Lesson study as a research approach: a case study

International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies

ISSN : 2046-8253

Article publication date: 20 July 2021

Issue publication date: 23 July 2021

The purpose of this paper is to explore the merits of lesson study (LS) as a research approach for research in (science) education. A lesson was developed to introduce students to model-based reasoning: a higher order thinking skill that is seen as one of the major reasoning strategies in science.

Design/methodology/approach

Participants of the LS team were three secondary school teachers and two educational researchers. Additionally, one participant fulfilled both roles. Both qualitative and quantitative data were used to investigate the effect of the developed lesson on students and to formulate focal points for using the LS as a research approach.

The developed lesson successfully familiarized students with model-based reasoning. Three main focal points were formulated for using LS as a research approach: (1) make sure that the teachers support the research question that the researchers bring into the LS cycle, (2) take into account that the lesson is supposed to answer a research question that might cause extra stress for the teachers in an LS team and (3) state the role of both researchers and teachers in an LS team clearly at the beginning of the LS cycle.

Originality/value

This study aims to investigate whether LS can be used as a research approach by the educational research community.

- Biological models

- Higher order thinking skills

- Lesson study as a research approach

Jansen, S. , Knippels, M.-C.P.J. and van Joolingen, W.R. (2021), "Lesson study as a research approach: a case study", International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies , Vol. 10 No. 3, pp. 286-301. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLLS-12-2020-0098

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Susanne Jansen, Marie-Christine P.J. Knippels and Wouter R. van Joolingen

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

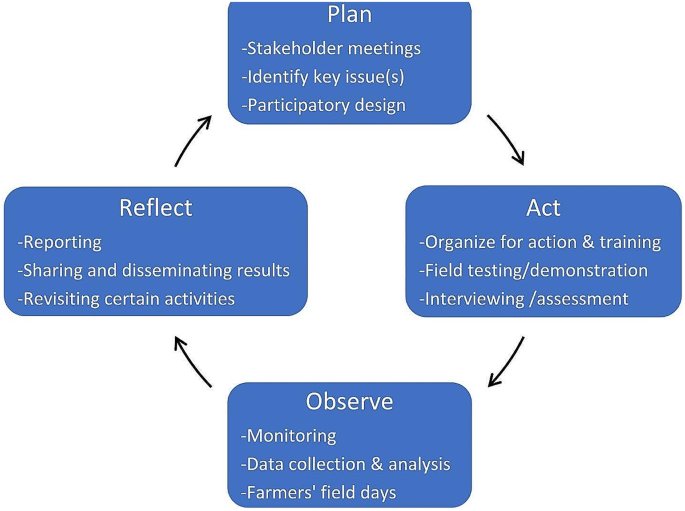

Lesson study (LS) is known as an approach in which a team of teachers collaborates to target an area of development in students' learning by designing, teaching, observing and evaluating lessons ( Fernandez and Yoshida, 2008 ). Studies have shown that classrooms provide powerful, practice-based contexts in which teachers learn ways to support student learning (e.g. Opfer and Pedder, 2011 ). Amongst other benefits, LS has been proved to make the teachers more aware of students' thinking processes ( Verhoef and Tall, 2011 ) and to enhance student learning (e.g. Ming Cheung and Yee Wong, 2014 ).

Since LS often focusses on teacher professional development, with teachers investigating their own practice, research on LS often has focussed on what teachers learn from LS (e.g. Schipper et al. , 2017 ; Vermunt et al. , 2019 ) or how LS can be implemented in schools (e.g. Chichibu and Kihara, 2013 ).

However, the cyclic nature of LS that allows for systematic refining of lessons might not just be beneficial for addressing topics arising from the LS team but could also benefit the study of specific problems prominent in existing bodies of educational research. Research approaches focussing on the design of teaching and learning activities in a cyclic fashion are often labelled design research of which multiple versions exist ( Bakker, 2018 ). Due to its cyclic nature and focus on teaching and learning, LS can be seen as a kind of design research. In the spectrum of design research, LS focusses on student learning and a strong involvement of teachers in the design process of lessons. This strong involvement of teachers allows them to integrate their experience and expertise into the design. The focus on student learning is, for instance, apparent in LS models used in the UK ( Dudley, 2015 ) and the Netherlands ( de Vries et al. , 2016 ), in which a number of so-called case-students are closely observed in each lesson and interviewed afterwards. This means that apart from student results from the whole class, detailed quotes, student behaviour and arguments are available for these case-students ( de Vries et al. , 2016 ). The large pedagogical and didactical contribution from teachers, and the amount of detailed data from the case-students resulting from an LS approach, can provide valuable insights for the research community.

A major challenge in science education is to foster students' higher order thinking skills ( Miri et al. , 2007 ). These skills are very difficult to capture, and LS might especially be a beneficial approach for research focussing on this area. LSs focus on observation of student learning may help studying students' reasoning processes. Teachers' pedagogical content knowledge can help in the design of activities that make students' reasoning abilities visible, allowing researchers to study the resulting data on student learning.

To explore whether LS has potential as an approach addressing research questions on higher order thinking, we present a case study in which LS is used as a research approach to develop teaching and learning activities that address the higher order thinking skill of model-based reasoning . Model-based reasoning entails the understanding of the nature and use of scientific models as a basis for scientific knowledge. In science education research, model-based reasoning is seen as one of the major reasoning strategies that is part of scientific literacy ( Windschitl et al. , 2008 ). In this study, we focus on a particular kind of model that is often used in biology: concept-process models. Concept-process models visualize biological processes such as an image showing the process of cellular respiration. These concept-process models are perceived as the most complex type of models in biology education ( Harrison and Treagust, 2000 ). Unlike scale models or visual depictions of a certain biological phenomenon, concept-process models have a very abstract nature. They include the inherent dynamics of biological processes, such as time and movement, which are often visualized by arrows ( Jansen et al. , 2019 ). Figure 1 shows an example of a biological concept-process model that is used in biology education, in which the light reaction of photosynthesis is depicted. The light reaction is the first part of photosynthesis, in which energetic molecules are formed that are necessary in the process of creating glucose. The formation of glucose takes place in the second part of photosynthesis, called the Calvin cycle.

The dynamics that biological concept-process models can represent make this type of model ideal for learning about scientific processes. They can be used not only to explain phenomena but also to formulate hypotheses or carry out thought experiments ( Windschitl et al. , 2008 ).

Aspects of model-based reasoning

A framework developed by Grünkorn et al. (2014) and adapted by ( Jansen et al. , 2019 ) shows five important aspects of model-based reasoning that reflect on understanding and using models in science ( Table 1 ). The five aspects within this framework are as follows: nature of models, purpose of models, multiple models, testing models and changing models.

The aspects nature of models and multiple models include the way models are used to describe and simplify phenomena. Nature of models focusses on the extent to which the model can be compared to the original, whereas the aspect multiple models refers to the fact that various models can be used to represent the same original. Both aspects show that models are often simplified and emphasize only those elements that are important to explain a certain key idea ( Harrison and Treagust, 2000 ). The aspects purpose of models, testing models and changing models focus on the use of models in scientific practices. These include testing hypotheses, making predictions about future events and communicating ideas ( Grosslight et al. , 1991 ). With the aspect purpose of models , the framework focusses on aims that can be met using a certain model. Testing and changing models describe the way a model is being validated and stress the fact that models are by definition temporary and changeable. For all these aspects, up to four levels of understanding have been determined, ranging from an initial level of understanding to an expert “scientific” level of understanding (Level 3).

Aim of the study

To what extent does the developed lesson successfully familiarize students with important levels and aspects that are associated with model-based reasoning?

How do teachers and researchers experience using LS as a research approach?

Participants

Three biology teachers (18, 30 and 9 years of experience; one male, two female) from the same secondary school, two researchers (second and third author) and the first author who is both a researcher and a secondary school biology teacher with eight years of experience participated in an LS team. The lesson was performed and observed in two 11th-grade pre-university biology classes from the Netherlands. In total, 34 students (16–18 years old, 18 female, 16 male) engaged in all scheduled activities.

RQ1 : Pre- and post-tests

Online pre- and post-tests were developed to determine up to which level the lesson familiarized students with the three aspects of model-based reasoning ( nature of models, purpose of models and multiple models ). Both tests contained the same nine open-ended questions, where students had to formulate a definition of a model in biology and answer questions relating to the aspects nature of models (two questions), purpose of models (three questions) and multiple models (three questions). An example of a question relating to the aspect purpose of models is as follows: “Before a biological model is made, the creator of the model thinks about what the model will be used for. Indicate a possible purpose of the model below.” A translated list of all questions is available in the Supplementary material . The pre-test took place in the biology lesson preceding the developed lesson and the post-test in the biology lesson following the developed lesson.

RQ1 : Interviews – case-students

The six case-students, three for each version of the lesson, were interviewed after the lesson using a semi-structured interview scheme. The questions as proposed by de Vries et al. (2016) were used: Students were asked about what they liked about the lesson; what they learnt from the lesson; what they thought worked well in the lesson and what they would change about the lesson if this lesson would be taught again to a different class. Interviews were recorded and lasted 5–10 min.

RQ2 : Interviews – teachers

The three teachers who participated in the LS team were interviewed after the completion of the LS cycle using a semi-structured interview scheme to evaluate what the main focal points are when using LS as a research approach. Interviews were recorded and lasted approximately 40 min. The interview questions related to the expectations the teachers had before starting the LS cycle and to what extent these expectations were met; what they thought went well during the LS cycle and what not; what they learnt from participating in an LS cycle; the extent to which they applied what they learnt to other lessons or their teaching and whether they expected to keep on using what they had learnt in the long term.

RQ2 : LS meetings

The LS cycle started with an introduction on model-based reasoning by the researchers to the teachers in the LS team. A 45-min lesson was then designed in three 2-h meetings within a time frame of two weeks. The LS team evaluated both the designed and the adapted lesson in a 1-h meeting. All meetings were audio-recorded.

Data analysis

Students’ answers on the pre- and post-tests were coded using the three aspects of interest and their corresponding levels as described in the framework from Grünkorn et al. (2014) as codes. Possible students’ answers for the aspect purpose of models are as follows:

Level 1: To show the different parts of a plant

Level 2: To indicate what relationships are present between this process and other processes

Level 3: To display the process of fertilization, after which the researcher can use the model to do research on the process

About 50% of the answers were coded by a second independent coder, resulting in a Cohen’s kappa of 0.69 for nature of models , 0.87 for purpose of models and 0.63 for multiple models . Students’ answers in the audio recordings were tagged when utterances related to aspects that were learnt from the lesson. Tagged answers were grouped according to the three aspects of focus and three levels of reasoning. Student material was tagged for utterances relating to the three levels for each of the three model-based reasoning aspects.

To learn from the experience of using LS as a research approach, the audio recordings from both the teacher interviews and the LS meetings were tagged for utterances relating to elements that worked well and for elements that needed improvement. Audio tags were grouped into these two categories.

