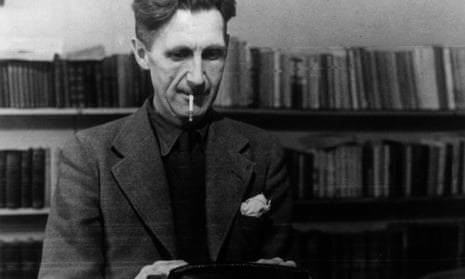

- About George Orwell

- Partners and Sponsors

- Accessibility

- Upcoming events

- The Orwell Festival

- The Orwell Memorial Lectures

- Books by Orwell

- Essays and other works

- Encountering Orwell

- Orwell Live

- About the prizes

- Reporting Homelessness

- Enter the Prizes

- Previous winners

- Orwell Fellows

- Introduction

- Enter the Prize

- Terms and Conditions

- Volunteering

- About Feedback

- Responding to Feedback

- Start your journey

- Inspiration

- Find Your Form

- Start Writing

- Reading Recommendations

- Previous themes

- Our offer for teachers

- Lesson Plans

- Events and Workshops

- Orwell in the Classroom

- GCSE Practice Papers

- The Orwell Youth Fellows

- Paisley Workshops

The Orwell Foundation

- The Orwell Prizes

- The Orwell Youth Prize

Politics and the English Language

This material remains under copyright in some jurisdictions, including the US, and is reproduced here with the permission of the Orwell Estate . If you value these resources, please consider making a donation or joining us as a Friend to help maintain them for readers everywhere.

Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way, but it is generally assumed that we cannot by conscious action do anything about it. Our civilization is decadent and our language – so the argument runs – must inevitably share in the general collapse. It follows that any struggle against the abuse of language is a sentimental archaism, like preferring candles to electric light or hansom cabs to aeroplanes. Underneath this lies the half-conscious belief that language is a natural growth and not an instrument which we shape for our own purposes.

Now, it is clear that the decline of a language must ultimately have political and economic causes: it is not due simply to the bad influence of this or that individual writer. But an effect can become a cause, reinforcing the original cause and producing the same effect in an intensified form, and so on indefinitely. A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks. It is rather the same thing that is happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts. The point is that the process is reversible. Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble. If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers. I will come back to this presently, and I hope that by that time the meaning of what I have said here will have become clearer. Meanwhile, here are five specimens of the English language as it is now habitually written.

These five passages have not been picked out because they are especially bad – I could have quoted far worse if I had chosen – but because they illustrate various of the mental vices from which we now suffer. They are a little below the average, but are fairly representative examples. I number them so that I can refer back to them when necessary:

1. I am not, indeed, sure whether it is not true to say that the Milton who once seemed not unlike a seventeenth-century Shelley had not become, out of an experience ever more bitter in each year, more alien ( sic ) to the founder of that Jesuit sect which nothing could induce him to tolerate. Professor Harold Laski ( Essay in Freedom of Expression ). 2. Above all, we cannot play ducks and drakes with a native battery of idioms which prescribes egregious collocations of vocables as the Basic put up with for tolerate , or put at a loss for bewilder . Professor Lancelot Hogben ( Interglossia ). 3. On the one side we have the free personality: by definition it is not neurotic, for it has neither conflict nor dream. Its desires, such as they are, are transparent, for they are just what institutional approval keeps in the forefront of consciousness; another institutional pattern would alter their number and intensity; there is little in them that is natural, irreducible, or culturally dangerous. But on the other side, the social bond itself is nothing but the mutual reflection of these self-secure integrities. Recall the definition of love. Is not this the very picture of a small academic? Where is there a place in this hall of mirrors for either personality or fraternity? Essay on psychology in Politics (New York). 4. All the ‘best people’ from the gentlemen’s clubs, and all the frantic Fascist captains, united in common hatred of Socialism and bestial horror at the rising tide of the mass revolutionary movement, have turned to acts of provocation, to foul incendiarism, to medieval legends of poisoned wells, to legalize their own destruction of proletarian organizations, and rouse the agitated petty-bourgeoise to chauvinistic fervor on behalf of the fight against the revolutionary way out of the crisis. Communist pamphlet. 5. If a new spirit is to be infused into this old country, there is one thorny and contentious reform which must be tackled, and that is the humanization and galvanization of the B.B.C. Timidity here will bespeak canker and atrophy of the soul. The heart of Britain may be sound and of strong beat, for instance, but the British lion’s roar at present is like that of Bottom in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream – as gentle as any sucking dove. A virile new Britain cannot continue indefinitely to be traduced in the eyes or rather ears, of the world by the effete languors of Langham Place, brazenly masquerading as ‘standard English’. When the Voice of Britain is heard at nine o’clock, better far and infinitely less ludicrous to hear aitches honestly dropped than the present priggish, inflated, inhibited, school-ma’amish arch braying of blameless bashful mewing maidens! Letter in Tribune .

Each of these passages has faults of its own, but, quite apart from avoidable ugliness, two qualities are common to all of them. The first is staleness of imagery; the other is lack of precision. The writer either has a meaning and cannot express it, or he inadvertently says something else, or he is almost indifferent as to whether his words mean anything or not. This mixture of vagueness and sheer incompetence is the most marked characteristic of modern English prose, and especially of any kind of political writing. As soon as certain topics are raised, the concrete melts into the abstract and no one seems able to think of turns of speech that are not hackneyed: prose consists less and less of words chosen for the sake of their meaning, and more and more of phrases tacked together like the sections of a prefabricated hen-house. I list below, with notes and examples, various of the tricks by means of which the work of prose-construction is habitually dodged.

Dying metaphors . A newly invented metaphor assists thought by evoking a visual image, while on the other hand a metaphor which is technically ‘dead’ (e. g. iron resolution ) has in effect reverted to being an ordinary word and can generally be used without loss of vividness. But in between these two classes there is a huge dump of worn-out metaphors which have lost all evocative power and are merely used because they save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves. Examples are: Ring the changes on , take up the cudgels for , toe the line , ride roughshod over , stand shoulder to shoulder with , play into the hands of , no axe to grind , grist to the mill , fishing in troubled waters , on the order of the day , Achilles’ heel , swan song , hotbed . Many of these are used without knowledge of their meaning (what is a ‘rift’, for instance?), and incompatible metaphors are frequently mixed, a sure sign that the writer is not interested in what he is saying. Some metaphors now current have been twisted out of their original meaning without those who use them even being aware of the fact. For example, toe the line is sometimes written as tow the line . Another example is the hammer and the anvil , now always used with the implication that the anvil gets the worst of it. In real life it is always the anvil that breaks the hammer, never the other way about: a writer who stopped to think what he was saying would avoid perverting the original phrase.

