Feedback toolkit: 10 feedback case studies or ideas

This resource contains case studies and ideas on feedback practices across the higher education sector.

This resource is part of the HEA new to teaching Feedback Toolkit.

The materials published on this page were originally created by the Higher Education Academy.

©Advance HE 2020. Company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales no. 04931031 | Company limited by guarantee registered in Ireland no. 703150 | Registered charity, England and Wales 1101607 | Registered charity, Scotland SC043946 | VAT Registered number GB 152 1219 50. Registered UK Address: Advance HE, Innovation Way, York Science Park, Heslington, York, YO10 5BR, United Kingdom | Registered Ireland Address: Advance HE, First Floor, Penrose 1, Penrose Dock, Cork, T23 Kw81, Ireland.

Learn / Guides / Feedback guide

Back to guides

5 inspiring examples of user feedback's impact on real businesses

There are many reasons to collect customer feedback and keep track of your user sentiment—it’s something we encourage every business looking for a deeper understanding of their customers to do.

But perhaps you already know about the various types of user feedback, and understand the steps needed to collect and analyze it. Now, you’re curious to see real-life proof of its effectiveness from businesses like yours.

Last updated

Reading time.

Want to discover the user feedback tactics a popular ecommerce business employed to gain a 400% return on investment (ROI) ? Or learn how an online real estate company used customer feedback to spot and resolve bugs that could have hurt conversions?

Keep reading to discover how five companies tapped into deeper customer insights with user feedback .

Improve your website’s UX with one simple tool

Use Hotjar Feedback to gather valuable insights and make customer-centric improvements to your user experience.

How user feedback insights impacted 5 businesses

From retailers to airlines, start-ups to 10,000-employee-strong corporations—everyone benefits from collecting user feedback and having more customer touchpoints.

We’ve compiled five inspiring case studies from companies that leveraged this crucial qualitative data to improve user experience (UX) and increase conversions.

1. Matalan gained a deeper understanding of their customers

🤔 The situation: the UX team at Matalan, one of the UK’s leading fashion and homeware retailers, wanted to increase conversion rates and improve their ecommerce website’s UX.

Karl Rowlands and Lucy Walton from Matalan’s UX team had a limited budget for gathering customer insights, mainly relying on guesswork guided by quantitative data. While they had no problems assessing performance and tracking numbers, they were missing the why behind the data.

Ultimately, they needed a deeper understanding of their user base to make smarter, more impactful decisions.

💪 The action: Matalan was transitioning its ecommerce website from adaptive to fully responsive, and wanted to collect as many user insights as possible during the process. To make it happen, they turned to Hotjar.

We knew that we needed a tool that would help us understand what our customers think and understand the why behind everything we do.

Along with other tools in the suite, Hotjar’s user feedback tools, Feedback and Surveys , proved invaluable in understanding their website’s UX and inspiring new A/B testing strategies.

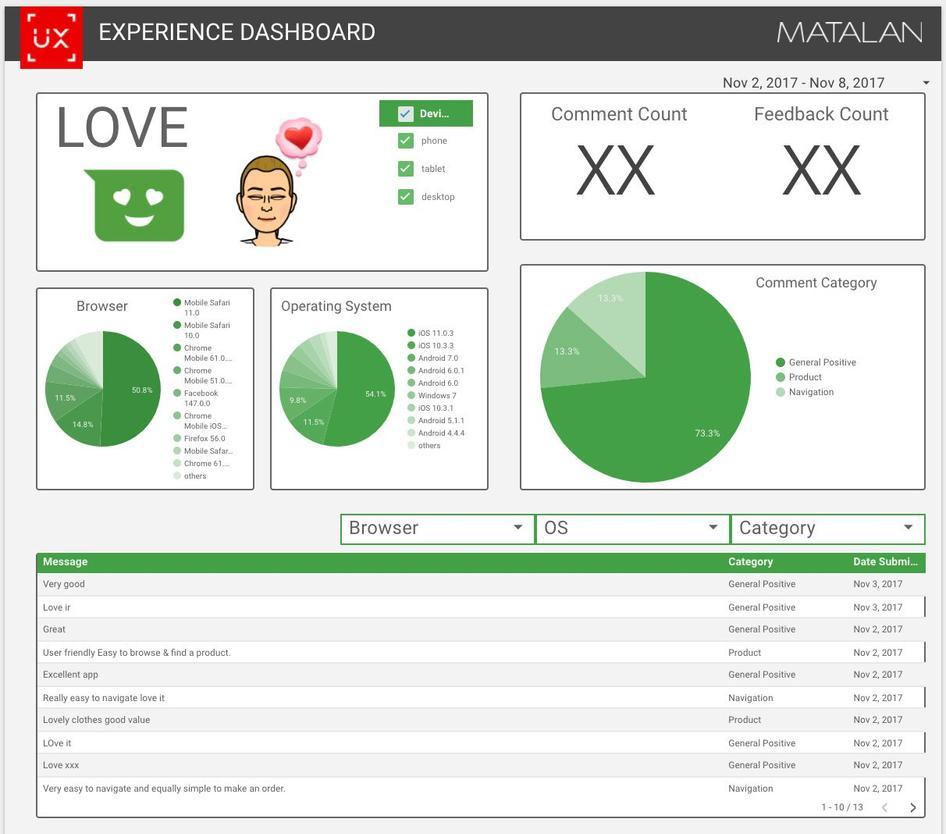

Karl and Lucy integrated Hotjar Feedback with Looker Studio (previously Google Data Studio) to create a dashboard of centralized user responses so they could easily review results and break them down into actionable data.

With their creative solution in place, the team could assess user behavior throughout the transitional period, gradually gathering impressions and gaining visibility into what their users were experiencing.

🏆 The result:

User feedback helped Karl and Lucy’s team spot bugs in the checkout process and resolve them before they became a major blocker to customers, resulting in a 1.23% increase in conversion rates

Feedback also revealed what customers liked or disliked about the company, and what they needed. This gave the team more ideas to trial with A/B testing, earning a 17% boost in successful tests.

Overall, Matalan saw a whopping 400% ROI in just nine months of investing in Hotjar’s user feedback tools

Hotjar really empowers you to see exactly what your users are doing, how they’re feeling, and ultimately their reactions to the changes you make. Without Hotjar, we would still be making decisions based on gut instinct instead of qualitative user feedback.

🔥 If you’re using Hotjar

Want to replicate Matalan’s success? Hotjar’s Feedback widget lets you hear genuine opinions from your customers so you can spot bugs and make data-driven optimizations that put their needs first.

Customizable to your site and adaptable to a range of different content, Feedback can be tailored to your business goals—so you get the customer insights you need, straight from the source.

2. TechSmith improved their website’s UX

🤔 The situation: to make intelligent, customer-centric product developments and reduce assumptions, the team at software company TechSmith needed input from the real people they were designing for.

The further you go without concrete data, the more leaps you’re making. That’s why we come back to the data very regularly…we're making fewer assumptions, which also means we’re making fewer mistakes in the end.

💪 The action: TechSmith’s goal was to gather tangible insights into how customers navigated the site to make data-driven decisions. The team wanted a user feedback tool that could be easily integrated with other software. This way, the entire company could have access to—and benefit from—their learnings.

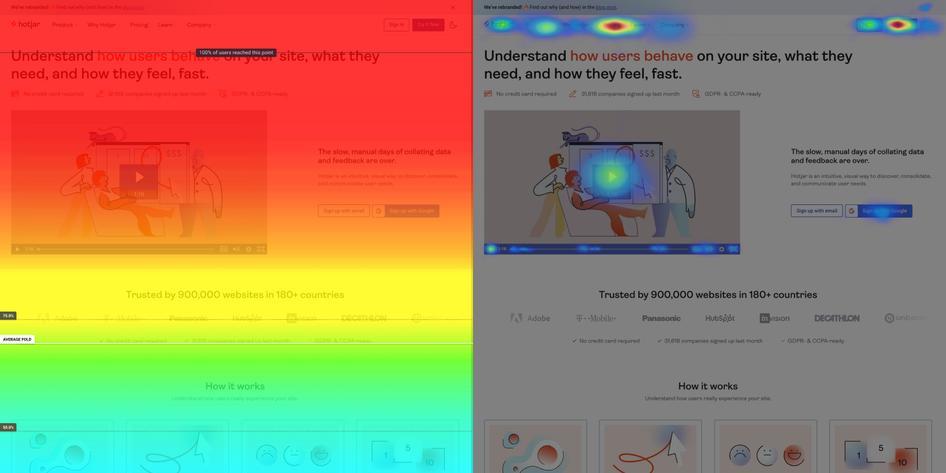

They paired Google Analytics with Hotjar to analyze both traditional, quantitative data and complementary behavior analytics insights:

Hotjar Surveys triggered a survey after a user undertook a certain series of actions so they could target open-ended questions and gather feedback from specific customers and experiences

Hotjar Heatmaps revealed where users spent the most time on each website page

🏆 The result: combining Heatmaps with Surveys—seeing what users said and did —provided a strong case for redesigning parts of TechSmith’s website. By making more areas of their landing pages clickable, the team vastly improved their UX.

