- Countries and Their Cultures

- Culture of Moldova

Culture Name

Alternative names.

Moldavian, Romanian, Bessarabian. Moldavia is the Anglicized version of the Russian Moldavija and is not used by Moldovans. Many Moldovans consider themselves, their culture, and their language Romanian. Moldovans/Romanians in the region between the rivers Prut and Dniestr sometimes call themselves Bessarabians.

Orientation

Identification. The principality of Moldova was founded around 1352 by the Transylvanian ruler ( voievod ) Dragoş in what today is the Romanian region of Bucovina. According to one legend, Dragoş successfully hunted a wild ox on the banks of the river Moldova and then chose to stay in the land, which he named after the river. The name "Moldova" probably derives from the German Mulde , "a deep river valley with high banks."

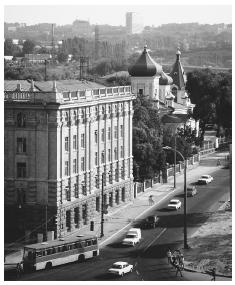

Location and Geography. The Republic of Moldova is a landlocked country between Romania and Ukraine that covers 13,199 square miles (33,845 square kilometers). It includes the Gagauz Autonomous Region in the south and the disputed Transdniestrian region in the east. The latter region separated from Moldova in 1991–1992 but did not gain official recognition. The capital, Chişinău, is in the center of the country and has 740,000 inhabitants. Chişinău was first mentioned in 1436 and was the capital of the Russian province of Bessarabia in the nineteenth century.

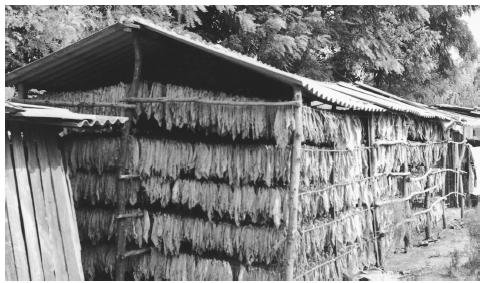

Moldova is on a fertile plain with small areas of hill country in the center and north. Only 9 percent of its territory is covered by forest, mostly in the middle. In the northern part, fertile black soil prevails and the primary crop is sugar beet. In the central and southern zones, wine making and tobacco growing are widespread. The temperate continental climate in the center of the country, with long warm summers, relatively mild winters, and high rainfall, is favorable for agriculture. The semiarid Budjak steppe in the south has drought problems. The main rivers are the Dniestr in the east and the Prut in the west. Both originate in the Carpathians; whereas the Dniestr flows directly into the Black Sea, the Prut joins the Danube at the southern tip of the country.

Demography. Moldova has 4.32 million inhabitants. In the 1989 census, 64.5 percent of the population was Moldovan, 13.8 percent Ukrainian, 13 percent Russian, 3.5 percent Gagauz (a Christian Orthodox Turkic people), 2 percent Bulgarian, 1.5 percent Jewish, and 1.7 percent other nationalities, mainly Belarussians, Poles, Greeks, Germans, and Rom (Gypsies). Although the official number of Rom is only 11,600, the real number probably is 100,000. There are few concentrated Rom settlements in Moldova, and the degree of linguistic assimilation (Russian or Moldovan) is high. The Ukrainian population traditionally settled in the north and east. Gagauz and Bulgarians have concentrated settlements in the southern Budjak region. The Russian population, for the most part workers and professionals brought to Moldova after World War II, is concentrated in Chişinău, Bălţi, and the industrial zones of Transdniestria. Jews have lived in Moldovan cities in great numbers since the early nineteenth century, but many have left. Between 1990 and 1996, Moldova experienced a total migration loss of 105,000 persons. Jews, Ukrainians, and Russians were the most likely to leave. Consequently, the Moldovan portion of the population was believed to have increased to 67 percent by 1998. The population density is the highest in the territory of the former Soviet Union.

Symbolism. The national symbols represent over six hundred years of history as well as a close connection to Romania. The state flag is composed of the traditional Romanian colors of blue, yellow, and red. In the center is the republic's seal, consisting of the Romanian eagle with the historical Moldovan seal on its breast. Since the fourteenth century, the seal has consisted of an ox's head with a star between its horns, a rose to the right, and a crescent to the left. The national anthem was the same as that of Romania in the early years of independence but was changed to "Our Language" ( Limba noastră ), which is also the name of the second most important secular holiday. Its name has a special integrating power in two respects: Language is the most important national symbol for Moldovans, and it evades the answer to the question of how this language should be labeled: Romanian or Moldovan. All these symbols, however, do not appeal to other ethnic groups and thus confine the idea of an "imagined community" to the titular nation.

In regard to the conflict over symbols between "Romanians" and "Moldovans," the ballad Mioriţa plays a crucial role. It tells the story of a Moldovan shepherd who is betrayed and murdered by two Romanian colleagues: For the Romanian side, this story is about an "incident in the family," while for the Moldovan side, it reproduces the distinction between the good, diligent, and peaceful Moldovan and the mean and criminal Romanian. Next to hospitality, diligence and peacefulness are the national characteristics Moldovans associate with themselves. When Moldovans want to show pride in their country, they refer mostly to the qualities of its wine and food and the beauty of its women. Wine is an especially powerful symbol, associated with quality, purity, and healing. The cellars of Cricova with their extensive collection of old wines are considered the state treasure. Moldovans are also eager to underscore their Latin heritage, expressed by the statue of a wolf feeding Romulus and Remus in front of the Museum of National History in Chiţinău.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. According to official historiography, the Republic of Moldova derives directly from the Moldovan principality that was founded by Dragoş and gained independence from the Hungarian kingdom under the Valachian voievod Bogdan I in 1359. The government thus celebrated the 640th anniversary of statehood in 1999. However, what is today the Republic of Moldova consists only of the central and eastern parts of the original principality. The Transdniestrian region was never part of the principality, but Moldovan colonists settled on the left bank of the Dniestr in the fifteenth century. At the beginning of the fifteenth century, the principality extended from the Carpathians to the Dniestr. Under Stephen the Great (1457–1504), who defended the principality successfully against the Ottoman Empire, Moldova flourished. Many churches and monasteries were built under his regency. Stephen is regarded as the main national hero of contemporary Moldova. His statue stands in the city center of Chişinău, the main boulevard is named for him, and his picture is printed on every banknote. However, soon after Stephen died, Moldova lost its independence and became, like the neighboring principality of Valachia, a vassal state of Constantinople.

In the Treaty of Bucharest of 1812, the Ottoman Empire was forced to cede the area between the Prut and the Dniestr to the Russian Empire under the name Bessarabia. In 1859, western Moldova and Valachia formed the united principality of Romania, which gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1878. Thus, the Moldovans in Bessarabia were excluded from the Romanian nation-building process and remained in an underdeveloped, remote, agricultural province of the Russian Empire. Only with the upheavals of the World War I and the October Revolution did the Moldovans of Bessarabia join the Romanian nation-state. The Moldovan parliament, the Sfatul Ţării, declared the independence of the "Democratic Republic of Moldova" on 24 January 1918 but then voted for union with Romania on 27 March 1918. The unification was mostly due to the desperate circumstances the young, unstable republic faced and was not applauded by all sections of the population. The following twenty-two years of Romanian rule are considered by many Moldovans and non-Moldovans as a period of colonization and exploitation. The subsequent period of Sovietization and Russification, however, is regarded as the darkest period in the national history. Stalin annexed Bessarabia in June 1940 and again in 1944, when the Soviet Union reconquered the area after temporary Romanian occupation. The northern and southern parts of Bessarabia were transferred to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR), and in exchange the western part of what since 1924 had been the Moldovan Autonomous Socialist Republic on the territory of the Ukrainian SSR was given to the newly created Moldovan Socialist Soviet Republic. Having been ruled by foreign powers since the sixteenth century, Moldova declared its independence on 27 August 1991.

