- Share full article

Turning Points: Guest Essay

The Big Question: Why Do We Tell Stories?

Some key figures in literature, the performing arts, science and more ponder the purpose and vitality of storytelling in our lives.

Credit... Paul Blow

Supported by

By The New York Times

- Dec. 8, 2022

This article is part of a series called Turning Points , in which writers explore what critical moments from this year might mean for the year ahead. You can read more by visiting the Turning Points series page .

We have been telling stories since our beginnings. Some researchers posit that the origins of language date back more than 20 million years, while writing surfaced around 3200 B.C. Today, elaborate cave paintings, ancient parchment scrolls and centuries-old poems have evolved into literature and operas and Twitter threads, but our innate drive to recount narratives about who we are, where we come from and what we mean to each other remains an essential trait of being human.

We asked a group of luminaries from various fields to answer a fundamental question: Why do we tell stories?

Their responses below have been edited and condensed.

Amanda Gorman: ‘We Tell Stories Because We Are Human’

In elementary school, I was told there are only a few reasons to write: to explain, persuade or entertain an audience, or to express oneself. As a young girl passing through the educational system, those purposes suited me for a time; I could write the assigned essay and receive an A grade. But as I continued to grow and challenge myself as a poet and activist, I soon found that those purposes I had unquestioningly absorbed weren’t enough for me.

While I’ve been writing ever since I can remember, I was around 8 when my love for language started to kick in full throttle. In third grade, my teacher read chapters of Ray Bradbury’s “Dandelion Wine” to my class, and every day I’d sit, enchanted and enraptured by the sweeping words of this literary great. While it was prose, not poetry, the makings of poetry in this novel were clear and intoxicating to my elementary school mind: metaphor, simile and rhythm. I didn’t choose poetry, but rather it chose me. In it, I found a safe place where I could write — literally — outside the lines, break the rules and be heard.

As I grew older and continued to write in my own voice, I discovered that I wasn’t doing so just for entertainment, explanation or expression. I wrote to empathize — both with myself and with the world. I’ve learned I’m not the only one. For millenniums, humans have told stories to connect, relate and weave imaginative truths that enable us to see one another more clearly with compassion and courage. Finding empathy is a difficult challenge but also the most human of the reasons we tell stories. Often, we explain and express so that we can be seen or so that others can empathize with us. Often, effective persuading means truly stepping into another’s point of view. Often, we entertain to bring joy and light not only to our audience but to ourselves as creators.

We tell stories because we are human. But we are also made more human because we tell stories. When we do this, we tap into an ancient power that makes us, and the world, more of who we are: a single race looking for reasons, searching for purpose, seeking to find ourselves.

Amanda Gorman is a poet and the author of “The Hill We Climb” and “Call Us What We Carry.”

Amy Chua: ‘To Build Dynasties of Meaning’

When my mother was 1, her family boarded a junk and left China forever. They were bound for the Philippines, where, in their new home, my grandmother enthralled her with spellbinding tales of drunken deities and wandering poets, of wise fools and talking animals, of the Yellow Emperor, the Great Wall and other glories of the magnificent 5,000-year-old civilization that was the Middle Kingdom.

When I was growing up in West Lafayette, Ind., my mother told me the same stories. But she also told me about her harrowing childhood living through the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. She described Japanese troops bayoneting babies and forcing one of her uncles to drink so much water he exploded. She recounted how her parents disguised her as a boy — I only realized much later that this was because they had heard so many horrific stories of what Japanese soldiers had done to young girls. And she recalled the exhilarating day when Gen. Douglas MacArthur liberated the Philippines and she and her friends ran after the American jeeps, cheering wildly as soldiers tossed out cans of Spam.

When I had my own two daughters, I told them all the stories my mother had told me. When they were 13 and 16, I wrote a book called “Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother” about how I was trying to raise them the same way my parents had raised me and why I asked so much of them, retelling stories of my daughters’ childhood from my perspective. The book was part love letter, part apology, part apologia. I never expected so many people to find my stories so hair-raising. But stories mean different things to different people. And they have a way of taking on a life of their own, generating more stories and counter-stories and meta-stories.

We tell stories for countless reasons: to delight and destroy, to arm and disarm, to comfort and crack up. These days, I love regaling my students with tales of rejection and humiliation from my younger days — mortifying total fails that still make my face burn. Stories can bridge chasms, connecting us in our common ridiculousness. Among outsiders, we tell stories to preserve, to transmit pride across generations, to build dynasties of meaning.

Amy Chua is a professor of law at Yale University and an author. Her most recent book is “Political Tribes: Group Instinct and the Fate of Nations.”

Wendell Pierce: ‘The Gateway to Truth-Telling’

“A man can’t go out the way he came in,” the character Willy Loman declares in Arthur Miller’s play “Death of a Salesman.” “A man has got to add up to something.”

With each performance I give in that role in the play’s current Broadway revival , I’m reminded it epitomizes the innate human desire to make a lasting impact in our world before we depart. As an artist, telling stories has always been a privilege for me, whether by recording music, narrating a documentary or becoming a character onscreen. To tell the story of our journeys gives our lives purpose, meaning and longevity, providing insight into the human condition that can be shared for generations and that carries the power to change perspectives.

Storytelling is also the gateway to truth-telling, which helps inform our opinions, decision-making and self-views. Sharing our stories allows us to come together, declare what our values are and act on them. Without storytelling, we would not have the layers of history that impact our present and influence the future. It’s impossible to imagine a world in which our ancestors did not share their journeys of enslavement, persecution, horror, honor, hope and triumph.

Think about what the landscape of storytelling in jazz — the idea of freedom and form coexisting in art — would be without the likes of Miles Davis, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong. There would be no Terence Blanchard, Cécile McLorin Salvant, Wynton Marsalis and all the musicians who’ve carried jazz into the present day. And when the coronavirus pandemic hit, storytelling became a revered place of comfort and creativity. We discovered new authors and auteurs, rediscovered film and TV favorites and attended virtual theatrical performances by companies worldwide.

I discovered my gateway to storytelling as a boy growing up in New Orleans inspired by the historic Free Southern Theater, and throughout my 40-year career I’ve developed a full appreciation of its power. Each time I step onstage or in front of a camera, I am building a relationship with the audience, hoping to leave them with their own story to tell once the experience has concluded.

Being onstage each day in “Death of a Salesman,” embodying the iconic role of Willy Loman, is not only a watershed moment in my life and career, but it also adds a necessary historic chapter that now leaves the door open for this story to be told by a multitude of diverse voices and artists. I hope that with each performance, we are burning down a house that has confined us, so that we, as artists, can build a bigger, more inclusive home — one that provides a nurturing space to celebrate the full richness of all our stories.

Wendell Pierce is an actor and recording artist. He currently stars in the Broadway revival of “Death of a Salesman.”

Liu Cixin: ‘A Thought Laboratory’

Telling stories — using the imagination to create virtual worlds outside of reality — is an important and unique human ability. So far there is no evidence that any other species on Earth has this power.

The virtual worlds that make up the essence of human storytelling may sometimes be similar to the real world, but they can also share little with it. The story must have enough similarity with the actual world for people to find touchpoints within it but be different enough to allow for exploration.

