Why Are Blue Whales Endangered? | History and Hunting Facts

The blue whale is not only one of the most well-known whale species, but it’s also the largest known whale in existence, growing to lengths of over 100 ft and weighing more than 150 tons, although 60 – 80 ft. is more common.

In the past (pre whaling era), blue whales were extremely abundant (150,000 – 200,000 before whaling began) and found swimming in all of the major oceans of the world. However, today, it is estimated that there are now only between 1,500 – 2,500 blue whales left in existence.

Because of their large size and supply of blubber , blue whales were a popular species to hunt. Consequently, whalers would sell their blubber and body parts to suppliers who made various materials out of it.

In the past blue whales were hunted for:

- Oil – Lamp oil, soap, perfume, candles, and cosmetics

- Food – Cooking oil, margarine, and whale meat

- Clothing – corsets and umbrellas

- and various other products, including tools such as fishing hooks.

How & why the hunting of blue whales began

During the 1,700′s whale blubber & oil became a lucrative business largely due to the growing industrial age and increasing dependency on oil combined with advances in technology and boating, which made it easier for whalers to hunt, kill & capture whales, which quickly lead to a highly competitive (international) whaling market, and thus the whaling industry was born.

As technology, boats, and hunting equipment continued to evolve throughout the centuries, the rate at which whales were being killed greatly increased and continued to shrink the existing whale populations, especially those of the blue whale species. And because blue whales are large, whalers got paid top dollar for these mammals, so competitors continually hunted them until near extinction.

As whale populations declined significantly, organizations such as The International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling begin stepping in to limit the killing of endangered species and hopefully allow those species time to recover and repopulate.

In addition to the assistance, these organizations provided towards the monitoring and regulation of whale hunting, increases in technology and cheap alternative resources provided companies & suppliers with alternative methods of producing & selling their products without the need to use whale oil as a source of fuel or as an ingredient in their materials.

Although whales were being killed since the B.C. era, it is believed that whale hunting hadn’t caused much ecological impact due to limited technology and most killings remained limited to the coastline and near offshore waters.

During the pre whaling era, the demand for whales was also much lower as their oil was not considered vital due to a lack of technological advances and little need for it regarding pre-16th-century industrial equipment.

The International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling

In 1931 international agreements were made between various countries to minimize whale killings to help several species recover due to whales’ endangered status, which was caused largely by the whaling industry.

The International Whaling Commission was created to monitor the whaling industry and limit their hunting efforts.

In 1986 the International Whaling Commission adopted a moratorium to prevent all whaling activities in the countries that signed into the agreement and established stronger legal actions among those caught participating in whaling activities.

Unfortunately, even though agreements exist between various countries, those that did not opt into the agreement are only bound by their country’s own regulations on whaling (if the country has imposed regulations), which means that there are still countries today that consider whaling a source of industry.

Today, however, countries and companies that still hunt whales primarily hunt them as a source of food (in some areas, whale meat is considered a delicacy) because other practical uses such as lamp oil, cosmetics, and candles no longer require the parts/oil of whales to be produced.

Related posts:

- Marine Mammal Conservation

- What Is A Group Of Whales Called?

- Andrew’s Beaked Whale Facts | Diet, Migration and Reproduction

- Gray’s Beaked Whale Facts | Diet, Migration and Reproduction

How we can protect our last remaining blue whales, the world’s largest-ever animal

pause video

The endangered blue whale is the largest animal to have ever lived on Earth — let alone California.

At up to 400,000 pounds (the weight of 33 elephants!) and as long as 90 feet, they migrate up the California coast from May to October alongside several other species, including humpbacks and gray whales, favorites of whale watchers. But unlike those two species, the blue whale has never come close to recovering from the devastation of 20th century commercial whaling, banned internationally in 1986.

Even the biggest animals need help in our changing oceans. As many as 80 endangered whales — among them blue whales, fin whales, and some populations of humpbacks — wash up on California shores each year, often after fatal encounters with container ships. Ship strikes are a top source of whale mortality, killing thousands of whales globally each year. It’s a worsening problem that has even prompted federal investigation by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Every whale loss matters, not just for biodiversity and the loss of cherished individuals — some of whom are bona fide celebrities — but because we run the risk of losing some of these magnificent species forever.

UC Santa Barbara marine biologist Douglas McCauley has good news.

“This is a solvable problem,” he says.

He and his team have developed a solution for alerting ships to the presence of whales so they can slow down and take precautions. Even better: Two years of data suggest it’s working.

With fewer than 15,000 blue whales worldwide, and just 2,000 off the California coast, we can, and must, save the whales.

Falling for the oceans

McCauley grew up in Los Angeles, maybe not the most obvious place to discover a passion for ecology. The sidewalks and built environment of LA were not a natural showcase, but the yawning blue space on the map beckoned.

“For the price of a $15 entry ticket, which was your mask, you could dive underwater in a kelp forest, look up and see the skyline of LA, the zooming cars, then look down and share space with giant sea bass and migrating whales,” he says. “Wildness was waiting for me as a teacher, my earliest lab.”

Douglas McCauley

Working on fishing boats going in and out of the Port of Los Angeles in the summer helped him pay his way for a degree at UC Berkeley. Many of the people he grew up with had family working in the port as longshoremen or worked there themselves. The importance of the towering shipping industry to local families and communities was unmissable, as was its vital role in the overall economy.

“Some people estimate that 80 to 90 percent of the goods that we interact with on a daily basis have actually traveled on a ship across an ocean somewhere,” McCauley notes.

Thousands of container ships and tankers ply our waters each year, a $9 billion industry that continues to grow. The danger to whales has grown with it, even as scientists continue to uncover profound insights about whale intelligence and communication, and the vital role these mammals play in the health of ocean ecosystems.

The songs that changed the world

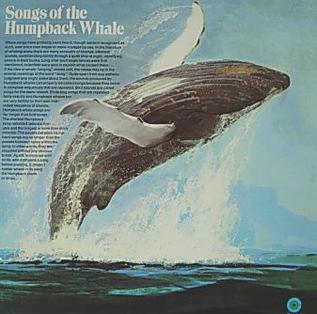

In the 1960s, when commercial whaling was taking as many as 50,000 whales a year, long after the usefulness of their blubber as a natural resource had expired, scientist Roger Payne was listening to something. Naval equipment called hydrophones monitored the seas, hoping to detect stealthy enemy submarines. But they were also detecting strange underwater sounds that they couldn’t identify. Payne was the first to realize the noises chalked up to mechanical objects were actually whale vocalizations, and more than that, songs they used to communicate. In 1970, he introduced the world to these songs through his best-selling LP “Songs of the Humpback Whale.”

Payne’s scientific discovery helped launch advocacy against commercial whaling and the ubiquitous 1970s campaign to “save the whales.” And it worked — commercial whaling was banned internationally in 1986.

Since that time, and because some whales have been able to recover somewhat, we’ve made even more discoveries. Whales don’t just sing — they have unique dialects that vary within species and pods. Some scientists, among them UC Berkeley faculty, are even trying to understand their language, and possibly “speak” it, as part of an international effort involving endangered sperm whales . We’ve learned that whales grieve, will protect other animals from predation, and may even hold secrets to aging and resilience against cancer . Science’s growing recognition of their complexity reflects the appreciation many Indigenous communities have had for whales going back millennia.

The big elephant in the room — or blue whale, if you will — is that we’ve also just begun to learn how important they are in combating climate change: A single whale sequesters about as much carbon as 1,375 trees when it is able to die naturally and sink to the ocean floor (a lengthy process known as “ whale fall ”). Even whale poop has value, stimulating the production of phytoplankton, which captures 40 percent of all CO2 on Earth. Today, whale populations as a whole are at just a quarter of their pre-whaling numbers — yet they could be a powerful tool against global warming.

