Blog about Writing Case Study and Coursework

dudestudy.com

How to Write an Introduction for a Case Study Report

If you’re looking for examples of how to write an introduction for a case-study report, you’ve come to the right place. Here you’ll find a sample, guidelines for writing a case-study introduction, and tips on how to make it clear. In five minutes or less, recruiters will read your case study and decide whether you’re a good fit for the job.

Example of a case study introduction

An example of a case study introduction should be written to provide a roadmap for the reader. It should briefly summarize the topic, identify the problem, and discuss its significance. It should include previous case studies and summarize the literature review. In addition, it should include the purpose of the study, and the issues that it addresses. Using this example as a guideline, writers can make their case study introductions. Here are some tips:

The first paragraph of the introduction should summarize the entire article, and should include the following sections: the case presentation, the examinations performed, and the working diagnosis, the management of the case, and the outcome. The final section, the discussion, should summarize the previous subsections, explain any apparent inconsistencies, and describe the lessons learned. The body of the paper should also summarize the introduction and include any notes for the instructor.

The last section of a case study introduction should summarize the findings and limitations of the study, as well as suggestions for further research. The conclusion section should restate the thesis and main findings of the case study. The conclusion should summarize previous case studies, summarize the findings, and highlight the possibilities for future study. It is important to note that not all educational institutions require the case study analysis format, so it is important to check ahead of time.

The introductory paragraph should outline the overall strategy for the study. It should also describe the short-term and long-term goals of the case study. Using this method will ensure clarity and reduce misunderstandings. However, it is important to consider the end goal. After all, the objective is to communicate the benefits of the product. And, the solution should be measurable. This can be done by highlighting the benefits and minimizing the negatives.

Structure of a case study introduction

The structure of a case study introduction is different from the general introduction of a research paper. The main purpose of the introduction is to set the stage for the rest of the case study. The problem statement must be short and precise to convey the main point of the study. Then, the introduction should summarize the literature review and present the previous case studies that have dealt with the topic. The introduction should end with a thesis statement.

The thesis statement should contain facts and evidence related to the topic. Include the method used, the findings, and discussion. The solution section should describe specific strategies for solving the problem. It should conclude with a call to action for the reader. When using quotations, be sure to cite them properly. The thesis statement must include the problem statement, the methods used, and the expected outcome of the study. The conclusion section should state the case study’s importance.

In the discussion section, state the limitations of the study and explain why they are not significant. In addition, mention any questions unanswered and issues that the study was unable to address. For more information, check out the APA, Harvard, Chicago, and MLA citation styles. Once you know how to structure a case study introduction, you’ll be ready to write it! And remember, there’s always a right and wrong way to write a case study introduction.

During the writing process, you’ll need to make notes on the problems and issues of the case. Write down any ideas and directions that come to mind. Avoid writing neatly. It may impede your creative process, so write down a rough draft first, and then draw it up for your educational instructor. The introduction is an overview of the case study. Include the thesis statement. If you’re writing a case study for an assignment, you’ll also need to provide an overview of the assignment.

Guidelines for writing a case study introduction

A case study is not a formal scientific research report, but it is written for a lay audience. It should be readable and follow the general narrative that was determined in the first step. The introduction should provide background information about the case and its main topic. It should be short, but should introduce the topic and explain its context in just one or two paragraphs. An ideal case study introduction is between three and five sentences.

The case study must be well-designed and logical. It cannot contain opinions or assumptions. The research question must be a logical conclusion based on the findings. This can be done through a spreadsheet program or by consulting a linguistics expert. Once you have identified the major issues, you need to revise the paper. Once you have revised it twice, it should be well-written, concise, and logical.

The conclusion should state the findings, explain their significance, and summarize the main points. The conclusion should move from the detailed to the general level of consideration. The conclusion should also briefly state the limitations of the case study and point out the need for further research in order to fully address the problem. This should be done in a manner that will keep the reader interested in reading the paper. It should be clear about what the case study found and what it means for the research community.

The case study begins with a cover page and an executive summary, depending on your professor’s instructions. It’s important to remember that this is not a mandatory element of the case study. Instead, the executive summary should be brief and include the key points of the study’s analysis. It should be written as if an executive would read it on the run. Ultimately, the executive summary should include all the key points of the case study.