This virtual world — the story — serves many important functions. First, it is an extension of real life. People create or appreciate experiences in stories that can’t exist in reality. Therefore, humans can have spiritual and emotional encounters in this space that are not possible in other contexts.

Stories also allow people to understand the world from a different perspective. The virtual world formed by stories is a thought laboratory in which nature can operate in a variety of extreme states, allowing the storyteller to explore various theories and hypotheses about nature and its connection to humans. Exploring the limits of the natural world in this virtual setting can reveal aspects of its fundamental essence yet untested in reality.

Stories do not only exist in a virtual space. They can create real-world connections. When people read or hear the same story, they enter a shared virtual universe. This collective experience can lead to the construction of a connected community in real life, built on encounters within this virtual space.

Liu Cixin is a science fiction writer and the author of the Hugo Award-winning novel “The Three-Body Problem,” which is being adapted into a Netflix series.

Michelle Thaller: ‘The Universe Is a Story That Exists From Start to Finish’

The human mind is all about connections. A single neuron, thought or fact makes no sense; it’s the links and underlying maps we create that allow us to parse reality. Thousands of years ago, perhaps around a campfire, early storytellers must have discovered the previously hidden power of the human mind. Today, we latch onto stories as if our brains are hungry for them. They allow us to organize knowledge and pass it on to others. Storytelling may very well be what made us fully conscious.

A story is the progression from one point to another that makes sense of the facts and the events it contains. Allow your favorite book to fall open to any page and glance at the first sentence you see. Immediately, you will have access to the entirety of the story. You will know which events have come before, what character is speaking and how it will all end. An entirety of existence can be contained in a single point.

Reality may be nothing but connections. There may be no events or places, no space or time as we understand them. The universe may be similar to a hologram (no, this does not mean we are in some kind of computer simulation), and our perception of space and time may be part of a larger whole that we are unaware of. I made a hologram in college: a glass plate smeared with light-sensitive gel. I developed an image of a small vase of flowers and admired the three-dimensional effect when I shone a laser through the glass, turning the plate to see the flowers at different angles. Then, the instructor told me to break my plate with a hammer. Looking through a small, brittle shard of the original glass, I could still see the entire image. Every single point of a hologram contains every other part.

This is where the deep nature of stories is revealed. What we think of as a universe extending into space and time is just how our limited brains perceive an underlying structure of pure connection.

I like to think that the universe is a story that exists from start to finish, all at once. The page has fallen open to this moment you are experiencing now, but all the other pages still exist. The whole story is contained in every point, even the tiny point of space and time in which you are reading this. We are all in this story together, for all of space and time. Let’s try to make it a good one.

Dr. Michelle Thaller is an astronomer and science communicator. She works at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Fang Fang: ‘Our Most Kind and Enduring Companion’

As long as people breathe, they will speak, they will write, and they will tell stories.

Stories have existed even before humankind had the ability to narrate them. The interplay between people’s lives and their primitive emotions certainly led to the creation of all kinds of stories. Once humans began to interact and form social ties, these stories began to display their vividness and complexity, gradually revealing their function to entertain and educate.

No matter what stage humankind finds itself in, stories are always right beside us, becoming our most kind and enduring companions. From the earliest moments as babies when we begin to imitate sounds, we are already intently listening to stories. They come from our family, our neighbors, from the fields and the streets, from books. From these stories, we learn about principles like justice, rites, the nature of wisdom and what it means to have faith; we come to understand good and evil, civilization and culture, intelligence and ignorance.

Although the vehicle through which they are conveyed might change over time, the inner heart of these stories remains constant. During each stage of human existence, we see the recurrence of stories with similar themes. Birth, aging, sickness and death; the sadness of departure and the joy of reunion. These are universal experiences. But the details of how these themes are approached and narrated evolve during different eras and take on different forms depending on circumstances like background, race and gender.

Countless individual stories come together to form the collective story of all human knowledge and emotion. Some stories are short, others are long, and some are unclear and incomplete — but they are all a part of our evolution. As we move through life, we, too, become storytellers. As our lives ascend like a spiral, so, too, our stories are constantly elevated.

Fang Fang is a writer and a Lu Xun Literary Prize winner. She is the author of “Wuhan Diary: Dispatches From a Quarantined City.”

This essay was translated from the Chinese by Michael Berry.

Hikaru Nakamura: ‘The Story of Chess Is a Broader Human Story’

I tell stories because, as a Twitch streamer , I’m expected to be an entertainer. On the surface, people tune in to my stream to watch me play chess, but if there were no story to tell about the moves I make, I might as well be a computer program. I have to enhance — or create — the drama in the game to keep the attention of my fans and generate more interest.

In my streams, I tell stories about chess, chess tournaments, historical events and games. I also make myself a character in the story of chess. After all, in my experience, only a few hundred people can tolerate a dry analysis of strings of chess moves, but hundreds of thousands want to hear that your opponent kept kicking you under the table or that his breath was so hideous it distracted you. In this way, the story of chess is a broader human story. Even people who don’t know much about the game can connect with a player who has faced off against an unlikable rival, experienced a painful loss or pulled off a dramatic, come-from-behind victory.

For those of us who love chess, however, telling stories about the game serves another purpose. Recounting competitions and the experiences of chess players allows those in local clubs to imagine a world beyond their small circle of regular opponents. They can envision themselves as part of a huge global community made up of colorful, talented people who may speak different languages and come from diverse cultures but can still communicate via chess moves.

The stories that I tell about chess may have universal themes, but they come from a deeply personal place. When I talk about the people who taught me, who surprised me, who showed me special things about chess, I stay connected to the part of me that loves this game. These stories encourage me to look for new ideas and more beautiful themes in the chess moves, discovering new things about the game — and about myself.

Hikaru Nakamura is a chess grandmaster, one of the world’s top blitz chess players, a five-time U.S. chess champion and the most popular chess personality on Twitch and YouTube.

Naomi Watanabe: ‘Stories Are Life’s Inheritance’

There are as many stories as there are people. I want to know and learn from as many stories as possible. As a performer onstage and onscreen, I encounter different types of individuals and listen to their accounts. I want to hear about their adventures and understand how they live and what they are feeling.

Stories provide opportunities to see the world in different ways. Each of us brings a unique background to the table. It can be challenging to step out of our bubbles and embrace other perspectives. But life is short, so I want to pick up on everyone’s insight into what is happening in the world around me.

My story isn’t just made up of my singular life experiences; everyone’s tales blend into mine and become part of my story. These tales from others can help us find purpose and bring fullness to our lives — if we choose to learn from them. That’s why I want to treasure everyone’s narratives.

These narratives allow us to step outside ourselves and view our realities with renewed vigor. Think of life as a buffet, and you get to sample bits of what it has to offer. You may sometimes realize, “I wanted to eat this, but now I want to try this instead.” You leave that buffet with a full plate, strewn with dishes you may not otherwise have sampled. The same holds true in our everyday lives. But unfortunately, we often get so caught up focusing on the big picture that we forget the smaller, yet equally valuable, moments that shape our stories. That’s why I try to post on Instagram. I use social media to record and share what I encounter in my daily life.