But for all their tremendous size, complexity and impact, even the biggest whales are no match for global shipping.

Everyone’s best interest

While a blue whale at nearly 100 feet is the biggest animal ever recorded on the planet, container ships are at least 13 times their size. Traveling at high speeds, container ships also produce a ton of noise, overwhelming whales’ ability to communicate as they pass through. Picture trying to have a conversation in a crowded bar, McCauley says. Then imagine that midway through the conversation, you suddenly have to come up for breath — that’s when whale strikes happen.

The front of a ship is actually quieter than the rest of it, so when whales head up for oxygen and relief, that’s when they get hit. The strikes don’t hurt the ships, but they pulverize the largest animals on Earth.

“Nobody wins when they come into the harbor with a beloved species wrapped around the bow,” McCauley says. “It’s in everyone’s best interest to avoid this. One of the recommendations from industry was, just tell us when they’re there.”

“We can’t teach whales to avoid ships,” McCauley says. “But we can change shipping.”

A “school zone” for whales

Research has shown the danger to whales is much lower when ships proceed at speeds of 10 knots or less. Unfortunately, as whales migrate in search of a krill buffet, they share their habitat with container ships navigating shipping lanes. There are speed limits, but on the West Coast, compliance is voluntary — and a 2019 study found that less than half of ships comply.

Voluntarily slowing down while your competitors keep trucking is a precarious scenario in the global economy. So McCauley and his team, including colleagues at UC San Diego and UC Santa Cruz, developed a way of producing real-time information on the presence of whales so ships will voluntarily slow down. McCauley compares the tool, known as “Whale Safe,” to the traffic rules that reduce speeds when kids are getting out of school.

Whale Safe works by synthesizing a few data sources into one assessment. Far beneath the surface, a hydrophone — that naval instrument through which Roger Payne revolutionized whale science by analyzing their calls for the first time — listens for whale calls in the nearby area, which are identified by a computer as blue, fin or humpback (the first two species are particularly endangered). Naturalists on whale watching ships also provide data of real-time whale sightings at the surface and transmit that back to scientists at Whale Safe. Data on whale migration patterns is then incorporated through artificial intelligence to analyze the likelihood that whales are in a given area at any time.

It all comes together to form a “whale presence” rating that shipping companies can follow as their vessels pass through the Santa Barbara Channel and the San Francisco Bay Area, the state’s major shipping hotspots.

Whale Presence Rating: HIGH Acoustic Detections: Humpback, Blue, Humpback. Sightings: 0 Blue, 13 Humpback, 0 Fin. https://t.co/qrI7CWx3ud pic.twitter.com/Azl9xKrQdv — Whale Safe – Southern California (@whalesafe_sc) October 6, 2022

Right now, compliance with these slow down programs is voluntary, so while many shipping companies do comply — and many genuinely want to help — they aren’t legally bound to do so. But the ratings and compliance are also made available to the public in real-time by Whale Safe, creating an environment where pressure and accountability can be applied to companies that don’t change.

It’s just a start on an international problem, but there are encouraging signs that it works. From 2018 up til the launch of Whale Safe on September 17, 2020, Southern California recorded 10 ship strikes, 6 of those fatal. But in the 2 years that Whale Safe has been in place in the Santa Barbara Channel, McCauley says no ship strikes have been recorded at all.

The system is now being tested in the San Francisco Bay , with the goal of showing that the system and its equipment can overcome the challenges of different marine environments.

“Elon Musk says things are hard in space,” McCauley chuckles. “I don’t begrudge our space community, but sharks biting your tools is hard, too.”

McCauley envisions the system evolving into something similar to Dolphin Safe tuna, with brands advertising that they use the tool to safeguard whales, and consumers rewarding that practice with increased sales.

Keeping whales safe from shipping strikes is an important way of helping their populations rebound, which could also help us fight climate change.

And there are other steps we can take to protect these animals. UC San Diego’s Scripps Whale Acoustics Lab , an important partner on Whale Safe, is working on reducing ship noise and rethinking ship design. Private donors are helping this important work expand. The Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory that McCauley directs, based in UC Santa Barbara, is part of a $60 million gift from Marc and Lynne Benioff to safeguard ocean health through science and technology. Whale Safe is one tangible result of that investment.

Climate change is the other major threat to whales, and one that looms even larger than ship strikes, McCauley says. Whales are adaptable, but to continue their population growth and vital role on the planet, they’ll need some human help. Fortunately, there are thousands of students who — just like McCauley — are passionate about protecting and preserving not only the world’s largest animal, but the entire ecosystem that it helps power.

“There's a lot of environmental trauma out there,” McCauley says, “but I find in my classrooms hundreds of students that are looking to engineer a better future and figuring it out with their hearts and with their minds. And these brilliant students will be the architects of some pretty brilliant innovations.

They’re gonna blow what we’re doing with Whale Safe out of the water.”

To learn more about UC Santa Barbara’s efforts with partners at UC Santa Cruz, UC San Diego, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Oregon State University, University of Washington, NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center, Conserve IO, The Marine Mammal Center, Point Blue Conservation Science, and Cascadia Research Collective to track whale and shipping activity to provide the best available science to reduce the risk of whale-ship collisions, visit the Whale Safe website .

You too can listen to the songs of the humpback whale on Bandcamp .

Keep reading

One in four MacArthur ‘geniuses’ this year has UC bona fides

UC-affiliated experts are a perennial presence on the esteemed annual list of MacArthur Fellows.

UC Davis vets to the rescue for animals in wildfires

A UC Davis-administered program featuring mobile clinics is ready to deploy to care for animals affected by disasters statewide.

Study Like a Boss

The Blue whale

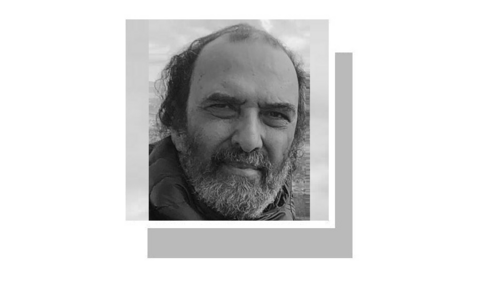

The Blue whale is the largest creature of the sea, in fact, it is the largest creature known to man. Contrary to what most people think, even though Blue whales live in the sea, they are mammals. They breathe air, have their babies born alive and can live anywhere from 30 to 70 years. The Blue whale is a baleen whale, and instead of having teeth, Blue whales have around 300-400 baleen plates in their mouths. They fall under the category of the rorquals, which are the largest of the baleen family. The scientific name of the Blue whale is, Balsenoptera musculus.

Key Words: Balaenoptera musculus, Suborder Mysticeti, balaenoptera intermedia, balaenoptera brevicauds, baleen whale, rorqual, calf, sulfur bottom, Sibbalds Rorqual, Great Northern Rorqual, gulpers, blowholes, blubber, oil, keratin, krill, copepods, plankton, orcas, endangered Introduction Whales are separated into two groups, the baleen and the toothed whales. The blue whale is the largest baleen whale and the largest animal that ever lived on Earth, including the largest dinosaurs. Baleen are rows of coarse, bristle-like fibers used to strain plankton from the water. Baleen is made of keratin, the same material as our fingernails.

They live in pods, the have two blowholes. The blue whale has a 2-14 inch (5-30cm) thick layer of blubber. Blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) are baleen whales (Suborder Mysticeti). They are one of 76 species and are marine mammals . Background The Blue whale is called a rorqual, a Norwegian word for furrow referring to the pleated grooves running from its chin to its naval. The pleated throat grooves allow the Blue whales throat to expand during the huge intake of water during filter feeding; they can old 1,000 tons or more of food and water when fully expanded (Small 1971).