National Identity. After sentiments ran high in favor of unification with Romania at the beginning of the 1990s, the tide turned, and in a 1994 referendum 95 percent of the voters elected to retain independence. As a result of their close historical, linguistic, and cultural ties with Romania, many Moldovans see themselves as Romanian. At the same time, the one hundred eighty years of separation from Romania and the different influences Bessarabia has experienced since the early nineteenth century have preserved and reinforced a distinctive Moldovan identity east of the Prut. Unlike Romanians, a high percentage of Moldovans have an ethnically mixed family background. Consequently, probably less than 5 percent of the people consider themselves to have a pure Romanian identity, whereas another 5 to 10 percent would identify themselves as Moldovan in the sense of being outspokenly non-Romanian. The existence of these two groups is reflected in a fierce debate between "Unionists" and "Moldovanists." Most inhabitants of the titular nation consider their Moldovan identity as their central political one but their Romanian identity as culturally essential. Since discussions on unification with Romania have disappeared from the public agenda, the question of how to form a multi-ethnic nation-state is growing in importance.

Ethnic Relations. Bessarabia has always been a multiethnic region, and ethnic relations generally are considered good. Especially in the north, Moldovans and Ukrainians have lived together peacefully for centuries and share cultural features. In recent history, Moldova has rarely experienced ethnic violence; in April 1903, for example, 49 Jews were killed and several hundred injured during the Chişinău pogrom, but mainly by Russians rather than Moldovans. In the late 1980s, when support for the national movement began to grow, ethnic tension between Moldovans and non-Moldovans increased, initially in Transdniestria and Gagauzia and later in Chişinău and Bălţi. Whereas the conflict between Gagauz and Moldovans was kept below the level of large-scale violence, the Transdniestrian conflict escalated into a full-fledged civil war in spring 1992. More than a thousand people were said to have been killed, and over a hundred thousand had to leave their homes. Although this conflict had a strong ethnic component, it was not ethnic by nature; it was fought mainly between the new independence-minded political elite in Chişinău and conservative pro-Soviet forces in Tiraspol. Moldovans and non-Moldovans could be found on both sides. On the right bank of the Dniestr, where the majority of the Russian-speaking community lives, no violent clashes took place. Since the war, additional efforts have been made to include non-Moldovans in the nation-building process. The 1994 constitution and subsequent legislation safeguarded the rights of minorities, and in the same year broad autonomous powers were granted to the Gagauz.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Chişinău's city center was constructed in the nineteenth century by Russians. Official buildings and those erected by the early bourgeoisie are in a neoclassical style of architecture; there are also many small one-story houses in the center, and the outskirts are dominated by typical Soviet-style residential buildings. Small towns (mainly enlarged villages) also have examples of Soviet-style administration buildings and apartment blocks. Depending on their original inhabitants, villages have typical Moldovan, Ukrainian, Gagauz, Bulgarian, or German houses and a Soviet-style infrastructure (cultural center, school, local council buildings). Houses have their own gardens and usually their own vineyards and are surrounded by low metal ornamented bars. Interaction differs in urban and rural areas. In the villages, people are open and greet passersby without prior acquaintance; in the cities, there is a greater anonymity, although people interact with strangers in certain situations, for example, on public transportation.

Food and Economy

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Orthodox Christian baptisms, funerals, and weddings are accompanied by large gatherings where several meat and vegetable dishes, desserts, and cakes as well as wine are served. Homemade vodka and brandy also are offered. At Easter, a special bread, pasca , is baked in every household, and eggs are painted in various colors. Families go to the graveyard to celebrate their dead kin; they eat food at the graves while drinking wine and offering it to each other as they remember the dead.

Basic Economy. The national currency is the leu (100 bani ). Besides gypsum and very small gas and oil reserves, the country has no natural resources and is totally dependent on energy imports, mainly from Russia. Moldova has experienced a sharp downturn in its economy in the last ten years. In 1998, the gross domestic product (GDP) was 35 percent of the 1989 level, and the state is unable to pay pensions and salaries on time. As a result, more people produce food and other necessities for themselves now than in the 1980s. This includes virtually the entire rural population and many city dwellers who own small gardens in the countryside. The parallel economy is estimated to account for 20 to 40 percent of the GDP.

Land Tenure and Property. During the Soviet period, there was no private land, only state-owned collective farms. Since 1990, as part of the transition to a market economy, privatization of land as well as houses and apartments has taken place. However, the process is still under way and has faced fierce resistance from so-called agroindustrial complexes.

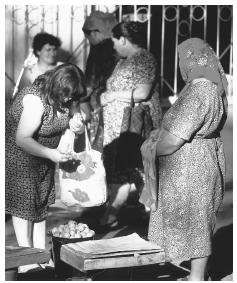

Commercial Activities. Moldova in general and Chişinău in particular have many traditional Balkan-style markets. There are mixed as well as specialized markets for food, flowers, spare parts, and construction materials. This "market economy" clearly outsells the regular shops. Besides foodstuffs, which are partially home-grown, all products are imported. These types of commercial activities are flourishing because of market liberalization and the economic downturn. Many educated specialists find it easier to earn money through commercial activities than by practicing their professions.

Major Industries. Industry is concentrated in the food-processing sector, wine making, and tobacco. Other fields include electronic equipment, machinery, textiles, and shoes. The small heavy industry sector includes a metallurgical plant in Transdniestria that produces high-quality steel.

Trade. The main trade partners are Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Romania, and Germany. Russia and other Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries accounted for 69 percent of exports and 58 percent of imports in 1998. Exports are mainly agroindustrial products (72 percent), especially wine, but also include shoes and textiles (12 percent). The main import goods are mineral products (31 percent), machinery and electronic equipment (19 percent), and chemical products (12 percent). To realign foreign trade away from Russia and toward Western European and other countries, Moldova has constructed an oil terminal on the Danube and is seeking closer economic ties with Romania and the European Union. It is expected to join the World Trade Organization.

Social Stratification

Symbols of Social Stratification. Newly built ornamented houses and villas, cars (especially Western cars with tinted windows), cellular telephones, and fashionable clothes are the most distinguishing symbols of wealth. Consumer goods brought from abroad (Turkey, Romania, Germany) function as status symbols in cities and rural areas.

Political Life

Government. Moldova is a democratic and unitary republic. Since the territorial-administrative reform of 1999, it has been divided into ten districts ( judeţe ) and the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia. A special status is envisaged for the Transdniestrian region. The political system is mixed parliamentary-presidential, with the parliament (one hundred one representatives) and president both directly elected for a four-year period. The prime minister is appointed by the president only after the minister and his or her cabinet have received a vote of confidence from the parliamentary majority. The rights of the president to dissolve the parliament are very restricted. Some executive powers are vested in the president's hands: he or she can issue decrees and has special powers in defense and foreign policy. The delicate balance of power between parliament, government, and president is held to be responsible for the relatively high level of democracy as well as the blocking of important reform projects. Consequently, there have been discussions aimed at strengthening the powers of the president. Judicial powers are vested in the courts.

Leadership and Political Officials. Patrimonial structures and the Orthodox tradition of godfatherhood have strong political implications. Personal networks established over the years help people gain political posts, but such contacts also make them responsible for redistributing resources to the people who have backed them. Although kinship has a certain influence on these personal networks, relationships established in other ways during education and earlier work may be more important. Today's political forces have their roots either in the Moldovan Communist Party or in the national movement of the 1980s. The national movement started with the creation of the Alexe Mateevici Cultural Club in 1988 as an intellectual opposition group. In less than a year, it evolved into a broad mass movement known as the Popular Front of Moldova. Although the party system has experienced striking fluctuations in the last ten years, the main political forces have in essence remained the same. The Communist Party, whose place was taken temporarily by the Agrarian Democratic Party, is still one of the strongest political players. It has a mixed ethnic background and is backed mainly by the agroindustrial complexes. It is opposed to privatization and other reforms and strongly favors the idea of "Moldovanism." At the opposite end of the political spectrum are the Christian Democratic Popular Front and the Party of Democratic Forces. Both derive directly from the Moldovan national movement and have no former communists in their ranks. The Front favors unification with Romania and advocates liberal market reforms and democratization. The Party of Democratic Forces also favors stronger ties with Romania and the West but has abandoned the idea of unification; it too blends market reforms with social democratic ideas. The former president, Mircea Snegur (1992–1996), a previous Communist Party secretary and the "father" of Moldovan independence, has been joined in his Party for Rebirth and Reconciliation by other former communists who switched to the national movement early on. Petru Lucinschi, who was elected president in 1996, held high posts in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and has extensive, well-established connections among the social-democrat-oriented former political elite. Unlike Snegur, he and the parties associated with him are widely trusted by non-Moldovan voters. In Moldovan politics everybody knows each other and personal interests, sympathies, and antipathies as well as tactical reshuffles play an important role.