Lesson design – the design process

After the theoretical introduction by the researchers, the first LS meeting was used to decide on the curriculum topic for the lesson and the models to be used in that lesson. The second LS meeting focussed on formulating key activities that let students reflect on the aspects within the framework ( Table 1 ) that the team wanted to get students acquainted with. During the third LS-meeting the LS-team decided on the three case-students that would be observed in detail during each performance of the lesson and on predicting the learning behaviour of these students.

In selecting the case-students, the LS team made use of the expertise of the teachers and their knowledge about the students. Since the levels in Table 1 represent an increasing degree of difficulty, the LS team assumed that students, who were able to reason on Level 3, would also be able to reason on Levels 1 and 2. Therefore, teachers were asked to define for every student whether they thought the student would have a high chance, an intermediate chance or a low chance of reaching Level 3 for the aspects as described in the framework. They also indicated which of these students would be explicit in their arguments, making it easier to follow their way of reasoning during the lesson. Students were placed in homogenous groups of four students, based on this classification. From three groups, a case-student was selected. For each case-student, an observation scheme was created, listing their predicted behaviour during each phase of the lesson. For each case-student, a backup student was chosen and an observation scheme was formulated, in case one of the selected students would not attend the lesson. Using the observation scheme, case-students were observed by members of the LS team.

The reason students were placed in homogenous groups was mostly pragmatic. Each observer was stationed next to a group of students of whom the teachers expected certain behaviour. The observer could remain seated next to this group of students and observe the backup case-student in case the selected case-students did not attend the lesson.

One of the teachers from the LS team taught the lesson. Discussions that took place in the student groups containing case-students were audio recorded, and the work of every student was collected. After teaching the lesson for the first time to one of the biology classes, the lesson was discussed with the LS team, and improvements were formulated. The adjusted lesson was taught 1 week later by the same teacher in a different biology class.

Lesson design – aspects of focus

The LS team decided to focus on three of the five aspects listed in Table 1 and to design a key activity for each of these three aspects. The teachers indicated that time was an important factor to take into account. The lesson duration of 45 min was considered to be too short to properly introduce all five aspects. Since the aim of this study was to introduce aspects that are important when reasoning with existing biological concept-process models, the researchers in the LS team explained that the aspects nature of models, purpose of models and multiple models would be the aspects of choice when creating the lesson . These aspects are central to understanding the given models and are important when reasoning with these models, such as the ones students encounter in their textbook. The aspects testing models and changing models are of importance when a model is created, tested or modified .

Lesson design – pedagogical choices

The LS team made various pedagogical choices considering the design of the lesson. These choices were mostly based on teachers' pedagogical knowledge and experience and discussed with the researchers in the team, who searched for literature backup.

The teachers decided on photosynthesis as the subject of the lesson since many models about photosynthesis are available for educational contexts. Also, this topic was recently taught in class, and, according to the teachers, this allowed for focussing on the model-based aspects and not on the content domain. This choice is in line with literature on this topic, showing that students need domain knowledge before they are able to create their own mental model of a process (e.g. Cook, 2006 ) or interpret given scientific models (e.g. Tasker and Dalton, 2007 ).

In order to engage students with the lesson and theory about the aspects of model-based reasoning, the teachers in the LS team wanted students to work with these aspects themselves before explaining the theory. According to the teachers, just explaining or showing the theory to the students would put the students in “consumer-mode.” An inductive approach, where students have to think about the theory themselves first, would engage the students and make them curious for answers. This choice is backed up by research showing that inquiry-based learning stimulates scientific reasoning and helps students to gain confidence in their scientific abilities ( Gormally et al. , 2009 ).

To provide insight in student thinking, the teachers decided that the developed key activities should stimulate students to work together and talk out loud during the lesson. Research shows that talking out loud is not only beneficial for providing insight in student thinking but also promotes student thinking about what they understand and what not, thereby improving metacognition ( Tanner, 2009 ). Also, working in groups can improve student performance in general and aid in learning ( Smith et al. , 2009 ).

Lesson design – resulting key activities

The pedagogical and didactic choices that were formulated by the LS team were incorporated into three key activities.

In Key activity 1, students focussed on the aspect multiple models . Students were asked to individually name differences between four models that showed the same biological process (photosynthesis) ( Figure 2 ). These differences were then shared in groups of four students, after which the group categorized the differences. The teacher then linked these categories to the levels as represented in the framework ( Table 1 ).

In Key activity 2, students matched aims of a model to the four models of photosynthesis. This activity corresponds to the aspect purpose of models. The aims were provided by the teacher and were formulated according to the three levels as described by the framework ( Table 1 ). In order to stimulate discussion and have students substantiate their choices, they were only allowed to match an aim with one of the models when everyone in their group agreed on this choice. The teacher then discussed the results and explained how the aims related to the three levels as described by the framework.

In Key activity 3 relating to the aspect nature of models , students were assigned to one of the four models. Students had to formulate the choices that the creator of the model had made to meet the aims. They also indicated which components of the model were drawn in a true to nature way and which were not. Afterwards, the teacher linked students' choices to the levels as described by the framework and explained how these choices relate to these levels.

Figure 3 summarizes the design process and shows the contributions of both teachers and researchers to the final lesson design.

After teaching the lesson for the first time to one of the biology classes, the lesson was discussed in the LS team. Only a minor adjustment was made, the four models of photosynthesis were numbered (1–4) before teaching the adjusted lesson.

Influence on students' reasoning

LS1B1: I thought it was very interesting. It was a different way of looking at the theory. When you learn to look at the theory in this way, you will understand it better. I really feel that way.

LS1A1: Well, we formed a group [of differences] about content, so what is visible in the image, or how much is being shown. In one of the pictures for example you can also see the Calvin cycle and in the other picture you cannot. And we have [a group of differences] about what the image is meant for. For example, the one with the small guys in it [ Figure 2c ]. In that one the focus is only on the levels of energy of the electrons. And then we also have [a group] with visual differences, which is about the fact that some images have been drawn in a more realistic way than others.

In this case, the group of differences about “content” and the group of differences about “what the image is meant for” both relate to Level 2 for the aspect multiple models , since they address the differences in focus between several models. The group with “visual differences” relates to Level 1 for the aspect multiple models , since it addresses different model object properties.

L1B1: Shall I read the aim out loud?

L1B2: Yes, that way we can think about it together

L1B1: To show that electrons are released when water is splitted.

L1B3: I think that's this one, because it clearly shows that water is splitted [pointing at the model in Figure 2d ].

L1B4: Yes, but you can see that in this model too. And in this one [pointing at the models in Figures 1a and 2b ]!

L1B2: Yes, but I think it should be the one where the focus of the model is on splitting water.

L1B1: Well, this model really emphasizes the presence of electrons, you can literally see two electrons appearing [pointing at the model in Figure 2d ].

L1B4: Yes, but you can also see that in the other models

L1B3: Yes, but the emphasis is less on the process of splitting water.

L1B1: Ok, so let's go with this one, because the emphasis of the model is on the splitting water part and on what the electrons do, the other parts of the process are less prominent [points at the model in Figure 2d ].

L1C1: If you take it literally, I do not think that there is someone using the hammer in real life.

L1C4: It is very schematic

L1C1: I think it's a choice to meet the aim by only showing a part of the reaction

L1C3: Yes, simplifying it

L1C4: Yes, focusing on a specific part of the reaction, showing that part.

The aim of the model in this case was “to show that energy is necessary to let the light reaction take place.” The students explain that by simplifying the model, the focus is on that part of the process.

Considering the pre- and post-tests, no significant differences in students' level of reasoning for each of the three aspects of focus were found. Table 2 summarizes the changes in student levels on the different aspects of model-based reasoning.

Teachers' experience

T2: Making the role of models more explicit, that is something I will handle differently from now on. I would assume it to be less clear for students. And I think I would start with that when we use models in lower secondary education, saying “this has been visualized in this way, which is a choice of the creator of the model.”

T2: In most biology lessons we use models as an illustration, to explain a certain biological phenomenon. In this lesson the model itself will be the subject of the lesson. I think we need to let students think about the nature of a model and the differences between multiple models of the same biological process.

T3: It's a good thing to critically discuss how to teach students about a certain subject. Together you will hear and see more perspectives than when you develop a lesson by yourself. We formulated a goal for the lesson and discussed how we could achieve the desired results. And everyone [in the LS team] has different ideas about that. These are probably all good ideas, but because you discuss them together, the final idea will be different from your own initial idea. And because you critically look at the ideas together, the final idea will be better.

T1: We could definitely use this method [LS] again, but perhaps I would prefer developing a lesson series instead of a single lesson. It really costs a lot of time. I look at LS as a good method to develop complete projects for example.

T2: I liked thinking upfront about what actions a certain student would undertake. It really makes you think about that specific student and whether you can predict for this student what will happen. That influences the way you teach as well. You start to behave in a certain way, because you really want things to work out the way you thought they would. And you especially want to make sure that the results could be measured.

T2: Teaching the lesson was such a strict process for me! We agreed on a certain amount of time per element within the lesson. That is really different from the way I usually teach, where I am more concerned with how the students respond, and where I adapt my teaching to their response. Now I had to do exactly what it said in the script, which meant I kept on looking at my watch. I really struggled with that, because I was afraid that the students would not get the point if I was not able to finish all elements within that lesson. During a normal lesson I would think, that's ok, and I would continue with the theory the next lesson. Now it's just one single lesson and there are observers and we do a test, so everything needs to be finished. That caused a lot of pressure, it felt unnatural.

While LS originally mainly focusses on teacher professional development, we used LS as a form of design research ( Bakker, 2018 ) to develop a lesson that addresses a problem that arises from the existing body of research and relates to higher order thinking skills. In this case study, we followed the LS cycle as described by de Vries et al. (2016) to design a lesson containing three key activities that introduce main aspects of model-based reasoning ( Table 1 ). We combined pedagogical and didactic knowledge and experience of teachers with theoretical knowledge to develop a lesson that answers the researchers' question on how to address model-based reasoning as a higher order thinking skill in class.

The influence the teachers and researchers had on the design of the lesson in this case study differs from the influence teachers have in a regular LS cycle ( Figure 3 ). In this study, the researchers were the ones introducing the subject for the lesson (model-based reasoning). As in a regular LS cycle, the teachers then developed the lesson and used their knowledge and experience to make pedagogical and didactic choices. However, different from a regular LS cycle, the researchers reflected on whether the teachers' choices were in line with theory from literature and whether the developed activities reflected the subject that the researchers had intended. The researchers were also responsible for developing the pre- and post-tests to determine whether the lesson affected students' level of model-based reasoning.

Considering our first research question, we found that after the lesson, all case-students were capable of reasoning on multiple levels for the aspects nature of models, purpose of models and multiple models. These results indicate that all case-students understood the meaning of the three aspects of model-based reasoning and were able to work with these aspects on different levels of reasoning.