Blue whales have 50-70 throat grooves. Blue whales grow up to about 80 feet (25m) long on average, weighing about 120 tons. The females are generally larger than the males, this is the case for all baleen whales. The largest specimen found was a female 94 feet (29m) long weighing more than 174 tons (Satchell 1998). The head of the Blue whale forms up to a quarter of the total body length. Compared with other rorquals, the head is very broad. The blue whale heart is the size of a small car and can pump almost 10 tons of blood throughout he body.

They have a very small, falcate (sickle-shaped) dorsal fin that is located near the fluke, or tail. Blue whales have long, thin flippers 8 feet (2. 4m) long and flukes that are 25feet (7. 6m) wide. The blue whales skin is usually blue-gray with white-gray spots. The underbelly has brown, yellow, or gray specks. During the winter, in cold waters, diatoms stick to the underbelly, giving it a yellow to silver- to sulfur-colored sheen; giving the blue whale its nick-name of sulfur bottoms. Other names include Sibbalds Rorqual and Great Northern Rorqual.

Blue whales (like all baleen whales) are seasonal feeders and carnivores that filter feed tiny crustaceans (krill, copepods, etc), plankton, and small fish from the water. Krill, or shrimp-like euphasiids are no longer than 3 inches. It is amazing that the worlds largest animals feed on the smallest marine life . Blue whales are gulpers, filter feeders that alternatively swim then gulp a mouthful of plankton or fish. An average-sized blue whale will eat 2,000-9,000 pounds (900-4100kg) of plankton each day during the summer feeding season in cold, arctic waters (120 days) (Hasley 1984).

The blue whale has twin blowholes with exceptionally large fleshy splashguards to the front and sides. It has about 320 pairs of black baleen plates with dark gray bristles in the blue whales jaws. These plates can be 35-39 inches (90cm-1m) long, 21 inches (53cm) wide, and weigh 200 pounds (90kg). This is the largest of all the rorquals, but not the largest of all the whales. The tongue weighs 4 tons. Blue whales live individually or in very small pods (groups). They frequently swim in pairs. When the whale comes to the surface of the water, he takes a large breath of air.

Then he dives back into the water, going to a depth of 350 feet (105m). Diving is also the way in which whales catch most of their food. Whales can stay under water for up to two hours without coming to the surface for more air. Blue whales breath air at the surface of the water through 2 blowholes located near the top of the head. They breathe about 1-4 times per minute at rest, and 5-12 times per minute after a deep dive (Hasley 1984). Their blow is a single stream that rises 40-50 feet (12-15m) above the surface of the water.

Blue whales are very fast swimmers; they normally swim -20 mph, but can go up to 24-30mph in bursts when in danger. Feeding speeds are slower, usually about 1-4mph. Blue whales emit very loud, highly structured, repetitive low-frequency sounds that can travel form many miles underwater. They are probably the loudest animals alive, louder than a jet engine. These songs may be used for locating large masses of krill (tiny crustaceans taht they eat) and for communicating with other blue whales. Blue whales typically are found in the open ocean and live at the surface.

They are found in all the oceans of the world. The majority of Blue whales live in the Southern Hemisphere. The subspecies found in the Southern Hemisphere are the balaenoptera musculus. The smaller populations inhabit the North Atlantic and North Pacific. These Northern Hemisphere Blue whales are the balaenoptera brevicauda. They migrate long distances between low latitude winter mating grounds and high latitude summer feeding grounds. They are often seen in parts of California, Gulf of California (Sea of Cortez), Gulf of St. Lawrence, Canada and the northern Indian Ocean .

Blue whale breeding occurs mostly in the winter to early spring while near the surface and in warm waters. The gestation period is about 11-12 months and the calf is born tail first (this is normal for cetaceans) and near the surface in warm, shallow waters (Hasley 1984). The newborn instinctively swims to the surface within 10 seconds for its first breath; it is helped by its mother, using her flippers. Within 30 minutes of its birth the baby whale can swim. The newborn calf is about 25 feet (7. 6m) long and weighs 6-8 tons. Twins are extremely rare (about 1% of births); there is almost always one calf.

The baby is nurtured with its mothers fat-laden milk (it is about 40-50% fat) and is eaned in about 7-8 months. A calf may drink 50 gallons of mothers milk and gain up to 9 pounds an hour or 200 pounds a day. The mother and calf may stay together for a year or longer, when the calf is about 45 feet (13m) long. Blue whales reach maturity at 10-15 years. Blue whales have a life expectancy of 35-40 years. However, there are many factors that limit the life span of the Blue whale. Packs of killer whales (orcas) have been known to attack and kill young blue whales or calves. Man also hunted blue whales until the International

Whaling Commission declared them to be a protected species in 1966 because of a huge decrease in their population. The Blue whale was too swift and powerful for the 19th century whalers to hunt, but with the arrival of harpoon canons, they became a much sought after species for their large amounts of blubber. They were also hunted years ago for their baleen, which was used to make brushes and corsets. But it was their size and high yield of oil that made them the target of choice for modern commercial whalers. Before mans intervention there were 228,000 Blue whales swimming the oceans of the world.

Between 1904 and 1978, whalers scoured the seas for this huge cetacean, most were taken in the Southern Hemisphere, many illegally (Satchell 1998). As the population figure suggests, it was relentlessly slaughtered for every reason imaginable, almost to the point of extinction. Another reason why Blue whales are almost extinct is pollution. Mosst of their illnesses are contracted by pollution. It is estimated that there are about 10,000-14,000 blue whales world-wide. Blue whales are an endangered species. They have been protected worldwide by international law, since 1967.

The blue whale was listed as endangered throughout its range on June 2, 1970 under Section 7 of the Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1969. They are not to be hunted by anyone for any reason at all. Suggestions are that some populations may never recover. Conclusion Although Blue whales are now protected, we still must not hunt or kill them in their delicate balance of life. Some people believe that whales and dolphins are animal of mystery and beauty, and that a dead whale is an omen, good or bad. Most people say that all humans must protect all whales. We need to save these great water giants.

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Related posts:

- Killer Whales Essay

- History Of Whaling

- Endangered Species

- Essay about Personal Narrative: My Trip To Blue John Canyon

- The Surprising Moby-Dick

- Summary of The Whale and the Reactor by Langdon Winner

- Moby Dick, or The Whale: Book Report

- The Blue Roses

- The ABC’s of Black and Blue

- Blue Collar Workers Essay

- The Devil In A Blue Dress Essay

- A Yellow Raft in Blue Water

- David Lynch’s Blue Velvet

- Blue Catfish Invasive Species Essay

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

WATCH: Blue Whales 101

A blue whale's tongue alone can weigh as much as an elephant—its heart as much as an automobile.

What is the blue whale?

Blue whales are the largest animals ever known to have lived on Earth . These magnificent marine mammals rule the oceans at up to 100 feet long and upwards of 200 tons . Their tongues alone can weigh as much as an elephant. Their hearts, as much as an automobile.

Diet of krill

Blue whales reach these mind-boggling dimensions on a diet composed nearly exclusively of tiny shrimplike animals called krill. During certain times of the year, a single adult blue whale consumes about 4 tons of krill a day.

Blue whales are baleen whales, which means they have fringed plates of fingernail-like material, called baleen, attached to their upper jaws . The giant animals feed by first gulping an enormous mouthful of water, expanding the pleated skin on their throat and belly to take it in. Then the whale's massive tongue forces the water out through the thin, overlapping baleen plates. Thousands of krill are left behind—and then swallowed.

