Health Is Wealth Essay for Students and Children

500+ words health is wealth essay.

Growing up you might have heard the term ‘Health is Wealth’, but its essential meaning is still not clear to most people. Generally, people confuse good health with being free of any kind of illness. While it may be part of the case, it is not entirely what good health is all about. In other words, to lead a healthy life , a person must be fit and fine both physically and mentally. For instance, if you are constantly eating junk food yet you do not have any disease, it does not make you healthy. You are not consuming healthy food which naturally means you are not healthy, just surviving. Therefore, to actually live and not merely survive, you need to have the basic essentials that make up for a healthy lifestyle.

Introduction

Life is about striking a balance between certain fundamental parts of life. Health is one of these aspects. We value health in the same way that we value time once we have lost it. We cannot rewind time, but the good news is that we can regain health with some effort. A person in good physical and mental health may appreciate the world to the fullest and meet life’s problems with ease and comfort. Health is riches implies that health is a priceless asset rather than money or ownership of material possessions. There is no point in having money if you don’t have good health.

Key Elements Of A Healthy Lifestyle

If you wish to acquire a healthy lifestyle, you will certainly have to make some changes in your life. Maintaining a healthy lifestyle demands consistent habits and disciplined life. There are various good habits that you can adopt like exercising regularly which will maintain your physical fitness. It also affects your mental health as when your appearance enhances, your confidence will automatically get boosted.

To live a healthy life, one must make some lifestyle modifications. These modifications can include changes to your food habits, sleeping routines, and lifestyle. You should eat a well-balanced, nutrient-dense diet for your physical wellness.

Further, it will prevent obesity and help you burn out extra fat from your body. After that, a balanced diet is of great importance. When you intake appropriate amounts of nutrition, vitamins, proteins, calories and more, your immune system will strengthen. This will, in turn, help you fight off diseases powerfully resulting in a disease-free life.

Above all, cleanliness plays a significant role in maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Your balanced diet and regular exercise will be completely useless if you live in an unhealthy environment. One must always maintain cleanliness in their surroundings so as to avoid the risk of catching communicable diseases.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Benefits Of A Healthy Lifestyle

As it is clear by now, good health is a luxury which everyone wants but some of them cannot afford. This point itself states the importance of a healthy lifestyle. When a person leads a healthy lifestyle, he/she will be free from the tension of seeking medical attention every now and then.

On the contrary, if you have poor health, you will usually spend your time in a hospital and the bills will take away your mental peace. Therefore, a healthy lifestyle means you will be able to enjoy your life freely. Similarly, when you have a relaxed mind at all times, you will be able to keep your loved ones happy. A healthy individual is more likely to fulfil all of his goals because he can easily focus on them and has the energy to complete them. This is why the proverb “Health is Wealth” carries so much weight.

A socially healthy individual is one who is able to interact effectively and readily connect with others. Without his ego, he can easily blend with the person in front of him, exuding a nice feeling and energy.

Every human being should participate in sports and activities to get away from the monotony of daily life. It is because sports and games assist in instilling a sense of oneness in people, build leadership skills, and make a person absolutely disciplined.

Moreover, a healthy lifestyle will push you to do better in life and motivate you to achieve higher targets. It usually happens that people who are extremely wealthy in terms of money often lack good health. This just proves that all the riches in the world will do you no good if there is an absence of a healthy lifestyle.

In short, healthy life is the highest blessing that must not be taken for granted. It is truly the source of all happiness. Money may buy you all the luxuries in the world but it cannot buy you good health. You are solely responsible for that, so for your well-being and happiness, it is better to switch to a healthy lifestyle.

Good Health for Children

Childhood is an ideal period to inculcate healthy behaviours in children. Children’s health is determined by a variety of factors, including diet, hydration, sleep schedule, hygiene, family time, doctor visits, and physical exercise. Following are a few key points and health tips that parents should remember for their children:

- Never allow your children to get by without nutritious food. Fruits and vegetables are essential.

- Breakfast is the most important meal of the day, therefore teach them to frequently wash their hands and feet.

- Sleep is essential for your child.

- Make it a habit for them to drink plenty of water.

- Encourage physical activity and sports.

- Allow them enough time to sleep.

- It is critical to visit the doctor on a regular basis for checks.

Parents frequently focus solely on their children’s physical requirements. They dress up their children’s wounds and injuries and provide them with good food. However, they frequently fail to detect their child’s deteriorating mental health. This is because they do not believe that mental health is important.

Few Lines on Health is Wealth Essay for Students

- A state of physical, mental, emotional, and social well-being is referred to as health. And all of this is linked to one another.

- Stress, worry, and tension are the leading causes of illness and disease in today’s world. When these three factors are present for an extended period of time, they can result in a variety of mental difficulties, which can lead to physical and emotional illnesses. As a result, taking care of your own health is critical.

- Unhealthy food or contaminated water, packed and processed food and beverages, unsanitary living conditions, not getting enough sleep, and a lack of physical activity are some of the other primary causes of health deterioration.