The pre- and post-tests showed that student levels of reasoning did not significantly change for any of the three aspects of focus. However, the open structure of the questions in the pre- and post-tests invited students to answer on their preferred level of reasoning. This means that even when students were capable of reasoning on multiple levels as shown in Table 1 , the test offered the possibility to only answer on the level they preferred. Therefore, the pre- and post-tests probably indicate the students' preferred level of reasoning instead of their highest capable level of reasoning. Despite this lack of increase in students' preferred level of reasoning, the qualitative data showed that all case-students were able to reason on multiple levels for each of the three aspects of focus. Considering our first RQ, we, therefore, conclude that the results indicate that the developed lesson successfully familiarized students with main aspects of model-based reasoning. However, future research should focus on developing lessons to deepen students' understanding on this subject and on developing a test to assess the students' capability of reasoning on all levels separately for each of the main aspects of model-based reasoning.

Considering RQ2 , using LS as a research approach was appreciated by the teachers. The teachers enjoyed being part of the LS team and thought it was a productive way to develop lessons, stimulate creativity and increase team spirit. All teachers mentioned that the theory about model-based reasoning was an eye-opener to them, which not only influenced their own way of reasoning with models but also the way they intended to work with models in their future lessons.

However, results from the teacher interviews show that teachers experience one downside of being part of the LS team, time. In this case, the factor time did not only apply to how long it took to develop the lesson but also to the strict schedule that was set up for the lesson. The teacher who taught the lesson reported pressure on performing the lesson precisely according to this schedule as he or she felt this was necessary to answer the research question of the researchers.

Since we as authors fulfilled the role of researchers, it was not possible to objectively investigate the experience of the researchers in this case study. However, we can say that as researchers, we felt positive about being part of the LS team and about using LS as a research approach. Since the teachers designed the lesson, making pedagogical and didactic choices, the role of the researchers was mainly to inform the teachers about the theoretical background and check whether the choices that the teachers made were backed up by research. We found that this approach, in combination with the teachers' important role in observing and evaluating the lesson, led to increased ownership for the teachers. Also, as researchers, we felt that the practical and pedagogical knowledge and experience from the teachers added value to the developed lesson, while the theoretical knowledge that we shared with the teachers added value to the teachers' way of teaching. In our experience, this exchange in knowledge improved the lesson design and served as an example of a possible way to sustainably incorporate theoretical knowledge from the educational research community into the classroom.

As mentioned in the method section, the LS team consisted of three teachers, two researchers and a third researcher who was also a teacher. This third researcher fulfilled tasks both as a researcher and as a teacher, functioning as a bridge between the researchers and the teachers, contributing both theoretically and practically. Future research is necessary to find out whether the separation in tasks as described in Figure 3 also works well when the LS team does not contain a member who is both a researcher and a teacher.

Our results suggest a number of focal points that should be taken into account when using LS as a research approach. First of all, it is important to make sure that the teachers support the research question that the researchers bring into the LS cycle and that they are invested in designing lessons that answer this research question. This differs from the regular LS approach, where the teachers are the ones who decide on the subject of the lesson, making them naturally more aware of the need to work on this subject. To increase the teachers' support in answering the research question, we would therefore advise to extensively discuss the subject that the researchers bring to the LS cycle. Also, as shown in previous research (e.g. Wolthuis et al. , 2020 ), exploring possibilities to facilitate teachers and making sure that they have time to work on designing the lessons can help to increase teachers' investment.

Second, it is important to take into account the fact that the lesson is supposed to answer a research question can cause extra stress for the teachers. As shown in this case study, teachers could feel like they have to perform well because they would otherwise hinder the research or that not performing well would place an extra burden on the researchers who observe the lesson. Adding extra cycles to the LS approach might solve this problem. That way both the lesson and the way of teaching can be reviewed multiple times, making the teachers more comfortable with teaching the lesson. In this case study, the teacher who taught the lesson indicated that he already felt more comfortable the second time he taught the lesson.

Third, it is important to be clear about the role of both the teachers and the researchers in the LS team. That way both the teachers and researchers share responsibility for the lesson plan. As shown in this case study, the teachers' sense of ownership considering the lesson design led to a product that was created by the whole team, of which they were proud. This is in line with results from Dudley et al. (2019) who show that teachers in an LS team experience a high degree of ownership while collectively trying to understand how students navigate curricular pathways and pedagogies.

This case study provides an exemplar for how LS can be used as a research approach. We believe LS is a promising approach to bring the pedagogical and didactic knowledge and experience from teachers and the theoretical knowledge from the educational research community together and might thereby contribute to bridging the gap between theory-driven research and educational practice.

A concept-process model of the light reaction of photosynthesis. Reprinted and translated with permission from Noordhoff Uitgevers, Groningen ( Brouwens et al. , 2013 )

The four models of the light reaction of photosynthesis that were used in the developed lesson

Contributions of the teachers and the researchers to the lesson design. The contributions from the teachers are visualized in light grey. The contributions from the researchers are visualized in white. The arrows show interactions between the researchers, teachers and the lesson design. The dotted arrow shows a possible adaptation moment to the lesson design. In this case study, these possible adaptations have been discussed but have not been applied to the lesson design since the lesson would not be taught a third time. The figure can be read as a timeline from left to right

Framework to assess students' understanding of biological models. The left column shows the five aspects that are important when reasoning with biological models. For each of these aspects up to four levels of understanding have been defined, ranging from an initial level of understanding to an expert level of understanding ( Jansen et al., 2019 )

Comparison of the pre- and post-tests

Note(s) : The three aspects of interest are shown in the left column. The table shows for each of the two biology classes how many students ( n ) decreased in level of reasoning, showed no change in level of reasoning, or increased in level of reasoning

Supplementary material List of translated questions from the pre- and post-tests

Models are often used in biology. Below you find three examples of biological models. Can you formulate a definition for a biological model?

[three models: a scale model of a human eye, a model (drawing) of a cell, a model (drawing) of the process of pollination]

Every biological model is made with a certain purpose. Name two or three reasons (purposes) for creating a model of a biological phenomenon.

Before the model below was made, the creator of the model first decided on the purpose that this model would serve. Indicate for the model below what you think is the purpose for which this model was created.

[model of the process of pollination]

To what extent does this model correspond to the original, real world situation? Explain your answer.

To meet the purpose as described in Question 3, the creator made specific choices while creating this model. Describe a minimum of three choices that were made by the creator of the model to meet this purpose.

Can this model also be used for a different purpose? If so, give one or two examples of such purposes.

Often multiple models about the same biological process exist. What could be a reason for the fact that multiple models about the same process exist?

When multiple models about the same biological process exist, is in that case per definition one model better than the other? Explain your answer.

The existence of both of these models is important

One of the models is better/more useful than the other

It would be good to combine both models and create one ultimate model

[two models about the process of protein synthesis, both with a different focus: one model focussing on the binding of the anticodon on tRNA to the codon on mRNA, and one model focussing on the movement of ribosomes along the mRNA]

Questions relating to the aspect:

Nature of models: 4, 5

Purpose of models: 2, 3, 6

Multiple models: 7, 8, 9

Bakker , A. ( 2018 ), Design Research in Education: A Practical Guide for Early Career Researchers , Routledge , Abingdon .

Brouwens , R. , de Groot , P. and Kranendonk , W. ( 2013 ), BiNaS , 6th ed ., Noordhoff , Groningen .

Campbell , N.A. and Reece , J.B. ( 2002 ), Biology , 6th ed. , Pearson Education , New York, NY .

Chichibu , T. and Kihara , T. ( 2013 ), “ How Japanese schools build a professional learning community by lesson study ”, International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies , Vol. 2 , pp. 12 - 25 .

Cook , M. ( 2006 ), “ Visual representations in science education: the influence of prior knowledge and cognitive load theory on instructional design principles ”, Science Education , Vol. 90 , pp. 1073 - 1091 .

de Vries , S. , Verhoef , N. and Goei , S.L. ( 2016 ), Lesson Study: Een Praktische Gids Voor Het Onderwijs [Lesson Study: A Practical Guide for Education] , Garant Uitgevers , Antwerpen .

Dudley , P. , Xu , H. , Vermunt , J.D. and Lang , J. ( 2019 ), “ Empirical evidence of the impact of lesson study on students' achievement, teachers' professional learning and on institutional and system evolution ”, European Journal of Education , Vol. 54 , pp. 202 - 217 .

Dudley , P. ( 2015 ), Lesson Study, Professional Learning for Our Time , Routledge , Abingdon .

Fernandez , C. and Yoshida , M. ( 2008 ), Lesson Study: A Japanese Approach to Improving Mathematics Teaching and Learning , Lawrence Erlbaum Associates , Mahwah, New Jersey .

Gormally , C. , Brickman , P. , Hallar , B. and Armstrong , N. ( 2009 ), “ Effects of inquiry-based learning on students' science literacy skills and confidence ”, International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning , Vol. 3 , p. 16 .

Grosslight , L. , Unger , C. , Jay , E. and Smith , C.L. ( 1991 ), “ Understanding models and their use in science: conceptions of middle and high school students and experts ”, Journal of Research in Science Teaching , Vol. 28 , pp. 799 - 822 .

Grünkorn , J. , Upmeier zu Belzen , A. and Krüger , D. ( 2014 ), “ Assessing students' understandings of biological models and their use in science to evaluate a theoretical framework ”, International Journal of Science Education , Vol. 36 , pp. 1651 - 1684 .

Harrison , A.G. and Treagust , D.F. ( 2000 ), “ A typology of school science models ”, International Journal of Science Education , Vol. 22 , pp. 1011 - 1026 .

Jansen , S. , Knippels , M.C.P.J. and van Joolingen , W.R. ( 2019 ), “ Assessing students' understanding of models of biological processes: a revised framework ”, International Journal of Science Education , Vol. 41 , pp. 981 - 994 .

Ming Cheung , W. and Yee Wong , W. ( 2014 ), “ Does lesson study work? ”, International Journal for Lesson and Learning Studies , Vol. 3 , pp. 137 - 149 .

Miri , B. , David , B.C. and Uri , Z. ( 2007 ), “ Purposely teaching for the promotion of higher-order thinking skills: a case of critical thinking ”, Research in Science Education , Vol. 37 , pp. 353 - 369 .

Opfer , V.D. and Pedder , D. ( 2011 ), “ Conceptualizing teacher professional learning ”, Review of Educational Research , Vol. 81 , pp. 376 - 407 .

Schipper , T. , Goei , S.L. , de Vries , S. and van Veen , K. ( 2017 ), “ Professional growth in adaptive teaching competence as a result of Lesson Study ”, Teaching and Teacher Education , Vol. 68 , pp. 289 - 303 .

Smith , M.K. , Wood , W.B. , Adams , W.K. , Wieman , C. , Knight , J.K. , Guild , N. and Su , T.T. ( 2009 ), “ Why peer discussion improves student performance on in-class concept questions ”, Science , Vol. 323 , pp. 122 - 124 .

Tanner , K.D. ( 2009 ), “ Talking to learn: why biology students should be talking in classrooms and how to make it happen ”, CBE Life Sciences Education , Vol. 8 , pp. 89 - 94 .