Clarity in a case study introduction

Clarity in a case study introduction should be at the heart of the paper. This section should explain why the case was chosen and how you decided to use it. The case study introduction varies according to the type of subject you are studying and the goals of the study. Here are some examples of clear and effective case study introductions. Read on to find out how to write a successful one. Clarity in a case study introduction begins with a strong thesis statement and ends with a compelling conclusion.

The conclusion of the case study should restate the research question and emphasize its importance. Identify and restate the key findings and describe how they address the research question. If the case study has limitations, discuss the potential for further research. In addition, document the limitations of the case study. Include any limitations of the case study in the conclusion. This will allow readers to make informed decisions about whether or not the findings are relevant to their own practices.

A case study introduction should include a brief discussion of the topic and selected case. It should explain how the study fits into current knowledge. A reader may question the validity of the analysis if it fails to consider all possible outcomes. For example, a case study on railroad crossings may fail to document the obvious outcome of improving the signage at these intersections. Another example would be a study that failed to document the impact of warning signs and speed limits on railroad crossings.

As a conclusion, the case study should also contain a discussion of how the research was conducted. While it may be a case study, the results are not necessarily applicable to other situations. In addition to describing how a solution has solved the problem, a case study should also discuss the causes of the problem. A case study should be based on real data and information. If the case study is not valid, it will not be a good fit for the audience.

Sample of a case study introduction

A good case study introduction serves as a map for the reader to follow. It should identify the research problem and discuss its significance. It should be based on extensive research and should incorporate relevant issues and facts. For example, it may include a short but precise problem statement. The next section of the introduction should include a description of the solution. The final part of the introduction should conclude with the recommended action. Once the reader has a sense of the direction the study will take, they will feel confident in pursuing the study further.

In the case of social sciences, case studies cannot be purely empirical. The results of a case study can be compared with those of other studies, so that the case study’s findings can be assessed against previous research. A case study’s results can help support general conclusions and build theories, while their practical value lies in generating hypotheses. Despite their utility, case studies often contain a bias toward verification and tend to confirm the researcher’s preconceived notions.

In the case of case studies, the conclusions section should state the significance of the findings, stating how the findings of the study differ from other previous studies. Likewise, the conclusion section should summarize the key findings, and make the reader understand how they address the research problem. In the case of a case study, it is crucial to document any limitations that have been identified. After all, a case study is not complete without further research.

After the introduction, the main body of the paper is the case presentation. It should provide information about the case, such as the history, examination results, working diagnosis, management, and outcome. It should conclude with a discussion, explaining the correlations, apparent inconsistencies, and lessons learned. Finally, the conclusion should state whether the case study presented the results in the desired way. The findings should not be overgeneralized, and the conclusions must be derived from this information.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 1, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Writing A Case Study

A Complete Case Study Writing Guide With Examples

People also read

Simple Case Study Format for Students to Follow

Understand the Types of Case Study Here

Brilliant Case Study Examples and Templates For Your Help

Many writers find themselves grappling with the challenge of crafting persuasive and engaging case studies.

The process can be overwhelming, leaving them unsure where to begin or how to structure their study effectively. And, without a clear plan, it's tough to show the value and impact in a convincing way.

But don’t worry!

In this blog, we'll guide you through a systematic process, offering step-by-step instructions on crafting a compelling case study.

Along the way, we'll share valuable tips and illustrative examples to enhance your understanding. So, let’s get started.

- 1. What is a Case Study?

- 2. Types of Case Studies

- 3. How To Write a Case Study - 9 Steps

- 4. Case Study Methods

- 5. Case Study Format

- 6. Case Study Examples

- 7. Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies

What is a Case Study?

A case study is a detailed analysis and examination of a particular subject, situation, or phenomenon. It involves comprehensive research to gain a deep understanding of the context and variables involved.

Typically used in academic, business, and marketing settings, case studies aim to explore real-life scenarios, providing insights into challenges, solutions, and outcomes. They serve as valuable tools for learning, decision-making, and showcasing success stories.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Types of Case Studies

Case studies come in various forms, each tailored to address specific objectives and areas of interest. Here are some of the main types of case studies :

- Illustrative Case Studies: These focus on describing a particular situation or event, providing a detailed account to enhance understanding.

- Exploratory Case Studies: Aimed at investigating an issue and generating initial insights, these studies are particularly useful when exploring new or complex topics.

- Explanatory Case Studies: These delve into the cause-and-effect relationships within a given scenario, aiming to explain why certain outcomes occurred.