Coloring and appearance

Blue whales look true blue underwater , but on the surface their coloring is more a mottled blue-gray. Their underbellies take on a yellowish hue from the millions of microorganisms that take up residence in their skin. The blue whale has a broad, flat head and a long, tapered body that ends in wide, triangular flukes.

Vocalization and behavior

Blue whales live in all the world's oceans , except the Arctic, occasionally swimming in small groups but usually alone or in pairs. They often spend summers feeding in polar waters and undertake lengthy migrations towards the Equator as winter arrives.

These graceful swimmers cruise the ocean at more than five miles an hour , but accelerate to more than 20 miles an hour when they are agitated. Blue whales are among the loudest animals on the planet . They emit a series of pulses, groans, and moans, and it’s thought that, in good conditions, blue whales can hear each other up to 1,000 miles away . Scientists think they use these vocalizations not only to communicate, but, along with their excellent hearing, to sonar-navigate the lightless ocean depths.

Blue whale calves

Calves enter the world already ranking among the planet's largest creatures. After about a year inside its mother's womb, a baby blue whale emerges weighing up to 3 tons and stretching to 25 feet. It gorges on nothing but mother's milk and gains about 200 pounds every day for its first year .

Blue whales are among Earth's longest-lived animals . Scientists have discovered that by counting the layers of a deceased whale's waxlike earplugs, they can get a close estimate of the animal's age. The oldest blue whale found using this method was determined to be around 110 years old. Average lifespan is estimated at around 80 to 90 years.

Conservation

Aggressive hunting in the 1900s by whalers seeking whale oil drove them to the brink of extinction. Between 1900 and the mid-1960s, some 360,000 blue whales were slaughtered . They finally came under protection with the 1966 International Whaling Commission , but they've managed only a minor recovery since then.

Blue whales have few predators but are known to fall victim to attacks by sharks and killer whales, and many are injured or die each year from impacts with large ships.

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Find anything you save across the site in your account

What Have We Done to the Whale?

By Amia Srinivasan

Last November, drone footage was posted on Instagram of a gray whale swimming near the surface just off the coast of Dana Point, California. In the video, the whale, a juvenile maybe twenty-five feet long, cruises slowly into a lineup of surfers, its undulating tail casting arcing ripples, and then emerges from the water, exhaling through its blowhole. A few surfers paddle off in alarm, though most seem oblivious. The whale dips below the surface again, a ghostly silhouette, and glides out beyond the surfers, away.

I had been surfing in that spot just a few weeks before. Had I been in the water that day, and suddenly seen the whale’s body beneath me, gargantuan and silent, I would have, for a moment, gone cold with dread. How could I not? To be close to a whale, in the wild, not in a boat but in the water itself, is to encounter an embodied agency that exists, across every dimension, on a scale that swallows our own: its physical size, its evolutionary age, its polar voyages. The fear evoked by the whale is not a judgment on its character. Whales almost never harm humans, and when they do it is invariably the humans’ fault. And yet: what am I to a whale? After the whale passed, terror would have melted into an abiding thrill: of having met life in its largest, ancient form. Of having been blessed, in the most pagan sense of that term. In drawing close to those surfers, the whale drew them closer to its own alien dominion, offering the watery communion for which every surfer quietly longs: to be absorbed, returned, dissolved into the sea.

‘‘Would we know it, the moment when it became too late; when the oceans ceased to be infinite?” Rebecca Giggs asks in her masterly “ Fathoms: The World in the Whale ” (Simon & Schuster). She means the moment when the oceans become so disfigured by human activity that, seeing them, we will see only ourselves. Her answer is that this moment is already here, and most of us are missing it. For Giggs, the whale is a potent but misleading symbol of the ocean’s infinity, its alterity and expansiveness. We tend to think of the whale as a story of human redemption: a creature almost hunted out of existence by the commercial whaling industry in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and then saved by our collective recognition that, as activists told the United Nations in 1972, whales are “the common heritage of mankind.” Since 1986, when the International Whaling Commission began enforcing a global moratorium on commercial whale hunting, many whale populations, once near extinction, have rebounded. The laying down of harpoons and the return of the whale appear to speak not just to our empathy for creatures that, like us, care for their young, create culture, and sing songs but also to the part of our humanity that respects what lies beyond it. In truth, Giggs argues, our mass consumption and globalized supply chains, our carbon emissions and throwaway plastics threaten to bring us a sea that is “not full of mystery, not inexplicable in its depths, but peppered with the uncannily familiar detritus of human life.” In 2017, a beaked whale washed up onshore near Bergen, Norway. In its stomach were some thirty pieces of plastic trash, including Ukrainian chicken packaging, a Danish ice-cream wrapper, and a British potato-chip bag. This is the “world in the whale” of Giggs’s title: not an alien dominion but the totalized reality of human domination.

The size of whales has made them, for most of human history, extremely difficult to kill. Adult grays can grow up to fifty feet long and weigh forty tons. Blue whales, the largest creatures ever to have lived, can grow almost a hundred feet long and weigh a hundred and ninety tons. When whales exhale through their blowholes, the vapor is so dense that it produces rainbows. The earliest evidence of whale hunting is perhaps as old as eight thousand years, in South Korea, where Neolithic-era shale carvings depict marine animals being hunted with lances and makeshift floats. Traditional whale hunters typically had to harass their prey to death over many days and nights. They used bludgeons and spears, sometimes tipped with poison, to serially wound and exhaust the animals, while floats were used to prevent them from diving—“sounding”—out of reach. The Inuit created their floats by inflating gutted seals, their orifices stitched shut. All the indigenous cultures that hunted whales for subsistence—on the coasts of the Korean Peninsula, the Pacific Northwest, Alaska, Zanzibar, Siberia, Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Norway—did so at their peril, and with elaborate ritual and frugality, using the whale’s many parts for food, shelter, and amulets.

Then, in the sixteenth century, Basque whalers created a global whale trade. This was made possible by a technological advance: the attaching of a two-flued iron harpoon to a braided rope that could be uncoiled at great speed off a boat’s deck. Although the harpoon was unable to pierce through to a whale’s vital organs, it was, with its flared barbs, almost impossible to dislodge from the animal’s blubber. Thus tethered to the boat, the whale could not escape the hunters’ lances.

Soon Basque whalers depleted shoreline populations in the Bay of Biscay. Bigger ships, in turn, allowed the whalers to hunt in the open seas—what’s known as “pelagic whaling”—and to pursue various species at different points in their migration routes. Near Newfoundland, Basque whalers killed as many as forty thousand whales between 1530 and 1610, becoming, for a time, the world’s dominant whaling force. Their preferred method was to harpoon calves first, followed by the mothers that rushed to their rescue.

Whale hunting became a year-round business. The Dutch, the Danes, and the British joined in; by the late eighteenth century, commercial whaling had spread to South Africa and New Zealand. American colonists pioneered the onboard rendering of oil from whale blubber. In this process, a whale carcass was chained to the side of the ship, and rotated with pulleys as sickle-shaped blades peeled it like an orange; the blubber was then separated from flesh and skin, and liquefied in huge cast-iron cauldrons, underlaid with water to avoid setting fire to the ship. By turning their vessels into mobile slaughterhouses, American whalers were able to hunt whales that were then abundant in equatorial waters, whose carcasses would have otherwise rotted by the time the ships returned home. The whalers also came to use shoulder guns and bomb lances, increasing the possible distance between hunter and prey. By the mid-nineteenth century, pelagic whaling was the fifth-largest industry in the United States.