Tasker , R. and Dalton , R. ( 2007 ), “ Visualizing the molecular world – design, evaluation, and use of animations ”, in Gilbert , J.K. , Reiner , M. and Nakhleh , M. (Eds), Visualization: Theory and Practice in Science Education , Springer , Dordrecht , pp. 103 - 131 .

Verhoef , N.C. and Tall , D.O. ( 2011 ), “ Lesson study: the effect on teachers' professional development ”, 35th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education (PME) , Ankara, Turkey , 10-15 July 2011 .

Vermunt , J.D. , Vrikki , M. , van Halem , N. , Warwick , P. and Mercer , N. ( 2019 ), “ The impact of Lesson Study professional development on the quality of teacher learning ”, Teaching and Teacher Education , Vol. 81 , pp. 61 - 73 .

Windschitl , M. , Thompson , J. and Braaten , M. ( 2008 ), “ Beyond the scientific method: model-based inquiry as a new paradigm of preference for school science investigations ”, Science Education , Vol. 92 , pp. 941 - 967 .

Wolthuis , F. , van Veen , K. , de Vries , S. and Hubers , M.D. ( 2020 ), “ Between lethal and local adaptation: lesson study as an organizational routine ”, International Journal of Educational Research , Vol. 100 , 101534 .

Acknowledgements

This paper and the research behind it would not have been possible without the exceptional support of the teachers from the Lesson Study team: Harm Lelieveld, Willemien Hollander and Marieke van Klink. The authors would also like to thank the school Gymnasium Novum and its students for their cooperation in this research.

Funding: This work was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek, NWO) [grant number 023.007.065].

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, the impact of observers’ beliefs on the perceived contribution of a research lesson.

- 1 Experiential Learning Office–Engineering Faculty, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 2 CIAE, Institute of Education, University of Chile, Santiago, Chile

Recently, Lesson Study (LS) has gained popularity in countries worldwide because of its potentially positive effects on teachers’ practices (e.g., reflection, cooperation, and pre-service development) and students’ learning. However, despite global interest in LS’s implementation, an important gap exists between Japanese LS and its implementation in other countries, which may be due to several reasons, such as differences in culture and educational systems or teachers’ beliefs. In this study, we examined the effect of teachers’ beliefs on their evaluation of LS in Chile. We administered a questionnaire to 94 teachers who participated in the Research Lesson (RL) as observers. The questionnaire assessed teachers’ beliefs and RL’s contributions to knowledge of the subject matter, instructional strategies, monitoring skills, lesson planning, and student understanding. Using a stepwise logistic regression, after controlling for sex and occupation, we found that the observers’ beliefs influenced their perceptions of RL’s contributions to monitoring, assessment, and instruction. Participants with student-focused beliefs were more likely to find that RL contributed to their monitoring skills and ability to assess students’ understanding of content. The results regarding instructional strategies were mixed. Our findings can help devise strategies to increase the effectiveness of LS implementation. For example, by designing two types of LS, one adapted to teachers with student-focused teaching beliefs and the other to teacher-focused teaching beliefs. To the best of our knowledge, this dual strategy is not part of LS implementation, at least in Chile. LS teams could easily explore this dual strategy, which could improve teachers’ professional development.

1 Introduction

Lesson Study (LS) began in 1880 in Japan with the goal of reproducing the best practices in teaching ( Isoda, 2015 ) and is a collaborative teaching improvement process designed to build strong and productive communities of teachers who share and learn from each other. Many countries have introduced this methodology ( Fujii, 2014 ). Evidence indicates that LS accelerates the production of effective lessons and, in particular, helps develop open-ended approaches with lessons that aim to develop higher-order skills ( Inprasitha, 2015 ). Additionally, Vermunt et al. (2019) concluded that the LS approach to pedagogical development fosters meaning-oriented teacher learning, which can be explained by LS’s strong focus on analyzing and understanding pupils’ learning. In particular, teachers in schools implementing LS have reported more meaning- and application-oriented learning than teachers from schools without LS experience ( Vermunt et al., 2019 ).

Enhancing the dissemination and awareness of LS’s benefits is important, as Chokshi and Fernandez (2004) found that schools allocate time for LS initiatives once teachers recognize the potential of LS. The potential benefits of LS include various pedagogical aspects and students’ learning outcomes. Researchers have studied numerous different effects of LS, including teachers’ increased self-efficacy ( Mintzes et al., 2013 ; Schipper et al., 2018 ; Vermunt et al., 2019 ), teachers’ content knowledge ( Fernandez and Robinson, 2006 ; Lewis and Perry, 2014 ; Juhler, 2016 ), teaching practices and teachers’ skills ( Fernandez and Robinson, 2006 ; Fernandez, 2010 ; Vermunt et al., 2019 ), teachers’ beliefs ( Fernandez and Robinson, 2006 ; Lewis and Perry, 2015 ; Yakar and Turgut, 2017 ) and pre-service teachers’ preparation ( Marble, 2006 , 2007 ; Suh and Fulginiti, 2012 ). In Chile, there used to be funds to implement this methodology, but due to a significant funding reduction, only a few institutions continue to work with the methodology ( Estrella et al., 2018 ).

However, a notable gap in the implementation of LS exists between Japan and other countries owing to divergent cultures and educational systems. Countries implementing LS outside of Japan have been found to not fully capture its key components ( Fujii, 2014 ). For instance, in the US, most LS teams do not share their learning with their peers, losing the opportunity to share and discuss their experiences with their educational community ( Whitney, 2020 ). Similarly, in England, Seleznyov (2020) reported that LS practices were diluted over time and identified various impediments, such as a lack of time and excessive teacher workload, a focus on demonstrating short-term impact, and a lack of teacher research skills. Additionally, Godfrey et al. (2019) found that engagement and reported learning decreased when teachers in England had to commit their own time to the LS process.

1.1 Research lessons

Research lessons (RLs) are critical to LS, which involve teachers coming together to observe and discuss lessons. Some benefits of RLs include opportunities for teachers to observe experienced teachers as a form of modeling their own learning experiences. RLs provide valuable examples of meaningful curricula and standard discussions, encouraging teachers to align their teaching with policy- and research-based recommendations ( Lumpe et al., 2014 ). Furthermore, Dudley et al. (2019) studied the implementation of RLs in mathematics within a school system in England and concluded that by focusing on student learning and recursive cycles of LS, teachers could develop the curriculum and raise standards while supporting the creation of the necessary conditions for learning. This transition to a student-centered education was also part of a two-year project in which teachers focused on students’ mathematical reasoning and sense-making rather than on other teacher actions or teaching ( Wessels, 2018 ).

Another potential benefit of RLs is teacher dialogue, consisting of more meaningful reflections. During the implementation of RLs in Ireland, teachers engaged in meaningful dialogues about pedagogy and student learning, fostering deeper levels of reflection on their understanding and practice knowledge ( McSweeney and Gardner, 2018 ). Similarly, a study in Singapore concluded that after four RLs and discourse analyses, a balance was achieved in mathematical representation while escalating the construction of meaning-making ( Fang et al., 2019 ).

Nonetheless, the field’s understanding of RLs remains limited, especially regarding methods of sharing work with others. Whitney (2020) examined cases of LS teams in the US and found that most LS teams did not distribute their learning to the field. Individuals external to the team observed the RL and engaged in subsequent post-lesson discussions.

This study has two objectives. First, we gathered the evaluations of observers outside the LS team when they attended an RL in Chile. Second, we examined how observers’ beliefs affected their evaluation of RL. Thus, our research question (RQ) was, “To what extent do teachers’ beliefs affect the perceived contributions of an RL in the context of an LS process?”

1.2 The Chilean context and teachers’ predisposition to observation

Our first study aim was to gather the evaluations of observers attending an RL in Chile. Participation as an observer in an RL may share similarities with teachers’ own evaluation processes, particularly in the context of observing pedagogical practices and sharing best practices with peers. Potential apprehension could exists among educators because of the history of teacher performance evaluations in Chile. This subsection briefly describes the historical perspective of the Chilean teacher evaluation system.

Chile’s experience with teacher performance evaluation is distinctive, particularly considering its past political developments. During Chile’s dictatorship (1973–1989), the teaching profession experienced a significant weakening, resulting in a substantial unemployment rate among teachers. Following the return to democracy in the 1990s, concerted efforts were made by the national government, in collaboration with teachers’ unions, to rectify the adverse consequences of past politics ( Avalos and Assael, 2006 ; Assaél and Cornejo, 2018 ).

One contentious aspect of these remedial efforts was the introduction of an annual grading system exclusively within public schools (municipality-dependent), which has frequently been perceived as punitive and arbitrary by educators ( Avalos and Assael, 2006 ; Taut et al., 2011 ; Assaél and Cornejo, 2018 ). Despite some modifications over the years, the prevailing sentiment among teachers was that these evaluations remained unjust and were penalizing. Moreover, these evaluations impose additional work burdens on teachers, exacerbated by the prevailing practice of unpaid overtime among educators in Chile. This evaluation is referred to as the “Teaching Evaluation” and is mandated by law.

In 2016, a significant change occurred when a second method of evaluating teachers was introduced, referred to as the “Teaching Career Evaluation.” This evaluation encompassed all teachers associated with schools that received state funding. Consequently, educators from state-funded educational institutions were included in the evaluation process ( Martínez, 2022 ; Colegio de Profesores, 2023 ). Importantly, the evaluation was not designed to supplement the existing evaluation system but introduced an additional evaluation more closely associated with the years of a teacher’s career. Consequently, teachers within the public system were subject to evaluations from two distinct systems, increasing their workload and the demands placed on them.

Both evaluations were designed to reinforce the teaching profession and contribute to improving the quality of education. The “Teaching Evaluation” comprises four key components: (1) a self-assessment rubric; (2) an interview conducted by a peer evaluator; (3) a third-party reference report; and (4) a portfolio showcasing an in-video pedagogical performance. Each component includes a rating assigned to the teacher, classifying teachers into different performance levels: outstanding, competent, basic, or unsatisfactory. The “Teaching Career Evaluation” includes (1) an evaluation of specific and pedagogical knowledge and (2) the same portfolio used in the “Teaching Evaluation.” According to Alvarado (2012) , the teachers’ performance and their students’ academic performance on math- and language-standardized national tests have been positively correlated.

Teachers who received favorable evaluations progress to higher tiers within the Teaching Career framework. The upper tiers often entail augmented salary packages and improved working conditions ( Manzi et al., 2011 ). Engagement in these evaluative assessments may be a financial necessity for some teachers due to the comparatively modest salaries that educators in Chile receive ( Assaél and Cornejo, 2018 ; Avalos-Bevan, 2018 ), rather than an opportunity to foster reflection between peers regarding their pedagogical practice and work ( Assaél and Cornejo, 2018 ; Avalos-Bevan, 2018 ).

Consequently, public school teachers in Chile have experience with being observed and engaging in discussions with others regarding their teaching practices. However, these experiences may be biased toward an emphasis on assessment and evaluation, which, in turn, translates into an economic impact.