- Intrinsic Case Studies: Concentrating on a specific case that holds intrinsic value, these studies explore the unique qualities of the subject itself.

- Instrumental Case Studies: These are conducted to understand a broader issue and use the specific case as a means to gain insights into the larger context.

- Collective Case Studies: Involving the study of multiple cases, this type allows for comparisons and contrasts, offering a more comprehensive view of a phenomenon or problem.

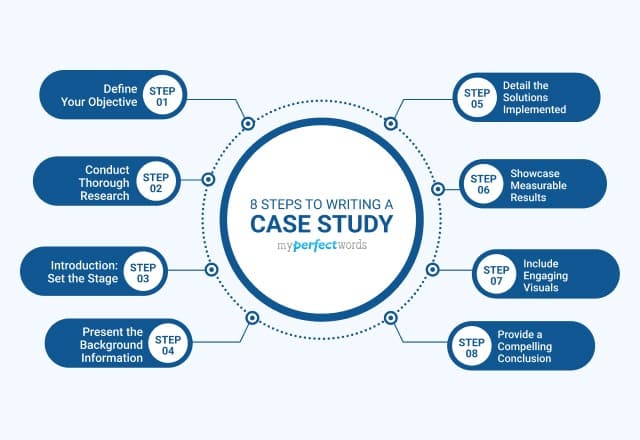

How To Write a Case Study - 9 Steps

Crafting an effective case study involves a structured approach to ensure clarity, engagement, and relevance.

Here's a step-by-step guide on how to write a compelling case study:

Step 1: Define Your Objective

Before diving into the writing process, clearly define the purpose of your case study. Identify the key questions you want to answer and the specific goals you aim to achieve.

Whether it's to showcase a successful project, analyze a problem, or demonstrate the effectiveness of a solution, a well-defined objective sets the foundation for a focused and impactful case study.

Step 2: Conduct Thorough Research

Gather all relevant information and data related to your chosen case. This may include interviews, surveys, documentation, and statistical data.

Ensure that your research is comprehensive, covering all aspects of the case to provide a well-rounded and accurate portrayal.

The more thorough your research, the stronger your case study's foundation will be.

Step 3: Introduction: Set the Stage

Begin your case study with a compelling introduction that grabs the reader's attention. Clearly state the subject and the primary issue or challenge faced.

Engage your audience by setting the stage for the narrative, creating intrigue, and highlighting the significance of the case.

Step 4: Present the Background Information

Provide context by presenting the background information of the case. Explore relevant history, industry trends, and any other factors that contribute to a deeper understanding of the situation.

This section sets the stage for readers, allowing them to comprehend the broader context before delving into the specifics of the case.

Step 5: Outline the Challenges Faced

Identify and articulate the challenges or problems encountered in the case. Clearly define the obstacles that needed to be overcome, emphasizing their significance.

This section sets the stakes for your audience and prepares them for the subsequent exploration of solutions.

Step 6: Detail the Solutions Implemented

Describe the strategies, actions, or solutions applied to address the challenges outlined. Be specific about the decision-making process, the rationale behind the chosen solutions, and any alternatives considered.

This part of the case study demonstrates problem-solving skills and showcases the effectiveness of the implemented measures.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Step 7: Showcase Measurable Results

Present tangible outcomes and results achieved as a direct consequence of the implemented solutions. Use data, metrics, and success stories to quantify the impact.

Whether it's increased revenue, improved efficiency, or positive customer feedback, measurable results add credibility and validation to your case study.

Step 8: Include Engaging Visuals

Enhance the readability and visual appeal of your case study by incorporating relevant visuals such as charts, graphs, images, and infographics.

Visual elements not only break up the text but also provide a clearer representation of data and key points, making your case study more engaging and accessible.

Step 9: Provide a Compelling Conclusion

Wrap up your case study with a strong and conclusive summary. Revisit the initial objectives, recap key findings, and emphasize the overall success or significance of the case.

This section should leave a lasting impression on your readers, reinforcing the value of the presented information.

Case Study Methods

The methods employed in case study writing are diverse and flexible, catering to the unique characteristics of each case. Here are common methods used in case study writing:

Conducting one-on-one or group interviews with individuals involved in the case to gather firsthand information, perspectives, and insights.

- Observation

Directly observing the subject or situation to collect data on behaviors, interactions, and contextual details.

- Document Analysis

Examining existing documents, records, reports, and other written materials relevant to the case to gather information and insights.

- Surveys and Questionnaires

Distributing structured surveys or questionnaires to relevant stakeholders to collect quantitative data on specific aspects of the case.

- Participant Observation

Combining direct observation with active participation in the activities or events related to the case to gain an insider's perspective.

- Triangulation

Using multiple methods (e.g., interviews, observation, and document analysis) to cross-verify and validate the findings, enhancing the study's reliability.

- Ethnography

Immersing the researcher in the subject's environment over an extended period, focusing on understanding the cultural context and social dynamics.

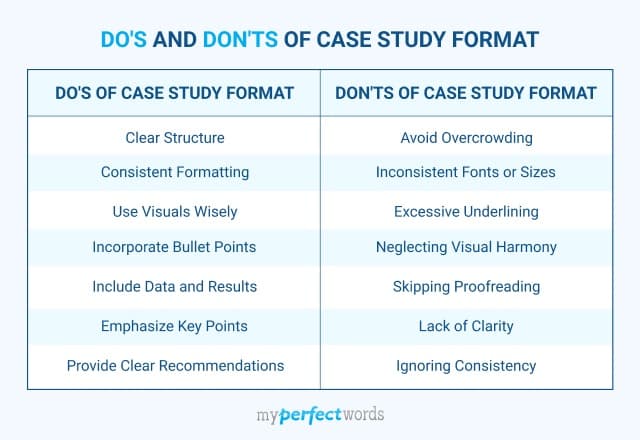

Case Study Format

Effectively presenting your case study is as crucial as the content itself. Follow these formatting guidelines to ensure clarity and engagement:

- Opt for fonts that are easy to read, such as Arial, Calibri, or Times New Roman.

- Maintain a consistent font size, typically 12 points for the body text.

- Aim for double-line spacing to maintain clarity and prevent overwhelming the reader with too much text.

- Utilize bullet points to present information in a concise and easily scannable format.

- Use numbered lists when presenting a sequence of steps or a chronological order of events.

- Bold or italicize key phrases or important terms to draw attention to critical points.

- Use underline sparingly, as it can sometimes be distracting in digital formats.

- Choose the left alignment style.

- Use hierarchy to distinguish between different levels of headings, making it easy for readers to navigate.

If you're still having trouble organizing your case study, check out this blog on case study format for helpful insights.

Case Study Examples

If you want to understand how to write a case study, examples are a fantastic way to learn. That's why we've gathered a collection of intriguing case study examples for you to review before you begin writing.

Case Study Research Example

Case Study Template

Case Study Introduction Example

Amazon Case Study Example

Business Case Study Example

APA Format Case Study Example

Psychology Case Study Example

Medical Case Study Example

UX Case Study Example

Looking for more examples? Check out our blog on case study examples for your inspiration!

Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies

Case studies are a versatile and in-depth research method, providing a nuanced understanding of complex phenomena.

However, like any research approach, case studies come with their set of benefits and limitations. Some of them are given below:

Tips for Writing an Effective Case Study

Here are some important tips for writing a good case study:

- Clearly articulate specific, measurable research questions aligned with your objectives.

- Identify whether your case study is exploratory, explanatory, intrinsic, or instrumental.

- Choose a case that aligns with your research questions, whether it involves an individual case or a group of people through multiple case studies.

- Explore the option of conducting multiple case studies to enhance the breadth and depth of your findings.

- Present a structured format with clear sections, ensuring readability and alignment with the type of research.

- Clearly define the significance of the problem or challenge addressed in your case study, tying it back to your research questions.

- Collect and include quantitative and qualitative data to support your analysis and address the identified research questions.

- Provide sufficient detail without overwhelming your audience, ensuring a comprehensive yet concise presentation.

- Emphasize how your findings can be practically applied to real-world situations, linking back to your research objectives.

- Acknowledge and transparently address any limitations in your study, ensuring a comprehensive and unbiased approach.

To sum it up, creating a good case study involves careful thinking to share valuable insights and keep your audience interested.

Stick to basics like having clear questions and understanding your research type. Choose the right case and keep things organized and balanced.

Remember, your case study should tackle a problem, use relevant data, and show how it can be applied in real life. Be honest about any limitations, and finish with a clear call-to-action to encourage further exploration.

However, if you are having issues understanding how to write a case study, it is best to hire the professionals. Hiring a paper writing service online will ensure that you will get best grades on your essay without any stress of a deadline.

So be sure to check out case study writing service online and stay up to the mark with your grades.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the purpose of a case study.

The objective of a case study is to do intensive research on a specific matter, such as individuals or communities. It's often used for academic purposes where you want the reader to know all factors involved in your subject while also understanding the processes at play.

What are the sources of a case study?

Some common sources of a case study include:

- Archival records

- Direct observations and encounters

- Participant observation

- Facts and statistics

- Physical artifacts

What is the sample size of a case study?

A normally acceptable size of a case study is 30-50. However, the final number depends on the scope of your study and the on-ground demographic realities.

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Dr. Barbara is a highly experienced writer and author who holds a Ph.D. degree in public health from an Ivy League school. She has worked in the medical field for many years, conducting extensive research on various health topics. Her writing has been featured in several top-tier publications.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 25 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

How to Write a Case Study: A Breakdown of Requirements

It can take months to develop a case study. First, a topic must be chosen. Then the researcher must state his hypothesis, and make certain it lines up with the chosen topic. Then all the research must be completed. The case study can require both quantitative and qualitative research, as well as interviews with subjects. Once that is all done, it is time to write the case study.

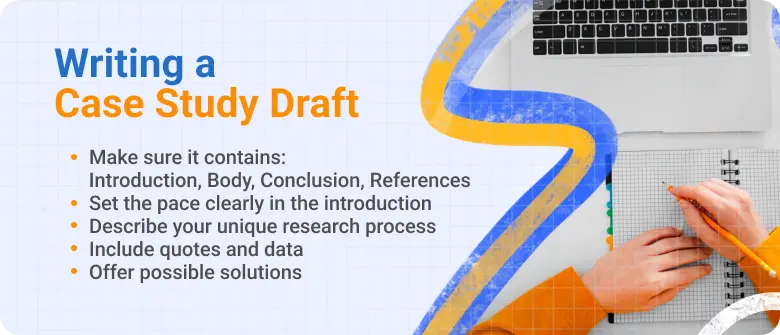

Not all case studies are written the same. Depending on the size and topic of the study, it could be hundreds of pages long. Regardless of the size, the case study should have four main sections. These sections are:

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Presentation of Findings

4. Conclusion

The Introduction

The introduction should set the stage for the case study, and state the thesis for the report. The intro must clearly articulate what the study's intention is, as well as how you plan on explaining and answering the thesis.

Again, remember that a case study is not a formal scientific research report that will only be read by scientists. The case study must be able to be read and understood by the layperson, and should read almost as a story, with a clear narrative.

As the reader reads the introduction, they should fully understand what the study is about, and why it is important. They should have a strong foundation for the background they will learn about in the next section.

The introduction should not be long. You must be able to introduce your topic in one or two paragraphs. Ideally, the introduction is one paragraph of about 3-5 sentences.

The Background

The background should detail what information brought the researcher to pose his hypothesis. It should clearly explain the subject or subjects, as well as their background information. And lastly, the background must give the reader a full understanding of the issue at hand, and what process will be taken with the study. Photos and videos are always helpful when applicable.

When writing the background, the researcher must explain the research methods used, and why. The type of research used will be dependent on the type of case study. The reader should have a clear idea why a particular type of research is good for the field and type of case study.

For example, a case study that is trying to determine what causes PTSD in veterans will heavily use interviews as a research method. Directly interviewing subjects garners invaluable research for the researcher. If possible, reference studies that prove this.

Again, as with the introduction, you do not want to write an extremely long background. It is important you provide the right amount of information, as you do not want to bore your readers with too much information, and you don't want them under-informed.

How much background information should a case study provide? What would happen if the case study had too much background info?

What would happen if the case study had too little background info?

The Presentation of Findings

While a case study might use scientific facts and information, a case study should not read as a scientific research journal or report. It should be easy to read and understand, and should follow the narrative determined in the first step.

The presentation of findings should clearly explain how the topic was researched, and summarize what the results are. Data should be summarized as simply as possible so that it is understandable by people without a scientific background. The researcher should describe what was learned from the interviews, and how the results answered the questions asked in the introduction.

When writing up the report, it is important to set the scene. The writer must clearly lay out all relevant facts and detail the most important points. While this section may be lengthy, you do not want to overwhelm the reader with too much information.

The Conclusion

The final section of the study is the conclusion. The purpose of the study isn't necessarily to solve the problem, only to offer possible solutions. The final summary should be an end to the story.