Social Problems and Control. The economic crisis resulted in an increase in poverty, theft, and petty and large-scale racketeering. Illegal cultivation of opium poppies and cannabis takes place on a limited basis, with both being trafficked to other CIS countries and Western Europe. In the villages, where people relate to one another in a less anonymous way, hearsay and gossip are effective tools of social control.

Military Activity. The army consists of 8,500 ground and air defense troops and has no tanks. As a landlocked country, Moldova has no navy, and after it sold nearly its entire fleet of MIG-29 fighters to the United States in 1997, it was left practically without an air force. The 1999 budget allocated only $5 million to defense spending, 2 percent of the total budget. The Republic of Moldova takes part in the NATO Partnership for Peace Program but has no plans to join either NATO or the CIS military structure. Although it is a neutral country and the constitution rules out the stationing of foreign military forces on Moldovan soil, Russian troops are still stationed in Transdniestria.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

A system of social security covering unemployment benefits, health care, and pensions for the elderly and the disabled as well as assistance for low-income families has been set up. However, the level of social benefits is very low, and they are not paid in time because of the socioeconomic crisis. National and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) aid orphans and street children.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Several international NGOs are active, especially in the fields of human rights and development. There are several local NGOs, most of which are small and inefficient. A Contact Center tries to coordinate the activities of the Moldovan NGO community. NGOs are frequently politically biased and get involved in political campaigns. Many NGO activists often see their organizations principally as vehicles for the pursuit of their own interests.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Women in both urban and rural areas carry the burden of domestic duties and child care in addition to working outside the home. As a result of tradition and economic necessity, women engage in domestic food-processing activities in the summer to provide home-canned food for the winter months.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. When a young couple decides to marry, it is not unusual for the girl to go to her boyfriend's house and stay there. The next day her parents are informed about this, and the families come together to agree on the marriage. It can take a couple of months before the civil and religious wedding ceremonies are held. Divorce is common, and many women have to earn a living on their own after being abandoned by their husbands without the marriage being officially dissolved.

Domestic Unit. Newlyweds usually live together with the groom's parents until they can build a house in the village or rent an apartment in town. In the villages, there is a general rule of ultimogeniture (the youngest son and his family live with the parents, and he inherits the contents of the household).

Inheritance. Inheritance is regulated by law. Children inherit equally from their parents, although males may inherit the house of their parents if they live in the same household.

Kin Groups. Relatives support each other in performing agricultural and other tasks as well as ceremonial obligations. The godparenthood system regulates the mutual obligations between the parties. Godparents are responsible for the children they baptize throughout life-cycle rituals, especially marriage and the building of a house. Godparenthood is inherited between generations; however, it is also common for this role to be negotiated independently of previous ties.

Socialization

Infant Care. Babies are taken care of by their mothers and grandmothers. In villages, babies are wrapped in blankets during the very early months, and cloth diapers are used. Toddlers walk around freely, and their clothes are changed when they wet themselves.

Child Rearing and Education. Children generally grow up close to their grandparents, who teach them songs and fairy tales. Girls are expected to help their mothers from an early age and also take care of smaller siblings. A good child is expected to be God-fearing and shy and does not participate in adult conversations without being asked to do so.

Higher Education. A few universities remain from the Soviet period, together with about fifty technical and vocational schools. As a result of economic difficulties, people sometimes complete higher education in their late thirties, after establishing a family. The College of Wine Culture is a popular educational institution that offers high-quality training.

It is proper to drink at least a symbolic amount of wine during a meal or in a ritual context to honor the host and toast the health of the people present. Occasionally in villages, toasting with the left hand may not be regarded as proper. It is improper to blow one's nose at the table. Smoking in private homes is an uncommon practice; both hosts and guests usually go outside or onto the balcony to smoke. In villages, it is highly improper for women to smoke in public. People usually acknowledge passersby in the villages irrespective of previous acquaintance.

Religious Beliefs. The majority of the population, including non-Moldovans, are Orthodox Christians (about 98 percent). There are a small number of Uniates, Seventh-Day Adventists, Baptists, Pentecostalists, Armenian Apostolics, and Molokans. Jews have engaged in religious activities after independence with a newly opened synagogue and educational institutions.

Religious Practitioners. During the interwar period, Moldovans belonged to the Romanian Orthodox Church, but they now belong to the Russian Orthodox Church. There is an ongoing debate about returning to the Bucharest Patriarchate. Priests play an important role in the performance of ritual activities. In the villages, there are female healers who use Christian symbols and practices to treat the sick.

Rituals and Holy Places. The Orthodox calendar dictates rules and celebrations throughout the year, such as Christmas, Easter, and several saints' days. Some of the rules include fasting or avoiding meat and meat fat as well as restrictions on washing, bathing, and working at particular times. Baptisms, weddings, and funerals are the most important life-cycle rituals and are combined with church attendance and social gatherings. Easter is celebrated in the church and by visiting the graveyards of kin. Candles are an inseparable part of rituals; people buy candles when they enter the church and light them in front of the icons or during rituals.

Death and the Afterlife. The dead are dressed in their best clothes. Ideally, the corpse is watched over for three days and visited by relatives and friends. A mixture of cooked wheat and sugar called colivă is prepared and offered to the guests. If possible, the ninth, twentieth, and fortieth days; the third, sixth, and ninth months; and the year after the death are commemorated. However, this usually depends on the religiosity and financial resources of the people concerned. Graveyards are visited often, wine is poured on the graves, and food and colivă are distributed in memory of the dead.

Medicine and Health Care

Modern medicine is widely used. Health care is poor because of the state of the economy.

Secular Celebrations

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. In the Soviet period, state funds provided workshops for painters and other artists, who were guaranteed a regular income. This practice has ceased, and funds for workshops and other financial support are very limited. However, artists have better opportunities to sell to foreigners and the new business elites. National and international sponsors provide more encouragement for artistic activity than does the state.

Literature. The most important work of early literature is the ballad Mioriţa . Oral literature and folklore were prevalent until the nineteenth century. This and the classical Moldovan literature of the nineteenth century can hardly be distinguished from Romanian literature. The greatest Romanian writer, Mihai Eminescu, was born in the western part of Moldova and is perceived by Moldovans as part of their national heritage. Other renowned Moldovan writers include Alexei Mateevici, the author of the poem " Limba noastră ;" the playwright Vasile Alecsandri; the novelist Ion Creangă and the historian Alexandru Hâjdeu. Ion Druţa, Nicolae Dabija, Leonida Lari, Dumitru Matcovschi, and Grigorie Vieru are regarded as the greatest contemporary writers and poets.

Graphic Arts. Besides the painted monasteries around Suceava (Romania), sixteenth-century icons are the oldest examples of Moldovan graphic arts. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the sculptor Alexandru Plămădeală and the architect A. Şciusev added their work to the heritage of Bessarabian arts. Bessarabian painters of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries concentrated on landscapes and rural themes as well as typical motifs of Soviet realism. Since the recent changes, however, young modern artists such as Valeriu Jabinski, Iuri Matei, Andrei Negur, and Gennadi Teciuc have demonstrated the potential and quality of Moldovan art.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

The Academy of Science was the traditional place for research in Soviet Moldova. In an agricultural country, particular stress was placed on agriculture-related sciences, and a special Agricultural University was established for the education of specialists and for research in that field. After the political transition, the State University was reorganized and private universities, focusing mainly on economic subjects, were established.