Operators, or verbal false limbs . These save the trouble of picking out appropriate verbs and nouns, and at the same time pad each sentence with extra syllables which give it an appearance of symmetry. Characteristic phrases are: render inoperative , militate against , prove unacceptable , make contact with , be subject to , give rise to , give grounds for , have the effect of , play a leading part ( role ) in , make itself felt , take effect , exhibit a tendency to , serve the purpose of , etc. etc. The keynote is the elimination of simple verbs. Instead of being a single word, such as break , stop , spoil , mend , kill , a verb becomes a phrase , made up of a noun or adjective tacked on to some general-purposes verb such as prove , serve , form , play , render . In addition, the passive voice is wherever possible used in preference to the active, and noun constructions are used instead of gerunds ( by examination of instead of by examining ). The range of verbs is further cut down by means of the -ize and de- formations, and banal statements are given an appearance of profundity by means of the not un- formation. Simple conjunctions and prepositions are replaced by such phrases as with respect to , having regard to , the fact that , by dint of , in view of , in the interests of , on the hypothesis that ; and the ends of sentences are saved from anticlimax by such resounding commonplaces as greatly to be desired , cannot be left out of account , a development to be expected in the near future , deserving of serious consideration , brought to a satisfactory conclusion , and so on and so forth.

Pretentious diction . Words like phenomenon , element , individual (as noun), objective , categorical , effective , virtual , basic , primary , promote , constitute , exhibit , exploit , utilize , eliminate , liquidate , are used to dress up simple statements and give an air of scientific impartiality to biassed judgements. Adjectives like epoch-making , epic , historic , unforgettable , triumphant , age-old , inevitable , inexorable , veritable , are used to dignify the sordid processes of international politics, while writing that aims at glorifying war usually takes on an archaic colour, its characteristic words being: realm , throne , chariot , mailed fist , trident , sword , shield , buckler , banner , jackboot , clarion . Foreign words and expressions such as cul de sac , ancien régime , deus ex machina , mutatis mutandis , status quo , Gleichschaltung , Weltanschauung , are used to give an air of culture and elegance. Except for the useful abbreviations i.e ., e.g. , and etc. , there is no real need for any of the hundreds of foreign phrases now current in English. Bad writers, and especially scientific, political and sociological writers, are nearly always haunted by the notion that Latin or Greek words are grander than Saxon ones, and unnecessary words like expedite , ameliorate , predict , extraneous , deracinated , clandestine , sub-aqueous and hundreds of others constantly gain ground from their Anglo-Saxon opposite numbers[1]. The jargon peculiar to Marxist writing ( hyena , hangman , cannibal , petty bourgeois , these gentry , lackey , flunkey , mad dog , White Guard , etc.) consists largely of words translated from Russian, German, or French; but the normal way of coining a new word is to use a Latin or Greek root with the appropriate affix and, where necessary, the -ize formation. It is often easier to make up words of this kind ( deregionalize , impermissible , extramarital , non-fragmentatory and so forth) than to think up the English words that will cover one’s meaning. The result, in general, is an increase in slovenliness and vagueness.

Meaningless words . In certain kinds of writing, particularly in art criticism and literary criticism, it is normal to come across long passages which are almost completely lacking in meaning[2]. Words like romantic , plastic , values , human , dead , sentimental , natural , vitality , as used in art criticism, are strictly meaningless, in the sense that they not only do not point to any discoverable object, but are hardly even expected to do so by the reader. When one critic writes, ‘The outstanding feature of Mr. X’s work is its living quality’, while another writes, ‘The immediately striking thing about Mr. X’s work is its peculiar deadness’, the reader accepts this as a simple difference of opinion. If words like black and white were involved, instead of the jargon words dead and living , he would see at once that language was being used in an improper way. Many political words are similarly abused. The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable’. The words democracy , socialism , freedom , patriotic , realistic , justice , have each of them several different meanings which cannot be reconciled with one another. In the case of a word like democracy , not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it: consequently the defenders of every kind of régime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using that word if it were tied down to any one meaning. Words of this kind are often used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different. Statements like Marshal Pétain was a true patriot , The Soviet press is the freest in the world , The Catholic Church is opposed to persecution , are almost always made with intent to deceive. Other words used in variable meanings, in most cases more or less dishonestly, are: class , totalitarian , science , progressive , reactionary , bourgeois , equality .

Now that I have made this catalogue of swindles and perversions, let me give another example of the kind of writing that they lead to. This time it must of its nature be an imaginary one. I am going to translate a passage of good English into modern English of the worst sort. Here is a well-known verse from Ecclesiastes :

I returned and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

Here it is in modern English:

Objective consideration of contemporary phenomena compels the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account.

This is a parody, but not a very gross one. Exhibit 3 above, for instance, contains several patches of the same kind of English. It will be seen that I have not made a full translation. The beginning and ending of the sentence follow the original meaning fairly closely, but in the middle the concrete illustrations – race, battle, bread – dissolve into the vague phrase ‘success or failure in competitive activities’. This had to be so, because no modern writer of the kind I am discussing – no one capable of using phrases like ‘objective’ consideration of contemporary phenomena’ – would ever tabulate his thoughts in that precise and detailed way. The whole tendency of modern prose is away from concreteness. Now analyse these two sentences a little more closely. The first contains 49 words but only 60 syllables, and all its words are those of everyday life. The second contains 38 words of 90 syllables: 18 of its words are from Latin roots, and one from Greek. The first sentence contains six vivid images, and only one phrase (‘time and chance’) that could be called vague. The second contains not a single fresh, arresting phrase, and in spite of its 90 syllables it gives only a shortened version of the meaning contained in the first. Yet without a doubt it is the second kind of sentence that is gaining ground in modern English. I do not want to exaggerate. This kind of writing is not yet universal, and outcrops of simplicity will occur here and there in the worst-written page. Still if you or I were told to write a few lines on the uncertainty of human fortunes, we should probably come much nearer to my imaginary sentence than to the one from Ecclesiastes .

As I have tried to show, modern writing at its worst does not consist in picking out words for the sake of their meaning and inventing images in order to make the meaning clearer. It consists in gumming together long strips of words which have already been set in order by someone else, and making the results presentable by sheer humbug. The attraction of this way of writing is that it is easy. It is easier – even quicker, once you have the habit – to say In my opinion it is not an unjustifiable assumption that than to say I think . If you use ready-made phrases, you not only don’t have to hunt about for the words; you also don’t have to bother with the rhythms of your sentences, since these phrases are generally so arranged as to be more or less euphonious. When you are composing in a hurry – when you are dictating to a stenographer, for instance, or making a public speech – it is natural to fall into a pretentious, latinized style. Tags like a consideration which we should do well to bear in mind or a conclusion to which all of us would readily assent will save many a sentence from coming down with a bump. By using stale metaphors, similes and idioms, you save much mental effort, at the cost of leaving your meaning vague, not only for your reader but for yourself. This is the significance of mixed metaphors. The sole aim of a metaphor is to call up a visual image. When these images clash – as in The Fascist octopus has sung its swan song , the jackboot is thrown into the melting pot – it can be taken as certain that the writer is not seeing a mental image of the objects he is naming; in other words he is not really thinking. Look again at the examples I gave at the beginning of this essay. Professor Laski (1) uses five negatives in 53 words. One of these is superfluous, making nonsense of the whole passage, and in addition there is the slip alien for akin, making further nonsense, and several avoidable pieces of clumsiness which increase the general vagueness. Professor Hogben (2) plays ducks and drakes with a battery which is able to write prescriptions, and, while disapproving of the everyday phrase put up with , is unwilling to look egregious up in the dictionary and see what it means. (3), if one takes an uncharitable attitude towards it, is simply meaningless: probably one could work out its intended meaning by reading the whole of the article in which it occurs. In (4) the writer knows more or less what he wants to say, but an accumulation of stale phrases chokes him like tea-leaves blocking a sink. In (5) words and meaning have almost parted company. People who write in this manner usually have a general emotional meaning – they dislike one thing and want to express solidarity with another – but they are not interested in the detail of what they are saying. A scrupulous writer, in every sentence that he writes, will ask himself at least four questions, thus: What am I trying to say? What words will express it? What image or idiom will make it clearer? Is this image fresh enough to have an effect? And he will probably ask himself two more: Could I put it more shortly? Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly? But you are not obliged to go to all this trouble. You can shirk it by simply throwing your mind open and letting the ready-made phrases come crowding in. They will construct your sentences for you – even think your thoughts for you, to a certain extent – and at need they will perform the important service of partially concealing your meaning even from yourself. It is at this point that the special connection between politics and the debasement of language becomes clear.