Remember, the case study is about asking and answering questions. The conclusion should answer the question posed by the researcher, but also leave the reader with questions of his own. The researcher wants the reader to think about the questions posed in the study, and be free to come to their own conclusions as well.

When reading the conclusion, the reader should be able to have the following takeaways:

Was there a solution provided? If so, why was it chosen?

Was the solution supported with solid evidence?

Did the personal experiences and interviews support the solution?

The conclusion should also make any recommendations that are necessary. What needs to be done, and you exactly should do it? In the case of the vets with PTSD, once a cause is determined, who is responsible for making sure the needs of the veterans are met?

English Writing Standards For Case Studies

When writing the case study, it is important to follow standard academic and scientific rules when it comes to spelling and grammar.

Spelling and Grammar

It should go without saying that a thorough spell check should be done. Remember, many case studies will require words or terms that are not in standard online dictionaries, so it is imperative the correct spelling is used. If possible, the first draft of the case study should be reviewed and edited by someone other than yourself.

Case studies are normally written in the past tense, as the report is detailing an event or topic that has since passed. The report should be written using a very logical and clear tone. All case studies are scientific in nature and should be written as such.

The First Draft

You do not sit down and write the case study in one day. It is a long and detailed process, and it must be done carefully and with precision. When you sit down to first start writing, you will want to write in plain English, and detail the what, when and how.

When writing the first draft, note any relevant assumptions. Don't immediately jump to any conclusions; just take notes of any initial thoughts. You are not looking for solutions yet. In the first draft use direct quotes when needed, and be sure to identify and qualify all information used.

If there are any issues you do not understand, the first draft is where it should be identified. Make a note so you return to review later. Using a spreadsheet program like Excel or Google Sheets is very valuable during this stage of the writing process, and can help keep you and your information and data organized.

The Second Draft

To prepare the second draft, you will want to assemble everything you have written thus far. You want to reduce the amount of writing so that the writing is tightly written and cogent. Remember, you want your case study to be interesting to read.

When possible, you should consider adding images, tables, maps, or diagrams to the text to make it more interesting for the reader. If you use any of these, make sure you have permission to use them. You cannot take an image from the Internet and use it without permission.

Once you have completed the second draft, you are not finished! It is imperative you have someone review your work. This could be a coworker, friend, or trusted colleague. You want someone who will give you an honest review of your work, and is willing to give you feedback, whether positive or negative.

Remember, you cannot proofread enough! You do not want to risk all of your hard work and research, and end up with a final case study that has spelling or grammatical errors. One typo could greatly hurt your project and damage your reputation in your field.

All case studies should follow LIT – Logical – Inclusive – Thorough.

The case study obviously must be logical. There can be no guessing or estimating. This means that the report must state what was observed, but cannot include any opinion or assumptions that might come from such an observation.

For example, if a veteran subject arrives at an interview holding an empty liquor bottle and is slurring his words, that observation must be made. However, the researcher cannot make the inference that the subject was intoxicated. The report can only include the facts.

With the Genie case, researchers witnessed Genie hitting herself and practicing self-harm. It could be assumed that she did this when she was angry. However, this wasn't always the case. She would also hit herself when she was afraid, bored or apprehensive. It is essential that researchers not guess or infer.

In order for a report to be inclusive, it must contain ALL data and findings. The researcher cannot pick and choose which data or findings to use in the report.

Using the example above, if a veteran subject arrives for an interview holding an empty liquor bottle and is slurring his words; any and all additional information that can be garnered should be recorded. For instance, what the subject was wearing, what was his demeanor, was he able to speak and communicate, etc.

When observing a man who might be drunk, it can be easy to make assumptions. However, the researcher cannot allow personal biases or beliefs to sway the findings. Any and all relevant facts must be included, regardless of size or perceived importance. Remember, small details might not seem relevant at the time of the interview. But once it is time to catalog the findings, small details might become important.

The last tip is to be thorough. It is important to delve into every observation. The researcher shouldn't just write down what they see and move on. It is essential to detail as much as possible.

For example, when interviewing veteran subjects, there interview responses are not the only information that should be garnered from the interview. The interviewer should use all senses when detailing their subject.

How does the subject appear? Is he clean? How is he dressed?

How does his voice sound? Is he speaking clearly and making cohesive thoughts? Does his voice sound raspy? Does he speak with a whisper, or does he speak too loudly?

Does the subject smell? Is he wearing cologne, or can you smell that he hasn't bathed or washed his clothes? What do his clothes look like? Is he well dressed, or does he wear casual clothes?

What is the background of the subject? What are his current living arrangements? Does he have supportive family and friends? Is he a loner who doesn't have a solid support system? Is the subject working? If so, is he happy with the job? If he is not employed, why is that? What makes the subject unemployable?

Case Studies in Marketing

We have already determined that case studies are very valuable in the business world. This is particularly true in the marketing field, which includes advertising and public relations. While case studies are almost all the same, marketing case studies are usually more dependent on interviews and observations.

Well-Known Marketing Case Studies

DeBeers is a diamond company headquartered in Luxembourg, and based in South Africa. It is well known for its logo, "A diamond is forever", which has been voted the best advertising slogan of the 20 th century.

Many studies have been done about DeBeers, but none are as well known as their marketing case study, and how they positioned themselves to be the most successful and well-known diamond company in the world.

DeBeers developed the idea for a diamond engagement ring. They also invented the "eternity band", which is a ring that has diamonds going all around it, signifying that long is forever.

They also invented the three-stone ring, signifying the past, present and future. De Beers was the first company to attribute their products, diamonds to the idea of love and romance. They originated the idea that an engagement ring should cost two-months salary.

The two-month salary standard is particularly unique, in that it is totally subjective. A ring should mean the same whether the man makes $25,000 a year or $250,000. And yet, the standard sticks due to DeBeers incredible marketing skills.

The De Beers case study is one of the most famous studies when it comes to both advertising and marketing, and is used worldwide as the ultimate example of a successful ongoing marketing campaign.

Planning the Market Research

The most important parts of the marketing case study are:

1. The case study's questions

2. The study's propositions

3. How information and data will be analyzed

4. The logic behind what is being proposed

5. How the findings will be interpreted

The study's questions should be either "how" or "why" questions, and their definitions are the researchers first job. These questions will help determine the study's goals.

Not every case study has a proposition. If you are doing an exploratory study, you will not have propositions. Instead, you will have a stated purpose, which will determine whether your study is successful, or not.

How the information will be analyzed will depend on what the topic is. This would vary depending on whether it was a person, group, or organization. Event and place studies are done differently.

When setting up your research, you will want to follow case study protocol. The protocol should have the following sections:

1. An overview of the case study, including the objectives, topic and issues.

2. Procedures for gathering information and conducting interviews.

3. Questions that will be asked during interviews and data collection.

4. A guide for the final case study report.

When deciding upon which research methods to use, these are the most important:

1. Documents and archival records

2 . Interviews

3. Direct observations (and indirect when possible)

4. Indirect observations, or observations of subjects

5. Physical artifacts and tools

Documents could include almost anything, including letters, memos, newspaper articles, Internet articles, other case studies, or any other document germane to the study.

Developing the Case Study

Developing a marketing case study follows the same steps and procedures as most case studies. It begins with asking a question, "what is missing?"

1. What is the background of the case study? Who requested the study to be done and why? What industry is the study in, and where will the study take place? What marketing needs are you trying to address?

2. What is the problem that needs a solution? What is the situation, and what are the risks? What are you trying to prove?

3. What questions are required to analyze the problem? What questions might the reader of the study have?

4. What tools are required to analyze the problem? Is data analysis necessary? Can the study use just interviews and observations, or will it require additional information?

5. What is your current knowledge about the problem or situation? How much background information do you need to procure? How will you obtain this background info?

6. What other information do you need to know to successfully complete the study?

7. How do you plan to present the report? Will it be a simple written report, or will you add PowerPoint presentations or images or videos? When is the report due? Are you giving yourself enough time to complete the project?

Formulating the Marketing Case Study

1. What is the marketing problem? Most case studies begin with a problem that management or the marketing department is facing. You must fully understand the problem and what caused it. That is when you can start searching for a solution.

However, marketing case studies can be difficult to research. You must turn a marketing problem into a research problem. For example, if the problem is that sales are not growing, you must translate that to a research problem.

What could potential research problems be?

Research problems could be poor performance or poor expectations. You want a research problem because then you can find an answer. Management problems focus on actions, such as whether to advertise more, or change advertising strategies. Research problems focus on finding out how to solve the management problem.