Bibliography

Aklaev, Airat R. "Dynamics of the Moldova-Trans-Dniestr-Conflict (late 1980s to early 1990s)." In Kumar Rupesinghe and Valery A. Tishkov, eds, Ethnicity and Power in the Contemporary World , 1996.

Batt, Jud. "Federalism versus Nationbuilding in Post-Communist State-Building: The Case of Moldova." Regional and Federal Studies 7 (3): 25–48, 1997.

Bruchis, Michael. One Step Back, Two Steps Forward: On the Language Policy of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in the National Republics , 1982.

——. "The Language Policy of the CPSU and the Linguistic Situation in Moldova." Soviet Studies 36 (1): 108–26, 1984.

——. Nations-Nationalities-People: A Study of the Nationalities Policy of the Communist Party in Soviet Moldavia , 1984.

——. The Republic of Moldavia from the Collapse of the Soviet Empire to the Restoration of the Russian Empire , 1997.

——. Chinn, Jeff. "The Case of Transdniestr." In Lena Jonson and Clive Archer, eds., Peacekeeping and the Role of Russia , 1996.

——and Steve Ropers. "Ethnic Mobilization and Reactive Nationalism: The Case of Moldova." Nationalities Papers 23 (2): 291–325, 1995.

Crowther, William. "Ethnic Politics and the Post-Communist Transition in Moldova." Nationalities Papers 26 (1): 147–164, 1998.

——. "Moldova: Caught between Nation and Empire." In Ian Bremmer and Ray Tarasm, eds., New States, New Politics—Building the Post-Soviet Nations , 1997.

——. "The Construction of Moldovan National Consciousness." In Laszlo Kürti and Juliet Boulder Langman, eds., Beyond Borders: Remaking Cultural Identities in the New East and Central Europe , 1997.

——. "The Politics of Ethno-National Mobilization: Nationalism and Reform in Soviet Moldavia." Russian Review 50 (2): 183–202, 1991.

Dima, Nicholas. "Recent Ethno Demographic-Changes in Soviet Moldavia." East European Quarterly 25 (2): 167–178, 1991.

——. From Moldavia to Moldova , 1991.

——. "The Soviet Political Upheaval of the 1980s: The Case of Moldavia." Journal of Social Political and Economic Studies 16 (1): 39–58, 1991.

——. "Politics and Religion in Moldova: A Case-Study." Mankind Quarterly 34 (3): 175–194, 1994.

Dyer, Donald L., ed. Studies in Moldovan: The History, Culture, Language and Contemporary Politics of the People of Moldova , 1996.

——. "What Price Languages in Contact?: Is There Russian Language Influence on the Syntax of Moldovan?" Nationalities Papers 26 (1): 75–84, 1998.

Eyal, Jonathan. "Moldavians." In Graham Smith, ed., The Nationalities Question in the Soviet Union , 1990.

Feldman, Walter. "The Theoretical Basis for the Definition of Moldavian Nationality." In Ralph S. Clem, ed., The Soviet West: Interplay between Nationality and Social Organization , 1978.

"From Ethnopolitical Conflict to Inter-Ethnic Accord in Moldova." ECMI Report #1 , March 1998.

Grupp, Fred W. and Ellen Jones. "Modernisation and Ethnic Equalisation in the USSR." Soviet Studies 26 (2): 159–184, 1984.

Hamm, Michael F. "Kishinev: The Character and Development of a Tsarist Frontier Town." Nationalities Papers 26 (1): 19–37, 1998.

Helsinki Watch. Human Rights in Moldova: The Turbulent Dniester , 1993.

Ionescu, Dan. "Media in the Dniester Moldovan Republic: A Communist-Era Memento." Transitions 1 (19): 16–20, 1995.

Kaufman, Stuart J. "Spiraling to Ethnic War: Elites, Masses and Moscow in Moldova's Civil War." International Security 21 (2): 108–138, 1996.

King, Charles. "Eurasia Letter: Moldova with a Russian Face." Foreign Policy 97: 106–120, 1994.

——. "Moldova." In Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States , 1994.

——. "Moldovan Identity and the Politics of Pan-Romanianism." Slavic Review 53 (2): 345–368, 1994.

——. The Moldovans, Romania, Russia and the Politics of Culture , 2000.

——. Post-Soviet Moldova: A Borderland in Transition , 1995.

Kolstø, Pål. "The Dniestr Conflict: Between Irredentism and Separatism." Europe-Asia Studies 45 (6): 973–1000, 1993.

——. Andrei Malgin. "The Transnistrian Republic: A Case of Politicized Regionalism." Nationalities Papers 26 (1): 103–127, 1998.

Livezeanu, Irina. "Urbanization in a Low Key and Linguistic Change in Soviet Moldavia." Soviet Studies 33 (3): 327–351, 33 (4): 573–589, 1981.

Neukirch, Claus. "National Minorities in the Republic of Moldova—Some Lessons, Learned Some Not?" South East Europe Review for Labour and Social Affairs 2 (3): 45–64.

O'Loughlin, John, Vladimir Kolossov, and Andrei Tchepalyga. "National Construction, Territorial Separatism, and Post-Soviet Geopolitics in the Transdniester Moldovan Republic." Post-Soviet Soviet Geography and Economics 39 (6): 332–358, 1998.

Ozhiganov, Edward. "The Republic of Moldova: Transdniester and the 14th Army." In Alexei Arbatov, Abram Chayes, Antonia Handler Chayes, and Lara Olson, eds., Managing Conflict in the Former Soviet Union: Russian and American Perspectives , 1998.

Roach. A. "The Return of Dracula Romanian Struggle for Nationhood and Moldavian Folklore." History Today 38: 7–9, 1988.

Van Meurs, Wim P. "Carving a Moldavian Identity out of History." Nationalities Papers , 26 (1): 39–56, 1998.

——. The Bessarabian Question in Communist Historiography: Nationalist and Communist Politics and History-Writing , 1994.

Waters, Trevor. "On Crime and Corruption in the Republic of Moldova." Law Intensity Conflict and Law Enforcement 6 (2): 84–92, 1997.

—H ÜLYA D EMIRDIREK AND C LAUS N EUKIRCH

User Contributions:

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic:.

Welcome to WorldOfMoldova.COM here you can find info about Moldova, photos, hotels, tours to Moldova

A PHP Error was encountered

Severity: Warning

Message: Unknown: write failed: Disk quota exceeded (122)

Filename: Unknown

Line Number: 0

Message: Unknown: Failed to write session data (files). Please verify that the current setting of session.save_path is correct (/var/cpanel/php/sessions/ea-php56)

- The Culture Of Moldova

The landlocked Eastern European country of Moldova hosts a population of around 3,437,720 inhabitants. Ethnic Moldovans comprise 75.1% of the total population of the country. Romanians, Ukrainians, Russians, Bulgarians, and others constitute the rest of the country’s population. 90.1% of the population adhere to Orthodox Christianity.

5. Cuisine in Moldova

The country's cuisine mainly features traditional European foods like pork, beef, cabbage, cereals, and potatoes. Vast tracts of fertile soil also allow the cultivation of a number of fruits and vegetables that find their way into the Moldovan cuisine.

The mămăligă (a type of porridge) is a staple of the cuisine and is usually served with meat dishes or stews. Sour cream, cheese, or pork rind are used to garnish it. Other popular food items include the ghiveci (a goat or lamb stew) and brânză (brined cheese), beef meatballs, grilled pork, stuffed cabbage rolls, noodles, chicken, etc.

Cuisines of the ethnic minorities are predominant in certain areas of the country where the respective minority communities live in large numbers. For example, meat-filled dumplings called pelmeni are eaten by the Russian community, and a mutton soup called shorpa is consumed by the Gagauz peoples.

Beer, Moldovan brandy, and local wine are popular alcoholic beverages. Fruit juice and stewed-fruit compotes are widely consumed non-alcoholic beverages.