Perhaps there was no monetary impact to making the whole area clickable, but it definitely provided a better experience to each of our potential customers.

TechSmith also integrated Hotjar Surveys with other tools, building a database of responses categorized by topic, theme, and user location by exporting the results to Google Sheets.

Now, they had user insights translated into a concrete strategy for the business.

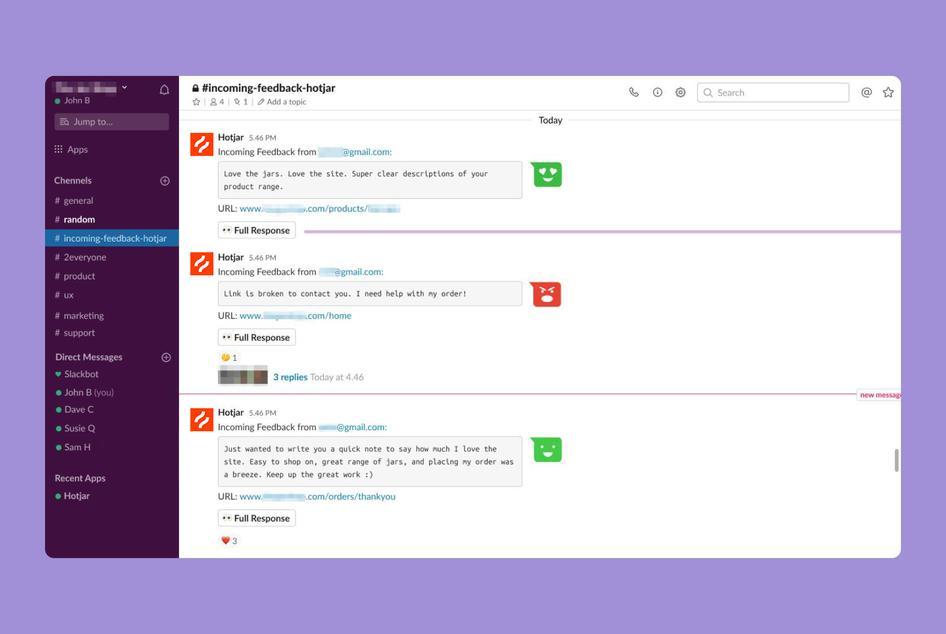

Integrate Hotjar Feedback across various platforms for even better customer awareness .

Keep teams and partners in the loop for maximum responsiveness by linking Feedback with Slack, Gmail, Miro, Asana, and more .

Gather all your insights in one place, filter by the most relevant insights, and export your results into a centralized location for easy analysis.

3. Spotahome used feedback to make educated improvements

🤔 The situation: Spotahome , an online platform for sourcing rentals in various cities, wanted to learn more about their users, reduce the guesswork involved in their website developments, and make educated site optimizations.

Sara Parcero, Spotahome’s Customer Knowledge Manager, was eager to implement budget-conscious user feedback analytics. Her goal was to better understand the context behind conversions and customer behavior, and she chose Hotjar to help her do it.

Before Hotjar, we spent a lot of time guessing what the user thinks before coming up with a solution. Now we don’t guess; we use Hotjar. It’s helped us become a user-centric company.

💪 The action: Hotjar Feedback and Surveys, coupled with Recordings, proved an effective—and affordable—way for Spotahome to tap into large amounts of data that delivered results immediately.

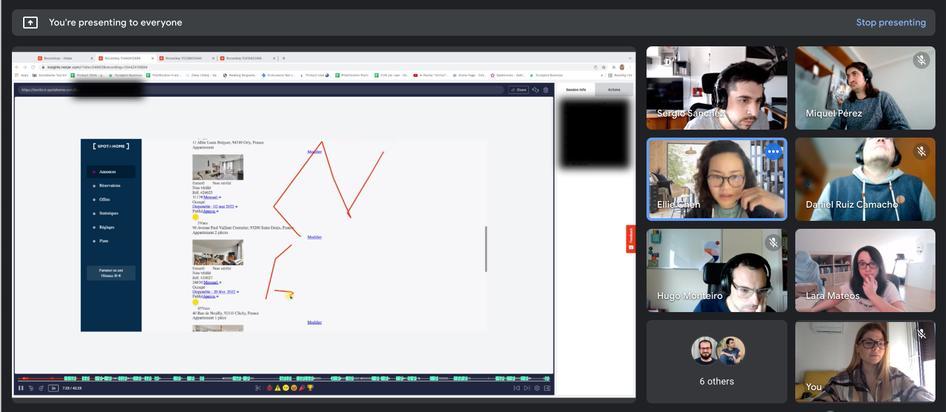

Sara organized company-wide Hotjar Watch Parties to review specific session recordings that were accompanied by feedback responses. This way, stakeholders could see the exact steps users took up until the point of leaving feedback—what they did, where they got stuck, and what they ignored.

Organize your own Hotjar Watch Party!

Get your whole team or company involved in watching your user behavior first-hand in four simple steps:

🔎 Choose one or two topics to be the focus of your Watch Party

📹 Organize your recordings by relevance for the most useful insights

📝 Create a guest list of different teams and disciplines for a variety of perspectives

🍿 Grab some snacks, share your screen, and get the party started !

The Spotahome team during a recordings watch party

Sara compiled responses gathered using the Hotjar Feedback widget, and built reports to give the company visibility into overall website performance and user sentiment. These reports became a source of inspiration to other teams for new features, bug fixes, and general improvements.

With the Engineering and Product teams involved, Sara had the right people bringing their expertise to the table and keeping tabs on user behavior, improving their overall understanding of user needs

Using Feedback with Recordings allowed developers to see real users interact with the product, and get context behind the feedback. This unfiltered line of communication from end users made getting buy-in for optimizations and features a straightforward, data-informed process.

These tools also provided visibility into bugs or flaws that could be quickly and responsively resolved

The company now relies on user feedback for regular pulse checks, making direct improvements based on customers’ comments and keeping the team on a path of constant improvement and competitive analysis.

I know that once you see Hotjar, you’ll see the value. I didn’t need to convince people that Hotjar was great. I just needed to show them.

4. Ryanair spotted trends in user satisfaction

🤔 The situation: Ryanair , an Irish discount airline that sees an average of almost 2 million visitors to their site every day, is committed to providing as seamless a user experience as possible.

With so many people passing through their site, Rui Pereira, Head of Research and Usability, and Anna Zajac, UX Researcher, knew they needed to provide a stellar experience.

The broad range of customers interacting with their product meant there was huge potential to collect impressions of their website, and Hotjar was the ideal platform to help them do it.

💪 The action: Rui and Anna studied the flow of their typical customer’s journey onsite, from searching for flights to booking hotel rooms. Their goal? To understand what brought visitors to their site, and how they interacted with the platform.

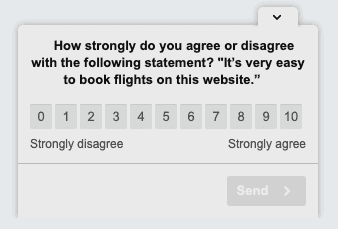

They asked open-ended questions with surveys to get to the root of their customer pain points and spot potential areas for optimizations.

After gathering responses for several months, the team built a database of feedback, providing a full spectrum of insights into their user experience.

The value of Hotjar, for us, is that we can observe trends. We can compare one month with another, and we find this useful.

💡 Pro tip: asking open-ended questions is an excellent way to let customers take the lead in telling you their website impressions or product feedback.

While close-ended questions only permit one answer ( “Did you enjoy using our website?” ), open-ended questions allow for more variety in responses ( “How could our website be improved?” ) so your customer can share their unique perspective

N26 uses a combination of open- and closed-ended questions in this survey

🏆 The result: by integrating Hotjar Surveys with Excel, Rui and Anna got a clear picture of their customers’ sentiments. These insights revealed pain points, wins, and opportunity areas in one cohesive database.

Once they were aware of the most common issues their users experienced, they crafted targeted survey questions directly addressing these website problems.