Why whales? Like traditional whale hunters, early commercial whalers sought out whales largely for their flesh, a food approved by the Vatican for meatless Fridays. By the nineteenth century, though, whales had become prized as a source of a much more valuable commodity: oil. In 1854, whale oil, extracted from blubber, traded at, in today’s terms, eighteen dollars a gallon. A single mature right whale could yield seven thousand gallons. Whale oil greased factory cogs, lit shop floors and streets, and, deployed as an insecticide, spurred industrial agriculture. Sperm whales were hunted for the waxlike spermaceti found in their heads, which was used as a lubricant in looms, trains, and guns, and, most significant, as a raw material in fine candles. New Bedford, Massachusetts, the center of sperm-whale hunting, was called “the city that lit the world.” Baleens, the bristly combs that certain whales, including humpbacks, have in place of teeth, were used in corsets, parasols, hairbrushes, fishing rods, shoehorns, eyeglass frames, hat rims, sofa stuffing, police nightsticks, and the thin canes used to beat misbehaving schoolchildren, which may explain the phrase “to whale on.” Increasingly, whales were seen not as prey but as a natural resource to be mined; whalers talked about migrating sperm whales as veins running through the ocean, like gold.

An estimated two hundred and thirty thousand sperm whales were killed in the nineteenth century. In the twentieth, that number grew to more than seven hundred thousand. In total, nearly three million whales of all species were killed in that century. (Human hunting has reduced the world’s great-whale biomass by as much as eighty per cent.) Early-twentieth-century whaling was a truly international concern, run by conglomerates of Norwegian, British, Dutch, German, Japanese, Australian, and American fleets and capital. That whaling became more aggressive is a departure from the trajectory one might have expected: the previous century’s whaling had depleted whale populations, and abundant substitutes for whale oil—cheaper vegetable oils and petroleum products—had been found. But nautical technology advanced; coal-powered and then diesel-powered ships allowed whalers to hunt species that had previously been too quick—blue, fin, sei, minke. Ships were also equipped with mechanized weapons that could detonate or electrocute, and with improved tools for processing whale carcasses, including hydraulic tail grabbers, pressure cookers, and refrigerators. These ships were noisy machines, but radar and spotter planes, perfected in wartime, allowed them to home in on whales, called “the listening prey.” At the same time, new commercial uses were found for whale oil: in explosive munitions, a trench-foot treatment, soap, margarine, lipstick, burn gel. General Motors used spermaceti in its transmission fluid until 1973. During the Cold War, the substance was used in intercontinental missiles and submarines. Whaling had become a matter of military interest.

The International Whaling Commission (I.W.C.) was set up, in 1946, to regulate whale hunting in international waters. But the quotas that the commission initially imposed backfired, sparking a mad rush by whalers who were keen to stockpile whale oil, anticipating a scarcity-driven price surge. Commercial fleets raced to take all the whales they could get, harpooning animals and then abandoning them when fattier specimens were spotted. Whalers hunted out of season and in whale sanctuaries, and illegally targeted whale calves. Aristotle Onassis’s lucrative whaling enterprise ended when his own sailors testified, in the Norwegian Whaling Gazette, to practices on his factory ships: “Shreds of fresh meat from the 124 whales we killed yesterday are still lying on the deck. Scarcely one of them was full grown. Unaffected and in cold blood, everything is killed that comes before the gun.”

The commercial whalers of the postwar period hunted Southern Hemisphere whales to near “commercial extinction,” the point at which the cost of killing an animal is no longer worth the returns. American and European whaling operations shrank, but the cause was taken up by two countries driven by nationalist rather than by commercial prerogatives. The U.S.S.R.’s whaling industry, which had begun in the nineteen-thirties, expanded during the Cold War. The Soviet military needed spermaceti, because Western embargoes cut off its access to synthetic substitutes. More than that, the Soviet state felt that it had not taken its “share” of the world’s whales, and set quotas for its whaling industry that far exceeded domestic demand for whale meat and oil. Soviet ships, frantic to keep up with state mandates that specified the total raw mass of animals to be killed, would often bring back carcasses too decayed for human consumption, or would simply throw them overboard, unprocessed. Between 1959 and 1961, Soviet ships harvested nearly twenty-five thousand humpback whales in the Antarctic.

Link copied

Japan, meanwhile, was suffering from a postwar food crisis that lasted into the nineteen-sixties, triggered by the destruction of supply chains and agricultural land. On the advice of the U.S. overseer, General Douglas MacArthur, the country turned to whaling. Whale meat was served as a cheap source of protein to elementary- and middle-school children, and became a symbol of national resilience. Though whale is eaten in very small amounts today—just one and a half ounces per person a year—whaling is still heavily subsidized by the state, with most of its output stored, uneaten. In 2019, a researcher at Rikkyo University estimated the Japanese stockpile of whale meat at thirty-seven hundred tons. After the I.W.C. imposed its global moratorium on whaling, Japan was undeterred. Until 2019, when the country withdrew from the I.W.C., Japan openly exploited a loophole that allows whales to be killed for research purposes, and any leftover whale meat to be sold as food. Between 2005 and 2014, around thirty-six hundred minke whales were killed by Japanese whalers in the Southern Ocean, resulting in just two peer-reviewed scientific papers.

The I.W.C.’s moratorium, perhaps the greatest triumph of the postwar conservationist movement, was spurred by decades of dire news. In 1964, an independent committee of biologists had warned that Southern Hemisphere whale populations faced “a distinct risk of complete extinction.” The scientists reported that there were fewer than two thousand Antarctic blue whales left. A decade later, that number was three hundred and sixty, representing a population decline of 99.85 per cent since 1905. This is the sort of mass destruction that biologists refer to as a “bottleneck” event, a decisive shrinking of a species’ gene pool that may well be irreversible. Once anti-whaling advocates helped bring non-whaling (including many landlocked) nations into the I.W.C., the group’s scientists were able to take a more explicitly conservationist stance. They were also buoyed by a worldwide outcry against whale killing. Greenpeace, employing a strategy that one of its leaders called “more an imagology than an ideology,” used footage of its theatrical high-seas tactics to evoke public sympathy and outrage. A fifteen-thousand-person anti-whaling rally was staged in London, and photographs of it were broadcast around the world. Popular books were written that celebrated whales and mourned their death; Farley Mowat’s “ A Whale for the Killing ,” from 1972, called whaling a “modern Moloch.” Whale songs—first recorded by accident in the nineteen-fifties by U.S. naval engineers sweeping for Soviet submarines—became, in the nineteen-seventies, a big commercial success. The 1970 album “Songs of the Humpback Whale” went multi-platinum. It provided a natural soundtrack for the decade’s faddish embrace of Eastern spirituality, promising an auditory portal to higher spiritual planes, repressed memories, and past lives. And it was taken as proof of the animals’ intelligence and sensitivity. Animal protectionists, appearing before Congress during a 1971 hearing on whale conservation, played the record as part of their testimony. One of them said, “Having heard their songs, I believe you can imagine what their screams would be.”

This mass gestalt shift, from whales as an extractive resource to whales as symbols of a global inheritance, is striking in part because whales are not typical of what conservationists call “charismatic” animals. Animals that win human sympathy tend to be readily anthropomorphized (elephants, chimps, dolphins), or cute (baby tigers, pangolins), or—the holy grail of animal conservation—both (otters). Whales, by contrast, are too large to be taken in easily by the human eye, let alone imaginatively given human form. They are magnificent but hardly cute. Philip Hoare, in “ Leviathan or, The Whale ” (2008), notes that the “blue marble”—the photograph of Earth captured by the astronauts aboard Apollo 17, in 1972—became famous before the first photograph of a free-swimming whale did. “We knew what the world looked like before we knew what the whale looked like,” he writes. Human uncertainty about the whale is reflected in the stories we have long told about the animal. Ancient cartographers used drolleries—hybrid monsters, part whale, part sea serpent—to indicate the limits of their knowledge. In the thirteenth century, Norse sailors said that whales fed on rain and darkness. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when taxonomists began classifying animals according to their internal structures as opposed to their outward appearance, they were stunned to discover the signs of whales’ evolutionary history as land-dwelling mammals: fin bones, a physician wrote in 1820, that resembled “a man’s hand . . . enwrapped in a mitten.”

And there is still much we do not understand about whales. They navigate tremendous distances—some humpbacks swim more than sixteen thousand miles each year, three-fifths the circumference of the earth—aided by unknown sensory apparatuses, and according to migratory routes that are passed, somehow, from parent to child. Scientists know that whale vocalization—the singing of humpbacks, the chattering of belugas, the powerful clicks of sperm whales (at up to two hundred and thirty-six decibels, the loudest animal noise on the planet)—performs an important communicative function. Whales converse, and perhaps commune, at great distances. Songs of humpbacks off Puerto Rico are heard by whales near Newfoundland, two thousand miles away; the songs can “go viral” across the world. Some scientists believe that certain whale languages equal our own in their expressive complexity; the brains of sperm whales are six times larger than ours, and are endowed with more spindle neurons, cells associated with both empathy and speech. Yet no one knows what whales are saying to one another, or what they might be trying to say to us. Noc, a beluga that lived for twenty-two years in captivity as part of a U.S. Navy program, learned to mimic human language so well that one diver mistook Noc’s voice for a colleague’s, and obeyed the whale’s command to get out of the water. A recording of Noc’s voice can be heard online today: nasal and submerged, but also distinctively like English. ( Oooow aaare you-ou-ou-ooooo ?) At the very least, it’s a better impression of a human’s voice than a human could do of a whale’s.

The whale’s aura lies in its unique synthesis of ineffability and mammality. Whales are enormous and strange. But—in their tight familial bonds, their cultural forms, their incessant chatter—they are also like us. Contained in their mystery is the possibility that they are even more like us than we know: that their inner lives are as sophisticated as our own, perhaps even more so. Indeed, contained in whales is the possibility that the creatures are like humans, only much better: brilliant, gentle, depthful gods of the sea.

The I.W.C. moratorium on commercial whale hunting has some important exceptions. It grants special whale-hunting rights to indigenous communities, including the native peoples of Alaska and of Russia’s Chukotka Peninsula, the Greenlanders, and the residents of the island of Bequia, in St. Vincent and the Grenadines. It also excludes species classified as “small cetaceans,” such as the long-finned pilot whale, a species of dolphin hunted off the Faroe Islands, an autonomous Danish territory about two hundred miles north of Scotland. (The Faroe Islands, unlike Denmark, are not part of the European Union, which prohibits the hunting of whales and dolphins.) The grindadráp —or the grind , for short—is a traditional Faroese drive hunt that dates back to at least 1298, when the first law regulating the hunt was introduced. Records of the hunt have been kept since 1584 (the longest such archive), and show that an annual average of eight hundred and thirty-eight pilot whales have been killed by the Faroese during the past three centuries. The grind has long been the focus of anti-whaling advocacy: gruesome photographs showing rows of black whale corpses, their necks slit, floating in a sea bright red with blood, spark outrage on Facebook and Twitter. Faroese defenders of the grind argue that the hunt is not only a traditional part of their culture but also a sustainable and ecologically friendly practice. They point out that they monitor the pilot-whale population, and hunt only a small proportion each year, consuming what they kill. In an extreme northerly landscape that does not support agriculture, the Faroese maintain that they still depend on the ocean for their food.

The irony is that pilot whales, like whales the world over, are becoming inedible. Whale blubber stores toxins that have made their way to the sea, in the form of agricultural and mining runoff or condensed emissions—an effect magnified by whales’ longevity. Mercury levels in pilot whales are so elevated that scientists have advised the Faroese to drastically reduce their consumption of whale meat, which might in turn force them to import farmed protein from elsewhere, increasing their carbon impact. The breast milk of Inuit women in Greenland, one of the least industrialized places on earth, has, because of mercury levels in beluga whales and other marine animals, become a dangerous substance. Some studies suggest that the Inuit’s mercury exposure is comparable to that of people living downstream from gold mines in China. Orca in Washington’s Puget Sound have been declared among the earth’s most toxified animals; the carcasses of beluga whales that wash up on the shores of Canada are classified as toxic waste. The most prolific whale killers are no longer the whale hunters. They are, instead, the rest of us: creatures of late capitalism whose patterns of consumption make us complicit, however unwittingly or unwillingly, in an unfolding mass biocide.

Whales consume much of the eight million metric tons of plastic that enter the oceans each year, which gather in swirling trash vortexes known as gyres and can extend for miles. Often, this plastic is from packaging that allows us to consume non-seasonal food year-round. A sperm whale that recently washed up on the Spanish coast had an entire greenhouse in its belly: the flattened structure, together with the tarps, hosepipes, ropes, flowerpots, and spray cannister it had contained. The greenhouse was from an Andalusian hydroponics business, used to grow tomatoes for export to colder climes. Food waste produced by the globalized supply chain accounts for eight per cent of carbon emissions (air travel accounts for only about 2.5 per cent), which melt the ice on which whales depend indirectly for their food. Since the nineteen-seventies, with the loss of ice-fixed algae, Antarctic krill populations have declined by between seventy and eighty per cent. Noise from industrial shipping—eighty per cent of the world’s merchandise is transported on cargo vessels—has shrunk the whale’s world: the distance over which a whale’s vocalizations can travel is just one-tenth of what it was sixty years ago. Whales have washed up on the Peloponnesian coast with ears bleeding from decompression injuries caused by anti-submarine-warfare training.

Ecologists have warned that the dramatic shifts associated with climate change could subject even relatively large whale populations to sudden extinction. There are signs that this is already happening. In 2015, three hundred and forty-three sei whales, an endangered species, were found dead on the coast of Chilean Patagonia, likely because of a toxic algae bloom. The seis, scientists said, could be “among the first oceanic megafauna victims of global warming.” Meanwhile, because whales are enormous carbon sinks, the era of commercial whaling hastened today’s climate crisis. According to one estimate, a century of whaling equates to the burning of seventy million acres of forest. The people of the Lummi Nation, who live on the coast of the Salish Sea, between the U.S. and Canada, have started to feed salmon to wild orca that are starving because of the effects of pollution and climate change. “Those are our relations under the waves,” one Lummi tribal member said.

On an Argentine beach in 2017, a stranded baby dolphin was killed by a mob of tourists intent on taking selfies with it. Something similar had happened in Argentina the year before, when a baby La Plata dolphin washed up at a Santa Teresita beach; the animal was passed from tourist to tourist until it died of dehydration. Ecological historians may one day write about the early twenty-first century as a time of frenzied cultural obsession with wild animals: anime-eyed lorises, badass honey badgers, “trash panda” raccoons. As Rebecca Giggs observes, this frenzy has been facilitated by the rise of social media. On Twitter and Facebook, animal cuteness has become the only antidote to political fury. Instagram encourages us to curate our encounters with the extraordinary, so that we may ourselves seem extraordinary. Driven by a search for the perfectly “grammable” shot, ecotourism is everywhere on the rise, though it rarely delivers on the promise of its name, which is to reconcile the impulse to consume nature with the desire to conserve it. At least thirteen million people worldwide have been going on whale-watching tours each year, leading to more and faster diesel-powered boats. Wildflower superblooms are trampled by social-media influencers. Thousands of recreational drones—like the one that produced that video of the whale swimming through the surfers off Dana Point—disturb the wildlife they so rapturously capture.