4. Literature and Graphic Arts in Moldova

Prior to the development of written literature, oral literature was prevalent in the country in the form of folk legends, fairy tales, historical songs, heroic epics, ballads, lyrical songs, etc. The first written records in the form of historical and sacred texts appeared in the country in the Old Church Slavonic language. Secular literature developed in Moldova at around the end of the 17th century. The Romanian and Moldovan literature of this time exhibits significant overlap.

Paintings in monasteries and 16th-century icons are the oldest examples of Moldovan art. Bessarabian arts flourished in the 19th and 20th centuries. Such art concentrated on rural themes and landscapes. Today, Moldovan artists explore various genres of art. The presence of art galleries and art schools throughout Moldova encourage young artists to pursue their career in art.

3. Performing Arts in Moldova

The music tradition of Moldova is closely related to that of its neighbor, Romania . Folk and classical music are popular in the country while jazz is also widely performed. The folk music of the country is associated with syncopation, complex and swift rhythms, and melodic ornamentation. O-Zone is a popular Moldovan pop band. Folk music and dance performances are held during cultural festivals and ceremonies. Rock and pop concerts are held in urban areas and are popular among the Moldovan youth.

2. Sports in Moldova

Football is the most popular sports in Moldova. The Zimbru Stadium in Chișinău serves as the home ground of the country’s national football team. Moldova also performs well in basketball and its national team has earned some success in the FIBA European Championship for Small Countries. Cycling is also an important sport in Moldova. The Moldova President's Cup is a prestigious annual cycling race held in the country. Moldovan sportsmen in the fields of boxing, canoeing, shooting, and wrestling have won some Olympic medals for the country.

1. Life in a Moldovan Society

The Moldovan law provides men and women equal rights and freedoms. Members of both genders work outside the home. However, women are usually expected to manage the household chores and children in addition to their jobs. While men have higher decision-making power than women, the latter act as organizers in daily life.

Marriages are generally based on romantic relationships. Once the couple decides to marry, families are usually involved to agree on the marriage. Divorces are not uncommon in a Moldovan society.

Residences are primarily patrilocal in nature. The newlyweds live with the family of the groom. Later, they might move out if they build a home elsewhere. In the rural areas, the traditional society maintains the rule that the youngest son inherits the paternal home but he has to take care of his elderly parents.

Mothers and other female members of the family take care of the children. Grandparent-grandchildren relationships are highly valued in Moldovan society.

While the urban Moldovan society closely resembles that in many parts of the Western world, more traditional ways of life are visible in the rural areas of the country. In villages, the sight of women smoking in public is frowned upon. Men refrain from smoking inside the home and consider it polite to go outside to smoke. People in villages greet each other with respect and politeness.

More in Society

Countries With Zero Income Tax For Digital Nomads

The World's 10 Most Overcrowded Prison Systems

Manichaeism: The Religion that Went Extinct

The Philosophical Approach to Skepticism

How Philsophy Can Help With Your Life

3 Interesting Philosophical Questions About Time

What Is The Antinatalism Movement?

The Controversial Philosophy Of Hannah Arendt

Roamopedia.com

Exploring Moldovan Culture: Traditions, Customs, Language, and Etiquette

- Connectivity

- Accommodation

- Points of Interest

- Local Cuisine

- Transportation

- Health concerns

- Visa Requirements

- + - Font Size

- BUCKET LISTS

- TRIP FINDER

- DESTINATIONS

- 48HR GUIDES

- EXPERIENCES

- DESTINATIONS South Carolina 3 Ways to Get Wet and Wild in Myrtle Beach BY REGION South America Central America Caribbean Africa Asia Europe South Pacific Middle East North America Antarctica View All POPULAR Paris Buenos Aires Chile Miami Canada Germany United States Thailand Chicago London New York City Australia

- EXPERIENCES World Wonders 14 Landmarks That Should Be Considered World Wonders BY EXPERIENCE Luxury Travel Couples Retreat Family Vacation Beaches Culinary Travel Cultural Experience Yolo Winter Vacations Mancations Adventures The Great Outdoors Girlfriend Getaways View All POPULAR Cruising Gear / Gadgets Weird & Wacky Scuba Diving Skiing Hiking World Wonders Safari

- TRIP FINDER Peruvian Amazon Cruise BY REGION South America Central America Caribbean Africa Asia Europe South Pacific Middle East North America Antarctica View All POPULAR Colors of Morocco Pure Kenya Costa Rica Adventure Flavors of Colombia Regal London Vibrant India Secluded Zanzibar Gorillas of Rwanda

- Explore Bucket Lists

- View My Bucket Lists

- View Following Bucket Lists

- View Contributing to Lists

Moldova — History and Culture

As with many newly-independent countries, Moldova has a long history and fascinating culture which are a source of real pride for its people. The country is still struggling to rid itself of remnants of the Soviet era and to evolve with modern Europe while retaining its traditional values and unique identity.

As with the rest of the Balkan region, Moldova has a history that stretches back to the original Neolithic settlers of the vast area between Ukraine’s Dniester River and beyond Romania’s Carpathian Mountains. Between the 1st and 7th centuries AD, the Romans arrived and departed several times, and numerous invasions of Goths, Avars, Huns, Bulgarians, Magyars, Mongols, and Tartars took place up until the early Middle Ages. The Principality of Moldavia was established in the mid-14th century, bound by the Black Sea and the River Danube in the south, the Carpathian Mountains in the west and the River Dneister to the east.

Crimean Tartars continued their invasions until the 15th century arrival of Ottoman forces and by 1538, the country was a tributary state of the Ottoman Empire while retaining internal autonomy. The Treaty of Bucharest in 1812 saw the Ottoman Empire cede the eastern region of the principality to Russia and its renaming to the Oblast of Moldavia and Bessarabia. The Oblast was initially granted a great degree of autonomy, but between 1828 and 1871, the region saw more and more restrictions as Russification took over.

The 19th century saw Russian-encouraged colonization by Cossacks, Ukrainians and other nationals and just before WWI, thousands of citizens were drafted into the Russian Army. The 1917 Russian Revolution saw the creation of the Moldavian Democratic Republic as part of a federal Russian state, but a year later, a combination of the Romanian and French armies saw independence proclaimed and Moldova united with Romania. Newly communist Russia rejected the changes, seizing power again by 1924 and forming the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, recognized by Nazi Germany in 1930.

By 1941, the Axis invasions resulted in cooperation with the Germans, including the extermination or deportation of almost a million Jewish residents and the drafting of over 250,000 Moldovans into the Soviet Army. The Stalin period from 1940 saw massive deportations of Moldovan nationals, severe persecution, and forced migration of Russians to urban areas. After Stalin’s death, patriot leaders were imprisoned or murdered. The Russian Glasnost and Perestroika movements of the 1980s saw a rise in Moldovan nationalistic fervor, resulting in demands for independence, a mass rally in Chisinau in 1989, and continuing riots.

By 1990, democratic elections were underway, and a Declaration of Sovereignty was signed. Despite an attempted Soviet coup in 1991, Moldova finally declared its independence and a year later was recognized by the United Nations. Although the Communist Party has struggled to retain its hold over the country, Moldova is governed by a coalition of Democratic and Liberal parties. Communism is still the leading influence in the breakaway region of Transnistria.

Moldova’s rich culture goes back to Roman times, with the ancient overlay colored by Byzantine, Magyar, Serbian, Ottoman, Russian, and Soviet influences. From the 19th century onwards, European and French elements were added, forming a varied, lively and resilient lifestyle expressed in traditions, festivals, the arts, music, dance, and literature. Elements of folk culture, such as wood carving and embroidery, are shared with other Balkan countries, but many aspects, such as pottery decoration and the 2,000-year old Doina lyrical songs, are unique to Moldova.

The country’s folk traditions and costumes are highly valued at a national level, and preserved in the capital’s museums, its Republic Dance Company and its choir, Doina, as well as forming part of every Moldovan celebration. The Colinda Christmas tradition of masked and costumed singers, musicians and dancers going from door to door to give performances and receive gifts bears a resemblance to the Christian tradition of carolling, but is rooted in pre-Christian pagan practices.

Wine is deeply rooted in Moldovan culture, with the vineyards some of the oldest in the world, known and appreciated by the Romans and a major source of export revenue during the Middle Ages. The Moldovan Roma community has contributed to the field of music, although it is still regarded as a disadvantaged group. Most traditional cultural events relate to agriculture, religion, folklore, or mythology, and are celebrated with joy and feasting.

- Things To Do

- Attractions

- Food And Restaurants

- Shopping And Leisure

- Transportation

- Travel Tips

- Visas And Vaccinations

- History And Culture

- Festivals And Events

World Wonders

These are the most peaceful countries on the planet, the great outdoors, deserts in bloom: 6 spots for springtime wildflower watching, how to plan a luxury safari to africa, british columbia, yoho national park is the most incredible place you've never heard of.

- Editorial Guidelines

- Submissions

The source for adventure tourism and experiential travel guides.

Why I love Moldova?

My story (by Ana Castrasan)

Why I love Moldova ?

Once upon a time in Europe , a beautiful country has born. It was founded around 1352 by the Transilvanian ruler (voievod) Dragoș, who hunted a wild ox on the banks of the river Moldova. According to one legend, he chose to stay in the land which he named after the river – Moldova.

During the time, Moldova became more beautiful and wanted by big powers as Ottoman Empire , Russian Empire and URSS. That ’s why it’s destiny, history and culture was strongly influenced by them. Although Moldova passed through harsh times, it faced with dignity all the difficulties, and preserved rich traditions and culture for future generations.

Nowadays Moldova boasts a proud history, rich in culture and diversity. Since regaining independence in 1991, Moldova has again shown its individuality and cultural richness. The culture of Moldova represents a large range of cultural activities: literature, theatre, music, fine arts, architecture, cinematography, broadcasting and television, photographic art, design, circus, folk art, archives and libraries, books editing, scientific research, cultural tourism and so on. The cultural heritage of Moldova is abundant with traditions and customs. The traditions in Moldova are primarily related to national music, dances, songs, and food, wine, as well as ornamentation arts and crafts.

There are many reasons why I love this small and beautiful country:

* People * – even if you are at the limit and face the difficult moments you ever had in your life, there you’ll find in any situation someone who will give you a helping hand. People from Moldova are very open and hospitable. They like to have many friends and holidays.

*Traditional cuisine* – Moldova food has a delicious taste and is known for a wide variety of dishes. Once you will taste traditional food, you will never forget savory of zama (chicken noodle soup), sarmale (cabbage rolls) or mamaliga cu brinza (polenta with cheese).

*Wines* – Moldova keeps the old traditions of winemaking. With over 140 wineries, beautiful vineyards and underground wine cellars (some that are as long as 200 km), here you will find a real diversity of red, white and sparkling wine. The wine cellars from Cricova and Milestii Mici offers the possibility to walk in the underground towns of wine.

*Moldovan talents* – Moldova is also known for talented and creative people. Amazing beautiful melodies of Eugen Doga fascinate listeners from all around the world. The waltz which made him famous was selected by Russians last winter in the ceremony of Olympic Games inauguration in Sochi. Eugen Doga’s talent is admitted by UNESCO, as the waltz included as music in the movie “My Sweet and Tender Beast” is called the 4th music masterpiece of the XX-th century.

*Places to visit* – beautiful landscapes created by Mother Nature makes Moldova unique. The hills like people are different in shape and size. The archaeological complex from Orheiul Vechi combines the natural landscape and vestiges of ancient civilizations. The panoramic valley of Orheiul Vechi was nominated for the UNESCO world heritage list.

My country has a soul which is full of people’s kindness and God’s love, that’s why I love Moldova!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Arts & Culture

Get Involved

Autumn 2023

Annual Gala Dinner

Internships

Understanding Moldova’s ethnic dynamics: Minority rights, external influence, and pathways to unity

Elena Cirmizi

This work derives from a final report produced for the Middle East Institute’s Black Sea Program as part of a U.S. State Department Title VIII fellowship.

Moldova is a country with a rich tapestry of multiple ethnic identities and linguistic traditions, where policymakers have long grappled with the complexities of preserving minority rights, fostering national unity, and addressing regional autonomy through engagement with the Gagauz minority (Tudoroiu, 2013, p. 375; Ciobanu, 2013; Deen & Zweers, 2022). The following analysis aims to view these issues from the perspective of the minority’s susceptibility to external political influence. Within the frame of the study, I interviewed 20 local Gagauz and Moldovan experts, including journalists, political activists, educators, and university students. Based on the data obtained during those in-depth interviews, I offer insight into the primary tension points between the Gagauz community and the central Moldovan government that are being exploited by Russian state-sponsored propaganda; based on my conclusions, I aim to influence the local political landscape and offer a range of policy solutions that can bridge the gaps in the country’s ethnic makeup while building resistance to external influence and propaganda. These solutions are centered around supporting educational initiatives, enhancing the quality of local media, and encouraging inter-community dialogue that recognizes the inherent value of linguistic and cultural diversity while also nurturing a shared national identity that transcends ethnic differences.

Gagauzia’s historical legacy

Gagauz-Yeri (Gagauzia) is an autonomous region in the south of Moldova with a predominantly Gagauz (a Turkic ethnic group), Christian Orthodox, but heavily russified population. The region gained its autonomous status in 1994 as a result of negotiations between the Moldovan government and the Gagauz leadership following tensions and conflicts between the two sides in the early 1990s. However, for the past 30 years, the implementation of autonomy has been fraught with legal and social challenges, with debates over the distribution of powers and competencies between the central government and the autonomous region (Thompson, 1998, pp. 128-147; Wöber, 2013, p. 14; Deen & Zweers, 2022, pp. 32-33 ). The majority of the Gagauz community perceives the central government’s actions as a continuous assault on their autonomy rights, eroding them through a range of executive and legislative actions that affect tax, penal, and security policies (Nitup, 2018; Garciu, 2022; Monitorul Official, 2023; Parlament.md, 2023; Yarovaya, 2023), and where the central government raises concerns about preserving national unity and preventing separatist inclinations (RFE, 2014; Yarovaya, 2023). Within this context, the role of Russian media propaganda and the susceptibility of the Gagauz community to its influence is frequently discussed. (Deen & Zweers, 2022, pp 32-33; Title VIII of the MEI Black Sea Program interviews, Chișinău, Comrat, June-July 2023).

Gagauz-Yeri, shaped by its historical, cultural, and linguistic journey, has traditionally maintained a strong alignment with the Russian Federation, translating into Russian influence over societal, political, and economic trajectories in the region. Rooted in cultural and historical foundations, Gagauz identity is linked to memories of being embraced by the Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union, in contrast to a history of enforced assimilation during the Romanian kingdom. This perceived historical context has engendered the Gagauz’s connection with the “Russian world” — a concept actively popularized by Russian propaganda that claims the existence of a shared transborder identity held together by usage of the Russian language or common culture (Kosienkowski, 2021). Within this context, the vast majority of the interviewees in my study expressed concerns about the negative impact that rebroadcasted Russian state media has on Gagauz internal affairs. According to the 2022 Ethnobarometer survey, 73% of local respondents who identify as ethnic Gagauz and 47% who identify as Moldovans consume Russian state-controlled media (Ethnobarometer, 2020). Russian media influence extends to public opinion within Moldova, intensifying existing tensions, framing issues in a way that serve Moscow’s political interests, and fostering favorable sentiments among the population by advocating for closer ties with Russia that allegedly will offer greater benefits for the Gagauz community and Moldova as a whole (McGrath & Jardan, 2022). Most respondents noted that specific tactics encompass discrediting the Moldovan government by depicting it as ineffective, corrupt, overly liberal, or indifferent to minority language rights (Haines, 2015; Perevozkina, 2023, Title VIII of the MEI Black Sea Program interviews, Chișinău, Comrat, June-July 2023). Such portrayals reportedly generate skepticism among Gagauz regarding the government’s policies and add complexity to the existing challenges, making it even more important for the central government to engage in careful, informed dialogue and decision-making rather than ignoring the tensions or acting in a heavy-handed manner (Deen & Zweers, 2022, p. 32).

Relations with the Moldovan state

The discourse concerning language use in the region stands as a pivotal point in the relationship between the Gagauz minority and the Moldovan state and is a key defense against external influence. On the surface, the issue revolves around the acknowledgment, utilization, and advancement of the Gagauz language, encompassing its standing in official contexts and educational institutions. Moldova recognized the Gagauz language as a minority language under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ratified in 2001), taking on the obligation to protect and promote the Gagauz language’s usage and visibility in public life. However, according to a 2010 UNESCO study, the Gagauz language has been identified as “potentially vulnerable” (Garciu, 2023). All Gagauz experts and students interviewed in the course of this research project directly linked their ethnic identity with the language and expressed apprehension about their language’s potential erosion. When queried about potential solutions, Gagauz interviewees grappled with identifying the optimal equilibrium between utilizing Russian as a lingua franca, the state language, and fostering the development of their native tongue, blaming the vulnerability of Gagauz on a lack of educational and media resources, russification, and its limited economic viability beyond the region. They also noted the Moldovan state’s lack of action and interest in supporting autonomy across these domains (see also European Commission, 2022). These concerns are intricately connected in their responses to the simultaneous decades of inaction in supporting state language education in Gagauzia. The lack of Romanian as a second language curriculum, the absence of language teachers, and the dismissal of the appeals from the community for additional support in establishing alternative education channels for the Romanian language led to the proliferation of the Russian language within the region, consequently providing fertile ground for the unprecedented domination of Russian state propaganda within the community.

Recommendations

To contribute to the ongoing dialogue surrounding language usage in Gagauz-Yeri while countering external propaganda efforts, I present several policy initiatives that seek to illuminate a path toward constructive cooperation and the preservation of minority rights within the larger framework of national unity. These programs include a multilingual curriculum, summer language institutes, and in-state and foreign cultural exchange initiatives, and will represent proactive efforts to bridge the linguistic divide, encourage cross-cultural understanding, and build up community resilience.

Multilingual primary education as an implemented education strategy could allow students to receive primary education in dual Romanian and Gagauz (and other local minority languages) to establish appropriate communication patterns during preschool, kindergarten, and elementary school. This approach acknowledges the importance of both languages while ensuring that students from both communities have access to education in their native language. It is necessary to emphasize multilingualism in education instead of bilingualism, and provide Russian- and English-language education as second-language subjects, to ensure that Russian speakers among the regional population do not reject the initiative. This initiative will necessitate dedicated staffing in schools, which would enhance employment opportunities for Gagauz speakers and can be achieved by cooperation between the local and central government, building upon the vast experience of Moldovan-Turkish lyceums in Moldova (Moldpress, 2022).

Language summer institutes could serve as stress-free, immersive environments where children from diverse backgrounds can come together to learn and practice each other’s languages. These initiatives could offer a dynamic learning experience that goes beyond linguistic skills, fostering interpersonal exchange while building relationships and breaking down stereotypes. Similarly, exchange professional programs for youth and educators, such as librarians and school teachers, can facilitate interactions and create opportunities for shared experiences, cultural immersion, and the formation of lasting bonds. Having vast experience with a multilingual population, organizations from the United States could provide valuable resources, expertise, and scholarships for students and teachers.

Promoting cultural and linguistic heritage through the recognition of different minority identities is foundational to developing resilience to external propaganda. A comprehensive historical acknowledgment of traumas and reconciliation initiatives is essential for addressing grievances and fostering empathy. By establishing educational programs, seminars, research, and exhibitions as well as modifying school and university curricula that offer accurate historical representations of minorities, including Gagauz, as an essential part of society, state agencies along with local and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) can facilitate and popularize a nuanced understanding of minorities’ complex pasts. The integration of such narratives into education curricula can effectively build a bridge between the communities, breaking through their divide and making them less vulnerable to propaganda. The U.S., through its educational institutions and local NGOs, could encourage such initiatives and provide financial support for cultural exchange programs. Scholarships, grants, and partnerships with U.S. universities will facilitate the development of inclusive history, language curricula, and research projects. Furthermore, U.S. cultural diplomacy initiatives, such as art exhibitions, performances, and educational events, could be organized in collaboration with local communities to celebrate their uniqueness and emphasize the importance of historical acknowledgment and reconciliation.

Promoting balanced media coverage and ensuring the visibility of the Gagauz community requires a concerted effort to address linguistic, cultural, and regional diversity. Encouraging media organizations to have diverse editorial and journalist teams that include representatives from different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds, including Gagauz, will contribute to fostering more inclusive and impartial news coverage, leading to ethical reporting that actively combats biases and prevents the exploitation of stereotypes. Moreover, supporting the establishment of multiple local news desks in Gagauzia that focus on covering regional news, events, and minority cultural stories will ensure regular coverage of the local activities and human interest stories from the Gagauz community and will give a platform for representation, increase visibility nationally, and help foster a sense of community and pride. Publishing multilingual materials that include both Romanian and Gagauz languages as well as providing subtitles for TV and YouTube content will ensure that Moldovan and Gagauz news segments are available to the entire population while catering to the linguistic needs of the minority community — providing a viable alternative to Russian media outlets. International organizations and the state can provide grants and financial support for local actors to own such initiatives. By implementing these diverse methods, local journalists can be enabled to generate content with the potential to counter Russian propaganda, contributing to the cultivation of an informed and resilient society.

Elena Cirmizi is a Title VIII Black Sea Research Fellow at the Middle East Institute and a Ph.D. candidate at the Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution at George Mason University.

Andrei Pungovschi/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bibliography

Ciobanu, V. (2013). “Tendințe separatiste printre găgăuzi.” [Separatist trends among the Gagauz]. Europa Libera. http://www.europalibera.org/content/article/25069011.html

Deen, B. and W. Zweers. (2022). Walking the tightrope towards the EU. Clingendael Report. Netherlands Institute of International Relations.

Ethnobarometer Moldova – 2020. (2020). CIVIS Centre. OSCE. pp. 59-61. https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/0/7/505306_0.pdf

European Commission. (2022). “Opinion on Moldova’s application for membership of the European Union,” from June 16. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/enlargement/moldova/

Garciu, P. (2022). “Russian Propaganda Dominates Moldova’s Gagauzia.” Institute for War & Peace Reporting. https://iwpr.net/global-voices/russian-propaganda-dominates-moldovas-ga… .

Garciu, P. (2023). “Moldova: Gagauz language lags behind Russian.” Institute for War & Peace Reporting. https://iwpr.net/global-voices/moldova-gagauz-language-lags-behind-russ…

Haines, J.R. (2015). “A quarrel in a faraway country: the rise of a Budzhak People’s Republic.” Foreign Policy Research Institute. https://www.fpri.org/article/2015/04/a-quarrel-in-a-far-away-country-th…

Kosienkowski, M. (2021). The Russian World as a legitimation strategy outside Russia: the case of Gagauzia. Eurasian Geography and Economics 62. No. 3.

Moldpress. (2022). PM visits Moldovan-Turkish theoretical lyceum from Congaz settlement of Gagauzia. https://www.moldpres.md/en/news/2022/10/21/22007943

Monitorul Oficial. (2023). No. 53-56, pp. 11-12.

MsGrath, S. and C. Jardan. (2022). “Moldova suspends 6 TV channels over alleged misinformation.” AP News . https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-public-opinion-moldova-741940…

Nitup, R. (2018). “Gagauzia: Moldavskie oligarhi protiv “russkih tankov” [Gaguzia: Moldovan oligarchs against Russian tanks.]. New Day News. https://newdaynews.ru/kishinev/627636.html . Accessed 04.02.2018.

Parlament.md. (2023). Proiectul de lege pentru modificarea art. 6 din Codul fiscal nr. 1163/1997. https://www.parlament.md/ProcesulLegislativ/Proiectedeactelegislative/t…

Perevozkina, M. (2023). “Politolog Soin otsenil veroyatnost’ otdeleniya Gagauzii ot Moldovy.” [Political scientist Soin assessed the likelihood of Gagauzia secession from Moldova]. Moskovskij Komsomolets.