Customers could then quickly and easily select the issue applying to their situation rather than type out complex responses, streamlining the team’s feedback categorization and making analysis much easier.

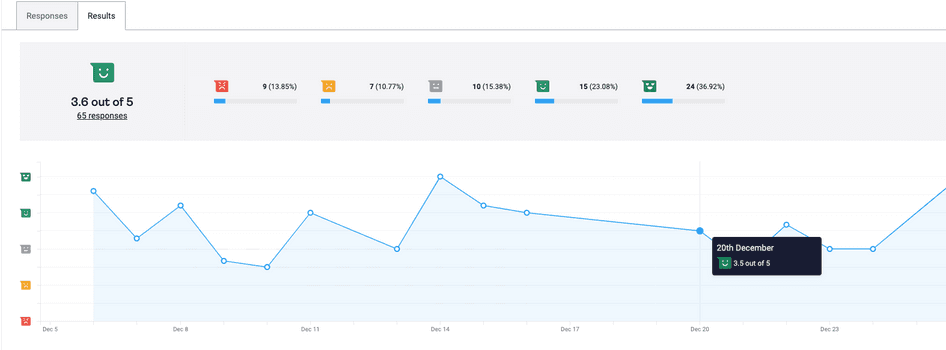

The data revealed trends in customer satisfaction and sentiment over time, which was presented to major stakeholders to get buy-in for specific optimizations and share knowledge about the website’s overall health.

These metrics led to data-driven, customer-centric decisions , and increased awareness of their UX and opportunity areas across the company.

The main stakeholders in our business want to keep track of product performance. We use Hotjar Surveys to see how satisfied our customers are with our products, and we report the larger trends.

Hotjar Feedback gathers all your user sentiments in one place so you clearly see trends in happiness or frustration levels, centralized on your dashboard.

Take your customer feedback and turn it into intuitive, easy-to-understand visuals that transform qualitative data into actionable insights.

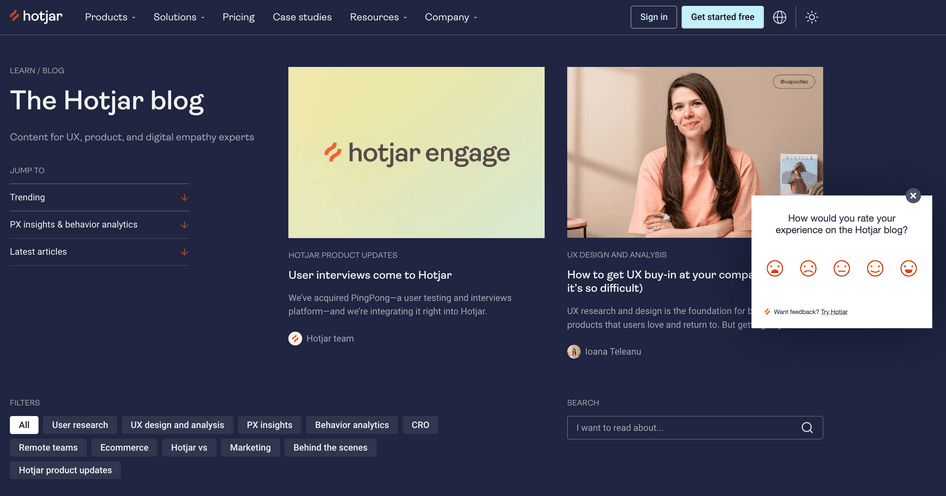

5. Hotjar used its own tools to streamline its entire user experience and build empathy with customers

🤔 The situation: Hi, we’re Hotjar ! 👋 You’re probably not surprised to hear that we’re constantly searching for ways to understand our customers better and improve our product.

The Hotjar team used Hotjar to investigate Hotjar ’s UX (phew!) and uncover any user pain points or elements not meeting customers’ needs.

Our goal was to develop a deeper understanding of how users interacted with our product and optimize accordingly. We also wanted a clearer view of the whys behind user behavior, and deeper context into our customer’s journey through the product.

💪 The action: by applying Hotjar’s user feedback tools, we gathered insights from various channels and sources.

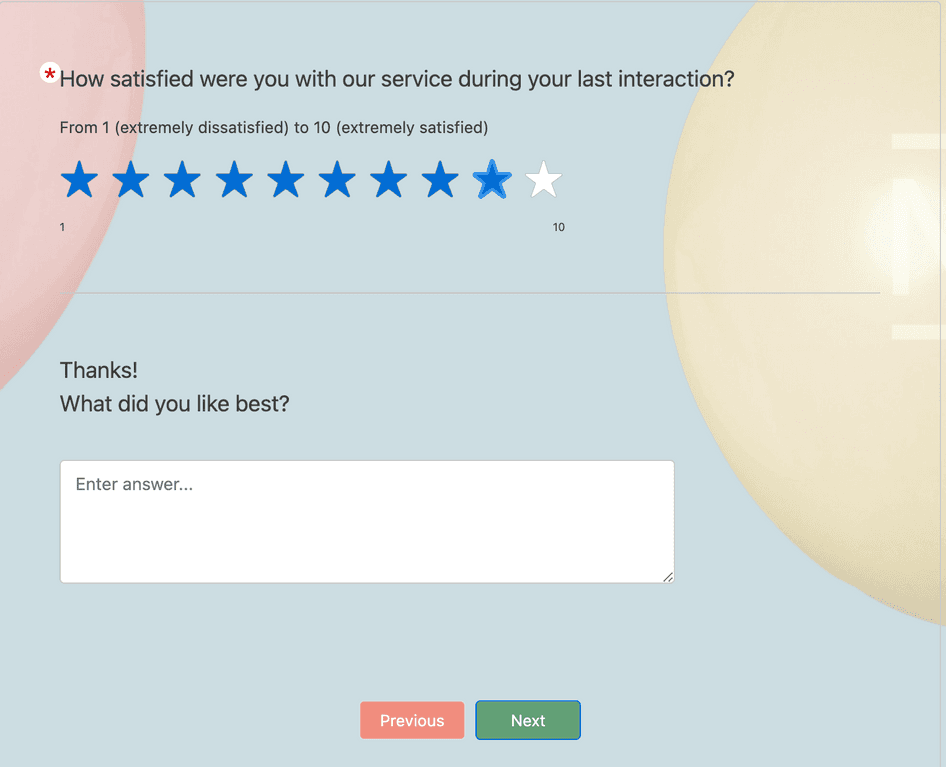

Feedback continually gathered in-the-moment impressions from users across a variety of pages on the website

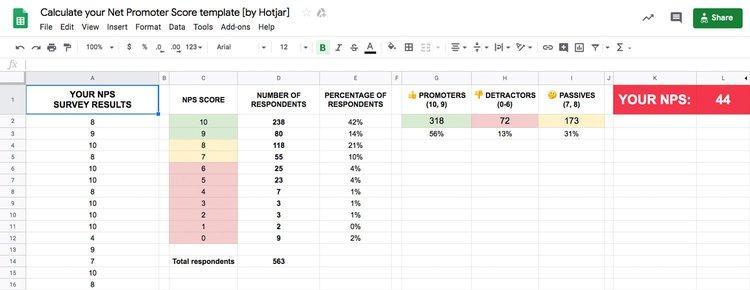

Net Promoter Score® (NPS) surveys assessed sentiment over longer periods and allowed customers to provide more context

We asked a mix of open- and close-ended questions, and regularly got together to review results and break them down into simple, actionable data points.

🏆 The result: unbeknownst to the team, a small but significant bug at the tracking code installation stage prevented users from setting up Hotjar. Our user feedback tools revealed this very bug, so we could dive in and fix it before it hurt conversion rates.

Having people from multiple disciplines across the company involved in user feedback analysis made solving problems and strategizing new product features a united effort. It also meant staying on track to creating a best-in-class user experience—and maintaining Hotjar’s reputation as a leader in digital experience insights.

Hotjar Feedback is just one side of the coin

As you’ll probably have noticed from the five case studies above, Hotjar Feedback is most powerful when paired with Surveys, Recordings, and Heatmaps for a truly holistic overview of your customers’ needs.

Use Feedback with Surveys to gain a deeper understanding of your user sentiment and gather greater insights into your user experience

Try it with Heatmaps to see the successes and opportunity areas of your website, and tap into your customers’ loves and pain points

Combine it with Recordings to watch first-hand how your users interact with your site, what makes them tick, and how you can improve your product

A Feedback response and its accompanying recording

Drive improvements with user feedback

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter what industry your business is in, how old your company is, or what your business goals are.

