This document originally came from the Journal of Mammalogy courtesy of Dr. Ronald Barry, a former editor of the journal.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Yale J Biol Med

- v.84(3); 2011 Sep

Focus: Education — Career Advice

How to write your first research paper.

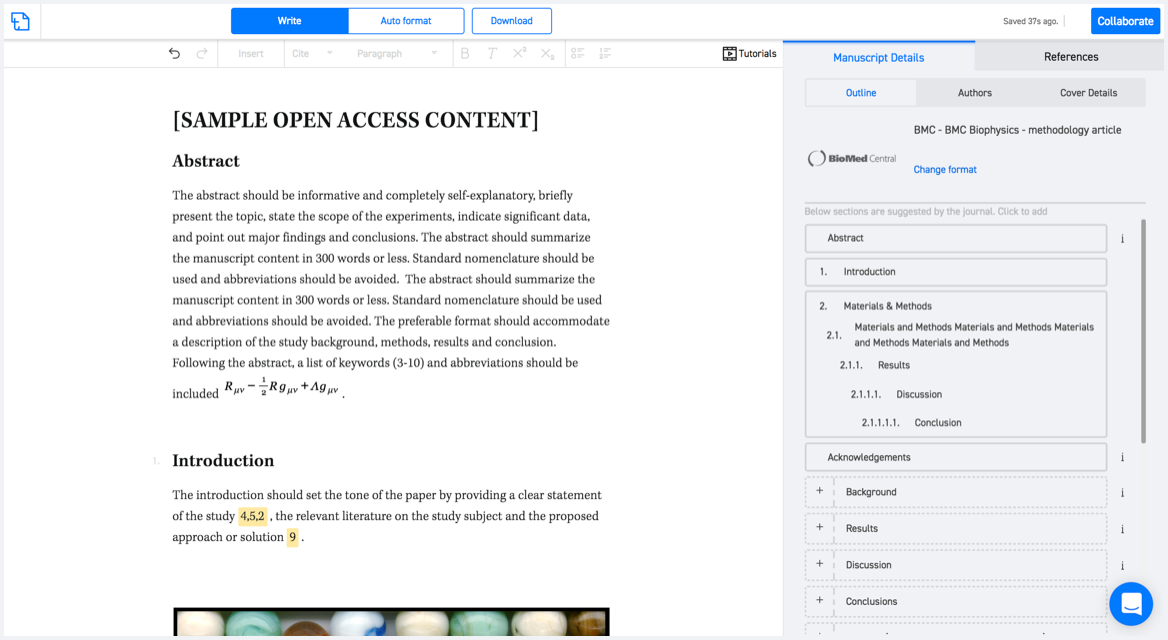

Writing a research manuscript is an intimidating process for many novice writers in the sciences. One of the stumbling blocks is the beginning of the process and creating the first draft. This paper presents guidelines on how to initiate the writing process and draft each section of a research manuscript. The paper discusses seven rules that allow the writer to prepare a well-structured and comprehensive manuscript for a publication submission. In addition, the author lists different strategies for successful revision. Each of those strategies represents a step in the revision process and should help the writer improve the quality of the manuscript. The paper could be considered a brief manual for publication.

It is late at night. You have been struggling with your project for a year. You generated an enormous amount of interesting data. Your pipette feels like an extension of your hand, and running western blots has become part of your daily routine, similar to brushing your teeth. Your colleagues think you are ready to write a paper, and your lab mates tease you about your “slow” writing progress. Yet days pass, and you cannot force yourself to sit down to write. You have not written anything for a while (lab reports do not count), and you feel you have lost your stamina. How does the writing process work? How can you fit your writing into a daily schedule packed with experiments? What section should you start with? What distinguishes a good research paper from a bad one? How should you revise your paper? These and many other questions buzz in your head and keep you stressed. As a result, you procrastinate. In this paper, I will discuss the issues related to the writing process of a scientific paper. Specifically, I will focus on the best approaches to start a scientific paper, tips for writing each section, and the best revision strategies.

1. Schedule your writing time in Outlook

Whether you have written 100 papers or you are struggling with your first, starting the process is the most difficult part unless you have a rigid writing schedule. Writing is hard. It is a very difficult process of intense concentration and brain work. As stated in Hayes’ framework for the study of writing: “It is a generative activity requiring motivation, and it is an intellectual activity requiring cognitive processes and memory” [ 1 ]. In his book How to Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing , Paul Silvia says that for some, “it’s easier to embalm the dead than to write an article about it” [ 2 ]. Just as with any type of hard work, you will not succeed unless you practice regularly. If you have not done physical exercises for a year, only regular workouts can get you into good shape again. The same kind of regular exercises, or I call them “writing sessions,” are required to be a productive author. Choose from 1- to 2-hour blocks in your daily work schedule and consider them as non-cancellable appointments. When figuring out which blocks of time will be set for writing, you should select the time that works best for this type of work. For many people, mornings are more productive. One Yale University graduate student spent a semester writing from 8 a.m. to 9 a.m. when her lab was empty. At the end of the semester, she was amazed at how much she accomplished without even interrupting her regular lab hours. In addition, doing the hardest task first thing in the morning contributes to the sense of accomplishment during the rest of the day. This positive feeling spills over into our work and life and has a very positive effect on our overall attitude.

Rule 1: Create regular time blocks for writing as appointments in your calendar and keep these appointments.

2. start with an outline.

Now that you have scheduled time, you need to decide how to start writing. The best strategy is to start with an outline. This will not be an outline that you are used to, with Roman numerals for each section and neat parallel listing of topic sentences and supporting points. This outline will be similar to a template for your paper. Initially, the outline will form a structure for your paper; it will help generate ideas and formulate hypotheses. Following the advice of George M. Whitesides, “. . . start with a blank piece of paper, and write down, in any order, all important ideas that occur to you concerning the paper” [ 3 ]. Use Table 1 as a starting point for your outline. Include your visuals (figures, tables, formulas, equations, and algorithms), and list your findings. These will constitute the first level of your outline, which will eventually expand as you elaborate.

The next stage is to add context and structure. Here you will group all your ideas into sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion/Conclusion ( Table 2 ). This step will help add coherence to your work and sift your ideas.

Now that you have expanded your outline, you are ready for the next step: discussing the ideas for your paper with your colleagues and mentor. Many universities have a writing center where graduate students can schedule individual consultations and receive assistance with their paper drafts. Getting feedback during early stages of your draft can save a lot of time. Talking through ideas allows people to conceptualize and organize thoughts to find their direction without wasting time on unnecessary writing. Outlining is the most effective way of communicating your ideas and exchanging thoughts. Moreover, it is also the best stage to decide to which publication you will submit the paper. Many people come up with three choices and discuss them with their mentors and colleagues. Having a list of journal priorities can help you quickly resubmit your paper if your paper is rejected.

Rule 2: Create a detailed outline and discuss it with your mentor and peers.

3. continue with drafts.

After you get enough feedback and decide on the journal you will submit to, the process of real writing begins. Copy your outline into a separate file and expand on each of the points, adding data and elaborating on the details. When you create the first draft, do not succumb to the temptation of editing. Do not slow down to choose a better word or better phrase; do not halt to improve your sentence structure. Pour your ideas into the paper and leave revision and editing for later. As Paul Silvia explains, “Revising while you generate text is like drinking decaffeinated coffee in the early morning: noble idea, wrong time” [ 2 ].