- A well-balanced diet combined with adequate exercise and hygienic habits, as well as a clean environment, can enhance immunity and equip a person to fight most diseases.

- A healthy body and mind are capable of achieving things that a sick body and mind are incapable of achieving, including happiness.

- It is also vital to seek medical and professional assistance when necessary because health is our most valuable asset.

- Activities such as playing an instrument, playing games, or reading provide the brain with the required exercise it requires to improve health.

Maintaining healthy behaviours improves one’s outlook on life and contributes to longevity as well as success.

Frequently Asked Questions

Question 1: What are the basic essentials of a healthy life? Answer: A healthy life requires regular exercise, a balanced diet, a clean environment, and good habits.

Question 2: How can a healthy life be beneficial? Answer: A healthy lifestyle can benefit you in various ways. You will lead a happier life free from any type of disease. Moreover, it will also enhance your state of mind.

Question 3: When is World Health Day celebrated?

Answer: Since 1950, World Health Day has been observed on the 7th of April by the World Health Organization (WHO), after a decision made at the first Health Assembly in 1948. It is observed to raise awareness about people’s overall health and well-being around the world.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Childhood Obesity — Importance Of Good Health

Importance of Good Health

- Categories: Childhood Obesity

About this sample

Words: 649 |

Published: Mar 14, 2024

Words: 649 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1163 words

4 pages / 1719 words

5 pages / 2053 words

4 pages / 1991 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Childhood Obesity

Childhood obesity is a growing epidemic that has raised significant concerns among health professionals, parents, and policymakers alike. With the rise of sedentary lifestyles, increased consumption of processed foods, and lack [...]

Buzzell, L. (2019, August 13). Benefits of a Healthy Lifestyle. Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.healthline.com/health/healthy-eating-on-a-budget#1.-Plan-meals-and-shop-for-groceries-in-advance

With obesity rates on the rise, and student MVPA time at an all time low, it is important, now more than ever, to provide students with tools and creative opportunities for a healthy and active lifestyle. A school following a [...]

In conclusion, while Zinczenko's analysis in "Don't Blame the Eater" offers valuable insights into the rise of childhood obesity and the role of the fast-food industry, it is necessary to critically examine his claims. While [...]

Throughout recent years obesity has been a very important topic in our society. It has continued to rise at high rates especially among children. This causes us to ask what are the causes of childhood obesity? There are many [...]

It is well known today that the obesity epidemic is claiming more and more victims each day. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention writes “that nearly 1 in 5 school age children and young people (6 to 19 years) in the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Health is Wealth Essay

Importance of Working Towards Good Health

Health is God’s gift to us. Health refers to the physical and mental state of a human being. To stay healthy is not an option but a necessity to live a happy life. The basic laws of good health are related to the food we eat, the amount of physical exercise we do, our cleanliness, rest, and relaxation. A healthy person is normally more confident, self-assured, sociable, and energetic. A healthy person views things calmly, and without prejudice.

Introduction

“The Dalai Lama, when asked what surprised him most about humanity, answered "Man! Because he sacrifices his health to make money. Then he sacrifices money to recuperate his health. And then he is so anxious about the future that he does not enjoy the present; the result being that he does not live in the present or the future; he lives as if he is never going to die, and then dies having never really lived.” This signifies that individuals don’t prioritise their mental health to earn money. Some even work 24 hours a day or seven days a week.

However, you have the option to remain balanced. So, balance work and fitness daily. Always strive to keep a cheerful as well as a concentrated routine. It is necessary to plan ahead of time. In any case, one must maintain a good mental, bodily, and emotional state, and no professional or counsellor can assist you unless you desire to live. The will to live in the moment and make the most of it awakens the ideal strength within you, and you are the only one who can never let yourself fall apart.

Importance of Maintaining Health

We live in a super-fast age. The Internet has shrunk the world dramatically and people are connected 24x7. Multitasking is the order of the day, as we struggle to fulfill our responsibilities for everyone in life. In this fight, we often forget to spare time for ourselves. The stress levels continue to build up until one day a major collapse may make us realize that in all this hectic activity, we have forgotten to take care of one important thing – our health.

As we spend days shuttling between hospital and home, putting our body through one test after another, trying to find out what has gone wrong, we are forced to remember that ‘Health is indeed Wealth’.

In earlier days, life was very simple. People worked for a stipulated time, often walked everywhere, ate more homemade food, did household chores, and enjoyed a healthy balance in life.

Now people have cars and bikes to commute, so they walk less. With the demand for more working hours, people are awake till late at night and indulge in more junk food than home-cooked food. Modern equipment at home has reduced the labour work and increased dependency on this equipment. People don’t have enough time to exercise or even get enough sunlight. Nowadays people are living very unhealthy lifestyles.

Unhealthy living conditions have increased the contraction of people to various diseases like obesity, diabetes, heart attacks, hypertension, etc. This has alarming implications in the near future. So it is very important to focus on our health as much as we focus on our work. Moderation in food habits, daily exercise, and balanced work-life can surely make a big difference to our health and body. When a person stays mentally and physically fit, his actions and decisions are more practical and logical and hence he is more successful in life. Furthermore, good health has a direct impact on our personality.