User feedback connects you to your customers, gives you deeper empathy for the user experience, and helps you spot important opportunity areas across your website or product.

Don’t walk, run to your user feedback tools now and start exploring the true potential of your product optimizations.

Get deeper insights into your user experience

Try Hotjar Feedback to fully understand your customers' needs and wants.

FAQs about user feedback examples

What is user feedback.

User feedback is the responses and impressions of the users interacting with your site or product through various media, such as

Forms and surveys

Social media

Review platforms

User testing sessions

What are some benefits of analyzing user feedback?

Analyzing your user feedback helps you gain a better understanding of your user experience, spot opportunities for optimizations, catch bugs and glitches, and guide your business roadmap.

What companies have benefited from user feedback?

Many companies have benefited from implementing user feedback tools and analyzing the results!

This guide looks at:

Hotjar (hi!)

You can read more case studies of businesses that used Feedback and Surveys (along with other Hotjar tools) here .

Feedback analysis

Previous chapter

Advanced feedback tips

Next chapter

- Employee Engagement

- Business Transformation

- Recruitment and Assessments

- AI-driven Chatbot and Forms building

- Future services

- CJH Networks

- Feedback Works

- AFM Solutions

- Alliance membership

- Case studies

Employee feedback Case Studies

Our Alliance can demonstrate a wide range of Employee Survey and Feedback projects. Here are just a couple

35 Tailored Executive Feedback Sessions for global FMCG business

In this instance, Feedback Works helped the senior management team in a global FMCG company achieve a better and deeper understanding of the feedback from all of their colleagues around the world.

With a hands-on approach, 35 tailored executive feedback sessions were presented to all global leaders - including the company's CEO and team - helping to inform strategy for the future.

Survey and feedback training for well known UK Brand

Early in 2020, our Alliance member Feedback Works was contracted by an iconic UK brand to help them understand their employee experience as they were (and are continuing to) manage the unprecedented times we all experienced at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Part of the exercise related to the future growth and direction of the organisation and, to enable the level of insight needed, we built a questionnaire focused on delivering their strategy for the future. To this we added training that enabled their HR Business Partners to build feedback capability to the business to make real change possible.

Feedback for Learning

Closing the assessment loop

Case Studies

Home > Case Studies

- Utility Menu

Case Studies in Formative Feedback at HGSE

Case Studies in Formative Feedback at HGSE

by: Josh Bookin Committing to the use of student feedback is one thing; creating effective methods for doing so is another. To help you in this work, this article highlights the diverse and impactful practices of three HGSE instructors on gathering student feedback. We asked each of these instructors to give us a sense of what the technique is, why they use it, and how they do so.

Mid-course feedback: a chance to take stock and course correct | Jon Star

What is it.

It is relatively common for faculty to gather mid-course feedback, giving students a chance to share their perspective on how the elements of the class are impacting their learning experience. There are many ways to solicit this feedback, and Jon’s current method involves priming students with some things he would like to learn about in particular and then posing just a few open-ended prompts to allow students to share whatever is most important to them. Jon then decides if and how to modify the course accordingly.

“I teach a course on learning and motivation. I’m someone who is supposed to know something about these topics, and I try to reflect that knowledge in how I design my classes. I know giving students some choice and perceived control over aspects of the course is motivating. And gathering feedback consistently through the course, not just at the end, is a key way in which I make this happen,” reflects Jon. He finds great value in creating a space in the middle of the course experience to have students think broadly about what is and is not working for them. This feedback allows Jon to modify various course components to best meet the needs of these particular students while also building a sense of shared ownership.

How to do it?

Perhaps the first thing to decide is when to solicit mid-course feedback. Jon tends to do it no later than the middle of the semester, as he wants to have enough time to have students benefit from any modifications. But he will often do as earlier as a third of the way into the semester, particularly if the class seems like it isn’t coming together in all the ways Jon has intended.

Although he used to employ extensive instruments, Jon has evolved his practice to create a simplified, open-ended questionnaire. He often will prime the feedback session by letting students know that he welcomes feedback about any aspect of the course, but that he is particularly curious about their thoughts on specific components. He will then give them a blank piece of paper and ask them to write on one side things about the class that are working well for them and on the other suggestions they have for improvement. Jon has students complete the survey in class, as it helps them know that he really values the process and it ensures that they spend an adequate amount of time giving feedback.

Jon then synthesizes the feedback, looking for common patterns. He decides how he will use the feedback to modify the course, for instance substituting some of the upcoming assigned readings or tweaking his instructional methods. Jon then reports two things back to the students in the next class: the things he will change, and the things he won’t change and why. This efficient report out gives students a sense of what they and their peers think, informs them about what is going to change, and lets them know that Jon cares about what they think.

Reading response briefs: integrating student feedback into class session design | Candice Bocala

Students complete and submit short written assignments called “reading briefs” in advance of class. The teaching team reviews the briefs to identify common patterns and to decide how to incorporate students’ insights and questions about the reading into designing the class session. The teaching team also gives individual feedback on the briefs.

“This tool gives me much better information about where students are confused, rather than relying only on the information I get from what students say in class or during office hours. Because it is in writing, I can address any misconceptions right away on their brief, and I can also address it in the whole class when useful.” Candice also uses the briefs as a way to help select the topics of discussion that best meet students where they are at. She often invites students to share their responses and questions during the class, thus diversifying participation and sharing discussion leadership.

Candice’s approach to these briefs is well described in her Learning from Practice: Evaluation and Improvement Science syllabus:

“Reading response ‘briefs’: Out of five weeks’ worth of readings, students are expected to choose any three weeks to submit a written “brief” that provides a reaction to the readings for that week. Briefs are short analytic and reflective memos (2–3 pages, double-spaced, 12-point font) that examine the essential questions for that week referenced in the syllabus. The argument and use of content in the brief is completely up to the student; however, each brief should demonstrate an understanding of the readings as well as application to the students’ project with the partner organization or to future work. Briefs are due by midnight on the Monday before each class begins, and students will receive feedback from the teaching team by the end of that week.

Only requiring briefs some of the time accomplishes several goals: it gives students some flexibility in managing their workload, it allows them to focus more deeply on topics that most interest them, and it makes it more manageable for the teaching team in terms of giving feedback and applying the information. The teaching team then makes use of this information, as discussed in the section above. When inviting students to share something from their brief, Candice will often email students in advance to help them prepare for their contribution. She will also thread students’ insights from briefs into her comments, connecting student ideas to key course concepts.

Pluses and deltas: gathering student perspectives after a given class session | Kathy Boudett

“Pluses and deltas” is a simple and versatile vehicle for gathering student feedback at any time, often at the end of a class session. The key elements are soliciting student perspectives on what has gone well (pluses) and where there might be room for improvement (deltas, which comes from the Greek symbol for change) and then exploring how this information might be used to improve the course experience. Critical to making this practice work is dedicating time in class to share an overview of their suggestions and the resulting responses.

“I really want to teach amazing classes, and a key part of doing so is to gather formative feedback on an on-going basis to make sure I am meeting the needs of these particular students,” says Kathy. She finds that students give immensely helpful feedback and that, in doing so, they become more invested in the course and the classroom community. Her own research is focused on the power of continuous improvement, and this pluses and deltas technique is an effective way to apply that principle to her own practice.

There are two main ways to employ this technique: soliciting feedback together as a group and gathering feedback individually.

Soliciting feedback together: Kathy usually sets aside five to ten minutes at the end of a class session to do pluses and deltas as a group. If she has ten minutes, which is preferred, she tends to give students a minute to think individually and then one or two minutes to share with a partner. It is important to Kathy that everyone has a chance to share their perspective, even if just with a peer. She then solicits feedback from the group, while she or a teaching fellow scribes the comments. Kathy tries to have time for as many comments as possible, so she tends to simply thank each student for their contribution. But it is also important for Kathy to model a non-defensive stance to feedback, so she will often respond with curiosity and affirmation to the deltas.

(If Kathy only has five minutes for feedback, she will use a more specific prompt, such as: “Today we used a case study in the last 30 minutes as a vehicle for applying the new conceptual principles. I’d love some feedback on how that went for everyone.” She also will move more quickly to the whole-group discussion.)

She then meets with her teaching team outside of class to discuss how to adjust the next class in light of the feedback. If so, she will often report those changes at the start of the next class session, but on occasion she will just incorporate the suggestions without further discussion. Regardless of how she responds, Kathy is unequivocal that “students need to know that this feedback is taken seriously and is benefiting the classroom community.”