2.1 Participants

The participants in this study were observers of at least one RL hosted by different LS teams. The survey and methodology were approved by our ethics committee. An open invitation to complete the survey was sent to the participants of three different RLs sponsored by the Center for Advanced Research in Education (CIAE). Participants answered the survey between March and May 2020. All RLs were Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM)-related and planned for primary education, with an open invitation to elementary and secondary school teachers, academics, researchers, educators, future teachers, school administrators, and educational authorities. The teachers who taught the lesson were experienced teachers. Two were held in Santiago, Chile, in 2017 and 2018, and the third in Valparaíso, Chile, in 2019. The last RL was conducted within the context of the XI Regional Conference on Lesson Studies.

A total of 97 participants answered the survey, and 92 agreed to participate, resulting in a response rate of 94.84%. Of the 92 participants, 62 were women (67.39%), and 30 were men (32.61%). Regarding the participants’ occupations, 70 were in-service teachers (76.08%), five were student teachers (5.43%), and 17 (18.47%) had other roles related to education, such as academics, members of a school board, and principals.

Regarding the participants’ observation experience, the information available is limited. As explained in the previous section, teachers in Chile have experience being observed; however, we do not have evidence of the level of training that the participants received as observers before attending the RL.

2.2 Instruments

A questionnaire was developed to assess participants’ perceptions of the RL’s contributions to their skills and beliefs.

2.2.1 RL contribution to pedagogical practices, overall LS evaluation, and future participation

Participants answered five Likert-scale questions regarding the contribution level of RL to their (1) knowledge of the subject matter, (2) instructional strategies, (3) skills to monitor the level of understanding of the students, (4) lesson planning skills, and (5) abilities to assess the students’ understanding of the content. Participants evaluated the contribution of RL by choosing one of five options (from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely relevant ). This type of question, which includes scale with neutral option, has been used in previous studies to evaluate the impact of LS on teachers’ professional development ( Alamri, 2020 ), participants’ perception of changes in intercultural competence for lesson study ( Sakai et al., 2022 ).

Participants also answered a Likert-scale question about their overall evaluation of RL that was rated from very poor (1) to very good (5), as well as a question regarding whether they would participate again in an RL session, which was rated as yes , maybe , or no .

2.2.2 Teachers’ beliefs about learning

The Teacher Beliefs Interview (TBI), a semi-structured interview protocol, was developed to describe and map various epistemological beliefs held by science teachers ( Luft and Roehrig, 2007 ). Based on the TBI, teachers’ beliefs range from teacher-focused to student-focused. The TBI includes seven items assessing their knowledge and learning beliefs. Depending on the teachers’ responses, their beliefs were coded into five categories: (1) t raditional , with a focus on information, transmission, structure, or sources; (2) instructive , with a focus on providing experiences, teacher focus, or teacher decisions; (3) transitional , with a focus on teacher/student relationships, subjective decisions, or affective responses; (4) responsive , with a focus on collaboration, feedback, or knowledge development; and (5) reform-based , focusing on mediating student knowledge or interactions. The traditional and instructive categories are teacher-focused, whereas the responsive and reform-based categories are student-focused. This instrument has been employed in prior studies about LS and teachers’ beliefs. In the study by Tupper (2022) , the TBI was utilized alongside other instruments to assess the relationship between teachers’ beliefs, self-efficacy, and professional noticing with multiple lesson study experiences. Similarly, Fortney (2009) incorporated the TBI, among other instruments, to investigate how teachers reconcile student-centered instruction with their preexisting traditional beliefs about teaching. Finally, Yakar and Turgut (2017) also used the TBI and found that through lesson study preservice teachers changed their beliefs toward more student-centered.

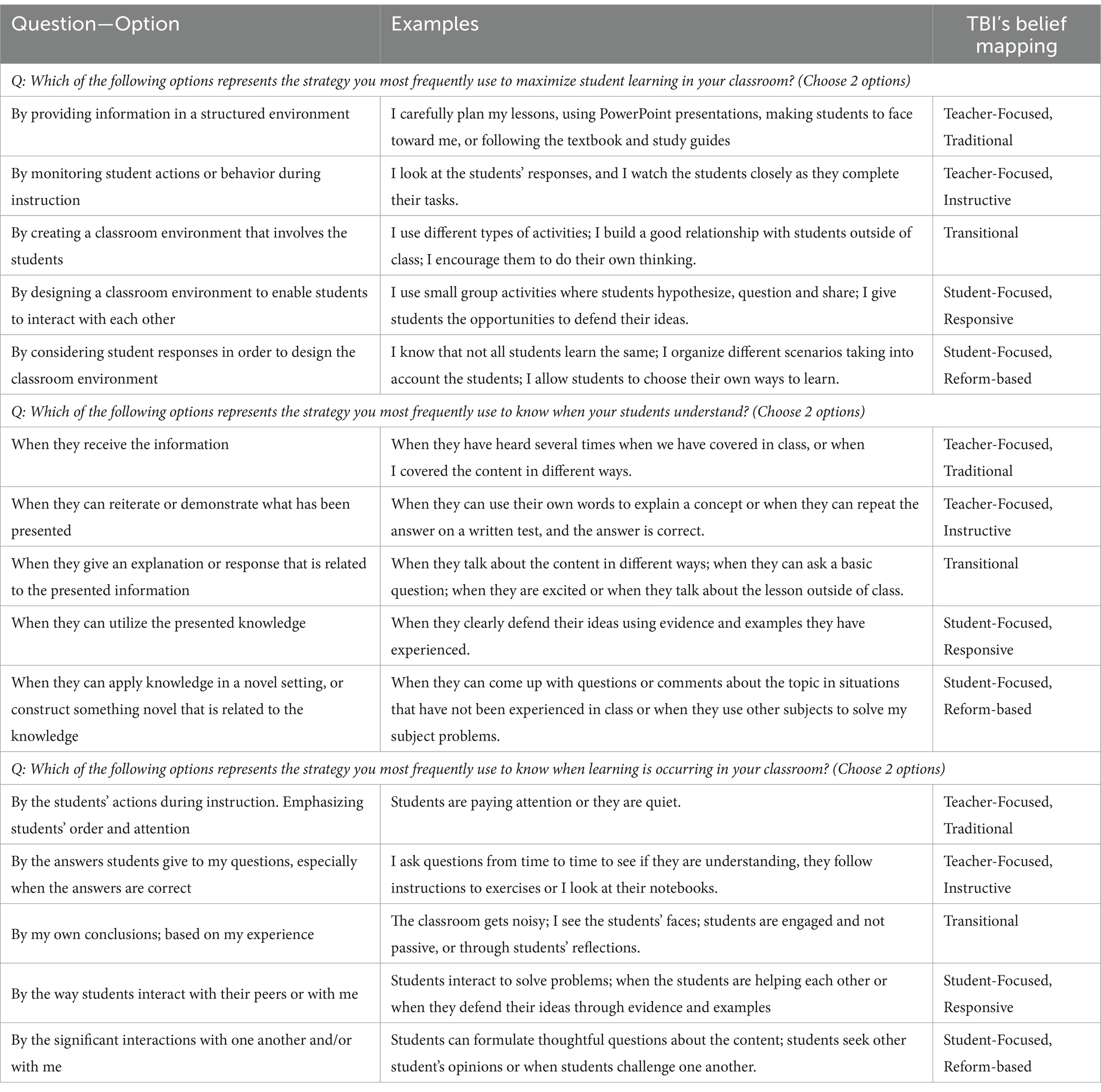

Of the seven questions on TBI, four were related to learning beliefs. The other three items were related to knowledge beliefs. Three questions regarding learning were included in the questionnaire (the fourth question was excluded because it asked about science learning). Rather than adhering to the open-ended format, we modified the approach by incorporating the three questions that asked the participants to choose between two real-life strategies using concrete examples. These three questions were related to the participants’ beliefs about learning. This adaptation led to a structured multiple-choice format, providing participants with clear examples while maintaining the integrity of the TBI’s underlying principles. Table 1 shows the questions, examples, and mapping suggested by Luft and Roehrig (2007) for assessing the participants’ beliefs.

Table 1 . Questions in the survey and the corresponding response mapping based on TBI.

The Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to measure the reliability of the instrument. The results showed that the instrument had an estimated α equal to 0.68.

2.3 Analysis

To answer the research question, a descriptive analysis and stepwise logistic regression model were performed for each dependent variable. Five independent models were tested, one for each dependent variable.

2.3.1 Dependent variable—RL contribution

The five dependent variables were the RL contributions to knowledge, instruction, monitoring, planning, and assessment. Each variable was binary, with value 1 being assigned when the participant evaluated the RL’s level of contribution as either very or extremely and a value of 0 being assigned for all other ratings.

2.3.2 Independent variables

Participants’ beliefs were considered independent variables. Thus, there were three independent variables, each corresponding to one of the three questions regarding how participants (1) maximized learning in their classrooms, coded as max_learning; (2) knew when their students understood, coded as understanding; and (3) knew when learning occurred in their classrooms, coded as learning.

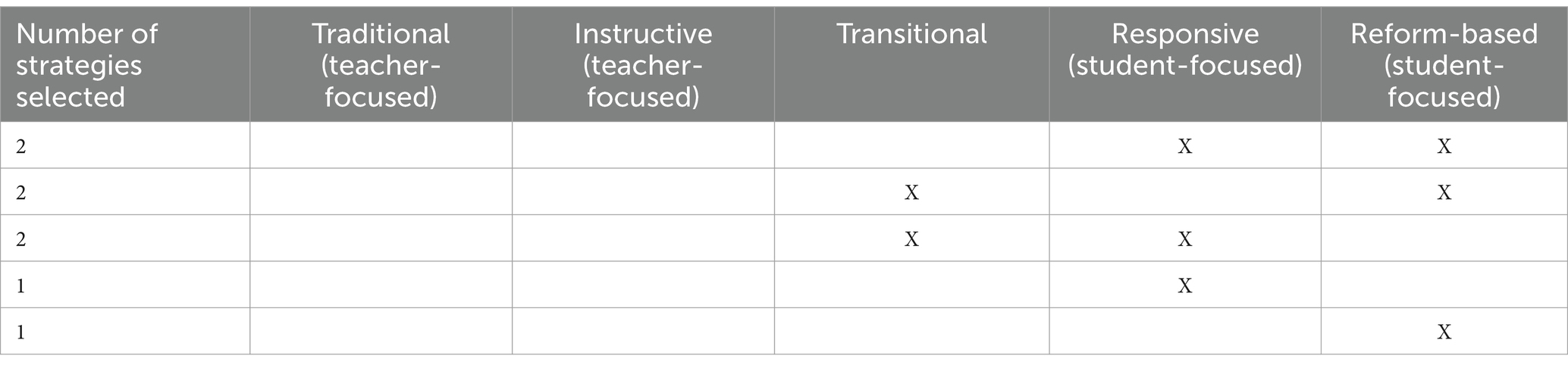

As with the dependent variables, each independent variable was binary, with the variable being scored as Student Focused (SF) when participants chose strategies that were mapped as student-focused and/or transitional on the TBI ( Luft and Roehrig, 2007 ) and Not Student Focused (NSF) in any other case. In other words, if a participant chose a responsive (R) and/or reform-based (RB) strategy alongside a transitional strategy, the participant was coded as SF. In all other cases, the participant was coded as NSF. Table 2 shows the scenarios in which participants were classified as having SF. The participants were classified as having NSF for all other combinations of selected strategies.