In our time it is broadly true that political writing is bad writing. Where it is not true, it will generally be found that the writer is some kind of rebel, expressing his private opinions, and not a ‘party line’. Orthodoxy, of whatever colour, seems to demand a lifeless, imitative style. The political dialects to be found in pamphlets, leading articles, manifestos, White Papers and the speeches of Under-Secretaries do, of course, vary from party to party, but they are all alike in that one almost never finds in them a fresh, vivid, home-made turn of speech. When one watches some tired hack on the platform mechanically repeating the familiar phrases – bestial atrocities , iron heel , blood-stained tyranny , free peoples of the world , stand shoulder to shoulder – one often has a curious feeling that one is not watching a live human being but some kind of dummy: a feeling which suddenly becomes stronger at moments when the light catches the speaker’s spectacles and turns them into blank discs which seem to have no eyes behind them. And this is not altogether fanciful. A speaker who uses that kind of phraseology has gone some distance toward turning himself into a machine. The appropriate noises are coming out of his larynx, but his brain is not involved as it would be if he were choosing his words for himself. If the speech he is making is one that he is accustomed to make over and over again, he may be almost unconscious of what he is saying, as one is when one utters the responses in church. And this reduced state of consciousness, if not indispensable, is at any rate favourable to political conformity.

In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible. Things like the continuance of British rule in India, the Russian purges and deportations, the dropping of the atom bombs on Japan, can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of political parties. Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenceless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification . Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers . People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: this is called elimination of unreliable elements . Such phraseology is needed if one wants to name things without calling up mental pictures of them. Consider for instance some comfortable English professor defending Russian totalitarianism. He cannot say outright, ‘I believe in killing off your opponents when you can get good results by doing so’. Probably, therefore, he will say something like this:

While freely conceding that the Soviet régime exhibits certain features which the humanitarian may be inclined to deplore, we must, I think, agree that a certain curtailment of the right to political opposition is an unavoidable concomitant of transitional periods, and that the rigours which the Russian people have been called upon to undergo have been amply justified in the sphere of concrete achievement.

The inflated style is itself a kind of euphemism. A mass of Latin words falls upon the facts like soft snow, blurring the outlines and covering up all the details. The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink. In our age there is no such thing as ‘keeping out of politics’. All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred and schizophrenia. When the general atmosphere is bad, language must suffer. I should expect to find – this is a guess which I have not sufficient knowledge to verify – that the German, Russian and Italian languages have all deteriorated in the last ten or fifteen years, as a result of dictatorship.

But if thought corrupts language, language can also corrupt thought. A bad usage can spread by tradition and imitation, even among people who should and do know better. The debased language that I have been discussing is in some ways very convenient. Phrases like a not unjustifiable assumption , leaves much to be desired , would serve no good purpose , a consideration which we should do well to bear in mind , are a continuous temptation, a packet of aspirins always at one’s elbow. Look back through this essay, and for certain you will find that I have again and again committed the very faults I am protesting against. By this morning’s post I have received a pamphlet dealing with conditions in Germany. The author tells me that he ‘felt impelled’ to write it. I open it at random, and here is almost the first sentence that I see: ‘(The Allies) have an opportunity not only of achieving a radical transformation of Germany’s social and political structure in such a way as to avoid a nationalistic reaction in Germany itself, but at the same time of laying the foundations of a co-operative and unified Europe.’ You see, he ‘feels impelled’ to write – feels, presumably, that he has something new to say – and yet his words, like cavalry horses answering the bugle, group themselves automatically into the familiar dreary pattern. This invasion of one’s mind by ready-made phrases ( lay the foundations , achieve a radical transformation ) can only be prevented if one is constantly on guard against them, and every such phrase anaesthetizes a portion of one’s brain.

I said earlier that the decadence of our language is probably curable. Those who deny this would argue, if they produced an argument at all, that language merely reflects existing social conditions, and that we cannot influence its development by any direct tinkering with words and constructions. So far as the general tone or spirit of a language goes, this may be true, but it is not true in detail. Silly words and expressions have often disappeared, not through any evolutionary process but owing to the conscious action of a minority. Two recent examples were explore every avenue and leave no stone unturned , which were killed by the jeers of a few journalists. There is a long list of fly-blown metaphors which could similarly be got rid of if enough people would interest themselves in the job; and it should also be possible to laugh the not un- formation out of existence[3], to reduce the amount of Latin and Greek in the average sentence, to drive out foreign phrases and strayed scientific words, and, in general, to make pretentiousness unfashionable. But all these are minor points. The defence of the English language implies more than this, and perhaps it is best to start by saying what it does not imply.

To begin with it has nothing to do with archaism, with the salvaging of obsolete words and turns of speech, or with the setting up of a ‘standard English’ which must never be departed from. On the contrary, it is especially concerned with the scrapping of every word or idiom which has outworn its usefulness. It has nothing to do with correct grammar and syntax, which are of no importance so long as one makes one’s meaning clear or with the avoidance of Americanisms, or with having what is called a ‘good prose style’. On the other hand it is not concerned with fake simplicity and the attempt to make written English colloquial. Nor does it even imply in every case preferring the Saxon word to the Latin one, though it does imply using the fewest and shortest words that will cover one’s meaning. What is above all needed is to let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way about. In prose, the worst thing one can do with words is to surrender to them. When you think of a concrete object, you think wordlessly, and then, if you want to describe the thing you have been visualising, you probably hunt about till you find the exact words that seem to fit it. When you think of something abstract you are more inclined to use words from the start, and unless you make a conscious effort to prevent it, the existing dialect will come rushing in and do the job for you, at the expense of blurring or even changing your meaning. Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one’s meanings as clear as one can through pictures and sensations. Afterward one can choose – not simply accept – the phrases that will best cover the meaning, and then switch round and decide what impression one’s words are likely to make on another person. This last effort of the mind cuts out all stale or mixed images, all prefabricated phrases, needless repetitions, and humbug and vagueness generally. But one can often be in doubt about the effect of a word or a phrase, and one needs rules that one can rely on when instinct fails. I think the following rules will cover most cases:

i. Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print. ii. Never use a long word where a short one will do. iii. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out. iv. Never use the passive where you can use the active. v. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent. vi. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

These rules sound elementary, and so they are, but they demand a deep change of attitude in anyone who has grown used to writing in the style now fashionable. One could keep all of them and still write bad English, but one could not write the kind of stuff that I quoted in those five specimens at the beginning of this article.