Stories are life’s inheritance. They unfold every day, every minute and every second. Stories leave us with a wealth of collective experiences, and if we choose to open our hearts and minds to these indispensable heirlooms, they will deeply enrich our lives.

Naomi Watanabe is a comedian.

Christopher Wheeldon: ‘The Tormented Tempest of the Human Condition’

We tell stories because it’s easier to comprehend deep truths through myths, legends and universal ideas. Because music and movement are universal, even primordial, the deep part of us that understands the arc of a story is particularly illuminated by dance.

One expects all the drama in a story ballet to emerge through the union of steps and music. But a moment without motion can also be powerful. Take the third act of Sir Kenneth MacMillan’s classic production of the ballet “Romeo and Juliet.” After Tybalt’s murder at Romeo’s hands, and as Juliet faces a forced marriage to Paris, MacMillan chooses stillness to describe Juliet’s torment.

After so expertly expressing the tempestuous passions of the protagonists through a marriage of classical ballet steps driven by Sergei Prokofiev’s score, MacMillan chooses to show us the swirling machinations of Juliet’s mind by simply sitting Juliet at the end of her bed. She does not move, her toes resting together on pointe. Even her gaze is hauntingly fixed, allowing the tumult of the tumbling strings and discordant brass line to narrate Juliet’s thoughts as her emotional spiral comes into focus.

Every pirouette, every carried lift, has brought us to this moment where stillness reigns. It is a beautiful example of how movement — and the spaces in between — resonate with us on a deeply emotional level. Dance can convey fear, love or joy, or even go deeper into the tormented tempest of the human condition.

Christopher Wheeldon is a choreographer and director, most recently of “MJ: The Musical.”

Diana Gabaldon: ‘How We Make Ourselves Whole’

We tell stories because we need to see patterns. Everyone asks me, “How did you get from being a scientist to being a novelist?”

“Wrote a book,” I reply, shrugging. “They don’t make you get a license.”

Art and science aren’t different things, you know; they’re two faces of the same coin. And what makes a good writer — or any other sort of artist — is the same thing that makes a good scientist: the ability to perceive patterns within what looks like chaos.

A scientist observes the external world and works by circumscribing a small quantity of chaos (say, in an ecosystem, planetology, an organism or molecular structures) and divining its patterns. An artist does something similar, but draws from the internal world of their personal chaos.

Patterns are the logic of both the material and the spiritual worlds, and stories are how we make that logic evident to one another. Each pattern explains and connects, fills in a blank, and provides a steppingstone to something more.

Stories are how we make ourselves whole.

Diana Gabaldon is an author. Her most recent novel is “Go Tell the Bees That I Am Gone,” the ninth installment in the Outlander series.

Advertisement

Ideas and insights from Harvard Business Publishing Corporate Learning

What Makes Storytelling So Effective For Learning?

This is the second of two posts co-written by Vanessa and Lani Peterson, Psy.D., a psychologist, professional storyteller and executive coach.

Telling stories is one of the most powerful means that leaders have to influence, teach, and inspire. What makes storytelling so effective for learning? For starters, storytelling forges connections among people, and between people and ideas. Stories convey the culture, history, and values that unite people. When it comes to our countries, our communities, and our families, we understand intuitively that the stories we hold in common are an important part of the ties that bind.

This understanding also holds true in the business world, where an organization’s stories, and the stories its leaders tell, help solidify relationships in a way that factual statements encapsulated in bullet points or numbers don’t.

Connecting learners Good stories do more than create a sense of connection. They build familiarity and trust, and allow the listener to enter the story where they are, making them more open to learning. Good stories can contain multiple meanings so they’re surprisingly economical in conveying complex ideas in graspable ways. And stories are more engaging than a dry recitation of data points or a discussion of abstract ideas. Take the example of a company meeting.

At Company A, the leader presents the financial results for the quarter. At Company B, the leader tells a rich story about what went into the “win” that put the quarter over the top. Company A employees come away from the meeting knowing that they made their numbers. Company B employees learned about an effective strategy in which sales, marketing, and product development came together to secure a major deal. Employees now have new knowledge, new thinking, to draw on. They’ve been influenced. They’ve learned.

Something for everyone Another storytelling aspect that makes it so effective is that it works for all types of learners. Paul Smith, in “Leader as Storyteller: 10 Reasons It Makes a Better Business Connection”, wrote:

In any group, roughly 40 percent will be predominantly visual learners who learn best from videos, diagrams, or illustrations. Another 40 percent will be auditory, learning best through lectures and discussions. The remaining 20 percent are kinesthetic learners, who learn best by doing, experiencing, or feeling. Storytelling has aspects that work for all three types. Visual learners appreciate the mental pictures storytelling evokes. Auditory learners focus on the words and the storyteller’s voice. Kinesthetic learners remember the emotional connections and feelings from the story.

Stories stick Storytelling also helps with learning because stories are easy to remember. Organizational psychologist Peg Neuhauser found that learning which stems from a well-told story is remembered more accurately, and for far longer, than learning derived from facts and figures. Similarly, psychologist Jerome Bruner’s research suggest that facts are 20 times more likely to be remembered if they’re part of a story.

Kendall Haven, author of Story Proof and Story Smart, considers storytelling serious business for business. He has written:

Your goal in every communication is to influence your target audience (change their current attitudes, belief, knowledge, and behavior). Information alone rarely changes any of these. Research confirms that well-designed stories are the most effective vehicle for exerting influence.

Stories about professional mistakes and what leaders learned from them are another great avenue for learning. Because people identify so closely with stories, imagining how they would have acted in similar circumstances, they’re able to work through situations in a way that’s risk free. The extra benefit for leaders: with a simple personal story they’ve conveyed underlying values, offered insight into the evolution of their own experience and knowledge, presented themselves as more approachable, AND most likely inspired others to want to know more.

Connection. Engagement. Appealing to all sorts of learners. Risk-free learning. Inspiring motivation. Conveying learning that sticks. It’s no wonder that more and more organizations are embracing storytelling as an effective way for their leaders to influence, inspire, and teach.

Read more about the power of storytelling in our brief, “ Telling Stories: How Leaders Can Influence, Teach, and Inspire ”

Vanessa Boris is Senior Manager, Video Solutions at Harvard Business Publishing Corporate Learning. Email her at [email protected]

Let’s talk

Change isn’t easy, but we can help. Together we’ll create informed and inspired leaders ready to shape the future of your business.

© 2024 Harvard Business School Publishing. All rights reserved. Harvard Business Publishing is an affiliate of Harvard Business School.

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Information

- Terms of Use

- About Harvard Business Publishing

- Higher Education

- Harvard Business Review

- Harvard Business School

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience. By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Cookie and Privacy Settings

We may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

You can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

- human behavior

How Telling Stories Makes Us Human

O dds are, you’ve never heard the story of the wild pig and the seacow — but if you’d heard it, you’d be unlikely to forget it. The wild pig and seacow were best friends who enjoyed racing each other for sport. One day, however, the seacow hurt his legs and could run no more. So the wild pig carried him down to the sea, where they could race forever, side by side, one in the water, one on the land.

