- EssayBasics.com

- Pay For Essay

- Write My Essay

- Homework Writing Help

- Essay Editing Service

- Thesis Writing Help

- Write My College Essay

- Do My Essay

- Term Paper Writing Service

- Coursework Writing Service

- Write My Research Paper

- Assignment Writing Help

- Essay Writing Help

- Call Now! (USA) Login Order now

- EssayBasics.com Call Now! (USA) Order now

- Writing Guides

Real Learning Takes Place Through Experience (Essay Sample)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Formal or academic learning starts at preschool and continues even after college. But mostly, the hardest yet most valuable lessons can be had only through real-life experiences. Learning through experiences shapes us as a person. The idea of having to live with the consequences of one’s decision can be scary and daunting. But the way you will change and evolve is a continuous process that’s worth it.

If you need to write about learning through experiences, it is best to look up an essay writing service provider who could help bring your ideas to life.

Essay on Importance of Learning Through Experience

We oftentimes limit our understanding of learning as everything we process inside a classroom. The different fields or subjects studied in school are applied in real life, both theoretically and practically. Subjects such as science, mathematics, language and literature, and values education are also applicable in everyday life.

Armed with academic know-how, a student can use head knowledge in decision-making and troubleshooting scenarios.

However, people who are textbook-smart are quite different from those who are known to be street-smart. There is a difference between performing in a classroom setting and responding to actual situations.

Learning through experience and in the real world can sometimes be a matter of life or death, compared with theoretical dialogues held within the four walls of a school.

That being said, it is a proven fact that people who are college-educated are known to make wiser decisions as they are able to apply what they have learned in school.

Skills in logic and critical thinking that they gleaned in the process also come in handy.

Knowledge is Power

The more you know in life, the more wisdom you have in terms of making decisions in work or job applications and career development.

Strategic and organizational thinking also play important roles in the process of learning.

Applying What You Know

True knowledge is wisdom applied, and it must be done in the absence of any neglect or misuse.

Real learning through experience takes stock of previous experiences, gathering lessons, and learning to apply them honorably.

In life, there is always an opportunity to apply theories or theses that we bring with us from our academic education. The real test is not actually in the classroom but in the real world.

The Equally-Good Benefits of Academic Learning

Schools not only offer theories and concepts on how to survive different situations. They arm us with the techniques and skills necessary to be successful in life.

That being said, an academic education gives us an edge over other people who have not attained any degree in universities and colleges.

Education makes us smarter and tougher than the rest who have not been as fortunate to finish their schooling.

Advantages and Benefits of Life Experiences

Life experiences are treasures to learn from, as many of them are scenarios we don’t usually study about in school. At the same time, most of us make mistakes in life. Through these wrong decisions, we learn to glean lessons that we take with us moving forward.

Good or bad, life experiences can either strengthen and toughen us up or scar us for life.

The Value of Our Response

Some people are wise and humble enough to turn a negative experience into an opportunity to grow and become better. In addition, these experiences become a permanent part of our personal history.

If we respond positively, the changes we experience could help us journey with other people who go through something similar.

Learning Experiences Are Varied

There are many types of learning experiences and some of those may represent failure or weakness, causing us to sometimes be hard on ourselves.

But we have the power to change our perspective and choose to move forward with hope and optimism in the face of a bad experience.

Trauma and Becoming Better People

Healing from a traumatic experience can be tough and tedious, but when the inner work is done well, the result always benefits the person and his community.

In this light, harsh experiences are still worth going through just as much as a near-perfect experience.

While we prefer the comfort of growth without pain, pain offers a unique voice in our stories and teaches us hard things.

Learning from Life is a Community Project

Life experiences are not solo journeys. As you learn from experience, others feel the impact. You will either be a bigger blessing to them or a heavier burden, depending on how you respond to the lesson.

Real-life experiences shape and mold us in a way that affirms our identity and purpose. This is why all life experiences outside the classroom are worth keeping and remembering.

Short 1 Minute Speech on the Importance of Learning Through Experience

The learning process of a person happens throughout the course of his life. Most commonly, we think of schools as the best place for this to happen. We don’t often consider the importance of learning through experience.

There is much to be said about how learning occurs in a classroom. You have a community of co-learners and a teacher to help aid your learning curve. But informal learning also offers unexpected benefits.

Active experimentation, reflective observation and self-reflection are three things that can happen when learning through experiences. In this scenario, a person is given the opportunity to connect mind, heart, and hands.

This results in a transforming experience that reading books, while important, may not always offer. With different outcomes to consider, a person is exposed to the consequences of his actions and decisions.

Personal involvement always leads to personal growth. A concrete experience that allows someone to live through the fruits of his decisions always prunes a person.

With each learning experience comes an incredible opportunity to become better people, whether or not the outcome was favorable.

What does it mean to learn through experience?

Learning through experience means opening yourself to the certainty of growth. It also recognizes that good or bad consequences are both valuable in shaping you as a person.

Why is learning through experience important?

Taking an experience and learning from it is so beneficial to our growth as human beings. It increases our resilience and our capacity to relate with others in light of critical situations. It also encourages decision-making, accountability, and ownership.

How To Learn Through Experience

One of the most common misconceptions is that learning is synonymous with education. You often hear colleagues say they stopped…

One of the most common misconceptions is that learning is synonymous with education.

You often hear colleagues say they stopped learning after leaving college. The truth is we only get an education from institutions. Learning, on the other hand, is a lifelong process.

To understand this, just think of how a baby learns.

Initially, the baby is too young to get up, walk, or say anything. But soon it starts moving around, and eventually, learns to walk and speak.

The baby does this just by learning from experience.

Learning through experience is not easy, but it is something we all do at different levels.

Let’s look at the example of the baby again. It is not afraid of anything because it doesn’t understand the concepts of safety or fear. As the years roll by, it will learn these concepts through experience. Learning from experience can make us stronger and more capable of doing the right things.

What Is A Learning Mindset?

Mindset is the basic mental structure or aptitude that shapes a person’s thoughts, actions, and behavior towards others. A person is known to possess a learning mindset when their natural tendency is to focus on learning consistently.

A learning mindset is a fundamental trait. A mindset focused on learning can be strong criteria to weigh factors such as:

The person’s approach to learning.

There are different types of learners. Some are comfortable with formal learning in a mentor/teacher-learner process. Then there are those who prefer real learning through experience.

Response to learning

Different people face different challenges and advantages while learning; and so their responses also vary. Some are quick learners; others could take longer to get used to a concept and could need repeat lessons or additional support. ( Zolpidem )

The takeaway

The first objective of any learning program is the ‘knowledge’ that the learners will gain from it. Be it something that boosts their interpersonal skills or professional skill acquisition.

Learning From Experience: How To Do It

Most of our life experiences are great opportunities to learn new skills for personal development. But many people don’t take advantage of such opportunities simply because they don’t have a mindset focused on learning.

For those who have a learning mindset, the experiences become the bedrock for self-reflection. These reflections help them assess their situation, their world view and understanding of human behavior, etc. They then put these ideas to the test and eventually gain new experiences.

Learning from experience is also known as Experiential Learning (EXL). One of the popular definitions of the process says it is “learning through reflection on doing”.

It is greatly different from conventional learning as there may be no teacher or mentor involved. The learner plays an active part in the learning process. It is an individual-focused learning technique for learning from experience.

A common example of real learning through experience is that of botany students. While they can simply learn about the various plants and trees by reading books on the subject, they are regularly taken on trips across biodiversity parks, gardens, and forested areas for learning from observation.

The learners don’t have to rely on things they hear from others or read from books but can learn based on their own experiences. Such learning is usually much more impactful as it can be counted as real learning through experience.

Such experiential learning is a common feature for students of streams such as history, architecture, tourism, and geology. Medical students also get to learn by observation as they attend live surgeries and observe the healing process of patients in hospitals.

David Kolb is a renowned name in the field of experiential learning. According to Kolb, knowledge acquisition is a perpetual cycle. We learn from our personal as well as professional experiences.

Kolb outlines four characteristics of a learner that must be present in anyone keen on learning from experience. These are:

Willingness to actively participate in the experience, ability to reflect upon the experience gained, analytical skills to visualize the experience, decision-making and problem-solving skills that can be applied to new-found ideas.

As the above learning experience examples highlight, the process of learning through experience requires a lot of self-effort, initiative, a desire to learn, and an action-based learning period. David Kolb’s experiential learning cycle is an ideal framework for understanding the various stages of the process.

Many modern educators are well-versed with the importance of experiential learning. One of the key reasons behind its impact is considered to be the emotional and sensory experience that such hands-on learning provides. It helps learners connect with actual knowledge instead of simply learning the concepts and information through books. The personal involvement of learners helps them in reflection and that gradually furthers them to learning from experience.

The crux of experiential learning is highlighted by five questions:

Did you notice, why did that happen, does that happen in life, why does that happen, how can you use that.

These questions make learners reflect on what they observed or experienced and gain long-term knowledge.

Need For Businesses To Cultivate A Learning Mindset:

Learning experience examples:.

If you look at the most popular and high-paying jobs of today, you will find that most of them didn’t even exist 20-30 years ago. On the other hand, many of the hottest jobs of 30 years ago—DOS operators, typists, switchboard operators—don’t exist anymore.

Constantly changing technologies and innovations keep changing the nature of jobs and processes that we see in our daily lives..

In recent years, we are witnessing the rapid proliferation of technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT) and automation. Jobs are increasingly becoming redundant.

According to research by McKinsey, 400 to 800 million contemporary jobs will no longer exist by 2030.

However, this doesn’t imply there will be no jobs for those currently employed in these positions.

Some jobs are likely to morph into a different form—just like the typists of yesteryears have now been replaced by computer operators and commercial painters replaced by graphic designers.

Other new jobs will be of a more ‘human’ nature that focus on teamwork and creativity. Automation will only take away the mechanical part of the jobs the human aspect and management roles will still be with humans.

So, the time is ripe for businesses to cultivate a strong experiential learning mindset to make sure their employees are ready for future technologies and jobs. Let’s look at some core competencies that human resource managers need to focus on:

Digital Expertise:

With the rapid growth in AI technologies and tools, many businesses have already invested in AI tech or are planning to do so gradually over the next few years. However, most of those companies are not focusing on making their current employees AI-ready.

Once machine learning and AI technologies enter more operational areas, there will be a need for personnel who are well-versed in working with automation and AI.

Ability To Work Seamlessly In An Inclusive Environment:

Diversity and inclusivity are no longer just jargon. The future belongs to offices that are gender/culture/ethnicity-neutral. There will be diverse perspectives, lifestyles, and behaviors in every organization. People who have open or hidden biases against some or the other section will not be desirable. Teams will also need to get rid of their generational biases.

Learning is a continuous process that is not only academic but greatly experiential as well. Everything we do, observe or hear, creates an opportunity for evaluation, understanding, and creation of new ideas. These ideas subsequently get integrated into the work processes and are validated through new experiences.

It is a constant cyclic progression that we all need to learn. However, as various learning experience examples indicate, it is often not easy to get into the learning mindset. That’s where Harappa Education’s Learning Expertly course can help you. It teaches you about the growth mindset and helps you and adopt fresh perspectives on existing problems.

Sign up for the course to step on the road to learning.

Explore our Harappa Diaries section to know more about topics related to the Think habit such as Meaning of Heuristic , Critical Thinking , What is an Argument , Creative Thinking & Design Thinking .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

The Role of Experiential Learning on Students’ Motivation and Classroom Engagement

Yangtao kong.

1 School of Education, Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an, China

2 Faculty of Educational Science, Shaanxi Xueqian Normal University, Xi’an, China

Due to the birth of positive psychology in the process of education, classroom engagement has been flourished and got a remarkable role in the academic field. The other significant determining factor of success in education is motivation which is in line with classroom engagement. Moreover, based on the constructivist approach, experiential learning (EL) as a new method in education and a learner-centric pedagogy is at the center of attention, as a result of its contributions to improving the value of education which centers on developing abilities, and experiences. The current review makes an effort to consider the role of EL on students’ classroom engagement and motivation by inspecting its backgrounds and values. Subsequently, the efficacy of findings for academic experts in educational contexts is discussed.

Introduction

It is stated that a basic causative factor in the general achievement of learners studying in higher education is learners’ engagement ( Xerri et al., 2018 ; Derakhshan, 2021 ). It is extensively approved that learners who are actively participating in the learning progression and take interest in their academic education are more likely to achieve higher levels of learning ( Wang et al., 2021 ). Therefore, higher education institutions encourage learners to use their capabilities, as well as learning opportunities and facilities that enable them to be actively engaged ( Broido, 2014 ; Xie and Derakhshan, 2021 ). Moreover, students’ dissatisfaction, boredom, negative experiences, and dropping out of school are in part due to the low engagement in academic activities ( Derakhshan et al., 2021 ). It has been demonstrated that engagement is, directly and indirectly, related to intelligence, interest, motivation, and pleasure with learning outcomes within many academic fields ( Yin, 2018 ). Likewise, engagement is a construct that is shaped from the multifaceted relations of perceptions, feelings, and motivation which is corresponding to the progress of self-determination theory in the motivation realm ( Mercer and Dörnyei, 2020 ). Besides, the student’s motivation is a significant factor in cultivating learning and consequently increasing the value of higher education because the more the learners are motivated, the more likely they can be successful in their activities ( Derakhshan et al., 2020 ; Halif et al., 2020 ).

From a psychological point of view, motivating learners and engaging them in the classroom are closely related ( Han and Wang, 2021 ); nevertheless, motivation consists of factors that are psychological and difficult to observe, while engagement involves behaviors that can be observed by others that it is not simple to notice and estimate learners’ motivation ( Reeve, 2012 ). In other words, educators cannot concretely understand the fulfillment of their learners’ basic mental necessities and enthusiasm for learning ( Reeve, 2012 ). Nonetheless, Reeve asserted that in contrast to motivation, learners’ engagement by all accounts is a phenomenon that is distinctive and can nearly be noticed. Generally, educators can impartially consider whether or not a specific learner is engaged in the class exercises, such as problem solving.

As a reaction to the traditional teaching approach that is teacher-centric ( Che et al., 2021 ) and following the inclination to expanding interest in a more unique, participative learning atmosphere, educational organizations are orienting toward learning approaches that cultivate students’ involvement, interest, and dynamic participation. EL is a successful teaching method facilitating active learning through providing real-world experiences in which learners interact and critically evaluate course material and become involved with a topic being taught ( Boggu and Sundarsingh, 2019 ). Based on the teaching theory of Socrates, this model relies on research-based strategies which allow learners to apply their classroom knowledge to real-life situations to foster active learning, which consequently brings about a better retrieval ( Bradberry and De Maio, 2019 ). Indeed, engaging in daily activities, such as going to classes, completing schoolwork, and paying attention to the educator, is all indicators of classroom engagement ( Woods et al., 2019 ). Moreover, by participating in an EL class paired with relevant academic activities, learners improve their level of inherent motivation for learning ( Helle et al., 2007 ) and they have the opportunity to choose multiple paths to solve problems throughout the learning process by having choices and being autonomous ( Svinicki and McKeachie, 2014 ). EL is regarded as learning by action whereby information is built by the student during the renovation of changes ( Afida et al., 2012 ). Within EL, people become remarkably more liable for their learning which regulates a stronger connection between the learning involvement, practices, and reality ( Salas et al., 2009 ) that are key roles in learning motivation.

To make sure that the learners gain the required knowledge and get the factual training, it is equally important to give them time to develop their ability to use their knowledge and apply those skills in real-world situations to resolve problems that are relevant to their careers ( Huang and Jiang, 2020 ). So, it seems that they would like more hands-on training and skills development, but awkwardly, in reality, they generally just receive theoretical and academic education ( Green et al., 2017 ). In addition, as in today’s modern world, where shrewd and high-performing people are required, motivation and engagement should be prioritized in educational institutions as they are required features in the learning setting while they are often overlooked in classrooms ( Afzali and Izadpanah, 2021 ). Even though studies on motivation, engagement, and EL have been conducted so far; however, based on the researcher’s knowledge, just some have currently carried out systematic reviews about the issue and these studies have not been all taken together to date; therefore, concerning this gap, the current mini-review tries to take their roles into account in education.

Classroom Engagement and Motivation

As a three-dimensional construct, classroom engagement can be classified into three types: physical, emotional, and psychological ( Rangvid, 2018 ). However, it is not always easy to tell whether a learner is engaged because observable indicators are not always accurate. Even those who display signs of curiosity or interest in a subject or who seem engaged may not acquire knowledge about it. Others may also be learning despite not displaying any signs of physical engagement ( Winsett et al., 2016 ).

As an important component of success and wellbeing, motivation encourages self-awareness in individuals by inspiring them ( Gelona, 2011 ). Besides, it is a power that manages, encourages, and promotes goal-oriented behavior, which is not only crucial to the process of learning but also essential to educational achievement ( Kosgeroglu et al., 2009 ). It appears that classroom motivation is influenced by at least five factors: the learner, the educator, the course content, the teaching method, and the learning environment ( D’Souza and Maheshwari, 2010 ).

Experiential Learning

EL, developed by Kolb in 1984, is a paradigm for resolving the contradiction between how information is gathered and how it is used. It is focused on learning through experience and evaluating learners in line with their previous experiences ( Sternberg and Zhang, 2014 ). The paradigm highlights the importance of learners’ participation in all learning processes and tackles the idea of how experience contributes to learning ( Zhai et al., 2017 ). EL is a method of teaching that allows learners to learn while “Do, Reflect, and Think and Apply” ( Butler et al., 2019 , p. 12). Students take part in a tangible experience (Do), replicate that experience and other evidence (Reflect), cultivate theories in line with experiences and information (Think), and articulate an assumption or elucidate a problem (Apply). It is a strong instrument for bringing about positive modifications in academic education which allow learners to apply what they have learned in school to real-world problems ( Guo et al., 2016 ). This way of learning entails giving learners more authority and responsibility, as well as involving them directly in their learning process within the learning atmosphere. Furthermore, it encourages learners to be flexible learners, incorporate all possible ways of learning into full-cycle learning, and bring about effective skills and meta-learning abilities ( Kolb and Kolb, 2017 ).

Implications and Future Directions

This review focused on the importance of EL and its contributions to classroom engagement and motivation. Since experiential education tends to engage a wider range of participants who can have an impact on the organization, employees, educators, leaders, and future colleagues, it is critical to maintain its positive, welcoming atmosphere. The importance of EL lies in its ability to facilitate connections between undergraduate education and professional experience ( Earnest et al., 2016 ), so improving the connection between the university and the world of work ( Friedman and Goldbaum, 2016 ).

The positive effect of EL has actual implications for teachers who are thinking of implementing this method in their classes; indeed, they can guarantee their learners’ success by providing them with the knowledge required in performing the task as following the experiential theory, knowledge is built through converting practice into understanding. Based on the literature review, the conventional role of the teacher shifts from knowledge provider to a mediator of experience through well-known systematic processes. Likewise, teachers should encourage learners by providing information, suggestion, and also relevant experiences for learning to build a learning milieu where they can be engaged in positive but challenging learning activities that facilitate learners’ interaction with learning materials ( Anwar and Qadir, 2017 ) and illustrates their interest and motivation toward being a member of the learning progression. By learners’ dynamic participation in experiential activities, the teacher can trigger their ability to retain knowledge that leads to their intrinsic motivation and interest in the course material ( Zelechoski et al., 2017 ).

The present review is significant for the learners as it allows them to model the appropriate behavior and procedures in real-life situations by putting the theory into practice. Indeed, this method helps learners think further than memorization to evaluate and use knowledge, reflecting on how learning can be best applied to real-world situations ( Zelechoski et al., 2017 ). In the context of EL, students often find activities challenging and time-consuming which necessitates working in a group, performing work outside of the classroom, learning and integrating subject content to make decisions, adapt procedures, compare, and contrast various resources of information to detect a difficulty at one hand and implement that information on the other hand to form a product that aims to solve the issue. Participation, interaction, and application are fundamental characteristics of EL. During the process, it is possible to be in touch with the environment and to be exposed to extremely flexible processes. In this way, education takes place on all dimensions which cover not only the cognitive but also the affective and behavioral dimensions to encompass the whole person. Learners enthusiastically participate in mental, emotional, and social interactions during the learning procedure within EL ( Voukelatou, 2019 ). In addition, learners are encouraged to think logically, find solutions, and take appropriate action in relevant situations. This kind of instruction not only provides opportunities for discussion and clarification of concepts and knowledge, but also provides feedback, review, and transfer of knowledge and abilities to new contexts.

Moreover, for materials developers and syllabus designers to truly start addressing the learners’ motivation and engagement, they could embrace some interesting and challenging activities because when they can find themselves successful in comprehending the issue and being able to apply their information to solve it; they are not only more interested to engage in the mental processes required for obtaining knowledge but also more motivated and eager to learn. More studies can be conducted to investigate the effect of EL within different fields of the study courses with a control group design to carry out between-group comparisons. Besides, qualitative research is recommended to scrutinize the kinds of EL activities which make a more considerable effect on the EFL learners’ motivation and success and even their achievement.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

This study was funded by the Projects of National Philosophy Social Science Fund, PRC (17CRK008), and the Projects of Philosophy and Social Science Fund of Shaanxi Province, PRC (2018Q11).

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Afida A., Rosadah A. M., Aini H., Mohd Marzuki M. (2012). Creativity enhancement through experiential learning . Adv. Nat. Appl. Sci. 6 , 94–99. [ Google Scholar ]

- Afzali Z., Izadpanah S. (2021). The effect of the flipped classroom model on Iranian English foreign language learners: engagement and motivation in English language grammar . Cogent Educ. 8 :1870801. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2020.1870801 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anwar K., Qadir G. H. (2017). A study of the relationship between work engagement and job satisfaction in private companies in Kurdistan . Int. J. Adv. Eng. Manage. Sci. 3 , 1102–1110. doi: 10.24001/ijaems.3.12.3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boggu A. T., Sundarsingh J. (2019). An experiential learning approach to fostering learner autonomy among Omani students . J. Lang. Teach. Res. 10 , 204–214. doi: 10.17507/jltr.1001.23 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bradberry L. A., De Maio J. (2019). Learning by doing: The long-term impact of experiential learning programs on student success . J. Political Sci. Educ. 15 , 94–111. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2018.1485571 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Broido E. M. (2014). Book review: one size does not fit all: traditional and innovative models of student affairs practice . J. Stud. Aff. Afr. 2 , 93–96. doi: 10.14426/jsaa.v2i1.52 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Butler M. G., Church K. S., Spencer A. W. (2019). Do, reflect, think, apply: experiential education in accounting . J. Acc. Educ. 48 , 12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccedu.2019.05.001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Che F. N., Strang K. D., Vajjhala N. R. (2021). Using experiential learning to improve student attitude and learning quality in software engineering education . Int. J. Innovative Teach. Learn. Higher Educ. 2 , 1–22. doi: 10.4018/IJITLHE.20210101.oa2 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- D’Souza K. A., Maheshwari S. K. (2010). Factors influencing student performance in the introductory management science course . Acad. Educ. Leadersh. J. 14 , 99–119. [ Google Scholar ]

- Derakhshan A. (2021). The predictability of Turkman students’ academic engagement through Persian language teachers’ nonverbal immediacy and credibility . J. Teach. Persian Speakers Other Lang. 10 , 3–26. [ Google Scholar ]

- Derakhshan A., Coombe C., Arabmofrad A., Taghizadeh M. (2020). Investigating the effects of English language teachers’ professional identity and autonomy in their success . Issue Lang. Teach. 9 , 1–28. doi: 10.22054/ilt.2020.52263.496 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Derakhshan A., Kruk M., Mehdizadeh M., Pawlak M. (2021). Boredom in online classes in the Iranian EFL context: sources and solutions . System 101 :102556. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102556 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Earnest D., Rosenbusch K., Wallace-Williams D., Keim A. (2016). Study abroad in psychology: increasing cultural competencies through experiential learning . Teach. Psychol. 43 , 75–79. doi: 10.1177/0098628315620889 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Friedman F., Goldbaum C. (2016). Experiential learning: developing insights about working with older adults . Clin. Soc. Work. J. 44 , 186–197. doi: 10.1007/s10615-016-0583-4 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gelona J. (2011). Does thinking about motivation boost motivation levels . Coaching Psychol. 7 , 42–48. [ Google Scholar ]

- Green R. A., Conlon E. G., Morrissey S. M. (2017). Task values and self-efficacy beliefs of undergraduate psychology students . Aust. J. Psychol. 69 , 112–120. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12125 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guo F., Yao M., Wang C., Yang W., Zong X. (2016). The effects of service learning on student problem solving: the mediating role of classroom engagement . Teach. Psychol. 43 , 16–21. doi: 10.1177/0098628315620064 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Halif M. M., Hassan N., Sumardi N. A., Omar A. S., Ali S., Aziz R. A., et al.. (2020). Moderating effects of student motivation on the relationship between learning styles and student engagement . Asian J. Univ. Educ. 16 , 94–103. [ Google Scholar ]

- Han Y., Wang Y. (2021). Investigating the correlation among Chinese EFL teachers’ self-efficacy, work engagement, and reflection . Front. Psychol. 12 :763234. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.763234, PMID: [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Helle L., Tynjälä P., Olkinuora E., Lonka K. (2007). ‘Ain’t nothing like the real thing.’ Motivation and study processes on a work-based project course in information systems design . Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 77 , 397–411. doi: 10.1348/000709906X105986, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huang R., Jiang L. (2020). Authentic assessment in Chinese secondary English classrooms: teachers’ perception and practice . Educ. Stud. , 1–14. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2020.1719387 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kolb A. Y., Kolb D. A. (2017). Experiential learning theory as a guide for experiential educators in higher education . Exp. Learn. Teach. Higher Educ. 1 , 7–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kosgeroglu N., Acat M. B., Ayranci U., Ozabaci N., Erkal S. (2009). An investigation on nursing, midwifery and health care students’ learning motivation in Turkey . Nurse Educ. Pract. 9 , 331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2008.07.003, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mercer S., Dörnyei Z. (2020). Engaging Language Learners in Contemporary Classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rangvid B. S. (2018). Student engagement in inclusive classrooms . Educ. Econ. 26 , 266–284. doi: 10.1080/09645292.2018.1426733 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reeve J. (2012). “ A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement ,” in Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. eds. Christenson S. L., Reschly A. L., Wylie C. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 149–172. [ Google Scholar ]

- Salas E., Wildman J. L., Piccolo R. F. (2009). Using simulation-based training to enhance management education . Acad. Manage. Learn. Educ. 8 , 559–573. doi: 10.5465/amle.8.4.zqr559 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sternberg R. J., Zhang L. F. (2014). Perspectives on Thinking, Learning and Cognitive Styles. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Google Scholar ]

- Svinicki M. D., McKeachie W. J. (2014). McKeachie’s Teaching Tips: Strategies, Research, and Theory for College and University Teachers. 14th Edn . Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. [ Google Scholar ]

- Voukelatou G. (2019). The contribution of experiential learning to the development of cognitive and social skills in secondary education: A case study . Educ. Sci. 9 , 127–138. doi: 10.3390/educsci9020127 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang Y., Derakhshan A., Zhang L. J. (2021). Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: The past, current status and future directions . Front. Psychol. 12:731721. 12 :731721. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Winsett C., Foster C., Dearing J., Burch G. (2016). The impact of group experiential learning on student engagement . Acad. Bus. Res. J. 3 , 7–17. [ Google Scholar ]

- Woods A. D., Price T., Crosby G. (2019). The impact of the student-athlete’s engagement strategies on learning, development, and retention: A literary study . Coll. Stud. J. 53 , 285–292. [ Google Scholar ]

- Xerri M. J., Radford K., Shacklock K. (2018). Student engagement in academic activities: A social support perspective . High. Educ. 75 , 589–605. doi: 10.1007/s10734-017-0162-9 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Xie F., Derakhshan A. (2021). A conceptual review of positive teacher interpersonal communication behaviors in the instructional context . Front. Psychol. 12 , 1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.708490, PMID: [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yin H. (2018). What motivates Chinese undergraduates to engage in learning? Insights from a psychological approach to student engagement research . High. Educ. 76 , 827–847. doi: 10.1007/s10734-018-0239-0 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zelechoski A. D., Riggs Romaine C. L., Wolbransky M. (2017). Teaching psychology and law . Teach. Psychol. 44 , 222–231. doi: 10.1177/0098628317711316 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhai X., Gu J., Liu H., Liang J.-C., Tsai C.-C. (2017). An experiential learning perspective on students’ satisfaction model in a flipped classroom context . Educ. Technol. Soc. 20 , 198–210. [ Google Scholar ]

Why learning from experience is the educational wave of the future

Dean of Engineering and Professor, McMaster University

Disclosure statement

Ishwar K. Puri receives funding from National Science and Engineering Research Council. He is chair of the National Council of Deans of Engineering and Applied Science and Fellow of the Canadian Academy of Engineering.

McMaster University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation CA.

McMaster University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

The university experience has changed .

It used to be enough for students to spend four years working hard on assignments, labs and exams to earn a useful undergraduate degree that signalled competence and was redeemable for a good job.

Employers would spend weeks or months training their newly hired graduates , sometimes in cohorts, shaping their broad knowledge so it could be applied to the specific needs of the company or government agency.

Today, in contrast, employers want fresh graduates who they don’t have to train .

That means students must learn and apply their knowledge at the same time, inside and outside the classroom, all without adding extra months or years to their studies . After completing their degrees, they are expected to be ready to compete for jobs and jump into working life immediately, without further training.

In the ongoing global drive for efficiency and competitiveness, education and training are now seen as the responsibility of the post-secondary sector, where students face a wider set of expectations not only to learn and synthesize subject matter, but to adapt it and put it to use almost immediately.

Learning by doing

This idea of learning by doing is what is now called “experiential learning,” and though it’s demanding, it is also very effective. It is vital to the mission of all advanced institutions of higher learning, including the one where I am dean of engineering, McMaster University in Hamilton.

In class, this method of learning means replacing chalk-and-talk pedagogy of the past with inquiry, problem-based and project-based learning, sometimes using the tools of what we call a maker space — an open, studio-like creative workshop.

These methods recognize that lectures on complex, abstract subjects are difficult to comprehend, and that hands-on, minds-on learning by experience not only makes it easier to absorb complex material, it also makes it easier to remember .

Outside class, experiential learning takes the form of clubs, activities and competitions for fun, such as the international EcoCAR competition, converting muscle cars from gas to electric power , or hackathons that see students compete to solve complex technical and social problems .

This year at McMaster, experiential learning has been both the competition and the prize as six winners of an extracurricular Big Ideas competition flew off to tour Silicon Valley facilities where they hope one day to work or learn how to start up their own ventures.

Experiential learning also means engaging undergraduates directly in high-level research that was once the exclusive domain of graduate students and professors, exposing them to scholarship at the highest level from early in their academic careers.

In the community, experiential learning is learning through service , both within and beyond one’s area of study — rebuilding hurricane-damaged communities, for example, or helping at local soup kitchens. We are teaching students not only to be workers who drive the modern economy, but also to be engaged citizens .

Work-integrated learning sees students stepping into the actual workplace to get a flavour of what working life is like in their fields , including managing time, working independently, multi-tasking, and adapting to the particular culture and expectations of a specific workplace, all as part of their formal education.

We want students to understand and approach the grand challenges and wicked problems facing our world, such as climate change and opioid addiction, which are not solely issues of science or technology, sociology or economics, but complex, layered issues that demand broad thinking and collaboration.

Canada needs innovators

We want our students to be innovators. If life in Canada is to improve, especially in the context of challenging trade relationships such as NAFTA, we need a workforce that can address global problems with innovation that is relevant —technologically, socially, economically, with respect for all cultures and genders.

All of this learning drives students to begin thinking and acting with their careers in mind from their very first year of study.

Is that fair?

It is important to remember that high school has changed too. Students are better prepared than they were a generation ago. By the time they enter university, they are more aware of the new demands on their time and achievements.

Much more information is also available about employment and specific employers from portals like Glassdoor , allowing students to make more informed choices about their co-op placements or the permanent employers they will target or reject, based on reputation and organizational climate.

We cannot change the fact that the world is more competitive, nor that it takes more to succeed than it used to.

What we can do is make sure that the extra work that goes into creating and completing a fully realized university experience is as valuable as it can possibly be.

- Universities

- Engineering

- Competitiveness

- Post-secondary education

- Experiential learning

Biocloud Project Manager - Australian Biocommons

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Deputy Editor - Technology

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

6 The Learning Way: Learning from Experience as the Path to Lifelong Learning and Development

Angela Passarelli, Department of Management & Marketing, College of Charleston

David Kolb, Experience Based Learning Systems

- Published: 21 November 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Lifelong learning requires the ability to learn from life experiences. This chapter describes the theory of experiential learning, whereby knowledge is generated from experience through a cycle of learning driven by the resolution of dual dialectics of action/reflection and experience/abstraction. We provide an overview of stylistic preferences that arise from patterns of choosing among these modes of learning, as well as the spaces in which learning occurs. Movement through these modes and spaces link one experience to the next, creating a learning spiral that guides growth and development through a lifetime. Lifelong learning is also shaped by an individual’s learning identity, the extent to which one believes he or she can learn, and learning relationships, connections that promote movement through the learning spiral. Strategies for enhancing the learning process are provided for each of these topics.

… to learn from life itself and to make the conditions of life such that all will learn in the process of living. John Dewey Democracy and Education

The Challenges of Lifelong Learning

Since its emergence as a catchy alliterative slogan in the 1970s, “lifelong learning” has steadily moved from an inspiring aspiration to a necessary reality. The transformative global, social, economic, and technological conditions that were envisioned forty years ago have come to fruition in a way that requires a fundamental rethinking of the relationship between learning and education. From a front-loaded, system-driven educational structure dominated by classroom learning, we are in the process of transitioning to a new reality where individual learners are becoming more responsible for the direction of their own learning in a multitude of learning environments that span their lifetime. This transition parallels other self-direction requirements that have been placed on individuals by the emergence of the global economy such as responsibility for one’s own retirement planning and health care. As Olssen has noted,

In this sense lifelong learning is a market discourse that orientates education to the enterprise society where the learner becomes an entrepreneur of him/her self.… Ultimately lifelong learning shifts responsibility from the system to the individual whereby individuals are responsible for self-emancipation and self-creation. It is the discourse of autonomous and independent individuals who are responsible for updating their skills in order to achieve their place in society. (2006, p. 223)

The challenge of lifelong learning is not just about learning new marketable skills in an ever-changing economy. It is about the whole person and their personal development in their many roles as family member, citizen, and worker. While the individual is primarily responsible for his or her learning, it occurs in an interdependent relationship with others. Olssen continues,

Self organized learning certainly has a place in this scenario. But also essential are the twin values of freedom and participation as embodied, for instance, in Dewey’s pragmatism, where learning rests on a mode of life where reason is exercised through problem-solving where the individual participates and contributes to the collective good of society and in the process constitutes their own development. The learner is engaged in a process of action for change as part of a dialogic encounter rather than as a consequence of individual choice. (2006, p. 225)

This definition of lifelong learning as ongoing human development extends the learning endeavor beyond the walls of a formal classroom.

To navigate on this new journey of lifelong learning the most important thing for individuals to learn is how to learn. Experiential learning theory (ELT) provides this roadmap by helping learners understand how learning occurs, themselves as learners, and the nature of the spaces where learning occurs. With this awareness, learners can live each successive life experience fully—present and mindful in the moment. We call this approach to lifelong learning “The Learning Way.” The learning way is about approaching life experiences with a learning attitude. The learning way is not the easiest way to approach life but in the long run it is the wisest. Other ways of living tempt us with immediate gratification at our peril. The way of dogma, the way of denial, the way of addiction, the way of submission, and the way of habit; all offer relief from uncertainty and pain at the cost of entrapment on a path that winds out of our control. The learning way requires deliberate effort to create new knowledge in the face of uncertainty and failure; and opens the way to new, broader, and deeper horizons of experience. The learning way honors affective experience in tandem with cognition, acknowledging that, ultimately, learning is intrinsically rewarding and empowering. It is not a solitary journey but is sustained and nurtured through growth-fostering relationships in one’s life.

In this chapter we describe how ELT research can help learners on their journey of lifelong learning. We examine the key concepts of the theory—the cycle of learning from experience, learning styles, learning spaces, the spiral of learning and development, learning identity, and learning relationships—and their application to lifelong learning and development. For each concept we provide strategies that individuals can use to enhance their lifelong learning process.

Experiential Learning Theory

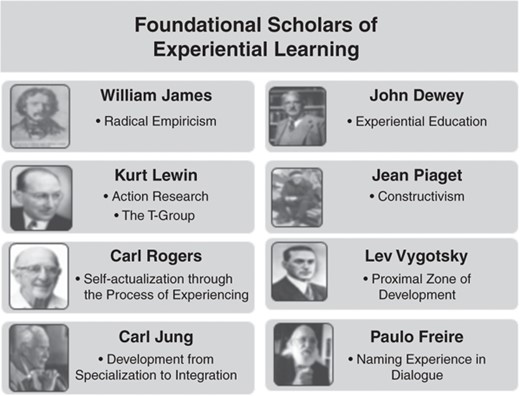

Experiential learning theory draws on the work of prominent 20th-century scholars who gave experience a central role in their theories of human learning and development—notably William James, John Dewey, Kurt Lewin, Jean Piaget, Lev Vygotsky, Carl Jung, Paulo Freire, Carl Rogers, and others (see Figure 6.1 )—to develop a dynamic, holistic model of the process of learning from experience and a multidimensional model of adult development. ELT is a dynamic view of learning based on a learning cycle driven by the resolution of the dual dialectics of action/reflection and experience/abstraction. It is a holistic theory that defines learning as the major process of human adaptation involving the whole person. As such, ELT is applicable not only in the formal education classroom but in all arenas of life. The process of learning from experience is ubiquitous, present in human activity everywhere all the time. The holistic nature of the learning process means that it operates at all levels of human society from the individual, to the group, to organizations, to society as a whole. Research based on ELT has been conducted all around the world supporting the cross-cultural applicability of the model.

ELT integrates the works of the foundational experiential learning scholars around six propositions that they all share:

Learning is best conceived as a process, not in terms of outcomes . Although punctuated by knowledge milestones, learning does not end at an outcome, nor is it always evidenced in performance. Rather, learning occurs through the course of connected experiences. As Dewey suggests, “education must be conceived as a continuing reconstruction of experience:… the process and goal of education are one and the same thing” (1897, p. 79).

All learning is relearning . Learning is best facilitated by a process that draws out the learners’ beliefs and ideas about a topic so that they can be examined, tested, and integrated with new, more refined ideas. Piaget called this proposition constructivism—individuals construct their knowledge of the world based on their experience.

Learning requires the resolution of conflicts between dialectically opposed modes of adaptation to the world . Conflict, differences, and disagreement are what drive the learning process. In the process of learning one is called on to move back and forth between opposing modes of reflection and action and feeling and thinking.

Learning is a holistic process of adaptation . Learning is not just the result of cognition but involves the integrated functioning of the total person—thinking, feeling, perceiving, and behaving. It encompasses other specialized models of adaptation from the scientific method to problem solving, decision making, and creativity.

Learning results from synergetic transactions between the person and the environment . In Piaget’s terms, learning occurs through equilibration of the dialectic processes of assimilating new experiences into existing concepts and accommodating existing concepts to new experience. Following Lewin’s famous formula that behavior is a function of the person and the environment, ELT holds that learning is influenced by characteristics of the person and the learning environment.

Learning is the process of creating knowledge . ELT proposes a constructivist theory of learning whereby social knowledge is created and recreated in the personal knowledge of the learner. This stands in contrast to the “transmission” model on which much current educational practice is based where preexisting fixed ideas are transmitted to the learner.

Foundational Scholars of Experiential Learning

The Cycle of Experiential Learning