I have not here been considering the literary use of language, but merely language as an instrument for expressing and not for concealing or preventing thought. Stuart Chase and others have come near to claiming that all abstract words are meaningless, and have used this as a pretext for advocating a kind of political quietism. Since you don’t know what Fascism is, how can you struggle against Fascism? One need not swallow such absurdities as this, but one ought to recognize that the present political chaos is connected with the decay of language, and that one can probably bring about some improvement by starting at the verbal end. If you simplify your English, you are freed from the worst follies of orthodoxy. You cannot speak any of the necessary dialects, and when you make a stupid remark its stupidity will be obvious, even to yourself. Political language – and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists – is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind. One cannot change this all in a moment, but one can at least change one’s own habits, and from time to time one can even, if one jeers loudly enough, send some worn-out and useless phrase – some jackboot , Achilles’ heel , hotbed , melting pot , acid test , veritable inferno or other lump of verbal refuse – into the dustbin where it belongs.

Horizon, April 1946

We use cookies. By browsing our site you agree to our use of cookies. Accept

George Orwell: 'In our time political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible.'

In our time political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible.

In our time, political speech and writing often serve as a means to defend that which is indefensible. This powerful quote by George Orwell encapsulates the troubling reality of contemporary politics, where the art of persuasion and rhetoric can be employed to veil the truth and manipulate public opinion. Orwell's words draw attention to the importance of critically analyzing political discourse, as language becomes a battleground upon which politicians fight for power and influence.Upon first glance, Orwell's statement may seem quite straightforward. It suggests that politicians and those in power use their rhetoric skills to justify, excuse, or cover up actions that are morally objectionable or logically flawed. By employing intricate language and persuasive techniques, politicians can effectively twist public perception and maintain their stronghold. The quote reminds us that it is essential to remain vigilant and discerning when engaging with political discourse, as we must not allow ourselves to be swayed by empty promises or misleading arguments.However, to truly delve into the depth of Orwell's quote and bring an unexpected philosophical concept into the discussion, let us explore the notion of linguistic relativity. Proposed by linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf, linguistic relativity suggests that the language we use shapes our perception of reality and influences our thoughts and actions. This concept introduces an intriguing dimension to Orwell's quote, revealing how political speech and writing may not only be the defense of the indefensible, but also the creation of the indefensible.Language serves as a tool for communication, but it also conveys cultural and societal norms, values, and biases. Therefore, the language employed in political discourse not only aims to defend questionable actions, but it also constructs and molds the very concepts and ideas being discussed. For instance, through cleverly crafted language, politicians may redefine terms, distort facts, or manipulate emotions to shape public opinion and mold collective consciousness.By exploring the concept of linguistic relativity, we begin to understand that political speech and writing are not mere defenses of the indefensible but also active agents that contribute to the very existence of the indefensible. Politicians skillfully utilize language to create an alternate reality, where their actions seem justifiable or even virtuous to their supporters. This manipulation of language occurs on both conscious and subconscious levels as politicians tap into deep-rooted beliefs and biases to strengthen their narratives.To comprehend the gravity of Orwell's quote and the role of political discourse, we need to recognize the power imbalances in society. Those in positions of authority possess the ability to shape and control language, reinforcing their influence by subtly reshaping reality itself. This manipulation further exacerbates existing societal divisions, as certain ideologies and perspectives are legitimized while others are relentlessly marginalized.In this climate, it is crucial for individuals to develop a critical mindset and hone their ability to decipher truth amidst a sea of persuasive language and rhetoric. By scrutinizing political speech and writing, we can resist being swayed solely by the form and eloquence of language and instead focus on the substance of arguments and the factual foundation upon which they are built.Ultimately, Orwell's quote serves as a timely reminder to remain skeptical, discerning, and vigilant when engaging with political discourse. By acknowledging the potential for language to be used both defensively and offensively, we can strive towards a society where the indefensible is not only recognized but actively confronted.

George Orwell: 'Enlightened people seldom or never possess a sense of responsibility.'

George orwell: 'one cannot really be a catholic and grown up.'.

Index Index

- Other Authors :

Breaking News

Orwell’s 5 greatest essays: No. 1, ‘Politics and the English Language’

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

For anyone interested in the politics of left and right -- and in political journalism as it is practiced at the highest level -- George Orwell’s works are indispensable. This week, in the year marking the 110th anniversary of his birth, we present a personal list of his five greatest essays.

The winner and still champ, Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language” stands as the finest deconstruction of slovenly writing since Mark Twain’s “ Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses .”

Orwell’s essay, published in 1946 in Cyril Connolly’s literary review Horizon, is not as sarcastic or funny as Twain’s, but unlike Twain, Orwell makes the connection between degraded language and political deceit (at both ends of the political spectrum).

“The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable,’ he writes, then points a finger at words like democracy, socialism, freedom, patriotic, realistic and justice.

“Words of this kind are often used in a consciously dishonest way.... Statements like Marshal Pétain was a true patriot, The Soviet press is the freest in the world, The Catholic Church is opposed to persecution, are almost always made with intent to deceive. Other words used in variable meanings, in most cases more or less dishonestly, are: class, totalitarian, science, progressive, reactionary, bourgeois, equality.”

Orwell continues: “In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible....Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness.” In our time, too.

He observes: “Political language -- and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists -- is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” The remedy is to insist on simple English.

“If you simplify your English, you are freed from the worst follies of orthodoxy ... and when you make a stupid remark its stupidity will be obvious, even to yourself.”

More to Read

MSNBC host Katy Tur’s chaotic childhood began in an L.A. news helicopter

June 14, 2022

The 50 best Hollywood books of all time

April 8, 2024

Is Madonna a game-changing feminist or capitalist come-on? A biography hashes it out

Oct. 5, 2023

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Michael Hiltzik has written for the Los Angeles Times for more than 40 years. His business column appears in print every Sunday and Wednesday, and occasionally on other days. Hiltzik and colleague Chuck Philips shared the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for articles exposing corruption in the entertainment industry. His seventh book, “Iron Empires: Robber Barons, Railroads, and the Making of Modern America,” was published in 2020. His forthcoming book, “The Golden State,” is a history of California. Follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/hiltzikm and on Facebook at facebook.com/hiltzik.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Valentina, Justin Torres and more on the Latinidad Stage at the L.A. Times Festival of Books

April 10, 2024

The week’s bestselling books, April 14

Why Pauline Kael’s fight over ‘Citizen Kane’ still matters, whichever side you’re on

Hollywood’s bravest and most foolhardy memoir wasn’t written by a movie star

Classic George Orwell Quotes

Thoughts on Religion, War, Politics, and More

- Love Quotes

- Great Lines from Movies and Television

- Quotations For Holidays

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- M.A., English Literature, California State University - Sacramento

- B.A., English, California State University - Sacramento

George Orwell is one of the most famous writers of his time. He is perhaps best known for his controversial novel , 1984 , a dystopian tale in which language and truth are corrupted. He also wrote Animal Farm , an anti-Soviet fable where the animals revolt against the humans.