You can learn a lot from a tale like that — about friendship, cooperation, empathy and an aversion to inequality. And if you were a child in the Agta community — a hunter-gatherer population in The Philippines’ Isabela Province — you’d have grown up on the story, and on many others that teach similar lessons. The Agta are hardly the only peoples who practice storytelling; the custom has been ubiquitous in all cultures over all eras in all parts of the world. Now, a new study in Nature Communications , helps explain why: storytelling is a powerful means of fostering social cooperation and teaching social norms, and it pays valuable dividends to the storytellers themselves, improving their chances of being chosen as social partners, receiving community support and even having healthy offspring.

The researchers, led by anthropologist Daniel Smith of University College London, began their work by conducting a literature search of 89 different stories told by seven different forager cultures in Thailand, Malaysia, Africa and elsewhere. All of the tales carried lessons about social cooperation, empathy and justice, and many taught sexual equality too. The researchers then turned their attention specifically to the Agta, focusing on two communities, with a total of roughly 1,250 people, and conducted a number of experiments to determine the power and purpose of storytelling.

In the first experiment, the investigators asked 297 people across 18 villages in the two communities to vote for the best storytellers in their group. There was no limit on the number of people they could name. The votes in each of the camps were tallied, with higher overall scores taken as an indicator of a camp with more and better storytellers.

A different 290 people in the same camps were then asked to play a resource allocation game, in which people were given up to 12 tokens, each of which could be exchanged for about an eighth of a kilo of rice. They were told they could either keep all of the tokens or give as many as they wished to any or all of up to 12 other residents of the camp the researchers secretly chose. All of the subjects made their decisions privately, in the presence of only the researchers. (At the end of the experiment, all of the rice was distributed to all of the villagers according to the choices the subjects had made.)

Perhaps not surprisingly, the subjects kept an average of 62.6% of the rice tokens for themselves. But the actual total changed camp-to-camp, with every 1% advantage in the number of good storytellers in any community associated with a 2.2% increase in the amount of rice given away in the game. The more good storytellers in a village, in other words, the more generous people were. It is impossible to say definitively that the two were connected, but the fact remained, as the researchers wrote, that “Camps with a greater proportion of skilled storytellers, were associated with increased levels of cooperation.”

In the second experiment, 291 people in the same 18 camps were asked to name a maximum of five people in their own community with whom they would be happy to live. Of the 857 people who were named, those who had been designated as good storytellers in the previous experiment were nearly twice as likely to be chosen as those who weren’t. Remarkably, storytellers were chosen over people who had equally good reputations for hunting, fishing and foraging — which at least suggests that human beings may sometimes prize hearing an especially good story over eating an especially good meal.

Of course, nothing captures natural selection quite like the number of babies any one person has, and storytelling confers that benefit too — at least on the tellers. “Storytelling is a costly behavior,” write the researchers, “requiring an input of time and energy into practice, performance and cognitive processing.” But the payoff for making such an effort is big: When the investigators looked at family groups within the 18 camps, they found that skilled storytellers had, on average, .53 more living children than other people.

One reason for that is obvious: if you’re popular — and storytellers are — you’re more likely to have a partner. Another potential explanation is that the rest of the community is inclined to look favorably on the storyteller’s family and extend help when needed in the form of childcare, pitching in to look after a sick family member, or even offering financial or material support when necessary. Significantly, in the resource sharing game, it was storytellers who were likeliest to be recipients of rice. In the real world, all of this community support gives the children of the storyteller a small but real survival edge.

The investigators concede that one study is by no means conclusive and that further work needs to be conducted. That would especially include longitudinal studies in which the composition and welfare of camps with and without good storytellers is tracked over decades and generations. Over the course of those generations, of course, many more Agta children will continue to hear many more instructive stories: of the sun and the moon — a man and a woman — who fight to a draw in their battle for the sky and choose to cooperate to share the day and the night; of the monkey who became a hero for killing a giant, but was kept wise and humble with the knowledge that all monkeys — even him — must still fear the eagle. All of the stories will merely be make-believe — and all of them will be much more than that too.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at [email protected]

Why Storytelling Is a Pillar of a Meaningful Life

- Family storytelling weaves lives of connection, meaning, and purpose.

Posted July 6, 2022 | Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

- Listening to others’ stories helps us tell our own stories in new ways.

- Storytelling is one of the pillars of building a meaningful life because stories are, at heart, about meaning and connection.

Is there more to life than being happy?

This is the question that Emily Esfahani Smith asks in her book, The Power of Meaning: Finding Fulfillment in a World Obsessed with Happiness . Building on the tenets of positive psychology, Smith argues that, whereas happiness is fleeting, a momentary state of feeling good, building a life of meaning creates an enduring sense of well-being.

How are we to build a life of meaning? Smith suggests four pillars: belonging, purpose, transcendence, and storytelling. The first three make intuitive sense: a sense of belonging through loving others and being loved, a sense of purpose that one is accomplishing something in their life, a sense of transcendence, of simply being in the moment. These have been written about in philosophy , psychology, and self-help literature for years.

But storytelling? How is telling stories a pillar of a meaningful life?

Smith focuses on stories we tell about ourselves–how we create stories that explain who we are and how we became this way, what the psychologist Dan McAdams calls a narrative identity . Narrative identity weaves our various life experiences into a coherent story that not only links experiences into temporal and causal chains but creates meaning through the expression of values and ideals.

As Smith argues, we can change our stories; we can create stories that affirm positive values and create meaning and purpose. But for many of us who have faced obstacles and challenges in life, changing our story may not be as easy as it sounds. How do we create positive meaning and purpose from experiences of hardship and stress ?

Smith’s own story points to a way. In telling her story, she relies on the stories of two other people. First, she tells the story of a young football player who was seriously injured and initially told his story as one of loss and desolation, what McAdams calls a “contamination story”—things were good and now are bad.

But this young man changed his story; through personal reflection and reframing, his story became one of finding new values, of discovering his purpose in life as a youth mentor, what McAdams calls a “redemption” story, good things came from the bad.

Smith tells the second story about her father, who lived a simple life as a carpenter and a Sufi. When he had a massive heart attack and needed surgery, as he was going under anesthesia, instead of counting down from 100, he counted off the names of his children because this reminded him of his purpose and meaning, his reason to live.

But how do we reframe our experiences to be redemptive? That Smith finds a way forward, and a way to frame her own story through the stories of others underscores that our own stories are not solely our own; our stories are interwoven with the stories of others. Through hearing, listening, and sharing others’ stories, we come to tell our own stories in new ways, to reframe our own stories to create more redemptive meanings.

Research from the Family Narratives Lab indicates that family stories, stories of our parents and grandparents, may be especially effective in providing models of how to live a meaningful life. Adolescents and young adults who know more stories and more coherent and detailed stories about their parents growing up and their family history show higher levels of self-esteem , less anxiety , and, yes, higher levels of meaning and purpose in life. Why might this be?

Stories are how we understand human experience and make sense of what can sometimes be senseless events. Stories provide coherent frameworks for expressing values and ideals. And family stories may be especially important because adolescents and young adults identify with their family members.