Table 2 . Categorization of participants’ answers based on number of strategies selected.

2.3.3 Other explanatory variables

Two other independent variables are also considered. The first was sex (woman or man), while the second was the participant’s occupation ( in-service teacher , student teacher , or other ).

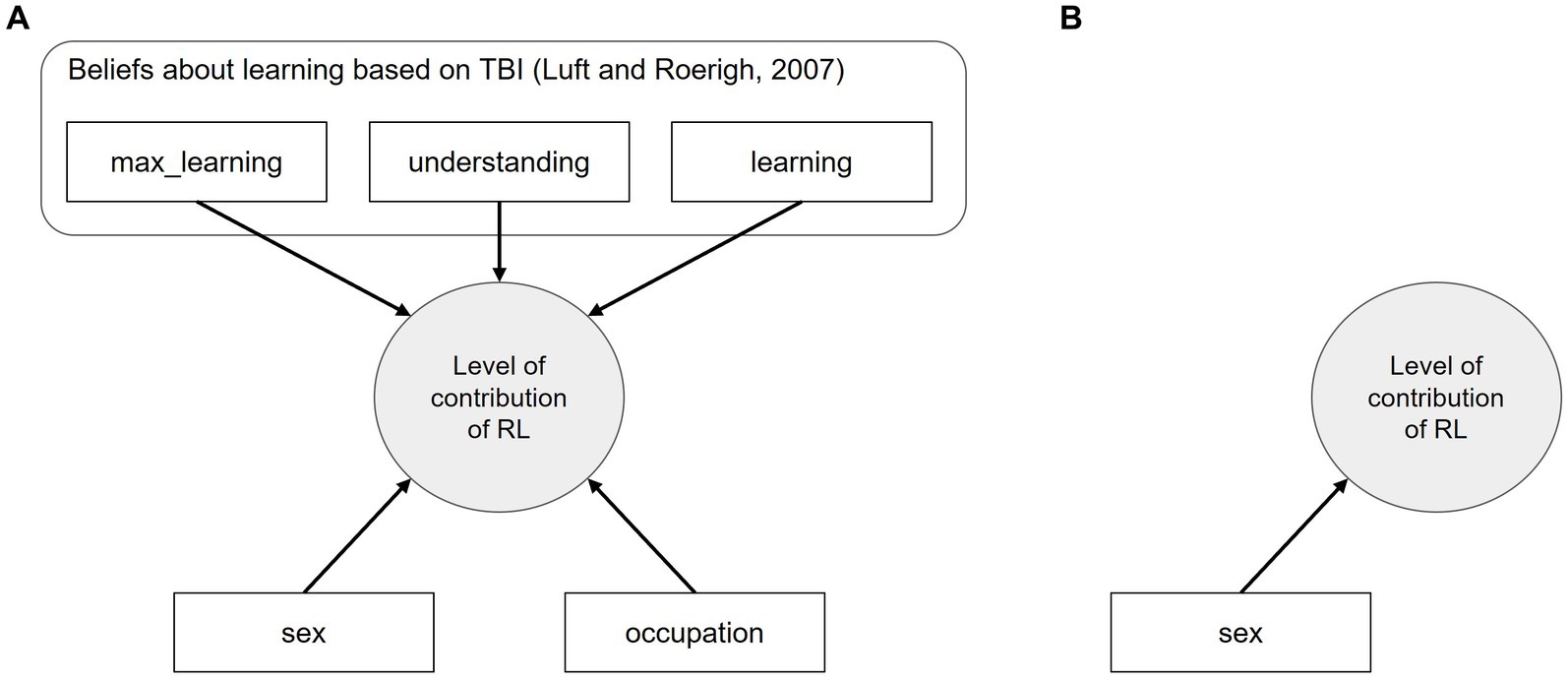

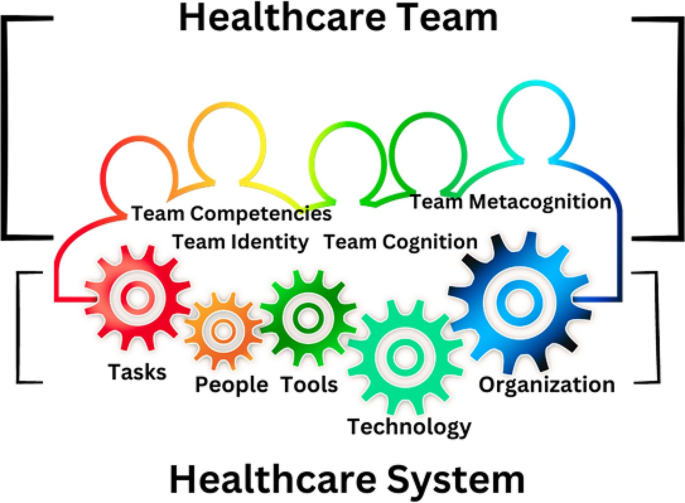

The stepwise logistic regression selection considered a full model with all the variables involved (max_learning, understanding, learning, sex, and occupation) and a base model with only sex as an independent variable ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Models explaining the level of contribution of the RL used in the stepwise logistic regression. (A) Full model with all the variables involved. (B) Base model with sex as the independent variable.

The notation for the full model is:

For the base model, it is:

Model selection used the R function stepAIC ( Zhang, 2016 ), which iteratively adds and removes predictors to the base model. Thus, the best model was selected based on its lower AIC value ( Akaike, 1974 ). This process was performed independently for each dependent variable: the level of contribution of RL to (1) knowledge, (2) instruction, (3) monitoring, (4) planning, and (5) assessment. Finally, when a variable was significant, the odds ratio (OR) was reported as a measure of the association between exposure and outcome ( Szumilas, 2010 ).

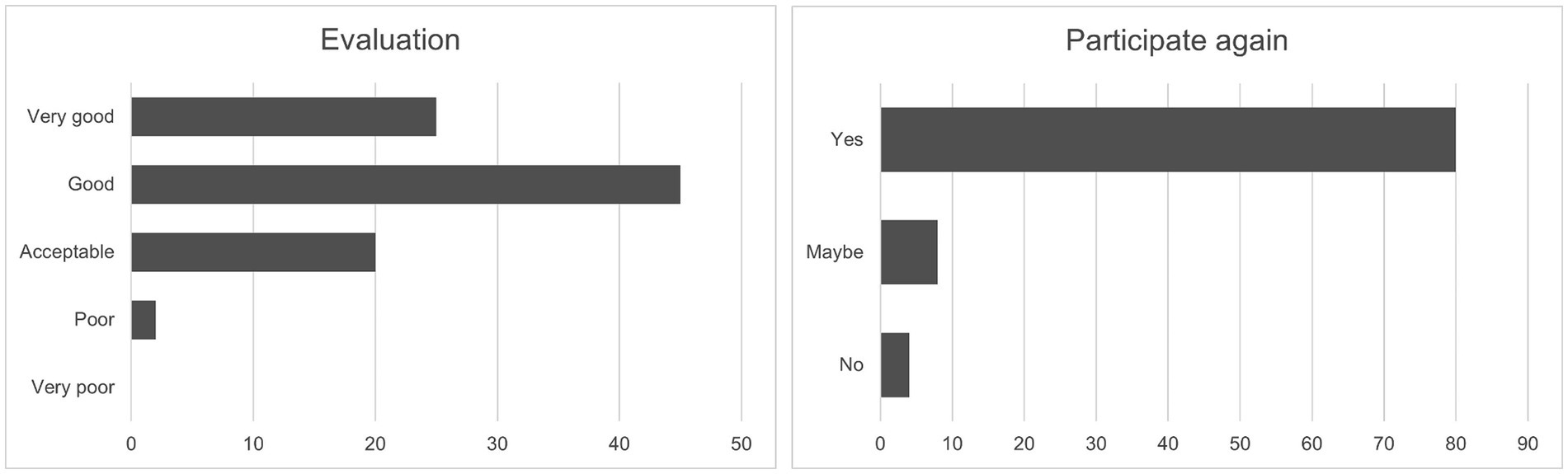

3.1 LS evaluation and future participation

Overall, the LS received a positive evaluation: 76.09% of teachers evaluated RL as either good or very good ( N = 70). When asked if they would participate again in RL, 86.95% reported that they would. The distribution of the answers is shown in Figure 2 .

Figure 2 . Number of answers of the participants’ overall evaluation of RL and future participation.

3.2 Participants’ beliefs

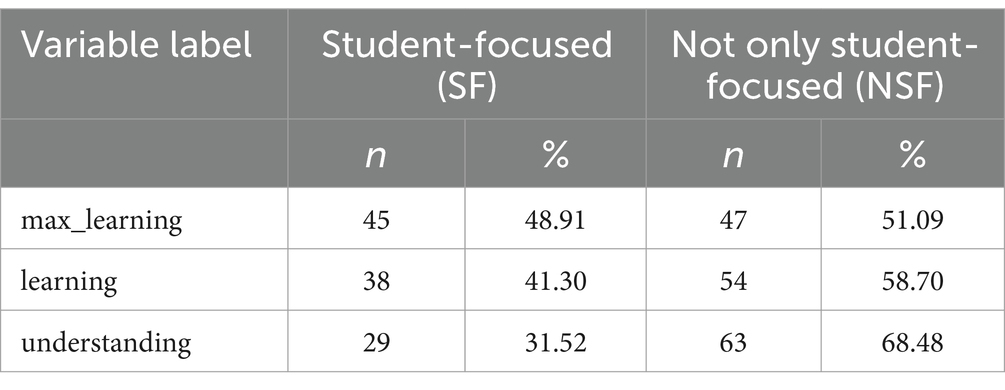

Table 3 summarizes the distribution of teachers’ beliefs after categorizing them as either SF or NSF.

Table 3 . Distribution of the observers’ beliefs for each independent variable, based on the TBI categories.