A great writer and a true master of words, Orwell is also known for some smart sayings. While you might already know his novels, here is a collection of quotes by the author that you should also know.

Ranging from grave to ironic, from dark to optimistic, these George Orwel l quotes give a sense of his ideas on religion, war, politics, writing, corporations, and society at large. By understanding Orwell's opinions, perhaps readers will be able to better read his works.

"Freedom is the right to tell people what they do not want to hear."

"I sometimes think that the price of liberty is not so much eternal vigilance as eternal dirt."

Talking Politics

"In our time political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible. "

"In our age, there is no such thing as 'keeping out of politics.' All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred and schizophrenia."

"In times of universal deceit, telling the truth becomes a revolutionary act."

"A dirty joke is a sort of mental rebellion."

"As I write, highly civilized human beings are flying overhead, trying to kill me."

"War is a way of shattering to pieces... materials which might otherwise be used to make the masses too comfortable and... too intelligent."

"A tragic situation exists precisely when virtue does not triumph but when it is still felt that man is nobler than the forces which destroy him."

On Advertisements

"Advertising is the rattling of a stick inside a swill bucket."

Foodie Talk

"We may find in the long run that tinned food is a deadlier weapon than the machine-gun."

On Religion

"Mankind is not likely to salvage civilization unless he can evolve a system of good and evil which is independent of heaven and hell."

Other Wise Advice

"Most people get a fair amount of fun out of their lives, but on balance life is suffering, and only the very young or the very foolish imagine otherwise."

"Myths which are believed in tend to become true."

"Progress is not an illusion, it happens, but it is slow and invariably disappointing."

- "Who Controls the Past Controls the Future" Quote Meaning

- George Orwell: Novelist, Essayist and Critic

- '1984' Questions for Study and Discussion

- '1984' Study Guide

- 'Animal Farm' Quotes

- Plain Style in Prose

- Reading Quiz on "A Hanging" by George Orwell

- 'Animal Farm' Overview

- A Critical Analysis of George Orwell's 'A Hanging'

- 'Animal Farm' Questions for Study and Discussion

- What Is Newspeak?

- What Is Doublespeak?

- 10 Classic Novels for Teens

- The Best Books on the Spanish Civil War

- 'Down and Out in Paris and London' Study Guide

- '1984' Quotes Explained

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

Edited by: Susan Ratcliffe

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

In this work.

- International Relations

- Political Parties

- Politicians

- Publishing Information

- How to use this work

- Previous Version

- Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, has always been the systematic organization of hatreds. Henry Brooks Adams 1838–1918 American historian: The Education of Henry Adams (1907) ch. 1

- I agree with you that in politics the middle way is none at all. John Adams 1735–1826 American Federalist statesman, 2nd President 1797–1801: letter to Horatio Gates, 23 March 1776

- Not to be a republican at twenty is proof of want of heart; to be one at thirty is proof of want of head. often used in the form ‘Not to be a socialist…’ Anonymous : adopted by Clemenceau , and attributed by him to François Guizot (1787–1874)

- Therefore, the good of man must be the end [i.e. objective] of the science of politics. Aristotle 384–322 bc Greek philosopher: Nicomachean Ethics bk. 1, 1094b 6–7

- Man is by nature a political animal. Aristotle 384–322 bc Greek philosopher: Politics bk. 1, 1253a 2–3

- Politics is the art of looking for trouble, finding it everywhere, diagnosing it wrongly and applying unsuitable remedies. Ernest Benn 1875–1954 English publisher: attributed, Powell Spring What Is Truth (1944); often later associated with the American film comedian Groucho Marx (1890–1977)

- Politics is the art of the possible. Otto von Bismarck 1815–98 German statesman: in conversation with Meyer von Waldeck, 11 August 1867; see Butler, Galbraith, Medawar

- A statesman…must wait until he hears the steps of God sounding through events; then leap up and grasp the hem of his garment. Otto von Bismarck 1815–98 German statesman: A. J. P. Taylor Bismarck (1955)

- The liberals can understand everything but people who don't understand them. Lenny Bruce 1925–66 American comedian: John Cohen (ed.) The Essential Lenny Bruce (1967)

- In politics, there is no use looking beyond the next fortnight. Joseph Chamberlain 1836–1914 British Liberal politician: letter from A. J. Balfour to 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, 24 March 1886; A. J. Balfour Chapters of Autobiography (1930) ch. 16; see Wilson

- The art of politics is learning to walk with your back to the wall, your elbows high, and a smile on your face. It's a survival game played under the glare of lights. Jean Chrétien 1934– Canadian Liberal statesman: Straight from the Heart (1985)

- Politics are almost as exciting as war and quite as dangerous. In war you can only be killed once, but in politics—many times. Winston Churchill 1874–1965 British Conservative statesman, Prime Minister 1940–5, 1951–5: attributed

- International life is right-wing, like nature. The social contract is left-wing, like humanity. Régis Debray 1940– French Marxist theorist: Charles de Gaulle (1994)

- Politics are too serious a matter to be left to the politicians. replying to Attlee 's remark that ‘De Gaulle is a very good soldier and a very bad politician’ Charles de Gaulle 1890–1970 French soldier and statesman, President of France 1959–69: Clement Attlee A Prime Minister Remembers (1961) ch. 4; see Clemenceau

- Finality is not the language of politics. Benjamin Disraeli 1804–81 British Tory statesman and novelist; Prime Minister 1868, 1874–80: speech, House of Commons, 28 February 1859

- ‘Two nations; between whom there is no intercourse and no sympathy; who are as ignorant of each other's habits, thoughts, and feelings, as if they were dwellers in different zones, or inhabitants of different planets; who are formed by a different breeding, are fed by a different food, are ordered by different manners, and are not governed by the same laws.’ ‘You speak of—’ said Egremont, hesitatingly, ‘ the rich and the poor. ’ Benjamin Disraeli 1804–81 British Tory statesman and novelist; Prime Minister 1868, 1874–80: Sybil (1845) bk. 2, ch. 5; see Foster

- There is an invisible hand in politics that operates in the opposite direction to the invisible hand in the market. In politics, individuals who seek to promote only the public good are led by an invisible hand to promote special interests that it was no part of their intention to promote. Milton Friedman 1912–2006 American economist: Bright Promises, Dismal Performance: An Economist's Protest (1983); see Smith