Many students complain that they are not productive writers because they experience writer’s block. Staring at an empty screen is frustrating, but your screen is not really empty: You have a template of your article, and all you need to do is fill in the blanks. Indeed, writer’s block is a logical fallacy for a scientist ― it is just an excuse to procrastinate. When scientists start writing a research paper, they already have their files with data, lab notes with materials and experimental designs, some visuals, and tables with results. All they need to do is scrutinize these pieces and put them together into a comprehensive paper.

3.1. Starting with Materials and Methods

If you still struggle with starting a paper, then write the Materials and Methods section first. Since you have all your notes, it should not be problematic for you to describe the experimental design and procedures. Your most important goal in this section is to be as explicit as possible by providing enough detail and references. In the end, the purpose of this section is to allow other researchers to evaluate and repeat your work. So do not run into the same problems as the writers of the sentences in (1):

1a. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation. 1b. To isolate T cells, lymph nodes were collected.

As you can see, crucial pieces of information are missing: the speed of centrifuging your bacteria, the time, and the temperature in (1a); the source of lymph nodes for collection in (b). The sentences can be improved when information is added, as in (2a) and (2b), respectfully:

2a. Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation at 3000g for 15 min at 25°C. 2b. To isolate T cells, mediastinal and mesenteric lymph nodes from Balb/c mice were collected at day 7 after immunization with ovabumin.

If your method has previously been published and is well-known, then you should provide only the literature reference, as in (3a). If your method is unpublished, then you need to make sure you provide all essential details, as in (3b).

3a. Stem cells were isolated, according to Johnson [23]. 3b. Stem cells were isolated using biotinylated carbon nanotubes coated with anti-CD34 antibodies.

Furthermore, cohesion and fluency are crucial in this section. One of the malpractices resulting in disrupted fluency is switching from passive voice to active and vice versa within the same paragraph, as shown in (4). This switching misleads and distracts the reader.

4. Behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 were programmed by using E-Prime. We took ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods). The preferred and unpreferred status of the music was operationalized along a continuum of pleasantness [ 4 ].

The problem with (4) is that the reader has to switch from the point of view of the experiment (passive voice) to the point of view of the experimenter (active voice). This switch causes confusion about the performer of the actions in the first and the third sentences. To improve the coherence and fluency of the paragraph above, you should be consistent in choosing the point of view: first person “we” or passive voice [ 5 ]. Let’s consider two revised examples in (5).

5a. We programmed behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 by using E-Prime. We took ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods) as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music. We operationalized the preferred and unpreferred status of the music along a continuum of pleasantness. 5b. Behavioral computer-based experiments of Study 1 were programmed by using E-Prime. Ratings of enjoyment, mood, and arousal were taken as the patients listened to preferred pleasant music and unpreferred music by using Visual Analogue Scales (SI Methods). The preferred and unpreferred status of the music was operationalized along a continuum of pleasantness.

If you choose the point of view of the experimenter, then you may end up with repetitive “we did this” sentences. For many readers, paragraphs with sentences all beginning with “we” may also sound disruptive. So if you choose active sentences, you need to keep the number of “we” subjects to a minimum and vary the beginnings of the sentences [ 6 ].

Interestingly, recent studies have reported that the Materials and Methods section is the only section in research papers in which passive voice predominantly overrides the use of the active voice [ 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. For example, Martínez shows a significant drop in active voice use in the Methods sections based on the corpus of 1 million words of experimental full text research articles in the biological sciences [ 7 ]. According to the author, the active voice patterned with “we” is used only as a tool to reveal personal responsibility for the procedural decisions in designing and performing experimental work. This means that while all other sections of the research paper use active voice, passive voice is still the most predominant in Materials and Methods sections.

Writing Materials and Methods sections is a meticulous and time consuming task requiring extreme accuracy and clarity. This is why when you complete your draft, you should ask for as much feedback from your colleagues as possible. Numerous readers of this section will help you identify the missing links and improve the technical style of this section.

Rule 3: Be meticulous and accurate in describing the Materials and Methods. Do not change the point of view within one paragraph.

3.2. writing results section.

For many authors, writing the Results section is more intimidating than writing the Materials and Methods section . If people are interested in your paper, they are interested in your results. That is why it is vital to use all your writing skills to objectively present your key findings in an orderly and logical sequence using illustrative materials and text.

Your Results should be organized into different segments or subsections where each one presents the purpose of the experiment, your experimental approach, data including text and visuals (tables, figures, schematics, algorithms, and formulas), and data commentary. For most journals, your data commentary will include a meaningful summary of the data presented in the visuals and an explanation of the most significant findings. This data presentation should not repeat the data in the visuals, but rather highlight the most important points. In the “standard” research paper approach, your Results section should exclude data interpretation, leaving it for the Discussion section. However, interpretations gradually and secretly creep into research papers: “Reducing the data, generalizing from the data, and highlighting scientific cases are all highly interpretive processes. It should be clear by now that we do not let the data speak for themselves in research reports; in summarizing our results, we interpret them for the reader” [ 10 ]. As a result, many journals including the Journal of Experimental Medicine and the Journal of Clinical Investigation use joint Results/Discussion sections, where results are immediately followed by interpretations.

Another important aspect of this section is to create a comprehensive and supported argument or a well-researched case. This means that you should be selective in presenting data and choose only those experimental details that are essential for your reader to understand your findings. You might have conducted an experiment 20 times and collected numerous records, but this does not mean that you should present all those records in your paper. You need to distinguish your results from your data and be able to discard excessive experimental details that could distract and confuse the reader. However, creating a picture or an argument should not be confused with data manipulation or falsification, which is a willful distortion of data and results. If some of your findings contradict your ideas, you have to mention this and find a plausible explanation for the contradiction.

In addition, your text should not include irrelevant and peripheral information, including overview sentences, as in (6).

6. To show our results, we first introduce all components of experimental system and then describe the outcome of infections.

Indeed, wordiness convolutes your sentences and conceals your ideas from readers. One common source of wordiness is unnecessary intensifiers. Adverbial intensifiers such as “clearly,” “essential,” “quite,” “basically,” “rather,” “fairly,” “really,” and “virtually” not only add verbosity to your sentences, but also lower your results’ credibility. They appeal to the reader’s emotions but lower objectivity, as in the common examples in (7):

7a. Table 3 clearly shows that … 7b. It is obvious from figure 4 that …

Another source of wordiness is nominalizations, i.e., nouns derived from verbs and adjectives paired with weak verbs including “be,” “have,” “do,” “make,” “cause,” “provide,” and “get” and constructions such as “there is/are.”

8a. We tested the hypothesis that there is a disruption of membrane asymmetry. 8b. In this paper we provide an argument that stem cells repopulate injured organs.

In the sentences above, the abstract nominalizations “disruption” and “argument” do not contribute to the clarity of the sentences, but rather clutter them with useless vocabulary that distracts from the meaning. To improve your sentences, avoid unnecessary nominalizations and change passive verbs and constructions into active and direct sentences.

9a. We tested the hypothesis that the membrane asymmetry is disrupted. 9b. In this paper we argue that stem cells repopulate injured organs.

Your Results section is the heart of your paper, representing a year or more of your daily research. So lead your reader through your story by writing direct, concise, and clear sentences.

Rule 4: Be clear, concise, and objective in describing your Results.

3.3. now it is time for your introduction.

Now that you are almost half through drafting your research paper, it is time to update your outline. While describing your Methods and Results, many of you diverged from the original outline and re-focused your ideas. So before you move on to create your Introduction, re-read your Methods and Results sections and change your outline to match your research focus. The updated outline will help you review the general picture of your paper, the topic, the main idea, and the purpose, which are all important for writing your introduction.