Soliciting feedback individually: In this version of the technique, Kathy has students fill out an online plus/delta survey during the last 5 minutes of class. The teaching team then compiles the data, creates a summary of the main areas of feedback, decides how to respond to the deltas, and prepares a short presentation for the next class session. In that presentation, the teaching team will share the summary data and discuss the implications for each of the deltas. It may mean altering some aspect of upcoming lessons, reteaching a concept that was not clear, engaging in an open conversation about a proposed change, or discussing why a valid piece of feedback will not result in a change in this iteration of the course.

View the discussion thread.

- Organization (6)

- Project (8)

- Teaching and Learning (4)

- Technology (4)

Blog posts by month

- February 2023 (1)

- November 2021 (1)

- January 2021 (2)

- October 2020 (2)

- March 2017 (1)

22 Feedback for manager examples and best practices that you should know

In the dynamic world of management, feedback isn't a one-way street. It's a multi-lane highway where managers navigate as much as their teams.

While we often focus on employees' performance reviews, it's time to flip the script and understand that managers need constructive feedback too. Surprisingly, a significant 44 % of managers have reported feeling unprepared for their roles.

Buckle up because we're about to embark on a journey through the art of giving feedback to managers . Let's explore 22 manager feedback examples and best practices that will help you empower your leaders while boosting team productivity!

What is feedback for managers?

Feedback for managers refers to the process of providing constructive input, information, and assessments to individuals in leadership roles within an organization. It serves as a valuable tool for their professional growth, helping them understand their strengths, weaknesses, and areas that require improvement.

Effective feedback enables managers to enhance their leadership skills, make informed decisions, and align their actions with organizational goals. It often includes insights from superiors, peers, subordinates, or even self-reflection.

Feedback for managers is pivotal in fostering continuous improvement, fostering a positive work environment , and achieving better overall performance within a team or organization.

Importance of giving feedback for managers

The importance of giving feedback for managers cannot be overstated. It serves several crucial purposes:

- Improvement: Feedback provides managers with insights into their performance, helping them identify areas where they excel and those that need development. It's a catalyst for growth and improvement.

- Enhanced leadership: Constructive feedback helps managers become more effective leaders . It allows them to adapt their management style, communicate better, and make informed decisions.

- Motivation: Positive feedback boosts morale and motivation , while constructive feedback, when delivered properly, can act as a catalyst for change and inspire managers to reach their potential.

- Accountability: Feedback holds managers accountable for their actions and decisions, promoting responsibility and a culture of transparency.

- Team performance: Effective managers are instrumental in team success. Feedback equips them with the tools to lead teams to higher performance levels, resulting in increased productivity and job satisfaction.

- Organizational alignment: Feedback helps managers align their goals and strategies with those of the organization, ensuring everyone is working towards the same objectives.

- Conflict resolution: Managers often deal with conflicts within their teams. Feedback provides insights into these conflicts and offers guidance on how to address and make sure the team is on the same page.

- Employee development: Managers play a vital role in employee development . Feedback enables them to mentor and guide their team members effectively.

- Retention: Managers who provide regular feedback create a more positive work environment, which can enhance employee retention and reduce turnover.

- Innovation: By offering honest feedback and actively listening to employees, managers can encourage a culture of innovation within their teams.

Feedback for managers is instrumental in their growth, leadership development, team performance, and overall organizational success. It is a two-way street where managers both receive and provide feedback, fostering a culture of continuous improvement and open communication .

What are some examples of positive feedback for managers?

Positive feedback for managers is crucial for reinforcing effective behaviors and boosting morale. Here are some examples of positive feedback:

- Recognition of leadership: "Your leadership during the project was outstanding. Your ability to inspire and guide the team ensured our success."

- Team appreciation: "The team is motivated and engaged, thanks to your positive influence. Your leadership has created a productive and harmonious work environment."

- Problem-solving skills: "Your ability to address challenges is commendable. Your quick thinking and strategic approach saved us from potential setbacks."

- Effective communication: "Your communication style is exceptional. You have a unique talent for conveying complex information clearly, which helps us all stay aligned."

- Openness to feedback: "Your willingness to accept feedback and adapt is admirable. It shows your commitment to personal and team improvement."

- Mentoring and development: "You excel at nurturing talent. Your dedication to the professional growth of your team is evident and appreciated."

- Innovation: "Your innovative thinking consistently brings fresh ideas to our projects. Your creativity keeps our team ahead of the curve."

- Adaptability: "Your flexibility in handling change is a valuable asset. You've shown the ability to adapt to new situations and inspire the team to do the same."

- Empathy and team morale: "Your consideration for team members' well-being boosts morale. Your empathy helps create a supportive work culture."

- Recognition of achievements: "Your role in our recent achievement hasn't gone unnoticed. You played a key part in our success."

- Client or stakeholder feedback: Sharing positive feedback from clients or stakeholders can be highly motivating for managers.

- Long-term vision: "Your vision for the department's long-term goals is inspiring. Your strategic planning is steering us toward success."

These examples of positive feedback acknowledge various aspects of a manager's role, from leadership and communication to innovation and personal development. Positive feedback reinforces the desired behaviors and encourages managers to continue their excellent work.

When to give feedback to your manager?

Giving feedback to your manager is an important aspect of fostering open communication and continuous improvement. Here are some key situations when you should provide feedback to your manager:

- Scheduled one-on-one meetings: Use regular one-on-one meetings as a designated time to discuss your thoughts and concerns. This ensures that you have your manager's full attention and creates a safe space for feedback.

- After significant achievements: When you or your team achieve a significant milestone or success, it's a great time to offer positive feedback to acknowledge your manager's leadership and support.

- In response to their request: If your manager explicitly asks for feedback, this is an ideal opportunity to share your thoughts honestly and constructively.

- When there's a problem: If you encounter issues or challenges related to your work, department, or team that you believe your manager should be aware of, it's essential to provide feedback promptly. This allows your manager to address and resolve problems efficiently.

- After completing projects: At the end of a project or task, it's valuable to reflect on the experience and share feedback on what worked well and what could be improved for future projects.

- For personal growth and development: If you believe that offering feedback can help your manager's personal and professional development, share it in a supportive and constructive manner.

- When there's consistency in behavior: If you notice recurring patterns of behavior, whether positive or negative, it's beneficial to communicate this to your manager. Consistent feedback can help them reinforce positive behaviors or address recurring issues.

- Amid positive or negative change: During times of organizational change, such as restructuring, expansion, or downsizing, feedback can provide valuable insights into how these changes are affecting the team and what can be done to navigate them effectively.

- To express gratitude: Don't hesitate to express your appreciation and gratitude to your manager when they have been supportive, and understanding, or when you've experienced positive leadership .

- With diplomacy and sensitivity: Always choose an appropriate time and place to give feedback. Be diplomatic, and empathetic, and use "I" statements to express your thoughts without sounding accusatory.

In all these situations, the key is to provide feedback constructively, focusing on the issue at hand rather than making it personal. Effective feedback helps foster a culture of continuous improvement and strengthens the working relationship between employees and their managers.

How to send feedback to managers in the first place?

Sending feedback to your manager for the first time can be intimidating, but it's a crucial skill. Here are five creative steps to help you provide feedback effectively:

Choose the right moment

Find an appropriate time when your manager is available and do not rush. It's essential to create a comfortable atmosphere for this conversation.

Frame your feedback positively

Start with a positive note. Express your appreciation for their leadership and mention what you admire about their management style. This sets the stage for constructive feedback.

Be specific and provide examples

Rather than making vague statements, use specific examples to illustrate your points. If you're discussing an issue, describe the situation, your observations, and the impact it had.

Offer solutions

Don't just point out problems; suggest potential solutions. This shows that you're not only identifying issues but also willing to collaborate to find ways to address them.

Focus on "I" statements

Use "I" statements to convey your feedback. For instance, say, "I noticed that," or "I felt that." This approach shifts the conversation from blaming to sharing your perspective.

Remember that the goal of giving feedback is to help both you and your manager improve and foster a more productive working relationship. Be open to receiving feedback in return and maintain a constructive and respectful tone throughout the conversation.

Manager feedback best practices to follow

Effective manager feedback is a fundamental aspect of a healthy working environment. Managers who receive feedback are better equipped to make necessary improvements and create a positive workplace culture.

Here are seven creative and unique best practices for providing feedback to managers:

Choose the right setting for feedback

Find an appropriate time and place to give feedback. A one-on-one meeting or a private, informal setting works best. It ensures privacy, minimizes distractions, and allows for open communication.

Adopt a constructive approach

When giving feedback, focus on being constructive. Start with what the manager is doing well and acknowledge their strengths and achievements. This sets a positive tone for the conversation.