- I never dared be radical when young For fear it would make me conservative when old. Robert Frost 1874–1963 American poet: ‘Precaution’ (1936)

- Politics is not the art of the possible. It consists in choosing between the disastrous and the unpalatable. J. K. Galbraith 1908–2006 Canadian-born American economist: speech to President Kennedy, 2 March 1962; see Bismarck

- The job of a citizen is to keep his mouth open. Günter Grass 1927–2015 German novelist, poet, and dramatist: slogan coined in 1965, Terence Prittie Willie Brandt: portrait of a statesman (1974)

- The personal is political. Carol Hanisch 1945– American feminist: 1970s feminist slogan

- Healey's first law of politics: when you're in a hole, stop digging. Denis Healey 1917–2015 British Labour politician: attributed

- Who? Whom? definition of political science, meaning ‘Who will outstrip whom?’ Lenin 1870–1924 Russian revolutionary: in Polnoe Sobranie Sochinenii vol. 44 (1970) 17 October 1921 and elsewhere

- Politics is a marathon, not a sprint. Ken Livingstone 1945– British Labour politician: in New Statesman 10 October 1997

- He who wishes to see what is to come should observe what has already happened, because all the affairs of the world, in every age, have their individual counterparts in ancient times. Niccolò Machiavelli 1469–1527 Italian political philosopher and Florentine statesman: Discourse upon the First Ten Books of Livy (written 1513–17) bk. 3, ch. 43 (tr. Allan Gilbert)

- The opposition of events. on his biggest problem; popularly quoted as, ‘Events, dear boy. Events’ Harold Macmillan 1894–1986 British Conservative statesman; Prime Minister, 1957–63: David Dilks The Office of Prime Minister in Twentieth Century Britain (1993)

- Politics is war without bloodshed while war is politics with bloodshed. Mao Zedong 1893–1976 Chinese statesman; de facto leader of the Communist Party: lecture, 1938

- All reactionaries are paper tigers. In appearance, the reactionaries are terrifying, but in reality they are not so powerful. From a long-term point of view, it is not the reactionaries but the people who are really powerful. Mao Zedong 1893–1976 Chinese statesman; de facto leader of the Communist Party: interview with Anne Louise Strong, August 1946

- Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world. In fact, it's the only thing that ever has. Margaret Mead 1901–78 American anthropologist: attributed; Mary Bowman-Kruhm Margaret Mead: a biography (2003)

- In the area of politics our major policy obligation is not to mistake slogans for solutions. Ed Murrow 1908–65 American broadcaster and journalist: broadcast, 3 April 1951

- In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible. George Orwell 1903–50 English novelist: Shooting an Elephant (1950) ‘Politics and the English Language’

- Political language…is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind. George Orwell 1903–50 English novelist: Shooting an Elephant (1950) ‘Politics and the English Language’

- Men enter local politics solely as a result of being unhappily married. C. Northcote Parkinson 1909–93 English writer: Parkinson's Law (1958)

- Politics is supposed to be the second oldest profession. I have come to realize that it bears a very close resemblance to the first. Ronald Reagan 1911–2004 American Republican statesman; 40th President 1981–9: at a conference in Los Angeles, 2 March 1977

- What is morally wrong cannot be politically right. Donald Soper 1903–98 British Methodist minister: speech, House of Lords, 1966

- A week is a long time in politics. probably first said at the time of the 1964 sterling crisis Harold Wilson 1916–95 British Labour statesman, Prime Minister 1964–70, 1974–6: Nigel Rees Sayings of the Century (1984); see Chamberlain

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 11 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.174]

- 81.177.182.174

Character limit 500 /500

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

George Orwell, human resources and the English language

The HR industry misuses language as a sort of low-tech mind control to avert our eyes from office atrocities and keep us fixed on our inboxes

In our age there is no such thing as ‘keeping out of human resources’. All issues are human resource issues, and human resources itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred and schizophrenia.

OK, that’s not exactly what Orwell wrote. The hair-splitters among you will moan that I’ve taken the word “politics” out of the above and replaced it with “human resources”. Sorry.

But I think there’s no denying that had he been alive today, Orwell – the great opponent and satirist of totalitarianism – would have deplored the bureaucratic repression of HR. He would have hated their blind loyalty to power, their unquestioning faithfulness to process, their abhorrence of anything or anyone deviating from the mean.

In particular, Orwell would have utterly despised the language that HR people use. In his excellent essay Politics and the English Language (where he began the thought that ended with Newspeak), Orwell railed against the language crimes committed by politicians.

In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible … Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenceless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification. Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers. People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: this is called elimination of unreliable elements.

Repeat the politics/human resources switch in the above and the argument remains broadly the same. Yes, HR is not explaining away murders, but it nonetheless deliberately misuse language as a sort of low-tech mind control to avert our eyes from office atrocities and keep us fixed on our inboxes. Thus mass sackings are wrapped up in cowardly sophistry and called rightsizings , individuals are offboarded to the jobcentre and the few hardy souls left are consoled by their membership of a more streamlined organisation.

Orwell would have despised the passive constructions that are the HR department’s default setting. Want some flexibility in your contract? HR says company policy is unable to support that . Forgotten to accede to some arbitrary and impractical office rule? HR says we are minded to ask everyone to remember that it is essential to comply by rule X . Try to question whether an ill-judged commitment could be reversed? HR apologises meekly that the decision has been made.

Not giving subjects to any of these responses is a deliberate ploy. Subjects give ownership. They imbue accountability. Not giving sentences subjects means that HR is passing the buck, but to no one in particular. And with no subject, no one can be blamed, or protested against.

The passive construction is also designed to give the sense that it’s not HR speaking, but that they are the conduit for a higher-up and incontestable power. It’s designed to be both authoritative and banal, so that we torpidly accept it, like the sovereignty of the Queen. It’s saying: “This is the way things are – deal with it because it isn’t changing.” It’s indifferent and deliberately opaque. It’s the worst kind of utopianism (the kind David Graeber targets in his recent book on “stupidity and the secret joys of bureaucracy”), where system and rule are king and hang the individual. It’s deeply, deeply oppressive.

Annual leave is perhaps an even worse example of HR’s linguistic malpractice. The phrase gives the sense that we are not sitting in the office but rather fighting some dismal war and that we should be grateful for the mercy of Field Marshal HR in allowing us a finite absence from the front line. Is it too indulgent and too frivolous to say that we are going on holiday (even if we’re just taking the day to go to Ikea)? Would it so damage our career prospects? Would the emerging markets of the world be emboldened by the decadence and complacency of saying we’re going on hols? I don’t think so, but they clearly do.

Actually, I don’t think it’s so much of a stretch to imagine Orwell himself establishing the whole HR enterprise as a sort of grim parody of Stalinism; a never-ending, ever-expanding live action art installation sequel to Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Look at your office’s internal newsletter. Is it an incomprehensible black hole of sense? Is it trying to prod you into a place of content, incognisant of all the everyday hardships and irritations you endure? If your answer is yes, then I think that like me, you find it fairly easy to imagine Orwell composing these Newspeak emails from beyond the grave to make us believe that War is Peace, Freedom is Slavery and 2+2=5.