The best way to structure your introduction is to follow the three-move approach shown in Table 3 .

Adapted from Swales and Feak [ 11 ].

The moves and information from your outline can help to create your Introduction efficiently and without missing steps. These moves are traffic signs that lead the reader through the road of your ideas. Each move plays an important role in your paper and should be presented with deep thought and care. When you establish the territory, you place your research in context and highlight the importance of your research topic. By finding the niche, you outline the scope of your research problem and enter the scientific dialogue. The final move, “occupying the niche,” is where you explain your research in a nutshell and highlight your paper’s significance. The three moves allow your readers to evaluate their interest in your paper and play a significant role in the paper review process, determining your paper reviewers.

Some academic writers assume that the reader “should follow the paper” to find the answers about your methodology and your findings. As a result, many novice writers do not present their experimental approach and the major findings, wrongly believing that the reader will locate the necessary information later while reading the subsequent sections [ 5 ]. However, this “suspense” approach is not appropriate for scientific writing. To interest the reader, scientific authors should be direct and straightforward and present informative one-sentence summaries of the results and the approach.

Another problem is that writers understate the significance of the Introduction. Many new researchers mistakenly think that all their readers understand the importance of the research question and omit this part. However, this assumption is faulty because the purpose of the section is not to evaluate the importance of the research question in general. The goal is to present the importance of your research contribution and your findings. Therefore, you should be explicit and clear in describing the benefit of the paper.

The Introduction should not be long. Indeed, for most journals, this is a very brief section of about 250 to 600 words, but it might be the most difficult section due to its importance.

Rule 5: Interest your reader in the Introduction section by signalling all its elements and stating the novelty of the work.

3.4. discussion of the results.

For many scientists, writing a Discussion section is as scary as starting a paper. Most of the fear comes from the variation in the section. Since every paper has its unique results and findings, the Discussion section differs in its length, shape, and structure. However, some general principles of writing this section still exist. Knowing these rules, or “moves,” can change your attitude about this section and help you create a comprehensive interpretation of your results.

The purpose of the Discussion section is to place your findings in the research context and “to explain the meaning of the findings and why they are important, without appearing arrogant, condescending, or patronizing” [ 11 ]. The structure of the first two moves is almost a mirror reflection of the one in the Introduction. In the Introduction, you zoom in from general to specific and from the background to your research question; in the Discussion section, you zoom out from the summary of your findings to the research context, as shown in Table 4 .

Adapted from Swales and Feak and Hess [ 11 , 12 ].

The biggest challenge for many writers is the opening paragraph of the Discussion section. Following the moves in Table 1 , the best choice is to start with the study’s major findings that provide the answer to the research question in your Introduction. The most common starting phrases are “Our findings demonstrate . . .,” or “In this study, we have shown that . . .,” or “Our results suggest . . .” In some cases, however, reminding the reader about the research question or even providing a brief context and then stating the answer would make more sense. This is important in those cases where the researcher presents a number of findings or where more than one research question was presented. Your summary of the study’s major findings should be followed by your presentation of the importance of these findings. One of the most frequent mistakes of the novice writer is to assume the importance of his findings. Even if the importance is clear to you, it may not be obvious to your reader. Digesting the findings and their importance to your reader is as crucial as stating your research question.

Another useful strategy is to be proactive in the first move by predicting and commenting on the alternative explanations of the results. Addressing potential doubts will save you from painful comments about the wrong interpretation of your results and will present you as a thoughtful and considerate researcher. Moreover, the evaluation of the alternative explanations might help you create a logical step to the next move of the discussion section: the research context.

The goal of the research context move is to show how your findings fit into the general picture of the current research and how you contribute to the existing knowledge on the topic. This is also the place to discuss any discrepancies and unexpected findings that may otherwise distort the general picture of your paper. Moreover, outlining the scope of your research by showing the limitations, weaknesses, and assumptions is essential and adds modesty to your image as a scientist. However, make sure that you do not end your paper with the problems that override your findings. Try to suggest feasible explanations and solutions.

If your submission does not require a separate Conclusion section, then adding another paragraph about the “take-home message” is a must. This should be a general statement reiterating your answer to the research question and adding its scientific implications, practical application, or advice.

Just as in all other sections of your paper, the clear and precise language and concise comprehensive sentences are vital. However, in addition to that, your writing should convey confidence and authority. The easiest way to illustrate your tone is to use the active voice and the first person pronouns. Accompanied by clarity and succinctness, these tools are the best to convince your readers of your point and your ideas.

Rule 6: Present the principles, relationships, and generalizations in a concise and convincing tone.

4. choosing the best working revision strategies.

Now that you have created the first draft, your attitude toward your writing should have improved. Moreover, you should feel more confident that you are able to accomplish your project and submit your paper within a reasonable timeframe. You also have worked out your writing schedule and followed it precisely. Do not stop ― you are only at the midpoint from your destination. Just as the best and most precious diamond is no more than an unattractive stone recognized only by trained professionals, your ideas and your results may go unnoticed if they are not polished and brushed. Despite your attempts to present your ideas in a logical and comprehensive way, first drafts are frequently a mess. Use the advice of Paul Silvia: “Your first drafts should sound like they were hastily translated from Icelandic by a non-native speaker” [ 2 ]. The degree of your success will depend on how you are able to revise and edit your paper.

The revision can be done at the macrostructure and the microstructure levels [ 13 ]. The macrostructure revision includes the revision of the organization, content, and flow. The microstructure level includes individual words, sentence structure, grammar, punctuation, and spelling.

The best way to approach the macrostructure revision is through the outline of the ideas in your paper. The last time you updated your outline was before writing the Introduction and the Discussion. Now that you have the beginning and the conclusion, you can take a bird’s-eye view of the whole paper. The outline will allow you to see if the ideas of your paper are coherently structured, if your results are logically built, and if the discussion is linked to the research question in the Introduction. You will be able to see if something is missing in any of the sections or if you need to rearrange your information to make your point.

The next step is to revise each of the sections starting from the beginning. Ideally, you should limit yourself to working on small sections of about five pages at a time [ 14 ]. After these short sections, your eyes get used to your writing and your efficiency in spotting problems decreases. When reading for content and organization, you should control your urge to edit your paper for sentence structure and grammar and focus only on the flow of your ideas and logic of your presentation. Experienced researchers tend to make almost three times the number of changes to meaning than novice writers [ 15 , 16 ]. Revising is a difficult but useful skill, which academic writers obtain with years of practice.

In contrast to the macrostructure revision, which is a linear process and is done usually through a detailed outline and by sections, microstructure revision is a non-linear process. While the goal of the macrostructure revision is to analyze your ideas and their logic, the goal of the microstructure editing is to scrutinize the form of your ideas: your paragraphs, sentences, and words. You do not need and are not recommended to follow the order of the paper to perform this type of revision. You can start from the end or from different sections. You can even revise by reading sentences backward, sentence by sentence and word by word.

One of the microstructure revision strategies frequently used during writing center consultations is to read the paper aloud [ 17 ]. You may read aloud to yourself, to a tape recorder, or to a colleague or friend. When reading and listening to your paper, you are more likely to notice the places where the fluency is disrupted and where you stumble because of a very long and unclear sentence or a wrong connector.