Future historians will have the task of explaining how our performative love for animals relates to our relentless extermination of them. It is not simply a lack of knowledge. Could the Argentine tourists not sense the dolphin going limp in their arms? Don’t many of us acknowledge the contradiction of flying across the world to lose ourselves in nature? Who doesn’t grasp the vulnerability of the world to our collective power? Perhaps it’s something more like willful self-deception: a refusal to believe what it is we know. Or perhaps we are simply embracing what we sense will soon be gone, memorializing what does not really exist, as social media has taught us to do. Here is my fabulous holiday; here is my happy wedding day; here is the vast ocean; here is a whale. ♦

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Kyle Chayka

By Eric Lach

By Amanda Petrusich

This is how humans have affected whale populations over the years

WWF founder Sir Peter Scott said: “If we cannot save the whales from extinction, we have little hope of saving mankind and the life-supplying biosphere.” Image: Todd Cravens/Unsplash

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Kate Whiting

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Future of the Environment is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, future of the environment.

“The living whale, in his full majesty and significance, is only to be seen at sea in unfathomable waters; and afloat the vast bulk of him is out of sight…”

So wrote the American author Herman Melville in his hefty 1851 novel about the hunt for the white sperm whale Moby Dick, inspired by his own adventures aboard whaling ships.

The planet’s biggest mammals have been hunted for thousands of years.

Have you read?

Ships are silencing the songs of humpback whales. this is why that matters, why we are using these custom-built drones to collect whale snot, why the ocean holds the key to sustainable development.

For many indigenous communities, including the Inuit hunting in the Arctic Ocean, whaling was a means of survival, providing food and even shelter, as whalebone could be used for roofing .

Livelihoods and local economies in seafaring nations such as Japan and Norway were built on the meat, oil from the blubber and whalebone, or baleen - used in hoop skirts and corsets.

Some species, including the western South Atlantic (WSA) humpback, may have recovered from the brink of extinction to their pre-whaling population , but several others are still endangered.

With whaling ongoing, and plastic pollution and global warming changing their ocean habitat, there are plenty of reasons the whales still need saving.

No doubt Melville would have been intrigued by the changing tides of fortune that have washed over cetaceans since his death in 1891. Here’s a salty, potted history of human and whale relations over the last century: 1900s: The hunt intensifies In the 1800s, whaling had caught on in Melville’s home country and whale oil for lighting lamps became a multi-million dollar industry until fossil fuels took over in popularity. Commercial whaling hit its peak in the early 1900s. Between 1904 and 1916 it’s estimated nearly 25,000 WSA humpbacks were caught around South Georgia. A total of 2 million whales were killed in the Southern Ocean during the 20th century.

1946: International action

In response to depleting numbers of cetaceans, including the near-extinction of the blue whale, several countries came together to sign the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling and establish a global body to manage whaling .

The International Whaling Commission (IWC) currently has 88 members and its role has grown to tackle conservation issues including bycatch and entanglement, ocean noise, pollution and debris, collisions between whales and ships, and sustainable whale watching.

1960s: Save the whale

In 1961, another global conservation organization was born - the World Wildlife Fund or WWF. That year alone, 66,000 whales were killed in the Antarctic , and hunting was still happening in many other parts of the world.

WWF founder Sir Peter Scott said: “If we cannot save the whales from extinction, we have little hope of saving mankind and the life-supplying biosphere.”

"Save the whale" became one of the charity’s first rallying cries and it pioneered ground-breaking research techniques, including the recording of underwater vocalizations - or whale song - and photographing examples of the bond between mothers and their calves.

1980s: The moratorium

Members of the IWC agreed to ‘pause’ commercial whaling to allow whale numbers to recover, and the moratorium began in 1986. The global trade of whale products was banned and quotas were set for subsistence whaling to support indigenous communities. Special permits were given to allow ‘scientific’ whaling, which countries including Japan continued to do.

Today: Mixed success

The moratorium was largely successful, with the population of Western gray whales increasing from 115 individuals in 2004 to 174 in 2015. The WSA humpback whale , which numbered fewer than 1,000 for nearly 40 years, has recovered to close to 25,000, according to the latest study.

“I think there is pretty good evidence that a moratorium on hunting has allowed certain populations to recover from depleted status when they were being whaled,” Dave Weller, a research biologist in California, told National Geographic.

But the WWF says six out of the 13 baleen whale species are still endangered. The North Atlantic right whale is critically endangered , with numbers dropping from 524 in 2015 to 412 in 2018. As climate change causes its migration patterns to shift, the species is more at risk from collisions with ships as well as lethal entanglement in fishing gear.

Earlier this year, Japan left the IWC and has resumed commercial whaling in its waters, saying hunting and eating whale meat is part of the nation’s culture.

Only more time will tell what impact the move may have on the future of whales and the whaling industry.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Future of the Environment .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

These 6 countries are using space technology to build their digital capabilities. Here’s how

Simon Torkington

April 8, 2024

4 charts to show why adopting a circular economy matters

Victoria Masterson

April 4, 2024

4 lessons from Jane Goodall as the renowned primatologist turns 90

Gareth Francis

April 3, 2024

What to do with ageing oil and gas platforms – and why it matters

April 2, 2024

Melting ice caps slowing Earth's rotation, study shows, and other nature and climate stories you need to read this week

Johnny Wood

2023 the hottest year on record, and other nature and climate stories you need to read this week

Meg Jones and Joe Myers

March 25, 2024

Blue Whale: Why Is It Endangered?

By: Author Our Endangered World

Posted on Last updated: September 26, 2023

Are you aware there is an animal on Earth that is bigger than the largest dinosaur and longer than a full-size basketball court? This gigantic animal is the blue whale!

In our oceans today, there are approximately 10,000 and 25,000 blue whales. Although this may seem like plenty, blue whales are endangered. Today, blue whales are listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act and protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

This is because, since the late 1800s, many blue whales have perished because of human activities.

Blue whales are among the biggest animals that have ever existed on our planet. Their population has fallen by 98% over the past century due to human overfishing, whaling , pollution, and other reasons.

- Status : Endangered

- Known as : Blue Whale.

- Estimated numbers left in the wild : 10,000 to 25,000.

Blue whales were first sighted by Europeans in 1758. But it wasn’t until 1904 that samples of whale organs were first recorded by marine biologists. They are currently listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Let us take a closer look and discover why blue whales are endangered. And how people can help save these animals from extinction.

Table of Contents

Description

The Blue whale is the largest animal on Earth. It can grow as long as a Boeing 737-100 airplane (about 30 meters). They have grey and have a distinct mustache-like pattern.

Blue whales filter seawater through massive, slatted plates in their mouths, known as baleen. Large amounts of water are taken in and then squeezed out forcefully through the gaps in the baleen by their tongue.

It allows these massive creatures to harvest vast numbers of tiny animals called krill, similar to shrimp, which make up most of their diet. One adult whale has a feeding ability of around 3.6 tonnes of krill daily. A whale’s mouth can hold 90 tonnes of water, and its tongue weighs 2.7 tonnes.

See Related : Three-Letter Animals You’ve Probably Never Heard Of

Blue Whale Population

The blue whale is not a common animal. Its population currently in the world is dangerously low and in grave danger due to various reasons.

Some reasons are ocean pollution , habitat degradation, and being hunted by hungry humans. Whales have been going extinct for a long time, but it has been much worse recently.

Since the 1970s, the global blue whale population has dropped from 20 million to only 500. Their population decreased by 98% during that period.

See Related : What is Overfishing? Examples & Solutions to Prevent

Most blue whales are concentrated in most oceans, including the North Atlantic Ocean, the Eastern North Pacific, the Indian Ocean, and the Antarctic Ocean. Blue whales can only live in deep oceanic areas, preferring cold regions with abundant krill, except during breeding season, when they migrate closer to the equator.