Even when they might not be getting along, this is the family in which one is embedded and has shared a life. When adolescents hear stories about family members struggling with difficult times and challenges and obstacles, they learn that life is not always about the good times; it is about striving for something better, fighting for beliefs, and overcoming the odds.

Storytelling is one of the pillars of building a meaningful life because stories are, at heart, about meaning and connection. Our personal stories live within a world of stories, stories of distant others, friends, and family. We can create meaningful stories for ourselves because we have meaningful stories about others as models and inspiration.

And in telling our stories, we help others create meaning in their lives. And it starts in the family. Family storytelling, even of the mundane experiences of our lives, weaves lives of connection, meaning, and purpose. Happiness may come and go, but stories live forever.

Smith, E. E. (2017). The power of meaning: Finding fulfillment in a world obsessed with happiness. Crown.

McAdams, D. P. (2015). The redemptive self: Generativity and the stories Americans live by. In Research in human development (pp. 81-100). Psychology Press.

Robyn Fivush, Ph.D. is the Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Developmental Psychology at Emory University and the director of the Family Narratives Lab.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Get science-backed answers as you write with Paperpal's Research feature

What is a Narrative Essay? How to Write It (with Examples)

Narrative essays are a type of storytelling in which writers weave a personal experience into words to create a fascinating and engaging narrative for readers. A narrative essay explains a story from the author’s point of view to share a lesson or memory with the reader. Narrative essays, like descriptive essays , employ figurative language to depict the subject in a vivid and creative manner to leave a lasting impact on the readers’ minds. In this article, we explore the definition of narrative essays, list the key elements to be included, and provide tips on how to craft a narrative that captivates your audience.

Table of Contents

What is a narrative essay, choosing narrative essay topics, key elements in a narrative essay, creating a narrative essay outline, types of narrative essays, the pre-writing stage, the writing stage, the editing stage, narrative essay example, frequently asked questions.

Narrative essays are often based on one’s personal experience which allows the author to express himself/herself in compelling ways for the reader. They employ storytelling elements to convey the plot and captivate the reader while disclosing the story’s theme or purpose. The author must always have a purpose or theme in mind when writing a narrative essay. These essays may be assigned to high school students to assess their ability to create captivating stories based on personal experiences, or they may be required as part of a college application to assess the applicant’s personal traits. Narrative essays might be based on true events with minor tweaks for dramatic purposes, or they can be adapted from a fictional scenario. Whatever the case maybe, the goal is to tell a story, a good story!

In narrative essays, the emphasis is not so much on the narrative itself as it is on how you explain it. Narrative essay topics cover a range of experiences, from noteworthy to mundane, but when storytelling elements are used well, even a simple account can have weight. Notably, the skills required for narrative writing differ significantly from those needed for formal academic essays, and we will delve deeper into this in the next section.

You can talk about any narrative, but consider whether it is fascinating enough, has enough twists and turns, or teaches a lesson (It’s a plus if the story contains an unexpected twist at the end). The potential topics for a narrative essay are limitless—a triumphant story, a brief moment of introspection, or a voyage of self-discovery. These essays provide writers with the opportunity to share a fragment of their lives with the audience, enriching both the writer’s and the reader’s experiences. Narrative essay examples could be a write-up on “What has been your biggest achievement in life so far and what did it teach you?” or “Describe your toughest experience and how you dealt with it?”.

While narrative essays allow you to be creative with your ideas, language, and format, they must include some key components to convey the story clearly, create engaging content and build reader interest. Follow these guidelines when drafting your essay:

- Tell your story using the first person to engage users.

- Use sufficient sensory information and figurative language.

- Follow an organized framework so the story flows chronologically.

- Include interesting plot components that add to the narrative.

- Ensure clear language without grammar, spelling, or word choice errors.

Narrative essay outlines serve as the foundational structure for essay composition, acting as a framework to organize thoughts and ideas prior to the writing process. These outlines provide writers with a means to summarize the story, and help in formulating the introduction and conclusion sections and defining the narrative’s trajectory.

Unlike conventional essays that strictly adhere to the five-paragraph structure, narrative essays allow for more flexibility as the organization is dictated by the flow of the story. The outline typically encompasses general details about the events, granting writers the option to prioritize writing the body sections first while deferring the introduction until later stages of the writing process. This approach allows for a more organic and fluid writing process. If you’re wondering how to start writing a narrative essay outline, here is a sample designed to ensure a compelling and coherent narrative:

Introduction

- Hook/Opening line: The introduction should have an opening/hook sentence that is a captivating quote, question, or anecdote that grabs the reader’s attention.

- Background: Briefly introduce the setting, time, tone, and main characters.

- Thesis statement: State clearly the main theme or lesson acquired from the experience.

- Event 1 (according to occurrence): Describe the first major event in detail. Introduce the primary characters and set the story context; include sensory elements to enrich the narrative and give the characters depth and enthusiasm.

- Event 2: Ensure a smooth transition from one event to the next. Continue with the second event in the narrative. For more oomph, use suspense or excitement, or leave the plot with cliffhanger endings. Concentrate on developing your characters and their relationships, using dialog to bring the story to life.

- Event 3: If there was a twist and suspense, this episode should introduce the climax or resolve the story. Keep the narrative flowing by connecting events logically and conveying the feelings and reactions of the characters.

- Summarize the plot: Provide a concise recap of the main events within the narrative essay. Highlight the key moments that contribute to the development of the storyline. Offer personal reflections on the significance of the experiences shared, emphasizing the lasting impact they had on the narrator. End the story with a clincher; a powerful and thought-provoking sentence that encapsulates the essence of the narrative. As a bonus, aim to leave the reader with a memorable statement or quote that enhances the overall impact of the narrative. This should linger in the reader’s mind, providing a satisfying and resonant conclusion to the essay.

There are several types of narrative essays, each with their own unique traits. Some narrative essay examples are presented in the table below.

How to write a narrative essay: Step-by-step guide

A narrative essay might be inspired by personal experiences, stories, or even imaginary scenarios that resonate with readers, immersing them in the imaginative world you have created with your words. Here’s an easy step-by-step guide on how to write a narrative essay.

- Select the topic of your narrative

If no prompt is provided, the first step is to choose a topic to write about. Think about personal experiences that could be given an interesting twist. Readers are more likely to like a tale if it contains aspects of humor, surprising twists, and an out-of-the-box climax. Try to plan out such subjects and consider whether you have enough information on the topic and whether it meets the criteria of being funny/inspiring, with nice characters/plot lines, and an exciting climax. Also consider the tone as well as any stylistic features (such as metaphors or foreshadowing) to be used. While these stylistic choices can be changed later, sketching these ideas early on helps you give your essay a direction to start.

- Create a framework for your essay

Once you have decided on your topic, create an outline for your narrative essay. An outline is a framework that guides your ideas while you write your narrative essay to keep you on track. It can help with smooth transitions between sections when you are stuck and don’t know how to continue the story. It provides you with an anchor to attach and return to, reminding you of why you started in the first place and why the story matters.