Use the "SBI" model

SBI stands for Situation, Behavior, and Impact. When offering feedback, describe the specific situation, the observed behavior, and the impact it had. This model provides clarity and helps the manager understand the context.

Encourage self-assessment

Instead of just delivering feedback, encourage managers to self-assess their performance. Ask questions that prompt reflection, such as "What do you think went well in that situation?" or "How do you think your team perceived your actions?"

Offer ongoing feedback

Don't save feedback for annual reviews. Frequent, timely feedback is more valuable. Share both positive feedback when you witness great performance and constructive feedback when there's room for improvement.

Highlight the impact on the team

When discussing areas for improvement, emphasize how changes can positively affect the team and overall productivity . Managers are more likely to embrace feedback when they see the potential benefits for their team.

Set clear goals and expectations

Provide managers with clear, actionable goals and expectations. Ambiguity can lead to misunderstandings and unmet expectations. When managers know what is expected of them, they can work towards meeting those goals.

Additionally, it's essential to remember that giving feedback to managers is a two-way street. They should feel comfortable offering feedback to their teams and superiors as well. This fosters a culture of open communication , where everyone can learn from each other and grow professionally.

Feedback is a valuable tool in the workplace, and these best practices can help managers and employees alike benefit from more productive interactions. When feedback is provided thoughtfully, constructively, and consistently, it contributes to a culture of continuous improvement and growth .

Types of feedback for manager

Feedback for managers plays a crucial role in personal and professional development . It helps them understand their strengths and weaknesses, fine-tune their management style, and lead more effectively.

There are several types of feedback for managers, each serving a unique purpose in fostering growth and improvement. Here are the key types of feedback they can receive:

Performance feedback

Performance feedback focuses on a manager's daily responsibilities and their ability to meet goals and targets. This type of feedback assesses how well they are executing their role, making decisions, and handling tasks. Performance feedback may include discussions on their time management, delegation, and work quality.

Behavioral feedback

Behavioral feedback addresses a manager's interpersonal skills, communication style, and interactions with their team. It often involves aspects like empathy, active listening, conflict resolution, and how well they motivate and inspire their team. Behavioral feedback is valuable for improving team dynamics and creating a positive work environment.

Developmental feedback

Developmental feedback aims to help managers enhance their skills and knowledge to meet future challenges. It focuses on their career growth and skill development. Managers receiving developmental feedback can explore opportunities for training, workshops, or mentorship to expand their expertise and readiness for new roles.

360-degree feedback

360-degree feedback gathers input from various sources, including peers, subordinates, and superiors. This well-rounded approach provides a comprehensive view of a manager's performance, as it incorporates multiple perspectives. It can reveal insights into a manager's effectiveness from different angles and help identify strengths and areas for improvement.

Crisis or corrective feedback

Crisis or corrective feedback is essential when a manager's actions or decisions have negatively impacted the team or the organization. It should address the immediate issue at hand and propose corrective actions to mitigate future damage. It can be challenging to deliver but is crucial for accountability and learning from mistakes.

Motivational feedback

Motivational feedback aims to inspire and uplift managers. It acknowledges their accomplishments, expresses gratitude for their dedication, and motivates them to continue performing at a high level. It helps boost morale , increase engagement, and maintain a positive work atmosphere.

Goal-oriented feedback

Goal-oriented feedback centers around a manager's progress toward their goals and objectives. It measures how effectively they are steering their team towards achieving these targets. This type of feedback is particularly helpful in ensuring alignment with the organization's strategic objectives.

Constructive feedback

Constructive feedback is crucial for identifying areas of improvement while maintaining a positive and encouraging tone. It should focus on specific behaviors or actions that need adjustment and provide actionable recommendations. The goal is to help the manager grow without demoralizing them.

Positive feedback

Positive feedback recognizes and appreciates a manager's achievements, strong leadership, and contributions to the organization. It fosters a sense of accomplishment, motivates the manager to excel further, and strengthens their commitment to the team and company.

Coaching feedback

Coaching feedback is a form of ongoing support that helps managers enhance their skills and reach their potential. It involves regular one-on-one sessions with a coach or mentor who provides guidance, advice, and developmental suggestions. Coaching feedback can be tailored to the manager's unique needs and aspirations.

Culture feedback

Culture feedback assesses how well a manager aligns with the organization's culture, values, and mission. It helps in maintaining a consistent culture across the organization and can involve discussions on integrity, ethics, and inclusivity.

Employee feedback

Feedback from team members can be invaluable for managers. It provides insights into how they are perceived by their subordinates and helps them adjust their approach based on the team's needs and preferences. Employee feedback i.e. upward feedback may also include insights into work-life balance , workload, and support required from the manager.

Customer feedback

In roles where managers have direct interactions with customers, feedback from clients can be a valuable source of insights. This type of feedback can provide managers with a customer-centric perspective, helping them improve relationships and customer satisfaction.

Feedback for managers is a multifaceted tool that helps them grow, excel in their roles, and positively influence their teams and organizations. Each type of feedback serves a unique purpose , and a combination of these feedback types can create a well-rounded approach to personal and professional development.

Effective feedback is a cornerstone of leadership development, enabling managers to adapt, learn, and continuously improve their skills.

Importance of manager feedback surveys

Manager feedback surveys are valuable tools for organizations seeking to enhance leadership, productivity, and employee satisfaction. These surveys play a pivotal role in creating a feedback-rich culture within an organization, ensuring that managers are effective and aligned with the company's goals.

Here's an exploration of the importance of manager feedback surveys:

Improvement of managerial skills

Manager feedback surveys provide managers with insights into their strengths and areas for improvement. By identifying these areas, managers can focus on enhancing their leadership skills and becoming more effective in their roles. This leads to better decision-making, increased team engagement , and improved performance.

Enhanced team productivity

Effective managers are instrumental in driving entire team productivity. When employees provide critical feedback about their managers , it can uncover pain points, areas of friction, and team dynamics that need attention. Managers can use this information to make the necessary adjustments, leading to higher team morale and productivity.

Employee engagement

Employee engagement is closely tied to effective leadership. Managers who receive feedback and act on it are more likely to create an engaging work environment. Engaged employees tend to be more committed, loyal, and motivated, resulting in improved overall performance and lower turnover rates.

Strengthening leadership competencies

Manager feedback surveys help organizations identify which leadership competencies need strengthening. This data enables targeted training and development programs , which can help managers gain a deeper understanding of their roles and responsibilities.

Alignment with organizational goals

Managers play a pivotal role in aligning their teams with the organization's goals. When managers receive feedback from their team members, it can highlight areas where alignment is lacking. This enables managers to make the necessary adjustments to ensure that everyone is working towards a common objective.

Recognition of high performers

Manager feedback surveys can recognize high-performing managers and their contributions to the organization. This recognition not only motivates the manager but also serves as an example for other team members, fostering a culture of excellence.

Early detection of issues

Timely feedback through surveys allows organizations to detect issues or conflicts within teams before they escalate. This proactive approach enables managers to address problems promptly, preventing potential disruptions and fostering a more harmonious work environment.

Career growth opportunities

Manager feedback surveys can help identify high-potential managers who exhibit strong leadership qualities. Recognizing and nurturing these individuals can lead to career growth and succession planning within the organization.

Customized feedback

Manager feedback surveys can be customized to suit the organization's specific needs and the competencies it values most. This tailored approach ensures that feedback is relevant and actionable.

Inclusivity and diversity

Feedback surveys can be designed to measure a manager's effectiveness in promoting inclusivity and diversity within their teams. This is vital in today's workplace, as organizations increasingly focus on creating diverse and equitable work environments.

Data-driven decision-making

Data from manager feedback surveys can be analyzed to identify trends, strengths, and areas for improvement across the management team. This data-driven approach allows organizations to make informed decisions about managerial development and succession planning.

Employee well-being

Managers significantly impact employee well-being. Through feedback surveys, organizations can ensure that their managers are providing the necessary support, guidance, and work-life balance for their teams.

Accountability and transparency

Manager feedback surveys promote accountability at all levels of the organization. Managers who receive feedback are held accountable for their actions, and this transparency fosters trust among team members.

22 Positive and negative feedback examples for managers to give in the workplace

Feedback is a crucial element of effective management. Managers must provide feedback that encourages growth and development while also addressing issues constructively.

Here are 22 examples of both positive and negative feedback that managers can give in the workplace:

Positive Feedback:

- Positive performance acknowledgment : "I appreciate your outstanding performance on the project. Your dedication and attention to detail have greatly contributed to our success."

- Team appreciation : "Your teamwork skills are impressive. You consistently support your colleagues and contribute to a positive team environment."

- Leadership recognition : "Your leadership in the recent client presentation was outstanding. You maintained control and guided the team with confidence."

- Innovative contributions : "Your innovative ideas for process improvement have significantly enhanced our workflow. Keep up the creativity."

- Adaptability praise : "Your ability to adapt to changing circumstances and manage stress is commendable. It sets a great example for the team."

- Problem-solving skills : "Your approach to problem-solving is excellent. You've shown an exceptional ability to resolve complex issues efficiently."

- Customer satisfaction : "Our customers often praise your excellent service. Your commitment to customer satisfaction is exemplary."

- Meeting deadlines : "Your consistent ability to meet tight deadlines is remarkable. It's a valuable asset to our team."

- Quality assurance : "Your attention to quality assurance ensures our products meet the highest standards. Your dedication is appreciated."

- Communication skills : "Your communication skills are exceptional. You explain complex ideas clearly, which helps our team work more cohesively."

- Initiative and proactiveness : "I noticed your initiative in identifying areas for improvement. Your proactive approach is admirable."

Negative Feedback:

- Constructive critique : "While your ideas are strong, sometimes they can come across as dominating discussions. Try to involve others more."

- Incomplete work addressed : "I've noticed that some of your recent reports have had incomplete sections. Let's ensure all aspects are covered."

- Tardiness concern : "Lately, you've been arriving late for meetings. Punctuality is essential, and I'd like to see improvement in this area."

- Feedback about micromanagement : "I've received feedback from the team about micromanagement. Trust your team more to handle their tasks."

- Team collaboration feedback : "You have the knowledge; now let's work on your teamwork skills. Collaborating more effectively is key."

- Communication improvement : "Your emails sometimes lack clarity, leading to misunderstandings. Take more time to compose effective messages."

- Expectation clarification : "It's crucial to have clearly defined expectations. Let's work on setting more specific goals for your projects."

- Handling stress feedback : "Managing stress is challenging, but it's vital to avoid outbursts at work. Consider stress management techniques."

- Conflict resolution discussion : "Handling conflicts constructively is essential. Avoiding confrontations and working on conflict resolution is key."

- Time management concern : "I've noticed that your time management could be more efficient. Prioritize tasks and minimize distractions."

Remember that when delivering negative feedback, it's essential to do so constructively, focusing on areas for improvement rather than criticism. Positive feedback should be specific and acknowledge accomplishments. Ultimately, both positive and negative feedback should contribute to an employee's growth and development.

feedback is the cornerstone of productive workplace relationships and continuous improvement. Managers play a pivotal role in fostering growth and development within their teams.

By providing constructive feedback that acknowledges achievements and addresses areas for improvement, they contribute to a healthier work environment and the professional development of their employees.

Santhosh is a Jr. Product Marketer with 2+ years of experience. He loves to travel solo (though he doesn’t label them as vacations, they are) to explore, meet people, and learn new stories.

You might also like

Effective employee engagement leadership to enhance your workplace in 2024.

Do you think your company needs more leadership initiatives to improve employee engagement? Read the article to see how employee engagement leadership can significantly enhance workplace communication, development, sense of belonging, and objectives through employee feedback.

33 Top one on one questions that are a must-ask in 2023

One-on-one meetings, also known as individual meetings, are dedicated conversations between a manager or team leader and individual team members. They provide a private and focused space for discussing various topics, addressing concerns, giving feedback, and fostering a good working relationship.

Book a free, no-obligation product demo call with our experts.

Business Email is a required field*

Too many attempts, please try again later!

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

16 constructive feedback examples — and tips for how to use them

Understand Yourself Better:

Big 5 Personality Test

Giving constructive feedback is nerve-wracking for many people. But feedback is also necessary for thriving in the workplace.

It helps people flex and grow into new skills, capabilities, and roles. It creates more positive and productive relationships between employees. And it helps to reach goals and drive business value.

But feedback is a two-way street. More often than not, it’s likely every employee will have to give constructive feedback in their careers. That’s why it’s helpful to have constructive feedback examples to leverage for the right situation.

We know employees want feedback. But one study found that people want feedback if they’re on the receiving end . In fact, in every case, participants rated their desire for feedback higher as the receiver. While the fear of feedback is very real, it’s important to not shy away from constructive feedback opportunities. After all, it could be the difference between a flailing and thriving team.

If you’re trying to overcome your fear of providing feedback, we’ve compiled a list of 16 constructive feedback examples for you to use. We’ll also share some best practices on how to give effective feedback .

What is constructive feedback?

When you hear the word feedback, what’s the first thing that comes to mind? What feelings do you have associated with feedback? Oftentimes, feedback conversations are anxiety-ridden because it’s assumed to be negative feedback. Unfortunately, feedback has this binary stigma, it’s either good or bad.

But in reality, there are plenty of types of feedback leveraged in both personal and professional relationships. They don’t all fall into one camp or the other. And each type of feedback is serving a purpose to ultimately better an individual, team, or work environment.

For example, positive feedback can be used to reinforce desired behaviors or big accomplishments. Real-time feedback is reserved for those “in the moment” situations. Like if I’ve made a mistake or a typo in a blog, I’d want my teammates to give me real-time feedback .

However, constructive feedback is its own ball game.

What is constructive feedback?

Constructive feedback is a supportive way to improve areas of opportunity for an individual person, team, relationship, or environment. In many ways, constructive feedback is a combination of constructive criticism paired with coaching skills.

16 constructive feedback examples to use

To truly invest in building a feedback culture , your employees need to feel comfortable giving feedback. After all, organizations are people, which means we’re all human. We make mistakes but we’re all capable of growth and development. And most importantly, everyone everywhere should be able to live with more purpose, clarity, and passion.

But we won’t unlock everyone’s full potential unless your people are comfortable giving feedback. Some employee feedback might be easier to give than others, like ways to improve a presentation.

But sometimes, constructive feedback can be tricky, like managing conflict between team members or addressing negative behavior. As any leader will tell you, it’s critical to address negative behaviors and redirect them to positive outcomes. Letting toxic behavior go unchecked can lead to issues with employee engagement , company culture, and overall, your business’s bottom line.

Regardless of where on the feedback spectrum your organization falls, having concrete examples will help set up your people for success. Let’s talk through some examples of constructive feedback. For any of these themes, it’s always good to have specific examples handy to help reinforce the feedback you’re giving. We’ll also give some sample scenarios of when these phrases might be most impactful and appropriate.

Constructive feedback examples about communication skills

An employee speaks over others and interrupts in team meetings.

“I’ve noticed you can cut off team members or interrupt others. You share plenty of good ideas and do good work. To share some communication feedback , I’d love to see how you can support others in voicing their own ideas in our team meetings.”

An employee who doesn’t speak up or share ideas in team meetings.

“I’ve noticed that you don’t often share ideas in big meetings. But in our one-on-one meetings , you come up with plenty of meaningful and creative ideas to help solve problems. What can I do to help make you more comfortable speaking up in front of the team?”

An employee who is brutally honest and blunt.

“Last week, I noticed you told a teammate that their work wasn’t useful to you. It might be true that their work isn’t contributing to your work, but there’s other work being spread across the team that will help us reach our organizational goals. I’d love to work with you on ways to improve your communication skills to help build your feedback skills, too. Would you be interested in pursuing some professional development opportunities?”

An employee who has trouble building rapport because of poor communication skills in customer and prospect meetings.

“I’ve noticed you dive right into the presentation with our customer and prospect meetings. To build a relationship and rapport, it’s good to make sure we’re getting to know everyone as people. Why don’t you try learning more about their work, priorities, and life outside of the office in our next meeting?”

Constructive feedback examples about collaboration

An employee who doesn’t hold to their commitments on group or team projects.

“I noticed I asked you for a deliverable on this key project by the end of last week. I still haven’t received this deliverable and wanted to follow up. If a deadline doesn’t work well with your bandwidth, would you be able to check in with me? I’d love to get a good idea of what you can commit to without overloading your workload.”

An employee who likes to gatekeep or protect their work, which hurts productivity and teamwork .

“Our teams have been working together on this cross-functional project for a couple of months. But yesterday, we learned that your team came across a roadblock last month that hasn’t been resolved. I’d love to be a partner to you if you hit any issues in reaching our goals. Would you be willing to share your project plan or help provide some more visibility into your team’s work? I think it would help us with problem-solving and preventing problems down the line.”

An employee who dominates a cross-functional project and doesn’t often accept new ways of doing things.