See Related : Reasons Why Biodiversity Important to Ecosystems

Blue Whale Distribution

Blue whales migrate to different areas at different times of the year. They usually live in colder waters, but their migration depends on their summer feeding grounds and winter breeding grounds.

Role in the Ecosystem

Blue whales play a crucial role in the ecosystem as they recycle nutrients and oxygen. These creatures are a significant part of the marine ecosystem .

They help balance the ocean’s ecosystems by eating krill and plankton. They eat about four tons of krill and plankton a day to help keep the population in check.

Blue whales are still part of the human food chain (and even the pet food chain) as they are hunted for meat and whale oil. Unfortunately, these events depopulated them because of commercial hunting before 1966. Other threats that endanger blue whales are vessel disturbance and fishing gear entanglements.

Blue Whale vs Other Whale Species

For starters, blue whales are much larger than other whales. They can range from 100 to 110 feet and weigh as much as 200 tons, while the next largest species are between 60 and 80 feet.

Blue whales are often confused with humpback whales, but they are different species. Humpback whales have huge mouths, humps under their heads, and long tails full of large baleen plates at the bottom.

See Related : Best Conservation Posters

Blue Whale and Human Relationship

Blue whales and humans have had a relationship for centuries. Blue whales are known to be gentle, but they were hunted by humans who used their meat for food , their oil for lamps, and their bones for fashion.

With the outside possibility of these gentle giants tipping over small boats, these creatures don’t endanger humans. On the contrary, they are endangered because of humans. Human-whale conflict is a natural phenomenon in terms of humans’ tendency to corrupt nature.

Blue whales are social animals that like to communicate with each other by making loud noises, known as whalesong, which is why they’ve earned the title “bringers of joy.”

When blue whales try to feed near shore, humans often chase them away for both parties’ safety.

Blue whales have also been hit by ships so often that whale-watching vessels must be accompanied by an escort boat to prevent these species from being injured. They face many threats, making them go extinct quicker than the average animal.

Blue Whale SubSpecies

There are five currently recognized subspecies of blue whales in the world’s oceans: the Pygmy, the Antarctic, the Northern, Northern Indian Ocean, and the Chilean subspecies. There are debates about the last one, but we will enlighten you more as we go on.

1. Pygmy Blue Whales (Balaenoptera musculus brevicauda )

Pygmy subspecies are much smaller than normal blue whales, weighing only 1.5 tons. They dominate other blue whale species based on population.

They can be found in all oceans except for the Arctic Ocean. The Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region covers the conservation of their species.

2. Antarctic Blue Whales (Balaenoptera musculus intermedia)

The Antarctic blue whales are the largest subspecies of blue whales. They are also among the most endangered whales.

The population of Antarctic whale species has decreased by 99%. It lives in the cold waters near Antarctica and eats small fish and krill.

3. Northern Blue Whales ( Balaenoptera musculus Linnaeus)

The northern blue whale can be found in the North Atlantic, the Eastern North Pacific, and the Central/Western Pacific Oceans. Some of them stay in their areas for a year.

The Northern subspecies have a thick layer of blubber, which helps to keep it warm in the cold water. The Northern subspecies also have a dark gray color, which helps to camouflage it from predators.

4. Northern Indian Ocean Blue Whales ( Balaenoptera musculus indica)

The Northern Indian Ocean blue whale subspecies are smaller than other blue whales. They are found in the northern Indian Ocean and are also darker in color.

5. Chilean Blue Whales ( Balaenoptera musculus un-named subsp)

The Chilean blue whale subspecies is the smallest of the subspecies. They are found off the coast of Chile. It is not clear why this subspecies is smaller, but the smaller size may be an adaptation to the colder waters in Chile. Their genetics and geographic separation spark debates about their distinction.

Conservation Status

Blue whales are an endangered species because 98% of their population was wiped out in the last century, mainly because of hunting . Blue whale populations have been able to recover since their commercial hunting ended through an international agreement in 1966.

Whale Poaching

Whale poaching is the illegal hunting of blue whales. It is a major contributor to the current decline in blue whale populations and ocean health.

The blue whale was immune to human whalers for centuries, thanks to its size, strength, and speed. The introduction of the harpoon gun in the 19th Century started the harvesting of this giant creature.

Over 300,000 killed blue whales were recorded before the 1966 ban, with the Soviet Union continuing illegal whaling into the 1970s and Japan continuing to hunt whales in the name of science. The main reason people poach whales is for their meat.

Ship Accidents

Blue whales are often struck accidentally in shipping lanes, which can easily injure or kill them. Whales often collide with ships in the California Current – one of the whales’ favorite feeding grounds. They can also get tangled and strangled in fishing gear.

Water Pollution

One of the main threats to Blue whales is water pollution . This pollution can come from several sources, including oil spills, agricultural runoff, and chemical pollutants. These pollutants can seriously harm Blue whales and some cases, even kill them. They may be endangered further by alterations in krill populations due to global warming, heating the oceans, making it hard for krill to breed and live.

Ocean Noise

Ships give off noise pollution, which makes it difficult for whales to communicate with each other underwater. This can cause blue whales to beach themselves.

See Related : Dusky Shark

Conservation efforts

Conservation efforts to protect blue whales began in 1966 with the passage of the ban on commercial whaling. Attempts to conserve, restore, and study these gigantic marine mammals are ongoing. Both non-profit organizations and various governments are involved in efforts to foster their recovery.

There is cooperation between countries to help conserve whales. The United States Fishery Management Plan is one of the most successful practices used for whale conservation, with 50% of blue whales located in the USA’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Continued research into blue whales is also essential for blue whale conservation.

Whale Sanctuaries

Many conservation efforts to save whales are in progress. Some of these include creating whale sanctuaries, acoustic deterrents, and reducing ship collisions and noise pollution.

Whale sanctuaries are areas where blue whales can live without being disturbed. Acoustic deterrents emit sounds that scare whales away from areas.

Marine Mammal Science and Research Program

This program is the most comprehensive study on blue whales. The goal is to get an accurate count of the populations of blue whales, assess their distribution and migratory habits, and learn how they communicate with each other.

Educational Programs

Educational programs for whale conservation are for everyone. You can start such activities by researching whales and the issues of blue whales in the ocean.

Whale Watching Trips

Whale-watching trips are a great way to help whale conservation. It allows people to see these beautiful animals up close and learn more about them.

It will create awareness about the need to protect them and their habitat . Whale-watching trips also provide revenue for whale conservation efforts.

Pollution control

One of the main reasons why whales are endangered is because they are affected by pollution. There are many things that people can do to help reduce pollution and protect whales. Some include reducing plastic produced, driving less and using public transportation more, recycling, and composting .

Online Campaigns

Whale online campaigns are a great way to raise awareness about the endangered blue whale. Some of the things that you can do to help blue whales include:

- Signing petitions to get these species protected

- Sharing information about the whales on social media using hashtag #SavetheBWs

- Donating money to organizations that are working to protect whales

- Volunteering your time to help with whale conservation efforts

Organizations

The hebridean whale & dolphin trust.

The Hebridean Whale & Dolphin Trust monitors marine mammals and their habitats off the coast of Scotland. They protect various species through outreach and educational programs.

The Hebridean Whale & Dolphin Trust is a non-profit organization established in 2008. It aims to study, conserve and protect whales and dolphins . They operate through their two research vessels, The Sea Watch Foundation, Blue Ventures, and various networks promoting sustainable fishing practices.

World Wildlife Fund

The World Wildlife Fund is a global organization that conserves animals and their habitats. One of the main focuses of WWF is the conservation of blue whales. They protect whales by developing partnerships with governments, businesses, and other organizations.