts he unearthed, especially the carved female figurines, resembled those from earlier archaeological sites in Turkey and the Middle East.

Archaeologists already knew that farming spread from the Middle East to Greece first. Renfrew wondered if there might be a continuity of language in addition to culture. Thus, the first PIE speakers, he posited in lectures and a book, might be the farmers who moved from Anatolia to Europe 8,500 years ago, bringing their words along with their agricultural practices.

Traditional linguists, who had spent decades working painstakingly with paper and pencil to reconstruct PIE by tracing modern Indo-European words back to their original roots, were outraged. Most dismissed the Anatolian hypothesis, sometimes with bitter invective. One University of Oxford professor called the idea “rubbish,” and another skeptic declared that “a naive reader would be grossly misled by the simplistic solutions that the author offers.”

Renfrew and his supporters fought back, arguing that the steppe hypothesis cannot explain the broad expansion of PIE from wherever it began across both Europe and Asia. Researchers know that PIE-derived languages were spoken as far west as Ireland and as far east as the Tarim Basin, in what is now northwestern China, and down into India. A key question is how PIE would have gotten from the steppes to East Asia if the kurgan hypothesis were right. Did it spread to the north around the Black and Caspian seas, as in the steppe hypothesis? Renfrew sees no archaeological evidence for this route. Or did PIE take a southerly and earlier path to the east from Anatolia? He thinks it more likely that PIE spread south around the Black Sea from Turkey and then along early trade routes through Iran and Afghanistan.

Thus, Renfrew believes, only an Anatolian origin can account for PIE's simultaneous spread to the east and west because the peninsula offers the best historical evidence of movement between the European and Asian continents. And the only sociotechnological driver powerful enough to propel the language so far in opposite directions, he adds, was the advent of agriculture, which appeared in the Fertile Crescent—just south and east of modern Turkey—roughly 11,000 years ago. This transition of human society from hunter-gatherers into settled farming communities marked the so-called Neolithic Revolution and was “the only big thing that happened on a Europe-wide basis,” Renfrew says. “If you wanted a simple theory for the coming of the Indo-European languages, the Neolithic was the best thing to hang it on.”

Emblematic of the linguists' objections to Renfrew's Anatolian hypothesis is the origins of the word “wheel.” The reconstructed PIE root is * k w ék w lo -, which became cakrá - in Sanskrit, kúklos in Greek and kukäl in Tocharian A, an extinct Indo-European language of the Tarim Basin. The earliest evidence for wheeled vehicles—depictions on tablets from ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq)—dates to about 5,500 years ago. The actual remains of wagons and carts show up in kurgans beginning about 5,000 years ago.

Many linguists have argued that the PIE root for “wheel” could not have arisen until the object was invented, and so PIE cannot be much earlier than 5,500 years—or about 5,000 years after the invention of agriculture. “That doesn't mean the PIE speakers invented wheels,” Anthony says, “but it does mean that they adopted their own words for the various parts of wheeled vehicles.”

But Renfrew and others counter that the word * k w ék w lo - derives from a much earlier root meaning “to turn” or “to roll” and only later was adapted as a name for the wheel. “There was a whole language about rotation before the wheel was invented,” Renfrew says.

Andrew Garrett, a linguist at the University of California, Berkeley, and proponent of the steppe hypothesis, agrees that the PIE word for “wheel” has an earlier derivation, the root *k