- Compile your first draft

A perfect story and outline do not work until you start writing the draft and breathe life into it with your words. Use your newly constructed outline to sketch out distinct sections of your narrative essay while applying numerous linguistic methods at your disposal. Unlike academic essays, narrative essays allow artistic freedom and leeway for originality so don’t stop yourself from expressing your thoughts. However, take care not to overuse linguistic devices, it’s best to maintain a healthy balance to ensure readability and flow.

- Use a first-person point of view

One of the most appealing aspects of narrative essays is that traditional academic writing rules do not apply, and the narration is usually done in the first person. You can use first person pronouns such as I and me while narrating different scenarios. Be wary of overly using these as they can suggest lack of proper diction.

- Use storytelling or creative language

You can employ storytelling tactics and linguistic tools used in fiction or creative writing, such as metaphors, similes, and foreshadowing, to communicate various themes. The use of figurative language, dialogue, and suspense is encouraged in narrative essays.

- Follow a format to stay organized

There’s no fixed format for narrative essays, but following a loose format when writing helps in organizing one’s thoughts. For example, in the introduction part, underline the importance of creating a narrative essay, and then reaffirm it in the concluding paragraph. Organize your story chronologically so that the reader can follow along and make sense of the story.

- Reread, revise, and edit

Proofreading and editing are critical components of creating a narrative essay, but it can be easy to become weighed down by the details at this stage. Taking a break from your manuscript before diving into the editing process is a wise practice. Stepping away for a day or two, or even just a few hours, provides valuable time to enhance the plot and address any grammatical issues that may need correction. This period of distance allows for a fresh perspective, enabling you to approach the editing phase with renewed clarity and a more discerning eye.

One suggestion is to reconsider the goals you set out to cover when you started the topic. Ask yourself these questions:

- Is there a distinct beginning and end to your story?

- Does your essay have a topic, a memory, or a lesson to teach?

- Does the tone of the essay match the intended mood?

Now, while keeping these things in mind, modify and proofread your essay. You can use online grammar checkers and paraphrase tools such as Paperpal to smooth out any rough spots before submitting it for publication or submission.

It is recommended to edit your essay in the order it was written; here are some useful tips:

- Revise the introduction

After crafting your narrative essay, review the introduction to ensure it harmonizes with the developed narrative. Confirm that it adeptly introduces the story and aligns seamlessly with the conclusion.

- Revise the conclusion and polish the essay

The conclusion should be the final element edited to ensure coherence and harmony in the entire narrative. It must reinforce the central theme or lesson outlined initially.

- Revise and refine the entire article

The last step involves refining the article for consistent tone, style, and tense as well as correct language, grammar, punctuation, and clarity. Seeking feedback from a mentor or colleague can offer an invaluable external perspective at this stage.

Narrative essays are true accounts of the writer’s personal experiences, conveyed in figurative language for sensory appeal. Some narrative essay topic examples include writing about an unforgettable experience, reflecting on mistakes, or achieving a goal. An example of a personal narrative essay is as follows:

Title: A Feline Odyssey: An Experience of Fostering Stray Kittens

Introduction:

It was a fine summer evening in the year 2022 when a soft meowing disrupted the tranquility of my terrace. Little did I know that this innocent symphony would lead to a heartwarming journey of compassion and companionship. Soon, there was a mama cat at my doorstep with four little kittens tucked behind her. They were the most unexpected visitors I had ever had.

The kittens, just fluffs of fur with barely open eyes, were a monument to life’s fragility. Their mother, a street-smart feline, had entrusted me with the care of her precious offspring. The responsibility was sudden and unexpected, yet there was an undeniable sense of purpose in the air , filling me with delight and enthusiasm.

As the days unfolded, my terrace transformed into a haven for the feline family. Cardboard boxes became makeshift cat shelters and my once solitary retreat was filled with purrs and soothing meows. The mother cat, Lily, who initially observ ed me from a safe distance, gradually began to trust my presence as I offered food and gentle strokes.

Fostering the kittens was a life-changing , enriching experience that taught me the true joy of giving as I cared for the felines. My problems slowly faded into the background as evenings were spent playing with the kittens. Sleepless nights turned into a symphony of contented purring, a lullaby filled with the warmth of trust and security . Although the kittens were identical, they grew up to have very distinct personalities, with Kuttu being the most curious and Bobo being the most coy . Every dawn ushered in a soothing ritual of nourishing these feline companions, while nights welcomed their playful antics — a daily nocturnal delight.

Conclusion:

As the kittens grew, so did the realization that our paths were destined to part. Finally, the day arrived when the feline family, now confident and self-reliant, bid farewell to my terrace. It was a bittersweet moment, filled with a sense of love and accomplishment and a tinge of sadness.

Fostering Kuttu, Coco, Lulu, and Bobo became one of the most transformative experiences of my life. Their arrival had brought unexpected joy, teaching me about compassion and our species’ ability to make a difference in the world through love and understanding. The terrace, once a quiet retreat, now bore the echoes of a feline symphony that had touched my heart in ways I could have never imagined.

The length of a narrative essay may vary, but it is typically a brief to moderate length piece. Generally, the essay contains an introductory paragraph, two to three body paragraphs (this number can vary), and a conclusion. The entire narrative essay could be as short as five paragraphs or much longer, depending on the assignment’s requirements or the writer’s preference.

You can write a narrative essay when you have a personal experience to share, or a story, or a series of events that you can tell in a creative and engaging way. Narrative essays are often assigned in academic settings as a form of writing that allows students to express themselves and showcase their storytelling skills. However, you can also write a narrative essay for personal reflection, entertainment, or to communicate a message.

A narrative essay usually follows a three-part structure: – Introduction (To set the stage for the story) – Body paragraphs (To describe sequence of events with details, descriptions, and dialogue) – Conclusion (To summarize the story and reflect on the significance)

Paperpal is an AI academic writing assistant that helps authors write better and faster with real-time writing suggestions and in-depth checks for language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of published scholarly articles and 20+ years of STM experience, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to Paperpal Copilot and premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks, submission readiness and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

Webinar: how to use generative ai tools ethically in your academic writing.

- 7 Ways to Improve Your Academic Writing Process

- Chemistry Terms: 7 Commonly Confused Words in Chemistry Manuscripts

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

What is a Descriptive Essay? How to Write It (with Examples)

You may also like, what is academic writing: tips for students, what is hedging in academic writing , how to use ai to enhance your college..., how to use paperpal to generate emails &..., ai in education: it’s time to change the..., is it ethical to use ai-generated abstracts without..., do plagiarism checkers detect ai content, word choice problems: how to use the right..., how to avoid plagiarism when using generative ai..., what are journal guidelines on using generative ai....

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.1 Narration

Learning objectives.

- Determine the purpose and structure of narrative writing.

- Understand how to write a narrative essay.

Rhetorical modes simply mean the ways in which we can effectively communicate through language. This chapter covers nine common rhetorical modes. As you read about these nine modes, keep in mind that the rhetorical mode a writer chooses depends on his or her purpose for writing. Sometimes writers incorporate a variety of modes in any one essay. In covering the nine modes, this chapter also emphasizes the rhetorical modes as a set of tools that will allow you greater flexibility and effectiveness in communicating with your audience and expressing your ideas.