It's crucial to consider how much self-control you have to keep a healthy lifestyle. Research reveals that changing one's behaviour and daily patterns are quite tough. According to the data, whether a person has a habit of smoking, drinking alcohol, doing drugs, or any other substance, it is extremely difficult to quit. A study found that 80% of smokers who tried to quit failed, with only 46% succeeding.

Importance of Good Health

A healthy body has all the major components that help in the proper functioning of the body. The essential component is the state of physical health. Your life term extends when you maintain good physical fitness. If you are committed to exercising with a sensible diet, then you can develop a sense of well-being and can even prevent yourself from chronic illness, disability, and premature death.

Some of the benefits of increased physical activity are as follows.

It Improves Our Health

1. It increases the efficiency of the heart and lungs.

2. A good walk can reduce cholesterol levels.

3. Good exercise increases muscle strength.

4. It reduces blood pressure.

5. It reduces the risk of major illnesses such as diabetes and heart disease.

Improved Sense of Well-being

1. It helps in developing more energy.

2. It reduces stress levels.

3. Quality of sleep improves.

4. It helps in developing the ability to cope with stress.

5. It increases mental sharpness.

Improved Appearances

1. Weight loss contributes to a good physique.

2. Toned muscles generate more energy.

3. Improved posture enhances our appearance.

Enhanced Social Life

1. It improves self-image

2. It increases opportunities to make new friends.

3. It increases opportunities to share an activity with friends or family members.

Increased Stamina

1. Increased productivity.

2. Increased physical capabilities.

3. Less frequent injuries.

4. Improved immunity to minor illnesses.

Along with physical fitness, a good mental state is also essential for good health. Mental health means the emotional and psychological state of an individual. The best way to maintain good mental health is by staying positive and meditating.

However, unlike a machine, the body needs rest at regular intervals. A minimum of six to seven hours of sleep is necessary for the body to function optimally. Drinking plenty of water and a balanced diet is also very important for your body. If you violate the basic laws of good health, like working late hours, ignoring physical exercise, eating junk food, it will lead to various ailments like hypertension, heart attacks, and other deadly diseases.

What is National Health Day?

Every year on April 7th, World Health Day is celebrated. The World Health Organization (WHO) hosted the inaugural World Health Day on April 7, 1950, to draw the entire world’s attention to global health.

Every year, the World Health Organization (WHO) comes up with a new theme for public awareness, such as "Support Nurses and Midwives" in 2020. This supports the situation of COVID-19, where healthcare workers are saving lives day and night without worrying about their health.

The WHO also operates a global health promotion initiative to align equality so that individuals can take control of their lives, "every life matters," and consider their fitness. The government promotes numerous health policies, including food security, workplace quality, and health literacy, in schools, colleges, workplaces, and various community activities.

Good Health for Children

Children need to maintain good physical and mental health. With an increase in the pressure of studies and over-indulgence in modern gadgets, children are losing the most precious thing, which is health. These days, they barely play in the playgrounds, they are more inclined towards junk food and spend more time on the screen. These unhealthy activities are slowly sabotaging their health. Parents should concentrate on the physical and mental health of their children, and inculcate good habits for maintaining a healthy lifestyle from a tender age.

Cleanliness also has a major role to play in maintaining good health. Taking a bath every day, washing hands before eating meals, brushing twice a day, changing clothes regularly, etc. are important habits to maintain good health.

Society is witnessing gloomy faces as a result of children and their parents' excessive usage of a computer, mobile phone, and the Internet. They are constantly using these technological items, oblivious to the fact that they may harm their health. Teenagers are frequently discovered engrossed in their electronic devices, resulting in mishaps.

The usage of electronic devices frequently results in anxiety and hostility. Excessive usage of these products has been linked to cancer, vision loss, weight gain, and insomnia.

Emotional development is another crucial component that should not be disregarded because it determines whether or not a person is healthy. An emotionally healthy person should have a solid sense of logic, realisation, and a realistic outlook.

Conclusion

Health is Wealth because if we are not healthy then all our wealth, fame and power can bring no enjoyment. Keeping fit and healthy is indeed not an option but a necessity.

FAQs on Health is Wealth Essay

1. Why is Health Considered as Wealth?

Health is wealth because it is one of God’s most precious gift to human beings. Good health refers to a balanced and healthy physical and mental state of an individual. If any individual is not healthy, wealth, fame, and power can bring no enjoyment. So health has more value than materialistic things.

2. When is World Health Day Celebrated?

World Health Day is celebrated on 7 th April to raise awareness about health and fitness.

3. How Can You Maintain Good Health?

You can maintain good health by following a balanced and healthy diet. Have a good lifestyle by balancing work and life. You should have a moderate physical fitness regime every day. Go for brisk walks regularly or do other forms of exercise. Also, meditate and be positive to take care of your mental health.

4. Who came up with the phrase "health is wealth"?

If a man begins to live a lifestyle without a plan or unhealthy manner, he will confront numerous difficulties. He'd be depressed on the inside, untidy and filthy on the outside, and emotionally unstable all the time. A person who lives an unhealthy lifestyle will wake up late at night and early in the morning. Not only would this affect their mental condition, but it would also poison their surroundings.

There would be a lot of wrath and sadness, and they would have fits from time to time.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

18 The Value of Health

Daniel M. Hausman earned his philosophy PhD in 1978 at Columbia University, and has taught at the University of Maryland at College Park, Carnegie Mellon University, and since 1988 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Published: 07 April 2015

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Health is valuable both instrumentally, in terms of its consequences for autonomy, opportunity, and well-being, and intrinsically, at least with respect to the mental states it encompasses. Quantifying the value of health is problematic, because there are many different ways in which people may suffer diminished health. Because of this multidimensionality, the “healthier than” relation is incomplete, and health has no quantity or magnitude. Health must be measured by its value. But it has different values, and the same token health states will have different values in different environments or for people who have different goals and activities. The value of types of health states must thus be some sort of average of the varying values of tokens. Assigning those average values is challenging, and actual techniques, which rely on preference surveys, are problematic.

This chapter will be concerned exclusively with the value of human health. In particular, I shall be concerned with the value of a person’s health to that person, with the ways in which health is good for people. One important way in which health is good for a person is if health contributes to that person’s well-being. But I shall not assume that the only way that health can be good for someone is through its bearing on well-being. Health may, for example, also contribute to freedom and independence, or it may constitute a personal good of its own kind.

It is uncontroversial that health is extremely valuable. Every culture values health highly, even as cultures disagree on details concerning what constitutes health. Health is not, however, always good for people. Those German men who were too unhealthy to serve in the Nazi armies were fortunate to miss out on the Eastern Front. Yet exceptions such as this one do not impugn the generalization that health is usually very good for people.

One obvious explanation of this generalization is that a minimal level of health is required for action, consciousness, and life itself. Without some minimal level of health, nothing else can make people’s lives go well. Health beyond what is required for life and basic functioning is also of great value. Why? Three immediate answers come to mind, all of which are correct as far as they go. First, health is an extremely important cause of well-being. But this answer tells us little until we have some account of how health contributes to well-being. A second quick answer is that people value health. But this claim, true as it is, does not tell us much without an account of health that explains and justifies the value that people place on health. A third answer is that health promotes other values such as opportunity and autonomy. But again one must ask how health does so.

To understand the value of health, one needs to clarify what health is. That will be the task of the first two sections. Section 18.3 begins the task of explaining what constitutes better health and whether health has a scalar value, and section 18.4 considers whether preferences can serve as measures of better health, as is assumed by most of those working on health measurement. Section 18.5 addresses the question of whether a measurable scalar value can be assigned to health, and section 18.6 assesses three accounts of the value of health. Section 18.7 concludes.

18.1. Evaluative Views of Health

There is a large literature concerning the concept of health. Most of it takes health to be the absence of physical or mental disease or impairment. Although I shall take for granted this negative characterization of health, it is not uncontested. In 1947, the World Health Organization famously defined health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (1948: 100). But this definition conflates health and well-being, and, without ever explicitly repudiating it, the World Health Organization itself relies on narrower characterizations of health. Lennart Nordenfelt defends a positive “holistic” view of health as a second-order ability to realize one’s goals (2000: 79–81). Carol Ryff has written extensively on positive health, which she identifies primarily with possessing purpose in life and quality relations with other people, although in her view other goods such as self-esteem and mastery are closely connected. She writes, “Positive health is ultimately about engagement in living” ( Ryff and Singer 1998 : 10).

Rather than interpreting those who see health as well-being (or a generalized ability to realize one’s goals or as engagement with living) as disagreeing about the properties of some single thing called “health,” I think these contrasting claims reveal that there are multiple notions of health. According to the broad concept of health I shall discuss—health as the absence of pathology—which is the concept employed by pathologists and physiologists, health depends on the functioning of the parts and processes within people’s bodies and minds. Although being Jewish was likely to be fatal condition if one lived in Eastern Europe in the early 1940s, it was not itself a physical or mental pathology (though some Nazis mistakenly believed otherwise). Even those who maintain that there is a great deal more to health than what is “within the skin” can recognize a “negative” notion of health as the absence of pathology.

Having in this way limited the notion of health under discussion, controversies remain concerning what constitutes pathology. The many detailed accounts are of two general kinds: naturalist and evaluative. According to evaluative views, it is part of the concept of health that it is good for an organism, and our evaluative standards—particularly concerning well-being—help to define health. It might appear that evaluative theorists are obviously right. 1 Whether something is a disease apparently depends on whether it is bad for an organism in ordinary environments. 2 Tristram Engelhardt provides a memorable example of the way in which values have affected disease classification in his discussion of the history of masturbation, which for a couple of centuries was widely regarded as a disease in Europe and the United States ( Engelhardt 1974 ). Consensus was never complete, and there were disputes about whether masturbation is a physical or a mental disease and about whether masturbation is a cause of disease rather than a disease itself. But much of the medical community regarded it as a medical disorder, and doctors prescribed treatments ranging from opium, cold baths, and visits to prostitutes for men to clitoridectomies for women. It is obvious in retrospect and was obvious at the time that moral judgment influenced disease classification. Tissot’s influential mid-eighteenth-century treatise asserts, “We have seen that masturbation is more pernicious than excessive intercourse with females. Those who believe in a special providence account for it by a special ordinance of the Deity to punish this crime” (1758; quoted in Engelhardt 1974 : 239).

Engelhardt sums up as follows:

Insofar as a vice is taken to be a deviation from an ideal of human perfection, or “well-being,” it can be translated into disease language. . . . The shift is from an explicitly ethical language to a language of natural teleology. To be ill is to fail to realize the perfection of an ideal type; to be sick is to be defective rather than to be evil. . . . The notion of the “deviant” structures the concept of disease providing a purpose and direction for explanation and for action, that is, for diagnosis and prognosis, and for therapy. A “disease entity” operates as a conceptual form organizing phenomena in a fashion deemed useful for certain goals. The goals, though, involve choice by man and are not objective facts, data “given” by nature. They are ideals imputed to nature. ( Engelhardt 1974 : 247–48)

Engelhardt concludes that health is the absence of defect or deviance, where defect and deviance are evaluative notions that depend on views of well-being, perfection, virtue, and duty.

It is, however, questionable whether the case of masturbation supports an evaluative view of health such as Engelhardt’s ( Boorse 1997 : 72–78). Whether historical claims concerning attitudes toward masturbation are true depends on what people in the nineteenth century believed and why they believed what they did, rather than the definition of health. If one believes that masturbation involves physical or mental states that are bad for people, then according to the evaluative theorist, one ought to believe masturbation is a disease. Thus evaluative theorists regard nineteenth-century physicians as justified in their belief that masturbation (as an activity that issues from and causes harmful physical or mental states) is a disease, given their belief that masturbation is bad for people. The naturalist in contrast denies that harmful physical and mental states are automatically diseases and that diseases must be harmful. In some circumstances heresy is a fatal mental condition and flat feet a life-saving escape from the draft. Yet flat feet are pathological, while heresy may be healthy.

There has, of course, been a huge change in values concerning masturbation, and that change in values has been both a cause and an effect of a change in attitudes toward whether masturbation is a disease. But when one looks more closely, it turns out that the claim that masturbation is a disease was not defended by normative condemnation. The case rested instead on a long list of false assertions about the effects of masturbation on the functioning of other organ systems and about the mechanisms through which masturbation had these effects. Those false assertions were no doubt often motivated by moral objections to masturbation, but the causal connections show only that moral commitments can cause people to make false factual claims, not that morality defines pathology. The effects of masturbation were supposed to derive from debilitation caused by the loss of semen. But the loss of semen is not debilitating and has few effects on other organ systems. Masturbation does not result in the loss of more semen than intercourse, which was held to be harmless (apart from the risks of venereal disease), and some other theory had to be concocted to generate a mechanism whereby female masturbation diminished the functioning of body parts. Whether via the loss of semen or in some other way, masturbation does not cause stomach aches, epilepsy, blindness, deafness, vertigo, heart irregularities, or rickets—all of which were alleged to be its effects. If masturbation had these effects, then masturbation would be a disease or a cause of disease such as anorexia or cutting oneself. To the extent that those who regarded masturbation as a disease felt it incumbent on them to show that it had other physiological consequences than a morally condemnable self-induced orgasm, they seem to be repudiating rather than presupposing the view that Engelhardt defends. They apparently did not believe that it was sufficient to point out that masturbation is “a deviation from an ideal of human perfection.”

Even though those who regarded masturbation as a disease were not content to point out that it was a normative defect, Engelhardt might still be right. Why shouldn’t someone who regards masturbation as a defect regard masturbators as sick, just as most Americans are inclined to regard necrophiliacs as sick? 3 If God or evolution designed our sexuality exclusively to lead us to seek intercourse with living members of the opposite sex, then there is a malfunction in those who masturbate or have homosexual encounters or have intercourse with animals or cadavers, just as there is a malfunction in those who prefer a meal of mouse droppings to a decent dinner. (But notice that this thought shifts from a view of disease as morally, prudentially, or aesthetically bad to a view of disease as malfunction.)

Evaluative theorists maintain that it is a conceptual truth that health matters to what people value (see, for example, Cooper 2002 ; Engelhardt 1974 ; Reznek 1987 ). Poor health is supposedly an automatic excuse for certain behavior, a justification for sympathy and the provision of care, and something that diminishes overall well-being. But these claims appear to be false. 4 For example, infertility in young adults is unquestionably pathological. It is a failure of the reproductive system to do what it is designed to do. It may justify medical treatment. Yet many people seek infertility, at least temporarily. Women who are reversibly infertile because they are taking birth-control pills (and by virtue of lacking normal capacities thus not fully healthy) or men who have had vasectomies after having fathered as many children as they want are typically not worse off all things considered. They do not have a condition requiring medical treatment or excusing behavior that would ordinarily be condemned, and their condition does not call for sympathy or care from others.

An evaluative theorist has three possible ways of conceding that apparently better health can be worse for a person. First, even if circumstances are such that better health in a particular regard has harmful consequences, it might still be better in other respects. Second, evaluative theorists might question whether the physical and mental states that people take to be healthy are, regardless of the circumstances, always in fact healthy. On this view, premenopausal women who are sexually active and want to avoid pregnancy are healthier if infertile, because infertility is better for them than fertility, while infertility is unhealthy in those premenopausal women in whom it is involuntary and unsought. A third possibility for the evaluative theorist is to maintain that it is a conceptual truth that states of better health are typically or usually better for people rather than invariably so. Cases in which it is better to be less healthy do not constitute counterexamples to these loose conceptual connections.

These three ways in which the evaluative theorist can meet the challenge posed by cases in which it seems that it is worse to be healthier, leave one wondering how substantial the disagreements between evaluative and nonevaluative views of health actually are. On the first alternative, it is a conceptual truth that setting aside their consequences (which may in unusual cases be harmful) states of better health are better for people. Most nonevaluative theorists agree that apart from unusual circumstances, better health is typically better. So the disagreement turns on whether it is a conceptual or contingent truth that health is a good thing. If evaluative theorists protect their claim in the second way by labeling physical and mental states that serve people’s purposes as states of better health regardless of the functional deficiencies they may involve, then it seems that the evaluative theorist is concerned with a different notion of health than the one that is employed in pathology and physiology. The disagreement collapses into an argument about how to use the word “health.” With the proper translation manual, it is questionable whether the evaluative theorist is asserting anything that the nonevaluative theorist denies. On the third alternative, it is also doubtful whether any important disagreement remains between evaluative and nonevaluative or naturalistic views of health. The evaluative theorist maintains that it is a conceptual truth that good health is generally good for people. The naturalist agrees that good health is generally good for people, but denies that this is a conceptual truth. What is at issue?

Perhaps the source of disagreement lies in the independent characterization of health that the naturalist provides and to which we shall now turn. Notice that evaluative views of health make it difficult to see how the term “health” can be used univocally to refer to states of people, animals, plants, or (more debatably) ecosystems. Health is usually a very good thing both intrinsically and instrumentally, and an evaluative view is defensible. But, as we have seen, to mount a successful defense of a conceptual connection between health and benefit requires some fancy footwork.

18.2. Naturalistic Views of Health

The leading nonevaluative “naturalistic” view of health is Christopher Boorse’s biostatistical view (1977, 1987, 1997; see also Wakefield 1992 and Hausman 2012a ). In Boorse’s view, a pathology obtains when the functioning of parts or processes of the body or mind is appreciably less efficient than what is statistically normal in the relevant reference class in typical environments. Boorse defends a goal-contribution view of functions, whereby the function of a part of a directively organized system consists of the contribution that the part makes to how well or how probably the system achieves its goals. A directively organized system is one that shows resilience in the pursuit of its goals, where that resilience is explained by the structure of the system. Central goals of human beings, like other living things, are survival and reproduction. These goals are not determined by moral or prudential considerations. They are instead enforced by evolution. The functions of parts of human beings are the contributions those parts make to survival or reproduction or to the achievement of narrower goals of particular subsystems to which the parts belong. The functioning of the parts of people is healthy when it is not much below the median level of functional efficiency in a typical environment for the relevant reference class. Reference classes are narrower than whole populations, because unimpaired capacities of male and female and of different age groups differ. Infertility is not pathological in seventy-year-old women, and men who are unable to breastfeed have no disease.

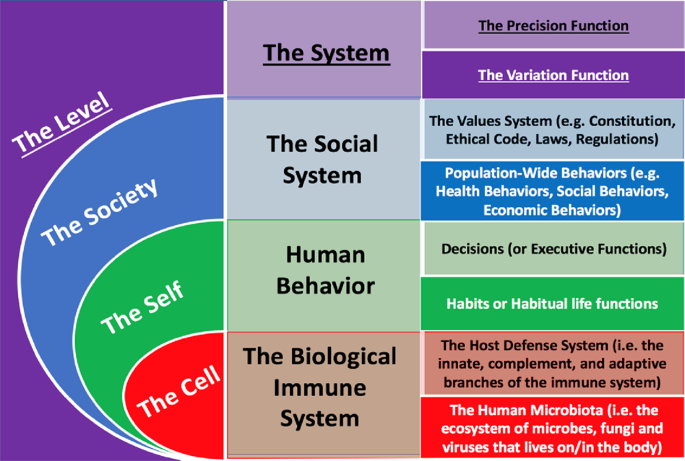

Figure 18.1 , drawn by Boorse (1987 : 370 and 1997 : 8), 5 helps clarify the view. Although Boorse draws what looks roughly like a normal distribution, there is no reason why the distribution of functional efficiency should be symmetrical, single-peaked, or continuous. There might be a small number of discrete levels. Median functional efficiency (which in a skewed distribution could be less than or greater than the mode) defines what is statistically normal.

The Biostatistical Theory

Although the median in the distribution of levels of functional efficiency (in a typical environment) determines a benchmark, the distribution plays no further role in locating the line between pathological and healthy part function. Among the levels of functional efficiency that are lower than the median level, the level of functioning (as determined by the contribution the part makes to the goal-achievement of the systems to which the part belongs) determines whether functional efficiency is adequate and hence healthy or not. Functional efficiency that is “significantly” worse than the median level is pathological. Although functional efficiency is a matter of how well a part is functioning and is thus an evaluative notion, the standards of good functioning depend on a part’s contribution to the systems to which it belongs and ultimately to survival and reproduction. Considerations of well-being, aesthetics, and virtue are irrelevant.

In denying that there is any conceptual connection between health and well-being or other human values, naturalistic theories need not maintain that the relationship between health and well-being is solely instrumental. Health states may also be constituents of well-being, but whether certain levels of functional efficiency contribute to or constitute elements of well-being or other human values in specific environments is a separate question from their contribution to system goals and ultimately survival or reproduction.

18.3. Why Is It Better to Be Healthier?

What is it that makes it better to be healthier? To answer this question, more needs to be said about what it is to be healthier. This turns out to be trickier than it might at first appear, because pathology and health are multidimensional. One person may be in pain, another suffering a cognitive deficiency, a third unable to see. How are these different health states to be compared? To impose some order and to value these health states, health economists have constructed health state classifications and have then assigned values to the health states so classified. 6 Unlike someone’s health, which depends not just on her instantaneous physical and mental states, but on their trajectories through time, health economists take a person’s health state to be a snapshot at a moment, without reference to past or future. Just as the distance an object travels over an interval is the time integral of its instantaneous velocity, so a person’s health during a period is the time integral of the person’s health states. So, for example, the health state now of a woman with a symptomless cancer that will kill her in a few weeks could be little different from the health state of someone in full health. The fact that her health (as opposed to her instantaneous health state) is very poor shows up in her expected trajectory through increasingly terrible health states. Once one has classified the instantaneous health states, one can define people’s health in terms of actual or expected trajectories through these health states. The classification of health states is fundamental to this way of describing people’s health. For an example, the Health Utilities Index distinguishes eight “dimensions” of health: vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion, cognition, and pain, and distinguishes five or six levels of severity of deficiencies along each dimension, for a total of 972,000 health states.

As health-classification systems such as the Health Utilities Index recognize, people’s health states are multidimensional. In this regard health states are analogous to consumption bundles in consumer choice theory. A person’s consumption bundle consists of quantities of fruits, fish, water, wine, haircuts, home heating, and so forth, and though one bundle of commodities and services may cost more than another or provide an individual with greater happiness, there is no way to say that one bundle of commodities is literally larger than another, apart from the special case of dominance in which one bundle contains at least as much of each commodity as another and more of some commodities. Although Mitt Romney is much richer than most readers of this volume and consumes a more expensive bundle of commodities, as a Mormon, his beer consumption is probably much lower than that of an average college student. The bundle of commodities he consumes is probably neither literally larger nor smaller than the bundles of commodities and services consumed by different readers of this essay.

Just as one person’s commodity bundle is often neither larger nor smaller than the commodity bundle of another, so it is frequently the case that one person has no larger or smaller quantity of health than another. One can compare how happy people are in various health states or what their median income is or how much on average they prefer one health state to another, but there is no way to say that Jack has literally more health than George, unless Jack’s health state dominates George’s—that is, unless Jack’s health state is no worse than George’s along any dimension and better along at least one dimension. It is tempting to suppose that one might make comparisons in terms of something like “overall functioning,” but this is an illusion. 7 How is one to judge whether Jack, who has a very limited short-term memory, is healthier than Jane, who needs a walker to get around, or Jessica, who is very hard of hearing? What evidence bears on this question?

The relation “is at least as healthy as” is massively incomplete : most health states cannot be compared in their quantity or magnitude of health. It is not just that we cannot tell: there is no truth condition for the claim that one set of functional deficiencies constitutes a greater quantity or magnitude of health than another, unless the former dominates the latter. There is no such thing as a quantity or magnitude of health, just as there is no such thing as the “size” of a commodity bundle.

But, of course, we compare people’s health all the time. If Jack is bedridden, senile, and deaf but has good vision, he seems to be clearly less healthy than George, who is color-blind, but otherwise healthy. Health comparisons such as this one are, I suggest, in fact comparisons of the value of different health states, of how good different health states are. When we say that one person is healthier than another, we usually mean that the first person’s health is better . Similarly, when we say that Mitt Romney has more goods than the typical steelworker, we mean that his goods are more expensive or that most people would gladly trade the steelworker’s bundle of commodities for Romney’s. Though one person rarely possesses literally more or less health than another, it is often the case that one person’s health is better or worse than another’s.

Rather than finding a basis for the value of health in clarifying the measure of health, we have found that there is no measure of health apart from its value. So we might as well ask directly: what is it for one person’s health to be better than another’s or for someone’s health to be better at one time than at another? One finds different answers in the literature. Norman Daniels cashes out the value of health in terms of opportunity (1985, 2007). In his view, someone’s health at t is better than their health at t ′ (or than someone else’s health at some time) if he or she has greater access to the normal opportunity range for someone of that age and sex in that social position and with those talents. Paul Dolan disagrees. He maintains that the value of a health state consists in the quality of subjective experience it involves ( Dolan and Kahneman 2008 ). John Broome (2002 : 94) and Dan Brock (2002 : 117) assert that how good someone’s health is is a matter of the contribution that their health makes to their well-being either as cause or component. The health measure in use in England and some other European countries takes the value of health to be a component of well-being, which health economists call “health-related quality of life.” In practice, health economists usually take one health state to be better than another if and only if people prefer the former to the latter, regardless of the reasons for the preference.

None of these views seems satisfactory. The value of health cannot be cashed out entirely in terms of opportunities. Subjective experience is also important, whether or not it affects opportunities. But opportunity and capacities are important: health cannot be measured entirely in terms of subjective experience either. Subjective experiences are often good indicators of our health—indeed one can conjecture that the evolutionary point of many of our feelings is precisely to indicate what states of our bodies are healthy or diseased. But if our evidence is faulty or we have nervous, cognitive, or affective disabilities, our subjective experience may be excellent when our health is poor. Those with congenital analgesia (an inability to feel pain) are not in better health than those who feel pain.

Nor does the measure of health consist in its bearing on well-being. People with disabilities such as deafness who have coped successfully with their disability may be as well off as people without any disabilities. Whether deafness is a disability does not depend on whether it diminishes the quality of life. It sounds more plausible to maintain that the value of health consists in health-related quality of life, but I suspect that this view appears to be more plausible mainly because it is unclear what health-related quality of life is. What would it mean to say of someone who is deaf and is living an excellent life that her “health-related quality of life” is worse than someone who can hear? As John Broome has argued (2002), there is no way to decompose someone’s well-being into some set of components, with a subset constituted or caused by the person’s health. For example, as Allotey and coauthors (2003) vividly document, the extent to which paraplegia diminishes the quality of life differs dramatically depending on whether one confronts social, natural, and technological circumstances like those in Australia or like those in Cameroon.

18.4. Preferences and the Value of Health

What about preferences? Do they enable health economists to value health states sensibly? Economists do not typically define what they mean by preferences, and when they do offer definitions, they often make indefensible claims that are inconsistent with their own practices. In Preference, Value, Choice and Welfare (2012), I argue that the interpretation of preferences that best fits the practice of economists takes preferences to be subjective total comparative evaluations. What this means is the following:

Preferences are subjective states that combine with beliefs to explain choices. They cannot be defined by behavior. Even in the simplest case in which Sally faces a choice between just two alternatives, x and y , one cannot infer that she prefers x over y from her choice of x without making assumptions about her beliefs. If Sally mistakenly believes that the choice is between x and some alternative other than y , then she might choose x from the set {x, y} despite preferring y to x .

Preferences are comparative evaluations . To prefer x to y is to judge how good x is in some regard as compared to y . To say that Sally prefers x is elliptical. If Sally prefers x , she must prefer x to something else.

Third, preferences are total comparative evaluations—that is, comparative evaluations with respect to every factor that the individual considers to be relevant. Unlike everyday language where people regard factors such as duties as competing with preferences in determining choices, economists take preferences to encompass every factor influencing choices other than beliefs and constraints.

Fourth, as total comparative evaluations , preferences are cognitively demanding. Like judgments, they may be well or poorly supported and correct or incorrect.

On this understanding of preferences, there are strong reasons to deny that one health state H is better than another, H ′, if and only if people prefer H to H ′. First, people might prefer H to H ′, despite believing that H ′ was a state of better health. For example, a manic-depressive may prefer not to treat her disease, because of what she is able to achieve during manic periods, without believing that she is in better health when not medicated.

Health economists might respond that cases in which people judge that H ′ is a better health state than H but prefer H are unusual and may be ignored. Though not defining what it is for one health state to be better than another, perhaps preferences are reliable indicators of how good or bad health is. But it is questionable whether preferences are reliable indicators of health, because people’s preferences among health states are likely to be mistaken. When economists measure people’s preferences among flavors of ice cream or makes of cars, they are asking people for their comparative evaluations of alternatives that the respondents understand well, that they have had ample opportunity to consider, and concerning which they have a great deal of information. When, in contrast, health economists ask people to express their preferences among health states, they are asking people to appraise unfamiliar alternatives concerning which respondents typically have no secure preferences at all.