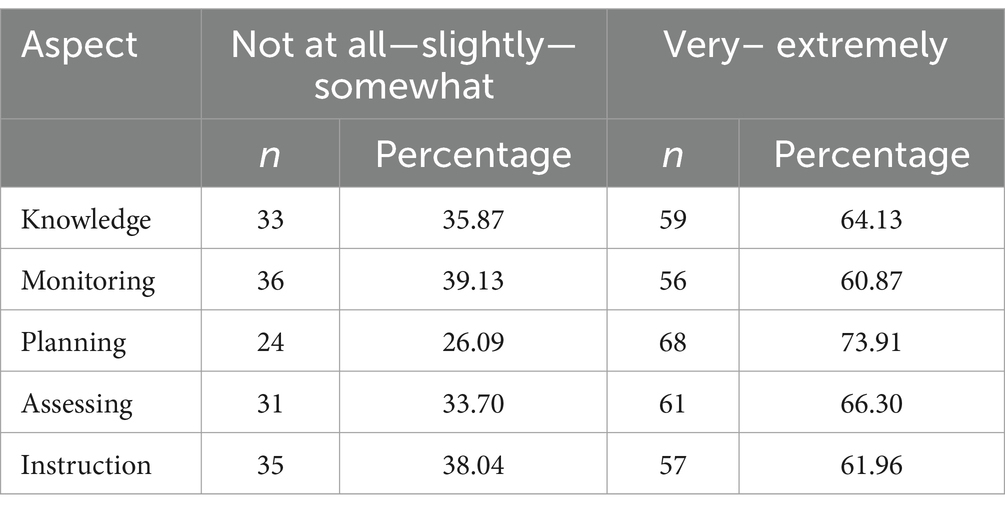

3.3 Reported RL impact on pedagogical aspects

Table 4 shows the level of contribution of RL to pedagogical practices as reported by the participants. The aspects with the highest levels of impact were planning and assessment, while the aspects with the lowest impact on teachers’ pedagogical practices were monitoring and instruction.

Table 4 . Evaluation of the contribution of RL to different aspects.

3.4 Impact of participants’ beliefs on RL contribution

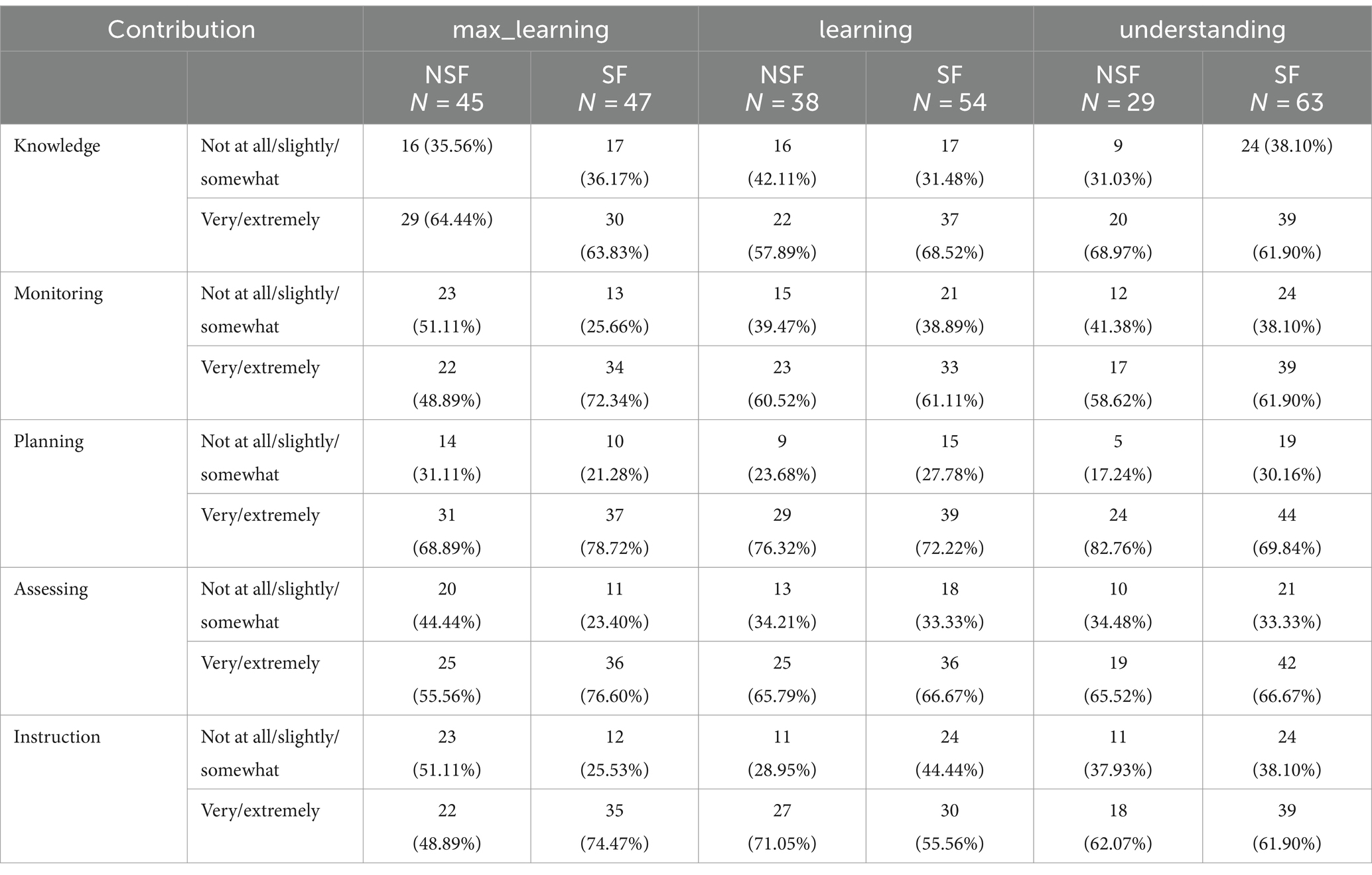

Table 5 summarizes the distribution of the level of contribution by belief for the three independent variables. Results in Table 5 suggest that participants’ beliefs might influence the perception of the RL contribution. The data imply a consistent trend where observers with SF beliefs tend to value the RL contribution more than those with NSF beliefs. Moreover, the differences are more or less pronounced depending on how those underlying beliefs are measured (i.e., max learning, learning, or understanding).

Table 5 . Distribution of evaluation of the contribution of the RL based on the category of observers’ beliefs.

Differences in the RL’s contribution based on the observers’ beliefs were observed. Regarding monitoring skills, 72.34% of those with SF beliefs (measured with the variable max_learning) valued the contribution of RL as very or extremely , while less than half of observers with NSF beliefs shared the same valuation.

In terms of assessing skills, 76.60% of participants with SF beliefs (measured with the variable max_learning) rated the contribution as very or extremely , compared to 55.56% of those who were NSF.

The results for the instructional skills varied. When considering the observers’ beliefs measured by the variable max_learning, 74.47% of the observers with SF beliefs valued the contribution of RL positively, in contrast to 48.89% of those with NSF. In contrast, when measuring beliefs by the variable learning, 71.05% of observers with NSF beliefs valued the contribution as positive, whereas 55.56% of observers with student-focused SF beliefs shared the same view.

3.4.1 Knowledge

The summary of the logistic regression model is shown in Table 6 .

Table 6 . Logistic regression summary for the selected model illustrating the contribution of RL to knowledge.

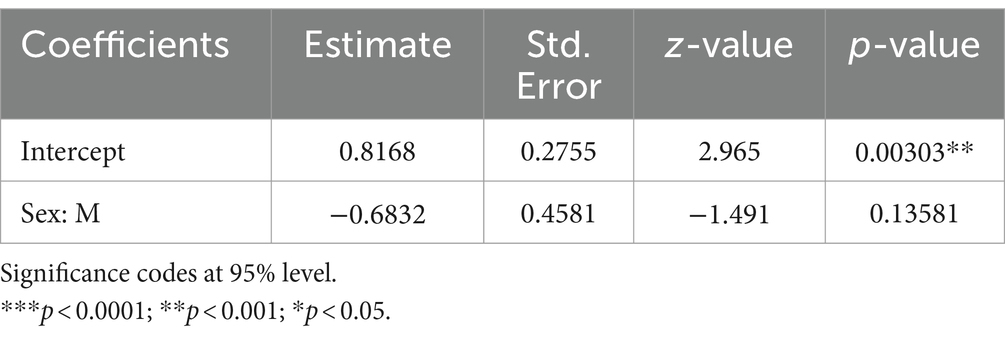

The selected model was the base model (AIC = 121.87), with sex as the only independent variable. However, sex was not a significant predictor of the probability of evaluating contribution to RL ( p = 0.14; Table 6 ). Thus, the participants’ beliefs did not add information when explaining the contribution of RL to their knowledge skills.

3.4.2 Monitoring

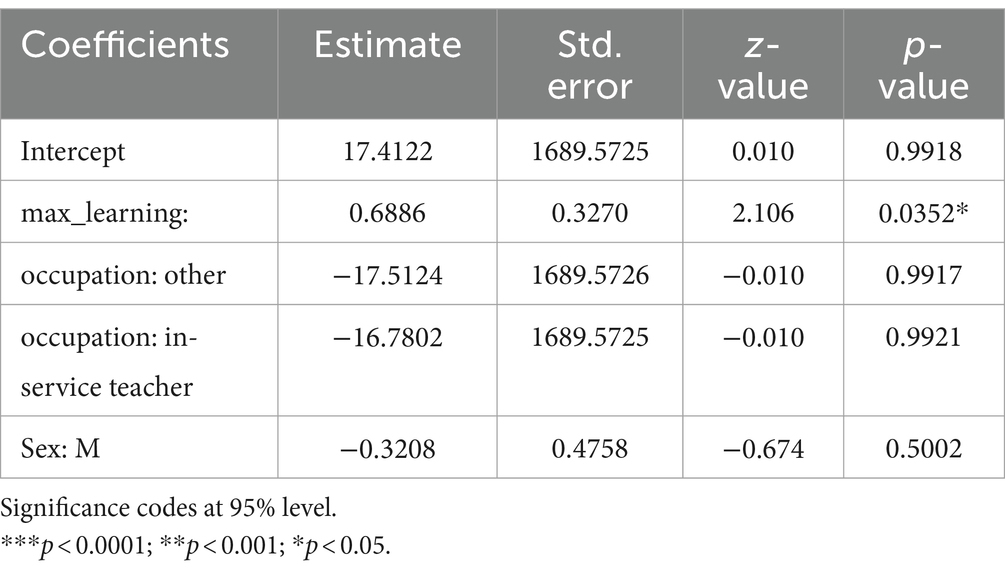

The summary of the logistic regression model is shown in Table 7 .

Table 7 . Logistic regression summary for the selected model showing the contribution of RL to monitoring.

The model that best explained the contribution of RL to monitoring skills was the independent variable max_learning after controlling for sex and occupation (AIC = 121.44). The variable max_learning had a significant positive estimated value ( p = 0.035), whereas the other variables (i.e., sex and occupation) were not significant. In other words, when holding the variables of sex and occupation constant, participants with SF beliefs (measured through the variable max_learning) were more likely to rate the contribution of RL on their monitoring skills as very or extremely (OR = 1.99, 95%CI [1.06, 3.85]).