Method of Inquiry

As with the research for most case studies, the scientific method is standard. It allows you to use existing knowledge as a starting point. The scientific method has the following steps:

1. Ask a question – formulate a problem

2. Do background research

3. Formulate a problem

4. Develop/construct a hypothesis

5. Make predictions based on the hypothesis

6. Do experiments to test the hypothesis

7 . Conduct the test/experiment

8 . Analyze and communicate the results

The above terminology is very similar to the research process. The main difference is that the scientific method is objective and the research process is subjective. Quantitative research is based on impartial analysis, and qualitative research is based on personal judgment.

Research Method

After selecting the method of inquiry, it is time to decide on a research method. There are two main research methodologies, experimental research and non-experimental research.

Experimental research allows you to control the variables and to manipulate any of the variables that influence the study.

Non-experimental research allows you to observe, but not intervene. You just observe and then report your findings.

Research Design

The design is the plan for how you will conduct the study, and how you will collect the data. The design is the scientific method you will use to obtain the information you are seeking.

Data Collection

There are many different ways to collect data, with the two most important being interviews and observation.

Interviews are when you ask people questions and get a response. These interviews can be done face-to-face, by telephone, the mail, email, or even the Internet. This category of research techniques is survey research. Interviews can be done in both experimental and non-experimental research.

Observation is watching a person or company's behavior. For example, by observing a persons buying behavior, you could predict how that person will make purchases in the future.

When using interviews or observation, it is required that you record your results. How you record the data will depend on which method you use. As with all case studies, using a research notebook is key, and will be the heart of the study.

Sample Design

When developing your case study, you won't usually examine an entire population; those are done by larger research projects. Your study will use a sample, which is a small representation of the population. When designing your sample, be prepared to answer the following questions:

1. From which type of population should the sample be chosen?

2. What is the process for the selection of the sample?

3. What will be the size of the sample?

There are two ways to select a sample from the general population; probability and non-probability sampling. Probability sampling uses random sampling of everyone in the population. Non-probability sampling uses the judgment of the researcher.

The last step of designing your sample is to determine the sample size. This can depend on cost and accuracy. Larger samples are better and more accurate, but they can also be costly.

Analysis of the Data

In order to use the data, it first must be analyzed. How you analyze the data should be decided upon as early in the process as possible, and will vary depending on the type of info you are collecting, and the form of measurement being used. As stated repeatedly, make sure you keep track of everything in the research notebook.

The Marketing Case Study Report

The final stage of the process is the marketing case study. The final study will include all of the information, as well as detail the process. It will also describe the results, conclusions, and any recommendations. It must have all the information needed so that the reader can understand the case study.

As with all case studies, it must be easy to read. You don't want to use info that is too technical; otherwise you could potentially overwhelm your reader. So make sure it is written in plain English, with scientific and technical terms kept to a minimum.

Using Your Case Study

Once you have your finished case study, you have many opportunities to get that case study in front of potential customers. Here is a list of the ways you can use your case study to help your company's marketing efforts.

1. Have a page on your website that is dedicated to case studies. The page should have a catchy name and list all of the company's case studies, beginning with the most recent. Next to each case study list its goals and results.

2. Put the case study on your home page. This will put your study front and center, and will be immediately visible when customers visit your web page. Make sure the link isn't hidden in an area rarely visited by guests. You can highlight the case study for a few weeks or months, or until you feel your study has received enough looks.

3. Write a blog post about your case study. Obviously you must have a blog for this to be successful. This is a great way to give your case study exposure, and it allows you to write the post directly addressing your audience's needs.

4 . Make a video from your case study. Videos are more popular than ever, and turning a lengthy case study into a brief video is a great way to get your case study in front of people who might not normally read a case study.

5. Use your case study on a landing page. You can pull quotes from the case study and use those on product pages. Again, this format works best when you use market segmentation.

6. Post about your case studies on social media. You can share links on Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn. Write a little interesting tidbit, enough to capture your client's interest, and then place the link.

7 . Use your case study in your email marketing. This is most effective if your email list is segmented, and you can direct your case study to those most likely to be receptive to it.

8. Use your case studies in your newsletters. This can be especially effective if you use segmentation with your newsletters, so you can gear the case study to those most likely to read and value it.

- Course Catalog

- Group Discounts

- Gift Certificates

- For Libraries

- CEU Verification

- Medical Terminology

- Accounting Course

- Writing Basics

- QuickBooks Training

- Proofreading Class

- Sensitivity Training

- Excel Certificate

- Teach Online

- Terms of Service

- Privacy Policy

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.