Radio Free Europe. (2014). “Gagauzia voters reject closer EU ties for Moldova.” Radio Liberty. Moldovan Service. https://www.rferl.org/a/moldova-gagauz-referendum-counting/25251251.html

Thompson, P. (1998). “The Gagauz in Moldova and their road to autonomy.” In Managing diversity in plurar societies – minorities, migration and nation-building in post-Communist Europe. M. Opalski. (Ed.) Nepean Forum Eastern Europe. 128-147.

Tudoroiu, T. (2013). Unfreezing failed frozen conflicts: A post-Soviet case study. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 24 (3), 375-396.

Wöber, S. (2013). Making or breaking the Republic of Moldova? The autonomy of Gagauzia. European Diversity and Autonomy Papers. p.14.

Yarovaya, G. (2024). “Subject to the criminal code of the Republic of Moldova: Konstantinov filed a complaint with the prosecutor’s office for separatist statements.” Rupor.md. https://rupor.md/podpadaet-pod-uk-rm-na-konstantinova-podali-zhalobu-v-…

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click her e .

Search form

In the Republic of Moldova there are many ethno-cultural associations. 18 minorities – the Ukrainians, Russians, Bulgarians, Gagauzians, Jews, Byelorussians, Poles, Germans, Gypsies, Greeks, Lithuanians, Armenians, Azerbaijanians, Tatars, Chuvashs, Italians, Koreans, Uzbeks – have associations which operate under the form of communities, societies, unions, centers, cultural foundations etc. By virtue of the principle of equality and universality of cultural legislation, the ethnic minorities have the possibility to develop their traditional culture and national art. In Chisinau there is the Russian Dramatic Theatre „A.P.Cehov”; in Ceadir-Lunga (ATU Gagauzia) – the Gagauzian Dramatic Theatre „Mihail Cekir”; in Taraclia – the Theater of the Bulgarians from Bessarabia „Olimpii Panov”.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Examining the foreign policy attitudes in Moldova

Monica Răileanu Szeles

Institute for Economic Forecasting, Transilvania University of Brasov, Brasov, Romania

Associated Data

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

This paper aims to examine the correlates of foreign policy attitudes in Moldova by a multilevel analysis, and to also reveal some characteristics of the Moldova’s difficult geopolitical and economic context, such as the ethnical conflicts and poverty. A set of four foreign policy attitudes are explained upon individual- and regional level socio-economic and demographic correlates, of which poverty is the main focus, being represented here by several objective, subjective, uni- and multidimensional indicators. An indicator of deprivation is derived from a group of poverty indicators by the method Item Response Theory. Deprivation, subjective poverty, ethnicity and the Russian media influence are found to be associated with negative attitudes toward all foreign policies, while satisfaction with economic conditions in the country and a positive attitude toward refugees are both associated with positive attitudes toward all foreign policies.

Introduction

The Republic of Moldova is situated in South-Eastern Europe, being at the confluence of Central Europe, Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and Balkans. The geographical position and the ethnical conflict embracing multiple forms has posed serious threats for this small multi-nation country, which had to face complex geopolitical challenges after the failure of the communist regime. In addition, the “multi-vector” external policy, permanently oscillating between East (European Union) and West (CIS countries), often characterized as “ambiguous, inconsistent and dual” [ 1 ], was not able to manage over time the ethnical and political conflicts.

The collapse of the former Soviet Union, Moldova’s independence, the language law recognizing Romanian as the official language since 2013, the conflicts in Transnistria and Gagauzia, the perspective of unification with Romania, the Russia’s influence and more recently the alternative of European Union membership are just few of the major political milestones that Moldova has encountered in the last 30 years.

The Moldova’s perspective to join the EU could open a new chapter into its long term economic development. But the paradox is that Moldova is the only European country where European integration has progressively become less popular despite the pro-European government [ 2 ].

The closeness of Moldova to the European Union has historically been associated with the Moldova’s fluctuant political regime. However, the struggle between the pro-European and pro-Russian parties has stacked for a long time Moldova between its neighbours, Romania and Ukraine. The European Union enlargement to the East, together with the emergence and development of Moldovan pro-European forces and opinions, should have been accelerated the EU membership. This hasn’t happened, and moreover, the public support for the European integration has continuously declined after 2009. The failure of authorities to combat corruption, to increase the standard of living, and to prevent the exodus of the working age population explain the decline of the EU popularity because the population associates the pro-European government with the European integration process [ 2 ].

In Moldova, the ethnic identity has risen serious debates, as well as an overwhelming and ethno-political conflict, whose main actors are the Moldovans, Gagauzians and Romanians sharing one common country. According to the 2014 Census, the most important ethnic groups in Moldova are Romanians (7%), Ukrainians (6.6%), Gagauz (4.6%), Russians (4.1%) and Bulgarians (1.9%). After the Soviet Union disintegration, the largest group of Gagauzians form the Autonomous Territorial Unit (ATU) in Southern Moldova. Apart from other ethnic minorities in Moldova, Gagauz people have no other country bearing their name. The 1994 ATU autonomy law ensured that ATU will not become a part of Romania in case that Moldova will merge with Romania. This has quieted down Gagauzians for a while, but still ethnical and political tensions fuel fears of losing their autonomy.

The inconsistent foreign policy, the low public interest for current political issues, and the economic, social and political problems that Moldova encountered in the transition from communism to democracy [ 3 ], have downturned the long term economic development of Moldova, and have also deteriorated the strategic partnerships with neighbouring countries. To a much higher extent than other countries, the economic development of Moldova is significantly influenced by geopolitical forces and strategic partnerships, so that the foreign policy represents a fundamental pillar of Moldova’s long term sustainable development.

Despite the rapid pro-poor economic growth of 5 percent annually since 2000, which resulted in a significant progress of poverty reduction from 68 to 11.4 percent between 2000 and 2014, Moldova remains one of the poorest countries in the region with 41% of population living below the threshold of 5 USD a day (2005 PPP) in 2014. I mention at this step that in the framework of economic theory the economic growth rate is considered to be pro-poor if it’s the result of national policies aimed to use it for the benefit of poor people. This is the case here, as it resulted in the reduction of poverty. Moreover, the social disequilibria significantly inflate the negative impact of political instability and ethnical conflicts on economic development, which is strongly related to foreign policy in the case of Moldova. In this broad context, understanding what really lies behind the foreign policy attitudes, and in particular finding to what extent they are also influenced by poverty, ethnic tensions and regional patterns, allows enhancing the connection between public opinion and foreign policy, which could be ultimately regarded as an important assessment tool in measuring political commitment.

This paper intends to fill a gap in the literature by examining the foreign policy attitudes in Moldova, from a regional perspective. To capture not only the impact of individual-level characteristics on the foreign policy attitudes, but also the influence of geographical peculiarities, a multilevel model is used in the empirical section with individuals nested in districts. This multilevel approach reflects the regional perspective of our study.

The paper adds new empirical evidence to the literature which relies almost exclusively on studies of American foreign policy opinions [ 4 ], but it also contributes to the literature in other ways. First, it provides a regional perspective to the analysis of foreign policy attitudes, which perfectly fits the challenging Moldova’s ethno-geopolitical context. Second, it relates public opinions on foreign policy to poverty by a multidimensional approach, as to also address the social issues in Moldova—one of the poorest countries in Europe. Upon our knowledge, the link between foreign policy attitudes and poverty has not been explored so far. To accommodate the regional dimension of the dataset, random intercept logit models are used in the empirical section, where the regional foreign policy attitudes are explained upon regional- and individual level characteristics. In addition, the Item Response Theory is used to construct a scale of deprivation.

The paper is structured as follows: After “Introduction”, the “Literature Review” underlines the most important contributions to the literature. The section of “Methodology” presents the two methods used in the empirical analysis, while “Data” provides the description of the data and the economic and social context in Moldova. The “Empirical analysis” includes the construction of the multidimensional scale of deprivation, and the analysis of foreign policy attitudes. The last section concludes and formulates policy recommendations.

Literature review