The Purpose of Narrative Writing

Narration means the art of storytelling, and the purpose of narrative writing is to tell stories. Any time you tell a story to a friend or family member about an event or incident in your day, you engage in a form of narration. In addition, a narrative can be factual or fictional. A factual story is one that is based on, and tries to be faithful to, actual events as they unfolded in real life. A fictional story is a made-up, or imagined, story; the writer of a fictional story can create characters and events as he or she sees fit.

The big distinction between factual and fictional narratives is based on a writer’s purpose. The writers of factual stories try to recount events as they actually happened, but writers of fictional stories can depart from real people and events because the writers’ intents are not to retell a real-life event. Biographies and memoirs are examples of factual stories, whereas novels and short stories are examples of fictional stories.

Because the line between fact and fiction can often blur, it is helpful to understand what your purpose is from the beginning. Is it important that you recount history, either your own or someone else’s? Or does your interest lie in reshaping the world in your own image—either how you would like to see it or how you imagine it could be? Your answers will go a long way in shaping the stories you tell.

Ultimately, whether the story is fact or fiction, narrative writing tries to relay a series of events in an emotionally engaging way. You want your audience to be moved by your story, which could mean through laughter, sympathy, fear, anger, and so on. The more clearly you tell your story, the more emotionally engaged your audience is likely to be.

On a separate sheet of paper, start brainstorming ideas for a narrative. First, decide whether you want to write a factual or fictional story. Then, freewrite for five minutes. Be sure to use all five minutes, and keep writing the entire time. Do not stop and think about what to write.

The following are some topics to consider as you get going:

The Structure of a Narrative Essay

Major narrative events are most often conveyed in chronological order , the order in which events unfold from first to last. Stories typically have a beginning, a middle, and an end, and these events are typically organized by time. Certain transitional words and phrases aid in keeping the reader oriented in the sequencing of a story. Some of these phrases are listed in Table 10.1 “Transition Words and Phrases for Expressing Time” . For more information about chronological order, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” and Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” .

Table 10.1 Transition Words and Phrases for Expressing Time

The following are the other basic components of a narrative:

- Plot . The events as they unfold in sequence.

- Characters . The people who inhabit the story and move it forward. Typically, there are minor characters and main characters. The minor characters generally play supporting roles to the main character, or the protagonist .

- Conflict . The primary problem or obstacle that unfolds in the plot that the protagonist must solve or overcome by the end of the narrative. The way in which the protagonist resolves the conflict of the plot results in the theme of the narrative.

- Theme . The ultimate message the narrative is trying to express; it can be either explicit or implicit.

Writing at Work

When interviewing candidates for jobs, employers often ask about conflicts or problems a potential employee has had to overcome. They are asking for a compelling personal narrative. To prepare for this question in a job interview, write out a scenario using the narrative mode structure. This will allow you to troubleshoot rough spots, as well as better understand your own personal history. Both processes will make your story better and your self-presentation better, too.

Take your freewriting exercise from the last section and start crafting it chronologically into a rough plot summary. To read more about a summary, see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” . Be sure to use the time transition words and phrases listed in Table 10.1 “Transition Words and Phrases for Expressing Time” to sequence the events.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your rough plot summary.

Writing a Narrative Essay

When writing a narrative essay, start by asking yourself if you want to write a factual or fictional story. Then freewrite about topics that are of general interest to you. For more information about freewriting, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

Once you have a general idea of what you will be writing about, you should sketch out the major events of the story that will compose your plot. Typically, these events will be revealed chronologically and climax at a central conflict that must be resolved by the end of the story. The use of strong details is crucial as you describe the events and characters in your narrative. You want the reader to emotionally engage with the world that you create in writing.

To create strong details, keep the human senses in mind. You want your reader to be immersed in the world that you create, so focus on details related to sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch as you describe people, places, and events in your narrative.

As always, it is important to start with a strong introduction to hook your reader into wanting to read more. Try opening the essay with an event that is interesting to introduce the story and get it going. Finally, your conclusion should help resolve the central conflict of the story and impress upon your reader the ultimate theme of the piece. See Chapter 15 “Readings: Examples of Essays” to read a sample narrative essay.

On a separate sheet of paper, add two or three paragraphs to the plot summary you started in the last section. Describe in detail the main character and the setting of the first scene. Try to use all five senses in your descriptions.

Key Takeaways

- Narration is the art of storytelling.

- Narratives can be either factual or fictional. In either case, narratives should emotionally engage the reader.

- Most narratives are composed of major events sequenced in chronological order.

- Time transition words and phrases are used to orient the reader in the sequence of a narrative.

- The four basic components to all narratives are plot, character, conflict, and theme.

- The use of sensory details is crucial to emotionally engaging the reader.

- A strong introduction is important to hook the reader. A strong conclusion should add resolution to the conflict and evoke the narrative’s theme.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

The Power of Story

Storytelling Workshops

Power of Story

People remember how stories make them feel, and are more inspired to take action than if they just heard facts and figures.

The classic storytellers, the modern storytellers.

Much like our ancestors telling stories around a communal fire, Explorers come back from their sojourns with a tale to tell. Unlike legends of yore, their stories are grounded in scientific fact, but told with as much heart as ever.

Jahawi Bertolli

Malaika Vaz

Explorer Malaika Vaz is producing an upcoming feature documentary, Sacrifice Zone , that investigates the global impact of the world's largest, most profitable extractive industries—oil and gas, plastic, fast-fashion and coal—on communities of color in India, Colombia, Bangladesh and the United States. Aimed at shifting the narrative on environmental responsibility from consumer guilt to corporate accountability, the film examines the link between racial inequity and environmental exploitation, and the nexus between corporate power and government, and shines a light on the frontline communities fighting for justice.

Luján Agusti

Prasenjeet Yadav

For over a century, India has led global tiger conservation, doubling its tiger populations. But hunting and growing human settlements have cost tigers most of their historic range and isolated them in small areas that are not connected with other tiger populations. Explorer Prasenjeet Yadav is documenting the story of six “tiger islands” in India, showing the importance of connectivity and genetic diversity to ensure the tigers' future.

Laurel Chor

The National Geographic Storytellers Collective continues the timeless tradition of storytelling by showing how to structure narratives to open hearts and change minds.

Photo credits: Karabo Moilwa, Aaron Huey, Elke Bertolli, Luis Antonio Rojas, Nitye Sood, Joshua Irwandi, Jerome Favre, Shashank Dalvi

Writing for Success

Learning Objectives

- Determine the purpose and structure of narrative writing.

- Understand how to write a narrative essay.

THE PURPOSE OF NARRATIVE WRITING

Narration means the art of storytelling, and the purpose of narrative writing is to tell stories. Any time you tell a story to a friend or family member about an event or incident in your day, you engage in a form of narration. In addition, a narrative can be factual or fictional. A factual story is one that is based on, and tries to be faithful to, actual events as they unfolded in real life. A fictional story is a made-up, or imagined, story; the writer of a fictional story can create characters and events as he or she sees fit.