Another revision strategy is to learn your common errors and to do a targeted search for them [ 13 ]. All writers have a set of problems that are specific to them, i.e., their writing idiosyncrasies. Remembering these problems is as important for an academic writer as remembering your friends’ birthdays. Create a list of these idiosyncrasies and run a search for these problems using your word processor. If your problem is demonstrative pronouns without summary words, then search for “this/these/those” in your text and check if you used the word appropriately. If you have a problem with intensifiers, then search for “really” or “very” and delete them from the text. The same targeted search can be done to eliminate wordiness. Searching for “there is/are” or “and” can help you avoid the bulky sentences.

The final strategy is working with a hard copy and a pencil. Print a double space copy with font size 14 and re-read your paper in several steps. Try reading your paper line by line with the rest of the text covered with a piece of paper. When you are forced to see only a small portion of your writing, you are less likely to get distracted and are more likely to notice problems. You will end up spotting more unnecessary words, wrongly worded phrases, or unparallel constructions.

After you apply all these strategies, you are ready to share your writing with your friends, colleagues, and a writing advisor in the writing center. Get as much feedback as you can, especially from non-specialists in your field. Patiently listen to what others say to you ― you are not expected to defend your writing or explain what you wanted to say. You may decide what you want to change and how after you receive the feedback and sort it in your head. Even though some researchers make the revision an endless process and can hardly stop after a 14th draft; having from five to seven drafts of your paper is a norm in the sciences. If you can’t stop revising, then set a deadline for yourself and stick to it. Deadlines always help.

Rule 7: Revise your paper at the macrostructure and the microstructure level using different strategies and techniques. Receive feedback and revise again.

5. it is time to submit.

It is late at night again. You are still in your lab finishing revisions and getting ready to submit your paper. You feel happy ― you have finally finished a year’s worth of work. You will submit your paper tomorrow, and regardless of the outcome, you know that you can do it. If one journal does not take your paper, you will take advantage of the feedback and resubmit again. You will have a publication, and this is the most important achievement.

What is even more important is that you have your scheduled writing time that you are going to keep for your future publications, for reading and taking notes, for writing grants, and for reviewing papers. You are not going to lose stamina this time, and you will become a productive scientist. But for now, let’s celebrate the end of the paper.

- Hayes JR. In: The Science of Writing: Theories, Methods, Individual Differences, and Applications. Levy CM, Ransdell SE, editors. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1996. A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing; pp. 1–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Silvia PJ. How to Write a Lot. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitesides GM. Whitesides’ Group: Writing a Paper. Adv Mater. 2004; 16 (15):1375–1377. [ Google Scholar ]

- Soto D, Funes MJ, Guzmán-García A, Warbrick T, Rotshtein T, Humphreys GW. Pleasant music overcomes the loss of awareness in patients with visual neglect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009; 106 (14):6011–6016. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hofmann AH. Scientific Writing and Communication. Papers, Proposals, and Presentations. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zeiger M. Essentials of Writing Biomedical Research Papers. 2nd edition. San Francisco, CA: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- Martínez I. Native and non-native writers’ use of first person pronouns in the different sections of biology research articles in English. Journal of Second Language Writing. 2005; 14 (3):174–190. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodman L. The Active Voice In Scientific Articles: Frequency And Discourse Functions. Journal Of Technical Writing And Communication. 1994; 24 (3):309–331. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tarone LE, Dwyer S, Gillette S, Icke V. On the use of the passive in two astrophysics journal papers with extensions to other languages and other fields. English for Specific Purposes. 1998; 17 :113–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Penrose AM, Katz SB. Writing in the sciences: Exploring conventions of scientific discourse. New York: St. Martin’s Press; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- Swales JM, Feak CB. Academic Writing for Graduate Students. 2nd edition. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hess DR. How to Write an Effective Discussion. Respiratory Care. 2004; 29 (10):1238–1241. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Belcher WL. Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks: a guide to academic publishing success. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Single PB. Demystifying Dissertation Writing: A Streamlined Process of Choice of Topic to Final Text. Virginia: Stylus Publishing LLC; 2010. [ Google Scholar ]

- Faigley L, Witte SP. Analyzing revision. Composition and Communication. 1981; 32 :400–414. [ Google Scholar ]

- Flower LS, Hayes JR, Carey L, Schriver KS, Stratman J. Detection, diagnosis, and the strategies of revision. College Composition and Communication. 1986; 37 (1):16–55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Young BR. In: A Tutor’s Guide: Helping Writers One to One. Rafoth B, editor. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers; 2005. Can You Proofread This? pp. 140–158. [ Google Scholar ]

WRITING A SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH ARTICLE | Format for the paper | Edit your paper! | Useful books | FORMAT FOR THE PAPER Scientific research articles provide a method for scientists to communicate with other scientists about the results of their research. A standard format is used for these articles, in which the author presents the research in an orderly, logical manner. This doesn't necessarily reflect the order in which you did or thought about the work. This format is: | Title | Authors | Introduction | Materials and Methods | Results (with Tables and Figures ) | Discussion | Acknowledgments | Literature Cited | TITLE Make your title specific enough to describe the contents of the paper, but not so technical that only specialists will understand. The title should be appropriate for the intended audience. The title usually describes the subject matter of the article: Effect of Smoking on Academic Performance" Sometimes a title that summarizes the results is more effective: Students Who Smoke Get Lower Grades" AUTHORS 1. The person who did the work and wrote the paper is generally listed as the first author of a research paper. 2. For published articles, other people who made substantial contributions to the work are also listed as authors. Ask your mentor's permission before including his/her name as co-author. ABSTRACT 1. An abstract, or summary, is published together with a research article, giving the reader a "preview" of what's to come. Such abstracts may also be published separately in bibliographical sources, such as Biologic al Abstracts. They allow other scientists to quickly scan the large scientific literature, and decide which articles they want to read in depth. The abstract should be a little less technical than the article itself; you don't want to dissuade your potent ial audience from reading your paper. 2. Your abstract should be one paragraph, of 100-250 words, which summarizes the purpose, methods, results and conclusions of the paper. 3. It is not easy to include all this information in just a few words. Start by writing a summary that includes whatever you think is important, and then gradually prune it down to size by removing unnecessary words, while still retaini ng the necessary concepts. 3. Don't use abbreviations or citations in the abstract. It should be able to stand alone without any footnotes. INTRODUCTION What question did you ask in your experiment? Why is it interesting? The introduction summarizes the relevant literature so that the reader will understand why you were interested in the question you asked. One to fo ur paragraphs should be enough. End with a sentence explaining the specific question you asked in this experiment. MATERIALS AND METHODS 1. How did you answer this question? There should be enough information here to allow another scientist to repeat your experiment. Look at other papers that have been published in your field to get some idea of what is included in this section. 2. If you had a complicated protocol, it may helpful to include a diagram, table or flowchart to explain the methods you used. 3. Do not put results in this section. You may, however, include preliminary results that were used to design the main experiment that you are reporting on. ("In a preliminary study, I observed the owls for one week, and found that 73 % of their locomotor activity occurred during the night, and so I conducted all subsequent experiments between 11 pm and 6 am.") 4. Mention relevant ethical considerations. If you used human subjects, did they consent to participate. If you used animals, what measures did you take to minimize pain? RESULTS 1. This is where you present the results you've gotten. Use graphs and tables if appropriate, but also summarize your main findings in the text. Do NOT discuss the results or speculate as to why something happened; t hat goes in th e Discussion. 2. You don't necessarily have to include all the data you've gotten during the semester. This isn't a diary. 3. Use appropriate methods of showing data. Don't try to manipulate the data to make it look like you did more than you actually did. "The drug cured 1/3 of the infected mice, another 1/3 were not affected, and the third mouse got away." TABLES AND GRAPHS 1. If you present your data in a table or graph, include a title describing what's in the table ("Enzyme activity at various temperatures", not "My results".) For graphs, you should also label the x and y axes. 2. Don't use a table or graph just to be "fancy". If you can summarize the information in one sentence, then a table or graph is not necessary. DISCUSSION 1. Highlight the most significant results, but don't just repeat what you've written in the Results section. How do these results relate to the original question? Do the data support your hypothesis? Are your results consistent with what other investigators have reported? If your results were unexpected, try to explain why. Is there another way to interpret your results? What further research would be necessary to answer the questions raised by your results? How do y our results fit into the big picture? 2. End with a one-sentence summary of your conclusion, emphasizing why it is relevant. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This section is optional. You can thank those who either helped with the experiments, or made other important contributions, such as discussing the protocol, commenting on the manuscript, or buying you pizza. REFERENCES (LITERATURE CITED) There are several possible ways to organize this section. Here is one commonly used way: 1. In the text, cite the literature in the appropriate places: Scarlet (1990) thought that the gene was present only in yeast, but it has since been identified in the platypus (Indigo and Mauve, 1994) and wombat (Magenta, et al., 1995). 2. In the References section list citations in alphabetical order. Indigo, A. C., and Mauve, B. E. 1994. Queer place for qwerty: gene isolation from the platypus. Science 275, 1213-1214. Magenta, S. T., Sepia, X., and Turquoise, U. 1995. Wombat genetics. In: Widiculous Wombats, Violet, Q., ed. New York: Columbia University Press. p 123-145. Scarlet, S.L. 1990. Isolation of qwerty gene from S. cerevisae. Journal of Unusual Results 36, 26-31. EDIT YOUR PAPER!!! "In my writing, I average about ten pages a day. Unfortunately, they're all the same page." Michael Alley, The Craft of Scientific Writing A major part of any writing assignment consists of re-writing. Write accurately Scientific writing must be accurate. Although writing instructors may tell you not to use the same word twice in a sentence, it's okay for scientific writing, which must be accurate. (A student who tried not to repeat the word "hamster" produced this confusing sentence: "When I put the hamster in a cage with the other animals, the little mammals began to play.") Make sure you say what you mean. Instead of: The rats were injected with the drug. (sounds like a syringe was filled with drug and ground-up rats and both were injected together) Write: I injected the drug into the rat.