3.4.3 Planning

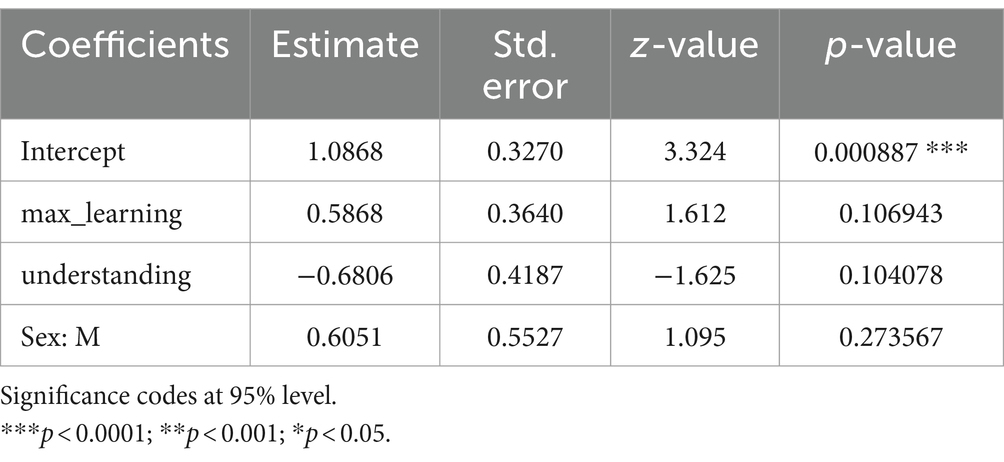

The selected model considered max_learning and understanding as independent variables, controlling for sex (AIC = 108.29). Table 8 summarizes the corresponding logistic regression results.

Table 8 . Logistic regression summary for the selected model showing RL’s contribution to planning.

In the selected model, the three independent variables had nonsignificant estimated values. The variables max_learning and sex had positive values, while understanding had an estimated negative value.

3.4.4 Assessing

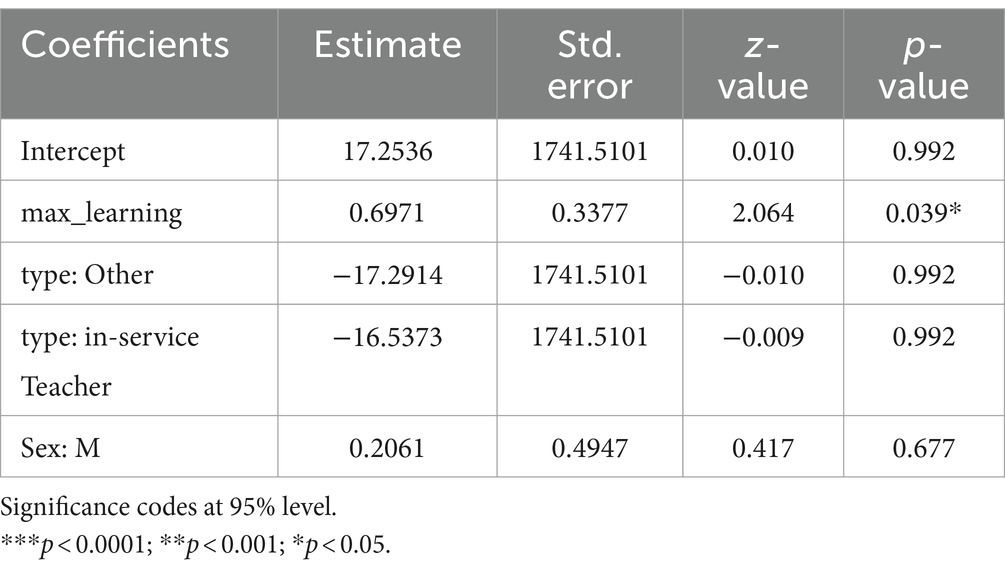

The model that best explains the contribution to assessment is the independent variable max_learning, after controlling for sex and occupation (AIC = 117.66). Table 9 summarizes the corresponding logistic regression results.

Table 9 . Logistic regression summary for the selected model showing RL’s contribution to assessing.

In the selected model, max_learning had a positive and significant estimated value ( p = 0.039). Thus, when holding the variables of sex and occupation constant, observers with SF beliefs, measured through the variable max_learning, were more likely to value the contribution on assessing as very or extremely , in contrast to the observers with NSF beliefs (OR = 2.01, 95%CI [1.05, 3.98]).

3.4.5 Instruction

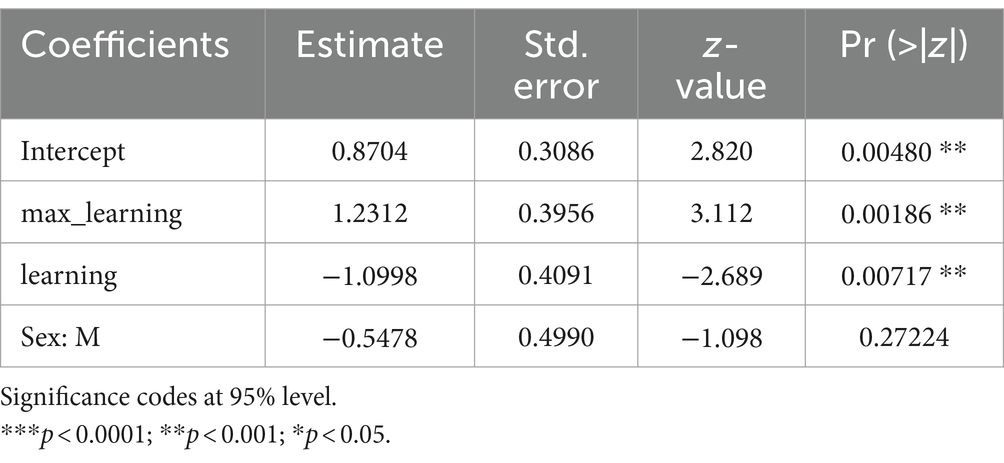

The model that best explains the contribution to instruction had the independent variables max_learning and learning controlled for by sex (AIC = 114.68). Table 10 summarizes the corresponding logistic regression results.

Table 10 . Logistic regression summary for the selected model showing RL’s contribution to instruction.

In this model, the variable max_learning had a significant, positive estimated value ( p = 0.002), whereas the variable learning had a significant, negative estimated value ( p = 0.007). Thus, when holding the variable of sex constant, observers with beliefs which were SF, measured through the variable max_learning, were more likely to value the contribution on assessing as very or extremely , in contrast to the observers with NSF beliefs. Further when controlling for the variable of sex, observers with beliefs that were NSF, measured through the variable learning, were more likely to value the contribution on instruction as very or extremely .

4 Discussion and conclusion

This study has two aims. First, we aimed to collect evaluations of observers outside the LS team when attending the LS Research Lesson stage. Second, we examined how the observers’ beliefs affected their evaluations of RL. Thus, the research question (RQ) was, “To what extent do teachers’ beliefs affect the perceived contribution of a Research Lesson in the context of a lesson-study process?”

Evidence indicates that LS teams do not share their learning with their peers, thereby losing opportunities to share and discuss their experiences with the educational community. An RL provides teachers new opportunities to observe experienced teachers to model their own learning experiences and discuss curricula and standards, helping persuade teachers to align their teaching with policy and evidence-based recommendations. However, little is known about the RS stage, particularly regarding how to share work with others. Whitney (2020) studied cases of LS study teams in the US and found that most LS teams did not distribute their learning to the field, and instances of people outside the team watching the research lesson and participating in post-lesson discussions existed.

Nonetheless, a relationship has been observed between beliefs and classroom practices ( Skott, 2001 ; Stipek et al., 2001 ; Schoenfeld, 2011 ). Moreover, these beliefs could affect teachers’ changes in the context of professional development programs ( Maass, 2011 ). de Vries et al. (2013) found a relationship between teachers’ participation in Continuous Professional Development programs and their beliefs.

This paper aims to reduce the existing gap between the implementation of LS in Japan and in other countries. When considering the implementation of LS in Chile, it is critical to look at teachers’ predisposition to observation. Historically, teachers of public schools have experience in being observed; however, class observation has been associated with assessment and evaluation. Although this research does not specifically inquire about teachers’ beliefs regarding observation, it is an important element to consider in the teaching culture of Chile. For example, by conducting RL observation, Chilean teachers could focus more on evaluating aspects that are important in their own teaching evaluation, such as class planning and student assessment.

The results show that, in the Chilean context, when explaining the perceived contribution of the RL, observers’ beliefs improved the models’ performance, contributing to instruction, monitoring, planning, and evaluation. The current findings are beneficial, as they provide insights into how different participants value their contributions to RL. Furthermore, LS teams should consider this when issuing open invitations to external individuals to observe RL. Understanding the influence of participants’ beliefs on their evaluation of a situation is valuable. In addition, these findings can help develop strategies for more effective LS implementation, such as designing two types of LS, one adapted to teachers with beliefs about teaching focused on students and the other adapted to teaching beliefs focused on teachers. To the best of our knowledge, this dual strategy is currently not a part of LS implementation, at least in Chile. LS teams could easily explore this dual strategy, which could improve teachers’ professional development. In terms of practical implications, we believe that by adapting different types of LS, the whole group collaboration within each RL could lead to a richer discussion on aspects of the lesson. It would bring to the forefront those aspects that might not initially appear to contribute significantly. As a result, it would promote reflection among observers based on their own beliefs. Moreover, this dual strategy could help emphasize the benefits of the methodology and strengthen the overarching goals of the LS by highlighting those aspects that are less appreciated within each group.

LS encompasses multiple stages and requires dedication from the LS team. This paper provides initial insights into a single stage of LS based on a limited sample. Nonetheless, future research should focus on the whole process, considering a more holistic perspective of the LS implementation. Similarly, future research could explore the beliefs of the LS team, rather than solely focusing on the observers of the RL. Additionally, considering other contextual factors such as school culture, previous observation experiences, and administrative resources to participate in Professional Development activities. For instance, it would greatly enrich the analysis of future research to know the level of expertise participants have in conducting observations. This would allow us to understand more deeply which aspects teachers highlight depending on their experience in observation. Finally, the students’ behavior, which was outside of the scope of this work, may be affected by changes in their routine, such as the physical space allowing for a large number of observers or different teachers than those they are used to. On the other hand, we used the TBI ( Luft and Roehrig, 2007 ) in a novel manner, which was developed to be used as an interview. We used the open-ended TBI questions and provided the participants with concrete examples based on the framework developed by Luft and Roehrig (2007) , thereby framing the questions in a multiple-choice format instead of an open-ended approach. While this method proved helpful in explaining the differences in the perceived contribution, future research should study alternative instruments for assessing participants’ beliefs. In particular, the questionnaire instrument has a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.68, which is close to the threshold of reliability; the reliability of this instrument might impact the measurement properties for this study, and the results should be taken with caution. Furthermore, a qualitative approach could provide insights into how and why those beliefs influence the participants’ perception of RL’s contributions.

Finally, in the Chilean context, opportunities for collaboration and peer observation that extend beyond evaluation purposes are important. The current study is an example of how people outside the LS team can benefit from different pedagogical aspects of this methodology. Future research should assess changes in teachers’ beliefs to determine whether the reported value of RL affects their daily practices.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Comité de Ética de la Investigación (CEI) de la Facultad de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad de Chile https://facso.uchile.cl/facultad/comites/comite-de-etica-de-la-investigacion . The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions