Qualitative Study

Affiliations.

- 1 University of Nebraska Medical Center

- 2 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting

- 3 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting/McLaren Macomb Hospital

- PMID: 29262162

- Bookshelf ID: NBK470395

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervene or introduce treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypotheses as well as further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a stand-alone study, purely relying on qualitative data or it could be part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. This review introduces the readers to some basic concepts, definitions, terminology, and application of qualitative research.

Qualitative research at its core, ask open-ended questions whose answers are not easily put into numbers such as ‘how’ and ‘why’. Due to the open-ended nature of the research questions at hand, qualitative research design is often not linear in the same way quantitative design is. One of the strengths of qualitative research is its ability to explain processes and patterns of human behavior that can be difficult to quantify. Phenomena such as experiences, attitudes, and behaviors can be difficult to accurately capture quantitatively, whereas a qualitative approach allows participants themselves to explain how, why, or what they were thinking, feeling, and experiencing at a certain time or during an event of interest. Quantifying qualitative data certainly is possible, but at its core, qualitative data is looking for themes and patterns that can be difficult to quantify and it is important to ensure that the context and narrative of qualitative work are not lost by trying to quantify something that is not meant to be quantified.

However, while qualitative research is sometimes placed in opposition to quantitative research, where they are necessarily opposites and therefore ‘compete’ against each other and the philosophical paradigms associated with each, qualitative and quantitative work are not necessarily opposites nor are they incompatible. While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites, and they are certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined that there is a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated together.

Examples of Qualitative Research Approaches

Ethnography

Ethnography as a research design has its origins in social and cultural anthropology, and involves the researcher being directly immersed in the participant’s environment. Through this immersion, the ethnographer can use a variety of data collection techniques with the aim of being able to produce a comprehensive account of the social phenomena that occurred during the research period. That is to say, the researcher’s aim with ethnography is to immerse themselves into the research population and come out of it with accounts of actions, behaviors, events, etc. through the eyes of someone involved in the population. Direct involvement of the researcher with the target population is one benefit of ethnographic research because it can then be possible to find data that is otherwise very difficult to extract and record.

Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory is the “generation of a theoretical model through the experience of observing a study population and developing a comparative analysis of their speech and behavior.” As opposed to quantitative research which is deductive and tests or verifies an existing theory, grounded theory research is inductive and therefore lends itself to research that is aiming to study social interactions or experiences. In essence, Grounded Theory’s goal is to explain for example how and why an event occurs or how and why people might behave a certain way. Through observing the population, a researcher using the Grounded Theory approach can then develop a theory to explain the phenomena of interest.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is defined as the “study of the meaning of phenomena or the study of the particular”. At first glance, it might seem that Grounded Theory and Phenomenology are quite similar, but upon careful examination, the differences can be seen. At its core, phenomenology looks to investigate experiences from the perspective of the individual. Phenomenology is essentially looking into the ‘lived experiences’ of the participants and aims to examine how and why participants behaved a certain way, from their perspective . Herein lies one of the main differences between Grounded Theory and Phenomenology. Grounded Theory aims to develop a theory for social phenomena through an examination of various data sources whereas Phenomenology focuses on describing and explaining an event or phenomena from the perspective of those who have experienced it.

Narrative Research

One of qualitative research’s strengths lies in its ability to tell a story, often from the perspective of those directly involved in it. Reporting on qualitative research involves including details and descriptions of the setting involved and quotes from participants. This detail is called ‘thick’ or ‘rich’ description and is a strength of qualitative research. Narrative research is rife with the possibilities of ‘thick’ description as this approach weaves together a sequence of events, usually from just one or two individuals, in the hopes of creating a cohesive story, or narrative. While it might seem like a waste of time to focus on such a specific, individual level, understanding one or two people’s narratives for an event or phenomenon can help to inform researchers about the influences that helped shape that narrative. The tension or conflict of differing narratives can be “opportunities for innovation”.

Research Paradigm

Research paradigms are the assumptions, norms, and standards that underpin different approaches to research. Essentially, research paradigms are the ‘worldview’ that inform research. It is valuable for researchers, both qualitative and quantitative, to understand what paradigm they are working within because understanding the theoretical basis of research paradigms allows researchers to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the approach being used and adjust accordingly. Different paradigms have different ontology and epistemologies . Ontology is defined as the "assumptions about the nature of reality” whereas epistemology is defined as the “assumptions about the nature of knowledge” that inform the work researchers do. It is important to understand the ontological and epistemological foundations of the research paradigm researchers are working within to allow for a full understanding of the approach being used and the assumptions that underpin the approach as a whole. Further, it is crucial that researchers understand their own ontological and epistemological assumptions about the world in general because their assumptions about the world will necessarily impact how they interact with research. A discussion of the research paradigm is not complete without describing positivist, postpositivist, and constructivist philosophies.

Positivist vs Postpositivist

To further understand qualitative research, we need to discuss positivist and postpositivist frameworks. Positivism is a philosophy that the scientific method can and should be applied to social as well as natural sciences. Essentially, positivist thinking insists that the social sciences should use natural science methods in its research which stems from positivist ontology that there is an objective reality that exists that is fully independent of our perception of the world as individuals. Quantitative research is rooted in positivist philosophy, which can be seen in the value it places on concepts such as causality, generalizability, and replicability.

Conversely, postpositivists argue that social reality can never be one hundred percent explained but it could be approximated. Indeed, qualitative researchers have been insisting that there are “fundamental limits to the extent to which the methods and procedures of the natural sciences could be applied to the social world” and therefore postpositivist philosophy is often associated with qualitative research. An example of positivist versus postpositivist values in research might be that positivist philosophies value hypothesis-testing, whereas postpositivist philosophies value the ability to formulate a substantive theory.

Constructivist

Constructivism is a subcategory of postpositivism. Most researchers invested in postpositivist research are constructivist as well, meaning they think there is no objective external reality that exists but rather that reality is constructed. Constructivism is a theoretical lens that emphasizes the dynamic nature of our world. “Constructivism contends that individuals’ views are directly influenced by their experiences, and it is these individual experiences and views that shape their perspective of reality”. Essentially, Constructivist thought focuses on how ‘reality’ is not a fixed certainty and experiences, interactions, and backgrounds give people a unique view of the world. Constructivism contends, unlike in positivist views, that there is not necessarily an ‘objective’ reality we all experience. This is the ‘relativist’ ontological view that reality and the world we live in are dynamic and socially constructed. Therefore, qualitative scientific knowledge can be inductive as well as deductive.”

So why is it important to understand the differences in assumptions that different philosophies and approaches to research have? Fundamentally, the assumptions underpinning the research tools a researcher selects provide an overall base for the assumptions the rest of the research will have and can even change the role of the researcher themselves. For example, is the researcher an ‘objective’ observer such as in positivist quantitative work? Or is the researcher an active participant in the research itself, as in postpositivist qualitative work? Understanding the philosophical base of the research undertaken allows researchers to fully understand the implications of their work and their role within the research, as well as reflect on their own positionality and bias as it pertains to the research they are conducting.

Data Sampling

The better the sample represents the intended study population, the more likely the researcher is to encompass the varying factors at play. The following are examples of participant sampling and selection:

Purposive sampling- selection based on the researcher’s rationale in terms of being the most informative.

Criterion sampling-selection based on pre-identified factors.

Convenience sampling- selection based on availability.

Snowball sampling- the selection is by referral from other participants or people who know potential participants.

Extreme case sampling- targeted selection of rare cases.

Typical case sampling-selection based on regular or average participants.

Data Collection and Analysis

Qualitative research uses several techniques including interviews, focus groups, and observation. [1] [2] [3] Interviews may be unstructured, with open-ended questions on a topic and the interviewer adapts to the responses. Structured interviews have a predetermined number of questions that every participant is asked. It is usually one on one and is appropriate for sensitive topics or topics needing an in-depth exploration. Focus groups are often held with 8-12 target participants and are used when group dynamics and collective views on a topic are desired. Researchers can be a participant-observer to share the experiences of the subject or a non-participant or detached observer.

While quantitative research design prescribes a controlled environment for data collection, qualitative data collection may be in a central location or in the environment of the participants, depending on the study goals and design. Qualitative research could amount to a large amount of data. Data is transcribed which may then be coded manually or with the use of Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software or CAQDAS such as ATLAS.ti or NVivo.

After the coding process, qualitative research results could be in various formats. It could be a synthesis and interpretation presented with excerpts from the data. Results also could be in the form of themes and theory or model development.

Dissemination

To standardize and facilitate the dissemination of qualitative research outcomes, the healthcare team can use two reporting standards. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research or COREQ is a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is a checklist covering a wider range of qualitative research.

Examples of Application

Many times a research question will start with qualitative research. The qualitative research will help generate the research hypothesis which can be tested with quantitative methods. After the data is collected and analyzed with quantitative methods, a set of qualitative methods can be used to dive deeper into the data for a better understanding of what the numbers truly mean and their implications. The qualitative methods can then help clarify the quantitative data and also help refine the hypothesis for future research. Furthermore, with qualitative research researchers can explore subjects that are poorly studied with quantitative methods. These include opinions, individual's actions, and social science research.

A good qualitative study design starts with a goal or objective. This should be clearly defined or stated. The target population needs to be specified. A method for obtaining information from the study population must be carefully detailed to ensure there are no omissions of part of the target population. A proper collection method should be selected which will help obtain the desired information without overly limiting the collected data because many times, the information sought is not well compartmentalized or obtained. Finally, the design should ensure adequate methods for analyzing the data. An example may help better clarify some of the various aspects of qualitative research.

A researcher wants to decrease the number of teenagers who smoke in their community. The researcher could begin by asking current teen smokers why they started smoking through structured or unstructured interviews (qualitative research). The researcher can also get together a group of current teenage smokers and conduct a focus group to help brainstorm factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke (qualitative research).

In this example, the researcher has used qualitative research methods (interviews and focus groups) to generate a list of ideas of both why teens start to smoke as well as factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke. Next, the researcher compiles this data. The research found that, hypothetically, peer pressure, health issues, cost, being considered “cool,” and rebellious behavior all might increase or decrease the likelihood of teens starting to smoke.

The researcher creates a survey asking teen participants to rank how important each of the above factors is in either starting smoking (for current smokers) or not smoking (for current non-smokers). This survey provides specific numbers (ranked importance of each factor) and is thus a quantitative research tool.

The researcher can use the results of the survey to focus efforts on the one or two highest-ranked factors. Let us say the researcher found that health was the major factor that keeps teens from starting to smoke, and peer pressure was the major factor that contributed to teens to start smoking. The researcher can go back to qualitative research methods to dive deeper into each of these for more information. The researcher wants to focus on how to keep teens from starting to smoke, so they focus on the peer pressure aspect.

The researcher can conduct interviews and/or focus groups (qualitative research) about what types and forms of peer pressure are commonly encountered, where the peer pressure comes from, and where smoking first starts. The researcher hypothetically finds that peer pressure often occurs after school at the local teen hangouts, mostly the local park. The researcher also hypothetically finds that peer pressure comes from older, current smokers who provide the cigarettes.

The researcher could further explore this observation made at the local teen hangouts (qualitative research) and take notes regarding who is smoking, who is not, and what observable factors are at play for peer pressure of smoking. The researcher finds a local park where many local teenagers hang out and see that a shady, overgrown area of the park is where the smokers tend to hang out. The researcher notes the smoking teenagers buy their cigarettes from a local convenience store adjacent to the park where the clerk does not check identification before selling cigarettes. These observations fall under qualitative research.

If the researcher returns to the park and counts how many individuals smoke in each region of the park, this numerical data would be quantitative research. Based on the researcher's efforts thus far, they conclude that local teen smoking and teenagers who start to smoke may decrease if there are fewer overgrown areas of the park and the local convenience store does not sell cigarettes to underage individuals.

The researcher could try to have the parks department reassess the shady areas to make them less conducive to the smokers or identify how to limit the sales of cigarettes to underage individuals by the convenience store. The researcher would then cycle back to qualitative methods of asking at-risk population their perceptions of the changes, what factors are still at play, as well as quantitative research that includes teen smoking rates in the community, the incidence of new teen smokers, among others.

Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

- Introduction

- Issues of Concern

- Clinical Significance

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

- Review Questions

Publication types

- Study Guide

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

686k Accesses

268 Citations

89 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

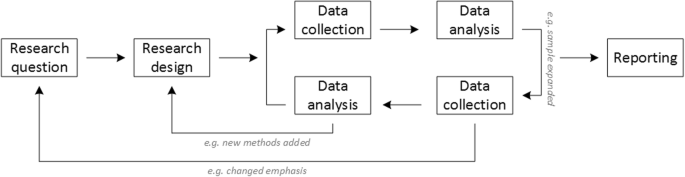

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

Data collection

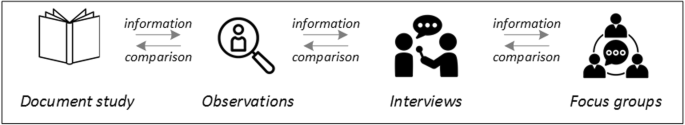

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper describe qualitative interviews as “an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal” [ 19 ]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person’s subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [ 13 ]. Interviews can be distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (e.g. free conversation or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [ 2 , 13 ]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the use of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the broad areas of interest, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [ 19 ]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide can be derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, e.g. document study or observations. The topic list is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection process as the interviewer learns more about the field [ 20 ]. Across interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.g. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns about the total length of the interview) [ 20 ]. Qualitative interviews are usually not conducted in written format as it impedes on the interactive component of the method [ 20 ]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and to be taken up by the researcher. This can also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can only measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; but sometimes it is only feasible or acceptable for the interviewer to take written notes [ 14 , 16 , 20 ].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants’ expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people behave in certain ways [ 1 ]. Focus groups usually consist of 6–8 people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or “script” [ 21 ]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-verbal aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [ 21 ]. Depending on researchers’ and participants’ preferences, the discussions can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [ 21 ]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [ 21 ]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and inexpensive method to gain access to information on interactions in a given group, i.e. “the sharing and comparing” among participants [ 21 ]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, as do those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups can be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disclose in a group setting [ 13 ]. Moreover, attention must be paid to the emergence of “groupthink” as well as possible power dynamics within the group, e.g. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the “right” method

As explained above, the school of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This means that each choice of single or combined methods has to be based on the research question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the chosen method can accomplish this – i.e. the “fit” between question and method [ 14 ]. It is necessary for these decisions to be documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.

Let us assume that our research aim is to examine the (clinical) processes around acute endovascular treatment (EVT), from the patient’s arrival at the emergency room to recanalization, with the aim to identify possible causes for delay and/or other causes for sub-optimal treatment outcome. As a first step, we could conduct a document study of the relevant standard operating procedures (SOPs) for this phase of care – are they up-to-date and in line with current guidelines? Do they contain any mistakes, irregularities or uncertainties that could cause delays or other problems? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the results have to be interpreted based on what they are: a written outline of what care processes in this hospital should look like. If we want to know what they actually look like in practice, we can conduct observations of the processes described in the SOPs. These results can (and should) be analysed in themselves, but also in comparison to the results of the document analysis, especially as regards relevant discrepancies. Do the SOPs outline specific tests for which no equipment can be observed or tasks to be performed by specialized nurses who are not present during the observation? It might also be possible that the written SOP is outdated, but the actual care provided is in line with current best practice. In order to find out why these discrepancies exist, it can be useful to conduct interviews. Are the physicians simply not aware of the SOPs (because their existence is limited to the hospital’s intranet) or do they actively disagree with them or does the infrastructure make it impossible to provide the care as described? Another rationale for adding interviews is that some situations (or all of their possible variations for different patient groups or the day, night or weekend shift) cannot practically or ethically be observed. In this case, it is possible to ask those involved to report on their actions – being aware that this is not the same as the actual observation. A senior physician’s or hospital manager’s description of certain situations might differ from a nurse’s or junior physician’s one, maybe because they intentionally misrepresent facts or maybe because different aspects of the process are visible or important to them. In some cases, it can also be relevant to consider to whom the interviewee is disclosing this information – someone they trust, someone they are otherwise not connected to, or someone they suspect or are aware of being in a potentially “dangerous” power relationship to them. Lastly, a focus group could be conducted with representatives of the relevant professional groups to explore how and why exactly they provide care around EVT. The discussion might reveal discrepancies (between SOPs and actual care or between different physicians) and motivations to the researchers as well as to the focus group members that they might not have been aware of themselves. For the focus group to deliver relevant information, attention has to be paid to its composition and conduct, for example, to make sure that all participants feel safe to disclose sensitive or potentially problematic information or that the discussion is not dominated by (senior) physicians only. The resulting combination of data collection methods is shown in Fig. 2 .

Possible combination of data collection methods

Attributions for icons: “Book” by Serhii Smirnov, “Interview” by Adrien Coquet, FR, “Magnifying Glass” by anggun, ID, “Business communication” by Vectors Market; all from the Noun Project

The combination of multiple data source as described for this example can be referred to as “triangulation”, in which multiple measurements are carried out from different angles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study [ 22 , 23 ].

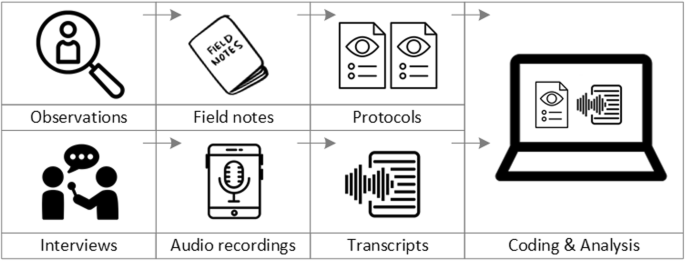

Data analysis

To analyse the data collected through observations, interviews and focus groups these need to be transcribed into protocols and transcripts (see Fig. 3 ). Interviews and focus groups can be transcribed verbatim , with or without annotations for behaviour (e.g. laughing, crying, pausing) and with or without phonetic transcription of dialects and filler words, depending on what is expected or known to be relevant for the analysis. In the next step, the protocols and transcripts are coded , that is, marked (or tagged, labelled) with one or more short descriptors of the content of a sentence or paragraph [ 2 , 15 , 23 ]. Jansen describes coding as “connecting the raw data with “theoretical” terms” [ 20 ]. In a more practical sense, coding makes raw data sortable. This makes it possible to extract and examine all segments describing, say, a tele-neurology consultation from multiple data sources (e.g. SOPs, emergency room observations, staff and patient interview). In a process of synthesis and abstraction, the codes are then grouped, summarised and/or categorised [ 15 , 20 ]. The end product of the coding or analysis process is a descriptive theory of the behavioural pattern under investigation [ 20 ]. The coding process is performed using qualitative data management software, the most common ones being InVivo, MaxQDA and Atlas.ti. It should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) [ 14 ].

From data collection to data analysis

Attributions for icons: see Fig. 2 , also “Speech to text” by Trevor Dsouza, “Field Notes” by Mike O’Brien, US, “Voice Record” by ProSymbols, US, “Inspection” by Made, AU, and “Cloud” by Graphic Tigers; all from the Noun Project

How to report qualitative research?

Protocols of qualitative research can be published separately and in advance of the study results. However, the aim is not the same as in RCT protocols, i.e. to pre-define and set in stone the research questions and primary or secondary endpoints. Rather, it is a way to describe the research methods in detail, which might not be possible in the results paper given journals’ word limits. Qualitative research papers are usually longer than their quantitative counterparts to allow for deep understanding and so-called “thick description”. In the methods section, the focus is on transparency of the methods used, including why, how and by whom they were implemented in the specific study setting, so as to enable a discussion of whether and how this may have influenced data collection, analysis and interpretation. The results section usually starts with a paragraph outlining the main findings, followed by more detailed descriptions of, for example, the commonalities, discrepancies or exceptions per category [ 20 ]. Here it is important to support main findings by relevant quotations, which may add information, context, emphasis or real-life examples [ 20 , 23 ]. It is subject to debate in the field whether it is relevant to state the exact number or percentage of respondents supporting a certain statement (e.g. “Five interviewees expressed negative feelings towards XYZ”) [ 21 ].

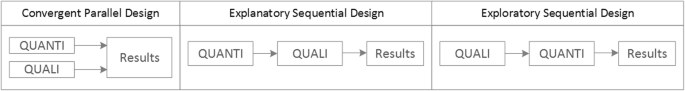

How to combine qualitative with quantitative research?

Qualitative methods can be combined with other methods in multi- or mixed methods designs, which “[employ] two or more different methods [ …] within the same study or research program rather than confining the research to one single method” [ 24 ]. Reasons for combining methods can be diverse, including triangulation for corroboration of findings, complementarity for illustration and clarification of results, expansion to extend the breadth and range of the study, explanation of (unexpected) results generated with one method with the help of another, or offsetting the weakness of one method with the strength of another [ 1 , 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The resulting designs can be classified according to when, why and how the different quantitative and/or qualitative data strands are combined. The three most common types of mixed method designs are the convergent parallel design , the explanatory sequential design and the exploratory sequential design. The designs with examples are shown in Fig. 4 .

Three common mixed methods designs

In the convergent parallel design, a qualitative study is conducted in parallel to and independently of a quantitative study, and the results of both studies are compared and combined at the stage of interpretation of results. Using the above example of EVT provision, this could entail setting up a quantitative EVT registry to measure process times and patient outcomes in parallel to conducting the qualitative research outlined above, and then comparing results. Amongst other things, this would make it possible to assess whether interview respondents’ subjective impressions of patients receiving good care match modified Rankin Scores at follow-up, or whether observed delays in care provision are exceptions or the rule when compared to door-to-needle times as documented in the registry. In the explanatory sequential design, a quantitative study is carried out first, followed by a qualitative study to help explain the results from the quantitative study. This would be an appropriate design if the registry alone had revealed relevant delays in door-to-needle times and the qualitative study would be used to understand where and why these occurred, and how they could be improved. In the exploratory design, the qualitative study is carried out first and its results help informing and building the quantitative study in the next step [ 26 ]. If the qualitative study around EVT provision had shown a high level of dissatisfaction among the staff members involved, a quantitative questionnaire investigating staff satisfaction could be set up in the next step, informed by the qualitative study on which topics dissatisfaction had been expressed. Amongst other things, the questionnaire design would make it possible to widen the reach of the research to more respondents from different (types of) hospitals, regions, countries or settings, and to conduct sub-group analyses for different professional groups.

How to assess qualitative research?

A variety of assessment criteria and lists have been developed for qualitative research, ranging in their focus and comprehensiveness [ 14 , 17 , 27 ]. However, none of these has been elevated to the “gold standard” in the field. In the following, we therefore focus on a set of commonly used assessment criteria that, from a practical standpoint, a researcher can look for when assessing a qualitative research report or paper.

Assessors should check the authors’ use of and adherence to the relevant reporting checklists (e.g. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)) to make sure all items that are relevant for this type of research are addressed [ 23 , 28 ]. Discussions of quantitative measures in addition to or instead of these qualitative measures can be a sign of lower quality of the research (paper). Providing and adhering to a checklist for qualitative research contributes to an important quality criterion for qualitative research, namely transparency [ 15 , 17 , 23 ].

Reflexivity

While methodological transparency and complete reporting is relevant for all types of research, some additional criteria must be taken into account for qualitative research. This includes what is called reflexivity, i.e. sensitivity to the relationship between the researcher and the researched, including how contact was established and maintained, or the background and experience of the researcher(s) involved in data collection and analysis. Depending on the research question and population to be researched this can be limited to professional experience, but it may also include gender, age or ethnicity [ 17 , 27 ]. These details are relevant because in qualitative research, as opposed to quantitative research, the researcher as a person cannot be isolated from the research process [ 23 ]. It may influence the conversation when an interviewed patient speaks to an interviewer who is a physician, or when an interviewee is asked to discuss a gynaecological procedure with a male interviewer, and therefore the reader must be made aware of these details [ 19 ].

Sampling and saturation

The aim of qualitative sampling is for all variants of the objects of observation that are deemed relevant for the study to be present in the sample “ to see the issue and its meanings from as many angles as possible” [ 1 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 27 ] , and to ensure “information-richness [ 15 ]. An iterative sampling approach is advised, in which data collection (e.g. five interviews) is followed by data analysis, followed by more data collection to find variants that are lacking in the current sample. This process continues until no new (relevant) information can be found and further sampling becomes redundant – which is called saturation [ 1 , 15 ] . In other words: qualitative data collection finds its end point not a priori , but when the research team determines that saturation has been reached [ 29 , 30 ].

This is also the reason why most qualitative studies use deliberate instead of random sampling strategies. This is generally referred to as “ purposive sampling” , in which researchers pre-define which types of participants or cases they need to include so as to cover all variations that are expected to be of relevance, based on the literature, previous experience or theory (i.e. theoretical sampling) [ 14 , 20 ]. Other types of purposive sampling include (but are not limited to) maximum variation sampling, critical case sampling or extreme or deviant case sampling [ 2 ]. In the above EVT example, a purposive sample could include all relevant professional groups and/or all relevant stakeholders (patients, relatives) and/or all relevant times of observation (day, night and weekend shift).

Assessors of qualitative research should check whether the considerations underlying the sampling strategy were sound and whether or how researchers tried to adapt and improve their strategies in stepwise or cyclical approaches between data collection and analysis to achieve saturation [ 14 ].

Good qualitative research is iterative in nature, i.e. it goes back and forth between data collection and analysis, revising and improving the approach where necessary. One example of this are pilot interviews, where different aspects of the interview (especially the interview guide, but also, for example, the site of the interview or whether the interview can be audio-recorded) are tested with a small number of respondents, evaluated and revised [ 19 ]. In doing so, the interviewer learns which wording or types of questions work best, or which is the best length of an interview with patients who have trouble concentrating for an extended time. Of course, the same reasoning applies to observations or focus groups which can also be piloted.

Ideally, coding should be performed by at least two researchers, especially at the beginning of the coding process when a common approach must be defined, including the establishment of a useful coding list (or tree), and when a common meaning of individual codes must be established [ 23 ]. An initial sub-set or all transcripts can be coded independently by the coders and then compared and consolidated after regular discussions in the research team. This is to make sure that codes are applied consistently to the research data.

Member checking

Member checking, also called respondent validation , refers to the practice of checking back with study respondents to see if the research is in line with their views [ 14 , 27 ]. This can happen after data collection or analysis or when first results are available [ 23 ]. For example, interviewees can be provided with (summaries of) their transcripts and asked whether they believe this to be a complete representation of their views or whether they would like to clarify or elaborate on their responses [ 17 ]. Respondents’ feedback on these issues then becomes part of the data collection and analysis [ 27 ].

Stakeholder involvement

In those niches where qualitative approaches have been able to evolve and grow, a new trend has seen the inclusion of patients and their representatives not only as study participants (i.e. “members”, see above) but as consultants to and active participants in the broader research process [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. The underlying assumption is that patients and other stakeholders hold unique perspectives and experiences that add value beyond their own single story, making the research more relevant and beneficial to researchers, study participants and (future) patients alike [ 34 , 35 ]. Using the example of patients on or nearing dialysis, a recent scoping review found that 80% of clinical research did not address the top 10 research priorities identified by patients and caregivers [ 32 , 36 ]. In this sense, the involvement of the relevant stakeholders, especially patients and relatives, is increasingly being seen as a quality indicator in and of itself.

How not to assess qualitative research

The above overview does not include certain items that are routine in assessments of quantitative research. What follows is a non-exhaustive, non-representative, experience-based list of the quantitative criteria often applied to the assessment of qualitative research, as well as an explanation of the limited usefulness of these endeavours.

Protocol adherence

Given the openness and flexibility of qualitative research, it should not be assessed by how well it adheres to pre-determined and fixed strategies – in other words: its rigidity. Instead, the assessor should look for signs of adaptation and refinement based on lessons learned from earlier steps in the research process.

Sample size

For the reasons explained above, qualitative research does not require specific sample sizes, nor does it require that the sample size be determined a priori [ 1 , 14 , 27 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Sample size can only be a useful quality indicator when related to the research purpose, the chosen methodology and the composition of the sample, i.e. who was included and why.

Randomisation

While some authors argue that randomisation can be used in qualitative research, this is not commonly the case, as neither its feasibility nor its necessity or usefulness has been convincingly established for qualitative research [ 13 , 27 ]. Relevant disadvantages include the negative impact of a too large sample size as well as the possibility (or probability) of selecting “ quiet, uncooperative or inarticulate individuals ” [ 17 ]. Qualitative studies do not use control groups, either.

Interrater reliability, variability and other “objectivity checks”

The concept of “interrater reliability” is sometimes used in qualitative research to assess to which extent the coding approach overlaps between the two co-coders. However, it is not clear what this measure tells us about the quality of the analysis [ 23 ]. This means that these scores can be included in qualitative research reports, preferably with some additional information on what the score means for the analysis, but it is not a requirement. Relatedly, it is not relevant for the quality or “objectivity” of qualitative research to separate those who recruited the study participants and collected and analysed the data. Experiences even show that it might be better to have the same person or team perform all of these tasks [ 20 ]. First, when researchers introduce themselves during recruitment this can enhance trust when the interview takes place days or weeks later with the same researcher. Second, when the audio-recording is transcribed for analysis, the researcher conducting the interviews will usually remember the interviewee and the specific interview situation during data analysis. This might be helpful in providing additional context information for interpretation of data, e.g. on whether something might have been meant as a joke [ 18 ].

Not being quantitative research

Being qualitative research instead of quantitative research should not be used as an assessment criterion if it is used irrespectively of the research problem at hand. Similarly, qualitative research should not be required to be combined with quantitative research per se – unless mixed methods research is judged as inherently better than single-method research. In this case, the same criterion should be applied for quantitative studies without a qualitative component.

The main take-away points of this paper are summarised in Table 1 . We aimed to show that, if conducted well, qualitative research can answer specific research questions that cannot to be adequately answered using (only) quantitative designs. Seeing qualitative and quantitative methods as equal will help us become more aware and critical of the “fit” between the research problem and our chosen methods: I can conduct an RCT to determine the reasons for transportation delays of acute stroke patients – but should I? It also provides us with a greater range of tools to tackle a greater range of research problems more appropriately and successfully, filling in the blind spots on one half of the methodological spectrum to better address the whole complexity of neurological research and practice.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Endovascular treatment

Randomised Controlled Trial

Standard Operating Procedure

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

Philipsen, H., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2007). Kwalitatief onderzoek: nuttig, onmisbaar en uitdagend. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Qualitative research: useful, indispensable and challenging. In: Qualitative research: Practical methods for medical practice (pp. 5–12). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Chapter Google Scholar

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches . London: Sage.

Kelly, J., Dwyer, J., Willis, E., & Pekarsky, B. (2014). Travelling to the city for hospital care: Access factors in country aboriginal patient journeys. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22 (3), 109–113.

Article Google Scholar

Nilsen, P., Ståhl, C., Roback, K., & Cairney, P. (2013). Never the twain shall meet? - a comparison of implementation science and policy implementation research. Implementation Science, 8 (1), 1–12.

Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh, T., Heneghan, C., Liberati, A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B., & Thornton, H. (2011). The 2011 Oxford CEBM evidence levels of evidence (introductory document) . Oxford Center for Evidence Based Medicine. https://www.cebm.net/2011/06/2011-oxford-cebm-levels-evidence-introductory-document/ .

Eakin, J. M. (2016). Educating critical qualitative health researchers in the land of the randomized controlled trial. Qualitative Inquiry, 22 (2), 107–118.

May, A., & Mathijssen, J. (2015). Alternatieven voor RCT bij de evaluatie van effectiviteit van interventies!? Eindrapportage. In Alternatives for RCTs in the evaluation of effectiveness of interventions!? Final report .

Google Scholar

Berwick, D. M. (2008). The science of improvement. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299 (10), 1182–1184.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Christ, T. W. (2014). Scientific-based research and randomized controlled trials, the “gold” standard? Alternative paradigms and mixed methodologies. Qualitative Inquiry, 20 (1), 72–80.

Lamont, T., Barber, N., Jd, P., Fulop, N., Garfield-Birkbeck, S., Lilford, R., Mear, L., Raine, R., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2016). New approaches to evaluating complex health and care systems. BMJ, 352:i154.

Drabble, S. J., & O’Cathain, A. (2015). Moving from Randomized Controlled Trials to Mixed Methods Intervention Evaluation. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 406–425). London: Oxford University Press.

Chambers, D. A., Glasgow, R. E., & Stange, K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science : IS, 8 , 117.

Hak, T. (2007). Waarnemingsmethoden in kwalitatief onderzoek. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Observation methods in qualitative research] (pp. 13–25). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Russell, C. K., & Gregory, D. M. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Evidence Based Nursing, 6 (2), 36–40.

Fossey, E., Harvey, C., McDermott, F., & Davidson, L. (2002). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36 , 717–732.

Yanow, D. (2000). Conducting interpretive policy analysis (Vol. 47). Thousand Oaks: Sage University Papers Series on Qualitative Research Methods.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 , 63–75.

van der Geest, S. (2006). Participeren in ziekte en zorg: meer over kwalitatief onderzoek. Huisarts en Wetenschap, 49 (4), 283–287.

Hijmans, E., & Kuyper, M. (2007). Het halfopen interview als onderzoeksmethode. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [The half-open interview as research method (pp. 43–51). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Jansen, H. (2007). Systematiek en toepassing van de kwalitatieve survey. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Systematics and implementation of the qualitative survey (pp. 27–41). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Pv, R., & Peremans, L. (2007). Exploreren met focusgroepgesprekken: de ‘stem’ van de groep onder de loep. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Exploring with focus group conversations: the “voice” of the group under the magnifying glass (pp. 53–64). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41 (5), 545–547.

Boeije H: Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek: Denken en doen, [Analysis in qualitative research: Thinking and doing] vol. Den Haag Boom Lemma uitgevers; 2012.

Hunter, A., & Brewer, J. (2015). Designing Multimethod Research. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 185–205). London: Oxford University Press.

Archibald, M. M., Radil, A. I., Zhang, X., & Hanson, W. E. (2015). Current mixed methods practices in qualitative research: A content analysis of leading journals. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14 (2), 5–33.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Choosing a Mixed Methods Design. In Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research . Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320 (7226), 50–52.

O'Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity, 52 (4), 1893–1907.

Moser, A., & Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice, 24 (1), 9–18.

Marlett, N., Shklarov, S., Marshall, D., Santana, M. J., & Wasylak, T. (2015). Building new roles and relationships in research: A model of patient engagement research. Quality of Life Research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 24 (5), 1057–1067.

Demian, M. N., Lam, N. N., Mac-Way, F., Sapir-Pichhadze, R., & Fernandez, N. (2017). Opportunities for engaging patients in kidney research. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 4 , 2054358117703070–2054358117703070.

Noyes, J., McLaughlin, L., Morgan, K., Roberts, A., Stephens, M., Bourne, J., Houlston, M., Houlston, J., Thomas, S., Rhys, R. G., et al. (2019). Designing a co-productive study to overcome known methodological challenges in organ donation research with bereaved family members. Health Expectations . 22(4):824–35.

Piil, K., Jarden, M., & Pii, K. H. (2019). Research agenda for life-threatening cancer. European Journal Cancer Care (Engl), 28 (1), e12935.

Hofmann, D., Ibrahim, F., Rose, D., Scott, D. L., Cope, A., Wykes, T., & Lempp, H. (2015). Expectations of new treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: Developing a patient-generated questionnaire. Health Expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy, 18 (5), 995–1008.

Jun, M., Manns, B., Laupacis, A., Manns, L., Rehal, B., Crowe, S., & Hemmelgarn, B. R. (2015). Assessing the extent to which current clinical research is consistent with patient priorities: A scoping review using a case study in patients on or nearing dialysis. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 2 , 35.

Elsie Baker, S., & Edwards, R. (2012). How many qualitative interviews is enough? In National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper . National Centre for Research Methods. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/4/how_many_interviews.pdf .

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18 (2), 179–183.

Sim, J., Saunders, B., Waterfield, J., & Kingstone, T. (2018). Can sample size in qualitative research be determined a priori? International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21 (5), 619–634.

Download references

Acknowledgements

no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Neurology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Im Neuenheimer Feld 400, 69120, Heidelberg, Germany

Loraine Busetto, Wolfgang Wick & Christoph Gumbinger

Clinical Cooperation Unit Neuro-Oncology, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany

Wolfgang Wick

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LB drafted the manuscript; WW and CG revised the manuscript; all authors approved the final versions.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Loraine Busetto .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Busetto, L., Wick, W. & Gumbinger, C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2 , 14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Download citation

Received : 30 January 2020

Accepted : 22 April 2020

Published : 27 May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Mixed methods

- Quality assessment

Neurological Research and Practice

ISSN: 2524-3489

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

About Journal

American Journal of Qualitative Research (AJQR) is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal that publishes qualitative research articles from a number of social science disciplines such as psychology, health science, sociology, criminology, education, political science, and administrative studies. The journal is an international and interdisciplinary focus and greatly welcomes papers from all countries. The journal offers an intellectual platform for researchers, practitioners, administrators, and policymakers to contribute and promote qualitative research and analysis.

ISSN: 2576-2141

Call for Papers- American Journal of Qualitative Research

American Journal of Qualitative Research (AJQR) welcomes original research articles and book reviews for its next issue. The AJQR is a quarterly and peer-reviewed journal published in February, May, August, and November.

We are seeking submissions for a forthcoming issue published in February 2024. The paper should be written in professional English. The length of 6000-10000 words is preferred. All manuscripts should be prepared in MS Word format and submitted online: https://www.editorialpark.com/ajqr

For any further information about the journal, please visit its website: https://www.ajqr.org

Submission Deadline: November 15, 2023

Announcement

Dear AJQR Readers,

Due to the high volume of submissions in the American Journal of Qualitative Research , the editorial board decided to publish quarterly since 2023.

Volume 8, Issue 1

Current issue.

Social distancing requirements resulted in many people working from home in the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 pandemic. The topic of working from home was often discussed in the media and online during the pandemic, but little was known about how quality of life (QOL) and remote working interfaced. The purpose of this study was to describe QOL while working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. The novel topic, unique methodological approach of the General Online Qualitative Study ( D’Abundo & Franco, 2022a), and the strategic Social Distancing Sampling ( D’Abundo & Franco, 2022c) resulted in significant participation throughout the world (n = 709). The United Kingdom subset of participants (n = 234) is the focus of this article. This big qual, large qualitative study (n >100) included the principal investigator-developed, open-ended, online questionnaire entitled the “Quality of Life Home Workplace Questionnaire (QOLHWQ)” and demographic questions. Data were collected peak-pandemic from July to September 2020. Most participants cited increased QOL due to having more time with family/kids/partners/pets, a more comfortable work environment while being at home, and less commuting to work. The most cited issue associated with negative QOL was social isolation. As restrictions have been lifted and public health emergency declarations have been terminated during the post-peak era of the COVID-19 pandemic, the potential for future public health emergencies requiring social distancing still exists. To promote QOL and work-life balance for employees working remotely in the United Kingdom, stakeholders could develop social support networks and create effective planning initiatives to prevent social isolation and maximize the benefits of remote working experiences for both employees and organizations.

Keywords: qualitative research, quality of life, remote work, telework, United Kingdom, work from home.

(no abstract)

This essay reviews classic works on the philosophy of science and contemporary pedagogical guides to scientific inquiry in order to present a discussion of the three logics that underlie qualitative research in political science. The first logic, epistemology, relates to the essence of research as a scientific endeavor and is framed as a debate between positivist and interpretivist orientations within the discipline of political science. The second logic, ontology, relates to the approach that research takes to investigating the empirical world and is framed as a debate between positivist qualitative and quantitative orientations, which together constitute the vast majority of mainstream researchers within the discipline. The third logic, methodology, relates to the means by which research aspires to reach its scientific ends and is framed as a debate among positivist qualitative orientations. Additionally, the essay discusses the present state of qualitative research in the discipline of political science, reviews the various ways in which qualitative research is defined in the relevant literature, addresses the limitations and trade-offs that are inherently associated with the aforementioned logics of qualitative research, explores multimethod approaches to remedying these issues, and proposes avenues for acquiring further information on the topics discussed.

Keywords: qualitative research, epistemology, ontology, methodology

This paper examines the phenomenology of diagnostic crossover in eating disorders, the movement within or between feeding and eating disorder subtypes or diagnoses over time, in two young women who experienced multiple changes in eating disorder diagnosis over 5 years. Using interpretative phenomenological analysis, this study found that transitioning between different diagnostic labels, specifically between bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa binge/purge subtype, was experienced as disempowering, stigmatizing, and unhelpful. The findings in this study offer novel evidence that, from the perspective of individuals diagnosed with EDs, using BMI as an indicator of the presence, severity, or change of an ED may have adverse consequences for well-being and recovery and may lead to mischaracterization or misclassification of health status. The narratives discussed in this paper highlight the need for more person-centered practices in the context of diagnostic crossover. Including the perspectives of those with lived experience can help care providers working with individuals with eating disorders gain an in-depth understanding of the potential personal impact of diagnosis changing and inform discussions around developing person-focused diagnostic practices.

Keywords: feeding and eating disorders, bulimia nervosa, diagnostic labels, diagnostic crossover, illness narrative

Often among the first witnesses to child trauma, educators and therapists are on the frontline of an unfolding and multi-pronged occupational crisis. For educators, lack of support and secondary traumatic stress (STS) appear to be contributing to an epidemic in professional attrition. Similarly, therapists who do not prioritize self-care can feel depleted of energy and optimism. The purpose of this phenomenological study was to examine how bearing witness to the traumatic narratives of children impacts similar helping professionals. The study also sought to extrapolate the similarities and differences between compassion fatigue and secondary trauma across these two disciplines. Exploring the common factors and subjective individual experiences related to occupational stress across these two fields may foster a more complete picture of the delicate nature of working with traumatized children and the importance of successful self-care strategies. Utilizing Constructivist Self-Development Theory (CSDT) and focus group interviews, the study explores the significant risk of STS facing both educators and therapists.

Keywords: qualitative, secondary traumatic stress, self-care, child trauma, educators, therapists.

This study explored the lived experiences of residents of the Gulf Coast in the USA during Hurricane Katrina, which made landfall in August 2005 and caused insurmountable destruction throughout the area. A heuristic process and thematic analysis were employed to draw observations and conclusions about the lived experiences of each participant and make meaning through similar thoughts, feelings, and themes that emerged in the analysis of the data. Six themes emerged: (1) fear, (2) loss, (3) anger, (4) support, (5) spirituality, and (6) resilience. The results of this study allude to the possible psychological outcomes as a result of experiencing a traumatic event and provide an outline of what the psychological experience of trauma might entail. The current research suggests that preparedness and expectation are key to resilience and that people who feel that they have power over their situation fare better than those who do not.

Keywords: mass trauma, resilience, loss, natural disaster, mental health.

Women from rural, low-income backgrounds holding positions within the academy are the exception and not the rule. Most women faculty in the academy are from urban/suburban areas and middle- and upper-income family backgrounds. As women faculty who do not represent this norm, our primary goal with this article is to focus on the unique barriers we experienced as girls from rural, low-income areas in K-12 schools that influenced the possibilities for successfully transitioning to and engaging with higher education. We employed a qualitative duoethnographic and narrative research design to respond to the research questions, and we generated our data through semi-structured, critical, ethnographic dialogic conversations. Our duoethnographic-narrative analyses revealed six major themes: (1) independence and other benefits of having a working-class mom; (2) crashing into middle-class norms and expectations; (3) lucking and falling into college; (4) fish out of water; (5) overcompensating, playing middle class, walking on eggshells, and pushing back; and (6) transitioning from a working-class kid to a working class academic, which we discuss in relation to our own educational attainment.

Keywords: rurality, working-class, educational attainment, duoethnography, higher education, women.

This article draws on the findings of a qualitative study that focused on the perspectives of four Indian American mothers of youth with developmental disabilities on the process of transitioning from school to post-school environments. Data were collected through in-depth ethnographic interviews. The findings indicate that in their efforts to support their youth with developmental disabilities, the mothers themselves navigate multiple transitions across countries, constructs, dreams, systems of schooling, and services. The mothers’ perspectives have to be understood against the larger context of their experiences as citizens of this country as well as members of the South Asian diaspora. The mothers’ views on services, their journey, their dreams for their youth, and their interpretation of the ideas anchored in current conversations on transition are continually evolving. Their attempts to maintain their resilience and their indigenous understandings while simultaneously negotiating their experiences in the United States with supporting their youth are discussed.

Keywords: Indian-American mothers, transitioning, diaspora, disability, dreams.

This study explored the influence of yoga on practitioners’ lives ‘off the mat’ through a phenomenological lens. Central to the study was the lived experience of yoga in a purposive sample of self-identified New Zealand practitioners (n=38; 89.5% female; aged 18 to 65 years; 60.5% aged 36 to 55 years). The study’s aim was to explore whether habitual yoga practitioners experience any pro-health downstream effects of their practice ‘off the mat’ via their lived experience of yoga. A qualitative mixed methodology was applied via a phenomenological lens that explicitly acknowledged the researcher’s own experience of the research topic. Qualitative methods comprised an open-ended online survey for all participants (n=38), followed by in-depth semi-structured interviews (n=8) on a randomized subset. Quantitative methods included online outcome measures (health habits, self-efficacy, interoceptive awareness, and physical activity), practice component data (tenure, dose, yoga styles, yoga teacher status, meditation frequency), and socio-demographics. This paper highlights the qualitative findings emerging from participant narratives. Reported benefits of practice included the provision of a filter through which to engage with life and the experience of self-regulation and mindfulness ‘off the mat’. Practitioners experienced yoga as a self-sustaining positive resource via self-regulation guided by an embodied awareness. The key narrative to emerge was an attunement to embodiment through movement. Embodied movement can elicit self-regulatory pathways that support health behavior.

Keywords: embodiment, habit, interoception, mindfulness, movement practice, qualitative, self-regulation, yoga.