- Be careful with commonly confused words:

Temperature has an effect on the reaction. Temperature affects the reaction.

I used solutions in various concentrations. (The solutions were 5 mg/ml, 10 mg/ml, and 15 mg/ml) I used solutions in varying concentrations. (The concentrations I used changed; sometimes they were 5 mg/ml, other times they were 15 mg/ml.)

Less food (can't count numbers of food) Fewer animals (can count numbers of animals)

A large amount of food (can't count them) A large number of animals (can count them)

The erythrocytes, which are in the blood, contain hemoglobin. The erythrocytes that are in the blood contain hemoglobin. (Wrong. This sentence implies that there are erythrocytes elsewhere that don't contain hemoglobin.)

Write clearly

1. Write at a level that's appropriate for your audience.

"Like a pigeon, something to admire as long as it isn't over your head." Anonymous

2. Use the active voice. It's clearer and more concise than the passive voice.

Instead of: An increased appetite was manifested by the rats and an increase in body weight was measured. Write: The rats ate more and gained weight.

3. Use the first person.

Instead of: It is thought Write: I think

Instead of: The samples were analyzed Write: I analyzed the samples

4. Avoid dangling participles.

"After incubating at 30 degrees C, we examined the petri plates." (You must've been pretty warm in there.)

Write succinctly

1. Use verbs instead of abstract nouns

Instead of: take into consideration Write: consider

2. Use strong verbs instead of "to be"

Instead of: The enzyme was found to be the active agent in catalyzing... Write: The enzyme catalyzed...

3. Use short words.

Instead of: Write: possess have sufficient enough utilize use demonstrate show assistance help terminate end

4. Use concise terms.

Instead of: Write: prior to before due to the fact that because in a considerable number of cases often the vast majority of most during the time that when in close proximity to near it has long been known that I'm too lazy to look up the reference

5. Use short sentences. A sentence made of more than 40 words should probably be rewritten as two sentences.

"The conjunction 'and' commonly serves to indicate that the writer's mind still functions even when no signs of the phenomenon are noticeable." Rudolf Virchow, 1928

Check your grammar, spelling and punctuation

1. Use a spellchecker, but be aware that they don't catch all mistakes.

"When we consider the animal as a hole,..." Student's paper

2. Your spellchecker may not recognize scientific terms. For the correct spelling, try Biotech's Life Science Dictionary or one of the technical dictionaries on the reference shelf in the Biology or Health Sciences libraries.

3. Don't, use, unnecessary, commas.

4. Proofread carefully to see if you any words out.

USEFUL BOOKS

Victoria E. McMillan, Writing Papers in the Biological Sciences , Bedford Books, Boston, 1997 The best. On sale for about $18 at Labyrinth Books, 112th Street. On reserve in Biology Library

Jan A. Pechenik, A Short Guide to Writing About Biology , Boston: Little, Brown, 1987

Harrison W. Ambrose, III & Katharine Peckham Ambrose, A Handbook of Biological Investigation , 4th edition, Hunter Textbooks Inc, Winston-Salem, 1987 Particularly useful if you need to use statistics to analyze your data. Copy on Reference shelf in Biology Library.

Robert S. Day, How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper , 4th edition, Oryx Press, Phoenix, 1994. Earlier editions also good. A bit more advanced, intended for those writing papers for publication. Fun to read. Several copies available in Columbia libraries.

William Strunk, Jr. and E. B. White, The Elements of Style , 3rd ed. Macmillan, New York, 1987. Several copies available in Columbia libraries. Strunk's first edition is available on-line.

BIOLOGY JUNCTION

Test And Quizzes for Biology, Pre-AP, Or AP Biology For Teachers And Students

A Step-By-Step Guide on Writing a Biology Research Paper

For many students, writing a biology research paper can seem like a daunting task. They want to come up with the best possible report, but they don’t realize that planning the entire writing process can improve the quality of their work and save them time while writing. In this article, you’ll learn how to find a good topic, outline your paper, use statistical tests, and avoid using hedge words.

Finding a good topic

The first step in writing a well-constructed biology research paper is choosing a topic. There are a variety of topics to choose from within the biological field. Choose one that interests you and captures your attention. A compelling topic motivates you to work hard and produce a high-quality paper.

While choosing a topic, keep in mind that biology research is time-consuming and requires extensive research. For this reason, choosing a topic that piques the interest of the reader is crucial. In addition to this, you should choose a topic that is appropriate for the type of biology paper you need to write. After all, you do not want to bore the reader with an inane paper.

A good biology research paper topic should be well-supported by solid scientific evidence. Select a topic only after thorough research, and be sure to include steps and references from reliable sources. A biological research paper topic can be an interesting journey into the world of nature. You could choose to research the effects of stress on the human body or investigate the biological mechanisms of the human reproductive system.

Outlining your paper

The first step in drafting a biological research paper is to create an outline. This is meant to be a roadmap that helps you understand and visualize the subject. An outline can help you avoid common writing mistakes and shape your paper into a serious piece of work. The next step is to gather information about the subject that will support your main idea.

Once you have a topic, you can start writing your outline. Outlines should include at least one idea, a brief introduction, and a conclusion. The introduction, ideas, and conclusion should be numbered in the order you plan to present your information. The main ideas are generally a collection of facts and figures. For example, in a literature review, these points might be chapters from a book, a series of dates from history, or the methods and results of a scientific paper.

When writing a biological research paper, you should use scholarly sources. While there is a lot of misinformation on the internet, it’s best to stick to academic essay writing service to get the most accurate information. Most libraries allow you to select a peer-review filter that will restrict your search results to academic journals. It’s also helpful to be familiar with the differences between scholarly and popular sources.

Using statistical tests

Using statistical tests when writing a biological paper requires that you make certain assumptions about the results you are describing. The most common statistical tests are parametric tests that are based on assumptions about conditions or parameters. About 22% of the papers in our review reported violations of these assumptions, and such violations can lead to inappropriate or invalid conclusions.

Statistical tests are important in biological research because they allow researchers to determine if their data is statistically significant or not. The power of these tests depends on the size of the dataset. Larger datasets produce more significant results. The power of these tests also depends on the assumption of independence between measurements. This is important because the results can be different if there are duplications or different levels of replications.

Hypothesis tests are useful in evaluating experimental data. They identify differences and patterns in data. They are useful tools for structuring biological research.

Avoiding hedge words

Hedge words are phrases or words used to express uncertainty in a scientific paper. They can help writers avoid making inaccurate claims while still being respectful of the reader’s opinion. However, writers must be careful to avoid using too many hedges.

Listed below are a few guidelines to help you avoid these words:

- Hedge words shift the burden of responsibility from the writer to the reader.

- Hedge words can be a sign of uncertainty or overstatement. They can also be used to limit the scope of an assertion. They also convey an opinion or hypothesis. When choosing a hedging strategy, be careful not to use words such as “no data” or “unreliable.” These words can convey a degree of uncertainty and imply that the findings cannot be confirmed.

The use of hedge words is common in academic writing. However, they hurt your audience. It is a linguistic strategy that writers use as a way to reassure readers. The goal is to guide readers and make them feel comfortable with the idea that the author does not know all the answers.

Choosing a format

Biological research papers have different formats, and you should choose one that suits the nature of your paper. It should be based on credible and peer-reviewed sources. The best sources to use for biology papers are books, specialized journals, and databases. Avoid personal blogs, social networks, and internet discussions, as these are not suitable for a research paper.

Biology research papers focus on a specific issue and present different arguments in support of a thesis. Traditionally, they are based on peer-reviewed sources, but you can also conduct your independent research and present unique findings. Biology is a complex field of study. The subject matter varies, from the basic structure of living things to the functions of different organs. It also explores the process of evolution and the life span of different species.

Formatting your bibliography

When writing a biological research paper, the format of your bibliography is crucial. It should follow a standardized citation style such as the “Author, Date” scientific style. The format should be arranged alphabetically by author, and you should use numbered references to indicate key sources.

Reference lists must be comprehensive and contain enough information to enable readers to find the sources themselves. Although the format is not as important as completeness, it can help readers quickly identify the authors and sources. Bibliographies are usually reverse-indented to make them easier to find.

In-text citations should include the author’s last name, preferred name, and the page number. Usually, authors do not separate their surname and year of publication. In addition, you should also include the location, which is usually the publisher’s office.

If a work has more than four authors, you should list up to ten in the reference list. The first author’s surname should be used, followed by “et al.” Likewise, you should list more than ten authors in the reference list.

When writing a biological research paper, it is important to ensure that your bibliography is formatted properly. When you write the title, you should use boldface and uppercase letters. The title should also be focused, not too long or too short. It should take one or two lines and all text should be double-spaced. You should also type the author’s name after the title. Don’t forget to indicate the location of your research as well as the date you submitted the paper.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

BIO181 - General Biology

- Topic Selection

- Keywords/Phrases

- Boolean Search

- Subject Headings

- Background Resources

- Books/E-books

- APA This link opens in a new window

- Academic Integrity

Writing a Biology Research Paper

- Biology Research Paper Format - California State University A biological research paper is a form of communication in which the investigator succinctly presents and interprets data collected in an investigation. Writing such papers is similar to writing in other scientific disciplines except that the format will differ as will the criteria for grading. For individual biology courses, students should use this document as a guide as well as refer to course guidelines for individual course assignments.

- 5 Steps To Succeed In Writing a Biology Research Paper If you’ve been assigned a biology research paper, there is hope: Our guide to the five key steps to writing a biology research paper will have you ready and able to produce a top-quality essay in no time.

- Is Grammarly Cheating? – Helpful Professor Explains No, Grammarly is almost never cheating. There’s a free version – so give it a go yourself and see if you’re one of the 98% of students who get better grades with Grammarly.

- << Previous: Help

- Last Updated: Mar 10, 2024 2:21 PM

- URL: https://paradisevalley.libguides.com/bio181

WRITING A BIOLOGICAL RESEARCH PAPER

An introduction to structure and style.

Wade B. Worthen Biology Dept . Furman University

This document is designed to help you write a successful research paper in the biological sciences. The first section summarizes the structural and stylistic requirements for research papers submitted in biology courses. Most specifically, this includes Research and Analysis (BGY 222) and Research in Biology (502). However, your professors may expect this format in other courses, as well. Ask about the structure of research papers and lab reports when the assignment is made so you can get started on the right track.

I. Structuring an Experimental Report

There are several quality texts available that should be used as structural and stylistic guides. Use them! One book, McMillan's Writing Papers in the Biological Sciences , is often a required text for Research and Analysis. It highlights the structure of both primary and secondary research papers. There are excellent examples describing common mistakes. Another manual is Strunk and White's Elements of Style . Remember all those little points about English grammar that you learned in eighth grade and forgot by ninth? Well, they are all in Elements of Style . Remember this: the quality of the writing reflects the quality of the research! Clear, direct prose that communicates your ideas in a logical manner is rewarded. The greatest experiment in the world is worthless unless the reader understands what was done.

Here is an outline of the proper structure of an experimental research paper. Although the sections should be presented in this order, they are not written in this order. Suggestions for writing sequence follow later.

A. Title. The title should be informative, specific and short (13 word max., usually). These objectives are difficult to satisfy concurrently. Typically, titles include: 1) the species studied (common and/or Latin names as space permits), 2) the variables addressed, and 3) the site, if it is important. Obviously, the space constraints will occasionally force you to exclude one of these parameters. Here are some examples: 1. Phenotypic and demographic variability among patches of Maianthemum canadense ( Desf .) in central New Jersey, and the use of self-incompatibility for clone discrimination. Long! 23 words, but includes all three parameters. This is difficult to shorten, because two different questions were addressed in one study. 2. Fish predation on Notonecta ( Hemiptera ): relationship between prey risk and habitat utilization. Nice length (12 words), but site has been omitted. Good description of the problem and mention of the organism (genus, in this case). 3. Foraging behavior of a western reef heron in North America. 4. Foraging behavior and food of grey herons Ardea cinerea on the Ythan estuary. These include all three aspects within the standard space constraint. However, in order to fit the site into the title, the topic is rather general (foraging behavior). The title should reflect the thrust of the paper. If site is important (maybe there are geographical differences in foraging behavior in these species), it should be included. If the study is a broad-based analysis of several foraging behaviors, then it is more appropriate to say 'foraging behavior' than to list every variable studied. Site is typically NOT included in laboratory investigations, as the purpose of the lab is to standardize (and thus exclude) the effect of environmental variables…. So hopefully, one lab is as good as another. Good titles are hard to write, and they take more time than you might think.

B. Abstract. This is a concise summary of the paper. Ideally, it should be short ( 500 word maximum ), and should include at least one sentence describing each of these topics :

- objectives and introduction (background)

- conclusions and discussion (relevance)

Again, the space limitations may force you to be selective. In addition, the methods and result may be difficult to describe completely in single sentences, and may require a larger fraction of the space budget. Certainly, the results are the most important part of the abstract; they represent the 'meat' of the experiment and cannot be slighted. However, you must also include a conclusion sentence; what did the results mean? If published, the abstract will appear in citation sources such as Biological Abstracts and Science Citation Index. It is the first thing someone will read, and it must be descriptive and interesting! The abstract demands clear, direct writing. When readers finish the abstract, they should be so intrigued by the experiment that they decide to read the entire paper. What search strategy do you use when search for articles? You enter keywords and then scan the list of article titles that appear. Like a fish at bait, you 'nibble' at an interesting one by reading the abstract. Here is where the author 'sets the hook'. If it's interesting, you read the article. If it is not, the author has lost you and you start to nibble on other titles again. Abstracts are also very difficult to write; it will take more time to write than any other paragraph in the whole paper.

C. Introduction. The introduction serves two functions. First, it provides the reader with the background information relevant to your experiment. Second, it presents the objectives of your study. These two functions are directly related; the background information that you provide should justify your experiment. After reading the background, the reader should understand why your question is significant. To write a good introduction, think of a funnel. Start with a broad background statement that provides some common ground for readers with different levels of expertise. Then, develop the information in the field that is important to your topic, focusing in on the objectives of your study. Try and maintain the flow from broad to specific.

Perhaps your paper is on foraging strategies of insectivorous birds. You might start off with a general statement on foraging strategy, and then highlight some of the relevant theories applied to animals, in general. Then you might focus on the particular developments and applications of avian foraging behavior. Finally, you could specify the energetic constraints imposed on insectivorous birds, and discuss this material. This section should conclude with some indication about the gap in our knowledge in this area. You then present your objectives, showing how your study attempts to fill this gap. At this point, the reader knows how your study relates to the field and understands why your question needs to be addressed.

There are space constraints on the introduction, too. This space constraint may alter your presentation. You may not be able to start out as broadly as you had intended, or the transition from background to objectives may need to be more direct. Remember: the introduction must demonstrate a logical progression to your objectives. This demands logical transitions. The topics in your introduction must be linked effectively so the reader can follow your argument. Excess information or tangential paragraphs will throw your reader off the track. Don't use the introduction as an information dump to show the reader how much you found on a topic. Show the reader you understand the relevant issues in a field and know how your study complements this information. Typically, the final paragraph of the introduction contains your “purpose statement”. It describes the relationship you are testing, and it may even give a very brief (one sentence) synopsis of what was found. So, the introduction “funnels down” from general theory, to specific theory or examples relevant to your model system, to a presentation of conflicting opinions or gaps in our understanding, to the purpose of your experiment (which should address the conflict or fill the gap). In some cases, your introduction may need to be long to place your study in perspective. In this situation, you would want to present your objectives early so the reader can relate your background information to your question. Finally, unlike papers in the Humanities, do not begin your introduction with a quote or hyperbole. Indeed, avoid using direct quotations! In science, paraphrase the point of the author and cite them parenthetically at the end of the sentence.

D. Methods. This should be the easiest section to write; you simply state what you did. It is written in the past tense; don't write a series of instructions, write a description of the experiment you conducted. In the course of the methods section, you should specify your experimental design, describing the levels of your independent variables and the variables you chose to measure (dependent variables). You should also justify why you performed these methods. Why did you choose these dependent variables to address your question? Why did you choose these levels of your independent variables for manipulation? Be sure to include the equipment that you used (manufacturer and model number, if unusual), and define the environment where the test was performed (temp, light, etc.). In a field study, a brief description of the field sites usually appears first in the methods. Finally, you should specify the statistical tests (and software packages) you used to analyze the data, and any transformations performed.

E. Results. You may think the results should be easy, too; this is simply the information that your experiment produced. However, interesting results sections are very difficult to write. You usually have several specific statements that you want to make (the new 'facts' that you have found), but you also have statistical analyses to present and figures and tables describing your results. First, analyze your data. Which independent variables had significant effects on your dependent variables? Make your figures and tables describe these patterns (see part VI). Digest these patterns; interpret your results before you start to write. After completing your analyses, you will have to decide on an ORDER in which to present them. This is not necessarily the order in which the tests were done. You are trying to make a logical argument; presenting your results in the most logical order will greatly assist the efficacy of the argument. When you know what your results mean, you can try to explain them to the reader. Read it back to yourself, out loud. If you stumble over grammar or can't understand it yourself, the reader won't have a chance! When you are ready to begin, start out with a declarative statement: "Hours in sunlight had a significant effect on plant growth." Now, call the reader's attention to the table or figure that shows this effect to be statistically significant: "Hours in sunlight... (Table 1) ." Table 1 might be the Analysis of Variance you performed, which documents that the hours of sunlight had a statistically significant impact on plant growth at the p=0.0025 level. As such, you might include the test and the alpha level parenthetically (optional): "Hours in sunlight... (ANOVA p=0.0025; Table 1)." Now, describe the pattern, and tell the reader where this information is presented: "On average, plants in the 'long exposure' treatment grew significantly more than the plants in the 'medium exposure' or 'short exposure' treatment ( Bonferroni t-test, p= 0.05; Figure 1)." Figure 1 might be a bar chart comparing growth of plants in the three light exposure treatments. The appropriate mean comparison test documents that the means are significantly different at the p=0.05 level. Next, present a conclusion statement for the paragraph. "Evidently, plant growth was stimulated by increased exposure to sunlight". So, here is your first paragraph: "Hours in sunlight had a significant effect on plant growth (ANOVA, p = 0.0025, Table 1). On average, plant in the 'long exposure' treatment grew significantly more than the plants in the 'medium exposure' or 'short exposure' treatment; ( Bonferroni t-test, p= 0.05; Figure 1). Evidently, plant growth was stimulated by increased exposure to sunlight."

Important Don'ts!!

1. Don't begin a statement with:

- The ANOVA showed that .."

- The Chi-square test showed that..."

- The t-test showed that..."

Statistical tests don't show anything. They just crunch numbers in a particular way. It is up to the experimenter - YOU - to interpret the result of a statistical test. For instance, a Chi-square test may indicate that a particular set of data would only occur by chance 5% of the time (p = 0.05). This information has no intrinsic meaning; some experimenters may interpret this pattern as significantly deviant from random chance while others, using a more stringent criterion (p = 0.01) may not. Make a declarative statement and refer to the statistical analysis that supports this interpretation.

2. Don't present a long list of significant results without interpretation:

"Hours in sunlight significantly affected growth (Table 1). Soil moisture significantly affected plant growth (Table 2). Soil nitrogen also had a significant effect on plant growth (Table 3)." You should develop each point completely before moving on to another point. After you say that an independent variable has an effect on a dependent variable, describe the effect; how did the levels of the independent variable differ? What does this mean? Show the reader the significance of the result.

3. Number your tables and figures after you write your results section!

The first table that is referred to in the results section is, by definition, 'Table 1'. Likewise, the first figure referred to, even if it is after table 1, is called 'Figure 1'. You may not present the results in the sequence in which they were analyzed. Recognize that the logical development of your results may demand a different sequence, and the table and figure numbering should complement this new order.

The results section is where you 'present your case'. The logical flow is critical; you must convince your reader that your argument is sound. If the readers are confused by your results, or do not follow your interpretation, they will not believe you. They will not accept that your conclusions are correct and important, and they will not recognize the relevance of your experiment.