The big distinction between factual and fictional narratives is based on a writer’s purpose. The writers of factual stories try to recount events as they actually happened, but writers of fictional stories can depart from real people and events because the writers’ intents are not to retell a real-life event. Biographies and memoirs are examples of factual stories, whereas novels and short stories are examples of fictional stories.

Because the line between fact and fiction can often blur, it is helpful to understand what your purpose is from the beginning. Is it important that you recount history, either your own or someone else’s? Or does your interest lie in reshaping the world in your own image—either how you would like to see it or how you imagine it could be? Your answers will go a long way in shaping the stories you tell.

Ultimately, whether the story is fact or fiction, narrative writing tries to relay a series of events in an emotionally engaging way. You want your audience to be moved by your story, which could mean through laughter, sympathy, fear, anger, and so on. The more clearly you tell your story, the more emotionally engaged your audience is likely to be.

On a separate sheet of paper, start brainstorming ideas for a narrative. First, decide whether you want to write a factual or fictional story. Then, freewrite for five minutes. Be sure to use all five minutes, and keep writing the entire time. Do not stop and think about what to write.

The following are some topics to consider as you get going:

THE STRUCTURE OF A NARRATIVE ESSAY

Major narrative events are most often conveyed in chronological order, the order in which events unfold from first to last. Stories typically have a beginning, a middle, and an end, and these events are typically organized by time. Certain transitional words and phrases aid in keeping the reader oriented in the sequencing of a story. Some of these phrases are listed in Table 10.1 “Transition Words and Phrases for Expressing Time”.

The following are the other basic components of a narrative:

- Plot. The events as they unfold in sequence.

- Characters. The people who inhabit the story and move it forward. Typically, there are minor characters and main characters. The minor characters generally play supporting roles to the main character, or theprotagonist.

- Conflict. The primary problem or obstacle that unfolds in the plot that the protagonist must solve or overcome by the end of the narrative. The way in which the protagonist resolves the conflict of the plot results in the theme of the narrative.

- Theme. The ultimate message the narrative is trying to express; it can be either explicit or implicit.

WRITING AT WORK

When interviewing candidates for jobs, employers often ask about conflicts or problems a potential employee has had to overcome. They are asking for a compelling personal narrative. To prepare for this question in a job interview, write out a scenario using the narrative mode structure. This will allow you to troubleshoot rough spots, as well as better understand your own personal history. Both processes will make your story better and your self-presentation better, too.

Take your freewriting exercise from the last section and start crafting it chronologically into a rough plot summary. To read more about a summary, see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content”. Be sure to use the time transition words and phrases listed in Table 10.1 “Transition Words and Phrases for Expressing Time” to sequence the events.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your rough plot summary.

WRITING A NARRATIVE ESSAY

When writing a narrative essay, start by asking yourself if you want to write a factual or fictional story. Then freewrite about topics that are of general interest to you.

Once you have a general idea of what you will be writing about, you should sketch out the major events of the story that will compose your plot. Typically, these events will be revealed chronologically and climax at a central conflict that must be resolved by the end of the story. The use of strong details is crucial as you describe the events and characters in your narrative. You want the reader to emotionally engage with the world that you create in writing.

To create strong details, keep the human senses in mind. You want your reader to be immersed in the world that you create, so focus on details related to sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch as you describe people, places, and events in your narrative.

As always, it is important to start with a strong introduction to hook your reader into wanting to read more. Try opening the essay with an event that is interesting to introduce the story and get it going. Finally, your conclusion should help resolve the central conflict of the story and impress upon your reader the ultimate theme of the piece.

On a separate sheet of paper, add two or three paragraphs to the plot summary you started in the last section. Describe in detail the main character and the setting of the first scene. Try to use all five senses in your descriptions.

Key Takeaways

- Narration is the art of storytelling.

- Narratives can be either factual or fictional. In either case, narratives should emotionally engage the reader.

- Most narratives are composed of major events sequenced in chronological order.

- Time transition words and phrases are used to orient the reader in the sequence of a narrative.

- The four basic components to all narratives are plot, character, conflict, and theme.

- The use of sensory details is crucial to emotionally engaging the reader.

- A strong introduction is important to hook the reader. A strong conclusion should add resolution to the conflict and evoke the narrative’s theme.

Narrative Copyright © 2016 by Writing for Success is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Feedback/errata.

Comments are closed.

- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

What is Storytelling? An Ultimate Guide

This blog will explore the art of Storytelling, its significance in communication, the various purposes it serves, and the step-by-step process of Storytelling. You will discover its profound impact on our lives. In this blog, you will learn What is Storytelling, its importance, and the processes involved.

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- Creative Writing Course

- Innovative Thinking Training

- Value Based Selling Training

- Copywriting Course

- Storytelling for Marketers Training

When it comes to engaging an audience, capturing their attention, and conveying a message, nothing beats the power of Storytelling. However, Storytelling is not just about telling tales or anecdotes, it is a skill that can be learned and mastered that can transform the way you communicate, persuade, and inspire. But do you know exactly What is Storytelling, and why is it so crucial in communication?

If you are interested in learning more about it, then this blog is for you. In this blog, you will learn What is Storytelling, its importance, and the processes involved. Let’s delve in to learn more!

Table of Contents

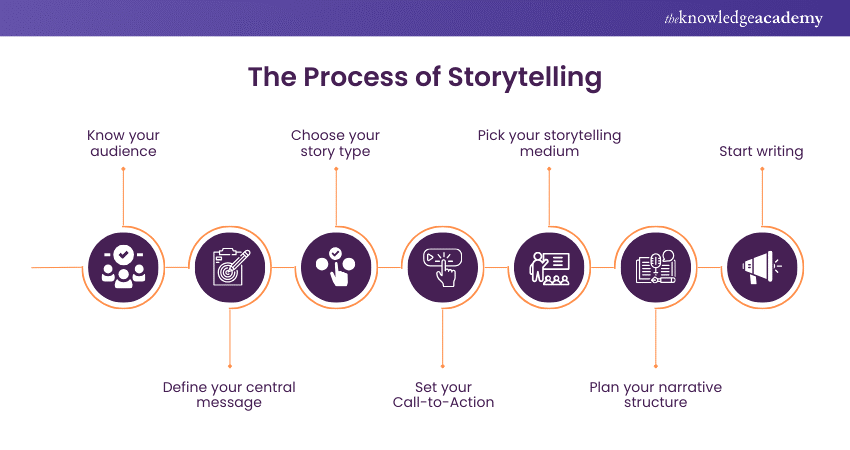

1) Understanding What is Storytelling

2) The purpose of Storytelling

3) The process of Storytelling

4) Tips for effective Storytelling

5) Conclusion

Understanding What is Storytelling

Storytelling is the art of conveying narratives through words, visuals, or experiences to engage, inform, or entertain an audience. It is a powerful and timeless practice that captures human emotions, experiences, and ideas.

Thus, it enables us to connect with others, convey messages effectively, and inspire action. Whether through spoken words, written stories, visual presentations, or immersive experiences, Storytelling plays a pivotal role in human communication and expression.

The purpose of Storytelling