“I’ve noticed that two team members have voiced ideas that you have shut down. In the spirit of giving honest feedback, it feels like ideas or new solutions to problems aren’t welcome. Is there a way we could explore some of these ideas? I think it would help to show that we’re team players and want to encourage everyone’s contributions to this project.”

Constructive feedback examples about time management

An employee who is always late to morning meetings or one-on-ones.

“I’ve noticed that you’re often late to our morning meetings with the rest of the team. Sometimes, you’re late to our one-on-ones, too. Is there a way I can help you with building better time management skills ? Sometimes, the tardiness can come off like you don’t care about the meeting or the person you’re meeting with, which I know you don’t mean.”

A direct report who struggles to meet deadlines.

“Thanks for letting me know you’re running behind schedule and need an extension. I’ve noticed this is the third time you’ve asked for an extension in the past two weeks. In our next one-on-one, can you come up with a list of projects and the amount of time that you’re spending on each project? I wonder if we can see how you’re managing your time and identify efficiencies.”

An employee who continuously misses team meetings.

“I’ve noticed you haven’t been present at the last few team meetings. I wanted to check in to see how things are going. What do you have on your plate right now? I’m concerned you’re missing critical information that can help you in your role and your career.”

Constructive feedback examples about boundaries

A manager who expects the entire team to work on weekends.

“I’ve noticed you send us emails and project plans over the weekends. I put in a lot of hard work during the week, and won’t be able to answer your emails until the work week starts again. It’s important that I maintain my work-life balance to be able to perform my best.”

An employee who delegates work to other team members.

“I’ve noticed you’ve delegated some aspects of this project that fall into your scope of work. I have a full plate with my responsibilities in XYZ right now. But if you need assistance, it might be worth bringing up your workload to our manager.”

A direct report who is stressed about employee performance but is at risk of burning out.

“I know we have performance reviews coming up and I’ve noticed an increase in working hours for you. I hope you know that I recognize your work ethic but it’s important that you prioritize your work-life balance, too. We don’t want you to burn out.”

Constructive feedback examples about managing

A leader who is struggling with team members working together well in group settings.

“I’ve noticed your team’s scores on our employee engagement surveys. It seems like they don’t collaborate well or work well in group settings, given their feedback. Let’s work on building some leadership skills to help build trust within your team.”

A leader who is struggling to engage their remote team.

“In my last skip-levels with your team, I heard some feedback about the lack of connections . It sounds like some of your team members feel isolated, especially in this remote environment. Let’s work on ways we can put some virtual team-building activities together.”

A leader who is micromanaging , damaging employee morale.

“In the last employee engagement pulse survey, I took a look at the leadership feedback. It sounds like some of your employees feel that you micromanage them, which can damage trust and employee engagement. In our next one-on-one, let’s talk through some projects that you can step back from and delegate to one of your direct reports. We want to make sure employees on your team feel ownership and autonomy over their work.”

8 tips for providing constructive feedback

Asking for and receiving feedback isn’t an easy task.

But as we know, more people would prefer to receive feedback than give it. If giving constructive feedback feels daunting, we’ve rounded up eight tips to help ease your nerves. These best practices can help make sure you’re nailing your feedback delivery for optimal results, too.

Be clear and direct (without being brutally honest). Make sure you’re clear, concise, and direct. Dancing around the topic isn’t helpful for you or the person you’re giving feedback to.

Provide specific examples. Get really specific and cite recent examples. If you’re vague and high-level, the employee might not connect feedback with their actions.

Set goals for the behavior you’d like to see changed. If there’s a behavior that’s consistent, try setting a goal with your employee. For example, let’s say a team member dominates the conversation in team meetings. Could you set a goal for how many times they encourage other team members to speak and share their ideas?

Give time and space for clarifying questions. Constructive feedback can be hard to hear. It can also take some time to process. Make sure you give the person the time and space for questions and follow-up.

Know when to give feedback in person versus written communication. Some constructive feedback simply shouldn’t be put in an email or a Slack message. Know the right communication forum to deliver your feedback.

Check-in. Make an intentional effort to check in with the person on how they’re doing in the respective area of feedback. For example, let’s say you’ve given a teammate feedback on their presentation skills . Follow up on how they’ve invested in building their public speaking skills . Ask if you can help them practice before a big meeting or presentation.

Ask for feedback in return. Feedback can feel hierarchical and top-down sometimes. Make sure that you open the door to gather feedback in return from your employees.

Start giving effective constructive feedback

Meaningful feedback can be the difference between a flailing and thriving team. To create a feedback culture in your organization, constructive feedback is a necessary ingredient.

Think about the role of coaching to help build feedback muscles with your employees. With access to virtual coaching , you can make sure your employees are set up for success. BetterUp can help your workforce reach its full potential.

Madeline Miles

Madeline is a writer, communicator, and storyteller who is passionate about using words to help drive positive change. She holds a bachelor's in English Creative Writing and Communication Studies and lives in Denver, Colorado. In her spare time, she's usually somewhere outside (preferably in the mountains) — and enjoys poetry and fiction.

5 types of feedback that make a difference (and how to use them)

Are you receptive to feedback follow this step-by-step guide, should you use the feedback sandwich 7 pros and cons, how to give constructive feedback as a manager, handle feedback like a boss and make it work for you, why coworker feedback is so important and 5 ways to give it, how to give and take constructive criticism, how to get feedback from your employees, how to give positive comments to your boss, similar articles, 17 positive feedback examples to develop a winning team, how to give negative feedback to a manager, with examples, trying to find your calling these 16 tips will get you started, how to embrace constructive conflict, how to empower your team through feedback, 25 performance review questions (and how to use them), how to give kudos at work. try these 5 examples to show appreciation, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care™

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

Vantage Rewards

A people first rewards and recognition platform to elevate company culture.

Vantage Pulse

An eNPS-based pulse survey tool that empowers HRs to manage the workforce better.

Vantage Perks

A corporate discounts platform with a plethora of exclusive deals and offers from global brands.

Vantage Fit

A gamified corporate wellness platform that keeps the workforce ‘Fit’ and rewards them for it.

Vantage Gifting

An all-in-one corporate gifting solution to delight your employees on every occasion & make them feel valued.

AIR e Consultation

AIR e program consultation to design and implement an authentic and impactful rewards and recognition program.

Vantage Onboarding

Customizable and budget-friendly joining kits to create a sense of belonging and make new hires feel at home

Integration

Seamless integration with your existing HCM/HRIS platform and chat tools.

Product Updates

Check out all the new stuff we are adding to our products to constantly improve them for better experience.

Blog

Influencers Podcast

Guides & eBooks

Webinars

Industry Reports

AIR e Framework

Vantage Rewards

Vantage Perks

Vantage Pulse

Vantage Fit

Vantage Gifting

An all-in-one corporate gifting solution to delight your employees on every occasion & make them feel valued.

AIR e Consultation

Vantage Onboarding

Blogue

8 Examples of Constructive Feedback With Sample Scenarios

Being a manager in the 21st century is not at all a child's play. The work culture now demands the managers to lead the workforce by adopting multiple roles as a motivator, a mentor , and a leader all at the same time. And one of the most important aspects of these roles is the ability and the will to deliver constructive feedback to the employees.

Feedbacks are an integral part of ensuring an efficient work culture. Frequently giving positive feedback not only impacts employee morale but also acts as a guide for them. Further, it sets the performance standard expected from the teams.

However, delivering constructive feedback is not as smooth as a hot knife through butter. There's a fragile line that separates feedback from criticism, and this is where most managers mess up.

The tone of delivering the feedback and the words you use may sometimes make your feedback sound more like a criticism which negatively affects the professional relationship . Furthermore, the majority of feedback is gathered through surveys, such as pulse surveys or one question surveys , making it critical to make the questions truly meaningful.

That's why to help you deliver the best constructive feedback to your employees, I present to you a few feedback samples with their relating scenarios.

But before beginning with the same, here are some of the essential points that you need to keep in mind while conveying constructive feedback to your employees.

Steps to Frame a Constructive Feedback

1. state your observation.

Feedbacks are totally based on your observations as a professional. Deciphering these observations based on your managerial skills will further allow you to give precise and well-feedback. Also, when you state your observations clearly to the receiver, it uplifts your persona as a mentor whom everyone can look up to. Thus, building confidence and camaraderie with your employees.

2. Pinpoint the Areas for Betterment

The thin line that lies between criticism and constructive feedback is defined with this very point. The main motive behind conveying constructive feedback is to help others realize the scope of betterment complemented with a bit of advice or a suggestion.

Read more: 5 Useful Tips On How To Give Constructive Criticism

3. Keeping Up an Appreciative Tone