F. Discussion. The discussion is where you explain your results and interpret them in light of other work in the field. Usually, the discussion takes the shape of an inverted funnel. Start by presenting the essential conclusions of your specific study. (This leads directly from your results section, and provides a natural transition.) Then, apply your conclusions to the body of background information you relayed in your introduction. You may broaden your focus as you proceed. Remember the background information you presented in your introduction? That was the information you felt was relevant to your experiment. Now, discuss how your new findings relate to this background information. Are the major hypotheses in the field support by your research, or contradicted? The discussion and the introduction should reflect one another to some degree, with the discussion bringing your paper “full-circle”, integrating your results with the literature you described in the introduction.

The discussion also may include suggestions for future research, or disclaimers and explanations of methodological errors made during the course of the experiment. These are not REQUIRED elements, however. Many of you wrote lab reports for classes, where these were required elements of the report. Here, they may be appropriate but may not be necessary. In any case, if they are included, they must be well integrated. They should not just sit there at the end of the discussion. Rather, they should be integrated into the body of the discussion, so that your discussion can end on a positive note - like the major conclusion of your study, or the new question that it raises. Don’t end on a negative about a shortcoming of your experiment.

G. Acknowledgments. Thank the people who helped you research the question, design or conduct the experiment, and review drafts. Also acknowledge any funding support, and the source (check a few acknowledgement sections for examples).

H. Literature Cited. This section contains bibliographical information on the references that were cited in the body of the paper. It is not a bibliography; only list the references that were actually cited in the body of the text. YOU SHOULD USE THE COUNCIL OF SCIENCE EDITORS “NAME/YEAR” CITATION FORMAT . If you are submitting the manuscript for publication in a journal that uses a different format, and you wish to prepare your paper in that format, include the citation format instructions from the journal in your submission to the committee.

II. Citing References in the Body of the Text

A. Citing an article by a single author: Research papers in the sciences use a simple format for alluding to work done by previous investigators. When you present information that you found in a published document, you cite the author and year of publication parenthetically, immediately after the information. For instance, suppose I was writing a paper on the effects of resource patchiness on community structure, and I read an article by J. Weins titled "Population responses to patchy environments" published in Annual Reviews of Ecology and Systematics in 1976. In this article, Weins states that foraging patch scale is determined by the perception of the organism searching for the resource, and is not an inherent quality of the resource. In my introduction, I might write: "However, the relevant spatial scales of predictability and ephemerality are defined by the perceptual and dispersal capabilities of the foraging organism ( Weins 1976)." (Note: the use of present tense implies a fact which must be supported by a citation or your data.) Cite only the author of the immediate information. If you are citing a chapter authored by Burgdorff in a text edited by Crane, cite: ( Burgdorff 1983).

B. Citing a direct quotation: You must cite all information that was published elsewhere and is not original to your paper. Preferably, you paraphrase the information and present the citation at the end of the sentence (as above). Sometimes, however, the phrasing of the original information is particularly eloquent. Or, sometimes you want to stress the authority of the source. In these cases, you want to quote the information exactly. You must enclose the quoted material in quotation marks: As Price (1984) stated, "it is noteworthy that so many of the hypotheses involve resources as the basis for understanding community organization, and that competition is not invoked as a major organizing influence"(p. 476). Use quotations sparingly! Sequences of direct quotations are difficult to read because the style keeps changing. It also suggests that you don't understand the topic well enough to interpret the information in your own words. This is especially true of conceptual material; when you quote something that is not particularly eloquent or authoritative, it suggests that you could not understand it well enough to paraphrase.

C. Citing a series of articles at once: Often, there are several citations that relate to a particular statement; simply list these in chronological order, separated by a semi-colon: "These resources often support diverse insect communities (Elton 1966; Heed 1968; Beaver 1977; Schoenly and Reed 1987), yet they are packaged into discrete units that are typically perceived as patchy and unpredictable (Lacy 1984)." Also, notice that the citations only accompany the clause that applies to them. Lacy (1984) did not suggest that these resources support unusually diverse communities so he is not cited after that clause. Obviously, citations can become cumbersome and can influence the structure of your sentence. If a long list of references comes between two clauses (as above), you might consider breaking the sentence in half. However, lots of short, single clause sentences are monotonous to read because they don't flow. Reading and rereading your drafts will help you recognize rough spots. Obviously, this can't be done overnight. You must give yourself ample time to write and rewrite your paper. A rough job will be noticed.

D. Citing several citations by the same author: If you have several citations and some are by the same author, group the citations by author, separating authors by semi-colons: ( Jaenike 1978a, 1978b, 1986; Lacy 1979).

Notice that Jaenike's complete list goes first, even though his citations are chronologically split by Lacy's article. Also, if you refer to two citations by the same author in the same year, refer to the first citation cited as 'a' and the second one 'b'. Do not use the 'a' and 'b' designations that other authors used; those were dependent upon their order of use.

E. Citing multi-authored works: If the citation has only two authors, present both their surnames followed by the publication date: ( Schoenly and Reed 1987). If there are more than two authors, cite the first author's name followed by the words 'et al.' and the year. The book Insects on Plants by D. R. Strong, J. H. Lawton and R. Southwood is cited in the text as: (Strong et al. 1976).

F. Citing unauthored pamphlets, etc.: Some government and corporate publications are unauthored . Cite these as 'anonymous', followed by the date of publication: (Anon. 1952).

G. Citing sources for equipment: If you are using an unusual piece of equipment or material from an exotic source, you can cite the source directly so that others trying to replicate your experiment can get the same material: "I counted the drosophilids and dusted the flies collected on each plot with a different color of micro-ionized fluorescent dust (USR Optonix , Inc., Hackettstown, NJ)."

H. Citing unpublished material: Suppose you want to cite a manuscript that has not been published. You would cite (Author, unpublished).

I. Citing personal communications: Suppose you want to cite an interpretation that someone else made regarding your data. You would cite (Author, personal communication). This situation may arise regarding a professor's lecture notes or a chat you had about your research. Be sure to get permission before citing the information.

III. Listing Citations in the Literature Cited Section

The complete citations of published work are presented in alphabetical order (by surname of first authors) in the Literature Cited section. Unpublished manuscripts (unless they are in press) and personal communications are not listed. The Literature Cited section follows your acknowledgments, and always begins on a new page. Consult this website for style: The Writer’s Handbook, University of Wisconsin – Madison .

IV. Tables and Figures

You should choose your tables and figures carefully; they will form the backbone of your results section and should present your results in a way that clearly describes the patterns in your data. Don't include figures and tables that are extraneous to your report. Every table and figure must be referred to somewhere in your paper. Also, only use tables and figures to summarize the patterns in large sets of data; do not include tables of raw data. If you are only comparing two responses, a descriptive sentence in the results section might be sufficient. Don't be redundant! Use either a table or a figure to summarize a particular pattern, do not use both. Tables and figures should be appended to the back of the report, after the Literature Cited section. Each table and figure should be presented on a different page. Table legends appear at the top of the table; figure legends are commonly presented on a separate page that precedes the figures. Also, do not use multiple colors on tables or figures; shades of black and white, with hatching or stippling, is best; some readers are colorblind and may not perceive the differences in colored bars. In addition, most journals will charge extra for color figures – so only use color when necessary, like in photographs of fluorescing tags.

Each table and figure must have a descriptive legend. The legend should be complete; the table/figure should be comprehensible without reference to the paper.

As such, you need to include:

- The independent and dependent variables and the method of manipulation.

- The species, site and date.