Delving deeper, the parallels become increasingly hard to ignore. Company restructures and key performance indicators make no sense in the abstract, merely serving to demotivate the workforce, sap confidence and obstruct productivity. So are they actually cleverly designed parodies of Stalin’s purges and the cult of Stakhanovism?

Could the industry’s name itself – human resources – be an Orwellian slight? A wink-wink label designed to conjure up images of the pigs of Animal Farm harvesting the life force of their lackeys? I’m only half joking.

If all this is depressing, then it’s not meant to be. Orwell’s essay was meant positively: he wanted us to believe that better writing and better use of language can result in a better society.

The point is that the process is reversible. Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble. If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration.

And while it might be hard to persuade our politicians to part with their mendacious tongues, I think it’s achievable in the workplace. We can have recourse from human resources – but they first need to mind their language.

Twitter: @jamesgingell1

- Mind your language

- George Orwell

Most viewed

- No products in the cart.

- All Categories

- Uncategorized

- Collections

- Trinity Forum Readings

- Christmas Readings

Politics and the English Language: An Introduction

Below is an excerpt from EPPC Senior Fellow Peter Wehner’s introduction to a forthcoming edition of George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language,” to be published soon by The Trinity Forum. Readers may order a copy of the Trinity Forum reading here .

Orwell’s Most Enduring Essay

“Politics and the English Language,” published in 1946 in the journal Horizon , is considered by many to be Orwell’s most famous and enduring essay. In it, he argues the English language has become degraded, “ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.” Language, and particularly political language, he argued, is not just a manifestation of our decline but also an instrument in it.

Orwell examines five passages — two from professors (Harold Laski and Lancelot Hogben), one from a Communist pamphlet, one from an essay on psychology, and one from a letter to a newspaper — not because they are particularly bad but because they are representative, illustrating “various of the mental vices from which we now suffer.” The common qualities, he writes, are staleness of imagery and lack of precision. Orwell offers a “catalogue of swindles and perversions” that get in the way of modern prose: “dying metaphors,” “operators or verbal false limbs,” “pretentious diction,” and “meaningless words.” He then offers the following six rules as a corrective:

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

There are exceptions to these rules, and many of the words (like ameliorate, clandestine, eliminate ) and phrases (like acid test, radical transformation, cul de sac ) Orwell dislikes or even detests strike me as perfectly fine and often appropriate. As Geoffrey Pullum, writing in The Chronicle of Higher Education , put it: “This miscellany of locutions has nothing in common other than that Orwell hated them and (without quantitative support) thought that they were overly frequent in 1946.” Even so incisive a writer as Orwell had his literary quirks.

As a general matter, however, Orwell offers sound advice. The important thing to understand is that what Orwell is aiming for is clarity . He wanted language to be an instrument to express and sharpen, rather than conceal or prevent thought, and he was quite right about that.

Orwell’s thoughts on political language merit particular attention. “In our time,” he wrote, “political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible.” Political language consists largely of “euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness.” And this: “Political language — and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists — is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” This can’t be done in a moment, according to Orwell, but we can change our habits and send some worn-out and useless phrase “into the dustbin where it belongs.”

One senses in Orwell his frustration with the state of much political speech because it often degrades what he considers precious — clear, precise, and appropriate language. He understood the enormous stakes in politics and believed political speech often disfigures reality and the true nature of things. If we get our politics wrong, Orwell knew, it can lead to misery and suffering, to gulags and concentration camps. “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written directly or indirectly against totalitarianism,” he said, “and for Democratic Socialism as I understand it.”

Political language matters because politics matter. The corruption of one leads to the corruption of the other.

In the Beginning Was the Word

The care of words is something that should concern all of us, perhaps particularly those of the Christian faith. After all, in the gospel of John we are told, “In the beginning was the Word.”

In reflecting on this sentence in 1978, Malcolm Muggeridge, a friend of Orwell’s — Muggeridge arranged Orwell’s memorial service — said:

one of the things that appalls me and saddens me about the world today is the condition of words. Words can be polluted even more dramatically and drastically than rivers and land and sea. There has been a terrible destruction of words in our time… Jesus himself said that heaven and earth would pass away, but his words would not pass away. I believe that is true, and I think that our most sacred treasure today is the word of the Gospels, which we should guard at all costs, for it is most precious.

Muggeridge then told this story:

I was in Darwin, Australia, and I got a message that there was a man in a hospital there who had listened to something that I had said on the radio, and had expressed a wish that I should visit him. So I did. He turned out to be an old, wizened man who had lived in the bush and who was blind. I can never forget him. Wanting to think of something to say to him that would light him up and cheer him up, I suddenly remembered a phrase in the play King Lear . You may remember that Gloucester, commiserating with Lear on being blind, uses five words. I remembered them then: “I stumbled when I saw.” I said this to the old man in the Darwin hospital. He was utterly enchanted. He got the point immediately. As I left the ward, I could hear him saying them over and over to himself: “I stumbled when I saw.” That is what I mean by the marvelous power of words when they are used with true force in their true meaning.

Unlike Muggeridge, George Orwell never became a Christian; it was politics, not faith, that occupied Orwell’s energy and attention and gave urgency to his work. But he was a man who believed in a moral code, in concepts like justice, freedom, and objective truth, and he worked valiantly throughout his life to articulate and further them. “The Party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command,” Orwell wrote in Nineteen Eighty-Four . His heroes were those who defied the lies of an oppressive power, who discerned, spoke, and held to what was true:

[Winston Smith’s] heart sank as he thought of the enormous power arrayed against him, the ease with which any Party intellectual would overthrow him in debate, the subtle arguments which he would not be able to understand, much less answer. And yet he was in the right! They were wrong and he was right. The obvious, the silly, and the true had got to be defended. Truisms are true, hold on to that! The solid world exists, its laws do not change. Stones are hard, water is wet, objects unsupported fall towards the earth’s centre. With the feeling that he was speaking to O’Brien, and also that he was setting forth an important axiom, he wrote: Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four. If that is granted, all else follows.

While Orwell didn’t locate the basis of his beliefs in the enduring truth of the Christian faith, he did concede that Christian thinkers were right to believe “that if our civilisation does not regenerate itself, it is likely to perish — and they may be right in adding that, at least in Europe, its moral code must be based on Christian principles.”

Orwell believed throughout his life that language was a means to see the truth and to tell the truth. But for those of us of the Christian faith, words show not only what is true, but are the primary vehicle for knowing the Author of all Truth; the “all else follows” eventually leads us to Christ, and the Cross, and what follows from the Cross.

In the gospel of John we are told that Jesus said to those who had believed Him, “If you abide in My word, you are truly My disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.”

George Orwell’s affection and allegiance were ultimately found in places other than the person of Jesus. But the concept of there being (to paraphrase the 17th century English Bishop Joseph Hall) a silken string running through the pearl chain of words, truth, and freedom is one I like to think that Orwell would have appreciated.

Peter Wehner , a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, served in the last three Republican administrations and is a New York Times contributing opinion writer.

Comments are closed.

Username or email address *

Remember me Lost your password?

- The Inventory

Support Quartz

Fund next-gen business journalism with $10 a month

Free Newsletters

You probably didn’t read the most telling part of Orwell’s “1984”—the appendix

If there is any doubt about the persistent power of literature in the face of digital culture, it should be banished by the recent climb of George Orwell’s 1984 up the Amazon “Movers & Shakers” list. There is much that’s resonant for us in Orwell’s dystopia in the face of Edward Snowden’s revelations about the NSA: the totalitarian State of Oceania, its sinister Big Brother, always watching, the history-erasing Ministry of Truth, and the menacing Thought Police, with their omnipresent telescreens. All this may seem to be the endgame of indiscriminate data mining, surveillance, and duplicitous government control. We look to 1984 as a clear cautionary tale, even a prophecy, of systematic abuse of power taken to the end of the line. However, the notion that the novel concludes with a brainwashed, broken protagonist, Winston Smith, weeping into his Victory Gin and the bitter sentence: “He loved Big Brother,” are not exactly right. Big Brother does not actually get the last word.

After “THE END,” Orwell includes another chapter, an appendix, called “The Principles of Newspeak.” Since it has the trappings of a tedious scholarly treatise, readers often skip the appendix. But it changes our whole understanding of the novel. Written from some unspecified point in the future, it suggests that Big Brother was eventually defeated. The victory is attributed not to individual rebels or to The Brotherhood, an anonymous resistance group, but rather to language itself. The appendix details Oceania’s attempt to replace Oldspeak, or English, with Newspeak, a linguistic shorthand that reduces the world of ideas to a set of simple, stark words. “The whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought.” It will render dissent “literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it.”

But it never comes to pass. The Party’s plans—the abolition of the family, laughter, art, literature, curiosity, pleasure, in favor of a “boot stamping down on a human face forever”—are never achieved because Newspeak fails to take. Why? Because it was too difficult to translate Oldspeak literature into Newspeak. The text Orwell singles out to exemplify this, intriguingly, is the Declaration of Independence. The “author” of the appendix argues that these ideas cannot be expressed in Newspeak, specifically the part about governments deriving their legitimacy from the consent of the people, and citizens having the right to challenge any government that fails to honor the contract. As long as we have a nuanced, expansive system of language, Orwell claims, we will have freedom and the possibility of dissent.

This appeal to the integrity of language and principled thought may sound utopic or academic, but we are currently in the midst of a similar struggle. Consider the names of the post-9/11 programs that were ostensibly designed to protect the United States: the Patriot Act, Boundless Informant, and practices like “enhanced interrogation techniques.” The justifications of these 1984 -sounding schemes—and PRISM too—follow the obfuscating principles of Newspeak and the kind of manipulative euphemism Orwell skewers in his famous essay, “Politics and the English Language.” He writes: “Political language—and with variations this is true of all political parties, from Conservatives to Anarchists—is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” Orwell maintains that misleading terminology and evasive explanations are endemic to modern politics. “In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible,” including practices like imprisoning people “for years without trial,“ Orwell writes.

If the main story of 1984 is language and freedom of thought, a crucial part of the Snowden case is technology as a conduit of ideas. In Orwell’s novel, technology is a purely oppressive force, but in reality it can also be a means of liberation. Snowden has claimed that tech companies are in collusion with the government, but he’s also using those same channels of technology to tell his story. Daniel Ellsberg had to photocopy the Pentagon Papers and distribute them in hard copies; now our language of dissent includes emails, tweets, and IMs.

It’s worth recalling Apple’s famous ad that unveiled the Macintosh computer to the world in 1984 , making full use of the reference to Orwell’s novel. A mass of worker drones trudges toward a screen showing a bespectacled leader proclaiming that, “We have created, for the first time in all history, a garden of pure ideology—where each worker may bloom, secure from the pests purveying contradictory truths.” Suddenly, an athletic woman, in glorious technicolor, emerges with a hammer, the police in pursuit. She hurls the weapon at the screen and smashes the image. “On January 24th,” the screen tells us, “Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you’ll see why 1984 won’t be like ‘1984.’” Apple’s Board of Directors tried to block the ad, but Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak pushed it through.

This is contemporary technology’s founding myth: the garage band ethos of its early founders going up against centralized, bureaucratic cultures like IBM by putting technology into the hands of the people. Obviously, scrappy startups have grown into multinational corporations led by wealthy CEOs, and most successful social networks are now run by powerful companies. However, we are surrounded by examples of technology used to question the status quo: Twitter and the Arab Spring is one example, Wikileaks is another, and so is Snowden.

When Orwell wrote 1984 , he was responding to the Cold War, not contemporary terrorism. He did not anticipate the full reach of digital technology. Even so, he was correct in seeing a future where the government had greater control but also a belief in the people’s ability to use language for dissent.

📬 Sign up for the Daily Brief

Our free, fast, and fun briefing on the global economy, delivered every weekday morning.

Jump to navigation

- Why Donate?

The Defence Of The Indefensible

Submitted by Laura Miller on February 11, 2003 - 5:45pm

"In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible. ... Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness, " George Orwell wrote fifty-five years ago in his essay "Politics and the English Language." In this month's Ecologist, Paul Kingsnorth points out the relevance of Orwell's words today. "An entire political culture has been built on one delightfully simple premise: to get away with doing something downright evil, it's not necessary to change your behaviour, it's just necessary to change the language you use to describe it," Kingsnorth writes. He gives the example of the Bush administration phrase "pre-emptive defence." According to Kingsnorth, this means "attacking anyone we want to and justifying it by saying that they might attack us one day."

- Get Breaking News

- Press Inquiries

- Press Releases

- Arn Pearson

- David Armiak

- Lisa Graves

- ExposedbyCMD

- ALECexposed

- ALEC Exposed

- Koch Exposed

- Outsourcing America Exposed

- State Policy Network

- Toxic Sludge

- Wage Crushers

- BanksterUSA

- Defend the Press

- Food Rights Network

- The Best War Ever

- Banana Republicans

- Weapons of Mass Deception

- Trust Us, We're Experts

- Mad Cow USA

- Toxic Sludge Is Good For You

- Fake TV News

- Still Not the News

- Know Fake News

- Guest Contributor

- Press Release

- Special Report

- Take Action

- Fix the Debt

- KOCHexposed

- NFIBexposed

- Privatization/ Outsourcing

- SourceWatch

- Campaign Finance

- Corporations

- Environment

- Public Relations

Center for Media and Democracy (CMD) 520 University Ave, Ste 305 • Madison, WI 53703 • (608) 260-9713 CMD is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt non-profit. © 1993-2024

What Would Orwell Make of Obama's Drone Policy?

A recently released memo yields a few good examples of double-talk. It also leaves it up to the president to decide how to interpret them.

In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible. Things like the continuance of British rule in India, the Russian purges and deportations, the dropping of the atom bombs on Japan, can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of the political parties. Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenseless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification. Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers. People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: this is called elimination of unreliable elements.